Abstract

During the Colombian Civil War, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people were targeted by armed actors for reasons related to ideology and strategy. Even with the generalised violence in Colombia during this time, there was significant public interest in this specific form of violence, as evidenced by its tabloid coverage. The nation’s main tabloid – El Espacio – covered this violence against LGBTQ people in graphic detail. Twenty years of coverage (1985–2005) includes a range of gory graphics and horrific headlines that show the pain of a persecuted community in a highly violent context. In this article, I focus on this media coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence, notable for its brutality and prejudice, to argue that its spectacle built on a stigma that reinforced the cleavage of its victims from the body politic through a legitimation of the violence. In doing so, the coverage of this violence became a weapon of war that depoliticised the subordination of an entire population in a society beset by an internal armed conflict.

1. Introduction

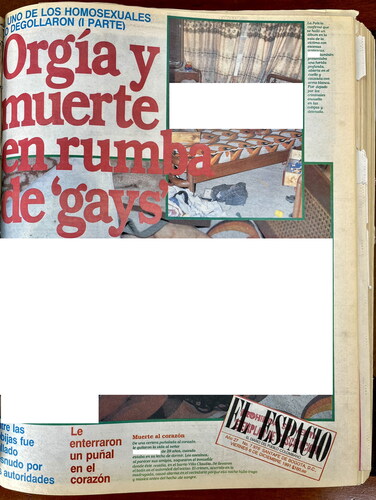

‘Orgy and death at a party of “gays”’, reads a headline in scarlet letters. The accompanying image is a brutalised dead body covered in blood. A secondary headline contextualises this violence; it reads ‘One of the homosexuals had their throat slashed’.Footnote1 This material appears in a 1991 issue of the Colombian daily newspaper El Espacio. El Espacio pioneered the tabloid format in Colombia – media with more of a focus on gossip, glamour and intrigue than the traditional daily analysis found in broadsheet formats – and established itself as a purveyor of scandalous news with a particular penchant for displaying mutilated corpses alongside nude women (Rincón Citation2013). During much of its nearly 50-year run, the tabloid covered violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQFootnote2) populations, particularly trans women, and other persons with transfeminine identities, in graphic detail. A review of its coverage reveals a range of gore and horrific headlines that show the pain of a persecuted community in a highly violent context.

What did the media spectacle of this anti-LGBTQ violence – the graphic photography and written coverage – mean in the context of the Colombian civil war? Or, to modify Fujii’s dictum of violent display (2021), what did this brutality on display do that less novel or remarkable forms of violence did not? This article explores this question through El Espacio’s coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence, which I consider a form of ‘violent display’, defined by Fujii as ‘a collective effort to stage violence for people to see, notice, and take in’ (2). Fujii explored how these ‘displays can do things’ that undisplayed violence cannot (5) – particularly how they produce new identities for the participants (or witnesses), make participation in violence a requirement for in-group inclusion, and establish new political orders.

In this paper, I focus on the media coverage of brutal acts of anti-LGBTQ violence to extend the transformative potential of violent display to LGBTQ victims of brutal display in Colombia. I conduct visual analysis to argue that this coverage represents a mechanism for the consolidation of a social order that subjugated queer and trans lives in the context of war. These spectacles of brutality reinforced a stigma that depoliticised the violence perpetrated, cleaving its victims from the broader body politic of Colombia. To deliver this argument, I first present my methods of visual analysis within the broader context of anti-LGBTQ violence during the Colombian Civil War. From there, I connect this method of visual international relations (‘visual IR’) with the literature on the microdynamics of gendered violence during civil war by considering the meaning and ethics of photographic representations of violence. I then contextualise this media coverage and develop the analytical frames of my visual analysis. From there, I analyse this coverage in order to demonstrate how this brutal display served as a mechanism through which prejudice and violence reinforced the subordination of queer and trans people.

The power of these images in El Espacio results from how their content inspires horror in a manner that legitimises the violent victimisation of these populations. This legitimation can be based on prejudice – ‘these groups deserved it’ – or it can be based on defensiveness – ‘these groups are a threat’. The content of these photographs, the graphic destruction of these bodies, and the stigmatising narratives that contextualise the images reinforced the difference of these populations and depoliticised this violence. In this sense, the coverage could be considered a photographic documentation of mass atrocity, identified by Humphrey (Citation2013, 132) as ‘the culmination of a process of de-subjectification, denationalization, and de-humanisation which defines power over life by determining who falls inside and outside the social limits’. In analysing this phenomenon, the paper makes two contributions. First, in the literature on microdynamics of war, it builds on gender in conflict debates to detail how violent spectacle produces a subjectivity tied to subordination. Second, in the literature on visual IR, it shows how photography itself can become a weapon of war.

2. Visual analyses and anti-LGBTQ violence during the Colombian Civil War

The ‘aesthetic turn’ in international relations has centred the importance of the ‘visual’ in understanding global security politics (Hozić Citation2017). Hansen’s (Citation2011) framework for analysing securitisation processes in images includes reviewing the image’s content and analysing it in dialogue with its text and the wider policy discourse, before finally considering the broader debates about the meaning of this image. Building off this approach, Cooper-Cunningham (Citation2024) develops a ‘tripartite’ framework that considers images in dialogue with both text and bodies in order to recognise how these three epistemic sites make images ‘polysemous’, containing multiple potential meanings. I build on these two approaches to conduct my visual analysis of security. In this context of wartime dynamics, I follow the guidance of Loken (Citation2021), to consider how images can be a source of data in political violence research, disclosing beliefs and broader cultural narratives of a given topic and bringing debates of cultural production to a local encounter of communities in war.

In combining the methods of visual IR with studies of the microdynamics of war, I build on scholarship that foregrounds the cultural space as a matter of contentious politics (Lerner Citation2021; Taylor Citation1997; Wedeen Citation2015) and photography as a unique source of data for understanding war (Loney and Pohlman Citation2022; Windfeld, Hvithamar, and Hansen Citation2023). I situate the concept of spectacle in this visual analysis within Debord’s (Citation2014, 11) contention that spectacles reflect ‘a social relation between people that is mediated by images’. Thinking from the perspective of both the El Espacio newspaper as well as the broader public, I consider: What did spectacles of anti-LGBTQ violence sell in Colombia? Colombian scholars have identified anti-LGBTQ violence during the country’s civil war as a form of social control through gendered violence and subordination during conflict. In this framing, armed actors capitalise on existing prejudicial structures of gender and sexuality to commit gendered acts of violence in order to control local populations and establish legitimacy (Colombia Diversa Citation2020; Comisión de la Verdad Citation2022). In this argument, acts of blatant homophobic violence as well as targeted sexual violence campaigns become ‘corrective’ measures against the transgression of social norms that then create hierarchies of gendered subordination and establish moral orders (CNMH Citation2015, Citation2019). Serrano-Amaya (Citation2018) finds that paramilitary violence against LGBTQ populations reshaped social relations and produced new forms of governance. According to Serrano-Amaya (Citation2018, 27), anti-LGBTQ violence became a strategy of war ‘to control populations in conflict zones through collective threats and the fabrication of an enemy within the community’. Beyond the surveillance and targeting of these populations, Serrano-Amaya identifies how acts of collective targeting reshape community relations to diminish the opportunity for organising. His findings reinforce the work of the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (‘National Center for Historic Memory’, CNMH Citation2015), which tied anti-LGBTQ violence to the establishment of a social order aligned with a new morality. Armed actors imposed these ‘moral orders’ to legitimise their presence and justify collective violence against civilians (CNMH Citation2015).

Anti-LGBTQ violence, then, not only results from stigma but can produce it as well. Gómez (Citation2013) conceptualises this dual potential of anti-LGBTQ violence in her concept of prejudice-based violence, which she identifies as both hierarchical and exclusionary. Gómez argues that these acts both reject difference and reinforce it. An act of violence based on homo/transphobia identifies the LGBTQ person as an ‘other’ and subjects them to a subordinate status as ‘lesser’. Violence is further constitutive in constructing an ‘us’ and ‘them’. Given the insecurity of war, civilians might take comfort in their inclusion in the ‘us’ or the homogenised group ‘protected’ by an armed actor. In this sense, during war, violence committed against LGBTQ people operates at both an expressive and an instrumental level. Its target could be as important as its witness.

This continuum of anti-LGBTQ violence between peace and war parallels the literature on the microdynamics of violence against women before, during, and after war (Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Citation2020; Boesten Citation2014; Cockburn Citation2004; Moser and Clark Citation2001). In this literature, scholars have looked at how women become targeted by armed actors for reasons related to strategy and ideology, particularly through conflict-related sexual violence (Cohen Citation2016; Wood Citation2018). This impact of gender-based violence extends well beyond the temporal conditions of the act itself and can have legitimising effects related to social control or transformation (Arjona Citation2016; Stallone and Zulver Citation2024; Stewart Citation2021). Analysing anti-LGBTQ violence in the Colombian context helps to reveal new mechanisms that rely on social and political meanings: a focus on the brutality of this violence, its dehumanising potential, and the cultural associations all identify new logics of wartime violence. I connect these visual analysis methods to the literature on spectacles of violence to recognise how images of violence produce, reinforce, and reveal stigmatising narratives operationalised by the logics of war.

3. Ethics and meanings in photographic representations of violence

The ethics of this project are complicated and I write not from a place of certitude, but instead, of openness. Investigating the meaning of an unethical phenomenon – sensationalist media coverage of brutal anti-LGBTQ violence – requires rigorous considerations of the ethical risks in order to not perpetuate existing harm or propagate new forms of harm in the research process. While many university ethics protocols require consideration of how a scholar engages with living human subjects, there has been little consideration of how to deal with deceased (particularly murdered) human subjects of research as well as their images (Minwalla, Foster, and McGrail Citation2022; Smith Citation2020; Shepherd Citation2017; Subotić Citation2021).Footnote3 Such considerations are particularly important for this paper as I conduct a visual analysis of media coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence and present a censored version of this coverage.Footnote4 This censored version obscures any images of corpses depicted but maintains the images of these headlines and the structure of the coverage in order to ground my visual analysis in contextual detail.Footnote5

A photograph may appear to represent an empirical reality, but it is a moment articulated through the lens of the image-taker. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag (Citation2003) explores this manipulative potential of war photography. She notes that images might appear more ‘real’ than other forms of written media because they can be directly viewed and interpreted by the viewer, but their perceived veracity is fiction. They ultimately are the construction of the image-taker, who applies them to their own narrative. As such, photographs are not always a representational truth; their meaning comes from a combination of deceit, context, and personal perspective. This possibility of manipulation haunts their analytical potential. Campbell (Citation2003, Citation2004) notes that this analytical potential is without a clear morality: photographs and their meanings can become sites of prejudice that reproduce violence, but they can also become sites of resistance. In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Hartman (Citation2019) analyses photographic portraiture to revive stories lost to archives and histories that marginalise and minoritise populations. In her examination of how Black women and girls at the turn of the twentieth century rearticulated norms of sexuality and gender to launch a ‘revolution in a minor key’, Hartman reveals the ethical stakes of not contesting photography’s problematic potential.

Sontag (Citation2003, 65) writes, ‘Photographs objectify: they turn an event or a person into something that can be possessed’. This possession, or association through familiarity, represents an inter-relational process between the image and the viewer. The image, particularly that of suffering, compels (perhaps excites) the viewer. If it did not, these images from El Espacio would not sell. But what does it do after its initial attraction? Sontag argues that images of suffering only produce compassion when the viewer can identify with the subject. She warns that they also produce a feeling of powerlessness. In the face of this powerlessness and without that capacity to identify, the image can harden a viewer, creating distance between the viewer and its subject. These photographs of anti-LGBTQ violence in El Espacio with their sensationalist commentary, thus, are not meant to draw compassion. Instead, they alienate and characterise a community already stigmatised by prejudice. Campbell (Citation2004) has identified the power of photographic representations of violence to connect with and amplify existing narratives. He notes that the media has a role in dictating norms or ‘taste and decency’ (2004, 55). It is in this role of norm-making that media has the potential to politicise or depoliticise a phenomenon, recognising it as exceptional or denying its uniqueness.

There is a subtle difference, however, between photography focused on the suffering of war and photography focused on transgressive violence. Photographs of suffering produce horror – the journalistic images of victims of Nazi concentration camps or bombings in Viet Nam are painfully indelible in many public imaginaries. But the meaning produced by these photographs differs from that produced by photographs of the lynching of Black Americans in the American South, which often became postcards (Wood Citation2011). The context of these photographs produced meanings associated with the celebration of white supremacy and further stigmatised the broader Black community by presenting this violence and associated imagery as commodities to be consumed in the form of a postcard, to the horror of the Black American community (Fujii Citation2021; Ore Citation2019). The difference in the meanings associated with these photographs relates to the relationship between violence and subjectivity; in other words, how the act of violence and corresponding narratives produce an understanding of the phenomenon and its victims (Das Citation2008). In her analysis of horror, Cavarero (Citation2009) identifies the chilling effects of witnessing violence because of how corporeal desecration offends the ontological dignity of a person. Mistreatment of the human body in the public space captures broad attention because of its brutality, meaning ‘a violent action that transgresses established socio-cultural norms for a given context’ (Ritholtz Citation2022a, 3). In this sense, photographs of brutal display such as the lynching of Black Americans not only celebrated this prejudice-based violence but also extended its impact to multiple audiences. The pictorial celebration of this transgression of socio-cultural norms – or attempted violent subjugation of an entire class of people – facilitates the spectacle.

It is because of the vital role of images in this stigmatising process that I believe it is important to detail the context of this coverage. In her analysis of the ethics of archival material related to atrocity, Subotić (Citation2021, 346) notes ‘[the archive is] of human significance because it details the process of dehumanisation and deconstruction of social norms that happens in the worst possible human environment imaginable’. In an article that focuses on the meaning and impact of these images, I assert that this media coverage provides important documentation of the norms that contributed to the depoliticisation of this population’s violent victimisation. I follow Subotić’s (Citation2021, 347) direction that ‘We need to embed these archival materials within the historical and political context of the time…. An archival document alone is not only meaningless, it can be highly deceptive and its interpretation ethically challenging’ (2020, 6).

In line with this analysis, this article provides the context of these images in order to demonstrate the mechanisms through which media coverage and photographic representation of brutal anti-LGBTQ violence reinforces the gendered subordination of this population in a wartime context.

I recognise the risks of my approach. Crane (Citation2008) has argued that reproducing photographs of atrocities, particularly those taken by the perpetrator, is a form of participation in the atrocity because it reproduces the perpetrator’s perspective. Similar critiques have been launched by scholars of lynching and the Holocaust who argue that the reproduction of these images of atrocity in the public domain facilitates a form of renewed violence (Reinhardt Citation2012). Additionally, transgender studies scholars have been critical of this focus on lethal anti-trans violence as opposed to ameliorating the conditions of the living. Snorton and Haritaworn (Citation2013, 74) write, ‘[T]he circulation of trans people of color in their afterlife accrues value to a newly professionalizing and institutionalizing class of experts whose lives could not be further removed from those they are professing to help’. Given these critiques, I worry about my own involvement in these patterns. I am no stranger to having, in the words of Krystalli (Citation2021, 127), ‘dilemmas and doubts…[as] my constant research companions’. As a result, I centre the ethical dimensions of these images in my task to produce new knowledge on the lives of these affected populations in an attempt to recognise an important element of their wartime history.

Further, I am persuaded by the argument of Feierstein (Citation2014, 83), who argues that ‘a social practice [such as genocide] must first be thoroughly understood before it can be successfully confronted and eradicated. First, it must be demystified and its multiple, complex, and nuanced causal relations laid bare’. As such, this analytical effort to tie brutal display to broader debates on the role of visuals in the microdynamics of war requires revisiting these machinations of horror. These photographs are terrible to view, but in recognition of Hoover Green’s (Citation2018) critique that scholars of violence have a way of sanitising and decontextualising violence that risks a removed analysis from affected lives, centring these images as the unit of analysis allows me to avoid perpetuating this dynamic in my exploration of brutal display during war.

I conclude by recognising a potential ethical redemption in challenging the final resting narratives of these victims. Both Campbell (Citation2003, Citation2004) and Cooper-Cunningham (Citation2019) acknowledge how photographic representation of violence can be rearticulated to challenge the silences and narratives associated with the targeted group’s violent victimisation. Though I cannot redress the ethical indignity of their treatment, I attempt to avoid an extension of this indignity by confronting the problematic narratives that framed this coverage. I take inspiration from the work (and courage) of Hartman (Citation2008, Citation2019), who has meticulously challenged the ‘violence of the archive’ as it relates to Black women’s and girls’ histories of violence, resistance and joy in the United States. In discussing these photographs with activists and scholars in Colombia as well as a broader community of scholars of violence around the world, I attempt to practise an ‘ethic of care’ (Krystalli and Schulz Citation2022) in how I present this media coverage and produce my analysis. This extended ethics section, which is tied to a broader analysis of meaning in photographic representations of violence, presents the urgency in developing this ethic of care.

4. The spectacle of brutalised LGBTQ bodies in Colombia

4.1. Reading El Espacio as spectacle

This article reviews coverage by El Espacio on LGBTQ victimisation from 1985 to 2005, an important period in the second cycle of war in Colombia when violence peaked in the country (Suárez Citation2022; Uribe Citation2004). I gained access to an archive of 78 articles from the Gender Unit of the CNMH.Footnote6 As the CNMH archive began in 1985, I begin the analysis then. I ended the coverage in 2005 for two reasons: First, the end of formal paramilitarism with the passage of the Ley de Justicia y Paz in 2005 meant that the dynamic between the press and certain armed actors was to transform; and, second, by the mid-2000s media coverage of LGBTQ populations changed as a result of the growing LGBTQ rights movement in the country, as evidenced by the 2004 founding of the country’s biggest LGBTQ rights organisation, Colombia Diversa. In what follows, I explore how this media coverage facilitated a social marginalisation of LGBTQ people through their violent victimisation. In detailing the grand narratives and pictorial representation of these narratives, I identify a socially contextual process in which violence legitimised a stigmatising moral framework that centres the reason for this victimisation on the LGBTQ population’s own identity and behaviour, thus justifying their targeting.

Brutality is central to this coverage and recognised explicitly. ‘Brutal murder of homosexual’Footnote7 reads one headline in red, with two additional lines of context: ‘in an orgy in his room’ and ‘was barbarically tortured killing him’. In this coverage, entire spreads would be devoted to the death of an LGBTQ person, nearly all gay men, trans women, and transfeminine individuals.Footnote8 The scene of the crime would be described in lurid detail, and often a mutilated corpse would be shown in graphic photographs. The image of these brutalised bodies would be matched with technocratic, forensic reporting of ‘4 shots in the head’Footnote9 or ‘42 stab wounds’.Footnote10 Sometimes the papers included a photograph of the victim before their death, and nearly always this photograph showed nearly no resemblance to the bloody images on the page. Whether the presence of these ‘before’ photographs provided some sort of dignity or reprieve to the gruesome representations on the page is a matter of interpretation.

The centrality of brutality in anti-LGBTQ violence is further evidenced in the paper’s own interpretations of the phenomenon. One news story shares in red ‘A Homosexual Cut into Pieces’,Footnote11 with more details in blue: ‘The authorities try to identify him by an arm’. In the story, the author writes that ‘the hand is too delicate to be a man’s, too big to be a woman’s’. The hand size provides one hint (based in prejudice not science) that it belongs to a homosexual, but to the author, the ‘smoking gun’ is the fact that only a hand was found. This subtext reveals this association between LGBTQ people and dismemberment: only undeserving lives were treated such a way.

Beyond the remarkable portrayals of brutalities, two narratives dominate El Espacio’s coverage: eroticism and securitisation. In the first, most prevalent in the 1980s and early 1990s, these events were described as ‘passion crimes’ or ‘the crimes of lovers’. The word ‘orgy’ was frequently used. Tales of romance, jealousy and revenge framed the graphic murders of love gone wrong. Starting in the 1990s and continuing until the 2000s, these events began to be framed in the context of insecurity. The violence was still framed as intracommunal, or between LGBTQ people, but here it was often in the context of criminal activities. The victims were framed as thieves caught up in a violent illicit economy. Less prominent narratives during this time included suicides related to HIV/AIDS diagnoses and disappearances.

When founded in 1965, El Espacio launched the ‘yellow journalism’ industry in Colombia, where the focus was on sensationalism, social drama and salacious imagery. The tabloid closed in 2013, but its legacy persists in Colombia’s media landscape today (Rincón Citation2013). I focus in this article on the work of El Espacio because it was not until after the end of formal paramilitarism in the early 2000s that traditional broadsheet media organisations reported on violence against LGBTQ people. Prior coverage predominantly occurred in tabloids, which covered anti-LGBTQ violence as well as violence against the broader population. Gómez-Dueñas (Citation2012) analysed media coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence (or hate crimes as she calls them) from the 1980s and 1990s in El Caleño, a Cali-based tabloid. In her analysis, Gómez-Dueñas (Citation2012, 199) argues that these hate crimes reveal links between violence, sexuality and social order through the violent enforcement of social norms associated with an ‘obligatory heterosexuality’. This paper extends her logic to consider the role of photography in enforcing these norms.

El Espacio became known as the tabloid of ‘bodies’ in its regular presentation of mutilated corpses opposite images of nude women (Rincón Citation2013). Unless accusing the victims of perpetrating the crime, El Espacio never identified the perpetrator of these violent acts and rarely acknowledged the ongoing wartime contexts. El Espacio’s silence on perpetrators could have resulted from socio-political conditions of the time. As Arroyave-Cabrera has noted, ‘During the 1980s and 1990s, Colombia was considered one of the most dangerous countries in the world for a journalist to practice the profession’. Paramilitary, guerrilla and narcotrafficking groups all threatened and harassed journalists who reported on them, murdering many for their writing. Given the risks to their lives, most journalists opted for self-censorship to survive, establishing a norm of leaving out the actor in their reportage of violent affairs (Arroyave-Cabrera Citation2020; Uribe Citation1990). Further, some newspapers practiced self-censorship because of their support for paramilitary groups. Some newspapers were financed by local elites who were loyal to the paramilitary project and others were secretly owned by paramilitaries (Hristov Citation2009; Ritholtz Citation2022b; TVNoticias Citation2018).

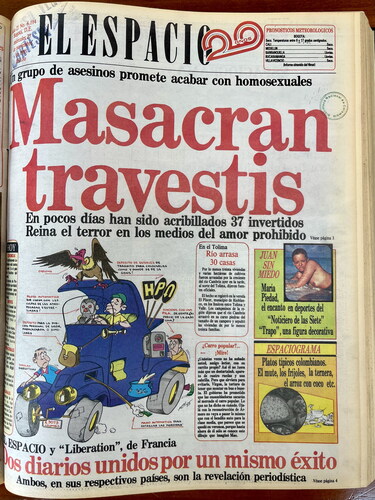

While this self-censorship silenced media coverage of perpetrators, it did not stop the coverage of the violence itself. Uribe discusses how this proclivity for the Colombian media to cover acts of violence without naming the actor produced a ‘“spectrality” that conceptualized actors as “dark forces of society,” thereby diluting their identities and distorting the intentions and rationality of their actors’ (2004, 91). A front-page story from 1985 illustrates this hysteria produced by spectrality. The headline in red reads ‘They are massacring travestis’Footnote12 (). The additional context in black adds ‘A group of assassins promises to put an end to homosexuals’ and ‘In the past few days, 37 invertidosFootnote13 have been shot. A reign of terror for those engaged in forbidden love’. The story further details that ‘dark criminals’ perpetrate this violence, adding that ‘the homicides have shown that they plan to exterminate many more in different regions of Colombia’.

Figure 1. El Espacio, 27 November 1985.

Source: National Museum of Colombia. Photo of Newspaper Coverage by Author. January 2023.

Another story acknowledges the role of ‘feared anti-homosexual [death] squads’Footnote14 in the murder of a gay man. Though not expanded upon, these articles’ authors were able to connect these series of murders with a national phenomenon of targeted collective anti-LGBTQ violence. These articles do not mention that, by the time of publication, the second cycle of the Colombian civil war was well underway and anti-LGBTQ violence was being adopted throughout the country by different armed groups in a process largely recognised as ‘cleansing’, or the targeted elimination of collective populations from contested territories (Steele Citation2017).

This silence in not identifying perpetrators produced a vacuum of accountability that media actors, and broader society, filled with prejudice. As a result, rather than documenting a pattern of violent victimisation by armed actors (as LGBTQ organisations in Colombia have done in recent years), tabloids like El Espacio contributed to a broader societal understanding that LGBTQ people were responsible for their own victimisation, thereby justifying the violence they experienced. El Espacio’s coverage reinforced an existing narrative of LGBTQ people in Colombia as moral degenerates, deviants and subversives. These narratives dehumanised LGBTQ people as ‘less than’, and potentially threatening to, the moral cis- and heterosexual citizenry of Colombia. The presentation of this violence through a sensationalist frame of sex and crime without any consideration of mourning produced a certain kind of ‘ungrievable’ subject worthy of this violence (Butler Citation2006). In presenting this violence as something intelligible, it became expected and thus, in a way, unremarkable if still scandalous.

The violence covered by El Espacio in such gruesome detail demonstrates the power of brutal display not only to attract the attention of a broader audience but also to reinforce narratives of (im)morality. By tying the murder of these individuals to ‘immoral’ behaviour, such as sexual impropriety, crime and violence, these media narratives depoliticised their deaths.

4.2. Front-page news

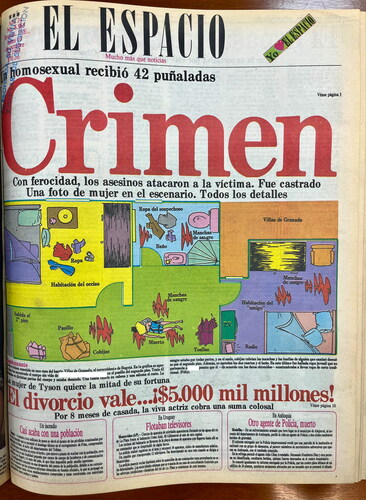

El Espacio was known around Colombia for its front pages. The masthead included the paper’s title as well as its signature phrase ‘much more than news’. The day’s headline appeared in a bright red font below the masthead and was often larger than the masthead itself. The headlines were attention-grabbing but short on details – one such headline reads ‘Crime’. Then, in smaller black or blue writing would be more detail that still encouraged curiosity through sensational brevity. To pair with the headline ‘Crime’, two lines of context: ‘a homosexual stabbed 42 times’, ‘with ferocity, the murderers attacked the victim. He was castrated. A photo of a woman at the scene. All the details’ (). These headlines highlight the gruesome details of the crime but deny the full story to the viewer. The goal is to grab one’s attention with the bright red characters and make one want to read more, even after the morsel of details in smaller black or blue characters.

Figure 2. El Espacio, 10 October 1988.

Source: National Museum of Colombia. Photo of Newspaper Coverage by Author. January 2023.

Next to these headlines, photographs or illustrations would take up more than half the front page. These illustrations often matched the headline. These matching images might incorporate a photograph of the deceased. The dead, often nameless, stare back at the viewer in a photo. Other times, the matching image is a cartoon rendering of the crime scene. Dead bodies are drawn, in pools of red blood, throughout the mock-up of the floor plan. In contrast to the front-page gore, the penultimate page of every issue would be reserved for photographs of nude women.

From the beginning, the violence is framed through a forensic presentation of spectacle. The salacious details lead, followed by further explication of the gore. The associated images add to the intrigue – black-and-white figures with empty stares, mutilated corpses, and blood-soaked cartoons. Little is done to contextualise or humanise the victims. The focus is not on the loss of life but on the drama of the story: a crime scene, a castration, death at the hands of the lover. Within this coverage, there is no mourning or grief. The narratives presented are seldom of loss or sadness but of gossip and confirmation of the behaviour of ‘perverted youth’.

4.3. In cold blood

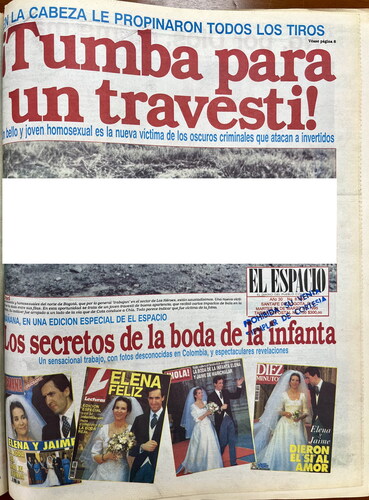

These front-page scenes began the spectacle, which would then be continued in the issue’s centre with a two-page centrefold devoted to the affair. Here, details and more context would be available, but still secondary to the photography. In these sections, it was not uncommon to find dead bodies displayed. Sometimes it would be a lifeless figure face down; other times it would be murder scenes in vivid detail: faces made unrecognisable from wounds and blood. The tabloid had no qualms about displaying these photographs; a level of casualness defines these photographs’ presentation. One story titled in bold red ‘Tomb for a travesti!’ detailed the affair as ‘All the shots were to the head…a beautiful and young homosexual is the newest victim of the dark criminals that attack invertidos’ ().

Figure 3. El Espacio, 28 March 1995.

Source: National Museum of Colombia. Photo of Newspaper Coverage by Author. January 2023.

The coverage presents a confounding tension between prejudice and care, ‘Tomb for a travesti’, who is then described as ‘beautiful and young’. This balance of care, as articulated by the concern for the lost youth, and prejudice, as articulated by the pejorative language relating to their LGBTQ identity, only deepens the intrigue – a beautiful lost homosexual felled by anonymous dark criminals. They are referred to as both a homosexual boy and travesti, which means there could be an element of misgendering in referring to the deceased.Footnote15 And there is the framing of ‘newest victim of the dark criminals that attack homosexuals’, which demonstrates how the media recognises the pattern of violent victimisation against LGBTQ people without attempting to identify the perpetrator. Below these complex and contradicting narratives is a photograph of the body of the deceased. The body is in a ditch, with their face exposed and head slightly askew. Similar to the iconography of a coffin, the pose confirms the death of the victim. But as with many victims of anti-LGBTQ violence, they have been denied the justice of a burial with dignity. Instead, their lifeless figure takes up half the page of the tabloid’s front page, which was so concerned with losing exclusivity or ownership of this image that a watermark, El Espacio, is placed just under the head of the deceased. The little information provides no context to the life of this victim. On that issue’s penultimate page appeared a naked woman in nothing but a pearl necklace and broad-brimmed hat. Both pages, then, feature photographs meant to entice the reader.

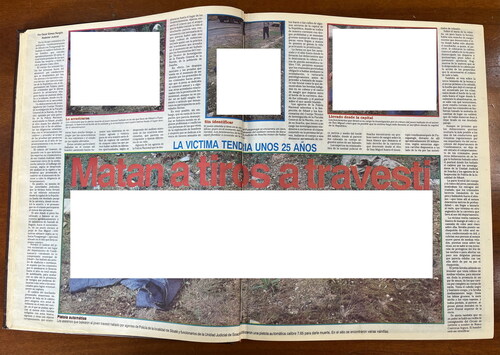

Other photographs from this archive present similar portraits of the dead with little dignity. In another photo spread, the red-print headline reads ‘Travesti shot to death’ (). The only context given is that ‘the victim would have been 25 years old’. The photograph here is a full two-page spread in the centrefold. The victim is face down in the dirt – their face unseen, dishevelled hair, and arms outstretched. They are wearing a blue article of clothing, perhaps a coat or dress, but they have on no bottoms. Tights are seen, perhaps also padding, but the shoes are still on. How did that happen? The image reeks of foul play, perhaps of a sexual nature. But again, there is no description of the perpetrator.

Figure 4. El Espacio, 6 November 1992.

Source: National Museum of Colombia. Photo of Newspaper Coverage by Author. January 2023.

These provocative images capture the imagination of the viewer, who is left wondering what happened. And though open graves are a common iconography of these archival materials – and cleansing more broadly – they are not the only ones. One of the most striking photographs comes from 1991. In this issue, two images reveal a murdered person and the surrounding scene. The main image is close up and shows the deceased, covered in blood. Their head turned to the side, eyes closed, with one arm raised above their head. A long, deep wound is visible on their neck, which suggests that their throat was slit. Their white covers are soaked in blood. The second image, taken from a few steps back, reveals the rest of the crime scene – a contorted body between white sheets and pillows, soaked in red, centres the frame. Around it is a chaos of other materials – clothes on the floor, drawers ripped open. The image would suggest a robbery; the headline suggests an alternative interpretation, a party. In classic red text, the headline ‘Orgy and death at a party of “gays”’ (). The added context in blue reads ‘One of the homosexuals had his throat slit (part 1)’ and ‘Between the sheets, he was found naked by the authorities’. And then, again in red, but in the same size as the context lines in blue, ‘they stabbed him in the heart’. No actors are named, but the grammar used suggests that there were multiple perpetrators and an overlap between the two categories of eroticisation and securitisation: an illicit orgy with a violent end. The editors felt that there was so much to unpack that this story deserved serial treatment: part 1.Footnote16 The editors again feared the loss of exclusivity of this material as the watermark appears near the head of the deceased, ‘El Espacio’.

Figure 5. El Espacio, 6 December 1991.

Source: National Museum of Colombia. Photo of Newspaper Coverage by Author. January 2023.

These photographs take in a literal sense Barthes’ (Citation1981) maxim that a photograph is the capturing of a dead moment. These photographs show the final moments of countless LGBTQ people. Rarely do they include any moments prior to their murder nor do they mention obtaining consent for the use of such photographs. Despite displaying, intimately, the form of their demise, these images do nothing to share the life of these people. As viewers of the spectacle, we do not know these people beyond their death. In many cases, a mix of limited detail, societal understanding, and prejudice prevents the viewer from knowing the actual sexual orientation or gender identity of the deceased. Still, for much of the Colombian public, these photographs were their only introduction to a marginalised, hidden population that had only just begun organising at a national level. Both Sontag (Citation2001, Citation2003) and Linfield (Citation2011) have recognised the productive capacity of photography either to engender empathy or to reinforce stereotypes and cheap understanding. Campbell (Citation2004) has underscored how these varied understandings result from the broader social construction that frames the phenomenon. The framing and presentation of a photograph, thus, can capture a moment and challenge opinion through the introduction of a critical perspective. The coverage of El Espacio reveals the more sinister potential of this power: while photography can enact change and facilitate empathy, the opposite is also true. The photography here diminishes empathy by establishing an association with the LGBTQ community and violence. These images thus exacerbated an existing prejudice against LGBTQ people by attributing their murder to their immoral behaviour and not to the political reality of a country at war.

4.4. ‘Pactos gay’: passion crimes and the eroticism of murder

One of the most prominent framings of the violence experienced by these populations is that of eroticisation. As the saying goes, ‘sex sells’, and adding in a perverse, dark element only appears to increase intrigue (Uzuegbunam and Udeze Citation2013). Within these texts, a common framing is el pacto gay (‘the gay pact’), referring to Romeo and Juliet-style suicides, where both lovers kill themselves because of insurmountable trouble (either they cannot be together or they have HIV and believe they will die). In one article from 1997, the headline in red reads ‘“Gay” pact of love and death!’.Footnote17 The accompanying image is of a bed, a fan, and two pillows. One contextual line of blue text explains that two boys killed themselves in a hotel and the other details the evening, ‘They entered the room of the residency, they wrote a letter, they were speaking for a long time, later they took syringes, and they injected themselves with cyanide with formaldehyde. The police found the bodies of the victims on the bed’. These captions do not explain the image, but it is inferred that this bed is where the act took place.

Adjacent to these narratives is crímenes de pasión (‘passion crimes’), which rather than framing the deaths as a double suicide, normally detail a jealous lover killing a partner, one headline reading ‘Passion, Love, and Death!’Footnote18 with the added context of ‘They killed for love’; the object of their affection after rejection, ‘They killed two young boys, in Bogotá, for rejecting their sexual advances;’Footnote19 an ex-lover and their new boyfriend, a ‘bloody homosexual triangle’;Footnote20 or the child of their lover, a ‘Lesbian drowns son of lover’.Footnote21 All of these framings position the LGBTQ person as responsible for their own murder or the murder of others in their community. This coverage introduces new discursive phrases that characterise this community with immoral behaviour and equate ‘gays’ with rage, jealousy and murder. Headlines read ‘Gay ire’,Footnote22 ‘Gay fury’,Footnote23 and ‘The jealousy of a “gay” is mortal’.Footnote24

In addition to these representations of intracommunal violence spurred by passion, there are moralising narratives within this broader eroticism. One such narrative is that of perversion – as in these LGBTQ people are ‘perverts’ that are out of control. Sometimes there is a direct reference to perversion in promotion of the sensationalist photographic coverage: ‘discover more photos of these perverted youth’.Footnote25 Other times, there is a focus on alleged immoral behaviour of the deceased. The headline next to a deceased gay man’s head is ‘He used to adore sex with sardinos’, or young boys.Footnote26 And then there is a more passive narrative of moralising judgement tied to a bacchanalian, or satanic, association with sexual impropriety. This narrative is perhaps most evident in how often the word ‘orgy’ is used to describe these death scenes. Orgies gone wrong – also referred to as a ‘mortal orgy’,Footnote27 ‘diabolic orgy’,Footnote28 and ‘orgies with the demon’.Footnote29 One article classifies the death of two homosexual men as ‘Rites of Sex and Satanism’, Footnote30 with the further context of ‘two homosexuals kill themselves between cults, fetishism, and voodoo’. Sexual excess and satanism become linked with brutal murder. Connecting the violent victimisation of these populations with their stigmatised erotic behaviour tacitly assigns responsibility for their death to the ‘amoral’ deceased.

4.5. Securitising poorly behaved ‘locas’: demons, drugs and crime

The second major narrative of this newspaper coverage is securitisation, a framing of certain behaviours (and identities) as both a criminal and a security risk that might require a ‘security interaction’ or mitigating response (Amar Citation2013; Hansen Citation2011, 59). Beyond this representation of a sex-crazed, bacchanalic community that is killing itself (with both HIV and brutal violence), there was an association of this community with a dangerous illicit economy. Coverage of LGBTQ violent victimisation was framed inside descriptions of drug deals, robberies and a dark, criminal underworld. In the 1990s, fear arose of LGBTQ gangs that were wreaking havoc among cities. El Espacio called these gay gangs ‘locas’, or crazy women. One headline in red reads ‘Locas attack’.Footnote31 The accompanying image is of a dead transfeminine person on the pavement. The context in blue adds ‘Here’s how the gay brawl went’ and ‘shots, screams, a cry, and finally two corpses on the cold pavement’. Thus, the coverage implies that the murder of these two transfeminine individuals was from fighting with other trans people. According to El Espacio coverage, the ‘locas’ targeted not just their own community but the broader community as well. A front-page headline of the paper reads in red ‘“Locas” and robbers!’,Footnote32 with its context in blue, adding ‘they used paralyzing gas’ and ‘they assaulted a taxicab driver and stole his car’. Here again, these victims are not presented as innocent but as deserving of their deaths because of their involvement in illicit behaviour. This connotation, seldom proven and often based on their sexual orientation and gender identities, reaffirms the idea that they were responsible for their own murder and could thus be blamed for their own victimisation. Such a connotation is easily reinforced when the framing is intracommunal violence and no armed actor is ever mentioned.

Related to this commentary on the criminal behaviour of ‘locas’, in another set of headlines, the newspaper uses language to frame groups of transfeminine individuals as gangs. In this frame of ‘gangs’, these newspapers were likely noting the propensity for queer and trans people to form family units as a result of familial and societal discrimination. These ‘chosen family’ dynamics have been well documented in the literature on queer articulations of kinship (Ritholtz and Buxton Citation2021), but to an uninformed observer, these group formations can appear threatening, especially when publicly associated with criminal violence. One article is titled ‘Three hours of fighting’Footnote33 and its subtitle reads ‘The homosexuals wanted to rule the streets’. In another front-page story, a title in red shares ‘Czar of the travestis!’Footnote34 and the context in blue adds ‘They killed him with a stab to the heart’ as well as ‘He was called Héctor, but they used to say to him ‘Soldier’. He charged all the ‘locas’ taxes in order to work in his estates’. Another headline refers to someone as a ‘sinner, homosexual, terrible sicario’,Footnote35 or hired assassin.

This language of organised criminal groups criminalises even the association or assembly of LGBTQ people. Their behaviours are framed as tied to illicit activities and, thus, so are their identities. This framing not only blames LGBTQ people for the violence they experience but also facilitates the process of legitimising violence used against them. By securitising not only their existence but also their deaths (through a logic of crime, not war), violence against this community can be justified in the language of cleansing, which would present this violence as ‘a difficult effort that must be undertaken in order to rein in a community that is terrorising itself and the broader community’.

5. Conclusion: covering an ‘apolitical’ violence with deeply political meanings

With this media coverage, El Espacio reinforced a broader norm in society that recognised the brutal victimisation of LGBTQ populations as an apolitical violence removed from wartime contexts. In pairing these images with narratives of subversion, amorality and criminality, the coverage of El Espacio contributed to a legitimising frame of collective anti-LGBTQ violence in Colombian society that denied its connection with the logics of war.Footnote36 These processes resulted from linking an entire collective with degeneracy, blaming the lethal victimisation of LGBTQ populations on their own behaviour, and never naming any perpetrators (aside from the victims themselves). These associations for LGBTQ populations were easy to frame as threatening to the broader public as a result of existing social prejudice, as well as a wartime logic of ‘moral orders’ against subversion, in much of the country.

Given the broader social silences at this time, these images of brutality were one of few introductions of this marginalised population to the general public and reified their difference. This brutal display reinforced stigma and moralised the violence, thereby legitimising the group’s violent victimisation. In focusing on their final moments and developing a public imaginary of decontextualised mutilated corpses felled by passion, crime or degeneracy, the cleavage of LGBTQ populations from the body politic of their community was reinforced and their status as ‘lesser’ was (re)constructed. In the years after this coverage, particularly in the wake of the 1991 constitution and the rise of a national LGBTQ rights movement in the 2000s, the LGBTQ community in Colombia has worked to regain control of this social narrative through the rigorous documentation and reporting of their own experiences of conflict, visibilising and presenting themselves as dignified subjects entitled to fundamental human rights and societal respect (see e.g., Caribe Afirmativo Citation2019; Colombia Diversa Citation2020; Comisión de la Verdad Citation2022; CNMH Citation2015, Citation2019).

Beyond representing cultural beliefs tied to LGBTQ populations, this media coverage also represents the socio-political effects of gendered violence during war. The violent exclusion of LGBTQ people produced public identities more akin to representations of social pathology in a culture affected by war than individuals worthy of respect, dignity and inclusion. The assumed public interest in the brutal display of mutilated LGBTQ bodies, given the tabloid obsession with producing them over decades, echoes Sontag’s recognition that ‘images of the repulsive can also allure’ (2003, 95). The graphic brutalisation of LGBTQ people in a society already at war still made headlines because it was fascinating. As a result, brutality became a communicative mechanism to legitimise collective violence against an immoral minority and produced a collective subjecthood associated with subversion. These broader media narratives reflected local narratives, where, in both rural and urban areas, armed actors would target LGBTQ populations, publicly justifying their violent behaviour as necessary to impose a moral order that would secure the town by removing these populations from the area (Ritholtz Citation2022b).

This article analyses media coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence as spectacle in order to recognise how a logic of brutal display permeated its graphic coverage of murdered LGBTQ people. It presents a theorisation of brutal display as a social mechanism of gendered subordination that becomes a way for acts of anti-LGBTQ violence to connect with broader social narratives of homo/transphobia aligned with moral orders imposed in a society at war. These narratives eroticise and securitise anti-LGBTQ violence, legitimating the phenomenon. The article recognises the broader social impact of brutal display as it relates to violence against LGBTQ people. It concludes with a close analysis of how this media coverage reinforced a cleavage of LGBTQ populations from the body politic. In doing so, it builds on the literature of gendered violence during war and visual IR to show how media coverage combines with local cultural narratives and wartime logics to depoliticise violence and subordinate those who are different.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the two anonymous reviewers as well as Priscyll Anctil Avoine, Regina Bateson, Natasha Bunzl, Kate Cronin-Furman, Meredith Loken, Roxani Krystalli, Wolfgang Minatti, Alyson Price, Nicholas Rush Smith, Fernando Serrano-Amaya, Megan Stewart, and the attendees of the 2022 ECPG, 2023 ISA, and 2023 APSA conferences for their kind and considerate comments on this challenging paper. A further special thanks to Masooda Bano, Alex Betts, Dara Kay Cohen, Stathis Kalyvas, Leigh Payne, Kiran Stallone, and Julia Zulver for their support with this piece as well as the broader research project from which it comes. The author also thanks their colleagues in Colombia who have aided with this research and, particularly, the researchers of the Gender Unit of the National Center of Historic Memory as well as the Hemeroteca archivists of the National Library of Colombia and the Luis Ángel Arango Library for their support.

Disclosure statement

All translations in this article were conducted by the author. All photographs of newspaper coverage were taken by the author. Newspaper coverage reproduced pursuant to Articles 33 and 34 of the Colombian Law No. 23 of 1982 on Copyright. The author has no interests to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samuel Ritholtz

Samuel Ritholtz (they/he) is Departmental Lecturer in International Relations at the Department of Politics and International Relations of the University of Oxford, in association with St Hilda’s College, and Max Weber Fellow at the Department of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute. They earned their DPhil in international development and MSc in refugee studies from the University of Oxford and a BSc in international agriculture and rural development from Cornell University. They research contemporary theories of violence, marginality and war, focusing on LGBTIQ + experiences of crisis, conflict and displacement in Latin America. Their work has been published in academic journals such as the American Political Science Review and in media such as The Guardian. Previously, they have worked for the United Nations, in the Office of the Secretary-General, and human rights organisations in Washington, DC; New York; and Buenos Aires.

Notes

1 In this article, headlines pulled from El Espacio newspaper coverage have been put into quotes, while secondary headlines and captions have been put into quotes and italicized.

2 I recognise anti-LGBTQ violence as a violence perpetrated against people of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, and expressions as a result of homophobia and transphobia. I use the emic term LGBTQ because it is the sexual orientation and gender identity term most widely understood in Colombian society and utilised by LGBTQ activists in country. As the presented media coverage did not include intersex lives, this analysis does not include endosexist violence.

3 This consideration is much more common in scholars of history and historical IR.

4 I censored the graphic brutality of these images as I felt it the most appropriate for a journal article format. With limited space and a broad viewership, I worried that I would not be able to present these images in enough detail to warrant a reproduction of the brutal display. Many colleagues, interlocutors, and survivors of violence in Colombia understood but still disagreed with this decision. In personal conversations, many supported publishing the original photos—without any censoring of graphic imagery—in order to ‘show how things were’ and to force the reader to confront the ‘perpetrator’s gaze’, particularly to a predominately English-speaking audience. While recognizing that this group does not speak for all survivors in Colombia, I took these insights seriously in my own considerations.

5 Original photos on file with the author. Newspaper coverage reproduced pursuant to Articles 33 and 34 of the Colombian Law No. 23 of 1982 on Copyright.

6 As the unit’s archive only included El Espacio coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence, I was not originally able to compare this coverage with other groups. After reviewing the unit’s archive, I then went directly to the archives of the National Library of Colombia and the Luis Ángel Arango Library. From the work of scholars such as Omar Rincón, in dialogue with my peers in Colombia, and through my own review of El Espacio archives, I know that El Espacio covered acts of violence with graphic imagery of other groups but with different narratives. This piece’s argument does not compare one form of coverage with others, but instead focuses on understanding the social constructions developed and reinforced by this specific coverage of anti-LGBTQ violence.

7 El Espacio, 11 October 1991.

8 This does not mean that lesbian, bisexual, and queer women, trans men, and transmasculine individuals did not experience targeted anti-LGBTQ violence – they did – but, as with this phenomenon’s broader trends, this violence was more private in nature (CNMH Citation2015).

9 El Espacio, 28 March 1995.

10 El Espacio, 10 October 1988.

11 El Espacio, 25 July 1991.

12 Travesti is a gender identity found throughout Latin America for people with a feminine gender identity who were assigned male at birth. While originally a pejorative, it has been reclaimed by the community and can be variably translated as a unique transfeminine non-binary gender identity or as a trans woman. I do not translate the term, to recognise the cultural specificity of transfeminine identities in Colombia. El Espacio, 27 November 1985.

13 Invertido is an old-fashioned, Spanish-language pejorative (and former medical term) used to describe queer and trans people (Simonetto Citation2024).

14 El Espacio, 23 June 1985.

15 While in general misgendering is considered an act of prejudice, in this time period, it could also be representative of a poor understanding of trans identities by the media as well as travestismo and homosexuality being considered interchangeable concepts to broad segments of society. El Espacio, at the time, seems to have conceptualised travestis not as transgender women or transfeminine non-binary people but as ‘men with the features of women’.

16 The headline for part 2: “Diabolic orgy.” El Espacio, 6 December 1991.

17 El Espacio, 13 May 1997.

18 El Espacio, 2 October 2003.

19 El Espacio, 25 September 1990.

20 El Espacio, 14 October 1988.

21 El Espacio, 5 August 1997.

22 El Espacio, 14 May 1996.

23 El Espacio, 29 November 1993.

24 El Espacio, 20 March 1991.

25 El Espacio, 11 October 1988.

26 El Espacio, 7 December 1991.

27 El Espacio, 29 March 1991.

28 El Espacio, 6 December 1991.

29 El Espacio, 26 October 1993.

30 El Espacio, 26 October 1993.

31 El Espacio, 4 March 1994.

32 El Espacio, 21 September 1998.

33 El Espacio, 8 February 1994.

34 El Espacio, 30 April 1999.

35 El Espacio, 9 March 1989.

36 In modern-day Colombia, the LGBTQ rights organisation Colombia Diversa has advocated for the recognition of anti-LGBTQ violence during the Colombian Civil War as a crime against humanity.

References

- Amar, P. 2013. The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics, and the End of Neoliberalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Arjona, A. 2016. Rebelocracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Arroyave-Cabrera, J. A. 2020. “Colombia.” Media Landscapes. https://medialandscapes.org/country/colombia

- Bardall, G., E. Bjarnegård, and J. Piscopo. 2020. “How Is Political Violence Gendered? Disentangling Motives, Forms, and Impacts.” Political Studies 68 (4): 916–935. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719881812

- Barthes, R. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. London: Macmillan.

- Boesten, J. 2014. Sexual Violence during War and Peace: Gender, Power, and Post-Conflict Justice in Peru. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Butler, J. 2006. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso.

- Campbell, D. 2003. “Cultural Governance and Pictorial Resistance: Reflections on the Imaging of War.” Review of International Studies 29 (S1): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210503005977

- Campbell, D. 2004. “Horrific Blindness: Images of Death in Contemporary Media.” Journal for Cultural Research 8 (1): 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1479758042000196971

- Caribe Afirmativo. 2019. ¡Nosotras resistimos! Informe sobre Violencias contra Personas LGBT en el Marco Del Conflicto Armado en Colombia. Barranquilla: Caribe Afirmativo.

- Cavarero, A. 2009. Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence. New York: Columbia University Press.

- CNMH. 2015. Aniquilar La Diferencia: Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales Y Transgeneristas en el Marco del Conflicto Armado Colombiano. Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica.

- CNMH. 2019. Ser Marica en Medio del Conflicto Armado. Memorias de Sectores Lgbt En El Magdalena Medio. Bogota: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica.

- Cockburn, C. 2004. “The Continuum of Violence: A Gender Perspective on War and Peace.” In Sites of Violence, edited by W. Giles and J. Hyndman, 24–44. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cohen, D. 2016. Rape during Civil War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Colombia Diversa. 2020. “Orders of Violence: Systematic Crimes against LGBT People in the Colombian Armed Conflict.” Bogota: Colombia Diversa. https://colombiadiversa.org/publicaciones/orders-of-prejudicecrimes-committed-against-lgbt-people-in-the-colombian-armed-conflict/

- Cooper-Cunningham, D. 2019. “Seeing (in)Security, Gender and Silencing: Posters in and about the British Women’s Suffrage Movement.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 21 (3): 383–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2018.1561203

- Cooper-Cunningham, D. 2024. “The Visual as Queer Method.” In Queer Conflict Research, edited by J. Hagen, S. Ritholtz, and A. Delatolla, 83–106. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Crane, S. 2008. “Choosing Not to Look: Representation, Repatriation, and Holocaust Atrocity Photography 1.” History and Theory 47 (3): 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2008.00457.x

- Das, V. 2008. “Violence, Gender, and Subjectivity.” Annual Review of Anthropology 37 (1): 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.36.081406.094430

- Comisión de la Verdad. 2022. “Mi Cuerpo Es La Verdad Mujeres LGTBIQ.” Bogotá.

- Debord, G. 2014. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Ken Knabb. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets.

- Feierstein, D. 2014. Genocide as Social Practice: Reorganizing Society under the Nazis and Argentina’s Military Juntas. Genocide, Political Violence, Human Rights Serie. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Fujii, L. 2021. Show Time: The Logic and Power of Violent Display. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Gómez, M. 2013. “Prejudice-Based Violence.” In Gender and Sexuality in Latin America – Cases and Decisions, edited by C. Motta and M. Saez, 279–323. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Gómez-Dueñas, M. C. 2012. “Sexualidad y violencia. Crímenes por prejuicio sexual en Cali. 1980–2000.” Revista CS 10 (December): 169–206. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i10.1358

- Hansen, L. 2011. “Theorizing the Image for Security Studies: Visual Securitization and the Muhammad Cartoon Crisis.” European Journal of International Relations 17 (1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110388593

- Hartman, S. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1

- Hartman, S. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Hoover Green, A. 2018. The Commander’s Dilemma: Violence and Restraint in Wartime. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hozić, A. 2017. “Introduction: The Aesthetic Turn at 15 (Legacies, Limits and Prospects).” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 45 (2): 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829816684253

- Hristov, J. 2009. Blood and Capital: The Paramilitarization of Colombia. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Humphrey, M. 2013. The Politics of Atrocity and Reconciliation: From Terror to Trauma. Vol. 34. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Krystalli, R. 2021. “Narrating Victimhood: Dilemmas and (in)Dignities.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 23 (1): 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2020.1861961

- Krystalli, R., and P. Schulz. 2022. “Taking Love and Care Seriously: An Emergent Research Agenda for Remaking Worlds in the Wake of Violence.” International Studies Review 24 (1): viac003. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viac003

- Lerner, A. 2021. “The Co-Optation of Dissent in Hybrid States: Post-Soviet Graffiti in Moscow.” Comparative Political Studies 54 (10): 1757–1785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019879949

- Linfield, S. 2011. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Loken, M. 2021. “‘Both Needed and Threatened’: Armed Mothers in Militant Visuals.” Security Dialogue 52 (1): 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620903237

- Loney, H., and A. Pohlman. 2022. “‘This Is What Happens to Enemies of the RI’: The East Timor Torture Photographs within the New Order’s History of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence.” Indonesia 114 (1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1353/ind.2022.0010

- Minwalla, S., J. Foster, and S. McGrail. 2022. “Genocide, Rape, and Careless Disregard: Media Ethics and the Problematic Reporting on Yazidi Survivors of ISIS Captivity.” Feminist Media Studies 22 (3): 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1731699

- Moser, C., and F. Clark. 2001. Victims, Perpetrators or Actors?: Gender, Armed Conflict and Political Violence. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ore, E. 2019. Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Reinhardt, M. 2012. “Painful Photographs: From the Ethics of Spectatorship to Visual Politics.” In Ethics and Images of Pain, edited by A. Grønstad and H. Gustafsson, 57–80. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Rincón, O. 2013. “El Espacio: un muerto de propia mano.” Razón Pública (blog), December 2, 2013. https://razonpublica.com/el-espacio-un-muerto-de-propia-mano/

- Ritholtz, S. 2022a. “The Ontology of Cruelty in Civil War: The Analytical Utility of Characterizing Violence in Conflict Studies.” Global Studies Quarterly 2 (2): ksac014. https://doi.org/10.1093/isagsq/ksac014

- Ritholtz, S. 2022b. “Civil War & the Politics of Difference: Paramilitary Violence Against LGBT People in Colombia.” PhD diss., Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

- Ritholtz, S., and R. Buxton. 2021. “Queer Kinship and the Rights of Refugee Families.” Migration Studies 9 (3): 1075–1095. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnab007

- Serrano-Amaya, J. F. 2018. Homophobic Violence in Armed Conflict and Political Transition. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Shepherd, L. J. 2017. “Aesthetics, Ethics, and Visual Research in the Digital Age: ‘Undone in the Face of the Otter’.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 45 (2): 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829816684255

- Simonetto, P. 2024. “Queer Tools for the Ruthless Archive.” In Queer Conflict Research, edited by J. Hagen, S. Ritholtz, and A. Delatolla, 128–153. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Smith, N. R. 2020. “Member-Checking: Lessons from the Dead.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 17–18 (1): 60–66. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3946827

- Snorton, C. R., and J. Haritaworn. 2013. “Trans Necropolitics.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, Vol. II, edited by A. Aizura and S. Stryker, 66–76. New York: Routledge.

- Sontag, S. 2001. On Photography. Vol. 48. London: Macmillan.

- Sontag, S. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York and London: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Stallone, K., and J. Zulver. 2024. “The Gendered Risks of Social Leadership in Contexts Governed by Armed Groups: Evidence from Colombia.” Journal of Peace Research, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433231220261

- Steele, A. 2017. Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Stewart, M. 2021. Governing for Revolution: Social Transformation in Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Suárez, A. 2022. El Silencio Del Horror.: Guerra y Masacres En Colombia. Bogota: Siglo del Hombre Editores.

- Subotić, J. 2021. “Ethics of Archival Research on Political Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 58 (3): 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319898735

- Taylor, D. 1997. Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War”. Durham: Duke University Press.

- TVNoticias. 2018, October 10. “Dueño de el meridiano, investigado por la fiscalía.” https://www.tvnoticias.com.co/dueno-de-el-meridiano-investigado-por-la-fiscalia/

- Uribe, M. V. 1990. Matar, Rematar y Contramatar: Las Masacres de La Violencia En El Tolima, 1948-1964. Vol. 159. Bogota: CINEP.

- Uribe, M. V. 2004. “Dismembering and Expelling: Semantics of Political Terror in Colombia.” Public Culture 16 (1): 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-1-79

- Uzuegbunam, C., and S. Udeze. 2013. “Sensationalism in the Media: The Right to Sell or the Right to Tell.” Journal of Communication and Media Research 5 (1): 69–78.

- Wedeen, L. 2015. Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Windfeld, F., M. Hvithamar, and L. Hansen. 2023. “Gothic Visibilities and International Relations: Uncanny Icons, Critical Comics, and the Politics of Abjection in Aleppo.” Review of International Studies 50 (1): 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000547

- Wood, A. L. 2011. Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Wood, E. J. 2018. “Rape as a Practice of War: Toward a Typology of Political Violence.” Politics & Society 46 (4): 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329218773710