ABSTRACT

Tourism in national parks is on the rise and contributes to shaping notions of the non-human world (often depicted as ‘nature’). One country that is currently facing a shift towards an enhanced emphasis on tourism in its national parks is Sweden. This article aims to unravel, illuminate, and problematize ways of seeing the non-human world in tourists’ Instagram posts about Swedish national parks, and also to consider the productive effects these might have on the relationship between humans and the non-human world. In a discursive and visual cultural analysis, representations of the non-human world, how they are situated in historically inherited ways of seeing, and what implications they might have for how humans approach and understand the non-human world are traced and reflected upon. These representations construct ways of seeing the non-human world as a sublime, desolate, and physically challenging treasury of unique character. In this way, a romantic tourist gaze is constructed, which approaches the national parks as isolated enclaves and commodified havens that offer tourists an escape from humanity, grand views, and seclusion. The main implication of this tourist gaze is a sustaining of the approach to the human world and the non-human world as separated.

Introduction

During the last 40 years, the interest in touristic experiences of the non-human world (often depicted as ‘nature’) has increased worldwide. One such genre is nature-based tourism, anchored in Western understandings of nature as a distant world in desperate need of protection from human exploitation, while simultaneously sold as a tourist product (Holden, Citation2015). Recently, a number of nature-based tourism destinations, such as national parks, have experienced an increase in visitors (Puhakka & Saarinen, Citation2013). One country currently facing a shift transforming them from establishments with little tourism to significant tourism destinations – is Sweden (Fälton, Citation2021; Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020). During the last 20 years, the interest in experiences of nature and nature-based tourism has risen (Emmelin, Citation1989; Sandell, Citation2009) and made the parks a central part of the country’s experience economy (Carlgren, Citation2009; Lundmark & Stjernström, Citation2009). In relation to this, The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (hereafter SEPA), has made several efforts to transform the parks in this direction by making them better known to the public, improving their accessibility (SEPA, Citation2017) and designing a cohesive brand. In these efforts, the agency has underlined the parks’ role as tourism destinations and predicted that they will become an even more essential part of the Swedish tourism industry in the years to come. For example, the agency has expressed a wish concerning the parks becoming one of Europe’s most popular nature-based tourism destinations by 2030. Increasing the number of tourists has been an essential part of this, and the agency has argued that the parks should not be approached only as preservers of nature but also as valuable and refined tourism destinations (SEPA, Citation2011).

This national shift, as well as the international tourist focus on national parks, can be mirrored in an intensification of tourism research. Several national and international studies have pointed towards national parks as important nature-based tourism destinations supplying outdoor recreation (Carlgren, Citation2009; Lundmark & Stjernström, Citation2009; Namiecinski et al., Citation2019; Puhakka & Saarinen, Citation2013) and have covered topics such as the parks’ ability to host sustainable tourism (Cottrell & Cutumisu, Citation2006; Karhu et al., Citation2020; Wondirad & Ewnetu, Citation2019), their impact on and opportunities for regional development (Brankov et al., Citation2019; Jaafar et al., Citation2015; Lundmark et al., Citation2010), and their tourism history (Roe, Citation2020; Wall-Reinius, Citation2009). Several studies have also focused on tourists’ recreational preferences and experiences of nature. For example, Raadik et al. (Citation2010) investigated tourists’ preferences for recreational experiences by conducting a survey in a Swedish national park. Rathmann et al. (Citation2020) explored tourists’ perceptions of and preferences for national park characteristics by analysing the photographs taken in a German national park. Niezgoda and Nowacki (Citation2020) have examined tourists’ experiences of nature in a Polish national park by analysing TripAdvisor reviews. Furthermore, through the lens of Swedish national parks and tourists’ Instagram posts, Conti and Heldt Cassel (Citation2020) have explored how liminality is expressed as part of tourists’ experiences of nature-based tourism. Through the same lens, Conti and Lexhagen (Citation2020) have studied the role played by tourists’ photographs shared on Instagram in creating experience values in nature-based tourism.

Yet another string of studies have paid attention to ways of seeing the non-human world constructed through tourism related to the parks (Cronin, Citation2011; Fälton, Citation2021; Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020; Grusin, Citation2004; Patin, Citation1999, Citation2012; Rutherford, Citation2011). Such approaches are needed, not only because national park tourism contributes to shaping human understandings of the world that we call nature (see Fletcher, Citation2014; Harvey, Citation1996; Saarinen, Citation2016; Tschida, Citation2012), but also because they can help us understand broader questions around climate and the environment (Rutherford, Citation2011). Even if two recent studies have focused on Sweden, there is an overrepresentation of studies applying a Northern American focus. Since ways of seeing the non-human world are constructed in relation to national parks worldwide, it is crucial to shed light on other geographical contexts. Due to the shifting times that the Swedish national parks currently face, where their role as tourism destinations is being reformed, they represent an interesting context for researching ways of seeing the non-human world produced through the practice of tourism (Fälton, Citation2021; Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020). Furthermore, the existing studies focusing on ways of seeing the non-human world parks have only focused on such empirical materials produced by actors who manage the parks or concern their tourism (Cronin, Citation2011; Fälton, Citation2021; Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020; Grusin, Citation2004; Patin, Citation1999, Citation2012; Rutherford, Citation2011), while no studies have concentrated on ways of seeing within materials produced by tourists. Such studies are needed since tourists are more than just recipients of ways of seeing produced by other actors – they create and modify such themselves (Derrien & Stokowski, Citation2020; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). Such studies around the Swedish parks could broaden the understanding of the shifting times that they currently face.

Consequently, the aim of this article is to unravel, illuminate, and problematizeFootnote1 ways of seeing the non-human world that become embodied through tourists’ Instagram posts about Swedish national parks and to consider the productive effects that such posts can have on the relationship between humans and the non-human world. Empirically, it focuses on Swedish national parks by zooming in on representations of the non-human world in tourists’ Instagram posts. Instagram is a social media platform where people can communicate by uploading posts consisting of photographs and texts (Smith, Citation2018), and the analysis of these provides opportunities to identify tourists’ ways of seeing (Albers & James, Citation1983; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). One way of understanding these is to focus on representations (Berger, Citation1972; Mirzoeff, Citation2015), which are widely present in tourists’ materials (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011) and influence how people look upon the non-human world (Castree, Citation2014; Grusin, Citation2004). Therefore, the first research question is: How is the non-human world represented in tourists’ Instagram posts, and what characteristics is it assigned? Present-day representations are always historically situated and, in order to understand their context, it is essential to look at representations from the past (Burke, Citation2019; Foucault, Citation1991). Hence, the second research question is: How are the identified representations situated in historically inherited ways of seeing the non-human world? Representations also have productive effects, which means that they contribute to shaping how notions and ideas travel through space and time, but they also set the scene for what is thinkable and what is unthinkable. This can have consequences for different relations, contexts, beings, or spaces (Foucault, Citation1986), which leads to the third research question: What implications might the identified representations have for how humans approach and understand the non-human world and their own relationship to it?

Central concepts in the article

Nature and the non-human world

In this paper, the terms nature and the non-human world were used in close conjunction, and this requires a detailed account of their meanings and relationships. Within Western societies, the notion of nature has become so self-evident (Descola, Citation2013) that it is often referred to without any critical reflection or problematization (Castree, Citation2014; Cronon, Citation1995). It has also been claimed as one of modern time’s most complex words (Williams, Citation2014), which is higher up the agenda than ever before, not least due to contemporary discussions on climate and environmental change, but also in the context of nature conservation (Wilson, Citation2019). Part of nature’s complexity lies in its many dimensions, which Castree (Citation2014, pp. 9–10) illustrates in the quotation below. He writes that nature:

denotes the non-human world, especially those parts untouched or barely affected by humans (‘the natural environment’) […] it signifies the entire physical world, including humans as biological entities and products of evolutionary history […] the essential quality or defining property of something (e.g. it is natural for birds to fly, fish to swim, and people to walk on two legs) […] refers to the power or force governing some or all living things (such as gravity, the conservation of energy, the instructions contained in human DNA, or the Coriolis effect).

One type of organization that centres around nature is the national park. Since this label was launched in the United States during the late 1800s, the national park has been considered one of the most essential tools for nature conservation (Gissibl et al., Citation2012). The first parks were established to protect valuable natural environments (Grusin, Citation2004; C. M. Hall & Frost, Citation2009; Mels, Citation2002), and the Swedish ones were no exception (Mels, Citation1999). The early Swedish nature conservation debate created a strong relationship between the concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘nation’ (Olwig, Citation1995), but also ‘love’ (Ödmann et al., Citation1982), in which ‘Swedishness defined itself in contrast to the “cultural nations” of the European continent’ (Mels, Citation1999, pp. 70–71). Thus, nature was considered to be central in Sweden’s national identity and the ‘love of nature’ became one of the tourism movements’ focuses while the nature conservation movement emphasized the importance of protecting national nature. Through this, the national parks became a symbol of the Swedish nation that enabled people to get in touch with the world outside of the human realm (Mels, Citation1999). In this context ‘nature’ refers to the very first part of Castree’s (Citation2014) above-mentioned quotation about the non-human world. With its authentic and natural attributes, nature is approached as exterior to its opposition – humankind, with its artificial and unnatural attributes (Cronon, Citation1996; Descola, Citation2013; Soper, Citation1995). Like other products of environmentalism, national parks rest on the notion that nature is under constant threat from humanity and therefore needs to be protected (Rutherford, Citation2011). On the official tourist website for the Swedish national parks, they are stated to represent:

small fragments of nature that once covered all of Sweden, which makes them worthy of protection. They safeguard the diversity of ecosystems and allow tourists to enjoy natural surroundings and relax in them. They represent the most valuable nature in Sweden. (SEPA, Citation2021)

From this understanding, nature is approached as consisting of the non-human world; those landscapes, ecosystems, and physical environments beyond the borders of human societies, which are not products of humankind (Cronon, Citation1996). Separating the natural from the cultural is not unique to national parks, but is instead an established understanding that exists in different corners of human societies (Gissibl et al., Citation2012), especially Western ones (Descola, Citation2013; Soper, Citation1995). Within such contexts, nature is approached as something that is fixed and static beyond human comprehension (Chaloupka & Cawley, Citation1993). Relying on that understanding, the national parks have sprung from the nature conservation movement, where they have been approached primarily as environmental organizations, even though the operation of tourism has often been present. They have also been assigned a ‘naturalized’ role as communicators of objective facts about the natural world (Grusin, Citation2004; Mels, Citation1999; Patin, Citation2012).

Researchers taking a social constructivist approach have emphasised that the understanding of nature as static and fixed ignores its social dimensions (Wilson, Citation2019), and that how humans make meaning of nature not only tells us something about the phenomenon it has come to represent but also about ourselves and our understandings of it (Chaloupka & Cawley, Citation1993; Cronon, Citation1995). They argue that, to enable an awareness of the relationship between the human and the natural, the latter needs to be approached and problematized as something other than a naturalized world from which we are separated. This requires considering nature as a socially constructed phenomenon created by our meaning-making practices and problematizing the politics of what nature is considered to be, rather than pinpointing what it actually is (Castree, Citation2014; Cronin, Citation2011; Grusin, Citation2004; Olwig, Citation1995; Patin, Citation2012; Rutherford, Citation2011; Soper, Citation1995). A reflexive understanding of human ways of seeing the non-human world and our relation to it can be attained through such a perspective while reflecting upon the potential implications of such sense-making. This has the potential to encourage ontological discussions and reflections as well as, hopefully, more non-human-friendly actions, which are fundamental elements if we want to tackle environmental challenges (Bird Rose, Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2019). In this article, a social constructivist approach is followed, while the concept of the non-human world is used as the lens, or analytical concept, to enable an understanding of how humans construct ways of seeing a part of our world that we consider not to be part of human societies. The empirical concept that enables a grasping of such insights through tourists’ Instagram posts is nature.

Ways of seeing and the tourist gaze

Two other interlinked concepts that are frequently used in this article are ways of seeing and the tourist gaze. The first concept refers to how humans see their surroundings, which is dependent on their knowing, understandings, and worldviews (Berger, Citation1972). In contrast to approaching seeing as something objective, inborn, and connected only to the eyes, it is here approached as ‘a system of sensory feedback from the whole body’ (Mirzoeff, Citation2015, p. 14) that we as humans are taught to do in certain ways. This indicates that seeing is connected to the choices we make, but that it is also affected by what we believe in and know (Berger, Citation1972; Hooper-Greenhill, Citation2000). As Mirzoeff (Citation2015) argues, a pair of eyes is not enough to see:

The point here is that we do not actually ‘see’ with our eyes but with our brains. […] Seeing the world is not about how we see but about what we make of what we see. We put together an understanding of the world that makes sense from what we already know or think we know. (p.73)

As with the concept of ways of seeing, the term tourist gaze could be interpreted as only dealing with the eyes and the visual sense. However, Urry and Larsen (Citation2011) underline that gazing is a cognitive activity but that the visual is the main organizing sense in relation to the tourist gaze. This indicates that ‘it organizes the place, role, and effect of the other senses’ (Larsen & Svabo, Citation2014). Thus, the tourist gaze is often analytically captured through visual materials, such as photography and film. Through analyses of the tourist gaze, it is possible to trace elements of society and how they are constructed (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). When we are interested in ways of seeing the non-human world, for example, the tourist gaze is a fruitful concept that can shed light on the governance of the aspect of the world that is often called nature (Rutherford, Citation2011). As Cronin (Citation2011) underlines, ways of seeing constructed through tourism materials, such as tourists’ Instagram posts, mediate acceptable behaviours and understandings concerning the national parks and reinforce touristic assumptions about what and how the parks are. Hence, ‘proper’ ways of presenting the non-human world are created, based on discursive norms (see Foucault, Citation1982). In this article, the interest is directed towards ways of seeing the non-human world in Swedish national parks, while the concept of the tourist gaze is used to contextualize the findings.

Analytical framework and design

Tracing ways of seeing: a discursive and visual cultural focus

In order to unravel, illuminate, and problematize the ways of seeing the non-human world in Swedish national parks that are constructed through tourists’Footnote2 Instagram posts, an analytical framework, inspired by Foucauldian discourse analysis and visual culture has been designed. A discursive focus is suitable for this study because it deals with practices and their constructions of phenomena (Foucault, Citation1988; Rose, Citation2016) and offers a fruitful critical approach to tourism research and its many questions, including tourists’ ways of interpreting and seeing different phenomena (Meekes et al., Citation2020; Wight, Citation2019). In this article, discourses are understood as meaning-making assemblages of representations that give meaning to social and physical realities (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020), which means that it is within discursive fields and practices (such as tourism) that nature in the Swedish national parks is imagined, comes into being, and knowledge about it is constructed (Grusin, Citation2004). Discourses define norms and deviations in society and contour social rules by defining the borders between right and wrong, sayable and unsayable, acceptable and unacceptable, and so on. How discourses define all of these depends on the claim that a particular body of knowledge is true. Otherwise, the current discourses will lose their influential position and be replaced by others (Foucault, Citation1982, Citation1991; Rose, Citation2016). This indicates that they are saturated with power relations, that power rewards its pursuit through them, and that knowledge and power are in a position of interlinked dependence on each other (Foucault, Citation1988, Citation1991).

A difficulty with discourse analysis is the huge extent of discourses and the blurriness of their borders, making it challenging to trace them through one set of material. Because of this, the current article zooms in on their building blocks – their representations. By this term, it is referred to the process of representing and making sense of something, and the products that such a process generates. Since representations are interlinked with meaning-making processes, analysing them enables us to grasp how the non-human world is imagined, constructed, and made sense of by tourists (Castree, Citation2014; Grusin, Citation2004; S. Hall, Citation2013). This means that representations are not in themselves forms of people’s understandings and imaginations, or the social rules within societies – rather, they are generated and shaped by such, both ontologically and epistemologically. Even though this article does not set out to identify discourses on nature in Swedish national parks in themselves, it could be seen as one piece of a puzzle through which we can comprehend discourses through a focus on representations. To enable this, the social media platform Instagram, has been chosen to work with. Its posts can be seen as representative products for unravelling tourists’ ways of seeing the non-human world in Swedish national parks (see Andersson Cederholm, Citation2004). Photography, around which Instagram centres, can be seen both as a representational process and a product of such (Castree, Citation2014). It has been a fundamental activity within tourism for decades (Albers & James, Citation1983; Andersson Cederholm, Citation2004; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011), as tourists take photographs to remember, disseminate, and tell others about their experiences (Tivers & Rakić, Citation2012), but also to situate themselves and their becoming in relation to a place (Scarles, Citation2009).

Furthermore, photographs taken by tourists participate in the (re)production of tourism destinations, which makes tourists co-producers of such places (Larsen, Citation2006). This indicates that the representations on which this article focuses are of a visual character and that Instagram can be seen as part of visual culture – the ‘visual construct of the social field’ (Mitchell, Citation2005, p. 345). Based on this, the paper has been grounded in the research field of visual culture, which focuses on how the visual is part of social life (and vice versa), how visual experiences are constructed, and how ways of seeing are generated (Rose, Citation2016). As with the interest in representations within discourse analysis, a common feature within this research field is the politics of representation (S. Hall, Citation2013) and, in many cases, a visual culture approach includes an exploration of discourses as well. This paper approaches the visual as part of our societies’ discursive dimensions, which indicates that the visual is only one of the many forms in which discourses could be embodied (Rose, Citation2016). What needs to be noted, however, is that a visual culture approach is never purely visual, not least because it approaches seeing as generated through sensory feedback from the whole body. It is just that it approaches the visual as the organizing sense of seeing and focuses on the visual aspects of social life (Mirzoeff, Citation2015). For this article, it is suitable to apply a visual focus since national park tourism often focuses on visual and aesthetic characteristics of the non-human world (Bednar, Citation2012; Cronin, Citation2013; Jamal & Everett, Citation2004) but also due to the assigned centrality of visuality within Swedish national park tourism. As part of the ongoing tourism displacement, SEPA has invested in constructing primarily visual experiences, thus assigning a central role to the visual. For example, the design platform contains directives on how to frame the national parks visually (SEPA, Citation2012), and the newly installed instructive installations construct the non-human world as primarily a visual phenomenon (Fälton, Citation2021). This visual orientation is central to how depictions occur, which underlines the importance of applying a visual culture perspective to understand its aspects.

A discursive and visual culture analysis of Instagram posts conducted in six steps

There exists a myriad of different ways of doing discourse analyses, just as there is a variety of ways in which studies with a focus on visual culture are designed. However, what characterizes many of them is their openness in terms of design, meaning that they are of explorative character rather than being predetermined. This indicates that each researcher, with inspiration from previous studies rather than strict rules and orders to follow, can develop such an analysis in any ways that are suitable for them (Burns, Lester, et al., Citation2010; Burns, Palmer, et al., Citation2010; Kendall & Wickham, Citation1999; Rose, Citation2016). Grounded in this, an analysis consisting of six steps has been designed to identify representations in the Instagram posts that are suitable as empirical material for this article since they can give insights into humans’ ways of seeing and understanding certain phenomena (Leaver et al., Citation2020; Smith, Citation2018), such as the non-human world (Smith, Citation2019). Even though the work has been done exploratively to design an approach that suits the particular research context of this article, the process is in many ways inspired by the analytical steps developed in a paper by Fälton and Hedén (Citation2020) which also focuses on representations related to the Swedish national parks and ways of seeing the non-human world. Its’ design (which contained four steps) enabled a detailed and broad tracing of representations and their productive effects, which are central components of this study. Here, it is of interest to capture both details and a broader pattern. Because of this, not only Instagram posts (consisting of one or several photographs with accompanying text) have been analyzed in their original shape, but their photographs and captions have also been analysed separately. The reason for this is that, even though they are presented in the same post, it is possible that the photographs and the texts do not contain the same representations. Mitchell (Citation1996, p. 49) has compared the relation between the two with the relationship between two countries ‘that speak different languages but that have a long history of mutual migration, cultural exchange, and other forms of intercourse’. Thus, separating the two enabled an identification of different representational patterns among them and potential similarities and differences between them (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020).

Step 1: collection of empirical material

Firstly, Instagram posts featuring all of Sweden’s 30 national parks were collected and saved in a closed online storage space. Even though Instagram could be understood as a public online forum (Kozinets, Citation2015; Lehner-Mear, Citation2020) and all the posts were collected from open-access accounts, they have been stored in such a way that no one else could access them. Since this article focuses on the national parks as a united body, rather than characteristics of individual parks, all 30 of them were considered to collect Instagram posts in order to capture a broad picture. The posts were found through searches for hashtags with the parks’ first names, followed by ‘nationalpark’ (e.g. #abiskonationalpark). All names of the parks in Sweden end with the phrase ‘nationalpark’, but some parks (e.g. Ängsö National Park) share their first names with other places in Sweden. By including the phrase ‘nationalpark’ in the searches, it was made sure that the collected posts concerned the national parks. Initially, the idea was to compare such hashtags with ones stating the first name only (e.g. #abisko) to identify any differences. However, it soon became apparent that most of the posts used both kinds of hashtags, indicating that the majority of them shared similar content. Some tourists might have used hashtags with the first names of the parks only, which means that a limitation of this article is that those exist beyond the scope of the collected empirical material. However, the collected posts were sufficient to conduct the analysis. Twelve posts from each park were randomly collected and it was made sure that they were uploaded by visitors to the parks and not by companies, national park staff, or other organizations. In total, 360 posts collected that were published during the period 2018–2020.Footnote3 Another limitation regarding the collection of empirical material is that it was unknown whether the persons who uploaded the posts actually identify themselves as tourists or see themselves as local recreationists. There might be some differences between the two groups’ ways of seeing, which could have been interesting to raise. Hence, this is a potential topic for further studies to deal with.

Step 2: exploration of representations in photographs

Since the visual aesthetics of Instagram focuses on photographs (Leaver et al., Citation2020), the analysis was initiated through a focus on the visual and discursive themes of the representations that could be found among the photographs. Paying initial attention to the photographs also corresponds to and underlines the increased role of the visual in modern societies, where visual experiences are on the agenda more than ever before (Mirzoeff, Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2005; Rose, Citation2016). Furthermore, tourism studies have traditionally favoured textual empirical materials over visual ones (Balomenou & Garrod, Citation2019) and starting the analysis with the photographs empowers their role as empirical materials containing representations that do not need to be interpreted with the help of an attached text (Burke, Citation2019; Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020). First, the photographs were divided into 30 collages (one for each park) and taken to The Norrköping Decision Arena (), which is a facility with a wraparound cylinder-shaped screen that enables its users to project the content from ten computers onto the screen simultaneously (Linköping University, Citation2020). By projecting several collages simultaneously, it was possible to get immersed by in the photographs and relate them to each other (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020) over the course of three sessions.

One reason for using the Norrköping Decision Arena was to elaborate on new ways of organizing an analysis of a large number of photographs and to see if any novel opportunities with using it could be discovered. Other ways of organizing such analysis could be to print several photographs and place them on a table or wall, or to look at several photographs on a single screen. After using the arena, it was concluded that it is easier to practically analyse and keep track of the analysis when working with a greater number of photographs than when printing them or looking at a single screen. The arena’s wraparound screen enabled a projection of a large number of photographs in high resolution simultaneously as it was possible to zoom in on details, zoom out, walk around or sit down while always having the photographs at a comfortable eye level, and change the orders of the collages with one single click. All of this gave a sense of being placed in the middle of the empirical materials, and it was much easier to work with multiple juxtapositions to identify patterns and recurring themes. Even if printing photographs or using a single screen also would offer some of the mentioned components, none of them provide all at the same time, which the arena does. Therefore, the arena is here understood as a tool that made the organization of the analysis easier.

During this step, the photographs led the analysis in different directions rather than them being approached with a preformulated set of questions and themes (see Foucault, Citation1982). The analysis was documented through notes of the empirically grounded interpretations of representations. Even though all the parks were treated as a united body rather than as individual venues, an investigation of their individual characteristics was also enabledby dividing them into one collage per park. But it was soon realized that their representations were highly homogeneous. This is interesting because it illustrates a cohesive portrayal of the parks, which would not have become visible without dividing the photographs into collages.

Step 3: exploration of representations in texts

After the session in the arena, the written texts were analysed in a similar manner to identify representations among the tourists’ descriptions of their photographs. As with the photographs, the texts were approached with no predetermined questions or themes. Instead of confirming the representations identified during step 2, the focus was on scrutinizing what discursive themes of representations could be located among the texts themselves. Therefore, they were approached with ‘fresh eyes’ (Rose, Citation2016) and were not compared to the photographs. The texts were organized in a Word document, with all the texts belonging to a specific national park assembled under one heading. Once again, this division was made to enable the identification of differences. However, as with the photographs, the representations proved to be of a homogeneous character. To document the analysis, different colours were used to ‘code’ the identified themes.

Step 4: merging and deepening of Steps 2 and 3

After completing steps 2 and 3, the identified representations were compared to each other and no major differences between the photographs and the texts were noticed. Based on this, the interpretations of them were merged by conducting another round of analysis in which the texts and photos were scrutinized in their ‘original shape’ (i.e. not as collages but as photographs with textual descriptions). This means that one post at a time was analysed and that depictions of the representations identified during steps 2 and 3 were searched for in order to immerse, link, and consolidate them. In other words, the previously identified representations were used as a starting point to gain a more nuanced picture of them. Situated examples and embodiments of representations were searched for to deepen the understanding of their expressions by merging observations and interpretations from the previous steps. To document this, different colours were used for coding the texts and notes were taken concerning the photographs.

Step 5: identification of ways of seeing, selecting examples, and relating the analysis to historically inherited representations

As a fifth step, the interpretations from steps 2, 3, and 4 were brought together and five ways of seeing were identified. These represent the final organisation of the results and are entitled: (1) A sublime scenery of grandeur and beauty; (2) An uncivilized wilderness of desolate character; (3) A challenger demanding physical performances; (4) A treasury with collector values filled with animal tokens; (5) A unique place with iconic attributes. The order in which they are presented is not based upon any quantitative considerations. Instead, they should be seen as approximately equally prominent within the empirical material.

To contextualize and understand the origins of the identified representations, they were related to historically inherited representations of the non-human world identified in previous research on touristic ways of seeing this world. Another important aspect was selecting example photographs and quotations that mirrored the materials’ central representations. The use of detailed visual and textual examples is vital to support the analysis and enable a reflexive presentation of it, whereby the reader is invited into parts of the material in order to better understand how interpretations and conclusions have been drawn (Rose, Citation2016). Even though Instagram could be seen as an open-access online forum where the users can be identified (Lehner-Mear, Citation2020), To aviod unwanted publising that may cause harm or discomfort to the tourists who had published the posts, it was assured that the examples used were based on consent from them (e.g. Kozinets, Citation2015; Lehner-Mear, Citation2020). Therefore, only full quotations and photographs have been used when consent has been given. In cases where it was not possible to contact the tourists, their posts have been described instead of using their photographs or full quotations. In this way, unwanted identifications of tourists through this article have been avoided (see Charlesworth, Citation2008).

Step 6: identifying potential implications and reflecting upon what kinds of tourist gaze the ways of seeing construct

In the final step, It was reflected upon that what kinds of tourist gaze were generated through the identified representations and ways of seeing. One part of this consisted of reflecting upon the potential implications they could have for how the non-human world is understood and approached. Such reflection is an essential component in understanding human ways of seeing the non-human world (Grusin, Citation2004; Patin, Citation2012; Rutherford, Citation2011) but also its underlying discourses and their productive effects, which are products of the interrelationship between power, knowledge, and truth (Rose, Citation2016).

Meta reflection on analytical framework

Like other research articles, this one is influenced by the ontology and epistemology of the person who has designed it. Within the spectrum of tourism research, there exists a myriad of different ontologies and epistemologies, but also analytical approaches. The one applied here is influenced by an understanding of the world as socially constructed and an interest in researching ways of seeing different phenomena (in this case, the non-human world). This article's analytical approach is inspired by visual culture and Foucauldian discourse analysis, which set the tone of the analysis. This inspiration provides an analytical gaze that encourages a focus on visual dimensions and problematizations while not approaching research as truth or universal. Here, one interpretation of a particular phenomenon is provided, where an analysis based upon the methodological and analytical components just described is presented (see Castree & Braun, Citation1998; Demeritt, Citation2006; Jamal & Everett, Citation2004). One potential implication of this analytical framework and argument about research being everything but the truth might result in the findings of this article being seen as less valid or trustworthy than other research since such statements contrast towards norms of research as objective and truth-producing (Demeritt, Citation2006; Ekström, Citation2004). This underlines the importance of designing and providing a transparent article where central analytical concepts, the design and practical operationalisation of the analysis are described, but also where empirical examples are provided to justify the interpretations (Jameson, Citation1994). Not least since there are many ways in which the material of this article can be interpreted. Here, one such version is presented.

Unravelling the ways of seeing the non-human world in Swedish national parks through tourists’ Instagram posts

Seeing the non-human world as a sublime scenery of grandeur and beauty

The first set of representations in tourists’ Instagram posts centres around seeing the non-human world as primarily a sublime sphere that is characterized by the grandeur and the beauty of its scenery. Here, nature is assigned awe-inspiring features, where, similar to paintings, it is depicted as something that primarily should be gazed upon with awe and reverence. Panoramic photographs of expansive landscapes are everywhere in this empirical material, such as in from Stora Sjöfallet National Park, where the grand mountains and dramatic weather are in focus. Related to this photograph, the tourist who posted it, Robin, used hashtags such as #beautifuldestinations, #artofvisuals, #nature_perfection, and #world_bestnature, which all emphasize the beauty and grandeur of the non-human world.

Such representations of beauty and grandeur can be seen in relation to national parks all over Sweden, although there is a slight overrepresentation of the northern ones. Their captioning of the non-human world as a painting that seeks to please the eye of the beholder relates to picturesque ways of seeing this world that can trace their roots back to the landscape art of the 1700s (Erlandson-Hammargren, Citation2006; Jensen Adams, Citation2002). Anchored in this tradition, tourists of the 1800s and early 1900s focused on gazing towards grand scenery (often in the north), while viewpoints became one of that time’s most popular tourist attractions and the non-human world a resource for both aesthetic and emotional experiences (Andolf, Citation1989; Johannisson, Citation1984; Löfgren, Citation1989). This focus on the non-human world as something that should be gazed upon due to its grandeur, beauty, and dramatic attributes are classical features of the sublime (Corbett, Citation2002), which evokes a sense of awe-inspiring immensity or greatness, where feelings of being overwhelmed occur among its viewers. Such portrayals have been part of tourist experiences since the rise of consumer travel (Bell & Lyall, Citation2002), but became thoroughly established in Sweden during the 1800s as a romanticism for the northern Swedish landscape and its mountains became rooted in tourist discourses (Erlandson-Hammargren, Citation2006).

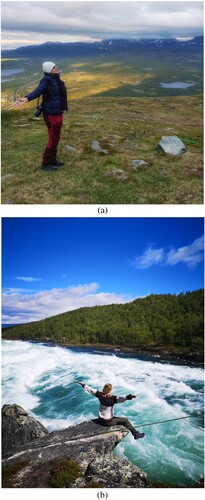

Another kind of sublime photograph that is common among tourists’ Instagram posts are those in which a lone tourist can be seen gazing towards the scenery, exemplified by , from Björnlandet National Park. The photograph’s expansive view is reinforced by the tourist standing on the edge of the cliff, and it seems as though all that exists are the tourist and the remarkable wonders of the non-human world. Photographs of this kind, in which a person stands away from the camera and gazes off into the landscape stretching into the distance, are typical features of sublime portrayals with an emphasis on beauty (Corbett, Citation2002). Besides indicating that the non-human world should be gazed upon and amaze tourists with its vast panoramas, these kinds of photographs could be interpreted as emphasizing humans’ littleness within it (Johannisson, Citation1984). According to Smith (Citation2019), who has analysed how ideological representations of landscapes are installed and construct the self in tourists’ Instagram posts, these kinds of photographs are common on Instagram. He argues that, however innocent and focused on aesthetics they might appear, they are remnants of how the early colonial travellers of the 1800s were portrayed in paintings. They were often positioned in the foreground, where they had an elevated position in relation to the landscape, and stood with their backs turned to the viewer.

Similar reflections have been made by Pratt (Citation1992) and Urry and Larsen (Citation2011), who argue that such representations could in one sense be seen as a way of expressing domination over and possession of the non-human world. However, Smith (Citation2019) explains that ‘Today’s tourists purport nothing like the kind of dominance envisaged by nineteenth-century European explorers, but the composition of the promontory witness nonetheless draws upon historically entrenched significations of possession’ (p. 5). Thus, these kinds of representations have a long history within the practice of tourism. In the empirical material, they take on yet another variation, with a focus on showing reverence towards the grand scenery. (a,b) has several characteristics in common with , but there, the tourists are not ‘only’ gazing towards the scenery but are also reaching their arms out to show their reverence. Moa, who took the photograph on the right, writes: ‘Thank you, life, earth, and nature – you are so powerful!’ [author's translation] and underlines her gratitude by using the hashtag #tacksamhet [#gratitude].

Figure 4. (a and b). Copyright left: Pia Löfgren (@pialohf), copyright right: Moa Harryson (@lyckligochlevande.nu).

Feeling connected to a place that is considered important to the individual has been identified as part of tourists’ recreational experience values in relation to Swedish national parks. This is just like seeing dramatic landscapes, spectacular views, and the scenic quality of nature (Raadik et al., Citation2010), which are all part of the representations of the sublime in the empirical material. However, even though aesthetic attributes are most prominent, the sublime is more complex than that, as the words of yet another tourist illustrate. Regarding a similar photo to the ones just presented, she explains a perceived admiration for the non-human world by describing how one of the Swedish national parks made her cry because of its beauty. She declares the park to be one of the most beautiful and heart-touching places she has visited in Sweden and explains how several feelings grew inside of her during her visit – making her feel both happy and touched at the same time.

Thus, the sublime evokes a palette of multi-sensory qualities simultaneously. As a category of beauty, it denies proportions and symmetry while combining aesthetic and emotional experiences (Johannisson, Citation1984): the littleness of humanity meets the vastness of nature; the dizzying meets the thundering, the tremendous meets the obscure, and so forth. By triggering several experiences in parallel, these characteristics awaken various feelings inside the human body and endorse a sense of insignificance (Brady, Citation2014). However, one thing that is surprising concerning the sublime representations in the tourists’ Instagram posts is the invisibility of depictions of danger, where the non-human world is portrayed as an evil foe. Such depictions of the sublime have been a central part of how the non-human world has been represented since the late nineteenth century (Ödmann et al., Citation1982) and also play a major role in contemporary tourist information publications about the Swedish national parks (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020).

Seeing the non-human world as an uncivilized wilderness of desolate character

The second set of representations centres around seeing the non-human world as wild, desolate, and pristine. These representations share several features with the sublime ones, but place a stronger emphasis on the non-human world as ‘untouched’ and original, rather than grand and beautiful. One tourist writes that one national park offers the rare opportunity to get a sense of wilderness, while another (@pavel.shyshkouski) says that ‘Nothing regenerates better than a week’s walk far from civilization’, while Moa, who took the photograph in (b), writes: ‘Among the inaccessibility and Sweden’s wilderness, in the middle of wild rapids, high alpine mountain peaks, and lots of glaciers. […] Sweden’s real wilderness gives more flavour, and I will return here to regain strength again’. [author's translation]. Such expressions exemplify the approach to the non-human world as free from any human presence, not least through the use of words such as ‘wild’ and ‘wilderness’. In a Western context, the concept of wilderness has come to stand for ‘the last remaining place where civilization, that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth. It is an island in the polluted sea of urban-industrial modernity, the one place we can turn for escape from our own too-muchness’ (Cronon, Citation1996, p. 69). Photographs depicting the non-human world in Swedish national parks as ‘empty’ of human signs is common in the empirical material, as exemplified in . The photograph depicts a sleeping bag and a camera directed towards the sun as it is about to set over the archipelago, and it seems as though the photographer is lying in the sleeping bag. Apart from the camera gear, there are no other visible signs of humanity. This is reinforced in the description of the photo. Daniel, the photographing tourist, writes ‘Under the clear skies in the Swedish arcipellago. Just me, my sleepingbag and my two timelapsing cameras! On the other side of the water in the picture is one of the oldest national parks in Sweden, Ängsö [sic].’

According to Munar et al. (Citation2021), who have analysed Instagram images shared by pilgrims in order to understand their existential walking, representations of the non-human world where contemplation, the immensity of nature, and the lack of social activity are the primary focus evoke existential questions about who we are in this world. Thus, they depict a kind of existential loneliness that invites the viewer of the photograph to contemplate the visiting tourist as alone in the non-human world. Photographs of this kind are typical in the empirical material, and surprisingly few capture how crowded a day in one of the parks can actually be.

Approaches to nature as untouched by humans are common within contemporary tourism in general. The fewer people there are at a site, the more it is seen as unpolluted and unspoiled (Salazar & Graburn, Citation2014). According to Smith (Citation2019), photographs representing pristine characteristics are common among tourists’ Instagram posts, while pictures of the crowds queuing to take a photograph of the same view are almost never posted. Such depictions are probably absent because they collide with tourists’ imaginaries of how the national parks ‘should be’ – pristine, with no signs of humanity. This corresponds to the preferences for recreational experiences of tourists in Swedish national parks, where seeking solitude in primitive environments has been identified as central (Raadik et al., Citation2010). Thus, the representations’ focus on manufacturing pristine characteristics and situating tourists as alone assigns them a privileged role as unique consumers of the non-human world (Smith, Citation2019) and emphasize that the national parks enable tourists to connect with the non-human world (and themselves), but certainly not with other tourists.

In this way, understandings of nature as separate from humans and their ordinary lives are signified (Johannisson, Citation1984), but also an understanding of national parks as portals enabling tourists to interact with the non-human world. Like the sublime representations, these are also remnants of ways of seeing nature that emerged during the 1800s, when stressed city dwellers travelled to natural settings to escape from the stresses that modern society imposed on them (Erlandson-Hammargren, Citation2006). But they are also common in contemporary discourses on tourism practices, such as ecotourism (Fletcher, Citation2014). As can be seen in the empirical material, one central characteristic of these settings is that they are freed from human presence and are as ‘pristine’ as possible. Throughout history, wild and pristine features have attracted tourists to nature destinations (Oravec, Citation1996), and Swedish national parks are no exception. Tourism information publications use such framings (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020) and, as shown here, tourist representations maintain them too. In one description, a tourist writes that nature in the heavily wooded Norra Kvill National Park has been left untouched by man during the last 150 years, which enables tourists to grasp the beauty of nature. Another tourist pays tribute to national parks for protecting fragile and valuable natural areas.

Such understandings, which often rest upon anxiety about environmental change, are common among national park tourists. Through visiting the parks, they hope to get in touch with a piece of pure wilderness and escape from its nemesis – humans (Rutherford, Citation2011). However, one interesting component is that, despite critical undertones towards humanity and its modern practices in tourists’ Instagram posts, no tourists reflect upon their own impact on these areas. Even though tourists’ exploitation is not as physically damaging as logging, it still has an impact on the non-human world, making it essential to problematize (Tschida, Citation2012). These representations relate to an increasing trend within tourism, where destinations considered to represent ‘the wild’ become an antidote to modern industrial life. In their pursuit of being more environmentally friendly, an essential component for tourists is going there as tourists and thereby contributing to the desire to preserve those spaces (Fletcher, Citation2014). Thus, ‘a trip to the wilds of nature is recast as a form of activism’ (p. 187) that offers tourists the opportunity to experience pieces of nature that they fear will soon be lost (Rutherford, Citation2011).

Seeing the non-human world as a challenger demanding physical performances

The third set of representations constructs ways of seeing the non-human world as a challenger requiring physical performances. It relates to both the sublime and uncivilized representations. This is primarily embodied through depictions of hiking, which is stated as an important activity for tourists. Besides being an activity that many tourists engage in, hiking is depicted as something that challenges them and enables a specific relation to the non-human world – an evolving one. In relation to a photograph of a group of hikers taking a break in the midst of the mountains of Abisko National Park (), one tourist, Sonny, writes ‘There is only one way, and that is forward’ [author's translation] followed by hashtags such as #hiking, #storm, #fighting spirit, #energy, #maximized, and #jävlaranamma. The latter is a Swedish word meaning that someone has plenty of backbone, and does not give up when faced with challenges.

Another tourist describes how her hike took on several expressions simultaneously. It offered her beautiful views but was also demanding and long (with an emphasis on long). In other words, these posts portray hiking as an activity that requires great desire and strength, as it challenges the hikers with bad weather and steep slopes. Interestingly, there is a difference between the photographs and texts, with the texts describing the difficulties of hiking, while the photographs make such components invisible and instead focus on its ‘golden moments’. The majority of these photographs portray happy tourists hiking in grand landscapes with sunny or slightly cloudy weather, and a common depiction is tourists standing on mountain tops with their arms in the air, as a way of saying ‘we did it’ (). This kind of photograph relates to Smith’s (Citation2019) argument that tourists seek to share photographs on Instagram that demonstrate accomplishments. In this way, they contribute to upholding the desire to conquer that arose among the explorers of the 1800s. Back then, the fascination with the non-human world was anchored in performance needs as it was prized for its opportunities in challenging tourists. Thus, a battle between tourists and the non-human world became prominent, where tourists’ goal was to ‘defeat nature’, or become victorious within it by testing their capacities through engaging in brave and challenging adventures (Fletcher, Citation2014; Zweig, Citation1974). A central activity was mountaineering, described as the pinnacle of many tourists’ travels to the northern national parks (Andolf, Citation1989; Erlandson-Hammargren, Citation2006; Fletcher, Citation2014; Johannisson, Citation1984; Ödmann et al., Citation1982). Through such depictions, the non-human world becomes represented as triggering physical challenges and something that must be defeated (see Johannisson, Citation1984). Even though the representations of today’s tourists do not focus on defeating the non-human world per se, they portray it as an arena where the tourists can challenge themselves. Challenging oneself and developing a sense of self confidence while engaging in adventurous discovery and a physical challenge are components that have been identified as central for tourists in Swedish national parks (Raadik et al., Citation2010).

Seeing the non-human world as a treasury with collector values filled with animal tokens

The fourth set of representations of the non-human world portrays it as a treasury filled with hidden riches waiting to be discovered. In one way, the act of taking photos in the national parks could be understood as a way of documenting memories and ‘collecting’ tokens, thus rendering the non-human world into a space of souvenir character (see Berger, Citation1972; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). As has become visible through the representations described above, photographs capturing grand vistas are common in the empirical material and exemplify the tourism industry’s focus on consuming landscapes (Bell & Lyall, Citation2002). In addition, tourists are also on the hunt for photographs of non-human ‘bargains’, such as animals (or traces of them). The empirical material is filled with photographs of animals, such as from Fulufjället National Park. Sune, who took the photograph, writes ‘Lavskrika/Siberian Jay. ☺’ in the caption to explain what kind of bird it depicts. He also uses several hashtags that underline the activity of taking photographs of birds: #fågelskådning [birdwatching], #fågelfoto [bird photo], and #fågelfotografering [bird photography].

Lemelin (Citation2006) has analysed the tourist gaze in relation to polar bear tourism in Canada. He explains that many tourists are more focused on listing what animals they have seen by taking photographs of them than they are in the actual viewing experience itself. Since tourists were not interviewed, any statement regarding whether this applies to the collected empirical material cannot be made. However, it can be said that taking photographs of animals seems to have major entertainment value for tourists and that their representations express a longing to interact with, or encounter, animals. Some of the Swedish national parks are well known for their wildlife, and in many cases, the dissatisfaction of not seeing a characteristic animal is expressed. For example, among the posts from Björnlandet National Park, which in Swedish means ‘Bear Country National Park’, several texts describe the desire to spot a bear but also that it never happened. The longing to encounter animals is typical within nature-based tourism (Bertella, Citation2016; Rutherford, Citation2011), and national parks are no exception. Interactions with animals have been part of national park experiences since the early 1900s. In Canadian parks of that time, the promoters encouraged tourists to interact with animals and many early twentieth-century tourist photographs depict tourists petting and feeding animals such as bears. This is an activity that today is considered dangerous, but still, national park tourists long to encounter animals (Cronin, Citation2013). In particular, they want to immortalize such meetings by taking a ‘good’ photograph of the animal and bringing it home with them as a memory to show family and friends (Lemelin, Citation2006).

Despite the expressed desire to see animals in the empirical material, such encounters are not always possible. In such cases, the discovery of animal traces seems to be an important activity among Swedish national park tourists. One tourist describes a situation in which both exciting encounters with forest birds and the discovery of bear traces in the form of droppings were part of the experience. Even though she did not actually see any bears, she underlined that finding the droppings reinforced their presence. In the empirical material, there are also photographs representing tourists who are holding, standing next to, or placing their hands beside such traces. In , from Stora Sjöfallet National Park, a person can be seen holding a reindeer antler. In contrast to many of the photographs presented above, this one focuses in tightly on the detail, with the surrounding landscape becoming blurred. It illustrates a closeness between the human body and the non-human world, but could also be interpreted as an invitation to notice things in the surroundings and to open up other senses than the visual (Munar et al., Citation2021).

Wesley, who took the photograph, writes:

I love the 70-200 lens for shots like these. I’ve always somehow liked this composition; a person holding up something in front of the camera. It creates this kind of ‘in your face’ feeling and you just have to look at what it is. In this case it’s horns from a reindeer. They just drop them every now and then, so don’t worry, no animals were hurt in the making of this picture!

Approaches to the non-human world as a treasury emerged during the 1500s and reached its culmination at the end of the nineteenth century, as the fascination with ‘Norrland’ (the northern parts of Sweden) emerged. However, the treasures of that time had other characteristics than those visible in modern Instagram posts. For example, attention was directed towards raw materials that could be extracted and used within different industries, with peat and iron ore at the top of the list (Erlandson-Hammargren, Citation2006). Even though contemporary tourists are not searching for tokens with extraction value, their pursuit of animal encounters and their desire to visit as many national parks as possible can still be interpreted as a kind of treasure collection, in which the non-human world becomes the treasury and the tourists its explorers.

Seeing the non-human world as a unique place with iconic attributes

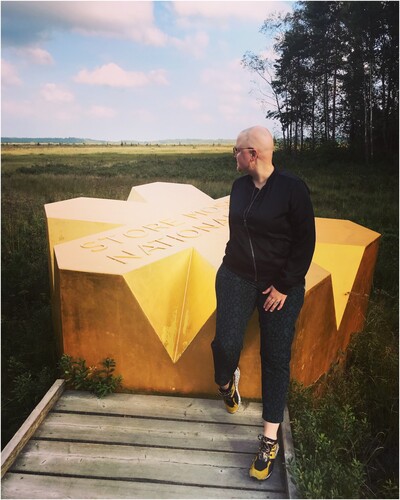

The fifth and final set of representations constructs ways of seeing the non-human world in Swedish national parks as unique. For example, in relation to Djurö National Park, Denny Mattson (@dennyswalkabout) writes, ‘The sunsets, sandy beaches, cliffs, warm weather, and views make it a unique place’ [author's translation]. In relation to Björnlandet National Park, Sirpa Pörhönen (@sirpafinnen) writes: ‘If you want to soak up the unique atmosphere of the primeval forest, this is a perfect place♥’ [author's translation]. Even though tourism was not prioritized in relation to Swedish national parks during the majority of the twentieth century, the approach to them as unique places featuring exceptional nature has been strong since the first parks were established. One of the first ones, Stora Sjöfallet National Park, was described by its founders as the site of Sweden’s most beautiful and unusual waterfall, which was also the reason why that area became a national park (Lundgren, Citation2009). Today’s tourist representations approach the national parks in a similar manner and emphasize their unique features. In the Instagram posts, the presence of one particular object reinforces this – a three-dimensional version of the national park crown symbol, visible in photographs from national parks all over Sweden. Tourists can often be spotted posing in front of, on, or in close relation to these crowns, as in . With their crown shape and shining golden colour, these massive objects are often placed close to some of the parks’ main attractions or places that illustrate their uniqueness. Through these, SEPA wants to make tourists aware that they have come to the most delicate nature available in Sweden, and the intention is to put one crown in each park (SEPA, Citation2018).

The crown in is placed in front of the main attraction in Store Mosse National Park – its great marsh area. By situating the tourist next to the crown, these types of photographs visually highlight that ‘I was here’ and emphasize the national parks’ status by assigning the crown a central role. In contrast to photographs where the situating of the tourist excludes destination attributes and focuses on the capturing of the self (Christou et al., Citation2020), this photograph focuses on the relation between the tourist, the crown, and the marshland in the background. This is reinforced by the way in which the tourist is gazing towards the marsh, which is reminiscent of several of the photographs in relation to the sublime representations. SEPA’s intense work to establish the crowns as visual markers for the national parks’ unique values makes them iconic place stamps rather than pointers towards each park’s specific features.

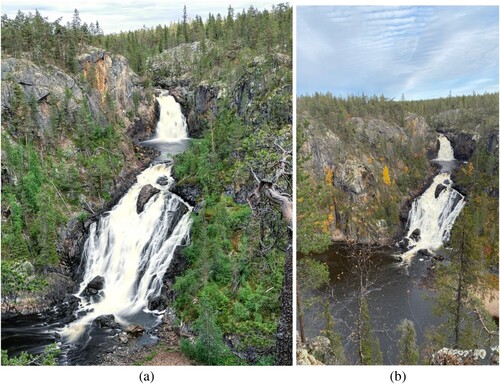

Such attributes are also assigned to particular places in the parks. While scrolling through tourists’ Instagram posts, it soon becomes evident that they often portray the same views, which become iconic places with enhanced visiting value through this repetition. Frequently, tourists tend to photograph views emphasized in tourism information publications, such as Muddusagahtjaldak/Muttosfallet waterfall in Muddus/Muttos National Park ((a,b)). This is a common phenomenon within tourism and could be understood as the ‘hermeneutic circle’, in which tourists travel to and take photos of vistas that they have seen on different media. Visiting outlooks to achieve visual experiences is a major attraction for contemporary tourists (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011), but it is a touristic activity that can be traced back to the late 1800s when the visual admiration for the non-human world first began to grow (Andolf, Citation1989; Johannisson, Citation1984; Löfgren, Citation1989).

Figure 11. (a and b). Copyright left: Anton Blomstam (@antonblomstam), copyright right: Jonas Sandberg (@vergilius_).

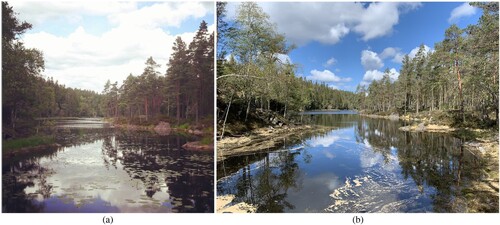

However, several photographs depict vistas that are not explicitly visible in marketing materials, such as the lake in Tresticklan National Park in (a,b). Out of twelve collected photographs from that park, two depicted the same site. While scrolling through Instagram to see if it was only a coincidence, the exact same view was visible in many photographs. Thus, it seems as though tourists are inspired not only by pictures marketed by tourism actors, but also by iconic sights that other tourists have captured and shared via Instagram. Thus, being a ‘typical’ tourist in a Swedish national park equates with knowing how to capture and communicate the ‘itness characteristics’ of the non-human world through photography (Rutherford, Citation2011).

Figure 12. (a and b). Copyright left: Igor Willems (@igorwillems), Copyright right: Julien Wilmotte (@wiracocha7).

By identifying iconic places and steering tourists’ attention towards them, these photographs influence which places become famous. Through tourists’ search for monumental and iconic sights, paths are created within the nature tourism industry – tracks for future tourists to follow (Ehn et al., Citation1993). In other words, these kinds of photographs can be seen as a way to demonstrate that the tourists really have visited an iconic place and want to share their story of being there (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). Something that further reinforces the national parks’ portrayal as unique is the invisibility of utility-oriented interactions with the non-human world. Picking berries and mushrooms or catching fish for dinner are three examples of activities that many Swedes use their ‘local nature’ for (Lindhagen & Bladh, Citation2014). The invisibility of such activities creates a separation between ‘everyday-related’ nature and the exclusiveness of the national parks, in which the ordinary has no place. Portrayals of uniqueness are visible in tourism information publications too (Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020), but in contrast to tourists’ Instagram posts, they also offer a dimension of the national parks as ordinary.

Concluding remarks: the construction of a romantic tourist gaze that sees enclaved havens

By focusing on representations of the non-human world in Swedish national parks that become visible through tourists’ Instagram posts, ways of seeing the non-human world have been traced. Based on the interpretative approach influenced by visual culture and Foucauldian discourse analysis, but also the interest in ways of seeing the non-human world and the tourist gaze, five ways of seeing have been identified: (1) seeing the non-human world as a sublime scenery of grandeur and beauty, (2) an uncivilized wilderness of desolate character, (3) a challenger demanding physical performances, (4) a treasury with collector value filled with animal tokens, and (5) a unique place with iconic attributes. All of these, as have been illustrated, are situated within historically inherited ways of seeing the non-human world and relate to contemporary representations identified in other studies of Swedish national parks.

When putting the bits and pieces of all this together, it can be contended that the five identified ways of seeing the non-human world with belonging representations correspond to what Urry and Larsen (Citation2011) have recognised as a ‘romantic tourist gaze’. This gaze springs from the Romantic movement of the late 1700s and early 1800s, when a focus on emotion, sensation, and poetic mystery arose (Feifer, Citation1985). Today, this gaze is well-established in tourism marketing within Western societies (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011) and not least in relation to nature-based tourism (Fletcher, Citation2014; Karlsdóttir, Citation2013). At its core lies the search for an experience of the sublime aspects of unique and pristine wilderness, where wild animals roam, there is plenty of beautiful scenery, and opportunities to enjoy the health-giving properties of nature and collect memories abound. It also includes a desire to experience all of this in solitude, far away from the arenas of mass tourism (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011).

As became visible through the example photographs, with their absence of other tourists, all of the identified ways of seeing in this paper portray the non-human world as something that should be experienced without the presence of other people. This was especially visible in the representations of the non-human world as an uncivilized wilderness of desolate character. Besides focusing on being alone, this way of seeing also relates to the search of the romantic tourist gaze for ways to experience pristine wilderness. Experiencing the wild characteristics of nature without the presence of other tourists is an essential element of the romantic tourist gaze, since it is considered to offer a more personal relationship with the non-human world than when other humans are present (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). This way of seeing embodies two very typical dichotomies within Western societies: that between ‘wilderness’ and ‘civilization’, and that between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ (Castree, Citation2014; Cronon, Citation1996). Here, the non-human world in the Swedish national parks becomes represented as spaces to which tourists can ‘escape’ from civilization and get in touch with themselves and the non-human world. Such an escape is a central feature of the romantic tourist gaze and is considered to ‘be good’ for tourists living in industrial and modernized societies (Drennig, Citation2013; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). However, the visiting tourists are assigned a subject position of being detached and temporary guests in the spaces of the non-human world (see Foucault, Citation1982), which underlines a sense of otherness resting upon the notion of an ‘us’ and a ‘them’ (Said, Citation2003) and leads to a distanced relationship between the human and non-human worlds.

Even though nature conservation and tourism in national parks focus on enabling people to visit places that are considered to host pieces of valuable nature and thereby to get them interested in nature conservation (Fälton, Citation2021), the representations’ strong emphasis on approaching nature and humans as set apart from each other run the risk of making people feel disconnected from the non-human world. This could make it more difficult for them to notice the importance of taking non-human beings and environments into consideration and result in them only placing the human world at the centre of attention (Bird Rose, Citation2015). Together with representations of the non-human world as unique and a focus on exotic experiences (e.g. seeing a bear or ‘real’ pristine nature), these understandings turn the non-human world into an exotic wonderland far removed from the tourists’ home environments. Furthermore, the focus on consuming the ‘unique’ aspects produces hierarchizations between different spaces and means that the non-human world in Swedish national parks appears as a counter-site to the tourists’ everyday spaces (see Fälton & Hedén, Citation2020; Foucault, Citation1984; Hetherington, Citation1997) that needs to be explored and experienced. This turns it into a spectacle for humans to be amazed by, observe, and explore (Cronon, Citation1996; Foucault, Citation1991; Smith, Citation2019). This is reinforced through bucket lists, the desire to take photographs of known tourist places and animals, and also through the collection of animal tokens as souvenirs. Thus, the representations’ firm focus on communicating the non-human world as a space created primarily to facilitate tourists’ experiences turns it and its inhabitants into touristic products (Fletcher, Citation2014; Rutherford, Citation2011) and commodified phenomena existing out of the ordinary, almost as representatives of enclaved havens (see The ‘Carceral Archipelago’ in Foucault, Citation1991).

When the search for pristine, wild, and unique characteristics emerged during the Romantic Movement of the late 1700s, tourists were also on the hunt for ‘that kind of beauty which would look well in a picture’ (Ousby, Citation1990, p. 154), and up until today, such a hunt is still one of the main components of being a tourist (Bell & Lyall, Citation2002). As became visible in the findings, feeling emotions and sensations inspired by the grand non-human world and its beautiful scenery is a central part of the representations in tourists’ Instagram posts. The focus on aesthetics and the sublime are two of the cornerstones of the nature conservation movement (Drennig, Citation2013; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011). This becomes visible not least through its focus on establishing national parks – some of today’s symbols of sublime-inspiring spaces (Bilbro, Citation2016). Focusing on the grandeur and beauty of the non-human world may, as became visible through some of the identified representations of this paper, lead people to feel humility and gratitude towards that world. However, the sublime’s focus on gazing towards and capturing the grand and beautiful from afar can also reinforce a perception of humans as separate from the non-human world (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011) and contribute to making the non-human world a spectacle for tourist to commodify.

When Romanticism emerged, there was a focus not only on experiencing scenic views but also on the health-giving properties of nature. During that time, sea bathing became popular because it was considered to presume healthiness (Hern, Citation1967). Today, hiking in nature holds a similar status and is frequently highlighted as a healthy activity to take part in, not least within the nature-based tourism industry (Rogrigues et al., Citation2010). Thus, the focus on engaging in physical challenges through hikes in the non-human world of the Swedish national parks could be seen as today’s romantic version of the sea bathing of the 1700s and 1800s. During the 1900s, hiking became one of the main activities through which ‘urbanites sought to escape from the alienation of modern life and experience the sublime’ (Drennig, Citation2013, p. 557). In the empirical material as well, hiking is an important activity that tourists undertake in order to get away from civilization and connect with the non-human world.

To conclude, the ways of seeing identified through representations in tourists’ Instagram posts construct a romantic tourist gaze that approaches the national parks as isolated enclaves and commodified havens that offer tourists an escape from humanity, grand views, and seclusion within the non-human world. The main implication of this tourist gaze in relation to the Swedish national parks is that it sustains and (re)produces the distancing relation between the human and the non-human, which makes the two appear to be opposite poles instead of integrated equals. In the Swedish national parks’ future developments into nature-tourism destinations, the implications for how the tourism industry (including tourists) make sense of the parks’ non-human world need to be brought to light. Importantly, this is because such tourist practices have an impact on how we conceptualize environmental questions and how they should be handled (Cronin, Citation2011), but also because they affect and limit the ways in which humans can understand and act upon such questions (Rutherford, Citation2011). Only when this is emphasized can we problematize our understandings and reframe our distancing approach to the non-human world (Bird Rose, Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2019).

This article can be seen as one step towards such a direction, but this research cannot stand by itself. Swedish national parks (together with national parks all over the world), with their potential to attract major numbers of tourists, and their focus on nature conservation, clearly have the potential to raise such questions. Thus, they can unsettle the current imbalances between the human and the non-human and be frontiers for a more reflexive, balanced, and non-human-friendly world (see Bird Rose, Citation2015; Gordon-Walker, Citation2019). Furthermore, this article has underlined the importance of studying ‘new’ forms of expressions that have not been covered concerning a research topic before. It has illustrated that when being interesting in ways of seeing the non-human in national parks constructed by tourists, there is value in studying Instagram posts produced by tourists. Such enables researchers to get into tourists’ ontological and epistemological stances, contributing to understanding how we as humans look upon the world we call ‘nature’. It has also provided an analytical example of how an analysis with inspiration from both visual culture and Foucauldian discourse analysis could deal with these questions. A suggestion for future research would be to not only analyze materials produced by tourists but also to have conversations with them regarding their ways of seeing, or invite them into the analytical process and conduct an analysis of their materials together. That could deepen the understanding of their ways of seeing the non-human world and nuance of already existing research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emelie Fälton