ABSTRACT

Objective

Neuroendoscopic resection via supracerebellar infratentorial (SCIT) approach is adequate for some indicated pineal region tumors with the natural infratentorial corridor. We described this full endoscopic approach through a modified ‘head-up’ park-bench position to facilitate the procedure.

Methods

We reviewed the clinical and radiological data of four patients with pineal region lesions who underwent pure endoscopic tumor resection through the SCIT approach with this modified position. The related literature concerning fully endoscopic pineal region tumor resection was also reviewed.

Results

This cohort included four patients with pineal region tumors. External ventricular drainage (Ommaya reservoir) was performed in three patients with hydrocephalus in advance. The average tumor volume was 19.2 ± 17.2 cm3. Pathological examination confirmed two mixed germinomas, one glioblastoma multiforme, and one hemangioblastoma. Gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in all patients, and all patients recovered well without neurological deficits or surgical complications. Hydrocephalus was relieved among all patients.

Conclusions

The pure endoscopic SCIT approach could enable safe and effective resection of pineal region tumors, even for relatively large lesions. The endoscope could provide a panoramic view and illumination of the deep-seated structures. Compared with the sitting position, this modified ergonomic position could be implemented easily.

Introduction

Pineal region tumors could exhibit various pathologies, and radical surgical resection is a mainstay of treatment for most pineal region tumors excluding pure germinoma and primary lymphoma sensitive to chemoradiotherapy [Citation1–3]. Researches have proven that radical resection could win better outcomes for almost all benign pineal tumors as well as most malignant tumors [Citation4–6]. With the development of microsurgical technique and postoperative care, outcomes in the treatment of pineal region tumors have dramatically improved [Citation3,Citation4,Citation7]. However, deep-seated location, proximity to complicated and pivotal neurovascular structure has made it challenging to achieve complete resection with few complications [Citation5,Citation7]. In addition, the limited viewing angle of the surgical field may make it difficult to perform complete resection through microscopy [Citation8]. Microsurgical supracerebellar infratentorial (SCIT) approach to pineal region tumors might require larger craniotomies compared with endoscopic manner [Citation9].

The approaching observation and the wide-angled panoramic view provided by neuroendoscopy could increase the visibility and illumination of the surgical field [Citation8,Citation10]. Full endoscopic resection of pineal region tumors can be performed through the SCIT approach using the natural infratentorial corridor [Citation11,Citation12]. Endoscopy could decrease injury to the bridge veins, cerebellomesencephalic vein (CMV), and Galen vein [Citation10,Citation13]. Additionally, the gross total resection (GTR) rate was significantly higher in the endoscopic surgery for pineal region tumors [Citation8], and the endoscopic SCIT approach might contribute to a lower rate of postoperative complications compared with its microsurgical alternative [Citation14].

The endoscopic SCIT approach is commonly performed in sitting, semi-sitting, or prone position. The prone position could lead to venous engorgement and cerebellar swelling [Citation15]. Although sitting position can facilitate cerebellar retraction away from the tentorium by gravity to enlarge the natural corridor, the air embolism risk was relatively higher in the sitting or semi-sitting position [Citation1]. The modified ‘head-up’ park-bench position could gain enough gravity retraction and diminish the drawback of air embolism, which is also more ergonomic for neurosurgeons. The four pineal region tumor cases with this modified position in this cohort illustrate an alternative for the endoscopic resection. We believe that this technique will allow more complex pineal region lesions to be removed safely and effectively.

Methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Huashan Hospital Institutional Review Board, Fudan University, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Four patients harbouring pineal region lesions since January 2018 who underwent full endoscopic SCIT approach at the Department of Neurosurgery at Huashan Hospital were included. Medical records, and the radiological and pathological images were reviewed. Each patient underwent preoperative MRI, CT, and blood examination of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). An Ommaya reservoir was implanted in patients suffering from severe hydrocephalus.

Operative technique

Patients were placed in the modified left ‘head-up’ park-bench position, with the upper body elevated and the head slightly extended instead of anteflexion. The head was then secured in place with a Mayfield three-pin head clamp and slightly flexed. Neuronavigation was registered in the Stryker Navigation System (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan) and used to determine the optimal ‘head-up’ angle. An occipital midline skin incision and craniotomy approximately 3 × 3 cm in size were made ( d and e). A U-shaped dural incision was made, and the cerebrospinal fluid of the cisterna magna was slowly released to further decrease the intracranial pressure. Through the combination of gravity assistance and reduced pressure, the corridor between the cerebellum and the tentorium could be easily opened.

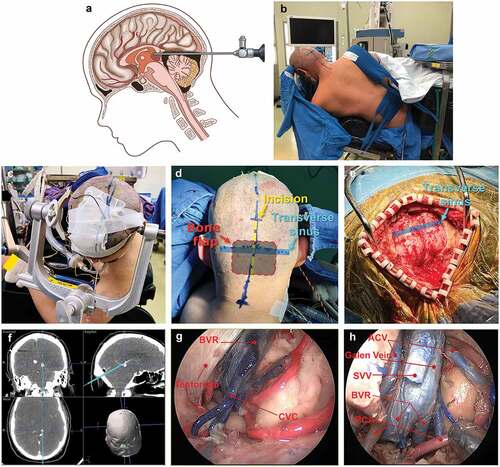

Figure 1. (a) Scheme of the introduction of the 0° endoscope toward the pineal region. Gravity provides retraction of the cerebellum inferiorly to allow the SCIT approach. (b and c) ‘Head-up’ Park-bench position. (d and e) Occipital midline skin incision and craniotomy. (f) Neuronavigation of the cadaver. (g and h) Cadaveric dissection demonstrating pivotal veins. BVR, basal vein of Rosenthal; CVC, central vein of cerebellar vermis; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; SVV, superior vermian vein.

Endoscopic tumor resection

The supracerebellar infratentorial space was first inspected with a 0-degree endoscope (Storz, Germany), and the superficial and deep drainage veins above the vermis were coagulated and transected. The cerebellum was untethered to create space. Below the vein of Galen and between the basal veins, the quadrigeminal cistern was sharply opened to expose the tumor. In most cases, the tumors can be exposed clearly, and some tumor samples were collected for rapidly frozen pathology. The precise plane between the neoplasm and healthy brain tissue needed to be carefully identified, for which approaching observation had an advantage. Devascularization could be attempted first to obtain a clean view. Debulking might be easy with a CUSA ultrasonic dissector if necessary.

If the tumor is hyperaemic, the surgeon should not rush to debulk the tumor but should pay more attention to devascularize the tumor as much as possible. If the tumor has invaded the posterior part of the third ventricle, total tumor resection and opening of the posterior third ventricle are essential. The upper veins can be easily dealt with at the end, and the tumor can be dropped off with the assistance of gravity. A 30° endoscope could be used to observe some corners, such as the lateral thalamic or quadrigeminal cistern blocked by the vermis. A final check was performed with a 0° or 30° endoscope. Dural closure, bone flap fixation, and closure were carried out, as the head could be laid down at this time.

Technique nuance for bleeding control

Anatomically, the blood supply of the pineal gland is mainly from the bilateral medial posterior choroidal arteries, and the rostral stalk of the pineal gland is connected to the bilateral habenula; therefore, to control blood supply of the pineal tumor and mobilize the lesion, the tumor should be first devascularized and disconnected bilaterally.

If massive bleeding happens, the endoscope is immediately partially withdrawn to prevent soiling of the endoscopic lens and suction strength is rapidly increased to aspirate the blood. Moderate irrigation with warm saline and gentle application of appropriately sized gelatin sponge and cottonoid helped control the bleeding. Additionally, dynamic movement of the scope by the assistant was critical to this phase. These steps were repeated a few times. The bleeding point was coagulated by a bayoneted bipolar forceps with angled tips. The surgical field was irrigated, and small oozing was cauterized. There were several measures to avoid endoscope lens soiling, such as withdrawing it once bleeding happens, rinsing lens by assistant, preheating it preoperatively, and taking out endoscope subsequently wiping down the lens. Experienced surgeons took out and wiped down the lens at least every 30 minutes.

Postoperative management and follow-up

Patients were extubated on the operation table and then sent to the postanaesthetic intensive care unit (PACU) for an average duration of 2 hours. The neurologic condition, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate were assessed during the recovery period, with attention to double vision and other cranial nerve problems. The patients were then taken to the neurosurgical intensive care unit (NICU) for the first night after the operation. Patients were treated with routine postoperative care and followed-up closely until recurrence or death.

Literature search

A literature review of pure endoscopic resection for pineal region tumors spanning from March 2008 to February 2022 was conducted. Notably, we excluded endoscope-assisted cases. The endoscope-controlled technique was regarded as another type of purely endoscopic resection.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.3 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA) was utilized for the statistical analysis. The statistical significance of gross total resection (GTR) rate was determined by Fisher’s exact test. All statistical methods were two-tailed tests, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features and outcomes of the four pineal region tumors

The clinical features of the three male and one female patients (30.5 ± 18.2 years old) are described in . All patients reported diverse onset symptoms. The chief complaints included headache (100%), blurred vision (50%), dizziness (33.3%), vomiting (16.7%), and ataxia (16.7%); no parinaud syndrome was observed. Three patients suffered from hydrocephalus and underwent preoperative Ommaya reservoir implantation (cases 1, 2, and 3). β-HCG and AFP levels were in the normal range, with the exception of one patient with mixed germinoma (AFP 24200 µg/L).

Table 1. Case Descriptions of Each Patient in the Series.

The endoscopic surgical procedure is described in the Methods section, and a diagram is shown in . The modified ‘head-up’ park-bench position is a side instead of sitting position, and the head is slightly extended rather than at anteflexion ( b and c). We used this modified ‘head-up’ park bench position to gain enough gravity retraction but diminish the pitfall of semi-sitting position to avoid air embolism. Besides, the surgeon can be seated to enhance the ergonomics. During the craniotomy, the transverse sinus and torcular should be exposed to allow the extensive upward dura-tacking and gain more working space ( d and e). The neuroendoscopic procedure was mimicked with CT navigation on cadavers (). The pineal region could be visualized with neuroendoscopy, and the vein system could be observed in detail ( g and h).

In our study, the mean preoperative tumor and cyst volumes was 19.2 ± 17.2 cm3. Two tumors (50%) were larger than 3 cm, and one was tenacious, and all of them underwent GTR. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of two mixed germinomas, one glioblastoma multiforme, and one hemangioblastomas (recurrent). All patients experienced symptom resolution after surgery. In one patient, headache was only partially resolved. As his hydrocephalus was relieved and stable, no more intervention was needed. Three tumors invading the third ventricle, including one tenacious tumor, underwent GTR without complications. The follow-up period was 16.53 ± 1.06 months. One germinoma patient and one GBM patient underwent chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy, and the other germinoma patient underwent radiotherapy only. No signs of recurrence were reported during follow-up. The progression-free survival of the GBM patients was 18 months.

In this cohort, all such patients underwent GTR without complications. Some unilateral bridging veins were sacrificed to enlarge the field exposure. No postoperative complications were observed. Taken together, the full endoscopic SCIT approach could provide adequate space for radical resection.

Literature review on purely endoscopic resection of the pineal region tumors

There were 14 studies concerning purely endoscopic surgery including 46 cases, as is shown in [Citation10,Citation12,Citation14–25]. The GTR and complication rates were 87.0% (40 cases) and 26.1% (12 cases), respectively. There was no mortality and permanent neurological deficits. Twenty-eight cases (from six studies) were operated in prone position, 14 cases (4 studies) were employed prone position, and 4 cases (4 studies) with semi-sitting position. Pineal cysts were the most common tumor type (13 cases, 28.3%), followed by germinomas (10.9%), five teratomas (three immature, two mature), three yolk sac tumors (6.5%), three pineocytomas, three gliomas, and so on.

Table 2. Literature Overview of Fully Endoscopic Series for Pineal Region Tumors.

SCIT was the commonest approach of endoscopic pineal region tumor surgery (11 studies, 38 cases, 82.6%) with a very low complication rate (7 cases, 18.4%) and high GTR rate (33 cases, 86.8%). Poppen approach was applied in two studies comprising six cases. Five tumors were removed completely (83.3%) and postoperative complications occurred in three cases. Only one study (including two cases) employed the subtorcular approach. GTR was achieved in all cases without complications. The rates of total resection were similar between SCIT and Poppen group (P > 0.99, Fisher’s exact test).

The complication rate of Poppen group was higher than SCIT group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P= 0.1197, Fisher’s exact test), probably due to the extremely small sample size of studies on Poppen approach (six cases). The most common position was the prone position (28 cases from 6 studies, 60.9%). Fourteen cases (30.4%) from four studies were performed in sitting position and semi-sitting position was applied in four cases (8.7%) from four studies.

Case 1 illustration

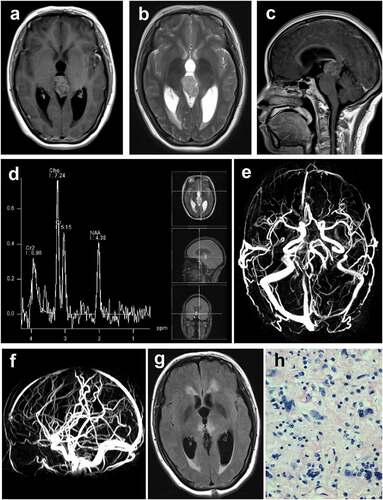

The patient was a 39-year-old woman, and the chief complaint was headache and dizziness for 1 month. Her neurological examination and visual fields were normal. A preoperative MRI scan demonstrated a 1.8 × 1.8 cm short T1 signal, long T2 signal lesion located in the pineal region with heterogeneous enhancement, and hydrocephalus was also observed (). MRS showed that the highest ratio of Cho/NAA was 1.65 (). MRV revealed the sigmoid sinus and the basal sinus were slender on the right ( a nd ). An Ommaya reservoir was implanted in advance because of hydrocephalus. Intraoperative frozen pathology suggested high-grade glioma. The tumor, including the part invading the third ventricle, was completely removed through a fully endoscopic SCIT approach. GTR of the pineal region tumor was confirmed by MR (). Final pathology confirmed glioblastoma multiforme (). The patient recovered well and was discharged after 9 days without any complications, and adjuvant Stupp protocol was administered.

Figure 2. (a and b) Preoperative axial T1‑weighted contrast and T2-weighted MRI scan of the lesion. (c) Preoperative sagittal T2‑weighted contrast MRI scan of the lesion. (d) MRS demonstrates the high ratio of Cho/NAA of the lesion. (e and f) Preoperative MRV scan of the lesion. (g) Postoperative MR scan. (h) Pathology confirmed glioblastoma.

The other three cases are described in the supplementary information.

Discussion

Neuroendoscopy has been widely used for brain tumor resection. A recent systematic review demonstrated that endoscopy was popular and had a lower incidence of complications than microsurgery for pituitary adenoma [Citation26] and skull base tumors [Citation27,Citation28]. Currently, it is widely applied in brain tumor resection, optic nerve and microvascular decompression, and many other kinds of neurosurgeries [Citation29–31]. Although endoscopic resection is optimal for pineal region tumors, especially of moderate dimension (<3 cm) [Citation11,Citation15,Citation32], it is still challenging for large tumors with hard texture and high vascularity.

SCIT approach is popular for pineal region tumor resection due to the natural corridor between the cerebellum and the tentorium [Citation11]. The paramedian SCIT approach may be superior to the classic midline approach in terms of safety, functionality, and avoiding venous sacrifice [Citation13,Citation33]. The drawbacks of the midline approach are the sacrifice of the deep drainage veinous complex of the cerebellum vermis and the need for more cerebellar retraction [Citation13]. However, the rate of GTR, tumor size, and surgical time are similar between the paramedian and midline SCIT approaches [Citation27]. The advantage of the midline approach is to deal with those deep-seated tumors with third ventricle invasion. It would be safe and easy to identify the bilateral planes, which cannot be achieved from the ipsilateral corridor. For giant tumors or tumors with third ventricle invasion, we would recommend median SCIT approach. Since it is easier to access the posterior third ventricle by combining the midline approach with a large bone flap, especially for giant tumors. In this cohort, all tumors invading the third ventricle (cases 1, 2, and 3) achieved GTR, and the posterior third ventricle was opened during surgery with straight visualization. Endoscopy might be inappropriate for tumors larger than 3 cm in some literature [Citation7,Citation15]. We would agree to choose relatively small cases for safety issue, in case of uncontrolled bleeding. By utilizing CUSA and a large midline bone window, two tumors (50%) exceeding 3 cm, including one tenacious, underwent GTR without complications in our cohort. The shortcoming might therefore be the need for a larger bone flap [Citation33].

Neurosurgeons can obtain better exposure in deep-seated region and perform finer dissection between tumor and adjacent structures, leading to less chance of tumor residue in the ventricles [Citation8,Citation10], as endoscopy could provide approaching observation and a wide-angle panoramic view. The GTR rate was significantly higher in the endoscopy group than the microsurgical alternative in pineal region tumors [Citation8]. The endoscopic SCIT technique remarkably improved the ergonomics in that the endoscope actually shortens the working distance and the surgeon can be seated. Larger craniotomies were required by microsurgical SCIT approach compared with its endoscopic alternative, and consequently, the hospital course might be longer for these patients [Citation9]. Additionally, the flexibility of the endoscope allows for superior range of motion and easy manoeuvrability in a tight corridor [Citation14], which can be easily expanded to introduce the endoscope and surgical instruments for bimanual manipulation [Citation15].

Intraoperative bleeding and loss of orientation are the main challenges of endoscopic approach [Citation32]. For hyperaemic tumors, different techniques (described in the Methods section) can be performed to control the massive bleeding. It can show a big advantage in accessing the feeding artery, when the blood mainly comes from the posterior cerebral artery (PCA). The excellent illumination and view of the vascular structures was offered by the scope, thereby reducing the risk of haemorrhage [Citation15]. Gravity reduced the pooling of blood in the operative field [Citation8]. Studies have shown that there is a significant reduction in mean blood loss in endoscopic approaches [Citation34]. Neuro-navigation and relevant landmarks, such as the aqueduct, the pineal recess, the suprapineal recess, and the posterior commissure, could guide the approach and resection.

The prone position (60.9%) was the most commonly used position in fully endoscopic operations followed by sitting (30.4%) and semi-sitting position (8.7%). The natural drooping of the cerebellum due to gravity could provide a sufficient corridor for surgery [Citation12]. Venous air embolism, a rare, life-threatening complication, is most frequent in the sitting position or elevated head position [Citation35,Citation36]. No air embolism was observed in our cohort. The sitting position has the advantage of allowing different working angles, but it is losing popularity due to the increased complications and difficulty [Citation37]. The ‘head-up’ park-bench position is a left modified lateral position that uses gravity-assisted cerebellar dropping. It has a lower incidence of air embolism and allows for intraoperative adjustment. Nevertheless, this position might increase the risk of pressure sores if the operation is time-consuming.

Many patients with pineal region tumors might develop hydrocephalus. Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunting is an alternative [Citation7], and endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) could also relieve obstructive hydrocephalus with potential tumor biopsy [Citation38]. The preoperative Ommaya reservoir can rapidly relieve hydrocephalus and lower brain compliance, avoiding intraoperative haemorrhage due to cranial pressure plunge. Compared with VP shunt and ETV, direct pineal lesion removal with the opening of the posterior third ventricle is more important [Citation39].

According to our experience in this cohort, the modified position and endoscopic SCIT approach could access large pineal region tumors. The advantage of the midline approach is that it helps to deal with deep tumors with third ventricle invasion, as bilateral planes could be identified. The limitation is that the cauda cerebelli may block the visualization of the inferior extreme of the tumor, so the Poppen approach might be appropriate. The modified approach here is easier to conduct, and its indication is important in the clinic.

Conclusions

This modified approach with a full endoscopic technique could achieve GTR of pineal region tumors. It possesses the benefits of traditional approaches and avoids the complications related to cerebellum retraction. The ‘head-up’ park-bench position could be applied quite easily.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr Daniel F. Kelly (Professor of Neurosurgery at Saint John’s Cancer Institute, Director of the Pacific Neuroscience Institute, the Pacific Brain Tumor Center and Pacific Pituitary Disorders Center) for the support and guidance on endoscopy as always.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the article content was composed in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azab WA, Nasim K, Salaheddin W. An overview of the current surgical options for pineal region tumors. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(1):39.

- Bruce JN, Ogden AT. Surgical strategies for treating patients with pineal region tumors. J Neurooncol. 2004 Aug-Sep;69(1–3):221–236.

- Konovalov AN, Pitskhelauri DI. Principles of treatment of the pineal region tumors. Surg Neurol. 2003 Apr;59(4):250–268.

- Hernesniemi J, Romani R, Albayrak BS, et al. Microsurgical management of pineal region lesions: personal experience with 119 patients. Surg Neurol. 2008 Dec;70(6):576–583.

- Qi S, Fan J, Zhang XA, et al. Radical resection of nongerminomatous pineal region tumors via the occipital transtentorial approach based on arachnoidal consideration: experience on a series of 143 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2014 Dec;156(12):2253–2262.

- Tate M, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al. The long-term postsurgical prognosis of patients with pineoblastoma. Cancer. 2012 Jan 1;118(1):173–179.

- Sonabend AM, Bowden S, Bruce JN. Microsurgical resection of pineal region tumors. J Neurooncol. 2016 Nov;130(2):351–366.

- Xin C, Xiong Z, Yan X, et al. Endoscopic-assisted surgery versus microsurgery for pineal region tumors: a single-center retrospective study. Neurosurg Rev. 2021 Apr;44(2):1017–1022.

- Abecassis IJ, Hanak B, Barber J, et al. A single-institution experience with pineal region tumors: 50 tumors over 1 decade. Oper Neurosurg. 2017 Oct 1;13(5):566–575.

- Gu Y, Zhou Q, Zhu W, et al. The purely endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial approach for resecting pineal region tumors with preservation of cerebellomesencephalic vein: technical note and preliminary clinical outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2019 Aug;128:e334–e339.

- Gu Y, Hu F, Zhang X. Purely endoscopic resection of pineal region tumors using infratentorial supracerebellar approach: how I do it. Acta Neurochir. 2016 Nov;158(11):2155–2158.

- Shahinian H, Ra Y. Fully endoscopic resection of pineal region tumors. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013 Jun;74(3):114–117.

- Matsuo S, Baydin S, Gungor A, et al. Midline and off-midline infratentorial supracerebellar approaches to the pineal gland. J Neurosurg. 2016 Jun;126(6):1984–1994.

- Shahrestani S, Ravi V, Strickland B, et al. Pure endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial approach to the pineal region: a case series. World Neurosurg. 2020 May;137:e603–e609.

- Spazzapan P, Velnar T, Bosnjak R. Endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial approach to pineal and posterior third ventricle lesions in prone position with head extension: a technical note. Neurol Res. 2020 Dec;42(12):1070–1073.

- Gore PA, Gonzalez LF, Rekate HL, et al. Endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial approach for pineal cyst resection: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2008 Mar;62(3 Suppl 1):108–9; discussion 109.

- Uschold T, Abla AA, Fusco D, et al. Supracerebellar infratentorial endoscopically controlled resection of pineal lesions: case series and operative technique. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011 Dec;8(6):554–564.

- Sood S, Hoeprich M, Ham SD. Pure endoscopic removal of pineal region tumors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011 Sep;27(9):1489–1492.

- Tseng KY, Ma HI, Liu WH, et al. Endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial retropineal approach for tumor resection. World Neurosurg. 2012 Feb;77(2):399 E1–4.

- Thaher F, Kurucz P, Fuellbier L, et al. Endoscopic surgery for tumors of the pineal region via a paramedian infratentorial supracerebellar keyhole approach (PISKA). Neurosurg Rev. 2014 Oct;37(4):677–684.

- Snyder R, Felbaum DR, Jean WC, et al. Supracerebellar infratentorial endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted approaches to pineal lesions: technical report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2017 Jun 9;9(6):e1329.

- Sinha S, Culpin E, McMullan J. Extended endoscopic supracerebellar infratentorial (EESI) approach for a complex pineal region tumour-a technical note. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018 Jul;34(7):1397–1399.

- Tanikawa M, Yamada H, Sakata T, et al. Exclusive endoscopic occipital transtentorial approach for pineal region tumors. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:167–173.

- Fernandez-Miranda JC. Paramedian supracerebellar approach in semi-sitting position for endoscopic resection of pineal cyst: 2-dimensional operative video. Oper Neurosurg. 2019 Mar 1;16(3):E79.

- Tanikawa M, Yamada H, Kitamura T, et al. Endoscopic occipital transtentorial approach for pineal region tumor. Oper Neurosurg. 2018 Feb 1;14(2):206–207.

- Li A, Liu W, Cao P, et al. Endoscopic versus microscopic transsphenoidal surgery in the treatment of pituitary adenoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:236–246.

- Kasemsiri P, Carrau RL, Ditzel Filho LF, et al. Advantages and limitations of endoscopic endonasal approaches to the skull base. World Neurosurg. 2014 Dec;82(6 Suppl):S12–21.

- Martinez-Perez R, Requena LC, Carrau RL, et al. Modern endoscopic skull base neurosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2021 Feb;151(3):461–475.

- Paluzzi A, Gardner P, Fernandez-Miranda JC, et al. The expanding role of endoscopic skull base surgery. Br J Neurosurg. 2012 Oct;26(5):649–661.

- Caporlingua A, Prior A, Cavagnaro MJ, et al. The intracranial and intracanalicular optic nerve as seen through different surgical windows: endoscopic versus transcranial. World Neurosurg. 2019;124:522–538.

- Piazza M, Lee JY. Endoscopic and microscopic microvascular decompression. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016 Jul;27(3):305–313.

- Schonauer C, Jannelli G, Tessitore E, et al. Endoscopic resection of a low-grade ependymoma of the pineal region. Surg Neurol Int. 2021;12:279.

- Choque-Velasquez J, Resendiz-Nieves J, Jahromi BR, et al. Midline and paramedian supracerebellar infratentorial approach to the pineal region: a comparative clinical study in 112 patients. World Neurosurg. 2020;137:e194–e207.

- Prajapati HP, Jain SK, Sinha VD. Endoscopic versus microscopic pituitary adenoma surgery: an institutional experience. Asian J Neurosurg. 2018 Apr-Jun;13(2):217–221.

- Anan’ev EP, Polupan AA, Savin IA, et al. [Paradoxical air embolism resulted in acute myocardial infarction and massive ischemic brain injury in a patient operated on in a sitting position]. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2016;80(2):84–92.

- Matjasko J, Petrozza P, Cohen M, et al. Anesthesia and surgery in the seated position: analysis of 554 cases. Neurosurgery. 1985 Nov;17(5):695–702.

- Choque-Velasquez J, Colasanti R, Resendiz-Nieves JC, et al. Venous air embolisms and sitting position in Helsinki pineal region surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2018;9:160.

- Kennedy BC, Bruce JN. Surgical approaches to the pineal region. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2011 Jul;22(3):367–80, viii.

- Choque-Velasquez J, Resendiz-Nieves J, Colasanti R, et al. Management of obstructive hydrocephalus associated with pineal region cysts and tumors and its implication in long-term outcome. World Neurosurg. 2021;149:e913–e923.