Abstract

Using qualitative data collected in Gulu and Omoro districts, Northern Uganda, this paper discusses factors influencing youth engagement in sweetpotato production and agribusiness in a post-conflict environment. The purpose is to understand the factors in order to promote young people’s participation in sweetpotato and other agricultural value chains. Thirteen young women and eleven young men were interviewed in individual in-depth interviews. Additionally, 74 young women and 85 young men participated in 16 sex-disaggregated focus group discussions. Our study identifies that rural youth’s participation in sweetpotato production and agribusiness is a product of the intersection of broader community/national context, individual circumstances (age, gender, marital status, education and social class), and individual and collective agency. Our proposed strategies to encourage youth participation in the agricultural value chain consider young people’s intersectional identities and address national- and community-level issues such as access to knowledge and information, land, markets and gendered power hierarchies.

Introduction

More than half of Uganda’s population depends on agriculture for their livelihood (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2021b). Despite the importance of the sector in Uganda and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), many young people are not interested in agriculture, lack opportunities to be gainfully engaged or regard agriculture as an employer of last resort (Ameyaw and Maiga Citation2015; Mudege, Bullock, and Rietveld Citation2017; Whyte and Acio Citation2017; Rietveld et al. Citation2020). Uganda faces the challenge of an ageing and uneducated agricultural force in the foreseeable future (Ahaibwe, Mbowa, and Lwanga Citation2013), despite having one of the most youthful populations in the world, with more than 70% of its population aged 30 and younger (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2021a). There is, therefore, cause for concern because young men’s and young women’s participation in agriculture is critical to the sustainability of Uganda’s agriculture. It is thus important to examine the lived experiences of rural young men and young women and their engagement in agriculture as labourers or entrepreneurs, to understand the opportunities and constraints they face in their efforts to make a living in the sector. This paper focuses on a post-conflict area in northern Uganda. It seeks to discuss and understand factors influencing young men’s and young women’s engagement in sweetpotato production and agribusiness to promote their participation in sweetpotato and other agricultural value chains, given the adverse conditions under which they currently operate.

The paper uses the terms ‘youth’ and ‘young people’ interchangeably, as is the case with the African Union (Citation2006), while the terms ‘young men’ and ‘young women’ denote the gender of young people or youth. The term ‘youth’ has been defined in many ways. Some definitions focus on age delineations. For example, the African Union (Citation2006) uses the term ‘youth’ to refer to persons between the ages of 15 and 35 years, while the Uganda Bureau of Statistics uses the term to refer to persons aged 18–30 years. Other definitions focus on youth as persons who are transitioning from childhood to adulthood (Losch Citation2016; Ripoll et al. Citation2017). Both approaches have their pros and cons. For example, it has been noted that using chronological age to define youth or someone as a young person can help delineate boundaries for statistical and other purposes, but ‘it ignores the intersecting identities of young people’ (Mudege, Bullock, and Rietveld Citation2017, 8). Also, Ripoll et al. point out that ‘being young is not a uniformly experienced transitional phase in life between childhood and adulthood. Rather it is […] highly gendered and intersects with other identities such as marital status, ethnic affiliation, class, education or employment status’ (Citation2017, 172). It is possible to be older than the official youth definition and yet remain in the youth category in rural Africa because ‘access to voice, to land and to full economic independence can occur relatively late in life’ (Losch Citation2016, 43). The definition of youth is, therefore, contextual.

While the authors of this paper are aware of the debates surrounding how to define young people, in selecting the respondents of this study, we initially adopted the definition of the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, which defines young people as persons aged between 18 and 30 years. However, the ages of the study participants in fact ranged between 15 and 33 years because recruitment was also impacted by the local communities’ definition of ‘youth’, which took into account individual circumstances. The local communities’ definition was more aligned with the African Union’s African Youth Charter.

Study context

The paper utilises qualitative data collected by the authors using funds from the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas. The data was gathered from youths in the Bungatira sub-county in Gulu district and the Bobi sub-county in Omoro district, Northern Uganda. Gulu district is bordered by Amuru district in the west, Lamwo in the north, Pader in the east and Omoro in the south. Omoro district was recently carved out of Gulu district and is bordered by Gulu district in the north, Pader in the east, Oyam in the south and Nwoya in the west.

Northern Uganda is still undergoing social and economic reconstruction after the conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the national army, the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF), which lasted two decades, from 1986 to 2006. A significant majority of people, estimated at more than 1.3 million, were internally displaced (Joireman, Sawyer, and Wilhoit Citation2012; Mugonola and Baliddawa Citation2015). Joireman, Sawyer, and Wilhoit (Citation2012) state that by 2005, 94% of the population in Gulu was displaced. Some people lived away from their homes for up to 20 years, which meant that many children came of age in the camps where people could not farm and depended on food aid (Whyte and Acio Citation2017). Soon after the war ended, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (iDMC Citation2008) noted that the population in Gulu was made up of a majority of young people, many of whom had no memories or experience of rural life. Therefore, these young people were more likely to be drawn to trading centres or towns. Indeed, many people settled in towns after the war, and a majority portion of the population in Gulu and Omoro districts (55.5%) lives in urban centres (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2017). However, many young people live in rural areas in communities whose main economic activity is small-scale farming. These young people face challenges, such as lack of access to land, that limit their engagement in agricultural production and agribusiness. Some of the challenges are a result of the war. For instance, war disrupted gender and generational relations through which young men and young women accessed land. Before the war, young men gained land mainly through their fathers and young women through their husbands (Whyte and Acio Citation2017). Young women could also use the land of their fathers if they left their husbands (Whyte and Acio Citation2017). Although the land is still accessed through relations of gender and generation, death, displacement and inability to marry put many young men and young women in positions where their claims to land were no longer guaranteed.

In rural Gulu and Omoro, persons aged 30 years and younger account for 77.9% of the total population (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2017), and most of those working are engaged in agriculture (Ameyaw and Maiga Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to understand young people’s engagement in agriculture in Gulu and Omoro districts since agriculture contributes significantly to livelihoods and food security. Additionally, 23.8% of the total households in rural Gulu and Omoro districts are headed by young people (aged 18–30 years; Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2017), indicating that young people play a significant role within this community.

This paper uses research on youth engagement in sweetpotato production and agribusiness as an entry point because this crop is among the top three food crops in Uganda, and the country is among the major global sweetpotato producers in terms of quantities produced (Zawedde et al. Citation2014). Interventions targeting the sweetpotato value chain could potentially contribute to youth retention in agribusiness and to enhancing food security. The term ‘agribusiness’ is used here to refer to all activities and services along the agricultural value-chain, including input supply, production, processing, distribution and retail sectors (Richards Citation2022).

Data collection, sampling and analytical framework

The study used qualitative methods, including individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). Qualitative methods were selected because ‘they help to answer complex questions such as how and why efforts to implement best practices may succeed or fail’ (Hamilton and Finley Citation2020, 1). Pincock and Jones suggest that when working with young people, especially those that are marginalised, there is a need to use methods that are ‘adaptable, interesting and create space within the research process for participation and freedom of expression’ (Citation2020, 1). In our case, it was critical to use qualitative methods that allowed young people affected by war and conflict to speak up and share their views and opinions in a safe environment. Lastly, we used qualitative methods because we needed to apply the concept of intersectionality in understanding how young men’s and young women’s lived experiences influenced their ability to engage in agribusiness. Intersectionality is the understanding that factors such as gender, age, ethnicity and class often intersect to influence socio-political and economic outcomes for individuals and communities (Crenshaw Citation1989; Vastapuu Citation2018). For instance, among youth, young women may be at a more significant disadvantage than young men because of their gender (Rietveld et al. Citation2020). Within the sub-group of young women, social class, marital status or having children may place some at a greater or lesser disadvantage than others. Qualitative methods allow for the broadening of ‘the scope of intersectionality to study dominant identities, mapping more clearly how knowledge, diversity and equality operate in interconnected dialectic ways’ (Rodriguez Citation2018, 429). Qualitative methods were, therefore, appropriate for our study objectives.

The study locations, Bungatira and Bobi sub-counties, were selected because the communities had recently been beneficiaries of interventions meant to improve the participation of women, young people and other vulnerable groups in the sweetpotato business. Study respondents were identified and purposively selected using the following criteria: (1) being a youth, (2) being a resident of Bungatira and Bobi, and (3) having some experience in cultivation and/or trading sweetpotato. These criteria ensured that respondents were proficient and well informed about the study subject matter and that they had an in-depth understanding of the socio-economic and political dynamics of the area.

A total of 13 young women and 11 young men were interviewed in individual IDIs. Four young women were married, three were single mothers, and six were single, while four young men were married, and seven were single. Additionally, 16 sex-disaggregated FGDs were held in the two sub-counties. Eight groups were made up of young women whose number, when added together, totalled 74. The other eight groups were made up of young men whose number, when added together, totalled 85. Those who responded to IDIs did not participate in the FGDs.

We designed an informed consent form. All individuals who participated in the interviews were taken through the informed consent form, which they signed to show their consent to participate. Those who participated in FGDs gave group consent. Group participants were asked to provide verbal consent. The study team explained to all study participants that participation was voluntary. Voluntary participation meant that participants were free to refuse to participate without any implications for their ability to participate in and benefit from projects in the future; they could refuse to answer any questions, and they could end their participation at any time. The study team also explained that all collected information would be anonymised during analysis to protect their identity.

Analytical framework

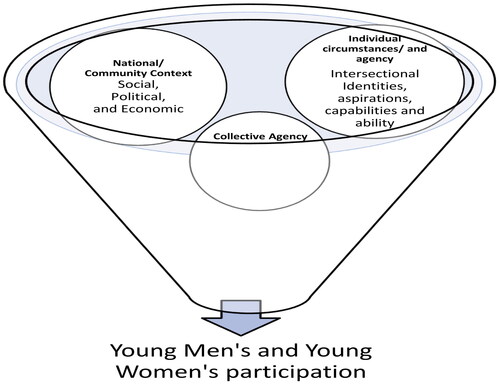

After consulting authors such as Ripoll et al., who proposed a framework ‘with which to analyse young people’s economic room to manoeuvre in different rural contexts’ (Citation2017, 168), and Leavy and Smith, who explored the dynamic processes through which aspirations of young people are ‘formed, shaped and influenced by economic context, social norms and customs, parental and peer influence […] and gender relations’ (Citation2010, 3), we developed a simplified framework to collect and analyse data. The framework was also influenced by the intersectionality literature. Thus, taking our cue from Rodriguez, we used ‘multi-stakeholder, multi-level analyses of differential social, economic and political power, and [embedded] non-hierarchical notions of difference as part of intersectional analyses’ (Citation2018, 429). Through the intersectionality concept, we conceptualise the participation of young men and young women in sweetpotato production and agribusiness as a product of the broader national and community context, individual circumstances and agency, and group or collective agency. These elements interact to create prohibitive or enabling conditions for young people’s participation in sweetpotato agribusiness (see ).

Figure 1. Framework of factors affecting young men’s and young women’s participation in agricultural enterprises.

The broader national and community context

This is the backdrop within which young men and young women carry out their economic or productive activities and that roots young people within specific social, political and economic contexts. The national-level context could include policies that support youth engagement. At the community level, there are local factors such as youth’s access to quality land, access to markets, social norms that govern how different people in the community behave and the entitlements they have, generational power relations, and the dynamics of rural transformation within the community.

Individual circumstances and agency

Individual circumstances include age, gender, marital status, level of education and social class. These factors influence individual aspirations, capabilities and ability to access resources. Accounting for individual circumstances allows for an intersectional approach that considers the heterogeneous nature of the group ‘youth’. Considering the differences among youth, in turn, allows for a more nuanced understanding of their experiences within the agricultural sector, which may lead to better intervention policies by government and development organisations (Rietveld et al. Citation2020).

In addition to individual circumstances, individual agency is also important. Agency is ‘the ability to define one’s goals and act upon them’ (Kabeer Citation1999, 438). Honwana (Citation2006) outlines two types of agency: strategic and tactical. To have strategic agency, a person needs to be in a position of power, be ‘fully conscious of the ultimate goals of their actions’, and ‘anticipate any long-term gains or benefits’ (Honwana Citation2006, 51). Those with tactical agency ‘are fully conscious of the immediate returns, and they act, within certain constraints, to seize opportunities that are available to them’ (Honwana Citation2006, 51). Complex power relations within communities and families influence individual circumstances and the type of agency a person can have. Therefore, understanding a young person’s position in relation to power hierarchies within the family and community can offer insights into the activities that youths engage in and differences in outcomes.

Collective agency

Sometimes, young people may be constrained to act as individuals and resort to collective agency. As a collective, young people may challenge existing norms and structures that disadvantage them in gaining access to resources they need to engage effectively in agriculture or other livelihood options. However, collectives can also reproduce power hierarchies that exist in the wider community, for example based on social class, thus limiting their effectiveness in promoting the engagement of certain sections of the youth in agribusiness. Understanding power dynamics within collectives is therefore necessary when promoting collective agency as a means of overcoming some individual limitations. See Pelenc, Bazile, and Ceruti (Citation2015) on the process of establishing collective agency and its contribution to developing sustainable initiatives.

Data analysis

To analyse data, we manually coded it using a Microsoft Excel matrix. The coding was based on a coding tree developed from several themes related to the participation of young men and young women in sweetpotato enterprises and aligned to our analytical framework. Themes falling under the community context included how social norms influenced young men’s and young women’s participation and access to resources such as land, and the effects of factors such as war and conflict on youth engagement in agriculture, especially sweetpotato farming. Under individual agency, the themes included the impact of marital status, education level and social-economic status on young men’s and young women’s involvement in sweetpotato farming, marketing and processing. Regarding collective agency, themes included youth participation and the quality of their involvement in farmers’ groups. The final theme focused on the opportunities and constraints of young people in sweetpotato-related business and what can be done to encourage their participation.

Findings

The first part of the findings section discusses factors that influence and shape young men’s and young women’s participation in agriculture in general and sweetpotato production enterprises in particular. These factors are important because they help explain the gap between young people’s potential and their actual experiences. The second section outlines solutions suggested by the youth that are aimed at promoting their participation in sweetpotato production and related businesses.

Factors influencing and shaping youth participation in sweetpotato production and agribusiness

Information obtained from the respondents suggests that community context, individual circumstances and agency, and collective agency play a significant role in influencing young people’s participation in sweetpotato production and agribusiness. Key issues in the narratives include access to land, peer pressure and local perceptions, gender and marital status, education and training, and social and economic status. These factors and key issues are presented in the following discussion.

Community context

Key community context factors that affect youth participation in sweetpotato production include limited availability of land, local perceptions and experiences, and peer pressure. These are mediated by social norms governing gender and intergenerational power relations, as discussed below.

Access to land

Young people’s access to land was significantly affected by the war. Due to displacement and the death of family elders or husbands, many young people no longer had a clear path to accessing ancestral lands. This negatively impacted their engagement in agricultural production. Also, when displaced families returned to their homes after the war, there were many land disputes because land boundaries were no longer clear, affecting the reintroduction of young people to agriculture.

Severe financial difficulties in the immediate post-war period led some families to sell off their land to meet the high cost of living, a trend that has continued to date. In FGDs, young women confirmed rampant land sales by male heads in their communities to meet the households’ cash needs. Young women indicated that they had limited power to stop the selling of land because male elders or husbands are the ones who have control over land. Land sales and growing populations have reduced the amount of land available for farming. During an individual interview, a 23-year-old man and household head said, ‘we have many clans in this area. Before, people used to have over 10 acres, but now most homes have less than two acres, and it is not enough’. These land shortages mean that young people are no longer guaranteed access to land even under customary law, a situation that has severely limited their prospects for earning income from agricultural production. Study participants pointed to limited access to land as one of the reasons they did not engage in sweetpotato production. Some youths mentioned that they sometimes hired land to cultivate. However, this option was expensive and unsustainable for sweetpotato since the crop was only grown for family consumption and did not generate income to cover the costs of hiring land. They therefore preferred to plant other crops like cassava on hired land.

Participants in FGDs pointed out that after the war, many families returned home ‘with nothing’, making it difficult to engage more effectively and efficiently in agriculture, and for young people to gain the necessary skills through practice. Young people could not learn sweetpotato production while in camps and, therefore, did not have the necessary knowledge and skills when they returned home. Also, when people returned from the camps, fear of landmines prevented them from immediately taking up sweetpotato farming because ‘it was risky to heap [mounds]; you were more likely to encounter land mines while doing so’ (young man in FGD, Bobi sub-county).

In addition, parents often have the power to decide how land is used and cropping patterns. In individual interviews, young people shared that where they depended on their parents for land, they could not grow crops of their choice due to their parents’ conflicting needs, demands and preferences. As such, young people’s opportunities were, to an extent, shaped by power hierarchies within their social contexts. To earn income independently, many young men and young women made a living from non-agricultural activities (). These non-agricultural activities are, in some cases, the only option for young men and young women to generate personal income since agricultural income is often controlled by their elders who own the land.

Table 1. Activities that young women and young men in rural Gulu and Omoro engage in to earn a living (mentioned in individual interviews and focus group discussions).

While both young men and young women had limited access to land, young women, especially those who were not married and had no children, were worse off regarding access to and control of land and decision-making regarding its use. Young women were not considered in terms of inheritance and access to land. FGD participants noted that young women are not given land and always farm with their parents since it is believed they will obtain land upon marriage. A majority of the single young women in FGDs and IDIs believed that once married, they would farm on their husband’s land, make decisions and generate an income for their families. However, getting married did not guarantee that a young woman would benefit from access to land, because although wives provide labour, husbands often have control over the land and its proceeds. The dissonance between the effort that women put in and their access to benefits is illustrated in the interview below:

When it comes to the sale of produce, my husband has to authorise it. Sometimes he takes the money leaving the family with nothing. There is no easy life. I cannot plan for anything because of being locked up by this man who does not give me the freedom to plan for a better family. […] I do not have anything of my own. If I could get out of this home to engage in agriculture and lead my own life, my life would probably change. My husband’s relatives do not allow me to have access to anything in the home. (interview with a married young woman in Bobi sub-county)

Married young women often expressed frustration because of the lack of freedom and opportunities to exercise agency concerning livelihood options. Access to land and benefits for young women was predicated on their relationship with specific men and their families. However, unlike unmarried young women with no children, who mentioned providing unpaid agricultural labour to their families, the consensus in FGDs and interviews was that divorced young mothers were often given small pieces of land by their parents to provide for their children.

Peer pressure, local perceptions and experiences

There is social pressure among young people to aspire to professions other than farming and, when involved in farming, to focus on cash crops instead of sweetpotato, which is regarded as a lowly crop. A female FGD participant said, ‘we fear carrying sweetpotato on our heads to take to the market because our suitors may see us and laugh at us’. Young men also mentioned avoiding carrying sweetpotato roots or vines to the market because their girlfriends may laugh at them. During one FGD, some young men mentioned that if they are given a motorcycle or a car, they can transport sweetpotato roots but not sell them because selling sweetpotato is ‘embarrassing’. The embarrassment mainly stemmed from the fact that local sweetpotato trading often earned small amounts of money compared to selling crops like cassava, and young people who engage in the sweetpotato trade are regarded as desperate. It was often mentioned that while older adults produced food security crops, youth liked growing high-value vegetables like cabbages, onions, tomatoes and green pepper, which have a ready market and provide quicker economic returns. Sweetpotato selling was generally considered a preserve of older women who had no other options. The physical local sweetpotato markets are dominated by women, further keeping young men from the market. Young men, however, are not embarrassed to sell sweetpotato in larger quantities at the farm gate or higher nodes of the sweetpotato value chain.

The community context described above had varying impacts on the activities and economic outcomes of Gulu and Omoro youth, depending on their circumstances and agency. Some of the individual circumstances are described below.

Individual circumstances and agency

Gender and marital status

Gender and marital status affected young men’s and young women’s access to land, and, for those with access to land, marital status influenced the types of activities they conducted. As mentioned, single young women with no children were at the greatest disadvantage since they primarily provided unpaid family labour. In contrast, married young women could access land through their husbands, and divorced young women with children were often given access to land by their parents or elders.

Some young women were at a more significant disadvantage than young men because they had less freedom of movement. Family structures are such that parents and relatives seek to exert more social control on young women than young men. Young women said some women do not have easy access to information and other resources because their husbands do not allow them to attend community gatherings. Thus, family norms, structure and parental controls prevented some young women from accessing resources.

Of all the young men and young women interviewed, only three young men expressed great interest in being professional farmers. All three were not married, had access to land and could earn personal income from farming activities. Unlike married young men and married young women who had to also consider food security crops, most single young men with access to land mainly focused on cash crops.

Education and training

Many of the young men and young women had dropped out of school and thus did not attend agriculture classes offered at school. There was a general agreement among the youth in Bungatira and Bobi sub-counties that the lack of education and knowledge affected their productivity and ability to provide enough food for their families.

Both young men and young women mentioned a lack of education and other entrepreneurial skills, like basic accounting and business management, as a critical barrier to accessing and managing loans. During an individual interview in Bungatira sub-county, a 25-year-old young man said, ‘loan applications require a lot of filling forms. Most of our youth are not educated and cannot do it’. Young people also mentioned that if young people had ‘life skills’, banks could consider these when assessing fitness for a loan instead of only assessing the asset base of the youth.

Additionally, many young people did not know how to control pests and diseases that affect sweetpotato or how to run an agricultural-related business. There was a consensus that it was not easy for young people to access information besides what they got from their elders. Many young people cannot seek information online because they do not have access to the internet. Many young people mentioned hearing about orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) on the radio. Nevertheless, the perception of some young people was that the radio did not provide in-depth information necessary for successful engagement in OFSP farming. A 24-year-old man from Bobi sub-county said that while information on the radio was good, visual demonstrations would improve his understanding because he wants ‘to see how exactly it is done’. This assertion highlights how the mode of learning is also an important consideration to ensure effective knowledge transfer. Of all the young people interviewed, only one young man, a 23-year-old from Bobi sub-county, said he had received information and advice from an extension officer who lives in his village.

However, a 23-year-old married woman in Bobi sub-county strongly felt that many young people did not actively seek knowledge because ‘they want everything to find them where they are’. She suggested that, although young people faced many limitations as a group, individual circumstances and agency were significant factors in determining individual outcomes. In contrast, most young people indicated that individual agency could only be exercised within limits. For instance, they mentioned that training was sometimes held in distant places that were not easily accessible to young people, especially young women who needed permission from husbands or family elders. Additionally, walking long distances to the district or sub-county offices to seek information did not always guarantee that you would get it, and the possibility of failing to get the information demotivated young people.

The significance of access to information and knowledge in influencing individual outcomes was highlighted by young people who mentioned starting agribusinesses based on training that they had received. For example, some young women mentioned that they started a sweetpotato business after receiving training and some vines from World Vision. New knowledge was also seen as necessary to drive the adoption of value-addition activities among the youth.

Social and economic status

Young men and young women in both districts mentioned that lack of employment limited their ability to accumulate savings and buy assets they could use to start an agricultural production enterprise. They also mentioned that it was difficult for them to access loans to buy land and other assets because they lacked collateral. It was also difficult for them to get loans from community savings groups on merit. This difficulty was because the youth had not accumulated trust in the community. In the case of sweetpotato, there were no credit lines for the crop because sweetpotato was mainly produced for home consumption.

Lack of access to loans also meant that young people who had land and were engaged in agriculture often failed to modernise their enterprise and improve efficiency. Loans were also not always perceived as the best option, especially in the absence of profitable agricultural markets and insurance coverage in the event of losses caused by climate variability. Some youth in Bungatira and Bobi sub-counties indicated that although they could access loans from savings groups, they opted to use their savings to finance sweetpotato production. Reluctance to use loans arose because sweetpotato markets were perceived as unreliable and could result in significant losses and failure to repay loans. Some young people who own land were afraid of using it as collateral for loans because, as one 23-year-old man in Bungatira sub-county stressed, ‘people only have land’, and if that land is taken away because of their failure to repay loans, they would be left with nothing. Many young people indicated that they used the few resources available to them, including, for example, their labour and rudimental tools such as hoes for digging and making mounds for the sweetpotato, instead of using animal traction.

Access to resources varied among young people, resulting in a range of individual outcomes. For instance, those with access to land were better positioned than those without since they did not need to raise money for hiring land. Those with access to labour-saving tools, such as animal traction, were also advantaged. Young men and young women with no access to labour-saving tools often mentioned that they would produce sweetpotato for income only if working in a group because making mounds was labour intensive and overwhelming for an individual farmer.

One way of countering the limitations individuals faced was through collective agency. Collective agency, which often involved working in groups, improved young people’s access to resources and enhanced their participation in agribusiness. Therefore, it is also essential to explore collective agency as one of the factors influencing young people’s participation in agribusiness.

Collective agency: participation in farmer groups

Development agencies have often touted collective action groups as an opportunity to give farmers a voice. The same has also been suggested for young people. For example, in FGDs, young people often mentioned that they needed to be organised in groups to access financial services easily. The Development Finance Company of Uganda Bank (DFCU Bank) and Post Bank were some of the organisations mentioned as offering loans to groups. The Gulu District local government also offered loans and support to youth groups through the Youth Livelihood Programme. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) – for example, World Vision – were also mentioned for organising youth into groups to ease access to agricultural inputs like seeds. There was a massive drive from the government and development agencies for young people to be engaged in collective action groups in order for them to access services. Some young people expressed their desire to join these collective action groups. Thus, it is necessary to outline some of the constraints young people face in farmer groups.

Participation in farmer groups seems to offer young people opportunities to access resources for agricultural production, but, for various reasons, many respondents did not belong to groups. Some said they were not invited to join or preferred to work alone: ‘group work always leaves you behind because some people are lazy and others first concentrate on their farms before the group work’ (24-year-old young man in IDI, Bobi sub-county). In FGDs, young men articulated their issues with farmer groups, which included those related to the structure of groups, power relations, social relationships and trust. They shared that young people are not voted into leadership positions, and, as a result, their ideas are often not considered by older members of the groups. Some young people felt they were used as tools with no equal benefit. Although young people could influence decisions, this depended on how rich they were: ‘If you are rich, you can influence decisions because if a rich member withdraws from the group, it will be affected’ (young man, FGD, Bobi sub-county).

Further, only mature members of the groups (mostly group leaders) were invited to attend training. Also, corruption, for example, inflated costs of inputs or financial mismanagement, had corroded development groups. Corruption led to mistrust amongst the members. Coupled with this, the host youth farmer was responsible for providing meals to fellow members after working in his/her field, which some youth found financially constraining. Conflict of interest resulting from divergent individual needs was also mentioned as a significant obstacle to group coherence.

It was mentioned at all male FGDs that young women’s groups do not face similar challenges to young men’s groups because women are trustworthy. In group discussions, young women mentioned that they elected trustworthy members, opened bank accounts to keep their money safe and used by-laws to guide them. Nevertheless, many of the issues faced by young men were also mentioned by young women, including poor management of funds and corruption, and members failing to service loans and ‘disappearing’. In an interview, one young woman added a gender-specific issue. She said she is not in any farming group because her husband does not allow her to associate with others.

In addition, perceptions of external agencies and service providers about youth were often unfavourable. For example, young people were regarded as highly mobile and sometimes not trustworthy enough compared to older people. Thus, groups with young people alone sometimes faced challenges when accessing some loan products.

Young people stressed the need for equality within groups so that all views are respected, group by-laws are followed, and action is taken against defaulters. Some felt that young people should be in their own groups to minimise conflicts of interest because they face similar challenges. However, other young people appreciated the presence of older people who had the experience to contribute to significant decisions such as drafting the group constitution.

Promoting young people’s participation in sweetpotato production and related businesses: suggestions by young men and young women

Local governments, NGOs and development banks have supported various youth groups interested in farming by providing loans and technical advice. However, study participants perceived that much more could be done to promote youth engagement in agriculture and sweetpotato production in particular. The suggestions included improving access to information and knowledge through establishing information centres, training youth at locations that are more accessible to both young men and young women, and nurturing youth leaders and role models to guide others. The youth also suggested that exposing young people to new technologies through exchange visits would help improve their knowledge.

Some suggested solutions focused on marketing strategies; for example, (1) organising group marketing to improve access to bigger markets outside Gulu; (2) introducing improved and more marketable OFSP varieties; (3) better packaging, diversification and marketing/awareness campaigns; (4) strengthening producer–buyer linkages; and (5) training in post-harvest processing and marketing. Young people also suggested improving access to land by introducing better government policies aimed at minimising the selling of land and empowering committees at the parish level to resolve land-related disputes. Improving physical infrastructures such as irrigation and roads was also considered a way to make marketing and production more efficient.

Young people also suggested that improving their access to start-up loans and training them in managing their finances would enable them to save and invest in assets such as land and equipment. Promoting gender equality by challenging existing gender norms was also seen as critical to ensure that women also have power over the sale of agricultural products. Gender equality could also be promoted by teaching boy children at an early age that it is acceptable for boys to sell sweetpotatoes. Improving farming technologies was also mentioned as a big motivator for youth to participate in sweetpotato production and agribusiness. Some suggested solutions that focused on empowering young people, including organising them so that they demand the kind of services that they need. All these suggestions were seen as ways of promoting youth interest in agricultural enterprises.

Discussion

The above findings demonstrate that national/community context and individual circumstances significantly impact young people’s engagement in sweetpotato production and agribusiness. Individual agency and collective agency play an important role in influencing individual and collective outcomes. These factors interact in such complex ways that there is a need for a multi-pronged approach to promoting young people’s engagement in agricultural production and agribusiness. In addition, it is essential to consider that, as Leavy and Smith state, young people are ‘current members of society, not just citizens of the future’, and also exist ‘in a state of being and not just becoming’ (Citation2010, 5). Therefore, any intervention requires a proper consideration of the current practical needs of the youth as well as future needs and aspirations. Interventions also need to consider the entire value chain – primary production, value addition and input and output markets – since success at each node is highly dependent on the performance of the nodes that come before and after. For instance, in cases where resources for primary production are available, expanding sweetpotato production is hindered by the lack of markets for fresh roots.

Interventions should also be context-specific (Acosta et al. Citation2021) and consider various factors such as age, gender, marital status, level of education and social class that intersect to influence individual and group participation in agricultural production and related businesses. The intersection of these factors has an impact on young people’s agency and their economic outcomes.

Although promoting young people’s engagement in agricultural production and agribusiness is difficult, a study by Kristensen and Birch-Thomsen (Citation2013) demonstrates that success is possible. They found that in some parts of Zambia, when young people considered their prospects of success higher in rural areas than in urban areas, they tended to remain in rural areas where they engaged in agriculture and other enterprises to earn a living. Other studies have shown that young people in SSA can be attracted to agriculture if barriers inhibiting their remunerable engagement are eased (Mulema et al. Citation2021). Indeed, some initiatives to involve young people in agribusiness have yielded success. For instance, efforts to commercialise the dairy and horticultural subsectors, coupled with innovative technologies, have yielded ‘pockets’ of success (Moran Citation2019; Coninx et al. Citation2020). In the sweetpotato subsector, young men and young women are increasingly visible in processing and value-addition enterprises. In Uganda, youth have been gainfully employed in the sweetpotato silage chain through silage processing and marketing (Kabirizi et al. Citation2017; Lukuyu et al. Citation2017). It is through this view that successful interventions are possible that the following discussion engages with the various factors influencing and shaping youth participation in sweetpotato production and agribusiness in Uganda – a country that, according to Martiniello (Citation2015), is often considered the potential breadbasket of Africa. This discussion explores how challenges that young people face could be addressed practically. The section also considers study participants’ suggestions on how to promote young people’s participation in sweetpotato production and related businesses.

Access to land, markets, knowledge and information

Study participants indicated that policies promoting young people’s access to land were important for improving their participation in primary production. While these policies are necessary, it is critical to acknowledge that Uganda is experiencing land shortages (Losch Citation2016; Ripoll et al. Citation2017). Therefore, increasing agricultural production can no longer rely on area expansion. In Asia, increasing land pressure was met with technological change, which ‘increased total agricultural output, and land and labour productivity, despite shrinking farm size’ (Ripoll et al. Citation2017, 170). Introducing relevant technologies could also work in Uganda and other African countries.

Introducing new technologies would require greater youth participation because the youth are potentially more adaptable to change since they can learn new farming technologies faster than their older counterparts. The youth are also keen on employing improved and modern technologies to increase productivity (Goemans Citation2014). Indeed, the study respondents suggested training in new resource-efficient technologies as one of the ways to promote their engagement in agriculture. Therefore, the youth can be targeted with smart technologies such as rapid vine multiplication and improved high-yielding and fast-maturing cultivars, which would also strategically enable them to capture more remunerative sweetpotato vines and root markets (Lukonge et al. Citation2015). These new farming technologies would require substantial equipment, research and training investments. Careful attention would also need to be paid during the design processes to consider context-specific needs and differences in gender and level of education among young people.

In addition to primary production, attention also needs to be paid to value addition. For instance, the support offered to youth in the form of loans by the Gulu and Omoro Districts’ local governments through the Youth Livelihood Programme could focus more on value addition rather than mostly the production, buying and selling of primary products as is currently the case (Gulu District Local Government Citation2019). The value-added products would, in turn, create demand for sweetpotato roots and related sweetpotato products (Sindi, Kirimi, and Low Citation2013).

Increased production and processing would need to be matched with increased access to markets. Gulu and Omoro districts are located near the border with southern Sudan, which has become a major trading route for agricultural commodities (Mugonola and Baliddawa Citation2015). With adequate support from the government and private partners, the farming community in these two districts could potentially ‘tap into this emerging market through increased agricultural production, collective marketing techniques, bulking and value addition to their primary products’ (Mugonola and Baliddawa Citation2015, 123). The youth could act as middle persons between their communities and market centres. In rural settings such as Gulu and Omoro districts, searching for markets often involves travelling long distances on foot, bicycles or motorcycles because of the poor roads and transport systems. Youth are generally more suited for this than older people because of their greater mobility, energy and resilience.

Policies would also need to target the provision of infrastructure in order to improve the entire value chain’s efficiency. For instance, improving road networks and the transport system could potentially reduce labour, transport and storage costs, and improve efficiency in production and marketing. Better infrastructure could also lead to improved access to information and knowledge through increased networking by both physical and digital means.

These interventions would need to be strengthened by training young people and promoting the better organisation of young entrepreneurs and sweetpotato farmers to enhance economies of scale throughout the value chain. In many developing countries, training and ‘access to information and education is often worse in rural areas than in urban areas’ (Goemans Citation2014, 2). Many study respondents had dropped out of school at the primary or secondary level. Studies have shown a link between basic numeracy and literacy skills and improved farmers’ livelihoods (Goemans Citation2014). Formal primary and secondary education can equip young people with basic numeracy and literacy and introduce them to farming as a business. Tertiary agriculture and non-formal education, including vocational training and extension services, can provide youth with more specific agricultural and related knowledge (Goemans Citation2014). Thus, interventions to reduce school drop-out rates would help improve young people’s participation in agricultural businesses. Setting up rural information centres could also help improve access to modern information and communication technologies (ICTs).

In many parts of the world, agriculture is often seen as a last resort for underachievers. It is thus not prioritised, leading to poor development of agricultural curricula or not offering the subject at all (Goemans Citation2014). Indeed, in many parts of Africa, it is common practice in schools and households to use agricultural activities as a punishment, an attitude that harms the aspirations of rural youth (Goemans Citation2014). As a result, there is a need for more considerable effort in transforming the way young people view careers in agriculture, through, for example, highlighting potential role models and success stories.

When suggesting measures to help promote young people’s engagement in sweetpotato production and business, young people in Gulu and Omoro mentioned training in post-harvest utilisation, such as making OFSP products, as well as business skills training. Indeed, acquiring new skills could broaden their opportunities along agricultural value chains and improve their business acumen, which is necessary for the sustainability of agricultural enterprises through effective decision-making.

An important issue raised by study participants is how support is provided to young people, especially the emphasis by government and development institutions on supporting young people working in groups. Although youth groups provide a significant entry point in youth interventions, it may be beneficial to consider that assistance could also target individual young people with proven potential.

Power hierarchies and decision-making

Young people need to be involved in household, community, and national decision-making processes to have a greater sense of ownership of the projects in which they are engaged. Young people in this study expressed their desire to be more involved in decision-making processes so that their needs are considered and that they do not feel like mere ‘tools’ of the older adults.

For many young people in rural Gulu and Omoro, especially young women, the lack of power to make decisions on the use of land, produce and income earned from produce is a critical issue that acts as a barrier to gainful engagement in agriculture. Many young people exercise tactical agency by looking for opportunities outside of the family setting, which are often in the form of short-term low-income casual labour but are still considered worthwhile because they offer more control over income. Given greater access to land, power to make decisions over their produce, and the ability to exercise strategic agency, some young people would be interested in engaging in agriculture as a livelihood option.

Gender and intersectional identities

Although all young people in the study exercise their agency under constrained conditions that limit what they can achieve, young women were at a more significant disadvantage. For example, unlike young men, they were under the control of their husbands or their families, making it difficult for them to take advantage of opportunities. Thus, for young women to be able to express their agency, there is a need for commitment from various stakeholders, including government, NGOs and local authorities or leaders, to challenge gender norms. For young women to have a greater ability to define their goals and act upon them, there is a need for supportive policies and practices on issues such as access to land, loans, education, training and other resources.

Effective considerations of gender and intersectional identities would lead to a mix of targeted interventions. For example, unmarried young women face more challenges in accessing land, which means their opportunities could be away from the land but along the sweetpotato value chain. In contrast, divorced young women with children have better access to land and could, therefore, be targeted with land-based solutions.

Conclusion

This paper sought to discuss and understand factors influencing young men’s and young women’s engagement in sweetpotato production and agribusiness to promote their participation in sweetpotato and other agricultural value chains. The paper focused on the Gulu and Omoro districts, where young people still feel the impact of the two-decades-long war in Northern Uganda. The war resulted in the loss of land access, making it difficult for youth to engage in agribusiness. In addition, generational power relations and gendered social norms that govern how young men and young women in the community behave, and the entitlements they have in relation to accessing socio-economic resources, also impact young men’s and young women’s participation in agribusiness. The complex interactions among national/community contexts and individual circumstances require adopting a multi-pronged approach when promoting the participation of young people in agribusiness. Young people’s successful engagement in agribusiness calls for proactive encouragement and support from their peers, community elders, government institutions, private institutions, and development and other organisations. With support in the form of, for example, access to land, new technologies, equipment, markets and finance, youth in Gulu and Omoro districts may be able to take advantage of the increasing demand for food and farm products, including sweetpotato, in national and regional markets. Better organisation of youth groups could enhance economies of scale throughout production and marketing processes, reduce risk and transaction costs, and improve access to resources such as funding. Additionally, the provision of public goods, including infrastructure, research, information, education and capacity building, would go a long way in reducing risks, thus opening up spaces for youth to participate more efficiently and effectively in sweetpotato production and agribusinesses. In all this, young women would require more targeted interventions since they are at a more considerable disadvantage than young men in terms of employment, education, and access to information, land, and finance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Norita Mdege

Norita Mdege (PhD) is a research fellow at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. She has a PhD in film studies from the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Her current research explores the representations of women politicians in Africa as a means to understand how such representations may impact their claims to political legitimacy. She is also working on a book-length project that explores the representations of African women and girls in films about African anti-colonial and postcolonial conflicts. Her areas of interest include gender studies, women and girls in Africa, youth studies, political conflict, African cinemas and cultural politics.

Sarah Mayanja

Sarah Mayanja is an agricultural market specialist with a wealth of experience in improving commodity value chains in the East and Central African region. She currently works as a gender researcher with the International Potato Center (CIP) and is based in Uganda. She has designed and conducted studies in gender-responsive breeding, seed systems, postharvest management, nutrition and value chains for roots, tubers and bananas. Her work spans the Sub-Saharan region. She is currently pursuing a PhD in agro ecology and livelihood systems at the Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda. She is a fellow of African Women in Agriculture Research and Development (AWARD).

Netsayi Noris Mudege

Netsayi Noris Mudege (PhD and MA in sociology and social anthropology) is a senior scientist at WorldFish based in Zambia. She has extensive science leadership and project management experience. Currently, she is managing several donor-funded research for development projects in Zambia and Malawi. Her current work focuses on developing inclusive business models for smallholder farmers, engagement of the private sector in markets, input supply and climate information services, gender equality, social inclusion and nutrition. She is responsible for liaising with donors and partners to ensure the smooth running of the projects. Before joining WorldFish, she worked as a Gender Research Coordinator for CGIAR’s Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB) and was based in Lima, Peru, before moving to Nairobi. She provided science leadership for the gender work in the programme and supervised and coordinated the work of teams in four CGIAR centres across Africa, Asia and Latin America. She managed and coordinated a global research programme on gender equity and youth employment for RTB. Before joining CIP/RTB, she was a gender advisor at the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam (KIT).

Bibliography

- Acosta, M., M. van Wessel, S. van Bommel, and P. H. Feindt. 2021. “Examining the Promise of ‘the Local’ for Improving Gender Equality in Agriculture and Climate Change Adaptation.” Third World Quarterly 42 (6): 1135–1156. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.1882845.

- African Union. 2006. “African Youth Charter.” African Union. https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7789-treaty-0033_-_african_youth_charter_e.pdf

- Ahaibwe, G., S. Mbowa, and M. M. Lwanga. 2013. “Youth Engagement in Agriculture in Uganda: Challenges and Prospects.” Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC). https://www.africaportal.org/publications/youth-engagement-in-agriculture-in-uganda-challenges-and-prospects/

- Ameyaw, D. S., and E. Maiga. 2015. “Chapter 1: Current Status of Youth in Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Africa Agriculture Status Report: Youth in Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by Tiff Harris, Vol. 3, 14–35. Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). Nairobi, Kenya: TH Consulting Publisher.

- Coninx, I., C. Kilelu, A. Kingiri, S. Kimenju, and A. Numi. 2020. “Counties as Hubs for Stimulating Investment in Agrifood Sectors in Kenya: A Review of Aquaculture, Dairy and Horticulture Sectors in Selected Counties.” Wageningen Environmental Research. https://edepot.wur.nl/522332

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–167. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Goemans, C. 2014. “Access to Knowledge, Information and Education.” In Youth and Agriculture: Key Challenges and Concrete Solutions, 1–17. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy; Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA), Wageningen, The Netherlands; and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3947e.pdf

- Gulu District Local Government. 2019. “Gulu District Profile.” Gulu District Local Government. https://www.gulu.go.ug/sites/files/GULU%20DISTRICT%20PROFILE%202019_0.pdf

- Hamilton, A. B., and E. P. Finley. 2020. “Qualitative Methods in Implementation Research: An Introduction.” Psychiatry Research 283: 112629. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112629.

- Honwana, A. 2006. Child Soldiers in Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- iDMC. 2008. “Uganda: Uncertain Future for IDPs While Peace Remains Elusive.” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/7DE46F017E64AC4785257435005D3384-Full_Report.pdf

- Joireman, S. F., A. Sawyer, and J. Wilhoit. 2012. “A Different Way Home: Resettlement Patterns in Northern Uganda.” Political Geography 31 (4): 197–204. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.12.001.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

- Kabirizi, J. M. P. M. Lule, J. F. Ojakol, D. Mutetikka, D. Naziri, G. Kyalo, S. Mayanja, and B. A. Lukuyu. 2017. “Sweet Potato Silage Manual for Smallholder Farmers.” https://hdl.handle.net/10568/82747

- Kristensen, S., and T. Birch-Thomsen. 2013. “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Rural Youth Employment in Uganda and Zambia.” International Development Planning Review 35 (2): 175–201. doi:10.3828/idpr.2013.12.

- Leavy, J., and S. Smith. 2010. “Future Farmers: Youth Aspirations, Expectations and Life Choices.” Future Agricultures Consortium. https://www.youthpower.org/sites/default/files/YouthPower/resources/Future%20Farmers.pdf

- Losch, B. 2016. “Structural Transformation to Boost Youth Labour Demand in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Agriculture, Rural Areas and Territorial Development.” Working Paper No. 204; EMPLOYMENT. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_533993.pdf

- Lukonge, E. J., R. W. Gibson, L. Laizer, R. Amour, and D. P. Phillips. 2015. “Delivering New Technologies to the Tanzanian Sweet Potato Crop through Its Informal Seed System.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 39 (8): 861–884. doi:10.1080/21683565.2015.1046537.

- Lukuyu, B., P. Lule, B. Kawuma, and E. Ouma. 2017. “Feeds and Forage Interventions in the Smallholder Pig Value Chain of Uganda.” https://hdl.handle.net/10568/80379

- Martiniello, G. 2015. “Food Sovereignty as Praxis: Rethinking the Food Question in Uganda.” Third World Quarterly 36 (3): 508–525. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1029233.

- Moran, T. H. 2019. “FDI and Supply Chains in Horticulture: Diversifying Exports and Reducing Poverty in Africa, Latin America, and Other Developing Economies.” Thailand and the World Economy 37 (3): 1–24. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/TER/article/view/220659/152460.

- Mudege, N. N., R. Bullock, and A. Rietveld. 2017. “Gender Equitable Employment and Youth Kick Off Cluster Meeting.” Workshop Report. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/83234

- Mugonola, B., and C. Baliddawa. 2015. “Building Capacity of Smallholder Farmers in Agribusiness and Entrepreneurship Skills in Northern Uganda.” Agricultural Information Worldwide 6: 122–126.

- Mulema, J., I. Mugambi, M. Kansiime, H. T. Chan, M. Chimalizeni, T. X. Pham, and G. Oduor. 2021. “Barriers and Opportunities for the Youth Engagement in Agribusiness: Empirical Evidence from Zambia and Vietnam.” Development in Practice 31 (5): 690–706. doi:10.1080/09614524.2021.1911949.

- Pelenc, J., D. Bazile, and C. Ceruti. 2015. “Collective Capability and Collective Agency for Sustainability: A Case Study.” Ecological Economics 118: 226–239. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.07.001.

- Pincock, K., and N. Jones. 2020. “Challenging Power Dynamics and Eliciting Marginalized Adolescent Voices through Qualitative Methods.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940692095889. doi:10.1177/1609406920958895.

- Richards, T. J. 2022. “Agribusiness and Policy Failures.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 44 (1): 350–363. doi:10.1002/aepp.13205.

- Rietveld, A. M., M. van der Burg, and J. C. J. Groot. 2020. “Bridging Youth and Gender Studies to Analyse Rural Young Women and Men’s Livelihood Pathways in Central Uganda.” Journal of Rural Studies 75: 152–163. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.01.020.

- Ripoll, S., J. Andersson, L. Badstue, M. Büttner, J. Chamberlin, O. Erenstein, and J. Sumberg. 2017. “Rural Transformation, Cereals and Youth in Africa: What Role for International Agricultural Research?” Outlook on Agriculture 46 (3): 168–177. doi:10.1177/0030727017724669.

- Rodriguez, J. K. 2018. “Intersectionality and Qualitative Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions, edited by C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe, and G. Grandy, 429–461. Los Angeles/London/New Delhi/Singapore/Washington DC/Melbourne: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781526430212.n26.

- Sindi, K., L. Kirimi, and J. Low. 2013. “Can Biofortified Orange Fleshed Sweet Potato Make Commercially Viable Products and Help in Combatting Vitamin a Deficiency?.” 4th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, Hammamet, Tunisia. September 22-25, 2013. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.161298.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2017. “Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series: Gulu District, Kampala, Uganda.” Uganda Bureau of Statistics. https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/2014CensusProfiles/GULU.pdf

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2021a. “2021 Statistical Abstract.” https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/01_20222021_Statistical_Abstract.pdf

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2021b. “Annual Agricultural Survey 2019: Key Findings.” https://www.ubos.org/?pagename=explore-publications&p_id=2

- Vastapuu, L. 2018. Liberia’s Women Veterans: War, Roles and Reintegration. London: Zed Books.

- Whyte, S. R., and E. Acio. 2017. “Generations and Access to Land in Postconflict Northern Uganda: “Youth Have No Voice in Land Matters”.” African Studies Review 60 (3): 17–36. doi:10.1017/asr.2017.120.

- Zawedde, B. M., C. Harris, A. Alajo, J. Hancock, and R. Grumet. 2014. “Factors Influencing Diversity of Farmers’ Varieties of Sweet Potato in Uganda: Implications for Conservation.” Economic Botany 68 (3): 337–349. doi:10.1007/S12231-014-9278-3/TABLES/3.