ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the governance challenges that increasing hybridity poses to higher education institutions (HEIs). It examines the potential of network governance as a public governance approach that allows HEIs to find a good fit to their environment and become accountable to complex stakeholder environments. Central research questions are as follows: (1) Is network governance a suitable model to address organisational complexity and associated competing institutional logics? (2) What characterises the network model for HEIs in such a setting? A Delphi method, semi-structured in-depth interviews and collective meetings with HEI policy makers are combined with a literature review and case studies to distinguish an integrated governance model for teacher trainings with multiple suppliers. Our findings suggest that a network model combines the development of efficient cooperation structures within and between HEIs. As key success factors the study identified a reduction of competitive pressure, financial security, internal and external transparency, organisational autonomy and a clear vision.

Introduction

Higher Education institutions (HEIs) have been subjected to many reforms, encouraged by the emergence of a knowledge society, economic crises, increased competition, globalisation and demographic evolutions (Broucker et al., Citation2016; Dobbins et al., Citation2011; Hazelkorn, Citation2015; Kehm & Stensaker, Citation2009; Morris, Citation2011; Pusser & Marginson, Citation2013). Those HE system reforms have been conducted on the basis of New Public Management (NPM) paradigm (De Boer et al., Citation2007; Broucker et al., Citation2017; Deem et al., Citation2007; Ferlie et al., Citation2008; Tahar et al., Citation2011). NPM has been described as a toolbox of organisational techniques, from which HEIs can pick different elements and implement them to varying degrees. Within that context, many countries have been seeking new ways to steer their HE sector (De Boer & File, Citation2009). Although the manner and degree of HE governance reform implementations vary across countries (De Boer et al., Citation2008), there are similarities in terms of language, aims and instruments. The following main features of HE reforms can be distinguished (Broucker & De Wit, Citation2015; Nõmm & Randma-Liiv, Citation2012; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2004): an introduction of business management techniques for better efficiency and performance (Mergoni & De Witte, Citation2021); an improved service and client orientation; the introduction of market mechanisms and increased competition.

Despite the identified NPM-trend, there are two evolutions that challenge this managerial focus in addition to the underlying challenges within HEIs induced by both the organisational transformation and managerial change that occur in the aftermath of NPM reforms, thus at micro level (Andersen, Citation2008; Dal Molin et al., Citation2017; Frølich, Citation2011; Rutherford & Rabovsky, Citation2014; Taylor, Citation2009). First, there has been a scholarly critique on the one-sided market emphasis (e.g., Adcroft & Willis, Citation2005; De Boer et al., Citation2008; Broadbent, Citation2007; Shattock, Citation2008; Singh, Citation2001). In general, focus is on the macro level, complemented by meso-level implications. Scholars have pointed out that NPM generated unwanted side-effects as fragmentation or diminished coordination (Broucker et al., Citation2017). A one-sided fixation on market competition has been argued to be detrimental for the HEIs potential to add public value (Maassen, Citation2012 &, Citation2017; Van Vught & Westerheijden, Citation2012).

Second, an institutional evolution, related to the change that has taken place in the nature of the HE sector in itself – i.e. meso level change, and embedded micro-level transformations: HEIs are increasingly becoming ‘enterprising non-profits’ (Jongbloed, Citation2005) and have been described more frequently as ‘hybrid’ organisations (Brandsen et al., Citation2005; Evers & Laville, Citation2004), characterised by Mair et al. (Citation2015) as having a variety of stakeholders, a pursuit of multiple and conflicting goals, and engagement in divergent activities. Hybrid organisations are complex as they are confronted with, but also immersed into, multiple logics as “socially constructed, historical patterns of practices, assumptions, values, and rules” (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999, p. 804). Broucker, Huisman et al., (Citation2018) built on the competing values argument (Talbot, Talbot, Citation2008a, Citation2008b) by stating that the way HEIs are organised, creates a conflict of objectives, values and results – as different logics intertwine. HEIs aim to be competitive, efficient and profitable (NPM-type logic), but, on the other hand, also want to be a vehicle for social mobility and impact other non-economic objectives. Accordingly, Van der Wal et al. (Citation2009) argue that governance models should accommodate for value pluralism that coincides with hybridity.

Consequently, it has been argued that within this trend of increased hybridization, multiplication of stakeholders and competing institutional logics, there is a need for new organizational – more hybrid – models of governance (Broucker et al., Citation2017; Jongbloed, Citation2015). In other words, it is argued to look beyond New Public Management techniques as a way to steer the sector, and to seek for a more holistic governance model capable of addressing the multiple logics, expectations and stakeholder groups.

This article discusses the potential of network governance for HE as a model to address the above-mentioned challenges. Indeed, despite the idea of a network or shared governance model is attractive and seems obvious, the question has to be raised whether a network model surpasses the limitations of other governance models and delivers what it theoretically promises. Herewith this study contributes to our insights on network governance in HE, but it also allows to discuss its potential to address the increased hybridity of HEIs. Moreover, addressing this question also provides insight into the type of preferred network governance. This is a necessary debate, because implementing a network model in HEIs can be hampered for reasons of competition between and autonomy of HEIs. Using the case study of a reform in the teacher training program, two research questions are formulated: (1) Is network governance a suitable model to address organisational complexity and the associated competing institutional logics? (2) What typifies the network model for Higher Education Institutions in such a setting?

The case study of teacher training in the Flemish region of Belgium is used to distinguish an integrated governance model for education programs with multiple suppliers. Teacher training provides an interesting application as it is characterised by a large number of stakeholders and competing organisations, and it addresses multiple (conflicting) goals and values. This case allows to build further on what has been written on HEI governance – mostly at macro level – by making the bridge with the meso level, within and between HEIs. By looking a priori at the context-specific feasibility of a model, rather than evaluating the effectivity of an implemented model, this article contributes strongly to the literature. It provides insight on how the ideal-typical network governance model needs to be adapted in order to be fit-for-use – in different scenario’s and cooperation structures. Put differently, it is essential to check and adapt model proceeding expectations.

Our results demonstrate that a governance model should not look primarily for an optimal level of cooperation as such but, instead, look for a minimal level of cooperation, which can be confronted with the (time-specific) positions of different stakeholders.

Theoretical background

The literature highlights different HE governance models. Broucker et al. (Citation2017) indicated that over the years two different positions have been taken. A first position includes the alternative New Public Management (NPM) models, resulting in post-NPM paradigms, such as “digital-era-governance” (Dunleavy et al., Citation2006), “New Public Governance” (Osborne, Citation2006; Torfing & Triantafillou, Citation2013), “Public Value Governance” (Alford & O’Flynn, Citation2009; Bozeman, Citation2007; Mintrom & Luetjens, Citation2017; Try & Radnor, Citation2007), or “integrated governance” (Halligan, Citation2007). As a second position, it is argued that these theories merely highlight an adaptation of NPM rather than postulate a replacement (Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2007; De Vries & Nemec, Citation2013). Notwithstanding the lack of consensus, both positions have various elements in common. First, they share the need to have an alternative rationale for governance than a purely economic rationale (Singh, Citation2001). Second, they indicate an increased emphasis on inter-connectedness, collaboration and participation between organizations, and between government and others (Christensen, Citation2012). Starting from the common grounds, paradigms as network governance, new public governance, and public value (Broucker, Huisman, et al., Citation2018) have been described. These models focus on interaction, interdependence, and mutual agreement of the university with external stakeholders; and on a multitude of values. The models drift away from NPM by taking an external view in which the government is no longer the only authoritative actor, nor is the market the only coordinating mechanism (Broucker et al., Citation2017). Moreover, and maybe even more importantly, those models address identified flaws in research that are linked to the NPM-model. The reason why the impact of NPM reforms is still not fully understood is because NPM as a model lacks contextualisation, while this is core when studying for instance, Network Governance. In concrete, it is still not fully clear whether NPM-based reforms have made higher education institutions cheaper of more effective (Broucker & De Wit, Citation2015; Broucker et al., Citation2017), because NPM-reforms can in fact only be understood if they are placed into their context – which NPM governance models quite often neglect to do. The HE context is a policy-context, consisting of a multitude of stakeholders and wherein other than economic parameters are relevant. Studying Network governance (with its characteristics of collaboration, trust, connectedness) allows to incorporate this context and herewith to better understand to a higher degree the flaws of the NPM-model and the potential of Network Governance: “If we want to assess the flaws linked to NPM-based policy and reform, it is important to reflect systematically about the policy process, to understand not only policy and its intended outcomes, but also its complexity and the multitude of goals, given the many stakeholders and policy steps in the process.” (Broucker et al., Citation2017, p. 4). Consequently, the Post-NPM literature provides inspiration for quality-motivated cooperation structures within and between HEIs with a view to high-quality education programmes and thus going beyond the – rather narrow – scope of NPM. While developing a HE governance model, the economic ratio is instrumental – and contingent on the financial resources at hand, sometimes necessary – to guarantee high-quality education. However, the novelty in the literature comes with the introduction of the shared aspect of governance. This element implies an increasing role for negotiations and the increased importance of external stakeholders; it includes the participation and integration of all groups and objectives relevant to HE. This goes hand in hand with the emergence of the network governance narrative. That is, within this narrative, HE systems are understood as multi-level, self-steering and self-organising networks between societal and academic actors which facilitate joint problem solving and the diffusion of best practices (Dobbins et al., Citation2011).

Studying network governance in Flanders contributes to a second way the current state-of-affairs in research: in Flanders most research on higher education policy has a strong descriptive or explorative approach, and lacks an explanatory approach (Broucker, Huisman et al., Citation2018). Using the Network Governance approach will contribute to that flaw because the model encompasses the context of Higher Education allowing more explanatory insights. Moreover, in Flanders, there is limited insight on the impact of previous reforms; most research conducted does not take into account certain institutions for higher education; and there are major flaws in the study of the management and governance of Higher Education. Using network governance in the case of teacher training in Flanders addresses those different elements and will contribute to the research of HE in Flanders. This study is also of international interest. In fact Flanders is only studied quite limitedly in international studies, but this is striking, both from an academic as well as a policy oriented perspective: Flanders has been a forerunner with respect to the Bologna process, was a mid-adopter of NPM, and has generally a very high reputation when it comes to the quality of its higher education system. Those reasons make it highly relevant to study new governance models in complex HE settings (Broucker, Huisman, et al., Citation2018).

Methodology

This article applies a triangulated research design with four interrelated stages to exploit insights from a major reform of the teacher training in Flemish HEIs (see section 4). First, a document analysis relating to the case of teacher training in Flanders was conducted. We focussed on policy documents and legal regulations of HEIs in Flanders in order to understand the structure and management of teacher training programmes – before and after the reform. Moreover, policy notes and documents of the Flemish government and of the ministerial working groups were included in the analysis.

Second, a first round of semi-structured in-depth interviews (following Healey-Etten & Sharp, Citation2010; Louise Barriball & While, Citation1994) with policy makers in Flemish HEIs between March and May 2017 was conducted. Those interviews had a twofold objective: first, to explore the perception of the different stakeholders on the reform and to increase our understanding of the multitude of expectations and objectives towards that reform; second, to fuel our insight into the associated impact of the increased complexity on the future governance for the teacher trainings in Flanders.

Third, an international benchmark study aimed to explore similar governance mechanisms and structures in complex organisational settings (Simons, Citation2014; Yin, Citation2012). Six cases were identified in total, both in Flanders as in the Netherlands, among which a case outside the HE sector for inspirational purposes (Muyters et al.,, Citation2018Citation2018). This not only allowed to make an international comparison, but provided the necessary input to operationalise the different governance mechanisms to be applied in this case.

Finally, a follow-up interview round was organised – bearing in mind the policy evolutions that had taken place between the start of the reform project and the actual stage of the research. In this final stage of the research, a Delphi-series of meetings was applied to test different governance models and assess the implication of its operationalisation. In concrete, this implied the organisation of successive collective meetings with policy makers at which they were ‘confronted’ with differences and similarities of views vis-à-vis diverse governance models. Through these meetings at which the common engagement towards increasing study programme quality stood central, several key starting points to organise teacher trainings in Flanders emerged.

summarises the four interrelated stages in one circular research design with two branches: desk research on the one hand and interviews and Delphi meetings on the other hand. At the beginning of the results section we refer back to this table in order to clarify how the different phases of the methodology contributed to obtain the results presented.

Table 1. Summary of the circular research design

Context – The case of teacher training in Flanders

Before the reform plan of the Minister of Education (2017), three types of suppliers (centres for adult education (CEA), university colleges (UCs) and universities) organised teacher training programmes in Flanders. This model generated several problems, both at the macro and meso level: resource inefficiency, organisational fragmentation, an uneven level of educational quality due to this fragmentation, conflicting visions and ideas about the disciplinary and pedagogical competencies teachers for secondary school are supposed to have, governance misalignment due to coordination and steering complexities. These complexities, which were confirmed by policy makers at system and institutional level, very well match the overall disadvantages that have been described by scholars towards NPM. In other words: NPM and NPM-related techniques were in fact not only unfit to tackle the increasing level of complexity, but might also have introduced the complexities due to a misalignment between techniques used and expected results.

To offset these disadvantages, a multidimensional teacher trainer reform was proposed. First, it encompassed integration of personnel and financial resources of CEA programmes into the university colleges and universities with a view to diminishing the number of providers and to allow a clear distinction between Level 6 (bachelor) and Level 7 (master) programmes in the European Qualification Framework. In particular, UC’s would organise qualifications at level 6 and universities at level 7. Herewith the government opted for a rationalized structure, with a clear distinction in levels provided by only two categories of HEIs (UC’s and universities). Second, this rationalisation aimed to increase efficiency, transparency and quality, though risked a potentially diminished geographical offer in Flanders. Indeed, CEAs were abundantly spread over the region, while UCs and universities were regionally concentrated. As a possible downside of the reform was related to the concern that this integration would generate a loss of pedagogical expertise that had been built over the years within the CEAs. Moreover, the integration into UCs and universities could generate a significant workload increase for UCs and universities. As a final downside, despite the rationalisation, a regional increased competition for resources between UCs and between universities could be expected.

The increase of hybridity with respect to this particular training programme is key: the HE landscape was characterised by a large number of stakeholders and involved organisations, with different types of HEIs organising several distinct types of teacher training programmes. Within this setting each institution had its own culture, expertise and partners within the education field. As a result, not only the teacher training would change, but also the interrelation between actors in the field, stakeholders and institutions delivering the training.

Moreover, the reform aimed to combine two different logics. On the one hand, the reform was driven by the efficiency logic as it was assumed that HEIs had to provide qualitative study programmes within their budget constraints. This objective was in conflict with the existing smaller CEAs spread over the Flemish community for proximity purposes (for schools and teachers). On the other hand, the reform conflicted with the societal expectation that society as a whole needs highly educated teachers.

In this complex setting, multiple goals and values had to be addressed. And to simultaneously realise these goals and underlying values fragmentation of expertise, didactical and financial resources had to be transcended. Within this context and in line with the theoretical framework, demand for a new governance structure raised.

Results

Identified network governance models

Is network governance for HEIs a suitable model to address the organisational complexity and the competing institutional logics? Based on a literature/document review and comparative case study in our desk research branch (cf. ) we established a benchmark in that we got a clear view on the organisational status quo of teacher trainings in Flanders and discovered best practices and learned lessons from other (similar) cases in the Netherlands and Belgium (anonymized, 2018). A Delphi approach was then initiated to gradually determine an integrated governance model with opportunities and conditions.

More concretely, after the introductory collective meeting, with the presentation of our literature/document review, the first round of individual interviews with institution policy makers was conducted. The interviewers presented the full range of (theoretical) possibilities on organising teacher trainings in Flanders that were deduced from the desk research and asked to evaluate this via the questionnaire that can be consulted in annex 1. These interview results where summarized to present during the second collective meeting (anonymized, 2018). Although the main focus of this paper is to discuss the final results on network governance, we include for the sake of transparency the summary scheme of opportunities and conditions as they were mentioned during the first interview round in annex (i.e. when still the full range of possible governance structures induced from our literature review and comparative case study was considered). Note that the research team never added an opportunity or condition, nor did they propose to do so during collective meetings. Instead, each time explicit approval was asked for the summary of previous interviews/sessions before proceeding to a discussion on further propositions and refinements. This new information was used in a similar fashion to deduce the specificities of a network model (which was broadly accepted as the preferred option in the earlier stage). Four alternative cooperation models where crystalised and again presented during the second round with individual interviews, followed by three more collective meetings.

Our findings indicate the potential of a network model to cost-effectively provide high-quality education programmes. The qualitative research clarified that efficiency as mere goal as well as fragmentation can be transcended when cooperation dynamics are established. Indeed, a well-thought cooperative network structure would allow the combination of (1) proximity of educational programmes throughout the region, (2) high-quality educational programmes adjusted to the needs of divergent target groups, (3) economies of scale through the integration, and (4) the continuous availability of expertise and resources in the region. Yet, at a theoretical level there was hardly any disagreement. Network governance was indeed considered by all involved stakeholders as the most elegant and optimal way to cope with a multitude of stakeholders, organisations and expectations within a single region.

However, network governance can be implemented in various ways. As network models with deeper levels of cooperation require more far-going conditions to be met, HEIs will at a certain point opt for a lower degree of cooperation. To anticipate this delicate balance, our results demonstrate that a governance model should not look primarily for an optimal level of cooperation as such but instead look for a minimal level of cooperation which can be confronted with the (time-specific) positions of different stakeholders. Using the benchmark study several potential ‘prototypes’ of cooperation structures were developed. Then, the different models were discussed with key stakeholders. highlights the results of this discussion. It demonstrates the input concerning cooperation that was gathered during the second interview wave. For every HEI it is shown whether a cooperation model in general is considered (from red to green): ‘impossible’, ‘not impossible but with reservations’, ‘possible with some reservation’ or ‘certainly possible’. Moreover, the level in the European qualification structure (6 = bachelor, 7 = master) is taken into account. In other words, the table summarises the level of support for each cooperation model.

From , the following lessons are important. The first model ‘No cooperation’ discussed the possibility of maintaining as much as possible the status quo in a region. This is due to the fierce competition between UCs. In this scenario, UCs will in first instance invest in intra-institutional connections (i.e. between programmes within a HEI). The result is that every HEI in a region would work relatively independently and would maintain its individual position. No need to say that model 1 would not only hamper cooperation in many aspects, but would also inhibit educational cooperation between qualifications at Level 6 and Level 7 (which in the former situation, however, was the result as CEA offered both qualifications of level 6 and 7 within their own institution). Within this relatively protective model, some key conditions were defined to minimize the side-effects of competition and institutional rivalry: stakeholders agreed that transparency about and an agreement on external communication in general and commercial activities in particular was said to be paramount, to avoid competitive pressures in a region.

Table 2. Support for cooperation models in Flemish teacher trainings

Model 2 ‘Cooperation without students’ and Model 3 ‘Cooperation with Students’ proposed a certain degree of inter-institutional cooperation. Here, the basic idea is that study programmes would be shared, with an increasing cooperation intensity. Model 2 depicts a situation of minimal cooperation, where at least expertise is shared and best practices are benchmarked. In this case, cooperation will only be between (teaching) staff, but not at the level of students. In other words: institutions within a region would share staff, but not students. Moreover, attention will not be (directly) allocated to exploring synergies between qualifications at levels 6 and 7. For example, there will be no shared courses but information exchange between teaching staff can be facilitated through didactic communities.

Model 3, which can be understood as an extended version of the previous model, assumes cooperation between HEIs with regard to both teaching staff and students on the one hand (e.g., shared courses between universities) and with attention for connections between qualifications at level 6 and level 7 on the other hand (e.g., expertise sharing between teaching staff). Pooling students is considered a possibility in particular for domain-specific didactical courses in order to achieve a ‘critical mass’ to provide qualitative study programmes given the financial constraints. This is also the case between university colleges and universities, which, respectively, provide (mainly) education programmes at qualifications of level 6 and level 7, in so far that the level-specific challenges with providing, securing and monitoring quality are coped with. The universities – which are more spread geographically – strongly support cooperation for qualifications at level 7. Managing differences between systems (learning platforms and quality assurance) is considered a fundamental condition for success. In case of cooperation with qualifications at level 6, securing the realisation of different quality standards is considered fundamental. Since some HEIs are active in different regions, it is stressed as well that searching for cooperation opportunities (and thus differentiation possibilities) may result in regional accent differences – depending on the partners – while the starting point is to build a common vision.

Model 4 ‘Shared programs’ corresponds with a situation of maximal cooperation. This implies that common study programmes (with one front office) are created within a region. Based on the reasoning that cooperation intensity is positively associated with governance complexity, inhibition towards this model has been revealed. Indeed, the challenges of securing and monitoring education quality and managing system differences are expected to be more stringent. Interestingly, and adds at the economic incentives, universities did not exclude this option when it comes to cooperation with a similar institution.

Opportunities for network governance

Three opportunities for a network model have been distinguished by combining the insights from a literature review, case study research and interviews. First, quality improvement can be realised by (i) organising at least information exchange (when competition dynamics cannot be sufficiently put aside) and benchmarking (in first instance between a coalition of ‘willing HEIs’ if necessary). Furthermore, (ii) by pooling the expertise and experience of the staff members knowledge can better be accumulated and spread. The conceptualisation of new curricula creates a momentum to exploit this opportunity. However, as the new governance model requires that people move from one organisation to another, it is essential to take away uncertainty among the personnel that will be transferred to a different HEI in an early stage and to invest in a genuine staff integration (cf. infra). The latter is then in line with the necessary broader commitment of each HEI towards its role in the reform.

Second, sharing expertise, be it through informal or formal dialogue, can lead to all involved parties recognising win–win opportunities created by cooperation. This is a fundamental condition for deeper cooperation at the level of the individual employee or at the level of the students as well (i.e. offering study programmes in cooperation or joint study programmes). In turn, this can trigger a decrease in competition throughout time, which is preferable in case of prohibitive rivalry that hampers initiatives to investigate cooperation opportunities.

As a third opportunity of the new governance structure, economies of scale can be sought inter-institutionally as well as intra-institutionally (within institutions that provide education at different levels of the qualification structure). The latter is the case when HEIs are involved in a fierce competition characterised by a mutual lack of trust and conflictual marketing. As a result of sufficient scale (with the assumption of a fixed budget) an efficient allocation of available (didactical) resources can be ensured. This is especially the case for domain-specific didactical courses which are typically characterised by smaller student groups.

Conditions for network governance

The analysis points to five conditions to successfully implement a network model at the level of HEIs. First, competition ought to be transcended for enhancing teacher trainings because competitive dynamics hamper cooperation opportunities from being explored. To ensure this, a project group with (proportional) partner representation can be initiated so that clear and explicit arrangements about the implementation of the organisational reform and the inherent transition period can be made. Second, sufficient attention should be given to coping with financial uncertainty. To align different funding models and cost price systems HEIs can define a deadline to implement a single system. Third, sufficient attention has to be spent on clarity and transparency between different levels within the European qualification structure. This has an internal and an external dimension: (1) Internal clarity implies the timely communication of the governance structure within the HEIs (bearing in mind the continuity of the education programmes during the transition period before the integration is realised). (2) External clarity refers to an unambiguous communication (about the level of the programme/the trajectory), on the one hand towards (future) students and on the other hand towards the working field. In line with the network idea, a working group with members of the different institutions can streamline external communication. Fourth, the convergence of vision (regarding curricula and quality assurance systems) is a key element that needs to be taken care of. Within the confinements of a project group, the willingness to converge can be boosted by first looking for those elements that connect partners, before focussing on the aspects that divide them. Apart from meetings at the strategic level, conversations between teaching staff of different HEIs can be facilitated. As a fifth condition, the freedom/autonomy (to cooperate with an external partner) ought to be borne in mind sufficiently. This can be done by paying attention to all potential partners and the impact of specified formal structures during (preparatory) meetings.

Operationalisation of network governance: four key themes

In order to implement a governance model for integrated education programmes with multiple suppliers, the research provides specific insights in the operationalisation of governance models. Key features of a network model in a hybrid set-up are discussed along four main aspects: personnel, finance, quality assurance and (didactical) infrastructure.

With respect to personnel management, four starting points were distinguished during the interviews. First, it is key to start off with an agreed vision on the formal framework to guide the personnel (re-)allocation and related impact on staff statutes. Second, in the case of personnel transfers, within each ‘receiving institution’, HR policy should take into account the existence of different institution-specific cultures in general and the risk of a fragmented personnel pool in particular. Third, respondents point to the opportunity to maximally deploy the existing pool of knowledge and expertise. Fourth, offering full transparency from the beginning onwards vis-à-vis the staff is paramount. Also, homogeneous task descriptions ought to be an equally important target.

With respect to managing financial transfers, there is a significant uncertainty as the basic distribution of staff members has to be made while the number of enrolling students (in each HEI) is not yet known. The broadly supported starting point is to connect the allocation of personnel costs with the estimatedFootnote1 future student distribution that impacts the input-based government funding of HEIs. The only exception is upfront clarity about intensive interinstitutional cooperation (model 4 in ) in which case the fractional distribution can be based on the effective cooperation for which the underlying agreement stipulates the input of each partner. However, model 4 was in general not considered a first-best option, especially when it comes to cooperation between university colleges and universities. Therefore, the involved institutions urged for the legal framework to offer sufficient leeway for the HEIs to come to an agreement on ex-post reallocating staff members. Thus, the level of uncertainty as a result of the connection between staff integration and estimated student flows is reduced by granting enough autonomy to HEIs to conclude agreements with a clearly explicated time horizon on staff reallocation after implementing the integration.

The third aspect is quality assurance. HEIs organise study programmes that consist of courses which in turn can entail several educational activities. The starting point is to assure high-quality educational programmes conform the relevant (level-specific) standards. Cooperation impacts four elements – to a different extent contingent on the cooperation intensity: the student administration, the education and exam regulations, the quality assurance system and the online learning platform. For interinstitutional cooperation to work, both the willingness and technical capacity to reach convergence on these elements is crucial. The situation in which HEIs do not cooperate is straightforward, as institutions will use their own systems. On the other side of the continuum, ‘joint programmes’ implies the need for the involved actors to conclude an agreement on a singular administration, a singular education and exam regulation, a singular quality assurance system and a singular learning platform. Opting for the systems of the front-office institution can be a guiding principle in this matter. Since these rather stringent prerequisites apply, model 4 is considered an option in the context cooperation between similar organisations.Footnote2 A more moderate possibility is to organise ‘programmes in cooperation’, e.g., abridged programmes, i.e. a defined subset of courses that constitute a study programme. When the involved institutions are both university colleges or both universities, the same domain-specific learning results apply. However, the study programme-specific learning results are formulated at the level of the HEI and thus differ in practice. Therefore an agreement between the involved HEIs should be made. Moreover, three other elements ought to be incorporated: in this situation there will be X administrations, X education and exam regulations and X quality assurance systems – with X equals to the number of involved HEIs. Especially the last aspect of different quality assurance systems is paramount. The necessary agreement between the parties should at least be clear about the number of registration desks (1 to X), the number of quality surveys for each course (1 to X) and the streamlining of education and exam regulations. When on the other hand the involved institutions are not similar, also different domain-specific learning results apply. Furthermore, the same insights as with cooperation between similar partners apply mutatis mutandis. Yet there is one substantial difference with regard to quality assurance. There will be X registration desks, X quality surveys for each course and student evaluation needs to be organised separately depending on the relevant level in the qualification structure.

The final aspect is infrastructure which encompasses both buildings and didactical resources. Within the network governance structure, the starting point is that receiving institutions make use of their own buildings. When the exception applies and buildings of another HEI will be used, a consumption allowance is preferred over a rental agreement when depreciation is subsidised by the government. Regarding the didactical resources, a trade-off was recognised between realising economies of scale with a view to quality increases on the one hand and managing complexity on the other hand. Complexity reduction becomes in particular relevant when cooperation intensity reaches at least model 3 (cooperation with students involved), unless the same online learning platforms are in place.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper examined whether network governance is a suitable model to address organisational complexity and the associated competing institutional logics?; and what typifies the network model for HEIs in such a settHEIsing? To formulate an answer a Delphi method, semi-structured in-depth interviews and collective meetings with HEI policy makers were combined with a literature review and case studies to distinguish an integrated governance model for teacher trainings with multiple suppliers.

As such, this article contributed to the literature by building on Post NPM insights to investigate (1) to what extent a network governance model can put HE (back) in its broader context with broader social goals and multiple stakeholders, and (2) how the conditional opportunities of cooperation can benefit from applying specific network model features. Coping with institutional hybridity was at the end of the day the goal of the teacher training reform in Flanders, which is the case study in the present paper. It thus allows us to check the contextual feasibility of the theoretical model and to adapt the model to the context to make it fit-for-use. This is informative to deepen our understanding of network governance. For one, it is important to bear in mind that the ideal-typical features of such a model are not informative per se for understanding how to apply it. Indeed, more emphasis on the preconditions of a model rather than on the model itself would be beneficial. A further string of research could be to investigate the effects of such a model. By testing whether the underlying assumptions and expectations of network governance models hold for our application, we showed that the following factors of success are met: reduction of competitive pressure, financial security, internal and external transparency, organisational autonomy and a clear vision. Effective implies in this context that the governance structure was thought to combine the development of efficient cooperation structures within and between HEIs with the delivery of high-quality education programmes, that satisfies the multitude of stakeholders and their potentially conflicting expectations.

When deeper cooperation requires more far-going conditions to be met, HEIs will at a certain point opt for a lower degree of cooperation. To anticipate this, a governance model should not look primarily for an optimal level of cooperation as such but instead it should also look for a minimal level of cooperation that can be confronted with the (time-specific) positions of different stakeholders.

Furthermore, as indicated by all stakeholders in our case study, implementing a governance model requires the operationalisation of coordination- and cooperation models with respect to four key aspects: personnel, finance, quality assurance and (didactical) infrastructure. This article helps understanding how this could work in practice.

Any case entails to some extent idiosyncrasy. For example, management issues such as rationalizing physical (e.g., buildings) and didactical (e.g., software licenses or online platforms) infrastructure depend on the specific status quo (is infrastructure connected/compatible?). However, it appeared that especially a set of strategic choices where key to develop a governance model that was perceived fit-for-use. (1) Geographical dispersion of supplied programs. (2) Quality assurance given cooperation between trainings organized at different levels within the qualification structure. (3) Coping with financial uncertainty (when personnel reallocation is required based on anticipated between-institution student flows and associated income lines). (4) And lastly providing a solid frame for (transferring) staff members that allows for flexibility upon implementation and evaluation on the one hand while giving sufficient in-time information to protect and develop human capital within new and existing personnel teams on the other hand. These focal points correspond highly to what we observed in our comparative case study (anonymized, 2018), which adds confidence that these insights are relevant outside the scope of our research case as well. Although the regional context obviously matters, our results help to draw some more general lessons when it comes to addressing institutional hybridity in HE. As has been argued before, although the manner and degree of HE governance reform implementations vary across countries, there are similarities in terms of language, aims and instruments and as a result similarities in terms of challenges (narrow efficiency goals, disaggregation, negative competition dynamics) as well.

Moreover, and this is key for the overall validity of the results, our circular approach permitted us to question the relevant institution policy makers as well as allow them to ‘interact’ within a Delphi setup – before, while and after the guiding legislative text was drafted by the Flemish government. Such this was not a hypothetical exercise like a thought-experiment nor an ex-post reconstruction of opportunities and conditions. Instead, we could follow-up our respondents during the policy process from the end of the agenda setting phase through decision-making just up to the beginning of implementation. This strategy not only mimics our a priory focus (not on policy evaluation, rather on checking and adapting model proceeding expectations) but also helps to ensure external validity, something that is important to take into account while applying a Delhpi process (Rowe & Wright, Citation2001). That is we can exclude several forms of respondent bias (e.g., memory bias). The specific issue of strategic answering (given that expert-interviewees are policy makers at micro level) is handled by the very nature of the Delphi approach. More specifically by putting emphasis on the collective process of distinguishing an integrated governance structure both during individual (follow-up) interviews and collective sessions while explicitly evaluating and re-evaluating the (shrinking) set of propositions. Also, our research time scope exceeds this of the policy decision phase which fuels confidence in the responses of our respondents. To circumvent researcher bias the semi-structured interviews were conducted each time with a guideline questionnaire (they can be consulted in annex) by the same interviewers to avoid probing and/or prompting issues (Healey-Etten & Sharp, Citation2010; Louise Barriball & While, Citation1994). Also, aggregating results at all major steps in the circular design was always done by discussing them with the entire researchers team before presenting them for approval during a collective session with representatives from all institutions.

This study gives rise to further research. First, network governance in itself is a broad concept that can be developed in a large number of ways. The broad conceptualisation of network governance necessitates a better characterisation to increase its understanding and usability in specific cases. Indeed, other governance models have never argued against cooperation, while network governance in itself has put cooperation at the centre of its model. This article clarified that cooperation can take many different forms and levels of intensity. This raises the question whether network governance as theoretical concept is an overarching model for other types of governance, or whether is clearly distinguishes itself from other models – but if that is the case the concept in itself need more research to better understand what those differences are and what particularly typifies network governance.

A second element to be further investigated is whether similar conditions, opportunities and characteristics of network governance models can be identified in other countries and similar higher education settings. This international comparison would not only contribute to a better understanding of the characteristics of network governance in itself, but it would also contribute to our understanding of steering, coordination and cooperation mechanisms in higher education in general. As said, Higher Education Institutions operate in a complex environment with a multitude of stakeholders, expectations and values. The potential of network governance is that it can adapt itself to this environment. The question however then is: is network governance a model to be applied in many different settings, or do settings needs specific characteristics before a model of network governance can be of use?

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Flemish ministry of Education and Training for funding via the transition project ‘towards an integrated organisation model for teacher trainings with multiple suppliers’. Kristof De Witte is grateful to internal KU Leuven funding. We acknowledge useful comments from Elly Quanten, Paul Martens, Bregt Henkens, Tommaso Agasisti, and participants at the LEER Seminar Series.

Disclosure statement

The authors acknowledge funding from the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training. Kristof De Witte is grateful to internal KU Leuven funding. However, no direct benefit has arisen from the direct applications of the research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The estimation can be based on the current ECTS credits (for teacher trainings at bachelor and master level).

2. In the context of Flanders this means inter-university cooperation.

References

- Adcroft, A., & Willis, R. (2005). The (un)intended outcome of public sector performance measurement. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 18(5), 386–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550510608859

- Alford, J., & O’Flynn, J. (2009). Making sense of public value: Concepts, critiques and emergent meanings. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 171–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732731

- Andersen, S. C. (2008). The impact of public management reforms on student performance in Danish schools. Public Administration, 86(2), 541–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00717.x

- Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

- Brandsen, T., van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or Chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9–10), 749–765. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200067320

- Broadbent, J R. M.O. Pritchard & A. Pausits & J. Williams (Eds.),(2007). If you can’t measure it, how can you manage it? Management and governance in higher educational institutions. Public Money & Management, 27(3), 193–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2007.00579.x

- Broucker, B., & De Wit, K. (2015). New public management in higher education. In J. Huisman, H. de Boer, D. Dill & M. Souto-Otero (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of higher education policy and governance (pp. 57–75). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Broucker, B., De Wit, K., & Leisyte, L. (2016). Higher education reform. In R. M.O. Pritchard & A. Pausits & J. Williams (Eds.), Positioning higher education institutions (pp. 19–40). Sense Publishers.

- Broucker, B., De Wit, K., & Verhoeven, J. C. (2017). Higher education research: Looking beyond new public management. In J. Huisman & M. Tight (Eds.), Theory and method in higher education research (pp. 21–38). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Broucker, B., Huisman, J., Verhoeven, J., & De Wit, K. (2018). The state of the art of higher education research on Flanders. In J. Huisman & M. Tight (Eds.), Theory and method in higher education research (pp. 225–241). Emerald Publishing Limited. 4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S2056-375220180000004014 Open Access.

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (Eds.). (2007). Transcending new public management: The transformation of public sector reforms. Gower Publishing, Ltd.

- Christensen, T. (2012). Post-NPM and changing public governance. Meiji Journal of Political Science and Economics, 1(1), 1–11. http://153.122.154.161/articles/files/01-01/01-01.pdf

- Dal Molin, M., Turri, M., & Agasisti, T. (2017). New public management reforms in the Italian universities: Managerial tools, accountability mechanisms or simply compliance? International Journal of Public Administration, 40(3), 256–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1107737

- De Boer, H. F., Enders, J., & Leysite, L. (2007). Public sector reform in Dutch higher education: The organizational transformation of the university. Public Administration, 85(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00632.x

- De Boer, H. F., Enders, J., & Schimank, U. (2008). Comparing higher education governance systems in four European countries N.C. Soguel & P. Jaccard, (Eds.) . In Governance and performance of education systems(pp. 35-54). Springer 35–54 .

- De Boer, H., & File, J. (2009). Higher education governance reforms across Europe. Brussels: ESMU.

- De Vries, M., & Nemec, J. (2013). Public sector reform: An overview of recent literature and research on NPM and alternative paths. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 26(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551311293408

- Deem, R., Hillyard, S., & Reed, M. (2007). Knowledge, higher education, and the new managerialism: The changing management of UK universities. Oxford University Press.

- Dobbins, M., Knill, C., & Vögtle, E. M. (2011). An analytical framework for the cross-country comparison of higher education governance. Higher Education, 62(5), 665–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9412-4

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2006). New public management is dead—long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Evers, A., & Laville, J. (Eds.). (2004). The third sector in Europe. Edward Elgar.

- Ferlie, E., Musselin, C., & Andresani, G. (2008). The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. Higher Education, 56(3), 325–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9125-5

- Frølich, N. (2011). Implementation of new public management in Norwegian Universities. European Journal of Education, 40(2), 223–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2005.00221.x

- Halligan, J. (2007). Reintegrating Government in Third Generation Reforms of Australia and New Zealand. Public Policy and Administration, 22(2), 217–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076707075899

- Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education: The battle for world-class excellence. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Healey-Etten, V., & Sharp, S. (2010). Teaching undergraduates how to do an in-depth interview: A teaching note with 12 handy tips. Teaching Sociology, 38(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X10364010

- Jongbloed, B.W.A. (2005). Characteristics of the higher education system. Supporting the contribution of higher education institutes to regional development. In I., Sijgers, M. Hammer, W. ter Horst, P. Nieuwenhuis, and P. van der Sijde, (Eds.), Self-evaluation report of Twente (p. 11–22). OECD/IMHE.

- Jongbloed, B. (2015). Universities as hybrid organizations: Trends, drivers, and challenges for the European university. International Studies of Management & Organization, 45(3), 207–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2015.1006027

- Kehm, B. M., & Stensaker, B. Eds. (2009). University rankings, diversity, and the new landscape of higher education (pp. VII–XIX). Sense Publishers.

- Louise Barriball, K., & While, A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi‐structured interview: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(2), 328–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01088.x

- Maassen, P. (2017). The university’s governance paradox. Higher Education Quarterly, 71(3), 290–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12125

- Maassen, P. (2012). System diversity in European higher education. In M. Kwiek & A. Kurkiewicz (Eds.), The modernisation of European universities (pp. 79–96). Peter Lang Verlag.

- Mair, J., Mayer, J., & Lutz, E. (2015). Navigating institutional plurality: Organizational governance in hybrid organizations. Organization Studies, 36(6), 713–739. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615580007

- Mergoni, A., & De Witte, K. (2021). Policy evaluation and efficiency: A systematic literature review. In International transactions in operational research. In Press.

- Mintrom, M., & Luetjens, J. (2017). Creating public value: Tightening connections between policy design and public management. Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 170–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12116

- Morris, H. (2011). Rankings and the reshaping of higher education: The battle for world class excellence. Studies in Higher Education, 36(6), 741–742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.617636

- Muyters, G., Quanten, E., Broucker, B., De Witte, K., & Martens, P. (2018). Governancemodellen voor lerarenopleidingen met meerdere aanbieders. Tijdschrift Voor Onderwijsrecht En Onderwijsbeleid, 2018(1), 91–101.

- Nõmm, K., & Randma-Liiv, T. (2012). Performance measurement and performance information in new democracies. A study of the Estonian central government. Public Management Review, 14(7), 859–879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.657835

- Osborne, S. P. (2006). The new public governance?

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public management reform: An international comparison. Oxford University Press.

- Pusser, B., & Marginson, S. (2013). University rankings in critical perspective. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(4), 544–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2013.0022

- Rowe, & Wright, G. (2001). Expert opinions in forecasting. Role of the Delphi technique. In Armstrong (Ed.), Principles of forecasting: A handbook of researchers and practitioners. Kluwer Academic Publishers 125–144 .

- Rutherford, A., & Rabovsky, T. (2014). Evaluating impacts of performance funding policies on student outcomes in higher education. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 655(1), 185–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214541048

- Shattock, M. (2008). The change from private to public governance of British higher education: Its consequences for higher education policy making 1980–2006. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(3), 181–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00392.x

- Simons, H. (2014). Case study research: In-depth understanding in context. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

- Singh, M. (2001). Reinserting the ‘public good’ into higher education transformation. Kagisano Higher Education Discussion Series, 1, 8–18.

- Tahar, S., Niemeyer, C., & Boutellier, R. (2011). Transferral of business management concepts to universities as ambidextrous organisations. Tertiary Education and Management, 17(4), 289–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2011.589536

- Talbot, C. (2008a). Competing public values and performance. In KPMG, CAPM, IPAA and IPAC Holy grail or achievable quest—International perspectives on public sector performance management. KPMG 141–152 .

- Talbot, C. (2008b). Measuring public value—a competing values approach. The Work Foundation.

- Taylor, J. (2009). Strengthening the link between performance measurement and decision-making. Public Administration, 87(4), 853–871. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01788.x

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801–843. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

- Torfing, J., & Triantafillou, P. (2013). What’s in a name? Grasping new public governance as a political-administrative system. International Review of Public Administration, 18(2), 9–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805250

- Try, D., & Radnor, Z. (2007). Developing an understanding of results-based management through public value theory. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 20(7), 655–673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550710823542

- van der Wal, Z., van Hout, E., & Th, J. (2009). Is public value pluralism paramount? The intrinsic multiplicity and hybridity of public values. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 220–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732681

- van Vught, F., & Westerheijden, D. F. (2012). Multidimensional ranking: A new transparency tool for higher education and research. Higher Education Management and Policy, 22(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-22-5km32wkjhf24

- Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research. Sage.

Appendix

Annex 1: Interview Questions (round 1)

The interview structure for the first round of interviews is built on the basis of a literature review. During this desk research stage, special attention was given to the output of the ministerial expert groups that had been organised.

Questions for Director level respondents

(1) We situate the research project, its goals and partners and the status quo.

(2) What are the existing cooperation agreements (which have to be taken into account in the teacher training reform)?

(3) With respect to non-generation students: what is your

(I) View vis-à-vis the realisation of this program?

(II) View vis-à-vis the organisation of educative masters at universities?

(III) View vis-à-vis the organisation of the trajectory for non-generation students at level 7 (on the basis of the acknowledgement of earlier obtained qualifications)?

(IV) View vis-à-vis the organisation of the trajectory for non-generation students at level 6?

(V) View vis-à-vis the different mastering levels?

(VI) Conditions and opportunities

(4) With respect to integration and cooperation: what is your

(I) View vis-à-vis integration (competences of teacher trainings of CAE’s towards …) – with opportunities and conditions

(II) View vis-à-vis cooperation between partners [no cooperation – loose network – institutionalised structural cooperation structure – with opportunities and conditions]

(III) Daily on-campus steering of teacher training and interaction with other locations

(IV) Staff and payroll

(B) Questions for respondents who are program responsible

(1) We situate the research project, its goals and partners and the status quo.

(2) What are the existing cooperation agreements (which have to be taken into account in the teacher training reform – remark: more elaborate compared to A))

(I) Current cooperation projects

(II) Curriculum/different trajectories

(III) Quality assurance

(IV) Learning environment

(VI) Student guidance

(3) With respect to non-generation students: what is your

(VII) View vis-à-vis the realisation of this trajectory

(VIII) View vis-à-vis the organisation of educative masters at universities

(IX) View vis-à-vis the organisation of the trajectory for non-generation students at level 7 (on the basis of the acknowledgement of earlier obtained qualifications)

(X) View vis-à-vis the organisation of the trajectory for non-generation students at level 6

(XI) View vis-à-vis the different mastering levels

(XII) Conditions and opportunities

(4) With respect to integration and cooperation: what is your

(V) View vis-à-vis integration (competences of teacher trainings of CAE’s towards …) – with opportunities and conditions

(VI) View vis-à-vis cooperation between partners [no cooperation – loose network – institutionalised structural cooperation structure – with opportunities and conditions]

(VII) Daily on-campus steering of teacher training and interaction with other locations

(VIII) Staff and payroll

Annex 2:

Coding Scheme/Process Information of Interview Round 1

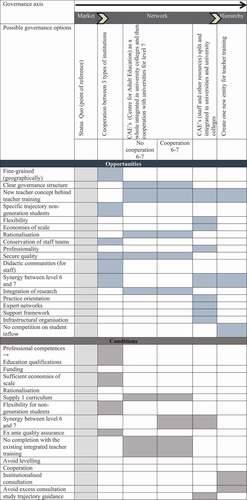

The table below summarises the information gathered through the first interview round. Six overarching governance models were mentioned. These can be linked to the insights from our literature review and benchmark study. It is visualised by placing the 6 models on the governance axis. Furthermore the opportunities and conditions that where explicitly mentioned are shown in the grid.

Annex 3:

Interview questions (round 2)

General (overarching):

(1) If there will be no cooperation:

What are the advantages?

What are the disadvantages, bottlenecks and how can be dealt with these?

(2) On the other side of the continuum one can find common study programmes. Which programmes are possible/desirable in your opinion?

(3) Cooperation in case of shared study programmes. Which topics are suitable to establish cooperation? (see list above)

(4) Concerning the trajectory for non-generation students, do you prefer to organise contact moments during the evening/weekend?

Staff

(5) Would you prefer a situation in which (the staff teams and resources of) CEA teacher trainings - which will be dissolved - are treated as a whole in each geographical region when concluding integration agreements?

(6) Would you prefer a situation in which personal costs are distributed proportionally according to number of students (at level 6 and level 7)?

(7) How would you prefer to organise the division of the staff acquisition?

Funding

(8) Do you prefer a situation in which the fractional division that will be included in the framework agreement would be based on the relative personal costs or rather on the estimated student distribution (across HEI)?

(9) Given the ex-ante uncertainty on the future student distribution (on which the financial distribution of public funding is based), compensation measures for a possible disequilibrium with personal costs are generally accepted. Would you prefer a situation in which these compensations are organised by making available staff members and/or by redistributing financial resources between HEI?

(10) Should cooperation structures be dealt with in an ex-post agreement – after the integration of CEA teacher trainings in universities (for study programmes at level 7) and university colleges (for study programmes at level 6) has been concluded upon?

(11) On cooperation, what are the desired parameters?

Infrastructure - Buildings

Specific for regions where CEA’s does not have own infrastructure. Is it desirable that

(12) Current infrastructure will be used by the future study programmes?

(13) That HEI use their own infrastructure/location (whereby the link with the domain masters or integrated teacher trainings will be maximised)?

(14) For institutions that offer multiple study programmes, is the goal to organise the supply for non-generation students as a whole (e.g., on one campus, for the different programmes)?

Didactical resources

(15) What are (dis)advantages concerning the use of didactical resources (e.g., learning platforms, libraries, database access) with different cooperation models?

Quality assurance

(16) What is the best way to organise quality assurance in function of the four cooperation models? What are in each case the opportunities and challenges?

(17) Is cross-level cooperation with regard to students possible/desirable? (Never – Only if it could be established that differences between levels is not important (and thus where a separated evaluation would not be necessary) – Also where differences between levels is important)

Given that level differences are important, how can is can the quality be assured at each level?

Is a separated evaluation necessary?