ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has shaken a foundational pillar of global capitalism: the organisation of work. A pivotal dimension of such re-organisation has been the classification of work as essential or not. This article explores the concept of essential work using a global feminist social reproduction perspective. We show that the meaning of essential work is more ambiguous and politicised than it may appear and, although it can be used as a basis to reclaim the value of socially reproductive work, its transformative potential hinges on the possibility to encompass the most precarious and transnational dimensions of (re)production.

RÉSUMÉ

La pandémie de COVID-19 a ébranlé l’un des piliers du capitalisme mondial : l’organisation du travail. Alors que les travailleurs avaient jusqu’ici été généralement classés en fonction de leurs compétences, pendant la pandémie, la catégorie de « travailleurs essentiels » a pris le devant. Cet article explore le concept de travail essentiel en appliquant une perspective globale et féministe à la question de la reproduction sociale. Nous démontrons que le sens de « travail essentiel » est plus ambigu et politisé qu’il ne paraît, et, bien qu’il soit utilisé dans le but de redonner de la valeur au travail de reproduction sociale, son potentiel transformateur dépend de sa capacité à inclure les dimensions les plus précaires et transnationales de la (re)production.

Introduction

“The conditions created by the pandemic drive home the fact that we essential workers – workers in general – are the ones who keep the social orders from sinking into chaos. Yet we are treated with the utmost disrespect, as though we’re expendable” wrote Sujatha Gidla on 5th May 2020 in the New York Times. She is a subway conductor in New York, who spoke about the slow and inadequate response of employers and authorities to ensure safer working conditions in the sector, leading to sickness and death among her fellow workers.

Taken up, for the most part, uncritically, as though holding intrinsic or intuitive validity and applicability, the categorisation of the workforce into essential and non-essential has been a pivotal dimension of the re-organisation of work at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as Ms Gidla’s words expose, there are tensions embedded in the notion of “essential work”, in particular that between the essentiality and disposability of essential workers. Thus, whilst the essential work category was adopted suddenly and without scrutiny, many questions remain unanswered. What constitutes essential work? Who are the essential workers? What and who are they essential for? Given the widespread adoption of this terminology and the associated legislation in many countries across the world, it is important to analyse the meanings, applications, implications, and, crucially, the transformative potential of categorisations of workers based on the notion of “essentiality”.

This article aims to investigate the notion of essential work through the use of a global feminist lens centred on social reproduction. It addresses two main questions. First, what is essential work and how has this terminology been used in different countries in the Global South and North? Through a review of the literature, decrees, policy documents and newspaper articles, we map the meanings of essential work across the world using as examples Brazil, Canada, England, India, Italy, Mozambique and South Africa. Second, taking as a starting point the claim made by social reproduction theorists that the recognition of devalued forms of work as essential offers a route to re-valorise socially reproductive work (Bhattacharya Citation2020; Stevano et al. Citationforthcoming), we ask whether this potential has been tapped so far and, if not, what limitations, omissions and contradictions are preventing so. The global perspective is complemented by a zoom-in on Mozambique as a low-income country in the Global South, occupying a peripheral position in global and regional economies and with a large share of vulnerable and essential workers. The illustrations of Mozambique are based on primary research on work in the agro-industry conducted by the authors prior to the pandemic, in combination with the review of newspaper articles, policy documents, observations and selected primary evidence during the pandemic.

Our analysis shows that the meanings of essential work are much more ambiguous, politicised and fungible than assumed. The global feminist social reproduction lens proves crucial to shed light on forms of essential work – unpaid and informal work – that are largely absent from the essential work classifications, an omission that denotes a productivist and Western bias in the understanding of work realities that make the notion of essential work ill-suited to regulate the organisation of work in low-income countries with a large informal economy and widespread precarity. In addition, the national framing of the essential work legislation makes it inadequate to address the transnational dimensions of work, particularly in peripheral contexts. On this basis, we argue that the transformative potential of the notion of essential work will remain untapped unless it can be used to enhance the working conditions of the most vulnerable workers on a global scale.

The next section outlines the conceptual framework centred on a global social reproduction lens that allows us to see how COVID-19 is a crisis of productive and reproductive work. We then map how essential work classifications have been used, who the essential workers are and what they are essential for; the last section concludes.

COVID-19 as a crisis of work through a global social reproduction lens

Initially a public health crisis, COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated a global crisis of productive and reproductive work across the globe. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has estimated that losses in working hours in the second quarter of 2020 were equivalent to 495 million full-time jobs (ILO Citation2020a) whilst informal workers, who make up around 90 per cent of employment in low-income countries, saw their earnings decrease by 60 per cent in the first month of the crisis (UN Citation2020a). Moreover, nearly three-quarters of the world’s domestic workers – over 55 million people – lost working hours or jobs in May (ILO Citation2020b). Attempting to limit the health effects of the crisis has therefore triggered immediate and severe disruptions to the organisation of work, making COVID-19 an unprecedented crisis of production and reproduction (Mezzadri Citation2020; Stevano et al. Citationforthcoming).

The crisis of work caused by COVID-19 is not merely a tragic consequence of a freak epidemiological event, but rather a manifestation of the existing systemic fragilities of capitalism. In the latter’s current iteration of globalised neoliberalism, capital’s expanded search for cheap labour in the periphery has led to the restructuring of global production and the fragmentation of the means of social reproduction of citizens in the Global South (Amin Citation1972; Cousins et al. Citation2018). This configuration maintains countries in the Global South, particularly those in Sub-Saharan Africa, as providers of low-value commodities (Amin Citation1972; UNCTAD Citation2019). Thus, whilst mainstream development discourse promotes participation in global value chains (GVCs) as a route to growth and prosperity, in reality workers in the Global South are “adversely incorporated” into GVCs (Phillips Citation2011), marginalised from them and pushed into survivalist forms of work (Meagher Citation1995; Pattenden Citation2016) that are subsidiary to global production (Bernards Citation2019). This structure continues the legacy of colonialism and reproduces relations of dependence, which maximise the extraction of surplus in the Global South (Emmanuel Citation1972; Nkrumah Citation1965; Sylla Citation2014). The super-exploitation of workers through various mechanisms of the devaluation of work are central to relations of unequal exchange (Emmanuel Citation1972; Elson and Pearson Citation1981).

Feminists have long been engaged in the study of forms of work that are systematically devalued in capitalist systems (see Ferguson Citation2019); in some cases, to the extreme of being denied the denomination of work altogether (Bhattacharyya Citation2018; Dalla Costa and James Citation1972). The devaluation of work overwhelmingly performed by women – though not exclusively – is central to processes of capital accumulation on a global scale. Mies (Citation1986) discusses how global processes of primitive accumulation hinged on the exploitation of nature, colonisation and the subordination of women. Whereas colonisation underpins the international division of labour, “housewifization” structures the household division of labour (Mies Citation1986). An important mechanism through which women’s work has been devalued and depoliticised is through its relegation to the home, which is constructed as a private sphere distinct from the so-called public sphere and governed by altruism and love (Folbre Citation1986; Elias and Roberts Citation2016).

Importantly, the devaluation of work typically performed by women does not stop at the fictitious boundaries of the household, but transcends into the labour markets encompassing various forms of commodified work that are constructed as low-skill and low-productivity occupations. Although some strands of feminism, especially White, have focused on the oppression of women through their roles as housewives, mothers and carers in the home, Black feminists have long argued that women are oppressed as labourers and the home itself has been a site of poorly paid, not unpaid, work for women of colour working as domestic workers (Davis Citation1983; Glenn Citation1992). Mies (Citation1986) does recognise that, differently from white women, women of colour in the former colonies could not afford to be housewives because their engagement in wage and paid work contributed to the family’s survival and global capital’s extraction of value. In addition, in the Global South, the separation between sites of production and reproduction is much more blurred and often various types of wage work are outsourced to home-based workers and other locations outside the factory (Mies Citation1982; Mezzadri and Fan Citation2018). These patterns hold true for many workers in the contemporary Global South, which we will illustrate below using the example of Mozambique.

With the possibility of reproducing through self-subsistence increasingly being eroded in the Global South, another strategy for reproduction under globalisation for some is to migrate for employment, frequently to ex-coloniser countries. For women migrants, this work is typically in the reproductive sectors of care, health and domestic work. The “international division of reproductive labour” (Parreñas Citation2005, 237) mirrors the neo-colonial structure of productive work, as emotional surplus value is extracted from migrant women of periphery countries, who leave behind their own families to care for others in the core (Murphy Citation2014). These dynamics are not only global but are also driven by regional and national systems of accumulation, hinging on various forms of gendered migration that underpin the reconfiguration of productive and reproductive work on grounds of gender, race and class (O’Laughlin Citation1998).

The redistribution of care resources, both globally and locally, exacerbate strained care systems, which are central to social reproduction but have been critically underfunded in the context of privatisation encouraged by the International Financial Institutions (Kentikelenis, Stubbs, and King Citation2015; O’Laughlin Citation2016; Simeoni Citation2020). The restructuring of health care systems has entailed the deterioration of working conditions for health-care workers in countries such as Tanzania and South Africa, which led to the migration of these workers to richer countries in the Global North (Valiani Citation2012). Valiani (Citation2012) documents how the out-migration of nurses created shortages of nursing labour in African countries, thus amounting to a form of accumulation by dispossession.

Although most often treated distinctly, the dynamics of global production and reproduction are mutually constituted and in tension (Katz Citation2001). Taking a social reproduction approach means centring this dialectical relation to understand the reproduction of life and labour within global capitalism; in particular, to assess the notion of “essential work”, we draw on the social reproduction perspectives that are concerned with social reproductive dynamics of labour processes and relations (Mies Citation1986; Mezzadri Citation2019). These approaches highlight how the interdependence of production and reproduction is visible through both everyday life practices shaping the gendered organisation of productive and reproductive work, and through the historical essentiality of cheap and unpaid productive and reproductive work for capital accumulation, which currently encompasses under-paid global supply chain and domestic work as well as unpaid (care) work. In this sense, gender is a key relation in the dynamics of social reproduction but not one that operates in isolation from relations of class, race and citizenship status (Mies Citation1986; Bannerji Citation2011; Bhattacharyya Citation2018).

COVID-19 triggered a crisis of productive and reproductive work in this already fragile global picture. The disruption of work has involved the re-charting of work practices, a pivotal determinant of which has been the categorisation of work as essential or not. During lockdowns, essential workers were required to continue working despite increased exposure to COVID-19 and without adequate or increased compensation. For non-essential workers, various forms of reorganisation took place. Some have shifted to home-based work; however, regional variations in the percentage of workers who can transition to home-based work are striking, ranging from 6 per cent in Sub-Saharan Africa to 30 per cent in North America and Western Europe (Berg, Bonnet, and Soares Citation2020). Thus, the potential for home-based working is unevenly distributed and all but irrelevant for many workers in the Global South.

For non-essential workers who have been unable to work from home, outcomes have ranged from being furloughed through state provided job retention schemes to becoming unemployed. In the Global North, state investment in varying degrees has provided a security net for many of these workers. Yet, an estimated 55 per cent of the world’s population is unprotected by social protection programmes (ILO Citation2017). Whilst many governments in the Global South have attempted to provide some kind of social security net, for most low-income countries, support to mitigate lost incomes is inadequate due to limited government revenue (ILO Citation2017; Citation2020c) and undermined by the transfer of risk to workers at the bottom of disrupted global supply chains (Anner Citation2020). Faced with drastic alternatives between dying from hunger or from the virus, informal vendors with support from the Human Rights Defenders Coalition in Malawi were successful in lobbying the High Court to block the Government’s intended 21-day lockdown, so that citizens could continue to earn their living (Goitom Citation2020).

In parallel, reproductive work has intensified owing to heightened health care needs and overwhelmed hospitals, where health care capacity has been strained by the over-exposure of health care workers to the disease, school closures and the increased care needs of older people (UN Citation2020b). In essence, the burden of social reproduction has been further transferred and relegated to the home, thus deepening the long-term process of privatisation of social reproduction under neoliberalism (Bakker Citation2007; Stevano et al. Citationforthcoming). This shift has triggered renegotiation of reproductive work within families and households, with societal implications for the distribution of socially reproductive work and increased challenges for those facing difficulty in combining productive and reproductive work, such as households with children, single parents and essential workers.

Thus, the re-organisation of productive work has ramifications for reproductive work, and vice versa. Crucially, the globalised nature of production and reproduction has meant that even in countries that did not have to bring their economies to a halt because the COVID-19 public health crisis was not as acute, the economic repercussions have been nonetheless felt through the disruption of global (re)production networks.

What is essential work?

Despite the significant social reproduction implications of a worker being classified as essential or not, prior to the pandemic the concept of essential workers appears in the literature sparsely and diffusely – typically during periods of crisis or exceptional circumstances – rather than as a universally recognised category of work. One of the earliest uses of the essential worker terminology appears during war-time periods and refers to workers that were needed domestically to “produce the necessary goods for civilian and military use” and were therefore exempt from military service (Dewey Citation1984, 214). In the UK, Essential Worker Orders allowed the Government to divert military conscripts and women into essential industries such as mining, manufacturing, transport, agriculture and public services and employers were prohibited from sacking those covered by the Orders (O’Hara Citation2007). More recently, references to essential and key workers in the literature have been made during other isolated events such as government shut-downs in the USA (Baker and Yannelis Citation2017), natural disasters (Whittle et al. Citation2012), and previous pandemics (Maunder Citation2004; Gershon et al. Citation2010).

There are some instances in the literature where the terms are used universally across countries, however, nuances exist which prevent a universal conceptualisation of essential work from arising.Footnote1 For example, essential services are globally understood as specified groups of workers that are prohibited from strike action when doing so would be “a clear and imminent threat to the life, personal safety or health of the whole or part of the population” (ILO Citation2018, Article 836). However, what constitutes an essential service varies by country and circumstance (Knäbe and Carrión-Crespo Citation2019). Similarly, within the immigration policies of several countries, workers with “essential skills” are eligible for employment visas, but which jobs are essential is dependent upon whichever skills are in short supply domestically. Additionally, key workers are globally understood as low-to-average paid public employees who provide essential local services (nurses, police men, social workers etc) (Monk and Whitehead Citation2011). However, the literature focuses exclusively on “the key worker problem”, that is, the inability of key workers to afford housing in high-cost areas, resulting in concerns over the supply of essential services (Adeokun and Isaacs-Sodeye Citation2014). Thus, the literature offers little consensus over who an essential worker is and what they are essential for.

The lack of universal conceptualisation surrounding essential workers has also been apparent during the pandemic. We analyse the use of essential work classifications in seven countries across the Global South and North: Brazil, Canada, England, India, Italy, Mozambique, and South Africa, as shown in .Footnote2

Table 1. Essential work classifications in Brazil (BR), Canada (CA), England (EN), India (IN), Italy (IT), Mozambique (MZ) and South Africa (SA).

The selected countries have only 13 out of 53 essential work categories completely in common. The remaining categories are designated as essential in varying degrees across the countries. Following their unique geographical and economic contexts, essential workers include those employed in: agriculture, forestry and aquaculture in Canada, India, Italy, Mozambique and South Africa; natural disaster monitoring in Brazil, India and South Africa; and mining in Brazil, Canada, India, Italy and South Africa. In terms of manufacturing, all countries permit the production of inputs that are necessary for essential goods and services, whilst Brazil permits all industrial activities. Whilst the production and sale of food is listed as essential in all countries, Canada explicitly permits take-aways and food-delivery services, whilst South Africa allows hot-cooked food to be sold by delivery only.

At the same time, some countries fail to include seemingly crucial work categories. For instance, England does not explicitly list cleaning, janitorial or sanitation services as essential, whilst Brazil and Mozambique do not list carers. Brazil also revoked waste disposal services from its official decree (Brazil Official Guidance Citation2020, Article IX). Only England and Canada list childcare services, the former with no restrictions, and the latter restricted this to child care for essential workers or home child services of less than six people. Italy and Canada list accommodation and real estate services without any restrictions, whilst India and South Africa list hotel and accommodation services for essential workers only, whereas Brazil, England, and Mozambique do not make explicit reference to housing in their lists. Only South Africa and Italy list paid domestic work, with the former restricting this to live-in staff only.

Some countries have chosen to qualify what constitutes an “essential good” such as South Africa, others have made the definition intentionally ambiguous, as in the UK. This has meant that in the UK, for instance, Amazon has been able to exploit the category of essential work to force its employees to continue working in an unsafe environment, despite them shipping non-essential items such as lawnmowers (Munbodh Citation2020). In India, rather than companies stretching the boundaries of essential work, certain states have instead attempted to make businesses exempt from labour laws, such as occupational health and safety and freedom of association, and brought in measures that permit them to hire and fire at will (Obhan and Bhalla Citation2020). In Italy, the list of essential productive activities was the object of intense debate and negotiations among the government, the representatives of firms and the trade unions (Baratta Citation2020; Conte Citation2020). Thus, the presumed objectivity of essentiality is in fact politically negotiated and reflective of power relations between capital and labour, mediated by the state.

In Mozambique, 88 per cent of the workforce is informal and 66 per cent work (waged and/or unwaged) in agriculture (INE Citation2019); thus, in a crude and approximate way, this indicates that two thirds of the workforce is essential. However, two dynamics that characterise how the legislation on essential work was developed point to some important limitations. First, a top-down approach was taken and the legislation was passed with no consultation from trade unions, whose participation has been restrained to minimum wage negotiations in the narrow formal sector. Second, the essential work decrees reveal a detachment between the broader legislation governing labour markets and the reality of a productive structure of the economy dominated by irregular, informal, unstable and unsecure forms of work. An investigation into the reasons for such detachment are beyond the scope of the article, but various literature has documented the neglect and poor understanding of labour markets perpetuated through neoliberal development agendas in Mozambique (Oya Citation2013; Ali Citation2017). It appears that the classification of essential work was based on so-called “general” or “traditional” criteria of activities that are “naturally seen as being essential to daily life, such as health, pharmacy and laboratory services, sale of foods and other basic wage goods and services”.Footnote3 In addition, according to the National Inspection of Economic Activities (INAE), the classification of essential activities within the food chain was intentionally broadly defined to allow for context-specific variations,Footnote4 which also suggests differences in labour relations and employer-worker power relations across the country. In essence, the essential work legislation adopted in Mozambique is at odds with the reality of work in the country, which creates blind spots and limitations that we will discuss in Section 5.

In sum, the essential work category has been deployed in scattered and heterogenous ways prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and, largely, its varying uses have continued during the pandemic. Although the notion of essentiality appears to bear a universal validity that captures activities that are necessary to sustain life, the uses of the essential work category reveal a degree of fungibility that reflects its political and socio-economic underpinnings. We now turn to questioning who the essential workers are.

Who are the essential workers?

Whilst there is a lack of consensus over which occupations are essential, there is general agreement that these jobs are low-paid and disproportionately performed by people of colour, women and migrants. In the UK’s capital, workers from Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) background make up a disproportionately large share of essential worker sectors, including 54 per cent of food production, process and sale workers and 48 per cent of health and social care workers (The Health Foundation Citation2020). In the food sector, 30 per cent of workers were born outside the UK, rising to almost half of food workers under the age of 40 (Farquharson, Rasul, and Sibieta Citation2020). Moreover, women represent 60 per cent of essential workers in the UK, despite only making up 43 per cent of regular workers, and make up a staggering 80 per cent of social care and education sector key workers (Farquharson, Rasul, and Sibieta Citation2020). Across the board, essential workers are more likely to be low-paid than their non-essential counterparts, with 38 per cent of essential workers earning below £10 an hour compared with 31 per cent of non-essential workers (TUC Citation2020). The proportion of workers earning less than £10 an hour strikingly rises to 71 per cent of food sector workers and 58 per cent of social care workers (Farquharson, Rasul, and Sibieta Citation2020). Front-line care workers are also 5 times as likely to be on a zero-hour contract, compared to all workers (Cominetti, Gardiner, and Kelly Citation2020).

In Brazil, 63 per cent of domestic workers are Black women, less than 30 per cent of domestic workers have formal contracts, with an even lower proportion for Black workers, and more than 2 million are undocumented workers who receive an average wage of $17 a day (Pinheiro et al. Citation2019). In India, it is estimated that over 90 per cent of sanitation workers belong to the lowest Dalit sub-castes (Bhatnagar Citation2018). Across the Global South, work at the origin of agri-food chains is notoriously low-paid and internally fragmented, with the lowest-paid and most precarious segments often taken up by women and migrants (Tallontire et al. Citation2005; Selwyn Citation2014). In Mozambique, pay and working conditions in the agro-industry are very poor, with workers often paid below the sectoral minimum wage owing to the use of production targets that are very difficult to meet and weak enforcement of employment contracts (Stevano and Ali Citation2019). In addition, the legislation on sectoral minimum wages itself allocates lower wages to various essential occupations in relation to non-essential ones, with the exception of the production and distribution of electricity and water, and financial services (see ). The monthly wages of workers in agriculture, health care (nurses) and public administration are at the bottom of the scale.

Table 2. Sectoral monthly minimum wages in Mozambique.

The pandemic has therefore made strikingly visible the key tensions of social reproduction. Firstly, work which is essential for reproducing life is work that is typically seen as low-skilled and has been systematically under-valued. Secondly, the over-representation of women and minority groups in essential worker roles is a manifestation of the historical tendency of capitalism to differentiate, not homogenise, the working classes (Sanyal Citation2007; Bhattacharyya Citation2018) and of labour markets to be bearers of inequalities (Elson and Pearson Citation1981). If the primary aim of the economy were to ensure social provisioning, as advocated by feminist economists (Power Citation2004), work would be assessed based on its contributions to collective well-being, thus entailing a shift in what societies should value; the question remains whether the notion of “essentiality” can contribute to such a shift.

Essential for what? Tensions between reproducing life and reproducing exploitative relations

The recourse to the essential work category during the pandemic was intended to ensure the reproduction of life and that of capital, both to a degree, while significant parts of the economy were shut down. But can we re-valorise the reproduction of human life without reproducing capitalist relations of exploitation?

A significant limitation of the essential work classifications is their focus on formal and paid work, which excludes much work that is essential for the reproduction of life taking place in the informal economy and on an unpaid basis. This narrow focus reflects both a productivist and a Western bias: the former obscures the centrality of significant parts of reproductive work that regenerate life, the latter conceals the work realities of the vast majority of the working population in the Global South because it suggests that workers have one main occupation whilst livelihoods are most often constructed on a multiplicity of occupations. We will detail how these biases make the notion of essential work inconsequential and ill-suited in the Mozambican context.

The majority of the Mozambican workers are considered to be essential but the re-organisation of work has resulted in disrupted and destroyed livelihoods due to the failure of the governments to provide alternatives. For example, informal goods and food markets in the capital city of Maputo have been temporarily closed and street vendors removed from the streets, despite their resistance, to prevent the spread of the virus. These interventions of so-called “requalification” were accompanied by the promise that informal market and street vendors will be given new spaces to run their activities but the government has not yet fulfilled this promise. Many vendors of essential products such as foodstuff, who are women, have therefore been left without a livelihood and do not have access to social protection (O País Citation2020).

The extractive productive structure, highly concentrated in natural resources and primary commodities for export, with weak or no linkages to other sectors of the economy, is unable to generate regular, stable and secure work opportunities (Castel-Branco Citation2014). Historically, work structures and labour markets have been multiple and interconnected as working people have had to shoulder the responsibility for social reproduction (O’Laughlin Citation1981; Oya, Cramer, and Sender Citation2009), but the commodification of life and the associated fragmentation of the means of social reproduction have intensified households’ necessity to resort to multiple precarious and low-paid forms of work over time (Cousins et al. Citation2018). This creates a vicious cycle whereby productive structures skewed towards extraction and exports of primary commodities in combination with a very limited welfare regime underpin the existence of precarious work and, in turn, workers’ necessity to engage in multiple forms of work subsidises capitalist production for export, thus maintaining poor working conditions in wage work.

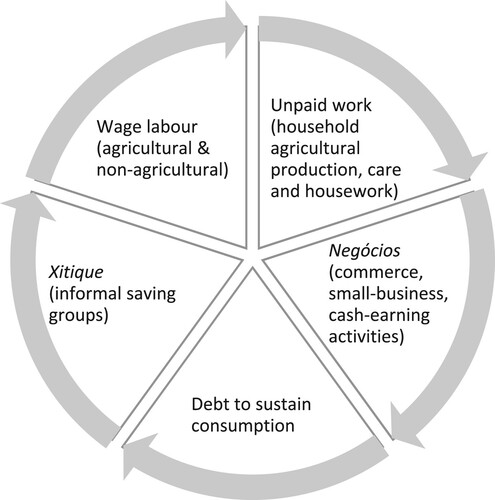

This vicious cycle can be seen through the everyday organisation of the working lives of workers in the agro-industry. illustrates, in a simplified manner, the interdependent nature of various forms of work, and how they are embedded in practices of debt and savings management. From these interconnections, two important insights emerge: first, wage work in the agro-industry cannot be understood in isolation from other types of work and money flows; second, a crisis in one of these domains has effects on others, with the potential to impact individual and household well-being.

Figure 1. Interdependence of wage and reproductive work through money flows.

Source: Ali and Stevano (Citation2019), based on semi-structured interviews with workers in the Mozambican agro-industry (forest plantations and cashew processing factories).

Income from wage work enables agro-industry workers to: (i) finance consumption of wage goods, (ii) partly acquire food through purchase, (iii) have an investment base in alternative productive activities, including the financing of their own farm and (iv) respond to shocks. Informal savings groups (xitique) with colleagues at work provide a social safety net in case of unexpected events and are used to make investments in parallel cash-earning activities.

These dynamics of interdependence are not limited to the agro-industry but shape working lives marginalised from global production networks and, anecdotal and scattered evidence suggests, in the public sector too, as exemplified by this quote that highlights the problem of low wages for health care workers in the public sector:

We sacrifice our lives, but there [in the public hospital] there is no life … For instance, I have to do other activities to help our livelihood including small-scale agricultural production […] Given the low wages, I had the opportunity to move to a private hospital where I currently receive nearly three times as much as the wage in the public hospital and have better working conditions. (Interview with male nurse, 50 years old, former nurse in a public hospital, currently working in a private hospital in Maputo, 7th July 2020)

Where labour markets are so segmented and various realms of production and reproduction so interconnected, the use of the essential work category needs to account for diverse and intersecting working lives. On the one hand, the divides between formal and informal need to be overcome to offer social protection to essential workers in both the formal and informal economies (Castel-Branco Citation2020). On the other hand, the interdependence of occupations means that the interrelations between essential and non-essential work are much tighter, in fact they are often embodied by the same worker. Thus, the use of the essential work classification needs to account for these work realities.

It is evident that simply branding some forms of work as essential while not ensuring better pay, working conditions and health protection for the workers is not only tokenistic but in fact harmful. Whilst the importance of essential workers is recognised, their disposability is reinforced by asking them to continue to work amidst lack of safety and inadequate protective equipment (Gidla Citation2020). In addition, where the disposability of workers hinges on their engagements in multiple forms of work, the notion of essentiality needs to account for this too. The structural precarity of work is upheld by a system of exploitation and oppression, reproduced through international relations of exchange and national regulation, that, unless put into question by the essential work definition, risks being replicated through the definition of an essential production boundary that suffers from a productivist and a Western bias. If recognising the essentiality of work cannot counter the fragmentation of working lives, then the predominant conditions of exploitation are perpetuated.

A second limitation of the essential work classifications pertains to the narrow applicability of the essential work category to labour processes circumscribed by national boundaries, often accompanied by further divides between citizen and migrant labour. This is a significant shortcoming that, unless addressed, will reproduce the underlying relations of dependence and oppression that shape exchange between countries, especially South–North relations, and the gendered and racialised fragmentations of the working classes across and within countries.

Contemporary systems of production and reproduction have a globalised nature, as outlined in section 2, which implies that the organisation of work through control regimes as well as the ability of workers to collectively organise and bargain for better working conditions are determined through the interplay of various actors – the state, workers and capital – operating both nationally and transnationally (see for example Selwyn Citation2014; Pattenden Citation2016; Baglioni Citation2018; Mezzadri and Fan Citation2018; Hardy and Hauge Citation2019). The recognition of the interdependent nature of work needs to be accompanied by an understanding of the interactions between local and transnational dynamics of capital accumulation. In other words, it is necessary to disembed the notion of essentiality from the practice of methodological nationalism, both conceptually and in policy terms. The need to overcome methodological nationalism, defined as the study of economic processes as driven by internal factors seen as separated from external ones (Pradella Citation2014), has been articulated in studies of migrant labour (Hanieh Citation2015; Pradella and Cillo Citation2015). How the essential work classification is deployed needs to be assessed against this backdrop, where the transnational dimensions of the fragmentation and dependence of the global working classes include migrant labour and encompass the livelihoods of households and communities linked to migrant labour and migratory flows. Although some of these circuits have been severely disrupted at the beginning of the pandemic, as discussed in Section 2, it is also evident that reliance on migrant labour and global network of (re)production has not ceased so far – in fact some governments have acted to ensure access to migrant workers, as outlined below. Ultimately, the long-term restructuring of these dynamics will depend on the duration of the pandemic and the responses to it in later phases.

In Mozambique, within-country mobility of workers is crucial to various forms of labour. For instance, the disrupted mobility of traders across the country, price fluctuations driven by demand bottlenecks, and famers’ reduced ability to mobilise labour owing to the lower mobility of people all contribute to create negative impacts for Mozambican farmers that were visible already at the beginning of the pandemic (Zamchiya, Ntauazi, and Monjane Citation2020). In addition, the scarce employment opportunities generated by the extractive economy has underpinned a long-term flow of migrants to South Africa. With the imposition of the lockdown in South Africa, over 14,000 Mozambican migrants returned to Mozambique (IOM Citation2020) and the consequences for the livelihoods of those reliant on remittances are likely to be severe, although the current lack of data and studies prevent our ability to outline the exact impacts. Globally, remittances have grown much faster than FDI in the last decade and have constituted a mechanism of support for countries in the face of economic shocks; the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that global remittances will collapse by 20 per cent, which constitutes a global threat (Sayeh and Chami Citation2020). Thus, the disrupted mobility of workers and goods within countries and across countries alongside the limited fiscal capacity of a low-income country such as Mozambique has not offered protection to essential workers.

On the other hand, difficulties in recruiting migrant labour have emerged in receiving countries. The UK faces a shortage of at least 90,000 workers in the food sectors and, in response to this challenge, the recruitment practices have become more ruthless and less regulated, with workers reporting at best mixed practices in regard to the implementation of COVID-19 measures on the workplace (Barnard, Costello, and Butlin Citation2020). Similar shortages and dubious practices inrecruiting migrant workers have been documented across Europe (Rogozanu and Gabor Citation2020). The Italian government developed a proposal for the “regularisation” of migrant agricultural and domestic workers who have been living and working in the country illegally, which has been strongly opposed by the agricultural workers for failing to encompass many workers for bureaucratic reasons and for arbitrarily including the workers of essentially two sectors while excluding others (Gaita Citation2020). During the pandemic, the UK government preliminarily passed a new Immigration Bill that would make many migrant essential workers ineligible for work visas (Syal Citation2020). In India, the plight of millions of migrant workers suddenly left with no livelihood nor protection in the urban areas forced them to defy the lockdown and return to the native rural areas (Shah and Lerche Citation2020). While the pandemic has made this vulnerable and hidden workforce more visible (Shah and Lerche Citation2020) and parts of this workforce recognised as essential, this has not translated into better and safer working conditions for these workers.

In sum, the essential work classifications have recognised certain workers as indispensable but have not been used to subvert the relations of power that make them disposable. Even if the work of essential workers has certainly contributed to reproduce life during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as it always does, the significant omissions that are visible through a global social reproduction lens demonstrates that the vast majority of vulnerable workers have not had their conditions of reproduction safeguarded. Their expulsion from work, despite their essentiality, and relegation to highly precarious livelihoods reproduces and in fact aggravates existing dynamics of exploitation.

Conclusions

This article investigated the notion of essential work through a global feminist lens centred on social reproduction and used Mozambique as an example of a low-income country in the Global South situated in a peripheral position in global and regional economies to assess the use, applicability and consequentiality of the essential work classifications. Three main findings emerge. First, contrary to what may have appeared from newspaper headlines and government announcements, the essential work classifications has been deployed differently across countries, reflecting specific socio-economic contexts and political decisions bearing relations of power between the state, capital and workers.

Second, a social reproduction perspective shows that many types of essential work are forms of socially reproductive work necessary for the reproduction of life that nonetheless have been systematically under- and devalued in global capitalist systems. However, both unpaid reproductive and informal work are largely excluded from the essential productive boundary. This means that, in the ways in which the essential work classifications have been used so far, the productivist and Western biases of work are reinforced, making the notion of essential work particularly ill-suited and inconsequential in low-income peripheral economies. In addition, and finally, these legislations do not recognise the interplay between national and transnational actors and dynamics in shaping labour markets and labour relations. Thus, the relations of dependence between core and peripheral countries in global and regional economies substantially limit the ability of peripheral countries to protect essential workers through national legislation, whilst the fragmentation of the working classes is reproduced through the continued exploitation of migrant workers.

The essential work categorisation has been deployed by governments in tokenistic and politicised ways, which has had the effect of jeopardizing the working conditions of essential workers by making them more vulnerable to the disease and treating them as disposable. Of course the notion of essentiality ought to be used to advance a political argument that these workers need to be recognised and rewarded enhanced socio-economic status through better pay and working conditions, which may happen in the future depending on collective mobilisation on these issues.

However, some important caveats remain. In addition to the dangers of creating a working class divided between essential and non-essential as posited by Bergfeld and Farris (Citation2020), the notion of essentiality also risks perpetuating relations of dependence between peripheral and core economies, as well as working classes, unless it is deployed to protect the most vulnerable workers – unpaid workers, the global reserve army of labour in the informal economy particularly in the Global South, and migrant workers. This entails a better understanding of socially reproductive work in the Global South and the development of an internationalist narrative cognizant of relations of unequal exchange. Only a radical re-framing of global relations of production and reproduction can ensure that peripheral economies can deploy essential work legislation to effectively protect the lion’s share of essential workers globally.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the time that the interviewees in Mozambique – the workers in particular – have given to us. We would like to thank the guest editors of the special issue – Yannis Dafermos, Tobias Franz and Elisa Van Waeyenberge – and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sara Stevano

Sara Stevano is a Lecturer in Economics at SOAS University of London. She is a development and feminist political economist specialising in the study of the political economy of work, well-being (food and nutrition), households and development policy. Working at the intersections between political economy, development economics, feminist economics and anthropology, Sara takes an interdisciplinary approach to theories and methods. Her work focuses on Africa, with primary research experience in Mozambique and Ghana.

Rosimina Ali

Rosimina Ali is a researcher at the Institute for Social and Economic Studies (IESE), in Maputo. Her research is focused on the political economy of labour markets, social reproduction, economic transformation and dynamics of capital accumulation with particular focus in Mozambique. She completed her MSc in Development Economics (SOAS, University of London), and holds a graduate degree in Economics (Faculty of Economics, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo).

Merle Jamieson

Merle Jamieson is a Research Assistant at SOAS University of London and was previously an ODI Fellow in the Ministry of Agriculture in Malawi. She completed her MSc in Development Economics at SOAS, focusing her research on labour markets and the political economy of agriculture.

Notes

1 There are additional universal yet non-relevant uses of these terms in the literature: front-line workers refers to customer-facing employees in the retail and hospitality sectors (Karatepe et al. Citation2010) and ‘street-level’ public service employees (Blomberg et al. Citation2015; Magadzire et al. Citation2014), and a key worker is a specific support role for vulnerable people (McKellar and Kendrick Citation2013).

2 We utilise the essential worker lists provided by countries during their highest level (most stringent) lockdowns whereby only those listed were officially permitted to continue working, however, these lists were subject to change throughout the pandemic. These are as follows: Brazil (Brazil Official Guidance Citation2020), Canada (Canada Official Guidance Citation2020b), England (UK Official Guidance Citation2020b), India (India Official Guidance Citation2020), Italy (Italy Official Guidance Citation2020), Mozambique (Republic of Mozambique Citation2020), South Africa (South Africa Official Guidance Citation2020).

3 Interview with public official at the State Secretariat for Youth and Employment (SEJE), 17th September 2020, Maputo.

4 Based on personal communication with INAE inspector at a webinar on “Clarifying the State of emergency in the Business Sector”, 23rd June 2020, Maputo.

References

- Adeokun, Cynthia, and Folake Isaacs-Sodeye. 2014. “Delivering Affordable Dwellings for Key Workers: The Shared-Ownership Option in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Proceedings 8th Construction Industry Development Board (Cidb) Postgraduate Conference, 10–11 February 2014, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, edited by S. Laryea and E. Ibem, 1–7. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- Ali, Rosimina. 2017. “Mercados de trabalho rurais: porque são negligenciados nas políticas de emprego, pobreza e desenvolvimento em Moçambique?” In Emprego e transformação económica e social em Moçambique, edited by R. Ali, C. Castel-Branco, and C. Muianga, 63–86. Maputo: IESE.

- Ali, Rosimina, and Sara Stevano. 2019. Work in the Agro-Industry, Livelihoods and Social Reproduction in Mozambique: Beyond Job Creation. IDeIAS Bulletin no. 121e. Maputo: Institute of Social and Economic Studies (IESE).

- Amin, Samir. 1972. “Underdevelopment and Dependence in Black Africa—Origins and Contemporary Forms.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 10 (4): 503–524.

- Anner, Mark. 2020. “Abandoned? The Impact of Covid19 on Workers and Businesses at the Bottom of Global Garment Supply Chains.” Research Report, Penn State Center for Global Workers’ Rights, March.

- ATECO. 2007. “ATECO (Classification of Economic Activity) 2007.” Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.istat.it/en/archivio/17959.

- Baglioni, Elena. 2018. “Labour Control and the Labour Question in Global Production Networks: Exploitation and Disciplining in Senegalese Export Horticulture.” Journal of Economic Geography 18 (1): 111–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx013.

- Baker, Scott R., and Constantine Yannelis. 2017. “Income Changes and Consumption: Evidence from the 2013 Federal Government Shutdown.” Review of Economic Dynamics 23: 99–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2016.09.005.

- Bakker, Isabella. 2007. “Social Reproduction and the Constitution of a Gendered Political Economy.” New Political Economy 12 (4): 541–556.

- Bannerji, Himani. 2011. “Building from Marx: Reflections on ‘Race,’ Gender, and Class.” In Educating From Marx, edited by Shahrzad Mojab and Sara Carpenter, 41–60. Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Baratta, Lidia. 2020. “Niente sciopero. Accordo raggiunto con i sindacati: le produzioni non essenziali chiuderanno.” Linkiesta, March 25. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.linkiesta.it/2020/03/italia-coronavirus-accordo-sindacati-produzioni-non-essenziali-chiuderanno/.

- Barnard, Catherine, Fiona Costello, and Sarah Fraser Butlin. 2020. “Working Conditions of Migrant ‘Key Workers’ in the COVID-19 Crisis.” The UK in a Changing Europe, April 8. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/working-conditions-of-migrant-key-workers-in-the-COVID-19-crisis/#.

- Berg, Janine, Florence Bonnet, and Sergei Soares. 2020. “Working from Home: Estimating the Worldwide Potential.” Vox Column, May 11. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://voxeu.org/article/working-home-estimating-worldwide-potential.

- Bergfeld, Mark, and Sara Farris. 2020. “The COVID-19 Crisis and the End of the ‘Low-skilled’ Worker.” Spectre Journal, May 10. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://spectrejournal.com/the-COVID-19-crisis-and-the-end-of-the-low-skilled-worker/.

- Bernards, Nick. 2019. “Placing African Labour in Global Capitalism: the Politics of Irregular Work.” Review of African Political Economy 46 (160): 294–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2019.1639496.

- Bhatnagar, Nirat. 2018. “The Harsh Reality of Life for India’s 5 Million Sanitation Workers.” Quartz India. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://qz.com/india/1254258/sanitation-workers-a-five-million-people-large-blind-spot-in-india/.

- Bhattacharya, Tithi. 2020. “Social Reproduction Theory and Why We Need It to Make Sense of the Coronavirus Crisis.” April 2. Accessed May 10, 2020. http://www.tithibhattacharya.net/new-blog/2020/4/2/social-reproduction-theory-and-why-we-need-it-to-make-sense-of-the-corona-virus-crisis?fbclid=IwAR01W8_L8EWNN4nD2whbT_9ghIp7p8kPo5lQbdgsP8HC53Cp6NTuNl5ZVdc.

- Bhattacharyya, Gargi. 2018. Rethinking Racial Capitalism. Questions of Reproduction and Survival. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Blomberg, Helena, Johanna Kallio, Christian Kroll, and Mikko Niemelä. 2015. “What Explains Frontline Workers’ Views on Poverty? A Comparison of Three Types of Welfare Sector Institutions.” International Journal of Social Welfare 24 (4): 324–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12144.

- Brazil Official Guidance. 2020. “Decree No. 10,282, of March 20, 2020.” Accessed July 7, 2020. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2019-2022/2020/Decreto/D10282.htm.

- Canada Official Guidance. 2020a. “Guidance for a Strategic Approach to Lifting Restrictive Public Health Measures.” aem. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/lifting-public-health-measures.html.

- Canada Official Guidance. 2020b. “Guidance on Essential Services and Functions in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/ntnl-scrt/crtcl-nfrstrctr/esf-sfe-en.aspx.

- Castel-Branco, Carlos Nuno. 2014. “Growth, Capital Accumulation and Economic Porosity in Mozambique: Social Losses, Private Gains.” Review of African Political Economy 41 (sup1): S26–S48.

- Castel-Branco, Ruth. 2020. O Trabalho e a Protecção Social num contexto do Estado de Emergência em Moçambique. IDeIAS Bulletin no. 125. Maputo: Institute of Social and Economic Studies (IESE).

- Cominetti, Nye, Laura Gardiner, and Gavin Kelly. 2020. “What Happens After the Clapping Finishes?” Resolution Foundation. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/what-happens-after-the-clapping-finishes/.

- Conte, Valentina. 2020. “Confindustria al governo: ‘Non si può chiudere tutto’. Sindacati: ‘Pronti allo sciopero generale’.” La Repubblica, March 22. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.repubblica.it/economia/2020/03/22/news/caos_serrata_confindustria_al_governo_non_si_puo_chiudere_tutto_scrivete_bene_il_decreto_-251987770/.

- Cousins, Ben, Alex Dubb, Donna Hornby, and Farai Mtero. 2018. “Social Reproduction of ‘Classes of Labour’ in the Rural Areas of South Africa: Contradictions and Contestations.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5–6): 1060–1085.

- Dalla Costa, Maria Rosa, and Selma James. 1972. The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. London: Falling Wall Press.

- Davis, Angela. 1983. Women, Race, and Class. New York: Vintage.

- Dewey, P. E. 1984. “Military Recruiting and the British Labour Force During the First World War.” The Historical Journal 27 (1): 199–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X0001774X.

- Elias, Juanita, and Adrienne Roberts. 2016. “Feminist Global Political Economies of the Everyday: From Bananas to Bingo.” Globalizations 13 (6): 787–800.

- Elson, Diane, and Ruth Pearson. 1981. “‘Nimble Fingers Make Cheap Workers’: An Analysis of Women's Employment in Third World Export Manufacturing.” Feminist Review 7 (1): 87–107.

- Emmanuel, Arghiri. 1972. Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Farquharson, Christine, Imran Rasul, and Luke Sibieta. 2020. “Differences Between Key Workers.” IFS Briefing Note BN285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1920/BN.IFS.2020.BN0285.

- Ferguson, Susan. 2019. Women and Work: Feminism, Labour and Social Reproduction. London: Pluto Press.

- Folbre, Nancy. 1986. “Hearts and Spades: Paradigms of Household Economics.” World Development 14 (2): 245–255.

- Gaita, Luisiana. 2020. “Decreto Rilancio, i braccianti in sciopero contro i termini della regolarizzazione: ‘Spot per mera utilità di mercato, non è lotta allo sfruttamento’.” Il Fatto Quotidiano, May 21. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2020/05/21/decreto-rilancio-i-braccianti-in-sciopero-contro-i-termini-della-regolarizzazione-spot-per-mera-utilita-di-mercato-non-e-lotta-allo-sfruttamento/5808344/.

- Gershon, Robyn R.M., Lori A. Magda, Kristine A. Qureshi, Halley E.M. Riley, Eileen Scanlon, Maria Torroella Carney, Reginald J. Richards, and Martin F. Sherman. 2010. “Factors Associated with the Ability and Willingness of Essential Workers to Report to Duty During a Pandemic.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 52 (10): 995–1003. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181f43872.

- Gidla, Sujatha. 2020. “We Are Not Essential. We Are Sacrificial.” The New York Times, May 5. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/05/opinion/coronavirus-nyc-subway.html.

- Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. 1992. “From Servitude to Service Work: Historical Continuities in the Racial Division of Paid Reproductive Labor.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 18 (1): 1–43.

- Goitom, Hanibal. 2020. “Malawi: High Court Temporarily Blocks COVID-19 Lockdown.” Accessed June 22, 2020. //www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/malawi-high-court-temporarily-blocks-COVID-19-lockdown/.

- Hanieh, Adam. 2015. “Overcoming Methodological Nationalism: Spatial Perspectives on Migration to the Gulf Arab States.” In Transit States: Labor, Migration and Citizenship in the Gulf, edited by Abdulhadi Khalaf, Omar AlShehabi, and Adam Hanieh, 57–76. London: Pluto Press.

- Hardy, Vincent, and Jostein Hauge. 2019. “Labour Challenges in Ethiopia’s Textile and Leather Industries: no Voice, No Loyalty, No Exit?” African Affairs 118 (473): 712–736.

- The Health Foundation. 2020. “Black and Minority Ethnic Workers Make Up a Disproportionately Large Share of Key Worker Sectors in London.” Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.health.org.uk/chart/black-and-minority-ethnic-workers-make-up-a-disproportionately-large-share-of-key-worker.

- ILO. 2017. “World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal Social Protection to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_604882.pdf.

- ILO. 2018. “Compilation of Decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association.” Accessed May 12, 2020. http://ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:70002:0::NO:70002:P70002_HIER_ELEMENT_ID,P70002_HIER_LEVEL:3945366,1.

- ILO. 2020a. “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work.” 6th ed. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_755910.pdf.

- ILO. 2020b. “Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Loss of Jobs and Hours Among Domestic Workers.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/publication/wcms_747961.pdf.

- ILO. 2020c. “Social Protection Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Developing Countries: Strengthening Resilience by Building Universal Social Protection.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_744612.pdf.

- India Official Guidance. 2020. “No.40-3/2020-DM-I (A) Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs.” https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/PR_Consolidated%20Guideline%20of%20MHA_28032020%20%281%29_1.PDF.

- INE. 2019. Mozambique 2017 Housing and Population Census. Maputo: National Institute of Statistics (INE).

- IOM. 2020. “Mozambican Workers Returning from South Africa Engaged to Check COVID-19’s Spread.” April 21. https://www.iom.int/news/mozambican-workers-returning-south-africa-engaged-check-COVID-19s-spread.

- ISCO. 2008. “International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO08).” ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_172572.pdf.

- ISIC. 2008. “International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities.” Revision 4, Statistical papers, Series M No. 4/Rev.4, UNSD. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_4rev4e.pdf.

- Italy Official Guidance. 2020. “MODULARIO. P. C.M.194. MOD. 247. Il Presidente del Consiglio dei ministri.” http://www.governo.it/sites/new.governo.it/files/Dpcm_img_20200426.pdf.

- Karatepe, Osman M., Alptekin Sokmen, Ugur Yavas, and Emin Babakus. 2010. “Work-family Conflict and Burnout in Frontline Service Jobs: Direct, Mediating and Moderating Effects.” Economics and Management 4: 61–73.

- Katz, Cindi. 2001. “Vagabond Capitalism and the Necessity of Social Reproduction.” Antipode 33 (4): 709–728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00207.

- Kentikelenis, Alexander E., Thomas H. Stubbs, and Lawrence P. King. 2015. “Structural Adjustment and Public Spending on Health: Evidence from IMF Programs in low-Income Countries.” Social Science & Medicine 126: 169–176.

- Knäbe, Timo, and Carlos R. Carrión-Crespo. 2019. “The Scope of Essential Services: Laws, Regulations and Practices.” ILO Working Paper, 63.

- Magadzire, Bvudzai Priscilla, Ashwin Budden, Kim Ward, Roger Jeffery, and David Sanders. 2014. “Frontline Health Workers as Brokers: Provider Perceptions, Experiences and Mitigating Strategies to Improve Access to Essential Medicines in South Africa.” BMC Health Services Research 14 (1): 520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0520-6.

- Maunder, Robert. 2004. “The Experience of the 2003 SARS Outbreak as a Traumatic Stress Among Frontline Healthcare Workers in Toronto: Lessons Learned.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359 (1447): 1117–1125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1483.

- McKellar, Amy, and Andrew Kendrick. 2013. “Key Working and the Quality of Relationships in Secure Accommodation.” Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care 12 (1): 46–57.

- Meagher, Kate. 1995. “Crisis, Informalization and the Urban Informal Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Development and Change 26 (2): 259–284.

- Mezzadri, Alessandra. 2019. “On the Value of Social Reproduction: Informal Labour, the Majority World and the Need for Inclusive Theories and Politics.” Radical Philosophy 2: 33–41.

- Mezzadri, Alessandra. 2020. “A Crisis Like No Other: Social Reproduction and the Regeneration of Capitalist Life During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Developing Economics. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://developingeconomics.org/2020/04/20/a-crisis-like-no-other-social-reproduction-and-the-regeneration-of-capitalist-life-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic/.

- Mezzadri, Alessandra, and Lulu Fan. 2018. “‘Classes of Labour’ at the Margins of Global Commodity Chains in India and China.” Development and Change 49 (4): 1034–1063.

- Mies, Maria. 1982. The Lace Makers of Narsapur: Indian Housewives Produce for the World Market. London: Zed Books.

- Mies, Maria. 1986. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London: Zed Books.

- Monk, Sarah, and Christine Whitehead. 2011. Making Housing More Affordable: The Role of Intermediate Tenures. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Munbodh, Emma. 2020. “Amazon Worker Describes Warehouse as ‘Living Hell’ as Online Orders Soar, Mirror.” Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.mirror.co.uk/money/amazon-worker-says-coronavirus-spreading-21760050.

- Murphy, Maggie F. 2014. “Global Care Chains, Commodity Chains, and the Valuation of Care: A Theoretical Discussion.” American International Journal of Social Science 3 (5): 9.

- NACE. 2006. “NACE rev. 2.” Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5902521/KS-RA-07-015-EN.PDF.

- Nkrumah, Kwame. 1965. Neo-colonialism. The Last Stage of Imperialism. London: Panaf.

- O País. 2020. “Requalificação de mercados ‘empurra’ mulheres para desgraça.” July 14. Accessed July 8, 2020. http://opais.sapo.mz/requalificacao-de-mercados-empurra-mulheres-para-desgraca#.

- Obhan, Ashima, and Bambi Bhalla. 2020. “India: Suspension of Labour Laws Amidst COVID-19.” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.mondaq.com/india/employment-and-workforce-wellbeing/935398/suspension-of-labour-laws-amidst-COVID-19.

- O’Hara, Glen. 2007. “Macroeconomic Planning.” In From Dreams to Disillusionment: Economic and Social Planning in 1960s Britain, edited by G. O’Hara, 37–71. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230625488_3.

- O’Laughlin, Bridget. 1981. “A Questão Agrária em Moçambique.” Estudos Mocambicanos 3: 9–32.

- O’Laughlin, Bridget. 1998. “Missing Men? The Debate over Rural Poverty and Women-Headed Households in Southern Africa.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 25 (2): 1–48.

- O’Laughlin, Bridget. 2016. “Pragmatism, Structural Reform and the Politics of Inequality in Global Public Health.” Development and Change 47 (4): 686–711.

- ONS. 2020a. “Coronavirus and Key Workers in the UK.” Office for National Statistics. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/coronavirusandkeyworkersintheuk/2020-05-15.

- ONS. 2020b. “Key Workers Reference Tables.” Office for National Statistics. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/keyworkersreferencetables.

- Oya, Carlos. 2013. “Rural Wage Employment in Africa: Methodological Issues and Emerging Evidence.” Review of African Political Economy 40 (136): 251–273.

- Oya, Carlos, Christopher Cramer, and John Sender. 2009. “Discrection and Heterogeneity in Mozambican Rural Labour Markets.” In Reflecting on Economic Questions, edited by L. de Brito, C. N. Castel-Branco, S. Chichava, and A. Francisco, 50–71. Maputo: IESE.

- Parreñas, Rhacel S. 2005. “The International Division of Reproductive Labor: Paid Domestic Work and Globalization.” In Critical Globalization Studies, edited by Richard P. Appelbaum and William I. Robinson, 237–248. New York: Routledge.

- Pattenden, Jonathan. 2016. “Working at the Margins of Global Production Networks: Local Labour Control Regimes and Rural-Based Labourers in South India.” Third World Quarterly 37 (10): 1809–1833.

- Phillips, Nicola. 2011. “Informality, Global Production Networks and the Dynamics of ‘Adverse Incorporation’.” Global Networks 11 (3): 380–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00331.x.

- Pinheiro, Luana, Fernanda Lira, Marcela Rezende, and Natália Fontoura. 2019. “OS DESAFIOS DO PASSADO NO TRABALHO DOMÉSTICO DO SÉCULO XXI: REFLEXÕES PARA O CASO BRASILEIRO A PARTIR DOS DADOS DA PNAD CONTÍNUA.” Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 52.

- Power, Marilyn. 2004. “Social Provisioning as a Starting Point for Feminist Economics.” Feminist Economics 10 (3): 3–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000267608.

- Pradella, Lucia. 2014. “New Developmentalism and the Origins of Methodological Nationalism.” Competition & Change 18 (2): 180–193.

- Pradella, Lucia, and Rossana Cillo. 2015. “Immigrant Labour in Europe in Times of Crisis and Austerity: An International Political Economy Analysis.” Competition & Change 19 (2): 145–160.

- Republic of Mozambique. 2020. “Law Number 4/2020. Serie I – Number 82.” Maputo, Republic Bulletin, April 30.

- Rogozanu, Costi, and Daniela Gabor. 2020. “Are Western Europe’s Food Supplies Worth More than East European Workers’ Health?” The Guardian, April 16. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/apr/16/western-europe-food-east-european-workers-coronavirus.

- Sanyal, Kalyan K. 2007. Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism. London: Routledge.

- Sayeh, Antoinette, and Ralph Chami. 2020. “Lifelines in Danger, IMF and Finance & Development.” https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/06/COVID19-pandemic-impact-on-remittance-flows-sayeh.htm.

- Selwyn, Benjamin. 2014. “Capital–Labour and State Dynamics in Export Horticulture in North-East Brazil.” Development and Change 45 (5): 1019–1036.

- Shah, Alpa, and Jens Lerche. 2020. “The Five Truths About the Migrant Workers’ Crisis.” Hindustan Times, July 13. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/the-five-truths-about-the-migrant-workers-crisis-opinion/story-awTQUm2gnJx72UWbdPa5OM.html.

- Simeoni, Crystal. 2020. “Why Nigeria Knows Better How to Fight Corona than the US.” International Politics and Society, March 11.

- South Africa Official Guidance. 2020. “Disaster Management Act, 2002 Regulations Issued in Terms of Section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act, 2002.” https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43258rg11098gon480s.pdf.

- Stevano, Sara, Alessandra Mezzadri, Lorena Lombardozzi, and Hannah Bargawi. Forthcoming. “Hidden Abodes in Plain Sight: The Social Reproduction of Households and Labour in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Feminist Economics.

- Stevano, Sara, and Rosimina Ali. 2019. Working in the Agro-Industry in Mozambique: Can These Jobs Lift Workers Out of Poverty? IDeIAS No 117e. Maputo: IESE.

- Syal, Rajeev. 2020. “Points-based UK Immigration Bill Passes Initial Commons Stage.” The Guardian, Accessed July 24, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/may/18/points-based-uk-immigration-bill-passed-by-parliament.

- Sylla, Ndongo S. 2014. “From a Marginalised to an Emerging Africa? A Critical Analysis.” Review of African Political Economy 41 (sup1): S7–S25.

- Tallontire, Anne, Catherine Dolan, Sally Smith, and Stephanie Barrientos. 2005. “Reaching the Marginalised? Gender Value Chains and Ethical Trade in African Horticulture.” Development in Practice 15 (3-4): 559–571.

- TUC. 2020. “A £10 Minimum Wage Would Benefit Millions of Key Workers.” Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/ps10-minimum-wage-would-benefit-millions-key-workers.

- UK Official Guidance. 2020a. “Critical Workers Who Can Access Schools or Educational Settings.” GOV.UK. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-COVID-19-maintaining-educational-provision/guidance-for-schools-colleges-and-local-authorities-on-maintaining-educational-provision.

- UK Official Guidance. 2020b. “Our Plan to Rebuild: The UK Government’s COVID-19 Recovery Strategy.” GOV.UK. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-COVID-19-recovery-strategy/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-COVID-19-recovery-strategy.

- UNCTAD. 2019. “Commodities and Development Report 2019: Commodity Dependence, Climate Change and the Paris Agreement.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=2499.

- United Nations. 2020a. “The World of Work and COVID-19 Policy Brief.” News. Accessed June 21, 2020. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/genericdocument/wcms_748428.pdf.

- United Nations. 2020b. “UN Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women.” April 9. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/policy-brief-the-impact-of-COVID-19-on-women-en.pdf.

- Valiani, Salimah. 2012. “South-North Nurse Migration and Accumulation by Dispossession in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries.” World Review of Political Economy 3 (3): 354–375.

- Whittle, Rebecca, Marion Walker, Will Medd, and Maggie Mort. 2012. “Flood of Emotions: Emotional Work and Long-Term Disaster Recovery.” Emotion, Space and Society 5 (1): 60–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.002.

- Zamchiya, Phillan, Clemente Ntauazi, and Boaventura Monjane. 2020. “The Four Immediate Impacts of COVID-19 Regulations on the Mozambican Farmers.” PLAAS Blog, April 17. https://www.plaas.org.za/the-four-immediate-impacts-of-COVID-19-regulations-on-the-mozambican-farmers/.