ABSTRACT

Decisive action against criminal outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs) ranks high on the criminal justice agenda. Nevertheless, in many Western European countries the number of OMCG chapters has increased rapidly. Official OMCG support clubs also have mushroomed. The present study extends prior research from the Netherlands and elsewhere by employing a gang database of 1,617 OMCG members and 473 support club members maintained by the Dutch police and examining members’ juvenile and adult criminal careers based on judicial data. While committing an offense was no prerequisite of being included in the database, criminal career data show that the majority of OMCG and support club members is convicted at least once. In addition, we find there is ample variation in both the level and shape of these individual’s criminal trajectories. In line with prior research, the majority of OMCG and support club members are found to be adult onset offenders. A considerable share of both samples however, follows criminal trajectories characterized by early onset, frequent and persistent criminal behavior. Building on prior theoretical accounts of OMCG evolution, these findings are interpreted against the background of recent changes in the Dutch outlaw biker landscape. Implications for the Dutch whole-of-government approach are discussed.

Introduction

After a parliamentary investigation into organized crime suggested that the Dutch Hells Angels were involved in extortion and drug trafficking (Fijnaut and Bovenkerk Citation1996), a number of much talked about public displays of power (Burgwal Citation2012), and various failed attempts to get the Hells Angels banned (Schutten, Vugts, and Middelburg Citation2004), the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice made outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs) top priority. This resulted in an encompassing ‘whole-of-government’ approach, in which local governmental agencies, Fiscal Information and Investigation Service, and the National Police of the Netherlands joined forces to raise as many barriers as possible to OMCG criminal activity and to discourage OMCG membership in general (Van Ruitenburg Citation2016). The approach focused on the public presence of OMCGs, the financial position of OMCGs and OMCG members, and their mobility and assets. This was put into practice by closing down OMCG clubhouses if a legal opportunity arose, prohibiting biker events and the continuously monitoring of businesses vulnerable to OMCG infiltration, like private security and the hospitality industry (LIEC Citation2017, Citation2018; Secretariaat Generaal Benelux Unie Citation2016; Van Ruitenburg Citation2016). Over the years, prosecutors have argued that members and leaders of Dutch OMCGs are disproportionately involved in serious and violent crimes, including drug trafficking and extortion. OMCGs are claimed to constitute criminal structures that facilitate contact between likeminded individuals and encourage crime through maintaining a culture of violence and disrespect for the law.Footnote1

Academic research into OMCGs and their involvement in (organized) crime is still scarce. The available studies, however, suggest that many OMCG members indeed have criminal records, and that these records often pertain to more than just traffic offenses and disorderly behavior. Barker (Citation2015) cites results from a survey among 1,061 US law enforcement agencies that found that 90% of known OMCG members had engaged in narcotics distribution, 76% were reported to engage in narcotics manufacturing, and 53% were reported to engage in money laundering. Violent offenses like assault (88%) and rape (39%) were also common among US outlaw bikers. Early Canadian research showed that 70% of OMCG members had a criminal record (Tremblay et al. Citation1989). Research published during a period of intensified intergang rivalry among Canadian OMCGs even found that 95.5% of OMCG members had a criminal record (Barker Citation2015: 148). Scandinavian OMCG members are also likely to be convicted criminals with percentages of convicted OMCG members ranging from 69% in Norway, 56–75% in Sweden, and 92% in Denmark (Klement Citation2016). In a recent study on criminal networks of Swedish Hells Angels and Red Devil MC members, Rostami and Mondani (Citation2019) found that 97% of the former and 85% of the latter were registered as a crime suspect at least once. Alcohol, drugs, and firearms violations were prevalent among members of both clubs, as were theft and robbery and assault. White color crimes were especially prevalent among Hells Angels members. Finally, Australian research found that of all known OMCG members in Queensland, 47% had a criminal record. However, this excluded traffic violations and petty offenses (Houghton Citation2014). A study on Australia’s Gold Coast Finks MC found that all members had committed traffic offenses, and many had committed minor drug offenses (Lauchs Citation2019). The picture emerging from these studies is that, regardless of geographical location, OMCG membership is associated with disproportional criminal involvement, at least for minor offenses.

To increase their knowledge position on Dutch OMCGs, in 2014 the National Police of the Netherlands issued a report methodically describing the Dutch outlaw biker scene (National Police Citation2014). Part of this report was a study into the criminal careers of a sample of 601 Dutch OMCG members. This study showed that over 80% of Dutch OMCG members had a criminal record, measuring over eight convictions on average. Over one in four had more than 10 convictions to their name. With regard to the nature of their offenses it was found that 47% of convicted OMCG members was convicted at least once for a violent offense and over 22% was convicted for at least one drug offense. One in three convicted Dutch bikers had spent time in prison (Blokland et al. Citation2019). This prior research however also found important differences in the extent to which members of different clubs were involved in criminal behavior as well as in the nature of their offenses (Blokland, Soudijn and Van der Leest Citation2017). More specifically, in 11 of the 12 Dutch OMCGs studied over 50% of members had conviction histories. Yet, only for six clubs this percentage topped 80%. Furthermore, members of some clubs were found to be responsible for a disproportionate share of all drug crimes recorded for the entire sample.

In their 2014 report, the Dutch police highlight a number of important, ongoing, changes in the Dutch outlaw biker scene (National Police Citation2014). As of 2011, the number of Dutch OMCG chapters—and with it in all likelihood the number of OMCG members—started to rapidly increase (see ). Exemplary for these dynamics is No Surrender which, established as recent as 2013, succeeded to evolve into what is currently one of the largest Dutch OMCGs and also established chapters in several other countries. In 2014, the international OMCGs Bandidos and Mongols also set up camp on Dutch soil, further increasing intergang tensions in the continuously changing Dutch biker landscape. Such a rapid increase in the number of OMCG members signals that traditional initiation procedures have—for the moment at least—been abandoned, which, in turn, opens the door to OMCG membership for individuals who, under normal conditions, would be unlikely to meet membership standards (Quinn Citation2001).Footnote2 The 2014 report, for instance, mentions that several OMCGs are suspected of actively recruiting members from football hooligan groups (see also: RIEC-LIEC Citation2014). Furthermore, along with the upsurge in OMCG chapters, the number of Dutch OMCG support clubs also mushroomed. These support clubs, which may or may not be motorcycle clubs themselves, are officially affiliated to one of the 13 OMCGs active in the Netherlands at the time of writing the police report (National Police Citation2014). To date however, support clubs, have rarely been subject of scientific inquiry (Thomas Citation2017).

Figure 1. The number of OMCG chapters per clubs, March 2011–June 2016.

The restricted sample size of prior Dutch studies into the criminal careers of OMCG members and the rapidly changing outlaw biker landscape limit the potential to generalize previous results to the entire Dutch outlaw biker population. Furthermore, these prior studies did not have data on members of OMCG support clubs. As members of support clubs have been suggested to be used to keep OMCG members at arm’s length from committing offenses high in risk of apprehension (e.g. LIEC Citation2016; Rostami and Mondani Citation2019; Smith Citation2002), and because support clubs can be strategically put to use by rivaling OMCGs in situations of intergang conflict (Quinn Citation2001; Smith Citation2002), gaining insights into the criminal careers—or the lack thereof—of OMCG support club members is also important.

The current study seeks to add to the literature on the criminal involvement of OMCG members and extends prior Dutch research on the topic by analyzing the officially registered criminal careers of OMCG members (N = 1,617) and support club members (N = 473). Following the National Academy of Sciences Panel on Research on Criminal Careers definition (Blumstein et al. Citation1986) we define the criminal career as the longitudinal sequence of crimes committed by an individual offender. Distinct dimensions of outlaw bikers’ criminal careers beyond the mere prevalence of a conviction history are looked into, like the age of onset, frequency, crime mix and duration of offending (Piquero, Farrington, and Blumstein Citation2003). The following research questions will be answered:

What are the important features (participation, frequency, crime mix, and duration) of the criminal careers of members of Dutch OMCGs?

What are the important features (participation, frequency, crime mix, and duration) of the criminal careers of members of Dutch OMCG support clubs, and to what extent do they differ from those of OMCG members?

To what extent can distinct developmental criminal trajectories be distinguished in the criminal careers of Dutch OMCG and OMCG support club members?

Data and methods

Sample

The sample used for the present study consists of 2,090 individuals, that, by means of an officially registered observation of a sworn-in police officer, were identified as being affiliated to a Dutch OMCG (N = 1,617), or to an official Dutch OMCG support club (N = 473), in the period 2010–2015.Footnote3 To be recognized as an OMCG or support club member the identity of the individual had to be ascertained by the reporting police officer, and affiliation to the OMCG or support club had to be apparent, for example by the individual wearing a club vest, club tattoos, or other club insignia, or by regularly attending closed club meetings and events. Suspicion of having committed a crime is not a prerequisite for registration that led to inclusion in the current sample, as registration could also follow from general police actions, like large-scale sobriety checks. Police estimates are that only a small percentage of registrations occurred in the direct context of a criminal investigation. Apart from the particular club these individuals were affiliated with, their status in the club was also recorded to the extent this could be deduced from, for instance, markings on their vests. Registration of membership status, as well as club rank was done conservatively, such that an individual suspected of being a member based on his regularly attendance of club events, is registered as an associate if he is not also observed wearing club clothing.

At the time of sampling, 13 OMCGs were active in the Netherlands.Footnote4 As in other countries, the exact number of Dutch OMCG members and their characteristics are unknown. There has been ample discussion in the (street)gang literature on the problems and pitfalls of using law enforcement data to study deviant groups (Barrows and Ronald Huff Citation2009). Typically, when using law enforcement data researchers have no influence on who exactly is registered as a ‘gang member’, and why. This makes such gang databases liable to both type 1 and type 2 errors. Type 1 errors refer to instances in which individuals are registered as gang members who in actuality are not affiliated to a gang. To the extent that these individuals are more or less criminal than actual gang members this might bias our understanding of the criminal involvement of gang members. Type 2 errors refer to instances were individuals who are actual gang members, are not registered as such, for example because of their young age, limited membership duration, or lack of criminal behavior. When rule abiding outlaw bikers are less likely than their rule breaking counterparts to be known to the police as OMCG members, type 2 errors will bias estimates of gang members’ criminal involvement upwardly. Given that a recognizable public appearance is integral part of the outlaw biker subculture, potential bias resulting from type 1 errors in this case seems less problematic than potential bias resulting from type 2 errors. While the extent to which the current sample is statistically representative for the entire Dutch OMCG membership population necessarily remains unknown, by way of sensitivity analysis, we calculate the potential effects of type 2 error bias on the estimated proportion of OMCG members with a criminal history under different hypothetical scenarios.

Criminal careers

Information on the criminal histories of the OMCG and support club members was retrieved from extracts from the Judicial Information System. These extracts provide information on the number, timing, and nature of all criminal cases registered at the Dutch public prosecutor’s office, the type of adjudication of these cases, and, when applicable, the type and severity of the sentence imposed. Using these abstracts, we were able to reconstruct the criminal histories of all OMCG and support club members in the current sample from age 12—the minimum age of criminal responsibility in the Netherlands—up to their age in December 2015—the end of the data collection period for the current study. Here, for reconstructing OMCG and support club members’ criminal histories we only took into account those cases that ended in a guilty verdict by a Dutch judge, a prosecutorial fine, or prosecutorial waiver for policy reasons, thus excluding acquittals and prosecutorial waivers for lack of evidence. For reasons of brevity, guilty verdicts, prosecutorial fines, and policy waivers are referred to in the following text as ‘convictions’. Given that inclusion in the sample was based solely on observed OMCG membership, subsuming fines and policy waivers under convictions do not affect the sampling frame.

Group-based trajectory models

To distinguish between groups of OMCG and support club members showing similar criminal career patterns, we use group-based trajectory models, or GBTM (Nagin Citation2005; Nagin and Land Citation1993). GBTM can be used to summarize large amounts of longitudinal information—in our case criminal career information—into a limited number of developmental trajectories. These trajectories can differ in both level and shape and can be thought of as latent classes in the longitudinal data. For the current analyses, we estimated GBTMs of 1–10 groups, both for the entire sample, as well as separately for OMCG and support club members. The optimal number of groups was determined based on BIC and AIC values, and the other criteria of model fit mentioned by Nagin (Citation2005)—e.g. average posterior probabilities, and odds of correct classification. Apart from the optimal number of groups, GBTM provides the posterior probabilities of group membership for all individuals in the analysis. Based on the maximum posterior probability OMCG and support club members were classified as belonging to a certain trajectory group.

Results

Demographic profile

The average Dutch outlaw biker is a Dutch male is his forties (see ). This is in line with prior research (Blokland, Soudijn, and Teng Citation2014). It should be noted however that demographic information was only available for OMCG and support club members that were convicted at least once. To the extent that OMCG or support club members with a criminal history differ from those without a criminal history, these results may be biased. Furthermore, ethnicity is based on the individual’s country of birth, so second-generation immigrants are categorized as ‘Dutch’. shows significant differences in the age distribution of OMCG and support club members, the former being older on average. Over 60% of the OMCG members is aged 40 years or older. While over half of support club members is also over 40, at the same time more than 25% of support club members is under 30. This suggests that membership of an OMCG support club is also open and attractive to young adults, and, in as far as support clubs serve as incubators, we might see a new generation of outlaw bikers in the near future.

Table 1. Demographic and criminal career characteristics of Dutch OMCG and support club members.

Prevalence and frequency of convictions

provides the prevalence and average frequency of convictions for both OMCG and support club members. Over 85% of Dutch OMCG members is convicted at least once compared to 78% of Dutch support club members. Additional analysis suggests that these convictions are not just youthful indiscretions; two-thirds of OMCG and support club members had their last conviction registered between 2010 and 2015. Those OMCG members with a conviction history were convicted 9.4 times on average. Convicted members of support clubs averaged 8.8 convictions. Of those convicted almost one in three OMCG members has over 10 convictions, for convicted support club members this is 28%. Support club members are thus not only less likely than OMCG members to have a criminal record, but those support club members that do, tend to also have a less elaborate criminal history than convicted OMCG members.

Due to their high number of convictions, chronically offending members, disproportionally contribute to the total volume of convictions registered for the present sample. The extent to which convictions are concentrated in a relatively small share of the OMCG and support club member population can be visualized by means of a Lorenz curve. Whereas in economics the Lorentz curve is commonly used to graphically display inequality in the distribution of wealth, in criminal career research Lorenz curves, and derivate measures like the Gini index or α are used to gain insight into the relative contribution of chronic offenders to overall crime (Bernasco and Steenbeek Citation2017; Fox James and Tracy Citation1988). The Lorenz curve for the distribution of convictions in our sample is given in . The percentage of members is on the x axis, the percentage of convictions on the y axis. If all members were equally contributing to the overall volume of convictions—e.g. 10% of the members found responsible for 10% of all convictions—the Lorenz curve would show a straight, diagonal line. The more the observed curve deviates from this diagonal line, the more convictions are concentrated in a relatively small group of chronic offenders. The left pane of gives the Lorenz curve for all members in the sample by OMCG and support club membership, the right pane depicts the Lorenz curve for convicted members only. The left pane of shows that 10% of OMCG members is responsible for 40% of all registered convictions. Forty percent of OMCG members is responsible for 80% of convictions. At first glance, it appears that convictions are more concentrated in support club members, but the right pane of , that is restricted to convicted members only, shows that this is due to the larger share of support club members without any conviction—and thus not contributing to the overall volume of convictions. When only those members with a conviction history are considered, the Lorenz curves for OMCG and support club members almost overlap. That OMCG and support club members do not differ in the extent to which convictions are concentrated in a small share of highly criminally active offenders also becomes apparent when comparing Gini indices across these groups—0.54 and 0.60 when all OMCG and support club members are considered, and 0.46 and 0.48 when only convicted OMCG and support club members are taken into account.

Figure 2. Lorenz curve for the total number of convictions for OMCG and support club members (left pane), convicted OMCG and support club members (right pane).

Both the percentage of ever convicted OMCG members, as well as the percentage of OMCG members with at least 10 convictions is higher than in previous research (Blokland, Van Hout, Van der Leest and Soudijn Citation2019). Unlike in prior research however, the present analysis also cover convictions for misdemeanors which may explain these differences. When only felony cases are considered, 19.9% of OMCG members has a criminal history of 10 or more convictions.

Nature and severity of offenses

Judging by their conviction histories OMCG and support club members engage in various types of offenses. Of the sentenced OMCG members in our sample 56.7% is convicted of a violent offense at least once, compared to 49.7% of convicted support club members. Other expressive offenses, like public order offenses (i.e. resisting arrest, public violence) are common, with 45.5% and 38.6% of convicted OMCG and support club members are convicted at least once for such an offense. OMCG members, and to a lesser extent support club members, are also convicted for offenses that could be taken to signal more organized types of crime. One in three OMCG members and one in four support club members is convicted for a drug offense, which, in the Dutch context in which possession of illegal substances for personal use is decriminalized, pertains to the production, sale or trafficking of narcotics. Three out of 10 OMCG and support club members were convicted for transgressions of the Weapons and Ammunition Act. Eleven percent of OMCG members and nearly 8% of support club members have been convicted for what Quinn and Koch (Citation2003) would refer to as ‘ongoing criminal enterprises’, preplanned offenses that demand continuous attention and are aimed at generating substantial illegal profits.Footnote5 Here, we label the latter type of offenses ‘organized crime’.

The nature of the offense, especially when classified based on the relevant section of the criminal code, only provides limited information on the severity of the offense. Both shoplifting and the theft of a truckload of consumer goods, for instance would be prosecuted under the same section of the Dutch criminal code—i.e. simple theft. The number and severity of the penalties imposed on convicted members offers a complementary perspective to judge the severity of outlaw biker crimes. shows that almost three quarters of OMCG and support club members have been fined. Of the convicted OMCG members, 36.7% was sentenced to imprisonment at least once, compared to 30.3% of convicted support club members. Those convicted to imprisonment at least once, on average served three prison terms. The average length of imprisonment was 2.4 years for OMCG members and 1.8 years for support club members. Both analyses of the types of offenses members are convicted for and the severity of the imposed penalties support the conclusion that on average OMCG members commit more serious crimes than support club members.

Criminal careers

On average, Dutch OMCG and support club members experience the onset of their criminal career—measured here as the age of first conviction—in their early twenties. This is about 7–8 years younger than the average age of onset for OMCG members found in prior studies (Blokland, Van Hout, Van der Leest and Soudijn 2017), yet comparable to the average age of onset found in organized crime offenders (Van Koppen, de Poot, and Blokland Citation2010). OMCG members in the present sample are younger on average at the time of sampling then members in the previous OMCG study, more often have a conviction history, are younger when first convicted, and when convicted, have more elaborate criminal histories. These differences may result from changes in OMCG membership in the years between the previous and the current studies. However, based on the available data, alternative explanations for these differences, like changes in the representativeness of the sample for the entire OMCG member population, or an increased likelihood of conviction given the policy attention directed toward OMCGs, or a combination of these, cannot be ruled out.

depicts the age-crime curve for both OMCG and support club members, based on the proportion of members convicted at least once at each age.Footnote6 The dots represents the observed proportions, the solid line depicts the smoothed age-crime distribution by means of LOESS smoothing.Footnote7 shows the proportion of members convicted steeply rises to a peak around age 20 and then slowly decreases with age. Still, over 12% of OMCG members in the current sample is convicted at age 50. The age-crime curve for support club members is similarly shaped, yet on a slightly lower level. From age 18 onward the proportion of support club members convicted fall below that of convicted OMCG members. The gray bars depict the age-crime curve based on the total number of suspects registered by the police in 2015. While the age-crime curve for OMCG and support club members is based on longitudinal data (individual members followed through time) and the national suspect data is a cross-section, the shape of the Dutch age-crime curve provides a benchmark for comparison. The Dutch age-crime distribution for 2015 peaks a few years earlier—what could result from the fact that the cross-sectional curve is based on suspects, and the longitudinal data on convictions. Most important however, may be that the curve for all Dutch suspects shows a sharper decrease after the peak age than do the age-crime curves for both OMCG and support club members. While the proportion of OMCG and support club members does decline with age, this decline takes longer to materialize.

Developmental trajectories

On average, OMCG members start their criminal career at age 21. The standard deviation around that mean however is considerable indicating the 95% of OMCG members experiences their first conviction between ages 12 and 38 (21 ± 2*8.3). The same applies to support club members. This wide variety in age of first conviction mirrors findings from previous criminal career studies on OMCG members (Blokland et al. Citation2019), organized crime offenders (Van Koppen et al. Citation2010), and offenders in general (Blokland Citation2005) that featured a long-term follow up. Analyses furthermore show that the frequency of convictions was not equally distributed across members. As depicted in , we find that for both OMCG and support club members age of onset is correlated with the frequency of convictions—defined here as the mean number of convictions per time free to account for both age differences in 2015 and time spent incarcerated.Footnote8 The 95% confidence intervals of however, again indicate that despite significant correlations between onset and frequency of convictions—−0.40 for OMCG and −0.32 for support club members—considerable variation at each age.

Figure 4. Average frequency of convictions by time free between age 12 and age in 2015 by age of first conviction for OMCG and support club members.

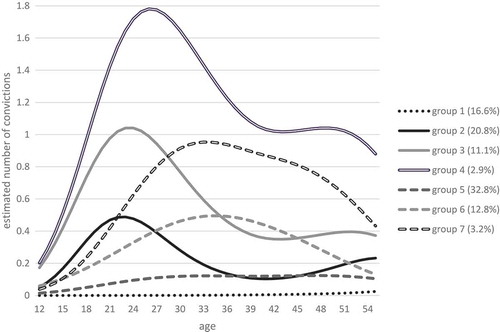

The age-crime curve in masks such associations between criminal career dimensions and therefore possible distinct developmental patterns in the conviction histories of OMCG and support club members. To examine to what extent different developmental trajectories could be distinguished in our data, we use GBTM. Members categorized in the same trajectory group show similar developmental patterns in both the timing and frequency of their convictions. The seven-group model showed the best fit to our data for both OMCG and support club members. Resulting trajectories for the model on the entire sample are presented in .Footnote9

Group 1, constituting 16.6% of the total sample, consists of members that are hardly convicted or even not at all. Groups 2, 3, and 4 show a similar age-conviction pattern, but differ in the level of convictions. The conviction trajectory of group 2 peaks at age 23 with an estimated average of 0.49 convictions per year. The average number of convictions decreases thereafter, seemingly reaching a plateau after age 35.Footnote10 Groups 3 and 4 show a comparable peak during the early to mid-twenties. For these groups the subsequent decrease in convictions also comes to a standstill at a level considerably higher than zero. For those following the trajectory of group 4 the estimated number of convictions between ages 40 and 50 is still one per year. The shape of trajectories 2, 3, and 4 resembles the classic age-crime curve found in prior studies (Farrington Citation1986), with the exception that in most samples crime levels decrease to near zero during older ages (Piquero Citation2008). Over one-third (34.8%) of OMCG and support club members is categorized as following one of these trajectories.

The conviction trajectories of groups 5, 6, and 7 show a quite different developmental pattern. For members following these trajectories the peak age of conviction is around 10 years later and both the ascent to this peak and the following descent is much more gradual than for groups 2, 3, and 4. Not only does the criminal behavior of members allocated to these trajectories seem to increase during a period in which desistance from crime is considered normal, their criminal careers persist until ages older that prior research on the age-crime distribution would suggest (e.g. Farrington Citation1986).

provides the distribution of OMCG and support club members across the seven conviction trajectories. The distribution of support club members across trajectories does not significantly differ from that of OMCG members.

Table 2. Distribution of OMCG and support club members across conviction trajectories.

Finally, and provide descriptive statistics for both demographic and criminal career characteristics across all groups for respectively OMCG and support club members. A number of results stand out. First, shows that OMCG members with the most elaborate conviction histories are the youngest on average. This corroborates the hypothesis that the recent growth of OMCGs was achieved by recruiting or accepting for membership individuals with a criminal past. However, as mentioned before, alternative scenarios explaining this pattern cannot be ruled out based on conviction data alone. Second, the percentage of convicted members per trajectory underlines the fuzziness of trajectory group boundaries. Of OMCG members categorized in group 1, 12.4% is convicted at least once, while 1.9% of members in group 5 are not. Unsurprisingly this concerns members for which the posterior group probabilities for groups 1 and 5 are comparable: in other words the model has difficulty allocating these individuals to either one of these group. Third, almost nine out of 10 OMCG members in group 3, 4, or 7 are convicted at least 10 times. OMCG members allocated to these groups also have the highest probability to be convicted of a drug offense (respectively 62.7%, 73.3%, and 69.1%). Furthermore, over 46% of OMCG members in group 4 and 30% of OMCG members in group 7 is convicted of an organized crime offense at least once. Despite these similarities, an important difference between OMCG members in groups 4 and 7 is that those in group 4 mostly experienced the official onset of their criminal careers prior to reaching adulthood, while those allocated to group 7 are predominantly adult onset offenders who were first convicted after age 18. Finally, while a similar percentage of OMCG members in groups 4 and 7 has been sentenced to imprisonment at least once, the average frequency of imprisonment in group 4 is twice as high as in group 7. This may be due to the relatively early onset of the criminal careers of OMCG members in group 4 and the, relative to group 7, high prevalence of drug offenses. Both extensive criminal records and convictions for drug offenses increase the likelihood of receiving a prison sentence.

Table 3. Demographic and criminal career characteristics of OMCG members, per trajectory group.

Table 4. Demographic and criminal career characteristics of support club members, per trajectory group.

provides the same information only now for the support club members. The results for support club members show patterns similar to that in OMCG members. However, given the smaller overall sample size for support club members, it should be noted that the demographic profile for group 1, and the demographic and criminal career profiles for groups 4 and 7 are based on a limited number (convicted) support club members allocated to these groups. Groups 3, 4, and 7 also harbor the largest proportion of chronically offending support club members. Support club members allocated to group 4 all have criminal histories spanning at least 10 convictions. Like among OMCG members, the prevalence of convictions for drug offenses among support club members is also highest in groups 3, 4, and 7. Yet, in each of these groups, this prevalence is lower for support club members than that for OMCG members. The percentage of support club members convicted for an organized crime offense in these trajectory groups varies between 13.3% and 27.3%. Support club members in group 7 are also categorized by an adult onset of their criminal careers. Finally, and similarly to OMCG members allocated to these groups, while the prevalence of imprisonment is comparable for support club members in groups 4 and 7, support club members in group 4 experience a higher number of imprisonment spells on average, than do those in group 7 (respectively 7.8 versus 3.8 times).

Potential bias resulting from type 2 errors

The Dutch OMCG members that are known to the police are unlikely to constitute a fully random sample of Dutch outlaw bikers. As such, generalization of the current results to the entire Dutch outlaw population is problematic. Especially, type 2 errors may result in overestimating the criminal involvement of Dutch OMCG members in case those members criminally active are especially prone to become known to the police. The extent of bias resulting from type 2 errors however, depends on both the number of members that go unrecognized and the prevalence of crime in this group. Barker (Citation2012) argues that in the US the number of OMCG members per chapter is between 6 and 25. Dutch police experts suggest these numbers also reflect the Dutch situation, though exceptionally large chapters may have as much as 40 members (National Police Citation2014). Given that 148 OMCG chapters were known at the time of sampling, the current sample of 1,617 OMCG members amounts to an estimated number of 11 members per chapter. The more the actual number of members per chapter deviates from this estimate, the larger the proportion of the Dutch outlaw biker population currently goes unregistered, and hence, the larger the potential bias resulting from type 2 errors. Potential type 2 error bias also varies with the extent that the group of registered OMCG members differs from the unregistered group in terms of having a criminal history. depicts the effects of type 2 error bias under different combinations of these two factors. In the extreme case of all unregistered OMCG members having no criminal record, the percentage of OMCG members ever convicted in the actual total population might be as low as 28.4% if the current sample constitutes only one third of the actual population. In the equally unlikely event that all unregistered OMCG members do have a criminal record and the sample representing a similar fraction of the total population, the actual percentage of OMCG members having a criminal record could be as high as 95.3%. Given that previous research found that 32.3% of all middle-aged Dutch male motorcycle owners had a criminal record (Blokland et al. Citation2019), and based on a population size estimate derived from an average of 25 members per chapter maximum, a more reliable estimate of the proportion of members having a criminal record in the total OMCG member population would be somewhere between 55.7% and 85.8%.

Discussion

Results of the present study corroborate those from previous studies into the criminal histories of OMCG members, both Dutch and international: the large majority of OMCG members in the current sample was convicted at least once. For over half, their latest conviction was in the 5 years prior to the moment of sampling. OMCG members were convicted for violent offenses and offenses that indicate more organized types of crimes, like drug offenses, extortion, and money laundering. Results however also show that there is ample variation among OMCG members in terms of their total number of convictions, as well as in the timing of onset of their criminal careers. GBTM analyses showed that seven developmental trajectories can be distinguished in the conviction histories of the current sample of OMCG and support club members. Three of these trajectories show a peak in offending during the adolescent and early adult years—as could be expected from the age-crime curve typically found in criminological studies. The other three trajectories identified however, show a developmental trajectory of convictions that is much more spread out. These trajectories are characterized by a higher proportion of adult onset offenders.

While the present results are generally in line with the outcomes of prior studies into the criminal careers of Dutch OMCG members, there are some important differences as well. For one, the percentage of convicted OMCG members that was first convicted prior to age 18 is over three times higher in the current sample, than was found in an earlier sample of Dutch OMCG members (Blokland, Soudijn, and Teng Citation2014; Blokland et al. Citation2019). While the conclusion that most OMCG members do not seem to meet the criteria for early starting, persistent offenders still holds, the present study did identify a group—or rather multiple groups—of OMCG members who experience both an early start of their criminal career, and show a highly frequent and persistent pattern of convictions. These findings could indicate that, partly because of the unprecedented growth some Dutch OMCGs were able to realize, the OMCG membership population is undergoing substantive changes, in which new members—less well represented in earlier studies—show a different criminal profile from founder members. These new members seem to be characterized by having developed an elaborate criminal history in the years (long) before their OMCG membership. To the extent these individuals would not have classified as OMCG members before, or to the extent these types of individuals are especially recruited by OMCGs in times of lurking intergang conflict, these findings fit the image of changing membership criteria and an attenuated—or even—largely discarded prospecting period. Alternative explanations, like a better coverage of the total OMCG population due to the larger sample however, cannot be dismissed as this would require information on the exact year of initiation for each member. Intensified police attention to OMCG members could also have increased the number of convictions for OMCG members, however, given our finding that most of these members were first convicted at an early age, both long before becoming an OMCG member and long before the policy focus on OMCGs, this seems an unlikely substitute account for the current findings.

Adding to prior research, the present study included information on the conviction histories of a still under researched population: members of official OMCG support clubs. Even more clearly than among OMCG members, we see a group of young(er) members. The percentage of convicted support club members is lower than that among OMCG members, and those support club members who do have a criminal record, have on average less and less serious offenses in their conviction histories. The developmental trajectories and their prevalences are however similar for OMCG and support club members. Compared to OMCG members, support club members are less often convicted for offense types indicative of organized crime. One explanation for this could be their relatively young age. Another possibility is that support clubs function to a lesser extent than do OMCGs as offender convergence settings, where the skills, opportunities and or moral climate are supportive for organized types of crime. Rivaling OMCGs also, by way of precautionary expansion, could have designated independent clubs, whose members are less criminally inclined, as official support clubs in order to secure access to their share of potential members. To the extent support clubs have to pay dues to the OMCG they are affiliated to, it could also be that independent clubs, with less criminally inclined memberships, are forced by the OMCG to become their support clubs. In this scenario, annexing smaller clubs could be part of the business model for the larger OMCGs. Future research, based on detailed police file information, is needed to clarify this issue.

Quinn and Forsyth (Citation2011) distinguish between conservative and radical bikers. Conservative bikers are argued to be primarily interested in the masculine surroundings of the clubhouse and biker parties, the ritual induced feelings of kinship among initiated members, and a passion for riding and customizing motorcycles. Radical bikers however, are said to be more orientated toward monetary goals, and therefore more inclined to engage in entrepreneurial types of crime potentially yielding high illegal profits. For radical bikers membership to an OMCG or support club merely constitutes a goal to an end. Especially during times of rapid expansion of the biker subculture, and the intergang conflicts that tend to accompany such growth, radical sentiments may gain the upper hand and make some clubs shift from mere social clubs toward criminal organizations (Barker Citation2007; Quinn Citation2001). Prior Dutch research showed there to be marked differences between Dutch OMCGs, both in terms of the percentage of members with a criminal record, as in terms of the type of offenses members were convicted for (Blokland, Soudijn, and van der Leest. Citation2017). The present study focused on the commonalities and differences in the criminal careers of OMCG and support club members in general. Our findings indicate that OMCG members following criminal career paths that show persistence into the adult years, are most likely of all OMCG members to have been convicted for organized crime type of offenses. Future studies could focus on the extent to which there are differences between different OMCGs, or even different OMCG chapters, in the level in which their members follow these criminal trajectories and engage in serious and organized crime. However, to gain insight in how and the extent to which members engaging in organized crime actually use their OMCG membership as a ‘means to an end’, research tapping different data sources, like police investigation files or interviews with convicted OMCG members, will be necessary.

While the focus of the current analyses was on the criminal careers of members of outlaw motorcycle gangs and their support clubs, it is equally important to stress that one in seven (14.2%) of the OMCG members in our current sample, and one in five (21.8%) members of OMCG support clubs do not have a criminal record whatsoever. Yet, these individuals are labeled as members of outlaw motorcycle gangs, or their support clubs, and as such are subject to the many restrictive policies that constitute the Dutch whole-of-government approach. However, even under the possibly heightened police attention brought upon themselves by their OMCG membership, absence of a criminal record does not equal absence of criminal behavior. Also, if not themselves actively involved in crime, these individuals chose to move in social circles in which the majority of individuals, judged by their officially recorded criminal histories, are active criminals. What makes OMCGs attractive to these individuals, and how they navigate the risks involved in associating with convicted felons and frequenting offender convergence settings, remain questions open to future study.

The present research is subject to the limitations that are common to all criminological research based on official data, and that need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the present findings and drawing subsequent conclusions. As mentioned in the methods section, it is unknown to what extent the present sample is statistically representative of the entire Dutch OMCG and support club membership population. When especially criminally active members are known to the police as ‘bikers’, and therefore are more likely to be included in the sample, our results would overrepresent the criminal careers of OMCG and support club members. The size of the current sample and the results of the sensitivity analysis suggest that this type of bias is unlikely to alter our main conclusion that OMCG members are disproportionally engaged in crime. The differences between the current results and those of prior studies further suggest changes in the Dutch outlaw biker scene that follow from the growth of the number of young(er) members. Given the sampling frame, the results provide merely a snapshot of the Dutch OMCG landscape. Longitudinal research, or repeated cross-sectional sampling, would be needed to gain insight in the ways the OMCG and support club membership population are evolving over time.

To reconstruct the criminal histories of the OMCG and support club members in our sample, abstracts from the General Documentation Files were used. Criminological research based on official records by definition excludes that part of the sample’s criminal behavior of which they are not suspected, arrested, tried, and sentenced. This realization may be especially relevant for the current sample, as prior research showed that OMCG members actively use their membership to pressure victims and witnesses not to contact the police (Blokland and David Citation2016). Official registrations furthermore do not only represent individual behavior, but also the behavior of the judicial system. The current findings therefore result—in part—from the capacity and priorities of the police and the public prosecutor’s office during the observation period. The increased policy attention for outlaw biker crime from 2012 onwards could have resulted in a higher likelihood of prosecution and adjudication given actual criminal behavior. Given the average age of the OMCG and support club members in our sample in 2015 and their average age at the onset and during the early phases of their criminal careers however, much of the conviction histories of the members in our sample stems from years well before 2012.

Finally, it is important to note that the present results do not speak on the effect OMCG or support club membership may or may not have on individual members’ criminal career development. Members’ criminal trajectories analyzed here showed that about one-third of the sample experienced their first conviction at an age at which OMCG or even support club membership is highly unlikely. Apparently, these early onset offenders are at some point attracted to, or recruited for, OMCG membership. While the peak of their conviction history follows the well-known age-crime distribution, the subsequent decline is less outspoken, resulting in a higher than expected level of convictions during most of the adult period. Around 15% of the current sample follows a criminal trajectory that peaks much later than expected, and shows a more gradual decline, resulting in higher than expected levels of convictions during the adult years—the period that one is eligible for OMCG membership—also for this group. Still, 15% of the present sample has no or hardly any criminal history at the time of data collection, whereas conviction levels in the criminal careers of another third of the sample can be considered low, also during the adult years. The age-nonconform levels of criminal involvement among OMCG and support club members therefore could result from either preexisting differences between OMCG and non-OMCG members prior to OMCG membership, the effects of OMCG or support club membership—either directly through its effect on individual behavior, or indirectly through its effect on police actions, or a combination of both. To obtain a reliable estimate of the potential impact of OMCG or support club membership on the course of the individual’s criminal career, data on a suitable comparison group of likewise criminally inclined individuals who do not join and OMCG or support club are pivotal (Blokland, Soudijn, and van der Leest. Citation2017; Klement Citation2016).

Crime among OMCG members is a continuing source of concern for the police in the Netherlands, and elsewhere. The present study corroborates this concern in as far as it pertains to the overrepresentation of OMCG members in officially registered crime. That OMCG members are no choirboys is evident: the large majority of OMCG members in our sample has a criminal record, and a considerable share has convictions for violence, drugs or organized types of crime. These findings extend to members of official OMCG support clubs as well. Besides targeting individual members, the Dutch whole-of-government approach to OMCG crime also targets the OMCG as a collective. OMCGs are argued to constitute safe havens for crime that would encourage or at least facilitate criminal behavior by its members. To bolster this argument, the mere finding that many OMCG members have criminal records however will not suffice (Lauchs, Bain, and Bell Citation2015). Given that the present research also finds that almost half of the sampled OMCG and support club members have had only a limited number of judicial contacts, further differentiation on both the club and the individual level seems warranted, not only to safeguard the effectiveness of the whole-of-government approach, but also its legitimacy.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arjan Blokland

Arjan Blokland is Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Leiden University, The Netherlands and senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR). His research interests include criminal careers and life course criminology, effects of formal interventions, sexual offending, and criminal networks.

Wouter Van Der Leest

Wouter van der Leest is a researcher in the Central Unit of the National Police of the Netherlands. His primary research interests include OMCGs, organized crime and future forms of crime.

Melvin Soudijn

Melvin Soudijn is a senior researcher in the Central Unit of the National Police of the Netherlands and a research fellow of the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR). His primary research interests include (the economics of) organized crime, money laundering, and criminal networks.

Notes

1 See rulings ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2007:BC0685; ECLI:NL:HR2009:BI1124; ECLI:NL:GHSHE;2008:BD0560; ECLI:NL:GHAM:2008:BC9212; ECLI:NL:RBMNE:2017:6241.

2 See Wolf (Citation1991) and Barker (Citation2015) for in-depth descriptions of the lengthy process of becoming an OMCG member, starting from lowly hang-around, to prospect to full-color member.

3 Since the data had to be anonymized due to privacy requirements, and members may have left their OMCG—either in good or bad standing—between 2013 and 2015, at present, we have no way of checking who or how many OMCG members from the prior sample of 601 members (Blokland et al. Citation2019) are also present in the current sample of 1,617 OMCG members. Police experts consulted tell us that especially older members are likely to be included in both samples. Therefore, we may safely assume there is considerable overlap between these samples. The previous sample did not include members of OMCG support clubs.

4 Red Devils MC is now considered a separate OMCG but at the time of sampling was considered a support club.

5 For the present study, ongoing criminal enterprises were defined as extortion, kidnapping, human trafficking, and money laundering. Drug offenses that according to (Quinn and Koch Citation2003) also constitute ongoing criminal enterprises constitute a separate category.

6 Because of the decreasing number of members in our sample actually reaching that age, we choose to report the age-crime curve from ages 12 to 55. This does not mean however, that OMCG and support club members in our sample that were older than 55 in 2015 did not commit any crimes after that age.

7 LOESS or LOWESS smoothing is a nonparametric technique that can be used to clarify the relationship between variables (Cleveland and Devlin Citation1988).

8 An OMCG member aged 42 in 2015, who was convicted nine times and experienced multiple incarceration spells with a total length of 3 years in the 30 years between ages 12 and 42, thus has an average number of conviction per time free of 9/(30–3) = 0.33.

9 Results for the separate OMCG and support group models were substantively similar to the model estimated on the entire sample.

10 The slight increase in the average yearly number of convictions at the end of the observation period appears to be an artifact of the use of quadratic curves to estimate the trajectories. Observed values in this age period show an irregular pattern.

References

- Barker, Thomas. 2007. Bikers Gangs and Organized Crime. Newark, NJ: Anderson Publishing.

- Barker, Thomas. 2012. North American Criminal Gangs: Street, Prison, Outlaw Motorcycle, and Drug Trafficking Organizations. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Barker, Thomas. 2015. Biker Gangs and Transnational Organized Crime, Second Edition. Newark, NJ: Anderson Publishing.

- Barrows, Julie and C. Ronald Huff. 2009. “Constructing and Deconstructing Gang Databases.” Criminology & Public Policy 8 (4):675–703. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00585.x.

- Bernasco, Wim and Wouter Steenbeek. 2017. “More Places than Crimes: Implications for Evaluating the Law of Crime Concentration at Place.” Journal Quantitative Criminology 33 (3):451–67. doi:10.1007/s10940-016-9324-7.

- Blokland, Arjan. 2005. Crime over the Life Span; Trajectories of Criminal Behavior in Dutch Offenders. Leiden: Leiden University.

- Blokland, Arjan, Melvin Soudijn, and Wouter van der Leest. 2017. “Outlaw Bikers in the Netherlands: Clubs, Social Criminal Organizations, or Gangs.” Pp. 91–114 in Understanding the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs: International Perspectives, edited by Andy Bain and Mark Lauchs. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press,

- Blokland, Arjan and Jeanot David. 2016. “Outlawbikers Voor De Rechter: Een Analyse Van Rechterlijke Uitspraken in De Periode 1999–2015.” Tijdschrift Voor Criminologie 58 (3):42–64. doi: 10.5553/TvC/0165182X2016058003003

- Blokland, Arjan, Lonneke van Hout, Wouter van der Leest, and Melvin Soudijn. 2019. “Not Your Average Biker; Criminal Careers of Members of Dutch Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs.” Trends in Organized Crime 22 (1):10–33. doi:10.1007/s12117-017-9303-x.

- Blokland, Arjan, Melvin Soudijn, and Eric Teng. 2014. “‘Wij Zijn Geen Padvinders’: Een Verkennend Onderzoek Naar De Criminele Carrières Van 1%-Motorclubs.” Tijdschrift Voor Criminologie 56 (3):3–28. doi: 10.5553/TvC/0165182X2014056003001

- Blumstein, Alfred, Jacqueline Cohen, Jeffrey D. Roth, and Christy A. Visher. 1986. Criminal Careers and “Career Criminals”: Vol. 1 Report of the Panel on Criminal Careers. Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press.

- Burgwal, Leo. 2012. Hells Angels in De Lage Landen. Amsterdam: Just Publishers.

- Cleveland, William .S. and Susan J. Devlin. 1988. “Locally Weighted Regression: An Approach to Regression Analysis by Local Fitting.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 83 (403):596–610. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478639

- Farrington, David P. 1986. “Age and Crime.” Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 7:189–250. doi: 10.1086/449114

- Fijnaut, Cyrille and Frank Bovenkerk. 1996. “Georganiseerde Criminaliteit in Nederland: Een Analyse Van De Situatie in Amsterdam.” Rapport Commissie Van Traa, Deelonderzoek IV, Tweede Kamer, Vergaderjaar 1995–1996, 24 072, nr. 20.

- Fox James, A. and Paul E. Tracy. 1988. “A Measure of Skewness in Offense Distributions.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 4 (3):259–74. doi:10.1007/BF01072453.

- Houghton, Des. 2014. “Queensland’s Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Members are Overwhelming Criminals with Serious Convictions.” The Courier Mail, May 2nd, 2014. Retrieved May 7th 2019 http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/queenslands-outlaw-motorcycle-gang-members-are-overwhelming-criminals-with-serious-convictions/story-fnihsrf2-1226903844876

- Klement, Christian. 2016. “Outlaw Biker Affiliations and Criminal Involvement.” European Journal of Criminology 13 (4):453–72. doi:10.1177/1477370815626460.

- Lauchs, Mark. 2019. “Are Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Organized Crime Groups? an Analysis of the Finks MC.” Deviant Behavior 40 (3):287–300. doi:10.1080/01639625.2017.1421128.

- Lauchs, Mark, Andy Bain, and Peter Bell. 2015. Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. A Theoretical Perspective. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- LIEC. 2016. Brief Aan De Minister Van Veiligheid En Justitie over De Voortgang Integrale Aanpak Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. The Hague: LIEC.

- LIEC. 2017. Voortgangsrapportage Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs 2016. The Hague: LIEC.

- LIEC. 2018. Voortgangsrapportage Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs 2017. The Hague: LIEC.

- Nagin, Daniel S. 2005. Group-Based Modeling of Development over the Life Course. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nagin, Daniel S. and Kenneth C. Land. 1993. “Age, Criminal Careers and Population Heterogeneity: Specification and Estimation of a Nonparametric, Mixed, Poisson Model.” Criminology 31 (3):327–62. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1993.tb01133.x.

- National Police. 2014. Outlaw Bikers in Nederland. Woerden: DLIO.

- Piquero, Alex R. 2008. “Taking Stock of Developmental Trajectories of Criminal Activity over the Life Course.” Pp. 23–78 in The Long View of Crime. A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research, edited by Akiva M. Liberman. New York: Springer,

- Piquero, Alex R., David P. Farrington, and Alfred Blumstein. 2003. “The Criminal Career Paradigm.” Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 30:359–506. doi:10.1086/652234.

- Quinn, James F. 2001. “Angels, Bandidos, Outlaws and Pagans: The Evolution of Organized Crime among the Big Four 1% Motorcycle Clubs.” Deviant Behavior 22 (4):379–99. doi:10.1080/016396201750267870.

- Quinn, James F. and Craig J. Forsyth. 2011. “The Tools, Tactics, and Mentality of Outlaw Biker Wars.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 36 (3):216–30. doi:10.1007/s12103-011-9107-5.

- Quinn, James. 2003. “The Nature Of Criminality Within One-percent Motorcycle Clubs.” Deviant Behavior 24 (3):281–305. doi:10.1080/01639620390117291.

- RIEC-LIEC. 2014. Integrale Landelijke Voortgangsrapportage Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (OMG’s). Den Haag: Landelijk Informatie en Expertise Centrum.

- Rostami, Amir and Hernan Mondani. 2019. “Organizing on Two Wheels: Uncovering the Organizational Patterns of Hells Angels MC in Sweden.” Trends in Organized Crime 22 (1):34–50. doi:10.1007/s12117-017-9310-y.

- Schutten, Henk, Paul Vugts, and Bart Middelburg. 2004. Hells Angels; Motorclub of Misdaadbende? Utrecht: Monitor Publishing.

- Secretariaat Generaal Benelux Unie. 2016. Tackling Crime Together. The Benelux and North Rhine-Westphalia Initiative on the Administrative Approach to Crime Related to Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs in the Euregion Meuse-Rhine. Brussels: Benelux.

- Smith, Robert C. 2002. “Dangerous Motorcycle Gangs: A Facet of Organized Crime in the Mid-Atlantic Region.” Journal of Gang Research 9 (4):33–44.

- Thomas, Barker. 2017. “Motorcycle Clubs or Criminal Gangs on Wheels?” Pp. 3–27 in Understanding the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs: International Perspectives, edited by Andy Bain and Mark Lauchs. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press,

- Tremblay, Pierre., Sylvie Laisne, Gilbert Cordeau, Angela Shewshuck, and MacLean. Brian. 1989. “Carrières Criminelles Collectives: Évolution D’une Population Délinquante (Les Groups De Motards).” Criminologie 22 (2):65–94. doi:10.7202/017282ar.

- Van Koppen, M. Vere, Christianne J. de Poot, Edward R. Kleemans, and Paul Nieuwbeerta. 2010. “Criminal Trajectories in Organized Crime.” British Journal of Criminology 50 (1):102–23. doi:10.1093/bjc/azp067.

- Van Koppen, M. Vere, Christianne J. de Poot, and Arjan A.J. Blokland. 2010. “Comparing Criminal Careers of Organized Crime Offenders and General Offenders.” European Journal of Criminology 7 (5):356–74. doi:10.1177/1477370810373730.

- Van Ruitenburg, Teun. 2016. “Raising Barriers to ‘Outlaw Motorcycle Gang-Related Events’ Underlining the Difference between Pre-Emption and Prevention.” Erasmus Law Review 3:122–34. doi:10.5553/ELR.000072.

- Wolf, Daniel R. 1991. The Rebels: A Brotherhood of Outlaw Bikers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.