ABSTRACT

The short version of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS-18) uses nine factors to assess video game satisfaction. As video games play an important role for children and adolescents, the aim of this study was to translate and adapt the adult English version to an adolescent German version (GUESS-GA-18) and validate the new scale. Translation and adaptation were done in a participatory process with Austrian adolescents in two consecutive focus group sessions. In the validation study with 401 adolescents, fit indices demonstrated good model fit and a confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the nine-factor structure of the new scale. Internal consistency is acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .791). Concurrent validity shows that the GUESS-GA-18 measures whether children like the game. The German GUESS-GA-18 for adolescents is a short and comprehensive tool for iterative development of games and studies testing player experience with German-speaking adolescents.

Videogames, computer games and mobile games have become increasingly popular with adolescents in the last decades in both the U.S.A. and Europe (Bottel and Kirschner Citation2019; Tsitsika et al. Citation2014). In Germany, there were more than 34 million computer- and videogame players in 2020 and trends show that this number will rise rather than fall. Users become increasingly younger. Accelerated by the increase of mobile-based games (Marchand and Hennig-Thurau Citation2013), a large proportion of young adolescents now play games in German-speaking countries (Mittmann et al. Citation2021). To ensure good gaming experience, it is important to be able to measure acceptability, feasibility and usability of games – in game user research also called the player experience. Due to the wide range, anonymity and the possibility of capturing the experiences of many people at the same time in a cost-saving manner (Gangrade Citation1982), questionnaires are widely used as a valid and reliable tool to evaluate these qualities (e.g. Brockmyer et al. Citation2009; Inan Nur, Santoso, and Hadi Putra Citation2021), and a variety of questionnaires for testing player experience exist. Yet, to our knowledge, no comprehensive questionnaire to test player experience exists specifically for adolescents; and there is no validated German questionnaire covering all relevant factors of player experience.

Considering the rising trend of gaming in German-speaking countries and the increasing importance of games for adolescents, this study aimed to translate, adapt and validate a questionnaire for assessing player experience of German-speaking adolescents. For this, we chose the English version of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS-18; Keebler et al. Citation2020), for two main reasons: First, the ‘best practice’-development of its long version, the GUESS, which led to a comprehensive tool that covers all relevant factors of player experience; and second, its shortness, which makes it ideal for use with adolescents.

1.1. Related work and the GUESS-18

Commonly used questionnaires to assess player experience of digital games (cited ≥1000 times) include the Immersion Questionnaire (Jennett et al. Citation2008), the Game Engagement Questionnaire (Brockmyer et al. Citation2009), the Gameplay Experience Questionnaire (Ermi Citation2005) and the Player Experience of Need Satisfaction Scale (Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006). An example for a German questionnaire is the Game Experience Questionnaire (Engl and Nacke Citation2013). The authors of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS; Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro Citation2016) detected several limitations in the existing scales such as that they are only suitable for certain games or genres, important gaming aspects were not considered, items were too difficult to understand/interpret and a lack of psychometric validation. Consequently, they developed a new questionnaire following the ‘best practice’ for scale development and validation: After generating an item pool consisting of the content of 13 existing questionnaires, 15 lists of game heuristics and three user satisfaction questionnaires, an expert panel reviewed the items. Subsequently, a pilot study with gamers took place to make sure that the items were easy to understand. Finally, both an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were conducted to validate the scale (Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro Citation2016).

The GUESS covers nine factors of player experience: Usability/Playability, Narratives, Play Engrossment, Enjoyment, Creative Freedom, Audio Aesthetics, Personal Gratification, Social Connectivity, and Visual Aesthetics. The questionnaire consists of 55 items answered on a 7-point Likert scale. Due to the rather long format of the questionnaire, Keebler et al. (Citation2020) developed and validated a short version of the GUESS, the GUESS-18. This short version still covers all nine factors, but with only 18 items (2 items per factor). Answers range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) on a 7-point Likert scale with a maximum value of 63 and a minimum value of 9 for overall score of video game satisfaction. In a first study about psychometric features, the authors found excellent fit and construct validity for the nine factors. While Keebler et al. (Citation2020) argue that a shorter version will mostly benefit iterative game development, we see another advantage in using this shorter version: Gathering children’s and adolescents’ opinions. As younger people lose motivation when the questionnaire is too long (Borgers, De Leeuw, and Hox Citation2000), a compressed format can help in keeping them focused and not lose concentration. While the original version of the GUESS has been adapted to Turkish by Berkman, Bostan, and Şenyer (Citation2022), to our knowledge no German version exists. gives an overview of some of the existing questionnaires for player experience.

Table 1. Existing questionnaires for player experience.

In summary, the goal of the current study was to create and validate a German version of the GUESS-18 with and for adolescents using a participatory approach (GUESS-German-Adolescents-18; GUESS-GA-18). Therefore, for this paper, we first translated the English version of the GUESS-18 to German and adapted it for adolescent users by using rigorous co-design methods. Then we validated the translated and adapted questionnaire in a sample of German-speaking adolescents.

2. Methods

2.1. Translation and adaptation

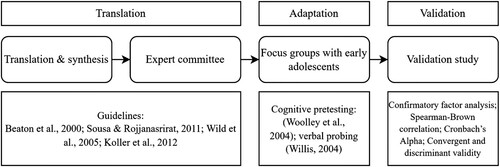

An overview of the methods used in this study can be found in . The goal of the first part of the study was to translate the original English version of the GUESS-18 to German and then adapt the adult version to be suitable for adolescents, following standard procedure for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires (Beaton et al. Citation2000; Sousa and Rojjanasrirat Citation2011; Wild et al. Citation2005) and complying with recommendations for designing or adapting questionnaires for children (e.g. Aydın et al. Citation2016; Bell Citation2007). Consent to translate and adapt the GUESS-18 was obtained from the authors of the original questionnaire before the process was started. The process consisted of four steps: Forward translation by two translators, synthesis of the forward translation, expert committee and focus group sessions with early adolescents. For the full process, including changes made at different steps, see .

Table 2. Process of the translation and adaptation of the items of the GUESS-18 for the use with German-speaking adolescents.

Though backward translation (i.e. translating the German translation back to English and comparing the original version with the back-translated one for similarity) by an independent third translator who does not know the original questionnaire (as a third step before discussing the version with an expert committee) is recommended in some guidelines for the translation of questionnaires (e.g. Beaton et al. Citation2000), there has also been some discussion about the shortcomings of such. The main argument against backward translation is that a literal translation sticking precisely to the wording of the original items might miss necessary context and comprehensibility components and therefore lead to a reduction in quality rather than an improvement (Behr Citation2017; Colina et al. Citation2017). Considering that we not only translated the questionnaire but also adapted it to adolescents’ needs, we decided against backward translation as we expected that some expressions had to be adapted to a more child-friendly language, thus rendering a step that tests for literal translation unnecessary.

2.1.1. Step 1 – forward translation by two translators

In this step, two independent translators created two German versions of the questionnaire. Two native German speakers (GM and IK) who are both fluent in English translated the original GUESS-18 items to German individually and independently.

2.1.2. Step 2 – synthesis with two translators and one moderator

In this step, the two versions of the German questionnaires were synthesised into one version. In a joint meeting, the two original translators and an additional moderator (VZ) compared the two German versions and synthesised it to one version. We followed the coordination process of Koller et al. (Citation2012). This approach considers the original version, comprehensibility, culture, grammar and terminology and emphasises on reaching consensus instead of compromising.

2.1.3. Step 3 – expert committee

In this step, the synthesised version was discussed with experts of the relevant fields and changes were made considering their expert knowledge. The expert committee comprised the two original translators, the moderator, a software developer and gaming expert and a schoolteacher for German language in secondary school. Thus, the questionnaire was further discussed with a focus on content (gaming expert) and German language (teacher).

2.1.4. Step 4 – focus groups with early adolescents

Since the cognitive abilities of children and adolescents are still developing, it is important to adjust the difficulty and length of questionnaires for young people. When answering a question, respondents experience four phases: The question must be understood, relevant facts must be recalled, a judgment must be made and finally, an answer must be selected (Tourangeau Citation1984). The Optimising-Strategy is applied if the respondent undergoes every phase properly, whereas the alternative Satisficing-Strategy is used if at least one phase is either omitted or poorly performed. Whether the Satisficing-Strategy instead of the Optimising-Strategy is applied depends on the difficulty of the question, the respondent’s motivation and cognitive abilities (Jon Citation1991). Even though we did not develop a new scale but adapted an existing one for adolescent use, we kept the various guidelines and insights for designing questionnaires for children and adolescents in mind during the focus groups for adapting the GUESS-18 together with early adolescents. These can be found in .

Table 3. Guidelines for questionnaires for young people.

Cognitive pretesting with the target group is recommended, which is an optimal method when conducting a participatory research approach. The term ‘Participatory Research’ describes a non-hierarchical approach to research (Abma et al. Citation2019), in which knowledge is produced collectively by and with the people whose lives are the focus of the research (Involve Citation2019). Through flexible, reflexive and bottom-up strategies, the co-researchers are encouraged to become active and make decisions at different levels of the research process (Unger Citation2013). This not only improves the quality of research and increases efficiency (Jagosh et al. Citation2012), but also empowers the people involved (Cahill Citation2007). In recent years, children and younger adolescents have also been actively involved in participatory research (Bevan Jones et al. Citation2020; Montreuil et al. Citation2021) and distance-based methods such as video and telephone-based methods, text-based focus groups or digital diaries were successfully used during the Covid-19 pandemic (Hall, Gaved, and Sargent Citation2021).

In line with participatory research and public involvement, in step 4, the German version of the questionnaire was presented to a group of early adolescents in two subsequent online focus group sessions. These sessions were approved by the Karl Landsteiner Commission for Scientific Integrity and Ethics (EK Nr: 1025/2020). Participants were recruited via existing networks of the research group. All participating early adolescents and a legal guardian signed informed consent. While the focus was on translation in the prior steps (1–3), in step 4 the focus was on the involvement of early adolescents in the adaptation of the questionnaire items. This was intentional to be able to let early adolescents themselves decide which words/expressions needed rephrasing to be comprehensible for them. Both online sessions were led by two trained focus group leaders and lasted 1.5 h. The first session included six early adolescents (4 male, 2 female; agemean = 12). The goals/objectives of the focus group session were (1) the adaptation of the items and answer format and (2) to ensure the developmental validity by pretesting the questionnaire. This was achieved by combining the four steps of cognitive pretesting (1. Read the question, 2. Paraphrase the question, 3. Pick the best answer, 4. Explain the answer; Woolley, Bowen, and Bowen Citation2004); verbal probing (follow-up questions to fully understand participants responses, e.g. ‘Wie kann man denn mit anderen Kindern gemeinsam spielen? An was denkt ihr da?/How can you play with other kids? What are you thinking about?’; Willis Citation2004) as well as adaptive questions (e.g. ‘Wie würdet ihr die Frage formulieren? Was können wir ändern?/How would you phrase that question? What could we change?’).

For this purpose, one person at a time was asked to read the question aloud and to reproduce/paraphrase the meaning of the question in their own words. In the next step, the other early adolescents were also included and asked how they would interpret the item. For terms that might cause comprehension difficulties (e.g. ‘Interaktionen’), the adolescents were asked about its meaning and – if necessary – alternative child-friendly words. If there were major comprehension problems with items, an age-appropriate explanation was prepared, which could be referred to if necessary. After discussing and sometimes adapting the item, in a final round all early adolescents were asked again if anything needed to be changed to improve understandability. If early adolescents made different suggestions for adaptations, votings or surveys were used to find an agreement or make a final decision.

After the discussion of the first item, different answer formats were presented and consulted about their fit. We offered participating early adolescents different options for scales (4-point, 5-point). We also enquired participants’ response behaviour if the item asked something that might not apply to all games (e.g. what would they answer to the question ‘I enjoy the sound effects in the game’ if the game has no music/sound).

The new version of the items and the answer format were immediately presented to the participants to review their decision. In addition to that, audio of both focus group sessions were transcribed, analysed and reviewed by the two session leaders. Both reviewers wrote individual notes, including observations and comments on participants’ responses to each item. They also concluded summary statements for each item, including observations and issues. Subsequently, they met and presented their findings to each other. These findings and reflections also influenced the discussion of the second focus group.

The second focus group session took place one week later and was led by the same focus group leaders as the first session. Four participants of the first session participated in the second one as well as three new participants (5 male, 2 female; agemean = 11.83). Including both early adolescents from the first session and naïve early adolescents was in line with participatory research and ensured that the new version of the questionnaire spoke to both the group of adolescents who adapted it as well as ‘new’ adolescents. Early adolescents were presented with the updated version of the questionnaire following the suggestions from the first session. They had the opportunity to discuss and vote on the design of the questionnaire (font, colour, emojis, etc.), fill out the questionnaire and discuss if they were content with the final version.

As a result of these focus groups, changes were made to nine out of the 18 items (see ). Six of these changes were about replacing one word; two times, part of a sentence was changed; and once, the whole item was replaced with a more understandable and clearer item from the particular factor of the item pool of the GUESS-55 (Enjoyment2, see ). Five out of six participating early adolescents preferred the 5-point Likert scale (‘stimme gar nicht zu’, ‘stimme eher nicht zu’, ‘teils/teils’, ‘stimme eher zu’, ‘stimme voll zu’/‘don’t agree at all’, ‘don’t really agree’, ‘undecided’, ‘mostly agree’, ‘totally agree’). Participants’ random response behaviour to items that do not apply to the game (e.g. no sound), which ranged from choosing the lowest to the middle to the highest option on the scale, led to the addition of a fallback option to the scale (‘gibt es in dem Spiel nicht/ not in the game’). All participants endorsed the final version. For better comparability, also shows the English translation of the final German version.

2.2. Validation study

2.2.1. Participants and recruitment

For our validation study, we aimed for 300 participants between 10 and 18 following Clark and Watson (Citation2016)’s suggestion for validation sample size. Ethics approval was granted by the Karl Landsteiner Commission for Scientific Integrity and Ethics (EK Nr: 1103/2021). The link to the online questionnaire was distributed online via social media, with a special (but not exclusive) focus on groups with a gaming background, a collaboration with a YouTube influencer, as well as shared with the network established during the research project (e.g. parent groups and school classes). Additionally, the GUESS-GA-18 was filled out by five classes during a series of workshops of the research group where participants played a serious game.

2.2.2. Procedure

Data was collected via an online questionnaire. Participants of the workshops were asked to fill out the questionnaire rating the serious game LINA (Mittmann et al. Citation2022) that they had played during the workshops. All other (online) participants were first asked for their own and their parents’ consent, then they were asked which game they had played most recently. Participants could either choose one out of seven popular games played by adolescents (Minecraft, Fortnite, Brawl Stars, Grant Theft Auto (GTA), Candy Crush, The Sims, FIFA, which were identified through Tenzer (Citation2022) and through conversations with adolescents) or type in a different game. They were then asked to think of their chosen game when filling out the GUESS-GA-18. The items were presented in a random order. A single question (‘Wie gut gefällt dir das Spiel?/How much did you like the game?’) was used to assess concurrent validity. Subsequently, sociodemographic data was assessed, i.e. age, gender and German language level. If interested, participants could sign up for a voucher raffle at the end.

2.2.3. Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 and SPSS AMOS. The significance threshold was set at p = .05. Demographic information was described using range, means, standard deviations and for categorial data counts and percentages. Q-Q plots, skewness and kurtosis were used to test for normality. Maximum Likelihood (ML) Estimator was used as an estimation method in the factor analysis. Full information ML (FIML) was used as an estimation method for missing data.

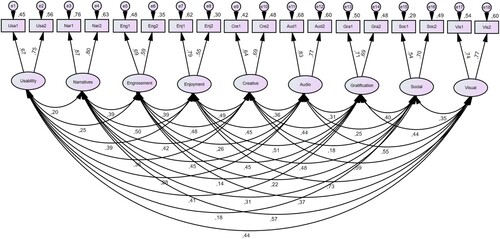

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to test if the suggested nine-factor model from the original GUESS-55 and GUESS-18 matched the GUESS-GA-18. Each factor consists of two items (Usability/Playability1, Usability/Playability2, Narratives1, Narratives2, Play Engrossment1, Play Engrossment2, Enjoyment1, Enjoyment2, Creative Freedom1, Creative Freedom2, Audio Aesthetics1, Audio Aesthetics2, Personal Gratification1, Personal Gratification2, Social Connectivity1, Social Connectivity2, Visual Aesthetics1, Visual Aesthetics2). We used chi-square with associated degrees of freedom, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Bollen’s Δ2 to evaluate the model. To further enhance construct validity, three alternative models, suggested by Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro (Citation2016), were tested: eight-factor (Audio and Visual Aesthetics combined as one factor), seven-factor (Narratives and Creative Freedom additionally combined as one factor), and one-factor model. Factor intercorrelation was allowed for all the models.

Spearman-Rho between the mean score of the GUESS-GA-18 and the single question (‘Wie gut gefällt dir das Spiel?/How much did you like the game?’) was used to calculate concurrent validity. To assess the reliability of the overall scale, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated. Special attention was paid to whether Cronbach’s Alpha increased with the exclusion of the recoded coded item ‘Ich bin gelangweilt, während ich das Spiel spiele/ I am bored while playing the game’. Spearman-Brown coefficient was used to assess the reliability of the subscales, as it is better suited for two-item scales than Cronbach’s alpha (Eisinga, Te Grotenhuis, and Pelzer Citation2013). Factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations were used to test convergent and discriminant validity of the nine-factor model.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Thirteen cases were excluded from the analysis due to invalid answer patterns (always the lowest, middle or highest score), six cases were excluded due to too little playtime of the rated game (less than 30 min and less than once a week and for less than a month) and one case was excluded due to missing German language skills.

The total remaining sample consisted of N = 401 adolescents (30.2% female; 64.3% male; 4.7% don’t want to say; 0.7% other) between 10 and 18 years (agemean = 14.58; SD = 2.83). For descriptive demographics, see .

Table 4. Demographics of the sample for the validation study.

3.2. Descriptive analyses of the GUESS-GA-18

Fifty-one different games were rated by the participants (see ). The response minimum of every item of the questionnaire was 1 and the maximum 5, which means that the whole spectrum was used. Means vary between 3.03 and 4.54 (see ), which indicates that the games were rated rather positively. Most items intercorrelated. The Intercorrelation Matrix can be found in the Supplementary Material. The mean time for filling out the GUESS-GA-18 (excluding all other parts of the online questionnaire) was 104 s (M = 104.13; SD = 50.34; seven outliers were excluded due to too high or low z-scores (> 2.68 or < -2.68)).

Table 5. Distribution of games that were chosen by the participants of the validation study.

Table 6. Means and standard deviations of the rating for all items of the GUESS-GA-18.

3.3. Confirmatory factor analysis

3.3.1. Normal distribution and missing data

Q-Q plots revealed that not all items seemed normally distributed, yet skewness was only moderate as skewness and kurtosis of all items were under |2| and |7| respectively (Curran, West, and Finch Citation1996). FIML was used as an estimation method for missing data. The fallback option ‘gibt es in dem Spiel nicht/not in the game’ was treated as missing data. In total, 4.36% of the items were missing, varying from 0.2% to 19.5% between the items. Little’s MCAR test revealed that the data was not completely missing at random (χ2 = 960.342, df = 710, p < .001), yet this is arguably not a problem for the current study. As our fallback option was treated as missing data, it makes sense that missing data was not random: Some games may have no sound or no storyline, but all games can be rated for their enjoyment. In line with that argument, the item with the most missing data was ‘Ich mag die Geschichte des Spiels/I like the story of the game’ and in fact only one of the proposed games in our online questionnaire is what could be called storyline-driven (GTA).

3.3.2. Evaluation of the nine-factor model

The path diagram of the factors can be found in . To evaluate the model fit, several fit indices are available. Besides reporting chi-square and the degrees of freedom, most researchers specify two additional fit indices (McDonald and Ho Citation2002). There is no universally accepted number of fit indices, but it is recommended to report at least chi-square with the associated significance value and degrees of freedom, an incremental fit value (e.g. Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI) or Bollen's Δ2), and a residual-based measure (e.g. RMSEA or standardised root mean squared error (SMRM); Jackson, Gillaspy, and Purc-Stephenson Citation2009). Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro (Citation2016) used chi-square including degrees of freedom, RMSEA, SRMR and Hoelter’s critical N (CN) for model evaluation of the GUESS-55, whereas the short version of the GUESS questionnaire used TLI, CFI and RMSEA in addition to chi-square and degrees of freedom. In this study, chi-square with associated degrees of freedom, RMSEA and Bollen's Δ2 were used to evaluate the model. The residual-based measure RMSEA was chosen because of two reasons: First, it is currently the most common measure for model evaluation and is used in almost all CFA-studies (Kenny Citation2015) and second, it allows a better comparability with the two GUESS studies (Keebler et al. Citation2020; Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro Citation2016). For the incremental fit value we used Bollen’s Δ2, as the other commonly used and recommended measures TLI and CFI should not be calculated if the RMSEA value is less than 0.158 (Kenny Citation2015), which was the case for our data. shows the values resulting from the factor analysis, the cut-off-values, and for comparability, the fit values from the other two GUESS studies. The RMSEA value of .041 and Bollen’s Δ2 of .959 suggest a good model fit. Chi-square also shows a significant result (p < .001) and a ratio to degrees of freedom of ≤2, which is equally indicative of the model's acceptability. Thus, the nine-factor model represents an acceptable model for the GUESS-GA-18. It also has comparable indices with the GUESS-18 and the GUESS-55 (see ). For better comparability, additionally to our indices, TLI, CFI and Hoelters’ CN are reported in .

Table 7. Model fit assessment with cut-offs of the GUESS-GA-18, The GUESS-18 and GUESS-55.

3.3.3. Model comparison

In order to find out whether the nine-factor model is the GUESS-GA-18 model that best approximates reality, it was compared with the one-factor, seven-factor and eight-factor models. For this purpose, in addition to the fit indices described above, the expected cross validation index (ECVI) was considered for model comparison. The smaller the value, the better the model fit (Schreiber et al. Citation2006). Chi-square, the RMSEA value and Bollen's Δ2 are also used for comparison. The same criteria/cut-off values as in apply to these indices. The model comparison shows that the assumed nine-factor model shows better results for all values. This means that among the four models tested, the nine-factor model is best at inferring the latent factors from the observed manifest variables (see ).

Table 8. Model comparison of different GUESS versions.

3.4. Internal consistency

Overall internal consistency showed an acceptable Cronbach’s Alpha α = .791 for the GUESS-GA-18 (Mallery Citation2003). Despite the negative wording, Cronbach’s Alpha does not change considerably (α = .789) when omitting the item ‘Ich bin gelangweilt, während ich das Spiel spiele/I am bored while playing the game’. From this we can conclude that the participants had no problems with interpreting this item. Omitting any other item did not result in an increase of Cronbach’s Alpha. Spearman-Brown-coefficient ranged between poor (Play Engrossment, Enjoyment, Social Connectivity) to good (Narratives) reliability for the subscales (see ).

Table 9. Internal consistency of the subscales of the GUESS-GA-18.

3.5. Concurrent validity

Results revealed a significant correlation between the overall score of the GUESS-GA-18 (moderate correlation with r = .530, p < .001) (Dancey and Reidy Citation2007) as well as between all subscales and the single item ‘How did you like the game?’, which means that the overall GUESS-GA-18 is able to moderately identify if people like the game (see ). Yet, most correlations of the item with the subscales are only weak to moderate.

Table 10. Correlations between the GUESS-GA-18 and the single question ‘How much did you like the game?’

3.6. Convergent and discriminant validity of the nine-factor model

We used AVE and standardised factor loadings to examine convergent validity. If AVE is above 0.5 and factor loadings are above 0.5, convergent validity can be concluded (Cheung and Wang Citation2017; Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2011). AVE for the GUESS-GA-18 is 0.513 and all factor loadings of the GUESS-GA-18 are above 0.5, with 15 out of 18 factors loadings above .6 (see ). We tested discriminant validity with the HTMT ratio of correlations. To assess discriminant validity, HTMT values are compared to an absolute threshold, which can be either 0.85 or 0.9 (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2015). If HTMT values are below this threshold, discriminant validity can be concluded. Results are shown in . All our HTMT values are below 0.85.

Table 11. HTMT values of the subscales of the GUESS-GA-18.

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to translate the GUESS-18 to German and adapt it for use with adolescents by applying a participatory research approach. We further analysed psychometric properties and tested the factor structure in a sample of 401 German-speaking adolescents between 10 and 18. In accordance with findings from Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro (Citation2016) and Keebler et al. (Citation2020), our results support the nine-factor structure in the GUESS-GA-18.

All of our model fit indices (chi-square with associated degrees of freedom, RMSEA and Bollen's Δ2) suggest a good model fit and comparison with three other model structures revealed that the nine-factor-model has in fact the best model fit.

Correlations between items and even factors were to be expected as the questionnaire sums up the user satisfaction of various parts of a game. As we asked participants to rate a game they play a lot, it is highly likely that participants liked the game, consequently rating most of the items highly. For example, it makes sense that the factor Enjoyment is high when other factors are also high. In line with that, our results show that the serious game that participants were asked to play during a school workshop was rated lower than the games that they could choose themselves.

Our reliability results show an acceptable Cronbach’s Alpha for the overall scale, but also that some factors have poor internal consistency (Spearman-Brown-coefficient). This might be influenced by the fact that our factors consisted of only two items each (Eisinga, Te Grotenhuis, and Pelzer Citation2013). As the aim of the shortened version of the questionnaire is to be a tool to be used with adolescents, too many items might make adolescents lose motivation to fill out the questionnaire. It makes sense to have a minimum of items to ensure that adolescents undergo the Optimising – rather than the Satisficing-Strategy (see Methods/Focus groups with early adolescents) and thus ensure ecological validity.

Our data was not missing at random due to our fallback option. For example, missing data could be found for items concerning the narrative (factor Narratives) of the game. As most of the rated games were not narrative-driven, it makes sense that this factor had missing data. Narratives1 was changed during the adaptation process from ‘I enjoy the fantasy or story provided by the game’ to ‘I like the story of the game’, thus omitting the word ‘fantasy’. Arguably, ‘fantasy’ in the English language covers more than just story. For example, in FIFA, you have the fantasy of being a football player even though there is no continuous story line. There are three reasons for still omitting that word. First, it is not easily translated into German and the matter was thoroughly discussed during focus groups with early adolescents, which made clear that they do not acknowledge the difference between the two words. Second, the aspect of ‘fantasy’ and immersion is additionally partly covered by the factor Engrossment. And third, our data shows that GTA was not the only game getting ratings for Narratives, so adolescents still feel the ‘fantasy’ of the game.

Some items were changed in the course of adapting the questionnaire with adolescents and notably, one item was replaced with a different item of that factor from the original GUESS. Hence, the GUESS-GA-18 is not equivalent to the GUESS-18 anymore. Furthermore, the change of the 7-point answer format to a 5-point format might have decreased sensitivity of the measurement. Yet, literature backs the results of our participatory research approach in having less options for young people (Bell Citation2007) and rigorous validation shows the acceptable psychometric qualities of the new version of the questionnaire.

The increase in popularity of digital games has also led to a growing interest from scientists in that topic: Not only are researchers interested in gaming behaviour and possible effects of gaming (Blumberg and Fisch Citation2013), games are also increasingly used as a means for teaching various educational goals. The definition of so-called serious games is a game that surpasses mere entertainment purposes (Susi, Johannesson, and Backlund Citation2007). The main advantage of serious games is that they engage players with educational topics in a fun and entertaining way, thus motivating the player to engage and learn (Hamari, Koivisto, and Sarsa Citation2014; Subhash and Cudney Citation2018). Existing serious games often lack rigorous evaluation (Ke Citation2011). The main part of evaluating a serious game is testing the effectiveness of the game in teaching the intended educational content. Yet, as serious games rely on the players’ motivation to engage with the educational content, player experience is also a vital outcome when evaluating serious games (De Lima, de Lima Salgado, and Freire Citation2015). One game in our validation study was a serious game, and our results show that the questionnaire is a good tool for both general game user research and specifically for evaluating serious games.

4.1. Strengths, limitations and future work

The major strength of this study lies in the rigorous, theory-based and participatory approach and the inclusion of the target group in the adaptation of the questionnaire. Yet, the sample for the adaptation of the questionnaire consisted only of a limited number of early adolescents. Early adolescence is the bridge between childhood and adolescence. We argue that the questionnaire is also suitable for all adolescents as they will have no problems understanding the items.

For the validation study, we transparently report methods and results. The validation study included the whole age range of adolescence, and the sample size was even higher than recommended and therefore sufficient for our analysis. Yet, we faced considerable challenges recruiting 300 adolescents. First, this was due to the Covid-19 pandemic when schools were no option for recruitment due to ongoing lockdowns and different priorities of school personnel. Consequently, our strategies relied heavily on online recruitment, which led to two limitations: First, the majority of our sample was male. This was due to the fact that our recruitment strategies targeted mainly the gaming community (Facebook groups of the relevant games, YouTube Channels for gamers) and suggests that male players still dominate these gaming groups, even though we tried to communicate that we did not only search for gamers who played video games and computer games but also smartphone games (which have a less strong sex divide; Leonhardt and Overå Citation2021; Rodriguez-Barcenilla and Ortega-Mohedano Citation2022), as well as actively posted in groups that targeted female players. Second, 35% of our sample was 18 years old. This might have been due to the fact that social media groups on Facebook/YouTube attract older adolescents, probably because younger adolescents are not allowed to use social media apps in general and ‘newer’ (and hence more attractive to younger adolescents) social media apps such as TikTok or Instagram do not have the option to share a link for a questionnaire and could therefore not be used for recruitment. Studies with a video game context should have a clear strategy on recruitment, especially when targeting children and adolescents and a strategy how to recruit female participants. In line with that, we found that there were sex differences for the different games of our study, with more male adolescents playing games such as Fortnite and GTA, and more females playing The Sims and Candy Crush. Minecraft was the only one of our main games that was played almost equally by male and female participants.

In terms of statistical analysis, we only used a single question instead of a related questionnaire to assess construct validity, which means that this is only an initial value and should be interpreted with care. Even though the single question ‘How did you like the game?’ has a significant correlation with all subscales, correlations are weak for most of them, which underlines the argument that player experience is a multi-faceted construct that requires more than just one question to measure (Federoff Citation2002). Our question mostly related to the Enjoyment factor of the questionnaire. A recent study adapting the original GUESS to Turkish (Berkman, Bostan, and Şenyer Citation2022) found that, rather than a nine-factor structure, their questionnaire had a 10-factor structure, where Usability/Playability are divided into two different factors. We did not test for a 10-factor structure as our data collection for the adaptation and translation started before their article was published. As we believe that both items of the short version of the GUESS would belong in the Usability factor (see Berkman, Bostan, and Şenyer Citation2022 for definition), our questionnaire could not be tested for the 10-factor structure. Future research could test if the short version of the GUESS is missing the factor Playability entirely. Moreover, it might be advantageous to pre-test the questionnaire with older adolescents; test re-test reliability; examine sex differences further (e.g. sex differences for each game); and test validity with other measures.

The translated English items could be used to validate the English version of the GUESS-18 for adolescents. It might also be advantageous to have an adult German version of the GUESS, as games are not only played by adolescents. For this, translated items of the translation process before adapting them with adolescents might be used (see ).

4.2. Practical implications

All items for the GUESS-GA-18 can be found in the last column of . Ideally, they should be presented in random order. Our results of the focus groups show that it is advantageous to add a fallback option to the questionnaire for items that cover factors irrelevant to the specific game. We termed this fallback option ‘gibt es in dem Spiel nicht/ not in the game’. In line with Keebler et al. (Citation2020), item 8 needs to be reverse coded. For scoring, ratings of each subscale are averaged for a subscale score. Summing up subscales will create a total player experience score with a minimum of 9 and a maximum of 45. On average, it takes less than 2 min for adolescents to fill out the GUESS-GA-18.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the GUESS-GA-18 proves to be a satisfactory, valid and acceptable tool to test player experience in adolescents. It is short and easy-to-use, and our study shows support for good psychometric properties and original factor structure. Thus, the GUESS-GA-18 provides a new tool for testing general player experience with a target group of German-speaking adolescents. It might be used for both game design and evaluations of games, and it might be a useful tool for researchers developing serious games.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Lina Kröncke for leading the adaptation workshops; the YouTube account Saliival for helping us recruit adolescents; Michael Weber, Uwe Graichen and Sascha Klee for their statistical consultation; and Mikki Phan for giving us permission to use the original GUESS-18. We acknowledge support by Open Access Publishing Fund of Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abeele, V. V., K. Spiel, L. Nacke, D. Johnson, and K. Gerling. 2020. “Development and Validation of the Player Experience Inventory: A Scale to Measure Player Experiences at the Level of Functional and Psychosocial Consequences.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 135: 102370. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.102370.

- Abma, T., S. Banks, T. Cook, S. Dias, W. Madsen, J. Springett, and M. T. Wright. 2019. Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93191-3

- Aydın, S., L. Harputlu, Ş Savran Çelik, Ö Uştuk, S. Güzel, and D. Genç. 2016. “Adapting Scale for Children: A Practical Model for Researchers.” International Contemporary Educational Research Congress, Turkey.

- Beaton, D. E., C. Bombardier, F. Guillemin, and M. B. Ferraz. 2000. “Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures.” Spine 25 (24): 3186–3191. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

- Behr, D. 2017. “Assessing the Use of Back Translation: The Shortcomings of Back Translation as a Quality Testing Method.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (6): 573–584. doi:10.1080/13645579.2016.1252188.

- Bell, A. 2007. “Designing and Testing Questionnaires for Children.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12 (5): 461–469. doi:10.1177/1744987107079616.

- Berkman, Mİ, B. Bostan, and S. Şenyer. 2022. “Turkish Adaptation Study of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale: GUESS-TR.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 38 (11): 1081–1093. doi:10.1080/10447318.2021.1987679.

- Bevan Jones, R., P. Stallard, S. S. Agha, S. Rice, A. Werner-Seidler, K. Stasiak, J. Kahn, S. A. Simpson, M. Alvarez-Jimenez, and F. Rice. 2020. “Practitioner Review: Co-Design of Digital Mental Health Technologies with Children and Young People.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 61 (8): 928–940. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13258.

- Blumberg, F. C., and S. M. Fisch. 2013. “Introduction: Digital Games as a Context for Cognitive Development, Learning, and Developmental Research.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2013 (139): 1–9. doi:10.1002/cad.20026

- Borgers, N., E. De Leeuw, and J. Hox. 2000. “Children as Respondents in Survey Research: Cognitive Development and Response Quality 1.” Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 66 (1): 60–75. doi:10.1177/075910630006600106.

- Bottel, M., and H. Kirschner. 2019. “Digitale Spiele.” In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, edited by N. Baur and J. Blasius, 1089–1102. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Brockmyer, J. H., C. M. Fox, K. A. Curtiss, E. McBroom, K. M. Burkhart, and J. N. Pidruzny. 2009. “The Development of the Game Engagement Questionnaire: A Measure of Engagement in Video Game-Playing.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45 (4): 624–634. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.016.

- Cahill, C. 2007. “Doing Research with Young People: Participatory Research and the Rituals of Collective Work.” Children’s Geographies 5 (3): 297–312. doi:10.1080/14733280701445895.

- Cheung, G. W., and C. Wang. 2017. “Current Approaches for Assessing Convergent and Discriminant Validity with SEM: Issues and Solutions.” Academy of Management Proceedings.

- Clark, L. A., and D. Watson. 2016. Constructing Validity: Basic Issues in Objective Scale Development.

- Colina, S., N. Marrone, M. Ingram, and D. Sánchez. 2017. “Translation Quality Assessment in Health Research: A Functionalist Alternative to Back-Translation.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 40 (3): 267–293. doi:10.1177/0163278716648191.

- Curran, P. J., S. G. West, and J. F. Finch. 1996. “The Robustness of Test Statistics to Nonnormality and Specification Error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Psychological Methods 1 (1): 16. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16.

- Dancey, C. P., and J. Reidy. 2007. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- De Lima, L. G. R., A. de Lima Salgado, and A. P. Freire. 2015. “Evaluation of the User Experience and Intrinsic Motivation with Educational and Mainstream Digital Games.” Proceedings of the Latin American Conference on Human Computer Interaction.

- Eisinga, R., M. Te Grotenhuis, and B. Pelzer. 2013. “The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown?” International Journal of Public Health 58 (4): 637–642. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3

- Engl, S., and L. E. Nacke. 2013. “Contextual Influences on Mobile Player Experience – A Game User Experience Model.” Entertainment Computing 4 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.entcom.2012.06.001.

- Ermi, L. 2005. Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion.

- Federoff, M. A. 2002. Heuristics and Usability Guidelines for the Creation and Evaluation of Fun in Video Games. Indiana University Bloomington.

- Gangrade, K. 1982. “Methods of Data Collection: Questionnaire and Schedule.” Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (4): 713–722. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43950835.

- Hair, J. F., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19 (2): 139–152. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202.

- Hall, J., M. Gaved, and J. Sargent. 2021. “Participatory Research Approaches in Times of Covid-19: A Narrative Literature Review.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20. doi:10.1177/16094069211010087.

- Hamari, J., J. Koivisto, and H. Sarsa. 2014. Does Gamification Work?-A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. Waikoloa, HI: HICSS.

- Henseler, J., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. “A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

- Inan Nur, A., H. Santoso, and O. Hadi Putra. 2021. “The Method and Metric of User Experience Evaluation: A Systematic Literature Review.” 2021 10th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications.

- Involve, N. 2019. What is Public Involvement in Research. Accessed 14 November 2019. www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/.

- Jackson, D. L., J. A. Gillaspy, and R. Purc-Stephenson. 2009. “Reporting Practices in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: An Overview and Some Recommendations.” Psychological Methods 14 (1): 6. doi:10.1037/a0014694.

- Jagosh, J., A. C. Macaulay, P. Pluye, J. Salsberg, P. L. Bush, J. Henderson, E. Sirett, G. Wong, M. Cargo, and C. P. Herbert. 2012. “Uncovering the Benefits of Participatory Research: Implications of a Realist Review for Health Research and Practice.” The Milbank Quarterly 90 (2): 311–346. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.xC.

- Jennett, C., A. L. Cox, P. Cairns, S. Dhoparee, A. Epps, T. Tijs, and A. Walton. 2008. “Measuring and Defining the Experience of Immersion in Games.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 66 (9): 641–661. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.04.004

- Jon, K. 1991. “Response Strategies for Coping with the Cognitive Demands of Attitude Measure in Surveys.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5: 213–236. doi:10.1002/acp.2350050305

- Ke, F. 2011. “A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of Computer Games as Learning Tools.” In Gaming and Simulations: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications, 1619–1665. New York, NY: IGI Global.

- Keebler, J. R., W. J. Shelstad, D. C. Smith, B. S. Chaparro, and M. H. Phan. 2020. “Validation of the GUESS-18: A Short Version of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS).” Journal of Usability Studies 16: 1. https://commons.erau.edu/publication/1508.

- Kenny, D. A. 2015. Measuring Model Fit. https://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

- Koller, M., V. Kantzer, I. Mear, K. Zarzar, M. Martin, E. Greimel, A. Bottomley, M. Arnott, and D. Kuliś. 2012. “The Process of Reconciliation: Evaluation of Guidelines for Translating Quality-of-Life Questionnaires.” Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 12 (2): 189–197. doi:10.1586/erp.11.102.

- LaPietra, E., J. B. Urban, and M. R. Linver. 2020. “Using Cognitive Interviewing to Test Youth Survey and Interview Items in Evaluation: A Case Example.” Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation 16 (37): 74–96. doi:10.56645/jmde.v16i37.651

- Leonhardt, M., and S. Overå. 2021. “Are There Differences in Video Gaming and Use of Social Media among Boys and Girls? A Mixed Methods Approach.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (11): 6085. doi:10.3390/ijerph18116085.

- Mallery, P. 2003. SPSS for Windows Step by Step. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Marchand, A., and T. Hennig-Thurau. 2013. “Value Creation in the Video Game Industry: Industry Economics, Consumer Benefits, and Research Opportunities.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27 (3): 141–157. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2013.05.001.

- McDonald, R. P., and M.-H. R. Ho. 2002. “Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses.” Psychological Methods 7 (1): 64. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64.

- Mittmann, G., A. Barnard, I. Krammer, D. Martins, and J. Dias. 2022. “LINA - A Social Augmented Reality Game around Mental Health, Supporting Real-world Connection and Sense of Belonging for Early Adolescents.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6 (CHI PLAY): 1–21. doi:10.1145/3549505.

- Mittmann, G., K. Woodcock, S. Dörfler, I. Krammer, I. Pollak, and B. Schrank. 2021. ““TikTok is My Life and Snapchat is My Ventricle”: A Mixed-Methods Study on the Role of Online Communication Tools for Friendships in Early Adolescents.” The Journal of Early Adolescence, doi:10.1177/02724316211020368.

- Montreuil, M., A. Bogossian, E. Laberge-Perrault, and E. Racine. 2021. “A Review of Approaches, Strategies and Ethical Considerations in Participatory Research With Children.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20. doi:10.1177/1609406920987962.

- Phan, M. H., J. R. Keebler, and B. S. Chaparro. 2016. “The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS).” Human Factors 58 (8): 1217–1247. doi:10.1177/0018720816669646.

- Rodriguez-Barcenilla, E., and F. Ortega-Mohedano. 2022. “Moving Towards the End of Gender Differences in the Habits of Use and Consumption of Mobile Video Games.” Information 13 (8): 380. doi:10.3390/info13080380.

- Ryan, R. M., C. S. Rigby, and A. Przybylski. 2006. “The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.” Motivation and Emotion 30 (4): 344–360. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8

- Schreiber, J. B., A. Nora, F. K. Stage, E. A. Barlow, and J. King. 2006. “Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review.” The Journal of Educational Research 99 (6): 323–338. doi:10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

- Sousa, V. D., and W. Rojjanasrirat. 2011. “Translation, Adaptation and Validation of Instruments or Scales for Use in Cross-Cultural Health Care Research: A Clear and User-Friendly Guideline.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 17 (2): 268–274. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x.

- Subhash, S., and E. A. Cudney. 2018. “Gamified Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Computers in Human Behavior 87: 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.028.

- Susi, T., M. Johannesson, and P. Backlund. 2007. Serious Games: An Overview. shorturl.at/glPY9.

- Tenzer, F. 2022. Umfrage zu den beliebtesten Games bei Jugendlichen 2021. Statista. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1251776/umfrage/beliebteste-games-bei-jugendlichen/.

- Tourangeau, R. 1984. “Cognitive Science and Survey Methods: a Cognitive Perspective.” In Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge Between Disciplines, edited by T. Jabine, M. Straf, J. Tanur, and R. Tourangeau. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Tsitsika, A. K., E. C. Tzavela, M. Janikian, K. Olafsson, A. Iordache, T. M. Schoenmakers, C. Tzavara, and C. Richardson. 2014. “Online Social Networking in Adolescence: Patterns of Use in Six European Countries and Links with Psychosocial Functioning.” Journal of Adolescent Health 55 (1): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.010.

- Unger, H. 2013. Partizipative Forschung: Einführung in die Forschungspraxis. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag.

- Wild, D., A. Grove, M. Martin, S. Eremenco, S. McElroy, A. Verjee-Lorenz, and P. Erikson. 2005. “Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation.” Value in Health 8 (2): 94–104. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x.

- Willis, G. B. 2004. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Woolley, M. E., G. L. Bowen, and N. K. Bowen. 2004. “Cognitive Pretesting and the Developmental Validity of Child Self-Report Instruments: Theory and Applications.” Research on Social Work Practice 14 (3): 191–200. doi:10.1177/1049731503257882.