ABSTRACT

Research in human–computer interaction (HCI) has identified meaning as an important, yet poorly understood concept in interaction design contexts. Central to this development is the increasing emphasis on designing products and technologies that promote leisure, personal fulfillment, and well-being. As spaces of profound historical significance and societal value, museums offer a unique perspective on how people construct meaning during their interactions in museum spaces and with collections, which may help to deepen notions of the content of meaningful interaction and support innovative design for cultural heritage contexts. The present work reports on the results of two studies that investigate meaning-making in museums. The first is an experience narrative study (N = 32) that analyzed 175 memorable museum visits, resulting in the establishment of 23 triggers that inform meaningful interaction in museums. A second study (N = 354) validated the comprehensiveness and generalisability of the triggers by asking participants to apply them to their own memorable museum experiences. We conclude with a framework of meaning in museums featuring the 23 triggers and two descriptive categories of temporality and scope. Our findings contribute to meaning research in HCI for museums through an articulation of the content of meaning-making in the cultural sector.

1. Introduction

In recent years, design research has increasingly called for the creation of moments of meaning (Hassenzahl et al. Citation2013), meaning-making (Bødker Citation2015), and meaningfulness (Lukoff et al. Citation2018) during interaction with products, technologies, and services. Similarly, in the cultural sector, design researchers have argued for the necessity to cultivate meaningful engagement with collections (Vermeeren et al. Citation2018), meaningful experiences for individuals and groups, both on-site and online (Perry et al. Citation2017), meaningful reflections (Alelis, Bobrowicz, and Ang Citation2013), and contextually aware, personally meaningful visitor interactions (Not and Petrelli Citation2018). This shift in experience design to prioritise moments of profound significance, personal relevance, well-being, and value generation are a logical development of third-wave HCI, which emphasises the non-rational, non-instrumental, emotional, and experiential qualities of interaction (Bødker Citation2015; Hassenzahl et al. Citation2013; Hassenzahl and Tractinsky Citation2006). However, as recent work has demonstrated, understanding meaning as a quality of interaction within HCI remains in its early stages (Mekler and Hornbæk Citation2019), and as we will discuss herein, research in the cultural sector has similarly not established a comprehensive view of meaning across the broad spectrum of the museum visit.

In the present work, we argue for an overarching framework of meaning and meaningful design in museum contexts that builds on previous work in museum memory studies, museum experience design, and human–computer interaction. In their recent framework of meaning, Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2019) demonstrate the proliferation of the term and its variants (e.g. meaningful) in HCI contexts, signalling the growing importance of meaning to contemporary interaction design and its simultaneous lack of conceptual clarity in the literature. A similar challenge exists within the cultural sector. In some cases, the creation of meaning depends on personal relevance or individualistic qualities of interaction (Not and Petrelli Citation2018; Marty Citation2011), whereas in other cases meaning arises as a result of engagement with technologies (Perry et al. Citation2017; Maye et al. Citation2014), or even collective social interaction around museum objects (Vermeeren et al. Citation2018; Ciolfi and Petrelli Citation2015). Prior work has informed our understanding of individual aspects of meaning-making in museums, but in consideration of increasing calls for meaningful interaction, we argue that developing a comprehensive overview of the content of meaningful experiences in museums has value for future design.

This research comprises two studies. First, we introduce an experience narrative study on memorable museum visits, from which we derived a series of 23 triggers that represent the content of meaning in the museum context. In this first study, we aimed to answer precisely which phenomena during the museum visit resulted in meaningful experiences for visitors. Drawing on the work of Falk (Citation2009) and Falk and Dierking (Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2013), who demonstrate the salience of museum memories as a kind of visitor archive of meaning-making, we analysed the memorable visits of 32 participants to uncover which experiences led to meaning-making, indicated by the establishment of long-term museum memories. Thereafter, we conducted a validation study on the 23 triggers to confirm their comprehensiveness and generalisability for future museum experience design. The results of the two studies informed the creation of the My Museum Experiences (MyMuEx) framework, a tool to support meaningful design in museum spaces, whether physical or digital. As a consolidated collection of meaningful triggers in museums, this research advances museum experience design in two ways: first, it provides new insights into the content of meaningful experiences that museums afford their visitors, and second, it presents design recommendations using the MyMuEx framework and related MyMuEx ideation cards to support design in the cultural sector.

2. Related work

In consideration of what makes interaction good, researchers in HCI have turned their attention to the concept of meaning and its potential contributions to interaction design (Mekler and Hornbæk Citation2019). This new focus on meaning and meaning-making has emerged within the field’s third-wave, which emphasises the experiential, non-instrumental qualities of interaction with technologies, products, or services (Bødker Citation2015). In the following, we trace the development of meaning within the context of HCI, focusing primarily on motivation and psychological need fulfillment, user experience design (UX), and the integration of sociocultural critique, such as feminism and critical theory. We then consider meaning from the museum context, in which we demonstrate that despite the growing number of context-specific design approaches to enrich museum settings, few studies exist that contribute to a more generalisable approach for meaning within the cultural sector.

2.1. Meaning and interaction design

Within third-wave HCI, research has increasingly focused on the complex interplay of factors that afford moments of happiness, well-being, and pleasure (Hassenzahl et al. Citation2013). These developments are, in part, an extension of early work in self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) and psychological need fulfillment (Sheldon et al. Citation2001a), which demonstrate an innate human striving for fundamental qualities of experience – namely autonomy, competence, and relatedness – that can lead to the creation of meaning and personal thriving. Moreover, in fulfillment of these psychological needs, individuals can develop a sense of intrinsic motivation in relation to an interactive experience, allowing for enhanced learning, creativity, and engagement (Ryan and Deci Citation2001; Peters, Calvo, and Ryan Citation2018).

Connecting these ideas to design more generally, Jordan (Citation2002) frames interaction through the lens of pleasurable experiences. His framework on the four pleasures details the physical, cognitive, social, and values-based qualities of pleasure that can promote a deeper connection between users and interactive products. A similar approach appears in Norman’s (Citation2004) three levels of emotional design, which posit visceral, behavioural, and reflective components. The framework considers not only aesthetic value and usability, but also the ways in which people come to develop relationships with products or even self-identify with them over time. Altogether, these frameworks established the importance of going beyond mere usability to consider notions of context, affect, and subjective experience.

Along with these developments, early work by Hassenzahl, Burmester, and Koller (Citation2003) and Hassenzahl and Tractinsky (Citation2006) in user experience (UX) contrasts the instrumental and non-instrumental qualities of a product, service, or technology. The authors identify the pragmatic (usable, efficient) and hedonic (affective, pleasurable) elements of interaction, reconceiving UX as a consequence of a given user (or users) in a particular context making use of a designed system. Within psychology, work by Huta and Waterman (Citation2014) consolidated a third category of experience, eudaimonia, which refers to transformational aspects of human interaction that contribute to self-development, self-actualisation, and personal thriving. Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2016) later introduced eudaimonia to the HCI community, noting that some positive user experiences had qualities that exceeded the conceptual definition of hedonia. These experiences, such as a sense of well-being, self-realisation, or personal fulfillment occur, they argue, as a result of eudaimonic qualities of interaction. Altogether, experiences that balance a careful interplay of efficient usability, pleasurable stimulation, and a sense of well-being may trigger moments of meaning for users. However, understanding meaning itself as a quality of interaction has nevertheless remained elusive (Mekler and Hornbæk Citation2019).

The recent framework of meaning by Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2019) is perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of meaning in the context of HCI and interaction design. The framework introduces five elements of meaning: connectedness, purpose, coherence, resonance, and significance. Each element describes a unique aspect of meaning in both its manifested state as well as in its absence, indicating that meaning corresponds to feelings of connection with the world, to one’s own goals, to sensemaking, to an intuitive feeling of rightness, and to an experience having enduring value or significance. The authors note that while the framework has much to say about the experience of meaning, it remains silent regarding its content, which is precisely the focus of the current study.

Finally, advances in feminist and critical theory for HCI have offered an alternative view into meaning through a critical reflection on fundamental assumptions common to the field. For example, Bardzell (Citation2010) argues that design universality, its process models (e.g. agile), and evaluation methods (e.g. mental models) have inherent associations with masculinity, advocating instead for the adoption of feminist epistemologies into HCI research. Related work has demonstrated the role of gender in the design of domestic technologies (Cockburn Citation1992; Taylor and Swan Citation2005), as well as the pervasive encoding of racist and other discriminatory practices into the conceptualisation of the algorithms and technologies governing our lives (Benjamin Citation2019). Along a similar trajectory, critical theorists have argued for decolonising and other social justice-oriented methodologies within interaction design to counter epistemic privilege, racism, alterity, and colonial ideologies in the design of interactive systems (Bardzell, Bardzell, and Blythe Citation2018; Dourish Citation2018; Grinter Citation2018). While these developments are still in their nascency, they support meaning-making and personal well-being through the equitable representation and inclusion of users, the dismantling of oppressive norms, and the adoption of a more just design ethos. This shifting design philosophy resonates with the Mekler and Hornbaek framework insofar as it has the potential to address the lived realities of marginalised people (e.g. coherence), align with their goals (e.g. purpose), and create enduring value (e.g. significance).

2.2. Meaningful museum experiences

Just as feminist thought and critical theory have identified epistemological and methodological challenges within the field of HCI, so too does this critical reflection have a direct parallel within contemporary museology. Participatory and decolonising methodologies have become an essential consideration of museum experience design, aiming to subvert notions of ‘authorized heritage discourse’, to include the public in the design of cultural heritage experiences, and to encourage museums to more adequately reflect the communities they serve (Vermeeren et al. Citation2018; Morse et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Perry et al. Citation2017; Smith Citation2006). In creating meaning for museum visitors, therefore, it is important to investigate meaning from the context of the visitor directly, which is an essential aim of the present study.

Meaning within the cultural sector has taken many forms in the literature, comprising the memorable (Falk and Dierking Citation1995; Henry Citation2000; Kostoska et al. Citation2013), the emotional (Bedigan Citation2016; Shih, Yoon, and Vermeeren Citation2016; Norris and Tisdale Citation2017; Perry et al. Citation2017), the transformational (Kirillova, Lehto, and Cai Citation2017; Soren Citation2009), the empathic (Gökçiǧdem Citation2016), the relevant (Simon Citation2016), the embodied (Kenderdine, Chan, and Shaw Citation2014; Kidd Citation2019), the aesthetic (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1990), the serendipitous (Makri et al. Citation2019), and the ineffable or numinous (Boehner, Sengers, and Warner Citation2008; Latham Citation2009). The intricacies of the museum visit represent a complex interplay of emotion, cognition, and context, which ultimately coalesce into an experience that can remain with people for the entirety of their lives (Falk and Dierking Citation1995, Citation2013). Across these various dimensions, meaning appears as a pervasive element to the design of museum spaces and interactive systems, but many challenges remain. The aforementioned case studies do not offer any formalised system to understand meaning across different contexts and are more often project specific. However, as individual representations of meaning, they serve as a basis for understanding the complexity of the concept insofar as it relates to the museum visitor experience. To address this gap, we establish the museum memory as a fundamental unit for comprehending meaning in museum contexts.

In their early work on the visitor experience of museums, Falk and Dierking (Citation1995) demonstrated the persistence and salience of memories of past museum visits. For example, it is not uncommon for people to share memories of childhood visits to museums, a phenomenon that holds true in the present study as well. Henry (Citation2000) further substantiates this claim about the importance of museum memories, noting that the curation of an exhibit and the quality of preparation for the visit have an important impact on sustaining meaning after the fact. Preliminary research has also suggested that the collection and sharing of museum memories can lead to increased interest in the museum by others, including those who are unable to visit in person (Kostoska et al. Citation2013).

Falk and Dierking (Citation2013) explored the complexities of museum memories and their temporal significance in a longitudinal study, which found that identity-related motivational preferences had a significant impact on the creation of meaning for visitors, down to the ways in which their memories were structured and recalled. This closely aligns with Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2019), who argue in their framework of meaning that memory is directly implicated by the complex process of self-identification and self-awareness that mediate our beliefs, values, and behaviours. Building on this work, we hypothesise that peoples’ recollections of past visits can adequately express the complexities of the museum experience, not only regarding time spent in-situ, but also in the articulation of varying temporalities and subjectivities. Falk’s (Citation2009) seminal work on museum visitor motivations identifies five museum personas (), each representing a particular identity-related motivational orientation underlying the museum visit. For the purposes of this study, we have adopted this model to better understand how these motivational factors can influence meaning-making.

Table 1. Falk’s (Citation2009) museum personas based on identity-related motivations for the museum visit.

Concerning the content of museum meaning, we draw primarily from the work of Soren (Citation2009), whose study on transformational experiences in museums identified ten unique triggers: attitudinal, authentic, behavioural, being witness, cultural, emotional, motivational, sublime, traumatic, and unexpected. These initial triggers are a useful starting point to understand the varieties of museum experiences. However, there is still a need to provide more nuanced support from a design standpoint. For example, the emotional trigger may theoretically comprise any number of emotions (e.g. nostalgia or excitement), and we hypothesise that emotional responses to museum experiences are more likely the products of triggers and not the triggers themselves, as we see in cognitive appraisal patterns in interaction design contexts (Demir, Desmet, and Hekkert Citation2009).

Similar work has attempted to classify the museum experience from the standpoint of phenomenology. A study on the UX of museum technologies by Pallud and Monod (Citation2010) argued for a phenomenological approach to the design and evaluation of museum technologies to support meaning-making. The resulting framework identified six categories of experience: historicity, possibilities of being, self-projection, embodiment, re-enactment, and context. While appropriate for certain museum contexts, namely heritage sites, this framework emphasises connection to historicity and re-enactment of the past in lieu of additional trigger categories that may also impact the visit itself. For example, Falk and Dierking (Citation2013) argue that exhibitions are only one aspect of the visit and distinguish between the predictable and idiosyncratic behaviours of visitors that can lead to different kinds of experiences (e.g. encountering a stranger, or having a negative experience with museum staff). In attempting to encapsulate the museum visit more comprehensively, our study acknowledges informal, unexpected experiences together with more predictable and expected visit outcomes.

2.3. Going beyond state of the art

We have demonstrated that while notions of meaning and meaningful design are increasingly cited within both HCI and museum experience design literature, these concepts are still quite recent and not fully articulated to adequately support the work of cultural professionals. Meaningful experiences appear to have a relationship to self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), psychological need fulfillment (Sheldon et al. Citation2001b), and positive psychology (Huta and Waterman Citation2014), though additional work is necessary to apply these abstract frameworks to museum exhibitions and collections more broadly. From the standpoint of UX design, researchers have shown that particular interaction qualities may lead to the development of meaning for users – such as the experience of connectedness or coherence as described by Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2019) – but this does not uncover the content of meaning in museums. Previous work on the classification of meaning in the cultural sector have embraced the complexity and inherent subjectivity of the museum experience, drawing on memories, narrative, and phenomenological analysis (Falk and Dierking Citation1995; Pallud and Monod Citation2010; Soren Citation2009) to identify universal experiences. The present work builds on these initial studies, aiming to create a comprehensive and actionable framework of meaning for the museum context.

3. Research questions

The objective of this research project is to advance our understanding of meaning in museums and to provide a framework for the design of meaningful museum experiences. To this end, we conducted two studies. For the first, we invited museum visitors to our user lab to discuss their most memorable museum experiences with the objective of identifying triggers for meaningful experiences.

RQ1: What are the triggers that foster meaningful experiences in museums?

In a second experiment, we sought to validate the comprehensiveness of the identified triggers by asking a large online panel to share one memorable museum experience and to select the triggers related to it.

RQ2: (a) Do the identified triggers comprehensively encompass the varieties of meaningful museum experiences? (RQ2-1)

(b) How do museum visitor types and other demographic factors correlate with meaning in museums? (RQ2-2)

4. Study I: what makes a museum experience meaningful?

The first experiment aimed to distinguish the types of triggers that resulted in meaning-making during the museum visit through an analysis of museum memories (RQ1). In the consolidation of experience, the remembering self is more closely tied to a person’s identity, including notions of prior beliefs, recent events, and cognitive biases (Beal and Weiss Citation2003; Mekler and Hornbæk Citation2019). Building on the constructive nature of memory, we sought to understand the creation of meaning not through precise, accurate reflections of objective events, but by delving into the thoughts and beliefs of participants made available through their recollections (Rathbone, Conway, and Moulin Citation2011).

4.1. Participants

Study 1 was conducted as individual interview sessions of about one hour in the University of Luxembourg User Lab. We recruited 32 participants in Luxembourg and the surrounding region via social media (Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn) and through poster advertisements in public spaces. The participants were ages 19–70 (M = 34.66, SD = 11.28) and represented 18 nationalities. While theoretical saturation is hard to predict, we followed local standards in HCI (Caine Citation2016) as well as generic recommendations in qualitative research (Hennink and Kaiser Citation2022) to define our sample size (which in our case relates to both the number of interviewees and the number of experience narratives reported). In order to take part in the study, participants had to be at least 18 years old and have at minimum one memorable museum experience. We emphasised that the study was open to the public and not catered solely to art lovers or avid museumgoers, which we confirmed using demographic data such as number of annual visits or museum persona type. The study received prior approval from the university ethics committee, and all participants provided their informed consent before taking part. Additionally, participants received compensation for their time in the form of 20 EUR gift vouchers. We video recorded each session and transcribed the data using the software Atlas.ti. In the subsequent sections, we distinguish between participants in the following manner: StudyNumber_ParticipantNumber (e.g. S1_P13 or S2_P301).

4.2. Procedure

In advance of each session, we instructed participants to consider five to ten memorable museum experiences they have had in their lifetimes, positive or negative. All participants received the following instructions by email:

Consider five to ten memorable museum experiences you have had at museums, positive or negative. Reflect on why those experiences were memorable for you.

Find an image that represents the experience (e.g. a photo of the artwork, exhibit, or institution) either taken by you or found on the internet.

Before your session, upload your images to the secured folder provided to you.

Prior to beginning the interviews, we printed out the images provided by participants. These images served as guides to remind participants of their experiences during the sessions and to provide us with additional context. Each image represented one unique experience. Additionally, we prepared experience narrative report forms for participants to fill out during their interviews. Experience narratives are an established method for collecting salient experiential data. Narratives offer a natural way to structure and understand information experienced over time, and in doing so can allow designers to empathise directly with users (Grimaldi, Fokkinga, and Ocnarescu Citation2013). The experience narrative report allowed participants to summarise their experiences using free-form keywords, an overall rating (Likert scale; 0 – very bad, 10 – very good), and finally, the Geneva Emotion Wheel (GEW; see Scherer Citation2005; Scherer et al. Citation2013), which allowed participants to self-declare the emotions they recalled feeling during each of their museum visits.

We then instructed the participants as such:

Choose one of the experiences you prepared for today and briefly describe it, indicating why it was memorable for you (1–2 min).

After discussing the experience, complete an experience narrative report provided to you. You will fill out one experience narrative report per experience you describe. As you complete the report, or immediately after completing it, please briefly explain your selections.

Move on to your next experience.

4.3. Data analysis

We transcribed all interview sessions verbatim using the qualitative analysis software Atlas.ti. During the first round of analysis, two authors individually performed open coding and thematic analysis (Blandford, Furniss, and Makri Citation2016) on 5 of the 32 sessions (totaling 28 individual memories; ∼16% of the data) with the aim of identifying the individual triggers that resulted in a meaningful experience. We then reconvened and compared their results, which included 38 potential triggers altogether. As an example, we created the code nostalgia for those experiences relating to a feeling of longing for childhood as a result of a visit. Early codes often included specific emotional states as described by the participants, such as a feeling of surprise or wonderment.

During the second round of analysis, we performed axial coding on the resulting triggers to determine the relationships between them to consolidate redundancies and remove those that were not actual triggers. We used the experience narratives from the original 5 interviews as guides to understand the quality, valence, and intensity of the experience, and defined each trigger with a positive and negative interpretation. For example, the trauma trigger may reference both feelings of despair and catharsis, depending on the context in which it arises. Additionally, we combined some triggers, such as nostalgia (longing for one’s own lived past) and longing (longing for a specific time or place not personally lived) – into fondness, which represents a desire for (or aversion to) any location or era, personally lived or not. Finally, we removed triggers that represented specific emotions such as those listed on the GEW, as the emotions themselves were typically the result of the triggers rather than the triggers themselves. We concluded with 20 triggers after this consolidation round.

Finally, using deductive coding we applied our consolidated triggers to the full dataset, associating the various triggers with the individual memorable experiences. During this round of analysis, we identified three additional triggers, totaling 23 altogether.

4.4. Results

Our analysis of the experience narratives identified 23 triggers that lead to memorable museum experiences (). Each trigger can have a positive or negative valence, and individual museum experiences typically combine multiple triggers. As an example, a participant from Study 1 described their experience visiting the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Cambodia:

It’s the saddest museum I’ve ever been to … Because of the pictures they used, and the descriptions of the tortures and everything. It made me very emotional, because if you have a good imagination, you can picture right here, this person being tortured in this particular way. And actually, they keep the torture tools there and the pictures before and after. Because the Khmer Rouge people were very good at documenting what they were doing, so they took pictures of every prisoner before and after the death. So now they have all these pictures in this museum exhibited, you can see all these people, like hundreds of people who were kept in this prison. (S1_P31)

Table 2. Museum experience triggers and associated descriptions.

Another example comes from a participant who described their encounter with Michelangelo’s The Damned Soul, a drawing on display at the Uffizi Gallery in the 1970s:

I love Michelangelo drawings, so I went to see it. And I’d never seen this. It had never been published or anything so it was very new to me. And at that age I was coming from an upbringing which was controlled, disciplined, and socially repressed. The image I saw … this told me you can express your passion, you can express your emotion, you can share what’s inside you and shed the repressive upbringing. And every time I look at this image – I had this blown up into a 1.5 by 2 meter headboard of my bed for a year and a half until I went to flying school in the Air Force. Every time I walked in my room, every time I went to bed, every time I woke up in the morning it was a reminder. (S1_P16)

A final example comes from a performance art piece by Marina Abramović, which famously situates nude performers along a purposefully narrow exhibit entrance, ultimately forcing visitors to brush up against the performers’ naked bodies in order to enter.

This one, it was a performance of Marina Abramović in Moscow. It was an exhibition to some extent, but yeah … the key idea was about naked people that were everywhere. And even to enter to the whole of the exhibition you have to pass here [through two naked people], and I felt a little bit confused. It was okay for me, I just passed, but my future husband, he was disturbed a little bit because he didn’t know which way to go through. Should he put himself facing the woman or the man? Which side to turn and which side to enter? But I think it was my first memorable experience of visiting a performance exhibition. (S1_P26)

5. Study II: museum experience triggers at scale

In the process of building a framework for meaning in museums, Study 1 enabled us to identify 23 triggers that lead to the creation of memorable museum experiences. The objective of the second study was to assess the comprehensiveness of the framework across a large range of visitors in varied contexts (RQ2-1). Furthermore, Study 2 investigated the correlations between triggers and demographic factors (RQ2-2).

5.1. Participants

We conducted the study as an online survey hosted on LimeSurvey and distributed via the participant recruitment platform Prolific.co. The study received prior approval from the university ethical board, and all participants provided their informed consent before taking part. Participants received financial compensation of 2.95 USD for taking the 15-minute survey. We gathered valid answers from 353 participants, representative of the US population in terms of gender, age, and ethnic origin. We asked participants to report their highest level of education, the number of times they visit museums on average per year, and to self-identify as one of five museum personas (). Their demographic distribution was as follows:

Gender: 179 female, 171 male, 3 non-binary

Age: 19–78 years (M = 45.7; SD = 16.24)

Education: 3 participants had no formal qualifications (.8%), 112 had a high school diploma (32%), 26 had completed trade school (7%), 153 held a bachelor’s degree (43%), 48 held a master’s degree (14%), and 11 had a PhD (3%).

Annual visits: 158 reported visiting museums about once per year (∼45%), 159 visit between 2–5 times per year (∼45%), 22 go between 6–10 times per year (6%), and 14 go more than 10 times per year (4%).

Museum personas: 44 Experience Seekers (12%), 264 Explorers (75%), 10 Facilitators (3%), 18 Professional/Hobbyists (∼5%), and 17 Rechargers (∼5%).

5.2. Museum memories

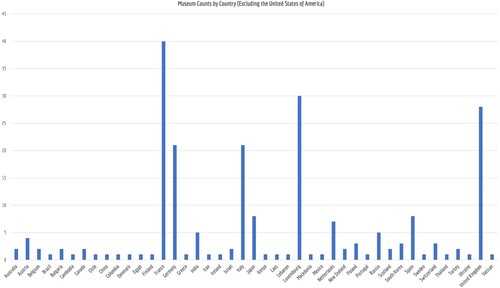

Across the two studies, we collected 539 individual museum memories representing institutions from around the world. visualises these institutions by location, which include art museums, science museums, (natural) history museums, built heritage, nature conservancies, children’s museums, and other institutions of varied specialities. Participants had no limitations on the type of museum they could reference so long as it had relation to tangible and/or intangible cultural heritage. Most museums were located in the United States (n = 316; 59%), and the remaining museums were spread across 43 other countries. shows counts for each country excluding the US.

5.3. Procedure

The first section of the survey collected demographic information. The survey then asked participants to reflect upon and describe a single memorable museum experience they have had in the past. Thereafter, participants were presented with the 23 triggers from Study 1, randomly distributed. They were instructed to select all triggers they deemed relevant as to why their experience was memorable. Additionally, for each trigger selected, the survey asked participants about the trigger’s valence (positive or negative) via a 5-point Likert scale (−2 very negative to +2 very positive). Finally, participants had the opportunity to provide additional triggers of their own if they felt their experience was not fully represented by the original 23. For those participants who provided new trigger suggestions, it was not necessary for them to name the triggers explicitly, but merely to describe them in brief detail.

5.4. Data analysis

To assess whether the identified triggers encompassed the varieties of meaningful museum experiences (RQ2-1), we analyzed the frequency of each trigger, as well as each trigger’s valence mean from the 5-point Likert scale rating. To identify typical trigger pairings, we analyzed correlations between trigger selections and ran a tetrachoric factor analysis to identify closely related triggers.

We imported the qualitative data into Microsoft Excel and deductively analyzed the trigger suggestions provided by participants in order to determine whether they fit into existing triggers or if additional triggers were necessary. Three authors participated in the procedure. One author classified each trigger suggestion as either existing, irrelevant, or to be discussed. Thereafter, the remaining two authors viewed each classification and signalled their agreement or disagreement. Finally, the group deliberated on those trigger suggestions listed as to be discussed to reach a consensus.

In addition to the 23 triggers, two descriptive categories emerged relating to the temporality and scope of the various experiences described by participants. Temporality refers to influences on the triggers that occur before, during, and/or after the museum visit, such as reflecting on a museum visit throughout one’s life or having prior knowledge about an exhibit before arriving. Scope indicates the impact of a trigger across three categories: individual (a single person), community (a small group or community of people), or society (diverse groups of people, national/international contexts). For example, a shared family visit has a scope of community. We furthermore deductively coded the experience descriptions based on these descriptive dimensions of the museum experience.

To derive insights on how to employ triggers to target specific audiences (RQ2-2), we calculated the average trigger occurrence with standard deviation for the five different museum visitor types (as selected by the participants themselves), as well as for the different demographic groups (gender, education, frequency of museum visits). Finally, we ran logistic regressions for the categories: museum persona, gender, age, education, and frequency of museum visits for each trigger. This allowed us to identify which triggers were never selected by a category of participants and which were significantly more/less relevant for certain categories.

In running the regression analysis, we had to exclude data from 3 non-binary (those who selected neither male nor female) participants because the sample size was too low. To analyze triggers by education, we chose academic degrees above Bachelor as the baseline for the logistic regression because research has shown that people with higher levels of education visit museums significantly more often (Farrell and Medvedeva Citation2010). This is also the case in our study where we see a positive correlation between education and frequency of museum visits (r = 0.17, p < 0.05). By doing so, our results can point out triggers that are more (or less) relevant for an audience other than the most frequent museum visitors (baseline population). Consequently, exhibition designers can address (or avoid) these particular triggers if they want to enhance the attractiveness of an exhibition for less museophile populations.

5.5. Results

We conducted Study 2 to validate the comprehensiveness of the 23 triggers from Study 1 (RQ2-1). Additionally, we investigated the role of other influences relating to the triggers and their selection, such as demographic factors, trigger correlations, and the descriptive categories of temporality and scope (RQ2-2).

5.5.1. Trigger frequency and comprehensiveness

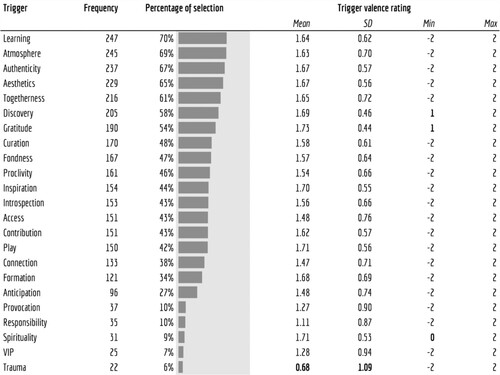

All proposed triggers were selected multiple times. indicates the selection frequency for each trigger. The museum experience triggers selected by over half of all participants were learning, atmosphere, authenticity, aesthetics, togetherness, discovery, and gratitude. The least selected triggers were trauma, VIP, spirituality, responsibility, and provocation.

While museum experiences can be memorable for positive or negative reasons, we found that almost all the triggers selected by the participants had a positive valence, except for trauma (M = 0.68, SD = 1.09). Most of the triggers received valence ratings covering the whole spectrum from −2 (very negative) to +2 (very positive). However, some distinctively only received ratings on the positive side, namely the triggers discovery, gratitude (from +1 to +2), and spirituality (from 0 to +2) (see ).

Altogether, 54 participants (15%) provided suggestions for alternative triggers. Many of the responses related to emotional states or situations that we considered to already fit within the existing categories, and as such we did not add any new trigger categories. For example, one participant wrote:

My mother was an artist, who grew up in New York. Having so recently lost her, visiting the museum in New York brought me closer to her, and was comforting. It was also a relief from grief, in that I was able to enjoy the experience with my daughters. View the artwork, laugh at what we found amusing and appreciate the museum. (S2_P220)

Additionally, a number of participants related experiences of feeling connected to historical figures, or different perspectives across history. For example, S2_P366 wrote ‘I appreciated [the] historical perspective of science’, and another added,

Did the experience open up new avenues of compassion, empathy, and understanding of a historical event or time period? (S2_P308)

Moreover, some participants discussed interactivity in the context of digital technologies:

I don’t think this was represented, a category reflecting digital/virtual experiences as a lot of exhibits can now be viewed online or have extras that allow for interacting with smart phones. (S2_P165)

5.5.2. Correlated triggers

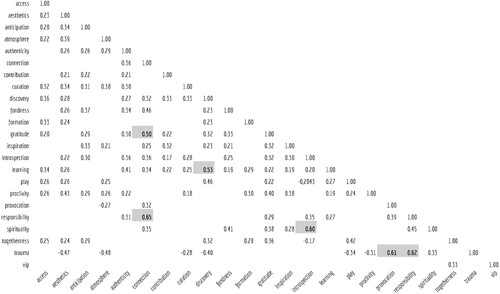

A great number of the triggers are significantly correlated (). In our sample of reported museum experiences, most triggers occurred as combinations.

Figure 4. Tetrachoric correlations between museum experience triggers for N = 353, highlighted numbers p < 0.05.

Positive correlations that stand out include spirituality with introspection (r = 0.60), trauma with responsibility (r = 0.62) and with provocation (r = 0.61), connection with responsibility (r = 0.65) and with gratitude (r = 0.50), as well as discovery with learning (r = 0.53).

5.5.3. Triggers by visitor types

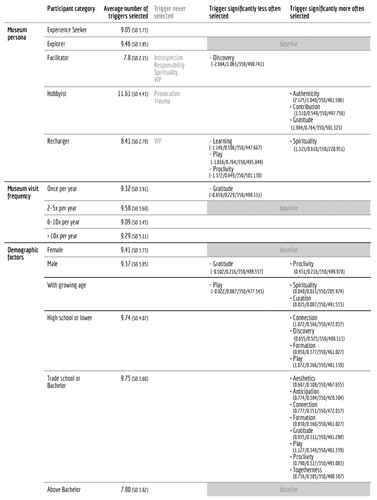

Participants in Study 2 selected on average 9 triggers (M = 9.42; SD = 3.82). The total number of average triggers selected appears in . Professional/Hobbyists selected significantly more triggers (M = 11.61, SD = 4.43) compared to the other visitor types (t = −2.5156 diff! = 0 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0123).

Figure 5. Triggers by participant category; values in parentheses: logit coefficients/standard error/observations/BIC; p < 0.05.

In the selection of specific triggers, we found the following significant differences: Facilitators never selected introspection, responsibility, spirituality, or VIP. Additionally, discovery was less relevant for them as compared to the baseline group Explorers. Hobbyists selected neither provocation nor trauma; moreover, authenticity, contribution, and gratitude were more relevant for them than for the baseline group. Rechargers never selected VIP; learning, play, and proclivity were less relevant, and spirituality was more relevant for this group.

5.5.4. Triggers by demographics

Gender: In terms of gender, we found few significant differences between the triggers selected. Regression logistics only revealed that compared to female museum visitors, gratitude was a less relevant trigger and proclivity was a slightly more relevant trigger for male participants (see ).

Education: In , we see that the baseline group (above bachelor’s degree) selected less triggers than the others. Depending on the museum visitors’ educational level, we found differences between what triggered memorable experiences. People with a high school degree or lower selected trauma less often as a trigger. Moreover, the triggers connection, formation, discovery, and play were more important for these visitors. Aesthetics, anticipation, gratitude, proclivity, and togetherness were valued higher by museumgoers with less than bachelor but higher than high school degrees.

5.5.5. Additional dimensions for memorable museum experiences

Triggers were not solely limited to the in-person experience of the museum but persisted across time as well. Different temporalities emerged during the qualitative data analysis, and in categorising these elements we adapted work from Falk and Dierking (Citation2013) on the museum visit as a spectrum of experiences that include before, during, and after the visit. A similar approach can be found in the UX over time framework by Karapanos et al. (Citation2009), which posits the following temporal dimensions: anticipation (a priori expectations for the visit), orientation (initial experience and cognitive appraisal of the product/service), incorporation (reflection on how the experience is meaningful), and identification (how the experience relates to self-identity). However, as the temporality framework of Karapanos et al. was designed originally for use with interactive products over time, rather than individual experiences that participants may reflect on over time, we separated temporality (experiences over time) and scope (effect of experience on self and other) during the qualitative analysis.

5.5.6. Temporality

Museum experiences shared by participants represented different temporalities, including before, during, and after the experience, as well as atemporal. Experiences coded as before typically included some element of anticipation, prior experience, or personal connection. For example, in describing a trip to the Penn State University Earth and Mineral Science Museum, a participant stated that it was memorable because

they had a large display of fossils, rocks, and geographical features. One of the most memorable displays for me at this was a showing of materials that absorb energy during the day and can be used to heat a home at night. I was given an opportunity to work on a project developing such a material in the past, so being able to see and interact with a novel material like this was pretty impactful. (S2_136)

I went to the Holocaust Museum as a student. It was a cold and rainy day which added to the somberness of the experience. I was with a small group - maybe a dozen other students and some chaperones. I was in middle school. We’d read a lot of books and we’d been educated in what to expect, but from a Catholic viewpoint that was more about Catholic ‘saviors’ than victims. I was interested in how people who lived through the experience survived. I was also interested in how the machinery of the camps operated, how the German people lived in and around it all, how the camps were. It was all very scary and very interesting at the same time. (S2_P116)

Memorable experiences during the museum visit represent both the expected and unexpected, or as Falk and Dierking (Citation2013) describe, the predictable and the idiosyncratic. Often, museum collections triggered a meaningful experience:

This was a visit to the Met in NYC back in 1996. It always stands out for me because while I had known of the paintings of Ingres, I had never had the opportunity to stand in front of one for quite so long. It’s the painting of the Princess Josephine – the lady in the blue dress. I was particularly taken by the folds and pleats in the dress on the left-hand side of the painting. Her face was beautiful but there was something about the way the dress itself was painted that was mesmerizing to me. I was with my (now) wife, and we were both so drawn to the image – we must have stood there for at least an hour. I was looking at the dress, but I had a funny feeling like time itself had stopped. This sometimes happens to me when I see a work of art that I love, but this was the most intense. It was as though I were inside the painting … Afterward we both talked about the experience and it was as though we had been hypnotized in some delightful way. (S2_P126)

I had taken my family to C.A.L.M. California Animal Living Museum in Bakersfield, CA. My son was about 3 at the time and my daughter 7. They had an exhibit that allowed children to interact with worms. All kinds of different worms were there for the kids to play with. My son was looking at a particularly long earthworm when he grabbed it by both ends and bit it in half. I squealed and tried to hide said worm before the curator came over to see what had happened. (S2_P84)

One of my most memorable experiences was visiting the Hong Kong Museum of Science. The outside had a modern look and the inside was spectacular. I was in my teens at the time and I really enjoyed exploring the museum and seeing the different exhibits they had on. They had many educational and hands-on features like a telephone or working with fake dinosaur bones. They even had a mirror exhibit showing how mirrors and light work, which was really fun. I think this experience is what pushed me to become an engineer. (S2_P46)

For me it’s memorable because every time I go there my perception changes all the time. It started as this very impressive – like the foreignness – how Britishness was seen as a foreign thing, and the cliché of London in my head as a teen. And then it evolved into something more regular that I really liked, so that you understand a bit more the history of the collections, and that it’s the biggest crime scene there is in the art world because all the stuff actually belongs to other people and was stolen through colonial history. It’s very memorable for me because I can go there and see the same things, but my overall perception of the museum is changing and way more critical I guess. (S1_P28)

5.5.7. Scope

Finally, patterns emerged regarding the specific impact triggers had on, and in relation to, museum visitors. We defined these as individual, community, and society, which build on work from Falk and Dierking (Citation2013) who distinguish between the personal and sociocultural aspects that inform the museum experience. Meaningful experiences occurred not only as a result of isolated objects, artworks, or spaces, but also resonated with the larger missions of museums to effect change across personal, communal, and societal contexts.

Some experiences were entirely personal, such as one person's visit to the Musée du Louvre in Paris:

It was 2000 and I was traveling through Europe by myself just after graduating from college. I was in Paris and felt it somewhat obligatory that I visit the big attractions – Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, and of course The Louvre. It was a warm summer day and there were lots of other tourists as well. I made my way to the Mona Lisa, as one must, and I was ushered through a crowded line past the tiny painting (it was much smaller than I expected). I stood back and looked at it from afar as others were ushered past in a never-ending, and never-stopping line. I didn’t care for the experience, and quickly left to see more of the museum. I soon found myself in a large room with the Venus de Milo. Nobody else was there. It was just us, and was such a stark contrast to the experience with the Mona Lisa. This enormously famous sculpture and I had it all to myself. I’ll never forget that. (S2_P164)

I spent the afternoon having lunch and visiting the Phillips Collection in Washington DC. I was with a wonderful young woman who I was, of course, in love with. We were saying goodbye as she was permanently moving to another city in another state. We were contemplating The Boating Party and reminiscing about all the time we had together. The day ended in both sadness and joy. (S2_P130)

I went to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when I was 13 years old. It was a really interesting trip since I really liked rock music at the time. I liked seeing all the memorabilia and facts about the different musicians. It was nice seeing all the people there to talk about all the music with … My favorite thing was making a friend who liked a lot of classic rock/metal like Black Sabbath and Metallica. (S2_P25)

Finally, the society aspect of scope refers to those experiences that involve diverse communities or that confront visitors with ideas at a global scale, such as war, systemic oppression, the rise and fall of civilisations, climate change, and other societal concerns. For example, one participant describes their visit to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC:

This museum, although I had not been before, holds a special place for me because I come from an [Airforce] family … Seeing the history of air and space of our country and to a degree my family was very meaningful for me. It was also very fun, with interesting things to look at and do all around. The thing that struck me most was a display of art done by soldiers. The beautiful paintings and incredible photos of world war era art in tunnels under France really drew me in. To contemplate the dichotomy of living in the hell of war but also in an incredibly beautiful place and making meaningful art either during or after it … I don’t know, it’s truly amazing. (S2_P47)

It was interesting to see what immigrants had to go through to get into the United States. All of the various rooms had detailed history on what happened, not all of it good. There was a lot of sickness and death. The hospital was creepy. There was a small movie theater that showed an immigration documentary with commentary from immigrants of the time. (S2_P138)

Generally speaking, memorable museum experiences comprise varying levels of each scope. Occasionally, an experience may be uniquely individual, such as in the experience of S2_P164 above; however, most participants (61%; ) selected the togetherness trigger, suggesting that other people were present and somehow contributed to the experience being memorable. Moreover, the society scope becomes relevant when the experience transcends the individuals or communities directly involved in the experience.

6. Discussion

Returning to the original research questions, we found that the content of museum meaning comprises at minimum the phenomena described by the 23 triggers identified in Study 1 (RQ-1). Moreover, the findings from Study 2 nuanced some of the original trigger definitions but did not ultimately result in the addition of any new triggers, suggesting that the current list is comprehensive (RQ-2-1). Finally, analysis of the frequencies of trigger selection in relation to demographic factors revealed several trigger correlations that have design implications for different audience types (RQ-2-2). Herein, we discuss these implications in more detail.

6.1. A typology of museum meaning

It is perhaps unsurprising that triggers such as learning, atmosphere, authenticity, and aesthetics appear most commonly in the experiences shared by participants (). Indeed, these triggers represent the ‘bread and butter’ of museum offerings: opportunities for education (learning), engaging environments and scenography (atmosphere), historical objects (authenticity), and the appreciation of beauty (aesthetics). Moreover, togetherness, which appears in 61% of experiences, emphasises the importance of museums as social and communal spaces, which can directly impact the development of meaning for visitors.

In contrast, those triggers that appeared less frequently generally relate to specific types of museums or museum experiences. For example, trauma, which only appears in 6% of the experiences, often occurs during visits to memorial museums, during which times visitors confront the darkest corners of the human condition. In another example, the VIP trigger assumes a certain level of exclusivity, in other words, cases in which participants receive special treatment or an elevated status. One would not expect this trigger to appear extremely often, otherwise the sense of exclusivity that motivates the VIP trigger would no longer exist. Spirituality, which appears in 9% of the data, refers to transcendent experiences, whether philosophical or religious in nature, and can be difficult to generalise due to how subjective and idiosyncratic an individual’s experience may be. Nevertheless, the occurrence of the trigger in almost 1 out of every 10 experiences suggests considerable relevance to the visitor experience and not merely a niche occurrence. Indeed, the data reveals that with increasing age participants were more likely to select curation and spirituality (), suggesting that museum interventions that promote moments of reflection or contemplation may appeal to some older audiences.

There were no cases in the data where a single trigger acted alone. Instead, triggers appear in groups, often reinforcing one another. In the earlier example of the participant who lost himself in the painting La Princesse de Broglie by Ingres, more than merely the aesthetics trigger, the participant explained that the shared experience with his wife (togetherness), and their fond recollection of the experience, added to the importance of the moment. This suggests that when designing with specific triggers in mind, it is necessary to consider them in relation to one another rather than merely in isolation.

Returning to the tetrachoric analysis, certain combinations of triggers are positively correlated, which can offer insights into prominent groupings. These include spirituality and introspection, trauma and responsibility, trauma and provocation, connection and responsibility, connection and gratitude, and finally, discovery and learning. Spirituality and introspection both relate to contemplative, deeply reflective moments during the museum visit. An important difference between them is that spirituality implies a transcendent quality, whereas introspection largely refers to an individual’s internal world. Nevertheless, it is perhaps not surprising that introspective activities may engage with one’s personal faith or philosophical predilections and vice versa.

The trauma trigger has a strong relationship to responsibility and provocation. Responsibility refers to consideration of moral or ethical behaviour, which is a common response during visits to memorial museums (see for example, Weisser and Koch Citation2017). Indeed, many people asked themselves how it was possible for so much death and destruction to take place, or how it is possible for individuals to engage in such heinous behaviour. Trauma and provocation also occur together in memorial museums, which can be very provocative in their curation, such as in the case of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum example discussed earlier, but other examples also appear in the data. For example, as one participant described:

I distinctly recall the experience of being in Russia’s Kunstkamera museum and seeing perhaps their most famous exhibit firsthand. A colleague of mine had hoped to visit the anthropology museum that day but it was closed for an event. Instead, we chose to see Peter the Great’s collection of ‘oddities’. In the Kunstkamera there is a large room filled with preserved fetuses, many of which had serious deformities. Peter the Great apparently collected them personally to show off to European nobility. Never have I felt so physically uncomfortable at a museum as I did there, and it was only after our visit that I learned this was the museum’s most famous exhibit. My friend was nauseous. It is hard to express the combination of discomfort and morbid curiosity the room invoked in me at the time. (S2_P64)

Finally, discovery and learning are a logical grouping insofar as free exploration of museum spaces often leads to new insights. The novelty aspect of the discovery process, which emphasises the experience of an unexpected finding, is almost always guaranteed to teach something new.

6.2. Designing for diverse audiences

In consideration of demographic factors and their influence on museum meaning, the results point to specific triggers which may have relevance for different audience types (). Beginning with the museum personas, the Recharger appears more likely to select spirituality than their other counterparts. This finding reinforces the previously established role of the Recharger as the religious or philosophical seeker (). Moreover, the Recharger selected learning, play, and proclivity less frequently than the other types, suggesting that this audience is primarily concerned with a contemplative, introspective, deeply personal experience, thereby reinforcing Falk’s (Citation2009) original conception of the persona.

For the Professional/Hobbyist, there is a greater focus on authenticity, contribution, and gratitude. Insofar as the Professional/Hobbyist comes to the museum with previous expertise or heightened interest in the museum and its collections, it is, therefore, not surprising that authenticity (appreciating an object for its tangibility and historicity) may play an important role in meaning-making for this specific audience. Moreover, contribution (participating in or contributing to an exhibit) and gratitude (feelings of humility, pride, and happiness for an experience) adhere to expected roles of the persona as this type tends to be already invested in the subject matter. For example, one participant described an experience featuring both triggers:

I performed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art with my friends and my younger brother for a very full audience in one of the American Art galleries. It wasn’t my first time performing at the museum, but it was my first time being billed 2nd under a much more well-known artist … The experience was memorable and enjoyable for me because it was such a new type of performance experience, and it was my first time inviting one of my family members to perform with me … The performance was part performance and part history lesson, so I was able to also show off my research abilities as well. Overall, it was just a really great experience. (S2_P26)

Additionally, level of education influences how museum visits are experienced. Those with a high school degree or lower tended toward moments of connection to the past, open-ended discovery, childhood visits or other formative experiences (formation), and playful interactions (play). This seems to suggest that designing for emotional or playful interactions may appeal to this audience more readily. These interactions can take many forms, such as offering visitors the opportunity to directly engage with individuals who lived through historical events (connection) or illustrating the complexities of a particular style of painting through an interactive painting game (play). In this manner, visitors can actively construct or discover knowledge, rather than passively absorb it.

Bachelor’s degree holders and trade school graduates tended to select a wider array, including aesthetics, anticipation, connection, formation, gratitude, play, proclivity, and togetherness. In consideration of possible design trajectories across such a diverse spectrum of triggers, it can be useful to consider smaller groups of triggers and how they might influence or reinforce one another. For example, returning to the tetrachoric analysis, there was a strong correlation between connection and gratitude, which appears in the bachelor/trade school subset as well. One might imagine a public call from a museum to collect their visitors’ earliest memories of the institution (formation), followed by a special honourary event for those visitors who participated to connect and share their histories (connection/gratitude/togetherness). This particular combination of triggers is certainly not applicable to all situations, but rather serves as an example of how cultural professionals might brainstorm a particular exhibit or aspect of their museum’s public programming with meaning-making in mind.

In consideration of different visitor types, whether by demographic, museum persona, or some other factor, the present work may have relevance to recent developments in smart museums and recommender systems, which increasingly embrace the notion of the visitor as a knowledge contributor. For example, Korzun et al. (Citation2017, Citation2018) describe three classes of information comprising the ‘collective intelligence’ of the smart museum, namely expert historical knowledge, sources from the semantic Web, and visitor interaction information. In the case of the latter, which the authors state may include visitors’ subjective knowledge or experience concerning an object on display, it is conceivable that information pertaining to meaning or meaning-making with that object has the potential for deeper integration into future museum interactive systems.

Our findings reiterate previous work by Falk and Dierking (Citation1995, Citation2013), who suggest that museum memories are persistent, salient, and tied to the ways in which we construct meaning. Moreover, considering museum meaning from different perspectives, such as in the case of the 23 triggers discussed herein, can deepen the museum experience for visitors. Insofar as museum professionals are able to reimagine the same cultural space from a variety of viewpoints, so too can novel design scenarios emerge as a result. Building on the recent framework of meaning by Mekler and Hornbæk (Citation2019), which outlines meaning as a quality of interaction, we follow up with an elicitation of its content within the cultural sector. Furthermore, in the following section we present the My Museum Experiences framework, which consolidates our findings for use by design practitioners.

7. My museum experiences (MyMuEx) framework

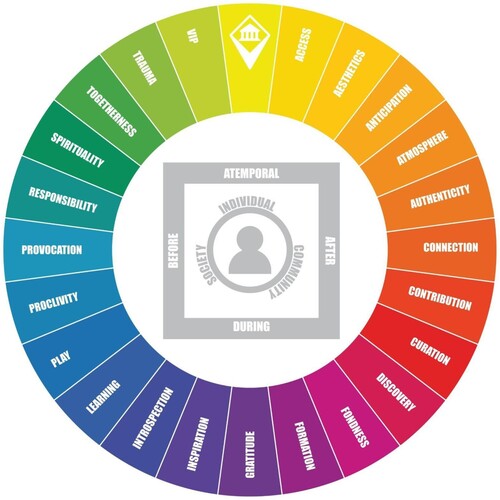

We combined the 23 museum triggers with the dimensions of temporality and scope to create the My Museum Experiences (MyMuEx) framework, visualised in . The framework outlines the varying types of meaningful experiences that occur in museum contexts, while simultaneously introducing the descriptive dimensions of temporality and scope to extend the triggers across time, space, and subjectivities.

Figure 6. My Museum Experiences (MyMuEx) framework, consisting of 23 triggers and two descriptive dimensions of temporality and scope.

The aim of the framework is to enable broader design thinking around the full spectrum of the museum experience, presenting both the content of meaning in museums as well its possible temporalities and audience scope. The results of the two studies reveal that triggers rarely, if ever, act alone, and therefore, we recommend that a similar philosophy should apply to the use of the MyMuEx. For example, in planning an exhibition, cultural professionals may choose a series of triggers and consider the ways in which these triggers can be implemented to enhance the visitor experience before, during, and after the visit. Moreover, the triggers can apply to individuals, groups, or even to society at large. In consideration of the society scope, as museums reach increasingly diverse audiences from around the world thanks to the growing popularity of their Web presence (e.g. see Gil-Fuentetaja and Economou Citation2019; Evrard and Krebs Citation2018), applying the MyMuEx framework to the online experience may help museums to enact their missions in digital spaces at an unprecedented scale.

In addition to the MyMuEx wheel, we designed a series of trigger cards (see Appendix) to support ideation activities. Each card () features one of the 23 triggers and its respective definition. We have defined two applications for the MyMuEx framework and describe them below, but we encourage designers to explore other possibilities insofar as it suits their objectives.

Ideation activity: Select 3–4 triggers from the MyMuEx wheel and their corresponding MyMuEx ideation cards. Read each definition carefully and brainstorm ways in which individual triggers may combine to reinforce or enhance the meaning of a particular museum experience. Then, consider each trigger across different temporalities and scopes (e.g. how might we make visitors feel like a VIP after the museum visit?).

Evaluation activity: After a museum visit or specific cultural experience, present visitors with the MyMuEx cards, asking them to read each trigger definition. Then ask visitors to choose the triggers they felt represented the experience they had during their visit, using the cards as an experiential vocabulary to deepen the discussion about strengths and weaknesses of the experience.

Certain demographic factors described in the discussion, such as age or museum persona, appear to have some influence on which triggers individuals are likely to select or which triggers may be most compatible. With this in mind, it may be beneficial to include these considerations into the choice of cards early on in the design process; however, we emphasise that despite the universality of the meaningful experiences described by the triggers, subjectivity remains an essential component of personal meaning. The amount of within-group complexity may vary depending on region, culture, language, or other factors, and as such our findings do not necessitate such a highly targeted implementation.

8. Limitations and future work

While we have endeavored to be as comprehensive as possible in our approach, we nevertheless identify some limitations which will be the subject of future work. First, although our results show that the 23 triggers were comprehensive, our participants’ sample were English speakers, primarily from Europe and the United States. Cultural differences in the construction of meaning may have influence on these triggers and their validity in non-English speaking contexts. Although our dataset includes museums from Central and South America, Central, East, and South Asia, as well as Africa and the Middle East, these areas have limited representation compared to Europe and the United States. As such, future work should consider different geographical, cultural, and linguistic contexts to improve the generalisability of the findings.

The results of our study draw from the lived experiences of museum visitors with the aim of establishing our framework of meaning through a user-centered process. We interviewed some visitors who discussed issues of accessibility with us, such as special accommodations (or a lack thereof) made for individuals with impaired mobility, hearing loss, and other accessibility concerns. While certainly an issue relating to the access trigger, future work may also establish additional recommendations to support museum inclusivity in the context of the current framework. Similarly, future work must also consider the framework in the context of vulnerable populations as well as implications for museums as increasingly intersectional spaces.

A final limitation relates to design for digital cultural heritage. Although seemingly comprehensive for the on-site and online museum context, future work will explore how to design these triggers in exclusively digital contexts. Indeed, as museum collections and exhibitions are increasingly digital and accessible directly from our personal devices, there is a necessity to expand this framework into design for digital spaces to evaluate its effectiveness. For example, how might designers rethink authenticity (appreciation of an object’s tangibility or historicity) in a digital space?

9. Conclusion

This research contributes to meaningful design in the cultural sector through an elicitation of the content of meaning in museums. We argue that meaningful experiences in museums can be mapped to the 23 identified triggers, which we summarise in the MyMuEx framework. Moreover, the framework also introduces the notion of temporality, which extends the triggers into pre- and post-visit contexts, as well as scope, which applies the triggers to different audience types. Scope has become especially relevant in the digital context, as museums now attract global audiences at an unprecedented rate (often in lieu of the physical visit altogether, e.g. Evrard and Krebs Citation2018). Building on prior work on meaning as a quality of interaction, we contribute to a deeper understanding of its content in museums, and how designers might inspire meaningful experiences going forward.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH) and the Human–Computer Interaction Research Group at the University of Luxembourg.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alelis, G., A. Bobrowicz, and C. S. Ang. 2013. “Exhibiting Emotion: Capturing Visitors’ Emotional Responses to Museum Artefacts.” In Design, User Experience, and Usability. User Experience in Novel Technological Environments, 429–438. Berlin: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39238-2_47

- Bardzell, S. 2010. “Feminist HCI: Taking Stock and Outlining an Agenda for Design.” Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ‘10, 1301. doi:10.1145/1753326.1753521.

- Bardzell, J., S. Bardzell, and M. Blythe. 2018. “Introduction.” In Critical Theory and Interaction Design, edited by J. Bardzell, S. Bardzell, and M. Blythe, 407–416. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Beal, D., and H. Weiss. 2003. “Methods of Ecological Momentary Assessment in Organizational Research.” Organizational Research Methods 6: 440–464. doi:10.1177/1094428103257361.

- Bedigan, K. M. 2016. “Developing Emotions: Perceptions of Emotional Responses In Museum Visitors.” Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo.204969.

- Benjamin, R. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity.

- Biran, A., Y. Poria, and G. Oren. 2011. “Sought Experiences at (Dark) Heritage Sites.” Annals of Tourism Research 38 (3): 820–841. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2010.12.001.

- Blandford, A., D. Furniss, and S. Makri. 2016. “Qualitative HCI Research: Going Behind the Scenes.” Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics 9 (1): 1–115.

- Bødker, S. 2015. “Third-Wave HCI, 10 Years Later – Participation and Sharing.” Interactions 22 (5): 24–31. doi:10.1145/2804405.

- Boehner, K., P. Sengers, and S. Warner. 2008. “Interfaces with the Ineffable.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI). doi:10.1145/1453152.1453155.

- Caine, K. 2016. “Local Standards for Sample Size at CHI.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 981–992. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858498.

- Ciolfi, L., and D. Petrelli. 2015. “Walking and Designing with Cultural Heritage Volunteers.” Interactions 23 (1): 46–51.

- Cockburn, C. 1992. “The Circuit of Technology: Gender, Identity and Power.” In Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces, edited by R. Silverstone and E. Hirsch, 33–42. London: Routledge.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

- Demir, E., P. M. A. Desmet, and P. Hekkert. 2009. “Appraisal Patterns of Emotions in Human-Product Interaction.” International Journal of Design 3 (2): 41–51.

- Dourish, P. 2018. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Althusser’s “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.”.” In Critical Theory and Interaction Design, edited by J. Bardzell, S. Bardzell, and M. Blythe, 407–416. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Evrard, Y., and A. Krebs. 2018. “The Authenticity of the Museum Experience in the Digital Age: The Case of the Louvre.” Journal of Cultural Economics 42 (3): 353–363. doi:10.1007/s10824-017-9309-x.

- Falk, J. H. 2009. Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 1995. “Recalling the Museum Experience.” Journal of Museum Education 20 (2): 10–13. doi:10.1080/10598650.1995.11510292.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2000. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Farrell, B., and M. Medvedeva. 2010. Demographic Change and the Future of Museums. American Association of Museums. https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Demographic-Change-and-the-Future-of-Museums.pdf.

- Gil-Fuentetaja, I., and M. Economou. 2019. “Communicating Museum Collections Information Online: Analysis of the Philosophy of Communication Extending the Constructivist Approach.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 12 (1): 3. doi:10.1145/3283253.

- Gökçiǧdem, E. M. (ed.). 2016. Fostering Empathy Through Museums. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1294408.

- Grimaldi, S., S. Fokkinga, and I. Ocnarescu. 2013, October 1. “Narratives in Design: A Study of the Types, Applications and Functions of Narratives in Design Practice.” Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, DPPI 2013. doi:10.1145/2513506.2513528.

- Grinter, B. 2018. “Representing Others: HCI and Postcolonialism.” In Critical Theory and Interaction Design, edited by J. Bardzell, S. Bardzell, and M. Blythe, 723–736. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Hassenzahl, M., M. Burmester, and F. Koller. 2003. “AttrakDiff: Ein Fragebogen zur Messung wahrgenommener hedonischer und pragmatischer Qualität.” In Mensch & Computer 2003. Vol. 57, edited by G. Szwillus and J. Ziegler, 187–196. Vieweg+Teubner Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-80058-9_19.

- Hassenzahl, M., K. Eckoldt, S. Diefenbach, M. Laschke, E. Lenz, and J. Kim. 2013. “Designing Moments of Meaning and Pleasure.” International Journal of Design 7 (3): 11.

- Hassenzahl, M., and N. Tractinsky. 2006. “User Experience – A Research Agenda.” Behaviour & Information Technology 25 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1080/01449290500330331.

- Hennink, M., and B. N. Kaiser. 2022. “Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests.” Social Science & Medicine 292: 114523. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Henry, C. 2000. “How Visitors Relate to Museum Experiences: An Analysis of Positive and Negative Reactions.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 34 (2): 99. doi:10.2307/3333580.

- Huta, V., and A. S. Waterman. 2014. “Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions.” Journal of Happiness Studies 15 (6): 1425–1456. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0.

- Jordan, P. W. 2002. Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors. London: CRC Press.

- Karapanos, E., J. Zimmerman, J. Forlizzi, and J.-B. Martens. 2009. “User Experience Over Time: An Initial Framework.” Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI 09, 729. doi:10.1145/1518701.1518814.

- Kenderdine, S., L. K. Y. Chan, and J. Shaw. 2014. “Pure Land: Futures for Embodied Museography.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 7 (2): 1–15. doi:10.1145/2614567.

- Kidd, J. 2019. “With New Eyes I See: Embodiment, Empathy and Silence in Digital Heritage Interpretation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1341946.

- Kirillova, K., X. Lehto, and L. Cai. 2017. “What Triggers Transformative Tourism Experiences?” Tourism Recreation Research 42 (4): 498–511. doi:10.1080/02508281.2017.1342349.

- Korzun, D., A. Varfolomeyev, S. Yalovitsyna, and V. Volokhova. 2017. “Semantic Infrastructure of a Smart Museum: Toward Making Cultural Heritage Knowledge Usable and Creatable by Visitors and Professionals.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 21 (2): 345–354. doi:10.1007/s00779-016-0996-7.

- Korzun, D., S. Yalovitsyna, and V. Volokhova. 2018. “Smart Services as Cultural and Historical Heritage Information Assistance for Museum Visitors and Personnel.” Baltic Journal of Modern Computing 6: 4. doi:10.22364/bjmc.2018.6.4.07.

- Kostoska, G., D. Fezzi, B. Valeri, M. Baez, F. Casati, S. Caliari, and S. Tarter. 2013. “Collecting Memories of the Museum Experience.” CHI ‘13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems on – CHI EA ‘13, 247. doi:10.1145/2468356.2468401.