Abstract

Introduction: This study used extended theory of planned behavior (extended TPB) to understand the underlying factors related to help-seeking behavior for sexual problems among Iranian women with heart failure (HF).

Methods: We recruited 758 women (mean age = 61.21 ± 8.92) with HF at three university-affiliated heart centers in Iran. Attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, self-stigma of seeking help, perceived barriers, frequency of planning, help-seeking behavior, and sexual function were assessed at baseline. Sexual function was assessed again after 18 months. Structural equation modeling was used to explain change in sexual functioning after 18 months.

Results: Attitude and perceived behavioral control were positively correlated to behavioral intention. Behavioral intention was negatively and self-stigma in seeking help was positively correlated to perceived barriers. Behavioral intention was positively and self-stigma in seeking help was negatively correlated to frequency of planning. Perceived behavioral control, behavior intention, and frequency of planning were positively and self-stigma in seeking help and perceived barriers were negatively correlated to help-seeking behavior. Help-seeking behavior was positive correlated to the change of FSFI latent score.

Conclusions: The extended TPB could be used by healthcare professionals to design an appropriate program to treat sexual dysfunction in women with HF.

Introduction

Given the high prevalence of heart failure (HF) worldwide (∼1%–2% of the adult population in developed countries, rising to ≥10% among people >70 years of age) [Citation1], healthcare professionals should not ignore the profoundly negative impacts of this complex syndrome. Although 60%–87% of patients with HF report sexual problems [Citation2], healthcare professionals seldom address sex issues with their patients [Citation3,Citation4]. By definition, HF restricts itself to stages at which clinical symptoms are apparent [Citation1], and symptoms of HF affect the sexual relationships of patients with HF [Citation5]. One of the negative impacts in HF is sexual dysfunction that contributes to the impairment of the patients’ quality of life [Citation6,Citation7]. Most patients attribute their sexual problems to their HF; however, the mechanism behind sexual problems is complex and sexual problems can be related to various demographic, physiological/clinical, and treatment related factors [Citation8]. It is known that women with HF have more sexual problems than women in the general population [Citation9]. Although men may have sexual dysfunction, women experience different types of sexual dysfunction, such as decline in sexual arousal or painful sexual intercourse [Citation9]. In a recent study [Citation10], men with HF were more likely to report problems with sexual function, but both genders were similarly highly bothered by the problem. Therefore, assessing for sexual dysfunction in women with HF is an important issue for healthcare professionals to address [Citation11].

Unfortunately, women in general are highly unlikely to disclose their sexual dysfunction to any healthcare professional and decline to seek help. An online survey reported that among 3807 healthy volunteers, 40% of women had sexual problems, but did not consult any clinician [Citation12]. Another recent study showed that women (37.9%; 25 out of 66) as compared with men (62.4%; 154 out of 247) were less likely to report sexual dysfunction [Citation10]. Moreover, a multinational study revealed that only 18.8% of women with a sexual problem had sought medical care, and 9% sought help in the last 3 years [Citation13]. Moreover, those with HF who had severe sexual dysfunction, regardless of gender, had shorter survival than those who had minor or moderate sexual dysfunction [Citation14]. Hence, not seeking help for sexual dysfunction makes it more difficult for healthcare professionals to address sexual problems.

Both the American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have published guiding documents [Citation2,Citation15] to direct clinicians treating sexual dysfunction in patients with HF. Additionally, the application of treatment guidelines could be benefited by adding motivating help-seeking intention and activating help-seeking behaviors for women with HF who have sexual dysfunction. To improve help-seeking behavior in sexual dysfunction among women with HF, a psychopathology framework would improve knowledge about sexual problems. This is of great importance as such knowledge may be used for further development of theoretically based interventions for women with HF based on motivating help-seeking intention and activating help-seeking behaviors. That is, in order to understand the underlying reasons for difficulties in help-seeking behaviors among women with HF in a more comprehensive and structured way, examining factors affecting help-seeking behaviors using a well-established behavioral theory is needed.

Theory of planned behavior (TPB) could be used to identify factors affecting sexual dysfunction rather than sexual needs. The TPB developed by Ajzen [Citation16] includes four main factors (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention) and a final behavior (in our study, help-seeking behavior for the sexual problem). However, Ajzen [Citation17] and other researchers [Citation18,Citation19] recently noted that the TPB could be improved by incorporating other domains known or hypothesized to play an important role. Therefore, they proposed to use an extended TPB (i.e. original TPB factors plus other important factors in a specific behavior) to replace the original TPB. In the framework of explaining help-seeking behavior of sexual problems, we incorporated three additional factors: perceived barriers, self-stigma in seeking help, and frequency of planning.

The original TPB proposes that attitude (e.g. judgment of seeking help in sexual dysfunction), subjective norm (e.g. perceived opinions from the environment on seeking help in sexual dysfunction), and perceived behavioral control (e.g. the power of control on performing help-seeking) together explain an individual’s behavioral intention; behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control further interpret the individual’s final behavior (e.g. seeking help in sexual dysfunction) [Citation16,Citation20]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have applied TPB to understand help-seeking behaviors for sexual problems among women with HF. In addition, perceived barriers, self-stigma in seeking help, and frequency of planning were included in the extended TPB, because perceived barriers and self-stigma influenced the help-seeking behaviors for sexual dysfunction in women with epilepsy in one study [Citation21]. Also, planning was found to be a significant mediator between behavioral intention and real behavior among people who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery [Citation22].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of an extended TPB to explain help-seeking intention and help-seeking behaviors that contribute to change in sexual function in Iranian women with HF.

Methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences and conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Helsinki declaration [Citation23].

Participants and procedure

Between February 2015 and October 2017, female patients with HF were recruited from three university-affiliated heart centers in Tehran and Qazvin. Inclusion criteria were: objectively verified diagnosis of HF, being married or having a partner, any kind of sexual problem and signing informed consent. Patients with pregnancy, lactating, insufficient language skills in Persian and insufficient cognitive skills to answer to the questionnaires were excluded from the study. Three cardiologists assessed patients in terms of eligibility for this study. Of the 1083 approached patients with HF, 166 (15.3%) patients were not eligible, and 159 (14.7%) patients did not agree to participate in the study. We estimated the sample size using the following setting: degrees of freedom at 83; type I error at 0.001, power at 0.95; null root mean square error of approximation at 0.05; and alternative root mean square error of approximation at 0. The estimated sample size was ∼405; thus, we believe that our sample size was sufficient to detect the significance.

Instruments

Questionnaire for TPB [Citation21], Self-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) [Citation24], Perceived barriers [Citation21], Frequency of planning, Help-seeking behavior, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation25,Citation26], and Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [Citation27–29] were measured at baseline. The FSFI was administered again 18 months later.

Questionnaire for theory of planned behavior (TPB)

A Persian questionnaire with 16 items according to Lin et al. [Citation21] was adapted to a HF context to capture the four TPB constructs. Seven items using different adjectives (bad-fine; negative-positive; undesirable-desirable; unimportant-important; useless-useful; disagreeable-agreeable; embarrassing-unshameful) with the same item stem (For me to seek sexual health service is) were used to assess attitude toward help-seeking. Three items were used to assess subjective norms (sample item: my husband/partner think that I should seek sexual health service); three items to assess perceived behavioral control (sample item: seeking sexual health service is dependent on my choice); three items to assess behavioral intention (sample item: I intend to seek sexual health service). All the items were measured on a five-point Likert type scale (1–5), and a higher score represented higher levels of attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention. The Cronbach’s α was between 0.86 and 0.90 in Lin et al. [Citation21]; between 0.78 and 0.91 in this current study.

Self-stigma of seeking help

The 10-item Self-Stigma of Seeking Help Scale (SSOSH) [Citation24] was used to assess the self-stigma of seeking help in sexual dysfunction. All items (sample item: would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help) were rated on a 5-point Likert type scale (1–5), and a higher score indicated higher level of self-stigma. Moreover, the Persian version of the SSOSH has been validated with satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.89) [Citation24]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.83 in the current study.

Perceived barriers

The perceived barriers were measured using six items (sample item: I don’t know where to seek sexual health service) [Citation21]. All items, adapted to a HF context, were rated on a 5-point Likert type scale (1–5), and a higher score indicated higher level of perceived barriers to help-seeking. The Cronbach’s α was 0.82 in the previous study [Citation21]; and 0.80 in the current study.

Frequency of planning

The frequency of planning was measured using four items. Patients were asked to respond to the stem “I have made a detailed plan regarding…” on a 5-point scale (1–5): (a) “when to seek help”, (b) “where to seek help”, (c) “how to seek help”, and (d) “how much time to spend on seeking help”. Internal reliability was satisfactory in this current study (α = 0.91).

Help-seeking behavior

Information on help-seeking behavior for a sexual problem was obtained by accessing the patient’s clinical records over 18 months. The help-seeking behavior was defined as the actual visits to psychologists, psychiatrists, gynecologists, or general practitioners for the sexual problem.

Anxiety and depression

The 14-item hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) contains two domains (seven items for anxiety and seven items for depression), and each item has four labeled response categories ranging between 0 and 3. A higher score in HADS indicated a higher level of anxiety or depression [Citation25]. Moreover, the Persian version of the HADS has been validated with satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.79 and 0.82) [Citation26]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.86 for anxiety and 0.88 for depression in the current study.

Sexual functioning in female

The 19-item female sexual function index (FSFI) is one of the most commonly used instruments to assess women’s sexual functioning [Citation27,Citation28]. The FSFI contains six domains, including sexual desire (two items), arousal (four items), lubrication (four items), orgasm (three items), satisfaction (three items), and pain (three items). All items were rated using a 5-point Likert type scale (1–5), except for four items (two in the desire and two in the satisfaction domains) rated on a 6-point Likert type scale (1–6). The Persian version of the FSFI has been validated with satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.72 to 0.90) [Citation29], and a higher score represented better sexual functioning. The Cronbach’s α was between 0.76 and 0.91 in the current study.

Data analysis

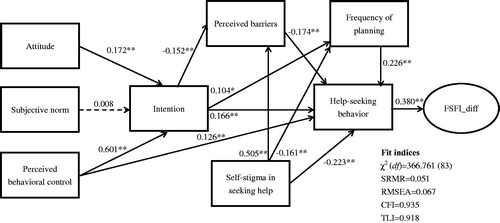

We proposed a model based on the extended TPB to examine its ability to explain the change of female sexual function in 18 months () using structural equation modeling (SEM). In the proposed model, the change of female sexual function was a latent construct composed by the changed scores of the FSFI domains (i.e. the 18-month follow-up domain scores minus the baseline domain scores). All other constructs were observed variables in the baseline. We proposed that behavioral intention was predicted by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control; both frequency of planning and perceived barriers were explained by behavioral intention and self-stigma in seeking help; help-seeking behavior was predicted by perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, frequency of planning, perceived barriers, and self-stigma in seeking help; change of female sexual function was explained by the help-seeking behavior. We further investigated whether frequency of planning and perceived barriers were mediators in the association of behavioral intention and help-seeking behavior; and whether help-seeking behaviors was a mediator in the association of behavioral intention and change of female sexual function.

Figure 1. Using extended theory of planned behavior to explain the help-seeking behavior in sexual problem and the sexual function. FSFI_diff: FSFI follow-up latent score minus FSFI baseline latent score; FSFI: female sexual function index; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; CFI: comparative fit index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis index. Age, NYHA, and BMI were controlled in the model. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant relationship; solid lines indicate significant relationship. *p < .05; **p < .01

The SEM was estimated using maximum likelihood method, and the missing values were imputed using full information maximum likelihood. We additionally used standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.08), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.9), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > 0.9) to determine whether the proposed model is supported or not [Citation30,Citation31]. In terms of the mediated effects, they were examined using Sobel test [Citation32].

All the analyses were done using the R software and the lavaan package [Citation33] in the R software was used for the SEM (including the mediated effects).

Results

shows the descriptive statistics of studied variables, including participant characteristics. The SEM results supported our hypothesized model as indicated by the satisfactory fit indices (). All the path coefficients were significant and in anticipation, except for the path from subjective norm to behavioral intention ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 758).

Frequency of planning (β = 0.024; p = .016) and perceived barriers (β = 0.026; p = .001) were significant mediators in the relationship between behavioral intention and help-seeking behavior. Moreover, help-seeking behavior was a significant mediator (β = 0.063; p < .001) in the relationship between behavioral intention and the change of FSFI latent score ().

Table 2. Mediated effects of frequency of planning, perceived barriers, and help-seek behavior.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine whether the extended TPB can efficiently predict help-seeking in sexual dysfunction among women with HF, and whether the model can further predict the change of female sexual functions. Our findings were based on three components (use of SEM, a longitudinal design, and a large sample with an N of 758), that strongly supported our proposed extended TPB.

Even though no studies of people with HF examined the use of TPB with sexual dysfunction, our significant findings are in line with other TPB-related studies across different populations [Citation21,Citation22]. Because no studies have applied TPB to women with HF to investigate their help-seeking behaviors in sexual dysfunction, we further compared our findings to another study using TPB of women with epilepsy [Citation21], in which the study design also included self-stigma in help-seeking and perceived barriers. Similar to our findings, Lin et al. [Citation21] demonstrated that self-stigma and perceived barriers were two significant obstacles for women to increase their help-seeking intention. However, Lin et al. [Citation21] found that subjective norm was associated with intention, which is inconsistent to our nonsignificant finding.

The nonsignificant path between subjective norm and behavioral intention found in the present study contradicts the original one proposed in the TPB [Citation16]. Nevertheless, our results somewhat correspond to empirical evidence: two reviews concluded that subjective norm is relatively weakly associated with intention and behavior [Citation34,Citation35]; two studies demonstrated that subjective norm was not correlated with behavioral intention in people with epilepsy and their healthcare providers [Citation30,Citation36]. A possible reason for the nonsignificant path between subjective norm and behavioral intention is because that behavioral intention was strongly correlated with attitude and perceived behavioral control [Citation21,Citation36]. In addition, our results showed that attitude and perceived behavioral control were relatively higher than the subjective norm; therefore, our patients might generally feel positively about their help-seeking behaviors and feel control over taking it. The positive beliefs might subsequently decrease the association between subjective norm and behavioral intention [Citation37–39]. Given that the effectiveness of intervention using TPB on sexual function and reproductive health has been well documented in Iranian people [Citation40–42], future studies may want to further explore whether the application of TPB also works on women with HF.

As the AHA and ESC have explicitly stated the importance of caring for sexual dysfunction for people with HF [Citation2,Citation15], we believe that our study results provide clinicians with valuable information to design appropriate interventions. Specifically, in addition to the guidelines recommended by the AHA and ESC, healthcare professionals should consider how to increase the willingness of help-seeking behaviors in women with HF. Communication between the individual patient and the healthcare professional should in this case be done in an open, friendly, patient-centered manner. The willingness and real action in seeking help are important, because a key element for successful treatment is patients’ motivation [Citation43]. However, changing clinical routines for professionals, as well as clinical habits in patients are difficult [Citation44], especially around sexual problems, since there are different types of barriers and self-stigma to handle for both healthcare professionals and patients [Citation2,Citation15]. Healthcare professionals might in this case have a sort of “responsibility” to initiate this help-seeking talk, since sexual problems can be perceived as sensitive [Citation45]. Specifically, it would be interesting if future studies investigate whether using contraception is acceptable for women with HF. Although empirical evidence is scarce in terms of the use of contraception among women with HF [Citation46], current literature has indicated that the use of contraceptives may affect quality of life and sexual function [Citation47,Citation48]. Thus, healthcare providers may want to remind women with HF to be cautious in using contraception.

Apart from women with HF, recent literature indicates that other diseases such as cystocele and urinary incontinence also impact sexual function and subsequently quality of life among patients [Citation49,Citation50]. Given that quality of life is an important health outcome [Citation51,Citation52], the importance of help-seeking behaviors on sexual dysfunction is not restricted in women with HF, and healthcare providers should pay special attention to all patients who could be at risk for sexual dysfunction.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the large sample size (n = 758) with an 18-month follow-up. The use of appropriate theory with standardized and robust measures is another strength of this study. Our results were derived from women with HF only and cannot be generalized to male patients. Given that sexual dysfunction also exists in males with HF, which is a critically clinical problem [Citation11], future studies may want to investigate whether our extended TPB model can also be applied to men. Second, we did not provide any interventions based on the extended TPB model; thus, we were unable to claim that the extended TPB model is effective in enhancing sexual function for women with HF. However, our results demonstrated that the extended TPB model predicted the change of their sexual function; we believed that it could be used for treatment. Third, our results were from an Iranian sample, and the generalizability might not be extended to western populations given the cultural differences. For example, the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control might be different between the East and West cultures.

Given that our study only provides quantitative information in help-seeking behaviors, future research may want to use in-depth qualitative interviews to understand the processes involved in help-seeking behaviors. Thus, healthcare providers will have different dimensions to assist and interpret help-seeking behaviors among women with HF.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200.

- Levine GN, Steinke EE, Bakaeen FG, et al. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1058–1072.

- Byrne M, Doherty S, Murphy AW, et al. Communicating about sexual concerns within cardiac health services: do service providers and service users agree? Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:398–403.

- Kolbe N, Kugler C, Schnepp W, et al. Sexual counseling in patients with heart failure: a silent phenomenon: results from a convergent parallel mixed method study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:53–61.

- Jaarsma T. Sexual problems in heart failure patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;1:61–67.

- Apostolo A, Vignati C, Brusoni D, et al. Erectile dysfunction in heart failure: correlation with severity, exercise performance, comorbidities, and heart failure treatment. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2795–2805.

- Hoekstra T, Jaarsma T, Sanderman R, et al. Perceived sexual difficulties and associated factors in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163:246–251.

- Jaarsma T. Sexual function of patients with heart failure: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2017;4:3–7.

- Schwarz ER, Kapur V, Bionat S, et al. The prevalence and clinical relevance of sexual dysfunction in women and men with chronic heart failure. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:85–91.

- Fischer S, Bekelman D. Gender differences in sexual interest or activity among adults with symptomatic heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:890–894.

- Jaarsma T, Fridlund B, Mårtensson J. Sexual dysfunction in heart failure patients. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11:330–336.

- Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: what gynecologists need to know about the female patient's experience. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:572–576.

- Moreira ED, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6–16.

- Wong HT, Clark AL. Impact of reported sexual dysfunction on outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;170:e48–e50.

- Steinke EE, Jaarsma T, Barnason SA, et al. Sexual counselling for individuals with cardiovascular disease and their partners: a consensus document from the American Heart Association and the ESC Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3217–3235.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: a commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:131–137.

- Conner M. Extending not retiring the theory of planned behaviour: a commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:141–145.

- Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review and avenues for further research. J Appl Social Pyschol. 1998;28:1429–1464.

- Pakpour AH, Zeidi IM, Chatzisarantis N, et al. Effects of action planning and coping planning within the theory of planned behaviour: a physical activity study of patients undergoing haemodialysis. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12:609–614.

- Lin CY, Oveisi S, Burri A, et al. Theory of planned behavior including self-stigma and perceived barriers explain help-seeking behavior for sexual problems in Iranian women suffering from epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;68:123–128.

- Pakpour AH, Gellert P, Asefzadeh S, et al. Intention and planning predicting medication adherence following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:287–295.

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki 2000 [updated 2000 Oct 7; cited 2018 Aug 27]. Available from https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/doh-oct2000/

- Soheilian SS, Inman AG. Middle Eastern Americans: the effects of stigma on attitudes toward counseling. J Muslim Ment Health 2009;4:139–158.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH. Using hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) on patients with epilepsy: Confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch models. Seizure 2017;45:42–46.

- Lin C-Y, Burri A, Pakpour AH, et al. Female sexual function mediates the effects of medication adherence on quality of life in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;67:60–65.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208.

- Fakhri A, Pakpour AH, Burri A, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index: translation and validation of an Iranian version. J Sex Med. 2012;9:514–523.

- Lin C-Y, Fung XCC, Nikoobakht M, et al. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior incorporated with perceived barriers to explore sexual counseling services delivered by healthcare professionals in individuals suffering from epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;74:124–129.

- Lin C-Y, Saffari M, Koenig HG, et al. Effects of religiosity and religious coping on medication adherence and quality of life among people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;78:45–51.

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington (DC): American Sociological Association; 1982. p. 290–312.

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36.

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:471–499.

- Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NLD, Biddle SJH. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2002;24:3–32.

- Lin C-Y, Updegraff JA, Pakpour AH. The relationship between the theory of planned behavior and medication adherence in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;61:231–236.

- Chapman SC, Horne R, Chater A, et al. Patients’ perspectives on antiepileptic medication: relationships between beliefs about medicines and adherence among patients with epilepsy in UK primary care. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;31:312–320.

- Stefan H. Improving the effectiveness of drugs in epilepsy through concordance. Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil. 2009;8:15–18.

- Damghanian M, Alijanzadeh M. Theory of planned behavior, self-stigma, and perceived barriers explains the behavior of seeking mental health services for people at risk of affective disorders. Soc Health Behav. 2018;1:54–61.

- Darabi F, Yaseri M, Kaveh MH, et al. The effect of a theory of planned behavior-based educational intervention on sexual and reproductive health in iranian adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. J Res Health Sci. 2017;17:e00400.

- Jalambadani Z, Garmaroudi G, Tavousi M. Education based on theory of planned behavior over sexual function of women with breast cancer in Iran. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2018;5:201–207.

- Jalambadani Z, Garmaroodi G, Yaseri M, et al. Education based on theory of planned behavior over sexual function of menopausal women in Iran. J Midlife Health . 2017;8:124–129.

- Medalia A, Saperstein A. The role of motivation for treatment success. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:S122–S128.

- Nilsen P, Roback K, Broström A, et al. Creatures of habit: accounting for the role of habit in implementation research on clinical behaviour change. Implement Sci. 2012;7:53.

- Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

- Sedlak T, Bairey Merz CN, Shufelt C, et al. Contraception in patients with heart failure. Circulation 2012;126:1396–1400.

- Caruso S, Cianci S, Malandrino C, et al. Quality of sexual life of women using the contraceptive vaginal ring in extended cycles: preliminary report. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2014;19:307–314.

- Caruso S, Cianci S, Vitale SG, et al. Sexual function and quality of life of women adopting the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 13.5 mg) after abortion for unintended pregnancy. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2018;23:24–31.

- Caruso S, Brescia R, Matarazzo MG, et al. Effects of urinary incontinence subtypes on women's sexual function and quality of life. Urology 2017;108:59–64.

- Vitale SG, Caruso S, Rapisarda AM, et al. Biocompatible porcine dermis graft to treat severe cystocele: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:125–131.

- Fung XC. Child–parent agreement on quality of life of overweight children: discrepancies between raters. Soc Health Behav. 2018;1:37–41.

- Lin CY. Comparing quality of life instruments: sizing them up versus pediatric quality of life inventory and kid-KINDL. Soc Health Behav. 2018;1:42–47.