ABSTRACT

The field of career development has been focused on one-to-one practice but recent years have seen a growth in the need for alternative approaches that are more effective at challenging inequality. Collective group-based models have been identified as addressing this need but little attention has been paid to developing group coaching in the literature. The collective career coaching approach, which is underpinned by a critical pedagogical theoretical base, is introduced in this article and it is proposed that this model is able to contribute toward steering the focus of career guidance practice toward the advancement of social justice.

Introduction

Career guidance, counseling and coaching practice over the years has predominantly been delivered on a one-to-one basis and focused on the development of practitioner-client relationship to facilitate growth at an individual level. Although group practice has often run in parallel to one-to-one interventions, little attention has been paid to it in the career development literature and it is often seen as a support activity (DiFabio & Maree, Citation2012; Lehman et al., Citation2015; Meldrum, Citation2017; Thomsen, Citation2012; Westergaard, Citation2013). Attempts to move group work to the forefront of practice have often been met with resistance and skepticism and promoted by policy makers as an efficiency saving rather than an innovation to practice.

However, an emerging interest in group career guidance is now becoming evident in the field to challenge not so much the resource heavy nature of the one-to-one interventions but the collective empowerment and social justice potential of group work (Hooley & Sultana, Citation2016; Thomsen, Citation2012). Peoples’ life chances are not equal and the personal agency approach which one-to-one models of practice rely on does not easily address the inequality of opportunity, multiple barriers and oppression which different social groups face (Hooley & Sultana, Citation2016; Irving & Malik, Citation2004; Watts, Citation2015). In addition there is a concern that one-to-one approaches perpetuate an unintentional outcome of career guidance as serving individuals to passively accept the status quo rather than empowering learners to challenge and address power imbalances and inequalities (Bengtsson, Citation2018; Hooley et al., Citation2017; Irving, Citation2018).

This article will introduce a group approach which uses a coaching structure underpinned with a critical pedagogy theoretical base. Critical pedagogy as an approach will be shown as having the potential to act as a vehicle to help groups contextualize their learning into the wider community and socio-economic perspectives (Blustein, Citation1987). Such an approach will see the career practitioner taking on the role of a community worker or facilitator rather than an expert. The group will be guided toward the collection of meaningful interactions in order to make sense of their place in the world before changing it (Hooley et al., Citation2018). It will be shown how such an approach has the potential to act as a model of practice to steer the focus of career guidance practice toward collective empowerment and the advancement of social justice.

Making a Case for a Group Critical Pedagogical Approach

Critical pedagogy is a philosophy, social movement, educational approach and a praxis which has developed from applied concepts from critical theory and education. It is grounded in a critical theory epistemology or worldview which proposes that, in contrast to traditional theory which focuses on understanding and making meaning of society, there should instead be a focus on critiquing and changing society as a whole.

Critical theory attempts to challenge how knowledge is acquired, the deep-seated assumptions in society, power domination and the accepting of the status quo in order to gain a fuller picture of how the world operates before offering solutions for change (Thompson, Citation2017).

Critical pedagogy has been progressed in the educational field from the ideas and teachings of Freire (Citation1970) in Pedagogy of the Oppressed. He rejects what he calls the “banking model” of teaching in which the content of the learning (or the knowledge) is absolute, static and predictable. This knowledge is “deposited” or passed on to the learners by the teacher. The learners are in effect “empty vessels” who, over the course of their studies, have their “containers” filled with this knowledge. The learners are often expected to passively accept the validity and relevance of this knowledge to their life with little opportunity to question. The acquisition of knowledge is the primary goal in such learning and the more knowledge the students gain, the better the teaching is viewed. This leads to communities of learners and, he argues, societies of learners being stuck in continuous cycles of learning which lacks adequate opportunities to challenge its validity. This in turn perpetuates oppression and inequalities and diminishes chances for change and emancipation.

Freire proposed that learning instead should be seen as a largely political act with social justice aims and that the pursuit of knowledge as the primary goal should be rejected. This shift in focus toward empowerment and social change is achieved by a process of what Freire terms as an “awakening of critical consciousness”. He proposed a co-operative practitioner-student educative model which involves engaging learners in an active process of “collective dialogue, reflection and action in order to learn to perceive social, political and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” (Freire, Citation1970, p. 60). According to Young (Citation2004) there are five “faces” or types of oppression, namely exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, violence and cultural imperialism. Different groups may face one, several or all types of oppression at any one time or over the lifespan.

Theoretical approaches based on critical pedagogical perspectives and developed by leading scholars in the field (such as Giroux, Citation2011; McLaren, Citation2006; Simon, Citation1992; Hooks, Citation2003; Chomsky, Citation2010) have been prevalent for a number of years in a range of disciplines including teaching, adult education, social work and counseling. Models have been adapted from such theoretical perspectives which aim to steer learning toward the pursuit of social justice. Such models of practice, usually in groups, often involve a psychosocial process where practitioners take on the role of a facilitator rather than an expert in order to empower learners.

This has not been mirrored to the same extent in the field of career guidance and development practice. This is despite the literature making a call for approaches which address the concern that people’s life, learning and work opportunities are affected by wider cultural and community influences and power struggles. Or, as Hooley and Sultana (Citation2016, p. 2) put it, approaches which are “socially transformative and emancipatory rather than reproductive and oppressive”.

To make a claim that career guidance policy, research and practice has not been rooted with social justice aims would be erroneous though. Since the origins of the field over a hundred years ago, a tradition of social justice has prevailed (Irving & Malik, Citation2004). However, in the changing landscape of neo-liberalism and “boundaryless” careers (Arthur & Rousseau, Citation1996), this is becoming an increasingly difficult intent to fulfil. According to Hooley and Sultana “If career guidance is to formulate a meaningful response to social injustice it needs to draw on diverse theoretical traditions and stimulate new forms of practice” (Hooley & Sultana, Citation2016, p. 2).

In terms of drawing on diverse theoretical perspectives there has been some progress made over the last few years in the career guidance literature. Critical pedagogy itself has been considered by a range of academics including Da Silva et al. (Citation2016), Olle (Citation2018), Sultana (Citation2014, Citation2017) and Blustein et al. (Citation2005). Da Silvia, Paiva and Ribeiro challenge traditional one-to-one career guidance, counseling and coaching theories and practices and instead consider alterative group approaches which are able to nurture the building up of collective relationships. The career practitioner takes on the role of a “communal worker”, intermediary or facilitator rather than an expert and guides the learners toward the collection of a “web of meaningful interactions” in order to make sense of their place in the world before changing it. The interventions are intended to be psychosocial in nature and there is a focus on the peer support and social bonds that can be built up during the process.

Less attention has been paid to how such theoretical models could be applied to practice and guidance practitioners are often reluctant to face the difficult task of attempting to incorporate such theory and techniques into every day guidance interactions. As the emancipatory practices explored above are often group-based practices, it could be argued that the focus on one-to-one delivery in the career guidance sector could be a possible reason for this. In other words practitioners may find it difficult to apply such models to their practice as they fit better with group work practice.

This is amplified by the lack of literature relating to group work in the field of career guidance literature. Group work is, in effect, under researched and under developed and a lack of attention has been paid to developing models of practice (DiFabio & Maree, Citation2012; Meldrum, Citation2017; Offer, Citation2001; Thomsen, Citation2012; Westergaard, Citation2013). This has in practice led to career guidance in groups being predominately focused on the passive provision of information and the sharing of knowledge rather offering a space for an active, empowering co-learning approach which group work should foster.

Lehman et al. (Citation2015) discuss group work in the careers field as potentially being able to offer the opportunity to raise critical consciousness and change attitudes. This could be possible by the facilitator offering a space for the individuals to share problems with the rest of the group, the fostering of co-operation rather than competition within the group and the encouragement of the group to take collective responsibility to make decisions, raise issues and address change. Groups in effect would have the potential to facilitate the exploration and construction of their collective career stories and contextualize this into wider community and socio-economic perspectives (Blustein, Citation1987).

The collective career coaching approach will now be considered as model of practice which, it will be argued, has the potential to fill a gap in transformative group-based practice models in the field. It will consider whether it has the potential to act as a model of practice to empower groups of learners to collectively challenge power imbalances and inequalities. It will further propose that it can contribute toward steering the focus of career guidance practice toward the advancement of social justice.

The Collective Career Coaching Model

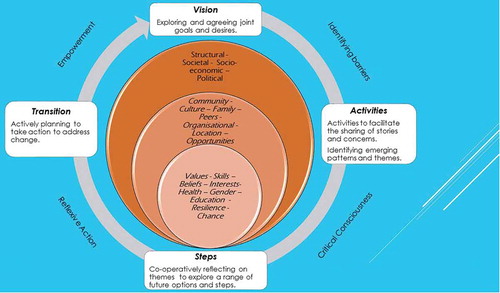

The collective career coaching model, which has been adapted from the Group Integrative Narrative Approach (Meldrum, Citation2017) was developed by the author over a number of years based on observations, research, reflections and practice made initially as a guidance practitioner and later as an educator and researcher in the field of career guidance and development. The model is illustrated in .

The model, grounded in critical theory, is a psychoeducational group approach (Corey, Citation1981) which has the aim of transforming the career development and life options of the group. It is underpinned by a critical pedagogical learning base (Freire, Citation1970) and Systems Theory Framework (Patton & McMahon, Citation1999). It uses a counseling and coaching structure based on a number of models such a person centered counseling (Rogers, Citation1961), life design career counseling (Savickas, Citation2012), career guidance (Kidd, Citation2006) and career coaching (Whitmore, Citation2002; Yates, Citation2014). It is therefore an integrative approach (Westwood & Ewasiw, Citation2011) which, although in their infancy within the fields of career development group work, is commonplace in the wider field of group counseling. The collective career coaching model is explained in more detail below.

At the heart of the model in , the wide range of factors illustrated are interrelated and connected and are based on the micro, meso and macro factors of the Systems Theory Framework (Patton & McMahon, Citation1999). Traditionally, there has been a predominant focus on factors which affect career development at the individual level such as values, interests and education and matching these factors to particular job or industrial roles or fields. Such approaches are based on person-environment fit career development theories, such as Holland (Citation1985) and they continue to significantly influence career guidance practice. However, the wider influence of social factors made at the community level such as family, peer groups and neighborhoods, workplace cultures, geographical location (such as urban or rural environment) on career development have been considered by Law (Citation1981), Hodkinson (Citation1997), and Roberts (Citation1977) considers the wider still macro level influences such as socio-economic and political factors, which have the potential to both develop and also limit future options and pathways. The Systems Theory Framework (STF) brings such factors together as an “interrelated and correlated system which is dynamic and recursive” (McMahon & Patton, Citation2016).

The STF is a constructivist model of career development which considers such micro, meso and macro factors being influenced by past, present and future knowledge, experiences, events and emotions. A constructivist philosophical viewpoint sees this process as dynamic and developed over time through the building up of patterns, connections and threads to form broader themes to make sense or “meaning”’ of the world. The STF considers such patterns and themes as being recursive in nature and constantly challenged, broken down and rebuilt through ongoing chance events, interactions with others and adapting to circumstances out with one’s control.

The constructivist philosophical standpoint of the STF theory appears to differ from the critical theory basis of the collective career coaching approach. The goal of interventions is to facilitate the growth and development of the group members in a constructivist approach and relies on the personal agency or autonomy of the group participants to achieve this aim. A critical pedagogical approach, grounded in critical theory, has the primary goal of challenging the status quo to address power imbalances and inequalities in order to facilitate growth. A constructivist approach would stop short of this aim but this does not mean that the two approaches contradict each other or that they could not run in parallel with each other.

This has been attempted in the career guidance literature by Da Silva et al. (Citation2016), discussed earlier, who consider South American epistemologies (which includes a critical pedagogical approach) reviewed through the lens of constructivist perspectives as being able to address social injustice in order to facilitate growth.

This can be applied to the Collective Career Coaching Approach by exploring the wide range of micro, meso and macro STF factors from a constructivist perspective. This approach offers space for the group to support each other through the building up meaningful exchanges in order to construct and deconstruct stories and shared experiences. This would enable the group to form patterns, connections and threads between their stories and in turn identify themes in order to re-author or retell different stories to facilitate growth.

This is taken a stage further through the lens of a critical pedagogical learning theory. As illustrated in the outside ring of the Collective Career Coaching Approach in , after identifying goals for the session, the facilitator would guide the group to identify a range of barriers, inequalities or oppression they have encountered as a group as they tell their stories. Rather than accept or adapt to the oppression that a constructivist approach would unintentionally encourage, using a critical pedagogical approach, the facilitator would instead encourage the group to develop their level of critical consciousness. In other words the group would be given space to identify, challenge and critique oppression through different activities and group discussions.

During the next two stages the group would be encouraged to reflect on themes arising from the discussions to actively and collectively empower the group to take action to address change. There is no final stage of the model and it is proposed that it can teach the group to be engaged in a continuous, endless cycle of learning. The learning, which would involve cycles of collective discussion, reflection and action is, in effect, intended to build up and awaken the learners to social, political and economic inconsistencies in order to enable them to take collective action against oppression throughout their lifespan (Freire, Citation1970).

The structure of the collective career coaching approach is illustrated in the middle circle of the diagram in . It draws on a number of models from career guidance (Kidd, Citation2006), coaching (Whitmore, Citation2002; Yates, Citation2014) and group guidance (Westergaard, Citation2009). The use of person-centered counseling techniques (Rogers, Citation1961) including the building of a counseling relationship and narrative counseling (Savickas, Citation2012) are implicit within the model. As can be seen, it is steered around four stages – vision, activities, steps and transformation. The structure of the model can be used for both the planning and the delivery of the group work.

The group approach is psychoeducational in delivery style (Corey, Citation1981) which differs from both group counseling (which is unstructured and involves little pre-prepared planning) and traditional classroom or lecture style teaching (which is more structured). Psychoeducational groups are instead semi-structured, involve some planning before the group work takes place and have fairly specific, but fluid goals. There is a common purpose or goal that brings the group together and learners are given ample room to be actively engaged in the learning process throughout. It is able to therefore combine the benefits of group guidance (such as peer support and group learning) with counseling and coaching approach benefits (high quality interpersonal and social interactions) which are usually only possible with one-to-one interactions (Meldrum, Citation2017; Westergaard, Citation2013). Psychoeducational group work in the context of career development for the purpose of collectively empowering learners can be suited to all age populations.

As mentioned earlier, such group work models, although in their infancy in the field of career development, have been commonplace in the wider field of group counseling for a number of years. In addition such relational models are also beginning to be practiced in a range of related educational and career development fields which up until now have relied on almost exclusive use of one-to-one models of practice. An example of this is group mentoring being recently developed in career mentoring in the science, technology, engineering, medicine and mathematics (STEMM) field (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Citation2019).

The Collective Career Coaching Approach presented above may have some limitations in terms of its theoretical base and its application to practice. Using critical pedagogy to challenge power imbalances and inequalities could be uncomfortable and create tensions between career practitioners, organizations and policy makers. Secondly, working in a group may not be suitable for all and some participants could gain more benefit from a group situation than others (Meldrum, Citation2017; Westergaard, Citation2013). This could create a challenge for the practitioner and highlights the need for training in the use of the model. Thirdly, although the model has been used extensively in practice, taught to students undertaking career development training and developed through action research, it has not been extensively empirically tested. It would therefore benefit from further evaluative studies.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations it has been argued that the model has the potential to offer space for learners to build up a collection of meaningful interactions in order to make sense of their place in the world before changing it. This in turn may empower learners to collectively challenge inequality and oppression and further still have the potential to act as a model of practice to steer the focus of career guidance practice toward the advancement of social justice.

Two illustrations of how the collective career coaching model can be applied to every day practice will now be explored in the following case studies.

Case Study One – Short-Term Intensive Support

The author as both a career practitioner and a researcher conducted an action research pilot study (Meldrum, Citation2017) involving the delivery of group career coaching with two separate groups of senior students aged 16 and 17 in two secondary schools in Edinburgh, Scotland. Each group took part in two one-hour sessions as part of this study and the groups were a mix of male and females and of mixed academic achievement levels. All of the students were due to leave school over the next year but were feeling very anxious and had a common concern of being uncertain and undecided as to their future career or study pathways.

The Vision of the groups were agreed and negotiated between-group members and the career practitioner/ group facilitator at the first meeting. Both groups collectively discussed their issues and priorities and were keen to develop a strategy to deal with their pressing career decision-making concerns and to overcome the intense feeling of having a severe lack of control over their future. The group identified as being oppressed due to the powerlessness that they faced over their future.

The groups then took part in Activities which had the purpose of developing the group’s level of critical consciousness through the exploration of the STF micro, meso and macro factors at the heart of the model. The group benefited from the psychosocial support process to draw out common themes of decision-making anxiety, lack of confidence, lack of a voice and pressures to make decisions from family, friends and the school. The facilitator helped the groups question the helplessness they felt when facing their future and the emphasis they placed on blaming themselves for their lack of progress. The focus was turned instead to the collective power of the group to address change.

Activities were continued in the second session and explored with the use of narrative questioning techniques (Savickas, Citation2012) to help each other build narratives and find patterns emerge between a range of experiences and interactions. An example of this involved the group members helping another student who enjoyed “building things and learning how things worked” to explore engineering as an option. The participant later commented -

I would never have thought about computing or engineering or something like that, I would not go into that detail but it was cool and for someone who didn’t know what they wanted to do … it was well interesting as I was able to know what other people were like. The group makes people think about career paths that they hadn’t thought about. (Meldrum, Citation2017, p. 36)

The groups were encouraged to co-operatively work together to co-action plan rather than work individually toward their goals or Steps. The learners were involved in collectively researching others career and/ or educational course goals. This had the dual purpose of widening the horizons of the learners as well as developing the process of building their collective career management skills.

At the Transition stage the learners were encouraged to consider the wider collective empowerment goals of the group. The group worked together to arrange to contact employers and organize work experience opportunities for each other. In addition, with the support of the career practitioner, the group members approached the school leadership team to negotiate embedding this collective career coaching model into the guidance support services within the school.

In summary the Collective Career Coaching Approach in the above case study was effective at helping groups of young people overcome the sense of powerlessness they felt when facing their future. The approach, in just two sessions, was able to use a critical pedagogical psychoeducational support process to empower the groups to take collective action to address change. This learning process has the potential to be enhanced and embedded throughout the learner’s lifespan with a longer term engagement with the process. This is explored further in case study two.

Case Study Two – Long-Term Programme of Interventions

A career development practitioner working for an economic development charity in an economically disadvantaged area of south west of Scotland brought together 10 unemployed local residents of the area. All were adults aged between twenty-five and fifty, were unemployed for over 2 years and faced multiple barriers to employment. These barriers varied from person to person but always included long-term poverty, isolation and lack of support networks. Some were also facing or overcoming long-term health issues, lack of childcare, drug or alcohol issues or domestic abuse.

An initial group session with the career development practitioner (who acted as the group facilitator) identified that the group members had the common goal of being committed to find work but wanted to address and overcome the discrimination they faced when prospective employers learned of their area of residence. The group was able to name the oppression as marginalization. Many of the group expressed an interest in working in the retail sector and had repeatedly applied to work in the local supermarket without success. The group agreed that they would meet up for an hour on a twice weekly basis to address these issues and find suitable employment, ideally in retail, within a 2-month period. This represented the Vision stage of the Collective Career Coaching model in .

This was followed by the Activity stage of the model and involved the facilitator working through a series of learning activities with the group over the course of a few weeks to “awaken” the group’s critical consciousness. In other words, the group was firstly given space to collectively discuss the barriers, issues, power imbalances and oppression that limited their ability to progress in a greater amount of depth. Secondly, using visual representations of the wide range of micro, meso and macro factors from STF (Patton & McMahon, Citation1999) the group took part in a series of activities to consider how such factors have affected their lack of progress over the years. Thirdly the facilitator helped the group discuss how much control the group had of influencing such factors at an individual and at a collective level and consider how to break the cycle of helplessness that they felt. Finally the group were able to work together to collectively consider strategies to challenge and overcome such power imbalances and inequality.

In the Steps stage of the model the group identified that they would speak to management in the local supermarket to consider how they could address change. This involved the facilitator and two members of the group arranging a meeting with the human resource department in the supermarket to address concerns. During this meeting supermarket management discussed their recruitment practices and agreed that they had low numbers of people applying, being successful at interview and subsequently sustaining work from the local area. Management also raised concerns relating to poorly completed application forms and, at the interview stage, local applicants had a tendency to display poor evidence of the required base line customer service skills. Both parties were keen to address these issues and the supermarket was keen to employ local people. Management agreed to work with the economic development charity to develop a strategy with a view to offering each of the group members a job interview.

The career development practitioner subsequently wrote a briefing paper to management within the economic development charity, asking that the group be given the opportunity to take part in a short course to develop their customer service skills. The career development practitioner also agreed to work with the group to develop job interview skills. The management agreed to this proposal and identified a local college to provide the customer service training. A written agreement was taken to the supermarket who consented in writing to interview group members who completed both the customer service and interview training. In addition the supermarket looked at reviewing their recruitment and training practices. This included more inclusive interview techniques and the offer of a two week extended period of customer service training, with one-to-one mentor support to improve the retention levels.

The Transition stage of the collective career coaching model was reached after a 3-month period of support involving further group career coaching, interview skills and customer support training. At this time, nine of the participants were offered a job interview with the supermarket and five were successful in securing employment. A further three were subsequently successful in securing a job a short time later with another local supermarket.

Additional group career coaching sessions continued for a further 6 months to support the employees with their ongoing development. The employees expressed the same concerns with finding and sustaining work as before, such as child care issues affecting attendance and health issues having an impact on the hours of work. However, through the support and collaboration with their peers and the career development practitioner, they were able to work through these issues and subsequently felt less marginalized. One member of the group took on the role of the liaison member between the new employees and the management and negotiated flexible work patterns as well as assisting in the recruitment of a further group of local residents.

In summary the collective career coaching model in the above case study was delivered to a group of marginalized long-term unemployed adults in an economically disadvantaged community and was effective at helping the group break the cycle of oppression that they faced in finding work. The process, over a long-term period of interventions, was able to build up and awaken the group to social, political and economic barriers and inequalities and take collective action to overcome the oppression. This learning process has the potential to continue to influence the group’s career development opportunities throughout their lifespan.

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

It has been argued within this article that traditional one-to-one approaches to practice in the career development sector unintentionally reenforce continuous cycles of inequality by relying on the personal agency of individuals rather than the collective voice of groups. Alternative approaches to the long-term focus on one-to-one interventions were therefore called for and were seen to have the potential to steer practice away from personal growth and development outcomes toward group empowerment and social justice aims.

Despite a growing movement within the sector to support alternative group-based approaches, there remains to be a gap in practice-based models to support career development practitioners in every day practice. The collective career coaching approach was introduced as a practice-based model and was illustrated through case studies. The model was able to apply a pedagogical theoretical base to offer the potential to empower groups of learners to collectively challenge power imbalances and inequalities and in turn contribute to the ongoing development of social justice aims.

Going forward, there is a need within the sector to continue to support and develop such collective approaches to practice at a research, practitioner and policy level. At the research level there is a need for robust evaluations of such models to offer strong empirical evidence of their effectiveness. Such models continue to be taught during initial career development training programs and there is a need for practitioners to continue to put this learning into practice. At the policy level it is important to have ongoing dialog with policy makers to support and develop such ongoing and developing practices.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues at Edinburgh Napier University, particularly Peter Robertson and Sheena Travis for their words of support and for encouraging me to write this article. I would also like to thank past and current students undertaking the Post Graduate Diploma in Career Guidance and Development who were involved in the research, training and development of the collective career coaching model.

Finally I would like to thank my husband, Andrew, for his ongoing patience and support and for proof reading the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susan Meldrum

Susan Meldrum is Programme Leader and Lecturer in Career Guidance and Development in the School of Applied Sciences at Edinburgh Napier University.

References

- Arthur, M. B., & Rousseau, D. M. (1996). The boundaryless career. Oxford University Press.

- Bengtsson, A. (2018). Rethinking social justice, equality and emancipation: An invitation to attentive career guidance in in career guidance for social justice. In T. Hooley, R. J. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for emancipation, reclaiming justice for the multitude (pp. 255–268). Routledge.

- Blustein, D. L. (1987). Integrating career counseling and psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 24(4), 794–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085781

- Blustein, D. L., McWhirter, E. H., & Perry, C. (2005). An emancipatory communitarian approach to vocational development theory. Research and Practice, the Counselling Psychologist, 33(22), 141–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000004272268

- Chomsky, N. (2010). Hopes and prospects. Haymarket Books.

- Corey, G. (1981). Theory and practice of group counselling. Brooks/Cole.

- Da Silva, F. F., Paiva, V., & Ribeiro, M. A. (2016). Career construction and reduction of psychosocial vulnerability: Intercultural career guidance based on southern epistemologies. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 36(1), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.3606

- DiFabio, A., & Maree, G. (2012). Group-Based life design counselling in an Italian context. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.06.001

- Freire, P. R. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Classics.

- Giroux, H. A. (2011). On critical pedagogy. Bloomsbury.

- Hodkinson, P. (1997). Careership: A sociological theory of career decision making. British Journal of the Sociology of Education, 18(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569970180102

- Holland, J. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Prentice-Hall.

- Hooks, B. (2003). Teaching the community: A pedagogy of hope. Routledge.

- Hooley, T., Sultana, R. J., & Thomsen, R. (2018). Representing problems, imagining solutions, emancipatory career guidance for the multitude. In T. Hooley, R. J. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for emancipation, reclaiming justice for the multitude (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

- Hooley, T., & Sultana, R. G. (2016). Career guidance for social justice. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 36(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.3601

- Hooley, T., Sultana, R. J., & Thomsen, R. (2017). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In T. Hooley, R. J. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 1–28). Routledge.

- Irving, B. A. (2018). The pervasive influence of neoliberalism on policy guidance discourses in career/ education: Delimiting the boundaries of social justice in New Zealand in career guidance in career guidance for social justice. (Hooley, Sultana and Thomsen, Eds.). Routledge.

- Irving, B. A., & Malik, B. (2004). Critical reflections on career education and guidance: Promoting social justice within a global economy. Routledge.

- Kidd, J. M. (2006). Understanding career counselling: Theory, research and practice. Sage.

- Law, B. (1981). Community interaction: A “Mid-Range” focus for theories of career development in young adults. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 9(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069888108258210

- Lehman, Y. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Uvaldo, M. C., & Da Silva, F. F. (2015). A psychodynamic approach on group career counselling: A Brazilian experience of 40 years. International Journal of Educational and Vocational Guidance, 15(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-014-9276-0

- McLaren, P. (2006). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy. Alkin and Boacon.

- McMahon, M., & Patton, W. (2016). The systems theory framework: A conceptual and practical map for story telling. In M. McMahon & W. Patton (Eds.), Career counselling: Constructivist approaches (pp. 113–126). Routledge.

- Meldrum, S. C. (2017). Group guidance- is it time to flock together? Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 38(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.3806

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2019). The science of effective mentorship in STEMM. The National Academies Press.

- Offer, M. (2001). Career guidance in a group context. In B. Gothard, P. Mignot, M. Offer, & M. Ruff (Eds.), Career guidance in context, (pp. 59–76). SAGE.

- Olle, C. D. (2018). Exploring politics at the intersection of critical psychology in career guidance in career guidance for social justice. In T. Hooley, R. J. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds), Career guidance for emancipation, reclaiming justice for the multitude (pp. 159–176). Routledge.

- Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (1999). Career development and systems theory: A new relationship. Brooks/Cole.

- Roberts, K. (1977). The social conditions, consequences and limitations of careers guidance. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069887708258093

- Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: The person-centered approach. Harper Row.

- Savickas, M. L. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. Journal of Counselling and Development, 90(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00002.x

- Simon, R. (1992). Teaching against the grain: Texts for a pedagogy of possibility, critical studies in education and culture. Bergin and Garvey.

- Sultana, R. G. (2014). Rousseau’s chains: Striving for greater social justice through emancipatory career guidance. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 33(1), 15–23.

- Sultana, R. G. (2017). Precarity, austerity and the social contract in a liquid world. In T. Hooley, R. J. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp. 63–76). Routledge.

- Thompson, M. (2017). The palgrave handbook of critical theory. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Thomsen, R. (2012). Career guidance in communities. Aarhus University Press.

- Watts, A. G. (2015). The impact of the ‘New Right’: Policy challenges confronting career guidance in England and Wales. In T. Hooley & L. Barham (Eds.), Career development policy and practice: The Tony Watts Reader (pp. 205–220). Highflyers.

- Westergaard, J. (2009). Effective group work with young people. McGraw Hill Education.

- Westergaard, J. (2013). Group work: Pleasure or pain? An effective guidance activity or a poor substitute for one-to-one interactions with young people. International Journal for Education and Vocational Guidance, 13(3), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-013-9249-8

- Westwood, M. J., & Ewasiw, J. F. (2011). Integrating narrative and action processes in group counseling practice: A multimodal approach for helping clients. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 36(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2010.537738

- Whitmore, J. (2002). Coaching for Performance. Nicolas Brealey.

- Yates, J. (2014). Career coaching handbook. Routledge.

- Young, I. (2004). Five faces of oppression. In L. Heldke, & P. O'Connor (Eds.), Oppression, privilege, & resistance (pp. 37–63). McGraw Hill.