Abstract

The occupational safety and health (OSH) coordinator is an important figure for improving OSH in the construction industry. Working as an OSH coordinator is complicated, and coordinators must attend to many different roles to improve OSH. Recent research has even questioned the effectiveness of OSH professional practice. This points to a need to understand how OSH coordinators position themselves in relation to different roles when performing effective OSH coordination. This study aims to expand upon this question by analyzing how OSH coordinators position themselves in situations leading to the implementation of OSH measures. In the study, practices of OSH coordinators in the Danish construction industry are analyzed by “zooming in” on micro-sociological positioning practices observed during 107 days of ethnographic fieldwork, e.g. speech acts, and by “zooming out” on the links between these positioning practices and the implementation of OSH measures. The study contributes to OSH research and practice in several ways; firstly, the study conceptualizes a typology of practices connected to the relational roles of OSH professionals. Secondly, it expands upon how negotiating for the implementation of OSH measures is a relationally complex matter in which OSH coordinators switch between positioning themselves as alliance builders, authorities, challengers, experts, influencers, and champions. Improving attention and education to accommodate this knowledge may contribute to the creation of more tangible borders around the OSH professional practice, and more impactful OSH practice in terms of implementing measures.

Keywords:

Introduction

Western society has pursued a strategy of improving OSH in organizations by urging companies to seek professional advice and competence in the battle against the negative health effects of work. This advice helps companies adhere to legislation and to design, implement and maintain strategies concerning OSH (Hale Citation1995, Pryor et al. Citation2019). This is also true for the construction industry—an industry infamous for being one of the most hazardous industries to work in (Swuste et al. Citation2012). The service of providing this advice and competence is undertaken by OSH professionals, and within the construction industry, the OSH coordinator fills an increasingly central role as an OSH professional.

The rise of OSH coordination in Denmark and the EU has its foundation in EU legislation. Through directive 92/57/EEC of 1992, OSH coordination became a prime tool in political initiatives seeking to improve health and safety among construction workers. In brief, the OSH coordinator is appointed to coordinate OSH at sites with more than one employer present (Aulin and Capone Citation2010). The OSH coordinator is responsible for ensuring cooperation between employers in matters of OSH and for ensuring that employers apply the general prevention principles. The coordinator may be employed by the client, the contractor, or as an external OSH advisor. In any case, depending on the specific construction project, the coordinator must, in legislative terms, “act on behalf of the client”. The central role of OSH coordinators in improving OSH in the construction industry is evident from the sheer number that, in 2019, 1207 people completed the mandatory one-week training course to become a certified OSH coordinator in Denmark. This is a number equal to that of the previous three years (The Danish Evaluation Institute (Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut) Citation2020).

In recent research, the complexity of the roles of OSH coordinators (Møller et al. Citation2020) and of OSH professionals in general (Provan et al. Citation2017), have been pointed out. In practice, there is some debate, and little consensus, on what the boundaries for OSH coordination are, and what constitutes the core tasks and roles of coordinators. This is a challenge for OSH coordinators, who have to navigate many different roles in relation to different stakeholders and face a lack of organizational knowledge about, and trust in, their skills, as well as a lack of compliance with their recommendations (Antonio et al. Citation2013, Provan et al. Citation2017). To make matters even more complicated, the effectiveness of OSH coordinator practice has been questioned for making a doubtful contribution to improve OSH, with researchers pointing instead to legislation and inspection as effective ways of improving OSH (Andersen et al. Citation2019). As Provan et al. (Citation2019) also write; “Organizations may have noticed this lack of impact that safety professionals are having on safety performance” (p. 286). These issues point to a need to understand how OSH coordinators position themselves in relation to different roles when performing effective OSH coordination. This focus can provide a valuable contribution to the debate about OSH coordinator tasks and it can also address the critiques above, as well as provide paths for increasing the impact of OSH coordination on OSH in the construction sector.

To understand how OSH coordinators position themselves to obtain impactful practice, this study draws upon existing literature on OSH professionals to develop a typology concerning the relational roles of OSH coordinators (roles they take up in interaction with different stakeholders). The study then investigates how coordinators take up these relational roles through positioning practices employed by coordinators in situations where they contribute to the implementation of OSH measures. The empirical material for the analysis was produced by shadowing (Czarniawska Citation2007) 12 OSH coordinators working in the Danish construction industry in an ethnographic study. Analytically, the study employs a “zooming-in” (Nicolini Citation2013) on the positioning practices that OSH coordinators conduct in micro-sociological interactions and which later lead to the implementation of OSH measures—identified by a “zooming-out” of implemented OSH measures identified in the field notes (Nicolini Citation2013).

The study is the first to expand upon how OSH coordinators position themselves when implementing OSH measures. It contributes to the emerging field of OSH coordination in the construction sector by clarifying and exemplifying positioning practices and by specifying how managing to implement OSH measures is actually a complex relational process for coordinators, requiring a resourceful switching between roles as situations unfold. This further suggests that the ability to position one’s self in relation to situation-appropriate roles may be developed and honed by coordinators to achieve a greater impact on OSH. This knowledge is highly useful to OSH coordinators and construction clients seeking to ensure effective OSH practices, and to researchers interested in OSH coordination, practices, and management within the construction industry. Indeed, increasing the effectiveness of OSH coordination may in turn assist in addressing the critiques of OSH coordination as well as improving OSH for construction workers.

The OSH coordinator—an OSH professional

OSH coordinators in Denmark fill many roles that also characterize OSH professionalism broadly. Just as other OSH professionals, coordinators fill institutional roles by helping clients adhere to legislation and standards (Olsen Citation2012), by checking compliance with policy, and by performing both risk assessments and safety and incident analyses (Hale and Guldenmund Citation2006). OSH coordinators also lead safety meetings and walks, and they communicate and negotiate on-site OSH initiatives with stakeholders, such as client representatives and advisors, various different contractors, designers and planners, project and site managers, supervisors, and workers. However, some coordinators also fill more strategic roles, developing safety bureaucracy, audit systems, and coordinating safety culture initiatives and similar, across the organizations of clients, advisory companies, or contractors, respectively. While the “role” concept was prominent in early interaction research (Goffman Citation1982) and has made its way into OSH research (Hale Citation1995, Provan et al. Citation2017), it has been criticized for leading to static or even “transcendent” categories that do not account for the complexities of social interaction. Instead, it has been suggested that people inscribe themselves into subject positions through discursive practices, which cover all the ways in which people actively produce social and psychological realities (Davies and Harré Citation1999). Within this emergent production of realities, people make sense of situations based on indexical extensions (past experiences) and typification extensions (culturally well-established clusters of attributes tied to particular categories: mother, manager, worker, different roles, etc.). While this study adheres to the concept that professional selves are negotiated through subject positioning in discursive practices, we also accept that existing literature has been concerned with the “roles” that OSH professionals fill. With the ambition of understanding how OSH coordinators position themselves in situations where they manage to impact OSH, it, therefore, makes sense to investigate what “roles” have been described to identify the extensions that coordinators make.

The relational roles of OSH coordinators and the need to understand practice

Provan et al. (Citation2017) suggest that OSH professionals orient toward four different relational roles (summarized in ). These are the OSH professional, firstly, as an alliance builder, constructing alliances with workers on the site as well as managers at the site, line, and senior levels. Secondly, as an influencer, able to use their alliances and employ legitimacy-building tactics as a means of improving OSH work. Thirdly, as a challenger, speaking up to address OSH issues or acting as a constructive enquirer or whistleblower. Finally, they can also act as an authority, finding a role and a way of gaining traction in the organization.

Table 1. The relational roles and associated practices of OSH professionals.

On the topic of alliance building, it was suggested, as far back as 1995, that OSH professionals should create relations in the whole organization in which they function (Hale Citation1995). Theberge and Neumann (Citation2010) suggest five strategies for OSH professionals to build alliances in organizations: identify the interests of others, identify the possible merging of goals, pay attention to informal relationships, implement arrangements aimed at improving relationships, and implement activities and tools that fit with existing management systems. Several studies have pointed out that part of the alliance-building process for OSH professionals relates to becoming partners with, rather than acting as police officers toward, workers and management (Hale Citation1995). As Oswald et al. point out, this is particularly important in the construction industry, where safety dialogue and proactive practices may be hampered by an adverse relationship between safety managers, managers, and workers (Oswald et al. Citation2018). Both Manuele (Citation2003) and Woods (Citation2006) clarify that OSH professionals should contribute toward effectively and economically reducing risks, by suggesting OSH solutions while working to achieve all of the organization’s goals.

Building alliances may indeed be important to OSH coordinators. In comparison with OSH professionals in more permanent organizations, coordinators in the construction industry often engage with multiple organizations in the temporary organization of the construction project, in contexts where management, entrepreneurs, and the coordinator may all be from different firms. Furthermore, coordinators often practice their work at several sites at a time. This may put particular demands on OSH coordinators and create particular conditions for their opportunities to position themselves as alliance builders.

On the topic of influencing, Broberg and Hermund (Citation2007) describe the importance of OSH professionals being able to secure support from the right stakeholders to influence decision-making. Daudigeos (Citation2013) argues that OSH professionals focus on legitimacy-building relational tactics for the handling of internal and external stakeholders, allowing them to gain influence in their organizations. He emphasizes the abilities of professionals to assess the situation and deploy a set of specific influence tactics: gaining the endorsement of internal or external stakeholders, saying the right things to the right people, and adjusting their specific persuasion tactics in line with the people they are talking to (Daudigeos Citation2013). These insights may be highly relevant to the practices of OSH coordinators seeking to implement OSH measures.

The challenger role proposed by Provan et al. (Citation2017) concerns several activities. Firstly, challenging priorities and actions made by management has been described as an important role (Woods Citation2006). Here, the concept of “speaking up” is defined, through broader conceptualization, as the discretionary communication of ideas, proposals, opinions, or worrying issues (Morrison Citation2011). As an alternative to speaking up or directly challenging issues, acting as a constructive enquirer builds upon the idea that both organizations and OSH professionals should strive toward functioning in an environment that promotes clear dialogue and honesty (Rebbitt Citation2013). In this environment, ideas and concerns should be openly shared without any fear of the consequences. This is supported by Grote (Citation2015), who points to the fact that psychological safety is highly important to create an environment in which people feel safe to raise their concerns about OSH. This is of course a worthy thought, but as numerous sources have described, OSH, in both the construction sector and in general, is a highly contested area, riddled with subtle and overt negotiations of influence and power (Daudigeos Citation2013, Provan et al. Citation2017, Oswald et al. Citation2018, Ajslev et al. Citation2020). Therefore, direct challenging may yet be an important practice (Oswald et al. Citation2018).

In these negotiations, acting as an authority is also important to OSH professionals. Provan et al. (Citation2017) describe the role of the OSH professional in the organizational hierarchy as often being peripheral. Therefore, employing formal, hierarchy-based power may be difficult, yet important for exerting authority. In response to the doubtful opportunities for OSH professionals to exert formal authority, Dekker and Nyce (Citation2014) suggest that OSH professionals need to develop ways of practicing both formal and informal power to gain traction in the organization. However, studies concerning practices for gaining authority are absent. The lack of compliance with safety directions that has been described as a problem for OSH coordinators (Rubio et al. Citation2008) may be related to the relational roles of OSH coordinators, e.g. their ability to convert alliances, influence, and challenges into authority.

As the above shows, concepts for the understanding of relational roles performed by OSH professionals exist. However, none of these concern OSH coordinators in the construction industry, very few are based on observed practices (Broberg and Hermund Citation2007, Daudigeos Citation2013), and none distinguish between general practices and practices employed specifically in situations that lead to the implementation of OSH measures. In the following section, the methodology for investigating these positioning practices is developed.

Analytical framework: zooming out and zooming in

From its outset, this study has been inspired by a practice theory approach (Nicolini Citation2013). The collection of tools and theories for investigating and analyzing the practices of the world proposed by Nicolini (Citation2013) may, without question, be characterized as a “big tent” or generative approach to the creation of knowledge (Cooperrider and Whitney Citation2005). Its focus is on how different approaches and lines of inquiry may contribute to the production of knowledge about practices by shedding lights on different angles or aspects of the phenomena under investigation. Practice theory accomplishes this by compiling analytical tools and suggestions for “zooming in” on practices taking place, from the smallest micro-level of social interaction in conversation, gestures, and similar, as well as for “zooming out” and identifying the links between these micro-ongoings and other ongoings elsewhere.

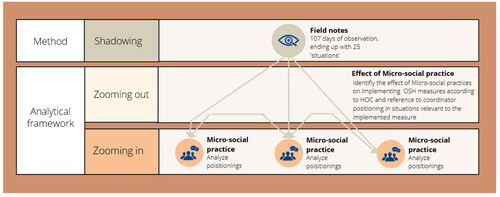

Both the zooming-in and the zooming-out elements of this study are inspired by positioning theory (Davies and Harré Citation1990, Citation1999) as the basic framework for understanding how links are tied between (1) speech acts performed by the OSH coordinators, and stakeholders with whom they negotiate safety and health, and (2) the subsequent implementation of OSH measures. In the zooming-in sections of the analysis, we focus on particular situations and interactions, exemplifying how coordinators position themselves to achieve the implementation of OSH measures. In the zooming-out sections of the analysis, we draw links between conversations showcased in the zooming-in analysis and other related situations described in the field notes. The analytical framework is illustrated in .

Investigating the practices of people can be undertaken by shadowing them (Czarniawska Citation2007, Nicolini Citation2013, p. 230). The shadowing approach, whereby OSH coordinators are followed in their working activities over a longer period of time, allows for an analysis that ties together the practices taking place in one situation to effects taking place in other situations.

Zooming in

As described, zooming in means to shed light on the micro-social practices taking place in particular situations, and it may take the form of numerous different sorts of analytical approaches, from conversation analysis to a focus on habitus and the body or critical discursive analysis (Nicolini Citation2013). As the aim of this study is to investigate the subject positioning undertaken through the micro-social practices of OSH coordinators, a positioning theory approach (Davies and Harré Citation1990) was applied to analyze the situations identified as leading to the implementation of measures identified through the zooming-out analysis. This approach follows the suggestion from Nicolini: “It follows that many of the theoretical and methodological insights from research programmes such as […] interactional sociolinguistics (Davies and HarréCitation1990) […] are directly applicable or at least highly relevant, to the understanding of social practice” (Nicolini Citation2013, p. 189).

Hence, the zooming-in analysis in this paper analyzes positionings made by the coordinator in the situation. Positioning theory was proposed by Davies and Harré (Citation1990) as a way of analyzing how interlocutors ascribe certain characteristics to themselves and others in social interactions—thereby constructing identities. As described, the concept of producing identities through discursive positioning differs from that of taking on a role through practice, in the sense that subject positioning implies a conscious or unconscious selection of discursive practices which places the subject in certain constellations of characteristics during the interaction. Roles, in a similar way to subject positioning, may refer to broader ideas or discursive formations that interlocutors draw upon or inscribe themselves into when making claims about themselves or others (Davies and Harré Citation1999, p. 42).

In this sense, we view roles as available discursive resources which OSH coordinators draw upon in their positioning practices. This can be observed when people make claims about themselves in conversation (reflexive positioning) or when they make claims about the characteristics of others or objects (interactive positioning). By ascribing characteristics to themselves, to others, and to other phenomena (organizations, legislation, material properties of things) (Ajslev et al. Citation2017), OSH coordinators negotiate the discourse of “truth” when in conversation with others. Sometimes, these positionings are conformed with, while at other times they are rejected by their interlocutors (Davies and Harré Citation1990). What follows is the revelation of what counts as an argument for implementing OSH measures in the analyzed situations. In line with the aim of this article, this practice of zooming in on positionings made by OSH coordinators serves to identify relational roles in which the coordinators, knowingly or unknowingly, inscribe themselves through their practice of positioning when successfully implementing OSH measures.

Zooming out

The zooming-out element allows the analysis to focus on what an OSH coordinator “does” in one situation, and on a qualified inference of the effects of those actions (Nicolini Citation2013). The zooming-out analysis visualizes the extensions and positionings that coordinators make in other situations that are related to the microsocial interactions showcased in the sections of zooming-in analysis. Zooming out is also a way of visualizing the “effects” of the discursive practices enacted in the microsocial situations, in the shape of the implementation of OSH measures, as well as providing contextual depth to the analysis. To analyze situations that lead to the implementation of OSH measures, one needs to know what one is looking for. There is a case to be made for tying this to legislation or inspection situations, if one were to apply a very narrow evidential frame of reference (Andersen et al. Citation2019). Recognizing the debate in this area, it was an ambition of the study to apply an approach that would allow for observations of a broad range of measures as these are applied in the practical world of OSH coordinators. To allow this basic identification of situations, a decision was made to apply the Hierarchy of Controls (HOC) approach. The HOC is recommended by national occupational safety and health institutions in countries, such as Canada, Denmark, and the US (NIOSH Citation2015, Kines et al. Citation2016, CCOHS Citation2019). The HOC is based on the relatively basic principle that measures can be categorized into five levels of efficiency (1) elimination, (2) substitution, (3) engineering controls, (4) administrative controls, and (5) personal protective equipment (PPE. In a recent study, we presented the total number of implemented measures during the shadowing study (Ajslev et al. Citation2022). As opposed to the previous study, in this analysis, the HOC was applied as a means of identifying relevant situations for qualitative analysis from the vast amounts of empirical material, consisting of field notes taken during the shadowing study.

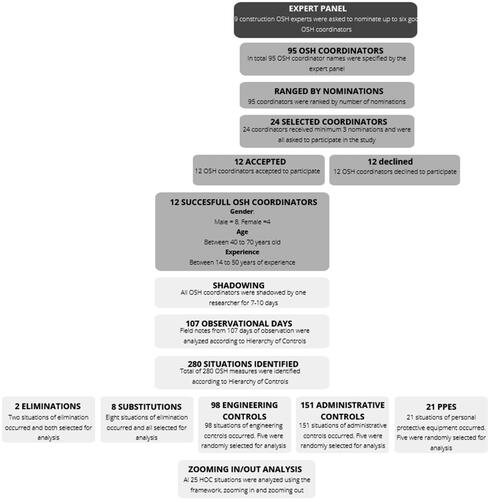

To apply the HOC analysis to our field work data, all field notes were imported to NVivo 11 (Citation2015) and they were initially analyzed by the two researchers independently for all situations in which the coordinator contributed to the implementation of an OSH measure. Disagreements were discussed to agree on the level of the measure. A rather high number of situations occurred (280) but only a few of these were in the higher levels of the HOC—there were only two eliminations and eight substitutions. Far more measures were implemented at the level of engineering controls (98), administrative controls (151), and PPE (21). The quantitative analysis of these situations is reported by Author et al. (2022). As the aim of the paper is to investigate the situations that lead to those measures which are supposedly the most effective, the ten situations from the elimination and substitution categories were selected for analysis, along with five randomly selected situations from each of the three other categories. These 25 situations constitute a best-case selection (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) of coordinator positioning practices in situations where they succeed in implementing measures. As such, we may expect that the analyzed situations illustrate some of the most effective positionings that coordinators may conduct. Had we chosen to analyze all types of situations and the associated positioning, we would not be able to make inferences as to whether those positioning practices were effective in attaining the implementation of OSH measures. This case selection is therefore especially relevant. It is the analysis of the 25 situations which is considered in the results section. An illustration of the methodological approach to case selection and the overarching steps of analysis are depicted in . In the zooming-out sections of the results section, we describe what happened outside the particular microsocial situation cited in the zooming-in analysis. This description considers both the positioning that coordinators practiced in related situations and what measures were implemented based on these discursive practices, evaluated in relation to the HOC.

Methods

The analysis is based on empirical material produced through a shadowing study involving 12 OSH coordinators working in the Danish construction industry. The field study was conducted between spring 2018 and fall 2019 by the two authors, who both have extensive experience with ethnographic research as well as positioning theory. Each coordinator was shadowed (Czarniawska Citation2007) for 7–10 days, during a variable but limited period, ranging from 14 days to two months. The period differed due to the coordinators having differing levels of availability for shadowing over the period. During this period, a researcher followed each OSH coordinator during his or her daily activities. This included office work, meetings, both on and off the construction site, safety walks, and whatever else occurred. The researchers conducted a total of 107 working days of shadowing. Each coordinator was shadowed by one researcher, who was responsible for the “case”. During the shadowing period, the researchers recorded extensive field notes. These notes were elaborated upon during breaks throughout the fieldwork, and in the evenings or on subsequent working days immediately afterward, so as to prevent important observations from being lost (Emerson et al. Citation2011). The focus of the ethnographic observations was based on an observational guide that aims to investigate how the coordinators engage in relations with other stakeholders, as well as the practices they conduct in their work to improve or maintain OSH coordination on the construction sites. The observational guide specified (1) that the researchers had to describe what happened in situations without passing judgement, (2) that the time and place had to be noted, and (3) that the researchers had to be open and inquiring rather than conclusive.

Communicative validation was sought by discussing the analysis and results at four workshops with coordinators participating in a national network for OSH coordinators, and one with the international health and safety coordinator organization (ISHCCO). All participants were highly interested in the results and expressed an interest in implementing the perspectives in future training, practice, and policy.

Identification of OSH coordinators—case selection

As the ambition of the overall study, of which this paper forms only a part, was to produce knowledge that could both shed light on the practices and impact of OSH coordination and produce knowledge that would be valuable to newer practitioners as well as researchers, a decision was taken to engage with particularly successful coordinators. This approach makes for a critical case selection (Flyvbjerg Citation2006), which allows for generalizability in the sense that we may expect that, when these particularly successful OSH coordinators experience barriers and obstructive practices, they may be generally disrupting the practice of OSH coordination vis-à-vis OSH professionalism in the construction industry. This inference relies on the argument that particularly successful coordinators are likely to have more experience, education, and larger networks, and that they are likely to work in organizations that are more open to and systematic about OSH than would be the case for the general practitioner.

To identify successful OSH coordinators to function as cases, a survey was conducted among experts in the Danish construction industry. In this process, the OSH coordinators were selected through a survey of 79 OSH experts in the construction industry. The expert panel consisted of people employed in unions, employer associations, and OSH advisory companies. These were asked to: identify, by providing a name and email address, up to six OSH coordinators that they considered particularly good at OSH coordination. This nomination process led to a list of 95 different names of OSH coordinators and we prioritized those with the most peer-nominations (11) for recruitment until we had 12 participants. Twenty-four coordinators received at least three nominations, and 12 of them accepted our invitations to participate in the study. The remaining OSH coordinators declined to participate for the following reasons: (1) Not performing coordinator tasks at the moment (n = 8), (2) working at confidential construction sites (n = 2), (3) retirement (n = 1), and lack of time (n = 1). All of the invited OSH coordinators expressed great interest in the study.

The 12 participating OSH coordinators were all highly experienced in OSH coordination and other OSH advisory work in the construction industry. They were aged between 40 and 70, and had between 14 and 50 years of experience. Eight were male and four were female.

Results

The results section is structured to give insights into the different positioning practices performed by the OSH coordinators in situations leading to the implementation of an OSH measure. Initially, we exemplify how coordinators position themselves in relation to the previously described relational roles. This is then followed by the exemplification of subject positions previously not conceptualized as relational roles, championing OSH and expert positioning, but which we argue should be conceptualized as such. Subsequently, then provides an overview of all the analyzed situations, the implemented measures in relation to the HOC, and the relational roles that coordinators positioned themselves within. This is followed by a section on the central importance of challenging and speaking up. Finally, we present two examples that underline the elaborate role-switching that coordinators practice to achieve the effects of their work.

Table 2. Overview of situations.

Positioning in OSH coordination at a glance

This first example presents a situation in which the OSH coordinator manages to implement signs on site instructing workers to wear helmets. As the analysis will show, he achieves this by employing numerous positioning practices and by placing himself within most of the overarching categories of the relational roles for OSH professionals:

At an extra safety meeting brought about as a result of the OSH coordinator continuously pointing out that workers on site must wear helmets in the appropriate areas, Jannik, the OSH coordinator, begins: “How may we (the coordinator and client) be of assistance?” The site manager, Richard, replies: “The cranes, creating boundaries, it has been dangerous and we need to get it under better control. And also, the helmets. But we need to agree on the rules”. They discuss whether helmets should be used across the whole site, or if they should only be mandatory within particular areas. Richard wants something to happen. Jannik: “We could make a kit”. Richard: “A checklist”. Jannik: “A checklist of five things to remember about creating boundaries and using helmets that will be relatively easy to do.” They agree, and Jannik spends the afternoon working on a poster showing the five items. He checks with Richard and they agree to put them up around the site and to include them in the crane instructions provided to the workers.

(Field notes, situation 19)

Zooming in: In his introductory remark, Jannik positions himself as willing to facilitate solutions for resolving the issue at hand. Through this positioning, he inscribes himself into an aspect of the alliance builder role, in the sense that he pays attention to the interests of the site manager (Theberge and Neumann Citation2010) while showing that, in his role as an OSH coordinator, he not only identifies OSH issues but also participates in developing solutions (Hale Citation1995, Woods Citation2006). In nine of the 25 situations, the coordinators inscribe themselves into this role. At the same time, he positions himself as a constructive enquirer—a particular type of challenger—as his positioning of himself as able to help the manager implies that something is not as it should be and has to be changed (Rebbitt Citation2013). Richard, the manager, conforms to these positionings by continuing Jannik’s line in the direction of specifying topics that Jannik may assist in solving. He further goes on to suggest that the rules need to be clearer. This implies that a lack of certainty in these areas of OSH has been a cause of the inconsistent use of helmets. This places responsibility between the two interlocutors as they “have to agree on the rules” and at the same time, it positions the site manager as responsible and engaged in OSH while having been somewhat powerless in enforcing unclear rules among his employees. Since both interlocutors conform and find these subject positions acceptable, they are able to move on and discuss a solution. Jannik suggests making a “kit” to which Richard responds with “a checklist” and Jannik takes responsibility for carrying this out.

Zooming out again, in the following days this led to the two of them putting up laminated notices on site, and instructing workers that they should pay attention to the checklist when working with lifts and cranes in the future. This is an example of administrative control (a level-four measure) according to the HOC. It is of contextual importance to note here that Jannik and a colleague took turns sitting in the site manager huts every day during this construction project. Hence, this allowed Jannik to be well-informed about what was going on, and what sort of work would be taking place in the near future. It seems that this was a primary reason behind why he was able to come up with an idea to fuse the interests of managers and OSH in the form of a procedure for crane work on the site (Theberge and Neumann Citation2010). By doing this, he inscribes himself within both the roles of alliance builder, and influencer, as he orients toward “saying the right things to the right people” (Daudigeos Citation2013). The influencer role was observed in eight out of 25 situations.

As this shows, the coordinators did orient toward the different roles depicted by earlier research in their positioning practices. However, the analysis also shows that OSH coordinators employed practices hitherto defined more as competences (Manuele Citation2003, Møller et al. Citation2020), in their positioning—hence pointing in the direction that enabling particular positioning practices are the primary reason for obtaining these competences.

Championing OSH

The first relational role which the analysis shows, and which has not been described as such before, is the relational role of the OSH professional as a champion of OSH in a broad sense. In this example of a successfully implemented OSH measure, Tenna, a shadowed OSH coordinator, is on an on-site safety walk:

Tenna addresses a worker drilling some tin without hearing protection and whose partner is not wearing a helmet, which is obligatory on site. First, they respond by joking. Then, Tenna tells them that she is the OSH coordinator. “Ah”, they respond and put on their helmets and hearing protection.

(Field notes, situation 25)

Zooming in: In this situation, Tenna question the usage of helmets by the workers and thereby positions herself in relation to the challenger role. Initially, the workers react to this by joking, and this challenges the legitimacy of Tenna’s authority to challenge their practice. Tenna responds by positioning herself as the OSH coordinator. This functions to assert her authority in matters of OSH, the workers conform to her speech act and put on their helmets. While these immediate positionings and effects take place in the situation, another extension of the coordinator’s actions also occurs.

Zooming out from the example shows that Tenna takes a broad OSH responsibility, which concerns situations where the coordinator goes beyond a narrow interpretation of his or her tasks in order to identify or resolve OSH issues. In the field of OSH coordination, there is some debate as to whether coordinators should intervene in OSH issues that are under the responsibility of the “employer” rather than the “client”. Wearing helmets and hearing protection does not endanger or indeed influence the OSH of other professionals on site. Therefore, Tenna could have ignored this issue and it would have been the “employer’s” responsibility if an incident had happened. Not a “client’s” responsibility, which many coordinators argue is outside the coordinator’s responsibility in legislative terms. She did, however, choose to address the issue, and this led to the implementation of a level-five PPE measure on the HOC. It may seem obvious that an OSH coordinator on site would address such an issue, but from our observations, we know that this is not necessarily the case. Therefore, this extension of implicitly or explicitly positioning one’s self as a champion of OSH, one who works to the best of one’s ability for the cause of improving OSH, can be added to our understanding of the important relational roles of OSH coordinators.

Expert positioning, an authority building practice

Another important practice was positioning one’s self as an expert on OSH. This practice implied coordinators displaying knowledge about OSH legislation, practical issues, or work processes and their associated risks, but also criticizing the work of others on a professional basis. The expert positioning practice was the practice most often observed and it occurred in 18 out of 25 situations. In the remaining seven situations, the coordinators did not need to position themselves as experts because the implemented measure consisted of arranging social gatherings for workers or leading a safety meeting as a measure in itself, or because they achieved action simply by asking for it. It could be argued that all implemented OSH measures would be the effect of coordinators acting as experts. However, we have only included situations in which the coordinator actively position themselves as knowledgeable in the analyzed situation. The following exemplifies how coordinator’s employ positioning to take on the relational role of OSH expert:

The time is 09.40 am, we are at a meeting with the project owner at the large renovation project. Margrethe, the project leader, and the client’s representative, Agnes, are leading the meeting. Eventually, Paul, the OSH coordinator, whom we are observing, is invited to give his evaluation of the design phase coordination on the project. He initially states that the form of safety meetings that has been planned for the project is simply not adequate, and that it cannot be used for construction workers. He then directly addresses the client’s representative: “I simply cannot see that any form of work has been done to think through this particular design phase coordination … and it is most imperative that we can use this piece of work for something other than referring to general standards and legislation … an OSH coordinator in the design phase is often very much alone, but she should know this”.

(Field notes, situation 1)

At the end of the excerpt, Paul gives some credit back to the design phase coordinator by positioning OSH coordination in general as a potentially isolated and thus difficult task. However, he underscores that this can still be attributed to her individual performance, because “she has to know this”. As such, this actually becomes a way of underlining his positioning as an expert who masters these things. Paul underlines this expert positioning by stating that OSH coordination is more than referring to legislation and standards.

Zooming out: This expert positioning may, in this situation, also be interpreted as an indexical extension challenging an established consensus about design phase coordination as something that may consist of referring to the OSH legislation or the general recommendations of the working authorities. This is an issue that OSH coordinators described numerous times throughout the observational study. However, in this way, we see how the coordinator is creating a professional position for himself as opposed to this practice.

The conversation at the meeting goes on:

Ebba, the hitherto unnamed OSH coordinator who conducted the design phase coordination has not attended the meeting because she is on sick leave in sick for the meeting. Before she did that, she talked it over with Paul. He explains. He further explains that she did not get sufficient information or time to perform a thorough coordination, and this made the work hard. Paul goes on to explain that the design phase coordination was carried out in 2016 and the start of 2017, which was before the final design elements were established in early 2018. Therefore, he argues, the OSH coordination cannot have been thoroughly thought through in its current state. He explains that the two coordinators have arranged to update the design coordination together.

(Field notes, situation 1)

Zooming in: As may be discerned from the field note text, Paul repairs his negative positioning of Ebba’s work somewhat by explaining that the work was conducted long ago. Further, he underlines that he will now apply his professional approach to improve the design phase coordination in cooperation with Ebba. In this way, he positions himself not only as a capable expert but also as a responsible and constructive alliance builder who is ready to correct the imperfections established. In this particular situation, Paul would not have to help correct the design phase coordination as this is legally the design phase coordinator’s responsibility. However, he chooses to do this anyway, to improve the OSH work—thereby positioning himself as a champion of OSH.

Paul goes on to tell the representative of the project owners that there should be a number of workshops to address each part of the construction process. Agnes, the representative of the project owner, replies: “We are fully supportive of that, you are the one who holds the professional knowledge to assess the need for that”.

(Field notes, situation 1)

Zooming in: this part shows how Paul now ventures into suggestions of what precisely to correct in the design phase coordination. In response to this, the project client’s representative conforms by directly positioning Paul as the right person to make that professional assessment. It seems that his earlier expert positionings have had the effect of contributing to his role as an authority in the eyes of the client’s representative. This is a highly interesting practice to notice because it shows how positioning one’s self as an expert at the expense of another coordinator is, in this way, also used to take on the role of an authority, which was actually the second most prevalent role practiced, occurring in 17 out of 25 situations.

Zooming out: Before the meeting, Paul discussed the matter of the workshops with Margrethe, who is his superior in the contractor’s organization, and she told him that she thought the workshops he proposed were redundant. Paul described his plan to Margrethe and she rejected it. Paul replied “okay” only to then bring it up to the construction owner’s representative anyway. As such, this is an example whereby he bypasses one hierarchical level in the organization to obtain the implementation of an administrative control. This practice could be seen both as a form of challenge and of influencing. In any case, Paul succeeds in implementing a more participatory and in-depth mapping of potential OSH risks in the project. But this is not the end of the story—or the meeting.

They go on to discuss the risks relating to the demolition and removal of used building materials in the project. Paul repeatedly argues for a total cleansing of lead and polychlorinated biphenyl in the building under reconstruction. The project owner’s representative says that they cannot afford to do this and the project is planned in such a way that only one profession should be in each room at a time, implying that this is not the responsibility of the project owner but of the entrepreneur. Paul argues that the working authorities and the public may make some noise (kick up a fuss) if, if these issues are not handled. Furthermore, he says that it is one thing to plan for only one profession to work in each room at a time, but that, as things play out, three professional groups will all of a sudden be working in the same room, and in that scenario, it would be better if the whole room had been cleansed. Finally, they agree that all of the places where walls will be penetrated and windows removed will be cleansed thoroughly before renovation work can commence.

(Field notes, situation 1)

Zooming in: The coordinator here seeks once more to draw on an expert positioning of the potentially dangerous substances, as well as the working authorities and public opinion, to gain authority in the matter. But, the client’s representative does not conform to this expert positioning—that would be too expensive. The authority gained through earlier expert positioning met its limitations, after all. In response, Paul again positions himself as an expert on the ever changing and unpredictable nature of construction work as an argument for a more careful stance toward the dangerous materials.

Zooming out: Through the final expert positioning, Paul manages to negotiate for a partial cleansing—an elimination of hazardous substances in the designated working areas. This is a level-one measure, according to the HOC. It ensures that the workers who are not professionally equipped to handle these materials are less likely to be exposed. That Paul insists on doing something about the matter of the dangerous substances is again a “speaking-up” type of challenge whereby he positions himself as being persistent in his ambition to resolve this issue in a professionally satisfying matter—a championing of OSH.

Summarily, the OSH coordinator in this example initially takes on the role of challenger by speaking up and by repeatedly positioning himself within the role of an OSH expert. These practices were later used to take up the role of an authority able to suggest solutions for solving the OSH issues he initially spoke up about. As mentioned, coordinators inscribed themselves within the role of an OSH expert in nearly all of the analyzed situations. However, as may be clear to the attentive reader at this point, these are also examples of an incremental building of a subject position with the power to affect OSH.

On challenging and speaking up

It may already be apparent that positioning practices that inscribe the coordinator as a challenger have taken place in the previous situations. The following section underlines the importance of these practices even further. The following example is from a situation in which an OSH coordinator manages to implement the usage of respiratory equipment during a painting task.

Zooming out: For weeks before the situation below, the contractor had sought to prove that they could work indoors and without using PPE when working with a MAL code 4/5 product. Michael, the OSH coordinator we shadowed in this situation, had repeatedly pointed out that this situation was illegal and that the employer had a responsibility to resolve the issue. Therefore, even before this particular situation began, he had already “spoken up” and challenged the actions of this entrepreneur.

Michael parks the car. We meet with a site manager from one of the contractors, who explains that they are just waiting for Michael, and that they want to get started right away. There is an English man visiting, who is presenting a testing machine that measures parts per million every minute. Michael seems a bit uneasy that the contractor has put all this into motion. Then he once more explains that the working authorities prescribe ventilated respiration no matter the concentration of particles in the air. The contractor’s manager explains that they use a lower concentration, and that they comply with the limits. Michael tells them that the MAL codes does not take the concentration of acrylate in the liquid into consideration, and that they have to use a mask with respiration no matter what. One of the site managers present asks if that is also the case if you spray it on rather than hand paint it. Michael says yes and goes on: “And that goes for site managers and directors visiting the site for test displays as well …”. There is an uncomfortable silence and they all mumble in agreement. Some find their masks; the rest move away from the test site.

(Field notes, situation 6)

Zooming in on the culmination of the OSH coordinator’s efforts, we can see here how the coordinator is initially positioned as being late upon arrival. Furthermore, it is explained to him by the site manager that an international authority is here to present a machine that will question the stance taken by Michael earlier. This positioning of the English man is a challenge to Michael’s position as the most authoritative expert on OSH present. While Michael did show signs of emotional discomfort, he immediately refutes the point that parts per million is an important factor in determining the legality of the working practice. In this way, he acts to position himself both in relation to the role configurations of expert (he lays out the legislation), challenger (he maintains the critical position toward an ongoing practice), and influencer (he involves the working authorities as a stakeholder). In response to this, the contractor’s manager again positions the group of managers and the contractor as working within regulations. Michael again rejects this positioning, restating his expert knowledge of chemical codes in OSH legislation. As a final challenge to the positioning of Michael as an authority on the subject matter, the site manager suggests “spraying it on” which Michael again rejects, adding “And that goes for site managers and directors visiting the site[.]” This finally achieves the subject positioning of Michael as the authority on the matter.

Zooming out again, this resistance to repeated suggestions to stop focusing on the matter at hand may be added to unfolding the role of the OSH professional as a challenger. While “speaking up” once was never enough to resolve this situation in a matter that satisfied Michael’s professional judgement, a particular persistence was necessary to implement this PPE, a level-five measure in accordance with the HOC. Michael argues that OSH matters are rooted in regulation and thus they are more important than hierarchical position. He thereby uses expert positioning to inscribe himself as an expert, and he accomplishes this by drawing on his knowledge of the OSH legislation concerning hazardous substances. As this situation shows, it takes a great deal of challenging, expert positioning, and influencing in relation to the site and project managers, as well as company directors, to gain the necessary authority to implement this measure.

In summary, while the first example showed how measures may be implemented by building alliances based on positioning one’s self as a cooperative, engaged, and as an expert professional, the three previous examples show that, in most cases, coordinators manage to implement measures based on challenging practices by repeatedly speaking up and showing persistence. However, as the examples show, this means that the OSH coordinator must also handle challenges that come their way, and still maintain their professional assessments.

The need to handle challenges that are directed back at OSH coordinators means that coordinators risk “losing face” as well as creating a negative emotional environment. The fact that it is necessary to challenge to succeed in implementing measures at all levels of the HOC, and that this occurs in the majority of the situations analyzed, speaks to the delicate, and complicated nature of practicing OSH coordination.

The entwinement of roles

As should be clear by this point, the positioning practices employed by OSH coordinators in their work to implement OSH measures are far from linear or simple orientations toward one role at a time. Rather, as situations unfold, OSH coordinators position themselves in relation to different roles or aspects of these roles to perform numerous things. The final situation exemplifies another sequence whereby positionings lead to the implementation of a measure. A situation occurs in which an OSH coordinator manages to secure the usage of a technical assistive device and to demand further support for OSH work on the construction site.

At a “crisis meeting” after a number of safety walks with two entrepreneurs on site. A number of negative observations have been made during the OSH coordinator’s safety walks and there have been two minor accidents in the previous weeks. The coordinator, Arne, has therefore arranged with the project owner’s internal OSH coordinator (a highly professional project owner with many sites) to have this meeting and take some action. The contractor’s safety managers have been summoned to the meeting.

Arne sums some issues up – there has to be more control in the form of safety walks and reports. Arne is constructive and asks if the safety managers need any help in these matters. But he uses a firm tone with regard to working at heights – every time we have been to the site, there have been issues with this.

(Field notes, situation 5)

The initial part of the field note contains a partial zooming-out, providing context for the present situation. Arne, the OSH coordinator, has decided that he needs to include the client’s internal OSH coordinator. While the coordinator we shadowed (Arne) is responsible for OSH compliance, walks, reporting, and activities on several sites, this internal manager oversees the OSH coordinators practicing on several sites and follows up on reports and incidents. That Arne calls upon this internal OSH coordinator positions him within the influencer role and shoes how influencing can be used as a means for gaining authority by drawing on the authority of someone higher in the organizational hierarchy. This highlights how positioning one’s self within one role is often used to inscribe one’s self into another role.

Zooming in: Arne challenges the safety managers regarding some of the OSH practices taking place. He uses this challenge as a ramp for positioning himself as willing to help the contractor’s own safety managers to keep check with their own administrative control procedures for the OSH work. As such, his alliance building, in this case, depends on him positioning himself as both an expert who is capable of assisting with improvements, and a caring, collaborative, and constructive person who is willing to assist the safety managers in their practices, but it also depends on initially criticizing the current state of affairs. Even though some of the things the contractors do are legally under “the employer’s responsibility”, he addresses these issues nonetheless. In this sense, he also goes beyond a narrow interpretation of his work tasks according to the legislation, and inscribes himself into the role of champion of OSH.

Arne goes on: “One thing is that you perform safety walks, but another thing is that the production people need to get on board!” He begins to ask about the organization of OSH work in each of the three contractor organizations. One of the safety managers explains that often the site managers simply do not react to the things he asks of them – they think the OSH people should do OSH work. One of the other safety managers agrees with this point. Arne: “I would like to invite the production people to these meetings as well.” The project owner’s OSH coordinator backs him up: “I think we need to get the people with the legal responsibility in here to talk these things over. Did anyone run any campaigns?” One of the site managers replies that they did not, but that it would make more sense if that was a general thing for the whole site. The project owner’s OSH coordinator asks for suggestions for some campaigns. Arne: “Yes, that would be really great, but the instructions are simply not good enough. On Saturday when I came in here unannounced, four guys were mounting 150 kg windows manually with no assistive devices. Even though they have the finest machine. It was unplugged and stood in the corner, you guys (singles out a contractor) have no clue whether people are instructed properly!”

(Field notes, situation 5)

Zooming in; Arne positions the “production people” as being uncommitted to OSH work on the site. This inscribes him as a challenger—questioning the engagement and priorities of the production people. At the same time, he positions himself as being capable and vigorous in the presence of the internal OSH coordinator. He thus shows that some activities on site are not living up to his ambitions for OSH and by doing this, he legitimizes his own position and thus seeks to secure his role of influencer through the support of the internal OSH coordinator. Arne is somewhat accommodated by two of the safety managers, who position him as rather powerless in his organization, as the site managers often do not react to OSH directions. These positionings contribute toward pushing responsibility for those incidents away from the OSH professionals and toward the “production people”—and thus as positioning Arne as somewhat powerless in handling the issues without creating a stronger alliance with the “production people”, as he suggests.

Zooming out: This may be interpreted as an indexical extension whereby Arne draws on previous experiences. As the OSH coordinator clearly states, production is concerned with other matters besides OSH. Therefore, OSH work can be decoupled from production whereby matters identified on safety walks are never transferred to the production practices—and this, therefore, prevents the implementation of more effective measures on the HOC.

Zooming in again: The project owner’s OSH coordinator initially supports the suggestion to engage the “production people” by positioning himself in agreement with Arne and the safety managers. Subsequently, however, he changes the direction of the conversation by suggesting a solution: “Did anyone run any campaigns?”. In this way, the project owner’s OSH coordinator positions himself as an expert, capable of discerning solutions for the problem at hand. This suggestion is initially accommodated by Arne: “Yes, that would be really great”, by which he cares for the project owners coordinator’s subject position as an expert. Arne then goes on to challenge the prudence of the suggestion stating that “the instructions are simply not good enough”. He acknowledges the need for campaigns, an alliance building practice, but then again he positions himself as critical toward the practices of the production people—and in so doing he challenges the solution proposed by the internal OSH coordinator. As such, he again positions himself as a challenger to the easy and convenient solutions. Arne specifies that the solution for the general state of misconduct is about instructions, which is a way of positioning the employers as legally responsible rather than the project client, an influencing practice. However, he also positions himself as an expert capable of addressing the most appropriate aspect of the issue.

In the example he sets out, he has been on site on a Saturday, his day off. Through this example, he once more positions himself as a champion for OSH on site, both because he came in on his day off, but also as he addresses the issue of mounting windows manually which is an employer’s issue. What we therefore see is that the OSH coordinator puts a great deal of relational work into positioning himself as a champion, influencer, alliance builder, and an expert, while positioning the production people as uncommitted.

Arne: From now on there will be written warnings if we see any repeats of what we observed in week 34. It will be better if you identify them yourselves.

OSH manager: They shouldn’t even be there.

The coordinator we observe finally underscores that if this type of thing is observed again, warnings will be issued. One of the OSH managers underscores his commitment to that cause. After this, the client’s coordinator repeats his message about campaigns which they agree upon, and finally they agree that the lifting machine for mounting the windows should always be used. Later, as we conduct a safety walk, the workers use the machine to mount the windows.

(Field notes, situation 5)

Zooming in: Finally, Arne takes on the role of formal authority by stating that warnings will be issued for future transgressions. This is, once more, a way for him to position himself as having done sufficient work, while the responsibility for the incidents lies with the safety managers and their production colleagues. The OSH managers conform to this positioning in several statements and the internal OSH coordinator agrees while underlining the need for campaigns, which may be a legitimization of his own ability to take action in the situation.

Zooming out: The outcome of this situation was observed over the following days in the form of workers employing technical assistive devices for the montage of windows and in meetings and written plans for improving communications between production and OSH professionals. This is a substitution, a level-two measure of the HOC.

This story bears testimony to the complex nature of OSH professional practice in the construction industry. It shows how an experienced coordinator switches between orientation toward alliance building, challenging, expert positioning, championing OSH, speaking up, influencing, and gaining authority. Only in a few situations in which coordinators managed to implement measures was this achieved without employing complex positioning practices. As described, these most often included challenging, criticizing, and speaking up to others, and this speaks to the delicate and often psychosocially trying position that OSH coordinators have to take up to achieve the improvement of OSH. It illustrates why effective OSH coordination is in fact a sophisticated, relational work of art.

Concluding discussion

This study is one of the few existing studies on the practices of OSH professionals and, in particular, on OSH coordinators in construction. As such, it contributes toward answering the call for more knowledge into how OSH coordination is conducted, with a particular focus on how OSH coordinators interact with other stakeholders and how they, through this interaction, position themselves in relation to relational roles to argue for and obtain the implementation of OSH measures. Importantly, the study conceptualizes a way of analyzing how relational roles are taken up through positioning practices. This analysis supports existing research that suggests the importance of being able to position one’s self in relation to the roles of challenger, influencer, alliance builder, and authority to conduct OSH professionalism (Provan et al. Citation2017). A key contribution of the study, however, is that it expands upon how these roles are taken up through the consideration of analytical examples from real coordinator practice.

The study goes further in showing that OSH coordinators often position themselves as professional experts on OSH and as champions of OSH as a part of their positioning practices and hence it suggests that these two positions may fruitfully be added to the vocabulary of relational roles that are of high importance to OSH coordinators. There is no doubt that expert knowledge has been previously established as a competence of OSH professionals (Pryor et al. Citation2019, Møller et al. Citation2020), however, this study shows how expert positioning is practiced and employed, often to enable the OSH professional to take on another important role, namely that of an authority.

This paper further contributes to the knowledge of the role of the authority as something other than the placement of OSH professionals within the organizational hierarchy. The analysis shows how the opportunity to take up the role of an authority as an OSH professional is often constructed through a process of orientation in relation to several relational practices. Authority is often negotiated and obtained through an entwinement of challenging, expert positioning, influencing, championing, and alliance building practices, and this then allows the OSH coordinator to propose and to receive support for the OSH measures they propose. While both Broberg and Hermund (Citation2007) and Daudigeos (Citation2013) point to the importance of securing the support of other stakeholders to obtain influence, this study points out that the practices required to achieve the implementation of measures are, in many instances, highly complex, and that the experienced coordinators—in the successful situations—are capable of switching between different roles during their positioning in the micro-sociological interaction.

The paper also adds to discussions about the importance of OSH professionals “speaking up” and taking on the “challenger” role. While Provan et al. (Citation2019) emphasize that challenging may actually be the hardest practice for OSH professionals to accomplish, this analysis shows that speaking up in the form of directly criticizing, voicing concerns, or indicating the legality of the actions or plans of other stakeholders (workers, managers, etc.) is one of the three most employed practices in the analyzed situations that lead to the implementation of OSH measures, along with expert positioning and authority. We argue that this unveils one of the most important reasons for the inconsistent effect of OSH coordination. We argue this because we know, both from social theory and from research on OSH initiatives in the construction industry (Goffman Citation1982, Ajslev et al. Citation2020), that the risk of losing face or social recognition restrains many people from challenging established norms and consensus. As considered by Rebbitt (Citation2013), few hierarchical organizations tolerate dissent but rather reward conformity.

The often uncomfortable need for challenging, speaking up, and positioning one’s self as critical toward the actions of others also contributes, to a broad degree, toward explaining the frustration that OSH coordinators experience when asking people to comply with OSH legislation or standards (Rubio et al. Citation2008). However, it may be the case that compliance is not the central reason for this frustration. Rather, this study shows that the real issue might concern the ability of OSH professionals to position themselves as authorities. As long as they are perceived as authorities, they often manage to implement the measures they propose. On the one hand, this is, of course, also an effect of the professionals’ positions in organizational and political matters. On the other hand, as this study shows, it also relates to the ability of OSH professionals to orient themselves toward different roles and to practice relevant positioning as the situation unfolds.

In relation to this, the study also finds that positioning one’s self as a champion of OSH is important in the sense that it may be perceived as an act of “speaking up” about OSH issues from a broader point of view than what may be in the contract of the OSH coordinator. This speaks to the importance of OSH coordinators practicing a moral approach to their work, and it shows that this approach may often be a contributing factor to identifying, addressing, and reaching measures for the handling of OSH issues. Considering the importance of championing OSH and challenging practices in relation to the implementation of measures, it could be beneficial to clarify to all stakeholders that it is the moral duty of OSH professionals to speak up, challenge, and broadly champion OSH in all matters.

Implications for research and practice

The construction industry is often portrayed as a rather unique industry, in which several contextual factors complicate the matter of improving OSH. For example, these include the temporary nature of the workplaces, the involvement of multiple employers and professional groups across many trades working at the same place at the same time, high levels of time pressure, heavy manual handling, the manipulation of large objects, work at different vertical levels and working class masculine identity configurations (Spangenberg Citation2010, Thiel Citation2012, Ajslev et al. Citation2017). As such, it is likely that the successful implementation of OSH measures through the particular case of OSH processional practice, in the form of OSH coordination in construction, is somewhat specific and perhaps more challenging than in other industries. However, judging by the existing literature on OSH professionalism in a broader scope (to name a few examples: Hale Citation1995, Provan et al. Citation2017, Provan and Pryor Citation2019, Swuste et al. Citation2014), there is reason to believe that the complicated nature of practice and the need for challenging, expert positioning and the championing of OSH are present in various degrees across industries. This paper may inspire studies in other sectors to map the practices that OSH professionals conduct to effectively implement OSH measures.

In their recent call for the establishment of boundaries for a profession of OSH professionals, Uhrenholdt et al. specify the need for an inclusive and “big-tent” toolkit, as well as the establishing of a set of values to characterize and distinguish OSH professionals from, for instance, human resource professionals, line managers and consultants (2019). This is evidently no meager task, and it is evidently also a task that must consider the demand for an increase in the efficiency of OSH initiatives and activities. While in Denmark, the professional boundaries of the OSH profession seem blurry, there is a larger international body of studies concerning OSH professionals and the tasks and activities that they can, should, and do perform in order to improve OSH. As Uhrenholdt et al. (2019) recently stated, compared to some other countries, such as Australia (Provan and Pryor Citation2019) or Canada (Pryor et al. Citation2019), the profession of OSH professionals in Denmark is at a more fragmented stage. However, OSH coordinators in the construction industry are definitely one type of OSH professional, and there is good reason to employ the case of OSH coordination to contribute to the broader literature on OSH professionalism. The present study shows the complexity and demands involved in successfully implementing OSH measures for OSH professionals in the construction industry. The switching between positioning practices “on the go” is something that OSH professionals have to master. The insights yielded by this study can therefore be beneficial in identifying the most important competences that OSH professionals have to be able to bring into practice to implement OSH measures. These are namely the competences of expert positioning, alliance building, challenging, championing OSH, influencing, and thereby being able to build authority.

This will most likely require more protracted and specific training of OSH professionals, and it will also demand a higher level of professional agreement on practice and ethical guidelines for conduct. However, it may also contribute to more tangible borders around the practice of OSH professionalism, and more impactful OSH professionalism in terms of implementing measures. This may assist the emerging profession of OSH professionals in positioning themselves as the mythical figure they are supposed to be, according to their own positioning practices and the political consensus—namely, champions of OSH. Indeed, when we discussed the results of the study and analysis during the communicative validation with coordinators participating in a national network for OSH coordinators, and with the international health and safety coordinator organization (ISHCCO), all participants were highly interested in the results and expressed an interest in implementing the perspectives in future training, practice, and policy.

Strengths and limitations

Methodologically, the study of practices by shadowing OSH coordinators does have some pros and cons. Observing practices using your own senses—firsthand—will often be a more direct approach to empirical material than material proposed to you through people’s narratives in the form of interviews. While interviewing allows you to analyze what people want you to analyze or how they feel about a given topic (Davies and Harré Citation1999), observational methods allow you to analyze what is actually happening. Compared to other qualitative methods, observation enables a high level of validity in the results of the study, because they are less prone to subjective interpretation or the political interests of, for instance, survey respondents, documents, or interview subjects. There is, however, the issue that people can and will somewhat change their conduct to hide their insecurities, weaknesses, or errors from the researcher. This study sought to remedy this by conducting many days of observations, during which people have to maintain their job functions and a positive social recognition among peers (Czarniawska Citation2007).

In terms of employing the HOC to identify situations in which the coordinators managed to implement measures, it could be argued that the HOC is a sort of wide umbrella for what counts as OSH measures. In terms of the evidence, however, it is very hard to exclude some types of measures and initiatives over others. While reviews try to do this (e.g. Andersen et al. Citation2019), the fact remains that you cannot implement eliminations without communicating about them first. Moreover, you cannot identify what to eliminate until you have learned what a hazard is. Administrative controls contribute to this through communication, campaigns, education, safety walks, and so on. Administrative controls may therefore be premises for the implementation of other measures that are more efficient in preventing OSH risks. We suggest that the HOC is a good way of identifying situations in which coordinators or OSH professionals manage, in general, to implement measures, and that this could be explored and developed even more widely as a means of identifying and evaluating OSH professional practice in the future research.

On another methodological note, it would be apparent to any observer of conversation and practices that it is not possible to write all conversations down. However, the scholars conducting the field notes are highly familiar with positioning theory and sought to write down conversations as accurately as possible. Of course, this does not provide the same level of detail or retraceability as audio recordings, but it provides the same level of legitimacy as other observational studies that are reliant on the observations made by a human perceiver. Indeed, part of the initial conceptualization of positioning theory was based on recollected conversation (Davies and Harré Citation1990, p. 34).

The focus of this analysis is on the relational roles. To some extent, this excludes several practices which OSH coordinators perform. For instance, all the bureaucratic, systematic, and administrative practices that coordinators perform are not very visible in this particular constellation. This is of course a loss, but in the construction of scientific contributions, one has to make choices as to what to include and what not (Barad Citation2007). At the same time, this lays the field open for future research to take up the mantle of investigating these practices.

The particular ontological “cut” (Barad Citation2007) that the analysis represents, in the form of investigating a very specific part of OSH coordinator practice, is something worth mentioning as well. As described in the methods section, this study engages with “the practices of successful coordinators in situations where they succeed in their implementing of OSH measures”. This is a very specific topic, which allows for the foregrounding of what happens in a selected part of what may be called OSH coordinator practice as a whole. In doing this, the analysis is based on what could be termed a “double-best-case selection”. Hence, successful coordinators were selected, based on a social recognition argument, and studied in cases in which they managed to successfully implement OSH measures. As such, this analysis is likely to showcase OSH coordination at its best. It can therefore be expected that the difficult and complex practices of implementing OSH measures may, as such, be present throughout OSH professional practice in the construction industry. When we see that the critical practices of challenging the actions of others are one of the most widely employed practices to result in measures being implemented, we may expect that less successful coordinators may need to challenge at least as much as these successful ones or even more. On the other hand, the selection of successful OSH coordinators based on peer recognition may not necessarily mean that we found the coordinators who were best able to implement OSH measures. It may be the case that these coordinators were just the best at upholding social recognition among peers. In such a case, at least, we have engaged with coordinators who managed to obtain this peer recognition. Since no more objective measures for evaluating successful coordination exist at the current time, this was the best possible way to study exemplary OSH coordinator practices.