ABSTRACT

Public banks have played an important role in financing public water and sanitation services in Europe for over a century, but these activities have been largely ignored in the academic literature. This special issue is an initial corrective to this research gap, providing conceptual insights and empirical information on eight countries and regions in Europe, covering a wide range of public banks working with public water operators. This introductory article provides background rationale for the research, outlines our methodologies, frames the theoretical potentials of public banks in the water sector, highlights key findings and points to future possible research directions.

Introduction

Ask someone about a ‘public library’ or ‘public water’ and you are likely to begin from a shared sense of understanding. Ask them about a ‘public bank’ and you are more likely to draw blank stares. Despite having institutional roots that go back more than 600 years, the idea of a bank being ‘public’ is not firmly rooted in our collective sense of politics, let alone how public banks operate vis-à-vis other public services.

This special issue is an attempt to help unpack this mystification, with a focus on the links between public banks and the public provisioning of water and sanitation. It is the first detailed and systematic investigation of its kind – with eight case studies of public banks and public water operators in the European region – and forms part of a larger comparative global exploration of how public banks work with public water operators in other parts of the world (see municipalservicesproject.org).

Given the dearth of research on the topic we did not set out to test a particular hypothesis. With so little known about the extent and nature of public bank involvement in the water sector, and with highly contested notions of the purpose and potential of public banks, our goal was to collect reliable, comparative data to assess what is happening on the ground and its implications for public bank involvement in public water and sanitation services (WSS) in the future. We also aimed to test and adjust new research methodologies for further study.

The results of the research are as mixed as the countries and institutions investigated, but they reveal an enormous potential (and appetite) for progressive and sustainable forms of public bank financing of public water services in the European region. Although the examples range from the simple and inspiring to the complex and problematic, they illustrate that public banks can make a significant contribution to the sustainability and viability of public water systems.

Our interest in public banks is motivated in part by the massive gaps in water and sanitation infrastructure spending. Katko (Citation2016, p. 252) considers the lack of adequate investment in long-term infrastructure to be the biggest single challenge for water operators in the region, compounded by a growing complexity of environmental regulations, the costs of digitalization, challenges associated with the Covid-19 pandemic and the push for green infrastructure (McDonald et al., Citation2020; Newell, Citation2021; Siciliano et al., Citation2021).

But even with large injections of capital from higher levels of government most public water operators in Europe will need to borrow money to amortize these expenses over the long-term. Some of this lending will be provided by private financial institutions, but much of it will come from public banks, which have a long history of lending to public water operators in the region.

Despite this reality, public banks have been largely ignored in the literature on financing water services. This is due in part to a private finance bias in mainstream academic and policy circles (Cull et al., Citation2017; Demirgüç-Kunt & Servén, Citation2010; World Bank, Citation2001, Citation2012), but also because of a lack of research on the topic (Fonseca et al., Citation2021). There is a nascent body of literature on public banks in general, but ‘systematic academic research is patchy’ (Xu et al., Citation2021, p. 270), and there have been no detailed comparative case studies of public banks funding public water operators (McDonald et al., Citation2021). The creation of the Finance in Common network in 2020 – which brings together public development banks from around the world – is a positive sign of rising interest. But within this network, many of the member institutions do not explicitly differentiate between public and private ownership of water and sanitation. Some also promote ‘blended finance’ (using public money to entice or leverage private investment), public–private partnerships, and other forms of private sector engagement in infrastructure (see financeincommon.org). These policy orientations tend to mirror the World Bank’s ‘Maximising Finance for Development’ agenda, which disproportionately favours the interests of private investors over public ones (Dafermos et al., Citation2021).

Our starting point, by contrast, is to ask: How can public banks work with public water operators to create synergistic public good outcomes? We explore ‘actually existing’ relationships between public banks and public water operators to learn from these empirical experiences. In doing so, we are also exploring new theoretical and methodological terrains to inform future studies of public bank financing of public water, as well as their engagement in other public services such as electricity, health care and transportation.

Our main conclusion is that public banks have an important role to play in funding sustainable and equitable WSS in the European region, but that there is considerable scope for expansion and significant room for improvement. We begin this introduction with a summary of our theoretical understanding of what constitutes a ‘public bank’, to situate where we stand on the topic and to introduce Water International readers to what may be an unfamiliar subject matter. We also provide a brief empirical history of public banks, with a focus on their engagement in the water sector. This is followed by a description of the research methods employed and a summary of key findings from the case studies. We conclude with some thoughts on future research priorities.

What is a public bank?

Despite their long history and presence around the world, there remains relatively little scholarly agreement as to what constitutes a public bank. Public ownership is one facet of the discussion, but there is no consensus as to what level of state ownership or control is required. Moreover, there are some publicly owned banks without political authorities represented on their board (e.g., the Dutch NWB) while others have political representation on the board but no direct state ownership (e.g., Banco Popular in Costa Rica; Marois, Citation2021). We take a broad perspective on this matter, defining public banks as financial institutions that are majority owned by the state or some other public entity, or governed under public law or by public authorities, or that function according to a binding public mandate (or any combination thereof; Marois, Citation2021, pp. 11–12). We also highlight that public banks can operate at a municipal, national and international level, with some operating at multiple scales simultaneously (Clifton et al., Citation2021a; Schmit et al., Citation2011; Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF), Citation2017; Griffith-Jones & Ocampo, Citation2018; Marois, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021).

There is also the question of public purpose and public mandates – by which we mean the goals of a public bank and how those goals are legally and operationally codified in policies that inform practices – but here again there is no consistent definition. There are, however, two dominant perspectives that have tended to constrain rather than enable thinking about the place of contemporary public banks. On the one hand, ‘conventional’ economists believe that public banks naturally serve the whims of politicians, and as such are prone to political abuse and inherently less efficient than private banks (La Porta et al., Citation2002; Marcelin & Mathur, Citation2015). ‘Heterodox’ economists, meanwhile, argue that the purpose of public banks is to provide additionality; that is, to focus on doing what private banks cannot or will not do for economic growth and innovation. In this perspective, public banks are seen to have a fundamentally different logic than private banks and are therefore meant to stabilize markets and help overcome market failures (Henderson & Smallridge, Citation2019; Mazzucato, Citation2015; Ribeiro de Mendonça & Deos, Citation2017).

But conventional and heterodox views both adopt understandings of public banks that are ‘pre-social’, that is, having qualities not subject to historical change. The result is a literature that defines the ultimate purpose of public banks in predetermined yet polar opposite ways (Marois, Citation2022a, pp. 357–358, cf. La Porta et al., Citation2002, p. 67). This has promoted an ahistorical and relatively static reading of public banks that is unable to account for their institutional diversity and dynamism, let alone the nature of power and political struggles over what public banks do, and why, in different place and time bound contexts.

Our approach is to see public banks without recourse to an essential purpose, which enables analysis that can work with historical diversity and operational complexity. While public banks are institutions located within the public spheres of states, they can undertake financial intermediation and banking functions without an innate public direction or policy orientation. As such, public banks can operate according to public and/or private interests and, indeed, logics. This is because public banks exist and persist within the wider structures of class-divided, gendered, and racialized global capitalism and, like all public entities, are contested and evolving institutions that are made and remade in light of competing and often unequal power relations (Marois, Citation2021). This constitutes an alternative ‘dynamic’ view of public banks, and one which charts a path between the more polarized neoclassical and Keynesian views (Marois, Citation2022a).

Perhaps because of these theoretical tensions and practical antinomies, there is resurgent interest in and debate over what public banks can and ought to do (Clifton et al., Citation2021a; Marshall & Rochon, Citation2022; Mertens et al., Citation2021; Ray et al., Citation2020). In the United States, for example, civil society organizations and political leaders are pushing to create new public banks for the provision of more equitable and sustainable financial services in their communities, guided by normative commitments to addressing racial reparations with black and brown communities (Sgouros, Citation2022). In Europe, academics, policymakers and civil society have focused more on the potential of ‘greening’ public banks (Marodon, Citation2022). There is also a growing global interest in the democratization of public banks, as well as their contribution to definancialization (by which we mean a rolling back of the influence of financial motives, financial markets, and for-profit financial actors and institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies; Block & Hockett, Citation2022; Karwowski, Citation2019).

Despite these differences, there is a converging consensus on what public banks can do well – at least from a shared normative commitment to supporting economic development that is equitable, just and sustainable. While by no means applicable to all public banks, there is growing empirical evidence that they can function in the public interest and according to public purpose in a number of important ways: as providers of long-term and low-cost financing; as less-financialized, place-based lending institutions; as counter-cyclical and crisis-facing lenders; as funders of decarbonization and ecologically sustainable projects; as policy partners of government and community; as hubs of knowledge, expertise and development networks; and as political and economic counterweights to mainstream financial institutions (Barrowclough & Marois, Citation2022; Cassell, Citation2021; Griffith-Jones et al., Citation2022; Marois, Citation2021; Mikheeva, Citation2019; Ray et al., Citation2020). This issue contributes to this growing evidence.

A short history of public banking

While modern public banks are sometimes seen as originating in the post-Second World War era (Mazzucato & Penna, Citation2016, p. 308), the foundations of today’s public banking institutions emerged hundreds of years ago in European city-states. Barcelona created the first municipal bank in 1401, the Taula de Canvi, to help balance budgets and manage city finances (Milian, Citation2021). By the 16th and 17th centuries, public banks had emerged in Northern Europe and the American colonies (Roberds & Velde, Citation2014). By the start of the Second World War, public banks existed worldwide, from Argentina and Canada to Norway and Turkey. In most cases public banks provided funding and expertise, but the diverse histories of public banks in different societies also remind us that public banks are not inherently ‘good’, with many having been complicit in colonialism, slave-trading, war-making and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples’ lands by white farmers (McNally, Citation2020). There remain ongoing problematic practices among public banks that continue to demand that scholars and civil society remain vigilant in holding them to account (Antonowicz-Cyglicka et al., Citation2020; CEE Bankwatch Network, Citation2021).

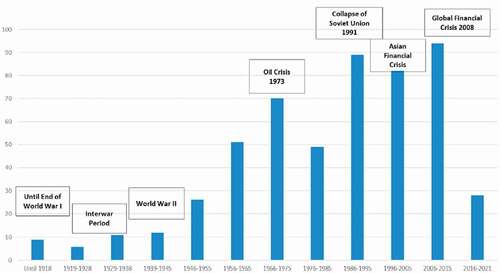

The era following the Second World War witnessed a massive expansion in public banks due to their ability to be crisis-facing financial institutions (). Post-war reconstruction gave rise to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), for example. Countries such as Turkey created new banks to support industrial development, small businesses and municipal infrastructure (Marois & Güngen, Citation2016). National liberation struggles saw newly independent governments nationalize private and colonial banks within their territories and create new ones (Marois, Citation2021). In Europe, a new range of regional banks emerged, including the Council of Europe Development Bank (established 1956, as the Resettlement Fund), the European Investment Bank (EIB) (established 1958) and the Nordic Investment Bank (established 1975).

Figure 1. Number of newly established public development banks and development financial institutions.

Global transitions to neoliberal strategies of development since the 1980s brought with them economic and ideological pressures to privatize existing public banks (von Mettenheim & Del Tedesco Lins, Citation2008), while multilateral development institutions militated against public bank expansion (World Bank, Citation2001). Correspondingly, the study of public banks nearly evaporated. The scholarship that did take place was dominated by conventional economistic views advocating privatization (Barth et al., Citation2006; La Porta et al., Citation2002).

More recent developments have renewed interest in public banks. The 2008–09 global financial crises not only brought the financial system to the edge of collapse, it threw communities and working-class families around the world into economic despair because of the excesses of profit-maximizing private financial institutions. The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate action has also underscored the failure of private finance to meaningfully confront climate change, while the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic witnessed private lenders withdrawing support when it was most needed.

Scholarship has since documented progressive alternatives provided by public banks in response to these crises (Brown, Citation2013; Marois, Citation2012, Citation2021; McDonald et al., Citation2020; Scherrer, Citation2017; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Citation2019). It is widely agreed that public banks are experiencing a ‘burgeoning renaissance worldwide’ (Xu et al., Citation2021, p. 271; cf. Clifton et al., Citation2021b; Mertens et al., Citation2021). Not only have the numbers of public banks been on the rise, ‘but their roles and prominence in the development agenda has also been boosted’ (Bilal, Citation2021, p. 6). This is perhaps nowhere more visible than in relation to the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the global ecological crisis (Marodon, Citation2022; Newell, Citation2021).

Nevertheless, there remains a sticky assertion that development transitions necessarily require more private finance because of perceived public bank incapacity (Newell, Citation2021, p. 106; Wang, Citation2016). This claim has stuck not only due to conventional preferences for market-based development, but also because of a severe underestimation of global public banking numbers and financial capacity. The main culprit here is the World Bank, whose reports have failed to capture the true extent of public banking capacity for years: a 2013 report finds only US$2 trillion in public banking assets, while a 2018 survey finds only US$940 billion (de Luna-Martínez et al., Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2012). For its part, the United Nations Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development (UN IATF) states that ‘national development banks’ have less than US$5 trillion in assets; hence, the perceived need to mobilize private finance to reach the anticipated US$90 trillion in sustainable infrastructure investments needed to achieve the SDGs (UN IATF, Citation2019). Only in 2022 did the IATF report update its data, identifying the ‘large footprint’ of some 527 public development banks with assets totalling US$13 trillion (UN IATF, 2002, p. 20) – data based on research undertaken by Finance in Common researchers (Xu et al., Citation2021).

This more recent accounting of the world’s public development banks is a welcome corrective. Yet it should be noted that the focus on development banks excludes other types of public banks. Based on BankFocus/Orbis data, Marois (Citation2021, p. 43) estimates that there are over 900 public retail, development and universal banks with combined assets of US$49 trillion dollars. If we include the wider ecosystem of public finance, including central banks, multilateral banks and public pension funds, there are more than 1650 institutions with US$82 trillion in assets (Marois, Citation2021, p. 55). Seen in this light, the ‘necessity’ of private finance fades substantively, suggesting that there is an urgent need to better understand the full scope of the public finance ecosystem and that public resources that can be better mobilized towards sustainable and equitable transitions.

Public banks in Europe

Looking at the EU-28 region of countries, there are 175 public banks holding approximately US$8.1 trillion in assets (not including the 385 individual German Sparkassen banks and their US$2 trillion in combined assets; Marois, Citation2021, p. 51; cf. Cassell, Citation2021). European public banks have also attracted much of the renewed scholarly interest in the topic, with general agreement that Europe is experiencing a resurgence in how public banks are positioned and coordinated vis-à-vis European Union priorities, green transitions and geopolitical concerns (Bilal, Citation2021; Clifton et al., Citation2021a; Mertens et al., Citation2021). As underscored by Bilal (Citation2021), there is a pan-European sense that public banks can help deal with the twin crises of climate change and financing the SDGs in a more coordinated, aligned and ‘Team Europe’ manner.

This resurgent European interest will have global implications, with institutions such as the EIB creating new international development finance operations (Antonowicz-Cyglicka et al., Citation2020; Marois, Citation2022b). European policymakers also increasingly see their public banks as geopolitical counterweights to the rise of southern-led multilaterals such as the New Development Bank (Barrowclough & Gottschalk, Citation2018; Mertens et al., Citation2021).

There is, however, nothing new about Europe’s national development banks engaging in development finance abroad. As early as 1958, the German KfW was active in international development, offering loans to Iceland, Sudan and India (Marois, Citation2021, p. 199). Today, its specialized arm, the KfW Development Bank, works globally, with more than 60 offices abroad lending approximately €11 billion in 2020 in sectors including water supply, energy, financial system development, health and education (Bilal, Citation2021, p. 17). The paper by Nadine Reis (Citation2022, this issue) on the KfW Development Bank in Latin America details the challenges of European public banks supporting water abroad.

Public banks in Europe nevertheless continue to face the impact of four decades of neoliberal restructuring. As with many public entities, there have been ongoing pressures to privatize public banks. Market-oriented regulatory changes, such as EU Competition Law and State Aid rules, have shrunk the spaces in which public banks can legitimately operate. The intensification of market-based competition and the rise of financialization have heaped new pressures on public banks operations (Scherrer, Citation2017). Increasingly, European development banks source the bulk of their inflows of capital from global financial markets, and so creditworthiness and credit ratings by market-oriented agencies have intensified. Public banks are also tasked with finding ways to de-risk private sector investments while pursuing public purpose impacts (Griffith-Jones et al., Citation2022; Mertens et al., Citation2021).

And yet, it is not all corporatized doom and gloom for Europe’s public banks. Indeed, many have taken up the challenge of financing sustainable development in less marketized ways. The German KfW is perhaps the most committed green (public) bank in the world (Geddes et al., Citation2018; Marois, Citation2021). Unique institutions, such as the Council of Europe Development Bank, continue to pursue an explicitly ‘social’ mandate (Reyes, Citation2020). The centuries-old German system of local public savings banks (the Sparkassen’s ‘boring business model’) retains assets in excess of US$2 trillion, anchored to local communities and guided by public mandates, despite the efforts of European private banks and regulators to eliminate them (Cassell, Citation2021).

European public banks also remain active in lending to the public water and sanitation sector, with a long history of doing so. As Juuti et al. (Citation2022, this issue) highlight in their study of the Nordic model of public banks, Norway’s Kommunalbanken has been lending to municipalities for more than 120 years. Schwartz and Marois (Citation2022, this issue) explore the Dutch NWB, literally the Dutch ‘WaterBank’, which was created in 1954 to finance water infrastructure. Elsewhere, as with the Nordic Investment Bank, problems of water pollution and contamination in the Baltic Sea spurred clean water to became a priority for the bank (Marois, Citation2021). In other cases, newly formed public banks such as the Banque des Territoires in France, created in 2018, immediately took up the challenge of funding municipal water and sanitation. In short, there is a rich history of public banks in the European Union that is ripe for sector-specific investigation.

Research methods

As outlined above, our perspective on public banks is a ‘dynamic’ one, seeing them as neither inherently good nor bad but rather as historically contested social, political and economic institutions shaped by forces that go beyond their ownership status. We did not set out to prove one perspective of public banks over another. Our aim has been to cast a wide inquisitive net to see how (and if) public banks operate in the water and sanitation sector.

The lack of qualitative comparative case study research on public banks upon which to base our research forced us to build new methodological models. Our decision was to develop standardized, semi-structured questionnaires that could lead to multiple types of responses, which we used to interview senior officials at public banks and public water operators in all eight of our case studies (see Appendices A and B for the questions asked). These questionnaires were developed in collaboration with the European Association of Public Banks as well as Aqua Publica Europea, a network of more than 60 public water operators across the region, who provided useful insights and practical assistance, including facilitating access to high-ranking officials in their respective sectors. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we primarily conducted interviews with senior officials throughout the European region online, and also accessed institutional documentation remotely.

The questionnaires were workshopped in advance by members of the research team to ensure a consistent comparative reference point, but they also allowed for flexibility where local context demanded. As such, case studies were guided by a common research framework but were able to capture the disparate realities of public banking and public water institutions in the region.

Our choice of case studies was driven by a number of factors. First, we aimed for geographical and institutional diversity, both in terms of public banks and public water operators. In doing so we identified locations where public banks have been active in lending to the water sector in relatively successful ways (the Nordic region, the Netherlands and Turkey) as well as locations where relations between public banks and public water operators have been either non-existent or fraught (Portugal and Spain). We also investigated two locations where public water operators have undergone significant transformations via remunicipalization (Spain and France), and a national public bank that operates in development finance globally (Germany’s KfW) to highlight the growing internationalization of Europe’s public banks. Finally, we included the EIB to provide a sense of the role of a European multilateral public bank in the WSS sector.

A final consideration in case study selection was the availability of suitable researchers, both in terms of familiarity with the country and institutions in question as well as their capacity to operate across a formidable disciplinary and methodological gap between academics who focus on public water and those who research public banks. In some cases, it was possible to bring together researchers from both sectors to collaborate, while other cases were completed by authors who became quick studies of the sector they were less familiar with. In all cases, internal and external peer reviews alongside regular editorial oversight by the guest editors (as specialists in public banks and public water) helped to reduce but not eliminate some of the incongruities between the final papers.

Key findings

Promising

We have summarized the key findings from the case studies into ‘promising’ and ‘cautionary’ categories. On the promising side we have identified eight trends. Not all apply to every bank, of course, but they do reveal the ability of public banks to work towards progressive and sustainable forms of water and sanitation financing.

The first, and most important, promising finding is that public banks can be remarkably effective and efficient providers of appropriate financing for public water operators. They are capable of providing large volumes of low-cost, easy-to-access, reliable and patient lending in ways that benefit water and sanitation systems in the short and long term. Public banks are also able to provide this lending on terms that private banks and other private financial institutions are seldom able or willing to compete with. In some cases, notably the Nordic cases and with the NWB, public banks have been providing this type of service for more than a century without a single loan default. This ability to provide appropriate finance was found in all the public bank/public water cases, and it is a finding consistent with the wider literature on the advantages of public banks funding public infrastructure (Bilal, Citation2021; Marois, Citation2021; Mertens et al., Citation2021). Perhaps the most notable case here is that of Turkey’s Ilbank, wherein Güngen (Citation2022, this issue) finds that it plays an almost irreplaceable role in funding small and medium-sized municipal water systems.

Second, the efficacy of public banks funding public water depends on a wide range of complex political, social, historical and institutional contexts, but the most effective public bank systems are startlingly simple. Despite the mystification of finance, at times perpetuated by private financial institutions and mainstream economists keen to persuade the general public that finance is performing extraordinarily complicated tasks, effective public bank financing can be understood by anyone familiar with the need to borrow money wisely on straightforward terms while reducing risks. With the exception of the more politically complex KfW Development Bank’s lending abroad (Ries, 2022) and EIB multilateral lending (Clifton et al., Citation2022), all the public banks researched for this issue had clear mandates and strong relationships with domestic public water operators or municipal authorities that were easy to understand and evaluate. None of the cases involved complex or opaque financial instruments. In the same way that public water operators can inform and engage end users on matters of effective water treatment and distribution, so too can public banks engage with the general public on matters that support and sustain public finance, helping to remove the cloak of mystery that typifies the finance sector.

Third, public banks can offer universal forms of lending and technical support that benefit all shapes and sizes of public water operators regardless of their wealth, population or location. All the public banks in our research illustrated the capacity to lend equally to small and large water authorities, municipal or otherwise. Turkey’s Ilbank tended not to lend to the largest municipalities because these authorities could access capital markets directly, and the KfW and EIB showed reluctance to lend to smaller entities, but all have and can lend across the board.

An important reason for this broad lending capacity is shared ownership and governance models that help pool risks and ensure that every WSS operator has access to similar lending terms and opportunities, allowing smaller and rural municipalities in particular to benefit from credit that would otherwise be very difficult or impossible to access. Pooling risks also creates borrowing clout, helping to raise cheaper capital. Sovereign backing by regional or national governments further strengthens this model, contributing to the existence of public banks in the European region with some of the highest credit ratings in the world (although there is good reason to question a disproportionate focus on public banks’ creditworthiness, as highlighted in a number of the contributions to this issue, notably Schwartz & Marois, Citation2022).

Fourth, public banks demonstrate that democratic forms of ownership and governance are possible within the financial sector, albeit it with different models and greater and lesser degrees of shareholder and stakeholder involvement. All the public banks in our case studies either have direct government representation on their boards or effective and collaborative working relationships with government. With the exception of Ilbank in Turkey, all operate in relatively transparent and accountable ways. As public institutions themselves, public banks have the potential to build dynamic, creative, democratic and synergistic ties with other public utilities and banks, creating a shared sense of public service understanding and institutional familiarity.

Fifth, public banks can have clear public purpose mandates that prioritize public services, sustainability and a host of other criteria which go beyond the financial metrics that dominate private financing discourses and operations. These public purpose mandates – especially if democratically shaped and managed – can guide public banks in ways that aim to optimize the larger public good rather than maximizing institutional profit. As part of these mandates, most of the public banks in our study have amassed deep sectoral expertise in water and sanitation, or if not in water directly then with municipal financing generally. The EIB, for example, has specialized staff and a dedicated water section (Clifton et al., Citation2022, this issue). In all the cases we examined, public bank staff had expert knowledge of their targeted public sector clients.

Sixth, public banks can collaborate with other local, national, regional and multilateral public banks in the form of public–public partnerships. In each of the case studies, public bank collaborations work to reduce financial risks, leverage project financing, provide additional expertise, gain knowledge of the local context, and contribute to knowledge sharing and trust-building across borders, sectors and institutions. Universally, collaboration trumped competition among the public banks.

Seventh, public banks can be leaders in green finance. Following on from European Union commitments to the United Nations 2030 SDGs, all the mainland European public banks have integrated sustainability criteria into their operations. Most are beginning to report directly on the SDGs, including SDG 6 (Water for All). The water and sanitation sector lends itself relatively easily to sustainability (e.g., via improved wastewater treatment and reduced water consumption levels). Some of the public banks in our case studies, notably the KfW and the Nordic banks, are world leaders in green finance (Juuti et al., Citation2022, Marois, Citation2021; Ries, 2022). Public banks were in fact amongst the early movers on climate finance. While having initially opened their green lending portfolios slowly and cautiously, they have moved rapidly and substantively of late towards accountably greening their portfolios (Marodon, Citation2022). Moreover, strict internal due diligence and transparency, combined with credible third-party assessments and political accountability, have allowed many public banks to avoid the accusations of ‘greenwashing’ that have tarnished much of the green financing in the private sector (Jones et al., Citation2020; Talbot, Citation2017). Nevertheless, important criticisms remain (Roggenbuck & Sol, Citation2022).

Lastly, the research strongly suggests that public banks can persist in ways that are less prone to political and electoral cycles given their robust, albeit varied, governance structures and institutional legacies, providing the potential for long-term lending strategies and institution building which extend beyond political personalities – the main exception being Ilbank. The long histories, functional stability and cross-party political acknowledgement of the advantages of most of the public banks in this issue are testament to this potential.

Cautionary

Of course, there is no single model of success and no guarantee that any of the promise of public banks can be realized universally or held in perpetuity. Political and institutional legacies are such that some goals are not possible in the short to medium terms, while workarounds that seem awkward from the perspective of one location may make sense in another. Some public banks have direct relationships with water operators while others work via municipalities. Some public banking systems are highly centralized while others are more fragmented. There are also widely divergent governance models, with some public banks integrating community stakeholders (KfW) while others are relatively firewalled from community representation (NWB, EIB, Portugal’s Caixa Geral de Depósitos (CGD) (Garcia-Arias et al., Citation2022, this issue) and Spain’s Instituto de Crédito Oficial (ICO) (Stadheim, Citation2022, this issue) or overly susceptible to unchecked and undue political abuse (Ilbank).

But even the most ‘ideal’ of public banks are not a ‘silver bullet’ panacea for funding WSS. Given the scale of the infrastructure challenge, massive government budget injections will be required to address the social and environmental impacts of WSS investments in the European region and in development finance. Relying too heavily on loans at the local level is not politically or financially sustainable – particularly for smaller WSS operators – as they can lead to debt traps. Public bank borrowing must therefore be seen as a strategic form of investing in site-specific WSS priorities that complement, rather than replace, larger national and regional government direct financing initiatives.

Each of the case studies also supports adopting a cautionary approach to a growing and continued emphasis on cost recovery in WSS, particularly given that cost recovery efforts have largely failed to provide sufficient incomes for long-term capital expenditures and can disproportionately affect lower income households (Berbel & Expósito, Citation2020; Moral Pajares et al., Citation2019; Tsani et al., Citation2020). This is perhaps most pronounced in the KfW Development Bank, Ilbank and Nordic bank cases. The fact that many local municipal politicians are reluctant to raise water tariffs to the levels required to meet long-term capital costs for fear of political backlash makes a reliance on cost recovery all the more untenable in many cases. In others, notably Paris’ remunicipalized water operator Eau de Paris, cost recovery can still be an effective part of WSS investments if done transparently and equitably (Butzbach & Spronk, Citation2022, this issue).

Another concern relates to the ambiguous stance taken by public banks in these case studies towards funding public water. Although some lend exclusively to public water operators (NWB, Iller Bank and the Nordic banks) this is largely because the vast majority of water operators in their regions are publicly owned, not because of any clear legal mandate or ideological impulse to do so. In fact, many of the public bank officials we spoke with were agnostic on the topic of public versus private water, with some providing loans to both public and private water operators (EIB, KfW, ICO and CGD). And although water privatization appears to have peaked in most of Europe, with a growing wave of remunicipalizations contributing to a partial reversal of earlier privatization efforts (McDonald & Swyngedouw, Citation2019; Turri, Citation2022), there is no guarantee this will continue. EU legislative bodies and financing agencies continue to push for private sector investment in the sector, and for public banks to use public financing to de-risk private investments (Cuadrado-Ballesteros & Peña-Miguel, Citation2018; van den Berge et al., Citation2022). All the public banks studied could benefit from a clearer legal mandate to support public water.

This lack of a clear political commitment to public water is strikingly illustrated by two of our case studies involving water remunicipalization: Paris (France) and Valladolid (Spain) (Butzbach & Spronk, Citation2022; Garcia-Arias et al., Citation2022). Despite strong evidence that remunicipalization has saved money and democratized water services in both locations, neither of these water operators have worked closely with public banks for their financing needs. Nor has there been political discussion as to the potential for public banks to support water remunicipalization in other parts of France or Spain, or anywhere else in Europe for that matter. Similar issues arose with the KfW Development Bank funding water abroad.

Finally, it is important to note that public banks themselves remain targets of privatization, commercialization and financialization, and are often judged in relation to private banking financial criteria and commercially oriented international credit ratings such as Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s and Fitch (cf. Cull et al., Citation2017; Scherrer, Citation2017). Advancing the potential for public banks to deepen their engagement with public water operators and other public services will therefore depend in part on their own ability to remain within the public realm.

Conclusions

The cases in this issue provide evidence of the enormous potential for public banks to finance public water in Europe, as well as the urgent need for more research on the topic. Additional comparative case studies are required to develop a richer empirical and theoretical perspective of the diversity of public banks and public water operators in the region, and the extent to which a progressive model of public bank financing of WSS could be developed on a more regional scale.

Case study research in Asia, Middle East, Africa and Latin America is even more urgent given the dire nature of water and sanitation access in these regions and the relative dearth of funding alternatives. These regions are very different from Europe in terms of credit risks, institutional transparency, variety of public banking institutions and the ongoing influence of international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, making a transfer of academic theory and methods a complicated one. Nonetheless, similar context-sensitive approaches to research could help to develop a better sense of the potential for public banks to play a more progressive role in WSS financing at a global level.

There is also a need to expand thematic approaches to this research topic. Missing from our case studies were more systemic assessments of subjects such as equity, diversity and gender (Hessini, Citation2020; Vincensini, Citation2021). The scale and urgency of WSS financing should not obscure these critically important social, economic and political factors. Although European countries are amongst the best performers in the world in terms of water access and affordability, water poverty is a growing concern in the region and it disproportionality affects immigrants, people of colour and low-income households (Anthonj et al Citation2020; Ezbakhe et al., Citation2019; Spronk, Citation2020). It is crucial that we develop a better understand of how and if financing from public banks can address these equity questions and how it fits with their public purpose mandates and governance.

Similar calls to action must be made around the need for research on how ‘green’ public banks really are in their WSS portfolios, how they address the different needs and demands of indigenous communities, whether they are interested in alternative forms of benchmarking, and the extent to which factors such as Islamic forms of financing shape the way they operate.

We plan to expand our work on these topics in the future and will use the lessons from this issue as a platform for further research. We invite any interested parties to join us in this endeavour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anthonj, C., Setty, K. E., Ezbakhe, F., Manga, M., & Hoeser, C. (2020). A systematic review of water, sanitation and hygiene among Roma communities in Europe: Situation analysis, cultural context, and obstacles to improvement. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 226, 113506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113506

- Antonowicz-Cyglicka, A., Bourgin, C., Roggenbuck, A., & Sol, X. (2020). Can the EIB become the “EU development bank”? A critical view on EIB operations outside Europe. CEE Bankwatch Network and Counter Balance. Retrieved August 12, 2021, from https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-Can-the-EIB-become-the-EU-Development-Bank_Online.pdf

- Barrowclough, D., & Gottschalk, R. (2018). Solidarity and the South: Supporting the new landscape of long-term development finance (UNCTAD Research Paper, No. 24 UNCTAD/SER.RP/2018/6). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

- Barrowclough, D. V., & Marois, T. (2022). Public banks, public purpose, and early actions in the face of Covid-19. Review of Political Economy, 34(2), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2021.1996704

- Barth, J. R., Caprio, G., & Levine, R. (2006). Rethinking bank regulation: Till angels govern. Cambridge University Press.

- Berbel, J., & Expósito, A. (2020). The theory and practice of water pricing and cost recovery in the Water Framework Directive. Water Alternatives, 13(3), 659–673. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol13/v13issue3/602-a13-3-20/file

- Bilal, S. (2021). The rise of public development banks in the European financial architecture for development (Working Paper 12/2021). Elcano Royal Institute. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://media.realinstitutoelcano.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/wp12-2021-bilal-rise-of-public-development-banks-in-european-financial-architecture-for-development.pdf

- Block, F., & Hockett, R. (Eds.). (2022). Democratizing finance: Restructuring credit to transform society. Verso.

- Brown, E. (2013). The public banking solution: From austerity to prosperity. Third Millennium Press.

- Butzbach, O., & Spronk, S. (2022). Public banks and the remunicipalization of water services in Paris, France. Water International, 47(5), 751–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2101085

- Cassell, M. K. (2021). Banking on the state: The political economy of public savings banks. Agenda Publishing.

- CEE Bankwatch Network. (2021, July 13). ‘Highway of destruction’ raises questions about effective and safe access to remedy and poor human rights safeguards at the EIB [ Briefing]. Retrieved September 15, 2021, from https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-13_Mombasa-road-briefing_final.pdf

- Clifton, J., Díaz Fuentes, D., & Howarth, D. (Eds.). (2021a). Regional development banks in the world economy. Oxford University Press.

- Clifton, J., Díaz-Fuentes, D., Howarth, D. (2021b). Regional development banks in the world economy. In J. Clifton, D. D. Fuentes, & D. J. Howarth (Eds.), Regional development banks in the world economy (pp. 1–14). Oxford University Press.

- Clifton, J., Díaz-Fuentes, D., & Kavvadia, H. (2022). The European Investment Bank and its role in financing public water. Water International, 47(5), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2103775

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Peña-Miguel, N. (2018). The socioeconomic consequences of privatization: An empirical analysis for Europe. Social Indicators Research, 139(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1713-2

- Cull, R., Martinez Peria, M. S., & Verrier, J. (2017). Bank ownership: trends and implications (IMF Working Paper. WP/17/60). International Monetary Fund.

- Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D., & Michell, J. (2021). The Wall Street consensus in pandemic times: What does it mean for climate-aligned development? Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 42(1/2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1865137

- de Luna-Martínez, J., Vicente, C. L., Arshad, A. B., Tatucu, R., & Song, J. (2018). 2017 survey of national development banks. World Bank Group.

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Servén, L. (2010). Are all the sacred cows dead? Implications of the financial crisis for macro- and financial policies. The World Bank Research Observer, 25)1(1), 91–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkp027

- Ezbakhe, F., Giné-Garriga, R., & Pérez-Foguet, A. (2019). Leaving no one behind: Evaluating access to water, sanitation and hygiene for vulnerable and marginalized groups. Science of the Total Environment, 683, 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.207

- Fonseca, C., Mansour, G., Smits, S., & Rodríguez, M. (2021). The role of National Public Development Banks in financing the water and sanitation SDG 6, the water related goals of the Paris Agreement and biodiversity protection. French Development Agency (AFD). Retrieved November 2, 2021, from https://financeincommon.org/

- Garcia-Arias, J., March, H., Alonso, N., & Satorras, M. (2022). Public water without (public) financial mediation? Remunicipalizing water in Valladolid, Spain. Water International, 47(5), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2057071

- Geddes, A., Schmidt, T. S., & Steffen, B. (2018). The multiple roles of state investment banks in low-carbon energy finance: An analysis of Australia, the UK and Germany. Energy Policy, 115, 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.01.009

- Griffith-Jones, S., & Ocampo, J. A. (Eds.). (2018). The future of national development banks. Oxford University Press.

- Griffith-Jones, S., Spiegel, S., Xu, J., Carreras, M., & Naqvi, N. (2022). Matching risks with instruments in development banks. Review of Political Economy, 34(2), 197–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2021.1978229

- Güngen, A. R. (2022). ‘No one can compete since no one dares to lend more cheaply!’: Turkey’s Ilbank and public water finance. Water International, 47(5), 771–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2096251

- Henderson, J., & Smallridge, D. (2019). Trade finance gaps in a heightened regulatory environment: The role of development banks. Global Policy, 10(3), 432–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12715

- Hessini, L. (2020). Financing for gender equality and women’s rights: The role of feminist funds. Gender and Development, 28(2), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2020.1766830

- Jones, R., Baker, T., Huet, K., Murphy, L., & Lewis, N. (2020). Treating ecological deficit with debt: The practical and political concerns with green bonds. Geoforum, 114, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.014

- Juuti, P. S., Juuti, R. P., & McDonald, D. A. (2022). Boldly boring: Public banks and public water in the Nordic region. Water International, 47(5), 791–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2072149

- Karwowski, E. (2019). Towards (de-)financialisation: The role of the state. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43(4), 1001–1027. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez023

- Katko, T. S. (2016). Finnish water services: Experiences in global perspective. Finnish Water Utilities Association.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). Government ownership of banks. The Journal of Finance, 57(1), 265–301.

- Marcelin, I., & Mathur, I. (2015). Privatization, financial development, property rights and growth. Journal of Banking & Finance, 50, 528–546.

- Marodon, R. (2022). Can development banks step up to the challenge of sustainable development? Review of Political Economy, 34(2), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2021.1977542

- Marois, T. (2012). States, banks, and crisis: Emerging finance capitalism in Mexico and Turkey. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Marois, T., & Güngen, A. R. (2016). Credibility and class in the evolution of public banks: The case of Turkey. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(6), 1285–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1176023

- Marois, T. (2021). Public banks: Decarbonisation, definancialisation, and democratisation. Cambridge University Press.

- Marois, T. (2022a). A dynamic theory of public banks (and why it matters). Review of Political Economy, 34(2), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2021.1898110

- Marois, T. (2022b). Shaping the future of EIB Global: Reclaiming public purpose in development finance. Eurodad. Retrieved May 30, 2022, from https://www.eurodad.org/shaping_future_eib_global

- Marshall, W. C., & Rochon, L.-P. (2022). Understanding full investment and the potential role of public banks. Review of Political Economy, 34(2), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2021.2013633

- Mazzucato, M. (2015). The entrepreneurial state (Revised ed.). Anthem Press.

- Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. C. R. (2016). Beyond market failures: The market creating and shaping roles of state investment banks. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 19(4), 305–326.

- McDonald, D. A., & Swyngedouw, E. (2019). The new water wars: Struggles for remunicipalisation. Water Alternatives, 12(2), 322–333. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol12/v12issue3/528-a12-2-11/file

- McDonald, D. A., Marois, T., & Barrowclough, D. V. (Eds.). (2020). Public banks and Covid-19: Combatting the Pandemic with public finance. Municipal Services Project (Kingston). UNCTAD and Eurodad.

- McDonald, D. A., Marois, T., & Barrowclough, D. (Eds.). (2021). Public banks and covid-19: Combatting the pandemic with public finance. UNCTAD and Eurodad.

- McNally, D. (2020). Blood and money: War, slavery, finance, and empire. Haymarket Books.

- Mertens, D., Thiemann, M., Volberding, P. (2021). Introduction: The making of the European field of development banking. In D. Mertens, M. Thiemann, & P. Volberding (Eds.), The reinvention of development banking in the European Union: Industrial policy in the single market and the emergence of a field (pp. 1–32). Oxford University Press.

- Mikheeva, O. (2019). Financing of innovation: National development banks in newly industrialized countries of East Asia. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 42(4), 590–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01603477.2019.1640065

- Milian, L. M. (2021). The Taula de Canvi of Barcelona: Success and troubles of a public bank in the fifteenth century. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, 13(2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/17546559.2021.1893896

- Miller, M., Roger, L., Prizzon, A., & Hart, T. (2021, October 11). Multilateral finance in the face of global crisis (ODI Briefing/Policy Papers). Overseas Development Institute.

- Moral Pajares, E., Gallego Valero, L., & Román Sánchez, I. M. (2019). Cost of urban wastewater treatment and ecotaxes: Evidence from municipalities in Southern Europe. Water, 11(3), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030423

- Newell, P. (2021). Power shift: The global political economy of energy transitions. Cambridge University Press.

- Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum. (2017). Global public investor 2017.

- Ray, R., Gallagher, K. P., & Sanborn, C. A. (2020). Standardizing sustainable development? Development Banks in the Andean Amazon. In R. Ray, K. P. Gallagher, & C. A. Sanborn Eds., Development banks and sustainability in the Andean Amazon (pp. 1–46). Routledge. (2019).

- Reis, N. (2022). Between development and banking: The KfW Development Bank in Latin America’s water sector. Water International, 47(5), 810–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2105533

- Reyes, O. (2020). The Council of Europe Development Bank and Covid-19. In D. A. McDonald, T. Marois, & D. Barrowclough (Eds.), Public banks and Covid-19: Combatting the pandemic with public finance (pp. 113–135). UNCTAD and Eurodad.

- Ribeiro de Mendonca, A. R., & Deos, S. (2017). Beyond the market failure argument: Public banks as stability anchors. In C. Scherrer (Ed.), Public banks in the age of financialization (pp. 13–28). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Roberds, W., & Velde, F. R. (2014) Early public banks (Working Paper 2014-03). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

- Roggenbuck, A., & Sol, X. (2022). Flattering to deceive: A reality check for the ‘EU Climate Bank’, Counter Balance and CEE Bankwatch Network, Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://bankwatch.org/publication/flattering-to-deceive-a-reality-check-for-the-eu-climate-bank

- Scherrer, C. (Ed.). (2017). Public banks in the age of financialization: A comparative perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Schmit, M. L. G., Denuit, T., & Warny, C. (2011). Public financial institutions in Europe. European Association of Public Banks.

- Schwartz, K., & Marois, T. (2022). Untapping the sustainable water bank’s public financing for Dutch drinking water companies. Water International, 47(5), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2080518

- Sgouros, T. (2022). Public bank east bay viability study. Commissioned by Friends of the Public Bank East Bay. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://publicbankeastbay.org/publications

- Siciliano, G., Wallbott, L., Urban, F., Dang, A. N., & Lederer, M. (2021). Low‐carbon energy, sustainable development, and justice: Towards a just energy transition for the society and the environment. Sustainable Development, 29(6), 1049–1061. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2193

- Spronk, S. (2020). COVID-19 and structural inequalities: Class, gender race and water justice. In D. A. McDonald, S. J. Spronk, & D. Chavez (Eds.), Public water and Covid-19: Dark clouds and silver linings (pp. 25–48). Transnational Institute.

- Stadheim, V. (2022). Squeezed by austerity and pressured to recover costs: Portugal’s municipal water operators in need of public bank finance. Water International, 47(5), 711–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2097599

- Talbot, K. M. (2017). What does green really mean: How increased transparency and standardization can grow the green bond market. Villanova Environmental Law Journal, 28, 127–138.

- Tsani, S., Koundouri, P., & Akinsete, E. (2020). Resource management and sustainable development: A review of the European water policies in accordance with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Environmental Science & Policy, 114, 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.09.008

- Turri, V. M. (2022). Understanding European drinking water services remunicipalisation: A state of literature analysis. Cities, 120, 103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103437

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2019). Financing a global green new deal (Trade and Development Report 2019). United Nations.

- United Nations Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development. (2019) Financing for sustainable development report.

- van den Berge, J., Vos, J., & Boelens, R. (2022). Water justice and Europe’s Right2Water movement. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 38(1), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2021.1898347

- Vincensini, V. (2021). Public development banks driving gender equality: An overview of practices and measurement frameworks. French Development Agency (AFD) and UN Women.

- von Mettenheim, K., & Del Tedesco Lins, M. A. (Eds.). (2008). Government banking: New perspectives on sustainable development and social inclusion from Europe and South America. Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- Wang, Y. (2016, July). The sustainable infrastructure finance of China development bank: Composition, experience and policy implications (Global Economic Governance Initiative Working Paper, No. 5). Boston University Global Economic Governance Initiative.

- World Bank. (2001). Finance for growth: Policy choices in a volatile world.

- World Bank. (2012). Global financial development report 2013: Rethinking the role of state in finance.

- Xu, J., Marodon, R., Ru, X., Ren, X., & Wu, X. (2021, December). What are public development banks and development financing institutions ? Qualification criteria, stylized facts and development trends. China Economic Quarterly International, 1(4), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceqi.2021.10.001