ABSTRACT

The rise of e-commerce has led to substantial changes in personal travel and activities. We systematically reviewed empirical studies on the relationship between online shopping and personal travel behaviour. We synthesised and assessed the evidence for four types of effects on various travel outcomes, including trip frequency, travel distance, trip chaining, mode choice, and time use. In 42 articles reviewed, we found more evidence that online shopping substitutes for shopping travel. Most studies to date have focused on trip frequency but neglected other travel outcomes. Very few studies have considered the modification effect, which has significant implications for travel demand management. In sum, previous studies have not reached a consensus on the dominant effect of online shopping, in part due to the diversity in variable measurements, types of goods, study areas, and analytic methods. A limitation of previous studies is the reliance on cross-sectional surveys, which hinders the distinction between short- and long-term behaviours and between modification, complementarity, and substitution effects. Our study provides an agenda for future research on this topic and discusses policy implications related to land use, behavioural changes, data collection, and modelling for practitioners who wish to incorporate e-commerce in planning for sustainable urban systems.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, the number of online shopping portals, breadth of products available online, and access to fast internet have continuously grown. This development has led to both a maturing of online shopping as a retail channel and profound changes in people's shopping behaviour. In 2019, online sales were estimated to account for $3.36 trillion or 13.6% of retail sales globally, representing a 20.2% increase over the previous year (Cramer-Flood et al., Citation2020). This includes 34.1% of total retail sales in China, 21.8% in the UK, and 11% in the US. The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have induced a further surge in online shopping.

This development has had large impacts on households’ travel behaviour with corresponding shifts in traffic, emissions, and energy consumption by private household vehicles and delivery vehicles. Furthermore, online shopping has often entailed the expansion of fulfilment centres and the closure or downsizing of physical stores, changing land use patterns, and decreasing accessibility to shopping opportunities especially for vulnerable populations who may lack access to the required technology and banking services. Addressing the resulting land use, environmental and social challenges requires a detailed understanding of the nature of the impacts of online shopping on travel, which have been the subject of a rapidly expanding and evolving body of literature.

The literature on online shopping is embedded in the broader literature on the relationship between information and communication technologies (ICT) and travel behaviour. There are four possible effect types of online shopping on travel behaviour, as identified and described by Salomon (Citation1985, Citation1986), Mokhtarian (Citation1988, Citation1990, Citation2002), and Mokhtarian and Meenakshisundaram (Citation1999): shopping online may substitute for shopping travel, may be complementary to it and therefore lead to increased shopping travel, may modify the nature and patterns of shopping trips, or may have a neutral effect (i.e. no effect). Various studies across the globe have found empirical evidence for one or more of these effects of online shopping on travel, with the specific type of effect driven by product attributes, geographical location, and culture, among other variables. The empirical evidence remains scattered with sometimes contradictory findings. This complicates the forecasting of impacts of online shopping on passenger and freight traffic patterns, urban form, and air quality.

This paper aims to synthesise literature and identify major themes that support a more systematic understanding of the relationship between online shopping and travel. We present a review of empirical studies from 1990 to early 2020, focusing on five travel outcomes that are important to transportation modelling and management practice, namely trip frequency, travel distance, trip chaining, mode choice, and time use. This review can help researchers and practitioners understand the impacts of online shopping on travel demand to (1) improve the current practice of travel demand modelling as it typically does not include online shopping, (2) provide inputs to other models that rely on travel demand models, such as models of land use and traffic-related environmental impacts, and (3) manage travel demand, and specifically vehicular traffic, to relieve congestion.

Our paper uniquely contributes to the literature by (1) providing an exhaustive, systematic review of the empirical evidence over 30 years, (2) assessing the quantity and quality of evidence related to five travel outcomes that are important to transportation modelling and management practice, and (3) providing a future research agenda based on the empirical gaps identified in our review to further advance quantitative evidence on online shopping and travel.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: the “Overview of theoretical background” section describes conceptual developments in this area. Following that is the “Methods” section which describes the search procedure and article selection criteria. We then provide an overview of studies and synthesise literature based on the five travel outcomes previously listed. Finally, we analyse the limitations of past studies and present an agenda for future research.

2. Overview of theoretical background

2.1. Definitions of concepts

In this article, we defined online shopping as a purchase made by a consumer from a business through an online channel, otherwise known as B2C. Shoppers may or may not search for information online prior to the purchase. This definition is narrower than the definition used in a prior review article by Rotem-Mindali and Weltevreden (Citation2013) which concerns passenger and freight transportation as well as business-to-consumer and consumer-to-consumer (C2C) purchases. The narrower focus of our definition helps us limit the scope of this paper and aligns with the scope of many other transportation-online shopping studies (e.g. Cao, Citation2009; Zhou & Wang, Citation2014).

The amount and type of personal travel, which at an aggregate level constitutes travel demand, is commonly quantified using a variety of metrics (see, e.g., McGuckin & Fucci, Citation2018), including trip frequency, mode choice, travel distance, trip chaining behaviour, and time spent travelling. Trip frequency quantifies the number of shopping trips made by a person, regardless of length, destination, or other characteristics. Online shopping studies have varied in how they measured trip frequency, ranging from travel diaries (e.g. Ferrell, Citation2005) to respondents’ subjective perceptions (e.g. Lee, Sener, Mokhtarian, & Handy, Citation2017). The mode choice metric focuses on the mode used for a trip (e.g. Suel, & Polak, Citation2017), and the travel distance metric refers to the total distance travelled by any mode for shopping purposes (e.g. Holguín-Veras, & Sánchez-Díaz, Citation2016). The trip chaining metric captures whether a traveller combined a shopping trip with a trip for another purpose (e.g. Ferrell, Citation2005). The travel time metric quantifies how much time a person spent travelling for shopping purposes, and it is often measured alongside activity times, such as the time spent shopping (e.g. Farag, Schwanen, Dijst, & Faber, Citation2007).

2.2. Effects of ICT on travel

Substitution and complementarity effects, where ICT use was hypothesised to either replace travel (substitution) or generate additional travel (complementarity), were first discussed by Salomon (Citation1986) and Mokhtarian (Citation1988, Citation1990). Modification effects refer to changes in travel patterns (e.g. destinations, routes, travel modes, travel times, or shopping durations) due to ICT use (Mokhtarian & Meenakshisundaram, Citation1999; Salomon, Citation1985). Finally, neutrality describes the case where no effects of ICT use on travel occur (Mokhtarian, Citation1990; Salomon, Citation1985).

The effect of ICT on travel behaviour will differ depending on the type of activity being conducted or the type of product or service purchased (Mokhtarian, Salomon, & Handy, Citation2006). An activity conducted via ICT will not always replace a travel-based activity of the same type, and Mokhtarian (Citation1990) argued that even if ICT substitutes for travel, overall travel demand may continue to grow due to the growth of the underlying markets and efficiency gains. Aside from the direct effects discussed here, land use modifications induced by changing shopping behaviours may have further indirect and long-run effects on travel behaviour (Salomon, Citation1985).

Another effect known in the ICT literature is the rebound effect (Masanet & Matthews, Citation2010), which holds that when an activity becomes more efficient, the money and time saved from that efficiency may stimulate additional consumption. Thus, as online shopping makes the shopping process more efficient, rebound effects may happen in the form of a reallocation of or increase in travel demand, with potential negative impacts on the transportation systems and the environment. The rebound effect can be considered a subset of the complementarity and modification effects.

2.3. Space–time convergence: time geography and modification of activity and travel

Theoretical and conceptual studies in time geography further illustrate possible pathways through which online shopping can modify travel and activity choice patterns. Specifically, the ability to shop online decouples shopping spatially and temporally from other activities. An individual’s activities follow three constraints: individual capability constraints, e.g. the reach of available transport systems; authority constraints, such as those imposed by store opening hours or national borders; and coupling constraints, which require the presence of other entities for an activity to be performed (Hägerstrand, Citation1970). To understand the effect of “going online” on the interactions between these constraints and shopping activities, one must first recognise that shopping is a complex activity that can be decomposed into several individual subtasks (Couclelis, Citation2004). Among others, they include information gathering, trial and evaluation, the transaction, getting the item to base (home), and possibly returning the item. When shopping in-store, these activities are place-bound and often integrated.

In online shopping, the fragmentation of activity hypothesis postulates that these subtasks become fragmented in space and time and can be carried out independently of each other (Couclelis, Citation1998). Shopping can now be performed within shorter amounts of time and without spatial and time constraints (e.g. store locations and opening hours), does not need the presence of others such as shop assistants, and can be combined with other activities such as travelling (by “multitasking”). A consequence of the fragmentation is also that the various subtasks can be recombined, rescheduled, and redistributed among household members, all in varying configurations, with some occurring locally and others remotely (Dijst, Kwan, & Schwanen, Citation2009; Mokhtarian, Citation2004), which then lead to changes in trip chain configurations, destinations, travel modes, and time use for each task. The notion of activity fragmentation is therefore related to the modification effect and informs the design of empirical studies to quantify the modification effects of online shopping on travel.

2.4. Stages of shopping and types of goods

The various subtasks or stages of shopping are associated with different travel patterns, which can explain the difference in results from studies that did and did not account for pre-purchasing behaviour. They also demonstrate the complexity of determining the direct effect of online shopping on travel. In the classification presented by Couclelis (Citation2004), shopping involves several pre-purchase behaviours (e.g. searching, reviewing products and alternatives, selecting products and vendors), purchase behaviours (e.g. transaction, tracking status, delivery), and post-purchase behaviours (e.g. returning or exchanging the item). Mokhtarian (Citation2004), based on earlier work by Schiffman and Kanuk (Citation1987) and Salomon and Koppelman (Citation1988), presents a similar classification albeit with fewer stages. Not all instances of shopping involve all subtasks, and some subtasks may be carried out more than once in each instance. Whether or not each subtask or stage occurs online or in-store has different implications on travel outcomes (Hoogendoorn-Lanser, Kalter, & Schaap, Citation2019). While most studies to date have focused on the actual purchase of the item, fewer studies focused on pre-purchase activities, and no studies in our review considered post-purchase activities.

The type of good may also affect the relationship between online and in-store shopping. For search goods (e.g. books), the shopper can make purchase decisions easily with online information, whereas for experience goods (e.g. clothing), personally experiencing the item before purchasing is important (Chang, Cheung, & Lai, Citation2005). The former is more suited for online purchasing than the latter (Dijst, Farag, & Schwanen, Citation2008). Further merchandise attributes, such as size and weight, may also drive the choice of shopping channel or the frequency of shopping activities. Conversely, intangible services are different from both search goods and experience goods, so purchasing intangible services online may be associated with different effects on travel than the purchase of goods. In summary, the impacts of online shopping on travel may differ both by shopping stage and by type of product (Cao, Citation2012; Cao, Xu, & Douma, Citation2012).

3. Search methods

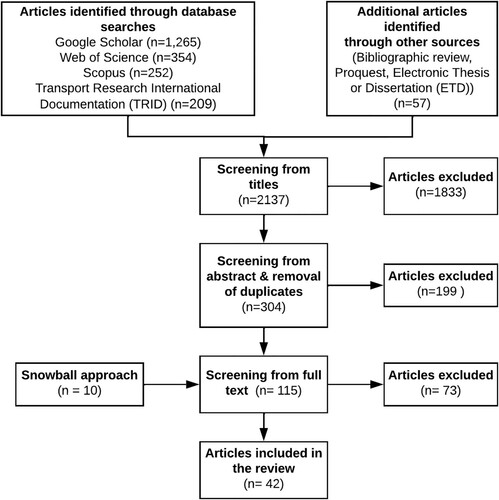

We followed the systematic review procedure suggested by Grant and Booth (Citation2009). We included original empirical research papers and excluded review papers and simulation-based studies. The literature search was performed in six databases, namely, Web of Science, Scopus, Transportation Research International Documentation (TRID), Google Scholar, and ProQuest (for dissertations). We included grey literature, such as white papers, technical reports, unpublished theses, and dissertations in the search to reduce publication bias. Additionally, we applied the snowball approach in which we added articles that either cited or were cited by an article in our list if they met our search criteria and had not yet been identified through the general search.

We applied a two-part keyword search across all databases. In the first part, we employed the terms “online shopping”, “e-commerce”, “e-tail”, “e-shopping”, and “delivery”. In the second part, we used the transport-related terms “travel”, “trip”, “transport*”, “mobility”, “activity patterns”, “in-store”, “physical store”, and “brick-and-mortar”. The two parts were connected with the Boolean operator “+”, and keywords pertaining to the same part were separated by “or”. We used “-tourism” to eliminate results related to tourism rather than local transport. We did not use the keyword “online searching” since this yielded mostly irrelevant results and, in the context of online shopping and travel research, the above keywords already cover online searching. We focused our review on studies published in English and published in 1990 or later, given that online (internet) shopping as we know it today debuted in late 1994 (Lewis, Citation1994). The search and data extraction were performed between October 13, 2019 and May 31, 2020. In Google Scholar, we only considered the first 500 results (ranked by relevance), as articles were deemed irrelevant beyond that.

In line with the topics of most published studies, only papers discussing business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce were retained, and studies of consumer-to-consumer (C2C) or business-to-business (B2B) e-commerce were excluded. We included studies that investigated at least one travel outcome, usingeither revealed or stated travel choice data. Studies focusing on online searching for product information were included if they considered at least one travel outcome. All theses and dissertations were excluded after abstract screening because they were irrelevant, or their contents were published in papers that were already included in our review. demonstrates the search procedure and results for each step.

This paper complements earlier reviews, such as those by Cao (Citation2009) and Rotem-Mindali and Weltevreden (Citation2013), and distinguishes itself through its approach and scope. Cao (Citation2009) offers a non-exhaustive, critical review of studies published between 1996 and 2009 and highlights the effect of spatial attributes and data collection methods. Rotem-Mindali and Weltevreden (Citation2013) focus on conceptual effects (i.e. not empirical results) in studies on passenger and freight transportation, which necessarily limits the depth of discussion they can devote to travel outcomes. Additionally, the review by Rotem-Mindali and Weltevreden did not include a structured overview of the studies and categorisation according to methods and findings. Our paper thus provides an up-to-date, exhaustive review of recent developments in the field, and also identifies gaps and future directions for researchers and practitioners.

4. Online shopping and travel outcomes

This section summarises the methods and study areas of the reviewed articles. We then synthesise the empirical evidence by five travel outcomes.

4.1. Overview of methods and geographical distribution

Following the search procedure described in Section 3, we found 42 empirical studies on the links between online shopping and travel behaviour (). These studies primarily used cross-sectional data, often collected by the authors of the studies. Common data analysis methods were linear regression, structural equation modelling (SEM), and logit models. The supplemental document provides a comprehensive list of the variables and their measurements considered in those studies, as well as a summary of their travel-related results. Because of the dominant cross-sectional design and different ways of measuring online shopping, travel, and controlling for other variables, the results of these studies vary greatly. Additionally, little to no causal inference was made in these studies.

Table 1. Overview of studies on online shopping and travel included in this review (ordered chronologically).

There are geographical concentrations among the 42 reviewed studies (). 11 were conducted in the US, 8 in China, 7 in the Netherlands, 1 in both the US and the Netherlands, and 5 in the UK. Together, these four countries account for 76% of all studies. Other studies were conducted in France, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Germany, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.

The study locations are important as they can be correlated with factors that are associated with online shopping, notably culture, accessibility, the breadth of online and in-store shopping options, relative price levels and delivery costs, and the availability of banking products and reliable delivery services. It is worth noting that there might be multiple effects of online shopping on travel, even for the same person or context. Researchers have largely focused on one dominant effect among the four possible effects and have not reached a consensus. We discuss the limitations and possible reasons for inconsistent findings in Section 5.

In the following sections, we synthesise the empirical evidence for the effects of online shopping on five travel outcomes. provides an overview of the evidence, most of which concerns the purchasing stage only. A small number of studies included online searching, but other stages of shopping have not been investigated.

Table 2. Evidence of the four effects by travel outcome.

4.2. Trip frequency

4.2.1. Online and in-store shopping (with a purchase transaction)

The effect of online shopping on trip frequency is the most explored area. Studies also tended to focus more narrowly on the frequency of shopping travel (and thus on complementarity and substitution) rather than analysing trip frequencies for multiple purposes and possible modification effects. Most studies measured trip frequency as the frequency of in-store shopping, share of online shopping, or number of shopping trips, using questionnaires and/or travel diaries.

The complementarity effect was found in 9 studies (excluding studies related to online searching). These studies found that online purchasing was associated with a higher frequency of in-store shopping trips (Ding & Lu, Citation2017; Edrisi & Ganjipour, Citation2017; Farag, Weltevreden et al., Citation2006; Ferrell, Citation2004; Lachapelle & Jean-Germain, Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2017; Rotem-Mindali, Citation2010; Xi, Zhen et al., Citation2020; Zhen, Cao, Mokhtarian, & Xi, Citation2016). Categorising by product types, Zhen et al. (Citation2016) found that online purchasing is positively associated with in-store shopping frequency across four product types (clothing, books, daily goods, and electronics), albeit with varying magnitudes. More frequently purchased products exhibited smaller complementarity effects.

A substitution effect of online shopping was found in 10 studies. Specifically, these studies found that online shoppers made fewer shopping trips (Bjerkan, Bjørgen, & Hjelkrem, Citation2020; Ferrell, Citation2005; Motte-Baumvol, Belton-Chevallier, & Dablanc, Citation2017; Shi, De Vos, Yang, & Witlox, Citation2019; Suel, & Polak, Citation2017; Suel, Le Vine, & Polak, Citation2015; Weltevreden, & Rietbergen, Citation2007; Xi, Cao et al., Citation2020). Most substitution for in-store shopping was by people without access to a car (Shi et al., Citation2019), shoppers who ordered large baskets, and high-income groups in the case of grocery shopping (Suel et al., Citation2015; Suel & Polak, Citation2017). One study found that the frequency of online shopping was associated with lower volition to shop in-store (Dijst et al., Citation2008). Zudhy and Wirza (Citation2015) noted that although online shopping replaces shopping travel, in-store shopping does not affect the demand for online shopping.

Many studies also found a mix of effects. Zhou and Wang (Citation2014) suggested that the relationship between online and in-store shopping is “neither pure substitution nor pure complementarity.” They found that in-store shopping suppressed the demand for online shopping, while online shopping led to more in-store shopping trips. However, the latter effect was stronger than the former. Two other studies suggested a bidirectional, positive relationship between online shopping and the frequency of shopping travel, where the number of shopping trips had a larger effect on online shopping frequency than vice versa (Etminani-Ghasrodashti & Hamidi, Citation2020; Farag et al., Citation2007). Weltevreden (Citation2007) further found evidence for cross-channel shopping, where shoppers consult price on one platform (online or in-store) before buying from the other, and found a neutrality effect. Bhat, Sivakumar, and Axhausen (Citation2003), using a longitudinal dataset with GPS tracking, found a substitution effect for 78% of the sample and complementarity for the rest. They also noted that without considering unobserved factors related to computer and phone use, the substitution effect might have been underestimated. Dias et al. (Citation2020a) described intricate complementarity and substitution effects between in-store and online shopping, while other studies found two effects within different subsets of their samples: substitution and neutrality (Calderwood & Freathy, Citation2014; Zhai, Cao, Mokhtarian, & Zhen, Citation2017), or substitution and complementarity, with the former being stronger (Tonn & Hemrick, Citation2004). Such results indicate a heterogeneity of shoppers and suggest the need for population segmentation.

Two studies found a modification effect of online shopping on overall travel behaviour, including non-shopping travel. Ding and Lu (Citation2017) found complementarity for shopping trips and substitution for leisure trips. They suggest that online shoppers tend to shop in-store frequently during weekends at the cost of leisure activities, which implies that avid shoppers may see shopping as a leisure activity. This result is consistent with findings by Ferrell (Citation2005). The single study that only found a neutrality effect is Hiselius, Rosqvist, and Adell (Citation2015).

4.2.2. Searching behaviour

Pre-purchase product searching may also affect shopping trip frequency. Respective findings have been mixed. Online searching has been found to increase both in-store (Cao et al., Citation2012; Cao, Douma, & Cleaveland, Citation2010; Douma, Wells, Horan, & Krizek, Citation2004; Edrisi, & Ganjipour, Citation2017; Farag, Schwanen, & Dijst, Citation2005, Citation2007; Xi, Zhen et al., Citation2020) and online purchasing frequency (Edrisi & Ganjipour, Citation2017; Xi, Zhen et al., Citation2020; Zudhy & Wirza, Citation2015). Results from Ding and Lu (Citation2017) suggest that the online and in-store shopping frequency positively affects the frequency of online product searching. Zhai et al. (Citation2017) found that online searching behaviours led to more in-store purchasing than vice versa. This relationship may vary by product type: Zhai, Cao, and Zhen (Citation2019) suggested that more shoppers use the same channel for searching and purchasing for experience goods than for search goods. Furthermore, shoppers are more likely to search for experience goods in-store and then purchase online; the opposite is true for search goods. This is consistent with Cao (Citation2012), who found that online searching is positively associated with online purchasing of books and media products. However, he also found a small amount of cross-channel shopping.

4.3. Travel distance

Online shopping may affect travel distance through one of the following mechanisms: (1) reducing travel distance by replacing shopping trips with online deliveries (substitution); (2) increasing travel distance by generating shopping trips that complement online purchasing, e.g. to experience a product before purchase (complementarity); and (3) changing travel distance due to changes in shopping destinations, travel modes, or routes (modification).

Evidence for changes in travel distance is still sparse and results are contradictory. Ferrell found that households did not change total travel distance, but later, using the same data but at the individual level, found that teleshoppers (including online shoppers) travelled shorter distances for shopping purposes (Ferrell, Citation2004, Citation2005). Although this study did not distinguish by mode, it is safe to assume that given the US context, most trips were made by automobile. Similar substitution findings were made by Hiselius et al. (Citation2015), where online shoppers travelled shorter distances by car but there were no differences for other modes. Both articles by Shi, Cheng et al. (Citation2020), Shi, De Vos et al. (Citation2020), using the same data, found a modification effect where users of online intangible services (e.g. eating out, visiting moving theatres) travelled longer one-way distances in general. However, they also noted that people who shopped online frequently (for tangible products) were more likely to travel shorter distances, perhaps due to time constraints.

Few studies have created typologies of shoppers. Hoogendoorn-Lanser et al. (Citation2019) identified 3 types of online shoppers with different pre-purchasing behaviours: (1) those who did not perform pre-purchasing activities, (2) those who searched for information online and offline before purchasing, and (3) those who only searched online. They found that on average, the second group had significantly greater travel distances for shopping, but the difference in travel distance for all trip purposes was insignificant. The results showed that 50% of shoppers did not change their in-store shopping behaviour due to online shopping, indicating a neutrality effect. The remaining 50% had mixed complementarity and substitution effects.

4.4. Trip chaining

The effects of online shopping on trip chaining may be best described as a modification of travel. For example, without online shopping, shoppers may chain shopping and non-shopping trips with destinations in proximity. With online shopping, some shopping trips may be eliminated, which may reduce the chaining of non-shopping trips. If visiting the non-shopping destinations is no longer convenient without the shopping destinations, destination changes may occur or trip chains may be reconfigured. This may also affect travel distance, as noted previously.

We found only a handful of studies considering trip chaining. Their results differ widely, although more evidence indicates a neutrality effect. Ding and Lu (Citation2017) found that in-store shoppers were more likely to chain shopping trips with other trip types as compared to online shoppers. Ferrell (Citation2005) found an insignificant effect of online shopping on trip chaining. Farag et al. (Citation2007) noted that time-pressured people often chain their shopping trips. Such behaviour was associated with a lower frequency of online searching and shorter duration of store visits but had no significant effect on the frequency of online purchases.

4.5. Travel mode choice

Online shopping may modify mode choice for shopping trips and other trip purposes. For example, shoppers may normally drive to stores if they must transport large or heavy items, but with online shopping, they may order such items for delivery and walk to stores for smaller items. Alternatively, online shopping may replace walking or bicycling trips, which is an unwanted outcome from a health and environmental perspective.

Despite the importance of mode choice, few studies have focused on it. Suel and Polak (Citation2017) found that grocery delivery reduced the frequency of car trips more than the frequency of walking and public transport trips. This is consistent with Bjerkan et al. (Citation2020), who found that online shoppers were more likely to walk or bike. Shi, Cheng et al. (Citation2020), studying intangible services, found the opposite: shoppers switched from walking and bicycling to car and public transport. Etminani-Ghasrodashti and Hamidi (Citation2020) showed that online shopping is negatively associated with car and public transport use for shopping travel. This suggests that online shopping may fulfil latent shopping demand from non-car owners and those lacking access to in-store shopping. This result somewhat contradicts the findings of Hjorthol (Citation2009), where online shoppers for books and media products made more car trips than non-online shoppers. Overall, there is slightly more evidence for a decrease in car use due to online shopping.

4.6. Time use: travel and activity duration

Online shopping may modify travel or activity duration. The effect of online shopping on travel time for shopping purposes is similar to the effect on trip frequency in that travel time may decrease or increase depending on whether online shopping substitutes for or generates travel. There could also be a modification effect if shoppers modify their shopping locations and travel modes.

Among the few studies focusing on time use, Douma et al. (Citation2004), Ferrell (Citation2005), and Weltevreden (Citation2007) found that people substituted time shopping online for time otherwise spent travelling to stores. Online shopping (Farag, Weltevreden et al., Citation2006) and online searching (Farag et al., Citation2007) were associated with shorter in-store shopping duration, although another study reported no significant effect (Ferrell, Citation2005). Suel, Daina, and Polak (Citation2017) found that online shopping increased duration between shopping trips but not duration between all shopping events (online and in-store). In contrast, Lachapelle and Jean-Germain (Citation2019) found that online shoppers also spent more time on shopping travel.

Online shopping may substitute for out-of-home leisure activities; it may also be considered a time-saver and a leisure activity by many people (Ferrell, Citation2005). This view was supported by some studies (Ding & Lu, Citation2017) and was contradicted by others (Lee et al., Citation2017). Some studies maintained that online shopping was more often performed for utilitarian purposes, but that it was not necessarily perceived as saving time (Lee et al., Citation2017). In any case, online shopping may make room for additional activities that could otherwise not fit in shoppers’ time schedules.

5. Limitations of the reviewed studies

An important question is which effect is dominant. We found more evidence for the substitution effect than other effects and more evidence for trip frequency than other travel outcomes. The mixed findings reviewed above show that the transportation literature has not reached a consensus on the impacts of online shopping on travel. Here, we discuss the major limitations and possible explanations for these conflicting findings.

First, as past studies relied extensively on cross-sectional data, their findings are correlational rather than causal. It is difficult to separate several effects when they occur simultaneously, especially with current survey practices and non-SEM methods. Additionally, if a cross-sectional study finds online shoppers travelling to stores more often than in-store shoppers – often interpreted as a complementarity effect – it may be because online shoppers are enthusiastic shoppers who enjoy both channels of shopping, rather than a case of online shopping inducing more shopping travel. Xi, Cao et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated this complication: they found a substitution effect when using a quasi-longitudinal dataset and a complementarity effect when using only one wave of the same dataset. The quasi-longitudinal approach, where respondents were asked about changes in their travel before and after adopting online shopping, proved to be more reliable. Other studies measuring changes in travel after online shopping also identified a substitution (Shi et al., Citation2019; Weltevreden, Citation2007) or neutral effect (Weltevreden, Citation2007) instead of complementarity. Consistent with this finding, a rare longitudinal study by Bhat et al. (Citation2003) showed a substitution effect among 78% of participants. Cao et al. (Citation2010) pointed out the possibility of obtaining different results when using different methods or model specifications on the same dataset. Without longitudinal or quasi-longitudinal data, or self-reported changes in cross-sectional surveys, researchers are unable to separate the various effects of online shopping.

Second, quantifying the modification effect is challenging due to the complexity and interconnection of various travel and activity choices. For example, shoppers may shop online and subsequently alter their trip chains, shopping destinations, travel modes, and time use. Except for quasi-longitudinal surveys, cross-sectional surveys of self-reported, retrospective behaviour and the current methods of measuring travel outcomes have limited capacity to detect such complex modification effects. It is also easy to confuse complementarity or substitution effects with a modification effect if the latter was not measured carefully, if at all.

Third, past studies define and measure online shopping and travel outcomes differently while controlling for different variables (see supplemental document). For example, some studies measured online shopping in terms of frequency or relative share of all shopping activities, or the choice of channel for individual purchases. Additionally, the time frames of measurements differed between studies: online shopping was measured for a day, a week, or a month, while travel was usually measured for a day or a week. Bhat et al. (Citation2003) found substantial variation in intra-individual shopping patterns and rhythms of shopping. These findings further support the value of long-time tracking to capture overall behavioural patterns of individuals and households. Different units of analysis (e.g. household or individual) and analytic methods further contribute to inconsistent results. For instance, using the same dataset, Ferrell found complementarity at the household level (Ferrell, Citation2004) but substitution at the individual level (Ferrell, Citation2005).

Fourth, the type of good may moderate the relationship between online shopping and travel. Only a few studies have considered multiple product types, such as clothing, media, food, and groceries (Dias et al., Citation2020a; Shi et al., Citation2019; Xi, Cao et al., Citation2020), or intangible services (Shi, Cheng et al., Citation2020; Shi, De Vos et al., Citation2020), and pointed out the variability introduced by this. Ordering groceries online may substitute for grocery shopping travel, whereas ordering clothes online may complement trips to the mall.

Geographical and cultural differences, the years when surveys were conducted, and the availability of online products and services at those points in time might also explain disparities in results. For example, online shopping might be more prevalent in countries where credit cards or digital wallets are common. Moreover, results from some older studies may no longer apply, given rapid changes in internet access and ownership of electronic devices, credit card penetration rates, and a widening range of delivery services. Over the years, more products and services have become available, and options for fast deliveries and easy returns have increased, providing customers with more choices and an ability to compare across channels. These changes may have shifted shopping behaviour, resulting in different results of studies that are many years apart. Additionally, with more choices for channels, services, and products, decision-making becomes more complex. This is a big challenge that choice modellers will continue to face when modelling online shopping and travel.

6. Research gaps and future research agenda

We identified several gaps in the literature based on the amount and strength of evidence for the four types of effects and the five travel outcomes. Our proposed agenda for future research includes improvements in research design and methods, and shifting the focus to understudied characteristics such as types of shoppers and travel outcomes. We also provide an outlook in which we consider future developments that might affect research needs, findings, and potential long-term impacts of online shopping.

6.1. Data and research design

Future studies are needed in many countries, and even within the countries that already have numerous studies, broadening the number of cities studied and adding more recent data would be valuable. To date, most studies have been concentrated in a handful of cities in the Netherlands, China, and the US, with many publications stemming from the same projects. Comparative studies between cities or regions are useful to understand the roles of the built environment or regional culture in shaping travel outcomes with e-commerce.

More longitudinal surveys would be useful, especially when combining them with long-term activity or shopping diaries. Adding interventions in the form of natural or quasi-experiments is useful to establish causal relationships between online shopping and travel. Such research designs could facilitate bidirectional analyses to account for the feedback loop between online and in-store shopping. Alternatively, asking direct questions about the effects (also known as “quasi-longitudinal” if focusing on travel behaviour before and after online shopping) would also overcome the challenges of cross-sectional data. These questions can cover substitution and modification effects, such as replacement of trips, travel mode changes, travel time, shopping duration, departure time, or destination choice for shopping and non-shopping trips. A similar approach was applied in measuring the substitution of ICT use and active transportation for car trips (Piatkowski, Krizek, & Handy, Citation2015).

Another consideration for future research is to use multiple data sources. Surveys of retail firms or shopping diaries can reduce the respondent burden, and at the same time, researchers can acquire important additional information that is often missing in self-reported data, such as total expenditures, basket sizes, and product types. However, the availability and accessibility of such data are a potential hurdle as most retail companies are unwilling to share customer data.

Similarly, the tracking time in online shopping studies may affect results. For example, travel outcomes measured in a one-day travel or activity diary may show a reduction of trips and thus suggest substitution effects of online shopping. Conversely, a one-month tracking of behaviour may reveal more complicated patterns, including modification or complementarity effects. For consistent results, travel and online shopping behaviour should also be measured within the same time frame.

6.2. Shopping characteristics, travel outcomes, and travel demand modelling

A dimension to consider in future research is the heterogeneity of shopping behaviour for different products and shopper characteristics. Future studies should particularly consider a wide range of product types (e.g. search vs. experience goods, durable vs. non-durable goods, eating out), frequency of purchasing (e.g. goods that are purchased weekly, monthly, on rare occasions), product purpose (e.g. functional vs. recreational), and stage of shopping. Dias et al. (Citation2020a) postulated that different types of deliveries (e.g. groceries, meals, other deliveries) should be considered a bundle of interdependent goods instead of being investigated separately. Additionally, the delivery mode, such as 2-hour or same-day delivery, may affect the choice of online shopping and should be considered in future research.

Typologies of online shoppers are another understudied direction. Many studies found a mix of multiple effects, especially for different subsets of their samples, which indicates the need to consider heterogeneity among shoppers. Different population segments (e.g. urban single-person households vs. suburban households) may adjust differently to online shopping. Incorporating shoppers’ psychological attributes, such as personalities and attitudes, could be a good start and has been explored. However, modelling approaches to accommodate psychological attributes have not been taken advantage of.

The modification effect and associated travel outcomes (e.g. mode choice, trip chaining, time use) deserve further investigation. Additionally, the impacts on non-shopping trip frequency and travel distance are largely absent. While activity configuration has been theoretically discussed (Couclelis, Citation2004; Dijst et al., Citation2009), empirical evidence is still lacking, with few exceptions (Weltevreden, Citation2007; Zhai et al., Citation2019). These outcomes would be important for travel demand modelling and management, specifically due to the possibility of rebound effects where shoppers reallocate time saved by reducing shopping travel to other types of travel.

Shopping decisions for many types of goods, including household items and groceries, are often made at the household level. However, past studies largely focused on the individual level. Future research should investigate these joint decisions from the household perspective.

6.3. Future outlook and policy recommendations

In the future, the prevalence of online shopping may affect the way shops are set up. For example, full stores may be converted into small urban showrooms (Xi, Cao et al., Citation2020). Suburban warehouses will likely multiply and become larger, while the number of physical stores will likely shrink, thereby potentially increasing travel times and distances for in-store shoppers. Over time, this could affect households’ location choices and drive changes in real estate markets, accessibility, and urban form (Circella & Mokhtarian, Citation2017; Janelle, Citation2012). This would result in a feedback loop in which in-store shopping becomes less appealing or otherwise less convenient, leading to a dominance of the substitution and modification effects.

Changes in store and warehouse sizes and locations, as well as B2C sales models, lead to changes in freight flows and freight transport patterns. Although freight transport is not discussed in this paper, we argue that the interconnection between urban passenger and freight transport is becoming closer due to online shopping and a trend toward some goods being delivered via private vehicles. Meanwhile, metropolitan-level travel forecasting models take freight into account separately from passenger transportation and only in rudimentary ways, if at all (Guiliano, O’Brien, Dablanc, & Holliday, Citation2013). The interactions between freight and passenger transport make it more difficult to quantify travel demand and environmental impacts of e-commerce. In demand management, practitioners face similar challenges in addressing traffic congestion caused by delivery vehicles (Holguín-Veras & Sánchez-Díaz, Citation2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased online shopping volumes, yet its long-term effects on shopping, travel, and land use remain uncertain. Couclelis (Citation2020) argued that human activities and travel will resume as usual after COVID-19, but other scholars have been more sceptic. Last but not least, although online shopping has different effects on travel, the extent to which online shopping influences the entire transport system remains unclear.

With the knowledge accumulated over the past decades and the future challenges, we can now draw several implications for transportation practice. First, it is useful to promote local and small-scale urban shops that are reachable by walking and bicycling. The availability of such options also encourages trip chaining for employees who work and shop in the same area. Second, policy makers and practitioners should encourage behavioural changes by households and businesses to promote bulk orders, shipping consolidation, and local deliveries. Third, modellers may consider reflecting urban freight transportation in their models, as well as collecting more data on online shopping in regional household travel surveys.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we reviewed 42 studies on the interactions between online shopping and travel behaviour that were published between 1990 and 2020. We classified the impacts they found based on the framework of four effect types described in the introduction. The current literature shows conflicting evidence of complementarity, substitution, modification, and neutrality, supporting all four effects. The mixed results may be attributable to differences in study area, study design, type of good, model specification, and measures.

We found more evidence suggesting that online shopping substitutes for shopping travel. Slightly fewer studies reported opposite findings, including complementarity effects. Evidence for various travel outcomes is lacking, and research reporting modification effects is largely absent. We emphasize the need to go beyond the current practice of relying on cross-sectional datasets and of focusing only on shopping travel to make inferences on these effects. Instead, longitudinal and tracking data with consideration of multiple travel outcomes and effects should be employed. Diversifying the study areas and conducting more comparative studies would also provide a better picture of the impacts of online shopping and travel. Future studies need to critically look at e-commerce and travel with an emphasis on changes in behaviour of shoppers, businesses, and logistics service providers, and on the increasing interactions between passenger and freight transport.

Research on the impacts of online shopping on travel contributes to transport, land use, and environmental modelling and management. Since the evidence to date does not overwhelmingly suggest that online shopping replaces traditional shopping travel, it is unlikely that online shopping will be an effective tool for travel demand management. Moreover, policymakers face the challenge that changes in household travel caused by e-commerce are often subtle, especially if modification effects are at play. Similarly, the intricate relationship between online shopping and urban form makes it more challenging for planners to have an impact through urban land use policy. In short, spatial interventions, such as zoning, tax incentives, and other policies to steer business location choices, will be less relevant or effective than behavioural interventions in response to the rise of e-commerce, such as promoting bulk orders, using long shipping periods for long-distance shipping, and buying goods locally. Future research on online shopping, focusing both on passenger and freight transport, would help researchers and practitioners better prepare for this future and suggest policies that reduce the negative impacts of online shopping and create more sustainable and equitable urban systems.

A limitation of our review study is the potential publication bias. Null results that found no change in in-store shopping as a result of online shopping may be less likely to be published or even highlighted in the published literature. We attempted to alleviate this bias by searching through white papers, technical reports, and theses. We believe that in the specific case of online shopping, publication bias may be less of an issue, given that a neutrality effect finding is similar to a traditional null result. Furthermore, due to the scope of our paper, we did not review the connection between online shopping and freight transport or go deeper into how individual authors measured their variables. These topics are nonetheless highly important and deserve future exploration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Bhat, C. R., Sivakumar, A., & Axhausen, K. W. (2003). An Analysis of the impact of information and communication Technologies on Non-maintenance shopping activities. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 37(10), 857–881. doi:10.1016/S0191-2615(02)00062-0

- Bjerkan, K. Y., Bjørgen, A., & Hjelkrem, O. A. (2020). E-Commerce and prevalence of Last mile practices. Transportation Research Procedia, 46, 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2020.03.193

- Calderwood, E., & Freathy, P. (2014). Consumer Mobility in the Scottish Isles: The impact of Internet Adoption upon retail travel patterns. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 59, 192–203. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2013.11.012

- Cao, X. J. (2009). E-Shopping, Spatial Attributes, and personal travel: A review of empirical studies. Transportation Research Record, 2135, 160–169. doi:10.3141/2135-19

- Cao, X. J. (2012). The Relationships between E-Shopping and Store Shopping in the Shopping Process of search goods. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 46(7), 993–1002. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2012.04.007

- Cao, X., Douma, F., & Cleaveland, F. (2010). Influence of E-shopping on shopping travel: Evidence from minnesota’s Twin cities. Transportation Research Record, 2157, 147–154. doi:10.3141/2157-18

- Cao, X. J., Xu, Z., & Douma, F. (2012). The interactions between E-shopping and traditional in-store shopping: An Application of Structural Equations model. Transportation, 39(5), 957–974. doi:10.1007/s11116-011-9376-3

- Chang, M. K., Cheung, W., & Lai, V. S. (2005). Literature derived Reference models for the adoption of online shopping. Information & Management, 42(4), 543–559. doi:10.1016/j.im.2004.02.006

- Chintagunta, P. K., Chu, J., & Cebollada, J. (2012). Quantifying transaction Costs in online/off-line grocery channel choice. Marketing Science, 31(1), 96–114. doi:10.1287/mksc.1110.0678

- Circella, G., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2017). Impacts of information and communication technology. In G. Guiliano & S. Hanson, (Eds.), The Geography of urban transportation (pp. 86–112). London: The Guildford Press.

- Couclelis, H. (1998). The New field workers. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 25(3), 321–323. doi:10.1068/b250321

- Couclelis, H. (2004). Pizza over the internet: E-commerce, the fragmentation of activity and the tyranny of the region. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(1), 41–54. doi:10.1080/0898562042000205027

- Couclelis, H. (2020). There will Be No post-COVID city. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 47(7), 1121–1123. doi:10.1177/2399808320948657

- Cramer-Flood, E., Birdsall, W., Liu, C., Mukhopadhyay, R., Shum, S., & Vahle, P. (2020). Global ecommerce 2020: Ecommerce decelerates amid global retail contraction but remains a bright spot. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.emarketer.com/content/global-ecommerce-2020.

- Dias, F. F., Lavieri, P. S., Sharda, S., Khoeini, S., Bhat, C. R., & Pendyala, R. M. (2020a). A Comparison of Online and In-Person Activity Engagement: The Case of Shopping and Eating Meals.

- Dias, F. F., Lavieri, P. S., Sharda, S., Khoeini, S., Bhat, C. R., Pendyala, R. M., … Srinivasan, K. K. (2020b). A Comparison of Online and In-Person Activity Engagement: The Case of Shopping and Eating meals. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 114, 643–656. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2020.02.023

- Dijst, M., Farag, S., & Schwanen, T. (2008). A Comparative study of attitude theory and other theoretical models for understanding travel behaviour. Environment and Planning A, 40(4), 831–847. doi:10.1068/a39151

- Dijst, M., Kwan, M.-P., & Schwanen, T. (2009). Decomposing, transforming, and contextualising (e)-shopping. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36(2), 195–203. doi:10.1068/b3602ged

- Ding, Y., & Lu, H. (2017). The interactions between online shopping and personal Activity Travel behavior: An Analysis with a GPS-based Activity Travel diary. Transportation, 44(2), 311–324. doi:10.1007/s11116-015-9639-5

- Douma, F., Wells, K., Horan, T. A., & Krizek, K. J. (2004). “ICT and Travel in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area: Enacted Patterns between Internet Use and Working and Shopping Trips.” in Proceedings Cd-Rom of the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington D.c.

- Edrisi, A., & Ganjipour, H. (2017). The Interaction between E-Shopping and Shopping Trip, Tehran. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Municipal Engineer, 170(4), 239–246. doi:10.1680/jmuen.16.00031

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., & Hamidi, S. (2020). Online shopping as a substitute or complement to In-store shopping trips in Iran? Cities, 103, 102768. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102768

- Farag, S., Krizek, K. J., & Dijst, M. (2006). E-Shopping and Its relationship with in-store shopping: Empirical evidence from the Netherlands and the USA. Transport Reviews, 26(1), 43–61. doi:10.1080/01441640500158496

- Farag, S., Schwanen, T., Dijst, M., & Faber, J. (2007). Shopping online and/or in-store? A Structural Equation Model of the Relationships between e-shopping and in-store shopping. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 41(2), 125–141. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2006.02.003

- Farag, S., Schwanen, T., & Dijst, M. (2005). Empirical investigation of online searching and buying and their relationship to shopping trips. Transportation Research Record, 1926, 242–251. doi:10.3141/1926-28

- Farag, S., Weltevreden, J., van Rietbergen, T., Dijst, M., & van Oort, F. (2006). E-Shopping in the Netherlands: Does Geography matter? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 33(1), 59–74. doi:10.1068/b31083

- Ferrell, C. E. (2004). Home-Based Teleshoppers and shopping travel: Do Teleshoppers travel less? Transportation Research Record, 1894(1), 241–248. doi:10.3141/1894-25

- Ferrell, C. E. (2005). Home-Based Teleshopping and shopping travel: Where Do people find the time? Transportation Research Record, 1926(1), 212–223. doi:10.1177/0361198105192600125

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies: A Typology of reviews. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Guiliano, G., O’Brien, T., Dablanc, L., & Holliday, K. (2013). Synthesis of Freight Research in Urban Transportation Planning.

- Hägerstrand, T. (1970). What about people in Regional science? Papers of the Regional Science Association, 24(1), 6–21. doi:10.1007/BF01936872

- Hiselius, L. W., Rosqvist, L. S., & Adell, E. (2015). Travel behaviour of online shoppers in Sweden. Transport and Telecommunication, 16(1), 21–30. doi:10.1515/ttj-2015-0003

- Hjorthol, R. J. (2009). Information searching and buying on the internet : travel-related activities ? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36, 2005. doi:10.1068/b34012t

- Holguín-Veras, J., & Sánchez-Díaz, I. (2016). Freight demand management and the potential of receiver-Led consolidation programs. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 84, 109–130. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2015.06.013

- Hoogendoorn-Lanser, S., Kalter, M.-J. O., & Schaap, N. T. W. (2019). Impact of different shopping stages on shopping-related travel behaviour: Analyses of the Netherlands Mobility Panel data. Transportation, doi:10.1007/s11116-019-09993-7

- Janelle, D. G. (2012). Space-Adjusting Technologies and the Social ecologies of place: Review and Research agenda. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 26(12), 2239–2251. doi:10.1080/13658816.2012.713958

- Lachapelle, U., & Jean-Germain, F. (2019). Personal Use of the Internet and travel: Evidence from the Canadian General Social survey’s 2010 time Use module. Travel Behaviour and Society, 14, 81–91. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2018.10.002

- Lee, R. J., Sener, I. N., Mokhtarian, P. L., & Handy, S. L. (2017). Relationships between the online and In-store shopping frequency of davis, California residents. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 100, 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.03.001

- Lewis, P. H. (1994). “Attention Shoppers: Internet Is Open.” The New York Times, August 12.

- Masanet, E., & Scott Matthews, H. (2010). Exploring environmental applications and benefits of Information and Communication technology: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 14(5), 687–691. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2010.00285.x

- McGuckin, N., & Fucci, A. (2018). 2017 National Household Travel Survey. FHWA-PL-18-019. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from http://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/885762-deDRns/.

- Mokhtarian, P. L. (1988). An empirical evaluation of the travel impacts of teleconferencing. Transportation Research Part A: General, 22(4), 283–289. doi:10.1016/0191-2607(88)90006-4

- Mokhtarian, P. L. (1990). A Typology of Relationships between Telecommunications and transportation. Transportation Research Part A: General, 24(3), 231–242. doi:10.1016/0191-2607(90)90060-J

- Mokhtarian, P. L. (2002). Telecommunications and Travel: The Case for complementarity. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 6(2), 43–57. doi:10.1162/108819802763471771

- Mokhtarian, P. L. (2004). A conceptual analysis of the Transportation impacts of B2C E-commerce. Transportation, 31(3), 257–284. doi:10.1023/B:PORT.0000025428.64128.d3

- Mokhtarian, P. L., & Meenakshisundaram, R. (1999). Beyond tele-substitution: Disaggregate longitudinal Structural Equations Modeling of communication impacts. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 7(1), 33–52. doi:10.1016/S0968-090X(99)00010-8

- Mokhtarian, P. L., Salomon, I., & Handy, S. L. (2006). The impacts of Ict on leisure activities and travel: A conceptual exploration. Transportation, 33(3), 263–289. doi:10.1007/s11116-005-2305-6

- Motte-baumvol, B., Belton-chevallier, L., & Dablanc, L. (2017). Spatial dimensions of E-shopping in France. Asian Transport Studies, 4(3), 585–600. doi:10.11175/eastsats.4.585

- Piatkowski, D. P., Krizek, K. J., & Handy, S. L. (2015). Accounting for the short term substitution effects of walking and cycling in sustainable transportation. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2(1), 32–41. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2014.07.004

- Rotem-Mindali, O. (2010). E-Tail versus retail: The effects on shopping related travel empirical evidence from Israel. Transport Policy, 17(5), 312–322. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.02.005

- Rotem-Mindali, O., & Weltevreden, J. W. J. (2013). Transport effects of E-commerce: What Can Be learned after years of research? Transportation, 40(5), 867–885. doi:10.1007/s11116-013-9457-6

- Salomon, I. (1985). Telecommunications and Travel: substitution or modified mobility? Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 19(3), 219–235.

- Salomon, I. (1986). Telecommunications and Travel relationships: A review. Transportation Research Part A: General, 20(3), 223–238. doi:10.1016/0191-2607(86)90096-8

- Salomon, I., & Koppelman, F. (1988). A framework for studying Teleshopping versus store shopping. Transportation Research Part A: General, 22(4), 247–255. doi:10.1016/0191-2607(88)90003-9

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (1987). Consumer behavior. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Shi, K., Cheng, L., De Vos, J., Yang, Y., Cao, W., & Witlox, F. (2020). How does purchasing intangible services online Influence the travel to consume these services? A focus on a Chinese context. Transportation, 1–21. doi:10.1007/s11116-020-10141-9

- Shi, K., De Vos, J., Yang, Y., Li, E., & Witlox, F. (2020). Does E-shopping for intangible services attenuate the effect of spatial attributes on travel distance and duration? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 141, 86–97. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2020.09.004

- Shi, K., De Vos, J., Yang, Y., & Witlox, F. (2019). Does E-shopping replace shopping trips? Empirical evidence from chengdu, China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 122, 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2019.01.027

- Suel, E., Daina, N., & Polak, J. W. (2017). A hazard-based approach to modelling the effects of online shopping on intershopping duration. Transportation, 45(2), 415–428. doi:10.1007/s11116-017-9838-3

- Suel, E., Le Vine, S., & Polak, J. (2015). Empirical Application of expenditure diary instrument to quantify Relationships between In-store and online grocery shopping: Case study of greater London. Transportation Research Record, 2496, 45–54. doi:10.3141/2496-06

- Suel, E., & Polak, J. W. (2017). Development of Joint models for channel, store, and travel mode choice: Grocery shopping in London. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 99, 147–162. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.03.009

- Tonn, B. E., & Hemrick, A. (2004). Impacts of the Use of E-mail and the Internet on personal trip-making behavior. Social Science Computer Review, 22(2), 270–280. doi:10.1177/0894439303262581

- Weltevreden, J. W. J. (2007). Substitution or complementarity? How the Internet changes City centre shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 14(3), 192–207. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2006.09.001

- Weltevreden, J. W. J., & Rietbergen, T. O. N. V. A. N. (2007). E-shopping versus city centre shopping: The role of perceived city centre attractiveness. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 98(1), 68–85.

- Xi, G., Cao, X., & Zhen, F. (2020). The impacts of same Day delivery online shopping on local store shopping in nanjing, China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 136, 35–47. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2020.03.030

- Xi, G., Zhen, F., Cao, X., & Xu, F. (2020). The Interaction between E-Shopping and Store Shopping: Empirical evidence from nanjing, China. Transportation Letters, 12(3), 157–165. doi:10.1080/19427867.2018.1546797

- Zhai, Q., Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P. L., & Zhen, F. (2017). The interactions between E-Shopping and Store Shopping in the Shopping Process for search goods and experience goods. Transportation, 44(5), 885–904. doi:10.1007/s11116-016-9683-9

- Zhai, Q., Cao, X. (., & Zhen, F. (2019). Relationship between online shopping and store shopping in the Shopping Process: Empirical study for search Goods and Experience Goods in nanjing, China. Transportation Research Record, 0361198119851751. doi:10.1177/0361198119851751

- Zhen, F., Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P. L., & Xi, G. (2016). Associations between online purchasing and store purchasing for four types of products in nanjing, China. Transportation Research Record, 2566(2566), 93–101. doi:10.3141/2566-10

- Zhou, Y., & Wang, X. (. (2014). Explore the relationship between online shopping and shopping trips: An Analysis with the 2009 NHTS data. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 70, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2014.09.014

- Zudhy, M., & Wirza, E. (2015). Understanding the effect of online shopping Behavior on shopping travel demand through Structural Equation modeling. Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, 11, 614–625. doi:10.11175/easts.11.614