Back in 1999, I hired a student to go through a year’s worth of the New York Times to find and catalog articles about transportation. These articles described a wide range of issues: growing impatience for new rapid transit lines and diminishing hopes of getting them, promises of better transfer systems and faster transit times to the suburbs, controversies over allowing cars in Central Park, calls to provide space for bicyclists on bridges, concerns over crashes caused by reckless driving, and disappointment over budget cuts for a boulevard project. I’m sure this list is not at all surprising to you, even if you don’t know much about New York City, as these are the kinds of issues that cities everywhere faced at the start of the twenty-first century. But you may be surprised to hear that the year we focused on was not 1999 but rather 1899. The details may have changed, but 100 years later the general issues looked stubbornly the same.

It often seems that the transportation field is going in circles, or at least talking in circles. In my 30 or so years in the transportation field I have had the opportunity to personally observe some of the ebb and flow of our collective ideas. We’ve been discussing many of the same issues for those three decades and more without making substantial progress towards resolving them. We sometimes promote new ideas that in fact are not as new as we think, ideas that our predecessors promoted in the past although with different motivations. Some of us push favourite ideas without gaining much traction with the rest of the field, but we keep pushing them anyway. I have recently come across several interrelated examples of roundabout discussions in which we are seemingly stuck.

Congestion is one issue that hasn’t gone anywhere in well over a century: its existence, our frustration with it, or our obsession with finding a solution to it. Cities have always had congestion of some type and degree. What changed with the industrial revolution was the clash between the reality of traffic jams and the expectation of speed that grew over time with the advent of streetcars, then cars, then freeways. As Asha Agrawal (then Weinstein) painstakingly documented in her dissertation work, Bostonians complained about and demanded relief from congestion in the 1890s, when streetcars were the primary traffic culprit on downtown streets, and they continued to complain in the 1920s after a subway system had cleared the streets of streetcars but when automobiles were increasingly taking their place: “virtually no one took the position that congestion was not problematic” or argued that it did not merit public intervention, even if they did not agree on why congestion was such a problem (Weinstein, Citation2006).

Frustration with congestion went far beyond Boston, of course, and it did not end in the 1920s even with the invention of traffic engineering. In the 1950s, the Wonderful World of Disney television show jumped into the discussion with its “Magic Highway U.S.A.” episode,Footnote1 in which Uncle Walt told the country that “[o]ur growing abundance and our pursuit of happiness is dependent upon the greatest highway system in the world” and that “[i]f these arteries continue to become overburdened and clogged, our nation’s economy will be strangled”. Today, congestion relief remains an official federal priority. U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, as he prepared to leave his position in January 2017, argued that “ … congested roads and bridges in our nation must be addressed head on” and so he issued new rules that “will play an important role in reducing travel delays … ”Footnote2 So many decades of unsuccessful attempts to reduce congestion have clearly not led to widespread acceptance of their futility.

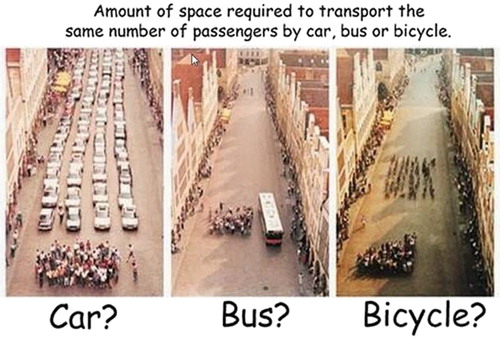

One of the ideas I grew up with, professionally speaking, is the idea that transportation planning should focus on moving people rather than cars. Such an approach doesn’t necessarily reduce congestion, but it does use the limited street space we have more efficiently, reduce energy consumption and air pollution, and produce other benefits for communities. The widely shared graphic comparing the space taken up by a busload of people to the space taken up if these same people were all in their own cars effectively illustrates this idea, and it has by now achieved the status of a meme (). I’m not sure where I first encountered this idea, though my memory is that advocacy groups were promoting it in the lead-up to the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) of 1991. Yesterday I received an email from T4AmericaFootnote3 updating me on the organisation’s success in pushing the U.S. Department of Transportation to change its guidance on performance metrics to focus on “moving people rather than cars”. My Google search today of the phrase “moving people rather than cars” generated “about 74,200,000 results”.

Figure 1. Example of mode space meme. Source: Press-Office City of Müenster, Germany. http://www.treehugger.com/htgg/how-to-go-green-public-transportation.html

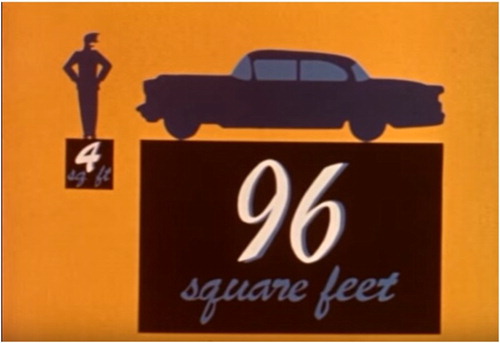

The idea appears to go back much farther than the 1990s, however. I recently came across a short PR filmFootnote4 put out by General Motors (GM) in the 1950s that, I was surprised to find, called for city planners to “emphasise the movement of people rather than vehicles”. This, the narrator argues, is the solution to the downtown congestion problem resulting from “[t]en thousand new cars … being born every day” while “the streets remain the same size”. Focusing on moving people means focusing on buses, the film contends, not surprising given that GM was a major manufacturer of buses at the time. This film could be the origin of the car-space versus bus-space meme, as it shows video clips of a city block first full of private cars then with a single bus. More than once, it asserts that a “modern motor bus” carries the same number of people as 34 private cars, each with 1.5 occupants; a car takes up far more space than a person (). The overt goal of the film is to encourage policies that support bus systems (which were mostly private at that time), including the elimination of parking along urban arterials so as to provide more traffic lanes, including bus-only lanes. In other words, GM hoped to wring more vehicle capacity out of the existing right-of-way. T4America also supports bus systems, but (to put words in their mouth) prefers to do so in ways that do not increase vehicle capacity. Same idea, different aims.

Figure 2. Image from “let’s go to town”/general motors corporation. http://www.citylab.com/commute/2016/08/1950s-general-motors-film-buses/496694/

Speaking of more traffic lanes, an idea that has not yet gotten the widespread acceptance it deserves (at least in the opinion of many of us academics) is the concept of induced travel. The economic explanation of this phenomenon is straightforward: an increase in roadway capacity reduces the cost of driving, and when cost goes down, volume goes up. In short, the easier driving gets, the more people drive. Brian Ladd’s eye-opening Citation2012 paper documents professional recognition of this effect even before the automotive age, followed by continued recognition of the effect among some in the profession and perpetual resistance among the rest (Ladd, Citation2012). Interestingly, that same GM film reflects both recognition and resistance. At one point, the narrator laments,

… the more they build, the more we need. It’s like emptying the ocean with a teaspoon. Every one of these steps [including building expressways and widening streets] has encouraged more and more private car operators to drive downtown making things worse than ever before.

Despite solid empirical evidence by now that increased highway capacity does indeed lead to increased vehicle travel, many public officials as well as transportation professionals are strangely though perhaps not surprisingly impervious to the idea. In 2015, my summary of the evidence (Handy, Citation2015) was highlighted in an article in a newsletter published by Caltrans, as the California Department of Transportation is known. This led several media outlets to conclude – and publish articles to the effect – that Caltrans had accepted the idea that “more roads mean more traffic”,Footnote5 at which point Caltrans pulled the article from its own website. Last week I received an email from a citizen concerned about how the California Transportation Commission is ignoring the issue of induced travel in its updates to the guidelines for regional transportation planning in the state. It is very hard, I think, for agencies whose primary mission for decades has been the expansion of the highway system to accept the fact that this approach might not be as helpful as they hope in solving our congestion problem.

Also slow to gain traction is the idea that accessibility rather than mobility should be the goal, that transportation plans should aim for ease of access to activities rather than ease of movement. This idea, too, goes back decades. When I wrote about the distinction between the two concepts in Access magazine in Citation1994, under the expert editorial hand of Mel Webber, I heard from planners throughout the country who thanked me for articulating an idea they had long embraced but had not succeeded in bringing into practice. I have an old overhead transparency from my job talk, in which I listed my post-dissertation research plans, including “develop accessibility measures for use in planning practice”. I dabbled in this arena for a bit, but others took it on more ardently, including Jonathan Levine, who leads a multi-year effort to develop accessibility metrics in the U.S., and the team of researchers led by Cecilia Silva in the COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) project on Accessibility Instruments for Planning Practice in Europe, which wrapped up in 2016. Accessibility measures are still not standard in planning practice after all this time, though many Metropolitan Planning Organisations in the U.S. have adopted a form of accessibility measure for use in their equity analyses. When I promote the idea of accessibility versus mobility in presentations to professional audiences, I feel like I’m either preaching to the choir or talking over their heads. You get it or you don’t.

I’m sure that roundabout discussions like this are not unique to the transportation field. But transportation may be particularly susceptible for a variety of reasons. Transportation is a tough problem. How do we meet societal needs for transportation while living within our means and minimising negative impacts for the environment and society? We have no easy and straightforward answers. Transportation often involves very large, lumpy investments, all-in or all-out, that beget big debates and incite politically charged decision making. Just look at California’s attempt to build high-speed rail. In addition, transportation affects everyone, everyone has a stake, and everyone has an opinion. Ever tell a new acquaintance at a party that you are a transportation planner? You’ll see what I mean. Last but not least, transportation is rooted in engineering, with its strong ideas about optimal solutions, right and wrong practices, and official professional guidelines. For a field that recognises the importance of expert judgement, we often do a disappointingly poor job of encouraging and supporting independent thought.

I’ll be curious to see where the field stands on these issues when I retire in 10 (?!) years. Will we have successfully navigated our way out of these roundabout discussions and moved on, perhaps, to new ones? I like to think that we academics have an important role to play in leading the field out of the roundabout and onto a more productive path by providing rigorous evidence on these issues, but we have plenty of examples of failure to abandon long-held ideas or adopt new ones even when a change in thinking is supported by the evidence. The advent of potentially “disruptive” innovations such as ride-sharing services and automated vehicles has already shifted our attention to new issues and may be disruptive enough that old debates lose their importance. I have a sneaking suspicion, however, that when I meet my new neighbours in that retirement community of my future and I tell them what I did for a living, they will say, “Traffic is worse than ever! Why don’t they just … ”

Notes

4. “Let's Go To Town – Solutions to City Traffic Congestion”. http://www.citylab.com/commute/2016/08/1950s-general-motors-film-buses/496694/.

References

- Handy, S. (1994). Highway blues: Nothing a little accessibility can't cure. Access, 5, 3–7.

- Handy, S. (2015). Increasing highway capacity unlikely to relieve traffic congestion. Policy Brief. National Center for Sustainable Transportation. Retrieved from https://ncst.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/10-12-2015-NCST_Brief_InducedTravel_CS6_v3.pdf

- Ladd, B. (2012). You can’t build your way out of congestion – or can you? The Planning Review, 48(3), 16–12. doi:10.1080/02513625.2012.759342

- Weinstein, A. A. (2006). Congestion as a cultural construct: The “congestion evil”. Journal of Transport History, 27(2), 97–115. doi: 10.7227/TJTH.27.2.9