Abstract

The idea of events being opposed to everyday life is widely reflected in events literature. Events are generally characterized as being ‘out of the ordinary’. This paper explores the creation and performance of the extraordinary, as well as the spills over of the extraordinary into everyday life. Using ethnographic methods, such as participant observation and interviews, the social practices of the fantasy event ‘Elfia’ were studied. The results show how the participants, both in everyday life and during the event, actively create and maintain the extraordinary via meanings, materials and competences. But instead of being completely out of the ordinary, the event provides a temporary re-arrangement of status and social order. This paper challenges the dominant narrative about events as extraordinary spaces of freedom and escapism. Instead, the extraordinary turns out to be interwoven with everyday life.

Introduction

Events have often been described as ‘out of the ordinary’ spaces, away from everyday life (Falassi, Citation1987; Goldblatt, Citation2011) ‘in which intense extraordinary experiences can be created and shared’ (Morgan, Citation2008:91). The extraordinary dimension of events contributes to their social value because it allows people to explore different aspects of who they are or can be (Ronström, Citation2011). However, the extraordinary is also socially constructed; it relies on the event participants to perform the practices through which the extraordinary comes to existence. This paper explores the creation of the extraordinary, by focusing on the social practices through which the extraordinary is constructed and performed.

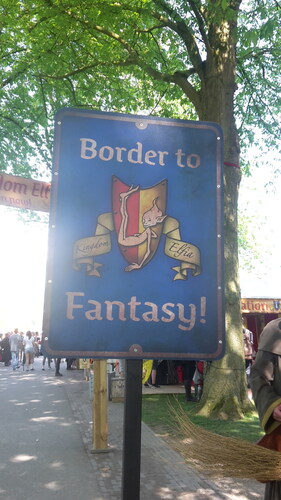

This study presents the case of the fantasy event Elfia in the Netherlands. Elfia brings together a wide range of people involved in cosplay and fantasy, under the slogan: ‘You will never dream alone’. Elfia is an outdoor fantasy event that takes place twice a year in the Netherlands at two different locations: in April in the park of Castle De Haar in Haarzuilens and in September in the Castle gardens in Arcen. The first edition of the event took place in 2001 when it was called Elf Fantasy Fair. In 2013 the name was changed to (the Kingdom of) Elfia. With the change in name, the emphasis was placed on the idea of a mythical kingdom that could be physically entered, by crossing a border from reality to fantasy (see ). Moreover, the name change intended to include a greater diversity of visitors, including families. Elfia now brings together a great diversity of people interested in fantasy and cosplay, ranging from Disney to horror, sci-fi, and mythology.

Elfia has become a space for performing the extraordinary, which becomes a reality of its own, with its own logic, in which the different characters mingle and interact with each other. Studying the social practices of Elfia gives insights into the collective construction of a temporary out-of-the-ordinary reality. This study fills a gap in existing events research, because it challenges the extraordinary as something existing in itself, and as a largely unquestioned goal of events. By presenting the extraordinary as created and performed by the event participants, it becomes intertwined with the everyday life of the participants. Moreover, it challenges and refines some of the dominant narratives of events as extraordinary places of freedom and escapism. Therefore, the research questions of this paper are (1) Through which practices is the mythical world of Elfia created and performed? (2) How does the extraordinary of the event spill over into everyday life and vice versa?

Literature review

The idea of events being opposed to everyday life is widely reflected in the events literature. Events are generally characterized as being ‘out of the ordinary’ (Falassi, Citation1987; Getz, Citation1989; Goldblatt, Citation2011; Jago & Shaw, Citation1998, Morgan, Citation2008). Because events are limited in time and space, they are usually defined as separate from everyday life, and therefore characterized as the opposite of everyday life. Getz (Citation2008) states that people expect and anticipate that an event will be out of the ordinary. Ronström (Citation2011) describes festivals as a ‘time out’ from ordinary everyday life in mainstream society. Seeing events as a time out, or an escape from everyday life has the advantage that we can study events as spaces in which new things can be tried out (Ronström, Citation2011) and people can learn and experiment.

One of the reasons for labeling events as the opposite of everyday life, or out of the ordinary (De Geus, Richards and Toepoel, 2016) is the fact that events have often been depicted as ritualistic. Based on the work of Van Gennep (1960/Citation2010 2011), and Turner (Citation1967; Citation1979), events are described as liminal spaces, which are situated outside ordinary life, and which remove participants from their daily routines. Instead the participants enter an in-between state of liminality, exploration, and new possibilities (Rihova et al., Citation2015; Sterchele & Saint-Blancat, Citation2015; StJohn, Citation2017; Turner, Citation1995). As Durkheim’s classic work on rituals describes, bodily co-presence and interaction of large groups can lead to a collective feeling of togetherness, described as collective effervescence (Durkheim, 1912). In Durkheim’s (Citation1912) study on religious rituals, collective effervescence is created through performing a range of specific practices, designed to fill the practitioners with emotional energy. These rituals maintain a distance between the sacred and the profane (Durkheim, 1912). Therefore, seeing events as ritualistic and adding ritualistic elements to events, gives them an exceptional atmosphere.

Framing events as extraordinary and as an escape from everyday life is also embedded in a tradition of framing tourism practices as out of the ordinary (Larsen, Citation2008; MacCannell, Citation1999; Urry, Citation1990). However, in tourism studies, this dichotomy has been challenged by the ‘performance turn’. Goffman’s (Citation1959) classic work ‘The presentation of the self in everyday life’ forms the basis of the performance turn. Goffman uses a dramaturgical approach to describe social processes in everyday life. In his performance metaphor, people are always simultaneously actors and audience, acting and judging other performances using costumes, props and manner. Goffman (Citation1959) makes a distinction between front stage settings, in which people present their identities in public and manage impressions, and backstage settings, which are not part of the public performance and where the performer can relax. Goffman’s (Citation1959) performance metaphor has become an established approach for analyzing tourism practices (Cohen & Cohen, Citation2012; Edensor, Citation2001; Larsen & Urry, Citation2011, Wilson & Moore, Citation2018; MacCannell, Citation1973; Citation1999). This has changed the way of thinking about tourism as being out of the ordinary (Larsen, Citation2008), because, instead of a way to escape everyday life, tourism becomes a way of performing it.

The performance metaphor has also been used in event studies (Platt, Citation2011). Events have been studied as stages for performing place (Giovanardi et al., Citation2014; Platt, Citation2011) and identities (Jaimangal-Jones et al., Citation2015). As Goffman argues, performances, although regulated, are not predetermined. People alter their performances according to the setting. Especially leisure settings such as events allow visitors to be creative and explore different parts of their identities (Jaimangal-Jones et al., Citation2015; Ronström, Citation2011). Still, the idea of events as out of the ordinary and separate from everyday life, remains largely unchallenged. The performance turn argues that instead of taking a break from everyday life, attendees use events to perform it. This provides a different perspective in which events are no longer seen and studied as isolated from their contexts, opening up avenues for exploring the connections and links between the extraordinary of the event and the everyday of the participants.

According to Larsen and Urry (Citation2011), there is no performance without doing. They characterize tourism as a doing, consisting of embodied practices. One way to analyze practices is by adopting a practice approach. Although there is not one standardized practice approach, but many different approaches, all practice theorists agree on taking the practice as a starting point for analysis. Moreover, they deal with the interconnected ‘sayings and doings’ (Lamers et al., Citation2017; Nicolini, Citation2012) of a situation. Founded on Giddens’ structuration theory, practice theory avoids the dualism of structure and agency. It is therefore very suitable for bridging domains that are generally dealt with separately (James et al., Citation2018), such as, in this case, the domains of the extraordinary and everyday life. Practice approaches have not been applied much in tourism and event studies until recently, because they have generally been used to analyze routine behavior (Bargeman & van der Poel, Citation2006) and everyday life. However, there is a growing interest in analyzing practices in order to capture the blended and hybrid nature of many tourism and leisure contexts (James et al., Citation2018; Simons, Citation2019).

This study applies an approach that focusses on the different elements that make up a practice as well as the connections between different practices. This is helpful for analyzing the sayings and doings of the creation and performance of the extraordinary. Therefore, this study follows the practice approach as described by Shove et al. (Citation2012). In their perspective, practices are built from three interconnected elements: materials, competence and meanings. Shove et al. (Citation2012) describe how on the one hand, practices are entities that attract practitioners through their meanings, and on the other hand how practices are performed. Practices as entities can only exist if they are performed regularly, because through the performance, the connections between materials, meanings and competences are made and reaffirmed. Although practices can be studied separately, they are linked together (Lamers et al., Citation2017; Shove et al., Citation2012). The connection between practices can be helpful in explaining how the extraordinary is socially constructed through different types of practices, and how these practices combine the extraordinary with everyday life.

The case under study in this paper is the fantasy event Elfia. Elfia involves cosplay, as the performing of a fantasy character is called. Cosplay is a combination of the words ‘costume’ and ‘play’ (Crawford & Hancock, Citation2019; Lamerichs, Citation2011). Cosplay is generally framed as the opposite of everyday life and as an escape from the mundane, as participants ‘can momentarily leave behind their stresses, burdens, anxieties, boredom, and the disappointments of everyday life and enter into a fantasy environment.’ (Rahman et al., Citation2012, p. 333) This frames the practitioners of these practices as having a very disappointing daily life. Moreover, the dichotomy of events versus everyday life is taken to an extreme. It suggests that people are temporarily taking on a different role, and then return to their ‘real’ everyday identity. Although this is too simplistic, the fact that people are performing or imitating (Gn, Citation2011) a different role is key to cosplay.

Goffman’s performance metaphor is very applicable to cosplay, and it has been used by several scholars, such as Rahman et al. (Citation2012), Peirson-Smith (Citation2013) and Crawford and Hancock (Citation2019). When applying the performance metaphor to cosplay, it would be too simple to portray cosplay as a front stage activity that temporarily replaces the real identity behind it. Instead, the performance metaphor can show us that cosplay is a front stage activity that is part of the real identity of the participants (Crawford & Hancock, Citation2019).

Instead of escaping or taking a break from daily life, cosplay can be seen as a playful performance of identity and the seeking of new stages to perform one’s identity. This also explains why cosplayers often perform a range of different roles; they use cosplay as a setting to explore and develop aspects of their identities (Crawford & Hancock, Citation2019). Crawford and Hancock (Citation2019) use Goffman’s terms of ‘role embracement’ and ‘role distance’ to explain how cosplay allows the participants to distance themselves from certain roles they have in society. This should not be confused with escapism, because it is not a denial of existing identities, but a part of identity construction.

Another implication of nuancing the escapism motive for cosplay, is the intertwinement of cosplay with the everyday life of the participants. As Lamerichs (Citation2010) also states in her ethnographic study about cosplay as a subculture, cosplay is connected to other (fan) practices, which are situated in everyday life. Moreover, Crawford and Hancock (Citation2019) argue that cosplay should be seen and situated in the everyday online and offline lives of the participants, and not just as an activity that takes place during events. The event can then be seen as a ‘home’ (Lamerichs, Citation2014) for many cosplayers, which puts the focus back on the significance of place, but the choice of the word ‘home’, is also very much part of everyday life discourse.

As Shove et al. (Citation2012) indicate, practices are related, either in tight bundles or in looser connections. The practices that create the extraordinary are situated at the event and outside the event, offline and online (Simons, Citation2019). A detailed analysis of these practices will provide a different perspective on the idea of events as extraordinary, nuancing the escapism label, and opening up avenues for defining the social value of events as part of the everyday life of the attendees.

In conclusion, labeling events in general as being out of the ordinary, is a limited approach. There is an increasing awareness in tourism and leisure studies that everyday life and the extraordinary are interwoven via practices. This insight has not yet been extended to the study of events, which are usually defined as being situated in the extraordinary realm. By studying the practices through which the extraordinary is created and performed, insights can be gained into the extraordinary dimension of events and how this is interwoven with everyday life. This will increase our understanding of the social value of events.

Methods

This paper presents the case of Elfia as an information rich case regarding the performance of the extraordinary. Elfia is the largest fantasy event in Europe and it draws an international audience.

Using ethnographic methods, the social practices during and around the event were studied.

Participant observation took place during the 2016, 2017 and 2018 editions of the event (six editions in total). The researcher participated in the event for the full two days. The first day, the researcher participated individually, in a modest costume which allowed blending in without drawing to much attention. By observing, participating and having informal conversations, the data were gathered resulting in a condensed account. After the event, an extended account was written including a thick description of the event practices and a photographic record. Every second day of the event, the researcher participated in a different group setting, either in a duo, in a small group, or with a family. This led to taking different routes through the event and to participating in different activities and interactions, adding to the richness of observations and the fieldnotes. The precise focus of the observations changed over time. The first observations were very open, as a first-time visitor of the event. This gradually changed into a more specific focus on the meanings, materials and competences (Shove et al., Citation2012) of the practices and the way the different practices were performed. To increase the trustworthiness of the observations, a team of research assistants were involved, who used an observation scheme based on Spradley’s (Citation1980) dimensions of social situations. The fieldnotes by the research assistants were not used in the final analysis, but they were used to ensure the credibility of the data.

Twenty interviews were conducted with informants who were purposefully selected (Patton, Citation2002) based on their different positions within the event practices. The informants varied in age, event related experience, and the characters they embodied during the event. Most informants were interviewed face-to-face in their homes or in a neutral place like a coffee bar. Two interviews took place via Skype. The interviews took 1 − 2.5 hours and they included topics about practices related to the event, the meanings of the event, their performance and interactions during the event, implicit and explicit rules, and more items. Some informants used photographs to illustrate the information they shared, others showed their costumes and creative workplaces. All informants gave consent to use the interview data anonymously. If the anonymity could not be guaranteed, the informants were contacted for approval.

The data were analyzed using the qualitative data analysis program MAXQDA. A first layer of coding was based on the elements of practices (Shove et al., Citation2012), a second and third layer of coding emerged from the data and involved themes like escapism, status and creativity.

Results and discussion

A mythical world

Elfia takes place in the gardens of a castle. During the event, the castle grounds are called ‘Kingdom of Elfia. Most informants also describe Elfia as a mythical world that they can physically enter. Some of the informants also refer to the event as a kingdom, with ‘inhabitants’ instead of visitors. The idea of an extraordinary world is underlined by creating a physical border that the attendees must cross in order to enter the Kingdom of Elfia. This border symbolizes the distinction between the extraordinary of the event and the reality of everyday life (see ). Additionally, the participants obtain an Elfia passport, which they can have stamped with a different stamp for every edition.

As described by the informants, Elfia is a mythical Kingdom that appears twice a year for a few days. However, this mythical kingdom is highly dependent on the performances of the participants. To become part of this mythical world, the participants must engage in several practices, that take place outside the setting of the event, in their everyday lives.

Creating the character: ‘blood, sweat and fire burns’

Firstly, in order to become a part of the mythical kingdom of Elfia, the participants need a costume. Most informants make their own costumes. Creating a costume generally takes place in people’s homes (see ) and it takes much time and effort. This practice can start half a year before the event. It involves choosing fabric, trying different techniques, watching YouTube clips, asking tips online, and so on. ‘Well, when you want to make a costume, and you need ideas, well, then you need to start at least half a year before’. (informant 2)

The informants put much time and effort into making a costume, and these activities can also have consequences for everyday life, as described by one of the informants who needed to replace her dining table.

‘I bought this table for our room to work. The other table was too small for the fabric’. (informant 2). Furthermore, the making of the costumes requires certain competences that the participants do not always possess.

‘I had to learn four new skills, middle ages chainmail and scale mail, sewing and working with thermo plastic …really … there are about 700 hours of work in this costume, I think.’ (informant 1)

‘People made these costumes really with blood sweat and burns. Especially fire burns, from the glue and the thermo plastic.’ (informant 1)

The costumes are not just perceived as costumes, but they allow the participants to transform into a different fantasy person or mythical character. This is illustrated by the way the informants talk about their costumes: ‘I have two characters. One is a small white dragon, and she is just childish, yes, a toddler, just doing her thing. The other one can be a bit grumpy, but she is also really tough.’ (informant 7)

This also explains why even when participants buy rather than make their own costumes, they can still be very busy preparing for their performance at the event. They are studying how to perform their character.

‘I also to go to Disneyland Paris a lot … there I meet the characters … I learn from them, I watch how they do it, and what shoes they wear in Disney.’ (informant 15)

The creation of a character can be seen as a backstage practice, which takes place in people’s own homes. It shows how meanings, materials and competences (Shove et al., Citation2012) are combined. The costume is created in such a way that it fits the mythical meanings of Elfia, which makes the participant an inhabitant of this kingdom and at the same time co-creator of the meanings of the event. The competences needed to create a costume are also obtained in the participant’s everyday life.

Once the costume is created, the participants need to become the character. The informants describe how, on the day of the event, changing into character starts at home, early in the morning. This process can take a while and it requires help, making it a (backstage) social practice in itself:

‘Last time, we were here at eight in the morning. Then you start with the make-up, the hair, the curls of course. That takes about an hour or two before all that is finished.’ (informant 4)

After changing into the character, the participants are ready to become an inhabitant of Elfia. However, for a while, they are still at home, or traveling to the event, so they are an extraordinary character in everyday life. This is an in-between phase, in which the ordinary and the extraordinary are mixed instead of neatly separated. Traveling to the event in character can lead to a mismatch in meanings, as described by one of the informants:

‘last year, I wore this renaissance-like dress. And that was a challenge, because of course, the skirt was really long. And then I laid down in the train. So, I had quite an audience, haha’. (informant 12)

Another mismatch of meanings involves the weapons that some of the characters carry, which make sense in the context of the event, but which are not allowed on the streets outside the event. The conflicting meanings of the practice and the everyday world can cause difficulties and it requires specific legal knowledge from the participants who want to travel with a sword to the event. ‘You can have a sword at home, according to the (Dutch) arms law. You just cannot carry it on the street … and it should not be within easy reach, and by that they mean three ways of securing it. Three actions before you can use it. I have a roof box, two separate keys and a box, those are three ways of securing it.’ (informant 11)

Not all participants travel to the event fully dressed in their costumes. Many visitors prepare their transformation into character at home and finish it in the parking lot of the event. As a result, the parking lot functions as a large backstage area of the event (see ), where people arrive in different stages of customization, and fully transform into the character they will embody that day. ‘We always get up early, to do the make-up at home. Then the dress goes in the trunk, together with the rest. When we arrive at the parking lot, we start to dress up and change, and then we enter’. (informant 10)

Although the participants have changed into character at home or at the parking lot, the real performance only starts after entering the event by literally crossing the border to the Kingdom of Elfia. The purpose of the border is clear to the informants, this is where the extraordinary starts, this is where you have changed into an inhabitant of the Kingdom of Elfia. ‘And at that moment, the moment you cross the border … the moment your ticket is scanned, you walk in there, well, and then you just go. Then you just go! (informant 4)

Performing in character: how ordinary practices become extraordinary

After crossing the ‘border to fantasy’, the participants actively start performing in character and co-creating the extraordinary. This is the moment when the characters come alive and when the costumes are shown. Some informants put more emphasis on the costumes in the way they describe the event, using words like ‘exhibition’. Others put more emphasis on the performance and use the word ‘theater’ to explain what they are doing. Both words emphasize the front stage character of the practice.

By crossing the border into Elfia, participants enter a place outside their everyday life. Instead of calling it an event, many informants also refer to Elfia as a place. Some informants literally emphasize the ‘break from everyday life’ very much in line with how Ronström (Citation2011) describes events as a time out. Others underline the freedom they experience at this place.

‘I think it is for everyone who enjoys taking a break from normal life, so to say, and step into another place, where everything is a bit different, and where you can feel a bit different too.’ (informant 10)

‘Where you have the freedom to be who you want to be’ (informant 1).

When asked to describe what they do after entering the Kingdom of Elfia, the informants describe many of the event practices as similar to everyday life, instead of extraordinary, such as walking around, greeting people, chatting, buying something at the market, eating and drinking. But because these ordinary activities become part of the performance in character, a new meaning is attached to them and they become extraordinary (see ). The informants describe how wearing the costume and role-playing makes them feel and act differently when engaging in ‘ordinary’ practices.

‘You start to behave differently, in the sense that you walk straighter, more majestic, and when people pass, a lady or a gentleman, you take your hat off’ (informant 3)

‘As soon as you put on a mask, you can do things, like tap someone on the shoulder, or something. But when you do that in real life, it is just annoying, but when they see a fluffy cartoon character approach them, it is just funny and nice.’ (informant 7)

‘When I wear the costume and I put on my helmet, no one can see me, but I can see everyone, that is the funniest thing. I don’t know, I feel quite invincible like that’ (informant 17)

Performing in character is not always an easy task. Some of the costumes can be very heavy and warm, and the performance can be physically demanding. Therefore, the practitioners develop strategies such as wearing the costumes for half a day or wearing different costumes during the two days of the event.

We usually alternate. Mostly, in the mornings we go in regular clothes. Then we look at the stalls and we walk around and have lunch. And when it gets busy, in the afternoon, then we decide to change into our costumes. Sometimes we walk around in costume for five hours, sometimes two… they are extremely hot!’ (informant 18)

There are some unspoken rules about how to perform in character. Some informants indicate that they try to stay in their role at all costs.

‘You do not take off your mask…that is called “ruining the magic” … When I eat, I go and sit somewhere in the back …not within sight …then I eat and relax and a bit later I walk around again’. (informant 7)

Others indicate that the character dictates what is allowed. Some characters can take off their helmet and others can’t.

‘It depends on the costume, I guess … Stormtroopers never take off their helmets… they are all clones so if everyone would take off their helmets it would look a bit strange …but because I am a fantasy character, I can take off my helmet. Children really like that, and if they are not super wild, I let them wear my helmet.’ (informant 17)

Although the event is described as a place of freedom, these descriptions show that the performances are surrounded by shared codes and expectations. This is also how Crawford and Hancock (Citation2019) describe cosplay. Even though people can deviate somewhat from the social conventions, they stay within the boundaries of their expected roles.

What is expected of the role, depends on the costume. The more impressive the costume, the more the participant becomes the focus of attention during the event. ‘If you have a really large costume, then people want a lot from you. They want to take a picture with you, they want to take pictures of you, and then you have to, you have to participate really actively. (informant 6)

Photographing: a social practice and a means for online performance

At Elfia there are many professional and amateur photographers taking pictures of the participants in costumes (see ). Photographing can be seen as a social practice that evokes active performances (Larsen, Citation2005; Noy, Citation2014; Scarles, Citation2012). The more impressive the costume, the more the character is photographed. ‘I really love it. Because I love, well, the attention, that sounds a bit strange, but, haha, I like it that they really want to photograph you, while normally you do not find yourself that pretty. Whereas there, they really want pictures of you… that feels very cool, I think’ (informant 10)

Photographing as a practice involves some unspoken rules. The informants make a distinction between photographers who act according to the unwritten rules, treating the models respectfully and those who do not. It is considered respectful to ask if you can take a picture, and to give your business card to the model. Moreover, the photographers should provide the models with the photographs for free, and they should not take pictures of anyone who is eating or taking a break. When a participant is posing for the camera, many other photographers take pictures as well. This is allowed, especially when the models receive the contact details afterwards.

‘A photographer … taught me the rule that when you are doing a photoshoot with someone, you have to give that person your attention. There are always other people taking photographs as well, but when they want to give you directions, you ignore them.’ (informant 1)

But there are also photographers who secretly take photographs without asking and then walk away. This is not appreciated at all and the informants refer to them as snipers.

‘We put a lot of time in it, and you just click and you are gone.’ (informant 11)

‘We never really get what motivates the snipers.’ (informant 13)

Photographing has a double function. Besides being a social practice during the event, evoking performances and interactions, the photographs form a link between the kingdom of Elfia as a place, and the continued embodiment of the characters after the event. After crossing the border back to reality (see ), many informants keep embodying their characters via online interaction, sometimes on a daily basis. These are online frontstage practices, for which the photographs taken at Elfia are used.

‘Cosplayers are people who need photographers; we need them for our Facebook or Instagram with cosplay-related things.’ (informant 13)

‘I place picture of photoshoots online, of events, progress pictures of the things that I am making, mostly those things. I interact with people who do the same. You exchange advice, and eventually you get to know each other at an event.’ (informant 1)

Although the characters become part of the informants’ everyday lives, most people keep the fantasy part of their lives separate from the ‘real world’. This has to do with practical considerations and the anticipated judgment of others. ‘There are for example teachers who do not want their pupils to know that they are doing photoshoots in a certain type of costume’ (informant 14).

‘When I apply for a job, I do not want people to google me and find me in all these costumes’ (informant 1).

Despite this, the constant performance of the character, makes it become a part of the performer.

‘I first thought for a while, there is (real name) and there is Medusa, and you have to keep them tightly separated, but this is becoming more and more difficult’. (informant 1)

All in all, the extraordinary reality of Elfia is constructed through a variety of practices. The practices during the event, such as performing in character and photographing, are supported and enabled by the practices around the event, such as the making of the costume and online creative practices. In other words, the practices at the event are connected in bundles and complexes (Shove et al., Citation2012) with practices before and after the event.

Although it is tempting to define the event as a front stage, and everyday life as backstage, the data show a more diffuse picture. There are also backstage practices during the event, such as eating something without wearing a mask and there are front stage practices in everyday life, such as participating in online groups. In order to create the extraordinary, front stage and backstage practices are inseparable ().

Table 1. Front stage and backstage practices of Elfia.

Conclusion

Events are generally defined as extraordinary and opposite of everyday life (Falassi, Citation1987; Goldblatt, Citation2011). The performance turn has challenged this idea. By analyzing the practices that create the extraordinary, a more diffuse picture emerges. A first conclusion is that not just event scholars and event organizers generally present events as opposite to everyday life. Elfia is also described like this by the informants. In the interviews, they present Elfia as a break from everyday life, very much in line with how Ronström (Citation2011) describes events. Furthermore, they embrace the ‘border to fantasy’ that marks the entrance to the mythical ‘Kingdom of Elfia’, of which they can be inhabitants twice a year. It looks like the participants, who actively perform the border to fantasy, want to keep a clear line between the extraordinary setting of the event and their everyday lives. The distinction between the extraordinary and the everyday has a function for the participants, because it indicates the liminal space of the event, although they do not present this as an escape from, but as an addition to their lives.

However, when studying the sayings and especially the doings of the practices that construct the extraordinary, it becomes clear that the participants do not completely leave reality behind when they cross the border to fantasy. Similarly, when they cross the border back to reality, they do not leave fantasy behind, but they take it with them into their everyday lives.

By studying the practices of Elfia, it becomes clear that everyday life spills over into the extraordinary of the event. The social reality of the kingdom of Elfia is very similar to everyday life. The participants take their social expectations with them when they perform the extraordinary during the event and they act according to them. Additional unspoken rules develop within the practices, as can be observed in the interactions between the photographers and the models. Instead of being the opposite of everyday life, the event is a temporary re-arrangement of social order and status. The participants can influence their position and status in the event practices by acquiring a spectacular costume. The costume enables them to take part in the event practices and it makes them the focus of attention. The temporary positions at Elfia can differ significantly from the positions and status that people have in everyday life, and this is where the escapist possibilities lie.

Likewise, the extraordinary spills over in everyday life. The fantasy and mythical aspects are not left behind when people cross the ‘border to reality’. Participation in the event requires preparation, so the participants need to engage in other practices that are situated in everyday life, such as the making of the costume (materials), for which they have to learn new skills (competences), which can be a struggle as one of the informants describes how she suffered burns from melting plastic. Some informants have separate rooms in their houses dedicated to these practices. Another informant bought a bigger dining table so she could use it for making costumes. A second way in which the extraordinary intertwines with everyday life is via the online interactions of the informants. The fantasy character is not only embodied during the event but also online, sometimes daily, adding a mythical and extraordinary dimension to the lives of the informants.

In conclusion, the idea of events as the opposite of everyday life is too simplistic. This study demonstrates how the extraordinary is intertwined with the everyday. Although this research is based on one specific case, the value of this study lies in the notion that events are far more than an escape from everyday life. This notion is also transferrable to different types of events. Recognizing the spill over of the extraordinary into the everyday lives of the participants and vice versa is an important start for a deeper understanding of how events form an integral part of people’s lives.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Prof. dr. Greg Richards and to Dr. ir. Bertine Bargeman for their support and valuable comments. Moreover, thanks are due to Helena Struik, organiser of Elfia, for giving me the opportunity to conduct this case study. Finally, thanks are due to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and detailed comments.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bargeman, A., & van der Poel, H. J. J. (2006). The role of routines in the vacation decision-making process of Dutch vacationers. Tourism Management, 27(4), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.04.002

- Cohen, E., & Cohen, S. A. (2012). Current sociological theories and issues in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 2177–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.07.009

- Crawford, G., & Hancock, D. (2019). Cosplay and art as research method. In Cosplay and the Art of Play (pp. 51–85). Palgrave Macmillan.

- De Geus, S. D. ., Richards, G., & Toepoel, V. (2016). Conceptualisation and operationalisation of event and festival experiences: creation of an event experience scale. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(3), 274–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1101933

- Durkheim (1912). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Oxford University press. (Original work published 2001).

- Edensor, T. (2001). Performing tourism, staging tourism: (Re)producing tourist space and practice. Tourist Studies, 1(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879760100100104

- Falassi, A. (1987). Time out of time: Essays on the festival. University of New Mexico Press.

- Getz, D. (1989). Special events: Defining the product. Tourism Management , 10(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(89)90053-8

- Getz, D. (2008). Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tourism Management, 29(3), 403–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.017

- Giovanardi, M., Lucarelli, A., & Decosta, P. L. (2014). Co-performing tourism places: The “Pink Night” festival. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.09.004

- Gn, J. (2011). Queer simulation: The practice, performance and pleasure of cosplay. Continuum, 25(4), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2011.582937

- Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday.

- Goldblatt, J. (2011). Special events: A new generation and the next frontier (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Jago, L. K., & Shaw, R. N. (1998). Special events: A conceptual and definitional framework. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 5(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.3727/106527098792186775

- Jaimangal-Jones, D., Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2015). Exploring dress, identity and performance in contemporary dance music culture. Leisure Studies, 34(5), 603–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.962580

- James, L., Ren, C., & Halkier, H. (2018). (eds) Theories of practice in tourism. Routledge.

- Lamerichs, N. (2011). Stranger than fiction: Fan identity in cosplay. Transformative Works and Cultures, 7. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2011.0246

- Lamerichs, N. (2014). Costuming as subculture: The multiple bodies in cosplay. Scene, 2(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1386/scene.2.1-2.113_1

- Lamers, M., Van der Duim, R., & Spaargaren, R. (2017). The relevance of practice theories for tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.12.002

- Larsen, J. (2005). Families seen photographing: the performativity of tourist photography. Space and Culture, 8(4), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331205279354

- Larsen, J. (2008). De‐exoticizing tourist travel: Everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies, 27(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360701198030

- Larsen, J., & Urry, J. (2011). Gazing and performing. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(6), 1110–1125. https://doi.org/10.1068/d21410

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585

- MacCannell, D. (1999). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. University of CaliforniaPress.

- Morgan, M. (2008). What makes a good festival? Understanding the event experience. Event Management, 12(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599509787992562

- Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work, and organization: An introduction. OUP Oxford.

- Noy, C. (2014). Staging portraits: Tourism’s panoptic photo-industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 47, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.04.004

- Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage Publications.

- Peirson-Smith, A. (2013). Fashioning the fantastical self: an examination of the cosplay dress-up phenomenon in Southeast Asia. Fashion Theory, 17(1), 77–111. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174113X13502904240776

- Platt, L. (2011). Liverpool 08 and the performativity of identity. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 3(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2011.539380

- Rahman, O., Wing-Sun, L., & Cheung, B. H. M. (2012). Cosplay: Imaginative self and performing identity. Fashion Theory, 16(3), 317–341. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174112X13340749707204

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M.-B. (2015). Social constructions of value: Marketing considerations for the context of event and festival visitation. In O. Moufakkir & T. Pernecky (eds), Ideological, Social and Cultural Aspects of Events (pp.74–85). CABI International.

- Ronström, O. (2011). Festivalisation: what a festival says - and does. Reflections over festivals and festivalisation. Paper read at the international colloquium “Sing a simple song”, on representation, exploitation, transmission and invention of cultures in the context of world music festivals. Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 15–16. September, 2011

- Scarles, C. (2012). The photographed other: Interplays of agency in tourist photography in Cusco, Peru. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 928–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.014

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. SAGE.

- Simons, I. (2019). Events and online interaction: the construction of hybrid event communities. Leisure Studies, 38(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1553994

- Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Sterchele, D., & Saint-Blancat, C. (2015). Keeping it liminal. The Mondiali Antirazzisti (Anti-racist World Cup) as a multifocal interaction ritual. Leisure Studies, 34(2), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2013.855937

- StJohn, G. (2017). Civilised tribalism: Burning man, event-tribes and maker culture. Cultural Sociology, 0(0), 1–19.

- Turner, V. (1967). The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.

- Turner, V. (1979). Frame, flow and reflection: Ritual and drama as public liminality. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 6(4), 465–499. https://doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.6.4.1979.465-499

- Turner, V. (1995). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine de Gruyter.

- Urry, J. (1990). The Tourist Gaze. Sage.

- Van Gennep, A. (2010). The Rites of Passage. (Reprint ed.). Routledge. (Original work published 1960)

- Wilson, J., & Moore, K. (2018). Performance on the frontline of tourism decision making. Journal of Travel Research, 57(3), 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517696982