Abstract

This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of an experiential compassion-focused group intervention for mental health inpatient staff. Findings demonstrated that although participants found sessions enjoyable, and reported a number of benefits, the group attrition was high. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore issues related to group dropout. Thematic analysis highlighted overarching systemic challenges to attendance, and five key themes emerged: The Nature of the Ward; Slowing Down Is Not Allowed; It is Not in Our Nature; Guilt & Threat; We Are Not Important. Clinical implications, limitations and practice recommendations to support group attendance are also addressed.

Introduction

In the UK inpatient mental health services support a population at the higher end of need and distress, with complex, enduring mental health problems, often admitted against their will, in the midst of a mental health crisis (Heriot-Maitland et al., Citation2014). It is not uncommon for staff to experience or witness verbal aggression or violent behaviour towards patients and staff on the ward (Itzhaki et al., Citation2018), and partake in interventions, like de-escalation, restrain and seclusion (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2005). Staff are legally required to develop and follow detailed care and treatment plans, report incidents in a timely manner and complete many other administrative tasks, whilst also engaging therapeutically with service users. The need to meet legal requirements of completing paperwork and the accountability for failing to do so occurs in the context of increased demands and pressures on National Health Service’s (NHS) mental health services (NHS Digital, Citation2021a), and decreased resources such as staffing or number of beds available in hospitals (Ewbank et al., Citation2020). It has been suggested that this has contributed to the development and maintenance of a task-focused workforce and “fast healthcare” (Crawford & Brown, Citation2011), with reduced time allocated to spend with the patient.

Working in systems under stress and driven by targets may have a negative impact on the well-being of staff. Research suggests that mental health staff appear to have high levels of burnout, secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue (CF; Cetrano et al., Citation2017; Rossi et al., Citation2012). Figley Citation(2002) defines CF as physical and emotional exhaustion and impaired empathy. It is understood that CF occurs because of prolonged exposure to suffering and trauma in service users or feeling unable to provide the care that is seen as appropriate. Most recent research suggests that it is not the compassion fatigue that may be experienced, but empathy fatigue, i.e., the ability to resonate with others’ feelings (Dowling, Citation2018), quite a crucial ability to sustain oneself in a caring profession. Anxiety, stress and depression are consistently the most reported reasons for sickness absence in NHS staff, followed by Covid-19 related reasons (NHS Digital, Citation2021b), with mental health services consistently recording the second highest rates of sickness. Stress, burnout and poorer psychological well-being has been linked to low rates of staff retention and high staff turnover (Robertson & Cooper, Citation2010).

A recent survey by the Royal College of Nursing (Citation2020) reports an increase in nurses considering leaving the profession, citing pay, staff shortages and lack of management support, as the main reasons.

Staff well-being has been found to be associated with patients’ satisfaction and the quality and safety of care (Hall et al., Citation2016; Johnson et al., Citation2017). Reports on the failings in patient’s care in Winterbourne View (Department of Health, Citation2012) and Mid Staffordshire Hospitals (Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry, Citation2013) raised concerns from the public about the lack of compassionate care within the NHS and called for a transformation of care.

Alternative approaches to the traditional model of care have been proposed and developed in recognition that both patients and staff need support in working together towards better outcomes (Health Service Ombudsman, Citation2011; The King’s Fund, Citation2009). Recent literature focuses on the topic of compassionate leadership as a prerequisite for delivering compassionate care (Cole-King & Gilbert, Citation2011; Pedersen & Roelsgaard Obling, Citation2019; Vogel & Flint, Citation2021), with research suggesting that organisations whose leaders have a compassionate leadership style, outperform others (Mountford & Powis, Citation2017).

Gilbert (Citation2009) defines compassion as sensitivity to suffering coupled with a motivation to alleviate it. Compassion involves compassion to the self, to others, and allowing the flow of compassion from others to oneself, with certain attributes and skills necessary in cultivating this flow. His model proposes that the flow of compassion may be blocked in threat-focused organisations. This was suggested by the study of Henshall et al. (Citation2018) where staff working in conditions of threat within their organisation had reduced capacity for compassion to self and others. According to Gilbert (Citation2009), stress and burnout are the result of an over-activation of the threat and the drive emotion regulation systems, and under-activation of the affiliative system, called the rest and digest, or soothing system. Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT) is a promising approach for both non-clinical and clinical populations with a range of difficulties, in particular for those with high self-criticism (Leaviss & Uttley, Citation2015) and other research on compassion mind training suggest many benefits. The study of Henshall et al. (Citation2018) suggested that increased self-compassion and increased compassion received from others within work, was linked with a regulated threat response and predicted the level of compassion for service users and work colleagues. Self-compassion was found to be associated with better sleep and resilience (Cramer et al., Citation2015); increased motivation to self-improve (Breines & Chen, Citation2012); increased empathy and reduced self-criticism (Bazarko et al., Citation2013); reduced burnout, reduced compassion fatigue, increased well-being (Beaumont et al., Citation2016).

There is a paucity of research on interventions for NHS mental health staff (McNally, Citation2019). A recent mixed-methods evaluation (Maben et al., Citation2018) of Schwartz Rounds, introduced in the UK in 2009, suggested that attending rounds had a positive impact on staff, including their experience of compassion. Researchers investigating compassion-focused approaches suggest that the NHS workforce could benefit from support in cultivating compassion towards themselves and each other. Efforts are being made across the UK to develop and implement compassion-focused staff support groups in different NHS settings, however, to date no peer-reviewed literature concerning compassion-focused groups for NHS staff exists.

The study of Heriot-Maitland et al. (Citation2014) which explored the feasibility of group CFT for acute inpatients had high attrition, however showed promising outcomes and was well received by participants. Exploring the impact of attending such groups on inpatient staff was recommended. Examining this as well as reasons for possible attrition is a useful area for research that can inform clinical practice in terms of developing, implementing and evaluating future compassion-focused approaches for this staff group.

Aim

The aim of this feasibility and acceptability study was to explore the experience of a novel compassion-focused group intervention for inpatient mental health staff, and in particular, reasons for non-attendance and drop out from the group.

Method

Ethics

The study received a favourable opinion from Bangor University Ethics Committee, the Health Research Authority, Health and Care Research Wales and the local health board’s Research and Development Department.

Recruitment procedure

Participants were recruited from staff working across local NHS acute adult and older adult inpatient mental health and dementia services. The research was discussed with the senior management of the relevant health board and advertised by the psychologist based in one of the inpatients sites. Convenience purposive sampling was employed as a recruitment strategy, i.e., those who expressed an interest in attending the group and participate in the interview, and those who the ward managers identified as experiencing high levels of stress, and expressed interest, were invited to take part. Recruitment was limited as the group intervention was planned to consist of maximally seven members due to the availability of human, time and room resources.

A total of 13 participants were identified and invited to take part in the study consisting of attending the group, completing questionnaires and participating in an interview. One participant who was unable to complete the first group, was invited to attend the second one. Of those 13 ten gave consent to take part in the research and of those, eight were interviewed and received a £15 Amazon gift voucher in acknowledgment of their contribution to the study. At the end of the group the researcher contacted all participants who attended at least one session of the group and had given consent to take part in the study, to check if they still consented to take part in an interview.

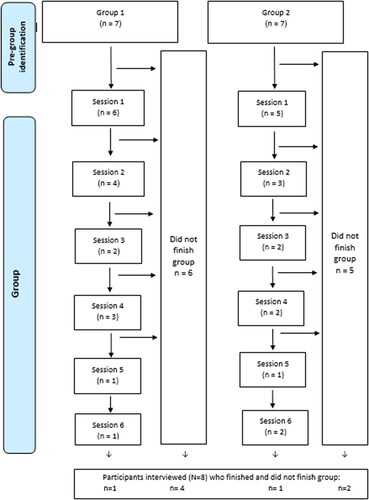

The number of participants who attended, did not attend the group and were interviewed can be found in .

Participants

The participants were health care staff with varied seniority and qualifications—nurses, assistant psychologists, health care assistants and activity coordinators. The majority was White British and identified as female. The modal age group was 35-44. The mean duration of NHS employment was 3 years and 9 months (SD = 2 years).

Intervention

Two closed groups ran consecutively on two different NHS inpatient sites in Wales, in the autumn of 2019. Each group consisted of six weekly sessions of two hours duration. The groups were facilitated by two clinical psychologists trained in Compassion-Focused Therapy (Author 2 and 3). Following a brief introduction to the model of compassion, the participants learned and participated in compassion cultivation practices, such as soothing rhythm breathing and compassionate imagery. Space was also facilitated for participants to reflect on these practices. As such, the sessions were not psycho-educational workshops, but experiential groups with an aim to facilitate a safe space enabling affiliative relating to each other between participants, and the development of a “compassionate mind” through the experiential practices.

Method of evaluation

A mixed methods design was employed. Participants were asked to anonymously complete feasibility and acceptability measures, and the recruitment and attrition rate were examined. Semi-structured interviews with eight participants were conducted by the first author, after the group ended, to explore the immediate experience of the group and reasons for attrition. Interview transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). In an attempt to approach the data without pre-existing assumptions, ideas and concepts, the researcher bracketed her prior brief experience of working in an inpatient mental health service through research supervision and utilising a reflective journal. The codes and themes were determined by the data in line with an inductive approach, however the data were analysed through the researcher’s lens, and as such has inevitably elements of both inductive and deductive approach to thematic analysis.

Findings and discussion

Quantitative data

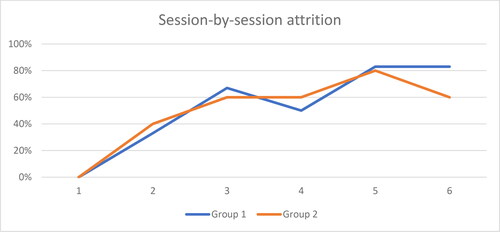

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Both recruitment and attrition rates were high, as shown in .

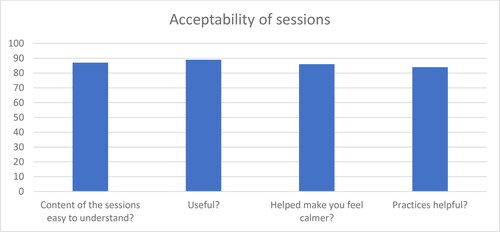

Data gathered from feedback forms suggests that the sessions were overall acceptable and did not cause people to feel any distress that would cause the drop out. Mean ratings of acceptability measures are shown in . Qualitative data analysis explores factors related to group dropout.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data were analysed in six stages in line with thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013). With regards to participants’ experience of the group, what participants appreciated and has worked well according to them, was: - session time during shift; - location outside the ward but in the same hospital; - attendance protected, supported and encouraged.

Due to the high attrition in the study, the focus of this paper is an exploration of themes that were identified in relation to reasons for drop out. One overarching theme was identified: “The system is the problem,” with five themes consistently identified across data, named using the words of the participants (1) The nature of the ward; (2) Slowing down is not allowed; (3) It is not in our nature; (4) Guilt & threat; (5) We are not important.

The quote in this paper’s title was extracted from an interview transcript with one of the study participants and is used in the title because it encapsulates the narrative of the research findings. The participant referred to “compassion” towards staff as something “forgotten about” in their workplace, due to reasons captured within the themes described below.

Overarching theme: “The system is the problem”

All participants discussed the culture of the ward environments they work in. Many talked about the specificity of working in an acute inpatient service, drawing a picture of a very challenging and exceptionally busy environment, with risk management and safety frequently brought up. This theme captured a culture of the workplace the participants were part of, how they related to one another and themselves during a shift; how they perceived themselves and those in managerial roles; and how they perceived their own value to be in their workplace.

Theme 1: “Sometimes things happen overnight”—The nature of the ward

Unpredictability and a sense of threat stress were consistently identified across data, cited to be due to changing shifts, low staffing numbers, patients’ acuity, incidents and safety. This painted a picture of an unpredictable and threatening care environment where “everyone is running around, there is chaos restraints going on […] you have to react in a busy setting when everything is kicking off”, where decisions are made in response to “the immediate needs” of the ward. The ward is seen as chaotic, a roller-coaster where “there are days when it’s quiet and you have really lovely days, and there are other days where you could pull your hair out” making it impossible to release staff as other duties take precedence in the short-term, in a reactive system:

It’s the acuity, if you got a patient who is on the ward, who is at risk of self-harm, suicide […] they’re more likely to hurt themselves in the immediate time frame than I am to suffer from staff burnout.

Many participants reported “time pressures” and felt they had “no time to stop” and reflect on your own; there was no time for staff to get together to support each other informally, let alone attend a more formal group:

It’s hard to be compassionate towards yourself and your colleagues when you just don’t have the time simply it is really important to have that bit of time […] you just like a machine “go on go on and go on.”

Theme 2: “Just letting staff know that actually it is ok to do”—It’s not allowed to slow down

All participants shared that they felt their managers or colleagues did not want them to leave the ward to attend. Sessions were also not accounted for on the shift timetable or the shifts changed on short notice, in spite of prior agreement with the ward manager about protecting staff’s attendance:

[…] with things being on a rota, it’s like mandatory—you have to go […] if I had known that I had the choice to go and it was on my rota, I still would have turned up, it’s just it wasn’t even down.

The three participants who completed the group reported that they were able to do that thanks to the encouragement from their ward manager or a colleague, or because of having more autonomy in their job. Many participants reported a lack of support or encouragement from management about attendance:

I think that’s the main barrier, the staffing levels and managers actually allowing it […] well, it’s not been said straight but that’s the message that comes from the conversations so that would have to change but that would have to come from the managers’ attitude, changing the attitude.

Many participants talked about managers not releasing staff to sessions due to their anxiety about incidents and the accountability for their decision to release staff. The threat in the system was perceived to be due to “unsafe staff numbers,” which meant there was pressure to maintain “safe” numbers on the ward, even though “numbers” could in theory be provided in a case of an emergency:

You know you’ve still got those numbers if it’s absolute emergency but I think people panic when we drop below our minimum numbers if something happens which it shouldn’t be like that because the senior management could all come down, they could come and help.

Some participants commented on the discrepancy between how they are expected to treat patients and how they felt to be treated by their leaders and by one another. If they struggled, they felt they were “expected [to] just get on with it” and that it was “very bizarre because it’s not what we say to our patients but yet we say it to staff.” This participant shared that they felt that mental health services should be “a role model for the whole of NHS” with regard to how its’ staff are treated and mental health seen – in compassionate and non-judgemental way. This participant reported the reality to be far from that.

Some participants talked about the felt pressure to stay on the ward from their own colleagues also:

[…] sometimes there’s a lot of pressure to… I think certain staff like to come in and see big round tables doing things […] I think there’s a lot of pressure to seem busy and be busy.

Many felt that it is was possible to make time for these sessions, in spite of the ward often being very busy indeed. However, a culture of “doing” and of managing (busy) impressions when it was not busy, was also captured. A culture where slowing down and “sitting down with a cup of tea with a patient”, where taking your time to engage with own suffering and the suffering of others, may have been experienced as incongruent and not embedded in a fast-paced ward environment, driven by targets and box-ticking.

Theme 3: “We look after everyone else but not ourselves”—it’s not in our nature

The majority of participants reported not habitually thinking about their own needs and prioritising them over the needs of others’ because they are “so used to putting other people first and thinking about other people, it’s alien to think about what’s best for yourself”. This theme relates to an identified block to the flow of compassion more generally. However, it was reasonable to interpret it as a barrier to attending sessions also.

Many participants reported prioritising the patients’ needs and their safety over anything else. “Put patients first” is one of the values of the organisation the participants work in, which may have become or has been an internalised belief of theirs too, to “always put the patients first, no matter what. Even if it is at the end of the day and you’re exhausted”. Some participants felt they had no other choice than to sacrifice their own well-being for the service:

[…] we give up a lot of our own wellness and our own well-being and put ourselves second so that we can look after other people. It’s just represents exactly what goes on every day.

The last two quotes are depictions of extreme self-sacrifice, where the carer helps until they can no longer do their work. Many participants identified this discrepancy between what they “preach” to patients about self-care, prioritising their own needs and self-kindness, but not practicing this themselves:

I guess I’m in a position a lot of the time where I might be working with people and talking about, you know, being more kind or being more compassionate towards yourself and I guess I don’t often practice that personally.

This discrepancy was initially a motivation to attend, and at the same time may have been a block to attending. Attending sessions where the focus is on staff well-being may be incongruent with the beliefs and behaviours of the helping professionals perhaps leading to an experience of a cognitive dissonance, because after all “we’re here to look after patients”.

Theme 4: “You feel bad if you stop”—Guilt and threat

All participants shared how leaving the ward to attend sessions as well as attempting to apply self-compassion during work prompted difficult emotions, such as guilt because “especially here on this ward you feel bad if you stop”. The sessions model and encourage a slower pace and cultivating “being with,” engaging with own or others’ feelings, in particular engagement with suffering, rather than avoidance of it. This seemed to be in contrast with the pace of the ward as described previously under another theme. However, individual staff members who form a part of the ward may also experience pressure coming from their own sense of guilt, if they were to attend the group. This theme is closely associated with the other described earlier. One participant talked about how coming to sessions meant:

[…] no activities happening on the ward now and there’s pressure from the patients. I went to see them this morning I said I won’t be there until twelve and they were like “oooh.”

In spite of it, this participant recognised the importance of the supportive role these sessions play, and had enough autonomy to allow him to attend. Another two participants who were able to attend most sessions thanks to their supervisor’s and colleague’s support and encouragement, also talked about their experience of guilt seeing other colleagues pulled out of the group:

You kind of feel like other people are having to go and they don’t have lots of time to be able to stay and take part in the group, I’m thinking “maybe I should you know join in and help.”

One participant who attended only one session, described difficulty “justifying” attendance to her manager, or perhaps to themselves because “it’s different, you are taking your time to do something that’s for you rather than for the service if that makes sense”. The group was seen as something separate to work and many participants talked about feared consequences, such as accountability because “if they [colleagues] don’t cope it will be sort of my fault for not being there”, and:

If I was to contest “oh no sorry I need to do this because obviously my well-being comes first” I’d get into trouble for that because you’re doing your job and when it all comes down to doing your job properly then it’s hard.

This participant described earlier that their decision not to attend was collaborative with their manager due to workload. Here they implied they felt unable to disagree, that they felt it would cause “trouble.” A minority talked about perceived “expectations” to make the “right choices,” in other words—to stay on the ward because “people are observing what choices you make so it makes it difficult to attend when the ward is really busy cause you feel guilty and you want your feedback to be good”. These narratives seemed to capture a environment the participants experience as threatening and possibly punitive; where it is difficult to make autonomous decisions, especially if they are perceived to be not in the best interest of the ward, in the short-term.

Theme 5: “Nobody cares about staff well-being here”—We are not important

The majority of participants shared that the difficulties experienced with attendance reflected the little value and recognition they felt they received at work for their efforts. The minority of participants shared that they may not had been explicitly told they are replaceable, but they felt they were. Many felt they were not looked after by their management and that this has implications for their work:

If we’re not looked after and don’t feel valued, it’s difficult to do your role. I find it very difficult without any support […] if I’m going through tough time, I’d like someone to actually speak to me maybe see if I was doing alright. I appreciate people are being busy and are having a lot to do but there needs to be time for this.

Many participants shared that it was possible to “find time for mandatory training, find time for meetings, endless meetings all week, therefore there is no real reason why we couldn’t find time” [for this]. A sense of powerlessness and hopelessness was captured when one student nurse said that “there’s nothing that can be done about that” because “that’s the life” on the ward:

It’s amazing how many nurses and carers I see miss non-mandatory training or groups like this, because they have to stay in the ward and that’s the way it is. I suppose that’s the life, what can you do.

Many participants wondered whether “people get pulled out because the managers think what’s that worth when you’ve got these tasks to do.” The sessions were not seen as an integral part of work, a prerequisite to do sustain yourself at work and deliver compassionate care. It may be that participants thought themselves the sessions are not important in the face of experienced pressure at work. The majority felt these sessions should be mandatory or time protected to help increase the perceived importance, and subsequent attendance because:

[…] you wouldn’t need to justify it yourself for attending it ((silence)) it forces the system to change; it forces them to see the staff as important and encourage the staff to see themselves as important.

However, a minority of participants felt that making these sessions mandatory, would run the risk of taking their autonomy away, placing the responsibility for fixing the problem that lies within the system, on the individual, and blaming the individual for not coping. As such, well-being initiatives coming from the top may be perceived by staff as a fruitless “lip-service,” if the organisation as a whole is experienced as uncompassionate towards its staff, as illustrated by the below quote:

Then, worst case scenario you burn out or make a terrible error and the organisation can say to you: “well, we did tell ya—self-care,” like in moving and handling, “you’ve signed it now, so if you do your back in, it’s your fault, we’ve trained ya.” Terrible.

The participants shared how they could not or would not attend sessions due to many systemic barriers. Their narrative also portrayed an uncompassionate environment where developing and maintaining compassion for oneself and others may be a difficult endeavour if the rest of the organisation is not involved.

Most of the barriers to attendance were organisational and were consistent with other studies of group-based interventions in acute inpatient mental health settings or overall NHS (Heneghan et al., Citation2014; Heriot-Maitland et al., Citation2014). They also highlighted the perceived lack of management support, lack of protected time and the unpredictable nature of the ward environment. This study suggests additional difficulties that threatened group attendance, namely difficulties leaving the ward due to the ward culture, where focus on “safe numbers” and tasks, takes precedence over taking the time to come together as a team to reflect, learn and support one other. The data also highlighted participants’ doubt in the ability to maintain engagement with practices learned in the group or to maintain the reported benefits from the group due to the short duration of the group, limited number of participants and the overall culture of the system within which they work. Furthermore, the difficulties with getting to sessions, either own or observed in others, led to many difficult thoughts and feelings experienced by the participants perpetuating the sense of threat, guilt, unimportance and hopelessness.

Implications for clinical practice

It is suggested that the pressure on mental health services will continue to grow (Johnson et al., Citation2018; The King’s Fund, Citation2020), in particular following the Covid-19 pandemic (Durcan et al., Citation2020). Crawford et al. (Citation2013) suggested that cultures of threat may inhibit the development of compassionate mentalities among helpers (Crawford et al., Citation2013). It seems pivotal that leaders pay careful attention to staff needs, and mental health staff receiving the much needed support never seemed more pressing. However, at the time of writing this paper the government’s funding plans for mental health services and staff support services remain uncertain.

This study identified mental health staff’s self-sacrificing beliefs and guilt prompted by attending group sessions, as well as when engaging in self-caring and self-compassionate behaviours. Self-sacrifice may be associated with stress and burnout when it is at the expense of own health, and is particularly noted in the nursing profession (Sahoo et al., Citation2012; Wabnitz, Citation2018). This may have significant implications for the well-being, absenteeism and retention level of the local health board. Compassion-focused staff support sessions could potentially be a promising approach for staff in inpatient services, for example to help staff develop an awareness of this and healthy balance between self-sacrifice, compassion and self-care; help recognise and regulate emotions and distress; cultivate empathic concern and motivation to engage with and alleviate distress in self and colleagues. However, the study identified numerous organisational barriers, which may be applicable and relevant for setting up and the uptake of any future staff support sessions. This study suggested that participants viewed their organisation and managers as pressurised or uncompassionate towards them, and viewed themselves as powerless in being able to change the culture of their workplace.

Previous research has suggested that offering short-term staff support, as a “one off” intervention may not lead to a sustainable change (Kelly & Tyson, Citation2016), and may be perceived as a “tick box.” A six session compassion-focused intervention may have been difficult to attend and perceived as unlikely to be helpful in the longer-term, indeed perhaps because of that and the fact that the very nature of the sessions may be incongruent with the nature of their working environment. In this study participants advocated for either a shorter closed group which is repeated, to capture more staff, or shorter and regular open sessions. There are arguments for both types of groups. Interventions of a shorter duration might be more feasible to “complete” given the shift-pattern of work on wards, and the average attendance was three sessions in this study. However, to create a sense of safety within a group, to maintain benefits of such intervention and create a culture change, ongoing compassion-cultivating sessions embedded within the organisational systems and workplace are arguably going to be most impactful. The model of Compassion-Focused Staff Support proposed by Lucre (Citation2018) appears most feasible, whereby an all-staff well-being day and 3 days of CFT training for clinical staff is followed by ongoing compassion-focused staff support sessions.

An alternative, or offered alongside, could be offering open-ended compassion-focused sessions for both staff and patients on the ward. This could potentially help address the challenge of releasing staff when the ward is short of staff. Providing an intervention to both staff and patients, simultaneously may also have other benefits, for example: increasing a sense of “common humanity” and affiliative relating between staff and patients on the ward. Considering sessions for staff and patients together might be an endeavour worth exploring in terms of feasibility, acceptability and therapeutic impact.

This study suggests that a group for mental health staff is unlikely to be a feasible offer without the support of leadership and management. Numerous meetings with senior management took place prior to the groups starting, and their approval had been granted. However, this appears to not have been communicated to staff effectively. Attendance was not protected on the shift timetable or shifts changed on short notice. This meant staff perceived their leaders not to be in support of these sessions. Only a minority of the study participants considered the pressure their leaders are under themselves. Compassionate approaches are unlikely to be successful in changing organisational culture if they are only to take place with a fraction of the organisation and not the whole. Consideration need to be given to the threats and demands all NHS employees face at all levels, from their leaders to domestic staff.

Limitations and future directions

Given the limited time during which this research project was undertaken, and due to the nature of the setting known for its challenges with recruitment to groups and staff training, only two groups were facilitated with only a small number of participants. The sample represented a variety of salary bands and roles however the majority of participants were White British females and the participants worked on two NHS acute inpatient wards in one health board. It is not possible to assume that findings from this study would apply to other inpatient mental health services. Replicating this study in other services and with a larger sample would be required.

When planning future feasibility studies, piloting groups or simply planning to offer compassion-focused staff support groups within acute inpatient services, a key recommendation is to ensure not only prior organisational buy-in and support at multiple leadership and management levels, but also ongoing support for the group clearly communicated to staff through encouragement and through contingency planning to enable attendance.

The findings from this research could inform further research into compassion-focused staff support and compassionate leadership mental health care. If groups like this were to be offered to staff in the future, a quantitative study with a larger sample, a control group, short- and longer-term outcome measures, would enable more robust statistical analyses to ascertain whether the reported positive changes are significant and which aspects of the group are most helpful. Future research could also explore short-term and longer-term organisational benefits of compassion-focused staff support sessions, for example its’ impact on staff sickness, and turnover, on the culture of the ward and on the experiences of service users receiving care within the service.

Conclusion

This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of a compassion-focused group for mental health inpatient staff. High recruitment rate and positive feedback from participants suggest that compassion-focused groups for inpatient mental health staff have the potential to be an acceptable and promising approach warranting further exploration and research in inpatient mental health settings. However, the high attrition and qualitative data revealed numerous barriers to subsequent attendance. Within the current design, i.e., six weekly sessions, and without a robust support of the organisation’s and service leaders, it may not be a feasible intervention to offer. Numerous barriers to attendance were identified and future adaptions of the group could potentially involve increasing the buy-in from managers into the short- and long-term benefits of such sessions and of cultivating compassionate practices in the day-to-day running of the service. It is suggested that an approach that is embedded within the organisation, i.e., regular, repeated or open-ended sessions would be more feasible and acceptable Staff support sessions should be an integral part of the organisation, the same way other process and outcomes meetings are rather than a “tick-box.” Leaders and managers need to communicate their support and commitment for such sessions verbally and through offering practical solutions to staff to enable their attendance. An important finding and implication from this study is that staff may find it difficult to relate to themselves, their colleagues and patients in a compassionate way, if they experience their leaders as not acting in such way towards them.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bazarko, D., Cate, R. A., Azocar, F., & Kreitzer, M. J. (2013). The impact of an innovative mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the health and well-being of nurses employed in a corporate setting. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 28(2), 107–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2013.779518

- Beaumont, E., Durkin, M., Hollins Martin, C. J., & Carson, J. (2016). Measuring relationships between self-compassion, compassion fatigue, burnout and well-being in student counsellors and student cognitive behavioural psychotherapists: A quantitative survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12054

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212445599

- Cetrano, G., Tedeschi, F., Rabbi, L., Gosett, G., Lora, A., Lamonaca, D., Manthorpe, J., & Amaddeo, F. (2017). How are compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction affected by quality of working life? Findings from a survey of mental health staff in Italy. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 755. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2726-x

- Cole-King, A., & Gilbert, P. (2011). Compassionate care: The theory and the reality. Journal of Holistic Healthcare, 8(3), 29–36. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285810818_Compassionate_care_the_theory_and_reality

- Cramer, H., Kemper, K., Mo, X., & Khayat, R. (2015). Are mindfulness and self-compassion associated with sleep and resilience in health professionals? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(8), 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0281

- Crawford, P., & Brown, B. (2011). Fast healthcare: Brief communication, traps and opportunities. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.016

- Crawford, P., Gilbert, P., Gilbert, J., Gale, C., & Harvey, K. (2013). The language of compassion in acute mental health care. Qualitative Health Research, 20(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313482190

- Department of Health. (2012). Transforming care: A national response to Winterbourne View Hospital. Department of Health.

- Dowling, T. (2018). Compassion does not fatigue!. The Canadian Veterinary Journal = La Revue Veterinaire Canadienne, 59(7), 749–750.

- Durcan, G., O’Shea, N., & Allwood, L. (2020). Covid-19 and the nation’s mental health. Forecasting needs and risks in the UK: May 2020. Centre for Mental Health. https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/CentreforMentalHealth_COVID_MH_Forecasting_May20.pdf

- Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

- Ewbank, L., Thompson, J., McKenna, H., & Anandaciva, S. (2020). NHS hospital bed numbers: Past, present, future. The King’s Fund.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to the challenge of life. Constable & Robinson.

- Hall, L. H., Johnson, J., Watt, I., Tsipa, A., & O’Connor, D. B. (2016). Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PLoS One, 11(7), e0159015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015

- Health Service Ombudsman. (2011). Care and compassion? Report of the Health Service Ombudsman on ten investigations into NHS care of older people. https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-10/Care%20and%20Compassion.pdf

- Heneghan, C., Wright, J., & Watson, G. (2014). Clinical psychologists’ experiences of reflective staff groups in inpatient psychiatric settings: A mixed methods study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(4), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1834

- Henshall, L. E., Alexander, T., Molyneux, P., Gardiner, E., & McLellan, A. (2018). The relationship between perceived organisational threat and compassion for others: Implications for the NHS. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(2), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2157

- Heriot-Maitland, C., Vidal, J. B., Ball, S., & Irons, C. (2014). A compassionate-focused therapy group approach for acute inpatients: Feasibility, initial pilot outcome data, and recommendations. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12040

- Itzhaki, M., Bluvstein, I., Peles Bortz, A., Kostistky, H., Bar Noy, D., Filshtinsky, V., & Theilla, M. (2018). Mental health nurse’s exposure to workplace violence leads to job stress, which leads to reduced professional quality of life. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(9), 59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00059

- Johnson, J., Louch, G., Dunning, A., Johnson, O., Grange, A., Reynolds, C., Hall, L., & O’Hara, J. (2017). Burnout mediates the association between depression and patient safety perceptions: A cross-sectional study in hospital nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1667–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13251

- Johnson, P., Kelly, E., Lee, T., Stoye, G., Zaranko, B., Charlesworth, A., Firth, Z., Gerlshlick, B., Watt, T. (2018). Securing the future: Funding health and social care to the 2030s. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/12994

- Kelly, M., & Tyson, M. (2016). Can mindfulness be an effective tool in reducing stress and burnout, while enhancing self-compassion and empathy in nursing? Mental Health Nursing, 36(6), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2014.913876

- Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927–945. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002141

- Lucre, K. (2018). Compassion focused staff support—Cultivating compassion in perinatal services. Conference paper. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328191946_Compassion_Focused_-Staff_Support_-_Cultivating_Compassion_in_Perinatal_Services

- Maben, J., Taylor, C., Dawson, J., Leamy, M., McCarthy, I., Reynolds, E., Ross, S., Shuldham, C., Bennett, L., & Foot, C. (2018). A realist informed mixed-methods evaluation of Schwartz Center Rounds® in England. Health Services and Delivery Research, 6(37), 1–260. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr06370

- McNally, D. (2019). Special measures, burnout and occupational stress in National Health Service staff: Experiences, interpretations and evidence-based interventions [Doctoral thesis, Bangor University, School of Psychology, Bangor, North Wales]. https://research.bangor.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/special-measures-burnout-and-occupational-stress-in-national-health-service-staff-experiences-interpretations-and-evidencebased-interventions(13dcbdca-dde3-420c-a7b6-732a1a9f1d7a).html?

- Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive summary. http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/sites/default/files/report/Executive%20summary.pdf

- Mountford, J., & Powis, S. (2017). Compassion: A leadership imperative for health systems. BMJ Leader, 2(1), 6–7.

- NHS Digital. (2021a). Mental Health Services Monthly Statistics. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from Mental Health Services Monthly Statistics—NHS Digital.

- NHS Digital. (2021b). NHS sickness absence rates NHS sickness absence rates January to March 2021, and annual summary 2009 to 2021, provisional statistic. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-sickness-absence-rates/march-2021-annual-summary-2009-to-2020

- Pedersen, K. Z., & Roelsgaard Obling, A. (2019). Organising through compassion: The introduction of meta-virtue management in the NHS. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(7), 1338–1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12945

- Robertson, I. T., & Cooper, C. L. (2010). Full engagement: The integration of employee engagement and psychological well-being. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31(4), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731011043348

- Royal College of Nursing. (2020). Sharp increase in nursing staff thinking of leaving the profession, reveals RCN research. Retrieved February 8, 2021, from https://www.rcn.org.uk/news-and-events/press-releases/Sharp%20increase%20in%20nursing%20staff%20thinking%20of%20leaving%20profession%20reveals%20RCN%20research

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2005). Healthcare Commission: National Audit of Violence 2003-2005. Retrieved November 1, 2019, from https://www.wales.nhs.uk/documents/FinalReport-violence.pdf

- Rossi, A., Cetrano, G., Pertile, R., Rabbi, L., Donisi, V., Grigoletti, L., Curtolo, C., Tansella, M., Thornicroft, G., & Amaddeo, F. (2012). Burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among staff in community-based mental health services. Psychiatry Research, 200(2-3), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.029

- Sahoo, S., Kumar, A., & Pradhan, N. (2012). Cognitive schemas among mental health professionals: Adaptive or maladaptive? Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 17(6), 523–526. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232252055_Cognitive_schemas_among_mental_health_professionals_Adaptive_or_maladaptive

- The King’s Fund. (2009). The point of care: Enabling compassionate care in acute hospital settings. Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/poc-enabling-compassionate-care-hospital-settings-apr09.pdf

- The King’s Fund. (2020). The NHS budget and how it has changed. Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/nhs-budget

- Vogel, S., & Flint, B. (2021). Compassionate leadership: How to support your team when fixing the problem seems impossible. Nursing Management, 28(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/nm.2021.e1967

- Wabnitz, P. (2018). Early maladaptive schemas in psychiatric nurses and other mental health professionals in Germany [Paper presentation]. Fachhochschule der Diakonie. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34799.53925