ABSTRACT

Interventions to support mentalizing abilities are relevant for all people to enhance social skills and well-being. For people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, learning mentalizing skills may be challenging, however, because of the abstract and complex nature of the construct. The application of serious games has the potential to teach and train in these skills and engage this target group in treatment. This study investigates the key elements of a design model for a serious game aimed at learning abstract skills, taking into account the needs and wishes of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. We first searched the literature for guidelines covering effective interventions and for game design elements with the potential to train in abstract skills and motivate this specific group. We then included co-researchers with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities in guiding the development of the serious game ‘You & I’. Here we describe application of the recommendations from the literature to the development of the game and the co-creation process. This process resulted in key elements described in a design model that provides more structured knowledge for future studies of teaching abstract skills using a serious game in this population.

1. Introduction

Digital support is increasingly used to assist and improve care and treatment for people with intellectual disabilities (Sterkenburg and Vacaru Citation2018). One promising and relatively unexplored tool for this population is the use of serious games, gaming environments that combine the learning of serious concepts with fun and playful elements (Tsikinas and Xinogalos Citation2018). Such games have already been developed to improve cognitive skills (e.g. working memory), conceptual skills (e.g. perception of time), and practical skills (e.g. independence in daily living) for people with intellectual disabilities (Tsikinas and Xinogalos Citation2018). This growing range of content can be expanded to include improving social skills (e.g. interpersonal relationships and social problem-solving) and learning these abstract abilities in this user group.

For many reasons, such games are viewed as a promising innovation to enhance the attractiveness of training and therapeutic programmes and offer options that better meet the needs and wishes of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. Recent research has shown that people in this group experience more attention and motivation deficits and can have difficulty following traditional teaching methods (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014). Serious games can successfully capture and hold attention because they can provide a varied digital environment of games, questions, and videos that people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities may use at their own pace to acquire or improve skills. Positive feedback can be instantly available, and with simulated visualisation and explicit representations of complicated abstract concepts, serious games offer realistic environments for experimenting and practicing these concepts (Ke Citation2009; Torrente et al. Citation2012; Terras et al. Citation2018). Because these environments are safe, of low pressure, and predictable, people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities can improve their skills without the consequences, risks, or feelings of insecurity or anxiety that are possible when practicing such skills in real-world daily life (Torrente et al. Citation2012; Grossard et al. Citation2017; Terras et al. Citation2018). These positive features highlight the potential of serious games for teaching and training people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities and emphasize how important it is that the games meet the wishes and needs of the target users.

The increasing popularity of serious games for this population is also apparent from the expanding range of game content. Tsikinas and Xinogalos (Citation2018) classified computer serious games for people with intellectual disabilities according to the skills they aimed to improve and investigated whether these games seemed successful for users. The results showed that serious games mostly focussed on improving practical skills (i.e. daily living, work-related skills), cognitive skills (i.e. attention and understanding, working memory, comprehension, and punctuation), and conceptual skills (i.e. numbers, time, money, language, and literacy). For 17 of 19 reported studies, the authors evaluated the effects of the serious games. They found that 14 studies identified significant improvement in the skills these games addressed, suggesting positive potential for these tools. Games with a focus on social skills can contribute to the expanding range of content.

For people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, social adaptation may be challenging because of atypically developed social–cognitive and executive functions (Van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. Citation2011). Mentalizing abilities in particular – i.e. the ability to recognise and reflect on mental states of others and self, such as feelings and thoughts – may be limited (Allen, Fonagy, and Bateman Citation2008). This ability is important for engagement in social relationships and preventing conflict (e.g. by interpreting social events from different perspectives; Baglio et al. Citation2016). People with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities may find challenges in reflecting on self in relation to the thoughts and feelings of others, interpreting facial expressions, estimating the intentions of others in social interactions, and considering the perspective of others, all of which are important for mentalization and functioning in social situations (Yirmiya et al. Citation1998; Janssen and Schuengel Citation2006; Douma et al. Citation2012). Being unable to assess social situations accurately can lead to stress (Janssen and Schuengel Citation2006), which can impede the development of mentalizing skills.

Thus, improving mentalizing abilities and stress regulation as social skills holds the promise of leading to better functioning in social situations and seems to be an apt target for a serious game intervention for people with intellectual disabilities. However, designing a serious game supporting hard-to-learn abstract mentalizing abilities for a user group that responds well to concrete concepts could be challenging (Douma et al. Citation2012). For this reason, we investigated the key elements of a design model for a serious game aimed at building abstract skills such as mentalization and stress regulation, taking into account the needs and wishes of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. For this purpose, we formulated three sub-questions: 1) Which recommendations or guidelines exist for using a serious game to effectively teach abstract skills, such as mentalization and stress regulation, to this specific target group? 2) According to the literature, which game design and game elements are essential in a serious game to keep players involved and motivated? 3) How can the needs and wishes of our specific target group be taken into account? We applied the information elicited by these questions to the development of the serious game ‘You & I’, intended to enhance social functioning through improvements in mentalizing abilities and stress regulation in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. Finally, by merging the findings into a new model, we sought to provide recommendations for the development of future serious games focussed on teaching practical, cognitive, conceptual, and social skills to this user group.

2. Materials and methods

To answer sub-question 1, we searched the literature for the most relevant recommendations or guidelines on teaching abstract abilities effectively to our specific target group through a serious game. We performed a search of Google Scholar using the terms ‘guideline’ OR ‘recommendations’, ‘abstract skills’, ‘effective’, ‘serious game’ and ‘intellectual disabilities’, both in Dutch and English, published up to and including 2017, sorted by relevance. We used Google Scholar because of its wide coverage of the literature, which includes not only articles but also reports, books, and other documents (Bramer et al. Citation2017). This search did not yield any specific recommendations or guidelines aimed at effectively teaching abstract abilities through a serious game for our specific target group. Therefore, we broadened the scope of our search terms, replacing the term ‘serious game’ with ‘interventions’ (in general) and omitting ‘abstract skills’ because it was possibly too specific. These changes led to the identification of one guideline for effective interventions for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012). This guideline document provides an overview of factors to consider when developing, adapting, and applying a successful intervention to evoke behavioural change in people in this population. Although the publication was not specifically aimed at teaching difficult-to-learn abstract skills, its recommendations target teaching skills through an effective intervention and were explicitly developed for our target group. For these reasons, we viewed it as the most suitable for use in our study.

To answer sub-question 2, we also searched Google Scholar for the most relevant recommendations on game design and game elements that are essential in a serious game to keep the players involved and motivated. For this search, we used the terms ‘serious game’ OR ‘serious games’, ‘design’ OR ‘game design’ OR ‘game elements’ and ‘intellectual disabilities’, published up to and including 2017, sorted by relevance. The search did not return hits related to specific game design elements or frameworks for people with intellectual disabilities; however, we did find a publication addressing game design principles for people with cognitive disabilities (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014). Because we wanted to delve more into (working) game elements, we decided to search further in the literature to compare these design principles with other game elements. For this purpose, we expanded the scope of our search terms and changed ‘intellectual disabilities’ to ‘disabilities’. This search returned published recommendations by Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) for people with autism, which may be relevant because this target group appeared to need the same adjustments in teaching methods (Tsikinas and Xinogalos Citation2018). In addition, multiple experts in the field recommended Sort and Khazaal’s (Citation2017) paper on important game elements for health care in general. Because of the concrete tips these authors provided, we also included it.

To answer sub-question 3, we sought information about the needs and wishes of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities by involving members of this target group in the development process of the serious game. As Kato (Citation2013) noted, co-creation benefits the development process because the target group is likelier to receive what is being developed as acceptable and credible, and more broadly, the result better matches with practice. Moreover, active involvement of the target group in research is perceived as valuable because of the increased quality and validity of the research and the benefits for stakeholders (Frankena et al. Citation2015). For this reason, three co-researchers, all adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities identified through a care organisation in the Netherlands, were involved in the development phase of the serious game, serving as representatives of the target group. From a larger group of experts-by-experience, the three co-researchers (adults, male, with and without gaming experience) who participated seemed best able to convey how they wanted to use their experiential expertise in research and why they wanted to be involved in research. In the beginning of the collaboration, researchers and co-researchers underwent a training called Stronger Together that addressed how to work together in an equal way (Landelijk Federatie Belangenverenigingen Citationn.d.). So that they could achieve a certain level of comprehension, these co-researchers were also trained in the principles of conducting research, called CABRIO training (Kennisplein Gehandicaptensector Citation2019). After attending the first training, the researchers and co-researchers met every month to discuss the development of the serious game ‘You & I’, review relevant developments for serious game research, and continue working on ways to collaborate in the co-design process. The co-researchers also attended meetings with the game designers. During the collaboration for the development of this serious game, we used the consensus statement of inclusive health research to guide the inclusive design process (Frankena et al. Citation2019). The attributes relevant for this design process were ethos, recruiting researchers, designing the study, facilitating the process, and dealing with practicalities.

3. Results

The results of this paper are structured in the order of the three sub-questions. Because we describe the findings for the sub-questions in the context of developing the serious game ‘You & I’ for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, we first give a brief explanation of the serious game.

3.1. Short description of the intervention

The serious game ‘You & I’ is a computer game for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. The game is intended to be a supportive training tool to practice, repeat, and improve mentalizing abilities and stress regulation in a fun but educational way. It also is intended to promote the learning experiences of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities without the help of parents, caregivers, or other professionals. In eight gaming levels, the player follows the main character, Mo, on his adventure visiting his friend Emily in the USA. The player’s goal is to accompany Mo on his trip from the Netherlands to the USA and improve Mo’s mentalizing abilities and stress regulation through watching videos, playing mini-games, and answering multiple-choice questions.

3.2. Sub-question 1: Which recommendations or guidelines exist for using a serious game to effectively teach abstract skills, such as mentalization and stress regulation, to this specific target group?

The literature search resulted in a single guideline document for effective interventions for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012). The authors of those guideline linked findings from the literature to findings from interviews with caregivers and researchers working in the field of intellectual disabilities and in part as developers of interventions. They describe six categories of recommended adjustments to interventions to increase the chances of effectiveness: 1) adjust the communication method, 2) make the exercise material concrete, 3) structure and simplify the exercise material, 4) use extensive diagnostics, 5) provide a safe and positive learning environment as a therapist, and 6) network and generalise. Because this guideline covers interventions, we critically examined the categories for application to serious games. Serious games provide numerous ways to adjust the method of communication and to concretise and simplify materials and methods. Thus, we found that the first three categories of this guideline were relevant. The other three categories appeared to be less relevant. For this serious game, we needed no extensive diagnostics (fourth category) to pre-determine the level (strengths and weaknesses) of each individual player for adapting the game accordingly. This step was beyond the scope of the serious game ‘You & I’. Serious games are a safe environment in themselves for users to acquire skills at their own pace without pressure (Terras et al. Citation2018), and they preclude the need for interaction with others, such as a therapist. For these reasons, it was unnecessary to emphasize creating a safe and positive learning environment specific to each participant individually (fifth category) or to consider the specific involvement of the network (sixth category). As described below, we used the first three recommendations to translate the abstract abilities of mentalization and stress regulation into concrete learning objectives and working elements that matched the level of understanding of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities.

In the category adjust the method of communication, the guideline advises simplifying the use of language. Throughout the developmental phase of the game ‘You & I’, we focussed on using short sentences with common and concrete words and avoiding broad terms. For example, the sentence, ‘It makes him feel anxious that Emily has not called him yet’ became, ‘Emily has not called him yet. This makes him feel anxious’. In addition, we used the terms ‘bus’ and ‘metro’ rather than more general terms, such as ‘public transportation’.

In the category make the exercise material concrete, the guideline advises aligning examples with the interests of the target group and facilitating learning primarily through experience. During game development, the co-researchers suggested three options for the theme of the game. Through voting, other persons with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities indicated their preference, and the theme of the game was decided to be ‘travelling’. Furthermore, the co-researchers indicated which positive rewards and symbols matched their interest and understanding. The mentalization and stress regulation concepts then were integrated into different gaming elements (e.g. mini-games, multiple-choice questions, and true/false questions) and placed into the serious game, creating a learning setting in which the players learned through experience rather than just receiving information.

In the category structure and simplify exercise material, because people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities may have concentration and processing difficulties, the guideline suggests using more structure and simplifying, dosing, and organising the exercise material and information (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012). In ‘You & I’, the storyline provides structure by visualising the flow of the serious game, offering gaming levels, and repeating the same gaming structure in each level.

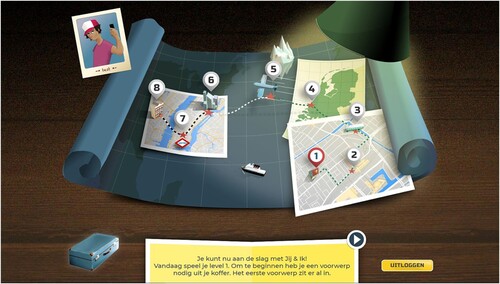

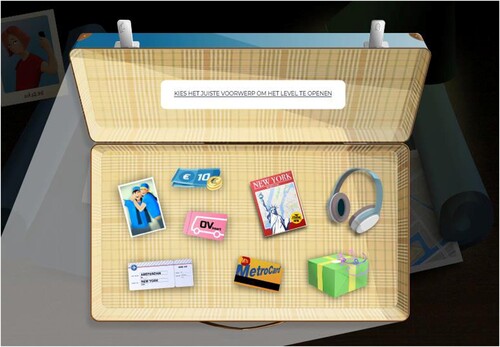

The game consists of eight levels, each taking approximately 30–45 min to complete (). In the first level, the player finds Mo sitting on a sofa looking sad. In that level, the player learns that Mo is sad because he misses his friend Emily. At the end of the first level, Mo discovers, with the help of a voiceover, that he can travel to the USA to visit Emily, and the player learns that this is the game’s storyline. The storyline guides the player through the different levels and ensures that the player practices and trains in skills related to mentalization and stress regulation. Each level of the game has the same structure, consisting of eight different elements, including videos, questions, and mini-games (). Once a level is completed, the player receives a reward, an object in a suitcase that represents the next level (). With that object, the next level becomes available to play.

In addition to the structure of the serious game, we achieved simplifying, dosing, and organising the exercise material by offering it in different ways. This tactic takes into account that people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities can have relatively short attention spans (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012). To practice mentalization and stress regulation, we embedded three different mini-games (emotion picture game, a game about mentalizing thoughts, and a game about stress), multiple-choice questions, and true/false questions in the serious game. The multiple-choice questions test knowledge gained from the videos, and the true/false questions test knowledge gained from the entire level. In the mini-games, the different skills for better mentalizing (i.e. emotion recognition and mentalizing thoughts) and dealing with stress (i.e. stress-regulating thoughts) were practiced.

Mini-game 1, ‘Memory’: Within this mini-game, the player learns to recognise different emotions by combining the written emotion with the correct facial expression (a).

Mini-game 2, ‘Helpful thoughts/unhelpful thoughts’: Within this mini-game, the player learns that some thoughts are helpful for calming down if someone is angry, whereas others are not. The player is asked to estimate whether a given thought will help calm someone down or will make someone more upset (b).

Mini-game 3, ‘Stress head’: This mini-game also focusses on unhelpful thoughts when someone is stressed. The player is asked to estimate which of the given thoughts would help someone calm down or would make someone more stressed (c).

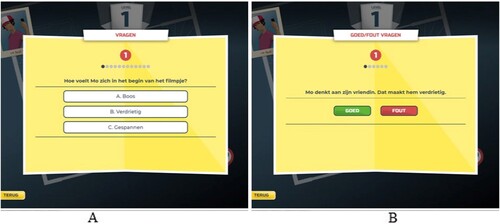

Multiple-choice questions: The multiple-choice questions tested the acquired knowledge of the player (a). The player answered questions related to the video, about Mo’s feelings in the video, about the feelings of the player, and how to deal with uncertainty about the feelings of another person.

True/false questions: At the end of each level, the player was presented with six statements about things that happened in the videos (b). With the statements, the player reflected on what happened in the level and what was learned.

Finally, during the development of the game, learning was supported by repeating the learning element in different ways and by simplifying, dosing, and organising the exercise material. This recommendation is combined with the dimensions of mentalization of Choi-Kain and Gunderson (Citation2008), as shown in . With this strategy, there was one dimension as a central theme of a level being practiced (i.e. simplification), gradual expansion of the dimensions covered in each level (i.e. dosing), and offered repetition of the dimensions of mentalization (i.e. organisation; Derks et al. Citation2019).

Table 1. Overview of themes and domains of mentalization for each level of the serious game ‘You & I’.

3.2. Sub-question 2: According to the literature, which game elements are essential in a serious game to keep players involved and motivated?

The literature search resulted in three articles, providing mostly overlapping but partly different recommendations about important game elements for serious games and gamification in health care (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014; Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf Citation2015; Sort and Khazaal Citation2017). The game elements from these articles were specifically chosen because the authors provided principles that seemed likely to stimulate learning and performance and to increase involvement and motivation to play a game. These factors were particularly relevant because the serious game ‘You & I’ focusses on abstract abilities that are difficult to learn, are not immediately rewarding, and generally require weeks or maybe months of training, during which motivation and involvement can fade (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014; Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf Citation2015; Sort and Khazaal Citation2017). We did not apply the advice of Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) to adjust the starting point for every player and allow the level of difficulty to increase in an individualised way or that of Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) to add a form of social support from the network. Our reason was the assumption, based on the literature, that adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities would have difficulties mentalizing. Thus, for this game, the starting point was initially levelled, and the increase in level of difficulty was the same for every player. This approach for a serious game is extremely suitable for this target group to acquire skills at their own pace without the pressure (Terras et al. Citation2018) that they might otherwise have felt had people from their network been involved. The applied game elements were used in the development process to support game participation and use by this target group over time.

The advice first proposed by Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) and supplemented by Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) and Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira (Citation2014) for the transmission of a concept was to know what your goals are. If the learning objective of the intervention is in line with the expectation of the player and thus clear (e.g. accomplished by involving the target group in the development process), and both long-term goals (e.g. learning skills) and mid-term goals (e.g. correctly completing all questions and games) are integrated, player engagement and intrinsic motivation are likely to increase. We worked with co-researchers representing the target group to determine the learning objective of the serious game ‘You & I’ (i.e. improved mentalizing abilities and stress regulation in adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities). The long-term goal of this serious game was learning mentalizing and stress-regulating skills and receiving a certificate of participation based on the game theme. The mid-term goal was learning aspects of the mentalizing and stress-regulating skills in each sub-game in the levels, obtaining the objects that allow access to the next level so that the player can continue the journey with Mo.

In accordance with the advice of the guideline to align examples with the interests of the target group (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012), Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) proposed that an intervention should put the user first, i.e. understand what the user needs and wants in a serious game and compare that with what the user experiences when playing it. Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira (Citation2014) supplement this advice by also recommending that the interface, user control, and accessibility be tailored to the target group. In the development process of the serious game ‘You & I’, we took into account the user experience by involving co-researchers from the target user population and by making the game easily accessible for the target group. Players can overcome practical obstacles early; the game is web-based and playable on any platform; and it includes voiceover for persons with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities who may have reading difficulties, with written text adapted to the vocabulary of the target group.

Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) proposed the use of behaviour change theories for inspiration in the development of a game-based intervention to bring about actual behavioural change. In the development process of the serious game ‘You & I’, we took into account the autonomy element of the self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000): If the player can make choices about some elements in the game, a sense of control, autonomy, and identification can be established, and intrinsic motivation will improve (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014; Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf Citation2015). In the serious game ‘You & I’, the player can dress up an avatar at the start of the game, representing themselves as the owner of their learning experience. In addition, the operant condition element of the behavioural learning theory states that individuals learn from positive, good behaviour through reinforcement and learn from their mistakes through consequences (Hergenhahn and Olson Citation2001). This outcome can be achieved by a trial-and-error learning process, which allows the learner to refine their knowledge when reflecting on their playing strategies and to be driven to try it again (Wang and Chen Citation2010). We also applied this way of learning, motivating, and refining knowledge in the serious game, in that the players did not get access to the next element by giving the wrong answer but did get the opportunity to learn from their mistakes by trying again. Good answers gave access to the next question, element, or level.

Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) and Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) also proposed that in game development, it is essential to use play, fun, and game theories in the development process. Developers should create an optimal flow for the user to proceed to the next level without feelings of insecurity about it and to increase levels of difficulty in the game and individuation as important elements for an attractive journey. In accordance with the advice of the guideline to simplify, dose, and organise the exercise material and information (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012), the serious game has gradual and target group–appropriate increases in difficulty, starting with easy assignments and working towards more difficult aspects to create an optimal flow. We determined the level of difficulty using the dimensions of mentalization described by Choi-Kain and Gunderson (Citation2008).

For make games appealing to continue learning, the advice includes adding elements, such as positive feedback and rewards, to keep users engaged and to discourage negative feedback, which can diminish the player’s motivation to continue or play the game (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014; Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf Citation2015; Sort and Khazaal Citation2017). In the serious game ‘You & I’, the players receive immediate, continuous feedback if questions are answered incorrectly and receive rewards (i.e. objects in the briefcase to unlock the next level) if a level is completed to continue playing.

The last feature proposed by Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) is the storyline or narrative that can achieve several aims if it includes certain elements. The storyline should be attractive and integrated with target goals and skills to be learned and follow a specific character. With these elements in place, the serious game should be able to increase the intrinsic motivation of the learner and enjoyment of the game, foster learning of the specific educational content that is the focus, and promote social skills improvement through development of social connections with the character. In the serious game ‘You & I’, this goal is pursued by following one specific character (i.e. Mo) in a storyline (i.e. Mo is going to the USA to meet his friend).

3.3. Sub-question 3: how can the needs and wishes of our specific target group be taken into account?

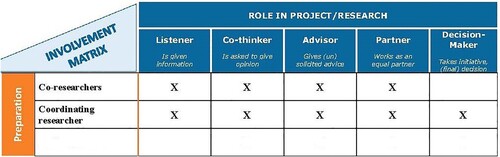

To incorporate the needs and wishes of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, three co-researchers with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities took part in the development phase of the serious game ‘You & I’. Moreover, the literature search made clear that the recommendations or guidelines given were sometimes abstract, not concrete enough to directly implement in the serious game ‘You & I’. Consequently, the co-researchers gave advices regarding implementation of these recommendations and guidelines that would match with their wishes and needs. The co-researchers had different roles during the developmental process. An involvement matrix (Kenniscentrum Revalidatiegeneeskunde Utrecht Citation2019) was used to accommodate their role in the preparation phase of the project (), specified as listener, co-thinker, advisor, partner, or decision-maker.

Figure 6. The involvement matrix (Kenniscentrum Revalidatiegeneeskunde Utrecht Citation2019) of the participation of co-researchers in the preparation phase of the development process of the serious game ‘You & I’.

In the first role as listener, the co-researchers were given information and played a less active role in the project. In the preparation phase, for example, the researchers gave information to the co-researchers about the project and progressions. It had already been determined that a serious game with the objective of improving mentalizing abilities and stress regulation was going to be developed before the co-researchers became involved, and the co-researchers were informed of this.

The role of co-thinker was somewhat more active than the role of listener. In this role, the co-researchers asked questions and gave feedback or their opinion. In the preparation phase, the co-researchers played another serious game called ‘See’ (Lievense et al. Citation2020) with the same design to discover which elements would and would not work for the target group. In the monthly collaboration meetings and the meetings with the game designers, co-researchers were asked for feedback on the different elements of the serious game: on the design of the mini-games, the comprehensibility of the questions asked, and the level of difficulty of the mini-games and questions. For example, they mentioned that the number of emotions shown in the memory game should be reduced from nine to six, the number of answer choices should be limited to three, and the sentences in the feedback should be shorter. They also were asked for their opinions about the script of the serious game and the number of mini-games in the game.

In the next role, advisor, the co-researchers gave advice. This function is closely related to a role as co-thinker, but goes further. For example, in collaboration with the co-researchers and the game designers, the theme of the game (i.e. travelling) was determined. According to the co-researchers, the theme of travelling was the most recognisable and appealing theme for the target group. In addition, they gave advice about the player’s avatar, saying that it should be neutral so that players could adapt it however they would like. To use their own words: ‘You must be able to change something about your character so that you feel that it is your game, your learning experience’. In addition, through their experience with testing the other serious game, they advised adding clear instructions in the game about the actions to be taken. These steps were confusing and unclear in the other serious game. Furthermore, the co-researchers advised not adding music to the serious game but instead to use only a joyful sound when an exercise was properly completed. They had found the music distracting in the other serious game. The co-researchers gave advice similar to that of Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017) and Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015), which was to add rewards in the serious game. They also made recommendations about the objects to be included as rewards in the suitcase to represent the corresponding level.

The co-researchers were equal partners. In the development process of the serious game, co-researchers and researchers worked side by side and were equally important in presentations at congresses and meetings and in early recruitment campaigns for the investigation of the effectiveness of the serious game.

In their fifth and final role, the co-researchers were decision-makers and took initiative in decision-making. Because they had not previously participated in research, they could not actively fulfil the role of decision-maker, so this role was a goal in both the execution and implementation phases.

4. Discussion

This paper identifies the key elements that are relevant for developing a serious game for hard-to-learn abstract skills, such as mentalization and stress regulation, while taking into account the needs and wishes of the target user group, which was adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. First, for our specific target group, we performed a literature search for recommendations or guidelines that address effective ways of teaching abstract abilities by means of a serious game. Because the search proved to be too specific, we broadened it to include recommendations or guidelines on effective interventions for our target group. The results included only one published guideline covering effective interventions for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012), aiming at initiating a behavioural change. During the co-creation process of the serious game ‘You & I’, we focussed on three relevant categories of advice: 1) adjust the method of communication, 2) make the exercise material concrete, and 3) structure and simplify the exercise. We translated these three categories into the following key elements: simplify language; align examples with the interests of the target group; let the player learn through practicing and experiencing a variety of game elements; use structure in both the game and in a gaming level; and simplify, dose, and organise the exercise material and information. Moreover, the separate key elements were also expected to contribute to the acquisition of hard-to-learn abstract skills (De Wit, Moonen, and Douma Citation2012).

Second, we investigated which game elements are essential in a serious game to keep the players involved and motivated. For the serious game ‘You & I’, we applied the necessary elements that Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017), Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira (Citation2014), and Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) considered essential to a serious game to stimulate learning and performance and keep the players involved and motivated. These elements are especially important in teaching hard-to-learn abstract skills such as mentalizing and stress regulation. Although the elements in the referenced publications were not specifically associated with games for people with intellectual disabilities, the recommendations were largely similar and complementary among the three articles and appeared to be valuable and relevant for our target group. These key elements were a clear learning objective with integrated long-term and mid-term goals, an attractive storyline, use of self-determination theory, positive feedback and rewards, trial-and-error learning, and provision of an optimal flow in the game, taking into account the needs and wishes of the user (technological accessibility). Although the other elements advised by Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017), Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira (Citation2014), and Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015) were not applied in the serious game ‘You & I’, they can be recommended as key elements for future serious games in which the level of play might vary at the beginning and develop differently and for which support while playing is desirable. These elements are to adjust the starting point for every player (e.g. with extensive diagnostics), increase the level of difficulty in an individualised way, and add a type of social support in the serious game.

Third, co-researchers with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities were involved in the development process to contribute input about the needs and wishes of the target group. Their participation was explored using the involvement matrix, and in the preparation phase, the co-researchers took on four out of five roles. Among their functions, they received information (listener), gave feedback or their opinion on the script and elements of the serious game ‘You & I’ (co-thinker), advised on the theme and player’s avatar in the game (advisor), and were equally important in presentations (partners). With the contribution of co-researchers, which is more or less also recommended in the guidelines of De Wit, Moonen, and Douma (Citation2012) and the game elements of Sort and Khazaal (Citation2017), Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira (Citation2014), and Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf (Citation2015), it was possible to concretely translate advice from the literature into elements in the serious game. For example, where these authors advised adding feedback and rewards to the serious game, co-researchers offered advice about the types of feedback and rewards that would be desirable. Therefore, the involvement of co-researchers is a key element in designing a human-centred and user-centred serious game for a specific user group.

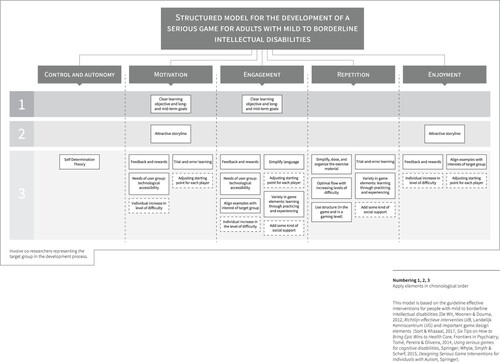

The literature search for key elements and the application of these elements to the co-creation of the serious game ‘You and I’, together with input from co-researchers with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, resulted in new insights that we translated into a design model (). This design model focusses on the development of a serious game aimed at teaching hard-to-learn abstract skills, such as mentalization and stress regulation, for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. The model states that the design process should ideally be a combination of the use of categories from the guideline of De Wit, Moonen, and Douma (Citation2012), game elements (Tomé, Pereira, and Oliveira Citation2014; Whyte, Smyth, and Scherf Citation2015; Sort and Khazaal Citation2017), and co-creation of the serious game. This design model might be useful for future studies.

Figure 7. Model for the development of a serious game for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities.

Our analysis of the categories from the guideline and the game elements showed that they focus on five core characteristics that can improve the learning experience with hard-to-learn abstract skills and increase the chances of an intervention’s suitability and success. These core characteristics are control and autonomy, motivation, engagement, repetition, and enjoyment. The concrete (working) elements are divided under the core characteristics to promote and stimulate learning from these five core characteristics. To further guide future game design processes, the recommended sequence can be followed when applying these (working) elements. In shaping these concrete (working) elements, the involvement of co-researchers or experts-by-experience is recommended, because they represent the target group and ensure that the intervention fits in better with this group.

At the time these elements were applied in the development of the serious game ‘You & I’, to the best of our knowledge, there was no framework available for serious games aimed at people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. In the meantime, however, Tsikinas and Xinogalos (Citation2020) developed a game design framework for serious games for people with intellectual disabilities or autism spectrum disorders. The framework they describe overlaps with our model (as reported in ) on several points. Both models include advice to involve the target group in the design process (participatory design), individualise and personalise the learning experience, define clear learning objectives, ensure immersion of the target group in the game with a simple user interface (technological accessibility) and feedback and rewards, stimulate self-learning (trial-and-error learning), and increase the level of difficulty. We also included the need to simplify, dose, and organise the exercise material and to use structure in the game and in each gaming level. These elements can complement the learning content and game mechanics part of the game design framework Tsikinas and Xinogalos (Citation2020) propose. Indeed, our newly presented model, with a focus on acquiring hard-to-learn abstract abilities and using a more structured set-up, can mutually complement the more general framework of Tsikinas and Xinogalos (Citation2020). Moreover, our model can be seen as an evolving one that can be supplemented and refined in the future by other game designers or researchers creating such games for people with intellectual disabilities.

4.1. Future directions

The game was developed through co-creation. The three co-researchers involved in the development process of the serious game ‘You & I’ provided valuable feedback and advice. In future studies, the knowledge and help of co-researchers also can be used to retrieve research questions, thus including them as ‘decision-makers’ in early stages. In this study, these co-researchers may have had higher intellectual function than other adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities based on their motivation, interest in research, and their participation in the experts-by-experience group. Thus, their advice could have led to mismatches with the broader target group. A more heterogeneous group of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities can be involved in future development processes to enable even broader representation and align the serious game (product) even better with target users.

Although the new design model is based on what is theoretically advised as a guideline for effective interventions and game elements to simulate learning and performance and to keep players involved and motivated, validating the design model as effective was beyond the scope of this work. The effectiveness of the serious game ‘You & I’ will be examined (for more details on the research design, see Derks et al. Citation2019) and reported in later work.

5. Conclusion

For people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, acquiring hard-to-learn abstract abilities can be a challenge. In this study, we presented a new human-centred and user-centred structured model based on the steps taken and elements applied in the development of the serious game ‘You & I’ for people in this population. The resulting developmental model provides an example for future game design processes for comparable and similar user groups to structure the design process, train hard-to-learn skills, and enrich the model with new insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, J. G., P. Fonagy, and A. W. Bateman. 2008. Mentalizing in Clinical Practice. London: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Baglio, G., V. Blasi, F. S. Intra, I. Castelli, D. Massaro, F. Baglio, … A. Marchetti. 2016. “Social Competence in Children with Borderline Intellectual Functioning: Delayed Development of Theory of Mind Across all Complexity Levels.” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01604.

- Bramer, W. M., M. L. Rethlefsen, J. Kleijnen, and O. H. Franco. 2017. “Optimal Database Combinations for Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Exploratory Study.” Systematic Reviews 6 (1): 245, 1–12. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y.

- Choi-Kain, L. W., and J. G. Gunderson. 2008. “Mentalization: Ontogeny, Assessment, and Application in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder.” American Journal of Psychiatry 165 (9): 1127–1135. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081360.

- Derks, S., S. Van Wijngaarden, M. Wouda, C. Schuengel, and P. S. Sterkenburg. 2019. “Effectiveness of the Serious Game “You & I” in Changing Mentalizing Abilities of Adults with Mild to Borderline Intellectual Disabilities: A Parallel Superiority Randomized Controlled Trial.” Trials 20 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3608-9.

- De Wit, M., X. Moonen, and J. Douma. 2012. Guideline Effective Interventions for Youngsters with MID: Recommendations for the Development and Adaptation of Behavioural Change Interventions for Youngsters with Mild Intellectual Disabilities. Utrecht: Dutch Knowledge Centre on MID.

- Douma, J., X. Moonen, L. Noordhof, and A. Ponsioen. 2012. Richtlijn Diagnostisch Onderzoek LVB: Aanbevelingen Voor het Ontwikkelen, Aanpassen en Afnemen van Diagnostische Instrumenten bij Mensen met een Licht Verstandelijke Beperking. Utrecht: Landelijk Kenniscentrum LVG.

- Frankena, T. K., J. Naaldenberg, M. Cardol, E. Garcia Iriarte, T. Buchner, K. Brooker, … G. Leusink. 2019. “A Consensus Statement on how to Conduct Inclusive Health Research.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 63 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/jir.12486.

- Frankena, T. K., J. Naaldenberg, M. Cardol, C. Linehan, and H. van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk. 2015. “Active Involvement of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Health Research - A Structured Literature Review.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 45–46: 271–283. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.004.

- Grossard, C., O. Grynspan, S. Serret, A. L. Jouen, K. Bailly, and D. Cohen. 2017. “Serious Games to Teach Social Interactions and Emotions to Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).” Computers and Education 113: 195–211. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.002.

- Hergenhahn, B. R., and M. H. Olson. 2001. An Introduction to Theories of Learning. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Janssen, C., and C. Schuengel. 2006. “Gehechtheid, Stress, Gedragsproblemen en Psychopathologie bij Mensen met een Lichte Verstandelijke Beperking: Aanzetten Voor Interventie.” In In Perspectief. Gedragsproblemen, Psychiatrische Stoornissen en Lichte Verstandelijke Beperking, edited by R. Didden, 67–84. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Kato, P. M. 2013. “The Role of the Researcher in Making Serious Games for Health.” In Serious Games for Healthcare: Applications and Implications, edited by S. Arnab, I. Dunwell, and K. Debattista, 213–231. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Ke, F. 2009. “A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of Computer Games as Learning Tools.” In Handbook of Research on Effective Electronic Gaming in Education, edited by R. E. Ferdig, 1–32. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Kenniscentrum Revalidatiegeneeskunde Utrecht. 2019. The involvement matrix. https://www.kcrutrecht.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Involvement-Matrix.pdf.

- Kennisplein Gehandicaptensector. 2019, November 27. Coaching, training and peer supervision for inclusive research teams. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://www.kennispleingehandicaptensector.nl/nieuws/onderzoek/gewoon-bijzonder/ervaringsdeskundigheid-netwerk-samen-werken-samen-leren.

- Landelijk Federatie Belangenverenigingen. n.d. Training Stronger Together. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://lfb.nu/workshops-trainingen/training-samen-sterker/.

- Lievense, P., V. S. Vacaru, Y. Kruithof, N. Bronzewijker, M. Doeve, and P. S. Sterkenburg. 2020. “Effectiveness of a Serious Game on the Self-Concept of Children with Visual Impairments: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Disability and Health Journal 14 (2): 1–9.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Sort, A., and Y. Khazaal. 2017. “Six Tips on how to Bring Epic Wins to Health Care.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 8: 1–6. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00264.

- Sterkenburg, P. S., and V. S. Vacaru. 2018. “The Effectiveness of a Serious Game to Enhance Empathy for Care Workers for People with Disabilities: A Parallel Randomized Controlled Trial.” Disability and Health Journal 11 (4): 576–582. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.03.003.

- Terras, M. M., E. A. Boyle, J. Ramsay, and D. Jarrett. 2018. “The Opportunities and Challenges of Serious Games for People with an Intellectual Disability.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (4): 690–700. doi:10.1111/bjet.12638.

- Tomé, R. M., J. M. Pereira, and M. Oliveira. 2014. “Using Serious Games for Cognitive Disabilities.” In International Conference on Serious Games Development and Applications, edited by M. Ma, M. Oliveira, and J. Baalsrud Hauge, 34–47. Cham: Springer.

- Torrente, J., Á del Blanco, P. Moreno-Ger, and B. Fernández-Manjón. 2012. “Designing Serious Games for Adult Students with Cognitive Disabilities.” In Neural Information Processing, edited by T. Huang, Z. Zeng, C. Li, and C. S. Leung, 603–610. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer .

- Tsikinas, S., and S. Xinogalos. 2018. “Studying the Effects of Computer Serious Games on People with Intellectual Disabilities or Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 35 (1): 61–73. doi:10.1111/jcal.12311.

- Tsikinas, S., and S. Xinogalos. 2020. “Towards a Serious Games Design Framework for People with Intellectual Disability or Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Education and Information Technologies 25: 3405–3423. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10124-4.

- Van Nieuwenhuijzen, M., A. Vriens, M. Scheepmaker, M. Smit, and E. Porton. 2011. “The Development of a Diagnostic Instrument to Measure Social Information Processing in Children with Mild to Borderline Intellectual Disabilities.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 32 (1): 358–370. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.10.012.

- Wang, L.-C., and M.-P. Chen. 2010. “The Effects of Game Strategy and Preference-Matching on Flow Experience and Programming Performance in Game-Based Learning.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 47 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1080/14703290903525838.

- Whyte, E. M., J. M. Smyth, and K. S. Scherf. 2015. “Designing Serious Game Interventions for Individuals with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45 (12): 3820–3831. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2333-1.

- Yirmiya, N., O. Erel, M. Shaked, and D. Solomonica-Levi. 1998. “Meta-analyses Comparing Theory of Mind Abilities of Individuals with Autism, Individuals with Mental Retardation, and Normally Developing Individuals.” Psychological Bulletin 124 (3): 283–307. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.283.