ABSTRACT

The emergence of social media has revolutionized tourists’ decision-making processes and behaviours. This study focuses on the effect of user-generated content (UGC) on tourist loyalty behaviour by examining structural relationships between destination image, satisfaction, revisit intention, and word-of-mouth (WOM) publicity. Data were collected from domestic tourists to Gulangyu, a World Heritage Site in China. The findings of this study reveal that UGC indirectly affects tourist loyalty behaviour by influencing destination image and satisfaction. Moreover, the results demonstrate that factual UGC and emotional UGC positively affect tourists’ perceived value of the destination, with emotional UGC having a greater influence.

Introduction

Traditionally, research into tourist destination loyalty focused on how the destination relates to tourists and establishes a lasting relationship (Akhoondnejad, Citation2016; Keshavarz & Jamshidi, Citation2018). With the advent of social media, retaining tourist-destination relationships can no longer be achieved by simply creating a better product or service. Growth of internet user-generated content (UGC) has effected a major change in the flow of information that has permeated and influenced consumer behaviour in the tourism and hospitality sectors (Kim & Kim, Citation2020; Leung et al., Citation2013).

One of the major trends in the tourism industry is that individual travellers increasingly rely on UGC to make travel decisions (Amatulli et al., Citation2019; Oliveira & Casais, Citation2019),thus the entire tourist decision-making process, pre-travel, during travel and post-travel (Nezakati et al., Citation2015), is extensively influenced by UGC. At the pre-travel stage, UGC is a source of information for tourists to review travel products and destinations, create expectations (Wang et al., Citation2016), develop travel plans (Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010) and assist in making travel decisions. During the trip, UGC enables tourists to evaluate tourism products and services. At the post-evaluation stage, some studies have explored the impacts of UGC on tourist satisfaction (Narangajavana et al., Citation2019). In this respect, UGC on social media can help to minimize the gap between experience and expectations, thereby indirectly increasing tourist satisfaction (Narangajavana et al., Citation2017). Thus, understanding how travellers have adapted to these changes and established their loyalty relationships becomes important for tourism marketers to improve destination competitiveness and develop effective communication strategies.

While UGC can enhance favourable tourist experience and lead to desirable behavioural intentions (Narangajavana et al., Citation2017; Narangajavana et al., Citation2019), the influence of UGC usage at the pre-travel stage on destination loyalty lacks empirical attention. Some studies have used content-analysis of travel websites to access tourist perceptions and satisfaction of a tourism destination (Költringer & Dickinger, Citation2015; Tham et al., Citation2013), but these studies did not interview actual tourists and so were unable to examine the causal relationship between UGC impacts, tourist destination image, satisfaction and loyalty behavioural intention. Another group of researchers has examined the impacts of online information on consumer loyalty behaviour, such as online repurchase intention (Bulut & Karabulut, Citation2018; Matute et al., Citation2016) and intention to revisit (Setiawan et al., Citation2014). These studies have contributed valuable points to our understanding of the influence of online information as a whole in tourist behaviour. However, when UGC are used by tourists in the travel plan, different types of UGC convey different destination attributes to tourists in different ways. Specifically, UGC not only provides tourists with basic factual information about travel products and destinations, increasing tourist knowledge about a destination; but the travel photographs or videos shared on social media can also affect a tourists’ emotion towards a destination. This raises the question as to the effect that different types of UGC have on tourist’s loyalty behaviour. The degree of influence of different types of UGC on destination loyalty formation is not at all clear.

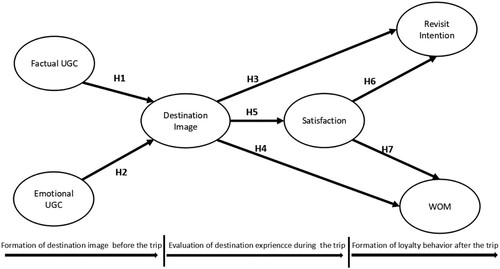

This study aims to fill these research gaps by empirically investigating how UGC influences tourist loyalties, identifying the different types of UGC and exploring their influence on tourist behaviour. The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) to develop a predictive model (see ) of how UGC affects tourist perceptions of destination, satisfaction, revisit intention and the likelihood of recommending a product or service to others (word-of-mouth) (WOM); (2) to empirically test the validity of the predictive model; (3) to distinguish the relative influence on tourists of two types of UGC: factual information and emotional information.

The World Heritage Site of Gulangyu, a well-known heritage tourism destination in southeast China, is used as a case study to provide empirical evidence to elucidate the role of UGC in enhancing tourist satisfaction and tourist destination loyalty. This study contributes to tourism literature by exploring how the different types of UGC in social media trigger desired behavioural responses of Chinese visitors to a site of cultural heritage. The results are of potential value to destination managers of heritage sites for enhancing their understanding of factors influencing the choices of Chinese visitors. In addition, the findings of this study can also assist destination marketers and tourism policy makers to enhance leverage on UGC to strategically position tourism-based products and service at heritage sites.

Following this introduction, the article begins with a literature review. Then, the methodology and results are presented in the next section. Finally, conclusion and discussion were presented with practical implications and limitations of the current study's findings for future studies.

Literature review

Tourist loyalty behaviour

In the marketing literature, customer loyalty is recognized as a deep commitment to buying a product or service again in the future (Oliver, Citation1999). Recognizing the unique features of tourism (e.g. intangible and heterogeneity), destination loyalty means tourists’ commitment toward a destination (Chen & Gursoy, Citation2001; Chi & Qu, Citation2008), and it can be described as the behavioural intentions of tourists to revisit and make positive recommendations about a particular destination to others through word-of-mouth (Almeida-Santana & Moreno-Gil, Citation2018).

There are three fundamental reasons offered as a rationale for continued examination of destination loyalty in the marketing and tourism literature. First, loyal customers are less sensitive to prices, showing a greater willingness to pay (Alegre & Juaneda, Citation2006). Second, loyal customers not only important in increasing revenue in destinations, but also act as channels of information that spread positive word-of-mouth to other potential travellers to a destination (Almeida-Santana & Moreno-Gil, Citation2018; McMullan & Gilmore, Citation2008). Third, since tourist consumption may be driven by constraints of time and a range of other factors (Thurnell-Read, Citation2017), destination loyalty is harder to obtain than general customer loyalty, so greater marketing efforts are required (Lv & McCabe, Citation2020).

Due to the practical importance of destination loyalty, numerous studies have been made to examine the antecedents that are likely to influence destination loyalty. These studies show the causes of loyalty or behaviour intentional include motivations (Lee & Hsu, Citation2013; Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005), service quality (Keshavarz & Jamshidi, Citation2018), destination image (Chiu et al., Citation2016), satisfaction (Keshavarz & Jamshidi, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2011) and visit intensity (Antón et al., Citation2017). For example, Kim (Citation2018) found that memorable tourism experiences influence destination loyalty both directly and indirectly through destination image and tourist satisfaction. Similar findings were also reported by Moon and Han (Citation2019) and Sharma and Nayak (Citation2018) discovered significant effects of tourists’ emotional responses in predicting destination image, satisfaction and destination loyalty.

Although a number of explanations have been proposed to explain tourist loyalty formation, a common assumption from the accumulated research is that when tourists perceive a positive destination image, they exhibit a higher level of satisfaction, which then leads to revisit or recommend intentions. However, research concerning the effects of social media on tourist loyalty formation process is scarce and the relationship between UGC and loyalty behaviour is still not clear. Therefore, this study proposes a theoretical destination loyalty formation model that builds on findings of previous studies (destination image→satisfaction→loyalty) by integrating UGC influences into the model.

UGC sources in social media

User-generated content (UGC) refers to media content created or produced by the general public primarily distributed on the Internet (Daugherty et al., Citation2008). The growth of UGC in social media has had a significant influence on travellers’ decision-making and tourism operations and management. However, UGC research is still in its early stages and there are some aspects that still need to be explored, such as the sources of UGC (Zeng & Gerritsen, Citation2014). UGC impacts on tourist behaviour have been investigated for Twitter (Liu et al., Citation2017; Sotiriadis & Van Zyl, Citation2013), Tripadvisor (Amaral et al., Citation2014; Guo et al., Citation2017) and YouTube (Mir & Ur Reham, Citation2013). Narangajavana et al. (Citation2019) classified UGC sources based on UGC contributors. However, there are few studies on how UGC influences tourist perception and behaviour.

In tourist psychology studies, much empirical research supports the premise that the formation of destination image is composed of two dimensions: cognitive process and affective process (Crompton, Citation1979). Cognitive process refers to the knowledge about a destination, mainly focusing on tangible physical attributes and characteristics (Baloglu & McCleary, Citation1999; Pike & Ryan, Citation2004); while affective process is represented by an individual’s feelings and emotions towards the tourist destination (Chen & Uysal, Citation2002; Kim & Richardson, Citation2003). Phelps (Citation1986) proposed that destination images could be categorized into primary and secondary types: the first is based on the actual visit and the second is based on external information.

UGC has gained popularity among travellers (Ayeh et al., Citation2013), since it empowers consumers to easily obtain up to date information on destinations and services reported by other tourists, such as popular tourist attractions, local transportation, and travel tips. Furthermore, this aggregated information also includes photographs, videos and stories, all of which may positively influence tourist feelings and emotions towards the destination. As such, UGC is not only an information base for tourism purchasing decisions but also supporting information that plays a formative role in developing perceptions of a destination (Luo & Zhong, Citation2015). In this study, the types of UGC related tourism are categorized as factual UGC and emotional UGC. Factual UGC is tourist-generated factual information about a destination, such as ticket price, transportation routes, events information and relevant interpretation information of scenic spots, which give basic facts to the tourists and affects their cognitive perception towards the destination (Li et al., Citation2008). Emotional UGC refers to any form of information, such as famous music and films mentioned in online UGC, which may trigger a tourist’s imagination and affect emotional perceptions of a destination (Hadinejad et al., Citation2019; Kim, Citation2012). To create a hypothetical example, when describing their travel experience to the United Kingdom, tourists who are fans of Harry Potter may insert clips of Harry Potter films and put photographs of filming locations in their travel blogs. Emotions stimulated by film clips and photographs may influence the choice of travel destinations are here regarded to be emotional UGC.

Destination image

Destination image is commonly conceptualized as a mental or attitudinal construct consisting of the sum of beliefs, ideas and impressions that a tourist holds about a destination (Fakeye & Crompton, Citation1991). Tourists’ perceived image of destination is dynamic (Lee et al., Citation2014) and it can be shaped and shared by groups of people (Jenkins, Citation1999).

In the literature, scholars have distinguished between different types of images formed during specific stages (i.e. pre-visit, during a visit and post-visit) of the tourism experience (Lee et al., Citation2014; Xu & Ye, Citation2018). Pre-visit images are formed before experiencing a destination and thus influence tourist intention to visit and their ultimate destination choice (Baloglu & McCleary, Citation1999). It is also influenced by secondary information sources (Martín-Santana et al., Citation2017). In contrast, post-visit images are formed during a trip and acquired through on-site recreation experiences (Beerli & Martin, Citation2004; Bigne et al., Citation2001). However, the majority of studies on destination images have only examined tourists’ pre-visit or post-visit images. For example, earlier studies have explored post-visit image perceptions and their relationship with post-trip evaluations, such as satisfaction level (Assaker & Hallak, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2014) and intention to recommend (Papadimitriou et al., Citation2015; Prayag et al., Citation2017). Therefore, by exploring UGC impacts on tourist perception towards the destination, this study aims to empirically examine the influence of dynamic destination images on tourists’ overall satisfaction and behavioural intentions.

Tourist satisfaction

In the consumer market literature, scholars define satisfaction as a consumer’s fulfilment response (Oliver, Citation1977). The process of tourist satisfaction formation is typically explained by Oliver’s expectancy disconfirmation paradigm (Oliver, Citation1980), which states that a customer’s overall satisfaction results from the comparison between expectation and outcome performance. When perceived performance is equal to, or greater than the expected performance, tourists will be satisfied. Otherwise, the tourist may be dissatisfied.

However, some scholars have criticized the disconfirmation model because there is no conclusive evidence that expectations lead to satisfaction or dissatisfaction, particularly when tourists have a lower expectation (Barsky & Labagh, Citation1992). According to the disconfirmation paradigm, low expectation improves the chances of satisfaction, which means a tourist will be satisfied if she or he expects or receives less performance. However, LaTour and Peat (Citation1979) noted that low expectations rarely translate into satisfaction in practice. To avoid this weakness of the disconfirmation model, this study will assess visitor satisfaction using a global measurement (Assaker et al., Citation2011; Olsen, Citation2007; Vaske et al., Citation1986; Williams, Citation1989), which is a method to evaluate overall satisfaction that does not compare the gap between actual performance and expectation in questionnaire design.

Research hypotheses development

The effect of UGC

The importance of UGC in forming a destination image is recognized by both academics and practitioners (Burgess et al., Citation2011; Stankov et al., Citation2010). Marchiori and Cantoni (Citation2015) found UGC increased tourist positive beliefs about a destination, especially those related to value for money and weather; and an experiment with more than 190 participants highlighted the effectiveness of UGC on tourist cognitive formation of destination image (Amaral et al. Citation2014).

Additionally, a few scholars have also positively explored the usefulness of UGC in affecting tourists’ feelings and emotions towards destinations. For example, Serna et al. (Citation2016) found that underlying emotions generated by UGC had a powerful effect in the formation of tourist perception. After investigating how photographs posted in travel blogs affected tourists’ perceptions of Russia as a travel destination, Kim and Stepchenkova (Citation2015) discovered that photographs failed to encourage tourists to visit the destination, but they did produce an impression to tourists that Russia was a clean, safe and friendly country.

On social media platforms, the shared experience by tourists includes not only knowledge-related aspects, such as facts about destination attributes (e.g. product price, weather condition and related tourist attraction information), but also includes communication about emotions, imagination and fantasies about features of a destination.

Based on the theoretical backgrounds, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Factual UGC are positively correlated with destination image.

H2: Emotional UGC are positively correlated with destination image.

The effects of destination image

Prior studies have investigated both direct and indirect influences of destination image on behavioural intentions (Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation2014; Wang & Hsu, Citation2010). Researchers have found that destination image directly contributes to tourist intention to visit and willingness to recommend the tourism products to others (Agapito et al., Citation2013; Hallmann et al., Citation2015; Kock et al., Citation2016). For example, after examining a destination image model in a destination hosting sporting events, Chen and Funk (Citation2010) suggested that destination image is a significant predictor of revisit intention. Moreover, Bigne et al. (Citation2001) found a positive relationship between destination image and willingness to recommend. In support of these previous findings, Kock et al. (Citation2016) identified the significant influence of destination image on willingness to visit and WOM recommendation. Thus, the following hypotheses are developed:

H3: Destination image is positively correlated with revisit intention.

H4: Destination image is positively correlated with WOM intention.

Existing studies also report an indirect impact of destination image on tourist behavioural intentions, particularly through satisfaction (Assaker et al., Citation2011; Chi & Qu, Citation2008; Prayag & Ryan, Citation2012). For example, Suhartanto and Triyuni (Citation2016) proposed a shopping destination loyalty model that includes the destination image. Assaker et al. (Citation2011) suggested that the influence of destination image on destination loyalty is mediated by the overall satisfaction of tourist experience. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formed regarding the impact of destination image on overall satisfaction:

H5: Destination image is positively correlated with overall satisfaction.

The effects of satisfaction

Satisfaction plays an important role in successful destination marketing because it is considered one of the most powerful drivers of tourist behavioural intentions (Oliver, Citation1999), such as destination chosen and decision to revisit (Chen & Gursoy, Citation2001). Studies examining tourist satisfaction have confirmed the positive association between satisfaction and loyal behaviour (i.e. revisit intentions and WOM publicity) (Prayag et al., Citation2017; Rajesh, Citation2013). McDowall (Citation2010) reported that the satisfaction of international tourists visiting Bangkok has significant impacts on their intention to recommend. Hui et al. (Citation2007) further noted that overall satisfaction is a key determinant of WOM publicity among other factors. After interviewing European visitors to Mediterranean destinations, Assaker and Hallak (Citation2013) found tourist satisfaction positively influenced tourists’ revisit intentions. Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypotheses are developed:

H6: Overall satisfaction is positively correlated with revisit intention.

H7: Overall satisfaction is positively correlated with WOM intention.

Methodology

Study site

Gulangyu (also called Kulangsu), located in the southwest of Xiamen city, is a tiny island of 1.88 square kilometres famous for its architecture, unique history and large piano museum. As a place of residence for Westerners during Xiamen's colonial past, many colonial-style mansions, churches, and hospitals were established throughout the island. Gulangyu is an outstanding example of cultural fusion, with a mixture of various architectural styles including the Traditional Southern Fujian Style, Western Classical Revival Style and Veranda Colonial Style. In 2017, Gulangyu, was officially listed as a World Heritage Site (WHS) in recognition of its international cultural and historical importance.

Gulangyu Island was chosen as a case study to examine the effect of UGC on tourist loyalty behaviour for two reasons. Firstly, Gulangyu has long been a popular domestic tourist destination, and is recommended by a large number of travel bloggers, attracting between 25,000 and 65,000 visitors per day (XiamenDaily, Citation2014). In Mafengwo.com (‘马蜂窝’ in Mandarin), the most popular online tourism community in China, the number of UGC about Gulangyu are more than 50,000. Secondly, as a well-known cultural heritage site, Gulangyu has a wide range of various types of attractions in addition to historical buildings. On the island, tourists can visit world-class museums, experience the unique classical music tradition, enjoy romantic beaches and sample the local seafood restaurants and fresh tropical fruits. International musical events, such as the Gulangyu Piano Festival and the Gulangyu Four-Season Music Week are held on the island during holiday periods.

Data collection and sampling

Data were collected on both weekdays and weekends between June and August 2018 as the summer holiday is one of the two peak travel times of the year for Gulangyu. The sample for this study was travellers in Gulangyu who used UGC to plan their trips. Surveyors approached tourists at the entrances and exits of tourist attractions in Gulangyu and asked screening questions (e.g. if they had read relevant UGC travel information in social media before their trips). Only tourists who had used UGC travel information in social media were invited to participate in this survey. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire. Ten research assistants administered the on-site questionnaire survey, all of whom were trained to understand the procedure and etiquette of the questionnaire survey. Interpretation of the question items was given to the respondents if they asked for clarification. In total, 500 respondents were approached and 439 valid questionnaires were obtained, resulting in an 87.8% response rate.

Measurement scales

The survey questionnaire (See Appendix I) included multi-item scales to measure each construct in this study. A five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), was used.

The measures for the factual UGC and emotional UGC were developed for this study based on an extensive literature review (Chung & Koo, Citation2015; Crouch, Citation2011; Ellison et al., Citation2007; Gretzel & Yoo, Citation2008; Vengesayi, Citation2008; Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010). Descriptions of factual UGC and emotional UGC were collected and adapted from the literature to generate the questions. Factual UGC refers to the information reflecting factual attributes of the destination that doesn't involve tourists’ personal feelings towards the destination. Emotional UGC refers to any form of information affecting tourists’ personal feelings towards the destination, and was captured using six questions (See ).

The item for tourist perceived destination image towards Gulangyu was adopted from its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) on the basis of the UNESCO designation (Kulangsu Wanshi Scenic Management office, Citation2018). The original purpose of establishing World Heritage sites is to identify, protect and present attractions of OUV, which is considered as ‘a concept of value based on human perceptions’ (Buckley, Citation2018). This study examines if the World Heritage Site's OUV mirrors tourists’ perceived cultural value (Buckley, Citation2018).

The WOM construct was adapted and slightly modified from the recommendation intention derived from different tourism products (Papadimitriou et al., Citation2018), such as: ‘I would like to recommend some worth-visiting scenic spots on Gulangyu to others’; ‘I would like to recommend the good hotels where I have stayed in during this trip to others’; and ‘I would like to recommend the delicious food that I have tried on this trip to others’.

Four question items were included to measure the satisfaction of tourists which were derived from Bigné et al. (Citation2005); and a further four items were adapted from Castro et al. (Citation2007) to evaluate the revisiting intention of visitors to Gulangyu.

Data analysis

A standard descriptive analysis was carried out to test the normality of all variables before testing the measurement and structural models. The normality assumption for each item was met, as all absolute skewness values were less than 2 and all absolute kurtosis values less than 7 (West et al., Citation1995).

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were then conducted to verify the dimensionality of the UGC. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to empirically test the effects of factual UGC and emotional UGC on tourists’ perceived destination image and their future loyalty behaviour using Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS) 21.0 statistical software with maximum likelihood method of estimation.

Results

Respondents’ profile

The profile of the participants is shown in . There were slightly more females (59.9%) than males. The majority of respondents were below 40 years old (90%) with the 18–30-year-old class being the largest group (73.4%). Approximately 81.3% of respondents had attained an undergraduate degree or higher. Fewer had only a senior secondary level of education (13.4%), and only 5.3% had a junior secondary level. The majority of the respondents were in employment (71.3%), followed by students (24.8%). In terms of income, 36.7% of the respondents had monthly incomes of 3001–6000 RMB, followed by 3000 RMB and below (27.6%) and 6001–9000 RMB (19.1%). Only 8.2% of respondents had a monthly income of more than 12000 RMB. The majority of the respondents are non-local Xiamen residents (94.1%).

Table 1. Profile of survey respondents.

Measurement model

The skewness statistics of all variables of each construct ranged from −0.869 to –0.012, and kurtosis statistics ranged from −0.115 to –2.3, which indicated that the data did not violate the normality assumption (Kline, Citation2011).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to derive the underlying dimensions of the UGC sources. A principal component method with varimax rotation was adopted. To control the number of factors extracted, a minimum eigenvalue of one was used. Items with factor loadings lower than 0.4 and items with cross-loadings greater than 0.4 on more than one factor were excluded (Hai et al., Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2010), because items with these characteristics failed to prove pure measures of a specific construct. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.91, indicating the sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 2855.68 (df = 66, p < 0.001), supporting the factorability of the data (Hair et al., Citation1995). Two underlying dimensions of UGC, corresponding to factual UGC and emotional UGC, were identified. These two factors explained 61.01% of the variance in UGC sources. Two items were removed from the analysis because their factor loadings were below 0.4.

Afterward, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the overall measurement model including all latent constructs, and its adequacy was assessed. The findings indicated an acceptable model fit: X2 = 1107.70, df = 449, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.93, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.92, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.58, t-values for the standardized factor loadings of items were significant (p < 0.001), suggesting that they are significant indicators of their respective constructs.

displays the average variance extracted (AVE) and the composite reliability (CR) scores for each construct. Results showed that all of the AVE values approached to 0.5 and CR scores were greater than the commonly recommended level of 0.7 (ranging between 0.78–0.94) respectively. Therefore, convergent validity was supported (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Discriminant validity was also supported (See ), as the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than its relation with other factors (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 2. Results for overall measurement model

Table 3. Inter-construct Correlations

Structural model and hypothesis testing

The hypothesized relationships were tested and structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed to verify the relationships among factual UGC and emotional UGC, destination image, satisfaction, recommendation (WOM) and intention to revisit. The fit indices of the structural equation model demonstrated that the model fitted the data well (x2 = 1231.682, df = 457, CFI = 0.906, TLI = 0.898, RMSEA = 0.066) (Hair et al., Citation2010).

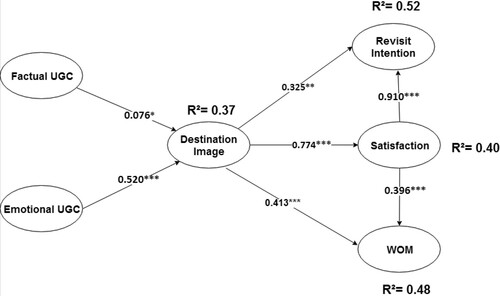

and present findings of the main effects. Both factual and emotional UGC were significantly and positively correlated with destination image (β1 = 0.076; β1 = 0.520), supporting H1 and H2. UGC explained 37% of the variance in tourist perceived destination image (R² = 0.37). Significant paths emerged between destination image and revisit intention (β3 = 0.325), destination image and WOM (β4 = 0.413), destination image and satisfaction (β5 = 0.325). Thus H3, H4 and H5 were accepted. Destination image explained 40% of the variance in tourist satisfaction. Hypothesis 6, proposing a relationship between destination image and revisiting intention, was also supported (β6 = 0.910). Together, satisfaction and destination image predicted 52% of tourist revisiting intention. Finally, as hypothesized, the relationships between satisfaction and WOM was positive and significant (β7 = 0.396). Destination image and satisfaction explained 48% variance in intention to recommendation.

Figure 2. Results of the estimated equation structural model.

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 4. Estimated results for the main effects

Conclusion and discussion

Although tourism research acknowledges the importance of UGC impacts on tourist behaviours (Cox et al., Citation2009; Lu & Stepchenkova, Citation2015), direct and indirect effects of UGC on loyalty behaviour are still in need of elucidation. The main objective of this study is to examine the relationship between factual UGC, emotional UGC, destination image, satisfaction and loyalty behaviour (WOM and revisit intention). The study demonstrates the predictive power of UGC in the pre-trip period, which in turn affects tourists’ loyalty behaviour at the post-trip stage. This result contributes to existing theory and is congruent with research on marketing in three ways (Almeida-Santana & Moreno-Gil, Citation2018; Nisar & Whitehead, Citation2016; Prayag et al., Citation2017; van Asperen et al., Citation2018).

Firstly, this research divided traveler-generated contents in social media into factual UGC and emotional UGC. The empirical results show that both factual and emotional UGC are positively associated with destination image, which supports H1 and H2. To date, marketing scholars have distinguished between cognitive and affective aspects of destination image because tourists’ destination image formation processes tend to simultaneously be influenced by their cognition and emotion. When tourists used UGC to plan their vacation, the virtual contents act as a cue in forming users’ destination image. This study is among the first attempts to distinguish and empirically demonstrate that two different types of UGC are both conceptually and empirically meaningful in predicting destination image formation. The results reveal that factual UGC helps to increase tourists’ knowledge of the destination, such as attractions, costs, transportation, history, indicating that tourists can clearly perceive the destination image if they are able to obtain sufficient destination information before their trip. The results also suggest that emotional UGC significantly affects tourists’ psychological attitudes towards the destination, indicating that tourists better perceive the cultural value of the destination if they look through, and accept more, e-WOM information on social media.

Unlike physical products, tourism services cannot be experienced before they are purchased (Gursoy & McCleary, Citation2004). However, contrary to a prior study (Jani & Hwang, Citation2011), this study found that the magnitude of the impact of factual UGC on destination image formation (β = 0.076, p < 0.05) is relatively weak when compared with that of emotional UGC (β = 0.520, p < 0.001), implying that emotional information is the most significant determinant of destination image during the pre-trip stage.

Secondly, the results of this study show that a favourable image of a particular destination could produce repeat visits as well as positive WOM effects to potential tourists, adding further evidence that UGC could indirectly influence tourist destination loyalty through destination image, thus, H3 and H4 were supported. Theoretically, there is no consensus in the literature on the magnitude and direction of the relationships between different components of destination image (cognitive and affective) and tourists’ destination loyalty (Zhang et al., Citation2014). Although destination image is found to have direct and positive impacts on destination loyalty (Chi & Qu, Citation2008; Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005), that is not a necessary predictor of loyalty. One argument holds that tourists are often motived by novelty seeking, so even though they hold a clear and positive image of a destination, they may not make repeat visits. (Pearce & Lee, Citation2005). However, the results of this study indicate that destination image is positively associated with intention to return and willingness to recommend, reconfirming the important role of UGC in both cognitive and affective destination image formation and predicting loyal outcomes. One possible reason for these findings is that detailed and updated UGC help tourists to explore diverse dimensions of the destination, and this may be of particular relevance to cultural heritage sites with museums and concerts. For example, tourists who have visited the destination may visit again, because the information relevant to new exhibitions and events of the destination is updated by other tourists. Thus, UGC may inspire tourists to revisit the same destination, but acquire different travel experiences. In this respect, UGC significantly enhances tourist destination loyalty behaviour.

Thirdly, this study found that in addition to enhancing tourists’ intention to return and to recommend destination in the future, destination image can also influence destination loyalty, indirectly through the mediating variable, satisfaction; thus, H5, H6 and H7 were supported. When tourists perceive the value of the destination and tend to develop a positive destination image, they exhibit a higher level of satisfaction and are more likely to promote the destination to others and also revisit. This implies that tourists’ satisfied travel experience can maximized tourist retention and have a greater chance fostering positive WOM. The findings support the idea broadly suggested and verified in tourism that satisfaction is a key antecedent of destination loyalty (Assaker et al., Citation2011; Lee & Hsu, Citation2013; Prayag & Ryan, Citation2012). Hence, it would be worthwhile for destination managers to consider the role tourist satisfaction played in developing destination loyalty and make greater investments in their tourism destination resources, in order to continue to enhance tourists’ experiences and increase their satisfaction.

Practical implications

This study may provide interesting and important implications for practitioners and managers for maintaining and developing destination competitiveness within social media settings.

The results highlight that both emotional UGC and factual UGC positively affect tourists’ evaluation of destination image, with emotional UGC having a greater influence. The concomitant recommendation is that destination managers should enhance marketing and promotion strategies to take this into account. Factual UGC can be regarded as an effective pre-trip interpretation, which may serve as a realistic image builder for tourists who are planning to visit the destination, destination marketers should provide more updated information and immersed experience for pre-tourists; for example, using 360-degree images to provide online virtual tours on the official website. This enables potential tourists to have clearer cognition of the destination, so they are better placed to perceive the cultural value of the heritage sites. On the other hand, destination advertising should not only stress the major attractions and facilities a destination can offer, since this provides no incentive for tourists who have already familiar with them. Rather, destination managers should promote a holistic image based on specific emotions a destination elicits. Marketing campaigns can enhance tourists’ involvement in sharing more emotional experiences via pictures and videos that can be evoked by the destination (such as a historical and artistic image). To instigate an emotional appeal, many tourist destinations have successfully demonstrated sophisticated imagery and music in their advertising. For example, Sri Lanka encourages tourists to create visual content (i.e. photos and microfilms) about tea plantation and children smiling on social networks and destination managers promote the destination with corresponding slogans, such as ‘Aroma of tea, across the Pacific’ and ‘Smile in the Indian Ocean’. This approach has successfully opened a Chinese tourist market.

Further, visitors’ satisfaction reflects a dynamic balance between the demand (expectation) and the supply (delivery) (Kandampully & Suhartanto, Citation2000). In the context of this study, satisfaction represents the quality of heritage tourism experiences that tourists perceived. As found in this study, visitors who are able to perceive the cultural value of the heritage site will develop high levels of satisfaction and destination loyalty. Therefore, destination managers should investigate how each destination image scale items will be evoked and triggered by a destination's offerings and subsequently develop a marketing programme that consists of setting up those expectations that positively affect tourists to visit the destination.

Finally, the results of this study provide destination management with an improved understanding of the indirect influence of UGC on revisiting and WOM intentions through destination image and satisfaction. Our analysis confirmed the need to consider UGC as contemporary key sources of a destination's image. As individuals formulate destination images from the secondary information source (Beerli & Martin, Citation2004), this practice will push individual tourists to formulate positive destination images before their visit and have a chance to inspire individuals to spread positive e-WOM back to the social media platform, which creates a virtuous perception. Therefore, destination managers should be advised to establish strategies to encourage and guide their tourists to actively share their travel experience with rich and high-quality information on the websites, increasing destination visibility and attracting more visitors.

Limitations and future research

Although this study provides valuable insights into the combined influences of emotional UGC, factual UGC, destination image, and satisfaction on loyalty behaviours, several limitations should be mentioned. First, this study focused on individual visitors to Gulangyu. Young people are more likely to use UGC to plan their trips, so the sample used in this study largely consisted of young travellers from China. Future researchers could extend this study to other cultural groups and age ranges. Second, this study is only based on a single WHS, Gulangyu. Future research could test the proposed model at other WHS either in China or other countries in order to extend its conclusions and compare the results. Finally, the measures of factual UGC and emotional UGC are recently developed, and their applicability should be reexamined in the future.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the student research assistants of the Xiamen University for helping in questionnaire surveys and the funding support from the Departmental Special Research Project provided by the Department of Social Sciences of the Education, University of Hong Kong.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Han Xu

Han Xu is a Ph.D. student in the School of Geography at University of Leeds and is a research assistant in the Department of Social Sciences at the Education University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include social media, tourist behaviour and sustainable tourism development.

Lewis T.O. Cheung

Lewis T.O. Cheung is an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Sciences of the Education University of Hong Kong. His research interests focus on sustainable tourism in protected areas, environmental education, and environmental conservation.

Jon Lovett

Jon Lovett is a Professor in the School of Geography at University of Leeds. He holds the position of Chair in Global Challenges. His main interest is natural resource management. His research focuses on natural resource management and takes an interdisciplinary approach bringing together both the natural and social sciences.

Xialei Duan

Xialei Duan is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of International Tourism and Management at City University of Macau. She received the doctoral degree in the Department of Geography and Resource Management at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in December 2018. Her research interests include destination image, branding and sustainable tourism.

Qing Pei

Qing Pei is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Sciences of the Education University of Hong Kong. His research interests focus on Environmental Humanities and Environmental Economics

Dan Liang

Dan Liang is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public affairs at Xiamen University. His research interests focus on forest policy, rural land use and environmental policy.

References

- Agapito, D., Oom do Valle, P., & da Costa Mendes, J. (2013). The cognitive-affective-conative model of destination image: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(5), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.803393

- Akhoondnejad, A. (2016). Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of Turkmen handicrafts festival. Tourism Management, 52, 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.027

- Alegre, J., & Juaneda, C. (2006). Destination loyalty: Consumers’ economic behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), 684–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.03.014

- Almeida-Santana, A., & Moreno-Gil, S. (2018). Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tourism Management, 65, 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.011

- Amaral, F., Tiago, T., & Tiago, F. (2014). User-generated content: Tourists’ profiles on tripadvisor. International Journal of Strategic Innovative Marketing, 1(3), 137–145. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/User-generated-content-%3A-tourists-'-profiles-on-Amaral-Tiago/983dbabf4a40093e9d24629eb5f6708e3561f5eb?p2df

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., & Stoppani, A. (2019). Analyzing online reviews in hospitality: Data-driven opportunities for predicting the sharing of negative emotional content. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(15), 1904–1917. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1594723

- Antón, C., Camarero, C., & Laguna-García, M. (2017). Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 238–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.936834

- Assaker, G., & Hallak, R. (2013). Moderating effects of tourists’ novelty-seeking tendencies on destination image, visitor satisfaction, and short-and long-term revisit intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 52(5), 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513478497

- Assaker, G., Vinzi, V. E., & O’Connor, P. (2011). Examining the effect of novelty seeking, satisfaction, and destination image on tourists’ return pattern: A two factor, non-linear latent growth model. Tourism Management, 32(4), 890–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.08.004

- Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). Towards an understanding of online travellers' acceptance of consumer-generated media for travel planning: Integrating technology acceptance and source credibility factors. In L. Cantoni & Z. Xiang (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2013 (pp. 254–267). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36309-2_22

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00030-4

- Barsky, J. D., & Labagh, R. (1992). A strategy for customer satisfaction. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 33(5), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049203300524

- Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

- Bigne, J. E., Sanchez, M. I., & Sanchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tourism Management, 22(6), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00035-8

- Bigné, J. E., Andreu, L., & Gnoth, J. (2005). The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 26(6), 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.006

- Buckley, R. (2018). Tourism and natural World Heritage: A complicated relationship. Journal of Travel Research, 57(5), 563–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517713723

- Bulut, Z. A., & Karabulut, A. N. (2018). Examining the role of two aspects of eWOM in online repurchase intention: An integrated trust–loyalty perspective. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(4), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1721

- Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., Cox, C., & Buultjens, J. (2011). Trust perceptions of online travel information by different content creators: Some social and legal implications. Information Systems Frontiers, 13(2), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-009-9192-x

- Castro, C. B., Armario, E. M., & Ruiz, D. M. (2007). The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destination's image and tourists’ future behaviour. Tourism Management, 28(1), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.013

- Chen, C.-F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

- Chen, J. S., & Gursoy, D. (2001). An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(2), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110110381870

- Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2002). Market positioning analysis: A hybrid approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 987–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00003-8

- Chen, N., & Funk, D. C. (2010). Exploring destination image, experience and revisit intention: A comparison of sport and non-sport tourist perceptions. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 15(3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2010.513148

- Chi, C. G.-Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

- Chiu, W., Zeng, S., & Cheng, P. S.-T. (2016). The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(2), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2015-0080.

- Chung, N., & Koo, C. (2015). The use of social media in travel information search. Telematics and Informatics, 32(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2014.08.005

- Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(8), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620903235753

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. Journal of Travel Research, 17(4), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757901700404

- Crouch, G. (2011). Senior citizens and social media. Media Badger. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from http://www.mediabadger.com/2011/10/senior-citizens-and-social-media/

- Daugherty, T., Eastin, M. S., & Bright, L. (2008). Exploring consumer motivations for creating user-generated content. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 8(2), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2008.10722139

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

- Fakeye, P. C., & Crompton, J. L. (1991). Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower rio Grande valley. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759103000202

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. SAGE Publications.

- Gretzel, U., & Yoo, K. H. (2008). Use and impact of online travel reviews. In P. O'Connor, W. Höpken, & U. Gretzel (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2008 (pp. 35–46). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-77280-5

- Guo, Y., Barnes, S. J., & Jia, Q. (2017). Mining meaning from online ratings and reviews: Tourist satisfaction analysis using latent dirichlet allocation. Tourism Management, 59, 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.009

- Gursoy, D., & McCleary, K. W. (2004). Travelers’ prior knowledge and its impact on their information search behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 28(1), 66–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348003261218

- Hadinejad, A., Moyle, B. D., Scott, N., & Kralj, A. (2019). Emotional responses to tourism advertisements: The application of FaceReader™. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(1), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1505228

- Hai, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & William, C. B. (1998). Mutvariate data analysis. NJ Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis. Macmillan.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Advanced diagnostics for multiple regression: A supplement to multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Hallmann, K., Zehrer, A., & Müller, S. (2015). Perceived destination image: An image model for a winter sports destination and its effect on intention to revisit. Journal of Travel Research, 54(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513513161

- Hui, T. K., Wan, D., & Ho, A. (2007). Tourists’ satisfaction, recommendation and revisiting Singapore. Tourism Management, 28(4), 965–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.08.008

- Jani, D., & Hwang, Y.-H. (2011). User-generated destination image through weblogs: A comparison of pre-and post-visit images. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 16(3), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.572670

- Jenkins, O. H. (1999). Understanding and measuring tourist destination images. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-1970(199901/02)1:1<1::AID-JTR143>3.0.CO;2-L

- Kandampully, J., & Suhartanto, D. (2000). Customer loyalty in the hotel industry: The role of customer satisfaction and image. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(6), 346–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110010342559

- Keshavarz, Y., & Jamshidi, D. (2018). Service quality evaluation and the mediating role of perceived value and customer satisfaction in customer loyalty. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 4(2), 220–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2017-0044

- Kim, H., & Richardson, S. L. (2003). Motion picture impacts on destination images. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00062-2

- Kim, H., & Stepchenkova, S. (2015). Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: Manifest and latent content. Tourism Management, 49, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.004

- Kim, J.-H. (2018). The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517721369

- Kim, M., & Kim, J. (2020). The influence of authenticity of online reviews on trust formation among travelers. Journal of Travel Research, 59(5), 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519868307

- Kim, S. (2012). Audience involvement and film tourism experiences: Emotional places, emotional experiences. Tourism Management, 33(2), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.04.008

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kock, F., Josiassen, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2016). Advancing destination image: The destination content model. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.003

- Költringer, C., & Dickinger, A. (2015). Analyzing destination branding and image from online sources: A web content mining approach. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1836–1843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.011

- Kulangsu Wanshi Scenic Management office. (2018). Outstanding Universal Value of Kulangsu (in Chinese 鼓浪屿普世价值). Retrieve July 15,2019, from http://www.glysyw.com/.

- LaTour, S. A., & Peat, N. C. (1979). Conceptual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research. In W. L. Wilkie (Ed.), NA - Advances in consumer research volume 6 (pp. 431–437). Association for Consumer Research. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/9591/volumes/v06/NA-06

- Lee, B., Lee, C.-K., & Lee, J. (2014). Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496466

- Lee, S., Jeon, S., & Kim, D. (2011). The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1115–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.016

- Lee, T. H., & Hsu, F. Y. (2013). Examining how attending motivation and satisfaction affects the loyalty for attendees at aboriginal festivals. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.867

- Leung, D., Law, R., Van Hoof, H., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.750919

- Li, X., Petrick, J. F., & Zhou, Y. (2008). Towards a conceptual framework of tourists’ destination knowledge and loyalty. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 8(3), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15280080802080474

- Liu, X., Burns, A. C., & Hou, Y. (2017). An investigation of brand-related user-generated content on Twitter. Journal of Advertising, 46(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1297273

- Lu, W., & Stepchenkova, S. (2015). User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24(2), 119–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.907758

- Luo, Q., & Zhong, D. (2015). Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tourism Management, 46, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.07.007

- Lv, X., & McCabe, S. (2020). Expanding theory of tourists’ destination loyalty: The role of sensory impressions. Tourism Management, 77, 104026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104026

- Marchiori, E., & Cantoni, L. (2015). The role of prior experience in the perception of a tourism destination in user-generated content. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.001

- Martín-Santana, J. D., Beerli-Palacio, A., & Nazzareno, P. A. (2017). Antecedents and consequences of destination image gap. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.11.001

- Matute, J., Polo-Redondo, Y., & Utrillas, A. (2016). The influence of EWOM characteristics on online repurchase intention. Online Information Review, 40(7), 1090–1110. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2015-0373

- McDowall, S. (2010). International tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: Bangkok, Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660903510040

- McMullan, R., & Gilmore, A. (2008). Customer loyalty: An empirical study. European Journal of marketing, 42(9/10), 1084–1094. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560810891154

- Mir, I. A., & Ur Reham, K. (2013). Factors affecting consumer attitudes and intentions toward user-generated product content on YouTube. Management & Marketing, 8(4), 637–654.

- Moon, H., & Han, H. (2019). Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1494083

- Narangajavana, Y., Callarisa Fiol, L. J., Moliner Tena, M. A., Rodriguez Artola, R. M., & Sanchez Garcia, J. (2019). User-generated content sources in social media: A new approach to explore tourist satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517746014

- Narangajavana, Y., Fiol, L. J. C., Tena, MÁM, Artola, R. M. R., & García, J. S. (2017). The influence of social media in creating expectations. An empirical study for a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.002

- Nezakati, H., Amidi, A., Jusoh, Y. Y., Moghadas, S., Aziz, Y. A., & Sohrabinezhadtalemi, R. (2015). Review of social media potential on knowledge sharing and collaboration in tourism industry. Procedia-social and Behavioral Sciences, 172, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.344

- Nisar, T. M., & Whitehead, C. (2016). Brand interactions and social media: Enhancing user loyalty through social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.042

- Oliveira, B., & Casais, B. (2019). The importance of user-generated photos in restaurant selection. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-11-2017-0130

- Oliver, R. L. (1977). Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on postexposure product evaluations: An alternative interpretation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(4), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.62.4.480

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429990634s105

- Olsen, S. O. (2007). Repurchase loyalty: The role of involvement and satisfaction. Psychology & Marketing, 24(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20163

- Papadimitriou, D., Apostolopoulou, A., & Kaplanidou, K. (2015). Destination personality, affective image, and behavioral intentions in domestic urban tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 54(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513516389

- Papadimitriou, D., Kaplanidou, K., & Apostolopoulou, A. (2018). Destination image components and word-of-mouth intentions in urban tourism: A multigroup approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348015584443

- Pearce, P. L., & Lee, U.-I. (2005). Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504272020

- Phelps, A. (1986). Holiday destination image—the problem of assessment: An example developed in Menorca. Tourism Management, 7(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(86)90003-8

- Pike, S., & Ryan, C. (2004). Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263029

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515620567

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410321

- Rajesh, R. (2013). Impact of tourist perceptions, destination image and tourist satisfaction on destination loyalty: A conceptual model. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 11(3), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2013.11.039

- Serna, A., Gerrikagoitia, J. K., & Bernabé, U. (2016). Discovery and classification of the underlying emotions in the user generated content (UGC). In A. Inversini & R. Schegg (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2016 (pp. 225–237). Springer.

- Setiawan, P. Y., Troena, E. A., & Armanu, N. (2014). The effect of e-WOM on destination image, satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 3(1), 22–29.

- Sharma, P., & Nayak, J. K. (2018). Testing the role of tourists’ emotional experiences in predicting destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A case of wellness tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.07.004

- Sotiriadis, M. D., & Van Zyl, C. (2013). Electronic word-of-mouth and online reviews in tourism services: The use of twitter by tourists. Electronic Commerce Research, 13(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-013-9108-1

- Stankov, U., Lazic, L., & Dragicevic, V. (2010). The extent of use of basic Facebook user-generated content by the national tourism organizations in Europe. European Journal of Tourism Research, 3(2), 105–113.

- Suhartanto, D., & Triyuni, N. N. (2016). Tourist loyalty toward shopping destination: The role of shopping satisfaction and destination image. European Journal of Tourism Research, 13, 84–102. https://ejtr.vumk.eu/index.php/about/article/view/233

- Tham, A., Croy, G., & Mair, J. (2013). Social media in destination choice: Distinctive electronic word-of-mouth dimensions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751272

- Thurnell-Read, T. (2017). ‘What’s on your bucket list?’: Tourism, identity and imperative experiential discourse. Annals of Tourism Research, 67, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.08.003

- van Asperen, M., de Rooij, P., & Dijkmans, C. (2018). Engagement-based loyalty: The effects of social media engagement on customer loyalty in the travel industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 19(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2017.1305313

- Vaske, J. J., Fedler, A. J., & Graefe, A. R. (1986). Multiple determinants of satisfaction from a specific waterfowl hunting trip. Leisure Sciences, 8(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408609513066

- Vengesayi, S. (2008). Destination attractiveness: Are there relationships with destination attributes? The Business Review, Cambridge, 10(2), 289–294.

- Wang, C.-y., & Hsu, M. K. (2010). The relationships of destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: An integrated model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 27(8), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2010.527249

- Wang, C., Qu, H., & Hsu, M. K. (2016). Toward an integrated model of tourist expectation formation and gender difference. Tourism Management, 54, 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.009

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (p. 56–75). Sage Publications.

- Williams, D. R. (1989). Great expectations and the limits to satisfaction: A review of recreation and consumer satisfaction research [Paper presentation]. Outdoor Recreation Benchmark 1988: Proceedings of the National Outdoor Recreation Forum, Tampa, Florida.

- XiamenDaily. (2014). The daily maximum tourist carrying capacity in Gulangyu is approved to be 65,000 and tourist flow will be regulated (in Chinese 鼓浪屿日最大承载量核定为6.5万人次将调控客流). http://www.mnw.cn/xiamen/news/796874.html.

- Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

- Xu, H., & Ye, T. (2018). Dynamic destination image formation and change under the effect of various agents: The case of Lijiang, 'The Capital of Yanyu’. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.06.009

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

- Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A Review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001

- Zhang, H., Fu, X., Cai, L. A., & Lu, L. (2014). Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 40, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.006