ABSTRACT

Men’s sheds are community spaces where older, retired men come together to conduct woodworking and other types of craftwork and DIY activities. There is little research on exploring how technology can help us understand shed members’ perceived values associated with men’s sheds. In order to investigate this further, we designed and deployed a mobile storytelling application called ShedBox for an Australian men’s shed for over six weeks. ShedBox allows shed members to share audio-visual stories. Our analysis of resulting 58 stories and follow-up interviews with 13 shed members unpacked three important themes: a sense of comradery, kinship and companionship present within the shed; material and emotional engagement with the space; and, health and wellbeing of shed members. Our results also highlight a strong masculine culture of the space and how the shed is a site of active learning and engagement for its members. Lastly, our conclusion presents suggestions regarding how such forms of storytelling technology can be leveraged in similar contexts, and also how they can be effectively designed to support different demography.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

There has been a rise in community-based initiatives which help older adults socialise, be a part of meaningful community work, and deal with the process of ageing in a better way. One such example of community-led initiatives is a men’s shed. Men’s sheds are exemplary spaces for older men to get together, involve in woodworking, and socialise with other older men of similar age. Although there is a wide pool of research on men’s sheds themselves, touching on various aspects such as its impact on the health and wellbeing of its attendees (Carsten Citation2013; Jean Clandinin and Michael Connelly Citation2004; Mackenzie et al. Citation2017; Robin Citation2008; Wilson and Cordier Citation2013) or its focus on DIY and making (Anderson and Vyas Citation2022; Ballinger, Talbot, and Verrinder Citation2009; Mackenzie et al. Citation2017; Vyas and Quental Citation2022), few researchers have studied how a technology, or any form of technological intervention, might impact these spaces.

Men’s sheds are well established in countries like Australia, England, Ireland, New Zeeland, Canada among others and represent a strong masculine, shed culture (Bell and Dourish Citation2007). Focusing on its masculinity, Bell and Dourish (Bell and Dourish Citation2007) commented, ‘it is a site of male habitation and practice, … the association of sheds with tinkering, with danger, with dirt, etc – are strongly gendered too’. Men’s sheds as community organisations are predominantly shared social spaces, giving room to men to share stories, jokes, and immerse themselves in a communal environment. With the goal to explore how a storytelling application can engage shed members, we designed, developed and deployed a mobile storytelling application called ShedBox. ShedBox is designed to serve as a technology probe (Hutchinson et al. Citation2003) – as a situated display that allowed men’s shed members to create and share stories in the form of an audio clip and post them on a shared platform along with an image and a title.

In the Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) research storytelling has been extensively used in various contexts, including health (Grimes et al. Citation2008), community (Frohlich et al. Citation2009) and household settings (Saksono and Parker Citation2017). EatWell (Grimes et al. Citation2008), for example, is an audio-based storytelling system focused on enabling participants to share their stories related to eating habits and practices. In a low-income community setup, this type of storytelling enables better awareness of healthcare needs and community cohesion. Storytelling is seen to be a powerful social tool that has also been used to support behaviour change in domestic settings (Saksono and Parker Citation2017).

In this paper, we present the results of a six-week-long study that we undertook at a men’s shed in Australia, wherein we deployed the ShedBox. Following the initial deployment of the ShedBox over four weeks, shed members shared 58 stories focusing on various topics. Following this, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 13 shed members who interacted with ShedBox, mainly to understand their overall experience of using the ShedBox. This paper’s contributions are twofold. First, it provides an empirical account of a technological intervention into a men’s shed. While men’s shed and makerspaces have been well studied in the literature, a technological intervention and its effects on members have not been well studied. Second, we show manifestation of digital storytelling in a gendered space and show how these stories represented the overall ethos of the space.

2. Literature review

2.1. Sharing narratives through digital storytelling

An important pillar of the human experience is the act of storytelling: the process of sharing and communicating ideas and stories with people one cares about and lives with (Jean Clandinin and Michael Connelly Citation2004). This process has recently been retrofitted into a digital context, given the rising democratisation and accessibility of media (Burgess Citation2006). Ever since, there has been a noticeable upsurge in the sharing of narratives, memories, and stories, not just on social media sites such as Facebook or Twitter but also independent applications, in forms of audio, photos or video. This has increasingly been the case where digital technologies have helped traditional forms of communication practices such as storytelling and scrapbooking by essentially acting as affordances. Digital storytelling is not a novelty within the sphere of HCI and there is ample amount of literature (Clarke, Wright, and McCarthy Citation2012; Frohlich et al. Citation2009; Grimes et al. Citation2008; Lili et al. Citation2018; Vyas and Quental Citation2022) that highlight how stories often elicit emotional responses from the people listening to them and build an environment of active engagement.

Stories and storytelling have been long associated with our cultures and have shown to support a sense of belonging and community building (Alexandrakis, Chorianopoulos, and Tselios Citation2020). Various literature has acknowledged the emotional and therapeutic side of storytelling (de Jager et al. Citation2017; Lambert Citation2013; Vyas and Quental Citation2022). Stories can be an outlet for people to form better relationships with people around them and share lived experiences with each other. In this way, storytelling offers people a way to communicate a lifetime worth of experiences and develop a sense of shared understanding (East et al. Citation2010). In older adults specifically, research has shown how being involved in the simple act of sharing stories has numerous benefits, such as improved social health, an increase in resilience (Mager Citation2019), and finding meaning and purpose within everyday life (Katie and Kayler Citation2009).

In HCI, storytelling has been extensively used in various contexts, including health (Grimes et al. Citation2008), community (Frohlich et al. Citation2009) and household settings (Saksono and Parker Citation2017). Predominantly photos have been the most popular visual and dominant cue in HCI studies (Petrelli et al. Citation2010; Petrelli, Whittaker, and Brockmeier Citation2008), but there has been some research (Jayaratne Citation2016; Petrelli et al. Citation2010) to explore sound as a medium of sharing stories and memories in controlled environments. EatWell (Grimes et al. Citation2008) is an audio-based storytelling system that allows members from a low-income community to share their nutrition-related stories. The idea here is to enable the community to be aware of good practices around healthy eating habits. The use of audio showed a strong emotional relevance and enabled much stronger reactions from the community. However, there is not much research conducted on shared auditory storytelling in the context of older people and how it might affect them. With a lifetime worth of experiences behind them, there is an untapped opportunity within both storytelling and geriatric literature to explore how older adults respond to storytelling, especially in newer digital formats. Studies such as (Churchill and Nelson Citation2007; Memarovic et al. Citation2012; Wouters, Huyghe, and Moere Citation2014) explore how interactive public displays are successful at building ‘conversational hubs’ that stimulate engagement within the community. Such displays, deployed in a wide variety of contexts, have been successful in serving as playful hubs, promoting conversation and opening up opportunities for people to discover or stumble upon new things. Overall, there is scope to explore how these ideas could be melded together in the context of already-established community spaces such as men’s sheds, and how they can positively benefit them.

2.2. Community wellbeing and health in men’s sheds

With a steadily rising ageing population in Australia (Kendig, McDonald, and Piggott Citation2016), the health of older adults in the community is gaining widespread attention (Ageing in Australia and the Increased Need for Care Citation2021; Davis and Bartlett Citation2008). Ageing is a social, cognitive and psychological process, which affects the way people interact with technology (Alexandrakis, Chorianopoulos, and Tselios Citation2020). Of noteworthy interest is the deteriorating social and mental health of older men, especially those who are transitioning from work to retirement (Donovan and Blazer Citation2020), and studies around community-based initiatives that help people cope with the process of aging (MacKean Citation2010; MacKean and Abbott-Chapman Citation2012; Merchant et al. Citation2021).

Men’s sheds, significantly popular in Australia and other international communities, are one such community-based initiative that aims to promote physical and mental health within older men, with significant presence of retired men. These are predominantly workshop-based spaces where men can come in, discuss ideas, and build artefacts or tools for the community. This act of making and sharing their processes has had a positive impact on their physical, emotional and spiritual wellbeing (Carsten Citation2013; Jean Clandinin and Michael Connelly Citation2004; Robin Citation2008). According to Cox et al. (Citation2020), these sheds have been a subject of a wide amount of research, ranging from an exploration of masculinity to leadership within the shed to beneficial effects on the emotional and social wellbeing of Shed members. Sheds are seen as a place for ‘refuge’ (Bell and Dourish Citation2007) for men where they can conduct activities that can range from drinking beers to working on DIY projects. So, it is important to see men’s sheds as a space where men want to have an outlet away from their family lives. In this sense, men’s sheds are not only spaces where men conduct woodworking and other type of making; they are spaces for social gatherings and comradery.

The shed environment, designed to be social with other adults of the same age and similar interests, opens a possibility to explore and further understand the deeper dynamics within a shed. Sheds are non-judgmental, casual spaces that support male-friendly banter (Mackenzie et al. Citation2017), thus contributing to a healthier space for men to open-up and unwind. A feeling of pride and accomplishment is pretty commonly experienced by shedders (Ballinger, Talbot, and Verrinder Citation2009), so it would be interesting to explore how the act of sharing with others can help improve this sense of accomplishment and the feeling of doing something significant for the community. Additionally, there has also been research (Brooks Citation2001; CitationMilligan et al.) on how initiatives such as men’s sheds fit into larger narratives of masculine discourse. These gendered spaces are often brimming with gendered discussions and jokes – they root for an independence of male-friendly spaces. Mackenzie et al.’s (Citation2017) findings from a Canadian shed showed how masculinity is intrinsically shaped within men’s sheds, and how gender dynamics are an important area of investigation within men’s sheds. Thus, it would be beneficial to explore this aspect of the shed further and see how a form of technology can more appropriately capture it. Community men’s sheds are multifaceted spaces which have proved to be successful for older men in regaining control over various aspects of their health, be it mental, physical or social, through the form of active involvement, making and providing them with a sense of comradery and community.

3. The study

3.1. The men’s shed settings

The men’s shed we engaged with was located in a metropolitan city in Australia. The setting and overall work practices of the men’s shed are described in Vyas and Quental (Citation2022). The shed had over 100 members in their registry and around 30–40 members attended at any given day. The membership consisted of predominantly retired older men, aged between 65 and 85 years. The shed was adjacent to a church and was open five days a week, from 8:00 am to midday. Starting from 10:00 am, shed members get together in a common space to have their tea breaks. Here, announcements are made to introduce new members to share any latest developments at the shed. Sometimes, information around the key projects that were being run at the shed was also shared.

The shed allowed younger men to be members. Shed members, also known as ‘shedders’, worked in various mediums, such as wood, metal and leather. Once one project was completed, the shedders moved on to the next project, which could consist of both personal and community projects. Community projects included building artefacts for charities, orphanages or other non-profit organisations. Personal projects included the ones which members built for themselves, or for their friends and family.

3.2. Co-development of ShedBox

The design of ShedBox was a joint effort between the research team and shed members. One of the members of the research team had been a member of the shed for over four years and knew most of the members. During a tea break, the lead researcher proposed the idea of developing a storytelling application for the shed. After having initial brainstorming and consultations among members, it was agreed that shed members will participate in the design of the application. Shed members also suggested to design a simple application that would not require a lot of typing on their part and make the application more visual and peripheral so that it doesn’t require a lot of work for them when they interact with it. Shed members very actively checked the progress of our application development. It was decided that an application will run on an iPad which will be housed in a timber frame to make the application look an integral part of the shed members’ activities, which was woodworking. shows shed members developing the timber frame for an iPad and one of the researchers displaying the final version.

Figure 1. Shed members designing the outer case of ShedBox and final design being discussed during a tea break.

The ShedBox () is designed as a technology probe (Hutchinson et al. Citation2003), which works as a situated display placed on a table close to the noticeboard of the men’s shed. Much like the Whereabouts Clock (Sellen et al. Citation2009), the display of the ShedBox is always ‘on’ and always existed in the visual periphery of shedders, so they could simply walk up to it and share their story at any time. The ShedBox interface allowed participants to upload ‘stories’, which were essentially a combination of a voice a recording, a picture, and a title. This allowed them to capture a very specific moment in time in three different forms of media, with an emphasis on the auditory aspect of the story. The title and the image stood as supplementary background information, providing additional context to the story being shared by the shedder. ShedBox was connected to the shed’s Wi-Fi, so that it causes minimum amount of interference to the user when interacting with the application. Thus, a participant could instantly browse through the stories on the home screen or upload their own story within a matter of few seconds. The shed members could perform two activities:

Listen to stories shared by other shed members in the form of a carousel. Members could scroll through different stories and listen to stories on the main screen at any given time.

Upload their own stories by going through a simple upload flow, which would then be added to the homepage carousel.

3.3. Methods and participants

Following the ethical clearance process in our institution, we met with the management of the men’s shed to discuss our research methods. Prior to the deployment of ShedBox, we got shed members to sign informed consents about our project, where we ensured that no identifiable information from the members will be shredded outside of the project. Over the period of the first four weeks, the ShedBox was deployed as a situated storytelling device. In this phase of the deployment, we went up to shedders and asked them to report anything that they would like to mention about the presence of the ShedBox in their space. While we had a strong buy-in from the shed members, we provided a demo of ShedBox whenever a member unfamiliar with the ShedBox showed up. We also suggested that members can use ShedBox to make any announcements to the shed, their current projects, or discuss any other issue about the shed.

Following the four-week data collection period, we received 58 entries in the ShedBox. Following this, we organised semi-structured interviews which aimed at understanding what made shed members share certain stories. We recruited 13 members (participants P1–P13) from the shed who were active users of the ShedBox and showed an interest to discuss their experiences with us. These interviews were audio recorded and structured in a way where we played some stories from the ShedBox to the interviewee and asked them to share their thoughts on the story. Thereafter, we posed open-ended questions to participants regarding their experiences at the shed, in connection to the ShedBox. During this phase, we also collected feedback on any further improvements to the application. As a token of appreciation for their time, the shed was given a $200 gift voucher for allowing the research team to conduct this project and allowing the shed members to participate in the study. The shed members who participated in this study collectively decided that the gift vouchers should be given to the shed rather than to participating individuals.

The 58 stories and interviews from 13 participants were analysed using the thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) method. Here, an inductive analysis of the qualitative data obtained from both the semi-structured interview as well as the stories collected by ShedBox was conducted. We transcribed the interviews and coded them along with the stories. We clustered the codes together to perform a basic thematic analysis and obtained the overall themes that came across in all the data generated. The section below discusses these findings in more detail.

4. Findings

4.1. System use overview

Overall, men’s shed members enjoyed using the ShedBox and had positive reviews for it. For instance, when asked for his first thoughts on the device, one participant enthusiastically said

Well, what can I say? I was blown away! I think this is amazing technology. To have it all so incredibly versatile, easy-to-use, and the concept of being able to speak into, and record yourself for the recording to be accessible to other blokes, I think it’s tremendous..

Which expressed a positive reaction to the user-friendliness of the device and the ability to hear stories uploaded by other shed members. Another participant noted,

This could even replace the Shed Newsletter. I basically see it as an electronic version of the newsletter, one which has auditory capabilities so people can just listen to it instead of reading it. We can use it for anything that we want. We can make it a one-stop-shop for a whole range of things. Definitely has a lot of potential of being developed as far as we want.

Reflecting on the flexibility of the device and on the variety of contexts it could be used in at the shed.

Over the course of four weeks of deployment, 58 legible stories were added to the ShedBox. The average duration of a story was 1 min, with shortest one lasting only 2 s (hence discarded), and the longest one being a conversation between a shed members lasting over 6 min. The shed members added an average of three stories to the ShedBox, with the minimum being one story and the maximum being eight stories, per shed members. From our analysis, we established seven categories of stories (), which were essentially sub-themes to a broader set of three main overarching themes: Kinship; Health and Wellbeing; and Material & Physical Engagement. Sixteen stories belonged to the theme of Kinship, 10 belonged to that of Health & Wellbeing, whereas 32, the maximum number of stories, belonged to Material and Physical Engagement. The following table provides a breakdown of different types of stories collected.

Table 1. Stories collected through the deployment of ShedBox.

In the section below, we will provide further details of the specific themes and discuss examples stories from our participants. We highlight how these stories were both revelatory and insightful into the lives of shedders.

4.2. Kinship

In What kinship is – and is not, Marshall Sahlin (Citation2013) develops a deeper account of what kinship can encompass, and what is instantly recognisable in it – ‘participating intrinsically in each other’s existence’, having ‘mutuality of being’ and being ‘members of one another’ (Carsten Citation2013). In this sense, kinship refers to a general sense of affinity or attachment between members of a particular social group. In community-based programmes such as men’s sheds, kinship is quite ubiquitous.

The stories captured the social dynamics of kinship within the space. Shedders shared a range of activities they did at the shed, ranging from caring for the tools and equipment in the shed library, to supervising other members in order for them to complete their projects successfully, to showcasing their ongoing projects that were meant to show care for people outside of the shed community (e.g. families).

According to the thematic analysis conducted, we found that stories about kinship had recurring sub-themes of caring for the members in the shed and the shed itself, along with showing affection and caring about friends, family and other members outside of the shed membership. P4 very aptly described this feeling of giving back to whom they cared for, ‘being a master craftsman is very good, but it is only for your own amusement. When you do something for someone else, it adds an extra layer of satisfaction and an extra feel-good factor to it’. In this sense, stories were crafted to emphasise the kinship aspect.

4.2.1. Kinship within the shed – caring about others at the shed

From the 16 stories collected surrounding kinship, 10 stories highlighted kinship within the shed. These stories ranged from appreciating the shed as a social outlet for members to care and comradery that is prevalent at the shed to helping one another at the shed. In the following discuss one such example in , where a story shared by P8 is described.

Table 2. A story of kinship within the shed, by P8.

Like many other members at the shed, P8 came to shed mainly to have social interactions with other like-minded people at the shed. He had made a group of friends who would sit and talk at the shed. P8 and other members do not generally participate in woodworking or any other type of craftwork at the shed, rather they would lead organising social and outreach activities at the shed. To participants like P8, the space provides a great social support in their post-retirement lives.

A part from the story shown in , there were several similar stories where shed members exhibited care and safety aspects related to the shed. Participant P13 shared a story on why it is important to keep the shed clean at the end of a session. Through his story he exhibited care towards other members as cleaning up is one of the most essential health and safety issue. Following this story, some participants felt that this was something where the ShedBox could primarily work well for making announcements for the wider shed membership. Hearing someone else’s story whilst being in periphery of the ShedBox could serve as a gentle reminder for them to clean up after themselves. Other story examples within this sub-theme included shedders sharing information about the shed library and helping supervise other shed members to provide guidance with their ongoing projects. Thus, ShedBox was able to capture snippets of life within the shed which was often passed by without anyone noticing – snippets of care, companionship and a shared sense of belonging.

4.2.2. Kinship outside the shed – showing affection to friends and family

The remaining 6 stories out of the 16 stories were classified as those relating to exhibiting kinship outside the shed through the ShedBox. This was shown in the form of building something for one’s family or friends, being an integral part of their lives and impacting it with their presence, thus showing affection and love to them. The ShedBox helped facilitate these projects by looking at what other people in the shed were building. As one participant P9 noted, it would help ‘Something to do for his grandkids’. P9 added a story about his ongoing project:

With the example story shared above, the pig made by a shedder for his granddaughter who lives in the US was shared with a few participants and their reactions were gauged. It was commonly observed that shedders were frequently involved in doing projects that were meant as a gift for their family members. Shedders often felt that adding personal touch to such gift would bring meaningful and cherished experiences for their loved ones. Stories similar to the one shown in struck a chord among the shed members. While some shedders would know about ongoing projects at the shed, for other it wasn’t possible due to the specific days they would come to the shed. What ShedBox enabled was making specific projects visible for the larger shed membership. Listening to the story helped shedders realise that it can help them to get to know other people better, that is through striking up a conversation with the shedder after hearing a story on the ShedBox. During our interviews, P11 commented that

This is fantastic. What is important here is what comes out of these stories, because it is information that one might necessarily not know about. You listen such stories and get to know the people you work with a bit better.

Table 3. Example story for kinship outside the Shed, by P9.

[Members] loved to show affection through something which they built. I think one of the difficult passages we go through in life is that as we grow older, we have these glorious grandkids who are 50-60 years younger than us. How do you relate to them? I’ve seen that one of the primary ways of connecting with them is through gifts, through toys. Through them, you can get closer to your grandkids. Because initially, I feel, they are a bit apprehensive of these old geriatrics, ways to get to them is make something that they enjoy playing with.

4.3. Wellbeing

The shed had a positive impact on the health of the shed members. It promoted a healthy social space for shedders to come and interact. The Shed members, although initially reticent, were happy to open up about their personal lives and how the shed influenced their lifestyle and general wellbeing. These have been discussed in depth below.

4.3.1. Comradery and sense of community

Out of the 10 stories which came under the theme of health and wellbeing, 6 stories were linked to a sense of community and comradery within the shed. This highlighted the importance of the shed in facilitating and providing a social space for comradery and companionship. presents a story that was uploaded by P6 on the ShedBox.

Table 4. Example story for comradery and sense of community, by P6.

In the story above, P6 reflected on his experience of coming to the shed. He talks about how shed positively impacted his mental health and provided a space for him to come to once or twice a week to chat to people who have been severely depressed in the last couple of years. During the interviews, several of the participants hinted that many of the shedders came through a difficult phase of their lives when they retired from their work. Being engaged in a meaningful activity and a lively social environment provided by the shed helped many such participants.

There were some interesting reactions to this story. P11, who does not actively get involved in making activities, said:

certain guys have got the concept of the shed the other way around. They come in for woodwork and metalwork, that’s their reason for being here because that is their thing. I do not have anything against that view, but I personally feel that for myself it is more about being a part of something. I have learnt more than just sitting and looking. The main reason for being here is to commune with other guys.

I think this story mirrors my own view about coming to the shed. My time at the shed provides some routine and structure to an otherwise unstructured day and week since I’m in retirement. In my own experience, I really value being able to come to the shed because of the same reason – it keeps me sane.

4.3.2. Impact on personal health

There were four stories which highlighted the impact of the shed on personal health of the shedders. These stories touched on how coming to the shed affected the shedder’s way of life, and how it contributed positively towards their physical and mental health. An example story is provided below (), along with some reactions from other shedders to the story.

Table 5. Example story for personal health, P7.

In the story shared above, P7 talks about how the shed has a positive impact on his health, and how the shed opens up a space for men to not only come and open up but also for other men to listen to them. He further elaborated on his story by commenting:

when older men say something, it’s an effort. It is a challenge. Unlike women. So, it is important to listen, because the speaker needs to have some sense of courage to talk about hard things.

As a reaction to this story, P3 commented:

This story kind of extends my thought process. In our culture, we always have gendered spaces – men’s spaces and women’s spaces. Men always have their own space, and they can talk about anything that they want. Here, in the west, men do not always get that. This is such a space, so I always see how it positively contributes to the wellbeing of everyone who comes in.

I would not be coming in if I didn’t enjoy this place. It provides a social contact touchpoint for me. For so many people, it so hard. I think it’s a question of exposure. For every one of us here, there is a 100 people out there who do not want to join.

Or as another participant introspected,

For me, this is what stops me from being in isolation. You can come here and do anything – you can sit, you can work, you can chat.

4.4. Material engagement with the space

The stories shared by the shed members also had a recurring theme of a sense of attachment with the spatial aspects of the shed – the tools, machinery and equipment present in the shed along with an active involvement with the process of making. The stories showed that the men were proficient at using the equipment and enjoyed engaging with the different tools available to them.

Being the most populated story category, there were a lot of stories which centred around seven main projects being worked on at the shed during the four-week period. The sections below aim to unpack these in more depth.

4.4.1. The fulfilment and materiality

For some men at the shed, the process of building something tangible was perceived as a huge achievement and was one of the reasons why they came to the shed. For instance, P1, a previous electrical engineer, shared a story () about a pool table that he built. He talked about the structure and the shape of the pool table in precise terms and had a knack for exactness. He also said how enjoying the ‘material aspect of making’ comes from his engineering background. The participant also said that he’s a ‘loner’ and enjoyed to ‘be kept busy with my hands and my mind for the time that I’m here at the shed’. This signified that making was almost seen as a meditative practice, giving shedders the time and space to focus on the present and unwind in an environment which they had control over.

Table 6. Example stories shared related to the material process.

For participants, the satisfaction and fulfilment of creating something at the shed was the most important aspect of making. They thoroughly enjoyed the creative process, albeit understanding that it can get taxing and sometimes frustrating, which they identified as a part of the process. This process of making linked back to the concept of ‘shed projects’ vs ‘personal projects’. Members worked on both kinds of projects for different kinds of reasons, and felt that the process was different for each kind of project. Shed projects felt more ‘philanthropic’ and associated to the ‘feeling of giving back something to society’, whereas personal projects more ‘intimate’, giving a peek into someone’s personal life.

One shed member P12, during the interview, ideated that he would love to document his creative process with the ShedBox. It could be used in stages: posting a little snippet before beginning something, documenting the progress while something is being built, and then discussing the process after they are done with building it. Doing so would also be beneficial to other shedders working on similar projects and would provide guidance through both auditory and visual mediums.

4.4.2. Expertise with tools and machinery

Some of the stories shared on the ShedBox suggested that shed members wanted to portray a highly proficient identity around the use of tools and machinery at the shed. Senior members had to regularly instruct and induct new members on how to use the machine appropriately. The members were confident about explaining processes such as sanding, lacquering, painting and sawing in depth, meticulously talking about how each tool is used and what machinery is useful for which part of the process. Some members of the shed were willing to help other shedders learn new processes, instilling educational attitudes whenever necessary.

There was an emphasis on getting things right, and some perfectionist attitudes were evident. There was frustration involved when something did not go according to plan, which stories such as ones in capture quite aptly. Nevertheless, there was a drive to continue and churn through the projects, as frustration was ‘a part of the process’, as noted by a participant during one of the interviews.

Table 7. Example stories shared related to the expertise with tools and machinery.

Another participant reflected on how the shed was a shared space of expertise, mentioning how ‘some people who might not have worked in a hands-on occupation or job get lifted and helped by people who are very happy to pass on their knowledge’. Thus, the finding also linked back to an overall sense of comradery, kinship and a willingness to help others, the space being one which is built on shared knowledge.

There were also attempts to adding a tech shed into the men’s shed space. P8, a former electrical engineer and IT professional, noted,

I want to run algorithm classes, Python classes, Scratch, and eventually, 3D printing. It's quite useful. Everyone is reading more and more about cybersecurity and hacking, so I feel through these people can understand more about that world.

4.4.3. Projects for external clients

Certain stories shared by our participants were centred around projects that they worked on for external clients, such as for orphanages, aged-care centres and churches. Stories which were shared in the ShedBox spanned across various organisations and purposes, such as a tablet stand built for orphanages, and bed frames built for physiotherapy clinics. The philanthropic vision of the shed members was evident through the stories shared in the ShedBox and suggested that the process of making gave the shed members a level of satisfaction, a feeling about making a difference in society through their work, no matter how small.

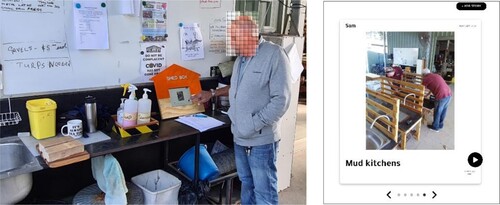

The below story () was uploaded by P7, where he discusses a mud-kitchen that was being painted for a childcare centre. Through the story explained the overall ethos and process of engaging with community organisations.

Table 8. Example story for projects for external clients.

When the above story was discussed with our participants during interviews, participants described the experience of making something for others as very inspiring. Participants felt proud of making artefacts and tools for other organisation. While the shed was a non-profit organisation, they needed to cover the cost of the material they buy. Individuals and community organisations who request men’s shed members to make artefacts and objects for them generally pay for the material costs or buy them. The men’s shed would not charge anything for their labour work but would ask for a small donation so that it can sustain for a longer period. Some of the participants mentioned that they received larger amounts in the range of $300–$500 from some generous donors. Participants also mentioned that saving such stories and projects in ShedBox is quite useful. It can highlight the philanthropic side of the men’s shed.

The reaction to this story made it evident that listening to the ShedBox stories reminded shedders of other instances, anecdotes and stories. Thus, a loop of storytelling was established, where listening to a story inspired another shedder to share theirs. This was an important aspect that ShedBox helped facilitate: people’s reactions to stories were often stories. Thus, it served as a positive trigger for shedders to verbalise their experiences at the shed and sharing things which they saw at the shed previously.

5. Discussion

The results of using the ShedBox as a technology probe over six weeks provided insights around lives of shed members for their time in the shed. Overall, our research sheds light on the complex relationship between older adults and technology and how the idea of storytelling fits within the ethos of community-led initiatives such as the men’s sheds. Further, findings highlight the role gender played in shaping the space.

5.1. Men’s shed ethos through storytelling

In this section, we highlight that the use of ShedBox and the stories that came out of it are aligned with the spirit and essence of the men’s shed movement. From cleaning the shed, to simply sitting and supervising other members, and from involving themselves in philanthropic projects to building toys for their grandchildren, the shed provided members a safe space without any obligations or pressure. More importantly, the mental health was of utmost importance, as highlighted in stories discussed in the previous section, and aligning with previous work on men’s sheds (Ballinger, Talbot, and Verrinder Citation2009; Cox et al. Citation2020; Moylan et al. Citation2015; Segura et al. Citation2019). The post-retirement support that was provided by the shed was also visible in the stories that were captured by our participants. For example, P6’s story about how the shed helps members who suffer from depression and how he as a senior member of the shed talks with them to help deal with such experiences. As shown in previous research (Donovan and Blazer Citation2020), social isolation is a huge problem in the aging population, the shed is a space for such members. Furthermore, making and the process surrounding it was captured aptly by ShedBox. The raw stories had the participants sharing experiences about what they were working on, trying to articulate the procedures, the tools that they were using, and who they were working with. As the ShedBox was conceptualised as a situated display, the stories were often filled with the background noises of cutting, shaving and sounds of heavy machinery. Thus, the masculinity of the shed culture (Bell and Dourish Citation2007; Cox et al. Citation2020) was also exhibited through ShedBox. The stories embodied the very spirit of the shed.

5.1.1. Care and altruism

It was very clear that while the shed was a space for woodworking, metalworking and involved various forms of physical labour, several participants conceived it as a space where they can meet friends, socialise and enjoy each other’s company. It was meant to be a space away from their homes and family members (Bell and Dourish Citation2007). It was not only for the use of equipment and tools that members came to the shed, it was the social environment that made the men’s shed what it is. Many of the shed members had similar type of setup in their own garages and sheds (at a smaller scale), but they chose to come to the men’s shed regularly. The stories shared in the ShedBox exhibited the notion of care that was inherent to the shed culture. Be it keeping the shed safe for other members (P13), to building toys for grandkids (P9) to generally checking on other members’ health and wellbeing (P6), care was definitely quite pervasive as one of the core ethos around the shed.

An aspect that is central to the ethos of men’s shed is supporting members who might be struggling through their post-retirement phase. P6’s story showed how some men find it difficult to talk about their personal issues, especially when they are adjusting to a new life post-retirement. Improving health and wellbeing of its members is an important aspect of the shed philosophy. ShedBox helped elevate some of these conversations to the fore, where members like P6 were able to make a point about the ethos of men’s shed.

Altruism was another major ethos of the men’s shed that was highlighted through the stories shared on the ShedBox. Shed members took pride in building objects and artefacts for other community-based organisations like childcare centres and physiotherapy clinics. While shed members did get involved in developing for their personal projects, the shed projects brought multiple shed members together as collaborative projects. Being able to do something for the society and people in need was greatly appreciated by the shed members.

5.2. Designing for older adults

We designed the ShedBox to be a simple tool where men’s shed members have to take only a few steps to successfully upload a story. This included simplified user-interface, where participants can flick through a carousel of cards, and making the buttons and text appropriate for older adults (Dodd, Athauda, and Adam Citation2017; Nurgalieva et al. Citation2017). There was a level of buy-in from the shed members to engage in some form of storytelling application at the shed. The appropriate amount of time given to them to engage with ShedBox also played a role in their interest in using a technology, echoing findings from (Vaportzis, Clausen, and Gow Citation2017).

During the interviews, multiple participants mentioned how they preferred listening to stories rather than reading something, a finding which is well aligned with findings of other story-based devices such as EatWell (Grimes et al. Citation2008). Fitting into one of the key themes that stemmed out of (Vyas and Quental Citation2022), ShedBox struck a chord with the men’s shed members because there was an emphasis on storytelling as an auditory phenomenon, and there was a greater resonance factor to spoken words as compared to the written words. In fact, one participant was enthusiastic about consuming the weekly newsletter in an auditory format, saying how ShedBox could even replace the shed newsletter. Participants had various viewpoints on how the ShedBox could be improved for further usage in the Shed. A few members at the shed were also keen to introduce video capabilities on the ShedBox, as they thought it would fuse audio and image together.

Overall, our research ties back into existing literature (e.g. Vetere et al. Citation2005), in that ShedBox helped people and specifically older adults share facts and feelings through stories and improve engagement both with each other as well as with the space. ShedBox, as a technology probe, can be designed and improved for a variety of contexts, is important to be flexibly used by people.

5.3. Masculinity, storytelling and speaking out

One of the key findings of the study was that the ShedBox was successful at capturing important aspects of the shed, and conversation which men were not always comfortable about. We noticed that gender was one of the axes for such findings. Brooks (Brooks Citation2001; Brooks and Silverstein Citation1995) discusses how ‘traditional masculine role socialization produces a wide range of interpersonal patterns and behaviors that are profoundly harmful to society and to men themselves’ (Brooks Citation2001, 287). Masculinity is often associated to ‘manning-up’, and not talking about personal and emotional issues one is going through. Contrary to that, the kind of masculinity we saw at the men’s shed was about being compassionate towards other men and supporting them in difficult times. As one can see in the story of P7, members saw the shed as a space where men can share their feelings and open up to others. In the same line of thought, P5 shared his view on how men’s sheds are one of the few spaces where older retired men can go to as an outlet away from their everyday activities. ShedBox added an extra layer to supporting this masculinity where shed member can find easier to share their thoughts and feelings in a form of a story, which provides an ease-of-use and a safe zone for people to disclose information to other shed members when they might not feel very comfortable disclosing it in-person.

Participant P7 during his interview discussed how in his culture, men usually have their own spaces, as compared to Euro-centric western cultures where spaces usually are equally shared by men and spaces. He flags this and discusses how men here usually do not have a space of their own. Thus, for men’s shed member’s, the sanctity of a male-exclusive space is quite important. They felt that they could share things more freely with each other and introducing women would alter the dynamics of the space drastically.

The ShedBox captured dynamics around masculinity within the shed in the form of stories. With a piece of technology in front of them, the men were able to verbalise on topics that they had not talked about before and opened up on issues which they wouldn’t open about generally in the shed. ShedBox also became a reason for shed members’ retrospective thinking about why they joined the shed in the first place and what attitudes were predominant in the shed. This further sets ground for future researchers to look into how technological interventions in such gendered places can help them.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have discussed how the deployment of an interactive storytelling situated display, ShedBox, as a technology probe was introduced to the shed members at a men’s shed in Australia. The results of our six-week-long study saw positive reactions to the ShedBox, and uncovered themes related to older men’s health and wellbeing, kinship and material engagement with the environment. The findings also uncovered the novel ways in which such simple pieces of technology could be incorporated into spaces such as men’s shed and positively impact both the space as well the people within it. In this way, our research study contributes to existing literature by exploring the deployment of technology in men’s sheds and enabling a culture of sharing stories within the shed. We believe that the long-term deployment of something like ShedBox can uncover different aspects of our findings, and also highlight the various kinds of values that are ever-present in the shed. A longer deployment period would also be interesting in seeing how the attitude of older adults change over time, and how comfortable they get with using technology in such contexts.

Our research also sets ground for future researchers to look into technology probes for exploring such makerspaces and investigate other design possibilities to improve its usage and utility within such environments. These have been discussed in the section below.

6.1. Future design possibilities

While ShedBox for designed as a probe to explore the role a technology can play in a makerspace-like environment, it showed potential for storytelling applications in men’s sheds and other relevant spaces. It was clear that storytelling activities can uncover larger issues around ethos of the space, it can potentially be used in other similar community spaces. Women’s craft groups (Vyas Citation2020) are one of the potential spaces where storytelling applications be applied. While the type of stories that come out of a women’s space may be different from a male-dominated space like a men’s shed, the overall discourse from these stories will inevitably include the ethos of such communities and prevalence of care within the space.

Future iterations of the ShedBox could explore supporting multimedia formats including video and text. The purpose of doing so would be to increase the versatility of the application and provide users with more options to go with. Video-based stories could add an extra layer of interactivity to the prototype. Audio-based and photo-based stories could be used to make shed-wide announcements or share jokes. Text-based stories could be looked into for complementing weekly shed newsletter. Participants also noted how the prototype could be used as not just within the shed, but as a promotional vehicle outside the shed, that is, something that their family members and other stakeholders could also interact with and look at. Researchers could further incorporate a familial dimension into their study and explore how such technologies could encourage intergenerational storytelling.

Ethics approval

The University of Queensland Human Ethics: 2020000332.

Acknowledgements

We thank our participants and the community men’s shed that engaged in this project. This paper is an extended version of Raunaq Bahl’s bachelor’s thesis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 https://www.ruok.org.au/ A health-focused campaign in Australia.

References

- Ageing in Australia and the Increased Need for Care. SpringerLink. Retrieved June 1, 2021 from https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/article/10.1007s12126-009-9046-3.

- Alexandrakis, Diogenis, Konstantinos Chorianopoulos, and Nikolaos Tselios. 2020. “Digital Storytelling Experiences and Outcomes with Different Recording Media: An Exploratory Case Study with Older Adults.” Journal of Technology in Human Services 38 (4): 352–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2020.1796893.

- Anderson, India, and Dhaval Vyas. 2022. “Shedding Ageist Perceptions of Making: Creativity in Older Adult Maker Communities.” Creativity and Cognition (C&C ‘22), 208–219. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3527927.3532800.

- Ballinger, Megan L., Lyn A. Talbot, and Glenda K. Verrinder. 2009. “More Than a Place to do Woodwork: A Case Study of a Community-Based Men’s Shed.” Journal of Men’s Health 6 (1): 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jomh.2008.09.006.

- Bell, Genevieve, and Paul Dourish. 2007. “Back to the Shed: Gendered Visions of Technology and Domesticity.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 11 (5): 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-006-0073-8.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brooks, Gary R. 2001. “Masculinity and Men’s Mental Health.” Journal of American College Health 49 (6): 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480109596315.

- Brooks, Gary R., and Louise B. Silverstein. 1995. Understanding the Dark Side of Masculinity: An Interactive Systems Model. In A new Psychology of Men. New York, NY, US: Basic Books/Hachette Book Group, 280–333.

- Burgess, Jean. 2006. “Hearing Ordinary Voices: Cultural Studies, Vernacular Creativity and Digital Storytelling.” Continuum 20 (2): 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310600641737.

- Carsten, Janet. 2013. “What Kinship Does—and How.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (2): 245–251. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau3.2.013.

- Churchill, Elizabeth F., and Les Nelson. 2007. “Interactive Community Bulletin Boards as Conversational Hubs and Sites for Playful Visual Repartee.” 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’07), 76–76. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2007.282.

- Clarke, Rachel, Peter Wright, and John McCarthy. 2012a. “Sharing Narrative and Experience: Digital Stories and Portraits at a Women’s Centre.” CHI ‘12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ‘12), 1505–1510. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2212776.2223663.

- Cox, Terrance, Ha Hoang, Tony Barnett, and Merylin Cross. 2020. “Older Aboriginal Men Creating a Therapeutic Men’s Shed: An Exploratory Study.” Ageing and Society 40 (7): 1455–1468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001812.

- Davis, Sandra, and Helen Bartlett. 2008. “Review Article: Healthy Ageing in Rural Australia: Issues and Challenges.” Australasian Journal on Ageing 27 (2): 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00296.x.

- de Jager, Adele, Andrea Fogarty, Anna Tewson, Caroline Lenette, and Katherine Boydell. 2017. “Digital Storytelling in Research: A Systematic Review.” The Qualitative Report 22 (10): 2548–2582. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2970.

- Dodd, Connor, Rukshan Athauda, and Marc T P Adam. 2017. Designing User Interfaces for the Elderly: A Systematic Literature Review, 12.

- Donovan, Nancy J., and Dan Blazer. 2020. “Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report.” The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 28 (12): 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005.

- East, Leah, Debra Jackson, Louise O’Brien, and Kathleen Peters. 2010. “Storytelling: An Approach That Can Help to Develop Resilience.” Nurse Researcher 17 (3): 17–25. doi:10.7748/nr2010.04.17.3.17.c7742.

- Frohlich, David M., Dorothy Rachovides, Kiriaki Riga, Ramnath Bhat, Maxine Frank, Eran Edirisinghe, Dhammike Wickramanayaka, Matt Jones, and Will Harwood. 2009. “StoryBank: Mobile Digital Storytelling in a Development Context.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘09), 1761–1770. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518972.

- Grimes, Andrea, Martin Bednar, Jay David Bolter, and Rebecca E. Grinter. 2008. “EatWell: Sharing Nutrition-Related Memories in a low-Income Community.” Proceedings of the 2008 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW ‘08), 87–96. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460579.

- Hutchinson, Hilary, Ben Bederson, Allison Druin, Catherine Plaisant, Wendy Mackay, Helen Evans, Heiko Hansen, et al. 2003. “Technology Probes: Inspiring Design for and with Families.” Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings.

- Jayaratne, Keisha. 2016. “The Memory Tree: Using Sound to Support Reminiscence.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 116–121. San Jose, CA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2851581.2890384.

- Jean Clandinin, D., and F. Michael Connelly. 2004. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. Jossey Bass Publishers.

- Katie, Scott, and DeBrew Jacqueline Kayler. 2009. “Helping Older Adults Find Meaning and Purpose Through Storytelling.” Journal of Gerontological Nursing 35 (12): 38–43. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20091103-03.

- Kendig, Hal, Peter McDonald, and John Piggott. 2016. Population Ageing and Australia’s Future. ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/PAAF.11.2016.

- Lambert, Joe. 2013. Digital Storytelling: Capturing Lives, Creating Community. Routledge.

- Lili, L., A. Rios Rincon, A. Miguel Cruz, C. Daum, and N. Neubauer. 2018. “DIGITAL Storytelling in Interventions With Older Adults – What Does The Literature Say?” Innovation in Aging 2 (Suppl 1): 317. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy023.1159.

- MacKean, R. M. 2010. Ageing Well: An Inquiry into Older People’s Experiences of Community-based Organisations. Rmaster. University of Tasmania. Retrieved June 1, 2021 from https://eprints.utas.edu.au/10722/.

- MacKean, Rowena, and Joan Abbott-Chapman. 2012. “Older People’s Perceived Health and Wellbeing: The Contribution of Peer-run Community-Based Organisations.” Health Sociology Review 21 (1): 47–57. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2012.21.1.47.

- Mackenzie, Corey S., Kerstin Roger, Steve Robertson, John L. Oliffe, Mary Anne Nurmi, and James Urquhart. 2017. “Counter and Complicit Masculine Discourse Among Men’s Shed Members.” American Journal of Men's Health 11 (4): 1224–1236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316685618.

- Mager, Barbara. 2019. “Storytelling Contributes to Resilience in Older Adults.” Activities, Adaptation & Aging 43 (1): 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2018.1448669.

- Memarovic, Nemanja, Marc Langheinrich, Florian Alt, Ivan Elhart, Simo Hosio, and Elisa Rubegni. 2012. Using Public Displays to Stimulate Passive Engagement, Active Engagement, and Discovery in Public Spaces, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1145/2421076.2421086.

- Merchant, Reshma A., C. T. Tsoi, W. M. Tan, W. Lau, S. Sandrasageran, and H. Arai. 2021. “Community-Based Peer-Led Intervention for Healthy Ageing and Evaluation of the ‘HAPPY’ Program.” The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 25 (4): 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1606-6.

- Milligan, Christine, Chris Dowrick, Sheila Payne, Barbara Hanratty, David Neary, Pamela Irwin, and David Richardson. Men’s Sheds and Other Gendered Interventions for Older Men: Improving Health and Wellbeing through Social Activity a Systematic Review and Scoping of the Evidence Base, 88.

- Moylan, Matthew M., Lindsay B. Carey, Ric Blackburn, Rick Hayes, and Priscilla Robinson. 2015. “The Men’s Shed: Providing Biopsychosocial and Spiritual Support.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (1): 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9804-0.

- Nurgalieva, Leysan, Juan Jose Jara Laconich, Marcos Baez, Fabio Casati, and Maurizio Marchese. 2017. Designing for Older Adults: Review of Touchscreen Design Guidelines. arXiv:1703.06317 [cs] (March 2017). Retrieved May 30, 2021 from http://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06317.

- Petrelli, Daniela, Nicolas Villar, Vaiva Kalnikaitė, Lina Dib, and Steve Whittaker. 2010. “FM Radio: Family Interplay with Sonic Mementos.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI 10, 2371–2380. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753683.

- Petrelli, Daniela, Steve Whittaker, and Jens Brockmeier. 2008. “AutoTopography: What Can Physical Mementos Tell Us About Digital Memories?” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ‘08, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357065.

- Robin, Bernard R. 2008. “Digital Storytelling: A Powerful Technology Tool for the 21st Century Classroom.” Theory Into Practice 47 (3): 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802153916.

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2013. What Kinship Is-And Is Not. University of Chicago Press.

- Saksono, Herman, and Andrea G. Parker. 2017. “Reflective Informatics Through Family Storytelling: Self-Discovering Physical Activity Predictors.” Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘17), 5232–5244. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025651.

- Segura, Elena Márquez, Laia Turmo Vidal, Luis Parrilla Bel, and Annika Waern. 2019. “Using Training Technology Probes in Bodystorming for Physical Training.” Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Movement and Computing (MOCO ‘19), 1–8. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3347122.3347132.

- Sellen, Abigail, Alex S. Taylor, Joseph ‘Jofish’ Kaye, Barry Brown, and Shahram Izadi. 2009. “Supporting Family Awareness with the Whereabouts Clock.” Awareness Systems 2009:425–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84882-477-5_18.

- Vaportzis, Eleftheria, Maria Giatsi Clausen, and Alan J. Gow. 2017. “Older Adults Perceptions of Technology and Barriers to Interacting with Tablet Computers: A Focus Group Study.” Frontiers in Psychology 8:1687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01687.

- Vetere, Frank, Martin R. Gibbs, Jesper Kjeldskov, Steve Howard, Florian “Floyd” Mueller, Sonja Pedell, Karen Mecoles, and Marcus Bunyan. 2005. “Mediating Intimacy: Designing Technologies to Support Strong-tie Relationships.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’05, 471. Portland, OR: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1055038.

- Vyas, Dhaval. 2020. “Altruism and Wellbeing as Care Work in a Craft-Based Maker Culture.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3, 1-12. ACM GROUP.

- Vyas, Dhaval, and Diogo Quental. 2022. “‘It’s Just Like Doing Meditation’: Making at a Community Men’s Shed.” Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 7, GROUP, Article 14 (January 2023), 28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3567564.

- Wilson, Nathan J., and Reinie Cordier. 2013. “A Narrative Review of Men’s Sheds Literature: Reducing Social Isolation and Promoting Men’s Health and Well-Being.” Health & Social Care in the Community 21 (5): 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12019.

- Wouters, Niels, Jonathan Huyghe, and Andrew Vande Moere. 2014. StreetTalk: Participative Design of Situated Public Displays for Urban Neighborhood Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1145/2639189.2641211.