Abstract

The article makes the case for a distinctive intellectual tradition of the industrial policy paradigm to examine state strategies in the twenty-first century. Specifically, it outlines three key lessons for political economy scholarship: first, it points to the need to study complementary institutions and the longer-term horizon in political cycles; second, it notes that scholars must seek innovative methodologies in examining sectoral development; and, third, it calls for a rethinking of state capacity in the new phase of globalisation, marked by strategic competition and neo-mercantilism. In so doing, the article opens a new research agenda for the next generation of scholars focussed on how industrial policy might help – or fail – to promote the creation of new comparative advantages and the advancement of internationally competitive firms and sectors, and, importantly, to deliver better quality of life for citizens in most of the Global South.

A ‘true industrial policy’ or technology and innovation policy (TCP) follows three key principles … first, state intervention to fix market failures and focussed on creating domestic producers within the initial comparative advantage; second, export orientation which contrasts to import substitution in the 1960–1970s; and the pursuit of fierce competition abroad and domestically with strict accountability.Footnote1

Perhaps to the surprise of many, the study quoted here was published in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper Series. While far from reflecting the official stance of the organisation, its significance within the IMF lies in the indicative shift in immediately rejecting industrial policy as a development strategy. Major multilateral institutions’ acceptance of the role of state activism in structural transformation reinforces the overall objective of the present research project. For the Bretton Woods institutions, industrial policy can be designed in ways that promote strategic support for competitive firms, but these organisations remain defensive of the market rule as the most optimal strategy for the Global South. Yet this collection of articles sought to legitimise industrial policy as a way of understanding state strategies (Nem Singh Citation2023) and changing state–market relations in the era of contemporary globalisation. All the authors posit a more political approach in explaining the ways states intervened in markets and penetrated domestic societies to reinforce a savings-oriented and collective mindset.

This epilogue closes the collection by way of achieving two objectives: first, it offers a genealogy of the intellectual tradition of industrial policy to contextualise the contribution of this volume in the wider political economy scholarship; and, second, it identifies the lessons from this collection as the field develops to respond to new challenges in the twenty-first century.

Industrial policy agenda – overcoming Eurocentrism in political economy?

The intellectual tradition of industrial policy can be traced to the experience of so-called late industrialisers, notably Japan and Germany, who attempted to catch up with other countries in Western Europe. Friedrich List’s (Citation1841) concept of economic mercantilism and Alexander Gerschenkron’s (Citation1962) notion of economic backwardness were the cornerstone of state-led development strategies, which heavily influenced political economy debates about industrialisation during the twentieth century. In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, economic nationalism and its diverse forms were rolled back as neoliberal economists repudiated state intervention and international financial institutions (IFIs) promoted structural adjustment in response to the debt crisis. For three decades, market reforms emerged as the solution to rent-seeking, corruption, and what was then perceived as arbitrary government interference (Krueger Citation2002), which, rightly or wrongly, have been associated with USSR planning, Chinese communism, and even East Asian developmentalism (Helleiner Citation2021).

The return of industrial policy in mainstream political economy debates is now clear in both development theory and praxis, and there are several reasons for the silent return of industrial policy, and state activism more widely, in the twenty-first century. At the start of the new millennium, Dani Rodrik (Citation2002, Citation2006) hailed the decline of political support and erosion of intellectual consensus around neoliberal globalisation, articulated through the Washington Consensus doctrine. In Latin America and East Asia, industrial policy was not fully dismantled as a development strategy nor were its intellectual predecessors fully erased within the political economy scholarship. For instance, the return of state activism was marked by the political contestation over market reforms and the simultaneous articulation of neo-developmentalism and other forms of post-Keynesian political economy (Ban Citation2013; Flores-Macías Citation2012). Yet what would replace free-market orthodoxy was not very apparent to scholars and policymakers. To some extent, this hinged on the resistance within the core economies, notably in the European Union and United States, to designing new growth strategies within the architecture of the nation state. On the one hand, there was significant acknowledgement of the negative effects of neoliberalism and how market liberalisation policies failed to deliver stable economic growth and even exacerbated existing forms of inequalities (Crouch Citation2011; Milanovic Citation2016). On the other hand, the lack of an alternative paradigm imposed a straightjacket in rethinking the capacity of market mechanisms to alleviate the worst effects of economic crises and deliver long-term economic growth (Bulfone Citation2023; Hay Citation2020). The near absence of paradigm shifts within the core economies constrained intellectual creativity over how to theorise experiences of countries not conforming with the liberal market narrative. This led Crouch (Citation2011) to lament the non-death of neoliberalism, despite its shortcomings as a paradigm for economic resilience.

Various disciplines were equally caught up in debates about neoliberal globalisation. As late as the 2010s, geographers were still discussing the variegated forms of neoliberalism and how markets transformed urban landscapes (Brenner, Peck, and Theodore Citation2010; Knio Citation2019; Piletic Citation2019). The research agenda undoubtedly shed light on the complexity and hybridity of neoliberalism as a way of organising political and economic life and as a structural condition affecting the social fabric of societies. However, geographical scholarship has suffered from theorising the institutional dimensions and politics of state–market relations gradually being forged as geopolitical shifts began to alter the role of state power in the global political economy. Left undertheorised was the on-going state transformation in East Asia and Latin America, whereby the return of the state in finance, industrial relations, investment, and even social welfare was empirically conspicuous yet often analysed in atheoretical terms (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012; Ohno Citation2013; Rodrik Citation2006, Citation2008). For others, neoliberal globalisation appears to be an inevitable exogenous force imposed on domestic societies. Despite evidence of the creative fusion of state-led innovation and market mechanisms, such empirical observations were often framed in terms of continuity of neoliberalism, rather than exploring variegated forms of statism found outside the Western world (Flores-Macías Citation2012; Madariaga Citation2020). Although there have been recent efforts to rethink how state capitalism becomes unevenly adopted through sovereign wealth funds and hybrid forms of ‘state capital’ (Alami et al. Citation2022; Alami, Dixon, and Mawdsley Citation2021), their work simply lacks the tools to advance institutionalist analysis and political economy scholarship concerned about state transformation in the post-neoliberal age (Toby and Jarvis Citation2017; Nem Singh Citation2022).

Finally, the advancement of austerity politics in Europe dominated analysis of the 2008 financial crisis and its consequences for world politics (Crouch Citation2011; Hay Citation2004). In an important book, Campbell and Pedersen (Citation2001) called for political economists to examine institutional change associated with market deregulation, state decentralisation, and reduced political intervention in national economies. In subsequent publications, economic sociology and political economy were preoccupied with understanding how institutions adapted to economic globalisation, including the role of knowledge regimes in making ideas stick within organisational structures, thereby ensuring the continuity of ideas related to neoliberalism and free markets (Campbell Citation2004; Campbell and Pedersen Citation2014). Major political economy journals were equally complicit in how knowledge production skewed away from a pluralist political economy. Publications dealing with political economy and institutionalist analysis drew evidence from the experience of core economies, especially on austerity politics after 2008. While editors of leading international political economy (IPE) journals have gradually recognised this bias – as evidenced by two special issues on ‘IPE blind spots’ (Best et al. Citation2021; LeBaron et al. Citation2021) – the question of what constitutes a ‘global’ or ‘international’ political economy remains deeply skewed in research areas that have ramifications for the Global North. Such gaps, in turn, fail to capture broader political economy dynamics – such as de-industrialisation, commodity specialisation, and expansion of informal low-productivity services – which are more commonplace in the developing world (Rodrik Citation2016; Storm Citation2015). The narrow concerns of the political economy scholarship led to renewed calls for pluralist political economy scholarship (eg see Hobson Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2020 on critical historiography).

Those political economists studying the non-Western world often found themselves required to justify emerging forms of neo-developmental projects as actually existing political projects worthy of publishing in mainstream disciplinary journals (Nem Singh Citation2014, Singh Citation2022; Nem Singh and Ovadia Citation2018; Ovadia and Wolf Citation2018). The place of critical work, particularly about the rise of industrial policy, has largely found a home in development studies and critical political economy, such as the papers published in Third World Quarterly, Development and Change, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade and, recently, World Development, to name a few.Footnote2 In this context, there was – and sometimes still is – resistance to framing a pluralist political economy that can capture diverse experiments with industrial policy in emerging market economies in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. The pivotal moment was 2013, when China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Concepts like state capitalism and developmental states then regained visibility, which gradually led to a debate on alternatives to neoliberalism as a growth strategy.

Confined initially within China studies, which often claims exceptionalism in its subject area, the political economy literature had to recognise the following (based on Z. Chen and Chen Citation2021; H. Chen and Rithmire Citation2020; L. Chen and Chulu Citation2023; Nem Singh and Chen Citation2018; Tsai Citation2007; Tsai and Naughton Citation2015):

New forms of financing development projects, particularly through development banks, sovereign wealth funds and state-led finance;

The spectacular ‘return’ of industrial policy and even national planning in order to synchronise and coordinate state and private sector responses in the Global South as Chinese capital flooded their capital markets, infrastructure and natural resource sectors;

The establishment of international institutions that challenged donor agencies and financial lenders as the primary source of lending for African, Latin American and Southeast Asian countries.

The debate persists over the extent to which China’s socialism with capitalist traits can be replicated, scholars have widened the parameters for a dynamic comparative-historical analysis – and have sometimes even challenged mainstream authors’ understanding of China and the resilience of its economic system, amidst the plethora of scepticism over the country’s development model and recent shifts in strategy under Xi Jinping.

My objective in tracing the genealogy of industrial policy in the twenty-first century as an intellectual project is to help a new generation of scholars contextualise their political economy scholarship, especially those emphasising the dynamics of economic development in the non-Western world. In the past, scholars discussed industrial policy – and the developmental trajectories of the Global South – as a state of exception, or even marginal, in the field of political economy (see Best et al. Citation2021; LeBaron et al. Citation2021). Yet shifting geopolitics have reshaped the intellectual terrain. The ascent of China has informed contemporary views on the validity of industrial policy as a development strategy and the legitimacy of state capitalism as a distinctive – if not alternative – model of adaptation to economic globalisation. Yet scholars studying Chinese political economy have been cautious about what precise lessons should be drawn from the market reform processes in China, while others sought to identify core issues, such as corruption and state-induced rent-seeking, as potential obstacles to a sustainable trajectory of inclusive development (Ang Citation2016, Citation2020; Tsai Citation2007; Wedeman Citation2012).

Moving forward, this epilogue recognises the diverse experiences in designing industrial policies in the twenty-first century, which embrace the distinctive political economy dynamics in the Global South. These accounts of state capitalism and industrial policy share a common objective of promoting the legitimisation of industrial policy as a development strategy. As papers in this volume attests, the ‘return of the state’ is not simply a rehearsal of past developmentalist projects. The challenges are different, rendering some of the old developmentalist strategies obsolete in addressing new problems. For instance, although manufacturing remains crucial for structural transformation, developing societies face gaps in productivity, skills and labour upgrading, and excessive dependence on the raw materials sector when compared with East Asia and the West. In addition, the digitalisation of industries and shift towards a knowledge economy make catching up more complicated for developing countries. These imply a need to rethink the core principles of industrial policy if it is to remain relevant as a development strategy in the succeeding decades.

Lessons from the volume

This collection offers three key lessons that develop the conversation about the new industrial policy in the post-neoliberal era:

The need for complementary institutions and a longer-term horizon in political cycles;

Finding innovative methodologies in studying sectoral development;

Rethinking state capacity in the new phase of globalisation.

Lesson 1: the need for complementary institutions and a longer horizon in political cycles

The empirical research in this collection on East and Southeast Asia – by Chen and Chulu (Citation2023), on China; by Camba, Lim, and Gallagher (Citation2022), on Malaysia and Indonesia; and by Schlogl and Kim (Citation2023), on Indonesia – demonstrates the less salient role of polities and regime types in determining industrial policy formulation. Analysing regime type by itself reveals little about how and under what conditions state capabilities for policy implementation are crafted towards industrial strategies. Instead, what matters more is the coalitional foundations of industrial policy and, indeed, whether centralised institutions are better at sustaining structural transformation. In the developmental state literature, democracies are deemed less compatible with industrial policy. Industrial catch-up was conceived as a domestic survival strategy in a period of remarkable geopolitical uncertainty, which in turn justified the mutually beneficial relationship between states and big business (Doner, Noble, and Ravenhill Citation2021; Doner, Ritchie, and Slater Citation2005; Yeung Citation2017). However, as Adnan Naseemullah (Citation2022) illustrates through Indian sectoral development policies, the success in crafting industrial policies for structural transformation hinges on how the pursuit of market reforms during the neoliberal decades has entrenched specific power relations by empowering transnational companies with more autonomy and capacity, limiting the national state in its support and guidance of domestic champions (see also Naseemullah Citation2017). This, in turn, renders industrial policymaking less effective compared to export-oriented manufacturing in East Asia and Latin America during the twentieth century. Put simply, our collection advocates for a return to the ‘structural’ conditions enabling industrial policy design and implementation.

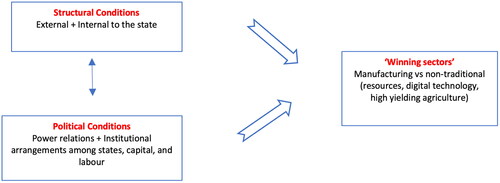

Moving forward, we need more fine-grained research on how structural factors impact directly or indirectly on the national state and domestic political dynamics to better understand the policy choices over which sectors are deemed important for structural transformation. Traditionally, political economists rely on historical scholarship to identify sectoral development policies. We often draw lessons from the East Asian Tigers because their policy choices appear obvious: export-driven manufacturing to upgrade from labour-intensive, but less technologically demanding, sectors towards building technology-intensive sectors. In the twenty-first century, economic globalisation alters the logic of state action from one based on national self-sufficiency to globalised market integration as an upgrading strategy. In this regard, China is a crucial example of structural transformation. As Chen and Chulu (Citation2023) show, the centralised state coordinated a complex set of policies to move from state planning into market-building institutions. The broader scholarship of Chinese political economy emphasises how political competition at the regional level (Ang Citation2016, Citation2018) and choices over sectoral promotion policies (Z. Chen and Chen Citation2021; Hsueh Citation2011) can induce structural transformation. We need additional country cases and sectoral perspectives to examine how countries might upgrade their sectors and face global competition (eg Sinha Citation2016; others) and draw together comparative lessons, as summarised in .

Lesson 2: finding innovative methodologies in studying sectoral development

The authors of the collection are a mixture of quantitative and qualitative researchers working in the field of political economy. Nearly all the papers emphasised the need to examine specific sectoral interventions: Camba, Lim, and Gallagher (Citation2022) on different logics of Chinese capital-driven industrialisation strategies; Chen and Chulu (Citation2023) on China’s industrial policy; Naseemullah (Citation2022) on Indian sectoral development and foreign direct investment (FDI) promotion strategies. By contrast, Hauge’s (Citation2023) dual focus on the productivity-enhancing effects of manufacturing and the challenges of digitalisation for industrial upgrading are a call for future researchers to examine how sectoral policies are designed to make them ‘fit for purpose’ in the new phase of economic globalisation. While Hauge (Citation2023) re-asserts the significance of manufacturing due to its multiplier effects on economic diversification and technological innovation, there appears to be a narrowing ‘developmental space’ in which poorer low-income countries can manoeuvre and leverage in their pursuit of their own pathway for industrialisation (Aiginger and Rodrik Citation2020; Wade Citation2003).

Some indicative research here might require a reinterpretation of the new geopolitical environment. On the advent of China’s economic expansion through the BRI, economic diversification policies are back on the agenda. For instance, Kazakhstan’s geostrategic role in the BRI has enabled the renegotiation of investment packages in food processing, automotive manufacturing, and even new investments in critical minerals and hydrocarbon industries. Some have argued that a multi-vectoral approach to foreign policy and economic diplomacy has rendered some relative success for Kazakhstan in rebalancing its ties with foreign powers and finding strategic advantage for its national interests (Bitabarova Citation2018; Tjia Citation2020). Grappling with the failure of deploying BRI relations for strategic industrial policy, sobering assessments persist over Pakistan’s Economic Corridor investment package and Sri Lanka’s non-negotiable long-term leasing of its ports to China. In both cases, discussions on debt management cast a large shadow of doubt over their successes in utilising Chinese capital for strategic state intervention. Nevertheless, China’s neo-mercantilist approach to economic diplomacy is increasingly contested as a strategy to enhance a dependent development model. While some scholars have drawn some parallels between China’s new global strategy of overseas expansion through its national champions and the old tributary system during the heyday of the Middle Kingdom (Hobson Citation2020; Kang Citation2010; Feng Citation2009), it is worth noting that mercantilism and economic nationalism more generally have often been designed to create dependency (see Hirschman Citation1945).

Beyond China, however, the broader geopolitical context has radically changed in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. A worrisome trend started with the administration of President Donald J. Trump (2017–2021), which has promoted the reshoring of manufacturing and decoupling from China-linked supply chains through neo-mercantilist policies (Nem Singh Citation2021). In response to growing fears of Chinese control over critical minerals needed for clean energies, military and defence, and advanced manufacturing sectors, the European Union (EU) as well as South Korea and Japan followed suit with new industrial policies aimed at securing their industrial competitiveness. From a development perspective, strategic competition among industrialised countries is creating a race for subsidies and technological protectionism, which can serve as further obstacle to the industrialisation of the Global South.Footnote3 Given the relative disadvantage of mineral producers and developing countries more widely in terms of technological capabilities, the challenge of moving up the value chains and developing niche technologies for emerging sectors are formidable.

Lesson 3: rethinking state capacity in the new phase of globalisation

Since political cycles and temporal orientation of policymaking co-shape state capacity to pursue coherent industrial policies in the twenty-first century, we need more fine-grained analysis on what types and scope of state activism are required to undertake structural transformation. On the one hand, Jostein Hauge (Citation2023) re-emphasises the need to study manufacturing and emerging challenges around its expansion in the Global South. On the other hand, Michael Odijie (Citation2023) recasts the ‘national capacity’ concept in light of the generalised movement towards regional market integration as Africa’s response to economic globalisation. Critically, Odijie (Citation2023) points out the incompatibility of goals and motives between transnational and domestic development strategies since such policies are embedded in contrarian logics of governmental actions.

As political support for neoliberalism wanes, industrial policy is increasingly perceived as a legitimate strategy for global competition. Yet two decades of market reform have hollowed out the productive bases of many developing countries. Consequently, the rise of ‘competition’ or the ‘regulatory state’ effectively disenfranchised various development agencies of their capabilities to monitor, regulate and steer private sector actions. Moving forward, there is growing interest among policymakers on how to expand the productive capabilities of domestic companies, and, in turn, enable new market players to participate in the global supply chain of manufacturing goods. As an exemplar of excellent scholarship, Doner, Noble, and Ravenhill (Citation2021) examine:

What explains different industrial strategy approaches of East and Southeast Asian countries;

How varying state capabilities influenced the decision to undertake specific industrial pathways within automotive manufacturing;

Successful strategies that built internationally competitive national champions.

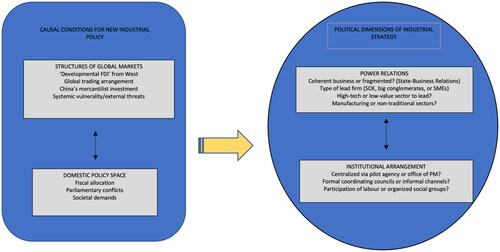

Looking to the twenty-first century, we need to expand the industrial policy scholarship towards emerging industries that can form the new productive base of structural transformation in the Global South. For instance, accelerating demand for critical minerals to achieve the renewable energy transition has already opened new doors for mineral producers to rethink their mining policies and align them towards broader national industrialisation agendas (Nem Singh Citation2021). Importantly, China and other countries have invested heavily in technology-intensive sectors, such as high-speed transport, information technologies, and new energy vehicles (NEVs). Such cutting-edge industries are fast becoming the fault lines of geo-economic competition but, importantly, are forging new geopolitical rivalries. Notwithstanding the political and security perspectives associated with the technology race, we need a political economy perspective to capture the opportunities and challenges for structural transformation, especially for countries stuck in the middle-income trap (Doner and Schneider Citation2016; Naseemullah Citation2022) or, worse, those with very limited productive capabilities. In brief, we must rethink the kinds of institutional capacities needed for developing countries to adapt more effectively to the external challenges in the twenty-first century. Some of these questions were partially answered in our collection, but the task is formidable. provides some indicative conceptual tools that can be deployed by future scholars to fully incorporate the question of politics, institutions and power in the study of industrial policy in the post-neoliberal age.

Figure 2. Schematic framework on how to study industrial policy in the twenty-first century. Source: Author’s summary of papers in the collection and literature review on industrial policy. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), state-owned enterprises (SOEs), small and medium enterprises (SMEs), Prime Minister (PM).

Industrial policy in the age of ‘slowbalisation’

This final section advocates a multi-vectoral approach in development theory and praxis as political leaders, civil society activists and the public grapple with highly complex global problems, such as the undeniable effects of climate change, the increasing politicisation and weaponisation of natural resources that is accelerating geopolitical rivalries, and the divergent pathways of energy transition and growth models found outside the Western world.Footnote4 In the context of climate emergency, the carbon-intensive, fossil-fuel-based models of growth we have rigorously studied over the decades have brought us into a ‘carbon lock-in’ modality that has become an obstacle in the shift to clean energy. Lessons for decarbonisation and green growth, in turn, must come from elsewhere.

The first quarter of the twenty-first century is, indeed, marked by immense geopolitical uncertainty punctuated by an ever-growing concern over the lack of a clear pathway to resolve the climate crisis. In most parts of the developing world, in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the twin commitment to free market orthodoxy and carbon-intensive growth strategies was unquestioned. Beginning with the nadir of traditional domestic demand-driven models based on Keynesianism, the neoliberal revolution swept the world with its emphasis on unfettered trade, the positive role of (Western) FDI in promoting economic development and, crucially, the proximate relationship between neoliberalism and pluralist democracies. Yet, as the gravity of economic power shifts away from the West, it has become patently clear that Margaret Thatcher’s famous ‘There is No Alternative’ (TINA) slogan was not as inevitable as it appeared to be. By the early 2000s, parties and political leaders of the left in Latin America swept the continent arguing for a new social contract that not only strengthens an activist role for the state in the economy, but also demands more inclusive forms of citizenship and social development (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012; Pickup Citation2019). Perhaps less conspicuous but no less consequentially, in Asia Pacific the slow return of state-led forms of financing became the dominant mode of political economy models, including the establishment of sovereign wealth funds, the rise of national champions in global markets and, crucially in the case of China, the recalibration of power in favour of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Kim Citation2018, Citation2021; Thurbon Citation2016; Thurbon and Weiss Citation2021; Tsai and Naughton Citation2015).

Twenty years since this experimentation began, we have now entered a new era. Gone are the days when industrial policy experts would need to defend the very concept of state intervention as a mode of governance. As Milanovic (Citation2016) argues, economic globalisation has brought opportunities and challenges across the world. On the one hand, poverty reduction and sustained growth became the hallmark of the Asian Tigers and others that followed suit. On the other hand, greater inequalities and inter-class political conflict have become more pronounced in both the advanced industrialised countries and the developing world. Indeed, development strategies were implemented in ways that created winners and losers in the globalisation game. Further, from the uneven benefits of economic development emerged an alternative to the Washington Consensus as the developmental state or state capitalist model (depending on one’s scholarly inclinations) became more clearly articulated among political economists, particularly focussed on the case of China (Ang Citation2016; Z. Chen and Chen Citation2021; H. Chen and Rithmire Citation2020; Heberer Citation2016). While the centralisation of power – often attributed to the authoritarian resilience of the contemporary Chinese state – is conceived as a key feature of this model, emphasis must be placed on the difficult process of building institutional complementarities to rebalance the relationship between states and markets (see Chen and Chulu Citation2023). Perhaps worth mentioning is the unintended effect of studying industrial policy – ie the growing acceptance and legitimation of industrial policy in the mainstream intellectual landscape as a strategy for economic globalisation even in the West (Aiginger and Rodrik Citation2020; Bulfone Citation2023). Finally, and combining the two insights above, the rise of China as an economic powerhouse has opened new relationships with developing countries. Not only has China offered new sources of finance, trade and investment, particularly during a period of economic contraction in the West, but the ambitious BRI has cemented a new vision for China and its global politics of engagement (Cai Citation2018; Carmody and Wainwright Citation2022; B. Duarte and Ferreira-Pereira Citation2022).

These changes in relation to strategic competition must be understood as a backdrop to the clear signals in the debate on climate change responses. With the benefit of hindsight, we have at least successfully moved from climate change denial in the early 2000s towards a growing consensus on climate change in the Anthropocene. Fuelled by civil society and activists compelling immediate climate action, an urgent imperative to shift to a low-carbon energy system became the rallying point for resistance and mobilisation (Hoberg Citation2021). Within the political economy literature, green growth emerged as the operating concept to resolve the economic growth–environment dilemma. In an important contribution, Fiorini (Citation2018, 6–8, 18–20) outlines the concept of green growth to navigate through the complex relationship between economic growthFootnote5 and ecological limits. Economic growth in some form will continue to occur, and this is inevitable, necessary and desirable. However, the composition and trajectory of economic growth must change in response to objective ecological limits. Such changes are wide-ranging and encompass, among other things, moving from fossil fuel to renewable energy systems; achieving greater efficiency in water, energy and materials use; protecting land from further extensive development; adopting new models of urban development; and promoting large-scale green infrastructure. Thus, energy transition pathways across countries are likely to be shaped by idiosyncratic factors, such as industrial and domestic market structures, the balance of power between states and relevant economic groups who are likely to become losers and winners in the transition, and the geopolitical/external contexts directly shaping elite decisions, notably their position over US–China relations and the influence of corporate power, especially towards developing countries.

Conclusions: from crisis to opportunity for industrial policy

In closing this research, the collection should be seen as an invitation for the next generation of scholars to be forward-looking and to focus on how industrial policy might help – or fail – to promote the creation of new comparative advantages, support the advancement of internationally competitive firms and sectors, and, importantly, deliver better quality of life for citizens in most of the Global South. This research agenda will thus remain significant for development studies as a discipline. Our project on industrial policy merely offers a first step towards advancing political economy scholarship that is inherently pluralist in approach by way of building on the lessons but also looking beyond the East Asian experience of industrial success. For future researchers, these new challenges – climate change, energy transition, strategic competition – are inevitably consequential for state–market relations. Yet we need to build new knowledge about how success and failure in industrial upgrading in the past century can offer some clues of how to rebalance economic nationalism and mercantilism for industrial success while also effectively addressing rather than stifling cooperation and efforts aimed at grand challenges.

The most significant challenge is undeniably our global response to the climate crisis. The failure to address climate change hinges on market failures and carbon lock-in – both of which are key features of the growth strategies designed to accelerate industrialisation during the twentieth century. Climate change is a market failure in that carbon is mispriced. As Rodrik (Citation2014, 470–71) argues, the extensive presence of fossil subsidies and the failure to implement taxes or controls to internalise the risks of climate change have lowered the actual cost of carbon and detached fossil fuels from longer societal perspectives. The private return to green technologies is deemed significantly below the social return, thereby inducing incentives towards a carbon lock-in. Unless governments internalise the global benefits of carbon taxes and controls, the tendency remains to choose fossil fuel over green technologies. Even with an environmental crisis on the horizon, the rationale for countries to invest in clean energy technologies might not be strong enough for countries to willingly pay a higher premium to achieve a green energy transition.

However, the worldwide transition to clean energy technologies is now deemed an imperative for global collective action in response to the climate crisis. In the 2021 Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, political leaders affirmed their policy commitments to keeping average temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial averages to avert further ecological crisis through limiting emissions. While the climate emergency forged a narrative of countries moving towards a common goal, national implementation strategies across the world vary quite significantly. In other words, energy transition pathways will have to be forged at the national level and, with this recognition, we are already clearly seeing potential winners and losers in the climate crisis. As electric vehicle sales accelerate and bigger wind turbines are built, mineral producers and countries with strategic advantages in clean energy technologies are likely to play a wider role in ensuring the resilience of global supply chains. Instead of perceiving the climate crisis as a Herculean task to avert civilisational decline, this project seeks to reframe it as an opportunity for creating an alternative energy system – one that is more sustainable, equitable and socially inclusive. The future path for the Global South has yet to be written. Therefore, political leaders must turn crisis into an opportunity to design new energy systems and alternative economic growth strategies beyond the carbon-intensive industrial model of the past century.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jewellord T. Nem Singh

Jewellord T. Nem Singh is Assistant Professor at the International Institute of Social Studies, part of Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Hague. He is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center, Washington DC, and an Affiliate Research Fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Leiden. He is the principal investigator of a five-year research programme entitled Green Industrial Policy in the Age of Rare Metals: A Trans-regional Comparison of Growth Strategies in Rare Earths Mining (GRIP-ARM), funded by the European Research Council (Starting Grant No. 950056). He is the author of over 45 publications, including Business of the State: Why State Ownership Matters for Resource Governance (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) and Developmental States Beyond East Asia (Routledge, 2020).

Notes

1 Cherif and Hasanov (Citation2019, 5–6).

2 The resurgence of industrial policy and government planning research has also been published in Competition and Change, while questions around upgrading in global value chains were periodically published in Review of International Political Economy. Apart from these key journals, business management studies have been the main outlet in studying globalization strategies linked to industrial upgrading.

3 Author interview with two Senior Officials, European Commission DG, Brussels/Online, 5 October 2021.

4 For example, current scholarship on energy transition pathways often missed Brazil as an exemplar of a country that transitioned towards clean energy as early as the 1970s, when the energy matrix became dependent on ethanol, hydropower, and hybrid vehicles.

5 Economic growth is defined here as increases in real incomes and gross domestic product, wherein the idea is that the economy will grow – and accompanying this is a steady growth in income – leading to better quality of life (Fiorini Citation2018, 5).

Bibliography

- Aiginger, K., and D. Rodrik. 2020. “Rebirth of Industrial Policy and an Agenda for the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20 (2):189–207. doi:10.1007/s10842-019-00322-3.

- Alami, I., M. Babic, A. D. Dixon, and I. T. Liu. 2022. “Special Issue Introduction: What is the New State Capitalism?” Contemporary Politics 28 (3):245–263. doi:10.1080/13569775.2021.2022336.

- Alami, I., A. D. Dixon, and E. Mawdsley. 2021. “State Capitalism and the New Global D/Development Regime.” Antipode 53 (5):1294–1318. doi:10.1111/anti.12725.

- Ang, Y. Y. 2016. How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Ang, Y. Y. 2018. “Domestic Flying Geese: Industrial Transfer and Delayed Policy Diffusion in China.” The China Quarterly 234:420–443. doi:10.1017/S0305741018000516.

- Ang, Y. Y. 2020. China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ban, C. 2013. “Brazil’s Liberal Neo-Developmentalism: New Paradigm or Edited Orthodoxy?” Review of International Political Economy 20 (2):298–331. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.660183.

- Best, J., C. Hay, G. LeBaron, and D. Mügge. 2021. “Seeing and Not-Seeing like a Political Economist: The Historicity of Contemporary Political Economy and Its Blind Spots.” New Political Economy 26 (2):217–228. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1841143.

- Bitabarova, A. G. 2018. “Unpacking Sino-Central Asian Engagement along the New Silk Road: A Case Study of Kazakhstan.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 7 (2):149–173. doi:10.1080/24761028.2018.1553226.

- Brenner, N., J. Peck, and N. Theodore. 2010. “Variegated Neoliberalization: Geographies, Modalities, Pathways.” Global Networks 10 (2):182–222. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00277.x.

- Bulfone, F. 2023. “Industrial Policy and Comparative Political Economy: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” Competition & Change 27 (1):22–43. doi:10.1177/10245294221076225.

- Cai, K. G. 2018. “The One Belt One Road and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Beijing’s New Strategy of Geoeconomics and Geopolitics.” Journal of Contemporary China 27 (114):831–847. doi:10.1080/10670564.2018.1488101.

- Camba, A., G. Lim, and K. Gallagher. 2022. “Leading Sector and Dual Economy: How Indonesia and Malaysia Mobilised Chinese Capital in Mineral Processing.” Third World Quarterly 43 (10):2375–2395. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2093180.

- Campbell, J. L. 2004. Institutional Change and Globalization. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Campbell, J. L., and O. K. Pedersen. 2001. The Rise of Neoliberalism and Institutional Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780691188225

- Campbell, J. L., and O. K. Pedersen. 2014. The National Origins of Policy Ideas: Knowledge Regimes in the United States. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Carmody, P., and J. Wainwright. 2022. “Contradiction and Restructuring in the Belt and Road Initiative: Reflections on China’s Pause in the “Go World.” Third World Quarterly 43 (12):2830–2851. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2110058.

- Chen, Z., and G. C. Chen. 2021. “The Changing Political Economy of Central State-Owned Oil Companies in China.” The Pacific Review 34 (3):379–404. doi:10.1080/09512748.2019.1679229.

- Chen, L., and B. Chulu. 2023. “Complementary Institutions of Industrial Policy: A Quasi-Market Role of Government Inspired by the Evolutionary China Model.” Third World Quarterly 44 (9):1981–1996. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2142551.

- Chen, H., and M. Rithmire. 2020. “The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy.” Studies in Comparative International Development 55 (3):257–277. doi:10.1007/s12116-020-09308-3.

- Cherif, R., and F. Hasanov. 2019. “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy’. WP/19/74.” IMF Working Paper. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Crouch, C. 2011. The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Doner, R. F., G. W. Noble, and J. Ravenhill. 2021. The Political Economy of Automotive Industrialization in East Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Doner, R. F., B. K. Ritchie, and D. Slater. 2005. “Systemic Vulnerability and the Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative Perspective.” International Organization 59 (2):327–361. doi:10.1017/S0020818305050113.

- Doner, R. F., and B. R. Schneider. 2016. “The Middle-Income Trap: More Politics than Economics.” World Politics 68 (4):608–644. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000095.

- Duarte, B. P. A., and L. C. Ferreira-Pereira. 2022. “The Soft Power of China and the European Union in the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative and Global Strategy.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30 (4):593–607. doi:10.1080/14782804.2021.1916740.

- Feng, Z. 2009. “Rethinking the “Tribute System”: Broadening the Conceptual Horizon of Historical East Asian Politics.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 2 (4):597–626. doi:10.1093/cjip/pop010.

- Fiorini, D. J. 2018. A Good Life on a Finite Earth: The Political Economy of Green Growth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Flores-Macías, G. A. 2012. After Neoliberalism? The Left and Economic Reforms in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gerschenkron, A. 1962. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Grugel, J., and P. Riggirozzi. 2012. “Post-Neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and Reclaiming the State after Crisis.” Development and Change 43 (1):1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x.

- Hauge, J. 2023. “Manufacturing-Led Development in the Digital Age: How Power Trumps Technology.” Third World Quarterly 44 (9):1960–1980. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.2009739.

- Hay, C. 2004. “The Normalizing Role of Rationalist Assumptions in the Institutional Embedding of Neoliberalism.” Economy and Society 33 (4):500–527. doi:10.1080/0308514042000285260.

- Hay, C. 2020. “Does Capitalism (Still) Come in Varieties?” Review of International Political Economy 27 (2):302–319. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1633382.

- Heberer, T. 2016. “The Chinese “Developmental State 3.0” and the Resilience of Authoritarianism.” Journal of Chinese Governance 1 (4):611–632. doi:10.1080/23812346.2016.1243905.

- Helleiner, E. 2021. “The Diversity of Economic Nationalism.” New Political Economy 26 (2):229–238. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1841137.

- Hirschman, A. 1945. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hoberg, G. 2021. The Resistance Dilemma: Place-Based Movements and the Climate Crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hobson, J. M. 2013a. “Part 1 – Revealing the Eurocentric Foundations of IPE: A Critical Historiography of the Discipline from the Classical to the Modern Era.” Review of International Political Economy 20 (5):1024–1054. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.704519.

- Hobson, J. M. 2013b. “Part 2 – Reconstructing the Non-Eurocentric Foundations of IPE: From Eurocentric “Open Economy Politics” to Inter-Civilizational Political Economy.” Review of International Political Economy 20 (5):1055–1081. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.733498.

- Hobson, J. M. 2020. Multicultural Origins of the Global Economy: Beyond the Western-Centric Frontier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108892704.

- Hsueh, R. 2011. China’s Regulatory State. 1st ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kang, D. C. 2010. East Asia before the West. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kim, K. 2018. “Matchmaking: Establishment of State-Owned Holding Companies in Indonesia.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 5 (2):313–330. doi:10.1002/app5.238.

- Kim, K. 2021. “Indonesia’s Restrained State Capitalism.” Development and Policy Challenges 51 (3):419–446. doi:10.1080/00472336.2019.1675084.

- Knio, K. 2019. “Diffusion of Variegated Neoliberalization Processes in Euro-Mediterranean Policies: A Strategic Relational Approach.” Globalizations 16 (6):934–947. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1560181.

- Krueger, A. 2002. Why Crony Capitalism is Bad for Economic Growth, edited by Stephen Haber, 1–23. Washington DC: Hoover Press.

- LeBaron, G., D. Mügge, J. Best, and C. Hay. 2021. “Blind Spots in IPE: Marginalized Perspectives and Neglected Trends in Contemporary Capitalism.” Review of International Political Economy 28 (2):283–294. doi:10.1080/09692290.2020.1830835.

- List, F. 1841. The National System of Political Economy. Translated by Sampson S. Lloyd. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Madariaga, A. 2020. “The Three Pillars of Neoliberalism: Chile’s Economic Policy Trajectory in Comparative Perspective.” Contemporary Politics 26 (3):308–329. doi:10.1080/13569775.2020.1735021.

- Milanovic, B. 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- Naseemullah, A. 2017. Development after Statism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Naseemullah, A. 2022. “The International Political Economy of the Middle-Income Trap.” The Journal of Development Studies 58 (10):2154–2171. doi:10.1080/00220388.2022.2096440.

- Nem Singh, J. 2014. “Towards Post-Neoliberal Resource Politics? The International Political Economy (IPE) of Oil and Copper in Brazil and Chile.” New Political Economy 19 (3):329–358. doi:10.1080/13563467.2013.779649.

- Nem Singh, J. 2021. “Mining Our Way out of the Climate Change Conundrum? The Power of a Social Justice Perspective.” Latin America’s Environmental Policies in Global Perspective. Washington, DC: The Wilson Center.

- Nem Singh, J. 2023. “The Advance of the State and the Renewal of Industrial Policy in the Age of Strategic Competition.” Third World Quarterly 44 (9):1919–1937. doi:10.1080/01436597.2023.2217766.

- Nem Singh, J., and G. C. Chen. 2018. “State-Owned Enterprises and the Political Economy of State–State Relations in the Developing World.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6):1077–1097. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1333888.

- Nem Singh, J. 2022. “The Renaissance of the Developmental State in the Age of Post-Neoliberalism.” In Handbook of Governance and Development, edited by Wil Hout and Jane Hutchison, 97–114. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nem Singh, J., and J. S. Ovadia. 2018. “The Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6):1033–1055. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1455143.

- Odijie, M. E. 2023. “Tension between State-Level Industrial Policy and Regional Integration in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 44 (9):1997–2014. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2107901.

- Ohno, K. 2013. “The East Asian Growth Regime and Political Development.” In Eastern and Western Ideas for African Growth: Diversity and Complementarity in Development Aid, edited by Kenichi Ohno and Izumi Ohno, 30–52. London: Routledge.

- Ovadia, J. S., and C. Wolf. 2018. “Studying the Developmental State: Theory and Method in Research on Industrial Policy and State-Led Development in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6):1056–1076. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1368382.

- Pickup, M. 2019. “The Political Economy of the New Left.” Latin American Perspectives 46 (1):23–45. doi:10.1177/0094582X18803878.

- Piletic, A. 2019. “Variegated Neoliberalization and Institutional Hierarchies: Scalar Recalibration and the Entrenchment of Neoliberalism in New York City and Johannesburg.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51 (6):1306–1325. doi:10.1177/0308518X19853276.

- Rodrik, D. 2006. “Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion? A Review of the World Bank’s Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform.” Journal of Economic Literature 44 (4):973–987. doi:10.1257/jel.44.4.973.

- Rodrik, D. 2008. “Normalizing Industrial Policy”. 3. Working Paper. Washington, DC: Commission on Growth and Development/World Bank.

- Rodrik, D. 2014. “Green Industrial Policy.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 30 (3):469–491. doi:10.1093/oxrep/gru025.

- Rodrik, D. 2016. “Premature Deindustrialization.” Journal of Economic Growth 21 (1):1–33. doi:10.1007/s10887-015-9122-3.

- Rodrik, D. 2002. “After Neoliberalism, What?” New Rules for Global Finance Coalition. https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/after-neoliberalism-what.pdf.

- Schlogl, L., and K. Kim. 2023. “After Authoritarian Technocracy: The Space for Industrial Policy-Making in Democratic Developing Countries.” Third World Quarterly 44 (9):1938–1959. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.1984876.

- Sinha, A. 2016. Globalizing India: How Global Rules and Markets are Shaping India’s Rise to Power. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press; pp. 354, ₹2509, ISBN 9781108447706.

- Storm, S. 2015. “Structural Change.” Development and Change 46 (4):666–699. doi:10.1111/dech.12169.

- Thurbon, E. 2016. Developmental Mindset. 1st ed. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/j.ctt18kr603.

- Thurbon, E., and L. Weiss. 2021. “Economic Statecraft at the Frontier: Korea’s Drive for Intelligent Robotics.” Review of International Political Economy 28 (1):103–127. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1655084.

- Tjia, L. Y-n. 2020. “The Unintended Consequences of the Politicization of the Belt and Road’s China-Europe Freight Train Initiative.” The China Journal 83:58–78. doi:10.1086/706743.

- Toby, C., and D. Jarvis (eds.). 2017. Asia after the Developmental State: Disembedding Autonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tsai, K. S., and B. Naughton. 2015. “Introduction.” In State Capitalism, Institutional Adaptation, and the Chinese Miracle: Comparative Perspectives in Business History, edited by Barry Naughton and Kellee S. Tsai, 1–24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139962858.001.

- Tsai, K. S. 2007. “Capitalism without Democracy: The Private Sector in Contemporary China.” 1st ed. Cornell University Press.

- Wade, R. H. 2003. “What Strategies Are Viable for Developing Countries Today? The World Trade Organization and the Shrinking of “Development Space.” Review of International Political Economy 10 (4):621–644. doi:10.1080/09692290310001601902.

- Wedeman, A. 2012. Double Paradox: Rapid Growth and Rising Corruption in China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Yeung, H. W-c. 2017. “State-Led Development Reconsidered: The Political Economy of State Transformation in East Asia since the 1990s.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10 (1):rsw031. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsw031.