Abstract

The evidence supports use of a depression screening tool to increase screening completion in the adolescent population. Clinical guidelines include use of the PHQ-9 in the adolescent population (ages 12–18). PHQ-9 screenings are currently lacking in this primary care setting. The aim of this Quality Improvement Project was to improve depression screening in a primary care practice setting located in a rural Appalachian health system. An educational offering with pretest and posttest surveys and a perceived competency scale are utilized. Focus is added to the process and guideline used to complete depression screening. As a result of the QI Project, posttest assessment of knowledge relating to educational offering increased, and use of the screening tool increased by 12.9%. The findings support the importance of education on primary care provider practice and depression screening of adolescents.

Introduction

More than 25 million individuals are affected by Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and adolescents account for 8.3% (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Citation2022). Depression is a major risk factor for suicide which is the second leading cause of death in adolescents (Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020; American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Citation2019; Costantini et al., Citation2021). According to the World Health Organization, depression can be defined as a persistent sadness accompanied by a lack of interest or pleasure in events that were previously perceived as enjoyable or rewarding (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2023). In the United States, MDD is a health issue that affects 2.9 million adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18 annually (National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), Citation2021). Depression has been linked to alcohol and drug addiction and 70% of adolescent suicides (NAMI, Citation2021). Individuals living in rural areas experience a slightly higher yet statistically significant increased rate of MDD when compared to peers in urban areas (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Citation2020). Regrettably, it has been estimated that only 40% of adolescents diagnosed with MDD receive appropriate screening and treatment (NAMI, Citation2021) and approximately 66% of patients had contact with a primary health care provider within three months and 45% within one month of death by suicide (Luoma et al., Citation2002). Routine depression screening of all adolescents has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, Citation2019) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), (Citation2016). The early recognition and treatment of depression, as well as accompanying disease burden in adolescents, can be improved as a result of screening (Cheung et al., Citation2018; Healthy People 2020, Citation2019; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, screening of adolescents in primary care averages only 1.6%, (Healthy People 2020, Citation2019) and providers indicate a lack of clinical workflow or sequential clinical processes to accomplish depression screening as one key barrier (Godoy et al., Citation2017).

Education may improve adolescent screening within the primary care setting (Cheung et al., Citation2018; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). As a result, providers’ comprehensive assessment of depression can increase efficiency to treatment. (AAP, Citation2019; USPSTF, Citation2016; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020).

Background

In comparison to urban counterparts, adolescents who live in rural areas are two times more likely to die by suicide (Schwartz-Mette et al., Citation2022). There are 26 million residents, 30% under the age of 18, living across 13 states in the rural Appalachian region including parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, and all of West Virginia (ARC, Citation2021). Geography has been linked as a significant social environmental factor in depression among adolescents. This region’s suicide rate is 17% higher than the national rate and residents report feeling isolated and mentally depressed 14% more days than the average American (ARC, Citation2021).

The rural Appalachian region of the United States has been deeply affected by COVID-19. At one point death rates doubled those in the urban areas with one in 434 dying (Ulrich & Mueller, Citation2022). Compounded with the fact there are 35% fewer healthcare providers per 100,000 residents, COVID-19 further limited health care services within the rural Appalachian region (ARC, Citation2019). The pandemic changed daily lifestyle including stay-at-home orders, distance learning, closure of many public facilities, and further resulted in higher rates of adolescent isolation, leading to increased depression and suicide risks (Mayne et al., Citation2021). Screenings by PCPs for adolescent depression have decreased nationally by nearly two percent when compared to pre-pandemic data (Mayne et al., Citation2021). Screenings that have been completed revealed a 1.2% increase in adolescents that screened positive for depression symptoms and 1% increase in suicide risk (Mayne et al., Citation2021). These increased rates of depression and suicide risk during the pandemic emphasize the importance and need of routine adolescent depression screening in primary care (Mayne et al., Citation2021). Current evidence-based practice (EBP) strongly supports regular screening of adolescents with a depression screening tool. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends the use of an evidence-based depression screening tool annually for adolescents ages 12–18 (USPSTF, Citation2016).

In addition, the USPSTF recommend screening should be completed at all annual well exams by primary care providers with continued education on guidelines for screening and treatment of depression (AAP, Citation2019; Cheung et al., Citation2018; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a widely used tool that measures depression symptoms and is based on the nine DSM-V criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The practice of omitting appropriate routine depression screening methods is leading to preventable poor health outcomes in the rural adolescent population. Evidence-based recommendations and guidelines are in place to assist PCPs in early screening, diagnosis, and treatment of adolescent depression in a timely manner.

Problem description

Even though regular adolescent depression screening is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, Citation2019) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, Citation2016), within the primary care office setting, there was no standard process for depression screening of adolescents during preventative visits. According to practice providers, practice manager, and service line director, the current practices regarding adolescent depression screening included informal screening by providers utilizing various tools or simple questions (personal communication, 2021). Even though the PHQ-9 is used in this office setting, it is fragmented from intermittent to assess depression symptoms, or not at all.

Depression screenings that occurred were prompted by patients verbalizing symptoms of depression or depressed mood. Recommended routine adolescent depression screening at all annual well-visits was not occurring. Providers verbalized a lack of commitment to screening due to scarce mental health referral sources, process inefficiencies, and the traditional “way of doing things.” However, given the rise in adolescent depression particularly in the Appalachian region and the associated pandemic, improving screening is of the upmost importance. This gap in care offers an opportunity for an evidence-based quality improvement initiative to improve patient care.

To fill this gap, a quality improvement initiative was introduced to increase adolescent depression screening within a primary care setting. The purpose was to establish routine evidence-based depression screening by healthcare providers for all adolescents through use of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The project implemented a standardized approach using the PHQ-9 to screen adolescents for depression in a primary care setting. A standard approach to screening will enable a more efficient and comprehensive assessment of depression and increased efficiency to treatment (AAP, Citation2019; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020).

The evidence supports adolescent depression screening to ensure early identification and management of depression, resulting in decreased morbidity and mortality (Beck et al., Citation2022; Bose et al., Citation2021; Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020; Davis et al., Citation2022). The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends using an evidence-based depression screening tool annually for adolescents ages 12–18 (USPSTF, Citation2016). The recommendation is this screening should be completed at all annual well exams by primary care providers. Additionally, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends screening and has developed educational materials and guidelines for screening and treatment of depression (AAP, Citation2019; Beharry, Citation2022; Cheung et al., Citation2018; Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020; Stafford et al., Citation2020). Per Healthy People 2020, baseline data indicates that 1.6% of adolescent PCP visits during 2010–2012 included depression screening. The objective was set to increase adolescent depression screening at PCP visits 10% by 2020 (Healthy People 2020, Citation2019).

Adolescent depression screening has decreased disease burden, improved patient outcomes, reduced morbidity and mortality, as well as become an area to address disparities in healthcare. However, although the evidence supports the use of adolescent depression screening, rates remain relevantly low (Bose et al., Citation2021; Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020; Stafford et al., Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, while overall depression screenings decreased (2%), there was an increase in the percentage of positive screenings/potential depression diagnosis (8.5% to 27.8%) and suspected suicide attempts (22.3% to 39.1%) when compared to prepandemic data (Blackstone et al., Citation2022; Durante & Lau, Citation2022; Mayne et al., Citation2021). These increased rates of depression and suicide risk during the pandemic further emphasize the importance of routine adolescent depression screening in primary care (Beharry, Citation2022; Durante & Lau, Citation2022; Mayne et al., Citation2021). Recommendations and guidelines are in place to assist PCPs in early screening, diagnosis, and treatment of adolescent depression.

Education

Although depression screening guidelines exist, PCPs resistance to screening and treatment of MDD in adolescents is due to the lack of knowledge, comfort, and confidence in discussing, diagnosing, and treating mental health issues (Cheung et al., Citation2018; Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020; Stafford et al., Citation2020). Primary care providers are usually the first point of contact for adolescents and have the opportunity to evaluate and treat mental health disorders in a timely manner reducing poor outcomes (Baum et al., Citation2020; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). Educational opportunities leading to increased knowledge empower PCPs to follow expert screening guidelines set by the AAP (Citation2019), Healthy People 2020 (Citation2019), and the USPSTF (Citation2016). Educational interventions and programs related to adolescent depression screening have demonstrated an increase in adolescent screening (Baum et al., Citation2020; Cheung et al., Citation2018; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). As a result, appropriate screening has resulted in increased depression diagnoses and treatment in the primary care setting (Baum et al., Citation2020; Blackstone et al., Citation2022). Adolescents should be cared for by their PCP, receiving adequate treatment and therapy, and will be less likely to present in crisis. Providers are often lacking confidence and evidence-based knowledge on best practice for depression screening in adolescents. The current practice omitting appropriate screening methods was leading to preventable poor health outcomes in the adolescent population.

Overall aim and supporting objectives

The overall project goal or desired outcome for this project is that every patient, age 12–18 years, are screened for depression during well visits in a pediatric primary care office setting using the PHQ-9 depression screening tool. Toward that goal this QI project aimed to improve depression screening using the PHQ-9 tool by PCPs during adolescent well visits over 6 wk. The supporting objectives with specific deliverables are as follows: evaluating the effectiveness of education on the use of an evidence-based depression screening tool with a goal of PCPs receiving a post-test mean score of at least 80%; increasing the use of the PHQ-9 assessment tool by 10% at annual primary care well-visits in adolescents, ages 12–18, in the pediatric primary care office setting; and increasing pediatric primary care providers’ competency in adolescent depression screening as evidenced by an increase on the Perceived Confidence Scale (PCS) rating tool.

Theoretical framework

Project interventions were led by Knowle’s Adult Learning Theory to create an educational offering appropriate and relevant to the expert pediatric provider (Knowles et al., Citation2005). While practice change was led by Lewin’s Change Model (Mitchell, Citation2013).

Adult learning theory

The Adult Learning Theory guided provider education. Awareness of the unique needs of the adult learner was essential to meeting learning needs of this population (Knowles et al., Citation2005). Knowledge of the principles of andragogy led to the educational development for this project. The adult learner arrives with a wealth of life experience and previous knowledge which dictates the learning experience be efficient with value and relevance to the learner (Knowles et al., Citation2005). The PCPs in this office setting have many years of combined medical experience and possess expert knowledge of the adolescent patient population. The concept that mental health issues have evolved, possibly increased, and are more openly discussed in society adds pressure to the PCP to address the shifting paradigm of care for the adolescent patient (AAP, Citation2019). Shifts due to COVID-19 are essential to the conversation (Mayne et al., Citation2021). There exists a gap in care and the PCP was in a unique position to use education to impact change.

Lewin’s change model

Lewin’s Change Model was used to guide necessary practice changes to improve patient outcomes in adolescent patients in primary care settings of the Health System. This change model is straightforward with three identified stages which must be completed before change becomes permanent (Mitchell, Citation2013). Lewin’s Change Model holds value as it is sequential, simplistic, and effective. Lewin’s key concepts can be summarized in the following way:

Unfreezing (when change is needed)

Moving (when change is initiated)

Refreezing (when equilibrium is established)

In this project, change is occurring due to current practice not meeting demands of the patient population.

The change model was applied by addressing this issue in three steps: identifying the need for increased screening, providing education for providers, and implementing increased screening. Initially, the project required analysis of current policies related to adolescent depression screening, provider preferences, screening procedures, and practice culture relating to mental health (unfreezing). The unfreezing stage started with seeking information and speaking with various professionals within the Health System to identify current practice, stakeholders, and needed changes. The “unfreezing” included determination of ways to improve this system. The initial analysis, meetings with stakeholders, and surrounding conversations began in Fall 2018.

The Moving Stage incorporated education of providers on best practice initiatives, symptoms of major depressive disorder in the adolescent, benefits of screening this population, screening recommendations, and evaluating PCP perceived competence. The PHQ-9 was being used in the office setting sporadically. The Health System adding the PHQ-9 Smart Form into the EHR was a solid beginning to streamlining the process. However, the cumbersome and laborious input of data by the office staff continued.

Finally, the change model guides practice into a “new way of doing things” or the refreezing stage. During refreezing, the new way of doing things becomes a routine; patient completed the PHQ-9 and it was uploaded in to the EHR by the staff for access by the healthcare provider and, ideally, increased universal screenings utilized with adolescent patients annually. At this point, the cycle of unfreezing, moving, and refreezing continues.

Methods

Design

This evidence-based quality improvement project utilized a non-experimental pretest/posttest design surrounding an educational intervention. Content for the educational intervention centered around the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-V diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and use of Spitzer’s Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., Citation1999). The evidence-supported content of the pretest and posttest was used to evaluate effect of educational offering on PCP knowledge (AAP, Citation2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Citation2019; NAMI, Citation2021).

Setting and participants

The setting for this quality improvement project included four pediatric primary care offices in a medium-sized regional health system in rural, southern Ohio. The participants are nine PCPs treating adolescent patients, ages 12–18. The practice settings for this project were four rural pediatric primary care offices within a regional Health System. The pediatric primary care offices included one Pediatric Nurse Practitioner (PNP) and eight Pediatricians. The physicians consisted of three Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) and five Doctors of Allopathic Medicine (MD). All primary care providers (PCP) are board certified. All providers (n = 9) voluntarily participated in the education session and completed the questionnaires. There was a total of approximately n = 505 patient visits over this project period.

The involvement of the provider in overall health and wellness of this population is essential to the project. Moreover, the health and wellness of the pediatric population impacts the community. This community sits on the geographic and cultural edge of Appalachia. The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC, Citation2021) and the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps (County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, Citation2021) report this Ohio county finds 23% of children living in poverty with 47% of children being raised by grandparents or extended family. Sixteen percent of the population has a bachelor’s degree or higher. The recorded suicide rate is 15.4/100,000 compared to 13.5/100,000 for the state of Ohio (ARC, Citation2021; Mayne et al., Citation2021). The addition of the ever-changing dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting increased stress for the adolescent are added factors leading to increased MDD diagnoses in this population (Mayne et al., Citation2021). Moreover, adolescents living in rural communities have low rates of help-seeking behaviors relating to mental illness compared to their urban counterparts (Thompson et al., Citation2018). Individuals in rural Appalachian communities are not likely to reach out for help or to inform PCPs that they need help or are experiencing symptoms of depression or thoughts of suicide (Thompson et al., Citation2018).

Procedure and tools

Providers completed the Perceived Competence Scale, pre- and post-implementation, to identify if education and use of screening tool over a 6-week period added to provider competence ratings. The assessment of the educational session via pretest and posttest was intended to assess growth in learning relating specifically to provided education.

Intervention – educational offering

The evidence supports a lack of PCP confidence and comfort with discussions and diagnoses related to mental health. Education and increased knowledge introduce opportunities for PCPs to know and follow expert guidelines regarding screening set by the AAP (Citation2019), Healthy People 2020 (Citation2019), and the USPSTF (Citation2016). Additionally, the concept of provider comfort and confidence is discussed in the literature. Current practice omitting appropriate screening methods is leading to preventable poor health outcomes in the adolescent population.

Education was a key project component of the quality improvement project. An initial educational offering at each of the four practice locations assisted providers in increasing knowledge of the risks of MDD, providing evidence-based recommendations relating to depression screening, and the benefits to stakeholders of universal adolescent depression screening in the PCP setting. Providers were invited to a one-hour, in-person educational opportunity via email. Providers completed a pretest, followed by a PowerPoint Presentation and discussion, with learning assessed by a posttest. The educational sessions were guided by the project leader, a board-certified psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner with over 10 years in education and practice. The educational session took place over 1 week in the PCP office setting consisting of an interactive PowerPoint presentation on adolescent depression, depression screening, and recommendations for screening.

Measures

Perceived Competency Scale

Another measure of QI project implementation was primary care providers’ perceived competence in using a recommended evidence-based adolescent (ages 12–18) depression screening; the PHQ-9. Providers’ competence was rated prior to educational session and at project completion using the Perceived Competency Scale (PCS). The scale assessed the PCP’s perception of their ability to perform adolescent depression screenings based on intrinsic motivation (Williams et al., Citation1998; Spitzer et al., Citation1999). This scale is a short 4-item questionnaire used to determine participants’ thoughts on competency. The items focus on specific domains of behaviors and is adaptable to evaluate a wide range of behaviors including providers’ competence in depression screening. The PCS’s alpha measure of internal consistency is consistently reported above 0.80 in separate studies (Williams et al., Citation1998; Spitzer et al., Citation1999).

Pretest and posttest

This evidence-based project used a pretest and posttest assessment to evaluate provider knowledge surrounding educational offerings. The pretest and posttest were based on evidence and evaluated by experts in the field. The questions included:

Current use of adolescent depression screening.

Depression treatment options.

Familiarity with depression screen tools.

Comfort level with depression screening and assessment in adolescents.

The items were scored on a Likert Scale with answers ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Questions 6–11 were short answer questions and included average onset and age of mental depressive disorder, percent of adolescents that attempt suicide, and most importantly, “What percent of patients see their primary care provider within a month of death by suicide? (45%).” Numeric results were applied to each type of question with scores compiled as a group average. An increase of learning would be evidenced by an increased posttest average when compared to pretest average. An overall mean score of 80% on the posttest was set as a project objective.

The tests were identified by random numbers to protect the anonymity of the providers but provide the investigator a way to compare pre- and post-tests. A hospital administrator, a DNP-educated nurse, assisted in collection and identification of specific number to PCP matching while keeping the identify of each de-identified from the lead investigator. PCS and pretests were completed by providers and placed in envelopes available for this purpose. The envelope was kept sealed and locked by the assisting DNP nurse to maintain anonymity of each participant. Following PowerPoint presentation, providers completed a posttest. The posttest was also placed in an envelope, sealed, and locked until needed for data collection. All data will remain de-identified and secured for 3 years. Post-implementation PCS was collected the week following project completion.

Depression screening: PHQ-9

Multiple depression screening tools are available to the provider. The Patient Health Questionnaire − 9 (PHQ-9) and the PHQ-9: Adapted for the Teen have vast supporting evidence (O’Byrne & Jacob, Citation2018; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). However, the Health System had already selected the PHQ-9 for PCP use in this practice setting and preferred to continue use. The PHQ-9 is a validated and widely used depression screening tool (Blackstone et al., Citation2022; Chowdhury & Champion, Citation2020). The tool is a self-administered screening completed by patients. The estimated completion time is two minutes. The PHQ-9 measures depression symptoms and is based on the nine DSM-V criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The nine criteria include anhedonia, feeling depressed (irritability is common in the adolescent), change in sleep, change in appetite, feeling tired/lack of energy, feeling bad about self/feelings of guilt, trouble concentrating, moving/speaking slowly (or fidgeting/restless), thoughts of death/better off dead/thoughts of self-harm. Self-reported questions ask how often patients have experienced symptoms in the past 2 weeks and how difficult these symptoms make their daily life.

The items are scored on a Likert scale, results range from 0 to 3 (not at all to nearly every day). Total PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27. Total scores may be interpreted as no depression (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), or severe depression (20–27). A cut off score of 10 is suggested for possible diagnosis of MDD (Spitzer et al., Citation1999). The PHQ-9 is an easy to use, cost effective screening tool with 90% specificity and 75% sensitivity (Spitzer et al., Citation1999). The tool is used in multiple languages, across the lifespan, and in medical and academic settings. The PHQ-9 has been studied in relation to various levels of education, gender, and race/ethnicity with reliability and validity present in each demographic (Spitzer et al., Citation1999). Following a positive screening, the provider assesses the patient for MDD diagnosis and follow-up appropriately. A positive screening is not equivalent to a Major Depressive Disorder diagnosis. The expertise and knowledge of the provider determines if the patient meets MDD diagnostic criteria.

Project goal was that every patient, age 12–18 years, of participating providers was given the PHQ-9 depression screening tool to complete using pen/paper. The medical assistant then transcribed the results into a Smart Form in the Electronic Health Record (EHR). Initiated during the project, an added billable code was entered into the patient chart by the provider for a brief emotional/behavioral assessment with the PHQ-9.

Data collection

Outcome measures focus on the providers’ perceived competence in depression screening using the PHQ-9 adolescent depression screening tool, and the changes in the pre and posttests administered.

Educational offering/pretest and posttest

The results of the educational offering were measured through the pre- and post-test scores. This data is representative of participants’ scores on a 5-point Likert scale pretest and posttest administered surrounding education. Responses were obtained, followed by analysis of the survey summary comparing pre and post education for total means scores.

The educational offering included a PowerPoint slideshow with discussion points leading conversation on adolescent depression, recommended depression screenings, and evidence relating to routinely screening adolescents in the primary care setting. Pretests and posttests were collected and scored to reflect on effectiveness of educational offering. All data was de-identified. Mean and standard deviation were analyzed. The outcome measures of the educational offering included data on quantitative outcomes from each of the four practice settings. The quantitative data was a representation of participants’ scores on a pretest and posttest administered surrounding the education.

Perceived competence scale

Another implementation measure was improved primary care providers’ perceived competence in using a recommended evidence-based adolescent (ages 12–18) depression screening tool. The PSC rating scale was used to assess providers’ perceived competence before and after project implementation.

Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) de-identified data was initially collected on five pre-implementation dates over a 1-week period. The base line data collection occurred prior to the pretest during educational offering. PCS data was collected a second time during the week following implementation completion.

Use of depression screening PHQ-9

The primary outcome measure assessing use of the PHQ-9, an evidence-based depression screening tool, was the number of times a PCP entered the designated screening code in the EHR. Determining to what degree the implementation of universal use of the PHQ-9 impacts screening for depression when compared to current practice among PCPs in a primary care setting over 6 weeks was of primary interest.

An email request was submitted to the Service Line Director and Information Technology (IT) department team for retrospective and prospective data. Requested data included retrospective data over a 6-week period prior to implementation. Prospective data was requested for the 6-week period after the PHQ-9 educational intervention. All information was de-identified, filtered by age (12–18 years), and with and without CPT Code 96127. For each of the previous requests, individual PCP information was also requested, de-identified by number assignment (the same number as pre and post survey information) by Service Line Director. The requested data allowed for comparison of changes in practice for each PCP and for the practice. Additionally, the retrospective data allowed a look at pre-pandemic screening practices while prospective allowed analysis during the pandemic and implementation.

Data analysis

The latest version of SPSS, version 25.0, was used for statistical analysis. SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) is a statistics software used for statistical analysis. The data analysis plan was conducted in two phases. Education effectiveness and competence are presented using descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages. Next, paired t-tests identified if PCS differed pre and post implementation with a composite measure, as well as by individual scale items. To evaluate PHQ-9 screenings, a power analysis was done to justify the completed PHQ-9 sample size of 87 unique lives, which indicated the anticipated patient screening sample to be included over 6 weeks. PHQ-9 screenings completed = 87. A total of 432 patients were included.

Ethical considerations

Approval for project implementation was received from completion of the University Human Subject Research Determination Form and the Health System following completion of the Human Subjects Determination Review and deemed as a Quality Improvement Project. Additionally, approval was obtained from the Health System leadership and Service Line Director to complete project and collect de-identified provider data. Prior to completing the questionnaire, the project lead provided the volunteer PCPs in the general pediatric practice a written sheet and verbal guidelines detailing the quality improvement initiative, as well as how the data would be used upon completion of the project. Submission of the questionnaire indicated informed consent to participate.

Results

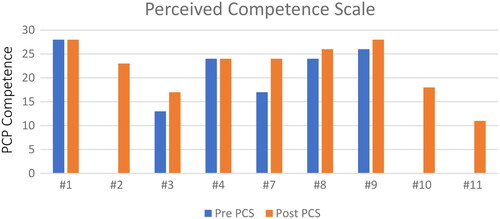

Perceived competence scale

Pre/post intervention differences in feelings of competency were examined. Perceived Competency was assessed using a survey with four Likert items ranging from 1 (“Not at all true”) to 7 (“Very true”). Items assessed:

I feel confident in my ability to manage adolescent depression screenings.

I am capable of handling my adolescent depression screening outcomes.

I am able to do my own routine adolescent depression screenings.

I feel able to meet the challenges conducting adolescent depression screenings.

The four responses were averaged to arrive at an overall competency score. Higher score indicated greater competency. The intervention involved nine providers. There were both pre- (M = 5.5, SD = 1.4) and post- (M = 6.2, SD = 0.8) competency scores for six of the providers.

The direction of change over time was consistent with the objectives of the project of PCP increase in scores. The mean of the competency scores showed an on-average increase of 0.7 units. Results of comparisons of the pre and post average competency scores indicates no difference in the pediatric primary care providers’ pre/post competency of adolescent depression screening. While an increase was demonstrated and holds clinical significance, this change is not statistically significant.

Educational offering/pretest and posttest

Results of analyses of data from an educational intervention are summarized, the objective of which was to increase provider knowledge about and screening for depression. Knowledge was assessed using the total correct on a 6-question test. Thus, the range in test scores was 0 to 6. The intervention involved nine providers. There were both pre- and post-knowledge scores for eight of the nine. The pretest (M = 5.5, SD = 1.4) and posttest (M = 4.8, SD = 1.3) educational offering scores were analyzed. The summary statistics for the dataset of paired knowledge scores indicated the mean of the pre-scores is 1.75, and the mean of the post is 4.75. The difference in means is 3.00, for the true pre/post mean difference of 2.00 to 4.00. The direction of change over time was consistent with objectives of the project. Thus, there was clinical evidence of an increase in knowledge.

Use of depression screening: PHQ-9

Pre/post differences in the frequency of PHQ-9 use and the impact of interventions was analyzed. A Pearson chi-squared test was used to assess whether the intervention influenced the rate of PHQ-9 use. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was the criterion used to determine statistical significance.

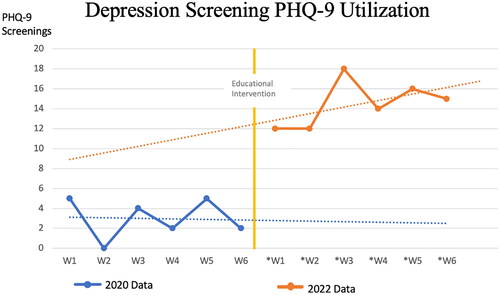

summarizes the distribution of the pre and post use of the PHQ-9. The distribution of PHQ-9 use stratified by time relative to the intervention. Also presented is the p value for a Pearson chi squared test for differences in percentages related to time.

Table 1. PHQ-9 distribution data.

The trend in observed use was consistent with project objectives of increased use of the PHQ-9. The 16.8% rate after the intervention was 12.9% greater than the 3.9% rate before the intervention. The p value for the chi squared test was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

A retrospective comparison of the current rate of screening to past performance was important to evaluate significance of a targeted educational offering on PCP practice. With the COVID-19 pandemic, national rates of adolescent depression screening decreased creating a greater disparity for this age group (Healthy People 2020, Citation2019). Data was collected in early 2020, prior to the influence of the pandemic, and in 2022, following project implementation and an educational offering with each PCP in the practice.

Individual Provider Use of PHQ-9 total patient visits were n = 505 with n = 90 PHQ-9 screenings. In this practice setting, use of PHQ-9 screening significantly rose for three PCPs. However, PCP 4 was not with the practice in 2020. In addition, PCP 9 was likely an early champion of screening and expanded on the use in 2022. Increased screening is evident, the PHQ-9 was used 16 times during the 2020 period versus 87 times during the 2022 period for a difference of n = 71. Overall, the increased use and the potential of education to create change was demonstrated through a 134% increase in depression screening from 2020 to 2022. Additionally, comparison of the current rate of screening to past performance was important to evaluate significance of a targeted educational offering on PCP practice, as seen in .

To determine whether the intervention influenced the rate of PHQ-9 use, pre and post differences were compared (). Comparison of the current rate of screening to past performance was important to evaluate significance of a targeted educational offering on PHQ-9 screening. The trend indicated 3.9% of adolescent patients were screened in 2020 and 16.8% were screened in 2022. The rate of screenings increased by 12.9% of all practice patients during the 6-week implementation compared to pre-implementation and pre-pandemic data. The objective of a 10% increased PHQ-9 use was met. The increased in PHQ-9 screenings is statistically significant.

Similar to project findings, the evidence supports education as a catalyst for change relating to depression screening and improving providers’ feelings of competence. The impact of the project on the adolescent population and the PCPs’ screening practice is clinically significant. Addressing mental health earlier will lead to efficiency in identifying, diagnosing, treating, and recovering from associated illnesses. The project findings support existing evidence that using education is a catalyst for change relating to depression screening (AAP, Citation2019; Cheung et al., Citation2018; O’Byrne & Jacob, Citation2018).

Provider’s perceived competence was evaluated prior to and following implementation. PCP data improved or remained unchanged following implementation. Three providers had incomplete data on the pre-implementation data. While a statistically significant change is not feasible on perceived competency due to the small sample size, the increase is clinically significant. The PCPs initiating use during the project, demonstrated an increase in perceived competence as did the PCPs that completed the educational offering and did not initiate use of the screening tool ().

Discussion

Educational impact on adolescent depression screening

A standard approach to screening will enable a more efficient and comprehensive assessment of depression and increased efficiency to treatment (AAP, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2022; Zuckerbrot et al., Citation2020). One objective of the QI project was to evaluate the impact of an educational offering on PCP use of the PHQ-9 and any changes in PCP perceived competence relating to the depression screening tool. Initial steps of implementation included identification of project champions and stakeholders. Finding supporters of the project was important prior to launching implementation. Educational offerings were impactful on outcomes of use. However, while the ideal state was PHQ-9 use with all adolescent patients, the reality is that 3.9% of adolescents in this practice setting were screened prior to implementation. The practice was performing above the U.S. national average of 1.6% of adolescent patients screened annually for depression by PCPs utilizing evidence-based screening tools (Healthy People 2020, Citation2019).

An early project objective was to increase overall adolescent depression screening by 10%, a goal set by Healthy People 2020. While only one-third of practice providers participated in screenings, the rate of screenings increased by 12.9% of all practice patients during the 6-week implementation compared to pre-implementation and pre-pandemic data. This increase in PHQ-9 screenings is statistically significant. To evaluate the effectiveness of education, a project objective was set that PCPs would earn a posttest mean score of at least 80%; the resulting mean score was 80%. Meeting the final project objective, PCPs’ perceived competence increased demonstrating clinical significance. Strengths of the project include the support of Health System administration, PCP project champions, and the education provided. Additionally, the topic of mental health was discussed with 9 PCPs; the stage was open, and this platform allowed for an elevated conversation on a topic of mental health and treatment.

Limitations

The findings from this quality improvement project are limited due to the small sample size of participating providers within four rural primary care settings. Another limitation is the competency scale is self-reported therefore participants may lack insight into their own situation and give answers which they consider to be the most socially acceptable. An additional limitation is the use of only one type of screening. Other types of adolescent depression screenings were not assessed by this project.

Conclusions

Nationally, adolescents are receiving substandard care relating to their mental health is disturbing and action must be taken. This is a historic change and one that health care leaders must utilize to improve systems and create new systems to better meet mental health patients where they are by increasing access and overcoming biases. Preventing the high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with mental illness is essential.

Finally, in this rural Appalachian region, the added safety of adolescent depression screening combats cultural teachings that individuals should not ask for help, should not trust health care providers, and should not talk “about certain things.” The extensive literature search and project work was useful and has implications for the children, families, and communities locally. Continued research and expansion of EBP will lead to far-reaching implications for communities, families, and children across the country and beyond. The Providers will gain competence as they are treating their patients as indicated by the evidence and knowing they are offering their best to each patient within their practice.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). (2019). American Academy of Pediatrics describes the unique needs of adolescents with new policy statement. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/news/Pages/Unique-Needs-of-the-Adolescent.aspx?_gl=1*14ygvx*_ga*MTI0MTE0NjQwNC4xNjM1NzAxNTQ5*_ga_FD9D3X

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). APA.

- Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). (2019). Getting healthcare—And getting to healthcare—In the Appalachian Region. https://healthinappalachia.org/2019/06/19/getting-healthcare-and-getting-to-healthcare-in-the-appalachian-region/

- Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). (2021). Rural Appalachia compared to the rest of rural America. https://www.arc.gov/rural-appalachia/

- Baum, R. A., Hoholik, S., Maciejewski, H., & Ramtekkar, U. (2020). Using practice facilitation to improve depression management in rural pediatric primary care practices. Pediatric Quality & Safety, 5(3), e295. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000295

- Beck, K. E., Snyder, D., Toth, C., Hostutler, C. A., Tinto, J., Letostak, T. B., Chandawarkar, A., & Kemper, A. R. (2022). Improving primary care adolescent depression screening and initial management: A quality improvement study. Pediatric Quality & Safety, 7(2), e549. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000549

- Beharry, M. (2022). Pediatric anxiety and depression in the time of COVID-19. Pediatric Annals, 51(4), e154–e160. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20220317-01

- Blackstone, S. R., Sebring, A. N., Allen, C., Tan, J. S., & Compton, R. (2022). Improving depression screening in primary care: A quality improvement initiative. Journal of Community Health, 47(3), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01068-6

- Bose, J., Zeno, R., Warren, B., Sinnott, L. T., & Fitzgerald, E. A. (2021). Implementation of universal adolescent depression screening: Quality improvement outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 35(3), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2020.08.004

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019). Health equity: Leading causes of death in males and females, United States. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/lcod/index.htm

- Cheung, A. H., Zuckerbrot, R. A., Jensen, P. S., Laraque, D., Stein, R. E., Levitt, A., Birmaher, B., Campo, J., Clarke, G., Emslie, G., Kaufman, M., Kelleher, K. J., Kutcher, S., Malus, M., Sacks, D., Waslick, B., & Sarvet, B. (2018). Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics, 141(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610024310-part05-ch18

- Chowdhury, T., & Champion, J. D. (2020). Outcomes of depression screening for adolescents accessing pediatric primary care-based services. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 52, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.02.036

- Costantini, L., Pasquarella, C., Odone, A., Colucci, M. E., Costanza, A., Serafini, G., Aguglia, A., Belvederi, M., Brakoulias, V., Amore, M., Ghaemi, S. N., & Amerio, A. (2021). Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.131

- County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. (2021). County health rankings and roadmaps: Building a culture of health county by county, Ohio. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/media/document/CHR2021_OH.pdf

- Davis, M., Jones, J. D., So, A., Benton, T. D., Boyd, R. C., Melhem, N., Ryan, N. D., Brent, D. A., & Young, J. F. (2022). Adolescent depression screening in primary care: Who is screened and who is at risk? Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.022

- Durante, J. C., & Lau, M. (2022). Adolescents, suicide, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatric Annals, 51(4), e144–e149. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20220317-02

- Godoy, L., Long, M., Marschall, D., Hodgkinson, S., Bokor, B., Rhodes, H., Crumpton, H., Weissman, M., & Beers, L. (2017). Behavioral health integration in health care settings: Lessons learned from a pediatric hospital primary care system. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 24(3-4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9509-8

- Healthy People 2020. (2019, March 17). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/mental-health-and-mental-disorders/objectives#4804

- Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Elsevier.

- Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909

- Mayne, S. L., Hannan, C., Davis, M., Young, J. F., Kelly, M. K., Powell, M., Dalembert, G., McPeak, K. E., Jenssen, B. P., & Fiks, A. G. (2021). COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics, 148(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-051507

- Mitchell, G. (2013). Selecting the best theory to implement planned change. Nursing Management, 20(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.7748/nm2013.04.20.1.32.e1013

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2021). Mental health by the numbers. https://www.nami.org/mhstats

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2022). Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression

- O’Byrne, P., & Jacob, J. D. (2018). Screening for depression: Review of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for nurse practitioners. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(7), 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000052

- Schwartz-Mette, R. A., Duell, N., Lawrence, H. R., & Balkind, E. G. (2022). COVID-10 distress impacts adolescents’ depressive symptoms, NSSI, and suicide risk in rural Northwest US. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 53, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2042697

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., & Williams, J. B. (1999). Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(18), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

- Stafford, A. M., Garbuz, T., Etter, D. J., Adams, Z. W., Hulvershorn, L. A., Downs, S. M., & Aalsma, M. C. (2020). The natural course of adolescent depression treatment in the primary care setting. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 34(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.07.002

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2020). National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). http://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2020-national-survey-drug-use

- Thompson, L. K., Sugg, M. M., & Runkle, J. R. (2018). Adolescents in crisis: A geographic exploration of help-seeking behavior using data from Crisis Text Line. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 215, 69–79. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.025

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). (2016). Evidence synthesis: Number 116: Screening for major depressive disorder among children and adolescents: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review145/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening

- Ulrich, F., Mueller, K. (2022). COVID-19 cases and deaths, metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties over time (update) Brief No. 2020-9. RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis. http://www.public-health.uiowa.edu/rupri/

- Williams, G. C., Freedman, Z. R., & Deci, E. L. (1998). Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care, 21(10), 1644–1651. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Depressive disorder (depression). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Zuckerbrot, R. A., Cheung, A., Jensen, P. S., Stein, R. K., & Laraque, D. (2020). Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics, 141(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610024310-part05-ch17