ABSTRACT

This study explores the effectiveness of social holidays by examining, how the objectives of state-driven Finnish social tourism are met in practice and how the benefits of a social holiday differ between disadvantaged families with children and adult groups. Among both groups, the results of a quantitative survey (N = 796) and six qualitative interviews of four highly experienced holiday instructors foreground benefits related to emotional and mental well-being, participation and activeness, and an opportunity to escape mundane responsibilities and difficult life situations. Our results suggest that in some areas (social interaction, life management, peer support) outcomes of a holiday vary between customer groups, which foregrounds the need to match social tourism objectives and services to their variable needs and motives. Regarding methodological aspects, this study demonstrates that when a respondent directly evaluates the benefits of a holiday, the results may differ from those gained via two-stage quantitative analyses applying general-level scales.

Introduction

Social tourism commonly refers to supporting disadvantaged people to participate in tourism, with the aim of promoting well-being, equality and inclusion in society (Minnaert et al., Citation2009). The concept covers a wide range of activities for different target groups, which is challenging from a research perspective (McCabe & Qiao, Citation2020). Social tourism programmes and stakeholder networks differ between countries and even in one country there can be several forms of social tourism implementation (Minnaert, Citation2020; Minnaert et al., Citation2011). Often, the different approaches are not directly comparable with one another (Komppula et al., Citation2016). Depending on the type of system, social tourism can be charity-based or a publicly funded governmental policy. Examples of social tourism products are a voucher with several utilization options, a domestic holiday on which customers go independently, a group holiday designed for a special target group and a day trip to a local tourist attraction (Komppula et al., Citation2016; Minnaert et al., Citation2011; Pyke et al., Citation2019).

While much previous social tourism research has focused on the demand side outcomes for the tourist (see McCabe & Qiao, Citation2020), few have attempted to assess the extent that those outcomes meet the objectives of the funding programme. Publicly funded social tourism can be justified if the activity leads to desired benefits, such as well-being and inclusionary outcomes (Minnaert et al., Citation2006). Hence, social tourism has been understood as an investment which contributes to societal level value, for instance, in a form of savings in public costs and building a ‘fair society’ (McCabe & Diekmann, Citation2015; Minnaert et al., Citation2006).

Secondly, although the benefits of social tourism have been studied at the general level both internationally (Minnaert et al., Citation2006) and in the Finnish context (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020), the fulfilment of the objectives of social tourism programmes has not been consistently investigated (Minnaert et al., Citation2006). Hence, there is a lack of evidence on how publicly managed social tourism programmes meet specified objectives, which may eventually decrease the public acceptance of social tourism and lessen resources allocated to the activity. This issue is accentuated, when there are increasing pressures on national budgets (Lima & Eusébio, Citation2020), for instance, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the results of previous studies (Komppula & Vento, Citation2021; Vento & Komppula, Citation2020), Finnish social tourism stakeholders see the social tourism system as well-developed and effective, but the representatives of the public funding organization have expressed concerns regarding the evaluation mechanisms used to assess its effectiveness. Hence, the managerial aim of this study is to propose a scientifically validated scale for Finnish social tourism operators to measure the effectiveness of social tourism policies and programmes in the future.

To contribute to the above-mentioned research gaps, the purpose of this study is to enhance understanding of the effectiveness of social holidays, and the objective to examine, how the pre-defined objectives of Finnish social tourism programmes are met in practice and how the effects of a social holiday vary between families with children and other holiday-takers. Since the studied phenomenon is weakly known, exploratory approach is adopted instead of deductively defining and testing specific research hypotheses (see Stebbins, Citation2001). Particular attention is paid on a disadvantaged family with children, which is a crucial social tourism target group internationally (McCabe, Citation2009) and in Finland (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). It has also been identified as an emerging target group of family tourism research, since increasing well-being and inclusion of disadvantaged families through holiday-taking contributes positively to the development of children and society (Schänzel & Yeoman, Citation2014). According to the Finnish institute for health and welfare (Citation2020), the best way to prevent societal inequality is by supporting disadvantaged families. Social tourism can be seen as one form of this support, which emphasizes the need to examine the outcomes of the activity among families with children (see Schänzel & Yeoman, Citation2014; Vento et al., Citation2020).

This mixed-methods study is conducted in two stages. First, a quantitative survey of people who had recently been on a social holiday was conducted. Second, in the qualitative study, four highly experienced holiday instructors working on Finnish social holidays were interviewed. Two of them were interviewed both pre-COVID and post-COVID, whereas the other two were interviewed solely post-COVID in November 2021, when the Finnish pandemic restrictions (e.g. on group hobbies, restaurants, public premises) had been suspended before the outbreak of the omicron variant. Although people working in the customer interface often have unique insight of customers’ needs and other customer-related phenomena (Homburg et al., Citation2009), holiday instructors have commonly been neglected in the previous social tourism research.

The article proceeds as follows. After the introduction, the next section encompasses the literature review, focusing on the objectives and implementation of social tourism in Finland and the benefits of social tourism followed by the methodology section that presents the data collection, analysis and, findings of both quantitative and qualitative parts of the study, the discussion, and conclusions sections, respectively.

Literature review

Objectives and implementation of social tourism in Finland

Although social tourism invariably involves moral value, it can be categorized by the justifications and goals of the activity (Minnaert et al., Citation2006, Citation2011). The main goal of host-related social tourism is benefitting the host community, for instance, by stimulating tourism in rural areas or combating seasonality in tourism destinations (McCabe & Diekmann, Citation2015; Minnaert et al., Citation2011). Visitor-related social tourism aims at benefitting the disadvantaged customer (Minnaert et al., Citation2011), the main target groups being those who cannot participate in tourism due to physical disabilities, low income and/or social exclusion (McCabe & Diekmann, Citation2015; Minnaert et al., Citation2006). Ideologies behind visitor-related social tourism are ‘tourism for all’ and ‘supporting the weaker’ (Minnaert et al., Citation2006, Citation2011). Whereas host-related social tourism is often used as a governmental tool, visitor-related social tourism can be publicly funded, or charity-based (Minnaert et al., Citation2006).

In Finland, visitor-related social tourism is a well-established public socio-political instrument. It represents the ideology of ‘supporting the weaker’, meaning that the most disadvantaged populations are involved in tourism (see Minnaert et al., Citation2006; Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). The Finnish social holiday commonly comprises a five-day break in a domestic tourism destination. It includes full board and organized activities with voluntary participation. The holiday programmes are based on the special needs of different target groups (e.g. families with children, pensioners, people with illnesses and disabilities, caregivers, unemployed individuals).

Finnish social holidays are organized by five holiday associations. Normally, they receive approximately 45,000–50,000 holiday applications in a year, of which approximately 30% are accepted (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). The state-owned gaming monopoly Veikkaus Oy grants the social tourism funding, which is distributed and controlled by the Funding Centre for Social Welfare and Health Organizations (STEA, Citation2021) that is governed by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. To clarify the impact expected from Finnish social tourism, the funding organization STEA has set objectives for the activity: supporting life management, strengthening social networks, promoting opportunities for participation, developing life patterns conducive to health and emotional well-being, creating a sense of community, strengthening intra-family relationships and preventing problems (Hyvinvointilomat ry, Citation2018).

Benefits of social tourism

In general terms, previous studies analysing the benefits of social tourism from the customers’ perspective can be divided into (1) quantitative 2-stage analyses concentrating on well-being outcomes (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Pyke et al., Citation2019; Vento et al., Citation2020) and (2) mostly qualitative studies examining the benefits of a holiday among a certain target group, such as a disadvantaged family with children (e.g. McCabe, Citation2009; Minnaert, Citation2012; Minnaert et al., Citation2009; Smith & Hughes, Citation1999) or individuals and families suffering from health issues (e.g. Chung & Simpson, Citation2020; Hunter-Jones et al., Citation2020; Komppula et al., Citation2016) or unemployment (e.g. Kakoudakis et al., Citation2017; Komppula & Ilves, Citation2018). Although the results of previous research can support countries’ social policy (Minnaert et al., Citation2009), the main focus has not been on examining the fulfilment of pre-defined social tourism objectives in a specific context.

The previous research has demonstrated that some social tourism target groups, such as seniors, unemployed and disabled individuals may suffer from social exclusion in their daily life, and in these situations, a social holiday can contribute to extending the limited social worlds (Eichhorn, Citation2020; Kakoudakis, Citation2020; Morgan et al., Citation2015). Especially in a group holiday situation, activeness and participation, social interaction, long-term friendships and peer support may be enhanced (Bos et al., Citation2015; Komppula et al., Citation2016; Komppula & Ilves, Citation2018). For seniors or people with health problems, improving physical conditions can be the main purpose and benefit of a social holiday (Komppula et al., Citation2016).

A break from daily life and mundane responsibilities may contribute to emotional and mental well-being of social holiday participants, providing an opportunity to relax and recharge batteries (McCabe, Citation2009; McCabe et al., Citation2010; Smith & Hughes, Citation1999). A social holiday can make recipients feel ‘normal’, when even in highly exceptional and difficult life situations they are enabled to have a temporal escape and become involved in something considered as ‘regular life’ (Chung & Simpson, Citation2020; Hunter-Jones et al., Citation2020). A holiday experience and the change of a scenery can also help beneficiaries put their life situation into context and develop hope for the future (McCabe, Citation2009).

For families, a social holiday is an opportunity to nurture intra-family relationships (McCabe et al., Citation2010) which may improve communication between family members (Kakoudakis et al., Citation2017) and lead to more frequent ‘family outings’ after returning home (Minnaert et al., Citation2009; Vento et al., Citation2020). Parents of disadvantaged families often want to offer their children good memories and experiences that are commonly available to the majority of other children (McCabe, Citation2009; McCabe et al., Citation2010). Parents are typically aware that their children do not have the same possibilities as their peers to participate in leisure activities (McCabe, Citation2009), which might be related to the social holiday’s recognized potential for promoting the feelings of equality among disadvantaged families (Vento et al., Citation2020).

Despite the various benefits of social tourism, research has noticed that not all participants benefit from social holidays in an optimal way (Minnaert et al., Citation2009). Being on a holiday can be stressful for parents if they have, for instance, a large family or children with special needs (Minnaert et al., Citation2009). Sometimes a lack of experience on holiday-taking can be an issue, particularly if customers go on a holiday without the support of group or personnel in a destination (Minnaert et al., Citation2009). In the Finnish context, holiday groups can be heterogeneous, whereby customers may have different needs and motives regarding a holiday experience (Komppula et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the Finnish social tourism objectives commonly include participation in organized holiday activities, such as guided exercise, crafting, lectures and peer support discussions (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). According to the results of previous studies (Komppula & Vento, Citation2021; Vento & Komppula, Citation2020), the participation rates may vary between, for example, pensioners and families, which may jeopardize the fulfilment of the objectives among the customers not participating in the activities.

Methodology

This study took a mixed-methods approach and therefore reflects the pragmatic research paradigm. With respect to this, the aim was to deepen the understanding gained by quantitative analysis with qualitative data and methods, to obtain a more comprehensive insight of the research problem, as well as ‘socially useful knowledge’ (Feilzer, Citation2010, p. 6).

Customer perspective: quantitative study

The questionnaire scale of the quantitative study was based on the objectives of Finnish social tourism; hence the responses represent informants’ evaluation of the effectiveness of a social holiday one month after returning home. The scale and the study were conducted in cooperation with Hyvinvointilomat ry, the biggest holiday association organizing social holidays in Finland. Annually, the association receives approximately 10,000 holiday applications, of which around 30% are accepted. The data were collected in three stages: after autumn and Christmas holidays 2018, after winter holidays 2019 and after summer holidays 2019. One month after a holiday, the holiday association sent the questionnaire either by e-mail or postal mail to the respondents. Regarding ethical aspects and anonymity, no personal information of the participants was transferred to the researchers. The amounts of questionnaires distributed and returned, as well as the response rates, are presented in .

Table 1. Questionnaire rate of return.

Measures

In the questionnaire, a 7-point Likert scale was applied. The scale items and their relationships with the Finnish social tourism objectives are illustrated in Table 3. To some extent these relationships are interpretative and the objective ‘preventing problems’ is related to all items of the scale.

To be able to investigate the effectiveness of a social holiday on family well-being, the questionnaire was different between those who had been on a family holiday with their children (‘family holiday-takers’) and those who had been on a holiday individually, with a partner or, for instance, with a friend or a relative (‘individual holiday-takers’). The individual holiday-takers include, for instance, pensioners, caregivers, illness-based groups and the unemployed. Whereas the individual holiday-takers filled the questionnaire from their own perspective, the family holiday-takers answered the questions from the perspective of a family. The family holiday-takers’ questionnaire also involved two extra items related to family relationships. The differences between the items are visible in Table 3.

Data

The quantitative data consist of two groups: individual holiday-takers (N = 510) and family holiday-takers (N = 332). Data cleaning were conducted based on subject’s response behaviour: if all responses to the questionnaire scale were identical, the respondent was removed from the data. Eventually, 40 responses were removed from the individual holiday-takers (after data cleaning N = 470) and six subjects from the family holiday-takers (after data cleaning N = 326).

The distribution of samples presented in demonstrates that among both individual holiday-takers and family holiday-takers most of the respondents are female (75.7% and 86.5%, respectively). Regarding family circumstances, the individual holiday-takers are mainly living alone (51.3%) or in a relationship with no children living at home (43.8%), whereas the family holiday-takers are mainly single parents (34.7%) or in a relationship with children living at home (51.5%). The individual holiday-takers and the family holiday-takers represent different age groups: while the former mostly fall into the category of 57–95 years old the age having a mean of 69.13, the latter are mostly 19–56 years old the age having a mean of 40.72.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of background variables: individual holiday-takers (IHD) and family holiday-takers (FHD).

Data analysis

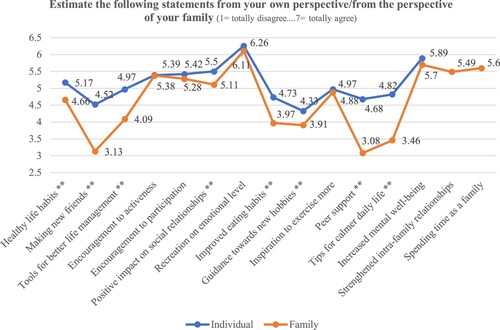

The data analysis was based on the descriptive statistics of the questionnaire scale and comparing the scores of the individual holiday-takers (IHD) and the family holiday-takers (FHD). The descriptive statistics of the questionnaire items are presented in . The differences in means, as well as the applied response scale, are visible in .

Figure 1. Line graph: Individual holiday-takers’ and family holiday-takers’ mean responses and statistically significant differences between the groups (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the scale items and relationships between the items and social tourism objectives (family holiday-takers’ questionnaire items in italics).

To recognize statistically significant differences between the scores of IHD and FHD, the originally separate scores of the two groups were computed as new variables. These were analysed by Mann–Whitney U test (significance level p < 0.05). The chosen test is applicable, since the dependent variable is ordinal and not normally distributed and homogeneity of variances was not met with most of the variables (Neideen & Brasel, Citation2007).

Results

Some of the results indicate more signs of an effectiveness than others, and some aspects demonstrate a clear heterogeneity in the individual holiday-takers’ and family holiday-takers’ social holiday experience. We first present the aspects in which the target groups have responded somewhat similarly, and then turn to those characterized by heterogeneity.

The results demonstrate that both individual holiday-takers and family holiday-takers estimate that a holiday has led to emotional recreation (IHD: M = 6.26, SD = 1.11; FHD: M = 6.11, SD = 1.28) and increased mental well-being (IHD: M = 5.89, SD = 1.34; FHD: M = 5.7, SD = 1.53) without statistically significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05). These two items had the highest means of the scale, as well as modes of 7, among both groups.

Both individual holiday-takers and family holiday-takers estimate that a social holiday has encouraged them to become more active (IHD: M = 5.39, SD = 1.43; FHD: M = 5.38, SD = 1.55) and greater participation (IHD: M = 5.42, SD = 1.44; FHD: M = 5.28, SD = 1.64), since the responses of these items were typically on the alternatives greater than 5 and there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05). Additionally, the evaluations concerning the inspiration to exercise more are similar (p > 0.05) between the two groups (IHD: M = 4.97, SD = 1.59; FHD: M = 4.88, SD = 1.67), the means being close to 5.

Regarding the item ‘holiday had a positive impact on social relationships’, the results indicate stronger effectiveness among the individual holiday-takers than the family holiday-takers (IHD: M = 5.5, SD = 1.4; FHD: M = 5.11, SD = 1.61) with a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between the groups. Additionally, the individual holiday-takers estimate that a holiday has guided them towards healthy life habits, since the responses were typically on the alternatives larger than 5 (M = 5.17, SD = 1.4), whereas the responses of the family holiday-takers were commonly on the alternatives smaller than 5 (M = 4.66, SD = 1.64), the difference between the groups being statistically significant (p < 0.01). This trend applies also to the items measuring the guidance towards new hobbies (IHD: M = 4.33, SD = 1.6; FHD: M = 3.91, SD = 1.85) and the improvement of eating habits (IHD: M = 4.73, SD = 1.55.; FHD: M = 3.97, SD = 1.76), as both items have significantly (p < 0.01) higher scores among the individual holiday-takers (responses typically on the alternatives larger than 4) than the family holiday-takers (responses typically on the alternatives smaller than 4).

A clear and a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between the scores of the individual holiday-takers and the family holiday-takers are related to the items that measure, if a holiday has provided tools for better life management (IHD: M = 4.97, SD = 1.45; FHD: M = 4.09, SD = 1.74) or offered tips for calmer daily life (IHD: M = 4.82, SD = 1.59.; FHD: M = 3.46, SD = 1.78). The individual holiday-takers evaluate both items more positively than the family holiday-takers, the difference in means being 0.89 and 1.36, respectively.

Another clear and a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between the scores of the two groups is related to the items that measure, if the respondents have had new friends during a holiday (IHD: M = 4.52, SD = 1.92; FHD: M = 3.13, SD = 2.01) or got (peer) support from others in a similar life situation during a holiday (IHD: M = 4.68, SD = 1.72; FHD: M = 3.08, SD = 1.96). The individual holiday-takers evaluate both items more positively than the family holiday-takers, the difference in means being 1.4 and 1.6, respectively.

Finally, the results of the two extra items demonstrate that among the family holiday-takers, the holiday strengthened intra family relationships (M = 5.49, SD = 1.45) and encouraged families to spend time together (M = 5.6, SD = 1.41). The responses were typically targeted at alternatives larger than 5, both items having modes of 7.

Stakeholders’ perspective: qualitative study

Regarding the qualitative study, four holiday instructors were interviewed who work in the four biggest holiday resorts where the holiday association Hyvinvointilomat ry organizes social holidays. The informants were chosen based on their unique expertise and customer insight, which has been formed during 20–30 years of experience of working with different social tourism customer groups on Finnish social holidays. The two pre-COVID interviews were conducted face-to-face during subsidized family holidays: the first one took place in a spa resort during a winter holiday (H1.1, February 2019) and the second one in a holiday village during a summer holiday (H2.1, July 2019). The four post-COVID interviews were conducted via telephone or Microsoft Teams in November 2021. The first two post-COVID interviewees were also interviewed pre-COVID, due to which interviews H1.1 & H1.2 and H2.1 & H2.2 have been combined (H1 & H2). The informants had continuously been working at the same resorts. The last two post-COVID interviewees, who were not interviewed pre-COVID, were working at a spa resort (H3) and a sports centre (H4). All four resorts also have self-paying customers, although their numbers are significantly higher in the spa resorts and the sports centre than in the holiday village.

The themes of the interviews included the characteristics and heterogeneity of social tourism customer groups, the benefits and challenges of Finnish social tourism and social holidays, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (post-COVID interviews). The length of the interviews varied from 13 to 41 min, the mean of length being 27 min. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the data were analysed by theme-based content analysis (see Eriksson & Kovalainen, Citation2016).

Findings

The results of our quantitative analysis underline positive emotional and mental outcomes of a social holiday among both families and adult groups. All interviewees think that a crucial benefit of a Finnish social holiday is getting a break from mundane life and household chores. According to them, a social holiday offers an opportunity to experience something different compared to daily life and a temporal escape from problems that exist in home environment. According to H2,

There can be, for example, one sick person in a family and it drains energy from the whole family unit. It can be a child, or it can be an adult … and then the whole family is somehow stuck with the issue.

Although working in a sports centre, in which physical activities have a central role, H4 foregrounds the mental benefits of a social holiday over the physical ones. H4 ponders that when customers get physically active, they empower physically, ‘but I think the mental aspect is after all the biggest benefit’. Although our quantitative results demonstrate that a social holiday inspires both families with children and adult groups to exercise, the interviewees state that COVID-19 pandemic has weakened particularly seniors’ physical condition, when public swimming pools and group exercises have been closed. H3 describes that the seniors have been surprised, when during guided exercises they have noticed how their physical condition has ‘taken steps back’.

Our quantitative scores demonstrate that the effect of a holiday on social relationships and interaction is stronger among the adult groups than families with children. During the pre-COVID interview, H1 explains that particularly pensioners can be very lonely in their daily life, due to which ‘getting into a place like this, where you meet a lot of different people, is very important for them’. All interviewees emphasize that especially the elderly have been socially isolated during COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased loneliness and social exclusion. H2 has noticed that if a holiday group consists of similar types of customers, customers create social networks more eagerly than when a group is heterogeneous: ‘Often, for example, large families tend to approach one another … like they have similar things going on in their life.’ H3 states that particularly in illness-based groups, age distribution can be wide, which is challenging in terms of social networking. H1 explains that sometimes a strong personality in a holiday group becomes an unofficial group leader and motivates others to join activities and operate as a group. On the other hand, sometimes the unofficial group leader may have a negative effect, ‘if the person wants to concentrate only on negative matters. And the whole group joins this’. Although the interviewees state that social interaction should be voluntary for a customer, H4 thinks that sometimes being socially isolated during a holiday can be related to personal issues of a customer.

Regarding activeness and participation, the holiday instructors confirm the earlier findings concerning the higher participation rates of pensioners than families with children (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020), which are in contradiction with our quantitative results. On the one hand, H1 highlights that differences in participation rates can be related to the specific needs of a customer group: at the beginning of a holiday, caregivers may not participate in activities due to their need for rest. On the other hand, all interviewees emphasize heterogeneity within the customer groups: ‘Families with children, for instance, can be extremely different from one another. Some groups are really active, they participate almost everything, but some other week … you don’t see anyone anywhere’ (H1). According to H3, getting more information than a list of names of a holiday group before a holiday, would help matching the contents of the activities to the needs of the group.

All interviewees underline that on a holiday, voluntary participation is important. Anyway, H1 and H3 ponder that one activity in the middle of the week could be obligatory, so that those customers, who would need extra support on a holiday, could be reached. H3 has noticed a certain division between the customers when some of them are very active and enjoy holiday activities on their own, ‘But unfortunately, the other half … children wander here without supervision, while adults are on social media or whatsoever. And at the end of the week, it starts to cause certain problems.’ With respect to this, H2 thinks that when some matters are in question, such as family dynamics and interaction, positive development can be extremely challenging to achieve during a 5-day social holiday.

According to our quantitative results, peer support actualizes more commonly among the adult groups than families with children. The interviewees state that peer support is often important for illness-based groups, ‘when they get practical tips from others, like how to apply different benefits, and they get mental support and so on’ (H1). However, H1 explains that sometimes peer support can be problematic on illness-based holidays. For some customers, peer support activities would be crucially important, whereas others may not be willing to think about their health issues on a holiday: ‘and then those, who would need peer support, may have no one to talk with’ (H1).

In terms of life management-related aspects, which indicate a clear difference between the individual holiday-takers’ and the family-holiday takers’ quantitative scores, H3 states that nowadays, many families seem to be struggling with scheduling their days while being on a holiday. H3 thinks that if parents would be able to motivate their children to participate in kids’ activities and childcare hours, they would have opportunities to relax during the week, and being on a holiday would be easier for everyone. H3 mentions that sometimes those families, who struggle with holiday-taking, leave before five days have passed: ‘They just can’t be on a holiday for five days as a family. Whereas those families, who do participate, never leave before the end of a holiday.’ H3 also thinks that many families struggle with eating, because they have gotten used to convenience food: ‘They think that the dessert table is the only child-friendly thing here. Otherwise, the parents say that we should have chips and nuggets on every meal, or their kid won’t eat anything.’

Despite the issues described above, our quantitative results indicate that the benefits of social tourism on family well-being actualize among families with children. According to our interviewees, families commonly enjoy quality time together, as well as having ‘other things to do than just using a cell phone or being on a computer’ (H2). According to H2, during COVID-19 pandemic, the role of customer-driven family time has accentuated in a positive way: ‘It has been wonderful how they have been doing things as a family. They have spent time in the nature, and I think that … they are much more receptive to new things than before corona.’ H4 thinks that whereas for parents, emotional recreation and a break from mundane responsibilities are essential benefits of a holiday, for children ‘The activities, different sports, swimming pools and saunas, adventure parks … all this is The Thing.’ H4 also foregrounds the aspect of equality, when disadvantaged children can share their holiday experiences with their friends.

Finally, all interviewees emphasize the meaningfulness and importance of social tourism and hope that the activity would exist in the future. They think that COVID-19 pandemic has increased the need for social holidays. H2 describes that after the pandemic restrictions, customers have clearly been more satisfied and less critical with their holiday than before the pandemic. All interviewees characterize decreasing Veikkaus-funding and tightening budgets as a worrisome development. H3 ponders that it is difficult to rate the publicly funded activities and estimate, which one is more important than the other, particularly, ‘when the effectiveness of this kind of activity is difficult to measure and justify. I see it, but how to show it to the funding organization?’. H1 states that someone should actively promote the importance of social tourism, since ‘if the general atmosphere is that this is not important, it is worrying’.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to increase understanding of the effectiveness of social holidays in the Finnish context by investigating with mixed methods, how the objectives of Finnish social tourism are met in practice. Fulfilment of each objective was measured with statements designed in collaboration with the holiday association. Additionally, six interviews with four experienced holiday instructors were conducted to get in-depth understanding of the way that the benefits of Finnish social tourism currently actualize among different customer groups.

The social tourism objective ‘developing life patterns conductive to health and emotional well-being’ can be related to several aspects. To some extent our results, which accentuate the emotional benefits of a holiday, are in contradiction with those of McCabe and Johnson (Citation2013) who did not find an effect on customer’s emotional well-being, and Pyke et al. (Citation2019) who did not find an effect on customer’s psychological well-being as a result of a social holiday. However, our measures are not fully comparable with the general-level scales applied in the previous quantitative studies (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Pyke et al., Citation2019; Vento et al., Citation2020). Instead, they represent customers’ subjective and direct evaluations of a social holiday experience.

Our findings indicate that getting a break from the responsibilities and worries of mundane life is an essential benefit of a social holiday, which was identified as an important contributor of emotional and mental well-being in the previous social tourism literature (Hunter-Jones et al., Citation2020; McCabe, Citation2009; Smith & Hughes, Citation1999). The findings demonstrate, how, for instance, health issues can be dominant and exhausting in home environment, but temporarily forgotten when being on a holiday away from home, which supports the results of Hunter-Jones et al. (Citation2020). With respect to the results of McCabe (Citation2009), our findings emphasize social holidays’ potential of acting as an intervention that can widen perspectives and provoke hope in situations, which have previously felt like hopeless.

Our results indicate that a social holiday increases physical activity among families and adult groups, whereas previous studies have brought forth benefits related to this area from the viewpoint of the elderly (e.g. Ferrer et al., Citation2016). However, according to our post-COVID interview findings, the seniors’ current need for improving physical condition is accentuated. In terms of healthy eating habits, our findings demonstrate, how disadvantaged families can have problems with healthy eating. The relationship between low income and less healthy food choices has been recognized in previous studies (e.g. Hardcastle & Blake, Citation2016), and our results suggest that the issue may exist also in the Finnish society.

Regarding the social tourism objective ‘supporting life management’, the recognized differences between families and adult groups might be related to differences in participation rates in educational activities. These differences may be explained by practical reasons, since participating lectures and peer support discussions with small children can be impossible. Additionally, motivational factors may play a role. Our findings demonstrate that educational activities are particularly important for customers, who learn how to cope better with their medical condition. According to the results of Komppula et al. (Citation2016), a medical condition can increase the personal relevance of an activity and promote participation, but especially issues with mental capacity may decrease the level of involvement. To some extent families’ life management issues might be visible in our findings that illustrate, how some families struggle with holiday-taking. However, these issues could also be related to a lack of experience of being on a family holiday (Minnaert et al., Citation2009).

Regarding the social tourism objective ‘promoting opportunities for participation’, our results demonstrate that a social holiday encourages both families and adult groups to participation and activeness, which aligns with the results of previous social tourism studies conducted in the context of a group holiday (Bos et al., Citation2015; Komppula et al., Citation2016). The forms of participation and activeness have not been specified in the Finnish social tourism objectives nor questionnaire items, and our findings demonstrate that some customers prefer increasing the level of participation and activeness, for instance, in the context of a family unit, instead of utilizing a holiday programme and the support of a group. Our findings suggest that activities and ‘doing’ are particularly important for children, which supports the results of Minnaert (Citation2012). Simultaneously, our results indicate that in the context of a social holiday, families do not get involved in new hobbies as commonly as the adult groups, which might be in contradiction with the needs of children. Although our results accentuate the importance of voluntary participation, they also suggest that some customers, who may struggle with holiday-taking, could benefit from an obligatory ‘check-point’ during their holiday.

Concerning the objectives ‘strengthening social networks’ and ‘creating a sense of community’, to some extent our results support the view that family holiday customers prefer spending time as a family instead of networking with a holiday group (Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). In our quantitative study, the individual holiday-takers include those customer groups (pensioners, unemployed, illness-based groups), who may suffer from loneliness in their daily life and look forward to social interaction in the context of a social holiday (Eichhorn, Citation2020; Kakoudakis, Citation2020; Morgan et al., Citation2015). Regardless, our results indicate that social relationships have to some extent been improved in both studied groups, which aligns with the findings of previous studies emphasizing relational benefits of a social holiday (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Minnaert et al., Citation2009; Pyke et al., Citation2019; Vento et al., Citation2020). For some, relational benefits may actualize outside a holiday group, and some respondents may consider improved family relationships as a part of their social life.

Our results illustrate that a strong personality in a holiday group can have either a positive or a negative effect on group formation, which is a new discovery in social tourism research. Simultaneously, the findings demonstrate that customers in a similar life situation tend to create social networks more commonly than groups that are heterogenous, which aligns with the results of Komppula et al. (Citation2016). Hypothetically, the members of an illness-based group, who share a common medical condition, identify with one another more strongly than, for example, customers of a subsidized family holiday in a situation, where the holiday group is heterogeneous (e.g. single parents, large families, young parents, families with special needs). However, our findings indicate that sometimes a wide age distribution can be an issue particularly in illness-based groups. Additionally, for some, thinking about health issues on a holiday can be unpleasant, which can jeopardize peer support and is explained by motivational factors rather than health capacity issues (see Komppula et al., Citation2016).

Regarding the social tourism objective ‘strengthening intra-family relationships’, our results demonstrating the benefits of a social holiday on family well-being correspond with the results of previous studies conducted among families with children (McCabe, Citation2009; McCabe et al., Citation2010; Minnaert, Citation2012). Besides a break from the responsibilities of daily life (McCabe, Citation2009; Smith & Hughes, Citation1999), our results also highlight a break from using digital devices as a benefit of a family holiday. This may signal that engagement with digital devices can nowadays have a negative effect on family well-being among disadvantaged families. Additionally, our results indicate that some elements of family well-being, such as family dynamics and the way that a family spends time together, are developed in a home environment, and a social holiday may not have strong potential to affect these aspects. In the study of Vento et al. (Citation2020), the effect of a social holiday on family cohesion, and family conflict (see Fok et al., Citation2014) remained unclear, with no convincing evidence of positive impact. According to the results of previous studies, issues with family well-being can be one reason for not applying for a social holiday (Vento et al., Citation2020) or not participating holiday activities (Komppula et al., Citation2016; Komppula & Ilves, Citation2018). Interestingly, our interview findings illustrate that COVID-19 pandemic has brought some families closer together and encouraged them to spend time in nature, which can have positive effects on health and well-being (Keniger et al., Citation2013). The meaning of equality is pointed out from the perspective of children, which corresponds with the results of previous studies (McCabe, Citation2009; McCabe et al., Citation2010).

Finally, the findings of the holiday instructors’ interviews demonstrate that COVID-19 pandemic has enhanced the need for social tourism and brought forth the importance of the activity from the perspective of different target groups. Simultaneously, the pandemic is one reason for decreasing Veikkaus-funding and tightening budgets (Veikkaus Oy, Citation2021). In Finland, the complexity of measuring the effectiveness of social tourism and justifying the existence of the activity in relation to other Veikkaus-funded activities (Komppula & Vento, Citation2021; Vento & Komppula, Citation2020), are urgent challenges, which are pointed out in our post-COVID interview findings.

Conclusions

Theoretical implications

As a theoretical implication, the results of this study deepen the knowledge of the effectiveness of social tourism initiatives, which has been called for in the previous literature (e.g. Minnaert et al., Citation2006). The results indicate that increased emotional and mental well-being, as well as activeness and participation, are important benefits of a social holiday. According to our results, these benefits actualize somewhat similarly regardless of dissimilar demographic characteristics, heterogeneous life situations and different holiday behaviour of the customer groups. Additionally, relational and life-management-related benefits are emphasized among the individual holiday-takers, and family-related benefits among the family holiday-takers. Our results foreground the meaning of escapism, both in relation to mundane life and challenging life situations. In previous qualitative social tourism studies (e.g. Hunter-Jones et al., Citation2020; McCabe, Citation2009), escapism has been brought forth as a significant source of emotional and mental recreation.

This study contributes to the methods of social tourism research by noting that when a respondent is directly asked to evaluate the effects of a social holiday, the order of importance of different aspects might turn out to be different than in the analyses applying general-level scales. An example of this is aspects related to emotional and mental well-being, which, according to our results, are crucial benefits of a social holiday and have been strongly accentuated in previous qualitative social tourism research (e.g. McCabe, Citation2009; Smith & Hughes, Citation1999). However, in 2-stage quantitative investigations (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Pyke et al., Citation2019; Vento et al., Citation2020), a straightforward positive effect has not been captured.

Practical implications

As a practical implication for both Finnish and international social tourism operators, our results suggest that splitting the most diverse customer groups, such as a family with children, into smaller sub-components and ‘matching’ the social tourism objectives and holiday programmes to their needs (see McCabe & Qiao, Citation2020), could enhance value creation in the context of a social holiday. Simultaneously, increasing the homogeneity of holiday groups would promote network-building and peer support among customers. In this development process, the expertise of customer-interface workers could be utilized. Our results illustrate that, for instance, holiday instructors have concrete ideas to improve the effectiveness of social holidays (e.g. reaching the customers who need support on a holiday, pre-planning the content of a holiday based on the characteristics of a holiday group).

Finally, there is an urgent need to justify the existence of social tourism since the competition of funding resources is intensifying (Lima & Eusébio, Citation2020; Vento & Komppula, Citation2020). Social tourism has been promoted as an equitable and sustainable way to stimulate tourism consumption after COVID-19 pandemic (McCabe & Qiao, Citation2020) and our results demonstrate that the pandemic has increased the demand for social holidays, which underscores the need for further scientific research. Social tourism operators may not be able to report the effectiveness of their actions independently, which foregrounds the role of a scientific community, as well as the managerial value of this kind of cooperation.

Limitations and future studies

Since many of the Finnish social tourism objectives are broad and even ambiguous by nature, in many cases the relationships between the quantitative questionnaire items and social tourism objectives are not straightforward. Depending on an interpretation, a single item can, for instance, be related to several of the objectives. Additionally, the social tourism objectives are related to one another, since, for example, improved social networks may lead to better emotional well-being and strengthen the sense of community. Due to the ambiguousness related to the research setting, conducting the qualitative study was necessary to support the interpretations of the results of quantitative analyses, as well as to increase understanding of the studied phenomena in the current situation. The qualitative study also provides a unique approach to the service provider’s perspective, while the quantitative study represents the customer’s viewpoint. Nevertheless, the potential long-term transformative effect of a social holiday is not investigated, which is an indisputable limitation of this study.

We suggest that further investigating the needs and motives of social tourism customer groups, as well as involving customer-interface workers in social tourism research, would support adapting the social tourism programmes and services based on the findings. A second post-holiday survey and/or qualitative data collection investigating potential long-term effects of a social holiday would increase the insight of the transformational value of social tourism. Additionally, similar studies in other contexts would enhance understanding of the effectiveness of different social tourism systems, which would enable international comparisons and support recognizing the best practices of social tourism (Diekmann & McCabe, Citation2011).

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank professors Raija Komppula, University of Eastern Finland, and Scott McCabe, Nottingham University Business School, for their support and advice throughout this study, as well as university lecturer Timo Tammi, University of Eastern Finland, for his guidance with quantitative research methods. The author is also grateful for the fruitful cooperation with the holiday association Hyvinvointilomat ry and the funding provided by Kuluttajaosuustoiminnan säätiö, without which conducting this research project would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elli Vento

Elli Vento is an Early-Stage Researcher at the University of Eastern Finland Business School. Currently, she is exploring the effects of social tourism in the Finnish context.

References

- Bos, L., McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2015). Learning never goes on holiday: An exploration of social tourism as a context for experiential learning. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(9), 859–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.790878

- Chung, J. Y., & Simpson, S. (2020). Social tourism for families with a terminally ill parent. Annals of Tourism Research, 84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102813

- Diekmann, A., & McCabe, S. (2011). Systems of social tourism in the European Union: A critical review. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(5), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.568052

- Eichhorn, V. (2020). Social tourism to overcome social exclusion: Towards a holistic understanding of accessibility and its users. In A. Diekmann & S. McCabe (Eds.), Handbook of social tourism (pp. 177–194). Edward Elgar.

- Eriksson, P., & Kovalainen, A. (2016). Qualitative methods in business research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Feilzer, M. Y. (2010). Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: Implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809349691

- Ferrer, J. G., Sanz, M. F., Ferrandis, E. D., McCabe, S., & García, J. S. (2016). Social tourism and healthy ageing. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(4), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2048

- Finnish institute for health and welfare. (2020). Lapset ja perheet. Retrieved February 13, 2022, from https://thl.fi/fi/web/hyvinvointi-ja-terveyserot/eriarvoisuus/elamankulku/lapset-ja-perheet

- Fok, C. C. T., Allen, J., Henry, D., & Team People Awakening. (2014). The brief family relationship scale: A brief measure of the relationship dimension in family functioning. Assessment, 21(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111425856

- Hardcastle, S. J., & Blake, N. (2016). Influences underlying family food choices in mothers from an economically disadvantaged community. Eating Behaviors, 20, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.11.001

- Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Bornemann, T. (2009). Implementing the marketing concept at the employee-customer interface: The role of customer need knowledge. Journal of Marketing, 73(4), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.4.064

- Hunter-Jones, P., Sudbury-Riley, L., Al-Abdin, A., Menzies, L., & Neary, K. (2020). When a child is sick: The role of social tourism in palliative and end-of-life care. Annals of Tourism Research, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102900

- Hyvinvointilomat ry. (2018). Toimintakertomus 2017.

- Kakoudakis, K. I. (2020). Counterbalancing the effects of unemployment through social tourism. In A. Diekmann & S. McCabe (Eds.), Handbook of social tourism (pp. 195–208). Edward Elgar.

- Kakoudakis, K. I., McCabe, S., & Story, V. (2017). Social tourism and self-efficacy: Exploring links between tourism participation, job-seeking and unemployment. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.005

- Keniger, L., Gaston, K., Irvine, K. N., & Fuller, R. (2013). What are the benefits of interacting with nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(3), 913–935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030913

- Komppula, R., & Ilves, R. (2018). Social tourism as correlates of QoL: The case of disadvantaged people. In M. Uysal, M. J. Sirgy, & S. Kruger (Eds.), Managing quality of life in tourism and hospitality (pp. 54–69). CABI.

- Komppula, R., Ilves, R., & Airey, D. (2016). Social holidays as a tourist experience in Finland. Tourism Management, 52, 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.016

- Komppula, R., & Vento, E. (2021). Challenges and opportunities for development of social tourism in Finland. In J. Lima & C. Eusébio (Eds.), Social tourism: Global challenges and approaches (pp. 30–40). CABI.

- Lima, J., & Eusébio, C. (2020). Economic benefits of social tourism: Theoretical reflections and insights for management. In A. Diekmann & S. McCabe (Eds.), Handbook of social tourism (pp. 43–58). Edward Elgar.

- McCabe, S. (2009). Who needs a holiday? Evaluating social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 667–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.06.005

- McCabe, S., & Diekmann, A. (2015). The rights to tourism: Reflections on social tourism and human rights. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1049022

- McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001

- McCabe, S., Joldersma, T., & Li, C. (2010). Understanding the benefits of social tourism: Linking participation to subjective well-being and quality of life. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(6), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.791

- McCabe, S., & Qiao, G. (2020). A review of research into social tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103103

- Minnaert, L. (2012). The value of social tourism for disadvantaged families. In H. Schänzel, I. Yeoman, & E. Backer (Eds.), Family tourism: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 93–104). Channel View Publications.

- Minnaert, L. (2020). Stakeholder stories: Exploring social tourism networks. Annals of Tourism Research, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102979

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2006). Social tourism and its ethical foundations. Tourism Culture & Communication, 7(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830406778493533

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2009). Tourism and social policy. The value of social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 316–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.01.002

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2011). What is social tourism? Current Issues in Tourism, 14(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.568051

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Sedgley, D. (2015). Social tourism and well-being in later life. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.015

- Neideen, T., & Brasel, K. (2007). Understanding statistical tests. Journal of Surgical Education, 64(2), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.02.001

- Pyke, J., Pyke, S., & Watuwa, R. (2019). Social tourism and well-being in a first nation community. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.04.013

- Schänzel, H. A., & Yeoman, I. (2014). The future of family tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 39(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2014.11087005

- Smith, V., & Hughes, H. (1999). Disadvantaged families and the meaning of the holiday. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-1970(199903/04)1:2<123::AID-JTR146>3.0.CO;2-R

- STEA. (2021). Funding Centre for Social Welfare and Health Organizations. Retrieved December 29, 2021, from https://www.stea.fi/en

- Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences. Sage.

- Veikkaus Oy. (2021). Veikkaus’ profit fell significantly due to the coronavirus epidemic. Retrieved December 29, 2021, from https://www.veikkaus.fi/fi/yritys#!/article/tiedotteet/yritys/2021/03-maaliskuu/01_veikkaus-year-2020

- Vento, E., & Komppula, R. (2020). Social tourism practices and implementation in Finland. In A. Diekmann & S. McCabe (Eds.), Handbook of social tourism (pp. 244–255). Edward Elgar.

- Vento, E., Tammi, T., McCabe, S., & Komppula, R. (2020). Re-evaluating well-being outcomes of social tourism: Evidence from Finland. Annals of Tourism Research, 85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103085