Abstract

In this article we offer the first survey-based study on the motivations that spur consumers to bully others about the brands they support on social media, a phenomenon we term “Consumer Brand-Cyberbullying” (CBC). Analyzing data from 1,203 participants of online brand communities, we find that consumers who seek to be popular and attractive are more likely to engage in CBC, while those who seek to affiliate with close others and help the community are less likely to do so. Consumers who identify with and are loyal to a particular brand are more likely to engage in CBC. Taken together, our study moves us toward a systematic analysis of the relationship between brands and cyberbullying on social media.

Introduction

The following comments appeared on Nike’s official Facebook brand page below a post by the company about a new video commercialFootnote1:

The above exchange illustrates an increasingly frequent phenomenon: individuals offending others by making jokes or rude remarks about them. While terminology and definitions vary (see Slonje, Smith, and Frisén Citation2013), and disciplines differ in their conceptualization of such behaviors, we follow the literature in Psychology and classify them as “cyberbullying” (Ybarra and Mitchell Citation2007)—posting of comments, information, and pictures online for others to see with the intent to embarrass or offend.

There are two principal reasons why cyberbullying is a problem for contemporary societies. First, it causes harm. Being the victim of as well as merely a witness to cyberbullying reduces one’s life satisfaction, emotional security, and performance in daily tasks (Rodkin, Espelage, and Hanish Citation2015). A recent meta-analysis by Kowalski et al. (Citation2014) shows that long-term outcomes for victims may be very severe, including a higher likelihood of depression, anxiety, and drug abuse. Second, in line with the ever widening reach of the Internet and social media, increasing numbers of individuals are exposed to cyberbullying. Recent market research shows, for instance, that 66% of social-media users witness cyberbullying on a regular basis (PEW Citation2017). Unlike traditional (i.e., offline) bullying, victims of cyberbullying cannot physically remove themselves since mobile devices continually notify and reiterate social-media content (Tanrikulu, Kinay, and Aricak Citation2015). Moreover, cyberbullying on social media usually lasts longer since materials once posted often are permanently there and the ease of replication makes control of their circulation difficult (Runions and Bak Citation2015). Finally, cyberbullying tends to be more severe because perpetrators feel less inhibited in computer-mediated communication (Suler Citation2004). Consequently, a growing number of researchers are investigating why it occurs and what can be done about it (for a review, see Slonje, Smith, and Frisén Citation2013).

However, while extant work in Psychology, Information Science, and Digital Media Studies concentrates on cyberbullying that occurs in relation to individuals’ race, gender, social norms, political opinions, physical attributes, or personality dispositions (Herring et al. Citation2002; Moon, Weick, and Uskul Citation2018; Rodkin, Espelage, and Hanish Citation2015), researchers in these fields have so far overlooked the possibility that it can also take place in relation to consumer brands. Likewise, the Digital Marketing and Branding literature has largely focused on the positive aspects of online brand communities (e.g., Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould Citation2009), and theorization on why consumers engage in cyberbullying because of the brands they support has so far been limited to anecdotal suggestions (Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag Citation2018). In effect, there is a lack of research on cyberbullying in a consumer-brand context in general, and specifically regarding consumers’ underlying motives. Following Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag (Citation2018), we hereafter use the term “Consumer Brand-Cyberbullying” (CBC) to refer to cyberbullying that results from consumers’ bonds with brands.

Two additional factors specific to the consumers’ investment in their preferred brands add extra weight to the importance of studying of CBC. First, to be cyberbullied in relation to one’s brands can be just as damaging to an individual’s well-being as cyberbullying in other identity-related contexts, such as one’s gender or physical attributes. Several studies in Marketing show that consumers use brands as a means to express who they are (Isaksen and Roper Citation2016; Underwood, Bond, and Baer Citation2001), often to the extent that a brand’s values and performance define their own values and self-worth (Ferraro, Escalas, and Bettman Citation2011). Second, CBC appears to be unregulated even though it affects millions of social-media users. Although increasing numbers of consumers join online communities built by and around brands (e.g., Nike’s Facebook brand page), most brands’ corporate owners largely choose not to intervene when aggressive interactions occur (Dineva, Breitsohl, and Garrod Citation2017). Given that corporate online brand communities such as the one centered on Facebook brand pages have millions of daily visitors, CBC may present a particularly damaging form of cyberbullying compared to that which occurs in smaller, less public online communities.

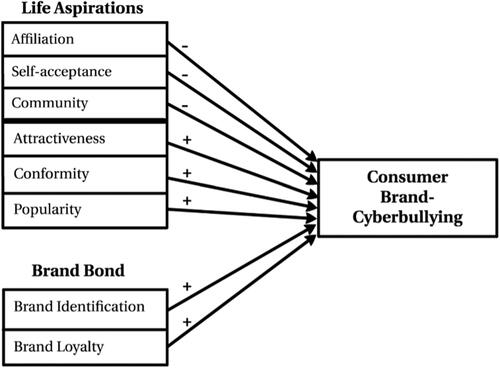

In this article we draw on multidisciplinary sources to expand the limited knowledge on the relationship between consumers’ bonds with brands and cyberbullying. While extant research does not engage directly with participants of online brand communities and relies on anecdotal and observational suggestions (Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag Citation2018), we used an online survey with responses from 1,203 Facebook brand-page users, and structural equation modeling (SEM) to test two main theoretical propositions. First, following Life Aspirations Theory (Grouzet et al. Citation2005), we hypothesize that consumers’ general aspirations in life—those that are rewarding in themselves (intrinsic) and those that require others’ recognition (extrinsic)—capture underlying reasons for how likely they are to bully others about the brands they support. Second, following Consumer Identification Theory (Bhattacharya and Sen Citation2003), we hypothesize that consumers’ bond with a particular brand—their purchasing loyalty and brand identification—has a bearing on CBC motivation. In other words, we propose that a consumer who cyberbullies others about brands is driven by general, psychological motives as well as by motives related to his/her role as a supporter of a brand.

In what follows, we provide a brief overview of the cyberbullying literature, followed by discussions on the theorization that gave rise to our hypotheses, our methodology, and findings. We conclude with discussions on our contributions to theory and practice, limitations of our study, and suggestions for future research.

Cyberbullying research across disciplines

Cyberbullying has been studied across several research disciplines, including Psychology (Kowalski et al. Citation2014), Information Studies (Xu, Xu, and Li Citation2016), Digital Media Studies (Chen, Ho, and Lwin Citation2017), Computer Science (Rosa et al. Citation2019), Politics (Bauman Citation2019) and Sociology (Moloney and Love Citation2018). Consequently, different research streams have developed in parallel, giving rise to conceptual debates about what constitutes cyberbullying and how it compares to other forms of verbal aggression on social media (Foody, Samara, and Carlbring Citation2015; Kowalski et al. Citation2014). For instance, on the difference between cyberbullying and trolling, some researchers suggest they are discrete concepts, as cyberbullying tends to be seen as the more harmful behavior (March and Marrington Citation2019), whereas trolling may be both lighthearted and serious (Sanfilippo, Fichman, and Yang Citation2018), if not a positive behavior that can increase online community engagement (Cruz, Seo, and Rex Citation2018). Other researchers argue that social-media users may not distinguish between cyberbullying and trolling, since the perception of what is harmful and anti-social in online environments is highly subjective and contextual (Chen Citation2018), given that non-verbal cues here are limited compared to offline interactions (Lapidot-Lefler and Barak Citation2012).

Similarly, concepts such as online incivility (Ordoñez and Nekmat Citation2019), flaming (Hutchens, Cicchirillo, and Hmielowski Citation2015), and online hate (Chau and Xu Citation2007) tend to overlap conceptually; consensus, across disciplines, on the conceptualization of different forms of anti-social behaviors online is yet to be achieved (Cruz, Seo, and Rex Citation2018; Peter and Petermann Citation2018). Therefore, we use cyberbullying as an umbrella term that includes all forms of anti-social behaviors online in this article, and direct readers to recent systematic reviews by Foody, Samara, and Carlbring (Citation2015) and Moor and Anderson (Citation2019) for an overview of different research streams and current debates.

On social-media users’ motives for verbally attacking each other, research has focused predominantly on socio-psychological factors such as personality traits (Moor and Anderson Citation2019), social and peer norms (Chen, Ho, and Lwin Citation2017), moral beliefs (Johnen, Jungblut, and Ziegele Citation2018), empathy (Howard Citation2019), and negative mood states (Pieschl et al. Citation2013), to name but a few (for a review, see Chen, Ho, and Lwin Citation2017; Guo Citation2016; Kowalski et al. Citation2014). In the face of missing empirical research on motivations behind brand-related cyberbullying, in a first step, we rely on researched based on two established theories on consumers’ life aspirations and brand identification to develop hypotheses, as will be outlined in the next section.

Consumers’ life aspirations and CBC

According to Kasser and Ryan’s (Citation1993) Life Aspiration Theory, consumers pursue two types of aspirations in life. Intrinsic aspirations refer to the pursuit of intrinsically rewarding need satisfactions, such as having meaningful affiliations, accepting one’s self, and making a valuable contribution to the community. Extrinsic aspirations focus on attaining external rewards or praise and usually include a desire to feel popular, to fit in, and to be attractive to others. In general, intrinsic aspirations tend to trigger positive interpersonal behaviors, whereas extrinsic aspirations are more likely to lead to negative interpersonal behaviors (Kasser and Ryan Citation1993).

In particular, aspirations for affiliation are likely to negatively influence CBC. According to Cialdini and Goldstein (Citation2004), affiliation relates to family life and good friends, and maintenance of meaningful social relationships (Cialdini and Goldstein Citation2004). In virtual environments, Claffey and Brady (Citation2017) identified affiliation with other brand followers as the main purpose for engaging in online communities. In relation to cyberbullying, Ang’s (Citation2015) review of existing research indicates that individuals who lack emotional relationships in their social environment and yet long for such bonds are less likely to engage in bullying behaviors, both online and offline. Conversely, in a study on narcissism, Kirkpatrick et al. (Citation2002) found that affiliation (i.e., a desire to feel socially included by others) diminishes aggressive behavioral intentions.

Likewise, we expect self-acceptance to have a negative impact on CBC. Self-acceptance includes aspirations for personal growth, autonomy, and happiness (Kasser and Ryan Citation1993). Studies show that individuals with high levels of these aspirations are less likely to be perpetrators of cyberbullying (Brewer and Kerslake Citation2015) and aggression in general (Mofrad and Mehrabi Citation2015). Further, self-acceptance inhibits negative social comparisons in online communities (Appel, Crusius, and Gerlach Citation2015), an important contributory factor to feeling rejected, and aggressing peers who appear socially superior (Banerjee and Dittmar Citation2008).

Similarly, community-oriented aspirations, such as engaging in altruistic activities and contributing to society as a whole, are likely to reduce socially dysfunctional behaviors (Kasser and Ryan Citation1993). This is significant, given that community aspirations, such as helping others by sharing knowledge and solving problems, is a cornerstone of viable online communities (Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould Citation2009). A recent meta-analysis by De Wit, Greer, and Jehn (Citation2012) shows that citizenship behavior—the will to go beyond one’s own interest in helping a group or organization—is negatively correlated to individuals’ tendency to start a conflict with someone. Promoting community-driven behaviors also seems to reduce bullying among schoolchildren (Frey et al. Citation2005). Taken together, we propose the following:

H1: Consumers’ aspiration for affiliation has a negative effect on CBC.

H2: Consumers’ aspiration for self-acceptance has a negative effect on CBC.

H3: Consumers’ aspiration for community engagement has a negative effect on CBC.

In contrast, extrinsic aspirations are likely to increase CBC. The aspiration to be attractive to others, for instance, has already been found to cause greater amounts of aggressive thoughts (Sakellaropoulo and Baldwin Citation2007), appearance-related cyberbullying (Berne, Frisén, and Kling Citation2014), and aggressive behavior in general (Bushman and Baumeister Citation1998). Further, the need to be seen as attractive positively correlates with narcissism (Vazire et al. Citation2008), a personality trait which is predictive of bullying behavior on Facebook (Craker and March Citation2016). Therefore, we theorize that consumers who place a high level of importance on their appearance, and use brands to communicate their attractiveness to others in online communities (e.g., Krämer et al. Citation2017), are likely to bully others who somehow threaten their narcissistic needs (Weiser Citation2015).

The extrinsic aspiration for conformity fosters aggressive behavior. According to Grouzet et al. (Citation2005), conformity-seeking relates to people’s aspirations to fit in with others and to appear similar to those in their aspirational groups. Studies on bullying behavior show that people aggress others in order to show that they fit in with a particular group and are different from those who are not part of that group (e.g., Shapiro, Baumeister, and Kessler Citation1991). Further, interviews with schoolchildren and adolescents show that those from low-income backgrounds who cannot afford brands are likely to be victims of bullying as they “do not fit in” (Isaksen and Roper Citation2016, 652). Breitsohl, Wilcox-Jones, and Harris (Citation2015) also found that conformity-seeking is a frequent phenomenon in online communities as a result of stress and perceived social insulation.

The need to be popular and admired is also likely to produce CBC behavior. Findings from studies on political hate-speech (Sobkowicz and Sobkowicz Citation2010) and harmful peer interactions (Isaksen and Roper Citation2012) support the notion that verbal aggression may be used as a social tool to gain admiration from others. Online community users, for instance, are likely to experience jealousy if they feel less popular than others (Appel, Crusius, and Gerlach Citation2015), which in turn can lead to the derogation of those who are envied (Banerjee and Dittmar Citation2008). Arguably, consumers in online brand communities may therefore satisfy their need for popularity by directing derogatory comments at other brand users who may have breached a community norm or engaged in brand criticism (see Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag Citation2018). Taken together, we propose the following:

H4: Consumers’ aspiration for attractiveness has a positive effect on CBC.

H5: Consumers’ aspiration for conformity has a positive effect on CBC.

H6: Consumers’ aspiration for popularity has a positive effect on CBC.

Consumers’ brand bond and CBC

Although studies on the link between cyberbullying and consumers’ bond with brands are scarce, research based on Consumer Identification Theory allows for some tentative propositions. This research suggests that proximity of one’s self-image to a brand’s image manifests in consumers’ identity beliefs as well as by their loyalty behaviors (Algesheimer, Dholakia, and Herrmann Citation2005; Stokburger-Sauer, Ratneshwar, and Sen Citation2012). In relation to consumers’ brand identification, Isaksen and Roper (Citation2012) found that individuals who draw on brands to develop and express their identity tend to bully those who do not identify with the same brands. Likewise, Wooten (Citation2006) found that when a consumer feels that someone presents a threat to his/her identity, the consumer tends to respond aggressively. This is likely to particularly occur in online brand communities where members sanction those who do not adhere to or criticize the values of the brand upon which the community is built (Luedicke, Thompson, and Giesler Citation2010).

Similarly, consumers’ brand loyalty, i.e., the sustained, long-term preference and repurchase of a brand (Chaudhuri and Holbrook Citation2001), is likely to increase CBC. Previous studies on online communities suggests that the long-term preference of one brand over another can lead consumers to attack those who do not share the same preference (Thompson and Sinha Citation2008), or brand rivals who openly support competitors (Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould Citation2009). Further, the longer one has been loyal to a brand, the higher the costs of switching to a competitor since switching would require an acknowledgement of having followed the wrong brand (see Lam et al. Citation2010). Arguably, high switching costs may therefore lead loyal brand followers to attack anyone whose comments threaten the superiority of their chosen brand. Taken together, we propose the following:

H7: Consumers’ identification with a brand has a positive effect on CBC.

H8: Consumers’ loyalty to a brand has a positive effect on CBC.

summarizes our hypothesized relationships.

Method

To test our hypotheses, we designed an online survey and conducted a two-stage pilot test with Facebook brand-page users, since this is where Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag (Citation2018) identified instances of CBC. In stage 1, we sought qualitative feedback from four marketing academics and 12 postgraduate students, who indicated regular use of Facebook brand pages. In stage 2, we sent the survey to 26 regular Facebook brand-page users without a marketing background, to garner further feedback and eliminate potential terminological misunderstandings. We subsequently posted a link to the final survey in 13 online communities and thereon reposted it for three weeks. More specifically, following Ridings, Gefen, and Arinze (Citation2006), we considered an online community to be suitable for inclusion if it contained a minimum of 10 posts per day by at least 15 different members for each of three consecutive days chosen at random. Due to access restrictions on a number of corporate Facebook brand pages, we chose to include unofficial brand pages hosted both on Facebook and independent forums. A screening question—“Do you follow the official Facebook brand page of the brand which you entered in the previous textbox?”—ensured that all respondents were users of corporate Facebook brand pages independent of where the survey link was posted.

Our survey generated a total of 1,203 completed and utilizable responses. Respondents were predominantly male (71%), aged between 18 and 34 (60%), and reported a monthly income between US$1,651 and US$7,000. A majority of respondents (57%) indicated that they posted on Facebook brand pages at least once per month, and a majority (59%) visited brand pages at least twice per week.

In our survey, we employed established measurement instruments taken from the Branding and Psychology literature—based on five-point Likert scales (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). We measured consumers’ life aspirations via the refined Aspiration Index (Grouzet et al. Citation2005), and consumers’ brand bond via constructs from Stokburger-Sauer, Ratneshwar, and Sen’s (Citation2012) study on brand identification and brand loyalty. For CBC, we adopted Parada’s (Citation2000) Peer Relations Instrument and adjusted items to fit the brand-specific context. In doing so, we conducted a pretest which provided 82 marketing students (aged between 18 and 51) with a selection of typical CBC comments. We then gave them a list of terms from Parada’s instrument and asked them to indicate which term or terms best described what they saw in the CBC comments. We took the three terms that participants mentioned most frequently, namely “teasing,” “making rude remarks” and “making jokes.” in the Appendix provides the details of all instruments used.

Table A1. Measurement items and psychometric properties.

Results

To analyze the data, we used LISREL 8.7 and structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is a well-accepted covariance analysis in marketing research for estimating causal models and multivariate data sets (Iacobucci Citation2009). It enables the researcher to test multiple regressions between all constructs within the same analysis, while using a number of diagnostic tools to account for various measurement errors (Gefen, Straub, and Boudreau Citation2000; Hair et al. Citation2017). For these reasons, SEM tends to be the preferred analytical method in survey research and cross-sectional studies (Bagozzi and Yi Citation2012). We followed the established Anderson and Gerbing’s (Citation1988) two-step approach, consisting of the validation of the measurement model and subsequent analysis of the latent variables via path analysis.

As a first step, we examined the measurement model to test for reliability and validity. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) confirmed the unidimensionality of analyzed factors, which is important to determine the correlations among the observed variables and related factors in a dataset (Bagozzi and Yi Citation2012). Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that all standardized loadings were larger than .7 and significant at p<.001. For a measurement model that adequately fits the data, Baumgartner and Homburg (Citation1996) suggest a number of threshold criteria, stating a required comparative fit index (CFI) above .9, a goodness of fit index (GFI) above .9, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .5. A satisfactory measurement model offers an additional degree of confidence in the relationship between the observed data and the proposed model.

Given that all fit indices of our model met these criteria (χ2 = 1205.17, p = .01, CFI = .97, GFI = .93, and RMSEA = .05), in our estimation, it provided a good fit. SEM studies need to establish several other criteria to validate the adequacy of their measurement constructs, including measures of convergent validity, reliability, and discriminant validity (Bagozzi and Yi Citation2012). Commonly reported criteria to establish convergent validity are an average variance extracted (AVE) of at least .5, and a composite reliability (CR) of at least .7 (Bagozzi and Yi Citation2012), and our data exceeded these thresholds. To measure the reliability of our constructs, we computed Cronbach alpha (α) values. For a construct to be reliable, the α needs to be above .7, and this was the case for all our constructs apart from Community. Since the composite reliability for the Community construct was sufficient, and all other coefficients in our study fulfilled the required criteria, we proceeded with the analysis including the Community construct, as suggested by Cronbach and Shavelson (Citation2004). The AVE value for each construct was always greater than the squared correlation estimated between any two factors (see ), suggesting discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981).

Table 1. Correlation matrix.

We further tested for common method variance (CMV) to identify unwanted correlations among our focal variables, i.e., correlations that exist because of how we designed our research instrument, rather than for theoretically meaningful reasons. Following Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001), we designated a marker variable—corporate social responsibility (“The company should intervene when there is undesirable behavior in this community”), and used the lowest correlation (r = .20) as a proxy to adjust the correlation matrix. All correlations that were significant before the adjustment remained significant, suggesting that CMV did not affect our findings.

To analyze the hypothesized relationships, we then used SEM based on the maximum likelihood estimator, a commonly used statistical inference framework that has been shown to perform well in SEM (Hair et al. Citation2017). As can be seen in , the overall model fit was acceptable. Results generally confirm our hypotheses that consumers’ intrinsic life aspirations have a negative effect on CBC, while extrinsic life aspirations have a positive effect on CBC. Two life aspirations—Self-acceptance and Conformity—did not have a significant effect on CBC. Both factors related to consumers’ identification had a positive effect on CBC. In accordance with past research on life aspirations and consumer behavior (Kasser et al. Citation2014) we also included several control variables. Both age (ß: .07) and gender (ß: .09) had a significant effect on CBC, while posting frequency and income did not.

Table 2. Motives for Consumer Brand-Cyberbullying (CBC): Structural parameter estimates.

Conclusions

Theoretical implications

The cyberbullying literature in Psychology as well as related literatures in disciplines such as Sociology and Information Studies have overlooked consumers’ bond with brands as a motivating factor. Our study makes a contribution by locating brand identification as an identity-centric motivating factor for cyberbullying. On a larger canvas, it complements work on political- (Clark Citation2016; Gil de Zúñiga, Barnidge, and Diehl Citation2018), race- (Ramasubramanian Citation2016), religion- (Barzilai-Nahon and Barzilai Citation2005) and gender- (Gruber Citation1999; Herring Citation1999) related issues and identity.

Likewise, the Marketing and Branding literature has largely overlooked cyberbullying in studies related to consumer’s identification with brands. Extant studies are limited to anecdotal suggestions, they note that consumers often attack each other in online brand communities, but do not systematically examining this phenomenon. Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag (Citation2018), examining textual data (i.e., consumer comments) in their study on cyberbullying, are able to provide evidence of its occurrence but not engage the question why CBC takes place. We take this emerging literature a step further with a survey-based study on people’s motivations for engaging in CBC. More specifically, we show that brand loyalty and brand identification can lead to CBC.

Further, our study offers fresh insights into how individuals’ general aspirations in life can lead to brand-related cyberbullying. Our findings indicate that intrinsic and extrinsic life aspirations have diametrically different effects on CBC. We show that consumers who aspire to be popular and attractive to others are more likely to engage in CBC. However, those following life aspirations that privilege their community and affiliation with others are less likely to do so. This generally aligns with Kasser and Ryan’s (Citation1993) early work, which shows that those following intrinsic aspirations are less likely to engage in anti-social behavior than those following extrinsic aspirations (see also Kasser et al. Citation2014).

Managerial implications

Our study also provides insights for policymakers and marketing practitioners. For the former, we flag the need for them to take notice of cyberbullying in online brand communities. Our findings show that intrinsic life goals reduce the likelihood of CBC—they should therefore be cultivated. Approaching from the other side, educational campaigns that generate an understanding of the negative effects of extrinsic life goals may also help reduce CBC.Footnote2 For the latter, we propose that management of CBC can be another vehicle for positioning their companies as responsible participants in the marketplace. It could be a corporate contribution toward improving social well-being, as part of their companies’ corporate social responsibility and philanthropic activities.

Limitations and future research

Our study paves the way for several avenues of future research. First, our choice of life aspirations for this study should only be seen as an initial exploratory step. Future research may fruitfully test alternative and complementary constructs for understanding people’s motives for engaging in CBC. For instance, recent work on aggressive dialogues on Facebook indicates that personality traits are another significant predictor of verbal aggression on social media (Bollmer et al. Citation2003). In particular, the dark triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism—are worth exploring in this respect (Craker and March Citation2016). Second, we urge researchers to investigate the role of companies that host online communities. Do consumers expect companies to intervene when CBC occurs in an online brand community? Moreover, what type of intervention is most appreciated by those actively involved in a CBC episode, and those who passively observe it? Dineva, Breitsohl, and Garrod’s (Citation2017) observational study suggests that currently companies follow a strategy of ignoring any form of consumer-to-consumer conflicts. However, future research should employ experimental designs to test different potential corporate interventions, such as censorship (Pfaffenberger Citation1996), explicit community rules (De Cindio et al. Citation2003), troll management tactics (Herring et al. Citation2002) and other forms of recently identified governance strategies (see Feenberg Citation2019; Helberger, Pierson, and Poell Citation2018).

Finally, there is scope to expand on two elements of our methodological approach. One, our selection of online communities focused exclusively on Facebook brand pages. Researchers could explore other social-media channels. For instance, it is likely that CBC also occurs on Twitter (see Simunjak and Caliandro Citation2019), which, unlike Facebook, is more limited in terms of how consumers can communicate, as well as in its interactive features (John and Nissenbaum Citation2019). There may also be some cross-channel effects, where consumers engage in CBC on several social-media channels and interlink their content (Haythornthwaite Citation2002). Second, researchers could build on scale items we used to identify CBC. Due to the lack of studies on brand-related cyberbullying, we chose to adopt an existing instrument and use pilot tests to identify the three items that best reflect CBC from a respondent’s perspective—namely “teasing,” “making rude remarks” and “making jokes.” We hope researchers will explore more holistic instruments to capture CBC, perhaps incorporating additional items that reflect new types of cyberbullying, such as threats and constructive criticism (Breitsohl, Roschk, and Feyertag Citation2018).

Notes

1 Names have been changed for purposes of anonymity; spelling errors have been kept as originally found on the brand page.

2 Studies on the effectiveness of cyberbullying interventions, at present, remain inconclusive (Ang 2015), yet there is some evidence that targeting specific motives of Internet users can render anti-bullying campaigns more successful (Yeager et al. 2015).

References

- Algesheimer, R., U. M. Dholakia, and A. Herrmann. 2005. The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing 69 (3):19–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363.

- Anderson, J. C., and D. W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103 (3):411–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411.

- Ang, R. P. 2015. Adolescent cyberbullying: A review of characteristics, prevention and intervention strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior 25:35–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011.

- Appel, H., J. Crusius, and A. L. Gerlach. 2015. Social comparison, envy, and depression on Facebook: A study looking at the effects of high comparison standards on depressed individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 34 (4):277–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.4.277.

- Bagozzi, R. P., and Y. Yi. 2012. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (1):8–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x.

- Banerjee, R., and H. Dittmar. 2008. Individual differences in children’s materialism: The role of peer relations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (1):17–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207309196.

- Barzilai-Nahon, K., and G. Barzilai. 2005. Cultured technology: The Internet and religious fundamentalism. The Information Society 21 (1):25–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240590895892.

- Bauman, S. 2019. Political cyberbullying: Perpetrators and targets of a new digital aggression. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Baumgartner, H., and C. Homburg. 1996. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing 13 (2):139–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(95)00038-0.

- Berne, S., A. Frisén, and J. Kling. 2014. Appearance-related cyberbullying: A qualitative investigation of characteristics, content, reasons, and effects. Body Image 11 (4):527–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.08.006.

- Bhattacharya, C. B., and S. Sen. 2003. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing 67 (2):76–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609.

- Bollmer, J. M., M. J. Harris, R. Milich, and J. C. Georgesen. 2003. Taking offense: Effects of personality and teasing history on behavioral and emotional reactions to teasing. Journal of Personality 71 (4):557–603. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.7104003.

- Breitsohl, J., H. Roschk, and C. Feyertag. 2018. Consumer brand bullying behaviour in online communities of service firms. In Service business development, ed. M. Bruhn and K. Hadwich, 289–312. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer.

- Breitsohl, J., J. P. Wilcox-Jones, and I. Harris. 2015. Groupthink 2.0: An empirical analysis of customers’ conformity-seeking in online communities. Journal of Customer Behaviour 14 (2):87–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1362/147539215X14373846805662.

- Brewer, G., and J. Kerslake. 2015. Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior 48:255–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.073.

- Bushman, B. J., and R. F. Baumeister. 1998. Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 (1):219–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.219.

- Chau, M., and J. Xu. 2007. Mining communities and their relationships in blogs: A study of online hate groups. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 65 (1):57–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.08.009.

- Chaudhuri, A., and M. B. Holbrook. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65 (2):81–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255.

- Chen, L., S. S. Ho, and M. O. Lwin. 2017. A meta-analysis of factors predicting cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: From the social cognitive and media effects approach. New Media & Society 19 (8):1194–213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816634037.

- Chen, Y. 2018. “Being a butt while on the Internet”: Perceptions of what is and isn’t Internet trolling. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 55 (1):76–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2018.14505501009.

- Cialdini, R. B., and N. J. Goldstein. 2004. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology 55:591–621. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015.

- Claffey, E., and M. Brady. 2017. Examining consumers’ motivations to engage in firm-hosted virtual communities. Psychology & Marketing 34 (4):356–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20994.

- Clark, L. S. 2016. Participant or zombie? Exploring the limits of the participatory politics framework through a failed youth participatory action project. The Information Society 32 (5):343–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2016.1212619.

- Craker, N., and E. March. 2016. The dark side of Facebook: The Dark Tetrad, negative social potency, and trolling behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences 102:79–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.043.

- Cronbach, L. J., and R. J. Shavelson. 2004. My current thoughts on coefficient alpha and successor procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement 64 (3):391–418. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404266386.

- Cruz, A. G., Y. Seo, and M. Rex. 2018. Trolling in online communities: A practice-based theoretical perspective. The Information Society 34 (1):15–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391909.

- De Cindio, F., O. Gentile, P. Grew, and D. Redolfi. 2003. Community networks: Rules of behavior and social structure special issue: ICTs and community networking. The Information Society 19 (5):395–406. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/714044686.

- De Wit, F. R. C., L. L. Greer, and K. A. Jehn. 2012. The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (2):360–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024844.

- Dineva, D. P., J. Breitsohl, and B. Garrod. 2017. Corporate conflict management on social media brand fan pages. Journal of Marketing Management 33 (9-10):679–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1329225.

- Feenberg, A. 2019. The Internet as network, world, co-construction, and mode of governance. The Information Society 35 (4):229–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2019.1617211.

- Ferraro, R., J. E. Escalas, and J. R. Bettman. 2011. Our possessions, our selves: Domains of self-worth and the possession-self link. Journal of Consumer Psychology 21 (2):169–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.08.007.

- Foody, M., M. Samara, and P. Carlbring. 2015. A review of cyberbullying and suggestions for online psychological therapy. Internet Interventions. 2 (3):235–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.05.002.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (3):382–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313.

- Frey, K. S., S. B. Nolen, L. V. S. Edstrom, and M. K. Hirschstein. 2005. Effects of a school-based social-emotional competence program: Linking children’s goals, attributions, and behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 26 (2):171–200. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2004.12.002.

- Gefen, D., D. Straub, and M.-C. Boudreau. 2000. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 4:1–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., M. Barnidge, and T. Diehl. 2018. Political persuasion on social media: A moderated moderation model of political discussion disagreement and civil reasoning. The Information Society 34 (5):302–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1497743.

- Grouzet, F. M. E., T. Kasser, A. Ahuvia, J. M. Fernández, Y. Kim, S. Lau, R. M. Ryan, S. Saunders, P. Schmuck, and K. M. Sheldon. 2005. The structure of goal contents across 15 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (5):800–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.800.

- Gruber, S. 1999. Communication gone wired: Working toward a “practiced” cyberfeminism. The Information Society 15 (3):199–208. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/019722499128501.

- Guo, S. 2016. A meta-analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychology in the Schools 53 (4):432–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21914.

- Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, and K. O. Thiele. 2017. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45 (5):616–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x.

- Haythornthwaite, C. 2002. Strong, weak, and latent ties and the impact of new media. The Information Society 18 (5):385–401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108195.

- Helberger, N., J. Pierson, and T. Poell. 2018. Governing online platforms: From contested to cooperative responsibility. The Information Society 34 (1):1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391913.

- Herring, S. C. 1999. The rhetorical dynamics of gender harassment on-line. The Information Society 15 (3):151–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/019722499128466.

- Herring, S., K. Job-Sluder, R. Scheckler, and S. Barab. 2002. Searching for safety online: Managing “trolling” in a feminist forum. The Information Society 18 (5):371–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108186.

- Howard, K., K. H. Zolnierek, K. Critz, S. Dailey, and N. Ceballos. 2019. An examination of psychosocial factors associated with malicious online trolling behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences 149:309–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.020.

- Hutchens, M. J., V. J. Cicchirillo, and J. D. Hmielowski. 2015. How could you think that?!?!: Understanding intentions to engage in political flaming. New Media & Society 17 (8):1201–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522947.

- Iacobucci, D. 2009. Everything you always wanted to know about SEM (structural equations modeling) but were afraid to ask. Journal of Consumer Psychology 19 (4):673–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.002.

- Isaksen, K. J., and S. Roper. 2012. The commodification of self-esteem: Branding and British teenagers. Psychology & Marketing 29 (3):117–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20509.

- Isaksen, K., and S. Roper. 2016. Brand ownership as a central component of adolescent self-esteem: The development of a new self-esteem scale. Psychology & Marketing 33 (8):646–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20906.

- John, N. A., and A. Nissenbaum. 2019. An agnotological analysis of APIs: Or, disconnectivity and the ideological limits of our knowledge of social media. The Information Society 35 (1):1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1542647.

- Johnen, M., M. Jungblut, and M. Ziegele. 2018. The digital outcry: What incites participation behavior in an online firestorm? New Media & Society 20 (9):3140–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817741883.

- Kasser, T., and R. M. Ryan. 1993. A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65 (2):410–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410.

- Kasser, T., K. L. Rosenblum, A. J. Sameroff, E. L. Deci, C. P. Niemiec, R. M. Ryan, O. Árnadóttir, R. Bond, H. Dittmar, N. Dungan, et al. 2014. Changes in materialism, changes in psychological well-being: Evidence from three longitudinal studies and an intervention experiment. Motivation and Emotion 38 (1):1–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9371-4.

- Kirkpatrick, L. A., C. E. Waugh, A. Valencia, and G. D. Webster. 2002. The functional domain specificity of self-esteem and the differential prediction of aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82 (5):756–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.756.

- Kowalski, R. M., G. W. Giumetti, A. N. Schroeder, and M. R. Lattanner. 2014. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 140 (4):1073–137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618.

- Krämer, N. C., M. Feurstein, J. P. Kluck, Y. Meier, M. Rother, and S. Winter. 2017. Beware of selfies: The impact of photo type on impression formation based on social networking profiles. Frontiers in Psychology 8:188. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00188.

- Lam, S. K., M. Ahearne, Y. Hu, and N. Schillewaert. 2010. Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: A social identity theory perspective. Journal of Marketing 74 (6):128–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.6.128.

- Lapidot-Lefler, N., and A. Barak. 2012. Effects of anonymity, invisibility, and lack of eye-contact on toxic online disinhibition. Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2):434–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.014.

- Lindell, M. K., and D. J. Whitney. 2001. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. The Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (1):114–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114.

- Luedicke, M. K., C. J. Thompson, and M. Giesler. 2010. Consumer identity work as moral protagonism: How myth and ideology animate a brand-mediated moral conflict. Journal of Consumer Research 36 (6):1016–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/644761.

- March, E., and J. Marrington. 2019. A qualitative analysis of Internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 22 (3):192–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210.

- Mofrad, S. H. K., and T. Mehrabi. 2015. The role of self-efficacy and assertiveness in aggression among high-school students in Isfahan. Journal of Medicine and Life 8:225–31.

- Moloney, M. E., and T. P. Love. 2018. Assessing online misogyny: Perspectives from sociology and feminist media studies. Sociology Compass 12 (5):e12577. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12577.

- Moon, C., M. Weick, and A. K. Uskul. 2018. Cultural variation in individuals’ responses to incivility by perpetrators of different rank: The mediating role of descriptive and injunctive norms. European Journal of Social Psychology 48 (4):472–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2344.

- Moor, L., and J. R. Anderson. 2019. A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences 144:40–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.027.

- Ordoñez, M. A. M., and E. Nekmat. 2019. Tipping point” in the SoS? Minority-supportive opinion climate proportion and perceived hostility in uncivil online discussion. New Media & Society 21 (11–12):2483–504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819851056.

- Parada, R. H. 2000. Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of participant roles in bullying and victimization of adolescence: An interim test manual and a research monograph: A test manual. Penright South, DC: Publication Unit, Self-concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney.

- Peter, I.-K., and F. Petermann. 2018. Cyberbullying: A concept analysis of defining attributes and additional influencing factors. Computers in Human Behavior 86:350–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.013.

- Pew Research Center (PEW). 2017. Online harassment 2017. Last modified July 11, 2017. Accessed June 11, 2020. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/.

- Pfaffenberger, B. 1996. If I want it, it’s OK”: Usenet and the (outer) limits of free speech. The Information Society 12 (4):365–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/019722496129350.

- Pieschl, S., T. Porsch, T. Kahl, and R. Klockenbusch. 2013. Relevant dimensions of cyberbullying: Results from two experimental studies. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 34 (5):241–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.04.002.

- Ramasubramanian, S. 2016. Racial/ethnic identity, community-oriented media initiatives, and transmedia storytelling. The Information Society 32 (5):333–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2016.1212618.

- Ridings, C. M., D. Gefen, and B. Arinze. 2006. Psychological barriers: Lurker and poster motivation and behavior in online communities. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 18:329–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01816.

- Rodkin, P. C., D. L. Espelage, and L. D. Hanish. 2015. A relational framework for understanding bullying: Developmental antecedents and outcomes. The American Psychologist 70 (4):311–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038658.

- Rosa, H., N. Pereira, R. Ribeiro, P. C. Ferreira, J. P. Carvalho, S. Oliveira, L. Coheur, P. Paulino, A. M. Veiga Simão, and I. Trancoso. 2019. Automatic cyberbullying detection: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior 93:333–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.021.

- Runions, K. C., and M. Bak. 2015. Online moral disengagement, cyberbullying, and cyber-aggression. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18 (7):400–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0670.

- Sakellaropoulo, M., and M. W. Baldwin. 2007. The hidden sides of self-esteem: Two dimensions of implicit self-esteem and their relation to narcissistic reactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (6):995–1001. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.009.

- Sanfilippo, M. R., P. Fichman, and S. Yang. 2018. Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. The Information Society 34 (1):27–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391911.

- Schau, H. J., A. M. Muñiz, Jr., and E. J. Arnould. 2009. How brand community practices create value. Journal of Marketing 73 (5):30–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.30.

- Shapiro, J. P., R. F. Baumeister, and J. W. Kessler. 1991. A three-component model of children’s teasing: Aggression, humor, and ambiguity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 10 (4):459–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1991.10.4.459.

- Simunjak, M., and A. Caliandro. 2019. Twiplomacy in the age of Donald Trump: Is the diplomatic code changing? The Information Society 35 (1):13–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1542646.

- Slonje, R., P. K. Smith, and A. Frisén. 2013. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior 29 (1):26–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024.

- Sobkowicz, P., and A. Sobkowicz. 2010. Dynamics of hate based Internet user networks. The European Physical Journal B 73 (4):633–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e2010-00039-0.

- Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., S. Ratneshwar, and S. Sen. 2012. Drivers of consumer-brand identification. International Journal of Research in Marketing 29 (4):406–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.001.

- Suler, J. 2004. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 7 (3):321–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295.

- Tanrikulu, T., H. Kinay, and O. T. Aricak. 2015. Sensibility development program against cyberbullying. New Media & Society 17 (5):708–19.

- Thompson, S. A., and R. K. Sinha. 2008. Brand communities and new product adoption: The influence and limits of oppositional loyalty. Journal of Marketing 72 (6):65–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.72.6.065.

- Underwood, R., E. Bond, and R. Baer. 2001. Building service brands via social identity: Lessons from the sports marketplace. Journal of Marketing 9 (1):1–13.

- Vazire, S., L. P. Naumann, P. J. Rentfrow, and S. D. Gosling. 2008. Portrait of a narcissist: Manifestations of narcissism in physical appearance. Journal of Research in Personality 42 (6):1439–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.06.007.

- Weiser, E. B. 2015. #Me: Narcissism and its facets as predictors of selfie-posting frequency. Personality and Individual Differences 86:477–81.

- Wooten, D. B. 2006. From labeling possessions to possessing labels: Ridicule and socialization among adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research 33 (2):188–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/506300.

- Xu, B., Z. Xu, and D. Li. 2016. Internet aggression in online communities: A contemporary deterrence perspective. Information Systems Journal 26 (6):641–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12077.

- Ybarra, M. L., and K. J. Mitchell. 2007. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 41 (2):189–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.005.

- Yeager, D. S., C. J. Fong, H. Y. Lee, and D. L. Espelage. 2015. Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: Theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 37:36–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005.