?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Developing therapeutic relationship skills as well as clinical skill confidence is critical for nursing students. While the nursing literature has examined multiple factors that influence student learning, little is known about the role of student motivation in skill development in non-traditional placement settings. Although therapeutic skills and clinical confidence are vital across a variety of contexts, here we focus on its development in mental health settings. The present study aimed to investigate whether the motivational profiles of nursing students varied with the learning associated with developing (1) a therapeutic relationship in mental health and (2) mental health clinical confidence. We examined students’ self-determined motivation and skill development within an immersive, work-integrated learning experience. Undergraduate nursing students (n = 279) engaged in five-day mental health clinical placement, “Recovery Camp,” as part of their studies. Data were collected via the Work Task Motivation Scale, Therapeutic Relationship Scale and the Mental Health Clinical Confidence Scale. Students were ranked into either high (top-third), moderate (mid-third) or low (bottom-third) motivation-level groups. These groups were compared for differences in Therapeutic Relationship and Mental Health Clinical Confidence scores. Students higher in motivation reported significantly higher therapeutic relationship skills (Positive Collaboration, p < .001; Emotional Difficulties, p < .01). Increased student motivation was also associated with greater clinical confidence compared to each lower-ranked motivation group (p ≤ .05). Our findings show that student motivation plays a meaningful role in pre-registration learning. Non-traditional learning environments may be uniquely placed to influence student motivation and enhance learning outcomes.

Introduction

There is widespread acceptance that the learning and teaching landscape is an evolving one. This evolution was occurring long before the global COVID-19 pandemic, though it has been argued that COVID-19 has accelerated change in teaching and learning practices (Nóvoa & Alvim, Citation2020). This progression is evidenced by a shift from traditionally objectivist and educator-led methods of instruction to more constructivist approaches. Such approaches are based on the philosophy that knowledge is a process of perception and active integration by the learner, rather than a “thing” to be passively discovered (Neutzling et al., Citation2019).

No matter the practice, the teacher remains pivotal, and within learning environments it is often the teacher that identifies critical moments in the teaching context that require the explicit transition of knowledge (Myhill & Warren, Citation2005). Although it may be the teacher who provides these opportunities and experience for learning, the individual student nonetheless plays a key role in their own education and development (Basri, Citation2023). In this regard, teaching and learning across all educational settings can be viewed as an interplay between student and teacher. Educators therefore are required to employ innovative approaches that ensure the needs of learners are met (Kuhlthau et al., Citation2015). As educators come to rethink their pedagogy and increasingly employ a student-centred approach (O’Connor, Citation2022), the traditional classroom has also changed as education occurs in more diverse and innovative settings (Beames et al., Citation2011).

Research has examined the role of diverse pedagogies and experiences on the support and facilitation of student learning (Kumar & Refaei, Citation2017; Paniagua & Istance, Citation2018). It is from this evidence that we gain an understanding that the student should be placed in educational experiences that provide high opportunities for learning, and in this regard, work-integrated learning (WiL) experiences are increasingly offered (Billett et al., Citation2018). Within nursing, WiL forms a major component of pre-registration education. In Australia, the setting for this study, nursing students preparing as a registered nurse have a mandatory 800 h of work-integrated learning experience in addition to 24 theoretical subjects. This compulsory clinical experience occurs in a variety of settings, including mental health, and provides opportunities for applying nursing theory alongside the development of skills and clinical confidence. Whilst there have been attempts to quantify clinical-skill confidence in general nursing settings, little attention has been given to factors affecting the development of, and confidence in, clinical skills in mental health settings. This is particularly important given that mental health nursing is not a desirable career option for most BN students (Happell et al., Citation2013), and yet all nurses, no matter where they practice, will encounter people experiencing various stressors (e.g. pre-operation anxiety; distress in the emergency department) and therefore need to be able to respond therapeutically.

A primary goal of educational research is to understand how and under what conditions students learn best (Wulf, Citation2017). Much has been written about the influence of external factors on student learning in traditional settings (e.g. policy, curriculum, environment, classroom activities, and educators, etc.), and the research scope in recent years has expanded to consider the impact of student dispositions, attitudes and motivations on the learning process (Orsini et al., Citation2015). Student learning may now be more frequently framed as a process meaningfully influenced by motivation, and alternative clinical placements such as Recovery Camp have been recommended for student training and professional development due to their non-medical setting (Mental Health Productivity Commission Inquiry Report, p. 39). Given the pressing need for all nursing students to cultivate therapeutic skills and clinical confidence, Recovery Camp provides an ideal setting for examining the influence of student motivation on professional skills and confidence when relating therapeutically to individuals living with severe and enduring mental illness. By its design, Recovery Camp provides higher ratios of student nurses-to-consumers than is typical of a traditional mental health placement; in addition, the immersive nature of the placement permits students more occasions to practice their therapeutic skills in a variety of contexts (e.g. during collaborative/recreational tasks, during meals, during “down time”), as opposed to those typical of traditional placement settings. Additionally, Recovery Camp provides a consistent educational program. This consistency allowed for a more focussed investigation of the study variables and systematically supported that inter-educator variability was not an issue.

This paper examines learning in relation to student self-determined motivation after undertaking a mental health clinical placement in a non-traditional WiL setting. Specifically, student “learning” in this environment is indexed by the development of therapeutic relationship skills as well as mental health clinical confidence. We aim to further extend the knowledge associated with student dispositions and the potential knowledge gained from their educational experiences.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine whether differences in student self-determination was associated with the level of therapeutic relationship skills and clinical confidence within a mental health clinical placement.

Research questions

Does the motivational profile of nursing student self-determination vary with the level of professional skill development associated with developing a therapeutic relationship in mental health?

Does the motivational profile of nursing student self-determination vary with the level of professional skill development associated with mental health clinical confidence?

Methods

Participants and setting

The present study involved pre-registration nursing students (N = 279) enrolled in their second-year of study at a tertiary education institution in Australia. All students undertook their mental health clinical placement as part of a five-day program called Recovery Camp (Tapsell et al., Citation2021). Recovery Camp is a WiL experience that accounts for 80 clinical placement hours. It is a non-traditional (i.e. not hospital-based) clinical placement where student nurses are immersed in a therapeutic recreation program alongside people with mental illness. It is during this immersive program that students learn from people with lived experience whilst having their learning facilitated by registered nurses who have specialist mental health nursing experience.

Institutional ethics was granted by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2019/ETH03767). Students were provided with information about the study on the final morning of Recovery Camp and invited to use their smartphones to indicate their consent electronically and complete the survey battery via the Qualtrics platform. Completion of the surveys took approximately 10 min and involved students reflecting on their 80-h placement and assessing several aspects of their skill development and clinical skill confidence. Inspection of student responses post-program revealed 279 students consented to participate in the study.

Measures

Motivation towards learning scale

Each pre-registration nursing student completed an adapted Work Task Motivation Scale (WTMS; Fernet et al. Citation2008). The WTMS asks each participant a total of 12-items which are rated using a 7-point Likert scale. A total of four subscales (intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, external regulation and amotivation) are calculated for each participant. These variables are achieved by averaging the responses of the three items housed within each subscale. The level of an individual’s self-determination is then calculated using the following: (2 × Intrinsic Motivation) + Identified Regulation—External Regulation—(2 × Amotivation). Fernet et al. (Citation2008) established the validity (Cronbach’s α > 0.70) and reliability of the WTMS for assessing educational professionals, while Cregan et al. (Citation2016) supports the use of the WTMS with nurses.

Therapeutic relationship scale

The therapeutic relationship (TR) between the nurse and consumers has long been considered a foundation of mental health nursing (Moxham et al., Citation2018) and can in fact be considered the core of practice (Dziopa & Ahern, Citation2009). The Therapeutic Relationship Scale (TRS) developed by McGuire-Snieckus et al. (Citation2006) was used to index the skill of each student nurse in developing a therapeutic relationship in the field of mental health. Using a 5-point scale, participants responded to 12-items across three distinct subscales: Positive Collaboration (reflecting rapport, mutual trust, and the general quality of the relationship between clinican and patient), Emotional Difficulties (the clinician’s assessment of any problems in the relationship, such as struggling to empathise with the patient) and Positive Clinician Input (captures behavioural aspects such as clinician supportiveness, encouragement, regard). The TRS demonstrates internal consistency (all factors exhibit Cronbach’s α > 0.65) and reliability (test-retest correlation co-efficients all significant at p < .05) across both national and international samples (McGuire-Snieckus et al. Citation2006).

Mental health clinical confidence

The Mental Health Clinical Confidence Scale (MHCCS) was developed to investigate the impact of mental health clinical placements on undergraduate nurses’ attitudes and clinical confidence. The MHCCS is a 20-item (4-point) questionnaire with a total confidence score calculated by summing all responses across the 20-items. Bell et al. (Citation1998, p. 184) established that the MHCCS exhibited “robust” psychometric properties when assessing the reliability and validity of this tool for use with nursing students.

Data analysis

All data were exported from Qualtrics into SPSS and scanned to identify any missing participant entries. This screening identified 23 incomplete surveys which were omitted from the study. Participant data (N = 256) was then condensed (using the procedures identified in the Data Collection Measures section above) into the central research variables of Self-Determined Motivation, Therapeutic Relationship (PC, ED and PCI domains) and MHCC. There were then two main stages to categorise the data for subsequent between-subject comparisons. Firstly, each participant’s self-determined motivation score was ordered from highest to lowest. Next, the participants were classified into one of three “motivation level” groups based on their score in relation to the wider dataset: high (top third of scores), middle (middle third) or low (bottom third). Descriptive and Reliability analyses for the main study variables of TR and MHCC were calculated for each motivation group. To examine the first research question, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with Tukey’s Post-Hoc test for PC, ED and PCI was performed. To examine research question two, a univariate ANOVA with a Tukey’s Post-Hoc test for MHCC was used.

Results

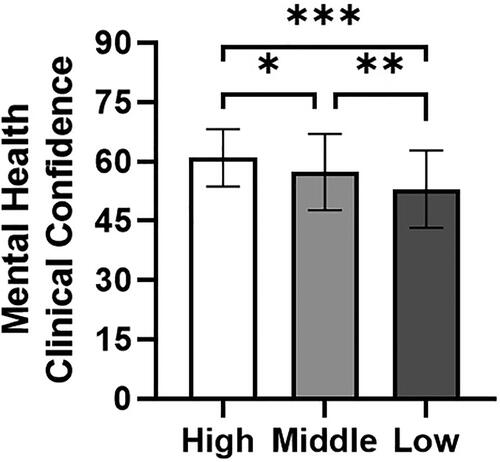

A MANOVA was used to examine the influence of student motivation on three distinct variables as measured by the therapeutic relationship scale: Positive Collaboration, Emotional Difficulties and Positive Clinician Input. The MANOVA revealed a significant main effect of motivation level, F(6, 548) = 7.12, p < .001, , such that higher motivation levels were associated with greater therapeutic relationship skills. This effect size can be considered large (Cohen, Citation1988). As can be seen in , post-hoc Tukey tests identified significantly higher levels of positive collaboration for the high- and middle- ranked motivation groups compared to the low motivation group (p < .001). There was no significant difference in positive collaboration between the high- and middle-ranked motivation groups. Post-hoc Tukey tests also revealed that participants in the high-ranked motivation group rated the consumers they interacted with as having significantly more emotional difficulties compared to the middle-ranked (p = .010) and low-ranked motivation group (p = .005). No differences were observed between groups in relation to positive clinician input.

Figure 1. Mean differences per subscale of the therapeutic relationship scale, displayed for each motivation-ranked group. Error bars indicate SE.

Note. *** = p < .001, ** = p < .01, ns = non-significant.

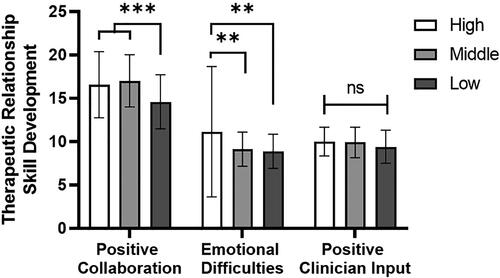

To investigate the effect of student motivation for learning on mental health clinical confidence, a univariate ANOVA was performed to compare scores on this measure between the three motivation-ranked groups. A significant main effect of motivation was observed, F(2, 278) = 18.17, p < .001, .116, with this effect size also considered large per Cohen’s conventions (1988). Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed that clinical confidence significantly decreased across groups as a function of motivation level ().

Discussion

Mental health nursing has been identified as a less-desirable career option for most BN students (Happell et al., Citation2013). Yet, all nurses, no matter where they practice, will encounter people experiencing a wide range of stressors and need to be able to relate therapeutically. In that regard, the present study sought to investigate the role of student motivation in relation to nursing students’ skill in developing therapeutic relationships, as well as students’ clinical confidence.

Within the context of an immersive 5-day mental health clinical placement, it was found that self-determined motivation level was significantly associated with students’ therapeutic skill development and clinical skill confidence. Higher motivation towards learning was meaningfully related to increased therapeutic relationship skills; specifically, students with greater self-determination reported higher positive collaboration with consumers. These nursing students also observed significantly more emotional difficulty in consumers when compared to their low-motivation student counterparts. This increased observance of emotional difficulties in the clinical population is unsurprising when we consider that higher clinician empathy is often coupled with an increased awareness of consumer challenges, whether in the therapeutic relationship or in the context of wider services. The authors of the therapeutic relationship instrument used in the present study note that “Positive Collaboration” captures the least behaviourally determined of the three sub-scales; in this regard, the factor has been described as measuring the “chemistry” between the clinician and consumer (McGuire-Snieckus et al. Citation2006). As such, these data indicate that nurses higher in delf-determined motivation evidence a greater awareness of consumer’s emotional state, perhaps linked with higher awareness of the difficulties experienced by the consumer in the context of providing care. An intermediate level of self-determined motivation was also observed to influence students’ self-reported learning outcomes, with individuals ranked at an intermediate level of self-determined motivation reporting significantly higher skills in positive collaboration and observation of consumer emotional difficulties than those reported by the low-motivation group. A similar association was observed in relation to student motivation level and mental health clinical confidence, with confidence in one’s skills observed to be greatest for those highest in motivation. This trend was identified for each motivation group, as students’ confidence in their mental health clinical skills decreased at a statistically significant rate as motivation decreased from the high to moderate to low-motivation groups.

Our findings implicate differences in self-determined motivation as a contributing factor towards student learning in non-traditional settings; furthermore, these data provide evidence for its relevance in mental health settings. Motivation, as an influence on student learning, has been established as an increasingly appropriate factor for educators to consider (Perlman et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Rose, Citation2011; Schuetz, Citation2008). Evidence also indicates that student perceptions of their learning environment may be critical in mediating learning outcomes, particularly in association with influencing motivation and behaviour (Schenke, Citation2018; Eccles, Citation1983; Weiner, Citation1985). These results underscore the relevance, and importance, of these internal factors for professional skill development. Students who actively participate in and construct meaning based on their learning experiences appear to achieve better learning outcomes.

The connection between motivation and professional learning also carries implications for mental health nurse educators. Per the tenets of self-determination theory, educators cultivating student competence, autonomy, and relatedness will bolster student motivation, in turn supporting the development of their mental health nursing skills. In the context of the social isolation and disruption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, facilitating such learning opportunities is particularly important. During the pandemic, significant positive relationships have been identified between perceived educator relatedness and student learning outcomes (Utvær et al., Citation2021). Perceptions of educator relatedness are often characterised by empathy, affiliation, and caring—as such, mental health nurse educators should be reminded that empathetic facilitators promote student professional education (Mikkonen et al., Citation2015; Perry, Citation2009). Additionally, providing opportunities for students to connect theoretical learning with implementing practical skills bolsters student autonomy, in turn fostering intrinsic motivation (Bengtsson & Ohlsson, Citation2010). Our findings cement the importance of educator awareness of these core internal factors affecting nursing student motivation and potential for learning.

As the present study collected data at the summation of the clinical placement, these data do not account for pre-existing levels of student self-determined motivation. Future research can overcome this limitation by utilising a pre- and post-test design to investigate whether non-traditional settings such as Recovery Camp may be associated with significant changes to student learning in association with motivation, as well as maintenance of any changes. Positive changes have been observed and maintained in the context of nursing students’ stigmatising attitudes towards consumers, with student stigma significantly decreasing after attending Recovery Camp and remaining lower at follow-up (Moxham et al., Citation2016). It is also recommended that future research include a measure of student stigma in a pre- and post-test design. Increased stigma towards mental illness has been associated with a devaluation of the skills one needs in relation to mental health nursing (Ross & Goldner, Citation2009). This can result in inflated levels of confidence due to over-estimating one’s skills in relation to mental health nursing care. The present study indexed mental health clinical confidence at the summation of the clinical placement. Though any overconfidence may have been mitigated by real-world experiences throughout the preceding five days of immersive placement, future research in this domain would benefit from controlling for pre-existing stigmatising attitudes.

Conclusions

Our findings align with educational theories that frame learning as a process of active construction meaningfully influenced by motivation. Understanding the role of student self-determination and the potential for professional learning within a mental health clinical placement allows educators to accurately assess the impact of both educational and clinical placement strategies on students’ attitudes regarding mental health nursing, mental illness and working in mental health. The latter is particularly important regarding the workforce, as nursing students actively interested in a career in mental health nursing are “a small minority” (Happell et al., Citation2013, p. 161). Evidence based educational settings such as Recovery Camp may be strategically placed for the effective development of professional skill improvement and clinical confidence, and are particularly relevant given that long-term trends show systematic annual increases in mental health-related hospitalisations (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2022).

Authors’ contributions

Patterson: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Reviewing and Editing Roberts: Software, Data Visualisation, Writing- Original draft preparation Perlman: Software, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation Moxham: Supervision, Conceptualisation, Methodology, Reviewing and Editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Mental Health Productivity Commission Inquiry Report, No. 95, Australian Productivity Commission. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report/mental-health-volume1.pdf

- Basri, F. (2023). Factors influencing learner autonomy and autonomy support in a faculty of education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(2), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1798921

- Beames, S., Higgins, P., & Nicol, R. (2011). Learning outside the classroom: Theory and guidelines for practice. Routledge.

- Bell, A., Horsfall, J., & Goodwin, W. (1998). “The Mental Health Nursing Clinical Confidence Scale” a tool for measuring undergraduate learning on mental health clinical placements. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nurse, 7(4), 184–190.

- Bengtsson, M., & Ohlsson, B. (2010). The nursing and medical students’ motivation to attain knowledge. Nurse Education Today, 30(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.07.005

- Billett, S., Cain, M., & Le, A. H. (2018). Augmenting higher education student’s work experiences: Preferred purposes and processes. Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), 1279–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1250073

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Cregan, A., Perlman, D. J., & Moxham, L. (2016). A self-determination theory perspective on the motivation of pre-registration nursing students [Paper presentation]. Proceedings in QUAESTI: The 4th Year of Virtual Multidisciplinary Conference QUAESTI, Zilina, Slovakia (pp. 180–184) EDIS—Publishing Institution of the University of Zilina. https://doi.org/10.18638/quaesti.2016.4.1.271

- Dziopa, F., & Ahern, K. (2009). Three different ways mental health nurses develop quality therapeutic relationships. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802500691

- Eccles, J.. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.) Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 14–22). San Francisco, CA: Free man.

- Fernet, C., Senécal, C., Guay, F., Marsh, H., & Dowson, M. (2008). The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST). Journal of Career Assessment, 16(2), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305764

- Happell, B., Welch, T., Moxham, L., & Byrne, L. (2013). Keeping the flame alight: Understanding and enhancing interest in mental health nursing as a career. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(4), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.04.002

- Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2015). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO LLC.

- Kumar, R., & Refaei, B. (2017). Problem-based learning pedagogy fosters students’ critical thinking about writing. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 11(2) https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1670

- McGuire-Snieckus, R., McCabe, R., Catty, J., Hansson, L., & Priebe, S. (2006). A new scale to assess the therapeutic relationship in community mental health care: STAR. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291706009299

- Mikkonen, K., Kyngäs, H., & Kääriäinen, M. (2015). Nursing students’ experiences of the empathy of their teachers: A qualitative study. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 20(3), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9554-0

- Moxham, L., Hazelton, M., Muir-Cochrane, E., Heffernan, T., Kneisl, C. & Trigoboff, E. (Eds.). (2018). Contemporary psychiatric-mental health nursing: Partnerships in care. Pearson, Education.

- Moxham, L., Taylor, E., Patterson, C., Perlman, D., Brighton, R., Sumskis, S., Keough, E., & Heffernan, T. (2016). Can a clinical placement influence stigma? An analysis of measures of social distance. Nurse Education Today, 44, 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.003

- Myhill, D., & Warren, P. (2005). Scaffolds or straightjackets? Critical moments in classroom discourse. Educational Review, 57(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191042000274187

- Neutzling, M., Pratt, E., & Parker, M. (2019). Perceptions of learning to teach in a constructivist environment. The Physical Educator, 76(3), 756–776. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2019-V76-I3-8757

- Nóvoa, A., & Alvim, Y. (2020). Nothing is new, but everything has changed: A viewpoint on the future school. Prospects, 49(1-2), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09487-w

- O’Connor, K. (2022). Constructivism, curriculum and the knowledge question: Tensions and challenges for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 47(2), 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1750585

- Orsini, C., Evans, P., & Jerez, O. (2015). How to encourage intrinsic motivation in the clinical teaching environment? A systematic review from the self-determination theory. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 12, 8. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.8

- Paniagua, A., Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as designers of learning environments: the importance of innovative pedagogies, educational research and innovation, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED582804

- Perlman, D., Patterson, C., Moxham, L., & Burns, S. (2020). Examining mental health clinical placement quality using a self-determination theory approach. Nurse Education Today, 87, 104346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104346

- Perlman, D., Taylor, E., Moxham, L., Sumskis, S., Patterson, C., Brighton, R., & Heffernan, T. (2018). Examination of a therapeutic-recreation based clinical placement for undergraduate nursing students: A self-determined perspective. Nurse Education in Practice, 29, 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.11.006

- Perry, B. (2009). Role modelling excellence in clinical nursing practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 9(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.05.001

- Rose, S. (2011). Academic success of nursing students: Does motivation matter? Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 6(4), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2011.05.004

- Ross, C. A., & Goldner, E. M. (2009). Stigma, negative attitudes and discrimination towards mental illness within the nursing profession: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(6), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01399.x

- Schenke, K. (2018). From structure to process: Do students’ own construction of their classroom drive their learning? Learning and Individual Differences, 62, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.01.006

- Schuetz, P. (2008). A theory-driven model of community college student engagement. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 32(4–6), 305–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920701884349

- Tapsell, A., Patterson, C., Moxham, L., & Perlman, D. (2021). Informing work-integrated learning through recovery camp. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 22(1), 73–81.

- Utvær, B. K., Paulsby, T. E., Torbergsen, H., & Haugan, G. (2021). Learning nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of perceived relatedness with teachers and sense of coherence. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 11(10), 9. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v11n10p9

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(2), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.92.4.548

- Wulf, C. (2017). “From teaching to learning”: Characteristics and challenges of a student-centred learning culture. In H. A. Mieg (Ed.), Inquiry-based learning: Undergraduate research (pp 47–55). Springer Open.