ABSTRACT

Governments all over the world have had to implement various policy measures in order to curb the spread of COVID-19, impacting many people's lives and livelihoods. Combinations of measures targeting the transportation sector and other aspects of social life have been implemented with varying degrees of success in different countries. This paper proposes a classification of COVID-19 measures aimed at passenger mobility. We distinguish the categories “avoidance of travel”, “modal shift” and “improvement of quality”. Per category, we distinguish different types of measures and effects (social, economic and environmental). Next, we review the literature on COVID-19 measures for passenger mobility, after which we discuss the policy relevance of our findings and propose a research agenda. We conclude that broad or integral assessments of measures on all socially relevant effects are rare. Also, few studies exist to determine the effects of individual measures and deal with combinations of measures instead. Studies on social or economic effects focus on partial direct effects (e.g. turnover of the transport sector, effect of mobility measures on commuter traffic) and do not elaborate on indirect effects (e.g. changes in household expenditure, stress levels). Finally, there is a greater focus in the literature on intermediary health indicators (e.g. travel behaviour) but less on the actual spread of COVID-19 or indeed on other indirect health effects of measures (e.g. due to air pollution, more exercise, etc).

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has far-reaching consequences for the transport sector. In many cities, public transport use decreased by more than 90% during the initial stages of the first wave's lock-down (Van Oort & Cats, Citation2020). The aviation sector worldwide has also been adversely affected. Governments are under pressure to relax travel regulations, or even to tighten them, but it is not very clear what the health risks of doing so may be. Results from previous research on SARS are not easily applicable, as the characteristics of COVID-19 and SARS differ significantly in terms of the infectious period, transmissibility, clinical severity and extent of community spread (Wilder-Smith, Chiew, & Lee, Citation2020). Countries and cities have been forced to act fast in implementing travel-related measures without always fully understanding their effects on propagation risks, economic and social consequences, or on people's well-being, even though needs for such insights exist (Hale, Petherick, Phillips, & Webster, Citation2020). This paper aims to address those needs, as far as possible, by reviewing the literature on COVID-19 passenger transport measures that was available up to the end of 2020, with an update in May 2021. More specifically our paper aims to (1) provide a structure for COVID-19 transport measures and their impact on common policy goals, (2) give an overview of findings in this area and (3) synthesise the literature, discuss its policy relevance and suggest avenues for future research. We review measures worldwide, and their direct impacts (on travel and activities) and indirect impacts on other social (mental and physical health or safety), economic or environmental impacts. As many papers will still follow, and many new insights are sure to emerge in the coming years, we explicitly only provide an intermediate view. We limit ourselves to passenger mobility and focus on the modes of transport plane, car, bus, tram, metro, bicycle and walking.

Section 2 first describes the methodology, Section 3 presents the results, and finally, Section 4 summarises the main conclusions and provides reflections on the policy implications and suggestions for future research.

2 Method

We follow the methodological suggestion for literature review papers of Van Wee and Banister (Citation2016), making explicit the databases, search strategy, snowballing strategy and additional selection criteria. A literature review was performed on academic and grey literature or databases relating to transport sector COVID-19 policy measures. Both initial measures and phase-out strategies are considered relevant. Most of the literature we found concerned the period of the first wave. We did not include all references we found, but selected representative examples in each category of literature (see Section 3 and ).

Since the publication of peer-reviewed papers is slower than the evolution of COVID-19, we fill in knowledge gaps with grey literature, selecting high-quality media news outlets and the most significant in terms of their findings and in terms of their quality only. Our detailed methodology is found in appendix 3. We acknowledge there is some subjectivity in our choice of materials and that our literature list is bound to be incomplete due to the constant appearance of new publications about COVID-19. We do think our analytical framework (Appendix 1) and conceptualisation of links between measures and impacts (Appendix 2) are not sensitive to the selection of literature, but some of the empirical findings could be influenced to some extent.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Analytical framework

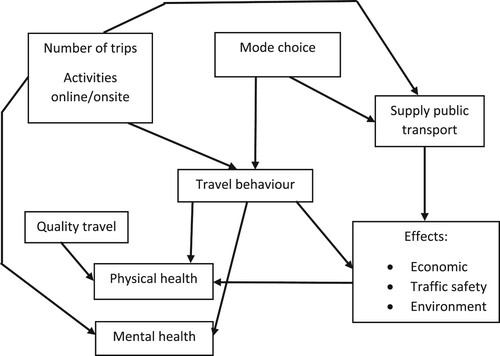

Based on the literature found and analytical thinking, we have created (Appendix 1), which provides a categorisation of measures and impacts. makes it clear that we can classify measures into those that make people travel less, those that influence the choice of transport mode, and those that aim to reduce the spread of the virus of people travelling by public transport. Effects are categorised according to the most common policy goals we found in the literature, i.e. the social goals of physical/ mental health or safety, and the goals of economic health and environmental sustainability. The effect of some measures in relation to these goals can be positive or negative. For example, some people may find working from home more pleasant than working on site (e.g. because they spend less time travelling), but others may find it unpleasant (e.g. because they miss out on social contacts, or are less able to work undisturbed at home). We organise Section 3 according to . Appendix 2 further conceptualises the intermediary links between the measures and impacts.

3.2 Overview

In total, 280 grey literature sources and 258 academic papers about measures or impacts of COVID-19 measures were collected and considered relevant. Over half (57%) of all papers found related to social impacts, whilst economic and environmental impacts made up around 17% each. Around 5% of papers covered various impacts (impacts in more than one category) and the remaining papers (6) were about measures themselves.

Papers on social impacts were focused largely on the direct impacts of COVID-19 (transport) measures on travel behaviour or mobility patterns (45%) or indirect impacts such as impacts on physical health (22%) or psychological and mental health impacts (13%). Other topics covered included impacts on road safety and accidents, impacts on perceptions or risk perceptions or impacts on health-related behaviours. Papers on economic impacts covered a greater diversity of topics, with employment, productivity and costs being dominant (direct) impacts. We hardly found literature on indirect economic impacts, such as those related to job and residential locations. The majority of papers on environmental impacts related to impacts on air quality. Other topics covered included impacts on GHG emissions, noise pollution or water quality.

205 papers were focused on a particular country or region. Of these, 37% were from Asia, 28% were from Europe, 18% from U.S.A./Canada, 6% from Africa, 5% from South America and the remainder from Australia, New Zealand and the Middle East. We limited the number of references because of the journal's guidelines. A full list of references is available at request via the first author of this paper.

3.3 Results: common policy goals and associated strategies and measures

3.3.1 Measures that avoid use of shared or public transport

Although studies of the spread of COVID-19 in public transport vary widely in their assumptions, virus dynamics, demand or operational characteristics, many show that the virus is transmissible in public transport to some degree (Hörcher, Singh, & Graham, Citation2020). By reducing the contact and exposure of customers within public or shared transport it is hoped that the spread of the virus can be curtailed. “Avoid” measures should reduce the need or possibility to travel in the first place, by reducing the demand for, or supply of transport and may be voluntary or policy induced. By the end of March 2020, more than a hundred countries had implemented some combination of these measures (Parady, Taniguchi, & Takami, Citation2020). Other shared mobility services (ride-hailing, bikesharing, carsharing and micromobility) and private cars may also be subject to measures (ACAPS, Citation2020; Hale et al., Citation2020).

3.3.1.1. Required closure of non-essential services and large gatherings

Rationale: Demand-side “avoid” measures aim for a direct effect on travel or activities through the required closing or reduction of businesses, work places or non-essential services. Supply-side measures have the direct effect of reducing the supply of public transport, e.g. by suspension.

Direct effects: The closure of non-essential services and restrictions on gatherings overall achieved the desired effect of reducing travel to non-essential destinations. By May 2020, retail and recreation trips decreased by 40–65% from a January baseline across all regions, although trips to retail and recreation fell less in low-income countries (Medimorec, Enriquez, Hosek, & Peet, Citation2020). Latin American/Caribbean countries saw the biggest decrease of 66% on average. In Italy, mobility trends associated with tourism, retail, and services reduced by over 90% during the first lockdown beginning March 2020 (Bonaccorsi et al., Citation2020). In the U.S.A., commuting in major cities had halved by end of March (Klein et al., Citation2020). Similar trends were observed in Japan (Morita, Nakamura, & Hayashi, Citation2020). Some governments deliberately reduced or even suspended public transport: in China, intra-city public transport was suspended in 136 cities and inter-city travel was prohibited by 219 cities (Tian et al., Citation2020).

Social, economic or environmental impacts: In terms of reducing the spread of the virus, the most effective measures (based on a study of 175 countries) have been found to be those that reduced contacts, e.g. cancelling of public events and restrictions on private gatherings, or school and workplace closures, each causing decreases of 12% or greater in the number of daily infections six weeks after introduction (Askitas, Tatsiramos, & Verheyden, Citation2021). A U.S.A. study (Courtemanche, Garuccio, Le, Pinkston, & Yelowitz, Citation2020) found shelter-in-place orders and the closure of public places to be most effective, with shelter-in-place orders leading to a ∼9% reduction of the COVID-19 case growth rate after 3 weeks. However, Li et al. (Citation2021) found that in the U.S.A., while stay-at-home orders and workplace closures were the most effective initially, effectiveness of all measures decreased over time as people stopped complying.

Cancelling leisure activities or workplace trips may create social isolation, stress, boredom and negatively affect subjective well-being and mental health (Zhang, Wang, Rauch, & Wei, Citation2020). People with disabilities have been particularly affected by a reduced access to public transport (Cochran, Citation2020). People who had to stop working completely were the worst affected (Zhang et al., Citation2020). In Germany, average life satisfaction decreased in the early stages of the pandemic (Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2020). In Ireland, well-being increased due to spending time outdoors, gardening or taking care of children whereas activities like remote meetings or home-schooling children were particularly stressful (Lades, Laffan, Daly, & Delaney, Citation2020). Student's experiences of the closure of schools and universities have not been positive. In the U.S.A., 13% of students will have a delayed graduation, 40% have lost a job, internship, or a job offer, and 29% expect to earn less at age 35. Lower income students are worse affected and are 55% more likely to have delayed graduation (Aucejo, French, Paola, Araya, & Zafar, Citation2020).

Closure of schools, businesses and services has a detrimental effect on the economy, however, few studies have examined indirect economic impacts of these measures. Obviously, the transport sector has been adversely affected, with many transit agencies facing revenue deficits (Hu & Chen, Citation2021). Transport workers who rely on daily wages to survive have suffered most due to suspension of transport services (e.g. Indonesia, Philippines) (Ecomobility.org, Citation2020a). Preliminary evidence suggests that consumer spending for over 1 million small U.S. business may be reduced by 40%. School closures in the U.S. could be costing the economy up to £1.2 billion per week (Ahammer, Halla, & Lackner, Citation2020). By May in the U.S. active business owners fell 15% with the highest losses sustained by African-American, Latin, Asian and immigrant businesses (Fairlie, Citation2020). Not all countries may have been affected equally. In the Netherlands, one early survey revealed that only 1% of respondents lost their job or went bankrupt (de Haas, Faber, & Hamersma, Citation2020). Some services have benefited such as Taiwanese small farmers who benefited over agribusinesses when online shoppers increased the demand for grains, fresh fruit and vegetables (Chang & Meyerhoefer, Citation2020).

The environmental effects of closing non-essential services have not been studied explicitly, however environmental impacts of combined COVID-19 measures are described in Section 3.3.4.

3.3.1.2. Requests to work from home where possible

Rationale: Measures that reduce the need to travel to work prevent contact in the workplace or transportation especially during peak times (OECD, Citation2020a). Most governments have requested that people work from home where possible. Otherwise, companies may be requested to allow flexible working hours or staggered working shifts or opening hours to avoid crowding for commuters.

Direct effects: A study of 100 countries found that 40–60% of workers were working from home during the period March–May 2020 (Shibayama, Sandholzer, Laa, & Brezina, Citation2021). By mid-April 2020, in all regions, trips to workplaces decreased by 40%, with a particularly high decrease in high-income countries, probably due to the higher availability of teleworking arrangements (Medimorec et al., Citation2020) and possibly due to the higher share of office jobs in these countries. In Asia, telework was a major factor in preventing contagion in densely populated cities like Hong Kong, Seoul and Tokyo (OECD, Citation2020a). By April, 37% of workers in Europe were teleworking (Eurofound, Citation2020). A survey of 2000 global organisations showed that 47% of companies managed to transition to remote work in around two days and the majority in less than a week. The main challenges with telework related to setting up IT hardware, infrastructure and security (Walters, Citation2020). As teleworking is not possible for everyone, in Rio de Janeiro industry and service sectors staggered their working hours (OECD, Citation2020a) and in France, regions agreed with businesses to stagger arrival and departure times in businesses (OECD, Citation2020a).

Social, economic and environmental impacts: Among less educated, lower-income, and people of colour (e.g. in the U.S.A.), use of public transport reduced less due to the nature of their profession and as a result, these groups may have suffered higher death rates (Hu & Chen, Citation2021).

Surveys show a majority of workers view remote working positively, due to factors like flexible hours, no need to commute and being at home (Hensher, Wei, Beck, & Balbontin, Citation2021; IBM, Citation2020; Walters, Citation2020), although 38% of workers globally missed physical interaction (Walters, Citation2020). Negatively perceived factors of working from home include lack of distinction between work and home life, poor eating habits, loss of self-discipline, absence of IT department, longer working hours and frequent video calls (Statista, Citation2020), disruption from family members, less effective collaboration and lack of focus (Hensher et al., Citation2021).

Regarding worker productivity with teleworking, a global survey carried out in April/May 2020 found 23% of professionals reported lower productivity, 32% reported no change and 45% reported increased productivity, while 78% of employers observed equal or increased productivity during the lockdown. Increased productivity has been attributed to no commute or better focus (Walters, Citation2020). In Australia, research shows that after 2 waves of the pandemic, attitudes toward working from home are generally positive and productivity is relatively high, with many workers expressing a desire, supported by employers, to work from home in the future (Beck, Hensher, & Wei, Citation2020). In the U.S.A., a survey found that a majority of firms did not have productivity loss due to remote working (Bartik, Cullen, Glaeser, Luca, & Stanton, Citation2020). Bin, Andruetto, Susilo, and Pernestål (Citation2021) carry out a study on the adoption of digitised alternatives for various activities (e.g. entertainment) and find that long term adoption of online alternatives are correlated with personality and socio-demographic group.

A positive side-effect of working from home (e.g. in Australia) has been reduced congestion, which may continue after the pandemic, since workers are keen to work from home one or two days a week if they can (Hensher & Beck, Citation2020). After three months of restrictions in Australia, there was a large reduction (54%) in annual time costs for commuters much of which was associated with reduced congestion (Hensher et al., Citation2021). Otherwise in general, little study has been done on the environmental impacts of teleworking during the pandemic. The indirect or longer term economic impacts of the shift to teleworking (e.g. location decisions, changing office set-ups) during the COVID-19 pandemic have hardly been studied either and are thus an interesting avenue for future research.

3.3.1.3. Domestic travel restrictions

Rationale: travel restrictions aim to restrict mobility and range from giving advice against non-essential travel to banning all non-essential travel (e.g. via suspension or drastic limitation of public transport). Travel restrictions may be local or national (Dunford et al., Citation2020). Essential travel may include essential delivery transport, the transport of medical personnel, retail and wholesale employees, employees of strategic infrastructures (water, energy, transport, etc.), security personnel, etc. (OECD, Citation2020a). Restrictions may be enforced by requests for compliance, or more stringently by introducing fines or penalties for noncompliance, or requiring proof of permission to travel (Hale et al., Citation2020).

Direct effects: Travel restrictions or bans are considered most effective when combined with other measures like closing entertainment venues, and banning public gatherings (Chinazzi et al., Citation2020). Stringency and timing have varied significantly between countries (Hale et al., Citation2020). Countries have tended to increase the stringency of their measures as their situation worsened (Hussain, Citation2020). In the early stages of the pandemic (Feb-April), some Asian countries never moved beyond national recommendations (e.g. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Macau, Singapore, Hong Kong), which most people adhered to, whilst other countries went straight into local or national lockdowns with full travel bans (China, Vietnam, Iran) (Dunford et al., Citation2020). In Europe, several countries, like France, Italy or Spain, implemented full national lockdowns early on, limiting all non-essential travel, whereas others (e.g. Sweden or the Netherlands) only made requests to restrict movement. In the Netherlands, for example, people were asked to stay home but they could move freely while maintaining 1.5 m distance from each other. Offenders were fined 390€ (de Haas et al., Citation2020). By the end of March, almost every European country had implemented a full or partial lockdown, apart from Sweden, Iceland, Latvia and Hungary.

Social, economic or environmental impacts: Although multiple recent studies propose that mobility restrictions reduce contagion, there is no clear evidence that suspending mass transport reduces spread (Musselwhite et al., Citation2020). Evidence from France and Japan suggests no higher risk in public transport than anywhere else, once people wear masks and follow health guidelines and social distancing (O’Sullivan, Citation2020). In an Italian study, Cartenì, Di Francesco, and Martino, (Citation2021) found a correlation between the transport accessibility of an area and the number of COVID-19 cases and suggest that indiscriminate lockdowns for all areas may be inappropriate and that lockdowns should be applied based on the transport accessibility of an area.

Nonetheless, travel restrictions may have contributed to saving lives in many countries. In the U.S.A. California's stay at home orders may have reduced COVID-19 cases by 125.5–219.7 per 100,000 population between March and April (Friedson, McNichols, Sabia, & Dave, Citation2020). COVID-19 cases fell by 44% in 40 states three weeks after initial stay at home orders (Dhaval, Friedson, Matsuzawa, & Sabia, Citation2020). In contrast, an estimated 400 jobs were lost per life saved during this period (Friedson et al., Citation2020). In India, on the other hand, travel restrictions left millions of migrant workers without the means to earn money, and as a result, causing a mass exodus from major cities to other Indian states. It has been estimated that this could have a significant impact on the number of active COVID-19 cases in these states (Maji, Choudhari, & Sushma, Citation2020).

Avoid measures have similar social impacts. A Chinese study showed that lack of social interaction due to remote work or travel restrictions, and limitations of exercise during lockdowns negatively impacted life satisfaction and distress levels (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Dutch surveys showed that around 40% of people were unhappy with less social interaction (de Haas et al., Citation2020). Travel restrictions may also cause increased economic inequality and cut people off from vital services. In Italy, a full suspension of public transport impacted lower income regions most adversely (Bonaccorsi et al., Citation2020). Developing countries have suffered higher human costs due to hunger, starvation, denial of medical care or suicide (Elsa, Citation2020). In several African countries, COVID-19 measures have been proven unsuitable (Tinto, Citation2020), for instance, curfews, on top of transport restrictions caused crowding as citizens rush to get home in time, increasing the risk of infection (Vanguard News Nigeria, Citation2020). Many African nations are dependent on donor aid so may not be able to provide financial support or testing services. People may face the dilemma of starving or getting sick. In Nigeria, travel restrictions prevented households from fetching water or soap for basic hygiene purposes, exacerbating health risks (Adegboyega, Citation2020). In Kenya, in one survey on the impact of COVID-19 measures, 86% of respondents reported a total or partial loss of income and 74% reported eating less or skipping meals due to having too little money for food (Quaife et al., Citation2020).

The environmental effects of domestic travel restrictions have not been studied explicitly, however environmental impacts of combined COVID-19 measures, including mobility restrictions, are described in Section 3.3.4.

3.3.1.4 International travel restrictions

Rationale: A recent study shows that in Europe, the COVID-19 outbreak closely followed global mobility patterns of air passenger travel (Linka, Peirlinck, Sahli Costabal, & Kuhl, Citation2020). Various measures such as flight suspensions, partial or full border closures, prohibiting or quarantining travellers from certain regions or banning non-citizens from entering have been implemented around the world.

Direct effects: When the virus first appeared, several countries brought in initial restrictions on flights from China, or required visitors from at-risk areas to be quarantined on arrival. COVID-19 quickly spread across several borders, which prompted measures that restrict movements between countries. The WHO, for example, issued recommendations for such measures (WHO, Citation2020). As well as this, measures have been put in place for detection and management of suspected cases at points of entry, including ports, airports and ground crossings. In Europe, countries implemented border closure at different times and to different degrees. Some applied measures like screening and 14-day quarantines for passengers from high-risk regions early on, whilst others waited and opted for stricter measures such as partial border closures or banning non-residents or travellers from high-risk regions (Sabat et al., Citation2020). Airline strategic responses in Europe can be grouped into retrenchment, persevering, innovating, exit and resume. Retrenchment, measures that aim to substantially reducing cost and minimise cash burn, were a major immediate response strategy, and persevering has also been important for most airlines, with the help of government subsidies. Some airlines innovated by e.g. switching to cargo rather than passenger travel whilst others failed or waited until signs of easing restrictions (Albers & Rundshagen, Citation2020).

Social, economic and environmental impacts: Due to flight suspensions, international and domestic flights fell to an all-time low around May 2020, with a subsequent recovery in domestic flights (Sun, Wandelt, & Zhang, Citation2021a). In the U.S.A., domestic air traffic fell by 71% in May 2020, in spite of government financial support under the CARES act (Hotle & Mumbower, Citation2021).

While the success of some countries, e.g. New Zealand or Taiwan at reducing COVID deaths has been attributed in part to early border controls/closure (Summers et al., Citation2020), the effectiveness of international travel controls at curtailing the spread of the virus has been criticised since many countries did not implement them soon enough, instead waiting until the virus had spread domestically (Sun et al., Citation2021a). In July, the WHO warned that a one-size-fits all model limiting international travel does not makes sense because outbreaks develop differently in different countries. The EU has now implemented a traffic light system to guide countries, in an attempt to make international travel restrictions “fairer” (European Union, Citation2021).

The longer term impact on aviation is unclear due to uncertainties in passenger prediction and there is much discussion on how tele-activities, improvements in rail networks or new technologies and policies may influence the sector (Sun et al., Citation2021a). In the early stages of the pandemic, the impact of travel restrictions was larger for the international air travel market, since domestic markets kept some level of activity. However, experts predict that business-related travel will be adversely impacted due to increased teleworking skills, event cancellation and reduced marketing and travel budgets (Suau-Sanchez, Voltes-Dorta, & Cugueró-Escofet, Citation2020). In June, the ICAO estimated the impact of COVID-19 on world passenger air traffic (combined domestic and international) to amount to a loss of USD400 billion gross operating revenues (ICAO, Citation2020) and found that in 2020, capacity was likely to be reduced by around 50%. Airline labour, especially in major airlines, is likely to bear the brunt of the decline and recovery could be in the region of four and six years (Sobieralski, Citation2020). On the other hand, the rail sector is likely to benefit from reduced air travel (Sánchez et al., Citation2020). A UBS report has found that the COVID-19 pandemic could accelerate the shift of passengers from air to rail, post-lockdown, with greater than expected growth in the rail industry over the next ten years (Burroughs, Citation2020).

Few studies have been carried out in relation to the social or environmental impact of international travel restrictions by themselves. In Australia at time of writing, the borders are still closed and international flights are limited. This is expected to lead to a 50% reduction in international students with a subsequent loss of 57% annual revenue from international education (Munawar, Khan, Qadir, Kouzani, & Mahmud, Citation2021).

Since the aviation industry contributes around 3% of global GHG emissions, we can assume that these emissions have dropped significantly for the time being, however, positive effects are likely to be short-lived (Le Quéré et al., Citation2020).

3.3.2 Measures to shift passengers to other modes

Rationale: Shifting passengers away from public or shared transport modes may reduce contagion. In large cities like London, New York, Paris and Tokyo, it is estimated that even with an over 30% reduction in trips due to telework or mode changes, 2–3 million trips per day must still be taken (OECD, Citation2020b), by other means than cars as cities cannot cope with increases in mixed traffic modes (Veryard & Perkins, Citation2018). Micromobility, especially individual modes, reduces risk of contagion, and takes up less space than motorised transportation in cities, thus avoiding traffic congestion. Bikeways could have a person throughput of 7500 per hour and footpaths 9000 per hour (NACTO, Citation2020a).

Direct effects: Various measures have been implemented around the world to encourage mode changes. In a review of case studies worldwide, Nikitas, Tsigdinos, Karolemeas, Kourmpa, and Bakogiannis (Citation2021) identify policies that encourage biking during the pandemic, including infrastructure-based (cycling infrastructure, bike sharing, tactical urbanism, regeneration of roads) or measures-based (traffic calming, car bans, speed limits, one-way streets, e-bike subsidies). Other reported measures include filtering or banning non-local traffic, shared streets, fast-tracking planned walking or biking facilities, providing bike parking or bike-sharing facilities, subsidies or funding schemes for bike purchase or repair, one-way walking, adjusting signal timing at crossings, removing parking at recreational areas (Pedbikeinfo, Citation2020).

Social, economic and environmental impacts: In general, more bike trips have been taken over longer distances for commuting or leisure purposes (Nikitas et al., Citation2021). Changes in cycling were observed between 2019 and 2020 by (Buehler & Pucher, Citation2021) with the EU seeing a growth of 8% on average, the U.S.A. of 16%.

Major cities like New York or Philadelphia have already experienced shifts to active transport modes, with increases in cycling especially (IEA, Citation2020). Over 150 cities (e.g. London, Bogota, Barcelona, Paris or Milan) have planned to promote active transport via temporary or dedicated cycling and walking infrastructure or widened footpaths (OECD, Citation2020b). In New York, there was a modal shift from subway to bike sharing (Teixeira & Lopes, Citation2020). In April 2020, 20% of regular U.S.A. public transport users said they would stop using it and 28% said they will use it less often after the pandemic (IBM, Citation2020). However, changes to more active modes have not always been welcomed by communities. For instance, in the U.K., villagers were unhappy with cyclists passing through and potentially spreading the virus (Sherwood, Citation2020).

Reallocation of street space has posed challenges. Pavements in many cities are not wide enough to accommodate social distancing. Making space for pedestrians on roadways requires reducing traffic speeds to 30 km/h (OECD, Citation2020b). Traffic priority rules may have to be changed to avoid crowding at junctions (OECD, Citation2020b). Cycling injuries increased in London due to an increase in cycling (Mumtaz, Cymerman, & Komath, Citation2021).

Bike sales increased to the point that finding a bike became difficult in the U.K. due to shops going out of stock (Sherwood, Citation2020). In the U.S.A., leisure bike sales increased 121% and electric bikes 85%. Bike service and repairs has also profited (Statista, Citation2020). However, in some countries shared mobility was not considered as an essential service and forbidden. Some operators, therefore, suffered huge losses (OECD, Citation2020b).

Although it is still too early to fully determine the social impacts of COVID-19 shift measures from the literature, previous research shows that investments in active transport pay off by reducing traffic congestion, in some cases accidents and associated costs as well as CO2 emissions (FLOW, Citation2018). “Shift” measures may actually reduce bus travel time by up to 40%, reduce car traffic and save millions of hours in car travel time (FLOW, Citation2018). Health benefits from promoting active transport could save public health budgets billions (OECD, Citation2020b). For example, if every Londoner walked or cycled for 20 minutes a day, the U.K.'s public health system could save GBP 1.7 billion in treatment costs over the next 25 years (Mayor of London, Citation2020b).

In spite of the various measures to encourage active or micromobility modes, many people have been turning to private cars (Rivoli, Citation2020) especially in cities where cars were already the more dominant mode. In many major cities (e.g. Berlin, Los Angeles, Chicago, Auckland and Sydney), car usage was almost back to pre-COVID levels by June (Lawrie & Stone, Citation2020). A March survey in China suggested that 66% of people preferred to drive after the pandemic, compared to 24% before, with more consumers likely to buy a car in the future (Chui, Citation2020). An increase in unsafe driving behaviour was observed in some countries e.g. Greece and Saudi Arabia (Katrakazas, Michelaraki, Sekadakis, & Yannis, Citation2020) but due to reduced mobility, overall traffic accidents reduced in e.g. Spain (Saladié, Bustamante, & Gutiérrez, Citation2020) and U.S.A. (Sutherland, McKenney, & Elkbuli, Citation2020).

3.3.3 Measures to improve quality and safety of public and shared transport

Rationale: Improving the quality and safety of public and shared transport maintains options to travel, and with important advantages for the economy and those who need transport urgently. Shared and public transport have the highest perceived risk profiles of all modes (Richert, Martin, & Schrader, Citation2020), but improving their quality helps improve perceptions and encourage its continued use. Tirachini and Cats (Citation2020) review measures such as physical distancing, use of facemasks and hygiene, sanitisation and ventilation. Gkiotsalitis and Cats (Citation2020) identify further measures as part of strategic planning (e.g. station skipping), tactical planning (e.g. reduced frequency or timetable changes) or operational planning (e.g. crowd management, vehicle holding and speed control). Here we discuss common quality improvement measures of implementing social distancing to avoid crowding, improving hygiene and managing demand.

3.3.3.1. Additional space/social distancing

Rationale: To reduce viral spread, the WHO recommends keeping at least 1 m distance or using facemasks, which can help reduce the distance required (Chen, Citation2020).

Direct effects: Kamga and Eickemeyer (Citation2021) reviewed social distancing measures used in public transport in the U.S.A. and Canada and found that these related to preventing crowding and limiting numbers of people at stations; physical distancing on platforms; employee protection; rear boarding; partition of drivers cabin; tape line behind driver; staggered seating; limiting capacity or additional vehicles; longer trains. Countries vary in the limits they have placed on public transport capacity, e.g. Columbia began at 35%, the U.K. at 10% (Ardila-Gomez, Citation2020). In China, buses operate at 50% capacity or less and on-board cameras are used to enforce this rule (Wong, Citation2020). Measures taken in the aviation industry include barriers between boarding gates, blocking middle seats or forbidding carry-on luggage into the cabin (Benita, Citation2021).

3.3.3.2. Hygiene and health measures

Rationale: Tirachini and Cats (Citation2020) find a consensus on the effectiveness of using facemasks properly and hygiene, sanitisation and ventilation for stopping viral spread in public transport. Health screening of passengers and staff, e.g. via thermal imaging or temperature identifies potential infections or helps tracking and tracing (IATA, Citation2020). Frontline interaction measures include automatic opening of all doors at any station to prevent direct contact (OECD, Citation2020b), rear-door boarding or no physical fare collection (NACTO, Citation2020b).

Direct effects: Across Asia, measures such as providing hand sanitiser in public transport and stations, sanitising vehicles after each trip, enhanced air filters and ventilation, UV lights for disinfection and the use of cleaning robots have been implemented (Wong, Citation2020). In Seoul, if a potential COVID-19 carrier breaches self-isolation, location history is tracked and a sterilisation team is deployed to perform additional sterilisation (Mediahub Seoul, Citation2020). Some transit agencies have reduced front-line interactions by e.g. banning non-essential access to buildings and/or shutting down ticket kiosks or customer service facilities (Transit, Citation2020).

In Korea, the ministry of transport used an existing smart cities platform to help automate contact tracing by combining police data and data from telecommunications and credit card companies, resulting in a system that could trace an individual in around 10 minutes. Although the platform deals with sensitive private information, the policy of sharing contact tracing information had already been previously legislated and debated years before COVID-19 (Lee & Lee, Citation2020).

3.3.3.3. Capacity management for public transport

Rationale: Capacity management measures help to maintain a particular capacity in public transport vehicles and stations. E.g. Increasing public transport frequency makes up for reduced capacity, reduces queues, waiting times and overcrowding (OECD, Citation2020b). Tirachini & Cats (Citation2020) suggest various options such as on-demand services; reserved slot booking; travel permits for specific groups; pricing management or peak spreading. Hörcher et al. (Citation2020) also summarise five management methods: (i) inflow control with queueing, (ii) time and space-dependent pricing, (iii) capacity reservation with advance booking, (iv) slot auctioning and (v) tradeable travel permit schemes. Due to individual limitations, these are likely to be more successful if several are implemented simultaneously.

Direct effects: Capacity management measures have been implemented in several cities. In San Francisco, operators reduced service to meet lowered demand, prioritising routes for essential works (NACTO, Citation2020b). Hamburg is monitoring the load factor of journeys and adjusting scheduled services to suit the passenger volume (Hamburg, Citation2020). In Beijing, a public transport booking and appointments app provides staggered access to public transport stations (Salo, Citation2020). In Fukuoka (Japan) riders get information on subway congestion levels by time slot on the city's website (Richards et al., Citation2020), and in Catalonia, an app integrated into the real-time passenger information system provides information about crowding in buses (Polis Network, Citation2020). Increasing public transport frequency has been implemented in New York, Florida, and Houston (NACTO, Citation2020b). Popup bus lanes have also been implemented in order to meet demand and reduce congestion. In New York, 20 new miles of emergency bus lanes were added (Carlson, Citation2020) and in Scotland, GBP19 million has been allocated to popup bus lanes (Bol, Citation2020).

3.3.3.4. Social, economic and environmental impacts of improved measures

So far, few academic studies have examined the social, economic or environmental impacts of measures to improve the safety and quality of public transport. Tirachini and Cats (Citation2020) note the adverse financial impact on public transport operators worldwide, in spite of government support, from increased costs of hygiene measures, losses of revenue from reduced capacity and rear door boarding and decreased demand. They also note that maintaining high-quality public transport is a matter of social equity since many low-income groups will continue to use it during the pandemic.

Limits on capacity and physical distancing have been difficult to implement in public transport in many countries. Social distancing in Mumbai's suburban railway system, with the highest passenger density in the world has stretched bus services beyond capacity (Aklekar, Citation2020). In London, social distancing was described as “impossible” in the period following the lockdown, since keeping 2 metres distance in the bus or tube was very difficult due to the amount of people and few people wore masks. Increasing frequency was hindered due to staff being ill or needing to self-isolate or shield (BBC News, Citation2020). Due to decreased capacity (and demand), transport providers are losing huge amounts of revenue. San Francisco's BART system, for instance, lost 88% of its ridership and needed emergency funding (Welle & Avelleda, Citation2020). In countries where government support for transport operators is low, implementing social distancing in vehicles has driven up the price of tickets for those who must continue to travel to work, putting their livelihoods at risk or stranding them. For example, in Abuja, Nigeria (Ripples Nigeria, Citation2020).

In terms of capacity management, ensuring predictable speeds and traffic conditions is challenging, especially in cities with high congestion (Ardila-Gomez, Citation2020). Some countries may not have additional vehicle capacity, e.g. Lima, Peru (Ecomobility.org, Citation2020b).

It is still unclear whether some hygiene measures in transport provide adequate protection against COVID-19 and whether they are sustainable over time because of manpower and logistical issues (Musselwhite et al., Citation2020) and their potential to create bacterial resistance (Yam, Citation2020). Furthermore, compliance with rules such as mandatory facemasks, or acceptance of surveillance varies between countries. In Korea, for example, people are accustomed to wearing masks, are not as concerned with individual freedom or privacy, compared to other countries (Sonn, Citation2020). People may not always follow advice for wearing facemasks, e.g. in Ghana (Dzisi & Dei, Citation2020).

3.3.4 Impacts of combined measures

Since measures are often introduced in combination (Parady et al., Citation2020), or in rapid succession (IMF, Citation2020), the contribution of individual measures is often not easy to determine. For example, for public transport, the combination of closing activities or workplaces, restrictions on public transport itself and the perceived risk of travellers even when restrictions are lifted or voluntary reductions have impacted ridership (Hörcher et al., Citation2020; IMF, Citation2020). While literature on economic impacts shows diverse effects without a clear pattern as yet, for social impacts, a large portion of the literature we found concerned impacts on physical health (including viral spread), psychological or mental health and impacts on travel behaviour or mobility patterns.

Many studies investigate the direct impact of combined COVID-19 measures on mobility behaviours in different countries (e.g. Hu & Chen, Citation2021; Shibayama et al., Citation2021). However, in terms of the effectiveness of individual measures, very little literature is available. The few studies that exist on psychological health impacts of combined COVID-19 measures, e.g. (Zhang et al., Citation2020) suggest that a lack of social interaction negatively impacts mental health or well-being impacts. With regard to physical health, various studies, e.g. (Chinazzi et al., Citation2020; Tian et al., Citation2020) have investigated the impact of social distancing or lockdown measures on the spread of the virus or reproduction number, and there is a general consensus that such measures have been effective (Hörcher et al., Citation2020). As a general rule, with a combination of measures, the effect on social distancing and viral spread depends on the degree of stringency of the measures, with stricter combinations of measures having more effects (Hussain, Citation2020). Early results suggest that in New Zealand or Taiwan, extremely low death rates were attributable to early and stringent combined measures (Summers et al., Citation2020). In low to middle-income countries the combined measures may be less effective due to a lack of proper implementation, e.g. in Indonesia (Suraya, Nurmansyah, Rachmawati, Al Aufa, & Koire, Citation2020) or lack of compliance e.g. in Brazil (Jorge et al., Citation2020).

A few studies attempt to disentangle the effectiveness of individual measures at curbing the spread of the virus. One study (Askitas et al., Citation2021) using data from 175 countries, found that since contact reducing measures were often introduced first, any restrictions introduced afterwards, e.g. movement or public transport restrictions did not make much difference because human mobility was already reduced. Studies in the U.S.A. (Courtemanche et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2021) show staying at home/shelter-in-place measures resulted in the least viral spread, but compliance with measures tends to drop over time, suggesting that public information measures could be more important than mobility restrictions for longer term containment of the virus.

Packages of measures that influence mobility behaviour naturally also have environmental effects. First of all, emissions of air pollutants, CO2 and noise are lower when the volume of traffic decreases. In addition, the spread of the COVID-19 virus has been shown to be promoted by fine particle concentrations, and so lower concentrations seem to lead to less virus spread (Magazzino, Mele, & Schneider, Citation2020) combinations of measures have reduced energy use in all sectors, including transport. Globally, CO2 emissions from mobility have decreased (Le Quéré et al., Citation2020).

4 Synthesis, policy relevance and further research

4.1. Synthesis

The results of Section 3.3 show that the categorisation of measures and effects as presented in is appropriate. Almost all literature fits the structure of . We did find some additional results, such as the influence of transport (and other) measures on water quality (Braga, Scarpa, Brando, Manfè, & Zaggia, Citation2020), but because the influence of the transport sector on water quality is limited anyway, we did not include that topic in as it falls under “environment”.

Furthermore, the literature mostly shows impacts of (combinations of) measures, often in only one area, for example the demand for public transport. Reports on combined effects are lacking, as are integral assessments of the combined effects on the various areas from . We did not come across any cost–benefit analyses or multi-criteria analyses of (combinations of) transport measures.

Many studies report the effects of combinations of measures, making it difficult to determine the contribution of individual measures, although early results suggest that the closure of venues and work places has been more effective than mobility restriction in containing the virus, albeit with subsequent negative impacts on mental health and well-being.

The studies that report mobility effects only describe the direct effects on, e.g. commuter traffic, and do not elaborate on indirect effects. The theory of constant travel time budgets shows that, measured over a large group of people, people have a constant travel time budget (see for example Mokhtarian & Chen, Citation2004). Perhaps people who work at home all day are more likely to go out in the evening for social or recreational reasons, so it is interesting to investigate the influence on total mobility behaviour.

Furthermore, the literature that looks at health effects mainly reports the effects of transport measures on intermediary health indicators, such as the degree of social distancing or travel behaviour, but not their effects on the actual spread of the COVID-19 virus. This is understandable, as it is very difficult to isolate the contribution of transport-related measures from those of other measures.

In addition, there are few studies that look at the direct and indirect health effects. Indirect effects include health effects through air pollution, exercise, stress and well-being. Those studies that have looked at well-being and mental health generally report a negative impact of travel restriction measures. Measures that lead to more walking and cycling will, almost by definition, have positive health effects, both through more exercise and higher levels of wellbeing.

Studies that report economic effects focus on partial direct effects, for instance on the turnover of the public transport sector, or state of the aviation industry. We found only a few studies that also looked at indirect effects. Suppose that people stop spending money on a holiday by plane and spend it on a new bicycle or furniture as an alternative use of their money, then there are indirect economic effects. The impact of COVID-19 on the GNP of various countries has been widely reported in popular media, but this obviously concerns all COVID-19 measures, not just those aimed at transport.

4.2. Policy relevance

Due to the above limitations, it is extremely difficult to provide ready-made policy recommendations on which measures are desirable or not, and in which context. Context factors include characteristics of a city, region or country, as well as the state of virus spread. However, it seems plausible to assume that measures that lead to more cycling and walking (at the expense of the car or public transport) score more positively than measures that lead to less travel.

Furthermore, it is plausible to assume that measures that entail travel restrictions have less of a negative impact in regions where good ICT facilities are standard, and where ICT can more often substitute for on-site activities. For example, a higher percentage of office jobs leads to less negative impact from travel restrictions than a low percentage of office jobs (and more jobs in manufacturing, distribution, education and health, for example).

For policy, it is of great importance that extensive research is carried out worldwide into the complex effects of measures on virus spread (and related health), well-being, stress, mental health, indirect health effects, economic effects and the environment. Recent research has shown that citizens may weigh these impacts very differently (Chorus, Sandorf, & Mouter, Citation2020). Moreover, it is of great importance to map integral health effects through different routes, possibly using the concept of QALY (Quality Adjusted Life Years), and to relate those effects to economic effects, so that policies aimed at virus spread (in the context of this paper: aimed at the transport sector, but of course also in general) can be compared to other health policies. We suspect that the availability of large data sets (big data) will play an important role in future research on COVID-19 in general and on transport in particular.

4.3. Future research

Future research should include contextual factors, i.e. factors influencing measures and effects. For instance, based on the literature currently found, transport-related measures seem to work less well and have more adverse effects in poorer and less developed countries, while countries with higher acceptance of surveillance technology may find it easier to contain the virus. Secondly we still poorly understand the infection risks of transport activities and related measures. This is particularly important because there are indications that the impact of transport-related measures on virus spread may be less than previously thought e.g. (Li et al., Citation2021). Third, the combined effects of measures, as mentioned above, are understudied. Fourth, this can also be said for indirect effects e.g. broader economic effects or longer-term effects and – a fifth topic – the integral health effects. Finally, we advise more research into all pros and cons of (combinations of) policy measures, using evaluation frameworks like a cost–benefit analysis, or a multi-criteria analysis. We included grey literature, but with more publications on COVID-19 and transport, we expect that future literature reviews could rely more on journal publications, downplaying the role of grey literature.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions. ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, funded the project leading to this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACAPS. (2020, November). COVID-19 government measures dataset. Retrieved from https://www.acaps.org/covid-19-government-measures-dataset

- Adegboyega, A. (2020, November). Coronavirus: Many households lack enough water, soap for handwashing – NBS. Retrieved from https://www.premiumtimesng.com/coronavirus/403003-coronavirus-many-households-lack-enough-water-soap-for-handwashing-nbs.html

- Ahammer, A., Halla, M., & Lackner, M. (2020). Mass gathering contributed to early COVID-19 spread: Evidence from US sports. Covid Economics, 2 (30).

- Aklekar, R. (2020, November). COVID-19: Mumbai needs more bus services for the public, can 1,500 school buses chip in? Retrieved from https://www.mid-day.com/articles/covid-19-mumbai-needs-more-transport-facility-can-1-500-school-buses-chip-in/22932241

- Albers, S., & Rundshagen, V. (2020). European airlines’ strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (January-May, 2020). Journal of Air Transport Management, 87(June), 101863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101863

- Ardila-Gomez, A. (2020, November). In the fight against COVID-19, public transport should be the hero, not the villain. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/transport/fight-against-COVID-19-public-transport-should-be-hero-not-villain%0A%0A

- Askitas, N., Tatsiramos, K., & Verheyden, B. (2021). Estimating worldwide effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 incidence and population mobility patterns using a multiple-event study. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81442-x

- Aucejo, E. M., French, J. F., Paola, M., Araya, U., & Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey (Nber Working Paper Series Gender). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w27392

- Bartik, A., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). What jobs are being done at home during the COVID-19 crisis? Evidence from firm-level surveys. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3634983

- BBC News. (2020, November). Coronavirus: Social distancing “impossible” on London commute. Retrieved from https://www-bbc-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.bbc.com/news/amp/uk-52645366

- Beck, M. J., Hensher, D. A., & Wei, E. (2020). Slowly coming out of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia: Implications for working from home and commuting trips by car and public transport. Journal of Transport Geography, 88(August), 102846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102846

- Benita, F. (2021). Human mobility behavior in COVID-19: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Sustainable Cities and Society, 70(April), 102916. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102916

- Bin, E., Andruetto, C., Susilo, Y., & Pernestål, A. (2021). The trade-off behaviours between virtual and physical activities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic period. European Transport Research Review, 13(1), doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-021-00473-7

- Bol, D. (2020, November). Pop-up bus lanes set for Scottish towns and cities to encourage commuters to avoid cars. Retrieved from https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/18588188.pop-up-bus-lanes-set-scottish-towns-cities-encourage-commuters-avoid-cars/

- Bonaccorsi, G., Pierri, F., Cinelli, M., Flori, A., Galeazzi, A., Porcelli, F., … Pammolli, F. (2020). Economic and social consequences of human mobility restrictions under COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- Braga, F., Scarpa, G. M., Brando, V. E., Manfè, G., & Zaggia, L. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown measures reveal human impact on water transparency in the Venice lagoon. Science of The Total Environment, 736, 139612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139612

- Buehler, R., & Pucher, J. (2021). COVID-19 impacts on cycling, 2019–2020. Transport Reviews, 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1914900

- Burroughs, D. (2020, April). Rail industry faces strong growth post-coronavirus, UBS says. Retrieved from https://www.railjournal.com/policy/rail-industry-to-expect-strong-growth-post-coronavirus-ubs-says/

- Carlson, J. (2020). NYC adds 20 miles of busways and bus lanes, 40 miles short of the MTA’s request. Retrieved from https://gothamist.com/news/nyc-adds-20-miles-busways-and-bus-lanes-40-miles-short-mtas-request

- Cartenì, A., Di Francesco, L., & Martino, M. (2021). The role of transport accessibility within the spread of the coronavirus pandemic in Italy. Safety Science, 133(September 2020), 104999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104999

- Chang, H.-H., & Meyerhoefer, C. (2020). COVID-19 and the demand for online food shopping services: Empirical evidence from Taiwan. (NBER Working Paper No. 27427).

- Chen, S. (2020). Coronavirus can travel twice as far as official ‘safe distance’ and stay in air for 30 min, Chinese study finds. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3074351/coronavirus-can-travel-twice-far-official-safe-distance-and-stay

- Chinazzi, M., Davis, J. T., Ajelli, M., Gioannini, C., Litvinova, M., Merler, S., … Vespignani, A. (2020). The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science, 368(6489), 395–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757

- Chorus, C., Sandorf, E. D., & Mouter, N. (2020). Diabolic dilemmas of COVID-19: An empirical study into Dutch society ‘ s trade-offs between health impacts and other effects of the lockdown. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, (100575).

- Chui, J. (2020). Impact of coronavirus to new car purchase in China. Ipsos, (March). Retrieved from https://www.ipsos.com/en/impact-coronavirus-new-car-purchase-china

- Cochran, A. L. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on access to transportation for people with disabilities. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 8(September), 100263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100263

- Courtemanche, C., Garuccio, J., Le, A., Pinkston, J., & Yelowitz, A. (2020). Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the covid-19 growth rate. Health Affairs, 39(7), 1237–1246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608

- de Haas, M., Faber, R., & Hamersma, M. (2020). How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ change activities, work and travel behaviour: Evidence from longitudinal data in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6, 100150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100150

- Dhaval, D., Friedson, A., Matsuzawa, K., & Sabia, J. (2020). When do shelter-in-place orders fight covid-19 best? Policy heterogeneity across states and adoption time (NBER Working Paper Series)

- Dunford, D., Dale, B., Stylianou, N., Lowther, E., Ahmed, M., & Arenas, I. d. l. T. (2020, May). Coronavirus: The world in lockdown in maps and charts. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747

- Dzisi, E. K. J., & Dei, O. A. (2020). Adherence to social distancing and wearing of masks within public transportation during the COVID 19 pandemic. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 7, 100191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100191

- Ecomobility.org. (2020a). COVID-19-focus-on-cities-and-transport-responses-south-east-asia. Retrieved from https://ecomobility.org/COVID-19-focus-on-cities-and-transport-responses-south-east-asia/

- Ecomobility.org. (2020b, November). Transport responses South America. Retrieved from https://ecomobility.org/COVID-19-focus-on-cities-and-transport-responses-south-america/

- Elsa, E. (2020, November). The human cost of India’s coronavirus lockdown: Deaths by hunger, starvation, suicide and more. Retrieved from https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/india/the-human-cost-of-indias-coronavirus-lockdown-deaths-by-hunger-starvation-suicide-and-more-1.1586956637547

- Eurofound. (2020). Covid-19 data. Retrieved from http://eurofound.link/COVID19data

- European Union. (2021, May). Reopen EU. Retrieved from https://reopen.europa.eu/en

- Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of covid-19 on small business owners: Continued losses and the partial rebound in May 2020. National Bureau of Economic Research, (July(May)). doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- FLOW. (2018). Walking, cycling and congestion, (635998).

- Friedson, A., McNichols, D., Sabia, J., & Dave, D. (2020). Did California’s shelter-In-place order work? Early coronavirus-related public health effects. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.3386/w26992

- Gkiotsalitis, K., & Cats, O. (2020). Public transport planning adaption under the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Literature review of research needs and directions. Transport Reviews. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2020.1857886

- Google. (2021a, May). Google IGO list. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1aQj-MOSep_2S5yja_IxDRpRwqdhMXzxzTmtDZO4UK40/edit?hl=en&hl=en#gid=0

- Google. (2021b, May). Google IGO search engine. Retrieved from https://cse.google.com/cse/home?cx=006748068166572874491:55ez0c3j3ey

- Hale, T., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., & Webster, S. (2020). Variation in government responses to COVID-19 (Working Paper). Retrieved from www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker

- Hamburg, (City of). (2020). Verstärkung stark beanspruchter Linien / Taxis & MOIA verstärken Nachtverkehr. Retreived from https://www.hamburg.de/pressearchiv-fhh/13768850/2020-03-29-bwvi-bus-und-bahn/?fbclid=IwAR23HFXo5GtNM7-BVE4K3qjxLzxRve17TvlCtIWD5Dg95AQ_H7q9Eg-U1Dk

- Hensher, D., & Beck, M. (2020). COVID has proved working from home is the best policy to beat congestion. Retrieved May 26, 2021, from https://theconversation.com/covid-has-proved-working-from-home-is-the-best-policy-to-beat-congestion-148926

- Hensher, D. A., Wei, E., Beck, M. J., & Balbontin, C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on cost outlays for car and public transport commuting - The case of the greater Sydney metropolitan area after three months of restrictions. Transport Policy, 101(December 2020), 71–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.12.003

- Hörcher, D., Singh, R., & Graham, D. J. (2020). Social distancing in public transport: Mobilising new technologies for demand management under the COVID-19 crisis. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3713518. (0123456789).

- Hotle, S., & Mumbower, S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on domestic U.S. Air travel operations and commercial airport service. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 9(December 2020), 100277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100277

- Hu, S., & Chen, P. (2021). Who left riding transit? Examining socioeconomic disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on ridership. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 90(December 2020), 102654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102654

- Hussain, A. H. M. B. (2020). Stringency in policy responses to covid-19 pandemic and social distancing behavior in selected countries. SSRN Electronic Journal, (April). doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3586319

- IATA. (2020). Preventing spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): guideline for airports: Fourth edition, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.iata.org/contentassets/7e8b4f8a2ff24bd5a6edcf380c641201/airport-preventing-spread-of-coronavirus-disease-2019.pdf

- IBM. (2020, November). IBM study: COVID-19 is significantly altering U.S. consumer behavior and plans post-crisis. Retrieved from https://newsroom.ibm.com/2020-05-01-IBM-Study-COVID-19-Is-Significantly-Altering-U-S-Consumer-Behavior-and-Plans-Post-Crisis

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). (2020, June). Effects of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) on civil aviation: Economic impact analysis air transport bureau contents. Retrieved from https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Documents/COVID-19/ICAO_Coronavirus_Econ_Impact.pdf

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2020). Changes in transport behaviour during the Covid-19 crisis. Retrieved November 25, 2020, from https://www.iea.org/articles/changes-in-transport-behaviour-during-the-COVID-19-crisis

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). The great lockdown: Dissecting The economic effects; World Economic Outlook, chapter 2, October 2020. World Economic Outlook, 2 (October), 65–84.

- Jorge, D. C. P., Rodrigues, M. S., Silva, M. S., Cardim, L. L., da Silva, N. B., Silveira, I. H., … Oliveirac, J. F. (2020). Assessing the nationwide impact of COVID-19 mitigation policies on the transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 in Brazil. MedRxiv. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.26.20140780

- Kamga, C., & Eickemeyer, P. (2021). Slowing the spread of COVID-19: Review of “social distancing” interventions deployed by public transit in the United States and Canada. Transport Policy, 106(March), 25–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.03.014

- Katrakazas, C., Michelaraki, E., Sekadakis, M., & Yannis, G. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on driving behavior and road safety. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 7, 100186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100186

- Klein, B., LaRock, T., McCabe, S., Torres, L., Privitera, F., Lake, B., … Vespignani, A. (2020). Assessing changes in commuting and individual mobility in major metropolitan areas in the United States during the COVID-19 outbreak. Retrieved from https://www.networkscienceinstitute.org/publications/assessing-changes-in-commuting-and-individual-mobility-in-major-metropolitan-areas-in-the-united-states-during-the-covid-19-outbreak

- Lades, L. K., Laffan, K., Daly, M., & Delaney, L. (2020). Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology, 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12450

- Lawrie, I., & Stone, J. (2020, November). How to avoid cars clogging our cities during coronavirus recovery. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/how-to-avoid-cars-clogging-our-cities-during-coronavirus-recovery-140744

- Lee, D., & Lee, J. (2020). Testing on the move: South Korea’s rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5, 100111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100111

- Le Quéré, C., Jackson, R. B., Jones, M. W., Smith, A. J. P., Abernethy, S., Andrew, R. M., … Peters, G. P. (2020). Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nature Climate Change, 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x

- Li, Y., Li, M., Rice, M., Zhang, H., Sha, D., Li, M., … Yang, C. (2021). The impact of policy measures on human mobility, COVID-19 cases, and mortality in the US: A spatiotemporal perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030996

- Linka, K., Peirlinck, M., Sahli Costabal, F., & Kuhl, E. (2020). Outbreak dynamics of COVID-19 in Europe and the effect of travel restrictions. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2020.1759560

- Magazzino, C., Mele, M., & Schneider, N. (2020). The relationship between air pollution and COVID-19-related deaths: An application to three French cities. Applied Energy, 279(August), 115835. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115835

- Maji, A., Choudhari, T., & Sushma, M. B. (2020). Implication of repatriating migrant workers on COVID-19 spread and transportation requirements. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 7, 100187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100187

- Mayor of London. (2020). Mayor and Commissioner set out vision for getting Londoners active. Retrieved from https://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/mayoral/setting-out-a-vision-for-getting-londoners-active

- Mediahub Seoul. (2020). 코로나19 막아라’ 버스정류소, 손잡이도 방역 소독. Retrieved from http://mediahub.seoul.go.kr/archives/1272185

- Medimorec, N., Enriquez, A., Hosek, E., & Peet, K. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on mobility on urban mobility. 3 (May), 1–23. Retrieved from https://slocat.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SLOCAT_2020_COVID-19-Mobility-Analysis.pdf

- Mokhtarian, P. L., & Chen, P. C. (2004). TTB or not TTB that is the question: A review and analysis of the empirical literature on travel time (and money) budgets. Transportation Research Part A, 38(9–10), 643–675.

- Morita, H., Nakamura, S., & Hayashi, Y. (2020). Changes of urban activities and behaviors due to COVID-19 in Japan. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3594054

- Mumtaz, S., Cymerman, J., & Komath, D. (2021). Cycling-related injuries during COVID-19 lockdown: A north London experience. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211007008. 194338752110070.

- Munawar, H. S., Khan, S. I., Qadir, Z., Kouzani, A. Z., & Mahmud, M. A. P. (2021). Insight into the impact of COVID-19 on Australian transportation sector: An economic and community-based perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(3), 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031276

- Musselwhite, C., et al. (2020). Editorial JTH 16 –The coronavirus disease COVID-19 and implications for transport and health. 1(January).

- National Association of City Transport Officials (NACTO). (2020a). Designing to move people. Retrieved from https://nacto.org/publication/transit-street-design-guide/introduction/why/designing-move-people/

- National Association of City Transport Officials (NACTO). (2020b). Rapid response: Emerging practices for transit agencies. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from https://nacto.org/COVID19-rapid-response-tools-for-transit-agencies/

- Nikitas, A., Tsigdinos, S., Karolemeas, C., Kourmpa, E., & Bakogiannis, E. (2021). Cycling in the era of COVID-19: Lessons learnt and best practice policy recommendations for a more bike-centric future.

- OECD. (2020a). Cities policy responses. (May), 1–55.

- OECD. (2020b). Re-spacing our cities for resilience. International Transport Forum, (May), 1–10. Retrieved from https://www.itf-oecd.org/covid-19

- O’Sullivan, F. (2020, December). In Japan and France, riding transit looks surprisingly safe. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-09/japan-and-france-find-public-transit-seems-safe

- Parady, G., Taniguchi, A., & Takami, K. (2020). Analyzing risk perception and social influence effects on self-restriction Behavior in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: First results. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3618769

- Pedbikeinfo. (2020). Local actions to support walking and cycling during social distancing dataset. Retrieved from http://pedbikeinfo.org/resources/resources_details.cfm?id=5209

- Polis Network. (2020, November). Catalonia launches app to show passengers bus occupancy levels. Retrieved from https://www.polisnetwork.eu/article/catalonia-launches-app-to-show-passengers-bus-occupancy-levels/?id=122791

- Quaife, M., van Zandvoort, K., Gimma, A., Shah, K., McCreesh, N., Prem, K., … Austrian, K. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 control measures on social contacts and transmission in Kenyan informal settlements. MedRxiv, 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.06.20122689

- Richards, T. J., Rickard, B., Nair, S., Wright, A. L., Sonin, K., Driscoll, J., & OECD (2020). Cities policy responses. Tackling coronavirus (COVID-19) contributing to a global effort. 8(1), 2–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2020.106408

- Richert, J., Martin, I. C., & Schrader, S. (2020). Beyond the immediate crisis: The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and public transport strategy.

- Ripples Nigeria. (2020, November). COVID-19: Transport operators lose N200bn in 3 months. Retrieved from https://www.ripplesnigeria.com/covid-19-transport-sd-operators-lose-n200bn-in-3-months/

- Rivoli, D. (2020). Traffic increases again as New Yorkers opt for cars over public transport due to pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/news/2020/05/14/new-yorkers-opt-for-cars-over-public-transport-in-coronavirus-times-

- Sabat, I., Neuman-Böhme, S., Varghese, N. E., Barros, P. P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., … Stargardt, T. (2020). United but divided: Policy responses and people’s perceptions in the EU during the COVID-19 outbreak. Health Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.06.009

- Saladié, Ò, Bustamante, E., & Gutiérrez, A. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown and reduction of traffic accidents in tarragona province, Spain. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100218

- Salo, J. (2020, November). Beijing tests ‘subway by appointment’ to reduce coronavirus crowding. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2020/03/04/beijing-tests-subway-by-appointment-to-reduce-coronavirus-crowding/

- Sánchez, C., Armando, M., Zanuy, C., Tardivo, A., Martín, C. S., Carrillo Zanuy, A., & Zanuy, A. C. (2020). Alessio Tardivo Covid-19 impact in transport, an essay from the railways’ systems research perspective. Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- Sherwood, H. (2020, November). Coronavirus cycling boom makes a good bike hard to find. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/may/09/coronavirus-cycling-boom-makes-a-good-bike-hard-to-find

- Shibayama, T., Sandholzer, F., Laa, B., & Brezina, T. (2021). Impact of covid-19 lockdown on commuting: A multi-country perspective. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 21(1), 70–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.18757/ejtir.2021.21.1.5135

- Sobieralski, J. B. (2020). COVID-19 and airline employment: Insights from historical uncertainty shocks to the industry. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5, 100123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100123

- Sonn, J. W. (2020, November). Coronavirus: South Korea’s success in controlling disease is due to its acceptance of surveillance. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-south-koreas-success-in-controlling-disease-is-due-to-its-acceptance-of-surveillance-134068

- Statista. (2020). Leading annoyances to employees while working from home during the coronavirus outbreak in the United States as of June 2020. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1140404/leading-annoyances-working-from-home-during-coronavirus-us/

- Suau-Sanchez, P., Voltes-Dorta, A., & Cugueró-Escofet, N. (2020). An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: Just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? Journal of Transport Geography, 86(May), 102749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102749

- Summers, D. J., Cheng, D. H. Y., Lin, P. H. H., Barnard, D. L. T., Kvalsvig, D. A., Wilson, P. N., & Baker, P. M. G. (2020). Potential lessons from the Taiwan and New Zealand health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 4(August), 100044. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100044

- Sun, X., Wandelt, S., & Zhang, A. (2021a). On the degree of synchronization between air transport connectivity and COVID-19 cases at worldwide level. Transport Policy, 105(October 2020), 115–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.03.005

- Suraya, I., Nurmansyah, M. I., Rachmawati, E., Al Aufa, B., & Koire, I. I. (2020). The impact of large-scale social restrictions on the incidence of covid-19: A case study of four provinces in Indonesia. Kesmas, 15(2), 49–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.21109/KESMAS.V15I2.3990

- Sutherland, M., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2020). Vehicle related injury patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic: What has changed? American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(9), 1710–1714. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.006

- Teixeira, J. F., & Lopes, M. (2020). The link between bike sharing and subway use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case-study of New York’s Citi bike. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6, 100166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100166

- Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C. H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U. G., … Dye, C. (2020). An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science (New York, N.Y.), 368(6491), 638–642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb6105

- Tinto, B. (2020). Spreading of SARS-CoV-2 in West Africa and assessment of risk factors. 1–9.

- Tirachini, A., & Cats, O. (2020). COVID-19 and public transportation: Current assessment, prospects, and research needs. Journal of Public Transportation, 22(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.5038/2375-0901

- Transit. (2020, November). Front-line interactions. Retrieved from https://resources.transit.app/article/268-front-line-interactions