Abstract

This study aims to determine which level of quality of child protection services reduces the demand for emergency child removals at the system level in Finland. A moderation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the dependent variable (the proportion of emergency child removals) and its predictors (the number of economically insecure families, and the proportion of completed needs assessment cases for child protection services within the statutory time-limit). The data on 292 municipalities during 2017–2019 were retrieved from the Sotkanet Indicator Bank (Finland). According to the results, the number of economically insecure families was associated with the demand for emergency child removals, but the higher quality of child protection services had a positive buffering effect on the relationship. The tentative results show that an essential factor in the demand for child protection services is the high quality of child protection services, an important consideration in allocating resources for services. The need for child protection is a complex issue that is often approached from an individualistic perspective. This study underlines the need for a broader and systemic-level review of child protection services.

Introduction

The need for child protection is a complex phenomenon but previous research has shown that certain disadvantages (i.e., social risks and personal problems) and the need for child protection services are inextricably associated (e.g., Conrad-Hiebner & Byram, Citation2020; Hunter & Flores, Citation2021; Authors, Citation2022, Citation2023). Social risks are typically defined as economic insecurity and low education level, whereas personal problems center on issues such as mental health problems and substance abuse. While all of these factors increase the risk of child protection involvement, the present study is focused only on economic insecurity, which is seen as a binder of other social risks and personal problems. With these limitations, economic insecurity is seen as a key indicator for the need of child protection (Hiilamo, Citation2009; Mulder et al., Citation2018).

An emergency child removal is an intervention that is focused on a child who is in immediate danger (Trocmé et al., Citation2014; Graça et al., Citation2018; Lamponen et al., Citation2019). The need for an emergency child removal may arise, for example, when a child’s parents are unable to care for their child in a proper manner, but a child’s own behavior can also be a factor (e.g., substance abuse and crimes committed) leading to urgent interventions (Authors, Citation2023). Although a child’s emergency placement out of her or his home is sometimes necessary and reasonable, it should always be the last option in child welfare. Social workers aim to avoid making this kind of urgent decision by cooperating with families at risk so they can access family support services.

Previous studies have focused on the availability and accessibility of preventive services for avoiding the need for emergency child removals (Lamponen et al., Citation2019), but there is less emphasis on quality of services, which however is a multi-dimensional phenomenon and is therefore problematic to operationalize (Stolt et al., Citation2011). In the literature, one of the most cited care quality conceptualizations is the Structure, Process, and Outcome Quality Paradigm developed by Donabedian (Citation1988). In the present study, quality of services is focused on the needs assessments that social workers should complete in three months according to the law. However, there is a remarkable variation between the Finnish municipalities in the completed needs assessments in the statutory time-limit, which leads us to assume that it might also be associated with the demand for emergency child removals. In this sense, it is assumed that the municipalities with good quality services have less need for child protection compared to the municipalities with poor quality services. The material of the study consists of Finnish municipalities (N = 292) and their macro-level indicators of child protection.

Emergency child removals in the Finnish context

Child welfare systems differ from country to country, and so do the practices involved in emergency removal interventions (Berrick et al., Citation2016). In Finland, municipalities provide social services for families with children, which are determined by law. These services can be divided into general social services (Social Welfare Act 1301/2014, Citation2014) and child protection services (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007), and both are provided by the municipalities. General social services are more preventive in their nature (such as childcare or counseling services) compared to child protection services where a family can get assistance in the form of a family worker who supports their daily activities.

The legislative mandate to report child abuse is a key element in ensuring that children at risk come to the attention of the child protection system. A child welfare notification may be initiated by officials such as the police, a physician, a youth worker, or a teacher. Those professionals are required to make a child welfare notification if they have identified conditions endangering a child’s development and care, or if they are concerned about a child’s own behavior (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007). Further, citizens also have the right to make a notification, but they have no legal obligation to do that (Räty, Citation2019, 212). The Child Welfare Act regulates the process of investigation of child welfare notifications, which has to be started within one week after the notification is received.

The actual assessment of the need for services will be initiated if it is found to be necessary according to a notification of an investigation into child welfare. The needs assessment for services must be completed within the statutory time-limit of three months (Section 36 of the Social Welfare Act). In 2022, 91.7% of the need assessments were completed within the statutory 3-month time limit (Statistics Report 28/2022, Citation2022). At the end of an assessment process, the social worker decides whether there is a case for child protection measures. If necessary, the client’s case will be referred to family support services (provided by child protection services) which include, for example, care and therapy services supporting the child’s rehabilitation, intensive in-home family work, and family rehabilitation. Family support services also include financial support for the child’s schooling, hobbies, maintaining close relationships, and other personal needs (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007). The main aim for providing services and support is to strengthen parenting and family cohesion. Family support services are provided on a voluntary basis with the consent of the child’s guardians, and a child must be older than 12 years (Räty, Citation2019, 317). To our knowledge, little research has been undertaken on the assessment of the need for services, and the factors related to it. Research on the impact of early support as part of the child welfare system should be increased to prevent situations of disadvantage (Jaakola Citation2020; Bilson & Martin Citation2016).

Taking a child out-of-home is always a last resort within the measures of child protection as it strongly interferes with people’s rights. Placing a child outside the home is an intervention that is preceded by the utilization of various family support services. In the case of non-emergency situations, the decision for an out-of-home placement is made by the child protection system (via social work) except for involuntary intervention, which is made by the administrative court (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007; Authors, Citation2022). According to statistics, 1.6% of children were placed outside the home in 2021 (Sotkanet Indicator Bank, Citation2020).

Emergency removals are made only in special cases and were 0.4% of actions by child welfare services in 2021. A decision on emergency removals can only be made by a social worker who is properly qualified under the law (Qualification Requirements for Social Welfare Professionals Act 272/2005, Citation2005). An emergency child removal must be made if deficiencies in the child’s care or other growth conditions threaten to seriously endanger the child’s health or development, or the child him/herself seriously endangers his/her own health or development (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007). The need for an emergency removal may arise, for example, when a child’s parents are under the influence of drugs, thus making them unable to care for their child in the proper way; or if the parents are under reasonable suspicion of child abuse, and a child is still assessed to be in danger (Authors, Citation2023). Furthermore, a child’s own suicidal behavior, substance abuse, and committing of crimes can also lead to emergency removals (Räty, Citation2019, 344–346).

An emergency removal can be justified only by the circumstances prevailing at the time of the decision. In principle, emergency removals cannot be based on predictions of possible future events. An emergency child removal decision is made with a duration of up to 30 days. The decision is made by a social worker who has been given the decision-making power by the municipality. Emergency removal can be continued if 30 days is not enough time to determine the need for the child’s custody, or to map out adequate support measures. Emergency removals can be extended for a maximum of 30 days if decision-making requires additional justifications and these cannot be obtained within the initial 30 days. A thirty-day extension of emergency removal has to be in the best interest of the child. The same person cannot make the decision on an emergency removal and its continuation (Child Welfare Act 417/2007, Citation2007). An emergency child removal ends when the basis for an emergency removal has ceased to exist. If the child can return home safely, a decision of termination of emergency removal must be made by the social worker who oversees the child (Räty, Citation2019, 344).

Economic insecurity and the need for child protection

In general, families in child protection live in economic insecurity more often than other families (Bywaters et al., Citation2018). In addition, low socioeconomic status has been linked to negative childhood experiences and development (Walsh et al., Citation2019). A systematic review of social factors affecting child health and maltreatment found that poverty, together with other uncertainties (such as parental education level and housing instability), was associated with the manifestation of child maltreatment (Hunter & Flores, Citation2021). Also, Hiilamo (Citation2009) states that the main reason for placing the child outside the home is often based on long-standing financial difficulties. Horwitz et al. (Citation2011) stated in a 30-month follow-up study of children placed outside the home that the family’s better financial situation was a protective factor in terms of being placed outside the home. In this sense, children from economically disadvantaged families are more often in a weaker position in life than children from families with a secured economic situation (e.g., Cooper & Stewart, Citation2013; Saar-Heiman & Gupta, Citation2020).

In the same line, material deprivation is a key factor associated with child maltreatment. Yang (Citation2015) provides evidence that material difficulties such as poor housing and inadequate food supply are associated with child neglect. In addition, Sedlak et al. (Citation2010) found that children from low socioeconomic status families were five times more likely to be maltreated than children from higher socioeconomic status families. Walsh et al. (Citation2019) claim, based on their literature review, that extensive research evidence supports the notion that a poorer socioeconomic status in childhood is associated with a greater risk of child abuse. In addition, community-level poverty has also been associated with child abuse. According to Eckenrode et al. (Citation2014), county-level income differences and child poverty rate are positively and significantly correlated to the amount of child abuse.

When considering all factors, Mulder et al. (Citation2018) found in their meta-analysis that although the connection between poverty and child neglect is clear, other risk factors (such as parents’ antisocial behavior or mental health problems) may have a greater effect on predicting neglect (see also Hiilamo, Citation2009). Further, Clément et al. (Citation2016) note that risk factors vary according to parental gender: mothers present more mental health problems, while fathers struggle more commonly with difficulties related to stress regarding combining family and work together. In this sense, poverty alone does not create challenges for a child’s development, but factors strongly connected to poverty include insecure housing, mental health problems, antisocial behavior, and stress experienced by parents (Duncan et al., Citation2014; Mulder et al., Citation2018). Poverty can, as a minimum, indirectly increase parental stress and thereby weaken parental health, and also it can increase the incidences of single parenthood and living in a high-risk environment (Carter et al., Citation2006). For instance, Duncan et al. (Citation2014) presented in their study that families whose financial situation improves also see an improvement in a child’s school success. In simplified terms, improving the financial situation of the parents clearly improves a child’s chances in life in general. On the other hand, the deterioration of the financial situation and, for example, the abolition of various supports, weakens a child’s ability to cope.

Quality of services and the need for child protection

The family situation is the most significant factor for explaining the need for child protection. However, it can also be thought that in some cases the child protection system fails to offer enough support for families at-risk, which in turn may also be a reason for child protection interventions. In this sense, the system itself and its quality-related problems may be causes for the demand for child protection interventions.

According to the aforementioned Structure, Process, and Outcome Quality Paradigm (Donabedian, Citation1988), the structural quality dimension describes the prerequisites for services, measured with indicators such as number of employees per client, status of used equipment, and the educational level of the employees. Process indicators describe the components of the encounter between professionals and the client, or effective procedures for social workers. Outcomes indicate the combined effects of structure and process on recipients’ satisfaction and well-being (see also, Malley & Fernández, Citation2010). However, Campbell et al. (Citation2000) have argued that outcome is not a component of care, but rather a consequence of care, thus in many studies only the structure and process factors are considered (Cleland et al., Citation2021).

The child protection process starts from a child welfare notification or other concern. The purpose of child protection is to secure the child’s wellbeing. However, a child’s out-of-home placement is always the last resort in child protection and therefore families are offered different supportive services. Fallon et al. (Citation2011) found that especially young parents benefit from services and support if concerns have been based on drug use, cognitive challenges, mental health problems, or physical health problems. Further, when assessing the need for services, it is important to consider the family’s experience of the process.

Child protection services are generally offered at a low threshold (Lamponen et al., Citation2019), which can be considered part of a high-quality child protection system. Child welfare workers should be given the necessary amount of time and resources to collect, evaluate, and consider the information for making justified decisions (Davidson-Arad et al., Citation2005). Urgent help given at home can prevent an emergency removal. In many cases, material support such as paying rent or overdue electricity bills can prevent the insecurity, and even exclude the need for emergency child removals (Pelton, Citation2008). Bullinger and Boy (Citation2023) found that federal income support provided to parents is associated with an immediate reduction in child abuse and neglect. This effect was determined based on the reports of emergency department visits to families at risk of child abuse and neglect.

It is essential to assess and determine, in coordination with the family, which interventions might be the most efficient to improve the family’s wellbeing and opportunities to live together, and in turn to secure the child’s wellbeing. Interventions can generally be considered as an effective way to improve the client’s situation. According to a review by Mullen & Shuluk (Citation2011), around one-third of clients benefited from an intervention in a significant way, and the positive results were maintained even when the factors, depending on the published work and the researcher, had been controlled for. The results are in line with the benefits of social work interventions found in previous studies (e.g., Gorey, Citation1996; De Smidt & Gorey, Citation1997). Interventions are therefore an important part of a high-quality social work system, and their effects on improving the client’s situation are significant (Gillingham, Citation2018).

However, Hope and Van Wyk (Citation2018) state that today’s interventions (in child protection) are rushed and crisis-oriented, which affects the emotional encounter with the child and the family. Further, the high demand for services has been found to be one of the major limiting factors in child protection services. For example, up to 22.5% of children born in England in the period 2009–2010 were referred to child welfare before the age of five years. Three-quarters of that sample were evaluated at some point, almost two-thirds were found to be in need of services, and around one-quarter were officially investigated. Every ninth child was subject to a child protection assessment due to suspicions of abuse (Bilson & Martin, Citation2016). Emergency interventions can be seen as a way to deal with these crises in certain cases, for example, if a child is physically abused. In that case, in order to protect the child, she/he must be removed to a safe environment, and only then can rehabilitation measures and services be planned for the family (Graça et al., Citation2018). Effective interventions act as a buffer for the family’s challenging situation, but enabling services and forms of support suited to the family situation is an essential part of a high-quality system.

Receiving services also depends on the area where the family lives. In the disadvantaged areas, the family can have less supportive services available than in other areas (Bywaters et al., Citation2020). The quality of child protection can be assumed to affect the effectiveness of child protection services, and how much one ends up doing interventions that are considered last resort, such as emergency removals. Efficient and well-functioning services should be able to minimize expensive interventions that greatly affect families’ lives (Horwitz et al., Citation2011; Garcia et al., Citation2014). A comprehensive and effective intervention process enables social workers to utilize high-quality tools and models to make child protection decisions (Graça et al., Citation2018).

Methodology

Study design and hypotheses

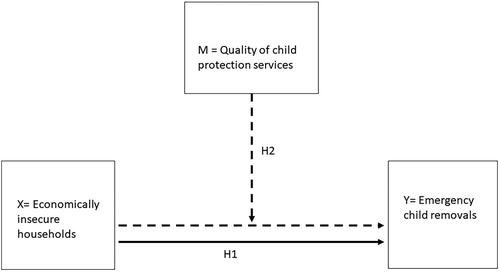

The rationale of this study is based on the notion that the municipality-level variation in emergency child removals can be explained by the level of quality of child protection services if also the number of economically insecure families is considered. First, the association between the number of economically insecure families and emergency child removals is studied across Finnish municipalities (N = 292). Economic insecurity is operationalized as the number of people receiving social assistance. It is hypothesized that when there is a greater number of people receiving social assistance in a municipality, there will also be a greater number of emergency child removals (Lotspeich et al., Citation2020; Walsh et al. Citation2019). Second, it is studied whether the higher quality of child protection services provides a positive buffer on the need for emergency child removals. A social worker should handle the needs assessment of a child welfare case within the statutory time-limit of 3 months. The needs assessment creates a basis for the services and interventions offered to the family. However, some municipalities have difficulties to follow the statutory time-limit, thus the proportion of completed needs assessment cases in the statutory time-limit varies between municipalities. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the proportion of completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit buffers the effect of economic insecurity on the demand for emergency child removals. More detailed hypotheses are:

H1: the more there are people who receiving social assistance in a municipality, the higher the rate of emergency child removals will be (: Arrow without dashed line),

H2: the association of social assistance receivers and emergency child removals depends on the proportion of completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit at the municipality level (: Arrows with dashed line).

Data and variables

The data were retrieved from the Sotkanet Indicator Bank, operated by the National Institute of Health and Welfare in Finland. Sotkanet Indicator Bank is an open data source from which can be searched for statistical information on the health and well-being of the population, and the functioning of the service system in Finland. The data were gathered from 292 municipalities during the period of 2017–2019 [Referred 15.06.2021]. For each indicator, the value was calculated based on a three-year average (). A two-year average was also accepted in cases where information from one year was missing. If only one year of information was available, this was marked as missing information.

Table 1. The list of variables.

The dependent variable, emergency child removals, indicates the proportion (%) of children aged 0–17 years who have been placed outside the family home as an emergency removal, during the year in the total population of the same age in a municipality (Indicator 1244). The distribution of the dependent variable was improved using a two-step normality transformation approach (Templeton, Citation2011), which can be used when utilizing data with a non-normal distribution to obtain a more accurate interpretation of the results (Templeton & Burney, Citation2017; cf. Rönkkö & Aguirre-Urreta, Citation2020).

Preventive social assistance for recipient households (Indicator 4014) was used as an independent variable. Preventive social assistance is discretionary financial support of last resort, which the municipality can grant after the client has applied for primary basic income support (i.e., basic social assistance). It indicates the number of families who have received preventive social assistance during the calendar year. As stated in the Social Assistance Act 1412/1997 (1997), social assistance is a last-resort financial assistance paid in order to ensure the livelihood of persons or families. Social assistance is aimed at ensuring the person or family has at least the minimal living amount needed for a life based on some degree of human dignity.

The indicator of the needs assessment for child welfare services (Indicators 3495 and 3497) shows the proportion (%) of completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit of three months. The data are gathered twice-yearly. The monitoring of the statutory processing times includes the handling of initiated child welfare cases (a child welfare notification, or information otherwise received, on a child in need of child welfare measures), and the needs assessment for a child requiring special support in accordance with section 36 of the Social Welfare Act (13.4.2007/417). There are large differences in the proportions of completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit among municipalities. In some municipalities it is only 55% of all cases, because in the majority of municipalities all cases are completed in the statutory time period of three months (Sotkanet Indicator Bank, Citation2020). In this sense, it is assumed that the proportion of completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit is an essential outcome indicator for the quality of child protection services, which consists of structural and process factors, such as caseload, number of personnel, supervisory oversight, work procedures etc.

The size of the child protection system and the number of child welfare notifications are treated as confounding variables. Notifications inform on the number of alerts involving children that have been made to child protection services to investigate. Municipalities differ according to their respective sizes, thus their child protection systems are also different. For controlling the different sizes of municipalities, the child protection systems are set in order from smallest to largest by reflecting the population of the respective municipalities. In , the smallest municipality receives a value of 1, and the largest receives 292. The municipality has an average of 29.77 people per 1,000 inhabitants.

Spearman’s rho (r) was used to explore associations between the factors. The hypotheses () was tested by using a conditional process/path analysis program, PROCESS (developed by Andrew F. Hayes), which utilizes ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. A review of the assumptions for regression analysis found that the linear relationship between the dependent variable and the explanatory variables showed no violations, residuals were normally distributed, and there was no interfering multicollinearity between the variables (variable inflation factors, VIF < 1.3). The Breusch-Pagan test describes the uniformity of variance of residual terms, but this did not yield an acceptable result; hence, the HC3 estimator was used for controlling heteroskedasticity (Cai & Hayes, Citation2008).

The PROCESS program utilizes the listwise deletion method, which causes problems in a missing information situation. The indicator for the dependent variable was available from 158 of 292 municipalities. Regarding the ethical security issues, the municipality-level information of emergency removals with less than 5 cases was deleted from the data by the controller. For handling the missing information, the proportion-based values were converted to numbers. It was known that the highest missing value cannot be greater than 4. Further, it was found that the smallest existing value was 3.1 (the mean for three years), which is less than 5. From this perspective, it was estimated that the highest missing value could not be greater than 3. Also, it was known that there is a strong correlation between municipality size and the number of emergency removals. In this sense, a simulation model was created to replace the missing information. For following the simulation pattern, the missing values of the dependent variable were imputed according to the size of a municipality, and by the fact that the highest value is not greater than 3. Further, several simulation models were conducted for imputation, but there were no essential differences among the simulation models. Nevertheless, the formation of the variable leaves room for criticism, that is, the variable does not fully describe the numbers of emergency removals, especially in the case of small municipalities. After the imputation procedure, there were no missing data in the dependent variables. From the independent variables, preventive social assistance had 8.56% missing information, and investigation of the need for welfare measures had 2.74% missing values. Confounding variables had no missing values. According to Little’s MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) test statistic, the data were not observed to be missing completely at random (Chi-Square = 239.886, DF = 15, Sig. = .000), which needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results of the study. All factors which defined the dependent variable were mean centered for the analyses.

Results

Descriptive analysis

According to the results of the correlation analysis () “emergency removals” correlates positively with “social assistance” (r = .756***). The proportion of the completed needs assessment cases is negatively correlated with emergency child removals, and it is also statistically significant (r = −0.192**). Further, correlation between outcome rate of the needs assessment and social assistance is negative but not statistically significant.

Table 2. Correlations between the variables (Spearman’s rho).

Moderation analysis

It was analyzed whether there is an association between social assistance receivers and emergency child removals and, further, whether the association is moderated by the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases. The size of the child protection system and the number of child welfare notifications were treated as confounding variables.

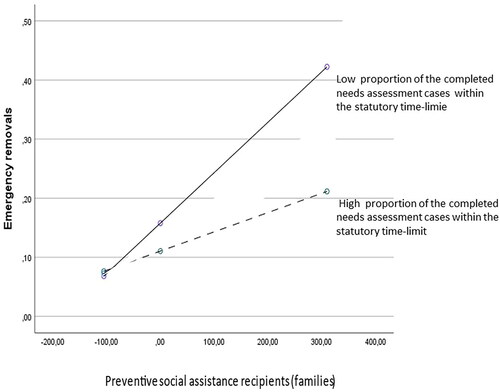

According to the moderation analysis, social assistance was positively associated with emergency child removals (b1 = .001***) () when other values were zero. Thus, Hypothesis 1 (H1) was supported. In the analysis, the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases was positive but not statistically significant. However, the interaction term was positive and statistically significant (b1 < .001**) (). It is noteworthy, that transforming the dependent variable to normal from the scale of 0–614.81 to the scale of −1.98 to 2.70 automatically affects the size of the coefficient in the interaction term (Templeton, Citation2011). In this sense, Hypothesis 2 (H2) was supported. The size of the child protection system was statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 3. Moderation analysis: emergency child removals as a dependent variable.

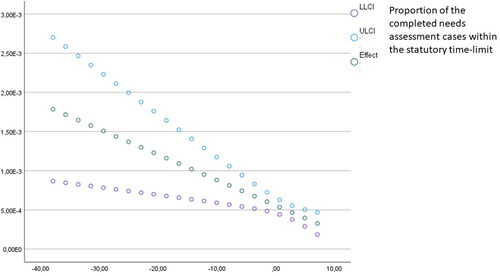

The interaction term () can be visualized so that the nature of moderation is clearer to understand (see ). The figure shows that when the number of social assistance recipients increases, so does the proportion of emergency child removals. However, the increase in emergency child removals is steeper in the case of municipalities with a low proportion of the completed needs assessment cases, compared to the municipalities with a high-level needs assessment rate. Further, the Johnson-Neyman technique was used to probe whether the conditional effect of social assistance receivers on emergency child removals was statistically significant in the distribution of the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases. It was found that the entire distribution of the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases was statistically significant (Appendix A).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to resolve two hypotheses (H1 and H2, respectively), which assume that economically insecure households are connected to emergency removals and that this connection is dependent on the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases in a municipality. The purpose of child protection is to provide support and help to families so that there is no need to place children out of their homes. However, a child’s removal from his/her home is necessary if the child’s best interests cannot be secured otherwise. In this sense, the child removals intervention is a key part of child protection measures (Berrick et al., Citation2016; Isokuortti et al., Citation2020). In addition, emergency child removals are special cases of child protection, so that the intervention decision is often rapidly made, and cannot be predicted, when there is a need to quickly intervene for securing the child’s living condition. Emergency removals are not desired by the child protection system because they indicate that preventive social services and child protection services did not reach families in sufficient time or in the proper way (Graça et al., Citation2018: Lamponen et al., Citation2019). However, emergency child removals are also necessary and justified solutions that may be required to resolve the challenging situation for protecting the best interest of the child.

The need for child protection is found to be associated with socio-economic challenges in families (Raissian & Bullinger, Citation2017; Bywaters et al., Citation2018; Walsh et al., Citation2019; Lotspeich et al., Citation2020; Schneider et al., Citation2022). From this perspective, in the present study, it was assumed that the municipalities with a higher number of social assistance families would also have the most emergency removals. According to the results of this study, the more families there are in a municipality living in economically insecure situations, the more there is also the need for emergency child removals. However, poverty is a multi-level and complex issue, which is related to several other social risks (for instance, a low level of education, or a difficult labor market situation, etc.) but also to personal problems (for instance, mental health and substance abuse). From this perspective, the results should not be interpreted too unilaterally (cf. Hiilamo, Citation2009; Mulder et al., Citation2018). Poverty itself may not be the focal predictor of the need for emergency child removals, but it can be interpreted as a kind of binder factor between different social risks and personal problems.

The main task of the study was to emphasize the quality of the child welfare system by examining whether the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases is associated with the proportion of emergency child removals. The study demonstrates that when the number of families with economic insecurity increases, so does the need for emergency removals. But, in well-functioning child protection systems it increases less than in those municipalities that are unable to carry out the need assessments within the statutory time-period. In this sense, the quality level of child protection services is an essential factor in the need for emergency child removals. It has also been found in previous studies that supporting families at an early stage with high-quality and faster available services prevent families’ situations from escalating to the point where emergency measures can no longer be avoided (e.g., Huntington, Citation2014; Storhaug & Kojan, Citation2017). In turn, the limited resources of social workers have been found to affect the employees’ opportunities to provide effective services for families at risk (Hope & Van Wyk, Citation2018). If a municipality’s social workers cannot complete the needs assessments in the statutory time-period, it indicates that there are insufficient resources in child protection, whereby the case load can be too large or available social workers can be low in number.

The strength of this study is that it covers almost every municipality in Finland, and in that way the results can be generalized to all of Finland. However, there are also several uncertainties associated with this research design and the results. It may be questioned whether the quality of services could be operationalized only to the proportion of the completed needs assessment cases within the statutory time-limit. Also, the ratio of caseload and staff availability is an essential factor that affects the quality of services, but the available data did not reach these factors. Further, the quality of services is related to the skills and training of the staff, to the clear procedures for the child protection process, and more broadly to the culture of child protection services. Furthermore, the indicator for the quality of services does not consider the intensity of other child welfare services in a particular municipality (cf. Alastalo & Pösö, Citation2014). In this sense, it is possible that in some municipalities other social services may compensate the insufficiencies in the needs assessment process. On the other hand, if a municipality reaches the statutory time-period on the needs assessment for child welfare, the indicator does not uncover whether there are some insufficiencies in some other child welfare services.

Also, the indicators used in the study measure issues that are not necessarily stable from one year to the next, especially in small municipalities, which means that indicators are sensitive to change, although efforts have been made to control this by averaging the indicators over a 2- to 3-year period. It is noteworthy that the study is focused only on the system level, which ignores the individual level factors, although the previous studies (such as Brennan, Citation2020; Jennings, Citation2019; Cesar & Decker, Citation2020) have shown that individual and family-related factors are essential for emergency child removals. Hence, the design of the present study leaves room for criticism from the individual-level perspective, so the results should also be treated with caution from this perspective. For the future, it is recommended that more research is needed so that several social risk factors such as low income and education levels, and personal problems such as substance abuse and mental health problems can be considered at both the individual and systems levels.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that emergency child removals are associated with families’ economic insecurity. In this sense, the study is consistent with the previous studies which have underlined that the socio-economic issues, such as families’ economic insecurity, should be a key driver for community-level social policy initiatives, strategies, and programs for improving and developing child protection services (McLeigh et al., Citation2018; Austin et al., Citation2020).

The main message of the study is that the quality level of child protection services seems to be an essential factor in the demand for child protection services. The study also highlights that the proportion of emergency child removals is higher in the municipalities that have difficulties to manage their services in a proper way. If a municipality cannot complete the needs assessments process in the statutory time-period of three months, it may indicate also more broader quality-related difficulties in child welfare services such as, for instance, insufficient caseload and staff ratio, or unclear instructions and procedures for the child protection process. Consequently, the study encourages the managers of child protection services to work intensively on any quality level issues for improving responses to the needs of service users.

Finally, the results of the study suggest also that individual and family problems alone are not the reasons for emergency child removals. Rather, the weaknesses in the child protection system itself may create the need for them. The need for child protection is a complex issue that should be approached at an individual level, but the system level effect should not be forgotten. This is our important societal message for politicians who allocate resources for child welfare and preventive social services. However, more research is needed to evaluate practice models so that the effectiveness of child protection can be demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Finland) for the research project (grant reference VN/13990/2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alastalo, M., & Pösö, T. (2014). Number of children placed outside the home as an indicator–Social and moral implications of commensuration. Social Policy & Administration, 48(7), 721–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12073

- Austin, A. E., Lesak, A. M., & Shanahan, M. E. (2020). Risk and protective factors for child maltreatment: A review. Current Epidemiology Reports, 7(4), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-020-00252-3

- Authors. (2022).

- Authors. (2023).

- Berrick, J., Dickens, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2016). Time, institutional support, and quality of decision making in child protection: A cross-country analysis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(5), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2016.1159637

- Bilson, A., & Martin, K. (2016). Referrals and child protection in England: One in five children referred to children’s services and one in nineteen investigated before the age of five. British Journal of Social Work, 47(3), bcw054. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw054

- Brennan, J. (2020). Emergency removals without a court order: Using the language of emergency to duck due process. Journal of Law and Policy, 29(1), 121–157.

- Bullinger, L. R., & Boy, A. (2023). Association of expanded child tax credit payments with child abuse and neglect emergency department visits. JAMA Network Open, 6(2), e2255639–e2255639. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55639

- Bywaters, P., Brady, G., Bunting, L., Daniel, B., Featherstone, B., Jones, C., Morris, K., Scourfield, J., Sparks, T., & Webb, C. (2018). Inequalities in English child protection practice under austerity: A universal challenge? Child & Family Social Work, 23(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12383

- Bywaters, P., Scourfield, J., Jones, C., Sparks, T., Elliott, M., Hooper, J., McCartan, C., Shapira, M., Bunting, L., & Daniel, B. (2020). Child welfare inequalities in the four nations of the UK. Journal of Social Work, 20(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318793479

- Cai, L., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). A new test of linear hypotheses in OLS regression under heteroscedasticity of unknown form. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 33(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998607302628

- Campbell, S M., Roland, M. O., & Buetow, S. A. (2000). Defining quality of care. Social science & medicine, 51(11), 1611–1625.

- Carter, Y., Bannon, M. J., Limbert, C., Docherty, A., & Barlow, J. (2006). Improving child protection: A systematic review of training and procedural interventions. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91(9), 740–743. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.092007

- Cesar, G. T., & Decker, S. H. (2020). “CPS sucks, but… I think I’m better off in the system:” Family, social support, & arts-based mentorship in child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105388

- Child Welfare Act, 417/2007. (2007). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland.

- Cleland, J., Hutchinson, C., Khadka, J., Milte, R., & Ratcliffe, J. (2021). What defines quality of care for older people in aged care? A comprehensive literature review. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 21(9), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14231

- Clément, M. È., Bérubé, A., & Chamberland, C. (2016). Prevalence and risk factors of child neglect in the general population. Public Health, 138(September), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.018

- Conrad-Hiebner, A., & Byram, E. (2020). The temporal impact of economic insecurity on child maltreatment: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(1), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018756122

- Cooper, K., & Stewart, K. (2013). Does money affect children’s outcomes? A systematic review. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Davidson-Arad, P., Englechin-Segal, D., Wozner, Y., & Arieli, R. (2005). Social workers’ decisions on removal. Journal of Social Service Research, 31(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v31n04_01

- De Smidt, G. A., & Gorey, K. M. (1997). Unpublished social work research: Systematic replication of a recent meta-analysis of published intervention effectiveness research. Social Work Research, 21(1), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/21.1.58

- Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA, 260(12), 1743–1748. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

- Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2014). Boosting family income to promote child development. The Future of Children, 24(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2014.0008

- Eckenrode, J., Smith, E. G., McCarthy, M. E., & Dineen, M. (2014). Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics, 133(3), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1707

- Fallon, B., Ma, J., Black, T., & Wekerle, C. (2011). Characteristics of young parents investigated and opened for ongoing services in child welfare. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(4), 365–381. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9342-5

- Garcia, A., Puckett, A., Ezell, M., Pecora, P. J., Tanoury, T., & Rodriguez, W. (2014). Three models of collaborative child protection: What is their influence on short stays in foster care? Child & Family Social Work, 19(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00890.x

- Gillingham, P. (2018). Evaluation of practice frameworks for social work with children and families: Exploring the challenges. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 12(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2017.1392391

- Gorey, K. M. (1996). Effectiveness of social work intervention research: Internal versus external evaluations. Social Work Research, 20(2), 119–128.

- Graça, J., Calheiros, M. M., Patrício, J. N., & Magalhães, E. V. (2018). Emergency residential care settings: A model for service assessment and design. Evaluation and Program Planning, 66(February), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.10.008

- Hiilamo, H. (2009). What could explain the dramatic rise in out-of-home placement in Finland in the 1990 and early 2000? Children and Youth Services Review, 31(2), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.07.022

- Hope, J., & Van Wyk, C. (2018). Intervention strategies used by social workers in emergency child protection. Social Work, 54(4), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.15270/54-4-670

- Horwitz, S. M., Hurlburt, M. S., Cohen, S. D., Zhang, J., & Landsverk, J. (2011). Predictors of placement for children who initially remained in their homes after an investigation for abuse or neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(3), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.002

- Hunter, A. A., & Flores, G. (2021). Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: A systematic review. Pediatric Research, 89(2), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01175-x

- Huntington, C. (2014). The child-welfare system and the limits of determinacy. Law and Contemporary Problems, 77(1), 221–248.

- Isokuortti, N., Aaltio, E., Laajasalo, T., & Barlow, J. (2020). Effectiveness of child protection practice models: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108(October), 104632–104632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104632

- Jaakola, A.-M. (2020). Lapsen tilanteen arviointi lastensuojelun sosiaalityössä. Kuopio: Itä-Suomen yliopisto. [Assessment of a Child’s Circumstances in Child Welfare Social Work]. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland: Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies; 229.

- Jennings, W. (2019). Separating families without due process: Hidden child removals closer to home. City University of New York Law Review, 22(1), 1–40.

- Lamponen, T., Pösö, T., & Burns, K. (2019). Children in immediate danger: Emergency removals in Finnish and Irish child protection. Child & Family Social Work, 24(4), 486–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12628

- Lotspeich, S. C., Jarrett, R. T., Epstein, R. A., Shaffer, A. M., Gracey, K., Cull, M. J., & Raman, R. (2020). Incidence and neighborhood-level determinants of child welfare involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 109, 104767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104767

- Malley, J., & Fernández, J. L. (2010). Measuring quality in social care services: Theory and practice. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 81(4), 559–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2010.00422.x

- McLeigh, J. D., McDonell, J. R., & Lavenda, O. (2018). Neighborhood poverty and child abuse and neglect: The mediating role of social cohesion. Children and Youth Services Review, 93(October), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.018

- Mulder, T. M., Kuiper, K. C., van der Put, C. E., Stams, G. J. J., & Assink, M. (2018). Risk factors for child neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.006

- Mullen, E. J., & Shuluk, J. (2011). Outcomes of social work intervention in the context of evidence-based practice. Journal of Social Work, 11(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310381309

- Pelton, L. H. (2008). An examination of the reasons for child removal in Clark County, Nevada. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(7), 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.007

- Qualification Requirements for Social Welfare Professionals Act 272/2005. (2005). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

- Raissian, K. M., & Bullinger, R. L. (2017). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72(January), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.033

- Räty, T. (2019). Lastensuojelulaki: Käytäntö ja soveltaminen [Child Welfare Act: Practice and application]. Edita.

- Rönkkö, M., & Aguirre-Urreta, M. I. (2020). Cautionary note on the two-step transformation to normality. Journal of Information Systems, 34(1), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.2308/isys-52255

- Saar-Heiman, Y., & Gupta, A. (2020). The poverty-aware paradigm for child protection: A critical framework for policy and practice. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(4), 1167–1184. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz093

- Schneider, W., Bullinger, L. R., & Raissian, K. M. (2022). How does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment and parenting behaviors? An analysis of the mechanisms. Review of Economics of the Household, 20(4), 1119–1154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09590-7

- Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Peta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., & Li, S. (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4). US Department of Health and Human Services. 9.

- Social Assistance Act 1412/1997. (1997). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

- Social Welfare Act 1301/2014. (2014). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

- Sotkanet Indicator Bank. (2020). Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare.

- Statistics Report (Tilastoraportti in Finnish language) 28/2022. (2022). Helsinki; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Tilastoraportti; Lastensuojelun käsittelyajat 1.10.2021–31.3.2022 (julkari.fi)

- Stolt, R., Blomqvist, P., & Winblad, U. (2011). Privatization of social services: Quality differences in Swedish elderly care. Social Science & Medicine, 72(4), 560–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.012

- Storhaug, A. S., & Kojan, B. H. (2017). Emergency out-of-home placements in Norway: Parents’ experiences. Child & Family Social Work, 22(4), 1407–1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12359

- Templeton, G. F. (2011). A two-step approach for transforming continuous variables to normal: Implications and recommendations for is research. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02804

- Templeton, G. F., & Burney, L. L. (2017). Using a two-step transformation to address non-normality from a business value of information technology perspective. Journal of Information Systems, 31 (2),149–164. https://doi.org/10.2308/isys-51510

- Trocmé, N., Kyte, A., Sinha, V., & Fallon, B. (2014). Urgent protection versus chronic need: Clarifying the dual mandate of child welfare services across Canada. Social Sciences, 3(3), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3030483

- Walsh, D., McCartney, G., Smith, M., & Armour, G. (2019). Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(12), 1087–1093. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212738

- Yang, M. Y. (2015). The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 41(March), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.009