ABSTRACT

Extant literature point to difficulties related to enabling transitions to sustainable tourism development. Supplementing hereto, this study explored how we may collaboratively design (co-design) opportunities for sustainable tourism futures. Based on fieldwork involving co-designing tourism with a diverse range of practitioners centred on Lake Mjøsa in Norway, it unfolds how an understanding and construction of ‘Our Mjøsa’ surfaced. By analysing the contingent processes and ensuing outcomes, the study introduces a framework for understanding how opportunities may – and may not – emerge and enable sustainable development. The framework comprises four dynamic zones including two of inertia, one of sustaining tourism and one of re-imagining tourism. The study argues that traditional tourism approaches often are located within zones of inertia and sustaining tourism and consequently overlook or fail to engage series of opportunities for sustainability transitions. Within the latter zone of re-imagining tourism, it shows how opportunities can emerge as ‘yours and mine’, together as our sustainable tourism futures. Altogether, the findings suggest that the ongoing tempo-spatial shifts and flows on the verges of inertia, sustaining tourism and re-imagining tourism allow for simultaneously revealing and making more transparent the implicit and explicit assumptions underpinning current tourism practice, while re-imagining our sustainable tourism futures.

Introduction

In the wake of Our Common Future, also known as the Brundtland Report (World Commission of Environment and Development, Citation1987), the continued embedding of tourism within growth and development paradigms is well-established (e.g. Aall, Citation2014; Bramwell & Lane, Citation1993; Butler, Citation1998; Hall & Lew, Citation1998; Weaver, Citation2009). Scholars have cautioned that this implicates typically little but tourism itself is sustained, leaving scant attention to the wider implications for sustainable development (Hunter, Citation1995, Citation1997; Liburd & Edwards, Citation2010; Sharpley, Citation2000). Thus, the agenda of Transforming Our World (United Nations, Citation2016) has stimulated renewed critical interest among tourism scholars and practitioners in re-appreciating how tourism can overcome the ‘Brundtland-as-usual’ logic (Hall, Citation2019, p. 12) and engage meaningfully in sustainable development (Boluk et al., Citation2019; Bricker, Citation2018; Fennell & Cooper, Citation2020; Higham & Miller, Citation2018; Liburd, Citation2018; Sharpley, Citation2020).

The ineffectiveness of traditional tourism planning and destination management models is partly rooted in their reductionist nature. In following deterministic and linear cause-and-effect representations assuming that tourism can be efficiently managed and controlled by proper means of intervention, they fail to recognise the inherent complexity and values involved and altogether rationalise the process (Hall et al., Citation2018; Liburd, Citation2018; McDonald, Citation2009; McKercher, Citation1993; Miller & Twining-Ward, Citation2005). This study argues that tourism largely still hinges on a utilitarian justification of development of tourism and when narrowly interpreted in terms of its economic outcomes, and inserted in prescriptive planning processes, a normative management-oriented rationale of developing tourism for others easily prevails.

Appreciating the complexity and wickedness of the global sustainability challenges, which are not clearly definable and have multiple solutions (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973), brings participation and human values to the fore. Admittedly, without something to sustain, sustainable development is void of meaning. Who has the power and capacity to decide what to sustain through tourism, on behalf of whom, and where, how, when and if it should be developed? (Hughes & Morrison-Saunders, Citation2018; Liburd, Citation2018). This study challenges the notion of developing tourism for others and seeks ways of developing and researching with others. Such shift acknowledges that a sustainable development process thrives on a pluralisation of the values, norms, ideologies, knowledges and worldviews of those affected by, and involved in, tourism (Hall, Citation2008; Hall, Citation2019; Jamal & Getz, Citation1999). Reflecting on the broader values and ethics of sustainable tourism development, a democratisation of tourism research is argued as vital to drive the needed paradigmatic shift of re-imagining and transforming tourism where new understanding, ownership and an ethics of care emerge and synthesise among those involved (Campos & Hall, Citation2019; Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018; Fennell, Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2018; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014). Therefore, with others, this study specifically contributes to the emergent field and practice of collaboratively designing tourism (tourism co-design).

Framed as a ‘a co-generative and co-learning research and development endeavour’, tourism co-design contributes an innovative range of processes, methods and interventions, enabling those involved to explore with others sustainable tourism futures as spaces of possibilities (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018; Liburd et al., Citation2017). By moving from experiment to experiment and sensitively responding to the unfolding inquiry, participants may simultaneously reveal a constrained present while imagining and navigating toward its future betterment within specific tourism contexts (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018; Liburd et al., Citation2020; Rogal & Sànchez, Citation2018). The possibility to re-imagine tourism and emergent opportunities for novelty may – and as critically demonstrated in this study sometimes may not – surface through the ongoing interactions and exploration of variations of expression and interpretation of those involved (Stacey, Citation2001).

Drawing on fieldwork of collaboratively co-designing tourism with various practitioners associated with Norway’s largest freshwater lake, Lake Mjøsa, the overarching aim of this study was to explore how tourism co-design may engender emergent opportunities to encourage sustainable tourism futures. Through multiple rounds of abductive reinterpretation and theorising focused on the processes of co-designing tourism and co-generated forms and outcomes of co-designing tourism, the study introduces a dynamic framework comprising two zones of inertia, one of sustaining tourism and one of re-imagining tourism. Further exploration reveals how it is within the ongoing tempo-spatial shifts and flows among zones that it becomes possible to reveal the implicit and explicit assumptions underpinning current tourism practice while simultaneously re-imagining sustainable tourism futures.

In the remainder of the paper, key concepts and definitions, including dynamics of developing tourism for, and, of are first discussed and followed by an introduction to, and positioning of, tourism co-designing with others. Second, a detailed outline of the actual process of co-designing with others is provided. Third, key theoretical concepts, the process of inquiry and findings are synthesised to shape an original framework and discussions.

Theory

Developing tourism ‘for’ others

Tourism is a growing global economic powerhouse and one of the most polluting industries, making it increasingly less sustainable according to resource usage (Buckley, Citation2012; Rutty et al., Citation2015). While this is clearly an unsustainable outlook, it illustrates that tourism hinges on the assumption that growth is the norm (Hall et al., Citation2018). The continued idea that it is possible to balance economic, socio-cultural and ecological resources, as implied in the Brundtland Report (WCED, Citation1987), is worrisome. Accompanied by a vague understanding of sustainability, the ‘Brundtland-as-usual’ logic (Hall, Citation2019, p. 12) paved the way for a competitive tourism industry to metastasise through ‘sustainable growth’, often at the expense of wider sustainable development, with little regard for limits to growth (Bramwell & Lane, Citation1993; Bricker, Citation2018; Butler, Citation1999; Gössling et al., Citation2009; Hall et al., Citation2015; Hall & Lew, Citation1998). This raised a fundamental question about what is actually sustained through tourism development other than tourism itself? Hunter (Citation1995, Citation1997) coined the term ‘tourism-centric’ to describe a situation where destinations become commodified for sale to tourists. Such situation often increases competition for resources and tourism (McKercher, Citation1993), and arguably reinforces the tourism-centricity.

Though these concerns are not new, they prove no less relevant today considering how, e.g. the UN World Tourism Organization (Citation2017) was quick to frame the new sustainable development goals (UN, Citation2016) as an opportunity to stimulate ‘true’ business opportunities – that is, opportunities that are competitive and increase profit (p. 7) – as have many national and regional tourism strategies. However, the intended trickle-down effects of such macro-level policies have come under question, and scholars continue to underline the lack of operationalisation of the praiseworthy values of sustainable development (Butler, Citation1998; Weaver, Citation2009; Wall, Citation2018; Sharpley, Citation2020). The persistent ineffectiveness of traditional tourism planning and destination management models is partly rooted in the reductionist nature of their deterministic and linear cause-and-effect representations, where there is an implicit or explicit assumption that tourism can be efficiently managed and controlled by proper means of intervention (Hall et al., Citation2018; Liburd, Citation2018; McDonald, Citation2009; McKercher, Citation1993; Miller & Twining-Ward, Citation2005). To challenge the tourism-centric view, it is critical to acknowledge that tourism is a complex, social and fleeting phenomenon spanning multiple sectors, industries, places and people. Unlike complicatedness, complexity appreciates that tourism shapes through dynamic and ever-continuous processes of emergent becoming, where the sum of the interacting parts and relationships is greater than the sum of the whole (Hall et al., Citation2018). Appreciating the complexity and wickedness of the global sustainability challenges, which are not clearly definable and have multiple solutions (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973), brings participation and human values to the fore as now unfolded.

Development ‘of' and ‘on’ communities

Sustainable development has shifted away from past principles towards more formalised and comprehensive reports urging stakeholders to pursue specific goals and targets to achieve sustainable outcomes (Fennell & Cooper, Citation2020; Hall, Citation2008). Therefore, it is noteworthy that the new agenda acknowledges contextual differences and inclusively writes that ‘we the peoples’ are embarking upon this journey of transforming our world (UN, Citation2016, p. 16). Indeed, it is well-established that participation is vital for sustainable tourism development and can empower others and challenge traditional ways of doing tourism (Bramwell, Citation2010; Bramwell & Lane, Citation2011; Hardy et al., Citation2002; Jamal & Getz, Citation1999). However, despite the new promises and principles of participation and public–private relationships in the changing landscape of governance series of issues prevail. Civic society, the public and residents often play a minor role or are even excluded in favour of accommodating tourists’ needs, and when involved authorities may have already prescribed the direction of decisions where tourism developed for ‘public interests’ oftentimes equates to economic or narrow sectorial interests (Hall, Citation2008; Hughes & Morrison-Saunders, Citation2018; Moscardo, Citation2011). Using a tranisition management approach, Gössling et al. (Citation2012) explored how a Norwegian government-led initiative aimed at mobilising key tourism stakeholders could proactively facilitate sustainability transitions. While they concluded that stakeholder involvement can increase knowledge and enable those involved to articulate and envision a desirable future, change and transition pathways are more likely to occur via doable incremental steps than via disruptive systemic change.

Hall (Citation2008) clarified that community-oriented bottom-up approaches concern development in communities, not development of communities. In examining university–community networks, Cockburn-Wootten et al. (Citation2018) asserted that considerable tourism research has been on communities rather than in and with communities of practice – a vital difference for ownership and creating more ethical traction for sustainable change. This shift acknowledges that sustainable development is a contested process, which thrives on the pluralisation of the values, norms, ideologies, knowledges and worldviews of those affected by, and involved in, tourism (Hall, Citation2008; Hall, Citation2019; Jamal & Getz, Citation1999). Reflecting on the broader values and ethics of sustainable tourism development, a democratisation of tourism research is vital to drive the much needed paradigmatic shift towards re-imagining and transforming tourism by allowing new understanding, knowledge and importantly an ethics of care to emerge among involved stakeholders (Campos & Hall, Citation2019; Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018; Fennell, Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2018; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014).

Summing up and bringing together the above sections, tourism largely still hinges on a utilitarian justification of development of tourism and when narrowly interpreted in terms of its economic outcomes, and inserted in prescriptive planning processes, a normative management-oriented rationale of developing tourism for others easily prevails. Recognising and adding to the importance of stimulating a fundamentally new paradigmatic position to sustainable tourism development, the following section discusses the possibility of designing tourism with others.

Designing tourism ‘with’ others

Co-design can be traced to the Scandinavian School of Design arising during the 1980s and its ideas of participation. Led by Scandinavian union associations, the rationale was to involve workers in the development and implementation of innovations in their workplaces. According to the political agenda supporting this rationale, those affected should have a voice and influence (Bratteteig et al., Citation2012; Robertson & Simonsen, Citation2012). Since then, participatory and collaborative design have advanced and dispersed. A main principle remains the involvement of those affected to safeguard their voices in the design process while clarifying potential tensions (Buur & Larsen, Citation2010). Working within the tensions of ‘what is’ and ‘what may become’, participatory and collaborative design seek to simultaneously reveal limits or problems within a present situation while inviting those affected to work towards its improvement (Bratteteig et al., Citation2012; Robertson & Simonsen, Citation2012). In this study, this meant working with those affected by tourism while envisioning desirable futures. Whitham et al. (Citation2019) framed co-design research practice as ‘seeking new ways of connecting people to shared and individual futures, unlocking, amplifying and catalysing individual creative potential, and contributing to broader, systematic shifts in governance, politics, and social practice’ (p. 3). This framing enlarges the scope of co-design from being the solution to a problem or well-defined pathway for products and service provisions by recognising the complexity of sustainable development and the importance of considering the diversity of individuals implicated in it.

Bridging co-design and sustainable tourism development, tourism co-design is an emergent field and practice of collaboratively designing tourism (Duedahl & Liburd, Citation2019; Liburd et al., Citation2020). It can be defined as a co-generative and co-learning research and development endeavour (Liburd et al., Citation2017, p. 29). Tourism co-design contributes an innovative range of processes, methods and interventions enabling those involved to explore, with others sustainable tourism futures as spaces of possibilities (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018). Accordingly, the process of co-designing tourism is not merely concerned with leveraging specific outcomes inasmuch with the enabling collaborative processes among sometimes disparate groups with different backgrounds, knowledges, worldviews and potentialities in the becoming of new values, contexts and opportunities (Rogal & Sànchez, Citation2018). Critical for sustainable tourism development, Campos and Hall (Citation2019) find such collaborative and innovative spaces can legitimise those involved to question established rules and strategies while prompting organisational and institutional changes.

The increased application of vague ‘co’ prefixes in tourism studies require some conceptual clarification of tourism co-design. First, tourism co-design draws on collaboration, which unlike co-construction, coordination or cooperation, is recognised as entailing working towards shared goals from the premise that the sum of efforts is greater than what one in isolation, or by dividing the work, can accomplish (Huxham, Citation1996; Jamal & Getz, Citation1995). This implies a shift away from the historic division of labour and related efficiency gains and instead acknowledging the humanness of wicked global problems, which cannot be solved by a single individual, organisation or sector (Liburd, Citation2018). By co-designing tourism, new ideas, meanings, thinking, doings and, in turn, transformations of tourism practices may emerge within the ongoing relating and micro-detail of interactions among many people who collaborate (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018; Liburd et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the process of identifying emergent opportunities is empowered by the direct involvement of a range of participants and is driven by ongoing social interactions and power-relating as these participants learn, develop and evaluate ideas together, moving from experiment to experiment (Heape, Citation2015b; Heape et al., Citation2015). Tourism co-design thus differ from e.g. stakeholder and cluster analyses that seeks to sort, group and optimise various stakeholders or customer segments based on predefined criteria of similarities or differences often in a quest of gaining or maintaining competitive advantage. Instead, based on collaborative advantage (Huxham, Citation1996) the inclusive processes of co-designing tourism thrive on unfolding, exploring and interweaving a range of values, perspectives and worldviews of those involved to synthesise these into new opportunities for sustainable development.

Through the process of co-designing tourism, opportunities for novelty and learning surface through participants’ cultivation and exploration of variations of expression and interpretation when grasping something new as thematic patterns of meaning (Stacey, Citation2001), from which the known can be re-engaged as the unknown (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the current stabilising patterns of meaning may similarly be re-produced (Stacey, Citation2001), potentially reinforcing status quo. From this perspective, sustainable tourism futures may – or may not – be encouraged within tourism situations and their relational contexts. This contrasts with marketing-oriented service co-design, which sprung from the rise of a Service Dominant Logic and related notions of value co-creation (Lusch & Vargo, Citation2014). Service co-design is concerned with identifying user needs, which rest phenomenologically within individuals, to better users’ value-in-use perception of a service (Trischler et al., Citation2017). In a sustainability context, the premise of value being realised solely in-use ought to elicit at least some reflective precaution, considering the implications if, for example, nature can only hold value when used by humans. It is beyond the scope of this study to further discuss co-creation, suffice here to note that notions of co-creation can be critically opened up and viewed as a broad label for series of collaborative practices in tourism scholarship (see e.g. García-Rosell et al., Citation2019; Phi & Dredge, Citation2019).

Methodological positioning, methods and study setting

Given the proliferation of co-design approaches, it is worth positioning the study’s pragmatist understanding hereto. Dewey (Citation1938) re-conceptualised inquiry as taking a point of departure in revealing an indeterminate, unresolved and problematic current ‘situation’ and subsequently directing its transformation to bring forth a new resolved situation (p. 35). Notably, through reflective thought, learning and discoveries, new situations emerge, but there is no final settlement because any settling introduces the conditions of some degree of new unsettling. Correspondingly, a ‘tourism situation’ contains some irreducible societal troubles, tensions and uncertainties that are not embedded in theory but in the situated everyday doings and practices of tourism. From this perspective, the process of co-designing can be seen as a pattern of inquiry that begins with engaging tourism situations. Heape and Liburd (Citation2018) elaborated that in this regard, inquiry brings co-design processes, methods, tools and interventions into play to explore and expand the inquiry, where learning can be considered understanding in practice and being situated in that practice. Thus, this inquiry shaped according to arising tourism situations and values rather than being overtly dictated by theory or predefined methods, which could have limited the scope, complexity and values of the emerging opportunities the study sat out to engender. Far from a free-for-all, instead, it is a highly disciplined endeavour requiring constant, careful attunement to the processes of engaging with others to respond to and act upon the unfolding inquiry. Miettinen (Citation2000) argued that such reflective thought and action may both directly stimulate a reconstruction of the initial situation and indirectly generate intellectual outcomes (e.g. new meanings) that can be engaged as resources in forthcoming situations. The validity of inquiry, thus, rests within situations and the leveraging of re-constructions, ideas, meanings, understandings and potential actionable steps.

provides an overview of key events in the research process of co-designing what became known as ‘Our Mjøsa’ as the inquiry unfolded through five interlinked responsive stages. The following sub-sections explain this in detail focusing on the rich processual details of each of the stages and how these are interconnected tying into the becoming of this particular tourism co-design inquiry and ‘Our Mjøsa’.

Table 1. Overview of key events in the research process.

Stage 1: Embarking upon a shared inquiry

This study is part of a larger Norwegian research project, ‘Sustainable Experiences in Tourism’, spanning from 2018 to 2020 (Center for Tourism Research, Citation2018). The empirical materials stem from the author’s one-year-long (2018–2019) research engagement.

A project group of six researchers met regularly with a steering group of 11 local, regional and national public and private tourism practitioners to ensure linkages between research and everyday tourism practice. The project was initiated via an introductory kick-off workshop. To geographically represent the region, an additional 26 tourism practitioners, among a total of 50 invitees, participated. The project group provided details about the research and participants designed inputs to further guide the inquiry. Participants were divided into groups across organisational perspectives to discuss their expectations of research and sustainability issues. First, by individual considerations, then discussing as a group and, finally, they engaged plenum discussion. Transcripts from the workshop were thematically coded and summarised.

Stage 2: Collectively deciding upon the inquiry setting

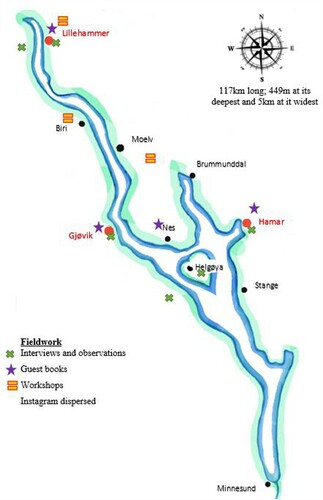

Discussing the themes from stage 1 with the steering group produced criteria for the study setting. Lake Mjøsa, the largest freshwater lake in Eastern Norway, was chosen as the context owing to its geographical location, rich heritage and potential for connecting a multiplicity of institutions, organisations and people through tourism co-design.

During the 1970s, the lake’s ecosystem suffered from malodorous, visible pollution resulting from decades of human impacts. Nearby forests had been cut, housing densified and farmland intensively cultivated. Meanwhile, fertilisation was causing emissions from agricultural and industrial activities and a lack of municipal sewage systems resulted in sewage being dumped directly into the lake. Mjøsa being a focal point for recreational activities, combined with the growing political interest in environmental sustainability, steered Gro Harlem Brundtland and the Ministry of Environment to mobilise two ‘Action for Mjøsa’ initiatives: ‘Little Actions for Mjøsa’ in 1970–1977 and ‘Big Actions for Mjøsa’ in 1977–1980. Here, Brundtland, who later chaired the WCED while creating the Our Common Future report, also advocated for environmental stewardship to preserve, protect and, in fact, save Mjøsa. Private businesses, organised housewives, public authorities and individuals collectively invested in practices to improve the ecological conditions. However, today, Mjøsa is challenged anew by invisible environmental threats, including climate change, which is spawning rising temperatures and sea levels, more flooding and glacial water, and new pollutants from products like shampoo and conditioner, micro-plastics and dangerously high mercury levels in the lake’s fish (Borgå et al., Citation2013; Fjeld et al., Citation2016; Larssen & Friberg, Citation2018). Lake Mjøsa connects two regions and 10 municipalities. In 2017, there were 1.5 million registered tourists’ nights-spent dispersed among the three ‘Mjøs cities’ of Lillehammer (54%), Gjøvik (16%) and Hamar (30%) (Statistikknett Reiseliv, Citation2018). A separate destination management organisation (DMO) located in each Mjøs city splits the lake itself. Each DMO is responsible for managing and marketing tourism within their own territorially defined destination, for which they receive public subsidies and membership fees.

To further plan and prepare the inquiry, a meeting was held with the DMOs to discuss potential methods and learn about tourism flows, and two fieldtrips were taken to form a first impression of this large area. illustrates the lake with indications of key methods used in co-designing ‘Our Mjøsa’, which are discussed below.

Stage 3: Experiencing Lake Mjøsa with others

To identify potential situations entailing issues and values to work from, it was imperative to gain context-specific information from diverse perspectives. Different qualitative and participatory methods were used for this. Subjective and value-laden narratives collected as different fragments of meaning could later be re-engaged in the co-design process to facilitate collective sense-making (Jaffari et al., Citation2011).

During the peak summer season, empirical materials were collected from interviews, observations and atmosphere photos in Gjøvik, Hamar and Lillehammer. Focused interviews are common means of generating subjective perspectives and detailed information regarding attitudes, opinions and values (Jennings, Citation2010). Specifically, the focused interviews addressed context-specific issues of memorable experiences and future concerns about tourism development. In all, 26 residents, 20 domestic tourists and 16 international tourists participated. Interviews lasting 2–40 min were recorded and transcribed.

Participant observation can reveal interactions and behaviours in real-world settings and allow for understanding how people construct and describe their worlds (Jennings, Citation2010) – in this case, how they meaningfully engage with Lake Mjøsa. Forty-four participant observations lasting between 30 min and several hours were conducted at central sites and attractions. They focused on points of interaction with others and with Lake Mjøsa. Notes were taken during these observations and were transcribed every evening. The interviews and observations were highly focused and bound to the Mjøs cities. Consequently, information was not gathered about what was happening in between-cities, where several camp sites, villages and harbours are located, potentially silencing alternate voices. To cover some of these blind spots and unraised voices, four mailboxes with guestbooks, coloured pens and candy were located at strategically dispersed viewpoints to encourage passers-by to contribute their impressions. About 179 people shared narratives. The guestbooks were checked weekly and a report was written with updates and reflections.

Keeping a fieldwork journal for continuously reflecting on the inquiry, including immediate impressions, ideas and reflections based on experiences of the lake from different cities with different residents and tourists, an initiating tourism situation began emerging. Mjøsa appeared to territorially divide rather than unite. Different tourism interests, priorities and dependencies surfaced among the Mjøs cities. Residents consistently expressed territorial-varying attitudes, usages and perceptions of Mjøsa. Moreover, they explained that except for one touristic paddle steamer, the many roads along the lake now replaced the earlier intensive boat traffic across Mjøsa. This meant that one’s nearest neighbours were no longer those living across the lake and that Mjøsa had become more of an obstacle between people. In response to this, and to further publicise the opportunity to participate in and influence the inquiry, an open invitation through Instagram using the hashtag #vårtmjøsa (read: #ourmjøsa) was intended to invite, engage and mobilise residents across the lake. Private and public practitioners from the steering group, DMOs, those involved in the earlier observations and those located at the camp sites and harbours assisted in encouraging residents and visitors to participate in ‘our shared exploration of Lake Mjøsa by posting a picture and inspiring others’, providing an alternative to social science’s reliance on verbalisations and affording opportunities for people to share their interpretations (Jennings, Citation2010, p. 191). More than 469 photos and narratives were shared. The open, inviting and unstructured nature of the guestbooks and Instagram facilitated a more nuanced understanding of heterogeneous locals and visitors and their everyday ways of engaging with the lake.

Stage 4: Collectively exploring and expanding ‘Our Mjøsa’

During autumn, two co-design workshops were facilitated to spark a collaborative identification of emergent opportunities and sense-making related to Lake Mjøsa tourism. Fifty practitioners, who had aided in earlier stages of the inquiry, were invited to the workshops, which were held at a conference centre. The practitioners represented smaller private tourism enterprises, such as camp sites; regional and national public and private representatives of the project and steering groups with a relation to the lake; residents belonging to grassroots organisations with a stake in the history, culture and nature of the area; and future tourism practitioners in the form of local BA tourism students considering Lake Mjøsa had become a cross-curricular case for the semester.

Beyond the project group and BA tourism students, 12 practitioners attended the first workshop, while 10 attended the second. Participants included representatives of three DMOs, private businesses, a region, a museum and an NGO and a few external researchers. Several participants highlighted the low participation of public municipalities as problematic, arguing that municipalities reinforce geographical divisions and promote tourism without grasping the inherent complexities and resources involved. Participants were divided into groups, ensuring that each one represented different organisational and territorial perspectives and interests. Fieldwork from stage 3 contributed in different ways to collective sense-making and to the cultivation and identification of emergent opportunities. The workshops, facilitated by the researchers, lasted between three and four hours and were documented in photos, notes, summaries, co-designed constructions and Post-its.

During the first workshop, participants enthusiastically welcomed the idea of potentially co-designing ‘Our Mjøsa’. They were asked to bring a photo demonstrating what Mjøsa means to them and present it to their group while reflecting on their dreams, hopes and aspirations for the area’s future. Meanwhile, others listened and noted on Post-its whatever caught their attention. Subsequently, participants negotiated different themes and assigned headlines. Building from this shared identification with Mjøsa, each participant received 10 fieldwork fragments that were re-written as narratives of concerns, memorable experiences and pictures and guestbook contributions to add nuance and complexity to the inquiry. Participants took 10 min to interpret some preliminary meaning before introducing it to the group. Subsequently, they explored new connections and meanings arising between themselves and the narratives, which they wrote down on a poster. Lastly, everyone assembled to discuss their findings.

To set the scene for the second workshop, groups’ Post-its, presentations, notes and posters were cross-analysed for emergent themes using two inclusive principles: (1) all participants had to be represented and (2) as far as possible, their own words had to be used. As such, the emergent themes identified were rooted within the tourism practice and those involved rather than being overtly guided by theory or researchers. In the second workshop, the above cross-thematised findings were discussed with participants to form the basis for co-designing new conceptualisations to support ‘Our Mjøsa’. Participants were asked to summarize their observation in five bullet points along with five atmosphere pictures with ‘strange questions’ below them, such as a picture of a duck with a question on its perspective on tourism. Groups collectively expressed their conceptualisations on a printed map of the lake. Each group’s Post-its, presentations, notes and posters were subsequently summarised.

Stage 5: Passing ‘Our Mjøsa’ forward

After the workshops, several individual conversations and group meetings with participants took place to sum up and critically reflect on the process of co-designing ‘Our Mjøsa’ going forward. Preliminary findings were presented at a national conference held locally with one of the participants (smaller private business owner), who did his own co-design experiment with the audience. Practitioners shared how a wealth of potentialities had become perceptible by co-designing tourism, though tangible operationalisations are still to be realised. DMOs and the project group discussed a collective ‘What’s next?’ event, which was never carried out. This is further reflected and elaborated upon later.

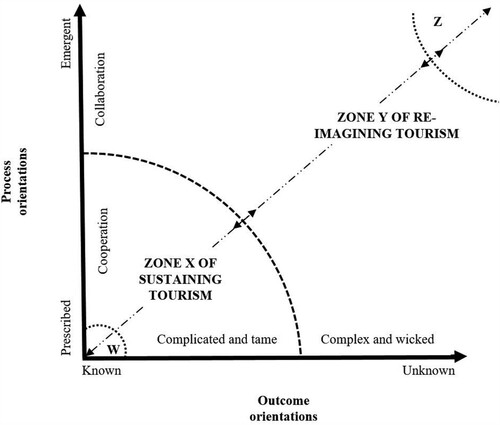

The fifth stage also includes the writing of this article. In that regard, the empirical materials belong to two strings. First, they concern the systematic thematising of participants’ co-designed outcomes and conceptualisations, which, as described, were performed and discussed with participants in each of the above stages. Second, the empirical materials cover the documented processes of tourism co-designing ‘Our Mjøsa’, which allowed for an in-depth analysis of detailed micro-structures of participants’ interactions (Basten, Citation2011) to grasp the processes through which opportunities may emerge. Accordingly, to understand the variations in participants’ outcomes and their related processes, an abductive process of interpretation was deployed, shifting back and forth between the (re)exploration of key theoretical concepts and the two strings of empirical materials. Based on multiple iterative rounds of reinterpretation, four distinct dialectic zones emerged which collectively comprise a framework for understanding how sustainable tourism futures may emerge and can be encouraged by means of co-designing tourism ().

What follows is a discussion of some of the descriptive narratives and tourism co-design situations as they unfolded. These are supplemented with other examples to nuance the dynamics of the framework. Narratives and situations were selected for their ability to leverage an understanding of how opportunities for sustainable tourism futures did and did not emerge.

Findings and discussion

Although did not arise before multiple iterative rounds of reinterpretation, in the following it serves as a logical structure to present and discuss the findings of this study. Drawing on the key concepts and assumptions of sustainable tourism development, the framework horizontally works from sustainable tourism development as a predetermined, known goal towards unknown outcomes. Vertically, the framework stretches from sustainable tourism development as prescribed processes towards the engenderment of an emergent becoming. The figure depicts four zones that surfaced in response to the empirical co-designing of sustainable tourism futures for Lake Mjøsa.

These are zone X of sustaining tourism; zone Y of re-imagining tourism; and two zones of inertia marked with W and Z. The remainder of the paper first unfolds the distinct characteristics of each zone and then the dynamic interrelations as illustrated by arrows and dotted lines. Before proceeding to the findings of the study, few clarifying points must be made. Findings are not tied to specific stages of inquiry or to one specific person or group. Instead, findings denote how sustainable tourism development is encouraged (or not) within and between four zones focusing on the micro-structures of interaction. By further exploring and discussing these, it is possible to reveal and make transparent the implicit and explicit assumptions on which the four different encouragements of sustainable tourism development are built.

Zones of inertia

First, relating to zone W, as mentioned, several significant practitioners did not participate and a few declared beforehand that they would ‘observe’ rather than engage in co-designing. The following conversational snippets demonstrate how a group of heterogeneous participants discussed issues of sustainability within their situated tourism contexts during the kick-off workshop (stage 1):

For me, sustainability relates to certificates that simultaneously heighten the competitive advantage, the brand and the rate of returning tourists. (DMO)

Sustainability is the operationalisation of the social, the environmental and the economic through residents. (business)

I agree, it is social, environmental and economic. I think there is also a special focus on ethics, as with the rising practices of eco-certificates. We must consider ways of generating economic returns while simultaneously preserving the area. (network organisation)

Yes, it is social, environmental and economic, and then one could add that thing with future generations. (region)

Within this zone, tourism sustainability explorations were collectively reduced to the triple bottom line approach of sorting and positively balancing ecological, socio-cultural and economic elements. Relatedly, some perceived tourism sustainability as a question of obtaining more certificates and labels that can serve as ‘a sort of recipe’ while ensuring balance. These would then provide clear criteria to sort the sustainable and unsustainable tourism practices according to a set of social, economic and environmental criteria. Yet, such a balanced approach to tourism sustainability may, in principle, aid a business-as-usual as the concealed exploitation of areas for growth. The balanced approach, thus, reduced sustainable tourism futures to an assumed and already prescribed known, where it appeared that there was no need to re-imagine alternatives, potentially disturbing that balance. Sustainability within this zone, also appeared as an unquestionable, correct theoretical construct to which one could add something about ‘ethics’ or ‘future generations’ – issues that are hardly questionable or easily operationalised in everyday tourism practices.

Second, zone Z can be characterised by similar outcomes of inertia, though the processes leading hereto are far from the overtly reductionist approaches exemplifying zone W. During the plenum presentations and discussions following the kick-off workshop (stage 1), another group including a DMO, a local researcher, a public practitioner and a private practitioner described the following:

Sustainability is a sort of ‘all or nothing’ construct, and it is very difficult to relate to something or someone. There is clearly a lack of someone – people, locals – taking ownership of its operationalisation.

Tourism within the marked zones of inertia (i.e. W and Z) demonstrates two opposing encouragements of sustainable development, though characterised by similar outcomes of inertia, inaction, passivity, or stillness. These zones are vital to acknowledge because it is often assumed that change is easily attainable or desirable (Fennell, Citation2018). The zones demonstrate some of the difficulties related to engendering alternative ways of imagining and doing tourism for sustainable development. First, by avoiding questioning and disturbing current tourism practices and potentially varying values, sustainability is easily reduced to an assumed or obtained balance, which can lead to passive acceptance of the current state of affairs. Second, the zones underscore the historic top-down focus on macro-level issues concerning the objectives of sustainable development and how these convey a lack of operationalisation (Butler, Citation1998; Sharpley, Citation2000, Citation2020). Following the lack of identification with the task of sustainable development as it is defined by others such as the UN or textbooks and applied onto tourism practice, sustainable tourism futures appear to be external to situated everyday tourism doings. Bringing together these often silenced and unnoticed nuances of a sustainable tourism development process, it is within these zones we overlook or do not engage the situations, practices and values of those affected by tourism, which otherwise could spur opportunities for sustainable development transition processes.

Zone of sustaining tourism

First, related to zone X of sustaining tourism, one person argued, ‘This one definitely does not get the point with Mjøsa’. Another concluded, ‘This group did not feel welcome, but it cannot have been at my place’. They became defensive, interpreting and discarding design materials as potential critiques of them. The following narrative (stage 4, workshop 2) is from a group’s plenum presentation:

We struggled a lot because there really are a lot of very strange inputs. It appears there is something particular with love. This includes a range of stories spanning from people who meet and fall in love, proposals, celebration of anniversaries but also the historic country romance and symphonies of smells and sights. But we cannot focus on such [odd] small things, right?

Tourism within zone X is assumed to be manageable by following or directing prescribed processes for sustainable development and working towards them as more or less known goals. As with many traditional models, tourism is assumed to be complicated (Hall et al., Citation2018), where the sum of its parts can be discerned and re-combined in a cooperative (Huxham, Citation1996) manner. Consider, for instance, the suggestions of a new boat tour between the three Mjøs cities, electric bicycle rentals at different sites or a shared booking-and-information website. These complicated and cooperative encouragements of tourism could equally be achieved by one party (e.g. investing in electric bikes) or by splitting the work (e.g. each participant has a bike charging station at a different location). This is not to say that these are not emergent innovative opportunities, but tourism is encouraged within a rather risk-free safe space at least according to its commonly held assumptions.

Second, during the plenum presentations (stage 4, workshop 2), several participants rationalised commodifying ‘Our Mjøsa’. The following are a few snippets:

We must make it [Mjøsa] a product, package it and sell it to tourists. (region)

Tourists must be fed the history with a spoon. (business)

It is important that we build a brand and sell Mjøsa as one concept. (DMO)

Encouragements of sustainable tourism development within the zone of sustaining tourism, thus, will likely result in more of the same and will unlikely facilitate significant sustainability transitions. Though some innovations can be nurtured, they appear tourism-centric and heavily focused on economic outcomes and competitive advantages (Hunter, Citation1995, Citation1997). Consequently, they sustain little more than the tourism practice itself as an isolated phenomenon rather than one that is interconnected with sustainable development.

Zone of re-imagining tourism

Zone Y of re-imagining tourism is now unfolded through four interlinked dynamics. First, in conceptualising ‘Our Mjøsa’ (stage 4, workshop 2), a group discovered that the owner of a private outdoor enterprise enjoyed playing PlayStation; a DMO representative had himself been involved in a regional augmented reality initiative; and a leader of a tourism network had participated in a Dutch ‘Pick three things [trash]’ initiative. By interweaving their different backgrounds and experiences, they described the following in plenum:

We propose concepts of caring for Mjøsa which foster pride and unite us, potentially using available technology but bridging it with our mind-set and ideologies, so we can engage locals and tourists, for example, in picking up trash. Moreover, we can combine such initiatives with local discounts, where money is re-directed to sustain nature and improve water quality.

Second, within one group, participants (stage 4, workshop 1) initially stalled and were unable to make sense of the materials before them. A business owner broke the silence and steered the conversation as follows:

There are multiple ‘complaints’ [sigh]: too little information, violation of rules, stinky water, having difficulties finding one’s way around, not feeling welcome …

I noticed you just changed your tone while talking. Did that mean something? (author)

I don’t know … I think maybe these points of negativity are different. (business)

Well, they all present very dissimilar challenges and likely require us to approach them differently. (business)

But what if these are our greatest challenges, and what if we shift all this and instead say it is an opportunity that we all share concerns for the area?

Are all smells bad? (external researcher)

Can we replace do-not-disturb signs with smiles? (student)

Is it enough to hang up a shovel at a museum? (DMO)

The above nuances suggest that unlike immediate and salient outcomes within the zone of sustaining tourism (e.g. bicycles), this zone is characterised by an engagement of ambiguities and nuances of sustainable tourism futures as a highly situated endeavour where no one resolution applies. By re-imagining and challenging current tourism assumptions, the unknown became known and vice-versa, stimulating possibilities for empowering ‘Our Mjøsa’ as an emergent process of becoming with others and Mjøsa.

Third, personal narratives varied when participants presented individual pictures of Mjøsa’s meaning to them (stage 4, workshop 2). Mjøsa was described as ‘boring’ (student), a site of ‘potential collective mobilisation’ (DMO), something ‘I don’t use much’ (external researcher and resident), ‘a feeling of being close to Mjøsa’ (business) and ‘within a continuous state of becoming’ (business). Moreover, a participant from a voluntary nature organisation noticed the variations of expressions concerning whether they as practitioners ‘consume’, ‘use’ or ‘experience’ Mjøsa. Accordingly, tourism co-design leveraged a rich variation of interpretations and expressions (Stacey, Citation2001) from which different understandings of Mjøsa were disclosed and gradually interwove new patterns of meaning or understanding of what ‘Our Mjøsa’ may become. Through intentional explorations of these variations, groups were able to cultivate a shared identification, ownership and motivation for considering something as ‘Our Mjøsa’ in the first place. Numerous participants came to phrase it during the plenum presentations (stage 4, workshop 2), for example, as ‘this is our dream’, ‘why we try’, ‘the driving force’ and ‘a shared motivation behind Mjøsa and tourism’. Moreover, several reflected as follows afterwards (stage 5):

There is more to the story than my story. (business)

We tend to think a lot about each other and about tourists; that was definitely something that changed … We literally sat around a table and looked each other in the eyes. Here [when tourism co-designing], it did not matter who had the most money or the loudest voice. (business)

Through shifts in power-relating (Heape et al., Citation2015), the participation of diverse practitioners empowered alternative voices and perspectives to partake in re-constructions of meaning (Bramwell, Citation2010). Consequently, a new shared understanding and context surfaced, driven by ideological diversity and synthesis of diverse values, knowledges and worldviews related to Lake Mjøsa (Hall, Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2018; Rogal & Sànchez, Citation2018).

Fourth, groups (stage 4, workshop 2) identified opportunities including, but not limited to, addressing complex wicked issues of nature- and heritage-conservation, climate change, biodiversity loss, trash, pollution, algae toxins and inclusion of the disabled and elderly. Within this zone, it is possible to engage sustainable tourism development as spaces of possibilities and engage the known as the unknown (Campos & Hall, Citation2019; Heape & Liburd, Citation2018). Correspondingly, it is possible to re-imagine the assumptions of tourism from those of sustaining tourism to sustaining that which we value through tourism. In view of this, a group metaphorically phrased how socio-culturally ‘we give life to Mjøsa’ and participants envisioned and identified several other-regarding innovations (Liburd, Citation2018) by re-imagining tourism’s contribution to value-laden issues of sustaining what, how and with whom. Processually, this represents a collaborative endeavour that is not solely tied up with individual interests and agendas nor motivated by a quest for competitive advantage but, rather, is rooted in collaborative advantage and other-regarding ethics and values of care (Fennell, Citation2019; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014). This entails seeking to sustain that which we value through tourism development with others – that is, ‘what is yours and mine together as our sustainable tourism futures’.

Dynamic interlinkages

The above zones exhibit some of the nuances and dynamics associated with co-designing tourism with others. However, as illustrated by the arrows and dotted lines in , these zones are not static but dynamic and interconnected. Participants’ apprehension and exploration of related tourism situations containing irreducible complexities, paradoxes and ambiguities that are otherwise hidden or overlooked expanded the inquiry. It is within these arising microstructures of interactions (Basten, Citation2011) that we may challenge the current tourism assumptions, flip our thinking and devise new responses to, and understandings of, tourism for sustainable development. Participants elaborated multiple issues; for instance, they are rarely familiar with the neighbouring businesses and, as a private business owner explained, a ‘“kings in each their own garden” attitude prevails … afraid of losing something by collaborating and afraid that others will reap the benefits’. Accordingly, the cooperative nature characterising zone X of sustaining current tourism practices began to reveal itself as a constraint to zone Y of re-imagining tourism, when noticing how a sustaining of tourism practice for itself will likely stimulate continued competition for tourists and resources (McKercher, Citation1993). A private practitioner responded to this on behalf of his group in plenum (stage 4, workshop 2):

We have become committed to breaking down the barriers of ‘us’ and ‘them’ to create something that is ‘our’ … We are too small if we each stand isolated; we need to talk about ‘our’ and not ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Despite changing governance structures and more comprehensive reports urging stakeholders to pursue specific goals and targets to achieve sustainable outcomes (Fennell & Cooper, Citation2020; Hall, Citation2008), tourism is largely still deeply rooted in, or at worst locked into, the assumptions underpinning the zones of inertia and sustaining tourism. Therefore, the rise of new collaborative philosophies applied to tourism is noteworthy, even if this study demonstrates through the identified zones of inertia and sustaining tourism that they do not automatically lend themselves to transforming tourism. Nonetheless, the innovative range of processes, methods, interventions and, notably, an attitude of mind (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018, p. 238) afforded by tourism co-design can enhance practitioners’ mindfulness and enable them to re-imagine what tourism may be for, moving beyond the zones of inertia and sustaining tourism itself. Specifically, within the zone of re-imagination, this study illuminates at least four vital co-design dynamics that allow for moving beyond zones of inertia and sustaining tourism to re-imagine tourism.

Small, doable steps of mindfulness and care

Despite the contingencies and situatedness of any tourism co-design endeavour and related outcomes, the encouragement of tourism emerging within zones of inertia and sustaining tourism calls for critical self-reflection. Further, this might have been heightened due to some shifts in participants and sometimes-minimal facilitation and instruction causing participants to sometimes talk all at once, feel insecure about what to do or simply stall and check their phones rather than engaging and interacting with each other.

The many new opportunities identified as tangible new initiatives and outcomes of the overall re-construction of ‘Our Mjøsa’ are still to operationalise. In hindsight, covering several hundred kilometres of area combined with practitioners who may be unfamiliar with neighbouring businesses even in close proximity might have been overly ambitious. Despite the ongoing philosophy of engaging with others, some of the shortcomings of passing ‘Our Mjøsa’ forth suggest further shifts towards engagement by others to facilitate greater levels of ownership. Moreover, the reliance on researchers and larger practitioners (the DMOs, stage 5) to aid this passing forth through the cancelled ‘What’s next?’ event likely could have been enhanced by working specifically with the fiery smaller businesses and grassroots.

Yet a range of more intangible and indirect outcomes transpired, as outlined above, of which some are engaged, and others may serve as resources for forthcoming situations (Miettinen, Citation2000). In light of territorial-varying interests, priorities and perceptions, the re-construction of ‘Our Mjøsa’ enabled disparate practitioners and groups to identify and envision shared values and desirable tourism futures. The potentialities leveraged by the wide range of new ideas, new meanings, new thinking and new doings (Heape, Citation2015a; Larsen & Sproedt, Citation2013) brought about a mindful awareness of the inherent complexities, unknowns, hidden dilemmas and paradoxes in working with sustainable tourism development. Some practitioners are planning or are already doing co-design experiments with others. A representative of a network organisation metaphorically shared how co-designing had ‘opened her eyes’ to the fact that they had been looking at Mjøsa only from one angle, ‘but so many more angles exist’, which she and her network were now exploring. All this adds to Gössling et al.’s (Citation2012) conclusion that change is more likely to occur via doable incremental steps rather than large-scale rupturing systemic change; and this study adds of becoming mindful and caring with others.

Conclusion

This study critically challenged the management-oriented rationale of developing tourism for others. It recognised that tourism approaches and research have evolved from the development of communities to development in communities and with communities of practice (Cockburn-Wootten et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2008) and contributed to the emergent field and practice of collaboratively designing tourism with others. The study thus added to the broader values and ethics of sustainable tourism development where a democratisation of tourism research is vital to drive the needed paradigmatic shift (Fennell, Citation2019; Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014). Specifically it was argued and demonstrated how collaborative spaces driven by a pluralisation and interweaving of the values, norms, ideologies, knowledges and worldviews of those affected by tourism can create traction for sustainable development (Campos & Hall, Citation2019; Gössling et al., Citation2012; Hall, Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2018 Jamal & Getz, Citation1995, Citation1999; Liburd, Citation2018).

Based on a Norwegian inquiry of collaboratively designing ‘Our Mjøsa’ with a broad range of practitioners, the study engaged a range of processes, methods, tools and interventions, enabling those involved to explore with others sustainable tourism futures as spaces of possibilities (Heape & Liburd, Citation2018; Liburd et al., Citation2017; Rogal & Sànchez, Citation2018). The main contribution of this research lies in the proposed framework for understanding how sustainable tourism futures may emerge and can be encouraged by means of co-designing tourism. The findings of analysis revealed four dynamic zones comprising the framework – two zones of inertia, one of sustaining tourism and one of re-imagining tourism. Through exploration and discussion of the identified zones, this study suggests that co-designing tourism can enable its practitioners to engage in disciplined collaboration and creativity while envisioning, cultivating and identifying emergent opportunities for re-imagining sustainable tourism futures and other-regarding innovations (Liburd, Citation2018). By further nuancing this positioning, the study demonstrates that there is no magic bullet list for co-designing tourism. Instead, as a highly complex social endeavour, we will likely experience tempo-spatial and continuous shifts and flows among the zones of inertia, sustaining tourism and re-imagining tourism. Importantly, these shifts and flows accentuate that tourism must not be stuck within zones of inertia or sustaining tourism. Instead, it is within these ongoing shifts and flows that it becomes possible to simultaneously reveal and make more transparent the implicit and explicit assumptions underpinning current tourism practice while re-imagining mindful sustainable tourism futures. Thus, the framework can be used for interrogating the assumptions behind, and implications of, particular approaches to sustainable tourism development. Findings suggest that tourism is yet to cultivate a greater awareness of the values and complexities of sustainable development and of the diversity of individuals implicated in.

As the study was limited to one territorial lake context, the findings do not directly apply to other contexts, as each place inevitably has its own particularities and values. The study did not sufficiently address the power relations or positionalities of stakeholders (e.g. Tribe & Liburd, Citation2016). Neither did the study holistically consider potential conflicting cross-scale issues related to outcomes within a wider frame (Hall et al., Citation2018). Such understanding and exploration of ways to further support alternative ways of facilitating sustainability transitions with others are needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eva Duedahl

Eva Duedahl is a Ph.D. Fellow at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Business and Social Sciences. Eva’s research focuses on collaborative design of tourism in relation to sustainable development transitions.

References

- Aall, C. (2014). Sustainable tourism in practice: Promoting or perverting the quest for a sustainable development? Sustainability, 6(5), 2562–2583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su6052562

- Basten, F. (2011, January 13–15). Microstructures as spaces for participatory innovation. Participatory innovation conference (pp. 130–136), Sønderborg: University of Southern Denmark.

- Boluk, K., Cavaliere, C., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations sustainable development goals 2030 agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Borgå, K., Fjeld, E., Kierkegaard, A., & McLachlan, M. S. (2013). Consistency in trophic magnification factors of cyclic methyl siloxanes in pelagic freshwater food webs leading to brown trout. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(24), 14394–14402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1021/es404374j

- Bramwell, B. (2010). Participative planning and governance for sustainable tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081640

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (1993). Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589309450696

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 411–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

- Bratteteig, T., Bødker, K., Dittrich, Y., Mogensen, P. H., & Simonsen, J. (2012). Methods: Organising principles and general guidelines for participatory design projects. In J. Simonsen, & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 117–144). Routledge.

- Bricker, K. (2018). Positioning sustainable tourism: Humble placement of a complex enterprise. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 36(1), 205–211.

- Buckley, R. (2012). Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 528–546. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.003

- Butler, R. W. (1998). Sustainable tourism: Looking backwards in order to progress? In C. M. Hall, & A. Lew (Eds.), Sustainable tourism: A geographical perspective (pp. 25–34). Addison Wesley Longman.

- Butler, R. W. (1999). Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tourism Geographies, 1(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616689908721291

- Buur, J., & Larsen, H. (2010). The quality of conversations in participatory innovation. CoDesign, 6(3), 121–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2010.533185

- Campos, Z., & Hall, C. M. (2019). Transformative collaboration: Knocking down taboos, challenging normative associations. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 11(1), s13–s18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1556857

- Center for Tourism Research. (2018). About BOR. https://www.reiselivsforskning.org/forside/bor/.

- Cockburn-Wootten, C., McIntosh, A. J., Smith, K., & Jefferies, S. (2018). Communicating across tourism silos for inclusive sustainable partnerships. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(9), 1483–1498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1476519

- Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: The theory of inquiry. Henri Holt and Company.

- Duedahl, E., & Liburd, J. (2019). Bridging the gap: Co-design for sustainable tourism development education. In J. Pearce (Ed.), Think tank proceedings of BEST EN think tank XIX: Creating sustainable tourism experiences (pp. 34–37). James Cook University.

- Fennell, D. (2018). Tourism ethics (2nd ed.). Channel View Publications.

- Fennell, D. A. (2019). Sustainability ethics in tourism: The imperative next imperative. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1548090

- Fennell, D., & Cooper, C. (2020). Sustainable tourism: Principles, contexts and practices. Channel View Publications.

- Fjeld, E., Bæk, K., Rognerud, S., Rundberget, J. T., Schlabach, M., & Warner, N. A. (2016). Environmental pollutants in large Norwegian lakes. Norwegian Institute for Water Research. Retrieved May 16, 2019, from https://www.niva.no/en/reports/environmental-pollutants-in-large-norwegian-lakes

- García-Rosell, J.-C., Haanpää, M., & Janhunen, J. (2019). ‘Dig where you stand’: Values-based co-creation through improvisation. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(3), 348–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1591780

- Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., Ekström, F., Engeset, A. B., & Aall, C. (2012). Transition management: A tool for implementing sustainable tourism scenarios? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(6), 899–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.699062

- Gössling, S., Hall, M., & Weaver, D. (2009). Sustainable tourism futures: Perspectives on systems, restructuring and innovations. In S. Gössling, M. Hall, & D. Weaver (Eds.), Sustainable tourism futures: Perspectives on systems, restructuring and innovations (pp. 1–15). Routledge.

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships (2nd ed.). Pearson Education UK.

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Hall, C. M., Gössling, S., & Scott, D. (2015). The evolution of sustainable development and sustainable tourism. In C. M. Hall, S. Gössling, & D. Scott (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism and sustainability (pp. 15–35). Routledge.

- Hall, C. M., & Lew, A. (1998). The geography of sustainable tourism development: An introduction. In C. M. Hall, & A. Lew (Eds.), Sustainable tourism: A geographical perspective (pp. 1–12). Addison Wesley Longman.

- Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2018). Tourism and resilience: Individual, organisational and destination perspectives (5th ed). Channel View Publications.

- Hardy, A., Beeton, R. J. S., & Pearson, L. (2002). Sustainable tourism: An overview of the concept and its position in relation to conceptualisations of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(6), 475–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667183

- Heape, C. (2015a, May 18). Doing design practice: Design inquiry as an improvised temporal unfolding. In R. Valkenburg, C. Dekkers, & J. Sluijs (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th Partipatory conference (pp. 184–191). The Hague.

- Heape, C. (2015b, June 28). Today’s students, tomorrow’s practitioners. In R. V. Zande, E. Bohemia, & L. Digranes (Eds.), Learnxdesign proceedings of the 3rd international conference for design education researchers (pp. 1362–1380). Alto University.

- Heape, C., Larsen, H., & Revsbæk, L. (2015, August 17–21). Participation as taking part in an improvised temporal unfolding. In O. W. Bertelsen, K. Halskow, S. Bardzell, & O. Iversen (Eds.), The 5th decennial aarhus conference: Critical alternatives (pp. 1–6). Aarhus University Press.

- Heape, C., & Liburd, J. (2018). Collaborative learning for sustainable tourism development. In J. Liburd, & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collaboration for sustainable tourism development (pp. 226–243). Goodfellow Publishers.

- Higham, J., & Miller, G. (2018). Transforming societies and transforming tourism: Sustainable tourism in times of change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1407519

- Hughes, M., & Morrison-Saunders, A. (2018). Whose needs and what is to be sustained? In J. Liburd, & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collaboration for sustainable tourism development (pp. 244–268). Goodfellow Publishers Ltd.

- Hunter, C. (1995). On the need to re-conceptualise sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 3(3), 155–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589509510720

- Hunter, C. (1997). Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 850–867. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00036-4

- Huxham, C. (1996). Collaboration and collaborative advantage. In C. Huxham (Ed.), Creating collaborative advantage (pp. 1–18). SAGE Publications.

- Jaffari, S., Boer, L., & Buur, J. (2011, July 19–22). Actionable ethnography in participatory innovation: A case study. Proceedings of the 15th world multi-conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (pp. 100–106). International Institute of Informatics and Systemics (IIIS), USA.

- Jamal, T., & Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

- Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1999). Community roundtables for tourism-related conflicts: The dialectics of consensus and process structures. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7(3-4), 290–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589908667341

- Jennings, G. (2010). Tourism research (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd.

- Larssen, T., & Friberg, N. (2018). Effects of climate change, climate measures, climate adaption, long-term data series, modelling, large scale experiments. Norwegian Institute for Water Research. Retrieved May 16, 2019, from https://www.niva.no/en/services/effects-of-climate-change

- Larsen, H., & Sproedt, H. (2013, September 8–11). Researching and teaching innovation practice. [Paper presentation]. The 14th international cinet conference: Business development and co-creation, Nijmegen, Netherlands.

- Liburd, J. (2018). Understanding collaboration and sustainable tourism development. In J. Liburd, & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collaboration for sustainable tourism development (pp. 8–35). Goodfellow Publishers.

- Liburd, J., Duedahl, E., & Heape, C. (2020, forthcoming). Co-designing tourism for sustainable development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism [Manuscript in review for special issue on tourism and partnerships for the SDGs].

- Liburd, J., & Edwards, D. (2010). Understanding the sustainable development of tourism. Goodfellow Publishers Limited.

- Liburd, J., Nielsen, T., & Heape, C. (2017). Co-Designing Smart Tourism. European Journal of Tourism Research, 17, 28–42. Retrieved from https://ejtr.vumk.eu/index.php/about/article/view/292

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2014). Service-dominant logic: Premises, perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

- McDonald, J. R. (2009). Complexity science: An alternative world view for understanding sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(4), 455–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802495709

- McKercher, B. (1993). Some fundamental truths about tourism: Understanding tourism's social and environmental impacts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589309450697

- Miettinen, R. (2000). The concept of experiential learning and John Dewey’s theory of reflective thought and action. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/026013700293458

- Miller, G., & Twining-Ward, L. (2005). Monitoring for a sustainable tourism transition: The challenge of developing and using indicators. CABI Publishing.

- Moscardo, G. (2011). Exploring social representations of tourism planning: Issues for governance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 423–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.558625

- Phi, G. T., & Dredge, D. (2019). Collaborative tourism-making: An interdisciplinary review of co-creation and a future research agenda. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(3), 284–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1640491

- Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Robertson, T., & Simonsen, J. (2012). Participatory design: An introduction. In J. Simonsen, & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Rogal, M., & Sànchez, R. (2018). Codesigning for development. In R. B. Egenhoefer (Ed.), Routledge handbook of sustainable design (pp. 250–262). Routledge.

- Rutty, M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2015). The global effects and impacts of tourism: An overview. In C. M. Hall, S. Gössling, & D. Scott (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism and sustainability (pp. 36–63). Routledge.

- Sharpley, R. (2000). Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580008667346

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1932–1946. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1779732

- Stacey, R. (2001). Complex responsive processes in organizations: Learning and knowledge creation. Routledge.

- Statitistikknett Reiseliv. (2018, May 5). Kommersielle gjestedøgn i Mjøsaregionen. [Commercial guest nights in the Mjøsa region]. www.statistikknett.no.

- Tribe, J., & Liburd, J. J. (2016). The tourism knowledge system. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 44–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.011

- Trischler, J., Pervan, S. J., Kelly, S. J., & Scott, D. R. (2017). The value of codesign: The effect of customer involvement in service design teams. Journal of Service Research, 21(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517714060

- United Nations. (2016). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

- Wall, G. (2018). Beyond sustainable development. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(3), 390–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1475880

- Weaver, D. (2009). Reflections on sustainable tourism and paradigm change. In S. Gössling, M. Hall, & D. Weaver (Eds.), Sustainable tourism futures: Perspectives on systems, restructuring and innovations (pp. 33–40). Routledge.

- Whitham, R., Moreton, S., Bowen, S., Speed, C., & Durrant, A. (2019). Understanding, capturing, and assessing value in collaborative design research. CoDesign, 15(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1563194

- World Commission of Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.

- World Tourism Organization and United Nations Development Programme. (2017). Tourism and the sustainable development goals – journey to 2030. UNWTO.