ABSTRACT

Recently, a growing body of literature has focused on the role of daily mobility on subjective well-being (SWB). What is less well understood is the temporal effect of commuting on SWB/life satisfaction. To date, most studies addressing this temporal effect consider the impact of a residential relocation and not many studies reflect on the impact of a workplace relocation (WPR) on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. This is surprising considering that changes at the destination of a commuting trip (i.e. relocation of the workplace) could be as important as changes at the origin of a commuting trip (i.e. relocation of the place of residence). This paper, therefore, aims to provide a systematic review of the impact of a WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. Using the PRISMA method, we identified 35 papers and developed a conceptual model summarising the main relationships between workplace relocation, commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. This conceptual model also reflects four disciplinary perspectives dominating research on the impacts of a workplace relocation.

1. Introduction

There is a growing body of literature on Subjective Well-Being (SWB), a concept closely related to life satisfaction and happiness. Since the beginning of the 2010s, the role of (satisfaction with) daily mobility on SWB has gained attention. However, most studies are based on cross-sectional data and only a limited number of studies are longitudinal (Abou-Zeid et al., Citation2012; Stutzer & Frey, Citation2004). Some of these longitudinal studies are panel-based (i.e. they study the same person over several time periods), while others are based on retrospective surveys (i.e. changes before/after a specific life event). Compared to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies are much better suited to answer questions about causality and control for possible confounding factors. Nevertheless, only a few longitudinal studies of travel satisfaction exist and majority of them are restricted to analysing the impact of a residential relocation (De Vos, Citation2018; De Vos et al., Citation2019; Monteiro et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020) as this is an important origin to many trips. Only one study to date has examined the impact of changes at the destination-side of trips, especially in the context of commuting behaviour by focusing on the impact of a workplace relocation (hereafter referred to as WPR) on (satisfaction with) daily commuting and SWB (e.g. Zarabi et al., Citation2019). This is rather surprising given that commuting behaviour does not only depend on residential location choices but also workplace location choices. Therefore, the purpose of this literature review is to focus on the impacts of a WPR (be it voluntary or involuntary) on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB.

A WPR usually leads to a “window of opportunity” for changes in an individual’s commuting behaviour (Rau et al., Citation2019; Walker et al., Citation2015), commuting satisfaction (Gerber et al., Citation2020) and SWB (Zarabi et al., Citation2019). A WPR can either be the result of a decision made by an employer who wants to expand their company, increase accessibility and/or achieve societal goals (e.g. reducing pressure on central business districts) (Sprumont et al., Citation2020), or it is often the responsibility of individual employees who want to improve their SWB. According to the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) survey in the US, an individual changes jobs an average of 12 times over the course of their lifetime (Doyle, Citation2020). This number varies slightly between men (12.5 jobs) and women (12.1 jobs). According to a survey in the UK, people change jobs an average of 17 times during their career (HR News, Citation2019). Most of these changes seem to be made to advance professionally, earn a higher salary, and receive better benefits and rewards. According to a recent Prudential report on 31 countries, about 26% of workers plan to change jobs voluntarily, and more than 40% of workers consider leaving their employer voluntarily because they feel stuck at work (Castrillion, Citation2021). A preliminary analysis of Luxembourg’s social security data found that the majority of the people changed jobs voluntarily (23.8%), 2% moved from unemployment to employment and only 0.6% of people changed jobs involuntarily between 2018 and 2019 (based on the authors' own calculations using the social security dataset (IGSS) of Luxembourg). The proportion of people who chose to change jobs themselves (i.e. voluntary workplace relocation) seems to be substantially higher than the proportion of those who moved with their employer (i.e. involuntary workplace relocation).

Given the high frequency of workplace location changes over someone’s life course, it is important to know the impact of WPR on people’s daily commuting behaviour, their satisfaction with commuting, and their SWB. However, there is a knowledge gap about the impact of a WPR on these three key concepts and especially the complex interactions between commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. There are several studies on the impact of involuntary WPR on commuting behaviour in terms of commuting mode, commuting distance and travel time (Cervero & Landis, Citation1992; Hanssen, Citation1995; Pritchard & Froyen, Citation2019; Rau et al., Citation2019; St-Louis et al., Citation2014; Ye & Titheridge, Citation2017). There are other studies that analyse the interaction between workplace relocation, commuting behaviour and commuting satisfaction (Schneider & Willman, Citation2019; Ye & Titheridge, Citation2017), but only a few studies examine how changing workplace leads to changes in SWB (Fordham et al., Citation2018). Evidence on the impact of WPR on these three key concepts is thus scattered and almost no studies provide an overview of the entire interaction between workplace relocation, (changes in) commuting behaviour, (changes in) commuting satisfaction and (changes in) SWB (one exception is Zarabi et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this paper aims to provide a systematic review of the literature to present a complete overview of the interaction between WPR and these three key aspects (i.e. commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction, SWB). Although there are already a few reviews on WPR (Budiman, Citation2018; Christersson & Rothe, Citation2012; Munton & Forster, Citation1990; Zarabi & Lord, Citation2019), none of these consider the broader interaction with commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB altogether.

Thus, our review will start with a conceptualisation of the impact of WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. Section 3 describes the PRISMA methodology we used to systematically identify the relevant literature that examines the relationship between WPR and changes in commuting behaviour and/or changes in commuting satisfaction and/or changes in SWB. In Section 4, we classify the literature on WPR and describe key relationships according to four dominating perspectives, which we identified during the literature review process. We combine main findings of these four perspectives, and present a more elaborated version of our conceptual model in Section 5. In Section 6, we conclude the paper with key policy recommendations.

2. How a workplace relocation impacts commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB

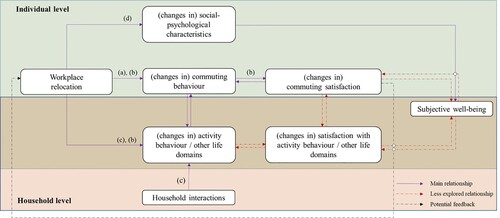

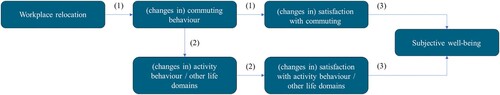

As understood from the previous section, a WPR is a frequent life event for many people, which could have important impacts on their SWB through changes in their commuting behaviour and their commuting satisfaction. De Vos et al. (Citation2013) and more recently Chatterjee et al. (Citation2020) provided a theoretical conceptualisation of the relationships between commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. We will build further on this work by putting WPR at centre stage (see ). This is important given that evidence to date on the impacts of a WPR is not conclusive and stronger evidence for causal inferences is needed.

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of the impact of WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB.

Firstly, WPR could invoke a change in transport mode, commute route, travel distance and travel time (Lanzendorf, Citation2003; Zarabi & Lord, Citation2019). Changes in these aspects of commuting behaviour may also lead to changes in commuting satisfaction (De Vos et al., Citation2019; Ye & Titheridge, Citation2017) (see arrow 1 in ).

Second, WPR not only has an impact on commuting behaviour but also on activities other than commuting and satisfaction with these activities/other life domains (see arrow 2 in ). For instance, Rau et al. (Citation2019) found that a short-distance WPR in Munich disrupted worker’s daily routine and mobility practices, as the new workplace offered fewer opportunities for trip chaining. Many authors speak about the “bundles of interacting practices” which means that changes in one activity location could often leads to changes in other activities/life-domains (von Behren et al., Citation2018; Zax & Kain, Citation1991).

Finally, a WPR also impacts individuals’ SWB either through changes in commuting behaviour and commuting satisfaction or through changes in other activities and satisfaction with these activities (see arrow 3 in ) (Chatterjee et al., Citation2020; Fordham et al., Citation2018; Heady et al., Citation1991). Our conceptualisation of the relationships between workplace relocation, commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB is shown in .

3. Methodology

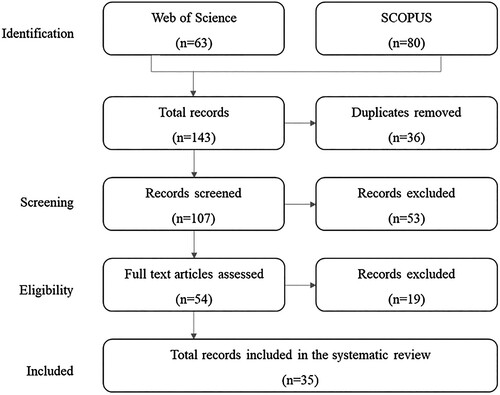

3.1. Search strategy

Three electronic databases (Web of Science, SCOPUS and Google Scholar) were searched for studies that investigated the influence of a WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. However, Google Scholar did not yield a substantial improvement, so we included only peer-reviewed publications with Web of Science and Scopus. We then used the PRISMA methodology (Moher et al., Citation2009) to select relevant studies for our literature review (). First, we identified articles based on our search syntax.Footnote1 We specifically did not include a start date because WPR has been a recent topic of discussion in the existing literature on travel (commute) satisfaction and SWB. We searched for articles published until July 2020. This resulted in 143 research papers. Next, duplicates were removed. Second, we screened the articles based on a first reading of the title, keywords and abstract. Only articles published in English were included. We excluded articles that examined (i) predictors of workplace relocation; (ii) factors affecting the willingness to relocate; (iii) relocation mobility readiness; (iv) a workplace change due to change in residential location; (v) workplace design; and (vi) review papers. These articles were excluded because they focused on the relocation process instead of the impacts of workplace relocation. The full articles were then retrieved/downloaded and the full text was read. Some articles were eventually judged to be irrelevant after reading the full text. This resulted in a final list of relevant papers (N = 35).

3.2. Data extraction strategy

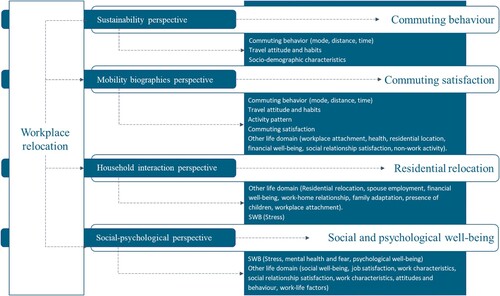

Following this PRISMA methodology, we identified 35 empirical studies for our literature review, but we do not claim that this is an exhaustive list. After an initial review of these studies, some overlap was identified in terms of the impact/outcomes of workplace relocation. In order to understand the different outcomes of WPR from different disciplines, we classified papers with similarities under one perspective and papers with differences under other perspectives. In doing so, four dominating disciplines/perspectives became apparent. Studies that analyse modal shift and whether people shift to a more sustainable urban transport mode after a WPR are classified under the Sustainability perspective (N = 10). Studies that explain the changes in individual’s commuting behaviour following a life event (i.e. workplace relocation) are classified under the Mobility biographies perspective (N = 7). Studies that explain reorganisation of household activities in response to a WPR are classified under the Household interaction perspective (N = 6). Finally, studies of individuals’ well-being post-relocation are classified under the Social-Psychology perspective (N = 12).

Most of these studies are from Europe, although some are based on data from other regions, such as the U.S., Canada and Australia. For each study, we have summarised relevant information such as author’s name, year of publication, spatial context, sample size, data collection method, methodology and key impacts in a matrix format (see in the following section). These matrices provide detailed information about the studies reported in this review and allow the reader to make comparisons between the variables included in each study, under each perspective.

Table 1. Comparison of studies linked with sustainability perspective.

Table 2. Comparison of studies linked with mobility biographies perspective.

Table 3. Comparison of studies linked with household interaction perspective.

Table 4. Comparison of studies linked with social-psychology perspective.

4. Results

In what follows, we summarise the key impacts of a WPR under each of the four perspectives. These impacts are in line with the basic conceptual model demonstrated in , which first looks at the impact on commuting behaviour followed by commuting satisfaction, then the impact on activities other than commuting and satisfaction with these activities and then finally the link to SWB.

4.1. Sustainability

Studies under the Sustainability perspective focus on the first relationship highlighted in , which is the impact of a WPR on commuting behaviour, in particular on changes in terms of modal shift. Even if WPR is a consequence of national policies aimed at decentralising central business districts or developing transit-oriented cities, the impact on individual’s commuting behaviour is significant. This is because after workplace relocation, people may be forced to change their travel mode (e.g. if the distance to the new job increases significantly) and reconsider their travel behaviour. Ten studies were ranked under this perspective that focuses on factors responsible for stimulating more sustainable and less sustainable commuting after the move (see ). These studies focused on three types of relocation: (i) city centre to the suburb relocation (N = 4), (ii) suburb to city centre relocation (N = 5) and (iii) interurban relocation (N = 1).

4.1.1. Relocation from the suburb to the city centre

All four studies reported a decrease in car use and an increase in walking, cycling, public transport use, and carpooling after the move. Factors that influenced this modal shift included higher car parking pricing in city centres, shorter commute distances/times and higher traffic congestion (Frater et al., Citation2019). Other factors included availability of car parking, incentives to carpooling, encouraging the use of public transport and active transport, and educating employees regarding carbon footprint (Cumming et al., Citation2019). Another study with data from Rome found an increase in the use of active and public transport and a decrease in car use as a result of restricting city centre areas for cars. Such an intervention not only resulted in a modal shift, but also promoted the use of car-sharing, carpooling, park and ride and broke car-dependent habits. Traditional factors of travel behaviour studies such as change in travel time, distance and route also lead to changes in commuting decisions (Pritchard & Froyen, Citation2019). Altogether, the four studies reported different techniques to encourage the use of sustainable transport modes and reduce car dependence after moving the workplace from the suburb to the inner city.

4.1.2. Relocation from the city centre to the suburb

Studies related to employment decentralisation (i.e. a WPR from city centre to the suburbs) provide strong evidence of a shift from sustainable modes to motorised vehicles (Cervero & Landis, Citation1992; Cervero & Wu, Citation1998). We identified five empirical studies with similar conclusions. Yang et al. (Citation2017) pointed out how this modal shift to motorised vehicles is influenced by changes in aspects of commuting behaviour (e.g. longer commuting distance and an increase in commuting time), and the built environment of the new workplace (e.g. low public transport accessibility in the suburbs). Sprumont et al. (Citation2014) found an increase in travel time, travel distance, a lack of public transport accessibility, and a lack of safe infrastructure for walking and cycling in the suburbs. Other studies reached similar conclusions (Aarhus, Citation2000; Vale, Citation2013). Hanssen (Citation1995) reported more than one transfer on the journey to work by public transport as a barrier to the use of public transport. In sum, all five studies reported a shift from sustainable transport modes to commuting by car.

4.1.3. Inter-urban relocation

Only one study considered inter-urban relocation. Walker et al. (Citation2015) noted an increase in the use of sustainable travel modes and a decrease in reliance on private vehicles. The main reason for this change in travel mode was attributed to people’s travel habits and attitudes. As a pro-environment group of employees were relocated, regardless of the type of relocation, these people would use active and public transport instead of private cars because of their attitudes towards travel.

In conclusion, the underlying principle of the Sustainability perspective is to study the factors that encourage and discourage sustainable commuting mode choices. To foster a shift towards sustainable modes of commuting, strategies such as increase in car pricing, increase in the use of carpooling, restricting city centre area to cars, etc. are widely encouraged. The evidence from these 10 studies are conclusive and mainly focuses on company moves (i.e. involuntary workplace relocation) and the direction of the move (from city centre to suburbs indicates a shift from sustainable modes to car, whereas, the reverse encourages sustainable transport options).

4.2. Mobility biographies

The Mobility Biographies perspective goes one step further compared to the sustainability perspective and focuses on other aspects of commuting behaviour such as commuting distance and travel time and not only on the commuting mode. In addition, these studies also examine the impact on satisfaction with commuting (first relationship in ). Based on the conceptual framework of Salomon and Ben-Akiva's (Citation1983) who positioned daily travel behaviour within long-term lifestyle decisions, Lanzendorf (Citation2003) formulated the mobility biographies framework. This framework connects three domains in which life events may occur that impact daily travel behaviour: (i) lifestyle domain including changes in demographics, education, profession and leisure, (ii) accessibility domain including changes in residential location, workplace and ownership of mobility tools and (iii) mobility domain including changes in activity and travel behaviour. Given the focus of this paper on workplace relocation, we found seven studies in this perspective that examine the effect of a WPR on changes in commuting behaviour and commuting satisfaction (see ).

Most studies found that a WPR has an indirect effect on commuting satisfaction, mediated via (changes in) commuting behaviour. Some studies reported the effect of changes in commuting time on commuting satisfaction (Bell, Citation1991; Carrese et al., Citation2019; Gerber et al., Citation2020; von Behren et al., Citation2018), while other studies reported the effect of a change in commuting mode on commuting satisfaction after the move (Bell, Citation1991; Carrese et al., Citation2019; von Behren et al., Citation2018; Zarabi et al., Citation2019). Gerber et al. (Citation2020) observed an increase in commuting satisfaction due to a reduction in the daily commute time of hospital workers following the relocation of a hospital in Montreal, Canada. von Behren et al. (Citation2018) also pointed out a similar relationship, where employees began using public transport instead of cars to reduce their average commuting time and distance after an involuntary WPR from suburbs to the inner city in Karlsruhe, Germany. This was because public transport was much faster and congestion-free compared to car use. However, some studies found the opposite – where employees shifted from public transport to cars, with the same goal of reducing their travel time (Bell, Citation1991; Carrese et al., Citation2019). In contrast, Sprumont and Viti (Citation2018) witnessed an increase in commuting distance among employees of the University of Luxembourg after the University moved from a location in the city of Luxembourg to a location in the south of the country.

Compared to previous studies focusing on the impact of a WPR on commuting behaviour and commuter satisfaction, Zarabi et al. (Citation2019) nuanced these findings by examining the issue of consonance. They found that people did not necessarily use their preferred mode of transport after a WPR and even then, most of these dissonant commuters were satisfied with their commute because they were satisfied with other domains of their life such as general health, residential location, saving/spending money, and etc. This made travel dissatisfaction bearable (or even beneficial). In other words, they found that travel mode consonance (or dissonance) and commuting satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) are not necessarily positively related.

Like the earlier study by Zarabi et al. (Citation2019), a limited number of studies from the mobility biographies perspective also scratch the surface of changes in activities/life-domains other than commuting. For instance, Gerber et al. (Citation2020) found that employees with greater attachment to their new workplace indicated higher satisfaction with their commuting. Sprumont and Viti (Citation2018) found that the large distance relocation of the University campus from the city centre to the suburb not only affected individuals’ commuting behaviour, but also led to a complete modification in their daily activities, such as shopping, lunch and other non-work related activities. von Behren et al. (Citation2018) reported changes in the daily routine of other household members and their daily travel chain after one of the household members changed their workplace. Rau et al. (Citation2019) reported a decline in employees’ satisfaction with commuting after relocating their workplace, due to factors such as fewer opportunities for trip chaining, a longer duration of commuting and a decline in the frequency of after-work drinks with colleagues.

In summary, studies using the mobility biographies perspective usually focus on the impact of WPR on commuting behaviour and satisfaction with commuting. Only a few studies stretch a bit to analyse the effect on satisfaction with life domains other than commuting. As a result, we have only a partial understanding of the relationship between WPR and change in activity behaviour/life domains other than commuting.

4.3. Household interaction

While the mobility biographies perspective pays limited attention to the impact of WPR on household interactions or changes in other life domains, the household interaction perspective elaborates on these changes in life domains/activities other than commuting (second relationship in ). Schönfelder and Axhausen (Citation2010) reported that WPR impacts the reorganisation of household tasks. To take a step back and understand these household interactions, Olson et al. (Citation1983) introduced the theoretical model of Family Functioning. Studies based on this theoretical model examined the relationship between a major life event (e.g. a workplace change or a change of residence) and the reorganisation of household tasks. They focused on how changes in one person's commute affect the lives of other household members. We identified six studies that provide insights into this relationship and shed light on adaptation strategies following a workplace change of a household member (see ).

Most studies have observed residential relocation of the entire household as an adaptation strategy following a WPR of one household member (Burke & Miller, Citation2017; Lawson & Angle, Citation1994; Munton & Reynolds, Citation1995; Rives & West, Citation1993). The main determinants leading to a change of residence are related to gender roles and the extent of the other person's attachment to their employment. For instance, Rives and West (Citation1993) found that wife’s employment and her attachment to the workplace were strong barrier to changing residence. In contrast, Lawson and Angle (Citation1994) found that the spouse's employment was not an important factor in the decision to change residence. Burke and Miller (Citation2017) reported that families who chose to relocate observed significant effects on spouse employment and their financial well-being.

Other factors, such as family size, attachment to the community, employees’ tenure with their company, presence of children in the household and experience with residential relocation also influenced the decision to relocate. For instance, two studies found that families who began making small changes in response to their change of residence adapted more easily to the new location than families who had no previous experience with relocation (Lawson & Angle, Citation1994; Munton & Reynolds, Citation1995).

Some studies also examined the impact of a WPR on household interaction factors such as stress, conflict between spouses, distribution of household chores and maintenance of social relationships (Munton, Citation1990; Wiersma, Citation1994). Stress factors include being away from family and friends, establishing new relationships at work, spouse employment, property issues related to buying and selling a house, finding a new home, children's education and changes in living standards. Munton and Forster (Citation1990) reached similar findings in their review.

Overall, the household interaction perspective focuses on the interaction with other activities, especially moving residence, but often neglects the preceding steps of the impact of a WPR on the individual's commuting behaviour and commuting satisfaction. Nevertheless, it is important to understand this perspective, as it sheds light on how a change in one person's workplace can have cascading effects on the different spheres of life of the other household members. As little attention has been paid to the interaction between household members and their satisfaction with life domains other than commuting, future studies should take this into account when deciphering the impact of workplace relocation.

4.4. Social-psychology

Studies from a household interaction perspective have already touched upon the social-psychology perspective by focusing on the stress induced by a household member workplace relocation. This perspective takes it a step further by linking it to SWB and social psychological well-being (last relationship in ). As moving to another workplace is a complex event from a social-psychological perspective (Zarabi & Lord, Citation2019), it can induce a lot of stress for people, impact on their mental health and affect their social-psychological well-being (Martin, Citation1996). Therefore, it seems essential to analyse this perspective from the point of view of workplace relocation. With this in mind, we have identified 12 case studies that show the impact of workplace change on workers’ social-psychological well-being (see ).

Several studies in social-psychology analysed the influence of a WPR on an individual's relocation-related stress based on a comparison between a group of relocated employees and another group of non-relocated employees. Martin (Citation1996) found that for male employees, relocation-related stress significantly decreased after their workplace relocation, while for female employees, stress remained the same before and after the relocation. In another study, Martin (Citation1999) found that employees who reported greater preparation for the relocation had better mental health and higher job satisfaction after the relocation compared to employees who did not mentally prepare for the relocation of their workplace. In a subsequent study, Martin et al. (Citation2000) reported that people who perceived/expected many relocation-related problems (e.g. disruption to children’s education, household members losing social ties, disruption of family life and employment-related problems) experienced poor mental health, stress and job dissatisfaction. This was also true for those who were pessimistic and had a negative psychological outlook. In similar lines, other studies reported an increase in psychosocial stress, disruption with work-related adjustments, poor mental health and lower subjective well-being for those who relocated compared to the control group (Anderzén & Arnetz, Citation1997, Citation1999; Zeng et al., Citation2015).

Since a WPR involves a change in the work characteristics, the effects may include disruption of the work-life factors. The work-life factors includes organisational constraints, sense of uncertainty and isolation, increase in job insecurity (Bellagamba et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, Joslin et al. (Citation2010) found that employees with positive relations at work were more likely to change their attitude and behaviour towards work in order to be accepted by their colleagues at the new workplace, thereby reducing their work-life conflicts at home. They further pointed out that mood, behaviour and attitude experienced at work have a direct effect on psychological distress.

Christersson et al. (Citation2017) identified psychological factors that are influenced by a workplace relocation. This includes resistance to change, feelings of fear and stress, new ways of working and associated behavioural change, as well as shifts in organisational dynamics. Eilam and Shamir (Citation2005) suggested that employees are resistant to change. They support it only when it is in line with their self-concepts otherwise they experience the change as stressful. Brandis et al. (Citation2016) found that if employees’ efforts at work are recognised, their job satisfaction increases. Munton and West (Citation1995) found that employees with positive self-esteem were likely to report innovating at work in response to workplace relocation. These workers also reported better mental health and were able to handle stress during the relocation. In other words, role innovation may be an important strategy for dealing with negative well-being effects of a job relocation. Alternatively, they also found that people with low self-esteem were more likely to report changes in their values, attitudes, career goals and personality in response to a job relocation.

In summary, the social-psychological perspective includes studies that link the impacts of WPR to people's SWB. The evidence for the social-psychological consequences is conclusive. The most common and widely discussed outcome is an increase in stress and poor mental health.

Thus, the body of evidence reviewed in this study suggests a variety of main and secondary outcomes of a workplace relocation. These outcomes are synthesised into four perspectives, as illustrated in .

5. An elaborated conceptual model and avenues for future research

Based on our understanding of the four perspectives, we have gained better insights into the complex interaction between workplace relocation, commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. Based on these insights, we have elaborated the basic conceptual model.

The elaborated conceptual model, illustrated in , describes the relationship between WPR and its key aspects in a person’s life course at both individual and household level. A WPR could affect four relationships, namely (a) a person's commuting behaviour, followed by (b) their satisfaction with commuting, (c) their activity behaviour/life domains other than commuting, followed by their satisfaction with these life domains, and (d) their social psychological characteristics. The activity behaviour or changes in areas of life other than commuting also depend on how the individual interacts with other household members (c). Relationships a, b, c and d correspond to the insights gained from Sustainability, Mobility biographies, Household interaction and the Social-psychological perspective, respectively.

Nevertheless, there might be other possible effects of WPR that we know from existing studies but are not covered by these four perspectives (see red dashed lines in ). For instance, previous studies have often indicated that satisfaction with commuting influences SWB (De Vos et al., Citation2013; Friman et al., Citation2017; Zarabi et al., Citation2019). Satisfaction with life domains other than commuting also influences SWB (Diener, Citation1984; Veenhoven, Citation2012). Chatterjee et al. (Citation2017) suggested an indirect impact of satisfaction with commuting on SWB through its impact on satisfaction with life domain other than commuting. The impact of WPR on satisfaction with life domains other than commuting and SWB has not been adequately studied. Potential life domains include satisfaction with job, accommodation, salary, living environment, leisure, social relationships and recreational space. It is important to examine satisfaction with life and life domains as there is evidence that time spent commuting affects time spent on other activities and thus SWB (Christian, Citation2012; Hilbrecht et al., Citation2014; Nie & Sousa-Poza, Citation2018). Because interaction with other life domains is neglected, especially through a WPR lens, studies cannot examine how individuals cope with travel dissatisfaction in their personal lives. Previous studies are largely based on cross-sectional data and we cannot be sure of causal conclusions.

Furthermore, there is evidence that WPR of one of the household members affects the organisation of activities of other household members; however, the impact of WPR on household member’s satisfaction with different life domains is often overlooked. Mao and Wang (Citation2020) used data from Beijing to investigate the effects of a residential relocation on household couples’ SWB. Data collection in two waves showed significant improvements in SWB for both household heads. The increase in SWB for male household heads was due to improvements in social relationships and the physical environment, while SWB for female household heads improved due to better transport links. However, future research is required to understand the impact of a WPR of one household member on satisfaction with life domains of other household members and vice versa.

There are also some feedback effects that we know from other empirical studies that are not about the impact of a WPR (see red dashed lines in ). For instance, previous studies, have often pointed out that satisfaction with life domains such as job, leisure, physical and social time influences satisfaction with commuting (Abou-Zeid & Ben-Akiva, Citation2012; Hilbrecht et al., Citation2014; Maheshwari et al., Citation2022; Wheatley, Citation2014). SWB also influences individuals’ satisfaction with commuting (De Vos, Citation2019; Gao et al., Citation2017; Maheshwari et al., Citation2022) and satisfaction with life domains other than commuting (Heady et al., Citation1991). As these relationships are relevant to a WPR but less researched, they mark important knowledge gaps in the current state-of-the-art on workplace relocation.

The elaborated conceptual model also includes a feedback loop (black dashed line). The literature review started with the question of the impact of WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction, and SWB of people. However, we can also reverse this and ask whether people who are dissatisfied with their commuting are also more likely to change their commuting behaviour by changing workplaces in the subsequent year. Using longitudinal data for workers in England, Chatterjee et al. (Citation2017) found that workers with longer commutes of over 45 minutes one way tended to have lower SWB than other workers and were more likely to change jobs in the following year. Therefore, to provide more insights into the feedback loop, a longitudinal perspective is needed that looks at the level of commuting satisfaction in year t and the likelihood to changing workplaces in the subsequent year (t+1). Nevertheless, future research should be devoted to understanding the direction of causality. Supplementing the available quantitative research with qualitative analysis can also help to gain better insights into the causal relationship (Clifton & Handy, Citation2003).

Finally, most of the studies included in this review focus on involuntary moves. The effects of a voluntary move on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and satisfaction in other life domains are poorly understood. We believe that satisfaction with life and life domains, including commuting, is affected differently in voluntary and involuntary moves. Future research should be devoted to understanding differences in these effects. It is important to analyse these relationships because the workplace is not an isolated aspect, but may encompass changes in many other life domains. Future research on WPR should examine these perspectives together to gain a better understanding of the wider impacts of a workplace relocation, particularly by examining a more longitudinal analysis.

In summary, the data presented in this paper merely touch upon the red and black dashed relationships. Therefore, these relationships are open for future research. Since the evidence is limited, we do not have a complete picture of the impacts of a WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction, satisfaction with life domains other than commuting, and life satisfaction.

6. Conclusion and policy recommendations

This comprehensive literature review provides an overview of factors/outcomes of a WPR from each of the four perspectives and the knowledge gap in the literature on commuting and SWB. Key concepts from these four perspectives have been integrated into the conceptual model to provide a robust understanding of the impacts of a WPR on commuting behaviour, commuting satisfaction and SWB. The insights gained from this review will help policymakers and practitioners identify areas of life where tailored interventions are needed to increase people’s SWB. Based on the conceptual model created in this study, we finally give an overview of policy recommendations, which have been proposed in existing studies and are in line with our model.

6.1. Recommendations linked to a WPR

WPR is a consequence of national policies aimed at decentralising central business districts or developing transit-oriented cities. We recommend that future companies keep in mind the direction of the relocation to mitigate any potential model shift towards car. Other factors such as ease of access to the new workplace, connectivity to public transport, availability of paid parking and the presence of a mixed-use development also matter (Cervero & Landis, Citation1992).

6.2. Recommendations linked to (satisfaction with) commuting behaviour

Ettema et al. (Citation2010) suggest that the goal of policymakers should be to increase commuter satisfaction. This could mean investing in soft modes, as the use of soft modes is associated with higher SWB (Ettema et al., Citation2016). This could also be done by making public transport infrastructure efficient as delays, overcrowding and strikes can affect commuter satisfaction more than high ticket costs (Sprumont, Citation2017). Another strategy is to relax working from home policies at the workplace, as a poor commute can become more acceptable if it only has to be done once or twice a week. Results have shown that working from home reduces work-home conflicts and increase satisfaction with work, family and life (Beutell, Citation2010). Another study observed a decrease in work-home conflicts when employees were offered flexible work arrangements (Anderson et al., Citation2002). Lastly, efforts should be made to study/evaluate individuals’ daily trips, as the end of a journey (the destination) plays an important role in how people evaluate their travel experience.

6.3. Recommendations linked to (satisfaction with) other life domains/activities

A recent study by Sprumont and Viti (Citation2018) illustrates how relocating a workplace to a monofunctional area negatively impacts employees’ activity patterns. In contrast, relocating workplaces to a mixed-use area can help workers run errands on their way home and reduce the need for multiple long trips, which significantly increases workers’ overall well-being. Policy makers and practitioners are recommended to pay attention to the analysis of the daily activity chain of individuals to understand their commuting behaviour and allow multiple transport options within the city so that individuals and their household members can run their daily errands with satisfaction.

6.4. Recommendations linked to SWB

Changes in WPR are associated with changes in individuals’ SWB. The results suggest that employees are less stressed and worried about the move if the employer informs its employees about the move early or increases awareness about the moving process by organising training for employees before the move. This is because it gives them time to make adjustments in their daily activities and the lives of their household members (Munton & Forster, Citation1990). Another way to increase employees’ social-psychological and SWB is to pay attention to their satisfaction with commuting and satisfaction with life domains other than commuting.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers and the assigned editor-in-chief for their constructive feedback. The paper has benefited greatly from their comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Workplace relocation” OR “Organi* relocation” OR “Job* relocation” OR “Relocat* employees” OR “Voluntary workplace relocation” OR “Involuntary workplace relocation” OR “Staff relocation” OR “Office relocation” AND “Travel satisfaction” OR “Commut* satisfaction” OR “Travel behavio*” OR “Commut* behavio*” OR “Behavio* change” OR “Daily travel” OR “Transport*” OR “Mobilit*” OR “Subjective wellbeing” OR “Subjective well-being” OR “Overall life satisfaction” OR “Overall-life satisfaction” OR “Life satisfaction” OR “Wellbeing” OR “Well-being” OR “Quality of life” OR “Happiness” OR “Satisfaction”.

References

- Aarhus, K. (2000). Office location decisions, modal split and the environment: The ineffectiveness of Norwegian land use policy. Journal of Transport Geography, 8(4), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(00)00009-0

- Abou-Zeid, M., & Ben-Akiva, M. (2012). Well-being and activity-based models. Transportation, 39(6), 1189–1207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-012-9387-8

- Abou-Zeid, M., Witter, R., Bierlaire, M., Kaufmann, V., & Ben-Akiva, M. (2012). Happiness and travel mode switching: Findings from a Swiss public transportation experiment. Transport Policy, 19(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2011.09.009

- Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(02)00190-3

- Anderzén, I., & Arnetz, B. B. (1997). Psychophysiological reactions during the first year of a foreign assignment: Results of a controlled longitudinal study. Work and Stress, 11(4), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379708252994

- Anderzén, I., & Arnetz, B. B. (1999). Psychophysiological reactions to international adjustment. Results from a controlled, longitudinal study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68(2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012315

- Bell, D. A. (1991). Office location - city or suburbs? Travel impacts arising from office relocation from city to suburbs. Transportation, 18(3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00172938

- Bellagamba, G., Michel, L., Alacaraz-Mor, R., Giovannetti, L., Merigot, L., Lagouanelle, M. C., Guibert, N., & Lehucher-Michel, M. P. (2016). The relocation of a health care department’s impact on staff. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(4), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000664

- Beutell, N. J. (2010). Work schedule, work schedule control and satisfaction in relation to work-family conflict, work-family synergy, and domain satisfaction. Career Development International, 15(5), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011075358

- Brandis, S., Fisher, R., McPhail, R., Rice, J., Eljiz, K., Fitzgerald, A., Gapp, R., & Marshall, A. (2016). Hospital employees’ perceptions of fairness and job satisfaction at a time of transformational change. Australian Health Review, 40(3), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH15031

- Budiman, A. (2018). Employee transfer - A review of recent literature. Journal of Public Administration Studies, 3(1), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jpas.2018.003.01.5

- Burke, J., & Miller, A. R. (2017). The effects of job relocation on spousal careers: Evidence from military change of station moves. Economic Inquiry, 56(2), 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12529

- Carrese, F., Cantelmo, G., Fusco, G., & Viti, F. (2019). Leveraging gis data and topological information to infer trip chaining behaviour at macroscopic level. MT-ITS 2019 - 6th International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/MTITS.2019.8883329

- Castrillion, C. (2021). Why millions of employees plan to switch jobs post-pandemic. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolinecastrillon/2021/05/16/why-millions-of-employees-plan-to-switch-jobs-post-covid/?sh=63ab596e11e7

- Cervero, R., & Landis, J. (1992). Suburbanization of jobs and the journey to work: A submarket analysis of commuting in the San Francisco bay area. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 26(3), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/atr.5670260305

- Cervero, R., & Wu, K. L. (1998). Sub-centring and commuting: Evidence from the San Francisco Bay area, 1980-90. Urban Studies, 35(7), 1059–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984484

- Chatterjee, K., Chng, S., Clark, B., Davis, A., De Vos, J., Handy, S., Martin, A., & Reardon, L. (2020). Commuting and wellbeing : A critical overview of the literature with implications for policy and future research. Transport Reviews, 40(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2019.1649317

- Chatterjee, K., Clark, B., Davis, A., & Toher, D. (2017). The commuting and wellbeing study. https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/research/publications/524474

- Christersson, M., Heywood, C., & Rothe, P. (2017). Social impacts of a short-distance relocation process and new ways of working. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 19(4), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-02-2016-0008

- Christersson, M., & Rothe, P. (2012). Impacts of organizational relocation: A conceptual framework. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 14(4), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-12-2012-0030

- Christian, T. J. (2012). Automobile commuting duration and the quantity of time spent with spouse, children, and friends. Preventive Medicine, 55(3), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.015

- Clifton, K. J., & Handy, S. L. (2003). Qualitative methods in travel behaviour research. In P. Jones & P. R. Stopher (Eds.), Transport survey quality and innovation, (pp. 283–302). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781786359551-016

- Cumming, I., Weal, Z., Afzali, R., Rezaei, S., & Osman, A. (2019). The impacts of office relocation on commuting mode shift behaviour in the context of transportation demand management (TDM). Case Studies on Transport Policy, 7(2), 346–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2019.02.006

- De Vos, J. (2018). Do people travel with their preferred travel mode? Analysing the extent of travel mode dissonance and its effect on travel satisfaction. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 117(April), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.08.034

- De Vos, J. (2019). Analysing the effect of trip satisfaction on satisfaction with the leisure activity at the destination of the trip, in relationship with life satisfaction. Transportation, 46(3), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-017-9812-0

- De Vos, J., Ettema, D., & Witlox, F. (2019). Effects of changing travel patterns on travel satisfaction: A focus on recently relocated residents. Travel Behaviour and Society, 16, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.04.001

- De Vos, J., Schwanen, T., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2013). Travel and subjective well-being: A focus on findings, methods and future research needs. Transport Reviews, 33(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2013.815665

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 545–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

- Doyle, A. (2020). How often do people change jobs? Balance Careers. https://www.thebalance.com/how-often-do-people-change-jobs-2060467

- Eilam, G., & Shamir, B. (2005). Organizational change and self-concept threats: A theoretical perspective and a case study. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(4), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886305280865

- Ettema, D., Friman, M., Gärling, T., & Olsson, L. E. (2016). Travel mode use, travel mode shift and subjective well-being – Overview of theories, empirical findings and policy implications. In D. Wang & S. He (Eds.), Mobility, sociability and well-being of urban living (pp. 129–150). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-48184-4

- Ettema, D., Gärling, T., Olsson, L. E., & Friman, M. (2010). Out-of-home activities, daily travel, and subjective well-being. Transportation Research Part A, 44(9), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2010.07.005

- Fordham, L., van Lierop, D., & El-Geneidy, A. (2018). Examining the relationship between commuting and it’s impact on overall life satisfaction. In M. Friman, D. Ettema, & L. E. Olsson (Eds.), Quality of life and daily travel. Applying quality of life research. (pp. 157–181). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76623-2_9

- Frater, J., Vallance, S., Young, J., & Moreham, R. (2019). Disaster and unplanned disruption: Personal travel planning and workplace relocation in Christchurch, New Zealand. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 8(2), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2019.11.003

- Friman, M., Gärling, T., Ettema, D., & Olsson, L. E. (2017). How does travel affect emotional well-being and life satisfaction? Transportation Research Part A, 106, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.09.024

- Gao, Y., Rasouli, S., Timmermans, H., & Wang, Y. (2017). Understanding the relationship between travel satisfaction and subjective well-being considering the role of personality traits: A structural equation model. Transportation Research Part F, 49, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.06.005

- Gerber, P., El-Geneidy, A., Manaugh, K., & Lord, S. (2020). From workplace attachment to commuter satisfaction before and after a workplace relocation. Transportation Research Part F, 71, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2020.03.022

- Hanssen, J. U. (1995). Transportation impacts of office relocation. A case study from Oslo. Journal of Transport Geography, 3(4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/0966-6923(95)00024-0

- Heady, B., Veenhoven, R., & Wearing, A. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292652

- Hilbrecht, M., Smale, B., & Mock, S. E. (2014). Highway to health? Commute time and well-being among Canadian adults. World Leisure Journal, 56(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2014.903723

- HR News. (2019). The UK’s Job Hopping Habits - AppJobs. Codel Software Ltd. https://www.appjobs.com/blog/the-uk-s-job-hopping-habits

- Joslin, F., Waters, L., & Dudgeon, P. (2010). Perceived acceptance and work standards as predictors of work attitudes and behavior and employee psychological distress following an internal business merger. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011013858

- Lanzendorf, M. (2003). Mobility biographie: A new perspective for understanding travel behaviour. Moving through Nets: The Physical and Social Dimensions of Travel, August.

- Lawson, M. B., & Angle, H. L. (1994). When organizational relocation means family relocation: An emerging issue for strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management, 3(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930330104

- Maheshwari, R., Van Acker, V., De Vos, J., & Witlox, F. (2022). Analyzing the association between satisfaction with commuting time and satisfaction with life domains: A comparison of 32 European countries. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 15(1), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2022.2121

- Mao, Z., & Wang, D. (2020). Residential relocation and life satisfaction change: Is there a difference between household couples? Cities, 97(102565). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102565

- Martin, R. (1996). A longitudinal study examining the psychological reactions of job relocation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01850.x

- Martin, R. (1999). Adjusting to job relocation: Relocation preparation can reduce relocation stress. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(2), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166626

- Martin, R., Leach, D. J., Norman, P., & Silvester, J. (2000). The role of attributions in psychological reactions to job relocation. Work and Stress, 14(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370010029186

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

- Monteiro, M. M., Silva, d. A. e., Afonso, J., Ingvardson, N., B, J., & de Sousa, J. P. (2021). Residential location choice and its effects on travel satisfaction in a context of short-term transnational relocation. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 14(1), 975–994. https://doi.org/10.5198/JTLU.2021.1952

- Munton, A. G. (1990). Job relocation, stress and the family. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(5), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110507

- Munton, A. G., & Forster, N. (1990). Job relocation: Stress and the role of the family. Work & Stress, 4(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379008256967

- Munton, A. G., & Reynolds, S. (1995). Family functioning and coping with change - a longitudinal test of the circumplex model. Human Relations, 503(1), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679504800904

- Munton, A. G., & West, M. A. (1995). Innovations and personal change: Patterns of adjustment to relocation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160407

- Nie, P., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2018). Commute time and subjective well-being in urban China. China Economic Review, 48, 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.03.002

- Olson, D. H., Russell, C. S., & Sprenkle, D. H. (1983). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 11(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12331

- Patella, S. M., Sportiello, S., Petrelli, M., & Carrese, S. (2019). Workplace relocation from suburb to city center: A case study of Rome, Italy. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 7(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2019.04.009

- Pritchard, R., & Froyen, Y. (2019). Location, location, relocation: How the relocation of offices from suburbs to the inner city impacts commuting on foot and by bike. European Transport Research Review, 11(14), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12544-019-0348-6

- Rau, H., Popp, M., Namberger, P., & Mögele, M. (2019). Short distance, big impact: The effects of intra-city workplace relocation on staff mobility practices. Journal of Transport Geography, 79(August), 102483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102483

- Rives, J. M., & West, J. M. (1993). Wife’s employment and worker relocation behavior. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 22(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-5357(93)90003-4

- Salomon, I., & Ben-Akiva, M. (1983). The use of the life-style concept in travel demand models. Environment and Planning A, 15(5), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1068/a150623

- Schneider, R. J., & Willman, J. L. (2019). Move closer and get active: How to make urban university commutes more satisfying. Transportation Research Part F, 60, 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.11.001

- Schönfelder, S., & Axhausen, K. W. (2010). Time, space and travel analysis: An overview. In Urban rhythms and travel behaviour: Spatial and temporal phenomena of daily travel (1st ed., pp. 30–50). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.575076

- Sprumont, F. (2017). Activity-travel behaviour in the context of workplace relocation [doctoral dissertation]. University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg.

- Sprumont, F., Benam, A. S., & Viti, F. (2020). Short- and long-term impacts of workplace relocation: A survey and experience from the University of Luxembourg relocation. Sustainability, 12(18), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187506

- Sprumont, F., & Viti, F. (2018). The effect of workplace relocation on individuals’ activity travel behavior. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 11(1), 985–1002. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2018.1123

- Sprumont, F., Viti, F., Caruso, G., & König, A. (2014). Workplace relocation and mobility changes in a transnational metropolitan area: The case of the University of Luxembourg. Transportation Research Procedia, 4, 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2014.11.022

- St-Louis, E., Manaugh, K., van Lierop, D., & El-Geneidy, A. (2014). The happy commuter : A comparison of commuter satisfaction across modes. Transportation Research Part F, 26, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2014.07.004

- Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2004). Stress that doesn’t pay: The commuting paradox (Discussion Paper No. 1278; Issue 1278).

- Vale, D. S. (2013). Does commuting time tolerance impede sustainable urban mobility? Analysing the impacts on commuting behaviour as a result of workplace relocation to a mixed-use centre in Lisbon. Journal of Transport Geography, 32, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.08.003

- Veenhoven, R. (2012). Evidence based pursuit of happiness: What should we know, do we know and can we get to know? MPRA Paper, University Library of Munich, Germany.

- von Behren, S., Puhe, M., & Chlond, B. (2018). Office relocation and changes in travel behavior: Capturing the effects including the adaptation phase. Transportation Research Procedia, 32, 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2018.10.021

- Walker, I., Thomas, G. O., & Verplanken, B. (2015). Old habits die hard: Travel habit formation and decay during an office relocation. Environment and Behavior, 47(10), 1089–1106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916514549619

- Wang, F., Mao, Z., & Wang, D. (2020). Residential relocation and travel satisfaction change: An empirical study in Beijing. China. Transportation Research Part A, 135(April), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.03.016

- Wheatley, D. (2014). Travel-to-work and subjective well-being: A study of UK dual career households. Journal of Transport Geography, 39, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.07.009

- Wiersma, U. J. (1994). A taxonomy of behavioral strategies for coping with work-home role conflict. Human Relations, 47(2), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700204

- Yang, X., Day, J. E., Langford, B. C., Cherry, C. R., Jones, L. R., Han, S. S., & Sun, J. (2017). Commute responses to employment decentralization: Anticipated versus actual mode choice behaviors of new town employees in Kunming. China. Transportation Research Part D, 52(Part-B), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.11.012

- Ye, R., & Titheridge, H. (2017). Satisfaction with the commute: The role of travel mode choice, built environment and attitudes. Transportation Research Part D, 52, 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.06.011

- Zarabi, Z., Gerber, P., & Lord, S. (2019). Travel satisfaction vs. Life satisfaction: A weighted decision-making approach. Sustainability, 11(19), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195309

- Zarabi, Z., & Lord, S. (2019). Toward more sustainable behavior: A systematic review of the impacts of involuntary workplace relocation on travel mode choice. Journal of Planning Literature, 34(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412218802467

- Zax, J. S., & Kain, J. F. (1991). Commutes, quits, and moves. Journal of Urban Economics, 29(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/0094-1190(91)90010-5

- Zeng, W., Wu, Z., Schimmele, C. M., & Li, S. (2015). Mass relocation and depression among seniors in China. Research on Aging, 37(7), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027514551178