ABSTRACT

This paper explores the institutional entrepreneurship process. It focuses on how institutional entrepreneurs implement their vision of accounting change in the Islamic financial reporting standardisation initiatives while providing insights into why these actors may fail in this process. Research findings informed by semi-structured interviews and document analysis demonstrate that institutional entrepreneurs’ attainment of accounting change is subject to their ability to collectively and skilfully frame, promote and institutionalise their entrepreneurial vision, mobilise allies and alleviate the resistance of field’s “incumbents”. The paper contributes to the accounting change literature by expanding our understanding of the determinants of successful accounting change and of how institutional entrepreneurs can effect change in the contemporary accounting system. It also contributes to the ongoing institutional entrepreneurship theorisation by revealing the contingencies through which actors may overcome the barriers to change in highly institutionalised systems.

1. Introduction

Institutional theory is widely used in research on accounting change. Yet, the issue of how the accounting change process occurs remains unclear, particularly in terms of the role of actors and agency. Attempting to overcome the limitations of early institutional theorisation, a growing body of institutional entrepreneurship research has emerged, placing the role of actors and agency at the centre of institutional and organisational analysis (Battilana et al., Citation2009; DiMaggio, Citation1988; Garud et al., Citation2007; Hardy & Maguire, Citation2008; Maguire et al., Citation2004). Scholars have documented the elements that characterise the cases in which institutional entrepreneurs have been successful in implementing change (Garud et al., Citation2002; Maguire et al., Citation2004; Misangyi et al., Citation2008; Thornton et al., Citation2012). Failure to implement change is fairly common (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), especially in mature fields such as accounting, but relatively little attention has been paid to the factors that lead institutional entrepreneurs’ change endeavours to fall through (for exceptions, see Kahl et al., Citation2012; Major et al., Citation2018). Studies in this area tend to convey a “heroic image” of institutional entrepreneurs (Lounsbury, Citation2008; Lounsbury & Crumley, Citation2007), overstating their capacity to successfully implement change and diverting attention from institutional constraints and resistance from the field’s “incumbents”, who act as institutional defenders trying to prevent change.

This paper provides comparative accounts of two initiatives aiming to introduce a framework for Islamic accounting standards. The first involved Islamic financial institutions establishing a standard-setting body named the Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI). The second was initiated by the Malaysian Accounting Standards Board (MASB). While the former project is still pursuing its objectives, the latter has abandoned its initial goals in favour of a standardisation approach that embraces the existing institutional arrangements in the field. In comparing these two initiatives, this paper addresses the following questions: (i) How have actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects emerged and engaged in an institutional entrepreneurship process to create and implement accounting change? (ii) How do institutional entrepreneurs involved in Islamic accounting standardisation succeed or fail in creating, implementing and sustaining their vision of accounting change?

Prior institutional entrepreneurship studies are based primarily on single cases (e.g. Garud et al., Citation2002; Major et al., Citation2018; Munir & Phillips, Citation2005), while multi-case comparative research remains rare (see for exceptions, Lawrence et al., Citation2002; Rothenberg, Citation2007). Battilana et al. (Citation2009) suggest that much can be learned by comparing successful institutional entrepreneurs with those who fail to implement their vision of change. In addition to providing a multi-case comparative analysis that addresses the factors of success and barriers to institutional entrepreneurship in accounting, this paper contributes to the literature by arguing against the “heroic conceptualisation” of institutional entrepreneurs (Dorado, Citation2013, p. 551). This conceptualisation has focused on the dramatic success stories of powerful individuals who can independently change institutions to suit their interests. While the role of the field’s actors has largely been ignored in the literature (Hardy & Maguire, Citation2017), this paper sheds light on the importance of mobilising them. It argues that institutional entrepreneurship is a collective process and unless institutional entrepreneurs attain the support of other actors in the field, or at least alleviate their resistance, their efforts are likely to fail. Moreover, this study contributes to the accounting change literature by exploring the determinants of successful accounting change and how institutional entrepreneurs effect change in the accounting field.

Islamic accounting standardisation projects provide a fascinating context for studying institutional entrepreneurship and accounting change. They are the only standard-setting projects to emerge outside the Anglo-American accounting sphere and aim to develop accounting concepts, guidelines and standards inspired by Islamic business and moral principles (Kamla & Haque, Citation2019). These projects may be considered a “confounding” factor for international accounting harmonisation efforts and a challenge to the “one-size-fits-all” proposition of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) (Hamid et al., Citation1993). It is also interesting to explore institutional entrepreneurship in Islamic accounting standardisation, which has experienced historical heterogeneity in the ways in which Islamic accounting requirements have been approached. Such heterogeneity in empirical settings facilitates a comparative analysis that can provide valuable insights into the initiatives aimed at introducing change through developing a framework for Islamic financial reporting.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review on international accounting standards, accounting change and the emergence of Islamic accounting standardisation initiatives. Section 3 introduces the concept of institutional entrepreneurship in terms of its relationship to Islamic accounting standardisation. The paper moves on to describe the research context and methodology in section 4. Section 5 presents the research findings, followed by a summary and concluding discussion in section 6.

2. International accounting standards, accounting change and Islamic financial reporting

The notion that accounting represents a set of measurement techniques that are isolated from their context is widely challenged (Potter, Citation2005). Accounting is not “unresponsive to changes in the physical world which it seeks to represent” (Hopwood, Citation1990, p. 13). Therefore, shifting patterns of organisational, social and economic life are likely to impact accounting practices and requirements. Such shifts provide a basis for accounting change which aims to provide a new alignment between accounting and the contexts in which it is perceived to be imperfectly embedded (Hopwood, Citation1990). Accounting change is also seen as one of the resources that actors mobilise to support wider organisational and institutional transformation (Baños & Carrasco, Citation2019). In both cases, scholars emphasise recognising the role of individuals who act as change agents in shaping the accounting change process (Haas, Citation1992; Potter, Citation2005). They also stress the importance of understanding the politics within organisations which act as a facilitator of and/or barrier to change (Yang & Modell, Citation2013).

Historically, each country has had its own accounting standards reflecting its particular needs. However, globalisation of the business environment has led to financial statements based on national generally accepted accounting principles (GAAPs) being unable to meet the information needs of investors “whose decisions are more international in scope” (Zeghal & Mhedhbi, Citation2006, p. 373). Consequently, the world has witnessed a large accounting change movement whereby many countries have adopted one set of accounting standards – IFRS. Some countries adopt IFRS to obtain their promised benefits, such as enhancing the comparability and reliability of financial reporting (Zeghal & Mhedhbi, Citation2006), eliminating technical barriers arising from national differences (Nobes & Parker, Citation2012), and reducing information asymmetry (Bova & Pereira, Citation2012). Yet, some scholars believe that IFRS adoption is merely a legitimacy-seeking process carried out under pressure exerted by international agencies, regardless of local needs (Judge et al., Citation2010). Therefore, prior literature raises the question that, given the economic, legal, political, cultural and even religious differences between nations, can IFRS be considered a suitable reporting framework for all countries?

Accounting is a product of its environment (Al Mahameed et al., Citation2021; Cooke & Wallace, Citation1990). Accounting practices in each nation have developed to reflect local socio-economic environment and requirements. However, “[t]his balance of interests which has worked out over many years is set aside by the harmonisation process which must by definition be working towards a common set of rules” (Walton et al., Citation2003, p. 10). This argument raises another question about the way in which nations can obtain the benefits of international accounting harmonisation while considering their own needs simultaneously. It is important here to acknowledge that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution, given the differences between nations. Scholars have documented national attempts to amend IFRS to address local needs (Felski, Citation2017; Nobes & Zeff, Citation2008). Countries also have the opportunity to have their voices heard through lobbying and/or working collaboratively with the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) to accommodate their needs in its standards (Bischof et al., Citation2014). This implies that, in all cases, accounting change is required to adapt IFRS and accommodate national accounting differences.

Religion is one of the factors that trigger differences in the accounting practices between nations (Dyreng et al., Citation2012; Hamid et al., Citation1993; McGuire et al., Citation2012). Islam, among other religions, “has the potential for influencing the structure, underlying concepts and the mechanisms of accounting” (Hamid et al., Citation1993, p. 131). The concept of “Islamic accounting” emerged to generally examine the reporting practices from an Islamic perspective. However, it has been closely linked to the Islamic finance industry, which obtains its legitimacy from the promise that its activities comply with ShariaFootnote1 rulings, which makes it attractive to Muslims (Gambling et al., Citation1993). Financial reporting is considered an important tool for Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) to communicate Sharia compliance with stakeholders. In this regard, Nasir and Zainol (Citation2007) argue that although western accounting standards and practices are useful in providing a structural framework for IFIs’ financial reporting, they do not address Islamic accounting requirements and are not able to fully capture the contractual aspects of Islamic financial products. Recognising the importance of financial reporting for IFIs as a communication tool and the implications of Sharia for their accounting practices, ambitious projects for developing Islamic accounting standards have been established. Some projects were started by national accounting bodies while others were initiated through the establishment of international bodies (e.g. AAOIFI).

3. Islamic financial reporting standardisation: institutional change and entrepreneurship

The actors who have initiated Islamic accounting standardisation have employed innovative approaches through which they have examined the objectives, concepts and principles of conventional accounting against Sharia, accepting those that are consistent with its principles, eliminating inconsistences and introducing new objectives and practices when necessary (Ibrahim & Yaya, Citation2005; Karim, Citation1995; Lewis, Citation2001). These actors have been exposed to various institutional logics in the societal sectors to which they belong. For example, they are part of the accountancy profession and have a firm background in Sharia and Islamic finance, in addition to being influenced by their society’s norms and values. This exposure gives them the capacity to realise and utilise the elements of these institutional logics in an innovative way to initiate change (see Thornton et al., Citation2012). Adopting this argument, this paper explores how these actors have taken advantage of their awareness of and involvement in different institutional settings to initiate accounting change and establish a framework for Islamic financial reporting.

The concept of institutional entrepreneurship was introduced by DiMaggio (Citation1988) to address the neglect of agency in the early articulations of institutional theory. While early institutional theorisation focuses on the constraints under which actors operate, institutional entrepreneurship studies explore the opportunities that enable them to exercise agency and create change. Actors who strategically mobilise resources to initiate change that transforms existing institutional structures or creates new ones are termed “institutional entrepreneurs” (DiMaggio, Citation1988). The concept of institutional entrepreneurship has been widely adopted by studies addressing institutional change in various fields, including accounting (e.g. Ahrens & Ferry, Citation2018; Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Major et al., Citation2018; Munir & Phillips, Citation2005; Sánchez-Matamoros & Fenech, Citation2019).

Although understanding of institutional entrepreneurship conditions is well developed, there is still a lack of knowledge about how such processes take place and how institutionalisation is achieved (Yang & Modell, Citation2013). The institutionalisation of change has been largely addressed as an outcome rather than a process (Scott, Citation2013). Institutional entrepreneurship has mostly been analysed in terms of the characteristics that produce institutional entrepreneurs rather than what they actually do and how they systematically organise their efforts to implement change (Levy & Scully, Citation2007). This paper addresses this gap and examines the process of institutional entrepreneurship in Islamic accounting standardisation projects. It aims to explore how the actors involved in these projects have engaged in certain entrepreneurial activities to implement and promote their vision of accounting change. It also seeks to identify the factors that explain why some institutional entrepreneurs are able to implement change successfully while others fail in sustaining their vision of change.

Institutional entrepreneurs create opportunities for institutional change by exploiting cultural discontinuities (Thornton et al., Citation2005) and take advantage of institutional contradictions to further their interests (Seo & Creed, Citation2002; Thornton et al., Citation2012). Formal positions in organisational hierarchy and informal social networks provide these actors with legitimacy and increase their ability to mobilise resources and engage in change (Battilana, Citation2006; Battilana et al., Citation2009). Moreover, their multiple embeddedness in different institutional structures increases their awareness of different alternatives, which provide opportunities for agency and entrepreneurship (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Thornton et al., Citation2005, Citation2012). Institutional entrepreneurs, who are aware of the “modularity” of institutional elements, innovatively deconstruct, switch and recombine them in hybrid ways to create change (Ezzamel et al., Citation2012; Thornton et al., Citation2012). This implies that institutional entrepreneurship is, to a great extent, a recombination of “existing materials and structures, rather than ‘pure’ novelty” (Hwang & Powell, Citation2005, p. 180).

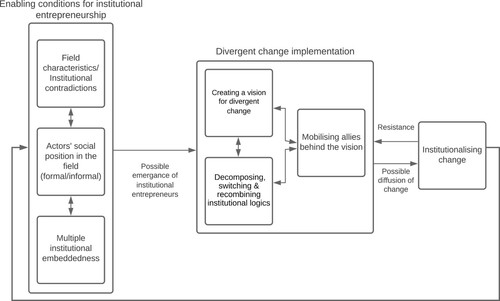

This paper uses Thornton et al. (Citation2012) theorisation on how institutional entrepreneurs initiate change through re-combining institutional elements, benefiting from the incompatibilities in their institutional environment. It examines the efforts made by the actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects to establish an appropriate composition of institutional elements in order to develop an Islamic accounting framework. It explores how these actors employ field characteristics and take advantage of their position and exposure to various institutional logics to initiate accounting change. Furthermore, in order to gain greater understanding of the process of change implementation, this paper extends its analysis by using Battilana et al. (Citation2009) theoretical remarks. They propose a model to explain the process of institutional entrepreneurship, starting from the emergence of institutional entrepreneurs, moving to the implementation of change and ending with change institutionalisation. In their model, they identify three sets of activities that institutional entrepreneurs undertake to implement change: developing a vision of the need for change; mobilising people to gain support and acceptance of the new practices; and motivating others to achieve and sustain the vision of change.

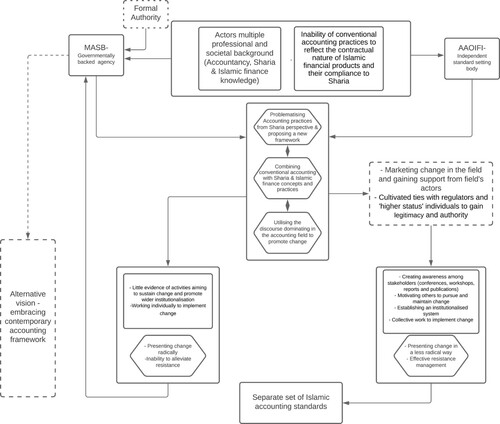

Combining Thornton et al. (Citation2012) and Battilana et al. (Citation2009) theorisation remarks (see ) helps to explain what institutional entrepreneurs do and to make predictions about the ability of emerging institutional entrepreneurs to survive. By using this theoretical framework to analyse the events experienced by Islamic accounting standardisation projects, this paper provides insights that answer the following research questions:

How have actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects emerged and engaged in an institutional entrepreneurship process to create and implement accounting change?

How do institutional entrepreneurs involved in Islamic accounting standardisation succeed or fail in creating, implementing and sustaining their vision of accounting change?

Figure 1. Process of institutional entrepreneurship (Source: adapted from Battilana et al. (Citation2009) and Thornton et al. (Citation2012)).

4. Research context and methodology

4.1. Research context

This paper provides comparative accounts of two initiatives aiming to introduce a framework for Islamic financial reporting. In doing so, it uses a qualitative research approach that aims to investigate the phenomenon in its real-life settings (Yin, Citation2014).

4.1.1. Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI)

Based in Bahrain, the AAOIFI was established in 1991 by IFIs with the purpose of preparing accounting, auditing and governance standards based on Sharia precepts (Karim, Citation2001). Prior to the AAOIFI’s establishment, IFIs, as newly emerging institutions, could not find a complete match between conventional accounting standards and the characteristics of Islamic financial products. Consequently, each IFI developed its own accounting practices (Karim, Citation1990). This resulted in different practices being followed by different institutions, which affected IFIs’ financial reporting comparability and credibility (Karim, Citation1999). Therefore, they took the initiative to harmonise their accounting practices and established the standard-setting body of AAOIFI.

Since its establishment, the AAOIFI has experienced considerable success in terms of growing membership and the standards it has developed. The AAOIFI’s membership has expanded to include more than 200 IFIs, supervisory authorities, professional bodies and accounting firms from 40 countries. It has issued 26 accounting standards in addition to other auditing, Sharia and governance standards which have been implemented as either mandatory or voluntary requirements. Some regulatory bodies have also used them as a basis for developing national standards.Footnote2 In this context, given that the AAOIFI has no power of enforcement, it has adopted a marketing strategy that aims to establish collaborative relationships with national regulatory bodies (Karim, Citation1990, Citation2001). The strategy also involves disseminating its thoughts through organising conferences, issuing reports and providing professional training programmes and certification.

4.1.2. Malaysian Accounting Standards Board (MASB) project for developing Islamic accounting standards

At first, Malaysia supported the AAOIFI project. Yet, due to differences in local Islamic finance practices as well as the regulatory and economic structure in Malaysia, local standards were needed (Nasir & Zainol, Citation2007). Therefore, in 1997, the MASB initiated a standardisation project, which aimed to develop accounting standards for IFIs in the first instance. However, the project, in contrast to the AAOIFI’s objectives, aimed to extend its focus at a later stage to develop standards for all entities operating according to Islamic business principles. In 2000, the MASB’s executive director ambitiously stated in a press release that its Islamic standards could also become applicable to other countries. This makes the MASB’s project an interesting case for investigation as it was considered to be in competition with the AAOIFI at the time.

The MASB issued its first Islamic standard in 2001. In 2004, it announced that four more standards would be issued but it then changed that plan and, in 2006, published technical releases instead. In 2009, the MASB issued a Statement of Principles, which withdrew the first and only Islamic standard and required IFIs to follow the Malaysian approved accounting standards. However, it decided to continue issuing technical releases on Islamic financial reporting matters. This strategy was eventually abandoned, with the MASB plan for full convergence with IFRS in 2012. Instead, the MASB indicated that it would consider alternative routes to accommodate Islamic accounting needs, including “lobbying” the IASB to accommodate these needs within the IFRS framework.

It can be argued that, by selecting these two cases, this study delivers insightful comparisons between two extreme cases. The first is still pursuing its vision to develop Islamic accounting standards, while the second has abandoned its initial objectives of developing separate Islamic accounting standards in favour of a standardisation approach that aims to accommodate IFIs’ accounting needs within IFRS. Historically, both projects followed a standardisation strategy that aimed to utilise existing conventional accounting objectives, principles and practices, evaluate them against Sharia and adapt them to meet IFIs’ reporting demands (Ibrahim & Yaya, Citation2005; Karim, Citation1995; Lewis, Citation2001). This implies that, in addition to Sharia requirements and IFIs’ reporting needs, both projects gave consideration to international accounting requirements in developing their framework (Kamla & Haque, Citation2019; Nasir & Zainol, Citation2007). The influence of these requirements has recently increased with the global movement to follow IFRS, regardless of local accounting needs. Accordingly, the MASB adopted the policy of accommodating Islamic accounting requirements within IFRS. On the other side, the AAOIFI announced in 2015 that it would work on “bridging the gaps” between its standards and IFRS in areas that did not conflict with Sharia. Nevertheless, the AAOIFI stressed that this would not be at the expense of sacrificing its fundamental objectives in developing standards that reflect Sharia features and requirements (Abras & Jayasinghe, Citation2019).

4.2. Data collection and analysis

The data collection involved conducting interviews with 21 participants (see Appendix A). The “purposive” sampling technique was used for selecting interviewees (Saunders et al., Citation2012), based on their involvement in or the links they have with the standardisation projects. Accordingly, the study approached standard setters and committee members who are knowledgeable of the organisational context of the projects. In addition, the study approached “outsider” participants, including Sharia advisors, regulators, bankers, academics and practitioners. Interviewees were asked questions that aimed to identify and investigate the efforts made and strategies followed by the actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects in order to create, frame and promote their standardisation approach and mobilise support for it. Interviewee data was anonymised. In addition, the researchers followed the ethical guidelines and standards of their institutions, including obtaining ethical approval and interviewees’ informed consent prior to interviews.

Documentary evidence was also used, including press releases, announcements, executive statements, and the historical details available in the publications of the accounting standard-setting bodies and their websites. These documentary sources were important for analysing how Islamic accounting standardisation projects communicated their standardisation approach with stakeholders. They also helped identify the key actors and events in the projects and the changes they experienced. Other secondary data were used as additional sources of historical and contextual information, including information from the prior literature on Islamic accounting standardisation (e.g. Karim, Citation1990, Citation1995, Citation2001; Nasir & Zainol, Citation2007) and YouTube materials, such as AAOIFI conferences and media coverage. This data triangulation improved the validity and reliability of findings and ensured that data were analysed in the right context (Yin, Citation2014).

A combination of analytical strategies was used, consistent with the nature, theoretical framework and research questions of the study. First, the data were organised chronologically in order to identify important events and actors. Next, thematic analysis of the data was performed based on theoretically informed themes (e.g. contextual conditions of institutional entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship processes, institutional background of actors, change approaches, change framing, mobilising allies, promoting vision using discourse, change institutionalisation, change resistance and non-divergent change efforts). NVivo software was used to facilitate this analytical stage. Finally, theoretically informed analysis was developed in which links were established between different events, actors, themes and narratives. At this stage, the findings derived from both standardisation projects were compared, contrasted and synthesised to address the research questions.

5. Research findings

5.1. Institutional entrepreneurship in Islamic financial reporting standardisation projects: the role of context and actors in institutional change

This section addresses the question of how actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects have emerged and engaged in an institutional entrepreneurship process to create accounting change. In doing so, it examines the contextual and institutional circumstances surrounding the emergence of Islamic accounting standardisation projects and how actors involved in these projects have benefited from their multiple institutional backgrounds to effect change. It also explores the change processes followed by these actors in an attempt to address the accounting needs of the newly emerging IFIs.

A number of Islamic finance practitioner interviewees told the story of the emergence of the Islamic finance industry. They stated that the pioneers of the industry had recognised the incompatibility of conventional banking with Islamic business rules. This incompatibility led Muslims to refrain from dealing with conventional banks. Islamic finance pioneers responded by creating innovative combinations between conventional banking instruments and Islamic business principles in order to develop banking tools that comply with Sharia. These actors achieved considerable success over time although initially they found it difficult to convince regulators of the credibility of their movement.

A similar scenario had arisen in the context of IFIs’ financial reporting when there was a lack of clarity in how to account for the transactions due to the inability of conventional accounting practices to reflect the contractual nature of IFIs’ products and their compliance with Sharia.

… the needs of the stakeholders of Islamic banks are different … [Therefore], their needs for information will definitely be different. It is not restricted to the normal conventional western way of accountability. It is very much horizontal accountability … accountability to God, which requires certain information to be provided in a more transparent manner, more comprehensive manner. (I-10, standard setter)

Similar initiatives were subsequently adopted by national accounting bodies such as the MASB, whose project was initiated by a government-backed body. Therefore, in addition to addressing Sharia demands and IFIs’ reporting needs, the project was under the pressure of working in line with the national general policy and regulatory requirements. According to a Malaysian regulator, these policies reflected community demands of embracing Islamic values:

In [the] 1980s–1990s, following the so-called revivalism, there were requests from the society for the government to practice some Islamic way of life … we were not able to accommodate everything; however, there were certain efforts by our scholars, our leaders, to enact a few regulations. (I-14)

The impact is that Malaysia has been recognised as one of the promoters of Islamic banking … I think there was a great intent at the country-level to develop Sharia-compliant activities; there were laws that were amended in order to facilitate Islamic banking … that desire must be translated into whatever is necessary in order to cope that desire, including coming up of Islamic accounting standards. (I-2)

Our policy now adopts a more liberal position. Globalisation has changed everything. Our policies aim to integrate the country in the global business environment. (I-14)

AAOIFI consults [regulators] whenever it does an exposure draft, particularly in the technical areas; it approaches the regulators and takes their concern … but if you are talking about influencing, I doubt that AAOIFI will be influenced by one regulator because it has to work with multiple countries and multiple jurisdictions. (I-7)

The entrepreneurial initiatives of the AAOIFI and the MASB were motivated and enabled by two factors. The first was the incompatibility of conventional accounting practices with IFIs’ accounting requirements. Institutional conflict reveals new opportunities for innovation since actors exposed to contradictory institutional arrangements are less likely to take these arrangements for granted. Instead, they tend to question and diverge from them (Battilana et al., Citation2009). On the ground, this incompatibility has motivated actors involved in IFIs’ financial reporting to challenge the prevailing accounting system and attempt to develop appropriate accounting practices for IFIs. The second enabling factor was the exposure of the actors involved to different institutional settings. Interviewing and reviewing the profiles of these actors reveals that they were initially part of the conventional accountancy profession. Simultaneously, they had considerable Sharia knowledge and well-established experience in Islamic banking. This multiple exposure increased their awareness of the alternatives available in their environment, giving them the capacity to use these alternatives and create innovative solutions through segregating and combining different values, principles and practices in their complex institutional context in an innovative way.

5.2. Institutional entrepreneurs, implementation of change and divergent change resistance

This section addresses the question of how institutional entrepreneurs involved in Islamic accounting standardisation succeed or fail in creating, implementing and sustaining their vision of accounting change. It examines the process of change implementation and analyses how and why actors in the AAOIFI have pursued their vision of developing Islamic accounting standards while those in the MASB did not achieve theirs. In doing so, it investigates the efforts made by these actors to frame their vision of change, mobilise allies behind it, and institutionalise it. Understanding these activities is crucial in order to comprehend the drivers of success in institutional entrepreneurship and to explain the heterogeneity between actors in the AAOIFI and the MASB in their ability to achieve their objectives. It is also important to understand change resistance and how actors who have recently been involved in the MASB have succeeded in promoting their counter approach (accommodating Islamic accounting needs in the IFRS framework) at the expense of the previous approach (developing separate standards). Hence, this paper provides an additional layer of comparison between the implementation of the former and current standardisation approach of the MASB.

5.2.1. Creating a vision for change

Given that change promoted by institutional entrepreneurs tends to break with institutional arrangements in a field, they frame their vision for divergent change in a way that appeals to the field’s actors and motivates them to implement it (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Commenting on the importance of vision framing, a standard setter stated:

It is all about how you lobby; it is about how you sell your idea, rather than how technical the standards [are]. (I-12)

The nature of transactions is different. The business relationship is different … In terms of the legal forms, it is different. In terms of substance, there are some similarities in substance; yet the form is different … It is not enough to look at the similarity between some conventional and Islamic products … In Islamic financial transactions, if you do not reflect the legal form you are not reflecting true things … there are recognition and measurement issues … Specific Islamic financial products need specific accounting treatments. (I-10)

I think what should be in Islamic banks is, rather than you report only the profit maximisation … I would also like to see welfare reporting, what they have done to the society … This is what we expect Islamic institutions to disclose to the market, which is not found in the existing requirement because it is not required by IFRS. (I-15, professor of accounting)

AAOIFI standards are intended to enhance the confidence of users of the financial statements of Islamic financial institutions in the information that is produced about these institutions, and to encourage these users to invest and deposit their funds in Islamic financial institutions and to use their services. (p. 13)

5.2.2. Mobilising allies

Most interviewees emphasised the importance of attaining the support of actors in the field when introducing an accounting framework that deviates from common practices. The findings reveal two approaches to mobilising allies: the first uses discourse while the second uses social networks to gain support for new practices.

5.2.2.1. Mobilising allies using discourse

Several interviewees referred to the difficulty of promoting change in a highly institutionalised field such as accounting.

… when you develop standards and you want your standards to be implemented, you have to work within the general requirements of the regulators. If you depart from the norms, then people are not going to use your standards. (I-3, academic and standard setter)

Globally, IFRS are getting the real status of an accounting bible. They are taking the role of the divine guidance for [the] accounting fraternity.Footnote3

5.2.2.2. Mobilising allies using social networks

Research findings indicate that the AAOIFI’s actors have made considerable efforts to obtain the support of stakeholders, including regulators, practitioners, bankers and academics. These actors have used their social and professional networks to promote the AAOIFI’s approach and mobilise allies. Moreover, they have created links with individuals of higher status in an attempt to gain advantage from their social position. A former standard setter indicated that the AAOIFI was able to obtain the support of prominent bankers, businesspeople and politicians at an early stage and suggested that this support helped the AAOIFI promote its initiative widely at that critical stage.

Social position in a field can also be attained from formal authority, which not only enhances actors’ ability to implement change, as they have the power to enforce decisions, but also legitimises change from the perspective of the field’s actors (Battilana et al., Citation2009). The AAOIFI was established as an independent standard-setting body, implying that its actors had no formal authority to implement their standards. However, AAOIFI actors have followed the strategy of approaching regulatory bodies to promote its standards. In doing so, they have successfully cultivated ties with organisational and individual actors who possess formal authority to overcome their own deficiencies in this area. A standard setter stated:

… [The AAOIFI is] increasing [its] outreach and collaboration with regulators; [it is] increasing marketing and awareness efforts; not only this, [it has] included more regulators and more accounting standard-setting bodies and more accounting associations in [its] technical boards … [The AAOIFI] secretariat is making significantly more effort in approaching regulators. (I-7)

In the last few months, we have visited more than 25 central banks and regulatory bodies in four [continents]. Our visits involved introducing AAOIFI, its standards and activities, providing technical and professional support and organising workshops and training [for] their staff. These efforts have successfully resulted in some of these regulatory bodies officially joining AAOIFI and negotiating the adoption of its standards.

Within the Malaysian context, the group of actors who initiated the MASB Islamic accounting standardisation projects possessed the formal authority that gave a high degree of legitimacy to their vision. Nevertheless, a number of Malaysian interviewees stated that these individuals lacked the capability of mobilising allies and marketing change. An interviewee who was involved in the early stages of that project referred to this issue:

It depends on the leadership … You need strong figures to sell the idea … You need strong supporters to support the leader who can bring change. We did not have that, so all efforts collapsed. When you promote something, you have to do your study, you have to look at the institutional players. If you want to win the battle, you must have a strong foundation, strong supporters. Then, you can move forward. (I-12)

5.2.3. Institutionalisation of change

Research findings indicate that AAOIFI actors have made considerable efforts not only to mobilise allies behind their initiative but also to create awareness among stakeholders of the importance of their vision. This is intended to sustain their vision while also making sure that it becomes a way of thinking, which motivates others to pursue change. Promoting and raising awareness activities took different forms, including organising conferences, conducting workshops, issuing reports and formal visits to regulatory bodies. Raising awareness through dissemination was communicated as one of the main objectives of the AAOIFI, highlighting the importance that AAOIFI actors placed on such activities:

… to disseminate the accounting, auditing, governance and ethical thought relating to the activities of Islamic financial institutions and its application through training seminars, publication of periodical newsletters, preparation of reports, research and through other means.Footnote4

You can have different periods. In some periods the performance could be good or bad, but what I would say, the institution should not be counted only with one person. Yes, [the first secretary-general] was a super guy and he co-formed this institution but the institution even survived after him, [the AAOIFI] developed [a] good [number of] standards after him. (I-7)

Moving to the Malaysian context, the MASB actors were ambitious in their objectives. They set due process and created a working group involving regulators, academics, practitioners and bankers. Yet, research findings show that, unlike the case of the AAOIFI, there is little evidence of activities aiming to promote wider institutionalisation of their approach. By contrast, some interviewees commented that the MASB objectives at that time were presented in a way that made actors in the field perceive it as a personal agenda rather than a national project. Commenting on the efforts made by one of the actors in the project, a former standard setter explained:

He was not able to mobilise people … People were less supportive. While he pursued [a] bigger agenda, people saw that it was personal agenda … That is very unfortunate. (I-10)

He did a good job when he came up with [the] Islamic reporting [project]; then the crisis started. If he had got strong support from others in the industry, I think he could have gone far … It is just about the strategy in the market. If you want to come up with something big, you cannot go there alone. Even though externally you have a big body, when you go, you need to go big … You must come in a group, not individually. (I-12)

Interestingly, research findings reveal that actors who established an alternative approach that aimed to incorporate Islamic accounting needs within IFRS were capable of working collectively to institutionalise and disseminate their counter approach, not only locally but also internationally. This was achieved through organising workshops, issuing reports and publications and creating links nationally and with regional and international bodies to promote their alternative vision. They benefited in this regard from the recent international developments in the accounting field represented by the wide acceptance of IFRS. Quoting from the MASB’s chairperson statements:

Promoting the adoption of IFRS within Islamic banking has been of particular importance to the MASB. (MASB chairperson statement 2011)

As the lead country for the AOSSG Islamic finance working group, we had produced a research paper on the use of IFRS to account for Islamic financing transactions, following our review of financial statements of 132 Islamic financial institutions from 31 jurisdictions. This was presented to AOSSG and IASB members in Hong Kong. (MASB chairperson statement 2014)

They have conducted seminars talking about how IFRS can be used for IFIs. They also try to give their viewpoint on why they think these issues are okay and there are no really Sharia issues … they try to somehow inform the users that they are trying to do something … that they are also concerned about all the challenges in applying [IFRS] for IFIs and that they really work hard in resolving the issues. (I-15, professor of accounting)

5.2.4. Divergent change resistance

Institutional entrepreneurs face political opposition from the actors who benefit from the current institutional arrangements, especially if the proposed change threatens their position in the field (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Resistance of change has been widely observed in both MASB and AAOIFI contexts. The impact of this resistance has increased with the movement to adopt a globalised set of accounting standards. This resistance has resulted in the AAOIFI struggling to obtain acceptance of its standards. However, the consequences of this resistance were greater in the MASB context, leading to dramatic shifts in the approach followed by its actors. This eventually resulted in the abandonment of their initial vision of developing separate Islamic accounting standards.

Actors whose ideas diverge from existing institutional concepts need to be less radical in presenting their vision in order to alleviate reactions of fear among potential allies (Battilana et al., Citation2009). AAOIFI actors have been successful in presenting their vision in a way that does not totally contradict current institutional arrangements. They have emphasised that the AAOIFI develops standards to accommodate IFI reporting issues only and does not intervene in areas that do not involve Sharia concerns. Conversely, it may be observed that MASB actors were more radical in presenting their vision. For instance, in its press releases, the MASB declared that:

[The] MASB will be the first to develop Islamic accounting standards within the region, and once developed the standards may be applicable to other countries like Brunei and Indonesia. (press release dated 14 November 2000)

We want Islamic accounting standards to have the same high standard of due diligence and credibility as the accounting standards accepted by the International Accounting Standards Board. (press release dated 4 March 2004)

It is interesting to observe that the opponent actors in the MASB were skilled in framing a counter vision. They were also able to effectively promote their counter vision and mobilise allies. They benefited in this regard from the national economic liberalisation policies in Malaysia that enabled them to develop a strong discourse promoting the application of the “globalised” framework of IFRS. This discourse defended the neutrality, practicality and applicability of the contemporary accounting framework to IFIs’ financial reporting.

They [the MASB] will go all out and they will say to whoever proposes Islamic accounting, “Where is our standard going wrong? Tell us”. This is the argument during our meetings. If you can prove that the standards are wrong, then they will buy your idea. If not, they will not move even a single inch. (I-12)

If you are talking about business, business is set up with the view of making profit. Accounting is there to reflect what this business will make, but it does not necessarily mean that there are two separate [types of] companies, Islamic and non-Islamic, because, to us, business is business … We do not see a need for a different set of standards. We have very compelling reasons not to have different standards. (I-1)

Islamic transaction is based on a contract. As long as the contract is done based on the Sharia requirement, how you write the transaction in your book will not affect the validity of the contract … Since it does not affect the validity of the contract, let us look [at] how to accommodate, how to record within the existing framework. (I-3, Sharia scholar and member of the MASB standing committee on Islamic financial reporting)

We always challenge ourselves on what extent IFRS can reflect the actual substance or the structure of the Islamic finance product. Most of the time we are able to find an acceptable accounting treatment in the IFRS as well … even if the accounting requirements of the IFRS do not 100% capture the transaction, you can always address that by having additional disclosure to describe the actual arrangements. (I-4, member of the MASB’s standing committee on Islamic financial reporting)

6. Summary and concluding discussion

Developing an Islamic financial reporting framework implies initiating change within the contemporary prevailing norms and practices that have been generally accepted in the accounting field. This paper contributes to the accounting change literature by providing insights into the determinants of successful accounting change and how institutional entrepreneurs can effect change in the contemporary institutionalised accounting system. The paper also contributes to institutional entrepreneurship research by providing comparative accounts of two cases of institutional entrepreneurship in the field of Islamic accounting standardisation. It uses the institutional entrepreneurship theoretical remarks of Thornton et al. (Citation2012) and Battilana et al. (Citation2009) to present an analysis that addresses the research questions: (i) How have actors involved in Islamic accounting standardisation projects emerged and engaged in an institutional entrepreneurship process to create and implement accounting change? (ii) How do institutional entrepreneurs involved in Islamic accounting standardisation succeed or fail in creating, implementing and sustaining their vision of accounting change? Through its engagement in such complex narratives, the paper contributes to the ongoing institutional entrepreneurship theorisation (Battilana, Citation2006; Battilana et al., Citation2009; Dorado, Citation2005; Garud et al., Citation2007; Hardy & Maguire, Citation2008, Citation2017; Major et al., Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2012; Tracey et al., Citation2011) by revealing the contingencies through which actors may overcome barriers to change in highly institutionalised systems.

Answering the first research question, the paper shows that actors involved in the Islamic accounting standardisation projects have responded to the contradictions in their institutional environment and the inability of conventional accounting practices to fully reflect Islamic financial products. They have benefited, in their response, from their exposure to multiple institutional logics and have initiated innovative combinations of the elements of these logics to develop a framework for Islamic financial reporting. The actors have been involved in certain activities and mobilised resources strategically in order to implement their framework. These activities include framing a vision of change to justify the divergence from prevailing accounting practices and obtain the endorsement of other actors in the field; using social position (formal and informal) to mobilise allies; using discursive and rhetorical strategies that relate accounting change to the values and interests of other actors in the field; and motivating others to embrace and sustain the vision of change.

Aiming to answer the second research question, the paper has conducted a comparison between the AAOIFI and the MASB in terms of the activities undertaken to implement and promote their approach. The comparison suggests that AAOIFI actors were more experienced than those of MASB in presenting their vision, mobilising resources and allies to support it and institutionalising its outcomes. Although the AAOIFI was initiated by a few actors who demonstrated passion in pursuing their objectives, they did not work in isolation, but benefited from their social positions, established effective networks and worked with other influential actors in the field to implement their aims. In other words, they used their social skills to exercise collective institutional entrepreneurship. Moreover, they disseminated their approach in the field and established an institutionalised system through which their initial vision could be pursued by their successors. In comparison, MASB actors appeared unable to institutionalise their standardisation vision or mobilise allies, resulting in the collapse of that vision once the key actors had left the organisation. Their replacements did not show the same dedication to that vision and consequently devised an alternative approach that embraced prevailing institutional arrangements under conventional accounting standards.

The paper has extended its comparative accounts in this regard to document and compare the actions of MASB actors who aimed to develop separate accounting standards (divergent change) with the actions of those who promoted an alternative approach that embraced IFRS (non-divergent change). This comparison, which has been insufficiently researched (Battilana et al., Citation2009), provides further understanding of the barriers facing institutional entrepreneurs, as the actors who resist divergent change contribute to the failure of change implementation by challenging institutional entrepreneurs’ vision and promoting other alternatives. Our findings indicate that both projects have faced resistance from other actors in the field. However, while AAOIFI actors have been successful in following certain strategies to alleviate the impact of resistance, MASB actors were unable to successfully meet that challenge. This may be attributed to: (i) the inability of MASB actors to frame and promote their vision of change in a less radical way to alleviate the fear of change among other actors in the field; and (ii) the skilful approach that has been followed by the resistant actors in promoting and institutionalising their counter vision.

It is worth noting here that Islamic accounting standardisation projects have tried to combine institutional elements that demonstrate compatibilities as well as contradictions, given that some conventional accounting concepts and principles are acceptable from the Islamic viewpoint while others are not. In this context, Thornton et al. (Citation2012) expect that institutional logics that are more compatible with each other would have greater transposition capacity between their elemental categories than those logics that are in conflict. This implies that the institutional logics combined in the Islamic accounting standardisation projects (i.e. conventional accounting and Islamic finance/Sharia principle) are not expected to demonstrate full transposition capacity. This could create another form of institutional disruption (Thornton et al., Citation2012), which might trigger another round of change if combined with the inability to promote, maintain and institutionalise the proposed change. This was observed in the MASB standardisation project, where the inability of actors to manage the contradictions, promote the vision of divergent change and institutionalise it led to a new round of change that embraced the prevailing institutional arrangement in the field (see ).

The findings presented in this paper demonstrate the crucial role of social position and skills in initiating and promoting change in the field of accounting. This field has been dominated recently by globalised standards and practices that are defended by international accounting bodies (e.g. IASB) and local coalitions (Kamla & Haque, Citation2019) who label any dissident voices advocating change as aberrant. Accordingly, this study concludes that initiating accounting change first requires creating a well-framed vision of change or, in other words, an alternative culture of reporting. Successfully framing this vision relies on communicating its superiority and disseminating the advantages of the proposed change (prognostic framing) in order to make it attractive to the stakeholders in the field and therefore alleviate resistance. Second, accounting change implementation requires actors to approach power centres and other influential actors in the field. This in turn requires the development of an effective political and social network that collectively embraces, defends and sustains the new vision and reporting culture. These two elements constitute the dividing line between success and failure of institutional entrepreneurship in accounting.

Institutionally, the contextual difference between the AAOIFI and the MASB has an impact on actors’ ability to implement their standardisation vision. The MASB standardisation project was backed by national regulatory bodies. The MASB actors benefited previously from the national tendency to support the Islamic finance industry. However, recently, as a result of national economic liberalisation policies as well as the global movement to adopt IFRS, the MASB came under national institutional pressures to follow IFRS. This made it more difficult for the MASB actors who initiated the Islamic accounting standardisation project to defend their initial vision. They found that they were unable to divert from overall national policies and regulatory requirements aimed at adopting international “accounting best practices”. These practices were supported on the ground by actors who resisted the policy of developing separate Islamic accounting standards and were able to supplant it with an approach that embraced IFRS. Conversely, AAOIFI actors did not experience direct national institutional pressures. In addition, although they announced a plan to address the “unnecessary gaps” in relation to IFRS, they stressed that they would not sacrifice their fundamental objective of developing standards that reflect Sharia features and requirements (Abras & Jayasinghe, Citation2019). In doing so, they were successful in establishing the AAOIFI as an independent standard-setting body despite IFRS convergence pressures.

This paper contributes to the debate on institutional change by looking more sceptically than the prior institutional entrepreneurship literature at the possibilities of achieving divergent change through a handful of actors. It shows that the “heroic conceptualisation” (Dorado, Citation2013, p. 551) of institutional entrepreneurs, which introduces them as “extraordinary species who are increasingly endorsed with special qualities normal actors do not possess” (Meyer, Citation2006, p. 732), is not realistic. Institutional entrepreneurship is seeded by an individual’s ideas; however, these ideas perish if they are not disseminated, promoted and backed by allies who work collectively to implement them. Unless institutional entrepreneurs work collectively with other actors in the field and obtain their support and endorsement, they are less likely to succeed. The actors who initiated the MASB project could not sustain their approach as they did not motivate other actors to embrace it. In contrast, the AAOIFI continues to pursue its objectives through an institutionalised system, which was established by collaborative actors who worked collectively with others in the field to achieve their vision. This demonstrates that the institutional entrepreneurship process goes beyond the agentic power of individuals and, thus, this paper adds to the calls for a theoretical shift from individual to collective institutional entrepreneurship when studying processes that introduce divergent change (Biygautane et al., Citation2019).

While this study provides valuable insights into the importance of working collectively with other actors in the field in order to achieve successful implementation of change, its investigation of the institutional entrepreneurship process is limited to the efforts made by the key actors involved in the change projects. It does not specifically elaborate on actions taken by other actors in the field and how they have contributed to the success (or failure) of these projects. In other words, it does not investigate the process of institutional entrepreneurship from the perspective of those peripheral actors. Institutional entrepreneurship research would benefit from further empirical research dedicated to capturing the roles of these other individual and organisational actors who facilitate institutional entrepreneurs’ efforts through being involved actively – or even passively by not resisting change – in the change process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the cooperation extended by the participants of this study. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the Alternative Accounts Europe Conference at Leicester University, UK, January, 2020. Thanks to the participants for their comments on the paper. We would also like to thank the reviewers of this paper for their helpful comments. Usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Sharia is the legal and moral basis of Islam that governs cultural practices, social interaction and economic activities (Lévy & Rezgui, Citation2015).

2 For more information see: http://aaoifi.com/adoption-of-aaoifi-standards/?lang=en

3 Speaking at the 10th annual AAOIFI–World Bank conference.

References

- Abras, A., & Jayasinghe, K. (2019). Competing institutional logics and institutional embeddedness of actors in islamic financial reporting standardisation. The British Accounting and Finance Association Annual Conference, 9–10 April, University of Birmingham.

- Ahrens, T., & Ferry, L. (2018). Institutional entrepreneurship, practice memory, and cultural memory: Choice and creativity in the pursuit of endogenous change of local authority budgeting. Management Accounting Research, 38, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2016.11.001

- Al Mahameed, M., Belal, A., Gebreiter, F., & Lowe, A. (2021). Social accounting in the context of profound political, social and economic crisis: The case of the Arab Spring. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(5), 1080–1108. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2019-4129

- Baños, S. M. J., & Carrasco, F. F. (2019). Institutional entrepreneurship in a religious order: The 1741 Constituciones of the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of God. Accounting History, 24(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373218802858

- Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization, 13(5), 653–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067008

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Bischof, J., Daske, H., & Sextroh, C. (2014). Fair value-related information in analysts’ decision processes: Evidence from the financial crisis. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 41(3), 363–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12063

- Biygautane, M., Neesham, C., & Al-Yahya, K. O. (2019). Institutional entrepreneurship and infrastructure public-private partnership (PPP): Unpacking the role of social actors in implementing PPP projects. International Journal of Project Management, 37(1), 192–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.12.005

- Bova, F., & Pereira, R. (2012). The determinants and consequences of heterogeneous IFRS compliance levels following mandatory IFRS adoption: Evidence from a developing country. Journal of International Accounting Research, 11(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar-10211

- Cooke, T. E., & Wallace, R. O. (1990). Financial disclosure regulation and its environment: A review and further analysis. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 9(2), 79–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4254(90)90013-P

- DiMaggio, P. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations: Culture and environment (pp. 3–21). Ballinger.

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dorado, S. (2005). Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organization Studies, 26(3), 385–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050873

- Dorado, S. (2013). Small groups as context for institutional entrepreneurship: An exploration of the emergence of commercial microfinance in Bolivia. Organization Studies, 34(4), 533–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612470255

- Dyreng, S. D., Mayew, W. J., & Williams, C. D. (2012). Religious social norms and corporate financial reporting. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 39(7-8), 845–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2012.02295.x

- Ezzamel, M., Robson, K., & Stapleton, P. (2012). The logics of budgeting: Theorization and practice variation in the educational field. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(5), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2012.03.005

- Felski, E. (2017). How does local adoption of IFRS for those countries that modified IFRS by design, impair comparability with countries that have not adapted IFRS? Journal of International Accounting Research, 16(3), 59–90. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar-51807

- Gambling, T., Jones, R., & Karim, R. A. A. (1993). Credible organizations: Self-regulation v. external standard-setting in Islamic banks and British charities. Financial Accountability and Management, 9(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.1993.tb00107.x

- Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078958

- Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069292

- Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785498

- Haas, P. M. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization, 46(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001442

- Hamid, S., Craig, R., & Clarke, F. (1993). Religion: A confounding cultural element in the international harmonization of accounting? Abacus, 29(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6281.1993.tb00427.x

- Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2008). Institutional entrepreneurship. In C. O. R. Greenwood, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersen (Ed.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 198–217). Sage.

- Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2017). Institutional entrepreneurship and change in fields. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence, & R. Meyer (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 261–280). Sage Publications.

- Hopwood, A. G. (1990). Accounting and organisation change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 3(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513579010145073

- Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2005). Institutions and entrepreneurship. In R. S. S. Agarwal Alvarez, & O. Kluwer (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 179–210). Springer.

- Ibrahim, S. H. M. (2000). Nurtured by Kufr: The western philosophical assumptions underlying conventional (Anglo-American) accounting. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services, 2(2), 19–38.

- Ibrahim, S. H. M., & Yaya, R. (2005). The emerging issues on the objectives and characteristics of Islamic accounting for Islamic business organizations. Malaysian Accounting Review, 4(1), 75–92.

- Judge, W., Li, S., & Pinsker, R. (2010). National adoption of international accounting standards: An institutional perspective. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(3), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2010.00798.x

- Kahl, S. J., Liegel, G. J., & Yates, J. (2012). Audience structure and the failure of institutional entrepreneurship. In S. J. Kahl, B. S. Silverman, & M. A. Cusumano (Eds.), History and strategy (pp. 275–313). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Kamla, R., & Haque, F. (2019). Islamic accounting, neo-imperialism and identity staging: The accounting and auditing organization for Islamic financial institutions. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 63, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2017.06.001

- Karim, R. A. A. (1990). Standard setting for the financial reporting of religious business organisations: The case of Islamic banks. Accounting and Business Research, 20(80), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1990.9728888

- Karim, R. A. A. (1995). The nature and rationale of a conceptual framework for financial reporting by Islamic banks. Accounting and Business Research, 25(100), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1995.9729916

- Karim, R. A. A. (1999). Accounting and auditing standards for Islamic financial institutions. (Ed.),^(Eds.). Proceedings of the Second Harvard University Forum on Islamic Finance: Islamic Finance into the 21 Century, Massachusetts.

- Karim, R. A. A. (2001). International accounting harmonization, banking regulation, and Islamic banks. The International Journal of Accounting, 36(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7063(01)00093-0

- Kivimaa, P., & Kern, F. J. R. P. (2016). Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 45(1), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008

- Lawrance, T., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2009). Introduction: Theorizing and studying institutional work. In T. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organization (pp. 1–27). Cambridge University Press.

- Lawrence, T. B., Hardy, C., & Phillips, N. (2002). Institutional effects of interorganizational collaboration: The emergence of proto-institutions. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069297

- Levy, A., & Rezgui, H. (2015). Professionnal and neoinstitutional dynamics in the Islamic accounting standards-setting process. In D. M. Boje (Ed.), Organizational change and global standardization: solutions to standards and norms overwhelming organizations (pp. 143–172). Routledge.

- Levy, D., & Scully, M. J. O. S. (2007). The institutional entrepreneur as modern prince: The strategic face of power in contested fields. Organization Studies, 28(7), 971–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078109

- Lewis, M. K. (2001). Islam and accounting. Accounting Forum, 25(2), 103–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6303.00058

- Lounsbury, M. (2008). Institutional rationality and practice variation: New directions in the institutional analysis of practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4-5), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.04.001

- Lounsbury, M., & Crumley, E. (2007). New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies, 28(7), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078111

- Maguire, S., Hardy, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159610

- Major, M., Conceição, A., & Clegg, S. (2018). When institutional entrepreneurship failed: The case of a responsibility centre in a Portuguese hospital. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(4), 1199–1229. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-09-2016-2700

- McGuire, S. T., Omer, T. C., & Sharp, N. Y. (2012). The impact of religion on financial reporting irregularities. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 645–673. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10206

- Meyer, R. E. J. O. (2006). Review essay: Visiting relatives: Current developments in the new sociology of knowledge. Organization, 13(5), 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067011

- Misangyi, V. F., Weaver, G. R., & Elms, H. (2008). Ending corruption: The interplay among institutional logics, resources, and institutional entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 750–770. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.32465769

- Munir, K. A., & Phillips, N. (2005). The birth of the ‘Kodak moment’: Institutional entrepreneurship and the adoption of new technologies. Organization Studies, 26(11), 1665–1687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605056395

- Nasir, N. M., & Zainol, A. (2007). Globalisation of financial reporting: An Islamic focus. In J. M. Godfrey & K. Chalmers (Eds.), Globalisation of accounting standards (pp. 261–274). Edward Elger Publishing Limited.

- Nobes, C., & Parker, R. H. (2012). Comparative international accounting. Pearson.

- Nobes, C., & Zeff, S. (2008). Auditors’ affirmations of compliance with IFRS around the world: An exploratory study. Accounting Perspectives, 7(4), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1506/ap.7.4.1

- Potter, B. N. J. A. (2005). Accounting as a social and institutional practice: Perspectives to enrich our understanding of accounting change. ABACUS, 41(3), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6281.2005.00182.x

- Rothenberg, S. (2007). Environmental managers as institutional entrepreneurs: The influence of institutional and technical pressures on waste management. Journal of Business Research, 60(7), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.02.017

- Sánchez-Matamoros, J. B., & Fenech, F. C. (2019). Institutional entrepreneurship in a religious order: The 1741 Constituciones of the Hospitaller order of Saint John of God. Accounting History, 24(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373218802858

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Seo, M.-G., & Creed, W. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 222–247. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134353

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. (1992). Master frames and cycles of protest. In A. D. Morris & C. M. Mueller (Eds.), Frontiers in social movement theory (pp. 133–155). Yale University Press.

- Thornton, P. H., Jones, C., & Kury, K. (2005). Institutional logics and institutional change in organizations: Transformation in accounting, architecture, and publishing. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 23, 125–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-558X(05)23004-5

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press.

- Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Jarvis, O. (2011). Bridging institutional entrepreneurship and the creation of new organizational forms: A multilevel model. Organization Science, 22(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0522

- Walton, P., Haller, A., & Raffournier, B. (2003). International accounting. Thomson.

- Yang, C., & Modell, S. (2013). Power and performance: Institutional embeddedness and performance management in a Chinese local government organization. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(1), 101–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571311285630

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage publications.

- Zeghal, D., & Mhedhbi, K. (2006). An analysis of the factors affecting the adoption of international accounting standards by developing countries. The International Journal of Accounting, 41(4), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2006.09.009

Appendix

Table A1. List of Interviewees.