Abstract

Aims

Pediatric occupational and physical therapy service delivery via telehealth increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Real-world experience can guide service improvement. This study explored experiences, barriers, and facilitators of initial telehealth implementation from the therapist’s perspective.

Methods

Qualitative descriptive approach. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with occupational therapists (n = 4) and physical therapists (n = 4) between May-June 2020. Interviews were recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Data were coded inductively to generate themes, then re-coded deductively to classify barriers and facilitators to telehealth acceptance and use using the Unified Technology Acceptance Theory.

Results

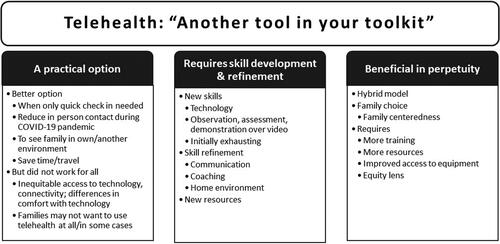

Participants had 16.5 [(2-35); median (range)] years of experience (3 months with telehealth) and predominantly worked with preschool children. Three themes about telehealth were identified: a practical option; requires skill development and refinement; beneficial in perpetuity. Most frequently cited barriers were the lack of opportunity for ‘hands-on’ assessment/intervention and the learning curve required. Most frequently cited facilitators included seeing a child in their own environment, attendance may be easier for some families, and families’ perception that telehealth was useful.

Conclusion

Despite rapid implementation, therapists largely described telehealth as a positive experience. Telehealth facilitated continued service provision and was perceived as relevant post-pandemic. Additional training and ensuring equitable access to services are priorities as telehealth delivery evolves.

Early in 2020, healthcare organizations and service providers had to rapidly adjust how services were provided to limit the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), while ensuring safe and continued access to care. Telehealth presented a potential solution to facilitate continued provision of occupational and physical therapy services (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020; Camden & Silva, Citation2021) while adhering to public health recommendations to decrease the volume of in-person visits where possible. Telehealth leverages the use of phone, and/or online platforms for assessment, consultation, and intervention (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020). This type of healthcare delivery system is an evolving practice in pediatrics and rehabilitation, which has been perceived as promising, but is still viewed with some reservation (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020; Camden & Silva, Citation2021; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2021; Tully et al., Citation2021).

Promising features of telehealth had been identified prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These include potential cost savings for families and healthcare organizations, improved efficiency and accessibility, and improved family-centered care (Herendeen & Deshpande, Citation2014; Tully et al., Citation2021). Costs may be reduced for patients and families through reduced travel time and expenses, time off work, and time taken from school and family routines (Juárez et al., Citation2018; Tully et al., Citation2021). However, advantages must be measured alongside other considerations, including whether families have access to the technology and connectivity needed to participate in telehealth, and whether telehealth further increases healthcare disparities for those who live in rural and remote communities or who experience socioeconomic challenges (Beavis & Flett, Citation2020; Camden & Silva, Citation2021; Gerlach, Citation2018). Other considerations include the potential for reduced in-person contact to have a negative impact on therapeutic relationships (Gerlach, Citation2018; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2021), the suitability or effectiveness of telehealth as a service delivery model for various interventions or conditions, safety concerns, and the desire or willingness of clients and families to participate in this service delivery option (Hines et al., Citation2019).

In addition to these important concerns, implementing technology in healthcare in general is often met with challenges, which is further complicated when the platform needs to adhere to privacy or confidentiality legislation (Herendeen & Deshpande, Citation2014; Sasangohar et al., Citation2018). Collectively, these considerations likely contributed to the low uptake of telehealth within rehabilitation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Camden & Silva, Citation2021). Internationally, telehealth has been considered a viable option to continue to provide services when physical distancing and facility capacity recommendations may otherwise limit access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic (Camden & Silva, Citation2021; Hall et al., Citation2021; Isautier et al., Citation2020). As such, there has been a call for descriptive real-world research that can be integrated into rapid learning cycles to improve our understanding, use, and the long-term effectiveness of this form service delivery in the field of rehabilitation (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020). In their Point of View article, Bettger & Resnik state “Research on real-world practice is imperative to understand the reach and implementation of telerehabilitation and to quantify how much and what types of telerehabilitation are being delivered, to whom, and by whom” (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020). They reflect on how the framework of a Learning Health System can be leveraged to understand and ultimately enhance telehealth service provision (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020). A learning health system combines existing evidence with real world experiences, clinical data, and can draw from multiple perspectives (service providers, patients/families) to learn about care as it is being provided and direct improvements (Budrionis & Bellika, Citation2016). Pragmatic research that is conducted to understand a clinical change as it occurs, within the framework of a learning system, can advance our understanding and use of telehealth in rehabilitation (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020).

In March 2020, options for telehealth were explored, trialed, and rapidly implemented by therapists who worked onsite at an outpatient pediatric rehabilitation facility in Manitoba. Prior to COVID-19, onsite occupational and physical therapists predominantly worked with families in-person, with occasional follow-up via telephone or home visit. Videoconferencing was infrequently used and was only available for use via provincially-sanctioned telehealth providers that required a family to attend a telehealth-equipped health facility. The first cases of COVID-19 in Manitoba were confirmed on March 12, 2020, one day after the World Health Organization announced the COVID-19 pandemic (Ducharme, Citation2020; Province of Manitoba, Citation2020). Therapists were advised soon after to reschedule/postpone upcoming in-person outpatient appointments to comply with public health recommendations. Therapists could remain connected with families via phone, and a limited number of in-person appointments were available for children who would experience significant deterioration if not seen, and for other circumstances such as communication/language barriers that impacted the ability to communicate via phone. Facility-based discussions related to telehealth were initiated the week of March 16, 2020, and rolling implementation began the following week.

In keeping with the call for real-world descriptive research (Bettger & Resnik, Citation2020), the purpose of this project was to explore the experiences, barriers, and facilitators of initial telehealth implementation from the perspective of pediatric occupational and physical therapists who began using telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive approach was used (Bradshaw et al., Citation2017; Neergaard et al., Citation2009; Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010). With roots in nursing and applied health research (Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010), qualitative description is particularly well suited to studies that seek to gain information directly from the people experiencing an event, to understand or describe a process or event, where time or resources are limited (interpreted here as the time and capacity of potential participants for the extra work of research during the initial phases of a pandemic), and for small and clinically-focused studies that take place in the natural setting of the phenomenon (Bradshaw et al., Citation2017; Neergaard et al., Citation2009).

To be eligible to participate, a therapist must have initiated any level of telehealth within their caseload since the start of the pandemic. To gain a majority perspective, target recruitment was set at 6-8 therapists, which represented 55 − 73% percent of eligible therapists working in the center at the time of the study. A maximum variation approach (Sandelowski, Citation1995, Citation2000) was used to aim for recruitment of a near equal or equal number participants from physical and occupational therapy. Recruitment took place between May and June 2020. Therapists were informed of the opportunity to participate in the study through institutional e-mail distribution, and managers were updated on recruitment status (number of participants/profession) in one-to-two-week intervals. Trained physical therapy student researchers conducted semi-structured interviews (Appendix A) with participants.

Procedure

All data were collected by the end of June 2020, coinciding with the end of the first wave of the pandemic in this region. Interviews were conducted and recorded using institutional research ethics board-approved videoconferencing (Zoom for Healthcare). Four student physical therapists (KT, AP, KB, TJ) were trained to conduct, transcribe, and perform preliminary thematic analysis of the interviews to generate initial themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019), overseen by the study lead and qualitative lead of the research team (KW and JP, respectively). Thematic analysis was followed by deductive coding and classification of barriers and facilitators of telehealth acceptance and use. This was conducted by lead researcher (KW) with guidance from qualitative lead (JP).

Student researcher training included virtual group sessions led by JP and supported by KW, to provide an overview of qualitative research methodology, to improve understanding and application of interviewing techniques, and to enable students to generate initial themes from the data during analysis. Group training was supplemented with required readings, provided to students to further enhance their knowledge on interviewing and data analysis techniques. As part of the learning process, students also practiced interviewing one of their student co-researchers with the interview guide, receiving feedback from their partner and a debrief with senior members of the research team prior to interviewing a participant.

Consistent with reflexive thematic analysis principles, the perspectives of the individual researchers were considered individually and discussed as a group in relation to this study (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The student researchers acknowledged their position as individuals who will soon be practicing therapists and may experience use of telehealth in their own practice. The study lead acknowledged their role as a part-time practicing therapist, who began using telehealth during the pandemic. As neither a practicing therapist nor a content expert, the qualitative lead provided methodological guidance, led qualitative training for the students, and supported data analysis.

This study was approved by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS23969 [H2020:255]) and received local site impact approval. A research coordinator received informed consent from all participants prior to their participation.

Data Analysis

Participant demographics were analyzed descriptively using Microsoft Excel. An inductive thematic approach was applied to understand therapists’ experiences of telehealth (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). The following section describes the steps taken to enhance the rigor of data analysis, acknowledging transparent reporting as one aspect of rigor (Tracy, Citation2010). Student researchers independently familiarized themselves with the data through transcription, re-reading, and the creation of initial codes and themes for the therapist interviews that they conducted. Codes and initial themes were then discussed with team members and subsequently refined. Student researchers then re-coded the two interviews that they conducted as well as two additional interviews. Through group discussion with senior researcher guidance, codes were then organized into themes which were further refined through discussion and consensus. Meetings were held approximately bi-weekly during the data analysis phase. Transcripts were re-read and themes were finalized once confirmed by two senior members of the research team (KW, JP) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019).

After thematic coding, transcripts were re-read and re-coded following the principles of directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The goal of this second analysis phase was to ensure that barriers and facilitators to the acceptance and use of telehealth were comprehensively identified and organized in a meaningful way. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) was used as the organizing framework (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). According to the UTAUT, the four main determinants of technology acceptance and use are performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Data were coded deductively, organizing barriers and facilitators by these four categories.

Credibility of qualitative findings was strengthened through providing themes back to participants for discussion during therapist staff meetings. This meeting involved therapists who were involved in the study as well as those who were not. Themes were discussed and confirmed prior to manuscript preparation. An audit trail was maintained by those involved in data analysis.

Results

Participants included four occupational therapists and four physical therapists, with a median of 16.5 years in practice (range: 2-35). Consistent with the mandate of the department, therapist caseloads were primarily dedicated to children ages 0-5 years, who had been referred to occupational or physical therapy for neurodevelopmental-related reasons. This included children with a diagnosis or symptoms suggestive of autism, sensory processing issues, developmental delay, Down Syndrome, or cerebral palsy; as well as infants/children with medical complexity; or children experiencing challenges with gross or fine motor skills, behavior, or activities of daily living. Additionally, therapist caseloads included infants and children who were referred to therapy because of concerns related to feeding/nutrition, as well as children and youth with exclusively orthopedic concerns.

Therapists’ responses to the interview question about baseline comfort with technology, varied from “not the best” to “comfortable”. Most indicated they were at least somewhat comfortable with technology, or “getting better”. A variety of initial emotions were expressed related to initiating telehealth, including “nervous”, “open to it”, “excited”, and “surprised” to be able to offer this service delivery option. When exploring therapists’ experiences of using telehealth, the three overarching themes were identified. Telehealth was viewed as a practical option; requires skill development and refinement; and is beneficial in perpetuity. These are illustrated in and expanded upon below.

Theme 1: Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic Was a Practical Option

When describing their initial thoughts and experiences related to using telehealth, therapists commented that this was a welcomed option to continue working during the pandemic (). They discussed the value of being able to engage in therapy with families during this time, rather than having to postpone or cancel visits due to limited capacity for in-person services. Participating therapists also described other benefits of connecting with families, such as being a familiar face in a time of isolation, being able to offer reassurance, or being able to connect families with additional resources such as mental health support where appropriate (). Within this theme, there was recognition that telehealth may present a better option than in-person visits in some situations, but that it would not work for every family, or all the time.

Table 1. Representative quotes organized by study themes.

Therapists readily identified several scenarios for which telehealth was particularly well-suited or where it may provide an advantage over in-person care. Specific to the pandemic, therapists described success using telehealth with families or caregivers who were interested in a quick check in for a mild concern that may not have warranted an in-person appointment either due to site capacity restrictions, or the family’s preference to not seek in-person care at the time. Similarly, telehealth was described as working well for families with children with medical complexity who may be more vulnerable to the effects of the virus.

In addition to these pandemic-related advantages, therapists also discussed how telehealth provided the benefit of allowing them to see and get to know children in the context of their own environment; to observe how they moved and played in that familiar space, interacted with their toys, or used equipment within their home. Some therapists found it easier to tailor therapy recommendations as they could integrate toys, equipment, or furniture that the family had in their space, or suggest modifications to the environment. Telehealth was viewed as particularly beneficial for children with stranger apprehension, or difficulties with transitions, who appeared to tolerate a session much better without the added stress of new people or new spaces. As one therapist said, “so it has been really eye-opening for me to get a glimpse of some of these children in their happy place” (P5). Therapists discussed how telehealth may save travel time for families and suggested that in non-pandemic times it may ease pressures for families with busy schedules or multiple children, those with limited modes of transportation or ability to take time away from work, and/or for those who are required to travel with a variety of medical equipment.

Therapists also identified that telehealth does not work for everyone, or all the time. Importantly, therapists raised the issue of inequitable access to telehealth-based care. Most shared the experience of having families decline telehealth-based appointments. Concerns were voiced about limited accessibility to therapy during the pandemic for families who do not have reliable internet, who do not have access to or comfort with technology, or who may not have a space in the home conducive to a telehealth session. Multiple therapists stated that they were unable to connect with some families via telehealth because the family did not have access to the required technology.

Diagnostic and treatment specific barriers were identified. Many ‘hands-on’ assessment or treatment techniques were not possible. For example, therapists discussed not being able to accurately assess muscle tone or joint stiffness, measure range of motion, or administer certain objective outcome measures. Some discussed limitations in assessing infant feeding, especially when sound quality was not ideal. In these cases, care via telehealth was viewed as less effective when compared with in-person care.

Theme 2: Telehealth Requires Skill Development and Refinement

Even though some therapists described themselves as tech savvy, using telehealth processes and platforms to provide therapy services was novel for all therapists and required new learning. Therapists described new processes that they had to learn and implement such as receiving consent for telehealth and scheduling telehealth appointments. Many described having to quickly adapt and learn how to conduct assessments and deliver care when they could not rely on in-person observation, physical touch, or hands-on assessment ().

In addition to acquiring new skills, therapists were also refining existing skills. Some voiced a renewed appreciation for the importance of breaking down instructions or movement strategies into core components when working with families. Being unable to physically participate in assessment or treatment was viewed as an opportunity to refine communication, coaching, and teaching skills ().

New resources for home program recommendations were also discussed. Prior to the pandemic, hand outs were provided in paper format to families, often with handwritten or drawn instructions. Therapists discussed the need to find and use handouts that could be sent electronically and provided clear and comprehensive instructions to supplement the telehealth sessions. At least one therapist reflected that these new resources were better than what they had been using, and that the switch to telehealth allowed them to prioritize the time it took to create and find new tools.

Rapid implementation and the novelty of this service delivery change meant that while certain necessary instructions and processes were in place, minimal formal training related to the telehealth platform or for this change in service delivery was available. Therapists described that things “moved really, really quickly at the beginning”, that they were “learning on the go”, or “through trial and error and finding out what works and what doesn’t work”. A small working group established the initial processes, and then therapists worked individually and with their colleagues to continue improving telehealth-related practices. Therapists shared tips that they had learned from experience, or from colleagues to improve the ability to deliver care. These are summarized in .

Table 2. Practical tips for using telehealth from therapists.

Finally, while therapists discussed opportunities related to this rapid service delivery change, almost all referred to feelings of exhaustion. Some related this to a dramatic decrease in physical movement or changes in the nature of interactions experienced throughout the day. Most commented on the mental fatigue that accompanied learning a new way of doing their job.

Theme 3: Telehealth Should Continue in Perpetuity

All therapists voiced support for continuing telehealth after the pandemic. A hybrid approach that provides the option for families to choose telehealth when it suits them was seen to align with family-centred or family-integrated approaches to care. Therapists discussed how family perceptions of usefulness of telehealth for their child/their family’s needs may determine whether they decide to engage via telehealth or not. The perceived urgency for the appointment, and specific to COVID-19, other priorities in the face of a pandemic were also discussed as factors influencing the decision to participate in telehealth. A flexible model was advocated for; one that allows for the mode of service delivery to change based on several factors, including the phase of treatment, stage of the child’s development, caregiver’s choice, therapist’s or caregiver’s perceived need for in-person (re)assessment, or other special circumstances.

Therapists reflected on a variety of situations where families may be unable to attend an in-person appointment, and telehealth may be a useful back-up option. For example, a sibling becomes ill, requiring the caregiver(s) to stay home, or inclement weather preventing travel to the center. In these situations, the child and caregiver still may be able to participate in a therapy session through telehealth. It was also noted that certain families may prefer telehealth during flu season. Overall, telehealth was viewed as “another tool in your toolkit”; another option that could support consistent and potentially more frequent follow up with families for a variety of reasons. Equity and family preferences were emphasized in discussion of future service provision models ().

Several key factors were identified that could support continued use of telehealth, including improved availability and access to technology for staff, and improved bandwidth at the rehabilitation facility so that higher volumes of concurrent virtual sessions could be managed. Physical space suggestions included dedicating certain spaces/more space to telehealth, and ensuring these spaces are equipped with the necessary selection of toys and therapy props. Some therapists discussed an ongoing need for new handouts to supplement the education provided during virtual sessions, and many voiced the need for more training and standardization (e.g., detailed protocols) if telehealth is to continue beyond the pandemic. As reflected in the quote referenced above (, Theme 3), the importance of identifying and supporting families with limited access to technology was also acknowledged.

Barriers and Facilitators to Telehealth Use during the Pandemic

I feel like it took a pandemic, but this has been a positive that’s come out of it (P5). Multiple barriers and facilitators to telehealth use are referenced within the above themes. The rapid implementation of telehealth during the pandemic offers the unique opportunity to further understand and classify these using a technology acceptance model, to inform maintenance of telehealth use as well as implementation of future technologies in this and similar settings. Barriers and facilitators were organized using the UTAUT as a framework (), which identifies four key determinants of technology use: i) performance expectancy, ii) effort expectancy, iii) social influence, and iv) facilitating conditions (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Beyond those mentioned within the main themes of the study, using the UTAUT to organize barriers and facilitators related to the rapid implementation of telehealth highlighted the importance of support from information technology specialists and senior management. Support from colleagues, and positive feedback from families were also viewed as important facilitators. Minimal training and issues of equity and accessibility were reinforced as barriers that will need to be addressed.

Table 3. Barriers and facilitators to telehealth uptake and use classified using the four main determinants within the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology.

Discussion

In this qualitative descriptive study, occupational and physical therapists largely described initiation and use of telehealth for service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic as a positive development, and voiced support for ongoing use of telehealth as a service delivery option. Multiple scenarios were described where telehealth worked well, and in some cases, better than in-person appointments. Therapists appreciated being able to see children in spaces that the child was used to, and frequently mentioned the reduced burden of travel for the family. Balancing these benefits, however, were important concerns and experiences related to families encountering barriers to accessing care via telehealth. These barriers included difficulties that families may experience related to accessing technology, including the device(s) and internet connection/data required to support connectivity. Technological literacy was also raised as a barrier to telehealth participation. A flexible and hybrid service delivery model was proposed by all therapists, that would allow for choice of in-person or telehealth-based care according to what enabled families to access care most easily, and what was best suited to the phase of therapy, family’s needs, preferences, or stage of the child’s development.

There is broad interest in the experiences of pediatric rehabilitation service providers during the rapid transition to telehealth-based services during COVID-19. A recent paper reported on a survey of over 200 pediatric physical therapists based in the United States (Hall et al., Citation2021). Based largely on responses to the open text survey questions, the main themes identified by the research team were caregiver engagement, technology, and resilience. Participants ranked caregiver engagement as the most important contributor toward effective telehealth-based care, and reliable internet connection and the ability to access devices to support telehealth as minimum requirements (Hall et al., Citation2021). In contrast, participants in our study tended to forefront the responsibilities of the therapist, for example to refine their communication and coaching skills and build or maintain relationship as key factors toward success, rather than caregiver engagement (Hall et al., Citation2021). An emphasis on the need for access to technology, and technological literacy was shared across our work and theirs (Hall et al., Citation2021).

Pediatric telehealth was also the topic of a conference session and subsequent perspectives paper led by Camden and Silva (Camden & Silva, Citation2021). The authors proposed the acronym “VIRTUAL” to represent guiding principles for telehealth implementation in this field. The categories of Viewing, Information, Relationships, Technology, Unique, Access, Legal (Camden & Silva, Citation2021) fit well with the themes identified from therapist interviews within our study. Theme 1 (A practical option) speaks to issues of access to care; the uniqueness of each family’s situation, requiring telehealth to be viewed as one option for service delivery; and the ability afforded by telehealth to view and work with the child and family within the familiar context of their home. Theme 2 (Requires skill development and refinement) aligns with information, technology, and relationship. The therapists discussed refining coaching skills and developing new resources to ensure information was clearly communicated to maintain a high standard of care; the emphasis on coaching aligning with Camden and Silva’s conceptualization of the therapist and family relationship; and ongoing training needs to use this technology were discussed. And while the legal aspect was not prominently featured within a theme, therapists identified support from management as a key facilitator to telehealth use, as management worked with therapists to quickly problem-solve and facilitate approval of processes within the context of evolving regional policies as the pandemic progressed.

It should be noted that research into the use and effectiveness of telehealth for pediatric healthcare and rehabilitation is not new. A systematic review of telehealth for pediatric rehabilitation (focusing on ages 0 to 12 years) included 23 randomized controlled trials published between 2007 to 2018, reporting that studies evaluating telehealth application in this field most often involved children with autism, brain injury, or unilateral cerebral palsy (Camden et al., Citation2020). Most studies focused on behavioral functioning, and in terms of effectiveness, outcomes for telehealth-based interventions were generally better for behaviourally-focused interventions than for those focusing on physical function (Camden et al., Citation2020). Evidence from nonrandomized studies have also evaluated accuracy, feasibility, acceptability, and satisfaction related to telehealth, for example with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or in the delivery of disability services (Hines et al., Citation2019; Juárez et al., Citation2018). These studies have demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy for ASD (78.9%), and high levels of family satisfaction with telehealth for service delivery (Hines et al., Citation2019; Juárez et al., Citation2018). In one study, the ability to use telehealth at a telemedicine site closer to home reduced travel for rural families by an average of 3.92 hours (Juárez et al., Citation2018). Of note, the use of a telemedicine site means that families did not have to bear the responsibility of connectivity and hardware to facilitate the connection.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique opportunity to study technology acceptance and use among service providers. Technology acceptance has been a focused area of research since the late 1990s, informed by psychology, sociology, and information systems theory (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Typically, an individual’s intention to use information technology is a key variable in technology acceptance theory and frameworks (Rahimi et al., Citation2018; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003), with user rejection cited as a key limiter to telehealth use specifically (Rahimi et al., Citation2018). In the context of a pandemic, where the preferred or standard option of in-person care is severely limited or not available, these factors were less relevant for therapists, for whom barriers and facilitators tended to focus on training, use, sustaining use, and effectiveness. Intention and user rejection, as variables related to telehealth use may have more of a role in the long-term use of telehealth by individual therapists, as in-person services are resumed, and therapist and family preferences are able to be more fully considered.

A critical area for ongoing study and action is that of ensuring that telehealth does not further widen existing disparities in access to care. Although we were not able to assess the demographics of families who accessed telehealth within this study, the majority of therapists voiced concern that telehealth may present additional barriers for families who already encounter barriers to accessing the health system. For the Canadian perspective, we direct readers to the compelling reflection by Beavis and Flett that includes a call to action to hold government accountable to agreements that would reduce infrastructure-related barriers to telehealth, particularly those barriers imposed on Indigenous communities, rooted racism and settler colonialism (Beavis & Flett, Citation2020). Importantly, the authors pair this call to physical therapists with recommendations for community partnered work to improve in-person service accessibility, and personal work to disrupt racism and promote health equity more broadly.

A United States-based study examined inequalities related to telehealth use, by linking data from the National Health and Wellness Survey with health claims data that included whether care was provided in-person or via telehealth (Jaffe et al., Citation2020). This quantitative study reported that people living in an urban setting were more than 50% more likely to have used telehealth than those in rural settings (Jaffe et al., Citation2020). They also found that older individuals were less likely to use telehealth (Jaffe et al., Citation2020). The authors discuss poverty, poor internet coverage in rural and southern US communities, and the potential for less technological comfort or literacy in older subgroups as factors implicated in reduced access of telehealth-based services (Jaffe et al., Citation2020). It is clear that a focus on equity is needed as we move forward with telehealth.

Limitations of this study include the single-site nature of the work and sole focus on the therapist’s perspective. Due to the relatively small sample size, we cannot be sure to have reached theoretical saturation and the sample size also limited our ability to meaningfully compare responses by profession. As noted above, we are unable to comment on the demographics of individuals who were or were not accessing telehealth at this site during the study period. This study is also lacking generalizability to school- or community-based therapists, who faced unique challenges in providing care in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. The perspectives here will however be useful to inform on-site therapy service provision, and technology implementation or continuance as our collective experience with this type of service delivery continues. Going forward, it is also of critical importance to understand and include patient and family perspectives on initial and continued telehealth-based service delivery, to make informed decisions about future telehealth use.

Conclusion

Telehealth-based services provided a means for physical therapists and occupational therapists to continue working with families in the midst of public health-related restrictions enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. As therapists continue to refine their knowledge and skills related to working with families via telehealth, formal training and effectiveness research will be key to guiding practice in what will likely be a hybrid model of care as the pandemic continues and beyond. Facilitating access to pediatric physical therapy and occupational therapy must remain a top priority in this hybrid model of care, and clinicians and researchers can and should be advocates for change rooted in equity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the therapist participants for taking part in this research in the midst of ongoing change and uncertainty. Thank you to Barb Borton, Director of Rehabilitation and Clinical Services, Rehabilitation Centre for Children, for her strong support of research and evaluation of new and ongoing initiatives at SSCY Centre in the spirit of continuously improving services and care for families.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

No funding was obtained to support this project. K Wittmeier is supported in part through the Dr. John M Bowman Chair in Pediatrics and Child Health, a partnership between the Winnipeg Rh Institute Foundation and the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Manitoba; and holds affiliations with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba and is Director of Research at Rehabilitation Center for Children and SSCY Center (Winnipeg Manitoba Canada). J Protudjer is supported in part through the Endowed Research Chair in Allergy, Asthma and the Environment, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Manitoba; and holds affiliations with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba, Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences, University of Manitoba; George and Fay Yee Center for Healthcare Innovation, and Center for Allergy Research, Karolinska Institutet; K Russell is supported in part though the Robert Wallace Cameron Chair in Evidence Based Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health and holds affiliations with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kristy D. M. Wittmeier

Kristy Wittmeier is a physiotherapist clinician-researcher with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba and an Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health at the University of Manitoba. She holds the inaugural Dr. John M Bowman Chair in Pediatrics and Child Health and is the Director of Research at SSCY Center. Kristy aims to conduct her research in an integrated fashion with healthcare providers, leadership, patients and families, to improve the accessibility and effectiveness of healthcare for children.

Elizabeth Hammond

Elizabeth Hammond has been a practicing physiotherapist since 2002. Elizabeth obtained her research Masters and Certified Hand Therapist (CHT) recognition in 2007 and PhD from the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Science at the University of Manitoba in 2018. Her PhD thesis evaluated the role for physical therapy in the management of peripheral neuropathy caused by chemotherapy. Research interests include exercise and physical therapy in the treatment of all causes of neuropathy and neuropathic pain. Currently, Elizabeth supports clinicians in evidence informed practice at the Rehabilitation Center for Children and teaches in the MPT program at the College of Rehabilitation Sciences

Kaitlyn Tymko

Kaitlyn Tymko is a recent graduate of the Master of Physical Therapy program at the University of Manitoba. Throughout her studies, she was involved in a variety of research projects with a primary focus on environmental physiology, specifically adaptation to hypoxic conditions at high-altitude. She participated in this research as part of the Physical Therapy program.

Kristen Burnham

Kristen Burnham is a recent graduate of the Master of Physical Therapy program at the University of Manitoba. She participated in this research as part of the Physical Therapy program.

Tamara Janssen

Tamara Janssen is a recent graduate of the Master of Physical Therapy program at the University of Manitoba. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the University of Winnipeg. She participated in this research as part of the Physical Therapy program.

Arnette J. Pablo

Arnette Pablo holds an undergraduate degree in Kinesiology from the University of Manitoba. He is also a recent graduate from the Master of Physical therapy from the University of Manitoba. He participated in this research as part of the Physical Therapy program.

Kelly Russell

Kelly Russell holds a PhD in sport injury epidemiology. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health at the University of Manitoba. She holds the Robert Wallace Cameron Chair in Evidence Based Medicine. She is also a research scientist at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba. Her research program focuses on injury prevention and treatment, particularly in the area of sport-related concussion and access to care.

Shayna Pierce

Shayna Pierce participated in this study as a research coordinator at the Rehabilitation Center for Children. She is currently a graduate student in the Clinical Psychology program at the University of Manitoba, focusing on determining the unmet mental health support needs of various patient populations.

Carrie Costello

Carrie Costello is a parent of three lovely daughters. Her middle daughter has a profound intellectual disability and a seizure disorder. Carrie has been a parent partner in research in over 8 projects. She is the patient engagement coordinator for the Children's Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba and works as the parent liaison for the CHILD-BRIGHT national research network.

Jennifer L. P. Protudjer

Jennifer LP Protudjer is the Endowed Research Chair in Allergy, Asthma and the Environment; and an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Manitoba; a research scientist at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba; and an epidemiologist with the Clinical Trials Platform at the George and Fay Yee Center for Healthcare Innovation. She also holds an adjunct professorship in the Department of Foods and Human Nutritional Sciences, University of Manitoba; and, and is an affiliated researcher at the Karolinska Institutet, where she completed her post-doctoral training. Her primary research interests include environmental risk factors for, and societal consequences of allergic disease, using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

References

- Beavis, A., & Flett, P. (2020). Magnifying inequities: Reflections on Indigenous health and physiotherapy in the context of COVID-19. shoPTalk Blog. https://physiotherapy.ca/blog/magnifying-inequities-reflections-indigenous-health-and-physiotherapy-context-covid-19

- Bettger, J., & Resnik, L. (2020). Telerehabilitation in the age of COVID-19: An opportunity for learning health system research. Physical Therapy, 100(11), 1913–1916. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa151

- Bradshaw, C., Atkinson, S., & Doody, O. (2017). Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4, 2333393617742282. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Budrionis, A., & Bellika, J. G. (2016). The Learning Healthcare System: Where are we now? A systematic review. J Biomed Inform, 64, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2016.09.018

- Camden, C., & Silva, M. (2021). Pediatric teleheath: Opportunities created by the COVID-19 and suggestions to sustain its use to support families of children with disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr, 41(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2020.1825032

- Camden, C., Pratte, G., Fallon, F., Couture, M., Berbari, J., & Tousignant, M. (2020). Diversity of practices in telerehabilitation for children with disabilities and effective intervention characteristics: Results from a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil, 42(24), 3424–3436. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1595750

- Ducharme, J. (2020). World Health Organization Declares COVID-19 a ‘pandemic'. Here's what that means. TIME USA LLC. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://time.com/5791661/who-coronavirus-pandemic-declaration/

- Gerlach, A. (2018). Exploring socially-responsive approaches to children's rehabilitation with Indigenous communities, families, and children.

- Hall, J. B., Woods, M. L., & Luechtefeld, J. T. (2021). Pediatric physical therapy telehealth and COVID-19: Factors, facilitators, and barriers influencing effectiveness-a survey study. Pediatr Phys Ther, 33(3), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000800

- Herendeen, N., & Deshpande, P. (2014). Telemedicine and the patient-centered medical home. Pediatr Ann, 43(2), e28. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20140127-07

- Hines, M., Bulkeley, K., Dudley, S., Cameron, S., & Lincoln, M. (2019). Delivering quality allied health services to children with complex disability via telepractice: Lessons learned from four case studies. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31(5), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-019-09662-8

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Isautier, J. M., Copp, T., Ayre, J., Cvejic, E., Meyerowitz-Katz, G., Batcup, C., Bonner, C., Dodd, R., Nickel, B., Pickles, K., Cornell, S., Dakin, T., & McCaffery, K. J. (2020). People's experiences and satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e24531. https://doi.org/10.2196/24531

- Jaffe, D. H., Lee, L., Huynh, S., & Haskell, T. P. (2020). Health inequalities in the use of telehealth in the United States in the lens of COVID-19. Population Health Management, 23(5), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2020.0186

- Juárez, A. P., Weitlauf, A. S., Nicholson, A., Pasternak, A., Broderick, N., Hine, J., Stainbrook, J. A., & Warren, Z. (2018). Early identification of ASD through telemedicine: potential value for underserved populations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2601–2610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3524-y

- Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-52

- Province of Manitoba. (2020). Media Bulletin - Manitoba: Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Bulletin #8.

- Rahimi, B., Nadri, H., Lotfnezhad Afshar, H., & Timpka, T. (2018). A systematic review of the technology acceptance model in health informatics. Applied Clinical Informatics, 9(3), 604–634. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1668091

- Rosenbaum, P. L., Silva, M., & Camden, C. (2021). Let's not go back to ‘normal'! Lessons from COVID-19 for professionals working in childhood disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(7), 1022–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1862925

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Sandelowski, M. (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

- Sasangohar, F., Davis, E., Kash, B. A., & Shah, S. R. (2018). Remote patient monitoring and telemedicine in neonatal and pediatric settings: Scoping literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(12), e295. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9403

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Tully, L., Case, L., Arthurs, N., Sorensen, J., Marcin, J. P., & O'Malley, G. (2021). Barriers and facilitators for implementing paediatric telemedicine: rapid review of user perspectives. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 630365. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.630365

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G., & Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.