ABSTRACT

Inter-organisational partnering is seen as an effective mechanism for improving the delivery of chronic disease interventions in communities. Yet even in communities where organisations across multiple sectors are well connected and collaborative in other ways, when it comes to partnering for joint-funding, multiple barriers inhibit the establishment of formal partnerships. To understand why this is so, we examined quantitative and qualitative data from organisations in an Australian community and compared the findings with a review of the published literature in this area. We found that even organisations which are well connected through informal network arrangements face pressure from funding bodies to form more formalised inter-organisational partnerships. Community based organisations also recognise that partnerships are desirable mechanisms for service improvement; however, barriers to joint-funding partnerships exist which include restrictions imposed by funding bodies on the way grants are designed, implemented, and administered. Additional barriers at the community level include organisational capacity for partnership work, intra-organisational restrictions and timing issues. Policy makers must recognise and address the barriers to partnerships which exist within funding structures and at the community level in order to increase partnering opportunities to improve service delivery.

Introduction

Escalating obesity rates and the concomitant rise in chronic disease are significant public health issues in Australia (AIHW, Citation2016) and around the world (WHO, Citation2014). Much work is being done at a community level to address these issues; however, there is a perception that this work is often fragmented, siloed and uncoordinated, despite the turn to collaborative practice to address complex problems (Silvia, Citation2018; Wilkins, Phillimore, & Gilchrist, Citation2015). Unlike the primary and acute health-care system which offers nationally based, universal coverage for citizens, the preventative health system in Australia has been largely reliant on dispersed efforts at state and local levels. Such efforts aim to address complex problems in population-level issues such as obesity, driven by factors that include adequate physical activity, healthy nutrition, alcohol use and tobacco control. One way to address this disconnection of efforts is through the establishment of inter-organisational partnerships, which bring together a range of stakeholders to improve the effectiveness of service delivery at a local level. Built on the idea that no organisation or sector is solely responsible for prevention, interorganisational networks can access and harness a wide variety of resources and skills (Willis, Riley, Taylor, & Best, Citation2014) and reduce exposure to the risk of non-delivery (Silvia, Citation2018). In addition, networks are increasingly relied on to achieve goals which are not attainable either by individual organisations, or through traditional administrative hierarchies (Hu, Khosa, & Kapucu, Citation2016). This paper reports on an exploration of the role of networks within communities in efforts to address complex problems in chronic disease prevention.

Background

Preventive health measures at both national and state levels are characterised by diffuse governance and lack of portfolio responsibility. This occurs alongside the broader trend in government functions and service provision towards devolution of action and market-oriented delivery of service. At the same time, the rise of wicked or complex problems at community and population level has created a gap in service delivery that may be filled at community level by a plethora of network structures (Isett, Mergel, LeRoux, Mischen, & Rethemeyer, Citation2011). Public Administration research has conceptualised three models of networks which have arisen to meet service-delivery need:

Policy networks, focussed on fulfilling the need for public decision-making;

Collaborative networks, sometimes called implementation networks, focussed on connecting organisations (public, not-for-profit and for-profit) which deliver services in communities, particularly to meet needs in areas of social sectors where problems are “invisible, messy or unpopular” (Leat, Williamson, & Scaife, Citation2017);

Governance networks, which “fuse collaborative public goods and service provision with collective policymaking” (Isett et al., Citation2011).

Most of the research into networks for administrative purposes has focussed on the first and third of these, examining the policy contexts in which networks emerge or are created as well as the effects of networked governance. Less attention has been paid to the collaborative network space, in part because of the very nature of many of these networks, which may be self-organising, informal and occur in sectors like preventative health which lack clear lines of administrative oversight. There is a gap in the literature around the differing roles that networks can play in addressing issues where strategic oversight is weak or diffuse. We investigate what this means for self-organising networks that want to increase opportunities to attract funding and external resources, especially in the context of complexity. Existing research seems to suggest that informal networks are likely to move to more formal structures over time (Isett et al., Citation2011). We therefore consider the tension which seems to exist in chronic disease prevention networks between high functioning informal networks and the requirements of formalising for higher level activities such as applying for joint funding. This tension cuts across both the network itself, as well as interactions between the network members and those granting and funding bodies with administrative responsibility.

Existing research in this space draws from seminal work in Resource Dependency Theory (RDT) (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978), and has used RDT to explain the relationships between networked organisations and the way in which “‘social structural resources’ that arise from network configurations are deployed by actors in these networks” (Lee, Rethemeyer, & Park, Citation2018, p. 389). The authors add that insufficient attention has yet been paid to the differing funding contexts within which these networks arise and operate (Lee et al., Citation2018), however, there has recently been a recognition that more nuanced attention needs to be paid to the broader resource contexts of networked partnerships, as well as merely the funding arrangements (Hu et al., Citation2016). Resources may take a variety of forms within community or service-delivery contexts. In addition, understanding the effectiveness of network resource use in terms of outcomes is difficult. Traditional measures may not apply to networks where the focus is to on build “strong relationships and achieve intangible outcomes, such as trust and reciprocity; aspects that typically do not belong to the assessment of organizational effectiveness itself.” (Klaster, Wilderom, & Muntslag, Citation2017, p. 677). Short-term results (e.g.: getting funding for a project) may not reflect, or may even come at the cost of, network stability or other network measures (Klaster et al., Citation2017).

It has been suggested that “‘complex networks are not only relatively common, they are likely to increase in number and importance’ because of the presence of ‘wicked problems’ (those that are non-decomposable and thus require coordination between many actors and many sectors), the outsourcing of government services to private and not-for-profit entities, and the comparative advantage of network approaches to management” (Lecy, Mergel, & Schmitz, Citation2014, p. 645). Moreover, it has been proposed that because formal networks are more likely to be successful in the longer term, participation in informal networks forms an important first step for community organisations (Isett et al., Citation2011).

Current literature also reflects an increasing movement globally towards using grants to promote inter-organisational partnerships, through mandating partnership requirements as part of funding applications (Doerfel, Atouba, & Harris, Citation2017). This movement is born out of the recognition that promoting partnerships between community organisations can decrease duplication of services, increase program coordination and promote large-scale change (Doerfel et al., Citation2017). Yet, these requirements may not in themselves be successful in promoting effective relationships (Doerfel et al., Citation2017). Despite the efforts from grantors to promote community partnerships, many registered groups are simply “partnerships on paper” in order to satisfy funding requirements, rather than fruitful, synergistic relationships between organisations (Filipovic, Citation2013; Kindred & Petrescu, Citation2015). Significant barriers to successful co-funding partnerships exist, both at the level of the grant development as well as at the community level.

Barriers at the level of the grant

With regards to grant level barriers, there are several difficulties that organisations face arising from the way grants are designed, implemented, and administered. Doerfel et al. (Citation2017) discuss the way grant guidelines have requirements that can dictate the types of organising models that are supported, which ultimately affects the nature of the inter-organisational relationships (Doerfel et al., Citation2017). Organisational partnerships often occur in a bottom-up, grassroots fashion as organisations develop alliances based upon their values and connections with each other. The top-down granting model can then undermine the advantages of these partnerships that arise organically due to the imposition of different governing structures onto the existing partnership (Doerfel et al., Citation2017).

Grants can also contain restrictive requirements that create challenges for on-the-ground partners. One case study in Australia showed that funding required visible deliverables for the agenda of the joint initiative, while also needing to align with the agendas of the partners, which sometimes contradicted each other (Del Fabbro, Minniss, Ehrlich, & Kendall, Citation2016). Certain grants can have limiting requirements such as the types of organisations they can fund or partner with (Tan et al., Citation2014). In addition, short funding cycles make it challenging to develop meaningful funding partnerships (Filipovic, Citation2013; Thompson et al., Citation2015). There have been examples in which the partnership had just started to blossom as soon as the funding period terminated. Funders do not usually fund the process of partnership capacity building unless it is aligned with their organisational vision (Corbin, Jones, & Barry, Citation2016). Foundations and not-for-profits, as with government, face increasing pressure to become more “business-like” (Leat et al., Citation2017, p. 128). While “traditional grantmaking is arguably relatively well adapted to the ambiguity, opportunism, and serendipity of foundation work … [it is] ill-adapted to an audit culture.” (Leat et al., Citation2017, p. 130).

Even when partnerships obtain funding, they can face difficulties recruiting, hiring, and training additional staff in order to carry out the tasks for the grant in a short-term period (Chambers et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, similar organisations often apply individually for funding through the same pool of funding. This causes them to view each other as competitors, generating tensions between organisations when working with one another (Del Fabbro et al., Citation2016; Henderson, Kendall, Forday, & Cowan, Citation2013; Willis et al., Citation2014).

Barriers at the level of the organisation

With regards to community-level barriers, organisational capacity is important to supporting the development of more formalised partnerships. It has been shown that key individuals who hold the expertise in grant writing as well as connections of political support for programs have been instrumental in helping partnerships obtain funding (Evenson, Sallis, Handy, Bell, & Brennan, Citation2012; Harper, Kuperminc., Weaver, Emshoff, & Erickson, Citation2014; Jalleh, Anwar-McHenry, Donovan, & Laws, Citation2013). Furthermore, applying for grants in partnership can lead to a great deal of additional administrative tasks for grant writing, evaluation, reporting, and communication, as well as frequent meetings with partners (Filipovic, Citation2013; Jalleh et al., Citation2013; Valaitis, Hanning, & Herrmann, Citation2014). For staff that are already strained with daily service provisional tasks on the job, fostering relationships for funding partnerships with other organisations tends to fall behind on the priority list (Corbin et al., Citation2016; Doerfel et al., Citation2017). This is exacerbated in rural areas in which staff are under-resourced to provide for large service areas and may need to travel long distances to attend meetings or deliver services (Corbin et al., Citation2016).

Funding collaborations generally require a greater level of commitment and capacity than less formal arrangements; as such, not all partnerships within a network will attain the highest levels of collaboration. Organisations with different foci of service delivery (physical activity, nutrition, alcohol and other drug services, disability services) may struggle to align their organisational Key Performance Indicators even when delivering programs with broadly similar health and wellbeing outcomes.

Methods

The study presented here is nested in a larger initiative called Prevention Tracker (http://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/learning-from-local-communities-prevention-tracker-expands/). This initiative is taking a systems approach to understanding the local chronic disease prevention systems in four communities across Australia. In each community, an intensive period of data collection occurs at the beginning of the project to collect and triangulate data from across the prevention system. The project trialled a range of systems tools and methods to identify critical elements of local systems and to co-produce knowledge of prevention efforts which are locally meaningful and useful. Systems-based tools used in communities included social network analysis, qualitative interviews, collection and mapping of secondary health and prevention activities, data synthesis workshops and group model building with community members to create causal loop diagrams. The use of these diverse tools allowed the community and the research team to work together collaboratively to identify a local, systems-level problem in chronic disease prevention which could be unpacked and addressed by locally based action learning teams. Ethical approval to conduct the project was given by University of Sydney [project 2016/418]. This paper draws on multiple data sets from the findings of the project in one community, with a focus on two in particular: the organisational network survey and resultant social network analysis; and the key informant interviews. Similar results were found in the other communities.

Organisational network survey

As part of the Prevention Tracker project, an Inter-Organisational Network Survey (Provan, Fish, & Sydow, Citation2007) was designed to quantify relationships between prevention active organisations in each community. A list of organisations was generated from an inventory of local prevention programs and activities and in consultation with local partners and a Local Advisory Group. Organisations were identified on the basis of being active in preventative health within the community, or as being influential over other players in the prevention system. This approach differs to some others reported in the literature as this is not a self-identified network of organisations that are working together. Rather this is a network of organisations, active in the local prevention system and identified by stakeholders in prevention from within the community who may or may not work with others on prevention activities.

An online survey was conducted in mid-2016. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Harris et al., Citation2009) electronic data capture tools hosted at LaTrobe University in MelbourneFootnote1.

The whole network survey consisted of 17 questions: 8 demographic questions, including 5 related to the organisation, its role, size, and contributions to the health and well-being of the community (PARTNER Tool, Citation2012); 6 questions related to the relationship their organisation had with other organisations across six dimensions: awareness, information sharing, resource sharing, joint planning, joint funding, and informal contact, with the option to nominate whether each relationship was ‘high’ or ‘low’ strength (Milward & Provan, Citation2002; Hawe et al., Citation2004); 3 questions asking for respondents to provide feedback on the survey and the community network in general. The resulting social networks were analysed individually using UCINET 6 (Borgatti, Everett, & Freeman, Citation2002), focusing on structural properties such as density, centrality, average density, and clustering coefficients (Burt, Citation1976; Doreian, Citation1974; Freeman, Citation1979; Watts, Citation1999). A core-periphery analysis was also conducted using a composite of the network across four of the dimensions: sharing information, sharing resources, joint planning and joint funding (Borgatti & Everett, Citation1999; Comrey, Citation1962). Non-respondents were excluded from the core-periphery analysis. Core-periphery analysis divides the members of a network into two classes, based on their relations: the core class is characterised by dense connections among the members of the core, while the peripheral class is characterised by relatively less density in these connections.

Key informant interviews

In addition, face to face, semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted with stakeholders across the prevention system within the community in late 2016. The interview guide focussed on themes such as partnering, leadership, resourcing and workforce issues within prevention. A total of 23 interviews were conducted with 26 individuals, ranging in length from 16 to 67 min. The majority of interviews were between 40 and 65 min long. At least one person was interviewed from each of the organisations which responded to the Organisational Network Survey, while respondents from three organisations which had declined to participate in the online survey, agreed to take part in a face to face interview.

Each interview was audio recorded, transcribed and coded using the NVivo™ software package (QSR, Citation2012). Coded data were thematically analysed using a combination of theoretically informed and inductive coding in an iterative process of higher-level coding and subsequent sub-coding (Saldaña, Citation2016). A sample of interviews was coded by two researchers and compared for consistency. Once agreement was reached in the coding of this sample, one researcher then coded the remaining interviews. High-level codes relevant to the purposes of this paper included: workforce, leadership, language, partnerships, resources, information and evidence and the role of the organisation in prevention.

Results

Organisational network survey

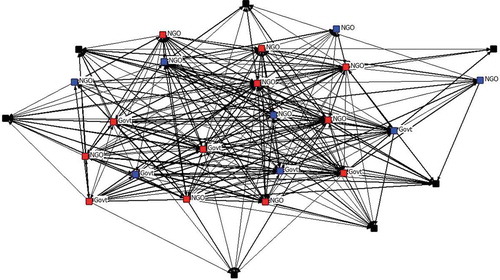

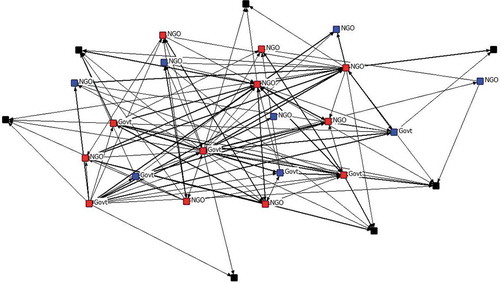

Twenty of the 27 identified organisations participated in the survey, giving a response rate of 74%. Seven of the organisations identified themselves as government bodies, the other 13 were non-government organisations. The seven organisations that did not respond were included in the analysis and coded as ‘non-respondents’. The participating organisations had been present in the community for an average of 28.83 years (median = 21 years); four of the organisations had been present less than 10 years, one organisation was 150 years old. The core-periphery analysis indicated that 60% of the organisations were in the network core, and the ratio of government to non-government organisations was approximately the same in both the core and periphery. is the network of information sharing between organisations, and is the network of joint funding relationships. These diagrams show the relationships between the core (red) and periphery (blue) organisations, and non-respondents (black), with relationships nominated as ‘high’ in thick lines.

The information sharing network has a density of ~49%, which means that almost half of all potential connections are present in this network. This indicates a very high level of information exchange among the participating organisations. The average number of relations (degree) of a member in the network is 12.6. The network is moderately centralised at 0.515, which means that there are some organisations that attract more connections than others. Finally, the undirected network has a diameter of 2, which means that between any pair of organisations there are at most two other organisations on the shortest network path between them. We can expect that information travels quickly through these information channels. The networks for sharing resources and joint planning are progressively less dense, less connected, and more centralised, reflecting the more demanding nature of the relationships. The network of joint funding relations, arguably the most difficult type of relation to maintain, has a density of ~19%, an average degree of 4.9, is highly centralised at 0.837, and a diameter of 5.

The structure of the overall network highlights the strength of relationships between the 12 organisations that form the core. These organisations are closely involved with each other, sharing information, resources, and joint planning. The eight periphery organisations are involved in the same activities, but less closely, and they are more likely to be involved with core organisations than other organisations in the periphery. This suggests that the relationships important to collaborating towards funding are there, and they are strong, but they aren’t being utilised for joint funding arrangements. Finding that the funding network is highly centralised indicates that the organisations are being selective about who they try to engage in joint funding projects with; in this case, it means that two organisations in particular dominate the collaborative funding opportunities. Social Network Analysis doesn’t indicate why that is, but it could relate to those organisations’ size, capacity for administering funds, their past success in winning funds, or whether they are considered more reliable than others. For this reason, qualitative data collected at interview were also examined, to help unpack what barriers might prevent the establishment of more joint funding partnerships in this community.

Key informant interviews

The findings of the interviews revealed that many of the individuals who are active in the local prevention system are well aware of an increasing pressure from administrative bodies for local organisations to partner effectively in order to apply for grants. They were also acutely aware of the difficulties involved in actually doing so. Respondents discussed the importance of informal networks and personal relationships in getting things done locally.

They were aware of the contextual factors which could influence the ability of local organisations to partner, such as the different sectors in which organisations are located. For example, partnerships may be established either between two organisations in a funding relationship (funder/fundee partnership) or two or more organisations partnering to apply for funding. In this case, as one Non-Government Organisation (NGO) employee pointed out: “NGOs … working with [government] departments is a little bit easier because they [government departments] can’t apply for this funding unless it’s in partnership with someone like us”.

However external pressures, such as resources or externally determined indicators can also discourage partnering. Some organisations found it easier to establish partnerships at the worker level than at the management level, because workers are working for the same ends in improving things for the community, whereas management have to meet pre-determined or externally imposed Key Performance Indicators.

It is also clear that in a dynamic, fast-changing environment, time is a critical issue. Time is needed to commit to partnering and to work effectively in building relationships. Small organisations, in particular, struggle to find this time.

I could fill my week with meetings but what would it achieve? Nothing. (participant quote, non-Government agency)

Some respondents were very clear about the different models of partnering between organisations and the degree of both difficulty, but also effectiveness, of improving practice. The following quotation comes from a community workshop held after the key informant interviews, and summarises how different forms of partnering are valued by local stakeholders:

when you talk about engagement, what are we actually looking at? Are we … just talking about networking? Are we talking about cooperating? Are we talking actually collaborating when there’s shared resources, and shared programming … because to my mind that’s where you get the real gains, and that’s where we want to be heading. And I think … there’s a lot of networking. Um, there’s a reasonable degree of cooperating. I think there’s probably not … the collaborating. (participant quote, Group Model Building Workshop, state Govt agency)

Yet despite these pressures, and the competitive environment in which organisations operate, one respondent commented:

Even though they operate in an environment of competitive tendering, you know, they still really communicate quite well. (participant quote, non-Government agency)

But as we have discussed, partnering for information sharing and partnering for funding remain very different propositions:

I think it’s the way both State and Commonwealth Governments are going with funding arrangements. They want to see partnership, partnership, partnership so I think they’re encouraging, the concept, the engagement across organisations. The principle of that is the evidence has increased over recent years. But the actual traction on effective service delivery isn’t quite happening. It has to be created … Actually, to get to that stage you’ve got to look at shared budgets and that’s really tricky. (participant quote, non-Govt agency).

As the quotation above illustrates, for all the goodwill, intentions, communication, and informal sharing which exist locally, partnerships are most likely to founder when financial commitments are brought into the equation.

Discussion

Networks are increasing seen as useful mechanisms for the delivery of services addressing complex social issues in the face of the combined pressures of resource restraint, third party service delivery and competitive funding arrangements. In the context of service delivery in an area such as chronic disease prevention, addressing the huge and growing global burden of poor health through so-called ‘lifestyle-related disease’, in which there is limited strategic oversight and diffuse governance, self-organising networks may struggle to translate local collaboration into higher level action.

Current evidence suggests that despite pressure to improve collaborative practice in public service delivery, well-recognised problems continue to hamper implementation (Wilkins et al., Citation2015). Network analysis in this project demonstrates that both Government agencies and NGOs in this community are well connected and cooperative with one another, sharing information and resources widely with others, and broadly involving others in joint planning activities, with a preference towards and between the organisations at the core of the network. As such it is reasonable to infer that this community has a high level of cooperation and coordination generally within the network, and that this is not due to the actions of a single organisation, but is a common mode of operating for the organisations in the community. This is consistent with insights gained from the interview data. Respondents described a tight-knit, well-connected local community of practitioners who are informally connected, who share information and resources and who undertake joint planning.

Despise these connections, the network analysis also found that organisations in the community have fewer partners in joint funding relationships, and these relationships exist in a decidedly centralised network with two dominating organisations being highly nominated as fulfilling this role. The two core organisations, one government and one NGO, were each nominated by at least half of all respondents, indicative of their central role in networks within the community. This indicates that despite a highly functioning network of working relations, these may not be being used to their full potential. Interventions aimed at improving the collaboration in this prevention system may need to aim at lifting the intensity of collaboration in existing relations, moving from information exchange to sharing resources, joint planning and ultimately joint funding, reflecting the informal to formal network transition described in the literature (Isett et al., Citation2011). Respondents in the interviews noted that, despite pressure to partner for joint funding purposes, and despite seeing the value in so doing, there remain significant barriers to the implementation of such partnerships. The barriers mentioned by respondents were consistent with those identified in the literature: time constraints in the development of partnerships, organisations that are structured and work differently struggling to find alignment, funding bodies creating indicators that are at odds with local need. Stakeholders noted that the partnering space is dynamic and constantly changing. The short-term nature of some relationships likely reflects funding and political cycles more than local need or ability.

Although the preventative health system in Australia currently consists largely of dispersed efforts at national, state and local levels to address population-level issues, there is an increasing focus on the establishment of inter-organizational partnerships that can be leveraged to bring diverse stakeholders together to coordinate and improve service delivery in the face of complex, intractable or wicked social problems. The literature suggests that partnerships between community organizations are important to furthering chronic disease prevention efforts (Dennis, Hetherington, Borodzicz, Hermiz, & Zwar, Citation2015). Practice in the community could be improved by re-focusing policy requirements for partnering to include recognition of the invisible and often unrewarded work of building and maintaining partnering relationships within communities, including the establishment of a shared vision, known to be critical for successful development of partnerships (Moran, Joyce, Barraket, MacKenzie, & Foenander, Citation2016). Rather than imposing partnering requirements at the level of grant applications, funding linked to existing relationships and rewarding long-term investment in collaborative practice could be a more effective approach.

Conclusion

The findings from this research demonstrate that significant barriers stymie efforts aimed at transforming existing, informal network arrangements into more structured inter-organisational partnerships for joint funding, limiting one potential area in which efficiency gains could be made for prevention. The data beginning to emerge from our work suggest that communities have existing strengths in local networks for “getting things done”, however the difficulties they face in establishing and maintaining more formalised, financially committed partnerships should not be underestimated.

Funding bodies seeking effective local action into complex problems like chronic disease prevention need to recognise and build on the efforts of local networks rather than seeking to impose top-down models of effective partnering. In turn, local agencies need to build on the existing infrastructure of informal networks when demonstrating ability to deliver services that are externally funded.

There are several implications of these findings in implementing change in the prevention system, in the absence of higher level systemic organisational and administrative mechanisms. The study demonstrates that building in requirements to partner for grants may not be enough to promote effective collaboration between organizations due to various barriers at both the granting level and at the community or organisational level. Building blocks for effective partnerships exist in communities, but systemic barriers can prevent effective partnering for funding purposes. We posit that addressing barriers at both levels will likely promote the development of more effective activity in the prevention of chronic disease through more effective joint funding arrangements for stronger collaborative partnerships.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was carrried out at The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre, hosted by the Sax Institute. We would like to thank our colleagues Maria Gomez, Sonia Wutzke and Penny Hawe for their contributions. The project could not have been completed with the generous assistance of our local community partners, local advisory group and the participants who gave up their time and expertise. We also acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which this work was carried out and pay our respects to elders past, present and emerging.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

References

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2016). Australia’s Health 2016. Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra, Australia: AIHW.

- Borgatti, S., & Everett, M. (1999). Models of core/periphery structures. Social Networks, 21, 375–395. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(99)00019-2

- Borgatti, S., Everett, M., & Freeman, L. (2002). Ucinet 6 for windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Burt, R. (1976). Positions in networks. Social Forces, 55, 93–122. doi:10.2307/2577097

- Chambers, M., Ireland, A., D’Aniello, R., Lipnicki, S., Glick, M., & Tumiel-Berhalter, L. (2015). Lessons learned from the evolution of an academic community partnership: Creating “patient voices”. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 9(2), 243–251. doi:10.1353/cpr.2015.0032

- Comrey, A. (1962). The minimum residual method for factor analysis. Psychological Reports, 11, 15–18. doi:10.2466/pr0.1962.11.1.15

- Corbin, J., Jones, J., & Barry, M. (2016). What makes intersectoral partnerships for health promotion work? A review of the international literature. Health Promotion International, 33(1), 4–26.

- Del Fabbro, L., Minniss, F., Ehrlich, C., & Kendall, E. (2016). Political challenges in complex place-based health promotion partnerships. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 37(1), 51–60. doi:10.1177/0272684X16685259

- Dennis, S., Hetherington, S., Borodzicz, J., Hermiz, O., & Zwar, N. (2015). Challenges to establishing successful partnerships in community health promotion programs: Local experiences from the national implementation of healthy eating activity and lifestyle (HEALTM) program. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 26(1), 45–51. doi:10.1071/HE14035

- Doerfel, M., Atouba, Y., & Harris, J. (2017). (Un)obtrusive control in emergent networks: examining funding agencies’ control over nonprofit networks. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(3), 469–487. doi:10.1177/0899764016664588

- Doreian, P. (1974). On the connectivity of social networks. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 3, 245–258. doi:10.1080/0022250X.1974.9989837

- Evenson, K., Sallis, J., Handy, S., Bell, R., & Brennan, L. (2012). Evaluation of physical projects and policies from the active living by design partnerships. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(5 SUPPL.4), S309–S319. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.024

- Filipovic, Y. (2013). Necessarily cumbersome, messy, and slow: Community collaborative work within art institutions. Journal of Museum Education, 38(2), 129–140. doi:10.1080/10598650.2013.11510764

- Freeman, L. (1979). Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social Networks, 1, 215–239. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7

- Harper, C., Kuperminc, G., Weaver, S., Emshoff, J., & Erickson, S. (2014). Leveraged resources and systems changes in community collaboration. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(3/4), 348–357. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9678-7

- Harris, P., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Hawe, P., Shiell, A., Riley, T., & Gold, L. (2004). Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(9), 788–793. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.014415

- Henderson, S., Kendall, E., Forday, P., & Cowan, D. (2013). Partnership functioning: A case in point between government, nongovernment, and a university in Australia. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 7(4), 385–393. doi:10.1353/cpr.2013.0049

- Hu, Q., Khosa, S., & Kapucu, N. (2016). The intellectual structure of empirical network research in public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(4), 593–612. doi:10.1093/jopart/muv032

- Isett, K., Mergel, I., LeRoux, K., Mischen, P., & Rethemeyer, R. K. (2011). Networks in public administration scholarship: Understanding where we are and where we need to go. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(Supplement 1), i157–i173. doi:10.1093/jopart/muq061

- Jalleh, G., Anwar-McHenry, J., Donovan, R., & Laws, A. (2013). Impact on community organisations that partnered with the act-belong-commit mental health promotion campaign. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 24(1), 44–48. doi:10.1071/HE12909

- Kindred, J., & Petrescu, C. (2015). Expectations versus reality in a university-community partnership: A case study. Voluntas, 26(3), 823–845. doi:10.1007/s11266-014-9471-0

- Klaster, E., Wilderom, C., & Muntslag, D. (2017). Balancing relations and results in regional networks of public-policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 27(4), 676–691. doi:10.1093/jopart/mux015

- Leat, D., Williamson, A., & Scaife, W. (2017). Grantmaking in a disorderly world: The limits of rationalism. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(1), 128–135. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12249

- Lecy, J. D., Mergel, I. A., & Schmitz, H. P. (2014). Networks in public administration: Current scholarship in review. Public Management Review, 16(5), 643–665. doi:10.1080/14719037.2012.743577

- Lee, J., Rethemeyer, R. K., & Park, H. H. (2018). How does policy funding context matter to networks? Resource dependence, advocacy mobilization, and network structures. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(3), 388–405. doi:10.1093/jopart/muy016

- Milward, H., & Provan, K. (2002). Measuring network structure. Public Administration, 76, 387–407. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00106

- Moran, M., Joyce, A., Barraket, J., MacKenzie, C., & Foenander, E. (2016). What does “collaboration” without government look like? The network qualities of an emerging partnership. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75(3), 331–344. doi:10.1111/aupa.2016.75.issue-3

- PARTNER Tool. (2012). Retrieved from program to analyze, record, and track networks to enhance relationships. Retrieved from http://www.partnertool.net

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Provan, K., Fish, A., & Sydow, J. (2007). Interorganizational networks at the network level: A review of the empirical literature on whole networks. Journal of Management, 33, 479. doi:10.1177/0149206307302554

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 11. Melbourne, Australia.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London, UK: SAGE.

- Silvia, C. (2018). Evaluating collaboration: The solution to one problem often causes another. Public Administration Review, 78(3), 472–478. doi:10.1111/puar.2018.78.issue-3

- Tan, E., McGill, S., Tanner, E., Carlson, M., Rebok, G., Seeman, T., & Fried, L. (2014). The evolution of an academic-community partnership in the design, implementation, and evaluation of experience corps® Baltimore city: A courtship model. Gerontologist, 54(2), 314–321. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt072

- Thompson, V., Drake, B., James, A., Norfolk, M., Goodman, M., Ashford, L., … Colditz, G. (2015). A community coalition to address cancer disparities: Transitions, successes and challenges. Journal of Cancer Education, 30(4), 616–622. doi:10.1007/s13187-014-0746-3

- Valaitis, R., Hanning, R., & Herrmann, I. (2014). Programme coordinators’ perceptions of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats associated with school nutrition programmes. Public Health Nutrition, 17(6), 1245–1254. doi:10.1017/S136898001300150X

- Watts, D. (1999). Small worlds. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2014). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Wilkins, P., Phillimore, J., & Gilchrist, D. (2015). Public sector collaboration: Are we doing it well and could we do it better? Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75(3), 318–330. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12183

- Willis, C., Riley, B., Taylor, M., & Best, A. (2014). Improving the performance of interorganizational networks for preventing chronic disease: Identifying and acting on research needs. Healthcare Management Forum, 27(3), 123–127. doi:10.1016/j.hcmf.2014.06.001