ABSTRACT

This article scrutinises the first four months of the World Bank Group’s Covid-19 response and reveals a persistent prioritisation of private over public interests. The Group’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation, and its financial sector clients, have prevailed in terms of emergency resource allocations. And, while support from the Group’s public sector arms has been portrayed as aiming to strengthen public systems, recipient countries have been urged not to forego structural reforms in support of the private sector. This includes an enhanced focus on public–private partnerships to deliver ostensibly public services. The institution has seized the current crisis as an opportunity to intensify its “Maximising Finance for Development” approach.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine les quatre premiers mois de la réponse du Groupe de la Banque Mondiale à la pandémie de COVID-19 et révèle la constante priorité que celui-ci a accordée aux intérêts publics. La filiale privée du Groupe, la Société Financière Internationale, ainsi que ses clients dans le secteur financier, ont pris le dessus dans l’allocation de ressources d’urgence. Et, tandis que le soutien apporté par les branche du secteur public du Groupe a été décrit comme ayant pour but de renforcer les systèmes publics, les pays receveurs ont été exhortés à ne pas abandonner leurs réformes structurelles en faveur du secteur privé. Cela inclut une attention particulière portée sur les partenariats public-privé qui visent à offrir des services ostensiblement publics. La crise en cours a de ce fait présenté à cette institution l’opportunité d’intensifier son approche visant à «Maximiser les financements pour le développement».

Introduction

In recent years most discussions on development finance have focused on using public money and institutions to leverage private finance. The World Bank Group (WBG) has been a lead player in this field and its “Maximising Finance for Development” (MFD) approach is perhaps the most widely known illustration of this drive. The WBG’s MFD approach has structured the Bank’s operations since 2017 and its implementation is an indication of the institution’s commitment to increase the involvement of the private sector in development. An important objective is to attract trillions of dollars managed by private institutional investors to help finance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The agenda argues that “better and smarter Official Development Assistance (ODA) can help catalyse and leverage financing from diverse sources towards the SDGs” (World Bank and IMF Citation2015, 7). Various instruments have been rolled out to operationalise the blending of public and private finance (blended finance, BF) approach at the heart of this new agenda. These include guarantees, subsidies, first-loss equity positions and public–private partnerships (PPPs) (see Van Waeyenberge Citation2015; Bayliss et al. Citation2020).

The use of ODA (or donor funds) to mobilise private finance is not new in the operations of the WBG’s private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which has had a BF portfolio since the late 1990s. However, in 2017, this became central to its corporate strategy (IFC 3.0) and, that same year, the WBG launched the IDA Private Sector Window (PSW), which constituted a significant scaling up of its efforts to mobilise aid resources in support of private investment in low income countries (LICs) and fragile states (FCS). Subsequently, the capital increase approved by WBG’s shareholders in 2018 came with ambitious targets to move this agenda forward (WBG Citation2018), despite multiple critiques of the central tenets of the approach (Gabor Citation2020; Bayliss, Romero, and Van Waeyenberge, Citationforthcoming; Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge, Citationforthcoming; ITUC Citation2020).

At the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the WBG was called upon to respond in a speedy way. In March 2020, it announced a $14 billion package of fast-track Covid-19 financing (FTCF) to support countries and companies in their efforts to manage the negative impacts of the pandemic. Moreover, as the crisis projected a major global recession, the Bank announced a further $160 billion in commitments over the next 15 months.

This article analyses the response of the WBG to the Covid-19 pandemic, with a particular interest in the reconfiguration of the public–private nexus promoted through the crisis. It does so by presenting first, in the second section, the WBG’s MFD approach to development finance as its pre-existing strategy. The article then proceeds, in the third section, with a brief account of the WBG’s response to Covid-19, which is followed, in the fourth section, by its critical analysis. This reveals a persistent prioritisation of private over public interests by the WBG both in the immediate pandemic response and beyond, as the pandemic offers the institution an opportunity to accelerate its MFD approach. Furthermore, the WBG’s commitment to the promotion of private finance is likely to be compounded by the limited fiscal space that developing countries will face in the post-Covid-19 context. The final section concludes.

“Maximising finance for development” at the World Bank

Over the last decade, the WBG has been a lead player in reorienting development cooperation so that it becomes focused on using public money and institutions to leverage private finance (see Gabor Citation2020). This was evidenced in the run up to the Third United Nations Conference on Financing for Development, resulting in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA), which squarely put the private sector at the heart of the UN strategy to finance the SDGs. The WBG explicitly argued for development finance in the post-2015 era to become centrally organised around the “blending” or “leveraging” of private finance by public resources (see Van Waeyenberge Citation2015). A key document, “From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance Post-2015 Financing for Development”, advocated for a “paradigmatic shift” building on the proposition that “the world needs intelligent development finance that goes well beyond filling financing gaps and that can be used strategically to unlock, leverage and catalyze private flows and domestic resources” (World Bank and IMF Citation2015, 3).

The core idea of this approach is to mobilise ODA to de-risk private flows. Public sector measures are seen as necessary to encourage private investment in that they should seek to decrease perceived risk or increase anticipated returns (World Bank and IMF Citation2015, paragraph 35). These measures can take various forms, from offering technical advice on how to reform policies and institutions in a particular country and/or sector, to taking first equity loss positions or providing loans to private sector agents at subsidised rates (see Van Waeyenberge Citation2015; Bayliss et al. Citation2020; Bayliss, Romero, and Van Waeyenberge, Citationforthcoming; Gabor Citation2020). Reflecting an unwillingness of the donor community to scale up and strengthen public financing of development sufficiently or to create a global body through which tax issues could be resolved to tackle massive illegal capital flight strongly detrimental to countries in the Global South, progress on the SDGs then requires limited ODA to act as a catalyst for increased private investment.

The WBG’s MFD approach, launched formally in 2017, is a good illustration of this drive. The MFD, set out as the vision for the WBG in 2030 (World Bank and IMF Citation2017a), sees private finance as a first option for sustainable investment. If this cannot be accessed, governments and donors need to consider if upstream interventions “to address market failures” can lead to a flow of private finance. These measures include reviewing country and sector policies, regulation, pricing, institutions and capacity. Failing this, the next option is to consider the potential for various BF instruments like guarantees, other risks-sharing instruments and PPPs, to attract private investors. Only as a last resort should policy makers look at using public finance. This approach, initially focused on infrastructure, is expected to be expanded to finance, education, health and agribusiness. To implement this strategy, an initial set of nine pilot countries were identified, including two FCSs (World Bank and IMF Citation2017b).Footnote1

The MFD approach is therefore part and parcel of a broader institutional effort to create markets and crowd-in private finance. In particular, the MFD complements the IFC 3.0 corporate strategy, whose “success … requires the active involvement and collaboration of the Bank in creating enabling policy and regulatory environments and on de-risking the private sector’s entry into these environments” (World Bank and IMF Citation2017a, 20). Interestingly, the MFD came with a call from then-World Bank president Jim Kim for a capital increase for the institution. As Kim put it when addressing WBG shareholders:

to deliver what countries need at the scale you expect of us – we need more resources … We can play a critical role in finding win-win solutions, where we maximize financing for development, and create opportunities for the owners of capital to make higher returns. (Kim Citation2017a)

The WBG’s strategic use of BF took on a specific form when during the 2017–2020 replenishment of its concessional arm (the International Development Association, IDA18Footnote2), donors agreed to create a $2.5 billion IDA IFC-MIGA Private Sector Window (PSW) (World Bank Citation2017). The PSW places donor aid (IDA) resources under the direct control of the IFC ($2bn) and MIGA ($0.5bn) to support their attempt to mobilise private investments in low income and fragile country contexts. For the World Bank, the PSW serves as an “illustration of how the World Bank Group is putting the Finance for Development (FfD) agenda into action” (World Bank and IMF Citation2017a, 3).

The PSW “provides an opportunity for IDA to make strategic use of public resources to catalyze private investments in these challenging markets, by leveraging IFC’s and MIGA’s business models and client relationships” (World Bank Citation2017, iii). Its creation was seen as complementing the World Bank’s more traditional work via its public sector concessional arm (IDA), which itself seeks to promote policy reforms to improve “business environments”, by now allowing to de-risk private investments more directly (i). What this means in practice, is that aid resources are used to attract and subsidise private sector investments to operationalise a strategy that sees the private sector as key to improved development outcomes in low income and fragile country settings (see IFC Citation2017; World Bank and IMF Citation2017a). It should also be noted that while, previously, the IFC delivered hundreds of millions of its profits in support of IDA lending, it is now a net recipient of IDA funding. At the same time, a smaller share of its investments reaches IDA countries (Kenny Citation2020).

For the IFC, the IDA PSW represented a significant step up and opportunity in crafting a key role for itself in the BF landscape. Where it had previously managed smaller pilot BF schemes, mainly with an emphasis on climate finance (IFC Citation2018a; BWP Citation2013), it was now endowed with a substantial amount of donor resources to mobilise in support of its new strategy. The PSW became a “critical component” of the IFC 3.0 strategy “to tackle private sector challenges by creating markets and mobilisation” (World Bank Citation2017, i).Footnote3 This combined with the idea that the de-risking mechanisms would assist in “unlocking” new sources of funds from institutional investors (IFC Citation2017, 12).Footnote4

Despite being celebrated as emblematic of the WBG’s MFD and instrumental to deliver the IFC 3.0 strategy, the IDA PSW did not proceed to fulfil expectations.Footnote5 First, by the end of 2019 (just six months before the $2.5bn IDA PSW should have been fully allocated), the PSW had committed just over $0.5 billion – only slightly more than a fifth of the resources available to it. Second, strong concerns were raised regarding the lack of transparency on the way in which aid (IDA) subsidies were finding their way to private firms via the PSW. US Congresswoman, Maxine Waters, Chair of the US House Committee on Financial Services, led the charge. She insisted that “IDA, through its new PSW … is subsidizing private firms selected without competition on the basis of unsolicited proposals. The PSW is likely to prioritize financial returns over positive development impacts, which will be difficult to monitor”. She added that the PSW “stands in conflict with the World Bank’s own principles that call for subsidies to be justified, transparent, competitively based, focused on impact, and guarded against rent-seeking opportunities” (Waters Citation2019).Footnote6 This was followed by the threat to withhold Congressional support for the IFC’s capital increase that had been agreed in 2018, unless “these transfers stop, or at a minimum are competitively based and fully transparent down to the amounts and purpose of aid going to which firms and projects” (Waters Citation2019; see also Igoe Citation2019).

These objections reflected more general concerns regarding BF ranging from: limited private sector mobilisation, inadequate risk sharing, lack of additionality, lopsided leverage ratios, ambiguous, if any, development impact, lack of transparency and accountability, high cost of investments, the creation of new liabilities, limited domestic ownership, and various types of conflicting interests, not to mention the little appetite of private investors for low income and fragile country settings and hence the low share of BF going there (see Bayliss et al. Citation2020 for a review). Still, at the IDA19 replenishment donors agreed to renew the PSW for the next three years. However, at the same time, the PSW’s resource envelope was held constant (at $2.5 billion), reflecting donor unwillingness to scale up the approach (Edwards Citation2019; IDA19 Citation2020).

The WBG Covid-19 response

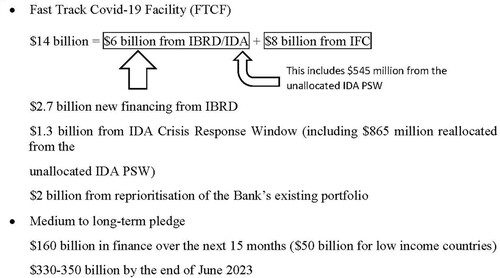

As Covid-19 started to wreak havoc in early 2020, the WBG understood that it had to rise to the occasion and seek to mitigate both the immediate health emergency as well as the longer-term fallout from the major disruption to economic and social life. In March 2020, its Directors approved a $14 billion Fast Track Covid-19 Facility (FTCF) for an emergency response to the virus (see ). This constituted “the largest and fastest crisis response in the Bank Group’s history” (WBG Citation2020a). It entailed the approval of “specific waivers and exceptions required to enable the rapid preparation and implementation of country operations processed under the Facility” (WBG Citation2020b, 6). Moreover, as the crisis projected a major global recession, the Bank committed to provide $160 billion in finance over the next 15 months, with $50 billion for low income countries, and $330–350 billion by the end of June 2023.

Figure 1. WBG's response to Covid-19.

Source: WBG (Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

A closer look at how the FTCF resources were distributed inside the WBG reveals a preference for private sector activities. While $6 billion (approved as part of the FTCF) was to be disbursed through the public sector arms of the World Bank (the IBRD and IDA) to strengthen national systems, including of health, education and social protection, the larger share of this package ($8 billion) was to be channelled through the WBG’s private sector arm, the IFC. According to the WBG, “with this financing, the IFC will provide direct lending to existing clients affected by the outbreak, as well as support financial institution partner clients so they can continue lending to businesses” (IFC Citation2020a). It was the WBG’s assessment that “[t]he developing world needs private sector investment now more than ever” (IFC Citation2020b). This chimed strongly with the IFC’s strategic goal of promoting private investment, including by mobilising aid resources via the IDA PSW (World Bank and IMF Citation2020). The IFC also announced a massive expansion of its upstream work, including by hiring 200 new staff to identify and create bankable projects in developing countries (IFC Citation2020c).

In addition, in April 2020 the WBG’s shareholders and the G20 Finance Ministers endorsed the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). They agreed to the suspension of bilateral official debt services to G20 countries of 73 eligible LICs and called on private creditors to participate in the initiative. However, the WBG limited its action to “call on official bilateral creditors to grant debt relief” to the world’s poorest countries (WBG Citation2020c). As for relief on debts owed to the World Bank, its President expressed the reluctance of the institution, arguing that this would risk its AAA credit rating. Instead, he called for more donor contributions to facilitate action (Malpass Citation2020a) – a position that drew strong criticism from civil society advocates.Footnote7

Between March and end of June (the end of the WBG’s 2020 fiscal year), the public sector arms of the WBG (IBRD/IDA) approved Covid-19 related operations in 108 countries, including 33 FCSs (WBG Citation2020c; Duggan and Sandefur Citation2020). New commitments totalling $3.8 billion financed governments’ purchases of health equipment, personal protective equipment and training, while an additional $2.5 billion was redirected towards the Covid-19 response from an existing portfolio of operations under implementation. The latter reallocation raised concerns of possible future funding inadequacies in the absence of adequate funding commitments for the recovery period (see Oxfam Citation2020a).

Meanwhile, the IFC, which received the larger share of the WBG FTCF (see ), organised its Covid-19 response along four facilities: Working Capital Solutions, Global Trade Finance, Real Sector Crisis Response and Global Trade Liquidity. With the exception of the Real Sector Envelope, these facilities are dedicated to supporting financial intermediaries, and, by the end of June 2020, commitments amounted to $3.5 billion (WBG Citation2020c). Publicly available information indicates that during the period between beginning of April and end of June 2020,Footnote8 38 individual projects were approved, some of which benefiting from aid support via the IDA PSW. Indeed, the IDA PSW dramatically accelerated commitments as part of the Covid-19 IFC response: the PSW saw an envelope of commitments (just over $0.5 billionFootnote9) between April and end of June equivalent in size to all its commitments in the preceding two and a half years. The IFC was explicit that

to ensure that it continues to support private sector development in low income and fragile and conflict-affected countries, strong emphasis will be placed on supporting clients operating in these countries. In addition, the IFC will leverage concessional financing from the IDA PSW … particularly to attract foreign direct investment into more challenging low income and fragile countries. (IFC Citation2020a)

In sickness or in health: MFD forever

The first four months (March to end of June 2020) of the WBG’s response to the pandemic raise a set of issues. Close scrutiny reveals how the pandemic provides an opportunity for the institution to enhance and accelerate its broader MFD agenda.

First, the WBG Covid-19 response favours private over public sector clients and there are tensions in how this aligns with the institution’s twin goals of ending extreme poverty and promoting shared prosperity. This is despite shareholders’ explicit demands at the 2020 Spring Meetings for the WBG to

help governments deploy resources toward public health interventions, nutrition, education, essential services, and social protection against the immediate adverse effects of the shocks. We also support the WBG’s emphasis on boosting government preparedness to protect human capital against potential subsequent waves of the outbreak and future pandemics. (WBG Citation2020b; emphasis added)

to directly support the private sector’s ability and capacity to deliver healthcare products and services and to respond to the immediate and longer-term challenges to developing countries’ already vulnerable health systems affected by C19, thereby increasing the resilience and impact of developing countries’ healthcare systems. (WBG Citation2020d, 26)Footnote10

Second, the share allocated in the FTCF to the institution’s private sector arm (at just short of 60 per cent) is out of the line with the WBG’s traditional trends in terms of relative weight of commitments to public versus private clients. Over the last five years, its private sector operations via the IFC accounted for around 17 per cent in total commitments as compared to the combined share of commitments via its public sector operations (IBRD/IDA) of around 70 per cent (World Bank Citation2019, 7).

Third, the WBG’s Covid-19 response reveals conflicting demands on the aid resources that had sat idle in the IDA PSW by the time the pandemic unfolded (see above). These amounted to around $1.4 billion at the start of the pandemic, of which $865 million were reallocated away from the PSW to IDA’s Crisis Response Window to support IDA’s health Covid-19 pandemic response (IDA18 Citation2020a). This, however, raises the question as to why not all remaining resources of the PSW were reallocated to the Bank’s aid response to governments (via IDA). This would have further bolstered governments’ capacities to respond to the health emergency and its social and economic fallout rather than benefit banks and private companies.

This brings us, fourth, to questions regarding the types of clients that benefit from the IFC Covid-19 response. About 68 per cent of IFC Covid-19 projects, in value terms (at the end of June 2020), have targeted financial institutions. These are predominantly banks – with one beneficiary being the largest Mongolian microfinance institution and another a giant SME-oriented group of commercial banks with headquarters in Germany. The rest of IFC’s commitments has benefited non-financial companies in the following sectors: private healthcare; agribusiness/food processing; and other, including tourism (for instance, Shangri-La Asia a leading owner and operator of hotels and resorts in Asia). All the beneficiaries are existing IFC clients and are privately owned (with the exception of an Indian company). Around 50 per cent of these are either majority-owned by multinational companies or are themselves international conglomerates. The rest are majority locally owned, usually big companies, many of which are listed in domestic stock exchanges. The IFC holds equity positions in some of the FTCF-targeted companies, which also seems to indicate that the IFC per se is benefiting from these schemes.

Examples of IFC Covid-19 projects include: a $8.35 million concessionary loan (via the IDA PSW) to a French-South African multi-national joint venture (Cerba Lancet Africa), owning a network of private clinical diagnostic laboratories across Sub-Saharan Africa, to support its expansion on the continent including through the acquisition of existing labs; a $4 million loan (with IDA PSW support) to the activities of the healthcare subsidiary (Ciel Healthcare) of a Mauritian conglomerate, which has operations in Mauritius, Uganda and Nigeria; a $9 million loan (also with the possibility of drawing on concessional finance) to the largest private Technical and Vocational Education provider in Jordan (Luminus) – and previously IFC poster child “combining purpose with profit” (IFC Citation2018b); an unsecured senior loan (up to $100 million) to a leading Nigerian bank (Zenith), the board of which was considering to distribute an interim dividend for shareholders at the same time as receiving financial assistance from the IFC; and a senior loan ($50 million) to Garanti BBVA – Turkey’s second largest bank, which is majority owned by BBVA Spain, one of the biggest global banks in the world. While this is only a small sample of IFC Covid-19 projects, these transactions draw attention to the type of clients and activities that are benefiting from IFC (and IDA) resources under the fast track Covid-19 response.Footnote11

Specifically, the emphasis on the financial sector seems to rely on the assumption that it is important to protect the financial system as a way to reach small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This is despite challenges that this strategy brings with regard to reaching the poor, particularly given the high degree of informal sector work in many developing countries.Footnote12 Further, as our analysis indicates, around 50 per cent of IFC Covid-19 support beneficiaries are either majority owned by international groups or are themselves international conglomerates. This chimes with findings by Dreher, Lang, and Richert (Citation2019) that IFC lending tends to favour companies from major IFC shareholders and raises questions regarding the alleged additionality of IFC resources. Also, while the IFC has committed to deliver 40 per cent of its annual commitments in IDA countries and FCS, these commitments have remained low over the last five years (Kenny, Ramachandran, and Masood Citation2020). At the same time, there is little evidence that these investments benefit the poorest and most vulnerable. A 2019 evaluation report states that “creating markets in a manner that allows the poor to participate in markets or benefit from such efforts has remained a challenge … Evidence of the direct welfare implication of market creation efforts for the poor is lacking” (IEG Citation2019, 14–15).

Fifth, in return for US Congress support for the IFC capital increase and in response to ongoing criticism regarding the lack of transparency and accountability of IFC operations, the WBG President agreed to a set of reform commitments. These include greater transparency with regard to the IFC’s financial intermediary portfolio and IDA subsidies the IFC gives to private firms to ensure that more subsidies are awarded on a competitive basis, among others (Malpass Citation2020b). Yet, the FTCF grants specific waivers and exceptions to enable rapid preparation and implementation of country operations processed under this facility (WBG Citation2020b, 6) which sits uneasily with these commitments (see also Oxfam Citation2020b). With increased pressure to “get money out the door”, there has also been very limited (if any) stakeholder engagement as projects are rolled out (see Bank Information Center Citation2020).

Sixth, although support from the Bank’s public sector arms (IBRD/IDA) has been portrayed as aiming to strengthen public health systems, recipient countries are, at the same time, urged not to forego “structural reforms” focused on liberalisation and deregulation. Indeed, while most of the IBRD/IDA loans approved in this period are aimed at addressing the health crisis, others have a broader scope and include more traditional reforms in support of the private sector. These include: safeguarding the implementation of reforms that enhance (foreign) private sector participation in the Ethiopian economy (in energy, logistics and telecommunications in particular); a loan to “crowd in private investment and enhance the public sector’s capacity to deliver on the government’s inclusive growth agenda” in Kenya; a loan to foster private participation in gas infrastructure and telecommunications in Senegal; a loan for reforms “that are expected to support economic diversification by enhancing openness and attracting more investments into key sectors, relaxing trade barriers, reforming SOEs and increasing infrastructure investment” in Indonesia, etc.Footnote13 This indicates a strong and continuing commitment by the WBG to a market-driven approach which, among other things, has resulted in adverse health outcomes (Kentikelenis Citation2017; Kentikelenis et al. Citation2020).

Finally, moving forward, the WBG aims to capitalise on its One WBG strategy which was launched in 2013 to strengthen synergies across its different affiliates in support of scaling up private sector solutions.Footnote14 As highlighted in a WBG Covid-19 Crisis Response Approach Paper projecting the WBG’s “longer duration approach” to the crisis response: “Working as One WBG, the approach emphasizes selectivity and public-private joint interventions to scale up private sector solutions while staying focused on results” (WBG Citation2020d, vi). While the WBG touts an explicit commitment to “achieving resilient, inclusive and sustainable recovery in a world transformed by the coronavirus” (27), its approach is strongly characterised by a persistent (and reinvigorated) celebration of private over public sector solutions to development challenges. The prejudice against the public sector remains staggering, despite a dearth of analytical or empirical evidence to underpin such a strong bias. The inclusion of “stronger public involvement in the economy” in its summary of possible long-lasting negative consequences of the pandemic is emblematic (28). This combines with an emphasis on private sector solutions in its approach to “rebuilding better”. The WBG insists that the fiscal headroom and debt capacity of developing countries are likely to be constrained post crisis which becomes its renewed rationale for further promoting private sector solutions (31).

The WBG is explicit about its strategy:

It will be important to crowd-in private participation in delivery of certain public services and infrastructure (including digital access). Governments can devise public-private schemes that leverage public and private resources and capabilities … Governments can establish dedicated PPP units, as well as develop PPP legal frameworks, guidelines, operating procedures and tools … Levelling the playing field and enabling greater competition in local markets, especially in sectors that tend to be dominated by SOEs, could improve service delivery, lower costs and increase domestic revenue mobilisation through privatisation, dividend distribution, royalties and concession fees, as well as general corporate taxes. (WBG Citation2020d, 31)

For the WBG, then, a pandemic should clearly not go to waste in offering opportunities to supercharge its agenda of Maximising (private) Finance for Development. This includes a relentless focus on PPPs (through advisory services, policy guidelines and finance),Footnote15 as a way to finance public service provision, which proceeds despite weak evidence in their support and a fast-growing literature denouncing their multiple risks (Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge Citation2018). WBG support for PPP-related projects has indeed proceeded apace during the Covid-19 crisis (Fakhoury Citation2020). The IFC has advised road PPP projects in Brazil, a PPP project in renewable energy in India and a healthcare PPP project in Vietnam. The WB has supported governments to advance reforms aimed at de-risking private investment and advancing the PPP agenda in Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda.Footnote16 Moving forward, it hopes to accelerate government actions that facilitate its MFD agenda, including “to mutualize risks, reform underperforming sectors, level the playing field with subsidy removals, open up competition, and provide guarantees and other forms of risk mitigation and credit enhancement” (WBG Citation2020d, 38).

This persistent commitment to private finance at the heart of development proceeds without any clear analytical or empirical rationale (see Van Waeyenberge Citation2015) and raises a host of issues that have been highlighted by various contributions to the literature (see Bayliss Citation2006; Bayliss and Fine Citation2008; BWP Citation2020; Kentikelenis et al. Citation2020). These range across: fiscal liabilities (as risks remain with the public sector), fragmentation of public service provision, cherry-picking by private investors, lack of context-specific design of public service provision, worsening employment conditions in privately financed public sectors, higher costs of (and inequitable access to) public services, redistributions from households in developing countries to shareholders of privately financed public services (against the backdrop of historic inequality levels), or lack of flexibility due to long-term contractual terms (see for instance Romero Citation2015; Jomo et al. Citation2016; Bayliss and Van Waeyenberge, Citationforthcoming).

Conclusion

The WBG’s pandemic response highlights the centrality of the private sector in three distinct ways. First, the IFC and its private clients have prevailed in terms of resource allocation, design and implementation of Covid-19-related projects. This includes a renewed support for IFC’s use of blended finance. Second, and despite the support from the Bank’s public arms (IDA/IBRD) been portrayed as aiming to strengthen public health systems, recipient countries have been urged to not forego structural reforms aimed at strengthening of markets through liberalisation, deregulation and so on. Third, and moving forward, the WBG continues with the MFD approach by placing PPPs, and the private sector more broadly, at the epicentre of the recovery.

The Covid-19 pandemic has then provided the WBG with an opportunity to enhance its MFD approach. The centrality of the private sector in development in general, and public service provisioning in particular, is being strengthened both in discourse and practices – despite little, if any, scholarly arguments in support of such an approach. This will be compounded by the limited fiscal space that developing countries are likely face in the post-Covid-19 (see also Gabor Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ourania Dimakou

Ourania Dimakou is a Lecturer in Economics, SOAS University of London. Her research interests include the theoretical and historical evolution of macroeconomic theories, as well as the role and policies of international financial institutions. She recently co-authored Macroeconomics. A Critical Companion with Ben Fine (London: Pluto). She recently also joined Universidad de Rey Juan Carlos in Madrid.

Maria Jose Romero

Maria Jose Romero is a PhD candidate in Development Economics at SOAS University of London. Her research project is on the global promotion of public private partnerships (PPPs) in health and education. Since 2012 she has worked for the European Network on Development (Eurodad), a Brussels-based non-governmental organisation, as a Policy and Advocacy Manager on publicly backed private finance and development finance institutions. This includes extensive work on international financial institutions, PPPs and blended finance at the European and global level.

Elisa Van Waeyenberge

Elisa Van Waeyenberge is a Senior Lecturer and currently acting as (co-)Head of the Department of Economics, SOAS University of London. She has a long-standing interest in the International Financial Institutions and the way in which these affect the policy space of countries in the Global South. She has authored numerous publications on this topic including a (co-)edited book entitled The Political Economy of Development. The World Bank, Neoliberalism and Development Research (London: Pluto).

Notes

1 The pilot countries are Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Nepal, and Vietnam.

2 IDA is replenished every three years by donor resources. IDA18 is the eighteenth replenishment since the creation of IDA in 1960.

3 As part of its role as a global player, the IFC came to lead the DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects, which in October 2017 produced enhanced principles for the use of concessional finance in private sector operations (DFI Working Group Citation2017).

4 For then-World Bank president, Kim (Citation2017b): “One of the things we’d like to do, for example, is to find a way for a pension fund in the United Kingdom to be able to invest in building roads in Dar es Salaam, get a reasonable return on that investment, and do a lot of good in the process”.

5 The premature departure of the CEO of the IFC, Philippe Le Houérou, announced on 7 July 2020, perhaps reflects some of his disenchantment with the slow progress on the broader BF agenda at the IFC.

6 See also concerns regarding transparency around PSW subsidies to private sector firms raised by other donors at the discussions on the IDA19 replenishment (IDA19 Citation2019, 2). And also note that the IFC has formalised its support for unsolicited proposals with a US$1.4 billion advisory services project (project number 603405), approved in October 2019, which seeks to “serve as a support mechanism for the development of transport related projects in developing countries through Unsolicited Proposals, that is, those conceptualised by the private sector instead of the traditional public ones” (https://disclosures.ifc.org/#/projectDetail/AS/603405).

7 See for example, https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/world-bank-remains-outlier-debt-relief-oxfam

8 According to publicly available information on the IFC and IDA18 PSW webpages, as of 10 August 2020, only around $2.6 billion worth of projects between April and end of June can be identified. Projects under the Global Trade Finance Program will be disclosed with a year-long lag, according to the IFC.

9 This is $545 million from IDA18, plus another $150 million from IDA19 for the three IDA PSW global projects set up by the IFC and mirroring the 3 main IFC fast-track facilities. It is from these global IDA PSW funds that the individual FTFC projects to IDA eligible countries may draw support from.

10 The IFC will contribute $2bn from its own account and aims to mobilise $2 bn from private sector partners, see https://ifcextapps.ifc.org/IFCExt/Pressroom/IFCPressRoom.nsf/0/70763342FB27B761852585B40058C13A

11 These and all publicly available projects of the IFC/ IDA18 PSW can be found here: IFC (Citation2020f) and IDA18 (Citation2020b).

12 According to ILO (Citation2020), “the informal economy comprises more than half of the global labour force and more than 90% of Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) worldwide.”

13 The project details can be found under the program information documents: (i) for Ethiopia, IBRD/IDA (Citation2020a, 4); (ii) for Kenya, IBRD/IDA (Citation2020b, 6); (iii) for Senegal, IBRD/IDA (Citation2020c, 14); (iv) for Indonesia, IBRD/IDA (Citation2020d, 24).

14 Since the 2013 WBG Strategy there have been continuous references to “Working as One World Bank Group”, which “means scaling up collaboration” across WBG institutions. The WBG consists of five distinct organisations: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which finances low- and middle-income countries, and the International Development Association (IDA), which provides concessional loans and grants to low-income countries, together they make up the World Bank (WB); the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which supports private sector companies, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which provides political risk insurance, and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which provides international facilities for conciliation and arbitration of investment disputes.

15 See, for instance, “public private partnerships will have to play an even greater role given the likelihood of higher public debt and debt vulnerabilities in most developing countries” (WB Citation2020d, 14).

16 Details about individual projects can be found here: for Brazil, Cabello, de Almeida, and Alves (Citation2020), India IFC (Citation2020d), Vietnam IFC (Citation2020e), Nigeria IBRD/IDA (Citation2020e), Kenya IBRD/IDA (Citation2020b) and Uganda IBRD/IDA (Citation2020f).

References

- Bank Information Center. 2020. “Liberia COVID-19 Emergency Response Project.” https://bankinformationcenter.org/en-us/project/how-can-the-world-bank-promote-the-inclusion-of-marginalized/.

- Bayliss, Kate. 2006. “Privatization Theory and Practice: A Critical Analysis of Policy Evolution in the Development Context.” In The New Development Economics: After the Washington Consensus, edited by Ben Fine and K. S. Jomo, 144–161. New Delhi: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bayliss, Kate, Bruno Bonizzi, Ourania Dimakou, Christina Laskaridis, Farwa Sial, and Elisa Van Waeyenberge. 2020. “The Use of Development Funds for De-risking Private Investment: How Effective is It in Delivering Development?” DEVE Committee, European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EXPO_STU%282020%29603486.

- Bayliss, Kate, and Ben Fine, eds. 2008. Privatization and Alternative Public Sector Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa - Delivering on Electricity and Water. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bayliss, Kate, Maria Jose Romero, and Elisa Van Waeyenberge. Forthcoming. “The Private Sector and Development Finance: in Whose Interests?” Development in Practice.

- Bayliss, Kate, and Elisa Van Waeyenberge. 2018. “Unpacking the Public Private Partnership Revival.” The Journal of Development Studies 54 (4): 577–593.

- Bayliss, Kate, and Elisa Van Waeyenberge. Forthcoming. “Public Private Partnerships and the Financialisation of Infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa.” In Financialisations of Development: Global Games and Local Experiments, edited by Eva Chiapello, Anita Engels, and Eduardo Gresse. Abingdon: Routledge.

- BWP. 2013. “IFC Blended Finance.” Bretton Woods Project, June 26. https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2013/06/art-572886/.

- BWP. 2020. “The IMF and World Bank-led Covid-19 Recovery: Building Back Better or Locking in Broken Policies?” Bretton Woods Project, July 16. https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2020/07/the-imf-and-world-bank-led-covid-19-recovery-building-back-better-or-locking-in-broken-policies/.

- Cabello, Richard, Bernardo Tavares de Almeida, and Rafael Maia Alves. 2020. “Scaling Private Sector Participation to Build Better Roads in Brazil.” World Bank Blogs, June 11. https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/scaling-private-sector-participation-build-better-roads-brazil.

- DFI Working Group. 2017. “DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects.” Summary Report, October. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/a8398ed6-55d0-4cc4-95aa-bcbabe39f79f/DFI+Blended+Concessional+Finance+for+Private+Sector+Operations_Summary+R....pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=lYCLe0B.

- Dreher, Axel, Valentin F. Lang, and Katharina Richert. 2019. “The Political Economy of International Finance Corporation Lending.” Journal of Development Economics 140: 242–254.

- Duggan, Julian, and Justin Sandefur. 2020. “Tracking the World Bank’s Response to Covid-19.” Centre for Global Development, April 14. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/tracking-world-banks-response-covid-19.

- Edwards, Sophie. 2019. “World Bank Hits IDA Replenishment Target Despite Smaller US Pledge.” Devex, December 19. https://www.devex.com/news/world-bank-hits-ida-replenishment-target-despite-smaller-us-pledge-96226.

- Fakhoury, Imad N. 2020. “How the World Bank is Looking at COVID-19 and Public-Private Partnerships, Right Now and Post-Crisis.” World Bank blogs, June 10. https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/how-world-bank-looking-covid-19-and-public-private-partnerships-right-now-and-post-crisis.

- Gabor, Daniela. 2020. “The Wall Street Consensus.” SocArXiv, July 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wab8m.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020a. “COVID-19 Supplemental Financing to the Second Ethiopia Growth and Competitiveness Programmatic Development Policy Financing (P169080).” The World Bank, May 25. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/448211590413206849/pdf/Appraisal-Program-Information-Document-PID-COVID-19-Supplemental-Financing-to-the-Second-Ethiopia-Growth-and-Competitiveness-Programmatic-Development-Policy-Financing-P169080.pdf.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020b. “Kenya Inclusive Growth and Fiscal Management DPO 2 (P172321).” The World Bank, December 23. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/409451577716708648/pdf/Concept-Program-Information-Document-PID-Kenya-Inclusive-Growth-and-Fiscal-Management-DPO-2-P172321.pdf.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020c. “Senegal Third Multi-Sectoral Structural Reforms Development Policy Financing: Supplemental Financing (P173918).” The World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P173918.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020d. “Indonesia First Financial Sector Reform Development Policy Financing: COVID-19 Supplemental Financing (P174025).” The World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P174025.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020e. “Nigeria Energy and Extractives Global Practice (P164001).” The World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P164001.

- IBRD/IDA. 2020f. “Strengthening Capacities and Institutions for PIM, PPPs and DRM in Uganda (P169908).” The World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P169908.

- IDA18. 2020a. “Update on IDA Contribution to COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Development Finance Corporate IDA and IBRD.” International Development Association. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/673321588557820754/pdf/Update-on-IDA-Contribution-to-COVID-19-Pandemic-Response.pdf.

- IDA18. 2020b. “Private Sector Window Projects.” Accessed 10 August 2020. https://ida.worldbank.org/financing/ida18-private-sector-window/private-sector-window-projects.

- IDA19. 2019. “IDA19 Second Replenishment Meeting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June 18–20, 2019.” Co-Chairs’ Summary, International Development Association. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/418181566241256305/pdf/IDA19-Second-Replenishment-Meeting-Addis-Ababa-Ethiopia-June-18-20-2019-Co-Chairs-Summary.pdf.

- IDA19. 2020. “IDA19: Ten Years to 2030: Growth, People, Resilience.” International Development Association, Additions to IDA Resources: Nineteenth Replenishment. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/459531582153485508/pdf/Additions-to-IDA-Resources-Nineteenth-Replenishment-Ten-Years-to-2030-Growth-People-Resilience.pdf.

- IEG. 2019. “Creating Markets” to Leverage the Private Sector for Sustainable Development and Growth An Evaluation of the World Bank Group’s Experience Through 16 Case Studies. Washington: Independent Evaluation Group. https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/sites/default/files/Data/Evaluation/files/CreatingMarkets.pdf.

- IFC. 2017. Creating Markets and Mobilizing Private Capital. Strategy and Business Outlook FY18 –FY20. International Finance Corporation.

- IFC. 2018a. Blended Finance a Stepping Stone to Creating Markets. International Finance Corporation. Emerging Market Compass. Note 51.

- IFC. 2018b. Educating Students for Jobs, Stability, and Growth. Luminus: Transforming Vocational Education in Jordan. International Finance Corporation.

- IFC. 2019. Strategy and Business Outlook Update FY20 – FY22. Gearing up to Deliver IFC 3.0 at Scale. International Finance Corporation. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/78684d22-f9bb-4218-beac-181a0d30e753/201905-IFC-SBO-FY20-FY22-Gearing-up-to-Deliver-IFC-3-0-at-Scale.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mF-.FRI.

- IFC. 2020a. “COVID-19 Financing: Criteria, Accountability, and Pipeline.” International Finance Corporation News & Events. Accessed 22 July 2020. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/news_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/news+and+events/covid-19/covid-19-financing.

- IFC. 2020b. “Creating Business, Creating Opportunities. Working Upstream.” International Financial Corporation. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/upstream.

- IFC. 2020c. “Careers with Impact. Working Upstream.” Accessed 22 July 2020. International Financial Corporation. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/careers_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/ifc+careers/upstream

- IFC. 2020d. “Transaction Advisory to the Solar Energy Corporation of India Limited in Identifying and Structuring of Renewable Energy PPP Projects (602265).” International Finance Corporation. https://disclosures.ifc.org/#/projectDetail/AS/602265.

- IFC. 2020e. “Transaction Advisory to Pham Ngoc Thac University of Medicine (Vietnam) in Structuring and Tendering a Public–Private Partnership Project (603207).” International Finance Corporation. https://disclosures.ifc.org/#/projectDetail/AS/603207.

- IFC. 2020f. “IFC Covid Response Projects.” Accessed 10 August 2020. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/news_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/news+and+events/covid-19/covid-19-projects.

- Igoe, Michael. 2019. “US Lawmaker Threatens World Bank Capital Increase over Private Sector Concerns.” Devex News, April 10. https://www.devex.com/news/us-lawmaker-threatens-world-bank-capital-increase-over-private-sector-concerns-94668.

- ILO. 2020. “Informal Economy.” International Labour Organisation. Accessed 22 July 2020. https://www.ilo.org/employment/units/emp-invest/informal-economy/lang–en/index.htm.

- ITUC. 2020. Market Fundamentalism and the World Bank Group. Technical Report. Brussels: International Trade Union Confederation. https://www.ituc-csi.org/market-fundamentalism-world-bank.

- Jomo, K. S., Anis Chowdhury, Krishnan Sharma, and Daniel Platz. 2016. “Public Private Partnerships and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Fit for Purpose?” UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. DESA Working paper DESA, No. 148.

- Kenny, Charles. 2020. “Transparency at Development Finance Institutions: Moving to Better Practice.” Center for Global Development, July 24. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/transparency-development-finance-institutions-moving-better-practice.

- Kenny, C., V. Ramachandran, and J. S. Masood. 2020. “Making the International Finance Corporation Relevant.” Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/making-international-finance-corporation-relevant.

- Kentikelenis, E. Alexander. 2017. “Structural Adjustment and Health: A Conceptual Framework and Evidence on Pathways.” Social Science & Medicine 187: 296–305.

- Kentikelenis, E. Alexander, Daniela Gabor, Isabel Ortiz, Thomas Stubbs, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler. 2020. “Softening the Blow of the Pandemic: Will the International Monetary Fund and World Bank Make Things Worse?” Lancet Global Health 8 (6): 758–759.

- Kim, Jim Yong. 2017a. “World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim Speech at the 2017 Annual Meetings Plenary.” The World Bank-Speeches & Transcripts, October 13. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2017/10/13/wbg-president-jim-yong-kim-speech-2017-annual-meetings-plenary-session.

- Kim, Jim Yong. 2017b. “Speech by World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim: Rethinking Development Finance.” The World Bank-Speeches & Transcripts, April 11. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2017/04/11/speech-by-world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim-rethinking-development-finance.

- Le Houerou, P. 2020. “CGD Conversations on COVID-19 and Development: Philippe Le Houerou.” Center for Global Development. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/event/cgd-conversations-covid-19-and-development-philippe-le-hou%C3%A9rou.

- Malpass, David. 2020a. “Remarks to G20 Finance Ministers.” World Bank Statement, April 15. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2020/04/15/world-bank-group-president-david-malpass-remarks-to-g20-finance-ministers.

- Malpass, David. 2020b. “Letter of WBG President to USA Secretary of the Treasury, CARES Act.” WBG Letter, March 20. https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/malpass_ltr_mnuchin_3202020.pdf.

- Oxfam. 2020a. “A Response Like No Other: Urgent Action needed by the International Financial Institutions.” Oxfam Statement ahead of the 2020 World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings, April 14. https://oxfam.app.box.com/s/84ezqxd21jd07m9yce2mgmcha0ry5oto.

- Oxfam. 2020b. “Transparency and Accountability: The Soap and Water for COVID-19 Financial Packages to the Private Sector.” Medium, May 6. https://medium.com/OxfamIFIs/transparency-and-accountability-the-soap-and-water-for-covid-19-financial-packages-to-the-private-5f0007fc3630.

- Romero, Maria Jose. 2015. What Lies Beneath? A Critical Assessment of PPPs and Their Impact on Sustainable Development. Report for the European Network on Debt and Development. Brussels: Eurodad. https://eurodad.org/files/pdf/559e6c832c087.pdf.

- Spicer, Martin. 2020. “Now is the Time to Mobilize Blended Finance Instruments.” World Bank blogs, May 4.https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/now-time-mobilize-blended-finance-instruments.

- Van Waeyenberge, Elisa. 2015. “The Private Turn in Development Finance.” Working paper No 140, Financialisation, Economy, Society & Sustainable Development (FESSUD) Project.

- Waters, Maxine. 2019. “The Annual Testimony of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the International Financial System.” US House Committee on Financial Services – Press Releases, April 9. https://financialservices.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=403630.

- WBG. 2018. “Sustainable Financing for Sustainable Development: World Bank Group Capital Package Proposal.” https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/280f4d9f-b889-4918-9eb2-bab6fc57c2f3/WBG+capital+package_post+DC+release.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=muWJ8zA.

- WBG. 2020a. “World Bank Group: 100 Countries Get Support in Response to COVID-19 (Coronavirus).” The World Bank Group-Press Release, May 19. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/05/19/world-bank-group-100-countries-get-support-in-response-to-covid-19-coronavirus.

- WBG. 2020b. COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Program and Proposed 25 Projects under Phase 1. Washington: The World Bank Group. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/993371585947965984/pdf/World-COVID-19-Strategic-Preparedness-and-Response-Project.pdf.

- WBG. 2020c. “Amid Multiple Crises, World Bank Group Refocuses Programs and Increases Financing to $74 billion in Fiscal Year 2020.” The World Bank-Press Release, July 10. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/07/10/amid-multiple-crises-world-bank-group-refocuses-programs-and-increases-financing-to-74-billion-in-fiscal-year-2020.

- WBG. 2020d. Saving Lives, Scaling-up Impact and Getting Back on Track. Covid-19 Crisis Response Approach Paper. Washington: The World Bank Group. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/136631594937150795/pdf/World-Bank-Group-COVID-19-Crisis-Response-Approach-Paper-Saving-Lives-Scaling-up-Impact-and-Getting-Back-on-Track.pdf.

- World Bank. 2017. Operationalizing the IDA18 IFC MIGA Private Sector Window. Washington: World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/928011520447801610/pdf/123995-BR-PUBLIC-IDA-R2017-0347-1.pdf.

- World Bank. 2019. Annual Report 2019. Washington: The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report.

- World Bank and IMF. 2015. From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance. Development Committee Discussion Note DC2015-0002. World Bank and IMF. https://www.devcommittee.org/sites/www.devcommittee.org/files/download/Documentation/DC2015-0002%28E%29FinancingforDevelopment.pdf.

- World Bank and IMF. 2017a. Forward Look – a Vision for the World Bank Group in 2013, Progress and Challenges. Development Committee Discussion Note DC2017-0002. World Bank and IMF. https://www.devcommittee.org/sites/dc/files/download/Documentation/DC2017-0002.pdf.

- World Bank and IMF. 2017b. Maximizing Finance for Development: Leveraging the Private Sector for Growth and Sustainable Development. Development Committee DC2017-0009. World Bank and IMF. https://www.devcommittee.org/sites/dc/files/download/Documentation/DC2017-0009_Maximizing_8-19.pdf.

- World Bank and IMF. 2018. Sustainable Financing for Sustainable Development: World Bank Group Capital Package Proposal. Development Committee DC2018-0002/P. World Bank and IMF. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/280f4d9f-b889-4918-9eb2-bab6fc57c2f3/WBG+capital+package_post+DC+release.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=muWJ8zA.

- World Bank and IMF. 2020. Update on World Bank Group Response to the COVID-19 Emergency. Development Committee DC2020-0003. World Bank and IMF. https://www.devcommittee.org/sites/dc/files/download/Documents/2020-04/Final%20DC2020-0003%20COVID-19%20emergency.pdf.