One moment I was leading a hypermobile life, then came the pandemic. At the time of writing I have spent 15 months working only from home with zero work-related travel. This may not seem remarkable to (m)any readers in 2021 who are living through their own pandemic experience. Yet given the passage of time we may look back in wonder at this shock in global society’s history.

The age of COVID-19 has not dimmed our communication as professionals. We have moved into an online world that we now inhabit on a daily basis within which knowledge continues to be created and shared. Many have been trying to make sense of the transport implications of the pandemic. One means of doing so has been the Fireside Chat SeriesFootnote1 run by PTRC Education and Research ServicesFootnote2 in the UK: a set of ten free-to-attend panel discussion sessions online from April 2020 to May 2021. There were over 2800 individuals from across the world who registered to participate in one or more of the events and over 50 different panel speakers.

Having been involved in co-organising, chairing and writing up most of the events, I prepared and presented a freely-available full paper to provide a summary account of the Series (Lyons, Citation2021). Here I offer a flavour of the many challenges and opportunities that we face, as identified in the Fireside Chat discussions.

Early assessment of implications

With movement and travel restrictions introduced around the world, the pandemic quickly offered a reminder that when people are faced with significantly changed circumstances, they are often able to adapt their behaviour. Local authorities were empowered to introduce temporary reallocation of street space from cars to active travel with hope that the experience might result in public support for permanent reallocation. It was clear that the sector was confronting adaptive opportunities and challenges in the short, medium, and long term and that the state of flux caused by the system shock was a chance to think and act differently. It was possible to imagine a world with less car traffic as society reconfigured much activity around digital connectivity and active travel. Yet there were already many questions in people’s minds about the possibilities (explored later in the Series) with a strong sense of deep uncertainty about the future.

The death knell for public transport?

We found ourselves in the remarkable position of being told (whether rightly or wrongly was unclear) that public transport was a risk to public health. Passenger numbers fell dramatically in the face of lockdown with a (short-term) dependence upon increased public funding for services to continue running, alongside early indications that social distancing could result in a car-led recovery as it reduced capacity of, and confidence in using, public transport. The plight of public transport was also emblematic of the pandemic amplifying social inequality: for example, bus drivers were essential workers themselves and responsible for getting other essential workers, who did not have the choice of going by car, to and from their workplace – in a travelling environment where the Government was advising that public transport was to be avoided if possible. The public transport industry is now alive to the need to look beyond coping with the pandemic to also address how it can innovate to not only survive but thrive in the future, and thrive in a way that can respect and support a diverse population.

The future of roads

The juxtaposition of the UK Government’s newly published 5-year £27bn Road Investment Strategy and the framework for its Transport Decarbonisation Plan set the stage for considering what we want from our roads in the future. Following experience of road traffic levels reminiscent of the 1950s during lockdown, an easing of restrictions soon saw more familiar levels returning. There was a strong, if not universally held, view that building more roads should not be part of a new normal (the Welsh Government in June 2021 announced a suspension of all future road building plans). Instead, attention should focus on how existing roads should be used and reprioritised for different types of users, allied to catering for a diversity of societal needs. The early panic buying of toilet rolls in the pandemic was a reminder of the need for roads (and kerbsides) to support goods movement as well as people movement. Looking beyond the pandemic, equity concerns were apparent with richer people set to take advantage of electric vehicles and benefitting from infrastructure changes paid for by all taxpayers. Road user charging was seen as part of the picture for the future of roads with a possible need to treat public transport as a public service. There are stark choices ahead if the roads sector is to play its part in timely decarbonisation. A balance will need to be struck between what people currently say they want, how they react and what might be necessary to help support future society.

Goods movement in focus

The pandemic has shone a light on the (often overlooked) importance of goods movement. Rail freight benefitted from the sharp drop in passenger travel due to the pandemic and left open a question over the relative future role of road and rail as part of the need to decarbonise goods movement. With reduced activity of ports and total loss of air freight in passenger planes, it was unclear to what extent and in what (new) ways that capacity might come back into use in future. With vulnerability of supply chains exposed by the pandemic, a possible shift was expected from just-in-time and lean operations to seeking more resilience with more inventory being a natural defence against uncertainty and disruption. Addressing decarbonisation of freight will go hand in hand with the industry adapting to the consequences of the pandemic, which could include: sustained new high levels of online retail needing to be supported; changed high-streets with depleted business and reduced property values with re-purposing of buildings to residential, hospitality and logistics; and reconfiguration of streets to support active travel.

The prospects of a step change

The pandemic has helped ease walking into people’s consciousness (again) and given more people the experience of walking in their local environments, at points benefitting from reduced motor traffic levels. Yet this has also highlighted huge inequalities of experience: some places are well-planned for walking with proximity in mind while others are planned around the car. The publication in July 2020 of the UK Government’s “Gear change: a bold vision for cycling and walking” was a reminder that modal hierarchy is often overlooked, even within active travel, with walking in the shadow of cycling (for an examination of the impacts of the pandemic on cycling, see an earlier Transport Reviews Editorial [Buehler & Pucher, Citation2021]). Social distancing requirements have highlighted the gross mismatch between street space for pedestrians and people in vehicles, with the former further squeezed by the normalisation of pavement parking. Possibly motivated by nostalgia and self-interest, the vocal objections to (temporary) Low Traffic Neighbourhoods were a reminder that majority support for reprioritisation of street space needs also to be (more effectively) vocalised. With a newfound experience and love of walking, there is a chance to capitalise on the state of flux caused by the pandemic to underline walking’s future importance in the face of public health concerns and a climate emergency. Banning pavement parking surely makes sense?

Generational perspectives

The challenges and opportunities ahead, highlighted by the pandemic, were a reminder of the sometimes neglected importance of the voice of early career professionals (ECPs) in a changing world. Some of today’s ECPs emphasised how central climate change and environmental awareness were to them, with the decarbonisation agenda front of mind. Their energy, enthusiasm and advocacy were not, however, necessarily being matched by the actual progress around them in the wider sector. Moving from ambition to delivering change was not easy, with the frustration that many of the changes and solutions needed are already identified but just not being taken forwards (to the extent needed). There was, however, optimism that the catalyst of the pandemic, coupled with technological developments in connectivity and communication, may help unlock and implement old ideas in new ways. ECPs can bring a greater open-mindedness and willingness to learn from outside the sector, help introduce a more disruptive dynamic within the sector, and perhaps better connect with what might be (or become) the silent majority of the public who would welcome change towards truly more sustainable transport and liveable communities.

All models are wrong

Uncertainty about the future has likely deepened due to COVID-19. While it may have commonly appeared that our transport models exist to give us “answers” about the future, they now – more than ever – need to be understood and used rather differently. Models can be used as explorative tools to help us think (as does the process of building them). Modelling is a product of the modellers involved and the assumptions they make in building and running the models. In this respect, diversity in the makeup of the body of transport modellers is important. “All models are wrong” (an aphorism attributed to British statistician George Box) but they can usually be usefully used – provided that the right underlying philosophy is in place regarding their role in robustly planning in the face of uncertainty. Models (that are perhaps simpler and quicker) should help us examine different possible futures and how transport interventions may perform in these. Of key importance is how modelling insights are translated into information that can be clearly communicated to decision makers. The pandemic’s disruption may prove to be significant for the shaping of future modelling.

COVID-19’s role in addressing climate change

November 2021 marks what could be the most important of all UN Climate Change Conferences, COP26 in Glasgow. After several largely unheeded warnings of danger ahead, the pandemic is the equivalent to delivering perhaps the last opportunity to the captain of the Titanic to change course before disaster strikes. Has the pandemic reminded us of our capacity to adapt; or are the economy, livelihoods and people’s mental health so battered that we will crave old freedoms and resent any government looking to bring about uncomfortable, even if manageable, change? A car-led recovery seems apparent and yet sits uncomfortably with transport decarbonisation. Meanwhile public transport is on its knees, and tensions persist over what the future of (knowledge) work may look like and whether long distance travel will or should return. While there are many reasons to sense that hope may be fading regarding a mobility future changed radically for the better by the pandemic, there are also grounds for some optimism. With reference to the adage “things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could”, the UK Government’s Transport Decarbonisation Plan may catalyse change that builds momentum. Communication once again is key. It was suggested that this should focus upon regular climate crisis bulletins that inform people of steps being taken and progress being achieved, while also helping people identify real benefits for themselves and their families.

Beyond white male privilege

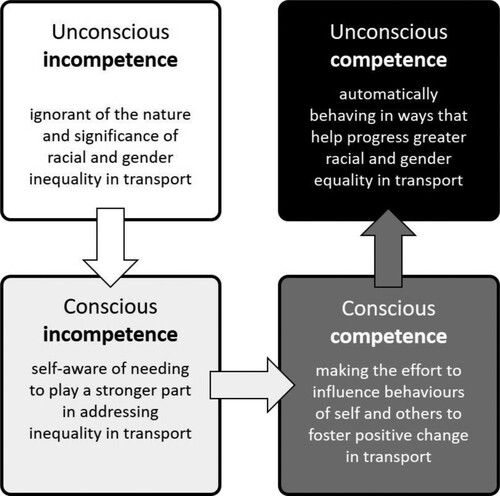

White male privilege has been a defining characteristic of the transport profession which has in turn shaped the transport system used by others – the majority of whom are not white and male. Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in the US, and protest in the wake of the killing of Sarah Everard in the UK about a society in which women do not feel safe have been stark reminders during the pandemic that we continue to fail in addressing diversity and inclusion. When we talk about a “new normal”, this must surely be an opportunity to think about a more inclusive new normal – in transport’s case, a sector that can respect and embrace diversity and in turn one that can help shape a more inclusive transport system for the future. The pandemic has highlighted inequalities and prejudice but it may also have created a state of flux and introspection. If you haven’t tested your eyesight lately when it comes to seeing race and gender issues in transport, the resources are there, you just need the time and inclination to make use of them. We need to move as individuals from unconscious incompetence regarding racial and gender inequality towards becoming unconsciously competent in how we behave to promote more inclusive transport (see ).

Figure 1 . Stages of competence in helping make transport more inclusive

Note: Inspired by https://thevoroscope.com/2021/03/22/heuristic-principles-for-scanning/.

Global perspectives

While the Fireside Chat Series has emanated from the UK, the UK represents less than one per cent of the world’s population. Nigeria and India both have populations that dwarf that of the UK and are heavily reliant on the informal economy. Debates in countries such as the UK, the US and Australia about working from home and transport technology innovation such as electric cars can seem a far cry from the masses who cannot afford any car and may not have (reliable) internet access or electricity in their homes. Built environments around the world seem to be characterised by design for the few affecting the lives of the many, with car-oriented provision at the expense of the needs of those reliant upon public transport, walking and cycling. There is often a policy-implementation gap when it comes to sustainable transport. Even in the US it is suggested that at any point in time many people, perhaps half the population, for a variety of reasons do not have the means to use a car. Issues of inequality and lack of dignity can become manifest in public protest and revolution, as has been seen in Chile before and during the pandemic – triggered by a seemingly modest increase in metro fares in Santiago. From such glimpses of life internationally there is a real sense of just how wicked the problems are that we are facing and trying to address. Restoring greater equality, greater dignity and greater opportunity to thrive in healthy, sustainable ways calls for fundamental socio-political change.

Reflections

It has been and continues to be an unprecedented time of reflection as we bear witness to a state of flux in our lives and societies. The Series has touched upon just some of the big topics that are fundamental to the socio-technical future of transport that we seek to understand and influence. The magnitude of the issues is almost overwhelming when you become absorbed in them. In this time of reckoning, they conjure up a mixture of hope and fear. For all that the motor age has done for some in society, the externalities and unintended consequences now surround us in countries around the world. Technology alone is not going to address the wicked problems of car dependence, social inequality and climate change that we confront internationally as we emerge from the pandemic. As transport professionals we face great challenges but have a tremendous opportunity to influence the current dynamics if we are upstanders and not bystanders for the need for a just and green recovery.

Notes

References

- Buehler, R., & Pucher, J. (2021). COVID-19 impacts on cycling, 2019–2020. Transport Reviews, 41(4), 393–400. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01441647.2021.1914900

- Lyons, G. (2021). Chatting round the fireside – transport tales from the pandemic. Paper presented at the 19th Annual Transport Practitioners Meeting, July 7–8. Online. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/7516241