ABSTRACT

Mega-sport events (MSE) are frequently cited for their developmental and legacy potentials for host communities, including tourism, sport participation and volunteering. MSE volunteer research has demonstrated the potential to develop volunteers who may contribute to the host community’s social and human capitals. However, little research considers how marginalised groups, such as First Nations or those with disability, may be co-providers of MSE experiences. This paper differs from a dominant quasi-scientific approach to empirical journal articles in that it begins with a reflexive posture drawing upon First nations pedagogy of storytelling. Reflecting upon the volunteers’ social context and drawing upon a dataset of volunteers across 6 MSE in 5 countries (2009–2016), this research explores to what extent First Nations volunteers are considered and included in MSE research and practice, and what differences may exist between First Nations volunteers and others regarding their motivations and future volunteering intentions. The results indicate that significantly more can be done to include First Nations people equitably and respectfully across the design, delivery, and legacy potential of MSE. The results inform a novel framework that provides a map for theory and practice, and thus praxis, for incorporating marginalised groups as full partners across the MSE journey.

Introduction

As we begin, we wish to acknowledge the Ngarigo, Ngunnawal and, Gadigal people who are the traditional custodians of the land upon which we write and upon whose shoulders we stand. We acknowledge their continuing connection to land, skies, and sea, and we pay our respects to their Elders, past, present, and emerging. We also wish to acknowledge the Awabakal people from whom one author, Stirling Sharpe, has descended.

Throughout this article we use Aboriginal, or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, to refer to the first people of Australia in line with the style manual of the Australian Government (Citation2021). We acknowledge that these broad terms have been imposed upon the first people of Australia without consultation and that some may not be comfortable with this terminology. First Nations is used as a collective term to describe the first people of all the countries from which our data has come. We further acknowledge that this grouping of various indigenous people into one term does not recognise the uniqueness of each country’s indigenous people, thus we use the term to highlight issues that are apparent across the globe. In this paper, the focus is upon First Nations’ participation and voices in MSE where the research is dominated by WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic) (Henrich et al., Citation2010) voices, despite the growing role of ‘other’ hosts, especially from BRICS countries, i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (Dickson et al., Citation2020).

This paper is structured differently to many academic articles as the typical structure does not adequately allow for the desired story to be told. Here, we are reflecting on an Aboriginal pedagogy of storytelling (Chilisa, Citation2012; Yunkaporta & Kirby, Citation2011) or the use of storytelling to share information. Our story begins with a reflection on the academy, ourselves as researchers, and MSE research. The next segment of our story is related to our research where our results, existing literature, and modern examples are all combined to lead the reader to the conclusions presented in our final sections. We’ve approached our work from a strength-based perspective which points towards a positive, more inclusive, MSE future.

It is notable that in a special issue on empowering marginalised groups that we, the authors, demonstrate the complexity of doing research on marginalised groups, often just for the benefit of the researchers and not the researched (Sharmil et al., Citation2021). Collectively we fit within three of what may be considered marginalised and, at times, vulnerable groups: female, Aboriginal, and disabled (Rastegar et al., Citation2021). Yet, we are also part of what may be considered the oppressors or dominating classes in that we all come from WEIRD societies. Thus, to reflect upon and include the complexity of our own diverse lived experiences as consumers, providers, educators, and researchers of tourism and recreation, we approach this article in a critically reflexive manner, including of ourselves and our work, consistent with pragmatic critical realism’s (PCR) epistemic reflexivity (Johnson & Duberley, Citation2000).

A pragmatic critical approach

Criticality is a contested term as its meaning reflects many users’ understandings of their world (Brookfield, Citation2005). It is more than just identifying dominant ideologies or hegemonies, it includes thinking, being, and acting (emphasis in the original, Davies & Barnett, Citation2015, p. 15). Critical theory seeks to understand the current state of affairs prior to seeking to change it (Brookfield, Citation2015).

A critical approach helps identify whose voices are missing, and who may be dominating the discourse and crowding out the ‘others’ or the ‘othered’ (Small & Darcy, Citation2011; Young, Citation2011). Increasingly authors acknowledge that not everyone comes from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) societies and so our understanding of theory of practice may need to be more critical of the underpinning, often Eurocentric, research in our fields (Dickson & Gray, Citation2022; Henrich et al., Citation2010). This is also true of tourism, recreation, and events where discourse is dominated by Western perspectives (Nielsen & Wilson, Citation2012; Walters et al., Citation2021).

Frequently academics stop short of moving from theory to practice, especially with marginalised groups. Advocacy and policy-making requires different understandings and skill-sets to translate research findings into active engagement with political processes, and working with rather than for or on marginalised people (e.g. Darcy, Citation2019). Certainally, how the Academy values this practical work may vary and many academics with marginalised identities have expressed their experiences of privileging practices that directly or indirectly discriminated against them, dismissing the asset of their lived experience (Yerbury & Yerbury, Citation2021).

Freire (Citation1972) states, liberation can be achieved through ‘praxis: reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it’ (p. 51). Thus, we will reflect upon where we are in theory and practice, not just to identify a problem but to guide the next steps for both theory and practice, in order to transform it. Because, in PCR knowledge should serve ‘to guide and shape human activities, that is, its practical and political consequences’ (Johnson & Duberley, Citation2000, p. 175). This is achieved here via a novel framework to guide researchers and practitioners interested in facilitating the full and equitable involvement of marginalised groups, as a tangible and reciprocal outcome of this research.

Marginalisation, oppression, missing voices, and opportunities lost

Marginalisation can either mean the process of marginalisation or an outcome. Groups are marginalised, not by who they are, but by who the dominant groups are that marginalise, oppress, and discriminate either directly or indirectly, e.g. recently the #wethe15 campaign highlights missing voices in disability discourses. We are asked to consider who is stopping the ‘15’ from participating fully in society, leading to explore #wethe85 who dominate discourse and practice, thus disabling people with impairments (Darcy & Dickson, Citation2021). Domination gives rise to considerations of power (Walters et al., Citation2021). Rather than trying to work out who has power over whom, one simple way is to look at the grammar in use especially the prepositions that explain relationships between groups, even between the researcher and the researched, e.g. with, to, for, between, over, and under.

Carnicelli and Boluk (Citation2020) suggest that ‘mega-event and sport tourism provides further examples of tourism as an oppressive tool for neoliberal and neo-colonial practices’ (p. 720). The oppressive potential is made even more complex when event ‘hosts’ use the games-time détente to obfuscate social and political aggression. For example, Russian military activity in the period between the Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games and again between the Beijing 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, resulting in the war against the Ukraine, reigniting debates about sport-washing where sport and events are used to legitimise and ‘cleanse’ countries from the stain of their human-rights abuses, oppression, and segregation (Amnesty International, Citation2021).

To explore how First Nations peoples are positioned in tourism research, Nielsen and Wilson (Citation2012) proposed four categories: invisible, identified, stakeholder, or Indigenous-driven. However, this overlooks the voice of First Nations people as tourists from the demand-side and does not effectively consider how they may also be the providers of a product, service, or an experience in an entrepreneurial sense, not just performers or actors on the supply-side of experiences. Thus we propose extending the dance analogy of Larsen and Urry (Citation2011) with its two distinct roles; observers of the dance, as in the tourist gaze, vs. dancing together, as with performance. In the mega-sport event (MSE) dance/space this may be too restrictive as there are many more roles people may ‘play’, e.g. managing, hosting, venue ownership, marketing, finances, transport, watching, providing music, and dancing. Extending the dance analogy, we are interested in exploring how, in practice, First Nations people may contribute, lead, and participate across all areas of MSE design and delivery, and not just in a performative sense frequently observed in Opening Ceremonies.

A desirable goal would be when ‘business as usual’ means that First Nations people are not an afterthought but are genuinely involved across all aspects and over the life of the event and legacy realisation. Of course, this requires relationships to be built with First Nations’ people so they have ‘a seat at the table’ as co-designers, planners, and decision-makers as will be discussed later in the paper.

As we are not interested in First Nations people being objects of the tourist gaze but equal providers and beneficiaries of the event and tourism experience, we seek to understand the motives and legacy potentials of MSE volunteers who identified as being First Nations people of the host country in order to transform theory and practice. Thus the results from the following research questions inform the development of a novel framework to guide future research and practice, such as with the planned Vancouver 2030 bid.

To what extent have First Nations groups been included and considered in the research and the practice of MSE, and

What differences may exist between MSE First Nations volunteers and others regarding: who is volunteering, their motivations for volunteering and the volunteer legacy potential?

Method

Guided by pragmatic critical realism we adopt a mixed methods approach that provides a proverbial map of our reflexive research journey that respects the oral storytelling and visual traditions of First Nations people (Chilisa, Citation2012). Thus, firstly by considering Foucault’s paraphrase of Kant, ‘What are we? in a very precise moment of history’ (Foucault, Citation1982, p. 785) we reflect upon where we are currently in our theory and practice, as revealed in the extant research, before we commence a journey to change it (Brookfield, Citation2015).

Secondly, we draw upon data collected from MSE volunteers who were surveyed across four Olympic and Paralympic Games in Canada (Vancouver 2010), United Kingdom (London 2012), Russia (Sochi 2014), and Brazil (Rio 2016), one World Master Games (Sydney 2009) and one FIFA Women’s World Cup (Canada 2015). The online survey included questions related to previous volunteering experience, motivations for volunteering, and intention to volunteer more after the Games, i.e. the legacy potential. This section of the research was approved by the lead University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (09–88) and also the International Paralympic Committee’s Sports Science Committee.

Chi-square tests and ANOVAs explored the differences in gender, age, previous volunteering experience and future volunteering intentions between those who identified as First Nations and all other respondents (Veal & Darcy, Citation2014). Independent sample t-tests analysed differences in the means of the 36 motivation items. While previous analysis has reduced the motivation dimensions through Principal Component Analysis (e.g. Dickson et al., Citation2013; Dickson et al., Citation2015; Dickson et al., Citation2022, in press), the sample here is not suitable as the number of First Nations responses (n = 108) is less than the recommended 10–20 times the number of motivation items (n = 36) (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Results

Where are we?

First Nations research, research methods and the academy

It is tempting to write about some meta-narrative about First Nations research but that would be disingenuous given the diversity of cultures, languages, and traditions of the many First Nations people throughout the world. Yet we accept that there is a disconnect between reporting upon a research project driven by dominant Western research paradigms while also seeking to hear the voices of First Nations within that data (Chilisa & Denborough, Citation2019). Partly this disconnect is driven by a neoliberal agenda that underpins many higher education and research arenas where productivity and impact is deemed quantifiable (Dickson & Gray, Citation2022). One could reflect upon the extent to which the dominant and privileged paradigms systematically exclude the voices of ‘others’, thus minimising the reciprocal benefits that may remain for marginalised groups through research and in policy and practice.

While we draw upon the growing body of collective First Nations’ knowledge and theory development, we note the dearth of research with First Nations people as volunteers, and thus co-providers of events and tourism. For example, Hoeber (Citation2010) reported upon two Canadian events that may be considered regional or hallmark according to Getz’s portfolio approach (Getz & Page, Citation2016). Thus the scale and specific sociocultural context may, or may not, have relevance for MSE. Then there is some recent research on non-Indigenous volunteers at a First Nations hallmark event (Chen & Mason, Citation2022).

How will things change if we, the Academy, do not know what is required? For theory and practice to be decolonised, not only do we need to appreciate different ways of knowing and being we need appropriate content to inform and guide curricula by embedding First Nations ways of knowing, being, and researching (Chilisa, Citation2012; Yunkaporta & Kirby, Citation2011). We are warned to not ‘bring in Indigenous knowledge and plonk it in the curriculum unproblematically’ (Nakata, Citation2007, p. 8). Further, it is vital that we do not simply silo, or ‘other’ it, in specialist First Nations units (Chilisa, Citation2012). Indigenising curricula is not limited to using case studies of First Nations people but extends to imbedding respectfully the use of First Nations’ more relational and non-linear ontologies, epistemologies, and pedagogies across all learning experiences.

By developing content, pedagogy, and research agendas and methods that considers the role, representation, and rights, of First Nations peoples in tourism, recreation, and events, future graduates will have a broader array of knowledge and skills enabling them to move beyond hegemonic colonising and oppressing strategies in theory and practice (Chilisa, Citation2012). Thus, we must balance the disparities experienced by marginalised groups that not only ‘flow from isolation, discrimination, acculturation, and/ or lack of power’ (Braun et al., Citation2014, p. 124), but also from lack of representation and information from which the more powerful ‘others’ may also learn and change.

Beyond the tourist gaze: First Nations' representation in tourism and events

Urry’s (Citation2011) seminal work on the tourist gaze has been influential in critiques of the commodification of First Nations tourism. For example Bunten (Citation2010) notes the risk of self-commodification or auto-exoticism where First Nations cultures are ‘fixed in a pre-colonial past, where men and women on display follow gender roles, wear modern interpretations of pre-contact garb, and perform edited versions of traditional songs and dances’ (pp. 53–54). We see this in many tourism and event contexts where First Nations culture is shared through performances by actors, in sometimes stone-age traditional dress, disconnected from their authentic and lived experiences of connection to family, community, and place as a living dynamic, and contemporary culture. This cultural production for tourist consumption risks misleading the observer about how cultural practices have evolved while requiring the actors to simplify their rich and enduring cultures into saleable packages for the tourists’ gaze. Further, constricted time periods fit the commoditised space (such as performances and Acknowledgements of Country) of what may have taken place over many days, while increasingly these performances are captured (or taken) and shared via social media for consumption by a possibly less informed and culturally disconnected audience.

Objects not creators: First Nations' participation and representation in mega sport events

MSEs' have often made First Nations people and culture a centre-point of opening ceremonies. National identity of the host country is given prominence in the ceremonies, and provide significance to the Games outside of pure athleticism (Gilbert, Citation2014). For example, at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games one of the ‘most powerful and enduring themes of the Games was Indigenous Australia’ (Rowe, Citation2020, para 18). The opening ceremony featured four segments related to pre-colonisation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders history: Deep Sea Dreaming (referring to the Aboriginal Dreamtime), Awakening, Fire and Nature, and Eternity, (e.g. Heinz Housel, Citation2007; White, Citation2013). The ceremony concluded with the Olympic Cauldron being lit by Aboriginal woman Cathy Freeman, a descendent of the Kuku Yalanji and Burri Gubba people. Days later, Freeman won Gold in the 400 m sprint (track and field). White’s suggestion that the tone set in the opening ceremony continued throughout the Games is not uncontested. Heinz Housel (Citation2007) argued that the performance placed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the past, valued them below their white colonial invaders, and was told from a white perspective, thus missing the opportunity to position and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as individuals and communities with agency and invaluable insights to share.

Sport events and tourism

However, MSE, including the inbound tourism opportunities, have often been discussed for their developmental and legacy potentials for host communities (Dickson, Misener, et al., Citation2017; Schulenkorf, Citation2017), such as social and human capitals including resident’s wellbeing (Dickson et al., Citation2020). Yet, little research considers how marginalised groups, such as First Nations, or those with disability, may be co-producers and beneficiaries of MSE experiences, not just exotic objects of curiosity (Darcy et al., Citation2014).

Are First Nations people front of mind for event organisers and researchers?

From six MSE, survey responses were received from 23,630 volunteers. Of the six events, only three specifically asked about First Nations identification: Vancouver 2010 (2.8%), Rio 2016 (0.8%), and the Sydney World Masters 2009 (SWMG) (0.5%). It is possible that one volunteer with the FIFA Women’s World Cup, 2015 would also identify as First Nations as indicated by the language spoken at home, however volunteers were not specifically asked if they identified as First Nations. Thus, only data from SWMG 2009, Vancouver 2010, and Rio 2016 will be analysed further (n = 8014), of which 1.3% identified as First Nations.

Prior to the SWMG the estimated resident Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [sic] population of Australia was 2.5% (ABS, Citation2012). During Vancouver 2010, 4.3% of Canadians reported an Aboriginal [sic] identity (Statistics Canada, Citation2013), and 0.4% of the Brazilian population were estimated to identify as Indigenous [sic] at the time of Rio 2016 (CIA, Citation2017).

Who, why, and what next?: differences between First Nations volunteers and other volunteers including their motivations and legacy potentials

As reported in , chi-squared tests for independence and ANOVAs indicated no significant differences between First Nations and others and the proportion of, (i) females to males, (ii) those who had previous volunteer experience, nor (iii) future volunteering intentions, and thus legacy potential. However, there were significant differences in (i) age groups and (ii) employment situation. First Nations volunteers were generally older (69.4% over 25 years, vs. 43.3% of non-Indigenous respondents); more were involved in paid employment (70.9% vs. 62.9%); none were unemployed or looking for work (0% vs. 9.0%); and less were fulltime students (2.9% vs. 9.6%).

Table 1. Demographics and between-groups analysis comparing First Nations vs All Others across 3 events (Sydney, Vancouver, and Rio).

Of the 36 motivations items, the independent samples t-test indicated significant differences in scores for those who identified as First Nations and all others in 15 items ().

Table 2. Independent samples t-tests comparing volunteering motivations of First Nations and all others across 3 events (Sydney, Vancouver, and Rio).

Discussion

The discussion is structured around the research questions that informs the development of a new research framework to guide future research and practice related to marginalised groups:

To what extent have First Nations groups been included and considered in the research and the practice of MSE, and

What differences may exist between MSE First Nations volunteers and others regarding who is volunteering, their motivations for volunteering and the volunteer legacy potential?

Firstly, though, in response to the call ‘to embrace more reflexive and critical paths of inquiry’ (Wilson et al., Citation2008, p. 15), or to be epistemically reflexive, we begin this discussion by declaring that we as researchers have not always had marginalised groups front-of-mind in our research, even though between us we identify with at least three marginalised identities, Aboriginal, women, and people with disability. This reflects Marcuse’s (1964) suggestion that, ‘critical theory is, last but not least, critical of itself and of the social forces that make up its own basis’ (cited in Brookfield, Citation2015, p. 533). Sadly, a great deal of our own scholarship may be regarded as colonising, paternal, and without true co-design principles of working with marginalised groups.

Thus, if we were to be true to First Nations ways of knowing and research (Chilisa, Citation2012; Kurtz, Citation2013) we would not conduct, nor report upon, research that is not Indigenous-led or co-created for the benefit of Indigenous people, as we do here. With 2020 hindsight we would do as Chilisa suggests, ‘research needs to have a clear stance against the political, academic and methodological imperialism of whatever time and place we are in’ (Chilisa & Denborough, Citation2019, p. 13). Yet have we been seduced by the dominate and privileged Western research paradigm, by using and reporting upon a large-scale quantitative research program? Or are we just playing along with the tacit hegemonic rules that often exclude other voices? We argue that by our reflexive efforts here to identify our own shortcomings, along with the leadership of an Aboriginal researcher on our team, we are able to take our small, at times metaphorical, steps to highlight an area that is truly under-researched. Our novel framework is a step towards reciprocity.

First Nations groups front of mind in the research and the practice of MSE

Perhaps the most telling sign that First Nations have not been front of mind in research is that of the six MSE’s reported only three asked if volunteers identified as First Nations. In practice, it is evident for Sydney and Vancouver that the percentage of First Nations volunteers (2.8% and 0.5%) is well below the percentage of First Nations people in each country’s residential population (4.3% and 2.5%). For Rio, the result is different with more First Nations volunteers (0.8%) than the population (0.4%). Underrepresentation may reflect the lack of strategic human resource strategy (Dickson & Darcy, Citation2022, in press) to recruit and manage First nations volunteers.

However, over the period of the research there has been a growing awareness of the need for and importance of authentically including First Nations peoples in all areas of tourism, sport, and events. This is particularly reflected in changing policies and practices in sport management and sport for development, explored later, to work towards reconciliation.

Who, why, and will they do it again?

Analysis of this albeit relatively small sample of people from three MSE who identify as First Nations raises the question as to whether there are socioeconomic barriers to their MSE volunteering. While many already volunteer in other contexts, those who volunteered for a MSE were more likely to be in paid employment, and less likely to be fulltime student or unemployed. However, if First Nations people reside away from MSE host communities their volunteering in the Games requires a substantial investment of time and finances (to pay for travel, accommodation, meals). Of course, a more holistic explanation for that would require qualitative examination or a mixed methods study that also collected expenditure data.

shows that First Nations volunteers had higher mean scores on 28 of 36 items with 15 statistically significant. Notably, of the eight items where First Nations scored lower, most were ‘self-serving’ or transactional items such as item 32, I wanted to make job contacts and 19, being a volunteer at the Games is considered prestigious. Meanwhile, significantly higher scores were recorded for community-based, or altruistic items such as item 2, I want to give back to the host city and 24, I wanted to put something back into the community. This suggests that First Nations volunteers are community oriented which is congruent with many First Nations ways of being, and aligns with earlier research (Hoeber, Citation2010).

This research is a snapshot in time, however longitudinal research may provide more context. For example, VanWynsberghe and Pentifallo (Citation2014) when reporting on the Olympic Games Impact study stated that ‘the percentage of Aboriginal participation in VANOC jobs decreased rapidly in 2008–2009, from 11% to 13% in the first two years [2006–2008], to 1% to 3% in the last two periods [2008–2010]’ (p. 261). This suggests structural issues in the ongoing First Nations volunteering with VANOC.

Similarly, Darcy et al. (Citation2014) in a qualitative study of London 2012 volunteers identified a series of interpersonal, structural, and attitudinal barriers that led to unsatisfied experiences by volunteers with disability. This accelerated in the lead up to and during the games as those directly managing people with disability were brought on board late and were not prepared adequately to manage people with disability and their individual reasonable adjustments. Notably this occurred at a MSE where inclusion of people with disabilities as volunteers was important to Sebastian Coe, the chair of the London OCOG (Dickson, Darcy, et al., Citation2017) and where the 6000 applications from people with disabilities to be a volunteer was widely celebrated (Channel Citation4, Citation2010). Good intentions were not enough.

Thus, for volunteers from marginalised groups to be full partners in MSE design and delivery, they not only need to be ‘at the table’ where decisions are made, there needs to be a societal and cultural shift where full and equitable inclusion of marginalised groups is ‘business as usual’ and not a special policy or an afterthought. This requires marginalised groups having an equitable voice and participation in planning, design, and delivery. Later we consider two recent examples that may suggest that the tide is beginning to turn, at least for First Nations peoples.

Was there a potential volunteer legacy?

A volunteer legacy may mean more people volunteering after the event or the same people volunteering more. While the results here do not show any significant difference between First Nations and other volunteers regarding their future volunteering intentions (), future events organisers need to critically reflect upon the availability of these volunteers for increased volunteering post-event. Already First Nations volunteers were volunteering more before the games than other volunteers.

Further, it is well known that marginalised and minority groups can be called upon to do what may be called ‘cultural labour’ across all areas of society. Cultural labour may be defined as,

labor that people perform as members of a human group defined in terms of cultural identity – not as “independent” laborers, not as “professionally skilled” laborers, but as members of a particular ethnic group whose identity shapes the form, function, and meaning of that labor. (Angosto-Ferrández, Citation2021, p. 67)

Cultural labour places additional demands within work and the community upon those peoples because of their ethnicity or identity. This is not required of the dominant groups. This additional work is also often unpaid. In the case of MSE’s there is a requirement on the event organisers to be cognizant of cultural labour and carefully consider, in conjunction with local First Nations communities, the delineation between what could be reasonably expected of a volunteer and what roles should be paid. It is our assertion that the closer a position comes to cultural labour, the greater the expectation that the role should be paid.

What next?

Are there lessons from sport and sport for development?

Sport and ‘sport for development’ may provide examples from which MSE may learn. Sport for Development, as opposed to sport development (i.e. pathways to develop athletes), is a concept whereby sport and physical activity are used as a vehicle to create social change (Schulenkorf, Citation2017).

For example, Australia has witnessed a rapid growth in sport organisations interested in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, providing dedicated competition rounds and programs to encourage participation and promote, and working towards, reconciliation. This is supported by expressing a formal commitment toward redressing inequality and promoting reconciliation via Reconciliation Action Plans (RAPs). Sport and MSE examples includes the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Corporation (GOLDOC) and the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC). Matt Carroll, the AOC Chief Executive Officer, prefaced the AOC RAP with this message:

We are committed to accelerating the integration of the Olympic movement into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities and equally ensuring Indigenous culture and traditions are cherished within the Olympic movement … The AOC is aware that reconciliation requires a commitment to meaningful, sustainable and practical initiatives for our Indigenous communities. This Reflect RAP further commits us to that path. (AOC, Citation2021, p. 5)

For all organisations delivering sport based First Nations programs (worldwide, not just in Australia), it is important to consider the specific cultural contexts and protocols in the communities in which the program will operate. This avoids considering all First Nations people or communities as one homogenous group. Further, collaboration in planning and operations empower communities, ensure culturally appropriate inclusion, and ensuring mutually beneficial outcomes can be achieved. (Atkinson, Citation2002; Marika et al., Citation1992; Thomson et al., Citation2010). The lessons to be learnt from sport and sport for development is that the more authentic the collaboration with First Nations people is, the greater the impact of may become. Outcomes here are therefore co-designed and not driven wholly by Western paradigms embedded in MSE. Similarly, while national governing bodies and MSEs may not have the localised connections with community, we see them as having leading roles in setting the direction for their sport and their affiliated bodies. The examples from the AOC above and GOLDOC folliwing are signals of change.

Is the tide turning? Recent efforts to authentically engage First Nations groups across the MSE journey

Since this research was conducted there are two examples of how MSE organisers and communities have endeavoured to engage First Nations groups as co-providers, co-creators, and even leaders, not just performers in the MSE dance. They are the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games and the Vancover 2030 planned bid.

The Gold Coast Commonwealth Games (2018) is perhaps the most advanced example to date. Relevant here, the GOLDOC RAP included a commitment to increase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteer representation and employment and training (item 1.13 and 1.7; https://gc2018.com/rap). The Indigenous Volunteer Support Program (IVSP) was created that supported 28 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteers from 74 applicants from remote and regional communities to participate as Game Shapers or Games volunteers. This was 12% of the reported 225 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteers from the estimated 15,000 volunteers (1.5%) (CIRCA, Citation2018). The IVSP provided accommodation and travel to ensure the volunteering opportunity was accessible for those from remote and regional communities. Importantly, the volunteer training program included ‘a strong Indigenous theme’ reflecting that the RAP influenced the training (CIRCA, Citation2018).

Regarding employment and procurement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, GOLDOC employed 29 staff, 13 trainees, and supported 3 interns, and over 600 more were employed by contractors and sub-contractors (CIRCA, Citation2018). While the evaluation highlighted many shortfalls and suggested improvements it is encouraging to see genuine consultation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, communities, and businesses in developing and delivering the Games.

Looking forward, the planned Vancouver 2030 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games bid is the first Indigenous-led bid. It is a collaboration between four First Nations communities, Líl̓wat (Lilwat), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations and the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Committees. The Games are touted as an opportunity for the world to gather in British Columbia (host province) to witness reconciliation in action (Dichter, Citation2022; Games Engagement, Citation2022). For Joseph Smith, of the Squamish First Nation,

an Indigenous-led bid means following calls to action regarding sport under the report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – No. 91 calls for officials and host countries of major sporting events “to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ territorial protocols are respected, and local Indigenous communities are engaged in all aspects of planning and participating in such events … an Indigenous-led process … the Nations hosting that gathering and inviting others to be with them in a family environment’ and that ‘It means following the leadership of the Indigenous partners and that basically in a nutshell is respect, inclusivity and community … We are working on this feasibility work all at the table together, bringing the strengths that each of our groups”. (Dichter, Citation2022, n.p.)

The Vancouver 2030 concept released on 23 June 2022 had not yet reached the level of detail around staffing and volunteers. However a question that emerges from this innovative proposal is what will be the role and social legacy potential for other First Nations communities who may be impacted but not leading the bid, such as those connected to the proposed BC interior venue of Sun Peaks, Little Shuswap Lake [Band], Adams Lake [Band] and Neskonlith [Indian Band] (Empey, Citation2022).

Next steps: a new framework to guide future research and practice

This research highlights the need to explore to what extent, and how, vulnerable, and marginalised groups, such as First Nations, may be key stakeholders, leaders, and co-creators in the bid, design, delivery, and legacy potential of MSEs.

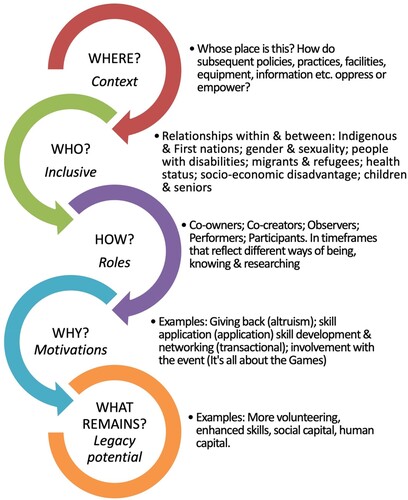

From this research the following novel framework () is proposed that refocuses theory and practice, and thus praxis (Freire, Citation1972) to ensure vulnerable and marginalised groups are considered, consulted, and included as equal partners across the design and delivery of events. This requires a societal and cultural shift to work with, or maybe even for those groups, in ways that respect their ways of being, knowing, doing, and researching, across both theory and practice.

From a theoretical perspective, this research highlights the WEIRD nature of much of our theory and research practice, particularly in the privileged leisure-related areas of tourism, recreation, sport, and events. Thus, for theory to move forward, particularly with respect to First Nations, we need to give voice, and to deeply listen to those marginalised groups. The academy needs to look beyond Western constructs and timeframes of knowledge, research, and governance to respectfully learn and implement socially-situated Indigenous ways of knowledge and research that may have different ontological, methodological, and ethical practices from the dominant Western paradigm (e.g. Chilisa, Citation2012; Somerville & Turner, Citation2020). Working with First Nations communities is built upon relationships and should be for the betterment of the community. Commercial or Academy goals and outputs are secondary to the community benefit. Relationship building takes time and this needs to be built into MSE planning. Additionally, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’s, their connection to Country, to Mother, needs to be respected – this is the essence of Aboriginality (Ngunnawal Elders, Citation2003).

In terms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research methods, we are aware of, and have used in the past, two methods that non-Indigenous researchers may consider respectfully applying in our first steps towards a more respectful and inclusive research, particularly with and for First Nations people. They are Ganma and Dadirri.

Ganma comes from the Yolngu community of Yirrkala in Australia’s Northern Territory (Thomson et al., Citation2010). The Ganma metaphor has been described as a respectful sharing of knowledge (Sharmil et al., Citation2021).

the situation where a river of water from the sea (in this case Balanda [white people] knowledge) and a river of water from the land (Yolngu knowledge) mutually engulf each other on flowing into a common lagoon and become one. In coming together the streams of water mix across the interface of the two currents and foam is created at the surface so that the process of ganma is marked by lines of foam along the interface of the two currents. In the terms of the metaphor, then the line of foam that is formed by the interaction of the two currents marks the interface between the current of Yolngu life and the current of Balanda life. Both Yolngu and Balanda can benefit from theorizing over the interaction between the two streams of life. (Marika et al., Citation1992, pp. 6–7)

the researcher would be obligated to return resource materials to the participants through a participant organisation, for their future use. These materials include the knowledges derived that arise from the research activities. (Atkinson, Citation2002, p. 21)

West et al. (Citation2012) sees the parallels between Freire’s critical pedagogy where ‘the principles on which [Freire’s] work is based are applicable to Dadirri’ (p. 1585), as it relates to humanisation and fighting the loss of humanity. The loss of humanity and agency is something many marginalised groups would identify with. To not engage directly with, for and/or under those ‘marginalised groups’ we risk replicating and reinforcing further what Freire termed cultural invasion,

cultural invasion is thus always an act of violence against the persons of the invaded culture, who lose their originality or face the threat of losing it. In cultural invasion (as in all the modalities of antidialogical action) the invaders are the authors of, and actors in, the process; those they invade are the objects. (Freire, Citation1972, p. 121)

Reflecting upon what we can learn from Gamma and Dadirri, combining and sharing knowledges, deep listening, and reciprocity seem important and relevant and ethical ways for any researcher to conduct research when working with people in and from any community, marginalised or not. Ganma and Dadirri need not remain as Indigenous-only methods. Thus, Ganma and Dadirri guides our next steps in a practical perspective informed by this research that demonstrates the need to focus efforts in MSE to recruit marginalised people, including First Nations, who can be leaders, co-designers, and co-providers across the MSE journey.

Understanding the context is the first step, i.e. where we are, who has gone before us, and how to respectfully acknowledge and engage with their histories. Then, who needs to be included, in planning, design, and delivery to ensure equitable voices, active listening but also create a culture that supports a willingness to try new things, even if we fail. Current relationships with the marginalised groups need to be assessed and, if required, new relationships built. Considering how people from different marginalised groups will be involved in the planning, design, and delivery of this metaphorical ‘dance’ and the necessary timeframes to respect their needs. Exploring the different volunteering motivations, to match and facilitate a positive volunteering experience for all. Then having a clear picture of what and how volunteer legacies may remain for individuals, organisations, and communities alike as part of the broader event legacy plans that embodies the Dadirri principle of reciprocity.

In focusing upon First Nations people, this paper demonstrates how marginalised people may be excluded from being equitable partners in the theory and practice of the MSE journey. However, there is also evidence that the tide may be turning and that organising committees may be seeing that First Nations people may be involved in all aspect of MSEs, if only the dominant voices will listen deeply. Further, the novel framework provides a map of how practically marginalised people may be involved across the whole of the MSE design, delivery, and legacy journey.

Despite the relatively small sample analysed in this paper, we believe that it is important that this discussion be progressed, and we encourage the Academy, in collaboration with First Nations people, to continue the discussion. Only when First Nations people are authentically included and have a seat at the table can we achieve reconciliation. This is a collaborative process, and we encourage researchers to value risk taking and reflexivity in their research. In echoing the words of the IMF founder and world marathon champion, Robert de Castella, reconciliation requires us to move forward, together, side by side, one step at a time – running, not walking, because walking takes too long (de Castella, Citation2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the many thousands of volunteers whose time, efforts, and considerable sacrifices make MSEs, and even grassroot sports, possible. Particularly, we wish to acknowledge all First Nations volunteers and those who come from other marginalised groups in society. We hear you, we see you, and we thank you.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amnesty International. (2021). “Sportswashing” and Australian football: Why human rights policy is urgently needed. Retrieved May 31, from https://www.amnesty.org.au/sportswashing-and-australian-football/

- Angosto-Ferrández, L. F. (2021). Cultural labor and the defetishization of environments: Connecting ethnographies of tourism in Venezuela and Chile. Dialectical Anthropology, 1–18.

- Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails, recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex Press.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2012). 4713.0 – population characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006. Retrieved March 1, from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4713.0

- Australian Government. (2021, September 6). Style manual: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.stylemanual.gov.au/accessible-and-inclusive-content/inclusive-language/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples

- Australian Olympic Committee (AOC). (2021). Reconciliation action plan June 2021–June 2022. https://content.olympics.com.au/public/2021-06/AOC%20Reconciliation%20Action%20Plan_June%202021.pdf

- Braun, K. L., Browne, C. V., Ka’opua, L. S., Kim, B. J., & Mokuau, N. (2014). Research on Indigenous elders: From positivistic to decolonizing methodologies. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt067

- Brookfield, S. D. (2005). The power of critical theory for adult learning and teaching. Open University Press.

- Brookfield, S. D. (2015). Speaking truth to power: Teaching critical thinking in the critical theory tradition. In M. Davies & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 529–543). Palgrave.

- Bunten, A. C. (2010). Indigenous tourism: The paradox of gaze and resistance. La Ricerca Folklorica, 51–59.

- Carnicelli, S., & Boluk, K. (2020). Critical tourism pedagogy: A response to oppressive practices. The Sage Handbook of Critical Pedagogies, 717–728. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526486455.n69

- Channel 4. (2010). Six thousand disabled people volunteer for London 2012. Channel 4 News. https://www.channel4.com/news/disabled-volunteers-for-london-2012-top-6-000

- Chen, C., & Mason, D. S. (2022). When two worlds collide: The unsettling experiences of non-Indigenous volunteers at 2017 World Indigenous Nations Games. Leisure/Loisir, 46(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2021.1945944

- Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage Publications.

- Chilisa, B., & Denborough, D. (2019). Decolonising research: An interview with Bagele Chilisa. International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, 1, 12.

- CIA. (2017). The world factbook: Brazil. Retrieved May 23, 2018, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/br.html

- Cultural and Indigenous Research Centre Australia (CIRCA). (2018). Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games reconciliation action plan evaluation report. https://www.publications.qld.gov.au/dataset/gold-coast-2018-commonwealth-games-reconciliation-action-plan-evaluation-report/resource/4b2dfd5d-3181-4510-a93d-44616f79929c

- Darcy, S. (2019). Leisure with impact: Research, human rights, and advocacy in a reflective review of a research career. Annals of Leisure Research, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1590723

- Darcy, S., & Dickson, T. J. (2021). Will #WeThe85 finally include #WeThe15 as a legacy of Tokyo 2020? In D. Jackson, A. Bernstein, M. Butterworth, Y. Cho, D. S. Coombs, M. Devlin, & C. Onwumechili (Eds.), Olympic and Paralympic analysis 2020: Mega events, media, and the politics of sport: Early reflections from leading academics (pp. 123). Centre for Comparative Politics and Media Research. https://olympicanalysis.org/section-5/will-wethe85-finally-include-wethe15-as-a-legacy-of-tokyo-2020-2/

- Darcy, S., Dickson, T. J., & Benson, A. M. (2014). London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Including volunteers with disabilities – a podium performance? Event Management, 18(4), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599514X14143427352157

- Davies, M., & Barnett, R. (Eds.). (2015). The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education. Palgrave.

- de Castella, R. (2022). Showcasing reconsiliation at @UniCanberra 10 am tomorrow Friday for 2k walk & 5k run … together side by side forward one step at a time, running not walking. #runsweatinspire @IndigMaraProjct. In @deek207 (Ed.).

- Dichter, M. (2022). Reconciliation through sport inspires Indigenous-led bid to bring the 2030 Olympics, Paralympics to B.C. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/canada-bid-2030-olympics-paralympics-1.6435837

- Dickson, T. J., Benson, A. M., Blackman, D. A., & Terwiel, F. A. (2013). It’s all about the games! 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games volunteers. Event Management, 17(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599513X13623342048220

- Dickson, T. J., & Darcy, S. (2022). Research note: Next steps in mega-sport event legacy research: Insights from a four country volunteer management study. Event Management, in press. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599522X16419948391285

- Dickson, T. J., Darcy, S., & Benson, A. M. (2017). Volunteers with disabilities at the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Who, why and will they do it again? Event Management, 21(3), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599517X14942648527527

- Dickson, T. J., Darcy, S., Edwards, D. A., & Terwiel, F. A. (2015). Sport mega-event volunteers’ motivations and post-event volunteering behavior: The Sydney World Masters Games, 2009. Event Management, 19(2), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599515X14297053839692

- Dickson, T. J., Darcy, S., & Pentifallo Gadd, C. (2020). Ensuring volunteer impact, legacy and leveraging is not “fake news”: Lessons from the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(2), 683–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2019-0370

- Dickson, T. J., & Gray, T. L. (2022). Nature based solutions: A vaccine and a salve in a neoliberal and COVID-19 impacted society. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2064887

- Dickson, T. J., Misener, L., & Darcy, S. (2017). Enhancing destination competitiveness through disability sport event legacies: Developing an interdisciplinary typology. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(3), 924–946. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0530

- Dickson, T. J., Terwiel, F. A., & Vetitnev, A. M. (2022). Evidence of a social legacy from volunteering at the Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Event Management, in press. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599522X16419948391267

- Empey, K. (2022). Sun peaks considered as venue for Olympics bid. Sun Peaks Independent News. https://sunpeaksnews.com/sun-peaks-considered-as-venue-for-olympics-bid/

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

- Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Penguin Books.

- Games Engagement. (2022, June 23). A future games: A future Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games in BC. Retrieved June 24, 2022 from https://www.gamesengagement.ca/learn-more

- Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2016). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.007

- Gilbert, H. (2014). “Let the games begin”: Pageants, protests, indigeneity (1968–2010). In T. J. E. Fischer-Lichte & S. I. Jain (Eds.), The politics of interweaving performance cultures: Beyond postcolonialism (pp. 156–175). Routledge.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage.

- Heinz Housel, T. (2007). Australian nationalism and globalization: Narratives of the nation in the 2000 Sydney Olympics’ opening ceremony. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 24(5), 446–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180701695348

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29. https://www.nature.com/articles/466029a.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

- Hoeber, L. (2010). Experiences of volunteering in sport: Views from Aboriginal individuals. Sport Management Review, 13(4), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.01.002

- Johnson, P., & Duberley, J. (2000). Understanding management research: An introduction to epistemology. SAGE.

- Kurtz, D. L. (2013). Indigenous methodologies: Traversing Indigenous and Western worldviews in research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900303

- Larsen, J., & Urry, J. (2011). Gazing and performing. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(6), 1110–1125. https://doi.org/10.1068/d21410

- Marika, R., Ngurruwutthun, D., & White, L. (1992). Always together, yaka gäna: Participatory research at Yirrkala as part of the development of a Yolngu education. Convergence, 25(1), 23.

- Nakata, M. (2007). The cultural interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100004646

- Ngunnawal Elders. (2003). United Ngunnawal Elders Charter. Retrieved May 31, from https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/72427/United_Ngunnawal_Elders_Charter.pdf

- Nielsen, N., & Wilson, E. (2012). From invisible to Indigenous-driven: A critical typology of research in Indigenous tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 19(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/jht.2012.6

- Rastegar, R., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Ruhanen, L. (2021). COVID-19 and a justice framework to guide tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103161

- Rowe, D. (2020). The Sydney Olympics: How did the ‘best games ever’ change Australia? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-sydney-olympics-how-did-the-best-games-ever-change-australia-145926

- Schulenkorf, N. (2017). Managing sport-for-development: Reflections and outlook. Sport Management Review, 20(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.11.003

- Sharmil, H., Kelly, J., Bowden, M., Galletly, C., Cairney, I., Wilson, C., Hahn, L., Liu, D., Elliot, P., & Else, J. (2021). Participatory action research-Dadirri-Ganma, using yarning: Methodology co-design with Aboriginal community members. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01493-4

- Small, J., & Darcy, S. (2011). Understanding tourist experience through embodiment: The contribution of critical tourism and disability studies. In D. Buhalis & S. Darcy (Eds.), Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues (pp. 73–97). Channel View Publications.

- Somerville, W., & Turner, B. (2020). Engaging with Indigenous research methodologies: The centrality of country, positionality and community need. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(2), 182–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443058.2020.1749869

- Statistics Canada. (2013). The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/130508/tdq130508-eng.htm

- Thomson, A., Darcy, S., & Pearce, S. (2010). Ganma theory and third-sector sport-development programmes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth: Implications for sports management. Sport Management Review, 13(4), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.01.001

- Ungunmerr, M.-R. (1988). Dadirri – inner deep listening and quiet still awareness. A reflection by Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr. Miriam Rose Foundation. Retrieved May 29, 2022, from https://www.miriamrosefoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Dadirri_Handout.pdf

- Urry, J. (2011). The tourist gaze (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- VanWynsberghe, R., & Pentifallo, C. (2014). Insights and investigations of the social legacies in the 2010 Winter Olympic Games: The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) study. In K. Young & C. Okada (Eds.), Sport, social development and peace (Vol. 8, pp. 245–275). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1476-285420140000008011

- Veal, A. J., & Darcy, S. (2014). Research methods for sport studies and sport management: A practical guide (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Walters, T., Stadler, R., & Jepson, A. S. (2021). Positive power: Events as temporary sites of power which “empower” marginalised groups. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

- West, R., Stewart, L., Foster, K., & Usher, K. (2012). Through a critical lens: Indigenist research and the Dadirri method. Qualitative Health Research, 22(11), 1582–1590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312457596

- White, L. (2013). Cathy Freeman and Australia’s Indigenous heritage: A new beginning for an old nation at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 19(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.670127

- Wilson, E., Harris, C., & Small, J. (2008). Furthering critical approaches in tourism and hospitality studies: Perspectives from Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 15(1), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.15.15

- Yerbury, J. J., & Yerbury, R. M. (2021). Disabled in academia: To be or not to be, that is the question. Trends in Neurosciences, 44(7), 507–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2021.04.004

- Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference (justice and the politics of difference). Princeton University Press.

- Yunkaporta, T., & Kirby, M. (2011). Yarning up Aboriginal pedagogies: A dialogue about eight Aboriginal ways of learning. In N. Purdie, G. Milgate, & H. R. Bell (Eds.), Two way teaching and learning: Toward culturally reflective and relevant education (pp. 205–213). ACER Press.