Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious disease which is difficult to treat. Little is known about the recovery from AN, and therefore, this review’s aim was to review and synthesise patients’ experiences and perceptions of what is meaningful for recovery from anorexia nervosa while having contact with psychiatric care. Cinahl, PubMed, and PsycINFO were systematically searched, and 24 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Three themes were identified: Being in a trustful and secure care relationship, Finding oneself again, and Being in an engaging and personal treatment. Efforts supporting staff learning and person-centred care should be emphasised and researched further.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious psychiatric disorder with high mortality rates (Meczekalski et al., Citation2013; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2009). About 5% of patients suffering from anorexia nervosa die (Meczekalski et al., Citation2013). AN is characterised by an intense fear of gaining weight, even though the individual is significantly underweight, with a reduction in calorie intake and in dietary variety (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Furthermore, the disease is associated with several morbidities, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, anxiety disorder, depression, and osteoporosis (Meczekalski et al., Citation2013; Steinhausen, Citation2002). The increased risk of fractures does not disappear after the recovery of the disease but remains elevated (Meczekalski et al., Citation2013). Finding ways to support recovery from AN in psychiatric care is important, and synthesising the literature from the patients’ perspective could provide a valuable understanding of what patients themselves emphasise as meaningful for their recovery.

AN causes great suffering due to several factors, such as social isolation, relational and work-related problems, and somatic health problems (Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment & Assessment of Social Services, Citation2019). It is, however, well known that individuals with AN often also experience positive feelings in relation to the illness due to, for example, the sense of control (Espeset et al., Citation2012; Lavis, Citation2018; Williams & Reid, Citation2012). Considering these contradictory experiences of AN, it is not surprising that many individuals feel ambiguous towards treatment and recovery, with high relapse and dropout rates (Gregertsen et al., Citation2017; Khalsa et al., Citation2017; Wallier et al., Citation2009) that impact the recovery process.

The concept of recovery has been suggested to play a central role in today’s mental health care (van Weeghel et al., Citation2019). Over the last decades, several definitions have been suggested. Early definitions often focussed on clinical or medical recovery (Collier, Citation2010), but in the 1990s, the complexity, personal factors, and lingering process of recovery were acknowledged (Anthony, Citation1993). Furthermore, in research, recovery is sometimes used interchangeably with overlapping but distinct concepts, such as remission and “good outcomes”, which complicates the search for a common understanding of recovery from AN (Bardone-Cone et al., Citation2018). Overall, recovery can be understood as embracing both the medical aspects and the personal and social aspects, but above all, recovery is a personal journey that emphasises growth, values, optimism, meaning, relationships, and empowerment (Anthony, Citation1993; Topor et al., Citation2011; van Weeghel et al., Citation2019).

Literature reviews are important in appraising the situation in a field, and several reviews have focussed on the treatment and management of AN (see, for example, Graves et al., Citation2017; Watson & Bulik, Citation2013; Zeeck et al., Citation2018). However, these reviews have not focussed on the recovery process from the patients’ perspective, which is important to understanding the meaning of behaviours and experiences; otherwise, there is a risk of leaving the patient unheard (Gregertsen et al., Citation2017). A few reviews based on qualitative studies have specifically focussed on the recovery process in AN. Duncan et al. (Citation2015) conducted a meta-ethnographic review on recovery that included eight articles. They found that recovery is a dynamic process where the search for identity and need for personal power and control are important in the recovery process. Another review of 14 qualitative studies found that recovery from AN in women is a complex psychological process with a need to reach a turning point in order to start the recovery journey. This review also emphasised the importance of identity and control (Stockford et al., Citation2019). None of these reviews, however, presented a specific focus of recovery when there was contact with psychiatric care. We performed a literature review of the extant literature with the aim of reviewing and synthesising patients’ experiences and perceptions of what is meaningful for recovery from anorexia nervosa while having contact with psychiatric care.

Material and methods

The review was conducted in compliance with Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016) method for conducting systematic literature reviews, which was used throughout the research process.

Selection and literature search

Three electronic databases (Cinahl, PsycINFO, and PubMed) were systematically searched for suitable publications. Blocks of keywords and subject headings were designed according to the PEO model (Bettany-Saltikov & McSherry, Citation2016): Population: patients with anorexia nervosa; Exposure: recovery from anorexia nervosa; Outcome: patients’ experiences and perceptions. Keywords/subject headings that were synonymous or related to the PEO blocks were identified for the search strings. A search string was then conducted by combining the keywords/subject headings with the Boolean operator OR and then with AND to complete the search string. The words were truncated to increase the number of hits in the free text searches.

The articles that were selected related to patients’ experiences/perceptions of what was meaningful in the recovery of anorexia nervosa while having contact with psychiatric care. The articles concerned different types of psychiatric care contexts, that is, both inpatient, outpatient and community care. In several cases, patients experiences were related to several psychiatric care contexts which they had contact with during many years of treatment before reaching recovery. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed, English-language studies with qualitative design, original articles, published from 2009, and with patients 13 years and older. Articles were excluded if they lacked research ethical information.

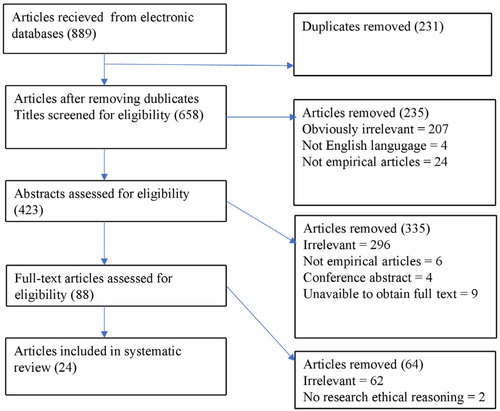

Systematic searches were conducted in the databases Cinahl, PubMed, and PsycINFO and yielded 889 articles, of which 231 were duplicates. A three-stage screening process was undertaken for the 658 remaining articles. First, the titles were screened against the inclusion criteria, and 235 were removed. In the second stage, 423 abstracts were read, and a further 335 articles were removed. Finally, 88 full-text articles were read, and 64 were eliminated. Twenty-four articles remained and were critically assessed for methodological quality. Please see the flow chart in for details of the search and screening process.

Quality assessment

The 24 included articles were assessed for methodological quality using a template designed for the quality assessment of articles that use a qualitative design (Caldwell et al., Citation2011). The template comprises 18 questions, and each question is given a score between 0 and 2, depending on the richness of the article’s methodological information. A total lack of information gives 0 points and a full description 2 points. Two authors evaluated each article together, with high consensus regarding quality scores. Discrepancies regarding vague information from the articles were reconciled through discussion. An assessment was performed for each article based on the quality assessment template, the points for each question were totalled for each article, and the articles were divided into quality categories based on total score: excellent quality, high quality, medium quality, low quality, and very low quality. Twelve of the articles were considered to be of high quality, and 12 were considered to be of excellent quality. The results of the quality assessment are described in .

Table 1. Studies included in the review.

Narrative synthesis

The analysis and synthesis were performed in accordance with Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016) method for analysis in nine steps. First, all articles were read several times with special attention to the results sections. In the next step, meaningful words and sentences from the text of the results that were relevant for the aim of the review were identified and coloured. After this, the coloured text was extracted and put into a new document, one for each article. The fourth step involved a process of open coding by giving the extracted data a label and then classifying data with similar labels into preliminary categories, and in the fifth and sixth steps, the number of preliminary categories was reduced by merging similar categories and removing redundant ones. In the seventh and eighth steps, the preliminary categories were discussed, changed, clustered and condensed to sub-themes and themes. Two independent clinical nurses were asked to read the text of the result and suggest names for themes and sub-themes. The two clinical nurses were registered nurses with a specialist degree in psychiatric care and worked in child and adolescent psychiatric care. The suggested names for the themes and sub-themes were compared with the authors preliminary names in the final step, leading to the final construction of themes and sub-themes.

Results

The systematic search resulted in 24 articles that used a qualitative design and were published from 2009 to 2018 (see for article overviews). Three themes were identified: being in a trustful and secure care relationship, finding oneself again, and being in an engaging and personal treatment.

Being in a trustful and secure care relationship

Being in a trustful and secure patient-caregiver relationship is an important part of the recovery from AN. The relationship is a central part and can reflect whether recovery is possible. It is essential that the patient feel listened to and is met with empathy and that the relationship is characterised by respect and equality. The patient needs to be given time to build a relationship, and treatment should not be rushed to achieve recovery from AN.

Being met with empathy and being listened to

The feeling of being met by empathy and being listened to is an important part of recovery from AN. To build an alliance, the patient feels that the caregiver should possess certain qualities, such as having expert knowledge, showing commitment, availability, clarity, patience, flexibility, giving encouragement, and perseverance. Emotional accessibility and personal chemistry with the caregiver is perceived as a prerequisite for the creation of a good alliance (Lose et al., Citation2014; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Insufficient quality in the relationship with the caregiver often affects the entire recovery process and contributes to feelings of loneliness and isolation (Sly et al., Citation2014). Insensitivity and lack of communication are experienced as increasing anxiety, which can inhibit recovery (Rance et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2016). Yet, feelings of loneliness diminish with the support of a safe environment where the patient feels comfortable and listened to (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Seed et al., Citation2016; Wright & Hacking, Citation2012). A trusting relationship helps patients open up, develop help-seeking behaviour, boost their confidence, and change behaviour (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2016). To change behaviour, it is important that the caregiver is aware of where the patient is in the recovery process and meets him/her there (Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). The experience of being accepted by the caregiver is an important part of the recovery process (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013).

The therapist was the most important person during my recovery, because speaking to her about how I felt and what I thought about, and also feeling accepted by her, were the most healing aspects to me… (Study participant cited in Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013, p. 3–4)

Experiencing a respectful and equal relationship

Patients with AN experience that a respectful and equal relationship with the caregiver is a meaningful part of recovery (Seed et al., Citation2016; Sly et al., Citation2014). If the caregiver is too dominant, this has a negative impact on the recovery process, which can contribute to the patient opposing the treatment to have his or her voice be heard (Sly et al., Citation2014). To build a respectful and equal relationship, patients appreciate when caregivers see their personality (Seed et al., Citation2016; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016), interact with them in a “normal” way (Seed et al., Citation2016), and share experience from their personal lives (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Rance et al., Citation2017; Seed et al., Citation2016). Some patients prefer a more professional than personal relationship, and therefore, the amount of personal information shared by the care provider needs to be adapted to each individual patient (Ramjan et al., Citation2018). A non-judgemental attitude helps maintain a good care relationship (Ramjan et al., Citation2018; Rance et al., Citation2017; Seed et al., Citation2016; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). By avoiding assumptions that affect the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and actions, the feeling of being judged can be counteracted (Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Assumptions based on the patient’s appearance may be experienced as judgmental (Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018), while some patients may be disturbed and impaired if the caregiver does not express concern (Smith et al., Citation2016). When patients feel that they are being treated according to a manual, treatment is not experienced as beneficial (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Rance et al., Citation2017). Physical touch is experienced as meaningful for recovery by signalling the caregiver’s presence and emotional availability, thus increasing the understanding between the patient and caregiver and, as a result, reducing the need for oral communication (Wright, Citation2015).

Getting the time needed

Getting the time needed to build a trusting relationship between patient and caregiver is important for recovery (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Rance et al., Citation2017; Wright & Hacking, Citation2012). Building a trusting relationship takes time (Seed et al., Citation2016), and the patient needs to feel that the caregiver will remain regardless of the treatment’s success and that he/she will continue to demonstrate that recovery is possible (Sly et al., Citation2014; Wright & Hacking, Citation2012; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Short-term treatment can hinder and prevent the development of a trusting relationship (Seed et al., Citation2016). When the caregiver with whom the patient has built a relationship ends his/her service, the work towards recovery is also interrupted, and the possibility of recovery is made more difficult (Hannon et al., Citation2017). Prolonged follow-up after treatment is considered important for the recovery process. Patients need someone to turn to for support if needs emerge, even when treatment is not ongoing (Hannon et al., Citation2017).

Finding oneself again

Recovery can cause patients to feel they are losing a part of themselves, and a meaningful part of recovery is finding oneself again. The disease is perceived to be a large part of the self that affects the identity. Self-esteem and the ability to recover are thus affected, and it is vital to find a balance between the disease and the self to raise awareness of how the disease affects the patient. Fear and ambivalence are emotions that are often experienced in recovery. The sense of control generated by the disease needs to be delivered for recovery to be possible. Hope and motivation are also feelings that are meaningful in overcoming the disease.

Letting go of the disease

Patients with AN find it difficult to let go of the disease, as it is perceived to be part of themselves (Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Williams et al., Citation2016). The disease can cause patients to feel stuck in a life stage and depend on the relationships they have created through the disease (Seed et al., Citation2016). It is therefore important that the caregiver supports the patient in making contact with others outside of the care environment (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Ramjan et al., Citation2018). Identity and self-esteem are affected by the disease, which contributes to difficulties in releasing the disease and recovering (Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018). The disease is perceived to be a large and meaningful part of life (Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Williams et al., Citation2016).

I can see how it is sometimes quite hard to let go of something that has been such a big part of your life that fills you, fills you with a different sort of emptiness… (Study participant cited in Higbed & Fox, Citation2010, p. 318)

The disease is often described as filling a void that the patient needs the caregiver’s help to understand and manage so he/she can approach recovery (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Nordbø et al., Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2016; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). A meaningful aspect of recovery is rebuilding the identity by learning to appreciate, accept, and treat oneself with respect (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Hannon et al., Citation2017; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Williams et al., Citation2016).

I’ve realised recovery is about starting to learn about who you are and being able to accept yourself for that. (Study participant cited in Hannon et al., Citation2017, p. 291)

Creating a balance between the disease and the self is important for recovery and can be done by externalising the disease and, in so doing, becoming aware of the impact of the disease, which increases self-awareness and self-esteem (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2016). Self-esteem is greatly affected by the recovery process (Dawson et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Faija et al., Citation2017; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Hannon et al., Citation2017; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009; Wright, Citation2015), and in conjunction with treatment success, the patient’s self-esteem increases along with feelings of pride (Faija et al., Citation2017; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Increased self-confidence is seen as an important part of achieving change that leads to recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2015; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Patching & Lawler, Citation2009).

I find it difficult to distinguish… what is me and what is the eating disorder… a lot of what my treatment has been is actually finding my own identity. (Study participant cited in Smith et al., Citation2016, p. 23)

The disease can cause patients to experience an internal voice of a controlling nature that creates an internal conflict that affects recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Lose et al., Citation2014). An important part of the recovery process is learning to control the voice through, for example, yoga or writing a letter to the voice, which reduces anxiety, externalises the voice, and contributes to recovery (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Lose et al., Citation2014).

Feeling fear and ambivalence

The recovery process is affected by feelings of fear and ambivalence (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Nordbø et al., Citation2012; Seed et al., Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2016). Patients are afraid of failing to meet their own and surrounding expectations (Nordbø et al., Citation2012; Seed et al., Citation2016). They also fear having to accept the unknown and explore who they are without the disease (Williams et al., Citation2016). Patients fear being punished by caregivers if, for example, they do not comply with restrictions. Fear can, in some cases, be a motivating factor for change, as the fear of being punished can be stronger than the fear of eating (e.g. Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016).

I gained weight and did what I was told out of fear of being punished rather than because I felt supported to get well. (Study participant cited in Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016, p. 5)

At the same time, some patients feel that scare tactics slow their recovery and can cause them to resist treatment (Nordbø et al., Citation2012). Fear of being free from the disease also brings feelings of ambivalence, partly because the disease causes both anxiety and well-being (Dawson et al., Citation2015; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Nordbø et al., Citation2012; Seed et al., Citation2016). For example, malnutrition can contribute to the feeling of being drug-affected or being a better version of themselves, which gives them a sense of well-being that creates ambivalence towards recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2015; Nordbø et al., Citation2012). Ambivalence is experienced as a physical and emotional struggle (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2016) and is compared to being drawn between two opposing forces, where one has a longing to recover and the other desires to remain in the same limited situation (Gorse et al., Citation2013). The desire to recover may be present in patients, but it disappears at, for example, meals due to ambivalence, which is frustrating (Nordbø et al., Citation2012).

Feeling secure and in control

The disease and recovery are affected by control and safety. The feeling of handing over control to the caregiver is experienced as a step towards recovery, which helps the patient overthrow eating disorder rituals (Smith et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Inpatient care is often experienced as contributing to safety and protecting the patient from life stressors (Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2016). In parallel, other patients feel that inpatient care can provide too much security, as they are worried about not being able to maintain their ability to eat when they return home (Smith et al., Citation2016). When patients receive inpatient care, feelings of powerlessness and anxiety can also emerge when they are forced to hand over control (Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2016). Patients worry that they will not receive the same support from outpatient care and risk relapse after discharge (Smith et al., Citation2016).

Patients are strengthened by gaining control of their disease (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2016). The disease itself can sometimes be seen as a management strategy to reduce stress and anxiety (Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018), and patients need to learn new strategies to cope with change, which can bring them the sense of control that is important for recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2015; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016). Helpful strategies include externalising the disease, challenging behaviours, self-awareness, and flexibility (Dawson et al., Citation2015), and without such new strategies, destructive strategies can develop instead (Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018).

Feeling hope, hopelessness, and motivation

The feeling of hope and hopelessness is experienced as having an impact on recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Nordbø et al., Citation2012; Ramjan et al., Citation2018; Wright & Hacking, Citation2012). To know that others who have previously had anorexia nervosa have recovered may contribute to the feeling of hope (Ramjan et al., Citation2018).

Just having someone recovered…gives you hope that…it is possible…and through all the hard work… it’s worth going through it if you can get to that stage—and just like how life is for them now…being recovered… that was helpful. (Study participant cited in Ramjan et al., Citation2018, p. 853)

Also, knowing that there is a life after the disease and that it is possible to overcome it gives patients hope (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016). To overcome the disease and maintain a sense of hope, realistic goals are required (Gorse et al., Citation2013). Another aspect of feeling hopeful and reducing the feeling of hopelessness may be medication (Espíndola et al., Citation2013).

Medication is useful, but it does nothing alone… it helps you feel less depressed, brings back a little hope and the will to try. (Study participant cited in Espíndola et al., Citation2013, p. 3)

The feeling of hopelessness and hope changes during the recovery process, and the feeling of hope increases as the patient approaches recovery (Gorse et al., Citation2013). Another meaningful factor for recovery is motivation (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018). Involvement of relatives increases motivation through their support of the patient (Lose et al., Citation2014; Voriadaki et al., Citation2015). To approach change, it is necessary for the patient to be ready to take the step towards recovery (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Patching & Lawler, Citation2009). Concern about what awaits the patient (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Seed et al., Citation2016), feelings of not being understood, lack of disease insight, internalisation of the disease, and the experience of unhelpful treatment are factors that contribute to low motivation for recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016).

Conversations in treatment about what patients lose in life because of the disease provide motivation for change (Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016), and awareness of what is neglected through life creates a sense of wanting to fight the disease (Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012). Motivation increases, as there is a desire to recover and create new memories (Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018). However, patients who lack goals in life may instead experience feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness (Nordbø et al., Citation2012). A turning point in the feeling of hopelessness may be the desire to reduce the symptoms of the disease (Dawson et al., Citation2014). During the treatment process, when patients realise that the disadvantages of the disease are more than the benefits, it is experienced as a turning point (Gorse et al., Citation2013). The understanding that the disease can lead to death is also perceived as a turning point that can contribute to the will to recover (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Faija et al., Citation2017; Patching & Lawler, Citation2009; Seed et al., Citation2016).

so I was in a really bad way and I think that was really the turning point for me… I could feel that my body was shutting down, and every time I threw up I was getting heart palpitations and cold sweats and blacking out… I pretty much knew if I was going to continue like this I was going to die because this is not normal… I just knew I had to make some changes. (Study participant cited in Patching & Lawler, Citation2009, p. 17)

The fear of contemplating suicide can arise and is described as a turning point when the will to live becomes stronger (Dawson et al., Citation2014).

Being in an engaging and personal treatment

The experience that the treatment is engaging and personal is important to achieving recovery. Information and awareness of the impact of the disease are considered engaging. Also, treatment that is clear and has structure is felt to promote recovery. Individualised care and participation are emphasised as personal and an essential part of recovery. Meeting with other patients and sharing experiences were also described as significant for engagement in recovery.

Getting information and becoming aware

Obtaining information and becoming aware of the illness are important parts of recovery (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Lose et al., Citation2014; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Broad competence of the caregiver is perceived as significant for recovery (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018); this includes teamwork with, for example, the physician, psychologist, and dietician (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018). Cross-professional knowledge, various forms of therapy, medicine, and nutrition are other contributing factors (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013). Patients appreciate receiving continuous information about the physical consequences of being underweight, which increases patients’ awareness of the disease’s impact on their own body (Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Lose et al., Citation2014; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Patients also find that dietary advice is particularly helpful by gaining an understanding of how nutrient content affects the body (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013; Lose et al., Citation2014; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Explanations of how hunger feelings work as well as the body’s need for food can increase security regarding the food situation and can alleviate worry (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013). Information leads to increased insight into the rational and irrational sides of the disease, which facilitates recovery (Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012). Weight gain can also contribute to a more rational way of thinking (Seed et al., Citation2016), and learning to understand one’s own feelings, thoughts, and bodily functions will make it easier to resist the disease and become strengthened to make changes that contribute to recovery (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Lose et al., Citation2014). One way for patients to learn to understand their own thoughts and feelings is to write them down and then reflect on them (Espíndola & Blay, Citation2013).

I got some education on food, I think it’s definitely a faster process than if you just had talking therapy… I found it very useful, all the…information about food and the meal plans. (Study participant cited in Lose et al., Citation2014, p. 135)

Having structure and clarity

Structure and clarity of treatment are considered to be engaging in the approach to recovery (Lose et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). For example, structure is created through individual action plans that contain specific and realistic goals, which also contribute to increased responsibility among patients (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Hannon et al., Citation2017; Seed et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Flexibility in the structure is also important so that the patient is taken into account (Hannon et al., Citation2017; Lose et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2016).

I felt it was very good working with my therapist in terms of adapting it to make it suitable for me. (Study participant cited in Lose et al., Citation2014, p. 133)

When the structure remains the same in the home as in the care, it creates clarity (Van Ommen et al., Citation2009), for example, through similar structures for portions and meals (Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Some things that can disrupt the structure are delays and interruptions by health care providers that influence continuity and negatively affect the recovery process (Lose et al., Citation2014).

Being involved

Influence, participation, and self-determination are personal elements in treatment that are perceived to be essential for recovery (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Seed et al., Citation2016; Sly et al., Citation2014; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2016; Zaitsoff et al. al., 2016). The experience of having a choice elicits feelings of participation (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Sly et al., Citation2014; Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016).

I think that being part of treatment, like, having a say about what I wanted to focus on first, and then working together on a plan based on our discussions, made me want to work harder with her. (Study participant cited in Sly et al., Citation2014, p. 237)

Patients feel that it is important to understand that change must come from themselves, which provides strength for recovery, where participation is of great importance (Smethurst & Kuss, Citation2018). Participation is promoted by seeing the patient as a whole person and not just from the disease perspective (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Rance et al., Citation2017; Seed et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009; Zaitsoff et al., Citation2016). Focussing primarily on diet and weight is not perceived to be beneficial for recovery because it does not consider the whole person (Hannon et al., Citation2017; Jenkins & Ogden, Citation2012; Lose et al., Citation2014; Rance et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2016). Individualised care is described as systematic and compassionate (Fogarty & Ramjan, Citation2016). Treatment that is not tailored to the patient is perceived as frustrating and hindering recovery (Smith et al., Citation2016).

Sharing experiences and feelings

The ability to share experiences and feelings with other patients is found to be engaging and valuable in the recovery process (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Gorse et al., Citation2013; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Patching & Lawler, Citation2009; Smith et al., Citation2016; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009; Voriadaki et al., Citation2015). For group therapy to contribute to recovery, a sense of security in the group is important (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Gorse et al., Citation2013). Meeting with other patients in the same situation can lead to an increased understanding of their own condition and the difficulties that the disease entails (Voriadaki et al., Citation2015).

I started believing I have a problem…just by what everyone else was saying here, because I could relate to it, and I thought “That’s what I feel”… I could not see that before… I was surprised because I thought there was nothing wrong with me. I just thought I had an obsession with eating. (Study participant cited in Voriadaki et al., Citation2015, p. 12)

To gain understanding from other patients is perceived as supportive (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Higbed & Fox, Citation2010; Patching & Lawler, Citation2009; Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Those patients who have progressed further in their recovery process are seen as role models and can help others dare to challenge themselves (Van Ommen et al., Citation2009). Sharing experiences can contribute to new management strategies and thoughts on recovery (Smith et al., Citation2016). After meeting others in the same situation, patients who feel isolated because of the disease may feel secure in new relationships (Gorse et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2016) and value these relationships more than the relationship with their caregiver (Smith et al., Citation2016). Meeting with other patients may also lead to a desire for weight loss, as patients compare themselves to one another (Seed et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2016). Shared experiences, such as having a mentor who has had anorexia nervosa, are perceived to be important for the recovery process (Dawson et al., Citation2014; Ramjan et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

The recovery process in psychiatric care for patients suffering from AN is characterised by the following themes: Being in a trustful and secure relationship, Finding oneself again, and Being in an engaging and personal treatment. A relationship between the patient and the caregiver that is based on trust and security seems to be of importance. Another important part of the recovery process is for the patient to find him/herself again and to feel they are participating in their own care. Furthermore, the caregiver’s knowledge could influence the recovery process.

The character of the caring relationship is important during the recovery process. If the patient experiences that the caregiver listens with empathy in a respectful way and with flexibility and equality, the patient can develop trust and security in respect of the caregiver. However, if the caregiver is unable to show sensitivity and flexibility to the patient and has difficulties communicating with the patient, the relationship can worsen. Similar results have been found in other studies that have revealed the importance of a relationship based on flexibility and on the patient’s wishes instead of on only receiving manual-based care (Berends et al., Citation2012; Darcy et al., Citation2010). According to Darcy et al. (Citation2010), the perceived lack of flexibility in the treatment programme can contribute to patients choosing to end their treatment. Thus, moving towards a person-centred care that focuses on the patient and what is meaningful for him/her (Ekman et al., Citation2015) is essential in order to support recovery from AN. The results of this review also indicate that many patients consider a friendly and personal relationship with the caregiver to be meaningful for recovery. However, when the relationship becomes too friendly, it could be problematic for caregivers in establishing a good relationship and remaining professional. From the caregivers’ perspective, if the relationship becomes too friendly, it could be more difficult for the caregiver to challenge and support the patient in his/her thoughts and behaviour through recovery (Zugai et al., Citation2019). Thus, finding ways for caregivers to maintain a sense of professionalism while still delivering a personal and friendly relationship with the patient is important. Furthermore, from a caring perspective, it is crucial to have a greater focus on patients’ wishes and to increase flexibility in communication.

The results in the present review point out that it is important to give the patient time to build a beneficial relationship with the caregiver. Furthermore, it is also important that the caregiver stay in the relationship independently if the patient shows progress or not in treatment. These results corroborate a study by Gulliksen et al. (Citation2012), which emphasised that, to establish a good relationship with the patient, patience is required from both parties. Moreover, Gulliksen et al. (Citation2015) described that patients’ lack of awareness about their actual situation and their motivation to deal with the situation and have contact with care providers could sometimes lead to involuntary hospitalisation. In such a situation, the patient could experience a loss of safety and control. Thus, to balance between showing patience and not forcing the development of a good relationship could sometimes be problematic, especially when the patient worsens and the starvation goes so far that the situation becomes life threatening.

The present review shows that, when the caregiver shows expert knowledge, the patient feels trust and confidence in the caregiver and the caring relationship, which is important for the recovery process. It also shows that it is important for the patient to experience the treatment as engaging. It has been pointed out by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (Citation2019) that, if caregivers experience that they lack knowledge about AN, it is difficult to help patients handle their difficulties. In addition, the present review also found that patients differ in how they want the caregiver to react in relation to their appearance. For many patients, caregivers’ remarks and feelings about their appearance are considered a sign of caregiver knowledge and professionalism. These findings are supported by previous research, where it has been found that caregivers who immediately share their knowledge about AN at an initial encounter give the patient an impression of being safe and not left alone (Fox & Diab, Citation2015; Gulliksen et al., Citation2015). Williams and Reid (Citation2012) found that, if the patient has a negative experience of the contact with the care, it could cause the patient to avoid seeking help again. Thus, the caregiver’s knowledge about AN as well as the difficulties the patient can perceive are crucial for the patient’s possibility of recovery.

The patient’s perceived low self-esteem could be an obstacle and is important in the processes of finding oneself again and recovering. The findings show that the recovery process is affected by the patient’s perceived low level of self-esteem, a finding supported by Darcy et al. (Citation2010). To be able to recover, an experienced increased self-esteem is important for the patient. At the same time, the patient can experience an increased level of control and a higher level of self-esteem during the treatment period. It has also been pointed out that the search for an identity and recognising the need for personal power and control are meaningful aspects for the patient in the recovery process (Duncan et al., Citation2015; Stockford et al., Citation2019). Brockmeyer et al. (Citation2013) found that patients with lower body weight had a higher level of self-esteem, and this implies that the disease itself could give a feeling of control and pride and could increase the patient’s self-esteem. In the present review, the results show that it is important to support the patient in finding other things to be proud of that are not connected to the disease. A possible way to do this could be to encourage the patient to engage in social activities, school, or work to find an identity that is separate from the disease. Thus, the recovery process is complex in nature, especially when caregivers should encourage the patient to have control. In the interaction with the patient, the caregiver needs to listen carefully and find a balance between having control over the disease and having personal control to help increase the patient’s self-esteem so the patient can find him/herself again.

To perceive that the treatment is engaging and that the patient is participating in the treatment are meaningful elements in a patient’s recovery from AN. To be seen as an individual capable of taking control over the disease and not only as a person with a disease is important when starting the changing process in becoming a healthy individual. When the patient gets the insight that they need to take control over the disease, they have started the recovery process. Still, the patient has to deal with the difficult thoughts about food and weight in connection to the disease. According to the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (Citation2019) and Williams and Reid (Citation2012), it is important to focus on other things than weight, such as the patient’s inner feelings and possible underlying problems causing the disease; otherwise, the patient may not want to seek help in the future. Thus, involving the patient in treatment and focussing on other things than the disease could help the patient recover from AN.

Conclusion

We conclude that the care relationship is a meaningful contributor to recovery from AN. It is important to further understand the complexity of the care relationship that combines the need to be patient while sometimes needing to rush treatment and to find ways to balance this in practice. The knowledge of staff and their ability to share it with patients seems vital for the recovery from AN, and it is therefore important to support staff learning and development of pedagogical skills. For the recovery to be meaningful, patients need to participate in the care, and the care needs to suit the specific individual. Given the complex situation of feeling ambivalence towards recovery, further research is needed that designs and tests caring interventions with the aim of helping patients with this ambivalence. Caring efforts focussing on supporting patients in enhancing their self-esteem and feelings of control should also be emphasised, and further research in that area is needed. The variation of experiences and needs in patients with AN implicates the need for person-centred care and genuine collaboration with the patient in the care in order to support recovery.

Limitations and strengths

This review was conducted using a stringent approach following the recommendations of Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016). There are, however, some limitations that need to be acknowledged in the interpretation of these findings. We only included articles in the English language, which may have led to the exclusion of relevant articles in other languages. Yet, the use of several suitable databases resulted in the inclusion of 24 articles, which made it possible to synthesise the findings in this area. In mixed-methods studies and in studies that provide information from mixed perspectives, we only included qualitative data from the patients with AN. According to Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016), in one step of the analysing process, external colleagues should create preliminary names of themes based on the data retrieved from the articles. In the present review, two colleagues agreed to participate in this step of the process. The suggested names of the themes and sub-themes created by them were very similar to the names created by the authors, which supported our synthesis and the validity of the results. The current review is a narrative synthesis of data extracted from studies with a methodological and conceptual diversity, which should be considered in the interpretation and development of conclusions. Yet, this type of review is a useful summary of the current state of knowledge in relation to experiences and perceptions of recovery in patients with AN.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the Department of Health and Caring Sciences at Linnaeus University.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655

- Bardone-Cone, A. M., Hunt, R. A., & Watson, H. J. (2018). An overview of conceptualizations of eating disorder recovery, recent findings, and future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(9), 79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0932-9

- Berends, T., van Meijel, B., & van Elburg, A. (2012). The anorexia relapse prevention guidelines in practice: A case report. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2011.00322.x

- Bettany-Saltikov, J., & McSherry, R. (2016). How to do a systematic literature review in nursing. CPI Group.

- Brockmeyer, T., Holtforth, M. G., Bents, H., Kämmerer, A., Herzog, W., & Friederich, H.-C. (2013). The thinner the better: Self-esteem and low body weight in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(5), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1771

- Caldwell, K., Henshaw, L., & Taylor, G. (2011). Developing a framework for critiquing health research: An early evaluation. Nurse Education Today, 31(8), e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.11.025

- Collier, E. (2010). Confusion of recovery: One solution. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00637.x

- Darcy, A. M., Katz, S., Fitzpatrick, K. K., Forsberg, S., Utzinger, L., & Lock, J. (2010). All better? How former anorexia nervosa patients define recovery and engaged in treatment. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 18(4), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1020

- Dawson, L., Mullan, B., & Sainsbury, K. (2015). Using the theory of planned behaviour to measure motivation for recovery in anorexia nervosa. Appetite, 84(1), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.028

- Dawson, L., Rhodes, P., & Touyz, S. (2014). “Doing the impossible”: The process of recovery from chronic anorexia nervosa. Qualitative Health Research, 24(4), 494–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314524029

- Duncan, T. K., Sebar, B., & Lee, J. (2015). Reclamation of power and self: A meta-synthesis exploring the process of recovery from anorexia nervosa. Advances in Eating Disorders, 3(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/21662630.2014.978804

- Ekman, I., Hedman, H., Swedberg, K., & Wallengren, C. (2015). Commentary: Swedish initiative on person centred care. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 350, h160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h160

- Espeset, E. M. S., Gulliksen, K. S., Nordbø, R. H. S., Skårderud, F., & Holte, A. (2012). Fluctuations of body images in anorexia nervosa: Patients’ perception of contextual triggers. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(6), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.760

- Espíndola, C. R., & Blay, S. L. (2013). Long term remission of anorexia nervosa: Factors involved in the outcome of female patients. PLOS One, 8(2), e56275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056275

- Faija, C. L., Tierney, S., Gooding, P. A., Peters, S., & Fox, J. R. E. (2017). The role of pride in women with anorexia nervosa: A grounded theory study. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 90(4), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12125

- Fogarty, S., & Ramjan, L. M. (2016). Factors impacting treatment and recovery in anorexia nervosa: Qualitative findings from an online questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0107-1.

- Fox, J. R., & Diab, P. (2015). An exploration of the perceptions and experiences of living with chronic anorexia nervosa while an inpatient on an Eating Disorders Unit: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313497526

- Gorse, P., Nordon, C., Rouillon, F., Pham-Scottez, A., & Revah-Levy, A. (2013). Subjective motives for requesting in-patient treatment in female with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study. PLOS One, 8(10), e77757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077757

- Graves, T. A., Tabri, N., Thompson-Brenner, H., Franko, D. L., Eddy, K. T., Bourion-Bedes, S., Brown, A., Constantino, M. J., Flückiger, C., Forsberg, S., Isserlin, L., Couturier, J., Paulson Karlsson, G., Mander, J., Teufel, M., Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Prestano, C., Satir, D. A., … Thomas, J. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of the relation of therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22672

- Gregertsen, E. C., Mandy, W., & Serpell, L. (2017). The egosyntonic nature of anorexia: An impediment to recovery in anorexia nervosa treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02273

- Gulliksen, K. S., Espeset, E. M. S., Nordbø, R. H. S., Skårderud, F., Geller, J., & Holte, A. (2012). Preferred therapist characteristics in treatment of anorexia nervosa: The patient’s perspective. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(8), 932–941. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22033

- Gulliksen, K. S., Nordbø, R. H. S., Espeset, E. M. S., Skårderud, F., & Holte, A. (2015). The process of help-seeking in anorexia nervosa: Patients' perspective of first contact with health services. Eating Disorders, 23(3), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2014.981429

- Hannon, J., Eunson, L., & Munro, C. (2017). The patient experience of illness, treatment, and change, during intensive community treatment for severe anorexia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 25(4), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2017.1318626

- Higbed, L., & Fox, J. R. E. (2010). Illness perceptions in anorexia nervosa: A qualitative investigation. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(Pt 3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X454598

- Jenkins, J., & Ogden, J. (2012). Becoming “whole” again: A qualitative study of women’s views of recovering from anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(1), e23. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1085

- Khalsa, S. S., Portnoff, L. C., McCurdy-McKinnon, D., & Feusner, J. D. (2017). What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-017-0145-3

- Lavis, A. (2018). Not eating or tasting other ways to live: A qualitative analysis of “living through” and desiring to maintain anorexia. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(4), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461518785796

- Lose, A., Davies, C., Renwick, B., Kenyon, M., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U, MOSAIC trial group (2014). Process evaluation of the Maudsley model for treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa trial. Part II: Patient experiences of two psychological therapies for treatment of anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 22(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2279

- Meczekalski, B., Podfigurna-Stopa, A., & Katulski, K. (2013). Long-term consequences of anorexia nervosa. Maturitas, 75(3), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.04.014

- Nordbø, R. H. S., Espeset, E. M. S., Gulliksen, K. S., Skårderud, F., Geller, J., & Holte, A. (2012). Reluctance to recover in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 20(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1097

- Papadopoulos, F. C., Ekbom, A., Brandt, L., & Ekselius, L. (2009). Excess mortality, causes of death and prognostic factors in anorexia nervosa. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 194(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054742

- Patching, J., & Lawler, J. (2009). Understanding women's experiences of developing an eating disorder and recovering: A life-history approach. Nursing Inquiry, 16(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00436.x

- Ramjan, L. M., Fogarty, S., Nicholls, D., & Hay, P. (2018). Instilling hope for a brighter future: A mixed‐method mentoring support programme for individuals with and recovered from anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5-6), e845. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14200

- Rance, N., Moller, N. P., & Clarke, V. (2017). Eating disorders are not about food, they’re about life: Client perspectives on anorexia nervosa treatment. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(5), 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315609088

- Seed, T., Fox, J., & Berry, K. (2016). Experiences of detention under the mental health act for adults with anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(4), 352–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1963

- Sly, R., Morgan, J. F., Mountford, V. A., Sawer, F., Evans, C., & Lacey, J. H. (2014). Rules of engagement: Qualitative experiences of therapeutic alliance when receiving in-patient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 22(3), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2013.867742

- Smethurst, L., & Kuss, D. (2018). “Learning to live your life again”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of weblogs documenting the inside experience of recovering from anorexia nervosa. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(10), 1287–1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316651710

- Smith, V., Chouliara, Z., Morris, P. G., Collin, P., Power, K., Yellowlees, A., Grierson, D., Papageorgiou, E., & Cook, M. (2016). The experience of specialist inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study from adult patients’ perspectives. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12067

- Steinhausen, H. (2002). The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(8), 1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284

- Stockford, C., Kroese, B. S., Eesley, A., & Leung, N. (2019). Women's recovery from anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Eating Disorders, 27(4), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1512301

- Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. (2019). Ätstörningar. En sammanställning a systematiska översikter av kvalitativ forskning utifrån patientens, närståendes och hälso- och sjukvårdens perspektiv. [Eating disorders. A review of systematic reviews of qualitative research from the perspective of patients, next of kin and healthcare] (Report no. 302). Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. https://www.sbu.se/302?pub=40667

- Topor, A., Borg, M., Di Girolamo, D. I., & Davidson, L. (2011). Not just an individual journey: Social aspects of recovery. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(1), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764009345062

- Van Ommen, J., Meerwijk, E. L., Kars, M., van Elburg, A., & van Meijel, B. (2009). Effective nursing care of adolescents diagnosed with anorexia nervosa: The patients’ perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(20), 2801–2808. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02821.x

- van Weeghel, J., van Zelst, C., Boertien, D., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2019). Conceptualizations, assessments, and implications of personal recovery in mental illness: A scoping review of systematic review and meta-analyses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000356

- Voriadaki, T., Simic, M., Espie, J., & Eisler, I. (2015). Intensive multi‐family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: Adolescents’ and parents’ day‐to‐day experiences. Journal of Family Therapy, 37(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12067

- Wallier, J., Vibert, S., Berthoz, S., Huas, C., Hubert, T., & Godart, N. (2009). Dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: Critical review of the literature. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(7), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20609

- Watson, H. J., & Bulik, C. M. (2013). Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2477–2500. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291712002620

- Williams, K., King, J., & Fox, J. R. E. (2016). Sense of self and anorexia nervosa: A grounded theory. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 89(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12068

- Williams, S., & Reid, M. (2012). “It’s like there are two people in my head”: A phenomenological exploration of anorexia nervosa and its relationship to the self. Psychology & Health, 27(7), 798–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.595488

- Wright, K. M. (2015). Maternalism: A healthy alliance for recovery and transition in eating disorder services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(6), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12198

- Wright, K. M., & Hacking, S. (2012). An angel on my shoulder: A study of relationships between women with anorexia and healthcare professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01760.x

- Zaitsoff, S., Pullmer, R., Menna, R., & Geller, J. (2016). A qualitative analysis of aspects of treatment that adolescents with anorexia identify as helpful. Psychiatry Research, 238(1), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.045

- Zeeck, A., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Friederich, H.-C., Brockmeyer, T., Resmark, G., Hagenah, U., Ehrlich, T., Cuntz, U., Zipfel, S., & Hartmann, A. (2018). Psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontier in Psychiatry, 9(158), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00158

- Zugai, J. S., Stein, P. J., & Roche, M. (2019). Dynamics of nurses' authority in the inpatient care of adolescent consumers with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study of nursing perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 940–949. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12595