Abstract

Given the various motivational challenges that students experience when engaging in academic tasks, there is an emerging interest in investigating students’ cost perceptions and how to reduce them. However, most of the research has investigated general cost perceptions with a one-time assessment, often divorced from context in which cost is experienced. Centreing the situatedness of students’ motivational processes, we conducted an experience sampling study (57 undergraduates; 1,504 responses) to examine the link between general and in-situ momentary cost perceptions in students’ daily lives, as well as the potential moderating role of motivational regulation. Results showed that certain dimensions of momentary cost perceptions (outside effort cost and emotional cost) were positively associated with their corresponding general cost perceptions. Other dimensions of momentary cost (task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost) showed nonsignificant associations, suggesting higher sensitivity to context than others. Moreover, motivational regulation moderated the relationship between general and momentary cost for the majority of the dimensions, suggesting that interventions designed to improve students’ motivational regulation may reduce their momentary cost perceptions and increase the positivity of learning experiences.

Students often confront various motivational challenges while engaging in an academic task. For example, they may feel like the task requires too much effort, realize they must give up other alternative activities, or become stressed out. Recently, an interest has emerged in better understanding these types of cost perceptions (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020) and how to reduce the negative appraisals associated with engaging in a particular task (Rosenzweig et al., Citation2020). Addressing these cost perceptions is critical when considering students’ academic engagement, as they are associated with motivational and emotional experiences, engagement, and performance (Bergey et al., Citation2018; Jiang et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2022; Perez et al., Citation2014). However, most of the research has investigated general cost perceptions, measured with a single assessment that is often divorced from the specific context in which cost is experienced.

Drawing from situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983; Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020), we conducted an experience sampling study to capture students’ momentary cost perceptions in their daily lives and examine their associations with general cost perceptions. In addition, we integrated self-regulated learning perspectives (Pintrich, Citation2004; Zimmerman, Citation2000) to explore a potential mechanism that can reduce students’ momentary cost perceptions: motivational regulation. The motivational regulation literature suggests that students use specific strategies to deliberately increase their motivation (Wolters, Citation2003; Wolters & Benzon, Citation2013), which in turn increases effort, achievement, and well-being (Grunschel et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2018; Schwinger & Stiensmeier-Pelster, Citation2012). We thus explored whether motivational regulation supports students to perceive less momentary cost even after accounting for their general perceptions of cost.

Considering the multidimensionality of cost perceptions

According to situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983; Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020), students’ expectancies for success and task values dynamically interact with each other to determine their achievement-related choices, persistence, and achievement. Expectancies for success – which relate to the question of ‘can I do this?’ – refer to students’ competence beliefs about how well they will perform in a given task. Task values – which relate to the question of the question of ‘why do I want to do this?’ – refer to students’ perceptions regarding the importance (i.e. attainment value), usefulness (i.e. utility value), and interest (i.e. intrinsic value) of the task, as well as the associated costs of engaging in the task. Although a critical component of the situated expectancy-value theory, until recently, cost perceptions have received relatively little attention from researchers, thus necessitating further examination to develop comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the construct.

Cost was initially included in the Expectancy-Value theory by Eccles et al. (Citation1983) where they acknowledged that students perceive both benefits and costs while completing academic tasks. Additionally, they may use the cost/benefit ratio to make achievement-related decisions (e.g. whether to study for a test). By taking both positive and negative components of task values into account, researchers can better explore why, or why not, students are motivated to engage in a certain task. Although the initial conceptualization of cost included three dimensions such as effort cost, opportunity cost, and emotional cost, researchers have recently paid more attention to the operationalization and measurement of this multidimensional construct (e.g. Flake et al., Citation2015; Perez et al., Citation2014). In particular, Flake et al. (Citation2015) provided strong empirical evidence (e.g. focus group interviews with students, content review from experts, factor analyses, correlational analyses) to support four unique dimensions of cost: task effort cost refers to the negative appraisals of required time and effort to complete the academic task (e.g. ‘This task is too much work’); outside task effort cost refers to the negative appraisals of time and effort to complete tasks from other life domains (e.g. ‘I have too many commitments and responsibilities other than the task itself’); loss of valued alternatives cost refers to the negative appraisals resulting from the sacrifice of other attractive activities (e.g. ‘Doing this task means missing out on other things’); and emotional cost refers to the negative appraisals of psychological state or mental stress resulting from the task (e.g. ‘This task is stressful’).

Cost perceptions are salient to students, especially in less motivating environments, and they can have important implications. For example, students have described their experience with academic tasks as ‘too much’, ‘overwhelming’, or ‘stressful’ (e.g. Flake et al., Citation2015; p. 237). Unsurprisingly, such perceptions of cost are associated with various educational outcomes such as long-term interest, persistence, and performance (Flake et al., Citation2015; Watkinson et al., Citation2005). Even after accounting for expectancies and task values, perceiving high cost uniquely predicted students’ adoption of avoidance goals, negative affect, procrastination, dropout intentions, and poor achievement (Jiang et al., Citation2018; Perez et al., Citation2014). Moreover, the negative impact of cost on academic engagement was not buffered even when students reported high expectancies or task values (Kim et al., Citation2022). Overall, the pervasiveness of cost perceptions and their damaging consequences highlight the need to better understand how these negative perceptions occur in daily life.

In-situ cost perceptions

Cost perceptions are subjective perceptions of engaging in a task, which means that: 1) different students can have different perceptions of the same task, and 2) individual perceptions are dynamic and can change based on the context (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2022). Given that motivational beliefs are tied to their current time and space, we invoke the situative perspective to acknowledge the role of surrounding contexts in shaping students’ in-the-moment motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020; Nolen, Citation2020). Although the theory has been updated to ‘situated’ expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020), not enough empirical work examines the situatedness of students’ motivations, let alone their cost perceptions. Until now, researchers have largely focused on examining general perceptions of cost for academic tasks, which comes with the assumption that these general perceptions represent how students perceive cost in their daily lives. For example, cost has often been examined at the course- or domain-level (e.g. ‘Studying for my math class takes too much effort’) (Jiang et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2022; Perez et al., Citation2014; Watt et al., Citation2019). Although it is informative to understand whether students generally tend to perceive their academic activities (e.g. maths courses) as costly, this approach masks how cost perceptions fluctuate depending on specific tasks or contexts and does not capture the distinct dimensions of cost (Beymer et al., Citation2022; Feldon et al., Citation2019). Moreover, using prospective or retrospective self-reports of students’ general tendencies or motivational beliefs across various tasks may yield biased data. Paying attention to in-situ cost perceptions, which better align with the situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020), may more accurately capture the dynamic nature of motivational challenges that students experience in their day-to-day lives (Beymer et al., Citation2022).

Recently, researchers have made notable efforts to explore momentary motivational experiences (Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022; Dietrich et al., Citation2019; Kosovich et al., Citation2017). For example, Dietrich et al. (Citation2019) highlighted the situational heterogeneity in motivation by measuring in-situ motivation during 10 weekly lectures sections. They found that university students’ general perceptions of expectancies, task values, and costs for the subject area (measured at the beginning and end of the semester) were associated with their in-the-moment profiles of motivation during lectures (Dietrich et al., Citation2019). Relatedly, Benden and Lauermann (Citation2022) examined weekly motivational changes and discovered that students can experience a decline in utility and intrinsic values and an increase in costs at the beginning of the semester (i.e. between second and third week of the semester). These short-term motivational fluctuations are critical to consider as they can negatively affect more general, course-level outcomes such as achievement, persistence, and well-being (Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022; Kosovich et al., Citation2017).

Even though researchers have provided important insights on situational motivational profiles (Dietrich et al., Citation2019) and short-term motivational trajectories (Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022; Kosovich et al., Citation2017), we have much to learn about students’ motivation in-the-moment. For example, researchers have often included momentary expectancies and task values but excluded cost perceptions (e.g. Salmela-Aro et al., Citation2021) or used aggregated scores of overall cost perceptions instead of specific dimensions (e.g. Dietrich et al., Citation2019). In addition, students’ momentary motivation has often been measured weekly and only in academic settings (i.e. during class) to capture their perceptions towards course content specific to that week (e.g. Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022; Dietrich et al., Citation2019). Our study addresses these gaps in the literature by intentionally capturing specific dimensions of momentary cost in a more fine-grained manner (multiple times a day for a week) beyond classroom settings (both academic and non-academic contexts) and examining how these momentary cost perceptions are associated with students’ general cost perceptions.

Potential role of motivational regulation

Building upon recent research that has shown that cost perceptions are malleable and that targeted interventions can reduce maladaptive outcomes associated with cost perceptions (e.g. Rosenzweig et al., Citation2020, Citation2022), we investigate whether there are protective person-level mechanisms that can reduce their cost perceptions. Drawing from self-regulated learning theories, we propose that motivational regulation may serve as a support mechanism for students. Motivational regulation is a critical aspect of self-regulated learning (Wolters, Citation2003) that demonstrates a close connection with other regulatory processes (e.g. cognitive, behavioural, contextual regulation; Kim et al., Citation2020).

Students engage in various types of activities to regulate their motivation (Wolters & Benzon, Citation2013). A few examples include: enhancing interest, engaging in mastery self-talk, reflecting on task values, and setting proximal goals. Prior empirical evidence indicates that individuals have the power to initiate, maintain, and boost one’s motivation, thus leading to positive results (Grunschel et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2018; Schwinger & Stiensmeier-Pelster, Citation2012). For example, motivational regulation has been positively associated with efficacy beliefs, values, adoption of mastery goals, and use of learning strategies, and negatively associated with procrastination (Kim et al., Citation2018; Wolters & Benzon, Citation2013). Using a person-centered approach, Schwinger et al. (Citation2012) added that students who reported higher overall levels of motivational regulation showed higher levels of effort and achievement.

Although motivational regulation has been positively associated with various educational outcomes (Grunschel et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2018; Schwinger et al., Citation2012; Schwinger & Stiensmeier-Pelster, Citation2012; Wolters & Benzon, Citation2013), less is known about its potential link with cost perceptions. Conceptually, Wolters (Citation2003) suggests that students can strategically monitor and control their own motivation in the face of specific motivational challenges. Miele and Scholer (Citation2018) also proposed that students can engage in motivational regulation to address different dimensions of costs. Considering that perceiving learning activities as costly can be an important motivational challenge, we sought to provide initial empirical evidence regarding whether students’ general motivational regulation tendencies can reduce specific dimensions of momentary cost perceptions in everyday life. Motivational regulation was operationalized as the ways in which students "purposefully act to initiate, maintain, or supplement their willingness to start, to provide work toward, or to complete a particular activity or a goal" (Wolters, Citation2003, p. 190). As we were interested in the role of motivational regulation as a protective person-level mechanism, we specifically focused on capturing students’ general tendencies to regulate their own motivation instead of specific use of strategies.

Present study

Using an experience sampling method (ESM; Csikszentmihalyi et al., Citation1977), we examined how specific dimensions of general cost perceptions were associated with specific dimensions of momentary cost perceptions (RQ1). We hypothesized that each of the four general cost dimensions (i.e. task effort cost, outside effort cost, loss of valued alternatives cost, emotional cost) would be linked to the corresponding momentary cost dimensions. In addition, we examined whether motivational regulation can moderate the impact of general cost perceptions on momentary cost perceptions (RQ2). We hypothesized that motivational regulation would be able to buffer momentary cost perceptions even after controlling for general cost perceptions.

Method

Participants

Participants were 57 university students (Mage = 20.2 years) from a mid-sized Midwestern University in United States. The participants’ self-reported gender included White (40.4%), Asian (42.1%), Black (14.0%), Hispanic (10.5%), and other (1.8%). Participants identified themselves as female (77.1%), male (19.3%), and other (7%). The participants were from various fields of study including science, technology, engineering, maths (STEM; 40.4%), social sciences (38.6%), humanities (7.0%), fine arts (1.8%), and other (12.3%). Among the participants, 14.0% identified themselves as first-generation college students.

Procedures and measures

After being informed about the study and signing the consent form, participants completed self-report surveys as part of a larger project designed to assess students’ motivational and emotional experiences. In particular, participants first reported their general cost perceptions for studying and general tendency to engage in motivational regulation through a one-time pre-survey. After a week, participants engaged in the ESM procedure and shared their momentary cost perceptions in naturalistic settings. Five signals (i.e. text messages with a link to the survey) were sent each day at random intervals for a week. To ensure capturing participants’ responses at the moment, the links were set to expire after 30 minutes. In an effort to minimize intrusiveness, we asked the participants to select whether they preferred that the signals be sent earlier in the day (i.e. 7am to 10 pm; n = 14) or later in the day (i.e. 9am to midnight; n = 43). The participants received gift cards based on their level of participation. Further details about the measures and their internal reliability from the current sample (i.e. Cronbach’s α) are provided below.

Cost perceptions

General cost perceptions

Participants reflected on their general cost perceptions for academic tasks using the cost scale developed by Flake et al. (Citation2015). This scale has been validated with rigorous, multi-phrase process (e.g. content alignment with experts, factor analyses, qualitative and correlational studies; Flake et al., Citation2015), and has often been used in prior literature to measure college students’ cost perceptions (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2021; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2020). This 19-item scale consisted of four dimensions of cost: task effort cost (e.g. ‘Studying requires too much effort’; 5 items; α = .91); outside effort cost (e.g. ‘Because of all the other demands on my time, I don’t have enough time for studying’; 4 items; α = .93); loss of valued alternatives cost (e.g. ‘I have to sacrifice too much to study’; 4 items; α = .88); and emotional cost (e.g. ‘Studying is emotionally draining’; 6 items; α = .92). All items were measured on a 9-point Likert scale (from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’).

Momentary cost perceptions

In the ESM portion of the data collection procedure, participants reported their momentary cost perceptions for studying by using items from the validated short-scale version of the cost scale (Beymer et al., Citation2022). Beymer et al. (Citation2022) specifically focused on developing and validating a short version of the general cost scale (Flake et al., Citation2015) so that researchers could use the short scale for intensive longitudinal methods such as our use here with ESM. This 4-item scale included one item from each of the four dimensions of cost which was helpful in capturing the multi-dimensions of cost. Importantly, with this short scale, participants only need to answer a small number of items to minimize survey fatigue from repeated measures of the same scale. We adapted these four items to specifically tap into their momentary experiences by adding ‘In this moment, I think that…’. We used 9-point Likert scale with 1 indicating ‘completely disagree’ and 9 indicating ‘completely agree’ (α = .85).

Motivational regulation

Participants indicated their general motivational regulation tendencies using the Brief Regulation of Motivation Scale (BRoMS; Kim et al., Citation2018). BRoMS has been previously validated as an instrument that provides a unidimensional indicator of college students’ general tendencies to manage and control their motivation in the face of motivational challenges (Kim et al., Citation2018). More recent work has also shown strong validity of this scale with college students (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2020; Wolters et al., Citation2023). The scale included eight items (α = .72) and a sample item was, ‘I use different tricks to keep myself working, even if I don’t feel like studying’. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’).

Analytical approach

We used multilevel modelling to account for the nested data structure and the within subjects repeated measures. All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, Citation2022) version 4.2.2 using the lme4 package version 1.1.33 (Bates et al., Citation2015) and the lmerTest package version 3.1.3 (Kuznetsova et al., Citation2017). For the first research question, we examined the extent to which variations in momentary cost perceptions are associated with general cost perceptions. Specifically, we tested whether the four dimensions of general cost (level one variables) predicted each momentary cost dimension, running one model for each momentary cost dimension. For these four models, we nested responses within students as each student had multiple responses and the signal time as students responded across a series of signals across time. For the second research question, we included motivational regulation as a moderator to examine whether it buffers students’ momentary cost perceptions even after accounting for their general cost perceptions. Again, we ran four models, one for each dimension of momentary cost. Each model included the corresponding dimension of general cost, motivational regulation, and the interaction between the two predictors. We also included student and signal time as level two nesting variables. To visualise the interactions, we plotted them using ggeffects package version 1.2.2 (Lüdecke, Citation2018). For both sets of models, we included the estimates and standardized estimates. We also provide the R2 for the overall model and the marginal R2 for each independent variable using the 2glmm package version 0.1.2 (Jaeger, Citation2017).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Participants generated a total of 1,504 responses for the experience sampling surveys, and the overall response rate was 75.39% (range: 15-100%), which aligns with the prior literature (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, Citation2014). Over half of the participants reported that they had a ‘typical’ week of the semester (54%), other participants reported that they had more or less work to do than normal (26% and 12% respectively), and a few participants reported that they experienced an unexpected event (7%). Descriptive statistics for the key variables are summarized in . Person-level variables were collected from the pre-survey measures (i.e. general perceptions) and situation-level variables were collected from the experience sampling survey measures (i.e. momentary perceptions). Interestingly, for both general and momentary cost perceptions, task effort cost and emotional cost were higher than outside effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of key variables.

The associations between general cost perceptions and momentary cost perceptions

To examine whether general cost perceptions (the person-level) were related to momentary cost perceptions (the situation-level) in daily life (RQ1), we applied a set of multilevel models and accounted for the repeated measures of momentary cost. We used one model for each dimension of momentary cost perceptions (i.e. task effort cost, outside effort cost, loss of valued alternatives cost, emotional cost), resulting in four separate models. All of the models contained the same set of independent variables (the four dimensions of general cost perceptions) which were entered as fixed effects. We also included student and signal time as random intercepts. See for the model results.

Table 2. Associations between general cost perceptions and momentary cost perceptions.

Across the four models, the corresponding general cost dimension was positively associated with its momentary cost dimension, and no other general cost dimensions were related. Momentary outside effort cost was positively related to general outside effort cost (B = 0.25, p = .02, Marginal R2 = .06) and momentary emotional cost was positively related to general emotional cost (B = 0.54, p < .001, Marginal R2 = .17). Momentary task effort cost and momentary loss of valued alternatives cost had trending, although nonsignificant, associations with their corresponding general cost perceptions (B = 0.34, p = .07, Marginal R2 = .05 and B = 0.26, p = .07, Marginal R2 = .05, respectively). These results suggest that momentary task effort cost and momentary loss of valued alternatives cost dimensions might be relatively more sensitive to a particular task and context than momentary outside effort cost and momentary emotional cost, which appear to be more stable.

The moderating role of motivational regulation on momentary cost perceptions

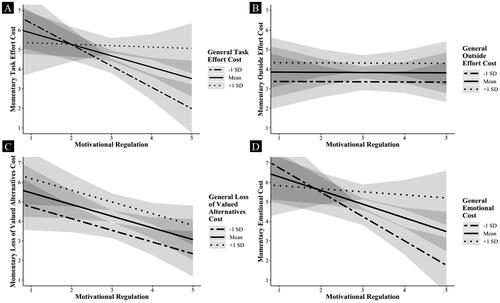

Next, we examined how each dimension of momentary cost perceptions were related to motivational regulation after accounting for the corresponding dimension of general cost perceptions. We were particularly interested in potential interactions between general cost perceptions and motivational regulation, as it would indicate whether motivational regulation plays a role in buffering the effects of general cost perceptions on momentary cost perceptions. We again applied a set of multilevel models to account for the repeated measures of momentary cost within persons. Similar to RQ1, we used one model for each dimension of momentary cost perceptions (i.e. task effort cost, outside effort cost, loss of valued alternatives cost, emotional cost). We first entered three independent variables as fixed effects (the corresponding dimension of general cost perceptions, motivational regulation, and the interaction between general cost perceptions and motivational regulation) into the models with the random intercepts of student and signal time. When the interaction was not significant for a model, we removed the interaction term in accordance with the parsimony principle (i.e. removing parameters that do not contribute to the explanatory power of the model). See and for the model results.

Figure 1. The interaction between general cost perceptions and motivational regulation on momentary cost perceptions.

Note. Gray bands signify 95% confidence intervals of the estimates. Graphs A and D display significant interactions (p < .05) between motivational regulation and the respective general dimension of cost. A coloured version can be viewed in the Supplemental Materials.

Table 3. Associations between general cost perceptions, motivational regulation, and momentary cost perceptions.

Results from the multilevel models showed that for momentary task effort cost and emotional cost (models 1 and 4), there was a significant interaction between their corresponding general cost perceptions and motivational regulation (B = 0.42, p = .03, Marginal R2 = .05, and B = 0.39, p = .04, Marginal R2 = .06, respectively). As seen in (graphs A and D), motivational regulation reduced students’ momentary task effort cost and emotional cost perceptions, but this did not occur when their respective general cost perceptions were high. In other words, motivational regulation appears to be able to buffer the effects of general cost perceptions but not when students generally perceive a task to be too costly.

For momentary outside effort cost (model 2), there was only a main effect of the corresponding general cost perception (B = 0.33, p = .002, Marginal R2 = .12) (graph B in ). For momentary loss of valued alternatives cost (model 3), there were main effects of both the corresponding general cost perception (B = 0.54, p < .001, Marginal R2 = .28) and motivational regulation (B = −0.60, p = .04, Marginal R2 = .07). In this case, motivational regulation reduced momentary loss of valued alternatives cost regardless of the level of general loss of valued alternatives cost (graph C in ).

Discussion

Using an experience sampling method, this study generates novel insights by capturing the dynamic nature of motivational challenges that students experience in their day-to-day lives beyond classroom settings. This approach allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of how cost functions in the moment in authentic surroundings. Our findings also highlighted the importance of examining specific dimensions of cost (i.e. task effort cost, outside task effort cost, loss of valued alternatives cost, emotional cost), as they demonstrated differential relationships. We found that for some dimension of cost, students’ general cost perceptions (measured at one time in a pre-survey) predicted their corresponding momentary experiences of cost in daily life (measured five times a day for seven consecutive days). Moreover, motivational regulation was able to buffer students’ momentary perceptions of particular cost dimensions in daily life, although the associations varied depending on the specific dimension of cost. Below we discuss the major findings with regards to the theoretical contributions and the practical implications.

Linking specific dimensions of momentary and general cost perceptions

Our work contributes to the literature by linking the specific dimensions of cost across general and in-situ momentary cost perceptions and providing initial evidence for the associations between them. The majority of studies examining students’ cost perceptions have mainly focused on capturing the general level of cost, often with a one-time measure and focusing on a single academic domain or course (Jiang et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2022; Perez et al., Citation2014; Watt et al., Citation2019). This approach, while valuable, does not incorporate the temporal and contextual specificity of students’ experiences (Pekrun & Marsh, Citation2022). By collecting and analyzing intensive longitudinal data, we were able to examine students’ cost perceptions in a more detailed, relevant, and context-specific manner, which also ensured ecological validity. Rather than only measuring students’ cost perceptions at the person-level, we also measured them at situation-level to capture them as dynamic momentary processes, situated in a specific time and context. Additionally, our findings indicate that researchers need to consider the specific dimensions of cost perceptions. Prior to the introduction of validated cost measures (e.g. Flake et al., Citation2015; Perez et al., Citation2014), researchers often used a few items that represented only one or two dimensions of cost (e.g. Conley, Citation2012; Trautwein et al., Citation2012). Researchers still often collapse the construct into a general conception of cost even when they measure different dimensions of cost. However, to gain a more nuanced understanding, it is important to take the multidimensionality of cost into account and evaluate the specific dimensions in the measurements and analyses.

In this study, we found that each of the four dimensions of momentary cost perceptions operates in a unique manner, leading to differential relations with general cost perceptions (). For example, although outside effort cost and emotional cost showed significant relationships with their corresponding general cost perceptions, momentary task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost only showed trending relationships with their corresponding general cost perceptions. These findings suggest that certain dimensions of momentary cost show greater sensitivity to context (task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost) while others show greater stability across contexts (outside effort cost and emotional cost). A potential explanation for this divergence might involve the nature of each cost dimension. Students’ perceptions of task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost could be more task-dependent and situative in nature (e.g. required time and effort for the current task, feelings of giving up other opportunities to engage in the current task) than outside effort cost and emotional cost. Outside effort cost could be more task-irrelevant as it taps into the responsibilities and commitments that students have to take care of regardless of the current task (e.g. an outside job, caring for a family member). Similarly, emotional cost could also be more pervasive in their daily life given all the tasks they have to balance as well as the heightened stress that college students experience.

Notably, the relation between general and momentary cost was the strongest (i.e. highest effect size) for emotional cost while other cost dimensions demonstrated weaker (i.e. outside effort cost) to no associations (i.e. task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives cost). Interestingly, the average level of emotional cost was the highest among the four dimensions of cost, revealing that students’ perceptions of emotional cost for academic tasks were highly salient in their daily life, providing less room to fluctuate. According to a recent statistical report from American Psychological Association (Citation2020), 87% of college students reported that education was a significant source of mental stress for them. Reflecting the growing concerns for student academic stress, anxiety, and burnout, it is critical to address their emotional cost perceptions towards academic activities. Some potential approaches may include implementing emotional regulation interventions (e.g. Rozek et al., Citation2019) and mindfulness-based meditation programs (Bamber & Schneider, Citation2016).

Overall, our findings partially support the prior literature that suggests situational costs might be less likely to change while situational expectancies and values might be relatively more likely to change (Dietrich et al., Citation2019). When students reported their motivation for the course once a week for 10 consecutive weeks across the semester (i.e. each week’s lecture content), they tended to demonstrate a change in their motivational profile with either higher or lower levels of expectancies and values but similar perceptions of cost (Dietrich et al., Citation2019). In another study that captured weekly fluctuations of cost perceptions, Benden and Lauermann (Citation2022) found that students experienced a "motivational shock" at the beginning of the semester (i.e. between second and third week) where they showed an increase in cost and decrease in self-efficacy and task values (p. 1076, Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022). In the present study, we found positive associations for some dimensions of momentary and general cost perceptions, demonstrating the general stability of students’ cost perceptions for certain cost dimensions but not for others. That is, for outside effort and emotional cost perceptions, students’ general perceptions of cost towards studying mattered in determining how costly studying can feel like in their day-to-day lives. However, there was not an association between the general and momentary dimensions of task effort cost and loss of valued alternatives. These nuanced results indicate that certain cost dimensions may be more stable whereas others may be situative and malleable. Additionally, since we measured cost multiple times within a typical week of the semester, future work could explore whether a different relationship emerges during this "motivational shock" period when motivation may be more malleable (Benden & Lauermann, Citation2022).

Motivational regulation is helpful – but not always

Another focus of our study was to explore whether motivational regulation can serve as a moderator to buffer momentary cost perceptions even after accounting for general cost perceptions. We found different results based on the specific dimensions of cost. For momentary task effort cost and emotional cost, motivational regulation significantly interacted with general cost perceptions. Although motivational regulation can support students to perceive less momentary task effort cost and emotional cost, it became less effective when students generally perceived their academic tasks as too costly. The higher a student’s general cost perceptions, the less able motivational regulation was to buffer their effects and reduce students’ momentary task effort and emotional cost perceptions. Thus, in addition to teaching students how to monitor and regulate one’s own motivation, students may benefit by participating in interventions directly targeting their general cost perceptions. Recently, researchers have made promising efforts in developing cost reduction interventions where students reflect on how they can overcome course challenges and reframe their perceived costs by building positive attitudes towards the course (Rosenzweig et al., Citation2020).

Notably, the interaction between motivational regulation and general cost perceptions were not found for the other two momentary cost dimensions (i.e. loss of valued alternatives cost, outside effort cost). For momentary loss of valued alternatives cost, motivational regulation was able to reduce momentary cost perceptions regardless of students’ general cost perceptions as shown with the main effect of motivational regulation. Prior research indicates that students feel tempted to engage in other activities when their attractiveness exceeds that of the current academic task (Hofer, Citation2007). Thus, one explanation for our results is that when students’ motivation for the current task can be enhanced by successful motivational regulation, they are relatively less tempted to engage in other activities. Our findings suggest that supporting students to monitor and control their own motivation can help them to avoid the feelings of missing out or sacrificing other activities.

In contrast, motivational regulation did not reduce students’ momentary outside effort cost regardless of students’ general cost perceptions. As we discussed in the previous section, outside effort cost refers to the commitments or responsibilities that students have apart from the academic task at hand. As motivational regulation directly focuses on maintaining and increasing motivation for the academic tasks, it may not have a significant impact on students’ momentary outside effort cost perceptions (which are likely less malleable). This finding implies that both researchers and practitioners should consider the broader context in addition to the academic tasks. Various responsibilities and goals that students have outside of the classroom may greatly impact students’ engagement in the academic task. For example, many students are employed, either part-time or full-time, or participate in various internship opportunities or training programs to address financial difficulties or to gain work experience during college (National Center for Education Statistics, Citation2022). As students devote a number of hours to their work every week, many students inevitably face challenges in juggling their academic activities and other commitments. It is critical to acknowledge that students have lives outside of the classroom and provide relevant support to encourage their continued engagement (Kim et al., Citation2023).

Limitations and future directions

The present study is an initial step in investigating how different dimensions of cost operate, as well as the antecedents that can predict or moderate their impact on students’ learning experiences. Thus, this work can serve as a springboard for future work to examine the generalizability and impact of these relationships. First, the directionality between general and momentary perceptions can be further investigated as they are likely to be bidirectional. Future studies should investigate whether momentary cost perceptions also contribute to shaping students’ future general cost perceptions or motivational regulation tendencies in upcoming academic activities. Second, although we measured students’ general tendencies to regulate their motivation to investigate a potential person-level protective mechanism, it would be important to acknowledge the situative nature of motivational regulation as well. Students’ engagement in different types of motivational regulation strategies may also vary depending on the context, and thus, future endeavours should explore students’ momentary motivational regulation. Finally, our study only includes students’ self-reported perceptions. Researchers could leverage behavioural measures to investigate other potential antecedents (e.g. prior course enrollments) to momentary cost perceptions and the impact of those perceptions on student outcomes (e.g. persistence in a course).

Practical implications

On a practical level, these findings highlight the importance of developing motivational regulation while also addressing students’ negative perceptions towards academic tasks. Especially because the dimensions of cost may operate differently, educators should be sensitive and responsive to various negative appraisals that students may bring to the classroom. For example, educators will be better able to support students if they understand why students perceive their academic tasks as costly – whether it is required effort, other commitments, feelings of missing out, or associated stress. Although enhancing students’ capabilities to monitor and regulate their own motivation can help, this approach may not always lower students’ cost perceptions. Thus, educators should also consider directly targeting students’ cost perceptions and supporting students to build positive perceptions of their learning activities.

Conclusions

Given that motivational challenges are often salient and potentially detrimental to students, it is critical to understand the cost perceptions that students hold towards their academic tasks. Our findings show that students’ general cost perceptions are related to their in-situ motivational experiences in their daily lives. Thus, identifying students’ general cost perceptions early in the semester and offering targeted interventions would be helpful for students to perceive less momentary cost perceptions. We also demonstrated that motivational regulation moderates the relationship between students’ general and momentary cost perceptions for particular cost dimensions. That is, supporting students to regulate their motivation can help them perceive less momentary cost (specifically task effort cost, loss of valued alternatives cost, and emotional cost), especially when students do not generally perceive their academic tasks as too costly.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the idea of the research and generated the design of the study. YK led the data collection process. YK, CDZ, and RSM analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (187.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Stress in America 2020: A national mental health crisis. APA.

- Bamber, M. D., & Schneider, J. K. (2016). Mindfulness-based meditation to decrease stress and anxiety in college students: A narrative synthesis of the research. Educational Research Review, 18, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.004

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Benden, D. K., & Lauermann, F. (2022). Students’ motivational trajectories and academic success in math-intensive study programs: Why short-term motivational assessments matter. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 1062–1085. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000708

- Bergey, B. W., Parrila, R. K., & Deacon, S. H. (2018). Understanding the academic motivations of students with a history of reading difficulty: An expectancy-value-cost approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.06.008

- Beymer, P. N., Ferland, M., & Flake, J. K. (2022). Validity evidence for a short scale of college students’ perceptions of cost. Current Psychology, 41(11), 7937–7956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01218-w

- Conley, A. M. (2012). Patterns of motivation beliefs: Combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026042

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (2014). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. In M. Csikszentmihalyi (Ed.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 35–54). Springer.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Larson, R., & Prescott, S. (1977). The ecology of adolescent activity and experience. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 6(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02138940

- Dietrich, J., Moeller, J., Guo, J., Viljaranta, J., & Kracke, B. (2019). In-the-moment profiles of expectancies, task values, and costs. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01662

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

- Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives (pp. 75–146). Freeman.

- Feldon, D. F., Callan, G., Juth, S., & Jeong, S. (2019). Cognitive load as motivational cost. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09464-6

- Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.002

- Grunschel, C., Schwinger, M., Steinmayr, R., & Fries, S. (2016). Effects of using motivational regulation strategies on students’ academic procrastination, academic performance, and well-being. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.008

- Hofer, M. (2007). Goal conflicts and self-regulation: A new look at pupils’ off-task behaviour in the classroom. Educational Research Review, 2(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2007.02.002

- Jaeger, B. (2017). r2glmm: Computes R Squared for Mixed (Multilevel) Models_. R package version 0.1.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=r2glmm

- Jiang, Y., Rosenzweig, E. Q., & Gaspard, H. (2018). An expectancy-value-cost approach in predicting adolescent students’ academic motivation and achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.005

- Kim, Y., Brady, A. C., & Wolters, C. A. (2018). Development and validation of brief scale for motivational regulation. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.12.010

- Kim, Y., Brady, A. C., & Wolters, C. A. (2020). College students’ regulation of cognition, motivation, behavior, and context: Distinct or overlapping processes? Learning and Individual Differences, 80, 101872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101872

- Kim, Y., Yu, S. L., Koenka, A. C., Lee, H. W., & Heckler, A. F. (2022). Can self-efficacy and task values buffer perceived costs? Exploring introductory- and upper-level physics courses. The Journal of Experimental Education, 90(4), 839–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2021.1878992

- Kim, Y., Yu, S. L., Wolters, C. A., & Anderman, E. M. (2023). Self-regulatory processes within and between diverse goals: The multiple goals regulation framework. Educational Psychologist, 58(2), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2158828

- Kosovich, J. J., Flake, J. K., & Hulleman, C. S. (2017). Short-term motivation trajectories: A parallel process model of expectancy-value. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.004

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

- Lee, H., Yu, S. L., Kim, M., & Koenka, A. C. (2021). Concern or comfort with social comparisons matter in undergraduate physics courses: Joint consideration of situated expectancy-value theory, mindsets, and gender. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 67, 102023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.102023

- Lüdecke, D. (2018). ggeffects: Tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(26), 772. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00772

- Miele, D. B., & Scholer, A. A. (2018). The role of metamotivational monitoring in motivation regulation. Educational Psychologist, 53(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1371601

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). College student employment. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/ssa

- Nolen, S. (2020). A situative turn in the conversation on motivation theories. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101866

- Pekrun, R., & Marsh, H. W. (2022). Research on situated motivation and emotion: Progress and open problems. Learning and Instruction, 81, 101664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101664

- Perez, T., Cromley, J. G., & Kaplan, A. (2014). The role of identity development, values, and costs in college STEM retention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034027

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Rosenzweig, E. Q., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2022). Beyond utility value interventions: The why, when, and how for next steps in expectancy-value intervention research. Educational Psychologist, 57(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2021.1984242

- Rosenzweig, E. Q., Wigfield, A., & Hulleman, C. S. (2020). More useful or not so bad? Examining the effects of utility value and cost reduction interventions in college physics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(1), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000370

- Rozek, C. S., Ramirez, G., Fine, R. D., & Beilock, S. L. (2019). Reducing socioeconomic disparities in the STEM pipeline through student emotion regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(5), 1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808589116

- Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Cumsille, P., Lavonen, J., Avalos, B., & Eccles, J. (2021). Momentary task‐values and expectations predict engagement in science among Finnish and Chilean secondary school students. International Journal of Psychology : Journal International de Psychologie, 56(3), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12719

- Schwinger, M., Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2012). Not all roads lead to Rome—Comparing different types of motivational regulation profiles. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.12.006

- Schwinger, M., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2012). Effects of motivational regulation on effort and achievement: A mediation model. International Journal of Educational Research, 56, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.07.005

- Trautwein, U., Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Ludtke, O., Nagy, G., & Jonkmann, K. (2012). Probing for the multiplicative term in modern expectancy–value theory: A latent interaction modeling study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 763–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027470

- Watkinson, E. J., Dwyer, S. A., & Nielsen, A. B. (2005). Children theorize about reasons for recess engagement: Does expectancy-value theory apply? Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 22(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.22.2.179

- Watt, H. M., Bucich, M., & Dacosta, L. (2019). Adolescents’ motivational profiles in mathematics and science: Associations with achievement striving, career aspirations and psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00990

- Wolters, C. A. (2003). Regulation of motivation: Evaluating an underemphasized aspect of self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3804_1

- Wolters, C. A., & Benzon, M. B. (2013). Assessing and predicting college students’ use of strategies for the self-regulation of motivation. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81(2), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2012.699901

- Wolters, C. A., Iaconelli, R., Peri, J., Hensley, L. C., & Kim, M. (2023). Improving self-regulated learning and academic engagement: Evaluating a college learning to learn course. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102282

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Theory, research, and applications. (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.