?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), has left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archive collections. There is evidence, however that other letters from Mary Stuart are missing from those collections, such as letters referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere. In Under the Molehill – an Elizabethan Spy Story, John Bossy writes that a secret correspondence with her associates and allies, prior to its compromise in mid-1583, was “kept so secure that none of it has survived, and we don’t know what was in it.” We have found over 55 letters fully in cipher in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which, after we broke the code and deciphered the letters, unexpectedly turned out to be letters from Mary Stuart, addressed mostly to Michel de Castelnau Mauvissière, the French ambassador to England. Written between 1578 and 1584, those newly deciphered letters are most likely part of the aforementioned secret correspondence considered to have been lost, and they constitute a voluminous body of new primary material on Mary Stuart – about 50,000 words in total, shedding new light on some of her years of captivity in England.

1. Introduction

Numerous collections of historical enciphered letters are held in archives. Many ciphertexts can be attributed to specific historical characters and periods. Attribution is possible if the catalog is complete and accurate, or if the ciphertext is accompanied by a plaintext version. This is also possible if the ciphertext is next to related letters, or if the date, the sender, and the recipients are written in clear. However, there are collections of ciphertexts in archives that cannot be attributed unless they are first deciphered. Making them accessible for historical research requires a systematic and large effort to locate, digitize, transcribe, decipher, and analyze them, such as the DECRYPT Project and the Cryptiana website.Footnote1

As part of those efforts, we came across several collections in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), primarily Français 2988 and Français 20506, containing more than fifty documents fully in cipher.Footnote2 Using computerized codebreaking techniques, together with manual textual and contextual analysis, we were able to recover the cipher key and decipher all the letters. To our great surprise, those letters turned out to be from Mary Stuart, from 1578 to 1584, addressed mostly to Michel de Castelnau, seigneur de La Mauvissière, the French ambassador in London between 1575 and 1585. We also found in British Archives plaintext copies of seven of those deciphered letters, from 1583 to 1584, which were apparently leaked to Francis Walsingham,Footnote3 Queen Elizabeth I’s secretary and spymaster, by a mole in Castelnau’s embassy.Footnote4 Those plaintext copies allowed us to definitively confirm the origin of the deciphered letters.

In the BnF catalog, the ciphertext documents are merely listed as “Pièce en chiffre” or “dépêches chiffrées”,Footnote5 while other items in the same collections are described as originating from the 1520s and 1530s and mostly relating to Italian affairs. Furthermore, the ciphertext documents do not contain any parts in clear, and the letters could not have been attributed without first deciphering them. This may explain why such an important source of material had not been previously associated with Mary Stuart before our work.Footnote6

The present paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide a brief background on Mary Stuart. Section 3 presents sources for the ciphertexts, other letters from and to Mary, and Mary’s ciphers. Section 4 describes the process of breaking the code and deciphering the letters. Section 5 provides an inventory and summaries of the deciphered letters, highlighting some recurrent topics, and reproducing several letters in full. Section 6 describes Mary Stuart’s secret communication channels and methods, an important aspect highlighted by the decipherment of the letters. Section 7 presents concluding remarks and directions for future research. In Appendix A, we describe the codebreaking algorithm. In Appendix B, we examine a theory as to why the letters include numerous systematic enciphering errors that make their decipherment sometimes challenging. In Appendix C, we provide an up-to-date list of all known letters from Mary Stuart to Castelnau.

2. Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots, (1542–1587, see ) acceded to the throne of Scotland when she was six days old after the premature death of her father James V. Sent to France in 1548, she was brought up in the French court. In 1558, she married the Dauphin Francis,Footnote7 who succeeded to the French throne in 1559 but died the year after. Mary returned to Scotland in 1561. As a dowager Queen of France, she still had properties in France. Charles IX and Henry III,Footnote8 who succeeded to the French throne one after the other, and Francis, Duke of Alençon (and, later, Duke of Anjou),Footnote9 Elizabeth’s suitor, were her brothers-in-law. Catherine de’ Medici was her mother-in-law.Footnote10 The members of the powerful family of Guise were Mary’s relatives through her mother Marie de Guise: the Cardinal of Lorraine,Footnote11 her uncle, was her mentor, and Henry, Duke of Guise, her cousin, was an ardent supporter of her cause.Footnote12

Figure 1. Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) – François Clouet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fran%C3%A7ois_Clouet_-_Mary,_Queen_of_Scots_(1542-87)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg [Accessed November 29, 2022].

![Figure 1. Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) – François Clouet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fran%C3%A7ois_Clouet_-_Mary,_Queen_of_Scots_(1542-87)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg [Accessed November 29, 2022].](/cms/asset/a8f8ec39-22be-4b59-8197-c8bc2403cb8b/ucry_a_2160677_f0001_c.jpg)

Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley in 1565, but by the time she gave birth to a son, future James VI, in 1566, she had been disillusioned with Darnley. Her third marriage with the Earl of Bothwell,Footnote13 too soon after the extraordinary death of Darnley, alienated the Scottish people because Bothwell was suspected by many to have been involved in his murder. Protestant nobles turned against Mary and imprisoned her in Lochleven, a castle on an island in the middle of a lake, where she was forced to abdicate in favor of her infant son in 1567.

In 1568, Mary escaped from Lochleven and fled to England, seeking protection from Queen Elizabeth. If Mary thought Elizabeth would help her regain her throne, she was mistaken. Elizabeth and her council considered Mary to be a threat. Descended from Henry VIII’s sister, Mary had a claim to the English throne, and there were many Catholics who believed that Elizabeth was an illegitimate queen, because, in their eyes, Henry VIII’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon and his marriage with Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s mother, were void, and Mary was the rightful queen of England. Rather than restoring Mary to the Scottish throne, Elizabeth preferred James to be King of Scotland with pro-English regents. For Elizabeth, restoring the Catholic Mary to the Scottish throne to the detriment of its Protestant regime or allowing her to claim the English throne from France or elsewhere was too risky.

Mary spent the remaining nineteen years of her life captive in England. For most of this period, Mary was in the custody of the Earl of Shrewsbury,Footnote14 and she lived in his properties such as Tutbury Castle, Sheffield Castle, Sheffield Manor, Wingfield Manor, and Chatsworth House.

Mary managed to keep a correspondence with her contacts in England, such as Castelnau, the French ambassador in London, and those in France, including James Beaton, Archbishop of Glasgow,Footnote15 her ambassador in Paris.Footnote16

Even while in captivity, Mary inevitably continued to be the focus of Catholic plots to put her on the English throne with the help of Catholic powers. The Ridolfi Plot in 1571 resulted in the execution of the Duke of Norfolk,Footnote17 whom Mary had intended to marry. This was not to be the last of such plots.

During prolonged negotiations for a marriage between Elizabeth and the Duke of Anjou, Mary openly professed her support of an Anglo-French alliance, while secretly approaching Spain with her own schemes including marrying her son James to a Spanish princess.

Mary’s relationship with her son was also a matter of concern for the English government. Although their relationship was strained because Mary had revoked her forced abdication and claimed to be the sole queen of Scotland, Mary’s hopes rose when Esmé Stewart came over from France in 1579, became the boy king’s favorite, was created Earl of Lennox in 1580 and promoted to Duke in 1581.Footnote18 Wary of their rapprochement, Elizabeth sent her commissioners Robert BealeFootnote19 and later Sir Walter MildmayFootnote20 to Mary under the pretense of negotiating for her release in return for her renouncing any claim to the English crown.

In the meantime, in August 1582, James was kidnapped by a pro-English faction led by William Ruthven, Earl of Gowrie (the Ruthven Raid), and the Duke of Lennox fell from power. The French royal court tried to renew the alliance between France and Scotland by sending to Scotland de la Mothe-FénelonFootnote21 and Sieur de MainnevilleFootnote22 in January 1583. When the king freed himself from the pro-English faction in July 1583, it was Elizabeth’s turn to send Sir Francis Walsingham to Scotland in September 1583 in an attempt to recover the lost grounds.

The discovery in November 1583 of the Throckmorton Plot,Footnote23 one of several Catholic plots to depose Elizabeth and put Mary on the English throne, led to the tightening of the watch on Mary. Moreover, the Earl of Shrewsbury, Mary’s keeper since 1569, who was occasionally accused of being too lenient with Mary, had to be replaced in those times of increasing Catholic threats. The immediate cause was the domestic scandal caused by the Countess of Shrewsbury’sFootnote24 false accusations of her husband having an affair with Mary. Mary was put under the custody of Sir Ralph SadlerFootnote25 in August 1584, then taken over by a sterner jailor, Sir Amias PauletFootnote26 in April 1585. Under his uncompromising vigilance, Mary’s private communications with the outside world ceased completely.

A greater blow came early in 1585, when Scotland officially rejected proposals for an “association”, i.e., a joint rule, in which Mary and James would share the crown. Mary deplored that she was betrayed by her beloved son, and her hopes for a positive political outturn were shattered by the Treaty of Berwick made on 6 July 1586, in which James allied himself with England with the prospect of succeeding to the throne of England after Elizabeth.

It was at about this time that Mary fatally committed herself to the Babington Plot. Back in January 1586, a local brewer brought in a note from Gilbert Gifford,Footnote27 accompanied by a recommendation from Thomas Morgan, Mary’s trusted agent in Paris.Footnote28 Thus a secret communication channel was established whereby the brewer would carry packets of letters mediated by Gifford in a beer barrel. But this was a trap carefully orchestrated by Walsingham to produce hard evidence to incriminate Mary. Gifford had been turned into a double agent by Walsingham when he was captured upon his landing from France.Footnote29 He provided every letter which passed through his hands to Walsingham, and those in cipher were deciphered by Thomas Phelippes.Footnote30

When Mary received a letter from Babington which included the incriminating passage “The dispatch of the vsurping Competitor” (which implies the assassination of Queen Elizabeth), on 17 July 1586 she made the fatal decision to reply despite her secretaries’ better advice. Her answer was drafted by Jacques Nau,Footnote31 her French secretary. Then, it was translated into English and enciphered by Gilbert Curll, Mary’s Scotch secretary.Footnote32

Mary’s reply to Babington was handed over to Paulet by Gifford and deciphered by Phelippes, who added a postscript in the same cipher. In this forged postscript, Mary allegedly expressed her wish to “know the names and qualities of the sixe gentlemen, which are to accomplish the designment.”Footnote33 The conspirators were arrested and made full confessions. Mary was brought to trial and was found guilty despite pleading her innocence. Interestingly, the forged postscript was not used against her. She was executed in February 1587 in Fotheringhay Castle.

3. Sources

We list here the sources for the encrypted letters we have deciphered. As almost all of them were written by Mary to Michel de Castelnau, we also list here our sources for previously known letters between Mary and Castelnau, and other related letters. Finally, we mention sources for other ciphers employed by Mary.

3.1. Mary’s letters to Castelnau

Castelnau was the French ambassador in London from 1575 to 1585. Castelnau and Mary regularly exchanged letters, some written in cipher. Previously known letters from Mary to Castelnau originate from various archival collections, including:

The National Archives (TNA)

○ SP53

British Library (BL)

○ Cotton MS, Caligula C

○ Harley MS 1582

○ Add MS 48049

Hatfield House, Cecil Papers

Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

○ Cinq Cents de Colbert (500 de Colbert) 470-471

○ Français 3158 (fr. 3158; formerly Béthune 8675)

○ Français 3181 (fr. 3181; formerly Béthune 8690)

○ Français 4736 (fr. 4736; formerly Supplément Français, no. 593(3))

The archives of the d’Esneval family.Footnote34

Most of the letters known to have been written by Mary were published in 1844 by Labanoff, in his seven-volume Lettres, instructions et mémoires de Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse. Additional letters are reproduced in Teulet (Citation1859) and Basing (Citation1994) or listed in catalogs, such as the Calendars of State Papers (CSP) or Hatfield Calendar, and in an appendix in Bossy (Citation2001). Some letters can be read in English translation in Strickland (Citation1844), supplemented by Turnbull (Citation1845).

Some of Castelnau’s letters to Mary, to Henry III, and to Catherine de’ Medici, that occasionally reference letters from Mary, are reproduced in Teulet (Citation1862), and originate from various sources (ibid. 1-2n1): BnF fr. 15973 (formerly, Harlay 223), fr. 3305 (Béthune 8808), fr. 3307 (Béthune 8810), fr. 3308 (Béthune 8811), fr. 3377 (Béthune 8880), 500 de Colbert 337, 401, Mélanges de Colbert 11, Archives nationales K.95 (formerly Archives de l’Empire).

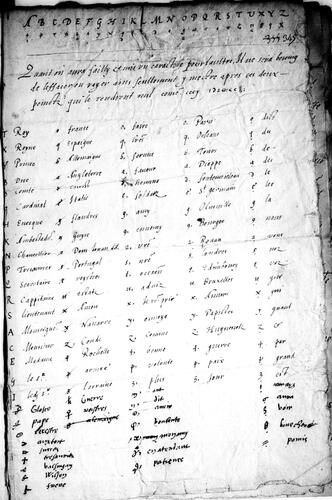

3.2. Newly deciphered ciphertexts

The ciphertexts we deciphered are from various collections in BnF:

BnF Français 2988 (fr. 2988; historically 8513 of the collection Béthune):Footnote35 Described in the catalogFootnote36 as “Recueil de lettres et de pièces originales, et de copies de pièces indiquées comme telles dans le dépouillement qui suit,” followed by a list of 56 items, 26 of which being ciphertexts we deciphered, simply indicated as “Pièce en chiffre” in the catalog: f.21, f.26, f.30, f.34, f.38, f.42, f.46, f.50, f.54, f.58, f.64, f.69, f.74, f.78, f.82, f.87, f.89, f.96, f.98, f.105, f.109, f.113, f.118, f.123, f.125, f.130.

BnF Français 20506 (fr. 20506; historically Gaignières 394): Described as “Lettres adressées au grand-maître Anne de Montmorency, dépêches chiffrées et pièces diverses, relatives surtout à l’Italie”, with no detailed listing in the catalog. The 28 letters we deciphered are f.151, f.153, f.158, f.163, f.165, f.170, f.174, f.179, f.181, f.185, f.190, f.194, f.198, f.221, f.223, f.225, f.227, f.229, f.231, f.233, f.235, f.237, f.239, f.241, f.243, f.245, f.247, f.249.Footnote37

BnF Cinq Cent de Colbert 470: There are two letters we deciphered, f.307 and f.308. This volume contains other documents – not in cipher – from Castelnau’s office.

BnF Français 3158 (fr. 3158): f.57 is a letter from Mary to Castelnau, from 30 October 1584. It is written mostly in clear, but it contains short enciphered passages.Footnote38

Except for the last item, all the letters are entirely in cipher, with nothing to indicate the date, the writer, or the recipient. Moreover, the newly deciphered letters in fr. 2988 and fr. 20506 are interspersed with letters in Italian, most of them unencrypted, or with names and dates in clear, originating from the first half of the 16th century, giving the wrong impression that the plaintext documents were the deciphered versions of those letters.

By coincidence, the ranges of folio numbers containing the relevant ciphertexts in the first two collections do not overlap. In BnF fr. 2988, the relevant folios are numbered between 21 to 130, and in BnF fr. 20506 the relevant folios are numbered between 151 to 244.Footnote39 Similarly, the relevant folio numbers in the last two collections (307, 308, 57) are unique to those collections. This allows us to employ a convenient naming scheme in this paper: Whenever referring to a certain ciphertext document, we only mention its folio number, preceded with a capital F, such as F123 for f.123 of BnF fr. 2988, or F241 for f.241 of BnF fr. 20506.

3.3. Mary’s ciphers

More than a hundred ciphers related to Mary, Queen of Scots, are preserved in The British National Archives (TNA), mainly in SP53/22 and SP53/23.Footnote40

SP53/22 includes “Ciphers, including those for papers seized at Chartley Castle on the discovery of the conspiracy in 1586 which were used, when deciphered, to implicate Mary and bring her to trial.” The ciphers in SP53/22 were seized in Mary’s rooms in Chartley Castle when she was arrested following the exposure of the Babington Plot.

SP53/23 is a collection of ciphers from 1554–1577, broken by John Somer, a codebreaker in the service of Walsingham before the famous Thomas Phelippes.Footnote41 This volume includes more than sixty ciphers.

SP12/193/54 includes the most famous cipher of Mary, Queen of Scots, the Babington cipher used in her fatal correspondence with Babington, as well as two other ciphers, one of which is used in Mary’s letter to D. Lewis in 1586.Footnote42 A copy of the Babington cipher is also in Add MS 27027, f.313v.

SP106/1-3, a large depot of Elizabethan ciphers, includes an incomplete reconstruction of a cipher used by Mary, Albert Fontenay, and her secretary Nau (SP106/1/48A).Footnote43

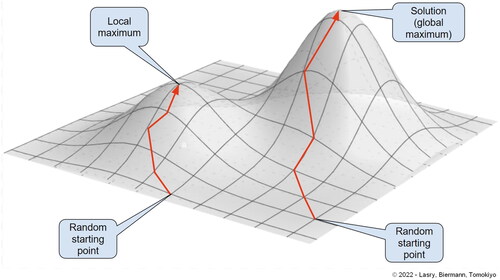

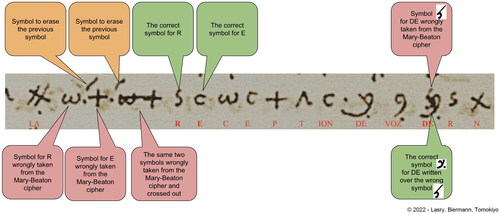

4. Deciphering the letters

This section describes how we deciphered the letters, combining computerized cryptanalysis, manual codebreaking, and linguistic and contextual analysis. The first step was to transcribe the documents which contain only graphical symbols into a format readable by software programs. Due to a large amount of material (more than 150,000 symbols in total), and since automated transcription such as off-the-shelf OCR software was not applicable,Footnote44 we utilized a special GUI (graphical user interface) tool developed by the CrypTool 2 project.Footnote45 After transcribing some documents, we performed an initial computer analysis and decipherment, applying the GUI tool codebreaking function described in Appendix A, identifying the original plaintext language, which turned out to be French, and recovering fragments of plaintexts. We then recovered the homophones – the symbols representing single letters of the alphabet, also identifying special symbols (e.g., a symbol to duplicate the last symbol), and the structure of the cipher. After that, we could identify the symbols for common prefixes, suffixes, prepositions, and words. Based on the partial decipherment of several documents, we were able to attribute the letters to Mary, Queen of Scots, addressed to Castelnau, the French ambassador. By reviewing the text of previously-known letters between Mary and Castelnau, we found several documents matching our decipherments, enabling us to determine or validate the meaning of other symbols. Finally, we identified symbols representing names, places, and the twelve months of the year and completed the transcription and decipherment of all the documents.

In the process, we stumbled upon numerous obscure passages, which were either unintelligible or contained a large number of spelling errors. Upon closer examination, we identified recurrent patterns of enciphering errors unlikely to be just the sporadic errors expected when enciphering long letters. We were able to identify the likely cause of those errors, which can be explained by the concurrent use of multiple cipher tables – for different recipients, as we describe in Appendix B. After identifying those error patterns, we were able to complete the decryption of those challenging passages and interpret them.

The recovered cipher table is similar in design to contemporary ciphers, such as other ciphers used by Mary, Queen of Scots, and Castelnau, the French ambassador.

The codebreaking and decipherment process was primarily iterative. We first transcribed a few documents, recovered some parts of the key, then transcribed additional documents, recovered more parts, and so on, rather than fully completing one step before starting the next one. However, for clarity, we describe the process as a sequence of distinct steps. We illustrate the process using one of the deciphered documents, F38, from 20 January 1580.

4.1. Contemporary ciphers

The basic principle of ciphers remained the same for centuries, each letter of the alphabet being substituted with a symbol, i.e., a substitution cipher. The simplest form was the monoalphabetic substitution cipher, with each letter represented by a unique symbol. As early as the 10th century, Arabic scholars developed effective methods for codebreaking based on frequency analysis. Those methods rely on the fact that some letters of the alphabet, e.g., e or t in English, are much more frequent than other letters of the alphabet and the symbols representing them are likely to be the most frequent in ciphertexts and easy to identify. To thwart codebreaking based on frequency analysis, homophonic ciphers were introduced, in which, for the most common letters, e.g., e, there was a choice of several symbols (a.k.a. homophones) to encipher that letter. Because common words or syllables were also likely to reveal recurring patterns useful to codebreakers, a nomenclature, consisting of a list of symbols for frequently used words, names, or syllables, was also included in ciphers.Footnote46 Null symbols, or nulls, that should be ignored during decryption, were often included in ciphers, as well as special symbols to repeat the preceding symbol or to delete the preceding symbol. The symbols were either arbitrary symbols, including geometrical shapes, Latin or Greek letters, alchemy and astronomy symbols, letter variants, and Arabic figures. Homophonic substitution ciphers, usually accompanied by a nomenclature, remained the standard for centuries.Footnote47

Before starting the codebreaking and decipherment processes, we were expecting the cipher to be homophonic, with a nomenclature. However, we did not know – a priori – the language of the original unencrypted letter.

4.2. Transcribing the letters

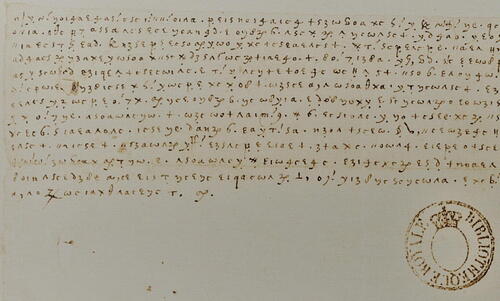

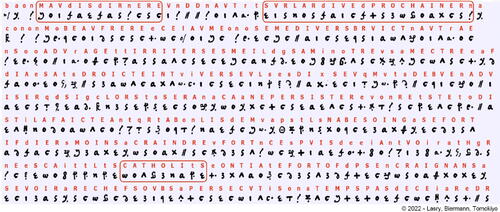

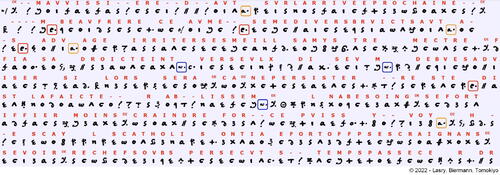

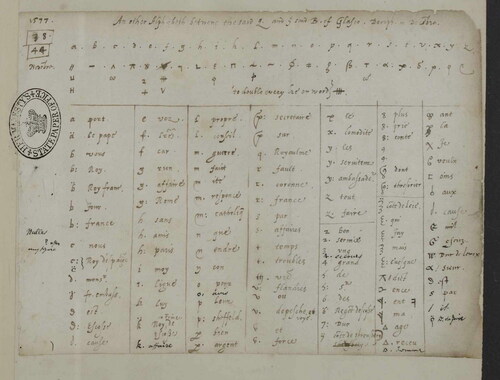

The letters we deciphered consist only of graphical symbols, without any text in clear. An example of an enciphered letter – F38 – is shown in .

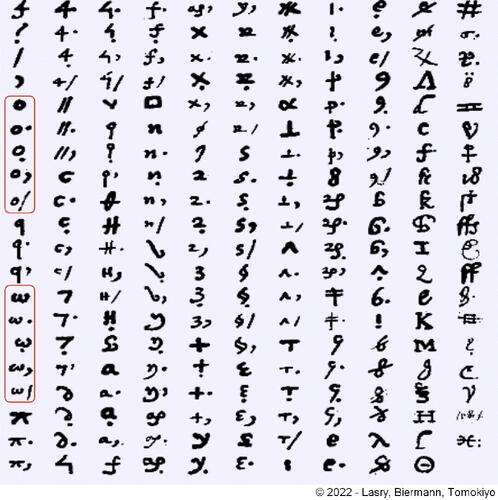

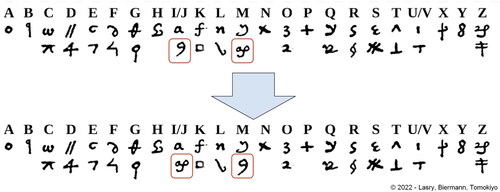

In all the ciphertexts, we have identified 219 distinct graphical symbol types listed in . It can be seen that some symbols are variants of other symbols with the addition of various diacritics, such as the highlighted examples. Based on our knowledge of contemporary ciphers, it was expected that those diacritics would be significant, completely changing the meaning of the symbols.Footnote48 To obtain an accurate transcription, it was essential to capture the symbols with diacritics separately from the same symbols without them.

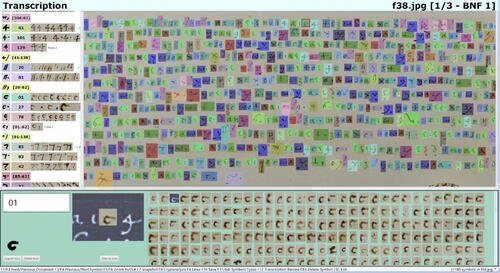

In , a screenshot of the transcription GUI tool is shown. Using computer mouse gestures, symbols can be marked with a surrounding box, and assigned to specific symbol types (at this stage we did not know yet the meaning of those types, so we assigned them some arbitrary numbers).

4.3. Initial decryption

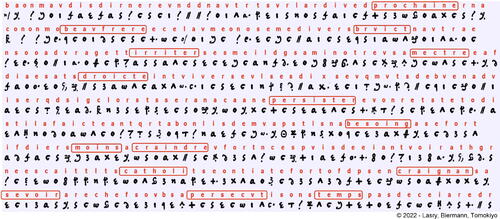

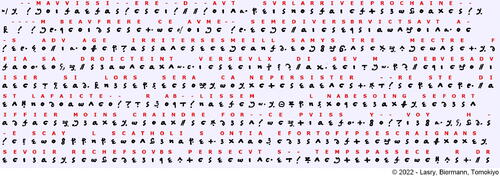

To recover and map the homophones, i.e., the symbols representing the letters of the alphabet (a to z), we employed the codebreaking algorithm of the GUI tool, which is described in Appendix A. At first, we had no way of knowing which symbols are homophones and represent single letters and which symbols represent other language entities such as words or names. We, therefore, assumed that any symbol could represent any letter of the alphabet and applied codebreaking under this assumption. We first assumed that the language was Italian, as most of the other documents in the archive collections are in Italian, but obtained no meaningful results. Next, assuming that the language was French, we obtained a tentative decryption, as shown in .

It is possible to discern multiple modern French words (“prochaine”, “beau-frere”, “irriter”, “persister”, “moins”, “temps”, “se voir”),Footnote49 Middle French words (“bruict”, “mectre”)Footnote50, or plausible parts of words (“catholi…”, “craignan…”, “persecut…”).

Next, we marked those plausible fragments in the GUI tool, confirming the assignments of the homophone symbols that form those fragments, which now appear in capital letters, as shown in , in which we also highlight a few interesting sequences. We now focus on the unconfirmed symbols (in lower case in the decryption) which were likely to have been wrongly assigned.

From the sequence SVRLAR IVE

IVE PROCHAINE, and from other sequences, we hypothesized that the symbol

PROCHAINE, and from other sequences, we hypothesized that the symbol  may have the effect of duplicating the last letter instead of representing one of the letters of the alphabet, because under this assumption, SVRLAR

may have the effect of duplicating the last letter instead of representing one of the letters of the alphabet, because under this assumption, SVRLAR IVE

IVE PROCHAINE reads as SURLARRIVEEPROCHAINE (“sur l’arrivée prochaine” – about the upcoming arrival), which is plausible.

PROCHAINE reads as SURLARRIVEEPROCHAINE (“sur l’arrivée prochaine” – about the upcoming arrival), which is plausible.

The expression “sur l’arrivée prochaine” is expected to be followed by the word “de” (of, in English), rather than a word starting with the letter R as in the tentative decryption in . We hypothesized that the symbol ![]() that follows R may indicate that the previous symbol should be erased. This hypothesis was confirmed when analyzing other sequences. For example, under this assumption, the sequence MAV

that follows R may indicate that the previous symbol should be erased. This hypothesis was confirmed when analyzing other sequences. For example, under this assumption, the sequence MAV IS

IS IR

IR![]() ERE reads as MAVVISSIERE, Mauvissiere being a plausible French name (and in fact, the French ambassador to England and the recipient of the letter).Footnote51

ERE reads as MAVVISSIERE, Mauvissiere being a plausible French name (and in fact, the French ambassador to England and the recipient of the letter).Footnote51

It can be seen in that symbols with diacritics, when interpreted by the tool as homophones representing single letters of the alphabet, are usually not part of contiguous plausible segments. Furthermore, based on our knowledge of contemporary ciphers, we also expected that symbols with diacritics would rather represent words or entities other than single letters. For example, the sequence CATHOLI S is likely to be CATHOLIQUES (Catholics), the symbol

S is likely to be CATHOLIQUES (Catholics), the symbol  representing the word QUE (that) rather than one of the letters of the alphabet.

representing the word QUE (that) rather than one of the letters of the alphabet.

4.4. Recovering the homophone symbols

To recover the mapping of the homophones more accurately, we excluded all the symbols with diacritics, so that only those without diacritics are considered to be homophone candidates by the tool’s codebreaking algorithm. We thus obtained an improved decryption, as shown in . There are significantly fewer sequences that do not make sense compared to the initial decryption in Section 4.3, and most of the recovered segments contain either complete words or plausible parts of words.

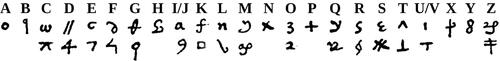

The recovered mapping of the homophones is shown in . It can be seen that there are two homophones for most letters of the alphabet, and only one for the remaining letters.Footnote52

4.5. Recovering the symbols for words and parts of words

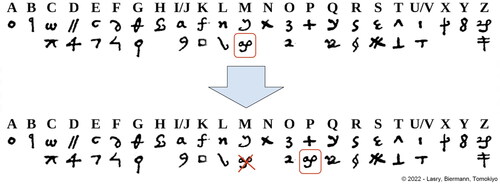

We illustrate here the generic process to recover the meaning of the symbols which are part of the nomenclature, i.e., they represent words or parts of words, e.g., prefixes and suffixes. As mentioned in Section 4.4, we expected those symbols to include diacritics. The process was performed manually, with the aid of the GUI tool, based on linguistic analysis of the deciphered fragments.Footnote53

In , we highlight the occurrences of the symbol  , of which we don’t yet know the meaning.

, of which we don’t yet know the meaning.

The first occurrence follows L’ARRIVEE PROCHAINE (the upcoming arrival) and we expect this expression to be followed by “de” (of). The third instance (on the fifth line) precedes CA, so if  is “de”, this could be “deça” (over here), which is also plausible. Other instances of

is “de”, this could be “deça” (over here), which is also plausible. Other instances of  , including in other ciphertext documents, also look plausible when interpreted as “de” and we can assume that

, including in other ciphertext documents, also look plausible when interpreted as “de” and we can assume that  means “de”.

means “de”.

We manually enter the assignment of  as “DE” in the GUI tool, and obtain the decryption shown in , in which we also highlight the symbols

as “DE” in the GUI tool, and obtain the decryption shown in , in which we also highlight the symbols  ,

,  , and

, and  , which we want to interpret next.

, which we want to interpret next.

appears in ADV

appears in ADV AGE, which is likely to be “advantage”, and therefore,

AGE, which is likely to be “advantage”, and therefore,  is likely to represent the common French suffix ANT.

is likely to represent the common French suffix ANT.  also appears in AVT

also appears in AVT , which results in AVTANT (“autant”, so much), and in VOY

, which results in AVTANT (“autant”, so much), and in VOY – resulting in VOYANT (“voyant”, seeing), both also being plausible.

– resulting in VOYANT (“voyant”, seeing), both also being plausible. appears in R

appears in R ABLISSEM

ABLISSEM , likely to be RESTABLISSEMENT (the Middle French form of “rétablissement”, reestablishment). So

, likely to be RESTABLISSEMENT (the Middle French form of “rétablissement”, reestablishment). So  would be EST (“est”, is), and

would be EST (“est”, is), and  the common French suffix ENT.

the common French suffix ENT.  also appears in INT

also appears in INT , which could be INTENT, and as it is followed by

, which could be INTENT, and as it is followed by  , another symbol with diacritics, INT

, another symbol with diacritics, INT

may represent INTENTION,

may represent INTENTION,  representing ION, which is also compatible with PERSECUT

representing ION, which is also compatible with PERSECUT , “persecution”, in the last line.

, “persecution”, in the last line. appears in M

appears in M BEAVFRERE, which could be “mon beau-frere” (my brother-in-law), and thus,

BEAVFRERE, which could be “mon beau-frere” (my brother-in-law), and thus,  likely represents ON, which is also a French word (loosely translated to “one” or “someone”). This is also consistent with

likely represents ON, which is also a French word (loosely translated to “one” or “someone”). This is also consistent with  SEMEDIVERSBRUICTS, or “on seme divers bruicts” (someone is spreading various rumors) in the second line.

SEMEDIVERSBRUICTS, or “on seme divers bruicts” (someone is spreading various rumors) in the second line.

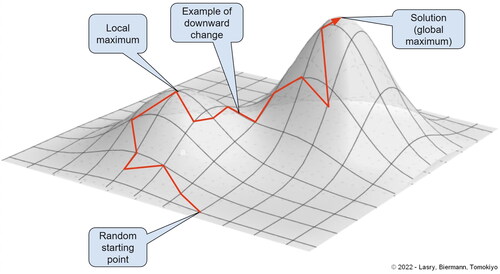

Using the GUI tool, it is possible to test new hypotheses and discard those that are not plausible. New hypotheses, if found to be correct, will in turn lead to the successful interpretation of new symbols, creating an “avalanche effect” and allowing for the recovery of the meaning of the vast majority of the symbols. The process is somewhat analogous to solving a large crossword puzzle, except that the tool’s codebreaking algorithm provides a headstart, by automatically identifying and mapping the homophones – the symbols that represent the letters of the alphabet.

4.6. Recovering the symbols for names and places

We identified most of the symbols representing people and places using contextual analysis, initially recognizing the characters, events, and places referred to in the ciphertext based on additional sources and the historical context. We could do that only after we had made significant progress with deciphering the documents and could read most of the deciphered text.

We illustrate the process with the symbol  , which we expected to represent a proper name. This symbol appears in “sur l’arrivée prochaine de

, which we expected to represent a proper name. This symbol appears in “sur l’arrivée prochaine de  mon beau-frere” (about the upcoming arrival of

mon beau-frere” (about the upcoming arrival of  my brother-in-law). After we were able to establish that the author of the letters was Mary, Queen of Scots, we considered the historical figures who could have been her brother-in-law mentioned in the letters. There were three candidates, as Mary had been married to the late French King Francis II, who had three brothers when he died in 1560. One brother, Charles IX, was King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He was succeeded by Henry III, another brother who reigned from 1574 to 1589. The third brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou, was engaged in negotiations to marry Elizabeth I, Queen of England, and made several visits to England to meet her. Since Mary was in captivity in England when she wrote about the upcoming arrival of

my brother-in-law). After we were able to establish that the author of the letters was Mary, Queen of Scots, we considered the historical figures who could have been her brother-in-law mentioned in the letters. There were three candidates, as Mary had been married to the late French King Francis II, who had three brothers when he died in 1560. One brother, Charles IX, was King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He was succeeded by Henry III, another brother who reigned from 1574 to 1589. The third brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou, was engaged in negotiations to marry Elizabeth I, Queen of England, and made several visits to England to meet her. Since Mary was in captivity in England when she wrote about the upcoming arrival of  , her brother-in-law, it is clear from the historical context that the symbol

, her brother-in-law, it is clear from the historical context that the symbol  must represent Francis, Duke of Anjou.

must represent Francis, Duke of Anjou.

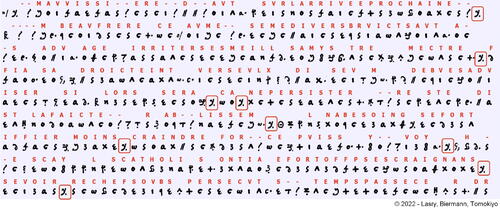

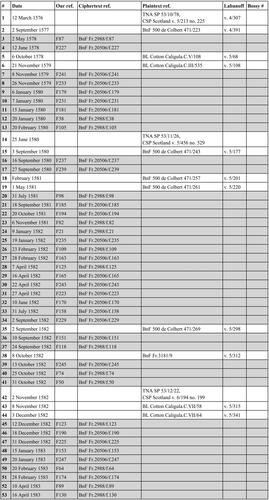

Other names and places were less straightforward to identify, some of them being mentioned only once or very few times in the collections of ciphertexts. The discovery of plaintext copies of several deciphered letters in archives was a great aid in the process, as they mentioned names which could be matched with certain symbols.Footnote54 Eventually, we were able to recover the meaning of almost all the 219 distinct symbol types, apart from a handful of less-frequent ones. In , we show our final decipherment of F38. We highlight an enciphering error (an error made by the secretary who enciphered the letter in 1580), OFFPSEZ instead of the expected OFFENSEZ (offended), likely due to the fact that the symbol for the letter p,  , is similar to the symbol for EN,

, is similar to the symbol for EN,  , but without the dot.

, but without the dot.

The complete plaintext reformatted with spaces and punctuation may be found in Section 5.3 (F38), together with a tentative translation.

4.7. Recovering the symbols for the months

The deciphered letters usually included, near the end, the day of the month, spelled out in full, and a symbol representing the month. We recovered the symbols representing the months of the year by examining letters for which a copy of the plaintext was available, and by analyzing the contents of deciphered letters taking into consideration the historical context, with the following series of deductions:

By comparing our decipherments to known plaintext copies of those letters, we identified the symbols for February (F58), March (F96), April (F96), July (F46), August (F69), and September (F69).

F87 dates from “ce deuxiesme

, jour de ma delivrance de Loklin”, i.e., the anniversary of Mary’s escape from Lochleven Castle, which was on 2 May 1568, hence the symbol

, jour de ma delivrance de Loklin”, i.e., the anniversary of Mary’s escape from Lochleven Castle, which was on 2 May 1568, hence the symbol  stands for May.

stands for May.F98 is from the last day of July, and acknowledges the receipt of Castelnau’s last letters from the 26th of

, which must be 26th of June (May and April already being assigned to other symbols).

, which must be 26th of June (May and April already being assigned to other symbols).In F50, from the last day of

, Mary reports that the Earl of Shrewsbury has read to her a letter from Walsingham with answers from Queen Elizabeth to du Ruisseau’sFootnote55 requests on Mary’s behalf. Another letter (a draft in Nau’s hand) from 2 November 1582 dates this specific event to 31 October,Footnote56 from which it follows that

, Mary reports that the Earl of Shrewsbury has read to her a letter from Walsingham with answers from Queen Elizabeth to du Ruisseau’sFootnote55 requests on Mary’s behalf. Another letter (a draft in Nau’s hand) from 2 November 1582 dates this specific event to 31 October,Footnote56 from which it follows that  stands for October.

stands for October.In F21, from 9 January (“janvier” being spelled out), Mary acknowledges the receipt of Castelnau’s letters from the 9th and 13th of

, and in F123, from the 12th of

, and in F123, from the 12th of  , she confirms the receipt of Henry Howard’sFootnote57 letters from the 24th of

, she confirms the receipt of Henry Howard’sFootnote57 letters from the 24th of  , from which it follows with high confidence, considering the months already assigned, that

, from which it follows with high confidence, considering the months already assigned, that  is December and

is December and  is November.

is November.The only remaining month, January, fits the last unassigned month symbol,

, as there is thematic overlap between the deciphered F38, from the 20th of

, as there is thematic overlap between the deciphered F38, from the 20th of  , and a letter to Beaton from 20 January 1580,Footnote58 so both letters are likely to have been written on the same day.

, and a letter to Beaton from 20 January 1580,Footnote58 so both letters are likely to have been written on the same day.

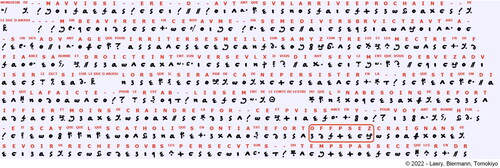

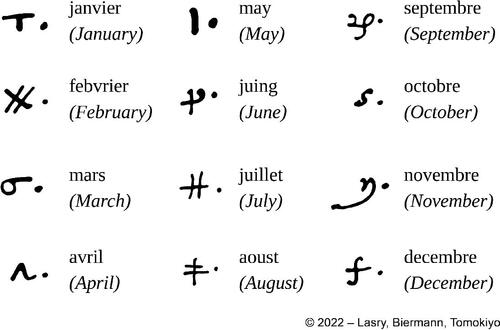

shows the recovered month symbols (applying French spelling that is consistent with contemporary letters written by Nau).

4.8. The complete reconstructed Mary-Castelnau cipher

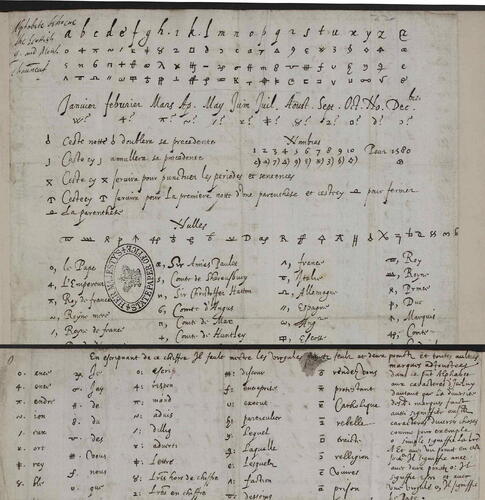

We show in and our reconstruction of the cipher used by Mary Stuart to communicate with Castelnau.

In Middle French writings, the letters u and v were not distinguished as they are today (v for the consonantal [v], u for the vocalic [u] and the semi-vocalic [ɥ]). They could be used interchangeably, while they often appear as positional variants, with v used initially (e.g., “vser”) and u medially (e.g., “auoir”), without reference to their phonetic value.Footnote59 Similarly, the letters i and j could both be used for both vocalic [i] and consonantal [ʒ] (e.g., “ie”).Footnote60 Furthermore, some letters found in modern French, such as k and w, were not part of the basic alphabet although they might have been needed to spell some foreign names. Those particularities were also reflected in cipher tables, and in the reconstructed Mary-Castelnau cipher, as described below.Footnote61

The homophones

and

and  interchangeably represent the letter u as well as the letter v.

interchangeably represent the letter u as well as the letter v.Similarly, the homophones

and

and  may both be used for the letter i as well as for the letter j.

may both be used for the letter i as well as for the letter j.The letter y has a distinct homophone,

.Footnote62

.Footnote62The letter k has distinct homophones,

and

and  , needed to spell English names such as Norfolk.

, needed to spell English names such as Norfolk.Despite the need to spell names like Walsingham, there is no homophone for the letter w. For example, Walsingham is most often spelled as “vvalsingham”, and in some cases, “valsingham”.

Accents are disregarded while enciphering, as there are no dedicated symbols to represent letters with accents. Similarly, spaces and punctuation marks are generally not enciphered.

4.9. Comparing the Mary-Castelnau cipher with related ciphers

As mentioned in Section 3.3, the State Papers at the British National Archives contain dozens of cipher keys used by Mary and her associates that were captured or reconstructed from intercepted messages by Walsingham’s and Burghley’s agents.Footnote63 The famous cipher used in the Babington plot is of the simplest kind, a monoalphabetic substitution cipher with a small nomenclature. However, most of the other ciphers in those archives are homophonic and include a nomenclature with names, places, and either French or English common words. Most ciphers employ graphical symbols, sometimes with diacritics.

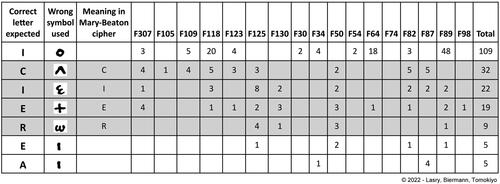

The reconstructed Mary-Castelnau cipher does not appear in the archive collections listed in Section 3.3, but other ciphers share several features with it. One of them is a homophonic cipher between Mary and Châteauneuf, French ambassador in London after Castelnau.Footnote64 Some parts of the cipher table are shown in . It includes nulls and symbols for repeating or deleting the last symbol. It also includes symbols for punctuation, months, and numbers. Its nomenclature is extensive, with many entries also appearing in the Mary-Castelnau cipher. It also employs diacritics, some similar to those of the Mary-Castelnau cipher.

The reconstructed Mary-Castelnau cipher also resembles a cipher, shown in , held in a collection of Castelnau’s papers from his time as ambassador in London.Footnote65 The two ciphers have similar diacritics and similar nomenclature vocabularies.

Figure 16. A cipher found in Castelnau’s papers (Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF 500 de Colbert 472, p. 347).

Interestingly, diacritics were not very common in French diplomatic ciphers of the time. For example, contemporary ciphers used by the French ambassadors in Rome, Venice, Spain, and Constantinople did not feature diacritics.Footnote66 It is unclear whether the Mary-Castelnau cipher was designed by Mary and her associates or was based on other French cipher designs, and assessing its origin requires further research.

5. The deciphered letters

In this section, we examine the inventory of the newly deciphered letters from Mary to Castelnau, we briefly highlight some of the topics those letters deal with frequently, and we provide a summary of the contents of each letter, with some letters reproduced in full.

5.1. Inventory and timeline

Among the 57 letters we deciphered as part of this work, 54 are from Mary to Castelnau. Two additional letters (F307, F198) are from Mary to de la Mothe-Fénelon, Henry III’s envoy to Scotland toward the end of 1582. A third one is from Jacques Nau, Mary’s secretary, to Jean Arnault (F249).Footnote67 All letters except one (F308) are dated, that is, the month and the day of the month are mentioned – in cipher, and we were able to attribute the year based on contents and historical context. The newly deciphered letters were written while Mary was under the custody of the Earl of Shrewsbury, from Sheffield or from another of his properties. Among the letters from Mary to Castelnau we deciphered, the earliest is from May 1578 (F87), the latest fully in cipher is from May 1584 (F221), and the latest – only partially enciphered – is from 30 October 1584 (F57). For comparison, the earliest known letter in clear from Mary to Castelnau is from March 1576,Footnote68 and the latest is from March 1586,Footnote69 after Castelnau had already returned to France.

We needed to determine whether there were other letters from Mary to Castelnau, apart from those we deciphered, that were originally sent in cipher, although only a plaintext copy may be found in archives, e.g., a leaked copy of the original plaintext. This process can be challenging,Footnote70 but we were able to establish that three of the previously known letters were likely to have been sent in cipher,Footnote71 while their ciphertext version is not in the BnF letters we deciphered. In addition, we have been able to locate the plaintext of seven newly-deciphered letters in British archives (F42, F46, F58, F69, F78, F96, F221), which were probably leaked from Castelnau’s embassy. Apart from those ten letters in cipher (seven plus three mentioned above), it is reasonable to assume that the remaining previously known letters were sent in clear, though this is not certain except for those which are known to be the original, e.g., those that have an autograph signature. To the best of our knowledge, the remaining 45 newly deciphered letters from Mary to Castelnau do not appear in archival sources surveyed as part of this work (listed in Section 3).Footnote72

Often, letters written in cipher from Mary to Castelnau would refer to previous letters sent to him in cipher. In addition, at least eight letters from Castelnau to the French court refer to letters in cipher that Castelnau had received recently from Mary.Footnote73 We have identified three enciphered letters from Mary to Castelnau that match those referenced letters. The remaining five referenced letters could not be identified, indicating that they might have been lost.

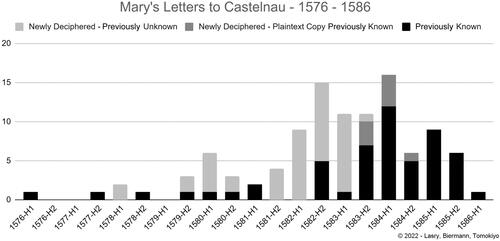

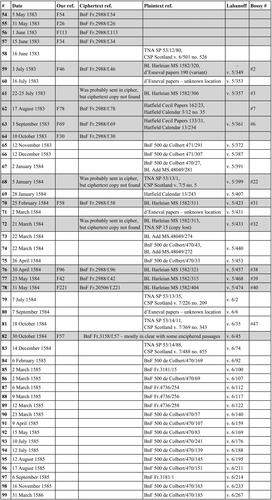

In Appendix C, we list the newly deciphered letters together with previously-known letters found in archives, and together they constitute an up-to-date combined corpus of letters from Mary to Castelnau, with almost one hundred letters in total. To contextualize our new decipherments, we show in a breakdown of the letters in the combined corpus over 6-month periods from 1576 to 1586, dividing the letters into three categories:

Newly deciphered letters and previously unknown.

Newly deciphered letters for which a plaintext copy was previously known.

Known letters.

We can roughly divide the combined corpus of Mary-to-Castelnau letters into five periods:

1576-1579: It is not fully clear why there are so few letters in this four-year period, with only four newly deciphered letters and four previously-known letters in clear. A secure channel to convey enciphered letters could have faced some challenges, as evidenced by Mary complaining in May 1578 that she had not received any letters in the previous eight months (F87). Also, two enciphered letters are referenced in other letters but we could not find them in the combined corpus,Footnote74 hinting at the possibility that additional letters from this period were exchanged but may not have survived.

1580-1581: There are 11 newly deciphered letters from this period in addition to four previously-known letters written in clear. Only six of nine enciphered letters referenced in other letters are included in the combined corpus, so some letters exchanged during that period may also have been lost.Footnote75

1582-mid-1583: At this stage, the confidential communication channel between Mary and Castelnau was probably secure and stable, involving multiple trusted couriers, and the volume of letters significantly increases, with 29 newly deciphered letters. In addition, there are six letters written in clear and most probably delivered under Walsingham’s supervision. Nine enciphered letters are referenced in other letters, and as all except one can be matched with letters in the corpus,Footnote76 we estimate that the majority of the enciphered letters from Mary to Castelnau from that period are included in this corpus.

Mid-1583-1584: In mid-1583, Walsingham was able to recruit a mole in the French embassy and he obtained leaked copies of letters from and to Castelnau.Footnote77 The plaintext of most of our newly deciphered letters from that period, seven of eight, can be found in British archives, in addition to the plaintext copies of three letters originally written in cipher for which we did not find a ciphertext in the BnF archives. It would seem that the leak from the embassy was quite effective and comprehensive.Footnote78

1585-1586: Following the discovery of the Throckmorton plot, Castelnau had apparently agreed to discontinue the exchange of enciphered letters with Mary. All the letters from that period were previously known, and all of them are fully in clear. Some of them were sent by Mary to Castelnau after he was replaced in September 1585 as French ambassador to England.

In summary, our new decipherments significantly enlarge the corpus of letters from Mary to Castelnau available for historical research, accounting for 45 of a total of 99 letters. For the period from 1580 to mid-1583, our new decipherments account for about 80% of the corpus. They also account for the vast majority of the letters sent in cipher (45 of 55) and for all the letters in cipher before July 1583.

5.2. Main topics covered in the letters

Mary’s secret letters highlight a multitude of topics, of which only a few are mentioned in this section.

A major recurrent topic has to do with Mary’s efforts to maintain a secure communication channel with Castelnau, and through him, with her network of associates and allies, mainly in France. Careful precautions were taken to conceal and protect this critical channel, the deciphered letters showing that it was in place as early as 1578 and active until at least mid-1584. This confidential channel operated in parallel with an official channel under Walsingham’s supervision through which, in Mary’s own words, she would never write anything that she did not want even her worst enemies to be able to read.Footnote79

Another recurrent topic in the letters is the proposed marriage between the Duke of Anjou and Queen Elizabeth. While Mary pledges her support for the marriage, often vehemently defending herself against accusations she is in fact opposing it, she constantly warns Castelnau that the English side is not sincere with their negotiations, their only purpose being to weaken France and counter Spain, by encouraging the duke to attack Spain in the Low Countries.Footnote80 After the duke’s campaign in Flanders ends up in disaster, as she had been warning all along,Footnote81 Mary offers to help in reconciling the duke with the king of Spain.Footnote82

In several letters, Mary expresses a strong animosity toward the Earl of Leicester,Footnote83 a longtime favorite of the queen, and toward other members of the Puritan faction, whom she accuses of fomenting plots against her, her son James, and even against Queen Elizabeth, such as a scheme to marry Leicester’s son to Arbella Stuart,Footnote84 granddaughter of Mary’s hostess the Countess of Shrewsbury, with the intent of claiming the succession to the English throne. Mary is often writing to Castelnau on those alleged plots, advising him to report them to the queen, but without mentioning that the information came from her.Footnote85 Francis Walsingham is also frequently mentioned in the letters, Mary warning Castelnau of his schemes in France and Scotland,Footnote86 describing him in negative terms, as a cunning person, falsely offering his friendship while concealing his true intentions.Footnote87

A series of letters from the second half of 1582 highlights Mary’s frantic response to the news on the abduction of her son James by a Scottish faction (the Ruthven Raid),Footnote88 desperately asking for help from France. When the French king finally sends an envoy to Scotland, Mary expresses her dissatisfaction at the results and her feeling that she and her son have been abandoned by France.Footnote89

Several letters refer to negotiations about Mary’s release and her reestablishment to the Scottish throne in association with her son, in return for her giving up all claims of succession to the English throne. The letters report on several visits by Robert Beale and other commissioners on behalf of Queen Elizabeth, Mary initially hoping that an agreement may be achieved, but bitterly reaching the conclusion that the commissioners either didn’t have the required mandate, or that those negotiations were not in good faith, and no more than an attempt to gain time or extract intelligence from her.Footnote90

Mary’s complaints about her conditions in captivity, and her requests to improve them are frequently mentioned in the letters. The letters also deal with matters related to her dowry in France, and her efforts to ensure that her servants and allies are financially rewarded. From time to time, she suggests enticing various people with financial rewards so that they would switch sides, or soften their attitude toward her.Footnote91 She also asks for Castelnau’s assistance in recruiting new spies and couriers, while sometimes she warns him – rightly – that some people working for her might be Walsingham’s agents.Footnote92

By nature, the contents of letters exchanged in cipher via a confidential channel are expected to be more revealing than the contents of official letters. However, while some of the letters were exchanged at the time of the Throckmorton Plot in 1583, even mentioning Francis Throckmorton as a trusted courier,Footnote93 they do not contain any details about the plot, which is only indirectly alluded to after it had been exposed, Mary deploring Throckmorton’s suffering after his arrest.Footnote94

5.3. Summaries of the letters

In this section, we provide preliminary summaries of the contents of each newly deciphered letter, and in some cases, we provide a full decryption together with a tentative translation.Footnote95 The plaintext of seven of the deciphered letters appears in known sources.Footnote96 For those letters, only the parts that differ from or are missing from the known copy are summarized.

We also tentatively dated the letters. Since the month and the day of the month are written in the letters (in cipher), we only needed to identify the correct year of each letter, based on contents and historical context.Footnote97 For each document, we provide evidence for the assigned year in a footnote. All years are considered to start on January 1st. Also, although the Gregorian calendar was introduced in October 1582 and adopted in France in December, with a 10-day shift, there is evidence that Mary continued to use the old calendar style long after October 1582,Footnote98 and for convenience, all the dates given below follow the old style.

Most of the letters were written in Sheffield, as indicated by a special symbol in the enciphered letter. The other locations, Chatsworth, Wingfield, and Worksop, are spelled out in cipher.

Mary’s letters to Castelnau often enclosed letters to be forwarded to her contacts, mostly in France. These enclosures and their intended recipients were usually mentioned – in cipher – at the end of the main letter, together with a special symbol indicative of each recipient, matching the same symbol used to mark the relevant enclosure so that its recipient could be identified.Footnote99 Since we consider the knowledge of these enclosures to be of importance for research, for each letter we list the recipients of enclosures referenced in the ciphertext. In the archive collections in which we found the enciphered letters from Mary to Castelnau, we could not identify any enciphered copies of letters that would qualify as such enclosures, which may suggest that Castelnau would have forwarded them as requested without keeping copies.

We list the letters and their summaries in chronological order.

Unless mentioned otherwise, “the king” refers to King Henri III of France, and “the queen” to Queen Elizabeth I of England. “The Queen Mother” refers to Catherine de’ Medici.

F87 − 2 May 1578, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 2988 f. 87.Footnote100

Contains an enclosure for James Beaton.Footnote101

Mary complains she has not received any letter for more than seven months. Robertson,Footnote102 a trusted courier, is afraid of being exposed because of news of an alleged interception. Mary proposes to reassure Walsingham of her good intentions, and if her succession rights to the English throne are preserved, as well as those of her son James,Footnote103 she agrees to staying in captivity. She acknowledges that Walsingham is a clever man and may detect any attempt to write letters with contents that are too positive, so she will also include a rebuttal of his accusations against her in a letter she is about to send via the official channel. She claims that Walsingham and the Puritans are acting against the queen, supporting the succession claim of the Earl of Huntingdon,Footnote104 therefore seeing Mary and her son as their enemies. Mary wishes to bring England back to Catholicism, but not by force. She gives her consent for her official correspondence to be read by Walsingham. Mary fears that she might be moved to someone else’s custody, instead of the Earl of Shrewsbury whom she finds decent, and in such a case, her life would be in great danger in the event that Elizabeth dies. Mary thanks Castelnau for his advice on her affairs in Scotland, asking that the king of France support her allies, the Earls of ArgyllFootnote105 and Atholl,Footnote106 who recently recovered some of their authority. She warns Castelnau that MoulinsFootnote107 and CockburnFootnote108 are spies in the service of Morton.Footnote109 She is considering sending a token to the Earl of Leicester, following Castelnau’s advice.

F227 − 12 June 1578, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 227.Footnote110

Contains enclosures for Beaton and Francisco Berthy.Footnote111

Mary thanks Castelnau for interceding with the queen on behalf of the French envoy Hieronimo Gondy,Footnote112 and for mitigating the queen’s bursts of anger against Mary, despite Mary’s respect for her. She also thanks Castelnau for his good services with the Earl of Leicester, Lord Burghley, Walsingham, and Wilson.Footnote113 The Earl of Leicester was at Sheffield this week, but her captivity conditions have worsened instead of being improved as she had been told. Mary fears again that she will be transferred, under the false pretext of reports on the activities in Ireland of Catholics who had been banned, while at the same time, the Earl of Leicester is about to start persecuting the many Catholics in England. Mary wishes to win over Wilson’s wife with presents and money, but this must be done in secret. She is not happy with the plans of the Duke of Anjou in the Low Countries. The queen and her council are planning to support the party opposing those favored by France in Scotland, to prevent France from gaining more influence. The Earls of Argyll and Atholl have been reconciled with Morton, raising Mary’s fears for the safety of her son who is now in the hands of the unreliable Earl of Mar.Footnote114

F249 − 03 October 1579, Jacques Nau to Jean Arnault, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 249.Footnote115

As Nau is sending this letter to Jean Arnault with a new courier, he only writes things of little importance, which is what Arnault is also supposed to do in his reply. Nau reports that letters from Arnault and de ChaulnesFootnote116 sent to Sheffield were opened before they came into the hands of Wilson. Adam BlackwoodFootnote117 from Mary’s council is trying to get his father-in-law to succeed DoluFootnote118 as Mary’s treasurer in France, having also written directly to Walsingham. Mary, however, favors de Chaulnes, Arnault’s brother-in-law, and Nau regrets that some who had previously recommended de Chaulnes now support Blackwood’s claim.

F241 − 8 November 1579(?), Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 241.Footnote119

Mary has now two or three new ways to convey secret letters. She asks Castelnau to update her on the progress of the negotiations on the marriage between the queen and the Duke of Anjou. The anti-marriage faction turns against Mary because she has written to the queen in support for the marriage, also claiming that Mary has thus harmed the public interest. She asks Castelnau to convince the queen that she has no one in her realm to better rely upon than Mary, who in turn has no interest in losing the queen’s goodwill. Mary can’t imagine that the Duke of Anjou has any intentions toward her which are not positive. She thanks Castelnau for helping John Hamilton.Footnote120

F233 − 26 November 1579, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 233.Footnote121

Contains enclosures for Beaton and Robertson.

Castelnau has informed Mary of a calumny against her, being apparently accused of having spoken against the Duke of Anjou.Footnote122 She claims that this is coming from the faction in England which is against the Elizabeth-Anjou marriage, this faction trying to weaken Mary’s friendship with the Duke of Anjou, hoping to attract her to their side, which they could not achieve by their previous mischievous actions, on which Mary promises to provide more details later. Mary does not believe the calumny was invented by the queen. She asks Castelnau to plead that the queen investigate the origin of this slander.

F179 − 6 January 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 179.Footnote123

Contains an enclosure for Beaton.

Although FowlerFootnote124 had started the slander by reporting accusations against Mary,Footnote125 she believes that it was concocted by the faction opposing the marriage. She requires again that Castelnau ask the queen to investigate the matter and Fowler in particular, who knows about intrigues by the Puritans against the marriage and against Queen Elizabeth. Wilson has written to the Earl of Shrewsbury, denying the accusations against Mary. Mary has learned that the Earl of Leicester has been selling his properties, and some think he may retire if the marriage takes place. The Puritans, currently too weak to act, are allying with the Scottish rebels, openly objecting to the rule of women. It is feared they may capture both the queen and Mary.Footnote126 Mary wants Castelnau to ask the queen to write a letter to her host, the Earl of Shrewsbury, recounting her trust in him, to prevent him from joining the Puritan faction. Although the Earl of Leicester has denied to the queen that he had married the Countess of Essex,Footnote127 the latter has been signing her secret letters as “L. Leycester” for more than a year, and Castelnau should use this information against him. The Earl of Leicester told Mary that she owes him her life as the queen once wanted her dead. Mary has arranged for costly silverware to be given to Wilson. She complains about an apothecary, who was sent to her by Adam Blackwood, having worsened her condition.

F231 − 7 January 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 231.Footnote128

Contains an enclosure for Beaton.

Mary asks Castelnau to find out who has convinced the queen to have her letters to him opened in the Privy Council, although she is not concerned about their contents, as in such letters sent via the official channel, she would never write anything she doesn’t want even her worst enemies to be able to read. Castelnau should reassure the queen of Mary’s affection and sincerity. Mary is happy about the possibility mentioned by Castelnau that the queen may convert (to Catholicism) if the Elizabeth-Anjou marriage takes place. She warns Castelnau that Walsingham falsely presents himself as a friend, hiding his real intentions. She fears that her host and hostess may join the Earl of Leicester and the Earl of Huntingdon against her, and she asks Castelnau to find out more from Wilson.

F181 − 15 January 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 181.Footnote129

Contains an enclosure for Robertson.

This letter is being delivered by a new trusted courier, and Mary is asking Castelnau to report to her via him on the latest developments around the Elizabeth-Anjou marriage, and the upcoming session of the parliament, fearing that her enemies may drive decisions against her and the Catholics. She would like Castelnau to recommend her cousin John Hamilton, who has been opposing Morton, to the king of France. The Earl of Leicester has fallen from grace, for which Mary feels sorry. The anti-marriage faction is causing disturbances in France to divert anger directed at them. Representatives from England were sent to the (Protestant) synod of Montauban and to another location,Footnote130 Walsingham driving those efforts, with the ultimate purpose of converting all Frenchmen to be Huguenots. The faction opposing the marriage also spreads rumors that James is very sick. Mary informs Castelnau that Fowler has admitted that his (false) testimony was given at the request of the Earl of Leicester. She pledges that any further negotiations she may undertake would only be conducted via Castelnau.

F38 − 20 January 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 2988 f. 38.Footnote131

We reproduce here the full decryption and a tentative translation.

Monsieur de Mauvissiere, d’autant que sur l’arrivee prochaine du duc d’Anjou mon beau frere en ce royaume on seme divers bruictz autant a son desadvantage que pour irriter ses meilleurs amyz contre luy et les mectre en deffiance de sa bonne et droicte intention vers eulx, je vous diray seulement que vous debvez adviser ledict sieur duc d’Anjou lorsqu’il sera par deca de ne persister en la requeste qu’on dist qu’il a faicte pour le restablissement du comte de Leicester duquel il n’a besoing de se fortiffier et moins de craindre la force et puissance en y pourvoyant de bonne heure. Je scay que quelques catholiques en ont ja esté fort offensez, craignans de se voir derechef soubs les persecutions du temps passé ce qui les rendra constamment affectionez au duc d’Anjou d’autant plus qu’ilz le verront animé contre leurs communs ennemis.

Excusez moy vers luy de ce que je ne luy ay encores escript, craignant de le mectre en soubcon et de nuire a ses negociations, lesquelles cependant je ne fauldray d’assister de tout ce que je pourray par mes amyz. Comme cy devant je vous ay mandé, je remectz a sa courtoisie et a vostre bonne intercession les bons offices que j’espere de luy pour mon traictement en ceste captivité, la conservation de ma personne et droictz en ce royaume.

Je desirerois infiniment pourchasser une seconde visitation vers mon filz considerant l’estat present des affaires d’Escosse qui s’y offre fort a propos, mais j’apprehende le soubcon qui en pourra naistre en divers endroictz de sorte que je suis en opinion d’actendre jusques apres les nopces qu’on m’asseure debvoir estre avant ce karesme.

Si en ce prochain parlement on traicte de la succession, souvenez s’il vous plaist d’en parler a la royne d’Angleterre de ma part et d’en faire les mesmes remonstrances que je vous ay aultresfoye escriptes sur le mesme subject et occasion, a quoy me remectant je ne vous feray ceste plus longue que pour prier Dieu vous avoir en sa saincte garde.

Escript a Sheffeild ce vingtiesme janvier.

Translation:

Monsieur de Mauvissière, since with the forthcoming arrival of the Duke of Anjou, my brother-in-law, in this kingdom various rumors are being spread as much to his disadvantage as to irritate his best friends against him and to put them in distrust of his good and upright intention toward them, I will only tell you that you must advise the said Duke, when he is here, not to persist in the request that he is said to have made for the rehabilitation of the Earl of Leicester, whom he does not need in order to fortify himself, and he needs even less to fear [Leicester’s] strength and power if he takes care of it in good time. I know that some Catholics have already been greatly offended by this,Footnote132 fearing to see themselves again under the persecutions of the past. Such fear will make them constantly affectionate toward the Duke of Anjou, all the more so if they see him animated against their common enemies.

Apologize to him on my behalf for not having written to him yet, for fear of putting him under suspicion and of harming his negotiations, which however I will not fail to assist with everything I can through my friends. As I have already written to you, I leave to his courtesy and your kind intercession the good services I hope for from him for [the improvement of] my treatment in this captivity, the preservation of my person and of my rights in this kingdom.

I would like very much to pursue a second visit to my son, considering the present state of affairs in Scotland, which seems quite appropriate, but I fear the suspicions that may arise in various places, so I am of the opinion that I should wait until after the wedding, which I am being assured will be before this Lent.

If in this next parliament the succession is dealt with, please remember to speak to the queen of England on my behalf and to make the same pleas that I previously wrote to you on the same subject and occasion, by repetition of which I am not going to prolong this letter, but for praying to God to keep you in his holy protection.

Written in Sheffield this twentieth of January.

F105 − 20 February 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 2988 f. 105.Footnote133

Contains an enclosure for Beaton.Footnote134

Mary has informed Castelnau via Robertson that her host, the Earl of Shrewsbury, is sick. The Elizabeth-Anjou marriage project seems to be postponed or uncertain, cooling down those who support the Duke of Anjou. Mary is threatened by the party of the Earl of Leicester who is acting jointly with the Earl of Huntingdon, her mortal enemy. Mary is being accused of being too supportive of French interests. The Earl of Leicester is openly working against France, and Stafford,Footnote135 goaded by Lady SheffieldFootnote136 who is now reconciled with Leicester, is spreading some sinister rumors about the duke, whom Castelnau should warn. Rumors of a quarrel between the Earl of Leicester and the Earl of OxfordFootnote137 are saddening Mary, because of her good memory of the Duke of Norfolk,Footnote138 and Castelnau should convey to the Earl of SurreyFootnote139 that Mary considers him as her second son. Mary is also pleased that the latter’s sister has married Lord Buckhurst.Footnote140 While the Earl of Shrewsbury was not as close to death as they say at court, she nevertheless expects him to die in the near future. She therefore asks Castelnau to ensure her safety by secretly trying to influence the choice of her new guardian, and Robertson, who knows very well the nobles of this country, can advise him on that matter. Mary has met MyldemurFootnote141 the day before, discussing matters related to the security of the queen and of Mary. Castelnau should thank the queen for granting a passport to Mary’s physician and plead for Mary if he meets Claud Hamilton.Footnote142

F237 − 16 September 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 237.Footnote143

Contains enclosures for Beaton and Robertson.

Mary asks Castelnau to support Robertson on his way to France. She fears that she might be removed from Sheffield and asks Castelnau to discuss the matter with Lord Burghley.

F239 − 27(?) September 1580, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield(?)

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 239.Footnote144

Some parts of the manuscript are damaged.

Mary asks Castelnau to further assist Robertson, so that he is presented to the king and the Queen Mother, and granted a pension, and to plead to the Duke of Anjou and to SimierFootnote145 on Robertson’s behalf, but without herself being mentioned. The Earl of Huntingdon, supported by the Earl of Leicester, is trying again to become her new keeper. Mary fears that France is neglecting Scottish affairs because of the marriage negotiations, and as a result, James might be driven toward a course different from hers and her predecessors’.Footnote146

F98 − 31 July 1581, Mary to Castelnau, Chatsworth

Reference: BnF Fr. 2988 f. 98.Footnote147

Contains enclosures for Beaton, for a relative of Thomas Morgan, and for Françoys Levin.Footnote148

Mary is disappointed by the lack of support from French envoys, which would be a good reason for her to negotiate with Spain, but she denies rumors to that regard. She would not seek protection from powers other than France unless she is forced to, and it is in the interest of the king to maintain her support and the support of her friends. Mary warns Castelnau that despite the Duke of Anjou’s trying to accommodate the faction against the marriage, those of this faction are mocking him. Also, the king should be warned of Walsingham’s hostile activities while in France. Mary learned that the Earl of Leicester and Lord Burghley are acting in concert with Spain against the Duke of Anjou in the Low Countries. Mary’s enemies are also trying to assume control over her son in Scotland. She fears that Castelnau might be replaced by another ambassador who would not support her. Her movements have been further restricted, with negative effects on her health. Mary asks Castelnau to plead with Lord Burghley that she be allowed to exercise and to use her carriage, as she cannot walk or ride anymore.

F185 − 18 September 1581, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 185.Footnote149

Contains enclosures for BeatonFootnote150 and Thomas Morgan.

Mary has learned from Castelnau and others that France is aware of Walsingham’s actions in Scotland in concert with the Earl of Angus.Footnote151 She complains that the queen is becoming more hostile toward her, despite Mary not giving her any reason. As a result, a letter sent by Mary to the queen has been delayed. Her host is allowing her to exercise again. James has asked Mary to recognize him as king of Scotland and has sent George DouglasFootnote152 to France. Mary is waiting for a letter from the king and the Queen Mother before answering James, and she asks Castelnau to find out their opinion on the matter. She would also like him to plead with the queen to accept a request by James to send an envoy to Mary, and if James makes such a request, to also allow her secretary Nau to visit James in Scotland. Castelnau had asked Mary to be granted the post of seneschal of Poitou, which is part of her dowry, but she cannot grant it as it is currently occupied by Viverox,Footnote153 son-in-law of the late Puiguillon.Footnote154

F194 − 20 October 1581, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 20506 f. 194.Footnote155

Mary is worried that an important letter she sent to Beaton via Germain HertonFootnote156 has not been delivered, as it contains details about negotiations for an association whereby James and Mary are to jointly hold the Scottish crown. She asks again that Castelnau plead for the queen’s permission to send Nau to Scotland, and in that case, he may be accompanied by a representative of the queen. Mary is again worried she will be removed from her current host’s custody and asks Castelnau to find out more on that subject, and on the planned visit to her by Robert Beale.

F82 − 6 November 1581, Mary to Castelnau, Sheffield

Reference: BnF Fr. 2988 f. 82.Footnote157