ABSTRACT

This study explores the travel of integrated reporting (IR) from a global private sector reporting idea into a local public sector entity. Drawing on the Scandinavian institutionalist notion of translation, a case study approach is adopted to analyse the continuous transformation of the idea of IR. The case study unfolds the process as IR became dis-embedded from the corporate reporting context, packaged as an adaptable accounting technology to be unpacked, and re-embedded in a public sector entity. This study extends the current literature in three areas. First, it contributes to how IR moves across context. By recognising the importance of both the macro-trends and the idiosyncrasies of the micro context, it provides a holistic perspective on the continuous adaptions of IR as it travels, thereby contributing to our understanding of the diversity inherent in IR practice. Second, it provides empirical insights into the challenges of adapting IR in a public sector context. Third, it reveals the idea carrier's instrumental role in connecting different contexts and in editing and giving meaning to the continuous translations of IR.

Highlights

Illustrates the emergence of a “new” reporting idea, namely integrated reporting from the global corporate reporting context into a local public sector context.

Analytical focus on the process of translating IR and the continuous transformation as it travels across contexts.

Brings out the role of individual idea carriers in the preadoption phase of IR, highlighting the relational and rhetorical work involved in the travel of ideas across contexts.

Reveals the fragility of the idea as the meaning structures embodied in the translation do not support integrated thinking.

1. Introduction

The modern-day rationale to enhance transparency, accountability, and stewardship of resources is driving transformation in both the public and private sectors’ accounting practices. The emergence of the idea of integrated reporting (IR) resulted from disparate initiatives by corporations, standard-setting organisations, and regulators (de Villiers et al., Citation2014; Rowbottom & Locke, Citation2016). The 2010 establishment of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC)Footnote1 and its subsequent 2013 publication of the IR framework is one such initiative (de Villiers et al., Citation2014). According to the IIRC, IR is a process founded on integrated thinking whereby an organisation yields periodic integrated reports about value creation involving its interdependent financial, manufactured, human, intellectual, natural, and social and relationship capitals over time (IIRC, Citation2013a).

There has been growing academic IR researchFootnote2 (de Villiers et al., Citation2014; Dumay et al., Citation2016; Rinaldi et al., Citation2018). These studies have provided macro- and micro-level analyses advancing insights into IR's development and spread.Footnote3 Macro-level research focused on social structures and institutions in IIRC's emergence (Rowbottom & Locke, Citation2016); the politics and influences around IR's conceptual and framework developments (Flower, Citation2015; Reuter & Messner, Citation2015); as well as the IIRC's strategies, mechanisms, and interactions to reconfigure corporate reporting (and related) fields to institutionalise IR as a corporate reporting norm (Humphrey et al., Citation2017). Notwithstanding critical voices arguing that the IIRC shied away from original objectives, repositioning to pursue the interests of investors and the capital market (de Villiers & Sharma, Citation2020; Flower, Citation2015), IR has recently entered the global policy arena in discussions about strengthening the performance of public sector entities and accountability (Manes-Rossi, Citation2017; Pontoppidan & Sonnerfeldt, Citation2020). While the literature has enhanced understanding of institutional dynamics among various bodies developing IR for corporate reporting, there is a lack of research on macro-level developments that enabled IR to move from the private to the public sector.

At the micro level, IR research has placed substantial focus on adoption and implementation, particularly the ways in which IR has been understood and operationalised at an entity level (Rinaldi et al., Citation2018). The IR framework's broad and malleable nature, definitional ambiguities of capital types, and the complexities in its basic premises and appraisal of integrated reports have identified both its practical diversity and reservations about its quality (Cheng et al., Citation2014; Humphrey et al., Citation2017; van Bommel, Citation2014). As IR practices have become more widespread and mature in the private sector, published studies have provided micro-level analysis offering insights on detailed interactions between organisational actors during implementation and IR's impact on organisational practices (e.g. Gibassier et al., Citation2018; McNally & Maroun, Citation2018). These studies show dissimilar trajectories owing to the different adoption rationales or motivations (e.g. García-Sánchez & Noguera-Gámez, Citation2018; McNally et al., Citation2017), the various understandings of IR (Gibassier et al., Citation2018) and its fit with an entity's foundational socio-economic vision (McNally & Maroun, Citation2018). Thus, defining the idiosyncrasies of IR's application when adopted by different entities. Several studies indicated IR's potential to influence cognitive frames, thereby bringing about increased awareness of the impact of sustainability issues and a broader view of value creation (Adams, Citation2017); or the facilitation of stakeholder dialogue and accountability enhancement even when financial stakeholders remain the primary addressees (Lai et al., Citation2018). Unsurprisingly, other studies show that IR has had an incremental rather than transformative effect on an entity's awareness, processes, and structures (Stubbs & Higgins, Citation2014); in some cases, it served more as a reporting label for legitimacy reasons (Beck et al., Citation2017). Therefore, its adoption has not necessarily stimulated innovations in reporting practices (Rodríguez-Gutiérrez et al., Citation2019; Stubbs & Higgins, Citation2014) let alone organisational change (Higgins et al., Citation2019).

Research focused on IR in public sector entities – though emerging – is limited (Manes-Rossi & Orelli, Citation2020). Recently, more public sector entities have engaged with IR leading to calls for research on the context of IR and integrated thinking in the public sector arena (Lodhia et al., Citation2020; Williams & Lodhia, Citation2021). New public governanceFootnote4 (NPG) literature notes IR's suitability for public sector reporting drawing on the IR framework's potential to illustrate the interconnections between the various capitals making up public valueFootnote5 (Bartocci & Picciaia, Citation2013; Manes-Rossi, Citation2017), and IR's dimensions in public value creation (Oprisor et al., Citation2016). Studies on public sector early adopters focused on disclosure practices (Farneti et al., Citation2019; Montecalvo et al., Citation2018; Veltri & Silvestri, Citation2015); case studies on adoption are uncommon (e.g. Dicorato et al., Citation2020; Guthrie et al., Citation2017). Some early evidence showed IR's potential for stakeholder engagement because of its broader value conception, enabling both a multidimensional picture of accountability and a more holistic overview of public entity performance. However, IR's impact depended on its antecedents (Guthrie et al., Citation2017), and factors affecting implementation, including the entity's resources, management commitment, and strategic focus (Williams & Lodhia, Citation2021). Very few studies have discussed the rationale for considering IR and pre-adoption actor interactions, which reveal the micro-level processes that make IR adaptable to the public sector and why core stakeholders embrace, exclude, or ignore different forms of IR (cf. Humphrey et al., Citation2017).

This study advances IR literature drawing on Scandinavian Institutionalism as a theoretical lens to analyse how and why the global corporate reporting idea, IR, travelled across contexts to a local public sector entity. Given that an idea journey does not imply reproducing exact copies of original ideas (Campos & Zapata, Citation2014), we focus on what enables IR's journey and the translation process involved in its adaption (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Czarniawska-Joerges & Sevón, Citation1996, Citation2005; Lamb & Currie, Citation2012; Sahlin-Andersson, Citation1996). We adopt a case study describing IR's journey to the Bristol City Council (BCC). A group of stakeholders together with the BCC explored IR as a reporting framework to meet new obligations when Bristol won the European Green Capital (EGC) award. This provides us with the opportunity to focus on IR translation in our empirical case during the pre-adoption phase.

This research makes three contributions to the literature. First, it contributes to studies on IR's spread by theorising how the idea moves from the private to the public sector, and from the macro to micro context, through four phases of travel: dis-embedding, packaging, unpacking, and re-embedding (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Erlingsdottir & Lindberg, Citation2005). Through analysing the macro-trends and micro-processes, we demonstrate how the IR idea became dis-embedded from the private sector context and adapted at each new instantiation, thereby contributing to understanding IR's practise diversity. Second, it supplements NPG discussions on IR's public sector suitability by providing detailed empirical evidence on micro-processes involved in translating and adapting IR to this context. It also adds to knowledge of the underlying tensions between public and private sector rationales and the complexities involved in translating IR to new contexts. Third, while previous studies have focused on the role of ideas as a mechanism for instituting public sector accounting changes (Carlin, Citation2000; Christensen & Parker, Citation2010), this study contributes by enhancing understanding of the idea carrier's role in developing and disseminating private sector ideas and models into the public sector. It elucidates the idea carrier's work in connecting different contexts through relational and rhetorical strategies, and in editing and giving meaning to IR's continuous transformation.

2. Theoretical framing

Scandinavian institutionalism focuses on how and why ideas become widespread and how they are translated as they flow (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Sahlin & Wedlin, Citation2008). This research draws on the central premise of the Scandinavian institutional perspective that ideas do not travel in a vacuum but are rather enabled to do so within the context of other ideas, actors, traditions, and institutions (Mennicken, Citation2008; Sahlin & Wedlin, Citation2008).

Building on the foundational work of organisational institutionalism (cf., Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977), Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón (Citation1996) developed an alternative stance on institutional theory. Central to their theoretical movement is the analytical attention they provide to the travel of ideas and how the process of translation can be better understood. Thus, the focus is on the process rather than the outcome of institutionalisation and the influence of institutions in the organisational context (Czarniawska, Citation2008). This strand of institutionalism partly evolved through the incorporation of key concepts from Actor Network Theory – particularly that of translation – to initiate institutional analysis that is more sensitive to the continuous and indeterminate nature of organisational change (Modell et al., Citation2017).

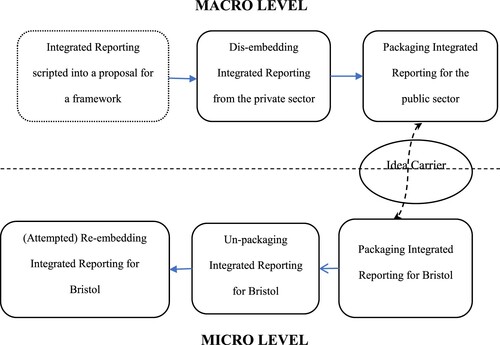

Understanding the travel of IR entails a study of a complex process that involves building new institutional settings to transform the environment in which the transfer takes place. Ideas can thus travel in a multitude of ways and forms. An idea can, for example, travel when it is de-contextualised and institutionalised as a script or standard (Røvik, Citation1996). A script embedded in one context can be transferred to other contexts and then translated according to the new frame of reference present at that location (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996), thus becoming re-embedded in a new context. This process of ideas travelling and then re-embedding in a new context is conceptualised by Czarniawska and Joerges (Citation1996) as occurring in four phases (see also Erlingsdottir & Lindberg, Citation2005): dis-embedding (separating the idea from its original institutional surroundings); packaging (translating the idea into an object); unpacking (re-translating to fit a new context); and re-embedding (translating locally into new practice). The phases conceptualise the ongoing process of translation, through which ideas can be edited and translated into other ideas, objects, or actions (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996). The concept of editing emphasises that the recontextualization of ideas may change the formulation, meaning, and context of models (Sahlin & Wedlin, Citation2008).

The process of translation has been described as “the relational and rhetorical work involved in making the development and spread of scientific inventions, calculative practices or models of financial control” (Mennicken, Citation2008, p. 389). The relational nature of translation, entailing interactions and negotiations, embraces a continuous struggle on the part of its advocates to stabilise a given translation against various destabilising efforts (Pipan & Czarniawska, Citation2010). For an idea to travel, it must be translatable and operable (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996) as well as be supported by “different people, technical devices and activities” (Mennicken, Citation2008, p. 389). Such support includes, powerful actors lobbying on behalf of the standards, political agendas stressing their importance as well as conferences and seminars promoting their usefulness (Ibid.).

Idea carriers have been identified as the key actors that develop and disseminate ideas and models into new contextual surroundings (Sahlin-Andersson & Engwall, Citation2002). Within the broader research agenda on accounting change, consultants assume the role of agents of change by applying their expertise to the process of privatisation (Jupe & Funnell, Citation2015) and the transformation of accounting processes (Christensen, Citation2005; Lapsley & Oldfield, Citation2001), thereby highlighting their potential role as idea carriers. Scandinavian institutionalists stress the role of ideas carriers who edit ideas, allowing them to cross contexts. The most common carriers have proven to be researchers, professionals, leaders, consultants, and planners, all whom are legitimate players on the global stage. As such, an integrated approach to diffusion needs to recognise that translation is a fundamentally important process, and that idea carriers, as the merchants of meaning play a pivotal role in carrying ideas across time and space (Czarniawska-Joerges, Citation1990).

While Scandinavian Institutionalism focuses on the micro-processes by which ideas travel, Suárez and Bromley (Citation2016) focus on macro-trends, which in a combined analysis bring richness to our understanding of the flow of social phenomena. As such, incorporating an analytical focus that recognises the value of the combination of these two contextual levels of analysis (Schriewer, Citation2012; Suárez & Bromley, Citation2016; Takayama, Citation2012) contributes to our understanding of how ideas scripted at the macro level travel to public sector entities in a micro context (Czarniawska-Joerges & Sevón, Citation2005). In this study, macro refers to global or international reporting developments and trends driven by forces beyond the control of the BCC, while micro refers to developments and processes operating either internally or directly interacting with the BCC.Footnote6 Analytical attention on how and why ideas move between the macro and micro context clarifies how they are shaped and received (Suárez & Bromley, Citation2016).

When an idea transitions into a new context, it can take on different meanings for the recipients. Translation can, therefore, involve the establishment of similarities that persist across contexts in conjunction with the creation of differences. When an idea travels across contexts, enough of the original idea remains to merit recognition, yet the carriers and receivers rarely embrace or enact an idea without it being at least partially changed (Suárez & Bromley, Citation2016). Translation draws attention to the changes undergone and produced for adoption in the micro-context. Mennicken (Citation2008, pp. 389–90) highlighted that standards “must be made understandable, applicable, and workable, resulting in a series of transformations which affect not only the adopters and their practices but also the standards themselves”.

The translation of ideas provides a useful theoretical framework to address the question of how and why an idea travels between contexts as well as within a context. Drawing from this theoretical framework, the analysis of the travel of IR (a private sector reporting idea) to the BCC (a public sector entity) is focused on the translation process as IR moves across contexts (private to public, macro to micro) over the four phases of travel. In each phase, we examine the role of the idea carrier and the local context which determine the editing rules within which IR is translated and transformed.

3. Method

3.1. Research setting

A case study (Yin, Citation1981) was designed to provide in-depth empirical insights into IR's travel to the BCC. We first encountered the BCC case at the May 2015 Public Sector Pioneer Network (PSPN)Footnote7 meeting held in London, where IR was explored as a public sector reporting tool. The BCC is the local authority of Bristol, one of the most densely populated cities in South West England. It applied for the EGC award as a catalyst to collectively work towards its long-term goal of building a green city, creating sustainable communities, and improving citizens’ quality of life (BCC, Citation2003, Citation2016). Bristol received the EGC 2015 title in 2013, which led to new reporting obligations and accountability structures (European Commission, Citation2015). In 2014, Bristol2015 – a private entity with a one-year lifespan – was established to manage the EGC Program (Bristol2015, Citation2015c), including the development of a comprehensive knowledge transfer programme consisting of a series of how-to modules on different themes to help other cities to become more sustainable by learning from Bristol's case (the Bristol Method) (Bristol2015, Citation2015a). In this context, a Measurement Group (MG) was coordinated to develop a module on how to measure city sustainability. IR was introduced by an MG member during discussions between mid-2014 and early 2015, when it was explored as a possible reporting framework to measure the EGC award's impact and value-added to Bristol. Before the end of its tenure, Bristol2015 presented a translated version of IR to the BCC for its consideration as a potential tool they could consider employing in the longer term. No commitment, however, has been made to adopt IR as a reporting framework and hence, our study focused on the translations of IR by the MG in the pre-adoption phase.

3.2. Data collection

We focused on collecting data from 2011 (when the idea of IR was scripted in the discussion paper “Towards Integrated Reporting – Communicating Value in the 21st Century”) to 2016 (after the publication of the Bristol Method and the delivery of the proposal to the BCC). Our data were collected through documents, informant interviews, and participant observations of practitioner events as well as webinars relating to IR in the public sector.Footnote8

Data were collected in three rounds, with the first review of documentary materials initiated after the May 2015 PSPN meeting. The documents included publicly available official documents (such as progress reports, memoranda of understanding and policy papers), and BCC and Bristol2015 internal documents (such as summaries of meetings and decisions). These documents provided micro context data within which IR was explored, the BCC's obligations and relationships with key stakeholders, and communication pertaining to IR. We also reviewed relevant publications and reports by organisations that influenced the BCC's reporting obligations that provided data on the macro-trends and forces influencing the translation of IR to the public sector context.

At this initial stage, we classified relevant documents two-dimensionally to create a database that was sorted and categorised according to criteria such as the source of origin, date, type of actor, document purpose, and selected keywords. Thereafter, we identified the core actors and their interrelationships to establish a chronological written narrative of actions, events, and rhetorical strategies enabling IR's travel into Bristol at both the macro and micro levels (cf. Malsch & Gendron, Citation2011). At the macro level, the core actors involved in making IR translatable to the public sector – particularly in the UK – included the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA), the PSPN, the IIRC, the Consultative Committee of Accounting Bodies (CCAB),Footnote9 and global consultancy firms. At the micro-level, core actors included the European Commission, the main EGC project sponsors, and the MG. The MG consisted of representatives from the BCC, Bristol2015, and five core BCC stakeholders: the consultancy firm, Bristol Green Capital Partnership (BGCP), Happy City, University of the West of England, and University of Bristol.

Following the document review, the second stage of data collection included conducting informant interviews with six individuals with the purpose of obtaining insights from individuals directly involved in IR's translation process to fit the Bristol / public sector context. The interviewees represented five different MG organisations. The sixth interviewee from a global consultancy firm was actively involved in IR's translation at the macro level. Semi-structured interviews were conducted focusing on key themes: how the idea of IR came about in the MG's discussions; the interviewees’ understanding of IR; their reflections on the processes and discussion involved in making IR suitable for the public sector; as well as the challenges of adapting and embedding IR in practice. The number of interviewees were determined by the purpose of the interviews and the MG's size.Footnote10

The interviewees were provided with this study's purpose and an outline of questions prior to the interview. The interviews conducted via telephone or Skype, which lasted between 60 and 90 minutes were recoded with the consent of the interviewees, and transcribed. The interviewees were also given the option of reviewing the interview quotes used in this paper. To ensure promised anonymity, we divided them into three groups (A, B, and C) with each group representing a specific organisation category. shows each organisational grouping and a description of interviewees.

Table 1. Grouping and description of interviewees.

After the interviews and throughout 2016, the third-stage data collection was carried out. The interviewees provided relevant documents that were not publicly available.Footnote11 The final database, consisting of documents collected in phases 1 and 3, amounted to 51 documents (Appendix 1). The interviews and additional documents strengthened findings, allowing us to detail the translation process during each phase of IR's travel to the BCC and the core actors involved along with their interests and interactions.

3.3. Data analysis

The documentary material, observation notes and interview transcripts were analysed by drawing on a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Both authors familiarised ourselves with the data collected by reading and re-reading them in an interpretative and contextual manner prior to them being coded to capture the meaning within the data (ibid.). We coded the data manually in Excel and categorised it by actor temporally, drawing out the chronology of events. Initial themes were generated, which were used to identify potential theoretical concepts (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). By moving iteratively among the initial themes, data, and potential theoretical concepts, we identified that the levels (Suárez & Bromley, Citation2016) and phases (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996) of travel provided a relevant theoretical framework to analyse and present our findings. Throughout the coding process we applied check-coding of each other's coded data. This was done to ensure consistency between the coders’ data reduction (Herbohn, Citation2005). Through this iterative process we compared the coded data set, making required modifications. The document analysis was also used to contextualise interview responses, which we view as narratives where participants construct meaning and impart knowledge (Czarniawska, Citation2004), hence providing the voice of the interviewees (Bowen, Citation2009).

We reviewed our initial coding based on these theoretically-informed categories focusing on why and how IR was translated at the BCC's macro and micro contexts over the four phases of travel. In each phase, we focused on the key themes including actors involved, enabling activities and mechanisms, and relational and rhetorical work in the travel and editing of IR ideas.

4. Findings

This section is structured into two parts depicting the travel of the idea of IR (see ). The first section presents the dis-embedding of the idea IR from the private sector context and its packaging for the public sector at the macro level. The second section presents the travel of IR to Bristol and its re-contextualisation within local institutions and practices at the micro-level.

4.1. Travel of the idea of IR at the macro-level

4.1.1. Scripting the idea of IR

The idea of IR was scripted by the IIRC in their 2011 discussion paper, which states:

Integrated reporting brings together the material information about an organization’s strategy, governance, performance, and prospects in a way that reflects the commercial, social, and environmental context within which it operates. (IIRC, Citation2011, p. 6)

(an) Application of the collective mind of those charged with governance, and the ability of management to monitor, manage, and communicate the full complexity of the value-creation process, and how this contributes to success over time. (IIRC, Citation2011, p. 6)

4.1.2. The journey of the idea of IR to the public sector

Responding to the 2011 discussion paper, public sector bodies conveyed that IR was not helpful because of the different conceptions of integrated management and value assessment applied in public sector entities (IIRC, Citation2012). The script nevertheless paved the way for IR to be dis-embedded from the private sector setting. Our documentary analysis indicates that IR's journey to the public sector was facilitated by the relational work and networking efforts of the IIRC, with several core actors importantly, CIPFA, the CCAB, global accountancy firms, and the World BankFootnote12 that were involved in the global movement to change the scope of public sector external financial reporting.

Between 2012 and 2013, the IIRC and CCAB hosted an IR round table and several workshops that provided a forum for interested parties to discuss the applicability and benefits of IR to public sector entities. The events resulted in the publication of a discussion paper on the relevance of IR to public sector reporting elucidating the similarities and differences in concepts between the public and private sector reporting obligations (CIPFA, Citation2013). While the similarities were emphasised, the discussion on the differences pointed to key concepts, namely, accountability, stakeholder, and value creation, where features unique to private sector reporting could be stripped out and formulated in more general terms (dis-embedding from the private sector-focused setting) to enable its travel.

The IIRC established the PSPN in November 2014 through funding sourced from the IIRC reserves and participant contributions, and staffed through secondments from global accountancy firms (Interviewee A1). It provided a standing structure and a forum for the core actors to coordinate activities to spread and adapt IR to the public sector context (including early users to share their experiences during webinars and seminars).Footnote13 Notably, several core actors (such as global accountancy firms) had already circulated the idea of IR in the public sector through their various publications (see IIRC & CIPFA, Citation2016), connecting the travel of ideas between the global and local contexts.

The collaborative work of these actors was compiled in a 2016 report by IIRC and CIPFA entitled “Focusing on value creation in the public sector”. Set against the backdrop of the multiple challenges faced by public sector entities arising from their complex activities, diverse stakeholders, and broad definition of public value, IR was edited to address conflicting public accountability requirements and demonstrate the sustainable value of services to a wider stakeholder base. It was packaged as a mechanism providing insights into an entity's strategy, resources, and relationships that facilitate the delivery of sustainable outcomes, thereby creating value for the entity, key stakeholders, and the wider society (IIRC & CIPFA, Citation2016). The form of IR that was presented for use in the public sector, along with the meanings of its modified concepts, stand in contrast with the 2013 IR framework, where the focus is on value creation for the reporting entity and the information needs of financial stakeholders (IIRC, 2013a).

4.2. Travel of the idea at the micro-level

4.2.1. Packaging IR for the public sector in Bristol

4.2.1.1. The local context

The travel of IR to the Bristol context was facilitated by a consultancy firm following the awarding of the EGC 2015 title (PSPN meeting, 2015). The award obliged the BCC to submit to the European Commission two ex-post reports (after one and five years) detailing the overall improvements, plans implemented, and achievements made to-date to measure the impact and added value of the award for Bristol and its residents (European Commission, Citation2015). While a detailed set of societal, economic, and environmental indicators was prescribed, the method and measurement of the impact were left to the discretion of the BCC (ibid.)

Bristol2015 was established to manage the EGC 2015 Programme,Footnote14 serving as a vehicle for private sector actors to engage and contribute in-kind to the programme (Bristol2015, Citation2015c). Although £12,600,000 was raised from a mix of public and private sources, only 1.3% of the sponsorship funding was allocated to measuring the impact of winning the EGC award (BCC, Citation2016).Footnote15 Given the limited resources, Bristol2015 relied primarily on sponsorship-in-kind to develop a component on how to measure the sustainability of cities as a part of the Bristol Method. In this context, the MG consisting of BCC's existing closely-knit core group of stakeholders who were involved in promoting, enabling sustainability work across sectors in Bristol and other private sponsors was brought together. Through private sponsorship, the consultancy firm secured a position in the MG (Bristol2015, Citation2015c).

Although the MG was tasked from its inception with developing part of the Bristol method, the group reached consensus based on different rationales to work beyond their mandate by exploring a longer-term measurement framework of the city's sustainability.Footnote16 While the consultants expressed an interest in accumulating the skills and experience necessary for commercial grounds “to help other cities adopt the same framework” (Interviewee A2), interviews with Group B and C individuals cited reputational and compliance reasons, respectively, as the empowering factors to develop such a framework.

It was something the MG saw a huge value in delivering … the pioneering effort which fits with Bristol's reputation as a laboratory of change, meaning that other cities can easily learn from our work, and adapt and use it. (Interviewee B1)

This is primarily driven by the formal obligation we had from the European Commission to report in 2020 … . An assessment did not just focus on the year itself or the activities of the year but a whole change in approach that was literally achieved by the award of the EGC. (Interviewee C2)

4.2.1.2. The idea carrier: connecting macro and micro levels

At the macro level, the consultancy firm had been engaged in the activities of the PSPN by promulgating IR as a framework that could be “readily adapted to” public sector entities’ broader goals (IIRC & CIPFA, Citation2016). Represented in the MG were consultants who individually had more than ten years of experience working with stakeholder engagements in both the public and private sectors. The consultants were keen proponents of IR and held the belief that IR has clear relevance to public sector entities.

It is very natural for us to try and follow the emerging trend and to actually contribute and shape them. We have people working with the IIRC and on IR and a number of our clients are also pilot members of integrated reporting … it is very natural that (the consultancy firm) is involved in this space, and we see it as one potential future for reporting on not just sustainability but the wider business context.

Personally … I realised actually that it (the six capitals) is something that does not just apply to businesses but could apply to … individuals and their six capitals, cities or universities … The concept works better once you apply it to specific geography rather than a business that shares its geography with others. (Interviewee A2)

4.2.1.3. Packaging IR in the Bristol context

The sustainability of a city is difficult to measure because of its complexity and multivariate nature (Czarniawska, Citation2010), a problem compounded by the lack of consensus on not only the conceptual framework and the approach favoured but also on the selection of an optimal number of indicators (Tanguay et al., Citation2010). Our documents and interviews reveal that IR was introduced by consultants when several other initiatives and standards for measuring the sustainability of cities were discussed by the MG. Although IR has been widely discussed in academic, corporate, and policy circles, the consultant reflected that the MG was not familiar with the IR framework.

None of them had ever heard of it before, which is interesting because it only shows that IR has not found its way into city management and common academia. We had to explain the framework to them. What they really liked was the transfer of value concept … They saw it as a framework rather than anything and that is what we tried to put forward. (Interviewee A2)

Many stakeholders in the MG were not familiar with IR; the group kept going back and forth on “why IR?” … (the consultants) led the work looking at different models: One Planet Cities, Seattle Initiative, Gross National Happiness, Global Compact Cities, Green Cities Index, Green City Initiative among others to explain if IR is the better one. (Interviewee B1)

… bringing together the ideas of the group and our own ideas for the measurement of the impact of the EGC … to help develop a framework that can be expanded over time to measure the broader sustainability of the city. (Interviewee A2)

To create a shared understanding, the consultants invited the participation of the other members of MG in the co-construction of the criteria for a globally recognised and credible framework for sustainability reporting of cities. The problems addressed provided consultants with the legitimacy to advocate a framework approach to reporting rather than adhering to more prescriptive standards. The framework was packaged as providing a common language with a global reach, clear structure and the capacity to accommodate all aspects of a city – both in the short and long term – in a connected manner that both incorporated Bristol's EGC themes while remaining independent of them, thus providing longevity (Bristol2015, Citation2015a). The criteria created a clear pathway for IR to be proposed as the ideal and most pragmatic overarching framework to serve as a device in bridging the extant models of reporting and the diverse needs of stakeholders. The framework was positioned as a tool that allowed for comparability across cities over time, as used at the macro level by the most progressive organisations that recognise the importance of long-term sustainability in decision making. This resonated with Bristol's objectives of becoming a “global leader in sustainable urban living” (Bristol2015, Citation2015c). Ensuring the acceptance of IR as a viable option for exploration, the MG engaged in finding a common definition of the various IR capitals (refer to ), and their implications when applied in Bristol's context (packaging the IR capitals for Bristol).

Table 2. Classification of capitals in Bristol's context.

4.2.2. Unpacking integrated reporting in Bristol's context

The unpacking of IR involved a series of steps required for its translation from an abstract framework to a concrete and operational device applicable to cities, and more specifically, to Bristol. First, there was a need to find common ground among the different members of the MG. At the beginning of the unpacking process, our interviewees indicated that considerable time was spent establishing a common approach where one of the most significant obstacles to overcome was the understanding of the terms: evaluation and measurement.

In an attempt to operationalise the IR framework in the Bristol context, group C stakeholders were keen to carry out a detailed evaluation to determine the impact of Bristol's year as EGC. Drawing on pragmatic arguments, the significance of measurement was articulated by the consultants as being an instrumental component of public accountability given the limited time and resources available “to show success” to Bristol's different stakeholders (PSPN meeting, 2015). The consultants suggested that stakeholders – including the European Commission, city leaders, the local community, and the main sponsors – were interested in seeing the impacts of both the EGC designation and the various sponsor-supported activities. There was also great significance associated with the ability to “encourage behavioural changes through measurement”.Footnote17

Interviews with Group C stakeholders indicated that they did not share the same rationale as the consultants, preferring to carry out a detailed evaluation to determine the impact of Bristol's year as EGC, which involved systematically determining the outcome or impact of sustainability initiatives through stakeholder engagement. One interviewee from this group noted:

From a private business viewpoint, it is far more about specific actions, activities, and changes. When we talk about the public, I tend to think about the community groups, the schools, students, and that to me is far more about engagement. What we have seen is a significant increase in community engagement by students, engagement with schools, awareness, collaborations on environmental themes and issues, which is far more difficult to analyse in terms of numerical measurement … the reality of how we measure it from the ground, how we see it on the ground, how do we engage with real people as to what their (sustainability) approaches and interests are … we have to make sure we continue to engage with the people on the street. (Interviewee C1)

We cannot afford to be particularly selective whom to get money (from) and support-in-kind from … (the consultants) come in with their own views and values, and it poses an interesting dynamic reconciling the very diverse views of the BGCP and the specific views of the sponsor. We tried to work together in developing a package, and the analysis in the Bristol Method is the outcome of that. (Interviewee C2)

Bristol, as an EGC, has been built on partnership engagement. … We risk the danger that people pick indicators in isolation and do not understand what is going on. There is a need to look at synergies and cross issues to avoid superficial reporting that does not inform policy. (Interviewee B2)

IR was advocated as a framework based on the common ground established within the group as a business approach to reporting in the public sector that fully embraces stakeholder inclusivity and the critical need for financial, economic, environmental, social, and governance sustainability (Interviewee A2). It was then unpacked as a pragmatic device to assemble and collate more than 150 KPIs from existing standards to the six capital types providing a menu of KPIs ().

Table 3. Capital types and KPIs determining value created and destroyed.

The MG worked with academics to consider behavioural proxy metrics that were indicative and representative, as well as capable of registering change within a year to measure behavioural changes over 2015 (interviewees A2 and B1). This entailed the measurement of the inputs into the year and the resultant outputs and inferred outcomes. The group also discussed a standard set of KPIs for each project and theme, and then developed intervention project-level metrics against relevant capital types to infer the impact this may have on the macro datasets to form the basis of the five-year report obligations arising from winning the EGC award.

The criteria for selecting a measure included data availability and comparability, its usefulness to stakeholders, and its inclination to reflect change within the one year (Interviewee A2). The measures were then divided into two available datasets, data with a likely source and data with an unknown source. The consultants provided further support for the consultancy's methodology by translating IR to be a device that could look across various capital types and provide a common language wherein these capital types could be traded off.

The unpacking process of making IR operable for a city that involved the MG only reached a “position of settlement within the group” (Interviewee, C2) where “an approach which all members were comfortable with” (Interviewee B1) was agreed upon. This was largely due to the different rationales of accountability, disparate views on the meaning of IR, and the various approaches to measuring the sustainability of cities between the consultants and the existent network of actors. Before its dissolution, Bristol2015 published the Bristol Method, which included a sub-module on “How to measure the sustainability of a city”. Provisional adjudication was reached where the idea carrier enhanced the transferability of IR by making it explicitly and discursively available in the sub-module (to be further translated) in measuring the sustainability of cities and as a possible framework for the BCC in the future.

4.2.3. Re-embedding translations into the local context

Bristol2015 presented the translated version of IR to the BCC as a potential tool that the Council could consider to be employed in the longer term. Our findings suggest that despite the translations and adaptations to the Bristol context, the technical, organisational, political, and cultural incompatibilities offered resistance in deterring the translation from becoming embedded.

4.2.3.1. Technical and organisational factors

The translation of IR and its subsequent failure to secure a place in the new context has indicated that any future adoption of the reporting framework would require the BCC to obtain a more relevant and complete dataset for short-, medium-, and long-term data, as well as develop a methodology to measure net output, outcomes, and connectivity between the six capitals (see ). Our interviews indicate that it was difficult for the BCC to embrace IR due to the inherent reporting structures, the in-house view of the role of reporting, and the need for substantial investment to change the technological foundation and characteristics currently employed.

The data that are available for use have been collected by different organisations (such as the Happy Cities Index, Quality of Life) for different purposes over different timeframes and heavily weighted on environmental reporting due to application for the award over the years. (interviewee B2)

One of the critical features of both applications (for the EGC award) was that we were very clear to undertake some form of evaluation or performance measurement of the value of being EGC … Although we have obtained a consensus (with the consultants) in terms of how to adapt the IR tool to a city and how it could be used in a city; at the moment, we have not committed to say right, and we will now use this tool to the next stage because my academic colleagues are perhaps looking at these in a broader conceptual way rather than (the consultants) who are looking at it from a far more analytical measurement by measurement, indicator by indicator type approach. That is something we had a challenge reconciling. (Interviewee C2)

Although the consultants expressed the conviction that the value creation and transfer were of interest to the stakeholder groups developing the Bristol Method, concerns were also expressed by the interviewees in both Groups B and C on the “trial and error approach” to monetising and connecting the various capitals. Furthermore, our findings indicate that there was an absence of active participation from important decision makers within the BCC during the translation process. This likely contributed to differing perspectives between the consultants and the BCC, with the latter perceiving accountability to stakeholders as the achievement of its political goals for which resources were channelled into sustainability programmes and, as such, reporting innovations were not prioritised.

The IR approach did not gain significant traction within Bristol … partly because there is a mismatch between what it is trying to do and where a lot of the attention is focused on that planning period. And so there has been quite a lot of conversation about it, but we have not quite nailed it down yet. (Interviewee B2)

Unfortunately, it had been the more junior staff of the council that attended the MG meetings; the person responsible for sustainability reporting was not present. (Interviewee A2)

… there are other things BCC must do more urgently. Funding is a problem. Financial control is tight. All data collection etcetera must be justified. (Interviewee C2)

4.2.3.2. Cultural and political factors

Given that new practices rarely, if ever, translate into a cultural void, it is unsurprising that this holds for IR, which employs integrated thinking that requires existing local cultural values, structures, and practices – that emphasise the characteristics of innovation, learning, and top-level commitment – to support the framework's application. In the Bristol case, the beliefs, values, and preferences of the pre-existing network of actors have markedly different ideas of accounting, measurement, and evaluation. While the MG appeared to have developed an innovative mindset during the think tank process, the BCC adopted a more compliance-oriented approach towards reporting.

In Bristol's public sector context, political priorities have traditionally played an important role in determining the nature and substance of reporting.

The challenges of diagnostic measurement tools are that they are deliberately trying to be policy-neutral. However, actual local authorities are not policy-neutral. Politicians want us to measure progress against their political priorities and objectives. The more intellectual exercise of benchmarking performance, of measuring performance against a standard … in the last decade, I have not found in Bristol a huge appetite for that. (Interviewee B2)

IR did not catch on from the start, but it could be something for the future. In this sense, the pre-existing structure (reporting structures before the discussions on IR) continues, but private sponsorship comes to an end. (Interviewee B1)

5. Discussion and conclusion

Theorising the idea journey through four phases (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Erlingsdottir & Lindberg, Citation2005), this study has attended to and connected two levels of analysis, macro and micro, by unfolding the process by which the scripted idea of IR in the 2011 Discussion Paper translated as an accounting technology for measuring Bristol city's change in sustainability.

At the macro level, the idea's objectification paved the way for IR to be dis-embedded from the private sector setting, thereby facilitating its journey across contexts. Through various dialogues concerning the role of the public sector in contemporary society, the concepts of accountability, value creation, and stakeholder diversity were edited to fit public sector reporting needs. The collaborative efforts led IR to be packaged as an accounting technology that attended to public accountability requirements, as well as facilitated and demonstrated the sustainable value of services to a wider and more diverse stakeholder base.

IR's travel to Bristol was facilitated by an idea carrier from the private sector that played a significant role connecting the macro to the micro context through packaging and unpacking IR. At the micro level, the local context provided the infrastructure whereby IR came to be discussed, and importantly, where the context-dependent rules of editing were determined. Our empirical case shows that the open nature of the IR framework (van Bommel, Citation2014) provided IR the capacity to bridge extant models of reporting while simultaneously embodying multiple capitals (Coulson et al., Citation2015; McElroy & Thomas, Citation2015). This has enabled its application for sustainability reporting for cities even though the IIRC maintains that IR is not another form of sustainability reporting. IR's unpacking allowed through co-translations for the idea carrier and other MG members to show how public value could be defined and measured. This entailed defining what the capitals in the IR framework meant to a city (Bristol). For example, social capital, was in a Bristol context defined as “the extent to which people feel connected to each other and a part of the city”. An example of one of the agreed-upon measurements for social capital was, “How often have you volunteered to help out a charity or your local community in the last 12 months?” (cf. and ).

The packaging of IR as a technology to improve city sustainability reporting was sufficient to convince the dominant collation of stakeholders to put IR on the MG agenda. However, the analysis of the translations significantly elucidates that for the idea carrier to successfully connect contexts, and for translations to be re-embed within the new context, powerful alliances, political influence, and legitimacy are important. Moreover, the translations must be technically, structurally, and culturally compatible with the local entity; aligned with the local council's accounting rationales and political goals. In their absence, ideas attempting to travel across contexts will be confronted with countervailing forces that are likely to coalesce and undermine the value and perceptions of any translation. For instance, the neutral, objective technocratic measurement of the various capitals “to show success” did not align with the multi-sectoral and partnership-based sustainability approach developed through dialogue and citizen engagement to provide a collective sense of direction which, BCC's stakeholders were accustomed. This led the council and stakeholders to perceive IR as incompatible, resisting the idea's further development. Findings further show that time and resource constraints, combined with a lack of core actor commitment, resulted in IR's translation becoming a classification exercise in patchworking the available key performance indicators according to the six capital types. As a result of the “toolkit” (Higgins et al., Citation2019) approach, the values and meaning structures embodied by the translation provided little support for the core IR ideals such as integrated thinking, connectivity of capitals and stakeholder responsiveness.

This study makes three important contributions. First, it extends the literature by advancing theoretical insights on how IR travels across contexts (Lodhia et al., Citation2020; Rinaldi et al., Citation2018). More explicitly, it connects macro and micro analyses to arrive at an enhanced understanding of the multi-level translations that have shaped the meaning of IR in its journey to the public sector. Through Scandinavian Institutionalism, this study provides a more holistic perspective examining IR's continuous adaptions at instantiations of its travels, thus contributing to understanding of the negotiations resulting in different IR forms and practices. It thereby complements both macro and micro level studies. At the macro level, it complements literature on the spread of IR in the corporate reporting field (Humphrey et al., Citation2017; Rowbottom & Locke, Citation2016) by providing insights into the work of actors, mechanisms and events involved in the translation process making IR relevant to the public sector. Notably, given the nature of public sector accountability, embracing the term public value in the packaging of IR has enabled new ways of defining, measuring and reporting on value with potential policy implications and new governance forms. At the micro level, studies on IR adoption have focused on firm-level determinants, and the tensions between push and pull factors to analyse the implementation and resulting outcome of adopting IR within different entities (e.g. Busco et al., Citation2013; de Villiers et al., Citation2017; Higgins et al., Citation2019; McNally & Maroun, Citation2018; Stubbs & Higgins, Citation2014). Studies on IR in the public sector have noted that legitimacy alone is not sufficient to produce practical changes leading to integrated thinking (Guthrie et al., Citation2017; Williams & Lodhia, Citation2021); consideration must be given to IR's antecedents. Analysing the micro processes in the translations of IR as it travels from the macro to entity level, this case study contributes to existing research by empirically illustrating that translations during the pre-adoption phase – in this case, involving a dominant coalition of entity stakeholders – was imperative to how actors, processes and logics have shaped its adaptions before it was presented to the entity for consideration. This study further extends the reasoning of Higgins et al. (Citation2019) by arguing that organisational change due to IR adoption may be either hampered or supported by the outcome of IR translations at the pre-adoption stage.

Second, this paper extends the conceptual discussions in NPG literature on IR's public sector suitability by commenting on IR translation from an NPM perspective (Almquist et al., Citation2013). As guardians of tax income, public sector entities are accountable to a broader constituency. Current debates raise questions about how the public sector can meet social expectations concerning, for example, issues of fiscal crisis and sustainable development giving rise to considerations on how public value is identified, managed, measured and reported (Guthrie & Martin-Sardesai, Citation2020; see also Caperchione et al., Citation2017). Discussion on the idea of IR in the public sector has been largely conceptual, its relevance based on the potential to illustrate interconnections between the six capitals and public value creation (Bartocci & Picciaia, Citation2013; Manes-Rossi, Citation2017; Oprisor et al., Citation2016). Researchers have notably challenged the taken-for-granted notions of universal technology applicability (Anessi-Pessina & Cantù, Citation2017; English et al., Citation2005; Pilcher, Citation2011). Larrinaga et al. (Citation2018) emphasised that private-sector models do not necessarily translate well across contexts. This study importantly identifies pragmatic and technical challenges of translating IR, particularly the complexities of defining and measuring public value through the six capitals. Public value is not only expressed in terms of output and outcomes but may be procedural, for example, through democratic participatory processes and citizen inclusivity through engagement. Our findings resonate with current IR studies, illustrating that to re-embed IR as a “new” accounting technology, its translation must be compatible with local structures, strategy and rationales, with top management support. The re-embedding of IR and thus the institutionalisation of change also calls for the active engagement of public sector accountants (Williams et al., Citation2021). We further demonstrate that although the IR framework has been conceived as a tool for integrated thinking to advance value to society, tensions are apparent as public office holders are concerned with advancing their political agenda (e.g. deployment of resources, sustainability of programs, policy change) during their term in office, which could result in a lack of will to make visible trade-offs between capitals.

Third, this study enriches our understanding of the idea carrier role in the translation process. It extends the literature on the role of consultants as change agents (Christensen, Citation2005; Jupe & Funnell, Citation2015; Lapsley & Oldfield, Citation2001). We contribute by making a distinction between core actors and idea carriers (Sahlin-Andersson & Engwall, Citation2002). This distinction is important because idea travel is facilitated by carriers metaphorically transporting ideas across contexts, and in the process, their beliefs and rationales. In this case, the idea carrier played an essential role in connecting contexts by bringing IR to the MG agenda, translating, and circulating the micro-level script (Bristol's knowledge transfer programme) through the PSPN.

Idea carriers play a key role in garnering support for the acceptability of the ideas they carry (Himick & Bivot, Citation2018). Unlike core actors, idea carriers can (but need not) be identified closely with the local context. Therefore, the idea carrier alone does not possess socio-political power as a game-changer in such environments; rather, they need to be embedded within, or draw on the support of the coalition local stakeholders to gain momentum to co-translate the travelling idea into the local context. In this case study, the idea carrier operated under private in-kind sponsorship for a limited period, and their position was weakened with Bristol2015s dissolution. We theorise that the permanence of the structural mechanisms supporting the idea carrier's work plays a key role in enhancing or weakening the process of embedding an idea (or a particular form of IR) in a new context. Furthermore, destabilising forces become stronger and more dynamic in the unpacking and re-embedding phases as previously loosely-coupled translations are drawn closer to the actual operating context and practice.

Given the different types of public sector organisations and roles in different geographical locations, we encourage further research on IR translations in different contexts, particularly local councils with close proximity and links to the community (Williams et al., Citation2011). Although IR has not currently been adopted by the BCC for its external reporting, the implications and diffusive effects resulting from IR's foray into this local public sector entity deserve further attention. This study also opens the agenda for more research on the role of, the trade-offs and interconnectedness between capitals of the IR framework to enable reporting on value creation by public sector entities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, participants at the “Integrated Thinking and Reporting in Practice” conference held at the LUISS, Rome Italy in 2016 and Irvine Lapsley for valuable comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. In addition, we extend our thanks for the insightful comments from the participants at the research seminar held in 2018 at Sweden's University of Kristianstad. Both authors contributed equally to the research and writing of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The IIRC was formally launched by the Accounting for Sustainability Project and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in August 2010. It merged with the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) in mid-2021, forming the Value Reporting Foundation.

2 This includes two special issues in the Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal in 2014 and 2018.

3 Rinaldi et al. (Citation2018) classified IR studies into three levels, macro, meso and micro. Our study draws on the work of Suárez and Bromley (Citation2016) and Scandinavian institutionalism, which focus on the macro-level to understand the global spread of formal structures and decoupling between policy and practice, and the micro-level to clarify the role of individuals and micro-processes in idea translation.

4 Research on the Public Management (Hood, Citation1991) has been extended to address “New Public Financial Management” (Guthrie et al., Citation1999; Olson et al., Citation1998), where a key focus has been on accounting technologies as a dominant part of New Public Management (NPM) (Christensen & Yoshimi, Citation2003; Lapsley, Citation1999). Despite severe criticism levelled at NPM (English et al., Citation2005), the movement has evolved, giving rise to another designation, “New Public Governance” (NPG) (Osborne, Citation2006). NPG has been characterised as having a multi-organisational focus (Manes-Rossi, Citation2017) and poses questions relating to the role of reporting and accounting technologies that go beyond their traditional financially-centred role within the public sector.

5 For a definition of public value, see Moore (Citation1995).

6 The adoption of the terms macro and micro aligns with Mohan (Citation1996).

7 The PSPN was established by IIRC in 2014 to pioneer the implementation of IR within the public sector.

8 The research has been conducted in accordance to the ethical code and guidelines of the authors’ respective research institutions.

9 The CCAB members include – Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, CIPFA, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, and Chartered Accountants Ireland. It provides a forum for the bodies to work together collectively in the public interest on matters affecting the profession and the wider economy.

10 We recognise the limitations of having six interviews. Considering that the purpose of this study is not to provide generalisability or the extrapolation of findings (McNally & Maroun, Citation2018) rather an in-depth understanding of the translation process, broadening our interviewee base to include individuals not directly involved in the translation would deviate from this objective.

11 We treat these documents with confidentiality to preserve the anonymity of our interviewees. Permission has been granted to use the interview material.

12 E.g. the World Bank advanced a reasoning on IR that alluded to its potential to “increase the visibility and transparency of how our organisations use their resources to create value over time”. https://www.sustainability-reports.com/integrated-reporting-can-help-show-public-sector-value/ accessed 7 August, 2021.

13 Members of the PSPN include the World Bank Group, UNDP, the City of London Corporation among others. See http://integratedreporting.org/news/public-sector-pioneer-network-update/ (accessed 15 January 2021).

14 The overarching objectives were to empower Bristolians, exchange sustainability expertise between cities and contribute to the 2015 UN climate change conference.

15 £25,000 was awarded to develop the Happy City Index and £138,892 to the development of the Bristol Method (Bristol2015, Citation2015b).

16 This was expressed by the five interviewees from the MG.

17 “Measurement to show success” and “encourage behavior changes through management” were reflected in our documentation as well as interviews with Interviewees A2 and B1.

References

- Adams, C. A. (2017). Conceptualising the contemporary corporate value creation process. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 30(4), 906–931. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2016-2529

- Almquist, R., Grossi, G., van Helden, G. J., & Reichard, C. (2013). Public sector governance and accountability. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(7-8), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.11.005

- Anessi-Pessina, E., & Cantù, E. (2017). Multiple logics and accounting mutations in the Italian National Health Service. Accounting Forum, 41(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2017.03.001

- Bartocci, L., & Picciaia, F. (2013). Towards integrated reporting in the public sector. In C. Busco, M. Frigo, A. Riccaboni, & P. Quattrone (Eds.), Integrated reporting (pp. 191–204). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02168-3_12

- BCC. (2003). Community strategy.

- BCC. (2016). Green Capital Funding – Final report.

- Beck, C., Dumay, J., & Frost, G. (2017). In pursuit of a ‘single source of truth’: From threatened legitimacy to integrated reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2423-1

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bristol2015. (2015a). Bristol method: How to measure the sustainability of a city. https://bristolgreencapital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/3_bristol_method_how_to_measure_the_sustainability_of_a_city.pdf

- Bristol2015. (2015b). Bristol City Council’s £1m investment into Bristol’s year as European Green Capital 2015.

- Bristol2015. (2015c). Bristol European Green Capital 2015: Citywide review. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/wp-content/uploads/2020/Bristol_2015_Annual_Review.pdf

- Busco, C., Frigo, M. L., Quattrone, P., & Riccaboni, A. (2013). Integrated reporting: Concepts and cases that redefine corporate accountability. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02168-3

- Campos, M. J. Z., & Zapata, P. (2014). The travel of global ideas of waste management. The case of Managua and its informal settlements. Habitat International, 41, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.07.003

- Caperchione, E., Demirag, I., & Grossi, G. (2017). Public sector reforms and public private partnerships: Overview and research agenda. Accounting Forum, 41(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2017.01.003

- Carlin, T. (2000). Measurement challenges and consequences in the Australian public sector. Australian Accounting Review, 10(21), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-2561.2000.tb00064.x

- Cheng, M., Green, W., Conradie, P., Konishi, N., & Romi, A. (2014). The international integrated reporting framework: Key issues and future research opportunities. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 25(1), 90–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/jifm.12015

- Christensen, M. (2005). The ‘third hand’: Private sector consultants in public sector accounting change. European Accounting Review, 14(3), 447–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963818042000306217

- Christensen, M., & Parker, L. (2010). Using ideas to advance professions: Public sector accrual accounting. Financial Accountability & Management, 26(3), 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2010.00501.x

- Christensen, M., & Yoshimi, H. (2003). Public sector performance reporting: New public management and contingency theory insights. Government Auditing Review, 10(3), 71–83.

- CIPFA. (2013, July). Integrated reporting and public sector organisations – Issues for consideration.

- Coulson, A. B., Adams, C., Nugent, M. M. N., & Hayes, K. (2015). Exploring metaphors of capitals and the framing of multiple capitals. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(3), 290–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-05-2015-0032

- Czarniawska, B. (2004). On time, space, and action nets. Organization, 11(6), 773–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508404047251

- Czarniawska, B. (2008). How to misuse institutions and get away with it: Some reflections on institutional theory(ies). In Greenwood,R., Oliver, C., Sahlin , K. & Suddaby, R. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 769–782). Sage.

- Czarniawska, B. (2010). Translation impossible? Accounting for a city project. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23(3), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571011034361

- Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travels of ideas. Gothenburg University – School of Economics and Commercial Law/Gothenburg Research Institute.

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1990). Merchants of meaning: Management consulting in the Swedish public sector. In B. A. Turner (Ed.), Organizational symbolism (pp. 139–150). de Gruyter.

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B., & Sevón, G. (1996). Translating organizational change. Walter de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110879735

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B., & Sevón, G. (Eds.). (2005). Global ideas: How ideas, objects and practices travel in a global economy (Vol. 13). Copenhagen Business School Press.

- de Villiers, C., Rinaldi, L., & Unerman, J. (2014). Integrated reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(7), 1042–1067. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2014-1736

- de Villiers, C., & Sharma, U. (2020). A critical reflection on the future of financial, intellectual capital, sustainability and integrated reporting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 70, 101999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2017.05.003

- de Villiers, C., Venter, E. R., & Hsiao, P. C. K. (2017). Integrated reporting: Background, measurement issues, approaches and an agenda for future research. Accounting & Finance, 57(4), 937–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12246

- Dicorato, S. L., Di Gerio, C., Fiorani, G., & Paciullo, G. (2020). Integrated reporting in municipally owned corporations: A case study in Italy. In F. Manes-Rossi & R. Orelli (Eds.), New trends in public sector reporting. Public sector financial management (pp. 175–194). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40056-9_9

- Dumay, J., Bernardi, C., Guthrie, J., & Demartini, P. (2016). Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.001

- English, L., Guthrie, J., & Parker, L. (2005). Recent public-sector financial management change in Australia: Implementing the market model. In C. Greve, J. Guthrie, O. Olson, & L. Jones (Eds.), International public financial management reform: Progress, contradictions and challenges (pp. 23–54). Information Age Press.

- Erlingsdottir, G., & Lindberg, K. (2005). Isomorphism, isopraxism and isonymism – Complementary or competing processes? In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevon (Eds.), Global ideas: How ideas, objects and practices travel in the global economy (pp. 47–70). Liber and Copenhagen Business School Press.

- European Commission. (2015). European Green Capital award: Memorandum of understanding between The European Commission – Directorate-General for the Environment and Bristol. EGCA Winning City 2015.

- Farneti, F., Casonato, F., Montecalvo, M., & De Villiers, C. (2019). The influence of integrated reporting and stakeholder information needs on the disclosure of social information in a state-owned enterprise. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(4), 556–579. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-01-2019-0436

- Flower, J. (2015). The international integrated reporting council: A story of failure. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 27, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.07.002

- García-Sánchez, I. M., & Noguera-Gámez, L. (2018). Institutional investor protection pressures versus firm incentives in the disclosure of integrated reporting. Australian Accounting Review, 28(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12172

- Gibassier, D., Rodrigue, M., & Arjaliès, D. L. (2018). Integrated reporting is like God: No one has met Him, but everybody talks about Him. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(5), 1349–1380. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-07-2016-2631

- Guthrie, J., Manes-Rossi, F., & Levy Orelli, R. (2017). Integrated reporting and integrated thinking in Italian public sector organisations. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(4), 553–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-06-2017-0155

- Guthrie, J., & Martin-Sardesai, A. (2020). Contemporary challenges in public sector reporting. In F. Manes-Rossi & R. Levy Orelli (Eds.), New trends in public sector reporting. Public Sector Financial Management (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40056-9_1

- Guthrie, J., Olson, O., & Humphrey, C. (1999). Debating developments in new public financial management: The limits of global theorising and some new ways forward. Financial Accountability & Management, 15(3-4), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0408.00082

- Herbohn, K. (2005). A full cost environmental accounting experiment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(6), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2005.01.001

- Higgins, C., Stubbs, W., Tweedie, D., & McCallum, G. (2019). Journey or toolbox? Integrated reporting and processes of organisational change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(6), 1662–1689. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2018-3696

- Himick, D., & Bivot, M. (2018). Carriers of ideas in accounting standard-setting and financialization: The role of epistemic communities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 66(April), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2017.12.003

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(spring), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Humphrey, C., O’Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2017). Re-theorizing the configuration of organizational fields: The IIRC and the pursuit of ‘enlightened’ corporate reporting. Accounting and Business Research, 47(1), 30–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2016.1198683

- IIRC. (2011). Discussion paper “Towards integrated reporting – Communicating value in the 21st century”.

- IIRC. (2012). Summary of responses to the September 2011 discussion paper and next steps.

- IIRC. (2013a). The international integrated reporting framework.

- IIRC. (2013b). The international integrated reporting framework (draft).

- IIRC & CIPFA. (2016). Focusing on value creation in the public sector. Retrieved January 29, 2021, from http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Focusing-on-value-creation-in-the-public-sector-_vFINAL.pdf

- Jupe, R., & Funnell, W. (2015). Neoliberalism, consultants and the privatisation of public policy formulation: The case of Britain’s rail industry. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 29, 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2015.02.001

- Lai, A., Melloni, G., & Stacchezzini, R. (2018). Integrated reporting and narrative accountability: The role of preparers. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(5), 1381–1405. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2016-2674

- Lamb, P., & Currie, G. (2012). Eclipsing adaptation: The translation of the US MBA model in China. Management Learning, 43(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611426533

- Lapsley, I. (1999). Accounting and the new public management: Instruments of substantive efficiency or a rationalising modernity? Financial Accountability & Management, 15(3-4), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0408.00081

- Lapsley, I., & Oldfield, R. (2001). Transforming the public sector: Management consultants as agents of change. European Accounting Review, 10(3), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0408.00081

- Larrinaga, C., Luque-Vilchez, M., & Fernández, R. (2018). Sustainability accounting regulation in Spanish public sector organizations. Public Money & Management, 38(5), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1477669

- Lodhia, S., Kaur, A., & Williams, B. (2020). Integrated reporting in the public sector. In C. De Villiers, P. C. K. Hsiao, & W. Maroun (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of integrated reporting (pp. 227–237). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429279621

- Malsch, B., & Gendron, Y. (2011). Reining in auditors: On the dynamics of power surrounding an “innovation” in the regulatory space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(7), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2011.06.001

- Manes-Rossi, F. (2017). Integrated reporting and the public domain – Engagement with practice. In E. Katsikas, F. Manes-Rossi, & R. Orelli (Eds.), Towards integrated reporting accounting change in the public sector (pp. v–viii) (Foreword). Springer.

- Manes-Rossi, F., & Orelli, R. (2020). New trends in public sector reporting. Public Sector Financial Management. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40056-9

- McElroy, M. W., & Thomas, M. P. (2015). The multicapital scorecard. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-04-2015-0025

- McNally, M. A., Cerbone, D., & Maroun, W. (2017). Exploring the challenges of preparing an integrated report. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(4), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-10-2016-0085

- McNally, M. A., & Maroun, W. (2018). It is not always bad news: Illustrating the potential of integrated reporting using a case study in the eco-tourism industry. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(5), 1319–1348. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-05-2016-2577