Abstract

Based on new empirical insights gained in a multi-country project with a particular focus on Jordan as a hotspot of international development in the context of forced displacement, the paper in hand stages the relevance of the concept of financial health vis-à-vis financial inclusion to better support the financial lives of refugees. Financial inclusion of refugees – allowing them to store, borrow, and transfer money, insure against shocks, and pay bills through the formal financial infrastructure of host countries – has become a well-established practice in endeavours of economic integration in protracted displacement. Such access is expected to enable refugees to rebuild their livelihoods and become self-reliant. In other contexts, however, there is increasing acknowledgement that financial services are only a means to an end and not the end itself, resulting in a push for a shift in focus to a more holistic approach. Applying this understanding to the context of forced displacement, our research demonstrates that financial services are only one, and often not the most important, input to improve the self-reliance of refugees. In the absence of supportive conditions, such as access to jobs, identity and long-term certainty, financial inclusion investments can only improve refugees’ financial lives at the margins.

Introduction

The financial inclusion of refugees is increasingly promoted by humanitarian actors as a means to empower refugees, integrate them into local economies, and foster self-reliance. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) acknowledges that a lack of access to mainstream financial services poses a significant barrier to refugees’ economic independence and self-reliance (UNHCR, Citationn.d.). International organisations, including the Alliance for Financial Inclusion and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, have committed resources to promote financial inclusion for refugees (Alliance for Financial Inclusion Citation2020; El-Zoghbi et al. Citation2017; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Alliance for Financial Inclusion, and Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion Citation2017; International Labour Organization Citation2021; Martin Citation2019).

Our research, conducted as part of a multi-country qualitative research project to understand the financial lives of refugees, however, challenges this prevailing narrative. When we asked respondents in Jordan (the country we focus on for this paper) about whether they had a bank account or had thought about opening one, most often, the reaction was ironic laughter. They saw little value in having a bank account when there was no guarantee of income or a secure future in Jordan. Micro-credit, aimed at supporting refugee entrepreneurship, is also met with scepticism and fear due to the challenges faced by refugee-owned businesses. While digital payment channels were seen to offer some benefits for receiving cash assistance or remittances, their utility was limited.

These findings led us to question the emphasis on financial inclusion in the context of forced displacement, where refugees’ lack of economic rights emerges as a more pressing challenge. Our grounded theory approach revealed that access to formal financial services was not among refugees’ most significant hurdles. Instead, the absence of fundamental economic rights, such as freedom of movement, work opportunities, necessary documents, business ownership, and asset acquisition in the host country, proved to be crucial for their integration and self-reliance.

Based on empirical research in Jordan, this paper explores the financial lives of refugees experiencing protracted displacement and the strategies for financially including them, driven by humanitarian and development objectives such as efficient cash assistance delivery and promoting self-reliance.

Our analysis of financial inclusion efforts highlights two critical shortcomings in the approach of humanitarian actors. Firstly, relying solely on financial services fails to address the underlying causes of refugees’ financial challenges, while exaggerating claims that self-reliance emerges through financial inclusion. Secondly, de-risking measures by financial service providers hinder financial inclusion efforts, restricting refugees’ access to certain parts of the financial infrastructure, such as mobile money systems, which are not widely adopted or robust.

While Jordan has made progress in mobile money adoption and recognising micro-credit for refugee entrepreneurs, conventional financial inclusion outcomes, such as the number of accounts, transaction volume and loan repayment rates, do not align with refugees’ priorities. Meeting basic needs, overcoming financial shocks, making lump-sum investments, and planning for the future hold greater significance for them.

To address these outcomes within the context of protracted displacement, we propose the framework of ‘financial health’. This encompasses individuals’ daily systems that build financial resilience, ability to weather shocks and ability to pursue financial goals (Gutman et al. Citation2015; Parker et al. Citation2016). Financial health provides a broader perspective beyond financial inclusion, considering both the financial and non-financial factors necessary for refugees’ desired outcomes and improving financial inclusion.

Although financial inclusion may not always enhance financial health, a financially healthy refugee is more likely to engage with financial services. This framework allows stakeholders in financial inclusion, including humanitarian and development actors, to gain a deeper understanding of the factors influencing refugees’ need for and utilisation of financial services within their financial lives.

Our analysis of the Jordanian context has important implications for refugee financial inclusion efforts in self-reliance programmes across various geographical contexts. Although Jordan is considered a front-runner in financially including refugees and promoting self-reliance, the country still grapples with high poverty rates and uncertain futures for refugees due to the lack of foundational economic rights. As humanitarian actors continue to prioritise financial inclusion, critical reflection on the impact of these efforts is necessary. This paper fills that gap by offering an alternative conceptualisation through the financial health framework. Our conclusions align with similar research conducted in various global contexts, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tunisia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and the United States (Tufts University Citationn.d.).

To unpack these arguments, this paper analyses the broader paradigm of exclusion faced by refugees in Jordan, highlighting the limitations that hinder the effectiveness of financial inclusion strategies in promoting self-reliance. It examines the evolution of the refugee financial inclusion agenda, questioning its efficacy in the face of the exclusionary paradigm. Furthermore, the paper engages with the broader debate on depoliticised interventions in humanitarianism and their potential pitfalls within self-reliance programming. It introduces the financial health framework as an alternative, providing space to identify the non-financial inputs shaping refugees’ daily financial lives based on their own experiences. Finally, the paper presents key insights derived from empirical results when applying the financial health lens. While extending beyond the realm of financial services, these insights have significant implications for shaping financial inclusion efforts to genuinely improve refugees’ financial outcomes.

Research methodology and context

This paper presents research conducted as part of the Finance in Displacement (FIND) initiative, supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The study aimed to enhance understanding of refugees’ financial and livelihood transitions during extended displacement, focusing on Jordan and Kenya as case studies. The objective was to examine the role of financial services in facilitating these transitions using grounded theory methodology to develop conceptual theories from empirical data (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). Rather than solely investigating usage patterns of specific financial services, the research explored refugees’ financial lives within broader socio-economic and policy contexts.

The findings presented in this paper specifically focus on Jordan. Three rounds of in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted between September 2019 and December 2021 with participants residing in urban and semi-urban areas such as Amman, Irbid, Mafraq, Zarqa and Karak. The participants had experienced displacement for three to 10 years, and sample diversity was ensured by considering location, nationality, gender, age, time since arrival, and sources of income.

The initial sample consisted of 89 participants representing five countries of origin: Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Sudan and Somalia. Among them, 44 were Syrians, and the remaining 45 participants were from non-Syrian backgrounds. Gender distribution was evenly split, with the majority (70 out of 89) having resided in Jordan for three to eight years. Additionally, 72 participants fell within the working-age group of 18–45 years. Most households (72 out of 89) had at least one member engaged in irregular and seasonal income-generating activities, while 25 participants received monthly multi-purpose cash assistance from UNHCR.

During subsequent interview rounds, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, some participants discontinued their involvement, resulting in a final sample of 68 participants for the third round. Due to travel restrictions in 2020, a portion of second-round interviews were conducted virtually. Interview guidelines covered financial histories, livelihoods, and financial and risk management strategies. Informant interviews with humanitarian organisations, local non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and representatives from the refugee community provided additional insights into existing policies and programmes.

Data from the first and third interview rounds were transcribed and coded using qualitative data analysis software. Initial codes were descriptive, capturing meaningful units of information based on the interview guide’s structure. As analysis progressed, codes were revised and sub-codes added to capture emerging themes. These findings informed the development of interview guides for subsequent rounds. The second round focused on collecting both quantitative and qualitative data, with an emphasis on income and debt. The web-based platform Qualtrics was used for data organisation and analysis.

The broader paradigm of exclusion of refugees in Jordan

Jordan is an upper middle-income country with a population of 10.1 million, of whom close to 760,000 are refugees registered with the UNHCR, in addition to 2.3 million individuals of Palestinian descent registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNHCR Citation2022b; UNRWA Citation2022). The country has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention (updated in 2014) but has a Memorandum of Understanding with the UNHCR regarding the recognition and treatment of refugees (UNHCR and Government of Jordan Citation1998).

Jordan’s policies towards refugees have been influenced by the multiple influxes of refugees over the years, including Palestinians, Iraqis and Syrians, and smaller numbers from Yemen, Sudan and Somalia (De Bel-Air Citation2016; UNHCR Citation2022b). The international donor community has provided aid and shaped Jordan’s policies, such as through the Jordan Compact, which aimed to support the economy by offering aid and access to EU markets in exchange for opening the labour market for Syrian refugees (Government of Jordan Citation2016; Lenner Citation2020). However, these efforts have not achieved the desired economic growth or livelihood support for Syrian refugees (Lenner and Turner Citation2019). Access to work permits remains limited, and Syrian refugees often face barriers in the form of complex bureaucracy, costs and time involved in obtaining permits, as well as concerns about losing humanitarian assistance (Durable Solutions Platform Citation2020; Fallah, Istaiteyeh, and Mansur Citation2021). Consequently, most Syrian refugees work in the informal sector, facing exploitative conditions.

The exclusive focus on the Syrian crisis has created hierarchies among refugee populations based on nationality, with non-Syrian refugees facing difficulties in accessing work permits, opening businesses and receiving humanitarian assistance (Johnston, Baslan, and Kvittingen Citation2019; UNHCR Citation2022a). The labour market reforms introduced for Syrian refugees do not apply to non-Syrians, who are still regulated by restrictive laws for foreigners (Government of Jordan Citation1973). Non-Syrians face high annual work permit fees – around JOD 750 (US $994) per year in our research participants’ experience – and the risk of losing UNHCR protection if they apply (Human Rights Watch Citation2021; Waja Citation2021). As a result, many non-Syrian refugees work illegally and face the constant threat of arrest or deportation.

Moreover, durable solutionsFootnote1 such as voluntary repatriation or resettlement are often out of reach for most refugees in Jordan, as resettlement is possible for only a small proportion of the most vulnerable refugees, and home countries remain unsafe (UNHCR Citation2022c, Citation2022d).

Jordan’s approach towards financial inclusion of refugees

Given the protracted nature of the situation of refugees and declining aid, donors have been pushing for efforts to improve the self-reliance of refugees by integrating them into the Jordanian economy (Lenner and Turner Citation2019: 1). The UNHCR defines self-reliance as ‘the social and economic ability of an individual, household or community to meet essential needs in a sustainable manner and with dignity’ (UNHCR Citation2005). The self-reliance paradigm of humanitarianism envisions refugees as resilient individuals who can use entrepreneurialism to bounce back in the face of a crisis when provided with the right technical inputs (Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015). And one such input is access to formal financial services by way of promoting ‘financial inclusion’ (El-Zoghbi et al. Citation2017).

According to the World Bank, financial inclusion is achieved when ‘individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs – transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance – delivered in a responsible and sustainable way’ (World Bank Citationn.d.). Financial inclusion gained prominence as a global agenda after the 2008 financial crisis. Since then, it has been embraced in development policies and programmes, in part as a response to the criticism of its precursors ‘microfinance’ and ‘micro-credit’, which were condemned for resulting in over-indebtedness (Girard Citation2021). In the context of refugees, the topic of financial inclusion gained prominence from the 2010s, especially after the Syria crisis. Humanitarian actors theorised that once refugees have access to affordable, high-quality financial services that allow them to safely store money, build savings, send or receive money transfers, and carry out day-to-day financial transactions, they will be able to participate in the local economy and build livelihoods (Martin Citation2019).

Consequently, national governments, the UNHCR, and several international organisations have worked together to include refugees in the formal financial systems of host countries. In Jordan, the central bank proactively included refugees as a key segment in its National Financial Inclusion Strategy (Central Bank of Jordan Citation2017). However, the financial inclusion of refugees was limited to mobile wallets, which at the time of the study were not yet mainstream in the local economy. Moreover, only Syrian refugees could open mobile wallets with refugee cards issued by the Ministry of Interior, while non-Syrian refugees were required to provide valid passports which most did not have. Opening a bank account was still challenging due to complicated documentation requirements. However, given their informal jobs and limited incomes, few refugees felt the need for a bank account. Although two microfinance institutions were extending micro-credit to Syrian refugees while this research was being undertaken, their outreach was limited as most refugees were not able to provide a valid passport – required for a credit bureau check according to a key informant interviewed as part of the study.

The financial inclusion approach of Jordan has been heavily influenced by humanitarian actors and digital transfers of aid. Following the massive influx of Syrians, the Common Cash Facility was developed by UN agencies, international NGOs and government agencies to provide shared infrastructure to distribute cash assistance in a more efficient and coordinated way. Refugees who received aid through this system could withdraw the amount – only in full – from selected ATMs with iris-scanning capabilities. Only eight out of 2000 ATMs in the country had such capabilities (GSMA Citation2020; HelgiLibrary Citation2020). While this reduced the distribution costs for the NGOs, it did not support wider financial inclusion. The beneficiaries could not store money in the account, send and receive remittances, or borrow through this mechanism (Chehade, McConaghy, and Meier Citation2020; Gilert and Austin Citation2017).

Given these limitations, humanitarian actors in Jordan began envisioning mobile wallets as a way to offer an account to refugees who were barred from holding bank accounts, hence ‘financially including’ them. But mobile wallets were not yet widely used in the country and faced delivery challenges such as the limited outreach of the cash-out network and liquidity issues that limited withdrawals. The COVID-19 pandemic improved their usage, but much of this was driven by government payments for salaries and relief to vulnerable Jordanians (AlSalhi et al. Citation2020; JoPACC Citation2021a). As more humanitarian cash transfers shift to the mobile payment channels, account ownership and transactions will increase, leading to an improvement in financial inclusion according to the standard metrics used to measure success. However, most of these transactions are likely to be limited to aid disbursements and withdrawals that do not signify real financial inclusion (Bold, Porteous, and Rotman Citation2012; JoPACC Citation2021a, Citation2021b). These standard metrics fail to indicate whether or not this shift improves refugees’ progress towards self-reliance by meeting essential needs in a sustainable manner and with dignity.

Could financial inclusion improve refugee self-reliance?

Financial inclusion efforts have been widely adopted within refugee self-reliance programmes. However, it is important to acknowledge that financial inclusion alone cannot guarantee refugee self-reliance. This section critically examines the limitations of the financial inclusion approach and its alignment with the critiques of self-reliance and resilience promotion in humanitarianism.

Scholars have criticised the self-reliance paradigm for its market-led approach, often characterised as ‘inclusive’, ‘neoliberal’ and ‘financialised’ refugee support. The conceptualisation and practice of self-reliance are heavily influenced by the priorities of international donors, who seek cost-effective exit strategies for long-term refugee populations (Easton-Calabria and Omata Citation2018). This departure from classic humanitarian principles, which prioritised refugees’ needs and were critical of politics and the market, has resulted in new forms of resilience humanitarianism (Hilhorst Citation2018; Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015). These approaches shift the focus onto national and local authorities as responsible service providers, emphasise the role of alternative actors such as the private sector and new humanitarians, and portray aid recipients as ‘active and resilient survivors and first responders’. Consequently, these depoliticised approaches often fail to address structural issues and instead promote superficial innovations that overlook the root causes of refugees’ suffering. While they may avoid political conflicts and create new markets for the private sector, they do not lead to transformative changes in refugees’ conditions and can inadvertently undermine autonomous humanitarianism.

Financial inclusion interventions, such as digital cash transfers and technology-backed microfinance for refugees, are frequently touted as innovative solutions to enhance refugee self-reliance but face the same issue. These solutions, despite their good intentions, neglect the underlying political and structural challenges that impede refugees’ economic agency. Scholars argue that such interventions are driven by motives of surveillance and profiteering rather than genuine efforts to promote refugee self-reliance (Bhagat and Roderick Citation2020; Tazzioli Citation2019). For example, the implementation of digitalised protection measures in Jordan, involving biometric data and mobile money systems, raises concerns about potential surveillance and control over refugees’ freedom of movement (Paragi and Altamimi Citation2022).

Microcredit programmes also face criticism for exacerbating the over-indebtedness of an already vulnerable population, as refugees resort to credit out of necessity due to limited income opportunities (Arab Renaissance for Democracy & Development Citation2021; Bhagat and Roderick Citation2020; Dhawan, Wilson, and Zademach Citation2022). Additionally, these efforts are seen as exclusionary since they only cater to refugees who possess entrepreneurial skills and can access a range of financial services, thereby further marginalising those who do not meet these criteria (Bhagat and Roderick Citation2020; Scott-Smith Citation2016).

Further, the push for mobile wallets in Jordan has led to hiving off refugee transactions into closed and second-rate financial systems that are separate from the mainstream financial infrastructure – a situation far from financial inclusion. As humanitarian payments are shifted to this system, there is a risk of exclusion for individuals who do not meet the necessary requirements, such as non-Syrian refugees lacking proper identification documents (for more details refer to Dhawan, Wilson, and Zademach Citation2022; Dhawan and Zollmann Citation2023).

Even outside the humanitarian context, emerging evidence indicates mixed results regarding the impact of financial inclusion on low- and middle-income populations. Mere access to basic bank accounts or payment channels does not necessarily reduce poverty or income inequality (Banerjee, Karlan, and Zinman Citation2015; Duvendack and Mader Citation2019). Microfinance, with its focus on microcredit, and the increasing utilisation of digital credit have been criticised for contributing to the indebtedness and vulnerability of low-income populations (Chamboko and Guvuriro Citation2021; Hulme and Arun Citation2011). Scholars have also raised concerns about digital financial inclusion enabling the commodification of financial behavioural data for the purpose of control and governance (Aitken Citation2017; Gabor and Brooks Citation2017).

The critique of the effectiveness of financial inclusion aligns with observations of previous depoliticised approaches that have proven ineffective in addressing the needs of refugees. The Jordan Compact, discussed above in the section ‘The broader paradigm of exclusion of refugees in Jordan’, serves as an example of such an approach, aiming to turn the Syrian crisis into a development opportunity. The donor-driven push to formalise Jordanian labour markets resulted in hasty solutions that left behind Syrians who did not fit preconceived frameworks and excluded non-Syrian refugees (Lenner and Turner Citation2019).

Another prevalent example is vocational training provided to enhance refugees’ skills in contexts where they face barriers in pursuing economic opportunities. In Kenya, which is also a focus of this research project, the government follows an encampment policy that restricts refugees’ movement outside the camp (Gitonga et al. Citation2021). A study conducted in the Kakuma refugee camp in rural Kenya revealed that although vocational training aimed to equip refugees with technical skills, they had limited avenues to apply these skills due to their inability to access commercial markets beyond the camp (Easton-Calabria and Omata Citation2018). Such interventions, implemented with the goal of fostering refugee self-reliance, prove ineffective as they overlook the fundamental issue constraining refugees’ economic agency and instead offer temporary remedies. Moreover, they divert attention from addressing structural barriers and allocate resources away from routine activities that could have a more significant impact on refugees’ well-being (Scott-Smith Citation2016). Recognising and addressing these limitations is crucial for developing comprehensive and effective approaches to promote refugee self-reliance.

Financial health: a holistic framework to understand refugees’ financial needs

Given the limitations of financial inclusion, this paper proposes a shift towards a more comprehensive approach that moves beyond process indicators (savings accounts opened, loans obtained) to outcome indicators (debt reduced, goals met). We peer through the lens of financial health to analyse our empirical data, providing novel insights for financial inclusion initiatives. Financial health provides a less depoliticised conceptualisation, allowing us to identify structural constraints and enablers that shape refugees’ daily lives. This section explores the concept of financial health and its application within the context of refugees facing protracted displacement.

‘Financial health’, more widely referred to as ‘financial well-being’, has been a topic of interest to scholars in several disciplines including economics, financial planning and counselling, consumer behaviour and psychology. While research on financial well-being dates back to the late 1980s, it has gained prominence in recent years, especially following the global financial crisis (Kreutz et al. Citation2021; Sang Citation2022). Previous studies have primarily focused on understanding the determinants of financial well-being and measuring it within developed economies, examining both general consumers and specific vulnerable groups such as college students, retirees and women.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of financial well-being, most scholars emphasise three key aspects: meeting current needs, financial resilience against shocks, and long-term planning (Kempson, Finney, and Poppe Citation2017). The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in the United States has played a significant role in defining financial well-being, shifting its focus from financial education to financial well-being as a key outcome for defining and measuring success. The CFPB defines financial well-being as ‘a state of being wherein a person can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices that allow enjoyment of life’ (CFPB Citation2015, 18; see also CFPB Citation2017). This definition has been applied in studies conducted in the United Kingdom (Hayes, Evans, and Finney Citation2016), Australia and New Zealand (Comerton-Forde et al. Citation2018; Prendergast et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b), and Norway (Kempson, Finney, and Poppe Citation2017). Most of the research on financial well-being has been done in the context of developed countries, ie high-income countries in the Global North, except for the 2018 Gallup survey which was conducted in 10 countries, including a few middle- and low-income countries (Gallup Citation2018).

The term ‘financial health’, as used in this paper, was popularised by the Centre for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI), now known as the Financial Health Network, a non-profit financial inclusion consultancy. Building on a study conducted on consumer financial health in the United States, the CFSI defines financial health as the state achieved when an individual’s daily systems help build the financial resilience to weather shocks and the ability to pursue financial goals (Gutman et al. Citation2015).

In 2017, the CFSI collaborated with the Centre for Financial Inclusion to conduct a study testing and contextualising the concept of financial health within developing economies (Ladha et al. Citation2017). Based on this study, they formulated a set of indicators to be used in developing economies. These indicators comprise the ability to balance income and expenses, build and maintain reserves, manage existing debts and access potential resources, plan and prioritise, manage and recover from financial shocks, and use an effective range of financial tools. Additionally, four contextual factors were identified: absolute income level, income and expense volatility, social networks, and financial roles.

The concept of financial health as a holistic approach has gained traction within a growing community, highlighting that mere access to financial services does not automatically result in improved financial stability and resilience (El-Zoghbi Citation2019; FSD Kenya Citation2019; Gallup Citation2018; Rhyne Citation2020; Singh et al. Citation2021; UNSGSA Citation2021). Recent work has also adapted the financial health framework to various consumer segments, including micro-, small, and medium-sized enterprises (Noggle, Foelster, and Johnson Citation2020).

For this study, we adapted the financial health definition and indicators provided by Ladha et al. (Citation2017) to suit the context of refugees living in protracted displacement. We define refugees as financially healthy when they can achieve the following outcomes over a period of four to five years, starting from their arrival in the host country (Jacobsen and Wilson Citation2020; Wilson and Zademach Citation2021):

Meet basic needs: Refugees meet essentials like food, shelter, clothing, medicine, and education by accessing resources themselves or through personal, social and professional networks.

Comfortably manage debt: Refugees often arrive indebted and may take on additional credit during displacement. While some debt is manageable, excessive debt exposes individuals to violence, extortion and mental health challenges.

Recover from financial setbacks: Prolonged displacement brings job loss, medical emergencies and asset depletion. Access to resources like lump sum aid, personal savings or credit from networks helps refugees overcome these setbacks.

Access a lump sum to enable investment in assets and opportunities: Most refugees have limited assets and savings, relying on meagre funds for daily expenses. Without the ability to accumulate or borrow a lump sum, refugees face obstacles in building wealth, investing in education and better housing, or acquiring high-value assets like a car, hindering long-term security.

Continually expand their planning horizons: Over time, newcomers should transition from daily struggles to expanding economic activities, attaining stability, and envisioning a future beyond the present financial circumstances.

The above indicators focus on the desired financial outcomes for refugees and encompass a range of inputs, extending beyond financial services. While Ladha et al. (Citation2017) initially included the use of financial services as an indicator, this study places emphasis on the outcomes themselves.

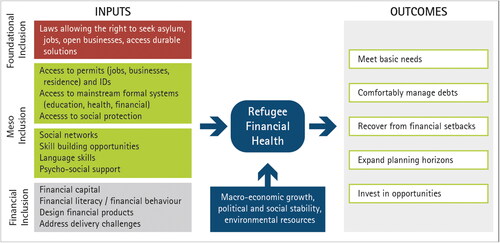

provides a summary of the financial health framework, which identifies the inputs necessary to attain the desired outcomes for refugees as outlined in the previous section. These inputs extend beyond financial services and encompass non-financial factors that directly influence refugees’ ability to achieve their financial health goals. The framework categorises these inputs into three levels: (1) At the base of the framework are the inputs required to ensure foundational inclusion for refugees. This includes establishing laws that grant refugees the right to seek asylum, leverage economic opportunities and access durable solutions. Foundational inclusion is crucial for creating an enabling environment that supports refugees’ financial well-being and stability. (2) The meso level of inputs encompasses the infrastructure necessary to enable access as granted by the established laws. Do refugees have access to the documents required to obtain work permits or business licences? Do they have access to training to build vocational skills or language? Are they able to build social and information networks? (3) Financial inclusion policies and programmes can then build upon foundational and meso-level inputs to facilitate refugees’ pursuit of self-reliance. These policies and programmes aim to provide refugees with access to vital financial services that support their financial health objectives. However, it is important to recognise that without the presence of the foundational and meso-level inputs, financial inclusion efforts will not be able to achieve their intended impact. The framework also acknowledges the influence of overarching conditions, including macro-economic growth, social and political stability, and environmental resources. These factors have a significant impact on the opportunities available to the population, including refugees.

Figure 1. Financial health: an alternative approach to identify financial and non-financial inputs that affect refugees’ financial outcomes.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Empirical results: financial health perspective in the displacement context

Applying the financial health perspective to refugees’ circumstances revealed valuable insights into their financial inclusion. By considering factors such as legal status, social networks, livelihoods, current financial and non-financial strategies, and future plans, we gained a comprehensive understanding of the barriers to self-reliance beyond financial services. In the following subsections, we present these insights in the context of Jordan.

Empirical evidence supports the argument to look beyond financial services to improve refugees’ financial health. A more meaningful objective, from their perspective, requires a broader range of inputs (see ). Financial services alone are often not the most crucial factor and cannot produce results in isolation. Nonfinancial inputs are equally necessary.

Most refugees face an income problem rather than a finance problem

After their arrival in Jordan, financial services helped our research participants access humanitarian aid and reliable international remittances for essential needs like food, shelter and medicine. Banks, mobile payment providers and money transfer companies played significant roles. As some refugees ventured into small businesses, they utilised informal loans or savings groups to accumulate capital for low-level trading. Among our participants, only a small fraction (eight out of 44) who found formal jobs temporarily required a bank account for salary transactions and provided the necessary documentation.

Microfinance loans, bank accounts, payment services or insurance could have been of use if refugees’ livelihoods gradually improved and their income from work diversified. However, most participants faced stagnant or unstable incomes, with small businesses struggling to grow. Challenges arose due to the informal nature of jobs or the precarious legal status of businesses. In such contexts of low and unpredictable incomes, refugees perceived little need for financial services. As livelihoods failed to progress, the demand for financial services flatlined.

Previous research confirms that low absolute income and income unpredictability contribute to poor financial health (Brune, Karlan, and Rouse Citation2020; CFPB 2017). In Jordan, refugees face high poverty levels, with around 86% living below the poverty line, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Brown et al. Citation2019; World Bank and UNHCR Citation2020). A lack of foundational rights limits their ability to work and travel, access documentation, and increases uncertainty about their future.

While financial services can aid refugees in building small savings, repaying loans, or raising capital for investments, they cannot substitute for the foundational rights necessary for robust livelihoods. Refugees must have guaranteed access to these rights before they can fully benefit from financial services.

Extensive use of informal credit does not imply a potential market for formal credit

The majority of research participants in Jordan relied on informal credit from friends, family and neighbours to meet basic needs and overcome financial shocks. Local shops offered credit for purchasing food, household supplies and medicine, particularly during the pandemic.

Viewing this high use of informal credit solely through the lens of financial services might suggest a market for formal micro-credit (eg UNHCR Citation2021b). However, our findings indicate that formal credit is more likely to hinder refugees’ financial health, given their unpredictable and insufficient income levels. While credit provided relief and the ability to secure basic needs, it also led to mounting psychological pressure as debts accumulated. Nearly one-third of the participants had outstanding debts of more than US $700, and one in five owed more than US $1400. With debts amounting to two to five months of household income, most participants struggled to repay alongside daily expenses. Women-headed households and non-Syrian participants experienced additional difficulties due to lower incomes, limited work opportunities, safety concerns and childcare responsibilities. Participants commonly used annual or biannual winterisation cash assistance provided by UNHCR to relieve some of their debt burden (UNHCR Citation2021a).Footnote2 However, without access to this lump sum, the refugees’ debt cycle continued.

Reliance on borrowing for daily expenses prevents refugees from securing basic needs and negatively impacts their overall financial health (Gubbins Citation2020; Kempson, Finney, and Poppe Citation2017). The extensive use of credit indicates weak livelihoods, insufficient social protection and limited positive coping mechanisms such as savings or insurance.

Access to adequate finance is highlighted as a challenge for refugee-owned businesses in Jordan (Asad et al. Citation2019; Microfinanza Citation2018). However, the lack of rigorous empirical evidence evaluating the impact of microfinance programmes has raised scepticism about their effectiveness (Mcloughlin Citation2016; Sylvester Citation2011). Relying solely on this approach may exclude most refugees and prioritise only entrepreneurial individuals (Easton-Calabria and Omata Citation2016). Many entrepreneurs in our study were hesitant to start a business with a loan due to uncertainty, competition and low profitability. Defaulting on formal loans runs the risk of imprisonment and hinders the possibility of leaving the country (Arab Renaissance for Democracy & Development Citation2021; Rana Citation2020). As a result, those who took loans preferred informal networks. While microfinance addresses some issues, the larger problem of limited opportunities and an uncertain future in Jordan persists.

Uncertainty about the future limits refugees’ ability to invest and use financial services

Being able to contemplate a future beyond the present day is an important indicator of improving financial health (Gubbins Citation2020; Ladha et al. Citation2017; Netemeyer et al. Citation2018). Refugees in Jordan face limitations in investing and using financial services due to the uncertainty surrounding their future. The struggle to meet immediate needs prevents them from considering their financial future beyond the present day. While improving financial literacy and changing refugee financial behaviour can help address this issue, the fundamental problem lies in their uncertain legal status and the lack of durable solutions. Refugees lack the option to return home, integrate into the host economy, or resettle in a third country, leaving them in a state of limbo without security for the future.

The temporary guest status of refugees in Jordan results in limited economic rights and opportunities. They are unable to fully own assets or businesses and have no viable pathway to permanent residency or citizenship. Consequently, refugees have little incentive to invest in assets or businesses without guarantees for the future.

Non-Syrian refugees face even greater uncertainty, as they are not granted access to the labour market, vocational training or social integration. Expensive work permits and clearance processes pose additional barriers, leading to fear of detention or deportation. With limited chances of integration and a reliance on resettlement, non-Syrian refugees struggle to survive with minimal aid and unstable income from illegal work and support networks (Jones Citation2021). Without a clear timeline for resettlement or the ability to participate in the local labour market, they cannot invest in skills or assets.

The financial inclusion approach builds on the theory that regular use of financial services would help refugees to create financial histories which could then be used by service providers to offer further financial services and thus assumes that refugees have a clear idea of their future (Chehade, McConaghy, and Meier Citation2020). But we saw this was not the case for the majority. Here, the logic that promotes financial inclusion as a tool for long-term self-reliance conflicts with policies that treat refugees as temporary populations and offering only short-term relief.

Refugees’ informal social networks do the heavy lifting of finance

If we set our sights on improving refugees’ financial health, then we find that resources outside the traditional financial sector provide most of the financial heavy lifting. These include informal social networks of refugees and community-based support mechanisms that fill the welfare gaps left by the public, private and humanitarian sectors. These networks provide informal financing to meet basic needs, overcome financial shocks, and raise capital for investment in businesses or skill building. They also provide critical non-financial support such as guidance on the way of life in Jordan, finding housing, accessing information about aid, finding better-paying jobs, and expanding social networks.

The support from these networks is rooted in solidarity. Unlike modern-day humanitarianism which is characterised by hierarchy and bureaucracy, it assists in a horizontal and anti-bureaucratic way (Chouliaraki Citation2013; Komter Citation2004). We found that such solidarity was common among refugees who shared close cultural ties based on nationality or ethnicity. We heard examples of Yemeni and Somali participants raising funds with the help of other refugees from their country for medical treatment that they needed immediately after arrival. A Syrian woman was able to crowdsource a sum of US $200 for a medical emergency from 40 participants of a faith-based group she attended. Another Somali woman shared how the sheikh at the neighbourhood mosque raised money from the community to help her pay off a debt. Some of the churches in the capital city provided regular financial support to refugees irrespective of their nationality, religion or gender. Sudanese and Somali refugees – a small community with much less humanitarian support – showed exceptional solidarity in hosting new arrivals in their homes, supporting them to find housing and jobs, providing rent and food support when someone lost a job, and helping them to navigate the complex humanitarian systems.

Such support networks expanded quickly using online groups on WhatsApp and Facebook, as well as offline groups formed during faith-based activities and training sessions facilitated by NGOs. However, certain groups remained isolated due to their socio-economic situation (eg women-headed households and Iraqi refugees from minority religions) or language constraints (eg Somali refugees). This meant that they had weaker social networks and limited coping strategies.

Another form of solidarity finance was provided by landlords and neighbourhood grocery stores, whose incomes depended on refugees. Landlords often allowed refugees to delay rent payments until they received income from work or humanitarian aid. Several participants regularly accessed what we call ‘shop credit’ (Dhawan, Wilson, and Zademach Citation2022). Here, small shops owned by Jordanians selling groceries, household supplies and medicines offered a line of credit to refugees and other low-income Jordanians and migrants living in low-income neighbourhoods. Shop owners allowed migrants to buy essential goods on credit and pay later when they received income or aid. For the shops, this was not just social service but part of business as usual: without such a credit line they would not be able to secure steady sales. Nonetheless, they played a pivotal role in ensuring refugees’ food security by offering unbureaucratic, flexible and timely financial support. During the pandemic, however, many of their customers were unable to service their debts, and shop owners became cautious about letting more people buy on credit. Further research to understand how these critical players in the refugee ecosystem are coping with the economic shock of COVID-19 could help identify ways to support them and, in turn, also support their refugee customers.

While understanding and strengthening these local mechanisms is valuable, it is crucial to emphasise that they should not be considered a substitute for humanitarian aid and a guarantee of economic rights. Although refugees often rely on fellow refugees or members of the host community who share similar circumstances, it is important to recognise the limitations of such networks. For instance, corner store owners, who provide credit lines to refugees, operate on narrow profit margins and assume substantial risks. Additionally, individuals who are impoverished or socially isolated due to socio-cultural or psychological circumstances may not be able to effectively leverage these networks for support.

Conclusion

This paper provides a critical examination of the financial inclusion approach in improving refugee self-reliance in Jordan. The findings reveal that far from being included in mainstream financial infrastructure, refugee transactions are hived off into a separate financial system of mobile wallets, which is as yet far from robust. The efforts to expand access to formal micro-credit narrowly focus on entrepreneurial refugees, and risk leaving them vulnerable to debt if businesses fail due to the absence of foundational rights. Remittances and payment accounts primarily function as channels for receiving humanitarian assistance, falling short of achieving self-reliance objectives.

Moreover, it is argued that even if refugees benefitted from full financial inclusion, lasting positive outcomes would not be guaranteed. Financial inclusion alone lacks transformative inputs and fails to address the fundamental lack of economic rights that hinders refugees’ pursuit of self-reliance. To broaden perspectives and improve the financial well-being of refugees, this paper advocates for the adoption of a comprehensive financial health framework. This framework provides a roadmap for designing effective financial inclusion initiatives that go beyond mere access to financial services and address the broader structural and contextual factors that shape refugees’ financial well-being. Achieving financial health requires collaboration among multiple stakeholders and necessitates political solutions to address systemic barriers and create an enabling environment for refugees’ financial well-being.

Regarding the limitations of this paper and potential avenues for future research, it should be acknowledged that the operationalisation of the financial health definition within the specific context of Jordan requires empirical testing to establish quantified thresholds (for example, to determine an optimal lump sum for investments or identify a ‘comfortably’ manageable debt level). Further research on this could be complemented by existing surveys by host governments, international organisations and humanitarian agencies (Brown et al. Citation2019; Leeson et al. Citation2020). Analysis of financial inclusion survey data, such as the global and national Findex, from a financial health perspective can also provide valuable insights (Gubbins Citation2020). Thus, currently, our approach remains primarily conceptual rather than operational.

Finally, we emphasise that the relationship between financial inclusion and financial health is not a dichotomy but rather involves the integration of both, with financial health serving as a framework to prioritise the needs and desired outcomes of refugees. The adoption of the financial health approach offers novel insights into financial inclusion and the unique challenges it faces in displacement contexts. This framework aids in identifying the fundamental inputs necessary for financial inclusion initiatives to genuinely enhance refugee self-reliance, aligning with their ultimate objectives.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Jens Hogreve as well as two anonymous reviewers and the editor of the journal on earlier versions of the paper. Furthermore, we express our gratitude to the whole team of researchers involved in the FIND project, including our local partners in Jordan who supported the data collection, and above all our refugee interview partners. Without their openness to our project and willingness to generously share their experiences, this article would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Swati Mehta Dhawan

Swati Mehta Dhawan has been a research associate and successful doctoral candidate at the Department of Geography at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt. She has been leading the research in Jordan under the Finance in Displacement (FIND) project.

Kim Wilson

Kim Wilson is Senior Lecturer and Senior Research Fellow at the Fletcher School, Tufts University, and has served as one of the two co-principal investigators of the FIND project (together with Hans-Martin Zademach). She is the lead author of a series of studies on the financial journey of refugees and migrants.

Hans-Martin Zademach

Hans-Martin Zademach is Professor of Economic Geography at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt and has served as a co-principal investigator of the FIND project (together with Kim Wilson). His research addresses questions of sustainable (regional) development and related politics and policies, with a particular focus on the issues of finance and financialisation; it has been published in a range of international journals.

Notes

1 According to UNHCR, durable solutions include local integration in the host country, resettlement to a third country, or voluntary return to country of origin (UNHCR Citation2022d).

2 In 2020, a household of six persons who received regular monthly cash assistance also received an additional winter assistance of US $340, and those who did not receive monthly assistance received winter assistance of US $400.

References

- Aitken, R. 2017. “‘All Data Is Credit Data’: Constituting the Unbanked.” Competition & Change 21 (4): 274–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529417712830

- Alliance for Financial Inclusion. 2020. “Integrating Forcibly Displaced Persons (FDPs) into National Financial Inclusion Strategies (NFIS).” Guidance Note No. 41. https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020-12/AFI_GN41_AW_digital.pdf

- AlSalhi, D., E. Halaiqah, J. Najjar, L. Hashem, and M. Ghannam. 2020. “Lockdown but Not Shutdown: The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Financial Services in Jordan.” JoPACC. www.jopacc.com/ebv4.0/root_storage/en/eb_list_page/covid-19_report_english.pdf

- Arab Renaissance for Democracy & Development. 2021. “Women’s Informal Employment in Jordan: Challenges Facing Home-Based Businesses During COVID-19.” Women’s Advocacy Issues – Volume 3 [Policy Brief]. https://jordan.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2021/womens-informal-employment-in-jordan

- Asad, Y., S. P. Ucak, J. Holt, and C. Olson. 2019. “Another Side to the Story Jordan: A Market Assessment of Refugee, Migrant, and Jordanian-Owned Businesses.” Building Markets. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/70422.pdf

- Banerjee, A., D. Karlan, and J. Zinman. 2015. “Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140287

- Bhagat, A., and L. Roderick. 2020. “Banking on Refugees: Racialized Expropriation in the Fintech Era.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (8): 1498–1515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20904070

- Bold, C., D. Porteous, and S. Rotman. 2012. “Social Cash Transfers and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Four Countries.” Focus Note No. 77. CGAP. https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Focus-Note-Social-Cash-Transfers-and-Financial-Inclusion-Evidence-from-Four-Countries-Feb-2012.pdf

- Brown, H., N. Giordano, C. Maughan, and A. Wadeson. 2019. “Vulnerability Assessment Framework: Population Study 2019.” UNHCR. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/68856.pdf

- Brune, L., D. Karlan, and R. Rouse. 2020. “Measuring Financial Health around the Globe.” Innovations for Poverty Action. https://www.poverty-action.org/sites/default/files/publications/IPA%20Financial%20Health%20-%20Full%20Report%20Final.pdf

- Central Bank of Jordan. 2017. “The National Financial Inclusion Strategy 2018-2020.” Central Bank of Jordan. www.cbj.gov.jo/EchoBusv3.0/SystemAssets/PDFs/2018/The%20National%20Financial%20Inclusion%20Strategy%20A9.pdf

- CFPB. 2015. “Financial Well-Being: The Goal of Financial Education.” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/financial-well-being/

- CFPB. 2017. “Financial Well-Being in America.” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201709_cfpb_financial-well-being-in-America.pdf

- Chamboko, R., and S. Guvuriro. 2021. “The Role of Betting on Digital Credit Repayment, Coping Mechanisms and Welfare Outcomes: Evidence from Kenya.” International Journal of Financial Studies 9 (1): 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs9010010

- Chehade, N., P. McConaghy, and C. M. Meier. 2020. “Humanitarian Cash Transfers and Financial Inclusion – Lessons from Jordan and Lebanon.” Working Paper. CGAP. www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020_03_Working_Paper_Cash_Transfers.pdf

- Chouliaraki, L. 2013. The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Comerton-Forde, C., E. C. Ip, D. Ribar, J. Ross, N. Salamanca, and S. Tsiaplias. 2018. “Using Survey and Banking Data to Measure Financial Wellbeing.” Scales Technical Report No. 1. Melbourne Institute Applied Economic & Social Research. https://fbe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2839433/CBA_MI_Tech_Report_No_1_Chapters_1_to_6.pdf

- De Bel-Air, F. 2016. Migration Profile: Jordan [Policy Brief]. Florence, Italy: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSC). https://doi.org/10.2870/367941

- Dhawan, S. M., K. Wilson, and H.-M. Zademach. 2022. “Formal Micro-Credit for Refugees: New Evidence and Thoughts on an Elusive Path to Self-Reliance.” Sustainability 14 (17): 10469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710469

- Dhawan, S. M., and J. Zollmann. 2023. “Financial Inclusion or Encampment? Rethinking Digital Finance for Refugees.” Journal of Humanitarian Affairs 4 (3): 31–41. https://doi.org/10.7227/JHA.094

- Durable Solutions Platform. 2020. “In My Own Hands: A Medium-Term Approach towards Self-Reliance and Resilience of Syrian Refugees and Host Communities in Jordan.” Durable Solutions Platform and Program on Forced Migration and Health, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. https://globalcenters.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/DSP-CU%20report.pdf

- Duvendack, M., and P. Mader. 2019. “Impact of Financial Inclusion in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 15 (1-2): e1012. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2019.2

- Easton-Calabria, E., and N. Omata. 2016. “Micro-Finance in Refugee Contexts: Current Scholarship and Research Gaps,” 116. https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/micro-finance-in-refugee-contexts-current-scholarship-and-research-gaps

- Easton-Calabria, E., and N. Omata. 2018. “Panacea for the Refugee Crisis? Rethinking the Promotion of ‘Self-Reliance’ for Refugees.” Third World Quarterly 39 (8): 1458–1474. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1458301

- El-Zoghbi, M. 2019. “Toward a New Impact Narrative for Financial Inclusion.” CGAP. https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/toward-new-impact-narrative-financial-inclusion

- El-Zoghbi, M., N. Chehade, P. McConaghy, and M. Soursourian. 2017. “The Role of Financial Services in Humanitarian Crises (Access to Finance Forum No. 12).” CGAP. https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/role-financial-services-humanitarian-crises

- Fallah, B., R. Istaiteyeh, and Y. Mansur. 2021. “Moving beyond Humanitarian Assistance: Supporting Jordan as a Refugee-Hosting Country,” 59. World Refugee & Migration Council. https://wrmcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Jordan-Syrian-Refugees-WRMC.pdf

- FSD Kenya. 2019. “Inclusive Finance? Headline Findings from FinAccess 2019.” FSD Kenya. http://www.fsdkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Inclusive_Finance_headline-findings-from_FinAccess.pdf

- Gabor, D., and S. Brooks. 2017. “The Digital Revolution in Financial Inclusion: International Development in the Fintech Era.” New Political Economy 22 (4): 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1259298

- Gallup. 2018. “Gallup Global Financial Health Study: Key Findings and Results.” Gallup Inc. https://news.gallup.com/reports/233399/gallup-global-financial-health-study-2018.aspx

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Alliance for Financial Inclusion, & Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion. 2017. “Documentation – GPFI/AFI High-Level Forum on Financial Inclusion of Forcibly Displaced Persons – G20 Germany 2017.” www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/Documentation_GPFI%20AFI%20High%20Level%20Forum_FINAL_Cover%281%29.pdf

- Gilert, H., and L. Austin. 2017. “Review of the Common Cash Facility Approach in Jordan.” UNHCR and CaLP. www.calpnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/ccf-jordan-web-1.pdf

- Girard, T. 2021. “Explaining the Origins and Evolution of the Global Financial Inclusion Agenda.” The University of Western Ontario. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7921

- Gitonga, S., R. Mwihaki, J. Zollmann, and K. Wilson. 2021. “Refuge? Refugees’ Stories of Rebuilding Their Lives in Kenya.” Epsilon. https://sites.tufts.edu/journeysproject/rebuilding_lives_in_kenya/

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

- Government of Jordan. 1973. Jordan: Law No. 24 of 1973 on Residence and Foreigners’ Affairs. www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4ed4c.html

- Government of Jordan. 2016. “The Jordan Compact: A New Holistic Approach between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the International Community to Deal with the Syrian Refugee Crisis.” https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/jordan-compact-new-holistic-approach-between-hashemite-kingdom-jordan-and

- GSMA. 2020. “Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance in Jordan: A Gateway to Mobile Financial Services.” GSMA. www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Jordan_Mobile_Money_CVA_Case_Study_Web_Spreads.pdf

- Gubbins, P. 2020. “The Prevalence and Drivers of Financial Resilience among Adults: Evidence from the Global Findex.” FSD Kenya. https://fsdkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Report_Global-Financial-Resilience-Paper_Kenya.pdf

- Gutman, A., J. Hogarth, T. Garon, and R. Schneider. 2015. “Understanding and Improving Consumer Financial Health in America.” The Center for Financial Services Innovation. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cfsi-innovation-files/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/24183123/Understanding-and-Improving-Consumer-Financial-Health-in-America.pdf

- Hayes, D., J. Evans, and A. Finney. 2016. “Momentum UK Household Financial Wellness Index.” Personal Finance Research Centre University of Bristol. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/pfrc/Momentum%20Index%20PFRC%20March%202016%20FINAL%20Report%20-%20after%20minor%20revisions%20(15_08_2016)%20%20.pdf

- HelgiLibrary. 2020. “Number of ATMs in Jordan.” www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/number-of-atms/jordan

- Hilhorst, D. 2018. “Classical Humanitarianism and Resilience Humanitarianism: Making Sense of Two Brands of Humanitarian Action.” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 3 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-018-0043-6

- Hulme, D., and T. Arun. 2011. “What’s Wrong and Right with Microfinance.” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (48): 23–26.

- Human Rights Watch. 2021, March 30. “Jordan: Yemeni Asylum Seekers Deported.” Human Rights Watch. www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/30/jordan-yemeni-asylum-seekers-deported

- Ilcan, S., and K. Rygiel. 2015. ““Resiliency Humanitarianism”: Responsibilizing Refugees through Humanitarian Emergency Governance in the Camp.” International Political Sociology 9 (4): 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12101

- International Labour Organization. 2021, June 18. “Financial Inclusion for Refugees and Host Communities [Document].” http://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/social-finance/WCMS_804230/lang–en/index.htm

- Jacobsen, K., and K. Wilson. 2020. “Supporting the Financial Health of Refugees: The Finance in Displacement (FIND) Study in Uganda and Mexico.” Tufts University. https://sites.tufts.edu/journeysproject/supporting-the-financial-health-of-refugees-the-finance-in-displacement-find-study-in-uganda-and-mexico/

- Johnston, R., D. Baslan, and A. Kvittingen. 2019. “Realizing the Rights of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan from Countries Other than Syria.” Norwegian Refugee Council. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/71975.pdf

- Jones, E. 2021, March 25. “The Pandemic Is No Excuse to Shut the Door on Refugee Resettlement.” The Citizen. https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/oped/-the-pandemic-is-no-excuse-to-shut-the-door-on-refugee-resettlement-3335656

- JoPACC. 2021a. “A Market Study on the Adoption of Digital Financial Services.” JoPACC. www.jopacc.com/ebv4.0/root_storage/en/eb_list_page/adoption_of_digital_financial_services_final_report_en_published.pdf

- JoPACC. 2021b. “JoMoPay Report – December 2021.” www.jopacc.com/ebv4.0/root_storage/en/eb_list_page/jomopay_transactions_-_december_2021-0.pdf

- Kempson, E., A. Finney, and C. Poppe. 2017. Financial Well-Being a Conceptual Model and Preliminary Analysis. SIFO Project Note no. 3-2017; p. 74. Oslo, Norway: Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences.

- Komter, A. E. 2004. Social Solidarity and the Gift. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511614064

- Kreutz, R. R., W. V. da Silva, K. M. Vieira, and V. R. Dutra. 2021. “State of the Art: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Financial Well-Being.” Revista Universo Contábil 16 (2): 87. https://doi.org/10.4270/ruc.2020212

- Ladha, T., K. Asrow, S. Parker, E. Rhyne, and S. Kelly. 2017. “Beyond Financial Inclusion: Financial Health as a Global Framework.” Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI) and Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion (CFI). https://content.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/FinHealthGlobal-FINAL.2017.04.11.pdf

- Leeson, K., P. Bhandari, A. Myers, and D. Buscher. 2020. “Measuring the Self-Reliance of Refugees.” Journal of Refugee Studies 33 (1): 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez076

- Lenner, K. 2020. ““Biting Our Tongues”: Policy Legacies and Memories in the Making of the Syrian Refugee Response in Jordan.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 39 (3): 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdaa005

- Lenner, K., and L. Turner. 2019. “Making Refugees Work? The Politics of Integrating Syrian Refugees into the Labor Market in Jordan.” Middle East Critique 28 (1): 65–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2018.1462601

- Martin, C. 2019. Roadmap to the Sustainable and Responsible Financial Inclusion of Forcibly Displaced Persons. Eschborn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Mcloughlin, C. 2016. “Sustainable Livelihoods for Refugees in Protracted Crises.” K4D Helpdesk Report. Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13108

- Microfinanza. 2018. “Assessing the Needs of Refugees for Financial and Non-Financial Services – Jordan.” UNHCR, SIDA, and Grameen Credit Agricole Foundation. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/66387

- Netemeyer, R. G., D. Warmath, D. Fernandes, and J. G. Lynch, Jr. 2018. “How Am I Doing? Perceived Financial Well-Being, Its Potential Antecedents, and Its Relation to Overall Well-Being.” Journal of Consumer Research 45 (1): 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109

- Noggle, E., J. Foelster, and T. Johnson. 2020. “A Framework for Understanding the Financial Health of MSME Entrepreneurs.” Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion. https://content.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/08/MSME-Framework-08122020.pdf

- Paragi, B., and A. Altamimi. 2022. “Caring Control or Controlling Care? Double Bind Facilitated by Biometrics between UNHCR and Syrian Refugees in Jordan.” Society and Economy 44 (2): 206–231. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2021.00027

- Parker, S., N. Castillo, T. Garon, and R. Levy. 2016. “Eight Ways to Measure Financial Health,” 18. The Center for Financial Services Innovation. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cfsi-innovation-files-2018/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/09212818/Consumer-FinHealth-Metrics-FINAL_May.pdf

- Prendergast, S., D. Blackmore, E. Kempson, and R. Russell. 2021a. “Financial Wellbeing: A Survey of Adults in Australia.” ANZ. https://www.anz.com.au/content/dam/anzcomau/documents/pdf/aboutus/wcmmigration/financial-wellbeing-aus18.pdf

- Prendergast, S., D. Blackmore, E. Kempson, and R. Russell. 2021b. “Financial Wellbeing: A Survey of Adults in New Zealand.” ANZ. https://www.anz.com.au/content/dam/anzcomau/documents/pdf/aboutus/esg/financial-wellbeing/anz-nz-adult-financial-wellbeing-survey-2021.pdf

- Rana, S. F. 2020, April 9. “A $423 Helping Hand That Could Land a Mother of 7 in Handcuffs.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/world/middleeast/microloans-jordan-debt-poverty.html

- Rhyne, E. 2020. “Measuring Financial Health: What Policymakers Need to Know.” Cenfri. https://cenfri.org/wp-content/uploads/Measuring-Financial-Health.pdf

- Sang, N. M. 2022. “Visualization and Bibliometric Analysis on the Research of Financial Well-Being.” International Journal of Advanced and Applied Science 9 (3): 10–18. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2022.03.002

- Scott-Smith, T. 2016. “Humanitarian Neophilia: The ‘Innovation Turn’ and Its Implications.” Third World Quarterly 37 (12): 2229–2251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1176856

- Singh, J., A. Dermish, A. Duijnhouwer, and A. Misquith. 2021. “Delivering Financial Health Globally: A Collection of Insights, Approaches and Recommendations [White Paper].” UNCDF-Centre for Financial Health & MetLife Foundation. https://www.uncdf.org/article/7008/delivering-financial-health-globally-a-collection-of-insights-approaches-and-recommendations

- Staton, B. 2019, January 19. “Sudanese Refugees Forcibly Deported from Jordan Fear Arrest and Torture.” The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/19/sudanese-refugees-forcibly-deported-from-jordan-fear-arrest-and-torture

- Stave, S. E., T. A. Kebede, and M. Kattaa. 2021. “Impact of Work Permits on Decent Work for Syrians in Jordan.” International Labour Organization. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Impacts%20of%20Work%20Permit%20Regulations%20on%20Decent%20Work%20for%20Syrian%20refugees%20in%20Jordan.pdf

- Sylvester, A. J. 2011. Beyond Making Ends Meet: Urban Refugees and Microfinance [Master’s Project, Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University]. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/3575/MP_2011_Sylvester.pdf?se

- Tazzioli, M. 2019. “Refugees’ Debit Cards, Subjectivities, and Data Circuits: Financial-Humanitarianism in the Greek Migration Laboratory.” International Political Sociology 13 (4): 392–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olz014

- Tufts University. n.d. “Essays & Articles Archives – The Journeys Project.” Fletcher Journeys Project. https://sites.tufts.edu/journeysproject/category/publications/essays-articles/

- UNHCR. n.d. “Financial Inclusion.” UNHCR Livelihoods and Economic Inclusion. https://www.unhcr.org/financial-inclusion.html

- UNHCR. 2005. Handbook for Self-Reliance. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR Division of Operational Support; Reintegration and Local Settlement Section. www.refworld.org/docid/4a54bbf40.html

- UNHCR. 2021a. “Jordan: Winter 2020 Cash Assistance Post Monitoring Distribution Report.” UNHCR. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/87764

- UNHCR. 2021b. “Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance 2020 Post Distribution Monitoring Report.” UNHCR. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNHCR%20Jordan%20Post%20Distribution%20Monitoring%20Report%20%282020%29%20.pdf

- UNHCR. 2022a. “Jordan: Cash-Based Intervention Dashboard (December 2021).” UNHCR. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/90513

- UNHCR. 2022b. “Jordan Operational Update: March 2022.” UNHCR. http://reporting.unhcr.org/document/2214

- UNHCR. 2022c. “Jordan: Resettlement Dashboard.” UNHCR. http://reporting.unhcr.org/document/1707

- UNHCR. 2022d, March. “Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response: Durable Solutions.” UNHCR Operational Data Portal: Refugee Situations. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria_durable_solutions

- UNHCR, and Government of Jordan. 1998. “Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of Jordan and UNHCR.” UNHCR. http://mawgeng.a.m.f.unblog.fr/files/2009/02/moujordan.doc

- UNRWA. 2022. “United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the near East: Jordan.” UNRWA. https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/jordan

- UNSGSA. 2021. “Annual Report to the Secretary General: Financial Inclusion – Toward a More Resilient Future.” The United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Advocate for Insclusive Finance for Development. https://www.unsgsa.org/sites/default/files/resources-files/2021-09/UNSGSA-Annual-Report-2021.pdf

- Waja, L. 2021, June 20. “Ban on Work Permits, Refugee Status Duality for non-Syrian Refugees ‘Will See Changes in July’.” Jordan News. www.jordannews.jo/Section-109/News/Ban-on-work-permits-refugee-status-duality-for-non-Syrian-refugees-will-see-changes-in-July-4409

- Wilson, K., and H.-M. Zademach. 2021. “Finance in Displacement: Joint Lessons Report.” Tufts University, International Rescue Committee, Catholic University Eichstaett-Ingolstadt. https://www.ku.de/fileadmin/150304/Forschung/FIND/FINDFinalReport_v3_GreenRed.pdf

- World Bank. n.d. “Financial Inclusion Overview [Text/HTML].” World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview

- World Bank, and UNHCR. 2020. “Compounding Misfortunes: Changes in Poverty since the Onset of COVID-19 on Syrian Refugees and Host Communities in Jordan, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Lebanon.” World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34951