Abstract

This study analyzes official and family historical narratives, and their role in Muslim-Chinese identity formation in Southeast China, from the early Ming dynasty to the twentieth century. The narratives examined here are associated with the Chinese merchant-official Pu Shougeng (d. ca. 1296) and with the late-Yuan Muslim General Jin Ji (posted to Quanzhou in 1333). Both played crucial political and military roles in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Fujian. The families’ historical narratives – occasionally tightly linked, yet also representing conflicting interests and sentiments – strongly influenced the fortunes of Muslims in Quanzhou at large and especially those of the Pu and Jin lineages, whose descendants still live in Quanzhou and its surroundings. Under current political conditions, Muslim origin has become a desired token for asserting official Muslim-Chinese (Hui) ethnic identity. Thus, family branches that previously made efforts to conceal their ancestral identity are utilizing historical documentation, genealogical records, oral traditions and literature to provide new interpretations to their historical narratives, highlighting certain themes and playing down others, to emphasize their Muslim origin. This analysis sheds additional light on the changing roles of historical narratives in identity formation from the late imperial period until today.

此研究分析了從明初到20世紀之間的官方和家族歷史敘述,以及這些敘述在中國東南部地區穆斯林的身份形成中擔任的角色。敘述在此考查的與宋末元初的穆斯林官商蒲壽庚(約 1296 年)和元末穆斯林將軍金吉(1333 年被派往泉州)相關。兩人均在十三、十四世紀的福建地區扮演了重要的政治和軍事角色。這些家族的歷史敘述,緊密相連,也展現了其相互的沖突,利益和情感,極大地影響了整個泉州穆斯林的命運,尤其是對於那些仍居住在泉州及其周邊地區的蒲、金后裔。在當前政治環境下,獲得被官方承認的中國穆斯林身份(回族)成為穆斯林后裔尋根問祖的渴望。因此,以前努力隱藏其祖先身份的家族分支正在利用歷史文獻、族譜、文學記載和代代相傳的口述傳統為其歷史敘述提供新的闡釋,重點突出某些主題,弱化其他部分,以強調他們的穆斯林血統。此分析進一步闡明了從明清到今天,歷史敘事在身份形成中的角色變化。

Introduction

In 1277, Pu Shougeng 蒲壽庚 (d. ca. 1296), a wealthy merchant and official who enjoyed tremendous political, economic, and military power in Quanzhou, betrayed the faith of the Song (960–1279) imperial leaders by shifting his support to the advancing Mongol army. He shut the Quanzhou city gates and harbor, preventing the retreating Song troops from taking refuge in the city and denied them the anticipated support to continue resisting the Mongols. The service he rendered the new rulers proved highly beneficial. The Pu lineage ascended to its most powerful status ever, which it enjoyed throughout the Yuan period (1279–1368).

Almost a century later, in 1366, as the Yuan regime was declining, another local notable, a Muslim general named Jin Ji 金吉 (d.u.) who had been appointed to his post in Quanzhou in 1333, likewise switched allegiance at the gates. This time, he opened the city gates to the forces of a Chinese general in the service of the Yuan government, thus putting an end to the decade-long regime of a foreign-led Muslim militia whose notorious leader was related by marriage to the Pu lineage. For this meritorious deed, Jin Ji won the admiration of his descendants as well as other local literati commentators of the Ming period (1368–1644). By opening the gates, Jin Ji also symbolically determined the fate of the descendants of Pu Shougeng. Whereas until the 2000s, Pu family sources had almost completely ignored this event, for the Jin it constitutes the core theme of their genealogy and family history traditions.

This article examines oral and written traditions that reveal shifting attitudes of the Pu and Jin lineages of Muslim descent in Fujian and Guangdong toward the origin and identity of their celebrated Song, Yuan, and Ming ancestors. The Pu and Jin historical narratives are, at times, tightly linked, yet also present conflicting interests and sentiments. These narratives have been disseminated since the late fourteenth century by means of genealogical texts, literary works, oral legends, various references in ancestral worship, and symbolic imageries in the family shrines. They had tremendous influence on the lives and fortunes of Muslims in Quanzhou and their descendants who live to this day in Quanzhou and its surroundings.

This article is part of a larger project researching the history and current conditions of lineages of Muslim descent in Southeast China and Taiwan and the mechanisms they apply to shape their own identity. Members of these lineages are not practicing Muslims but are rather descendants of Muslim merchants and military men who settled in the city of Quanzhou on China’s southeastern coast during the Song and Yuan dynasties. Beginning in the fourteenth century, many of them intermarried with local residents and gradually assimilated into the local population. Today, however, many still preserve family traditions commemorating their ancestors’ distinct origin and the persecution that forced them to employ various strategies to disguise their identity. During the last four decades, under post-reform government policies regulating ethnic identification and privileges granted to minority groups, some have expressed this identity in ethnic terms and obtained official recognition as members of the Chinese-Muslim (Hui 回) minority. Although they are not Muslim, since 1979 the government has granted Hui status to a few lineage groups based on evidence they presented of maintaining ancestral worship customs with special characteristics like pork-avoidance and family-genealogies proving Muslim ancestry.Footnote1

Many of the Muslim descendants recognized as Hui have been very pleased with their new official status. Their satisfaction lies not only in the state’s recognition of their unique ancestral heritage, but also, and some claim chiefly, in the privileges granted to minorities in China. Until recently, as part of the Chinese government’s affirmative action policies toward minorities, members of the Hui were entitled to political, economic, and educational benefits.Footnote2 Such benefits obviously constitute an important incentive for accentuating the unique elements of their identity. Much of the research into Fujian Muslim descendants thus focuses on their origins, their affinity with Islam, and on the region’s Muslim heritage.Footnote3

Other works analyze markers of their Hui identity and their range of interpretation. In his seminal volume based on pioneering fieldwork carried out in the 1980s among Hui communities throughout China,Footnote4 Dru Gladney dedicated a chapter to the descendants of Muslims in Fujian, bringing their existence to the attention of western academic circles. He demonstrates how the Hui identity bears varying expression and significance for different communities and individuals. Within that framework, the Fujian communities constitute but one of many in the diverse mosaic of communities and individuals forming the Hui ethnic group. This mosaic includes Hui who are not practicing Muslims, enriching our understanding of Hui identity in general.Footnote5 Gladney’s work, together with the comprehensive ethnographies by Fan Ke in Fujian and Joël Thoraval in northern Hainan, have made important contributions to understanding the profound impact of the Chinese government’s changing policies on these lineages during the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote6 These government policies are currently being re-evaluated, and preferential rights have already been curtailed in several regions.Footnote7 This change may affect the public and scholarly discourse as well as the attitude of these communities towards their ethnic status, a subject for future investigation.Footnote8

The discourse on contemporary Hui identity in terms of the larger Hui collective and government parameters for determining ethnic status is important to this study but not at its center. The questions I pursue in this research focus on the ties of descendants of Muslims to the local society and their dynamic effect on identity formation. I employ methods of historical anthropology, exploring local, traditional cultural tools utilized by these descendants to mark their distinct origin. The narratives examined explain the circumstances and mechanisms that led to the localization and acculturation of these lineages. They tell the stories of groups whose identity is rooted in local society and manifested through traditional Chinese ritual and practice in which Muslim customs play only a symbolic role. To put it more simply, rather than focusing on what makes them Hui, the objective is to demonstrate what made them Chinese.

The currently accepted narrative, shared by descendants of Muslims and several scholars, highlights the Ming takeover as a turning point. Following the takeover, their Muslim ancestors, who were closely associated with the foreign Yuan regime, were persecuted, compelled to exit the central political stage, and dispersed throughout southeastern China.Footnote9 Today, the Pu and Jin orally transmitted historical narratives are sketched along similar lines, emphasizing their descent from foreign Muslims who gradually assimilated into local society. However, in the past, from the same historical incidents they developed separate narratives, revealing that the circumstances leading to the profound changes in the lives of the southeastern coast Muslims were far more complex than the currently prevalent explanation narrated along ethnically biased motives.

The analysis offered here highlights the changing roles of historical memories among descendants of Muslims as they continuously transformed over time and space, from the early Ming to the present. The study examines how these oral and written memories are revived, concealed or transformed and often partly constructed, thus reflecting the identity of these descendants of Muslims within a wider historical context, one that stretches back far earlier than contemporary government policies in the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C.).

The Pu Lineage

The Pu lineage of southeastern China are descendants of the famous Song and Yuan official Pu Shougeng, whose historical influence resonates in Southeast China to this day. Pu Shougeng was a wealthy merchant, widely believed to have been of either Arab or Persian origin,Footnote10 who held key positions in the international port city of Quanzhou (known in the West by its Arab or Persian name Zaitun). During the late Song and early Yuan, he became one of the most powerful political and military figures in the southeastern coastal provinces of China. Most researchers support the claim that Pu Shougeng’s ancestors were merchants who settled in Southeast Asia around the tenth century, moving to Guangzhou in the eleventh century. In the early thirteenth century, Pu Shougeng’s father, Pu Kaizong 蒲開宗 (d.u.), moved to Quanzhou. From that point forward, the family’s social and political position rose constantly.Footnote11

In 1274, after successfully repelling a pirate attack together with his brother Pu Shoucheng 蒲壽宬 (d.u.), Pu Shougeng was appointed Supervisor of Maritime Affairs and later granted additional military and administrative authority awarding him control over a substantial naval force. Shoucheng served as Prefect of Meizhou 梅州 (Guangdong) in 1271 and was appointed in 1275 to Jizhou 吉州 (Jiangxi), an appointment that he presumably declined.Footnote12 In addition to the local militia and the fleet at his command, Pu Shougeng enjoyed the support of several military officers who were stationed in the city, wealthy Chinese merchants, and the community of foreign merchants, whose influence was growing more powerful at that time.Footnote13

In early 1276, the Mongols invaded South China and occupied the capital Lin’an 臨安 (today’s Hangzhou). The Song loyalists gathered their forces at Fuzhou, where they enthroned the young prince Yi 益 and proclaimed him Emperor Duanzong 端宗 (r. 1276–1278). By the end of the year, the Mongol troops defeated them at Fuzhou and soon after, in early 1277, started their advance southwards toward Quanzhou. The Song forces were counting on the maritime power of Pu Shougeng and planned to retreat to Quanzhou and reorganize in order to stop the Mongol advance there.

To their dismay, Pu Shougeng shifted his allegiance to the Mongols, denying the Song loyalists entrance to Quanzhou and depriving them of the naval support upon which they were so desperately reliant. According to some sources, the primary reason for Pu Shougeng’s betrayal of the Song was his outrage at the confiscation of his entire fleet and property by the Song army leaders in service of their resistance to the Mongols.Footnote14 The Song army led by General Zhang Shijie 張世杰 (1236–1279) besieged the city, but Pu Shougeng endured for three months awaiting the Mongols’ arrival. In the meanwhile, he massacred thousands of Song imperial clansmen and loyalist members of the local elite, as well as a force of imperial troops that had been transferred to Quanzhou from the Huai River Valley the previous year. The Mongols occupied the city soon after.Footnote15 This marked the final stage of the Song struggle against the Mongols. Two years later, the Song were finally defeated in Guangdong where the last surviving crown prince, Duanzong’s younger brother, apparently drowned.Footnote16

Pu Shougeng was repaid generously by the new Yuan regime. Between 1279 and 1296 he was appointed to a series of key positions and enjoyed a flourishing career. Among the official posts that were conferred upon him were Grand Commander and Military Commissioner of Fujian and Guangdong Provinces and Customs Master of Quanzhou. In mid-1277, he was promoted to Vice-Governor of Jiangxi Province, and in 1278, he was further promoted to the position of Left Vice-Minister of Fujian Province. Some sources even claim that his military and political influence extended at that time over the entire southeastern Chinese coastline.Footnote17

The Yuan regime continued to put faith in his prestige as a leading figure in the local and foreign commercial arena. Soon after the surrender of Quanzhou, Emperor Kublai made special efforts to revive the foreign trade relations activity so crucial to the region’s economy. In 1278, he commanded Pu Shougeng and other officials in Fujian province to use their overseas connections to propagate the new regime’s interest in renewing trade connections, promising foreign traders freedom of movement and commerce throughout the country. Soon, several Southeast Asian countries re-established trade relations through South China ports.Footnote18 In 1280, Pu was ordered by the emperor to build 200 of the 600 warships that made up the fleet for the intended invasion of Japan.Footnote19

Pu Shougeng’s long career and widespread connections elevated the status of his entire family. Many members continued to hold key positions in the regional and national administrations in subsequent generations. Shougeng’s eldest son, Pu Shiwen 蒲師文 (d. 1292), was appointed as pacification commissioner, an army lieutenant-general, a customs commissioner for the Fujian coast, and assistant administrator of the Fujian Branch Secretariat. While serving as pacification commissioner for overseas foreigners, Pu Shiwen was ordered to maintain the flow of overseas trade.Footnote20 His other sons, Pu Shisi 蒲師斯 (d.u.) and Pu Yunwen 蒲允文 (d.u.), were also scholars and high-ranking officials.Footnote21 Throughout the Yuan period, several of the grandsons of Shougeng and Shoucheng were successful graduates of the imperial examinations and appointed to key positions.Footnote22

According to several Ming and Qing (1644–1912) sources, ninety years after the surrender of Quanzhou, Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 (r. 1368–1398) punished Pu Shougeng’s descendants due to the latter’s dominant role in the Mongol takeover. The Quannan zazhi 泉南雜志, compiled during the late Ming, quotes the earlier Song Yuan tongjian 宋元通鉴 by Xue Ying 薛應 (1500–1573): “Our great Emperor Taizu banned the descendants of Pu Shougeng […] of Quanzhou from serving in any official post as punishment for their forefather’s crime of supporting the Yuan takeover of the Song; therefore he fully persecuted them.”Footnote23 The late Ming Minshu 閩書 recounts: “Our Emperor Taizu forbade all Pu family members to attend the examinations and attain officialdom.”Footnote24

Based on such official historical sources, a tradition developed placing the brunt of responsibility for the Mongol takeover of Quanzhou and the consequent collapse of the Song resistance on Pu Shougeng, the official of foreign descent who orchestrated the surrender to the Mongols. Billy So demonstrates that Pu Shougeng would have been unable to withstand the local forces of Song loyalists without support from substantial sections of the local leadership.Footnote25 Nevertheless, the common sentiment attributing to him primary responsibility for the failure of the resistance bore far-reaching consequences for his descendants, causing their harsh fate in the early Ming. Most members of the Pu family were forced to emigrate from Quanzhou to remote rural areas where they adopted the local religions and customs; in some cases, they even had to conceal their identity.

Narratives of Forced Assimilation

Pu lineage members present various accounts of their ancestors’ strategies for concealing their identity or at least avoiding linkage to Pu Shougeng. Lineage members have been handing down these narratives of forced assimilation since the late fourteenth century through genealogical texts, oral legends, various references in ancestral worship, and couplets and inscriptions in the family shrines. Although by the mid-Ming the Pu had already not been practicing Muslims for a few centuries, like other southeastern lineages of Muslim descent, they maintained a secret tradition of abstaining from making pork offerings during ancestral rites – honoring their ancestors’ Muslim belief.Footnote26 Several Pu branches in Fujian, Jiangsu, and Hainan Island adopted a different surname in an attempt to avoid the discriminatory policies of the early Ming. Some resumed their original name in subsequent generations, whereas others retained their adopted names while secretly maintaining family traditions attesting to their ties with the Pu lineage.

The best-known case is that of the progenitor of the Pu branch in Dongshi 東石, south of Quanzhou. The Dongshi Pu, numbering several thousand, moved in the early Ming era to a section of the town formerly called Gurong Village (Gurong cun 古榕村). Until the mid-1950s, some of them still resided in the village. In its center was the family’s main ancestral hall. The hall and the burial grounds surrounding it were demolished in 1954, and the last remnants of the Pu neighborhood were completely erased in 1966.

The founder of the Dongshi Pu branch was Pu Benchu 蒲本初 (jinshi 1397), a great-grandson of Pu Shougeng. According to an 1870 edition of the genealogy compiled by the Yongchun 永春 Pu family branch (Pu shi zupu 蒲氏族譜),Footnote27 in order to avoid persecution and the harsh restrictions that the Ming founder imposed on Pu members, he was taken as an infant from Quanzhou to his mother’s hometown of Gurong Village, where he remained under the custody of her family and received their surname (Yang 楊). This enabled him, when older, to take the examinations and qualify as a student in the imperial academy. After he retired, he resumed his original name of Pu Benchu.Footnote28 An earlier Kangxi (1662–1722) edition of the Pu family genealogy provides details of his achievements:

He was among the successful candidates of the provincial imperial examination at the Quanzhou prefectural school in 1384Footnote29 and was ranked ninth among the successful jinshi candidates in the exam of 1397, and 25th in the second group (jia) in the final imperial examination. He was selected for the post of Hanlin Academy Junior Compiler (bianxiu). He retired at an old age and moved to […] [his hometown] Gurong.Footnote30

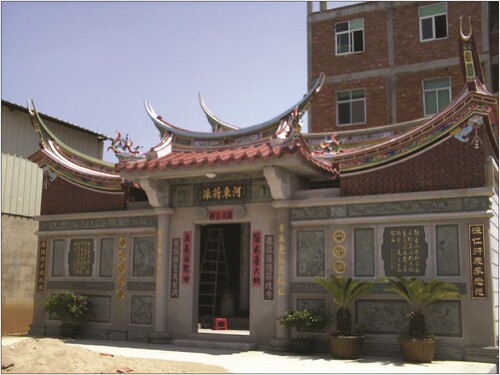

Persecution, and attempts to avoid it, are central themes in the Dongshi Pu family history, featured to this day in the symbolic imagery of their early ancestor. In 2009, a new ancestral hall (see ) was dedicated to the progenitor of the Dongshi branch and to the heritage of his settlement in the region. The walls of the hall are decorated with inscriptions and couplets commemorating the forced concealment of his true identity and the hospitality he received from his mother’s kin. An inscription on the entrance lintel reads: “The Yang [family] of [Gu] rong Village] disseminates virtue” (榕楊傳芳, see ). According to family sources, this verse was originally inscribed by Pu Benchu on the lintel of the family hall he built when he retired to Gurong Village.Footnote33 Another inscription explicitly refers to the help that the Yang family gave Pu Benchu: “As for maternal uncles, we cherish with greatest affection [Yang] Yiweng [Pu Benchu’s uncle]” (渭陽最思頤翁情).

Figure 1: A newly built ancestral hall dedicated to Pu Benchu 蒲本初, the progenitor of the Dongshi Pu branch. Photo by the author.

Figure 2: An inscription on the entrance lintel of the Pu family hall reads: “The Yang [family] of [Gu] rong Village] disseminates virtue” (榕楊傳芳). Photo by the author.

![Figure 2: An inscription on the entrance lintel of the Pu family hall reads: “The Yang [family] of [Gu] rong Village] disseminates virtue” (榕楊傳芳). Photo by the author.](/cms/asset/7689643c-c82d-471d-aa2d-d1a06ac37f55/ymon_a_2335815_f0002_oc.jpg)

There are other cases of name change among the Pu lineage. Beginning in the 1930s, researchers reported encounters with branches of the family that had chosen to change their name from Pu to Wu 吳 in order to hide their true identity. Some were told that the choice of Wu was due to its resemblance to the sound of Pu in the Minnan (southern Fujian) dialect.Footnote34 Contemporary researchers report similar cases among descendants of Pu Shougeng in Nanjing and among sub-branches that migrated to Qinghai and Gansu.Footnote35 The Pu lineage members present the adoption into their forefather’s maternal line, the name change, and the subsequent return to the original name as outcomes of the challenges their ancestors faced during the early Ming period. However, as demonstrated by Michael Szonyi, the customs of uxorilocal marriage, cross-surname adoption, and the “return to the original surname” (fuxing 复姓) in the late imperial period were widely practiced customs in some parts of Fujian.Footnote36

Such mechanisms were employed by the Dongshi Pu for different reasons in later periods. During the Republican era (1912–1949), lack of government law enforcement contributed to incursions and harassment of small families by larger families. To escape harassment, many Pu households chose to adopt their mother’s surname. Thus, to this day, there are many within the Cai 蔡 and Wu 吳 families in the vicinity of Dongshi who were originally Pu and who still maintain close relations with their Pu relatives.Footnote37

Excluding Shougeng from the Genealogy

Another family practice that the Pu attribute to their special historical circumstances is the removal of traces of Pu Shougeng from their genealogies. In the late 1930s, Zhang Yuguang 張玉光 and Jin Debao 金德寳 discovered in the town of Dehua 德化, north of Quanzhou, the Pu shi zupu 蒲氏族譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Lineage) belonging to one of Pu Shougeng’s lineage branches. This genealogy includes relatively detailed biographies of the Pu ancestors. Pu Shougeng’s father appears in the sixth generation and his brother Pu Shoucheng is listed as the seventh-generation ancestor. Surprisingly, there is no entry dedicated to Pu Shougeng. The only mention of the name Shougeng is in his father’s biography in the list of his three sons. Zhang Yuguang and Jin Debao, who were permitted to copy parts of the genealogy, commented that in the section dedicated to the seventh generation there was a blank space of one page and not even one word written about Shougeng.Footnote38 That copy was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). However, in 1982, Liu Zhicheng discovered another copy in Yongchun, which had been handwritten between 1875 and 1908. It also lacks mention of Pu Shougeng while documenting his direct descendants.Footnote39

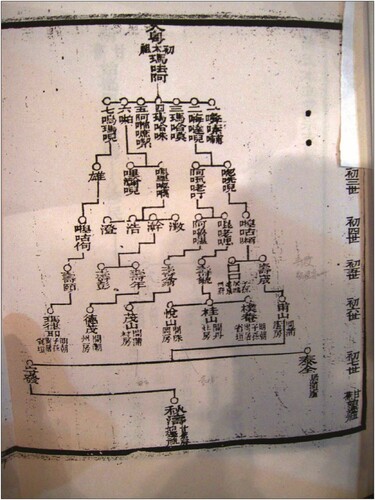

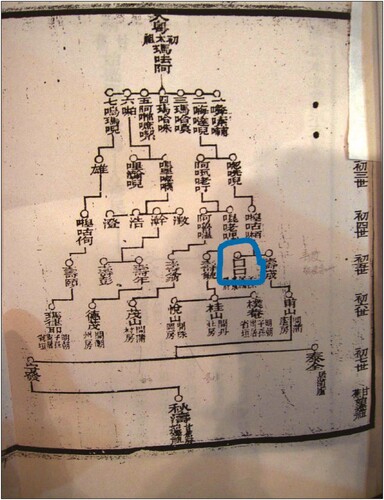

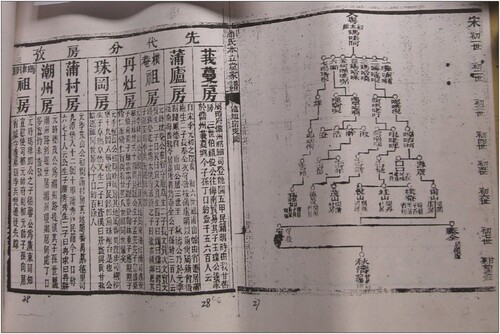

A similar measure was employed in other Pu genealogies. In recent decades, a copy of a genealogical pedigree chart originating in Guangdong that was reproduced from the 1619 Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu 南海甘蕉蒲氏家譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Family of Ganjiao, Nanhai)Footnote40 has been circulating among Pu branches in Fujian, drawing considerable attention from family members. Copies of this genealogy have also been disseminated among Pu lineages throughout the southeastern coast of China, stirring the emergence of different, often conflicting, Pu family narratives. I was first introduced to this chart during a visit to Dongshi in 2005. It records the first eight generations of the Pu family in China. It includes Shougeng’s brother, Pu Shoucheng. Next to him, where Shougeng should be listed, are two blank squares representing an anonymous ancestor. A later handwritten addition, next to the empty squares, states that the anonymous forefather’s descendants immigrated to Fujian and settled in Quanzhou, but there is no indication of the circumstances and period of this addition. Current family members in Guangdong and Fujian were unable to provide any other details.

The omission of Shougeng is quite odd since his renowned brother and his descendants are mentioned in great detail in the genealogy, up to the nineteenth century. Based on the compiler’s explanation in the section entitled “Jiapu fanli” 家譜凡例 (Common Guidelines for the Genealogy, see – and ), I believe it was not a measure taken for effective disguise, but rather for avoiding extra attention to this undesired link:

Throughout history, [we have kept] the following rule in our genealogy: if a lineage member was an evil official who was executed as a punishment he well deserved, for crimes such as conspiracy and treason, or was expelled from his home for being unfilial, or was killed while committing robbery or rape and so on – without any exception, his name should be erased and not recorded. Instead, there should be two empty squares such as this □□, to make known he is held in contempt by the lineage. This is a rule of our illustrious family’s genealogy throughout successive generations.Footnote41

Figure 3: A genealogical pedigree chart in the 1619 Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu 南海甘蕉蒲氏家譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Family of Ganjiao, Nanhai). Photo by the author.

Figure 3a: Where Pu Shougeng should be listed, there are two blank squares representing an anonymous ancestor. Photo by the author.

Figure 4: Copies of the genealogical chart originating in Guangdong have been disseminated among Pu lineages throughout the southeastern coast of China. Photo by the author.

During research trips in Guangdong in 2013 and 2016, in search of the descendants of this genealogy’s compilers, I investigated how these family branches perceive the tradition of disguising their family ties with Pu Shougeng. All personal communications to date indicate that the branch members are largely unfamiliar with Pu Shougeng and their family ties to him or to Muslims at all. Perhaps this indicates the effectiveness of the “empty square” strategy in actually concealing their ancestor’s identity. Lacking additional information this remains mere speculation.Footnote43

Nevertheless, the Guangdong Pu family does preserve an interesting tradition of foreign descent. A family hall I visited in Zhujiang 珠江 Village, Guangzhou, belongs to a branch that presumably shares a great-grandfather with Pu Shougeng. The hall was restored in 1997. In place of the original, individual soul tablets that were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, there is a tablet inscribed with the genealogical chart of their branch. Many families in the vicinity have such tablets but the Pu point to the very peculiar names of their early ancestors: the first two are Maqu’a, the lineage founder, and his second son Haida’er, mentioned above. Haida’er’s son is Hewalaoding 呵咓咾叮 (Awan aldin?). This tablet, together with the mentioning of Pu Shoucheng and the taboo on the name of his brother, are seen by some researchers and Fujian Pu members as clear evidence that the two lineages share the same origin of West Asian Muslims who arrived as merchants from Southeast Asia and settled in Guangzhou during the early Song.

However, according to the Guangdong genealogy, their family is of Uighur, rather than Arab or Persian, origin. This claim appears in an essay titled “Puxing yuanliu kao” 蒲姓源流考 (A Study of the Origin and Development of the Pu Family):

Our early ancestor of the Song era admired the Confucian teachings and therefore came from the Western Regions to China. Our third-generation forefather’s younger brother qualified as a jinshi in the Mongol-Semu list during the Taiding era (1324–1327), [in the year] 1327. […] In the old genealogy [our ancestors] were referred to as Huihe from the Western Regions (西域回紇人). Investigating this matter shows that the Western Regions are in fact Mongol territory. During Tang [618–907] and Song times they were called Huihe 回紇 as well as Huihu 回鶻.Footnote44

During the early 1980s, 700 km down the coast in northern Hainan, the same genealogy had a tremendous effect on another Pu lineage group, an offshoot of the main lineage in Guangdong. During the first half of the fifteenth century, their ancestor Pu Yuye 蒲玉業, a descendant of Pu Shoucheng, joined his father in search of trade opportunities on the northwestern coast of the island. Shortly thereafter, Yuye and his family moved to their current location in Dan County (Danxian 儋縣), Hainan, where he founded the lineage center. By the Wanli period (1572–1620), the Danxian Pu had lost all trace of their Muslim faith and all contact with their kinsfolk in Guangdong. Until the 1980s, the common wisdom among the lineage members held that they were, like many among the Hainanese, Han who originated from Fujian, presumably from the Putian 莆田 district.Footnote45

In 1982, a family member working in Guangdong was introduced to the Ganjiao (Guangdong) Pu genealogy containing a brief passage describing the founders of the Danxian lineage branch and their origin in Guangdong. Back home in Hainan, he shared the exciting discovery with family members. Unlike the Guangdong branch, the Danxian Pu took a keen interest in their newly discovered Muslim heritage. Motivated by the prospects of the new ethnic policies, they embarked on a decade-long effort to obtain Hui status. The process involved a failed attempt to revive their Muslim religious identity by forging links with the Hainan Hui, also called Utsuls. The Hainan Hui are a Chamic-speaking Muslim group originating in Champa (present-day Vietnam) and now residing in Yanglan 羊欄, southern Hainan, of whom many are surnamed Pu.Footnote46 The evidence of their shared Muslim origin was sufficient foundation to tighten relations between the communities, with the Yanglan Pu undertaking a mission to revive Islamic practice among the Danxian Pu. Although this joint endeavor was later abandoned, the Danxian Pu unique family heritage remains vibrant. Unlike the main lineage in Guangdong, they have embraced their Muslim origin and genealogical links to the Pu brothers. The Danxian lineage produced a new edition of the Ganjiao genealogy containing a historical introduction that highlights their descent from the renowned Muslim lineage of Pu Shoucheng. This edition has been widely distributed among their Guangdong kinsmen as well as major offshoots in other southern provinces of China.Footnote47

Other Muslim Memories of the Yuan–Ming Transition

Let us return to Pu Shougeng’s more direct descendants in Fujian. Only recently have researchers encountered solid evidence demonstrating that, in fact, the Pu family’s close ties with the Yuan regime had already been dramatically severed in the late Yuan era in a process that climaxed in a violent struggle known as the Ispah Rebellion (Yisibaxi bingluan 亦思巴奚兵亂, 1357–1366).Footnote48 The struggle was waged between the Muslim militia – headed by a Pu in-law – and the Yuan regime backed by local Chinese warlords. It marked the final undermining of the Pu family status, two years prior to the Ming takeover.

A detailed account compiled in 1555 of this less familiar narrative can be found in the Qingyuan Jin shi zupu 清源金氏族譜, a genealogy of the Jin, whose founding ancestor Jin Ji was discussed earlier. This event is referred to in several essays throughout the genealogy. The most detailed essay is included as an appendix to the genealogy titled Li shi 麗史 (The Glorious History). It is a fascinating historical source that has been largely overlooked by scholars. Most Chinese commentators describe it as a romantic historical novel set against the background of events at the end of the Yuan dynasty in Fujian. Its last section recounts the quelling of the Ispah Rebellion by local Chinese forces loyal to the Yuan regime, with the collaboration of General Jin Ji, who served as a Muslim militia commander.Footnote49

The account of the final days of the Ispah Rebellion in the Li shi is preceded by passages of background information regarding the foreign leadership of the city. This description includes an extremely unflattering account of Pu Shougeng and his brother during the last days of the Song, where they are portrayed as deceitful schemers:

Formerly, numerous foreigners of the Western Regions (Xiyuren) resided in Quanzhou. During Song times there were Pu Shougeng and [Pu Shoucheng], who received official titles thanks to their suppressing of pirates. Shougeng was Pacification Commissioner (zhaofushi) and Superintendent of the Customs (shibo) affairs. Shoucheng was [appointed an office] in Jizhou [in present day Jiangxi], but since he knew that the days of Song were numbered he did not take up his position. In 1276, Yiwang [Emperor Duanzong], on an imperial tour to the south, stopped over in Quanzhou harbor. Zhang Shijie [a Song general who headed the resistance to the Mongols in the last years of the DynastyFootnote50], raised an army of 3,500 people from among the Huai region people and left them for Shougeng’s use. The military men were fierce and intrepid but not good strategists. Shoucheng on the other hand had a plan worked out. When Yiwang’s force was approaching the city, he instructed Shougeng to shut the gates and refuse to let them in. They killed all the Song royal clansmen in Quanzhou, numbering over thirty people, and left nothing of the entire Huai River army. Together with the Vice-Prefect (Zhou sima), Tian Zhenzi, he went to Hangzhou to surrender to Suodu [the Supreme Commander of the Mongol army in that campaign].Footnote51 Zhang Shijie returned to re-take [Quanzhou], but he attacked for ninety days to no avail.

Once the execution of Shoucheng’s plan was agreed upon, he set out dressed in rustic clothes and retired [from his posts] to the seclusion of Faming Temple. One day while he was taking a nap, there appeared two scholars who said they had come from Chaozhou (in Guangdong). The two poems they left behind, titled “Calling on the Reclusive Scholar,” read as follows:Footnote52

Plum blossoms fell and scattered over the moss;

Heaven seems to wish [the Song] to take refuge by going out to sea.Footnote53

Butterflies did not realize that spring had gone,

And still came darting in pairs over the whitewashed walls.

Swords and spears were assembled in number for the support of the emperor.

While solitude reigned in the hills and woods and the door was shut,

The sound of water and the chirping of birds both proclaimed current affairs.

Do not say that the old man of the mountains is completely unaware.Footnote54

When Shoucheng woke up, the gatekeeper submitted [the poems] to him. Shoucheng lost his presence of mind and was covered with sweat from fear. He urgently dispatched people all over the country but they were nowhere to be found.

When the Yuan ruled over China, due to his meritorious service they conferred upon Shougeng an official post serving [as the governor] of [the newly established] Pinghai Province (Pinghai sheng) at Quanzhou. Shoucheng also occupied a high government position, and in that period their descendants were the most highly placed and eminent officials in the country. The people of Quanzhou were subject to their influence for ninety years. Then the Yuan government declined, armed rebellions started everywhere and the state’s orders could not be carried out.Footnote55

The description of the Pu brothers in the Li shi is merely an introduction to a detailed account of the end of the Ispah Rebellion, featuring another historical figure: a foreign Muslim of Persian or Arab origin (Xiyuren) named Nawuna 那兀納, also called Awuna 阿巫那 or Nangna 那嗯呐 (d. 1366). Nawuna was a notorious militia leader who took command of the Persian garrison that ruled Quanzhou during the second phase of the rebellion between 1362 and 1366. His short-lived tyrannical regime caused immense suffering to the city’s population and severely damaged its economy.Footnote58 In the novel, Nawuna is presented as an in-law of Pu Shougeng’s family.Footnote59

His [Pu Shougeng’s] in-law, a man of the Western Regions [called] Nawuna, staged a sudden armed rebellion […]. Nawuna had already seized control of the city. He committed excessive pillage and rape. He selected women from among the people to serve in his residence as his concubines. He […] built there the temple Fanfo si.Footnote60 He then embellished the temple to the extreme, storing in it treasures that he had stolen from elsewhere. […] In 1354,Footnote61 he dispatched cavalry to attack Xinghua.Footnote62

“The rebels are in fact only Na and Pu, while all the people are forced to join them against their will. During war surely they will be sent to the frontlines. What use will there be in the government forces killing them?” […] Inside the city, the Commander of the Thousand Households (qianhu) Jin Ji, also of Muslim (Huihui) origin, was guarding the city’s western gate. Yi Su saw him and said: “The military man who would put the Muslim [rebels’ leader] to death will be regarded in great esteem. You, illustrious lord, in your capacity as the garrison’s commander, can kill Nawuna and then receive the government troops and that will be to your tremendous merit. However, if you wait until the government troops enter [without your help], and only then greet them, I must humbly convey my fear that in the midst of fighting, it will be difficult to distinguish who is on which side, and you, my lord, may find yourself in a very difficult situation.” Jin Ji was startled. He made an agreement with Yi Su, and at night he opened the western gate and secretly allowed Chen Xian’s troops to enter the city. Nawuna charged out of the city with his cavalry to counterblock their advance. Yale, holding a large hatchet, courageously charged right into the [enemy’s] battle lines, beheaded over a hundred cavalrymen, seized Nawuna and took him to the capital.Footnote63

The Fuzhou army arrived, tore open all the Pu traitors’ graves and confiscated the huge amount of treasure [buried in them]. Most lavish was the tomb of Shougeng’s ruthless elder son, Shiwen, who had executed the Song imperial clansmen with his own hands. [It contained an] epitaph inscription made of emerald, composed by Chengshou, a Hanlin academician from Jinling (Nanjing).Footnote64

All of the Western people were annihilated, with a number of foreigners with large noses mistakenly killed, while for three days the gates were closed and the executions were carried out. […] The corpses of the Pu were all stripped naked, their faces to the west. […] They were all judged according to the “five mutilating punishments” and then executed with their carcasses thrown into pig troughs. This was in revenge for their murder and rebellion in the Song.Footnote65

Pu and Jin as Friends and as Foes

The Pu genealogy makes no mention of events and figures related to the Ispah Rebellion; however, it does refer to the Jin ancestors in a completely different context. The Fujian genealogies include a biography of Pu Rihe 蒲日和 (d.u.), Pu Shougeng’s nephew, the second son of Pu Shoucheng. The earliest version of his biography appears in the Yongchun Pu genealogy compiled between 1662 and 1722.

Rihe, style Guifu, is the second son of Pu Shoucheng. He is a Muslim believer, prudent in his speech and cautious in his actions. He regularly attends daily prayers. During the Zhizheng reign period (1341–1370) of the Yuan dynasty, the mosque was damaged with no means of repair. Together with Jin Ali from his hometown, they attended to this matter and restored the building. Throughout they used big slabs of stone for the construction, and the outcome was most magnificent. An inscription, with his name, on a tablet to the right of the building’s entrance, exists till this day.Footnote66

Whereas the Pu genealogy omits details of Pu Shougeng, it highlights a presumed link to a prominent Muslim who took part in a prestigious public religious project. One contemporary Pu family writer even maintains that Pu Rihe and Jin Ali were cousins, claiming that Rihe’s father (Pu Shoucheng) was married to Jin Ali’s aunt.Footnote69 The Pu genealogy compilers may have had a clear motive in asserting this cooperation between Rihe and Ali. Nevertheless, the claim cannot be discarded unequivocally. Perhaps Rihe’s Kangxi-period biography was based on an earlier version that was originally compiled before the 1507 copy of the inscription was made. If so, it is possible that at that time the inscription was publicly displayed and did include Rihe.Footnote70

In the last passage of the new inscription, the writer added: “Owing to the fact that the inscription on the original tablet is worn out by the ravages of time, Xia Yangao […] had its full text transcribed from the Annals of Quanzhou and raised funds to erect a new stele.”Footnote71 The possibility that in the transcription process the name of Pu Rihe was omitted can thus not be dismissed entirely. Furthermore, as John Chaffee points out, the tablet upon which Rihe’s name was reportedly inscribed, together with Jin Ali, was most likely not the mosque’s restoration stele (bei 碑) but rather a separate horizontal tablet (bian’e 匾額). Therefore, a plausible explanation for the absence of Rihe’s name is that it was inscribed not on a stele but rather on a separate tablet. After all, it is unlikely that the Ming genealogist would have claimed that Rihe’s name was there to be seen, had it not been the case at the time he was writing.Footnote72 It is impossible to verify any of these opposing versions. Nevertheless, for the Pu, the appearance of their ancestor in the context of such a public official undertaking must have constituted an important source of legitimization.

Pious Philanthropist or Notorious Plunderer? Jin Ali in Official and Family Histories

In order to shed more light on this issue, I return to examine the Qingyuan Jinshi zupu (Jin Lineage genealogy) for references to Jin Ali and his role in the mosque restoration. These appear in a number of essays, honorary introductions, eulogies, and biographies, including the complete text of the 1349 renewed mosque inscription discussed above. Jin Ali is identified with Jin Heli 金呵哩 (rather than the original inscription’s Ali 阿里), who is recorded in the genealogy as the second generation of the Quanzhou Jin lineage of Muslim descent, the son of the lineage progenitor Jin Ji. The following reference appears in the biography of Jin Heli:

Our lord’s usual conduct was oblivious to material gains, charitable and generous, merciful and benevolent. He revered Islam and Muslims. In Quanzhou there was [a mosque called] Qingjing. It has long fallen into disrepair. The master used wood and stone to renovate it, spending a large amount of money. The building was grand and spacious; its splendor can be witnessed to this day. Muslims are most appreciative of him and repeatedly carved steles to commemorate his merit.Footnote73

Thus far, I have analyzed Jin lineage sources that provide different perspectives on events related to the Pu family. But in fact, the Jin genealogy uses similar editorial manipulations to those employed by the Pu genealogy compilers for its own purposes. While the genealogy celebrates Jin Heli’s pious deeds, local gazetteers present a different view of his character and role in historical events of the region. According to these official accounts, prior to his father’s surrender of the town to government forces in 1366, Ali (Heli) had been a chief military officer of the rebel leader Nawuna. He was embroiled in the war atrocities of that period, responsible for executing local opponent leaders, massacring civilians, and plundering and destroying villages.Footnote74 In 1366, General Chen Youding 陳友定 (d. 1368)Footnote75 was dispatched south to put down the rebellion. His forces met the Ispah warriors at Xinghua. Jin Ali was captured and executed along with the other rebel leaders. The rest of their force was completely annihilated. Due to their mass killings and cruelty toward the local inhabitants, the Ispah rebels were extremely unpopular: “Zong Hai [Chen Youding’s son] pressed hard upon them, captured Bopai, Ma Hemou, Jin Ali and others, and killed them. The remainder of the force was scattered. Peasants, who lived in nearby villages, also murdered the defeated with their spades and hoes.”Footnote76

The reputation and fate of Jin Ali in these accounts is portrayed entirely differently than in Jin family sources. In fact, the account of his last confrontation with government forces is highly reminiscent of the passages in the Jin genealogy recounting the final routing of the Pu. The battle at Xinghua marked the collapse of the Ispah force. Chen Youding wasted no time in turning his forces to Quanzhou for the final confrontation with Nawuna. It was there that Jin Ji, a month after his son’s death, opened the city gates granting entry to the government forces. In light of the official accounts of the events preceding the siege on Quanzhou, Jin Ji’s historical role in determining the fate of his descendants emerges as far more crucial. Ultimately, it was his action at the city gates that dictated a different memory and fate of the Jin, distinguishing them from the Pu lineage in the generations to come.

Modern Narrative Formation and Ethnic Identification

The 1555 Jin family history preserved historical accounts that had been deliberately omitted from the Pu collective memory for over six hundred years. Today, under the current ethnic policies in China, members of the Pu family are retrieving these memories to portray their history in terms of the forced assimilation and persecution inflicted on their ancestors during the Ming, due to what they claim were ethnic motives and biases. It is difficult to ascertain exactly when and how Pu family members, as well as commentators, adopted this now prevalent narrative of persecution. However, a glimpse into a rare record of Pu lineage descendants in the late Republican period reveals the way in which this narrative may have been introduced and transformed during the last century.

In December 1939, Zhang Yuguang and Jin Debao, two young Muslim clergymen (ahong 阿訇) and activists of the Chinese Muslim Association for Saving the Nation (Zhongguo Huijiao jiuguo xiehui 中國回教救國協會)Footnote77 conducted a survey among the Pu lineage members in the town of Dehua. The organization was founded during the Japanese invasion in the late 1930s and aimed to mobilize the Hui to contribute to the Nationalist cause and promote the Muslim Chinese role in building and strengthening the Chinese nation. The two representatives were the first outsiders given the opportunity to view the Pu lineage’s seventeenth-century genealogy. They recorded an interview with Pu Zhenzong 蒲振宗 (b. ca. 1908), a family member who possessed the genealogy. The writers describe how their interviewee knew only scant fragments of his family history. This unique record documents what might be the earliest instance of introducing the Pu to their own family narrative, designed according to modern notions of ethnic Hui identity.

The visitors, apparently well informed of updated scholarly works on Pu Shougeng, presented the interviewee with the details of his ancestor’s high political position in the Song and Yuan:

In the past, the Pu were a prominent Muslim family who had made important contributions to the country. At present there are many scholars worldwide, who concentrate their efforts in researching Pu Shougeng’s deeds. We believe Pu Shougeng is among the most honorable Muslim people, and we respect and admire him. We have no doubt that you must surely be very proud of the glory and great meritorious exploits of your esteemed ancestor. However, I fail to understand: your honorable ancestor was originally a Muslim. Your abandoning of Islam is the equivalent of giving up your ancestor’s glory. You should return to your ancestors’ religion and thus make known your ancestor’s past meritorious service and so add to the prestige of both the Pu family as well as Islam.Footnote78

That is correct; you were not suppressed due to misdeeds committed by your forefathers. Persecution of that kind frequently occurred during imperial times. Ming Taizu gained his political power through a popular uprising. In order to secure his position, he naturally suppressed any family who had previously held military power and made them submit to him. At that time not only you[r family] suffered persecution, but also the Sun and Liu families met the same fate. Ming Taizu issued edicts banning the descendants of Pu Shougeng, Liu Mengyan, Sun Shengfu, Huang Wanshi and others from entering officialdom. These matters can all be found in historical accounts.Footnote80 In the past, due to political reasons, you were compelled to renounce your religion. Now that you are already aware of this state of affairs – for the sake of your ancestors, for the sake of your glorious history, for the sake of obtaining your right belief, for the sake of saving the nationFootnote81 – we hope that you, with your entire clan, will all return to your ancestral religion.Footnote82

Evidently, at the turn of the twenty-first century, encouraged by government policies regarding Hui identity and aided by contemporary historical research, the Pu no longer find it necessary or beneficial to conceal their origin. At a distance of several centuries and in an era when proof of foreign descent is highly desirable, the Pu have no problem admitting that they not only originate from the Muslim Chinese official Pu Shougeng, but also have family ties with a foreign despot such as Nawuna. The new Yongchun genealogy has been copied and transmitted to the Dehua offshoot and is thus instrumental in disseminating new themes into the family history.

Meanwhile, in early 2000s’ Dongshi, where over 600 hundred years ago little Pu Benchu changed his name to Yang Benchu, his descendants appealed to local authorities to reacquire a small portion of land and rebuild their ancient ancestral hall dedicated to Pu Benchu, which had been destroyed in the 1950s. They stated that this hall would serve not only for family rituals but also as a national historical site. During a visit to Dongshi in 2002, family members showed me a detailed architectural plan for a grand memorial hall. Interestingly, along with the traditional Chinese features, the plan also contains arched windows designed in what they perceive as ancient Middle Eastern or Muslim architectural style.Footnote84 The government did not approve their appeal,Footnote85 but in 2006, authorized the building of a small pavilion with a “Gurong Pu History Stele” (Gurong Pu shi bei 古榕蒲史碑) erected at its center. The stele contains a brief family history beginning with the early Song-dynasty Muslim ancestors of West Asian origin, continuing with Pu Shougeng, to his great-grandson who established the sub-branch in Dongshi and down to the present.

The Gurong Pavilion and the newly built ancestral hall mentioned earlier represent two different facets of the current Dongshi Pu identity: the official public approach aligned with present-day ethnic discourse and resurgence of Hui heritage, and the more private traditional approach of centuries-old ideology and terminology of lineage discourse. The stele in the pavilion highlights the family’s foreign origin, emphasizing Pu Shougeng, and is decorated with a heading “The Gurong Pu History Stele” in Chinese and Arabic. This aspect of the family heritage has recently become very important, and the Pu are extremely keen on publicly promoting it. The family hall represents the other, complementary aspect of the family narrative, celebrating the more private, Ming-era Sinicized ancestors’ achievements and emphasizing the high esteem in which the Yang family, responsible for those achievements, is held.

Conclusion

Thoraval summarizes his analysis of the failed attempt of the Danxian Hainan Pu during the 1980s to convert to Islam under the guidance of the Utsul Muslims of southern Hainan as a conflict between a “lineage religion” of traditional Chinese kinship practices and an “ethnic religion,” referring to their newly adopted Islamic identity. Reviving “ethnic religion” among them was met by resistance on the part of both authorities and lineage members and was eventually abandoned.Footnote86

Examining communities of descendants of Muslims in Southeast China a generation later, it appears that what Thoraval termed “lineage religion” has triumphed, remaining the most substantial model for identity construction. Three decades after Thoraval published his work, the atmosphere and circumstances prevailing in Hainan and nationwide leave scant prospects for the re-emergence of “ethnic religion.” Until several years ago, officials supported the Utsuls’ Islamic identity and ties with Muslim countries. But since 2018, the Utsuls and other groups have been targeted by the Chinese Communist Party’s campaign against foreign influence and religions. The campaign severely limits expressions of faith and links to the Arab world in its drive for a unified Chinese culture with the Han ethnic majority at its core.Footnote87

The historical and ethnographic sources examined here focus on ancestral narratives of the lineages in question and their crucial role in identity formation. This work demonstrates that although the lineages’ current identity has roots in the memory of their Song-Yuan Muslim origins, the essential component of their identity over the past six centuries has been constructed from memories of their more familiar sinicized ancestors who established localized lineages during the Ming. Throughout history, the descendants of Muslims have selectively chosen to highlight certain themes in their history while ignoring others. Genealogical evidence that was kept hidden by the Pu over many generations is now celebrated as important identity markers. The approach toward their own family history reveals the dynamic nature of these “living texts” that play different roles under changing circumstances. The Pu and Jin narratives are continuously evolving as previously unknown chapters in their history unfold. In line with Maurice Halbwachs’ On Collective Memory (1950), this work demonstrates how historical heritage constructs the current identity of the descendants of Muslims in Southeast China, whereas it is contemporary social and political conditions that shape the historical narratives themselves.

The theme that appears central to all family historical narratives of the lineages discussed here are the traditions related to their assimilation into Chinese society. Most works adopt the approach of the current descendants of Muslims and tend to analyze these communities and the traditions related to them in ethnic terms, referring directly to P.R.C. policies of ethnic identification. In fact, narratives of forced assimilation appear to be central to contemporary identity formation of Muslim descendants in Southeast China. Thus, families of Muslim descent share the same popular explanation for their unique status of being Hui or for their application for Hui status, even though they are not Muslim. This was also the case among the Hainan Pu. In December 1983, representatives of the Pu lineage in northern Hainan petitioned the Provincial Nationalities Commission to change their national status. They concluded their appeal stating that they had forfeited their identity only under threat of discrimination by the majority Han. But they maintained “tacit awareness” of being “descendants of former foreigners, that is to say, the Hui.”Footnote88 Dru Gladney addresses the traditions of forced assimilation among descendants of Muslims in Fujian, stating that the “common experience of suffering and forced assimilation may have been what galvanized the Hui ethnic consciousness into a single minority.”Footnote89

However, an explanation outlined primarily in terms of revealing or reviving an authentic ethnic identity is insufficient for understanding the current narratives of Muslim descendants in Southeast China. Firstly, this approach is inadequate from a historical perspective. It tends to employ a rather simplistic, ethnicity-based explanation characterized by a monolithic perception of the dynastic cycle, portraying the interests of Mongol rulers and Muslim settlers such as the Pu family as one, against those of the Han Chinese identified with the Song and later with the Ming dynasties. While Fujian Muslim descendants in general, and the Pu in particular, portray their ancestors’ treatment as ethnically biased, sources such as those analyzed above indicate that, in fact, the approaches of both Yuan and Ming toward non-Chinese were far more composite and were based on local rivalries that were not necessarily related to an ethnic identity or foreign origin. This research demonstrates that the ethnic tones currently highlighted in certain family narratives are largely products of contemporary political and scholarly discourse. A different perspective is gained by the study of the Fujian and Guangdong Pu lineage branches analyzed above that are interested in nurturing their ancestral legacy while remaining Han.

It is rather symbolic that both the local Muslim leaders and celebrated ancestors of the Yuan era influenced their descendants’ fate for many future generations by either opening or shutting the city gates in response to an advancing Chinese army. Pu Shougeng prevented the Song emperor from entering the city and brought about the dynasty’s final defeat. Toward the end of the Yuan period, his family’s in-law, Nawuna, did the same with the advancing provincial army headed by the Han general Chen Youding, though he was defeated shortly thereafter. Jin Ji is revered by his descendants for nobly opening the city gates, enabling the provincial army to seize the city and freeing its inhabitants from the Muslim rebels.

Throughout history, lineage members have reached back to revisit memories of the dramatic events at the gates of Quanzhou and the tremendous transformation brought about by the Ming takeover. These memories have been continuously remodeled or revived to reflect the changing identities and status of descendants of Muslims from the late fourteenth century to the present. Current shifts in the government's approach to ethnicity will likely continue to affect the role of these narratives in the years to come. As Le Goff stated, “Memory, on which history draws and which it nourishes in return, seeks to save the past in order to serve the present and the future.”Footnote90

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oded Abt

Oded Abt (Ou Kede 歐克德) is a researcher and lecturer of Chinese social and religious history at Tel-Hai Academic College. In 2012, he completed his Ph.D. in the School of Historical Studies at Tel Aviv University. His research focuses on historical anthropology, and ethnic and religious heritage of descendants of Muslims in China and overseas. Between 2013 and 2016 he carried out fieldwork and research in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Manila as a post-doctoral fellow and a research fellow of the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (2013–2015), the Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, Hebrew University (2014–2016), the Area of Excellence Scheme: The Historical Anthropology of Chinese Society, Centre for Historical Anthropology in the Chinese University of Hong Kong (2016), and the Gerda Henkel Foundation Research Scholarship (2016). After returning from Hong Kong in 2016, he joined the faculty of the Department of East Asian Studies at Tel-Hai College and the Tel-Hai Center for the Study of Religions. Among his recent publications is Islam and Chinese Society: Genealogies, Lineage and Local Communities (Routledge 2020), co-edited with Ma Jianxiong and Yao Jide.

Notes

1 In the Quanzhou area there are a few communities of Muslim descendants that throughout the years have maintained some form of Muslim worship. Therefore, as early as the mid-1950s, those groups were officially recognized as Hui. See CitationGuo Zhichao 1990; CitationAbt 2014.

2 CitationGladney 1995, pp. 254–266.

3 CitationChen Guoqiang 1990; CitationChen – Chen 1993; CitationGuo Zhichao 1990; CitationQuanzhou Foreign Maritime Museum 1983; CitationZhuang Jinhui 1993.

7 This revised approach was recently voiced by President Xi Jinping in his speech at a gathering to honor national role models for ethnic unity and progress in Beijing on September 27, 2019 (CitationLi Xueren 2019).

9 Similar narratives of forced assimilation among the Fujian Guo lineage are explored in CitationGuo Zhichao 1990; CitationAbt 2014; CitationFan Ke 2004.

10 Since the early twentieth century, scholars have largely accepted the notion of Pu Shougeng’s Muslim origin, and it remains the dominant view, based on the works of Kuwabara Jitsuzō, especially his monograph of 1923 (CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1923). However, some scholars have recently questioned Pu Shougeng’s identity, pointing out that there are no well-authenticated contemporary Song or Yuan sources that explicitly mention Pu’s Muslim origin. For the latest work refuting the authenticity of the main source on which Kuwabara bases his assertion, see CitationHaw 2015, pp. 317–325. For arguments in favor of its authenticity, see CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 2, 9–13; CitationZhong Han 2007.

11 CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 1–6; CitationSo 2000, pp. 108–109. Another view, relying mainly on genealogical entries, maintains that he was a descendant of a renowned Song official from Sichuan who also originated from Western or Central Asia. See CitationLuo Xianglin 1959, pp. 11–37. For a summary of the different theories, see CitationLi Yukun 2001, pp. 17–19; CitationChaffee 2017, pp. 65–66.

12 CitationLuo Xianglin 1959, pp. 60–62.

13 CitationSo 2000, pp. 108, 110–114, 301–305; CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 35–38.

14 CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 39, 57–59.

15 The history of Pu Shougeng and his family has been detailed by several researchers, from the early twentieth century to the present. Most works are based predominantly on official historical sources and deal with the origin, official posts, and biographical data of the early Pu ancestors. It is not the aim of this article to review all available sources on Pu Shougeng and other renowned Pu descendants. The most recent comprehensive addition to the study of Pu Shougeng is that of CitationJohn Chaffee (2017). See also CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1928, Citation1935; CitationLuo Xianglin 1959; CitationPu Faren 1988; CitationSo 2000, pp. 301–305; CitationLi Yukun 2001, pp. 16–23; CitationMukai Masaki 2010, pp. 428–445.

16 CitationChan Hok-lam 1976, pp. 29–37.

17 So claims that Pu Shougeng’s political influence, though significant, was confined to Quanzhou and did not extend beyond the prefectural level. CitationSo 2000, pp. 114–115, 117, 303–305; CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 40, 66, 80–87; CitationMukai Masaki 2010, pp. 428–445; CitationChaffee 2017, pp. 67–68.

18 CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 66, 80–87; CitationChaffee 2017, p. 68; CitationMukai – Fiaschetti 2020.

19 Pu Shougeng himself appealed to the throne a year later (1281), reporting that he was only able to complete 50 of the 200 ships, and the emperor cancelled the order. CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, p. 87.

20 CitationChaffee 2018, p. 149; CitationLuo Xianglin 1959, pp. 71–72, 89.

21 CitationChaffee 2018, p. 149; CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, pp. 224–225.

22 CitationChaffee 2017; CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 67–68, 92–96 notes 14–17; CitationLuo Xianglin 1959, pp. 73–74, 90; CitationPu Faren 1988; CitationSo 2000, pp. 115, 301–305; CitationLi Yukun 2001.

23 我太祖皇帝禁泉州蒲壽庚,孫胜夫之子孫,不得齒于仕類,蓋治其先世導元傾宋之罪,故終夷之也. Quannan zazhi, juan 2.

24 皇朝太祖禁蒲姓者不得读书入仕. Minshu, juan 52.

25 CitationSo 2000, pp. 303–305; CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, pp. 35–40; CitationLuo Xianglin 1959, pp. 39–41; CitationChaffee 2006, p. 409.

26 Like the rest of the Han population of Southeast China, members of families of Muslim descent strictly observe the rules of ancestral worship. However, they also observe several unique customs that include a pork taboo and offerings of ancient Quran manuscripts. These special customs do not reflect Muslim observance but rather the widely prevalent Chinese creed of satisfying the needs and desires of deceased ancestors who, in this case, would not have relished pork. CitationAbt 2012, pp. 69–139; Citation2015; CitationGladney 1996; CitationFan Ke 2004; Citation2006.

27 The genealogical biography appears in CitationLiu Zhicheng 1985, p. 57.

28 CitationZhuang – Zhuang [1978] 1983, p. 236; CitationLiu Zhicheng 1985; Citation1983, pp. 105–108; CitationChaffee 2017, p. 74; Citation2018, p. 167.

29 The original text mentions the seventeenth year of the Hongwu reign period as 1387, whereas in fact it should be 1384.

30 由泉州府學生員中洪武十七年丁卯科舉人, 後應洪武三十年丁丑科令試, 中第九名進士, 殿試第二甲二十五名, 點選翰林院編修之職. 告老致仕, 移居 … 古榕鄉. CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, pp. 225–226.

31 CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, p. 225.

32 CitationSzonyi 2017; Citation2002, pp. 64–68.

33 This claim appears in the Pu shi jiapu, a newly compiled, untitled manuscript genealogy of the Yongchun Pu family.

34 CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, p. 218; CitationGladney 1996, p. 273.

36 CitationSzonyi 2017; Citation2002, pp. 28, 36, 39–42, 64–68, 234n21, 236n41.

37 Fieldwork conducted by the author in Dongshi in 2002 and 2009.

38 CitationZhang – Jin 1983, p. 224. Zhang Yuguang and Jin Debao will be discussed further later in this essay.

39 CitationLiu Zhicheng 1985, pp. 55–59.

40 A modern punctuated edition (see Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu) was published as a volume in the Zhongguo Huizu guji congshu 中国回族古籍丛书.

41 歷朝譜例,族內有犯官刑而死,系罪有應得者,如謀反,大逆,不孝被出,為盜被戮,犯奸被殺,等,一概萷名不錄,以兩方空如此□□代之,示不齒於族。從歷代名家譜例也. Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu, p. 2.

43 The Fujian and Guangdong genealogies also include chronological and biographical inconsistencies that raise several questions. CitationLuo Xianglin (1959, pp. 11–37) is of the opinion that the two genealogies represent two separate families of Muslim descent.

44 考我初太祖,宋時人,慕孔道,自西域入中國。初三世叔祖,以元泰定丁卯舉蒙古色目榜進士。[…] 舊譜俱載西域回紇人。考西域即蒙古地,唐宋稱回紇,又曰回鶻. Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu, pp. 4–5.

45 CitationThoraval 1991, pp. 18–23; CitationPu Jiexi 2012.

46 This group, known as the Utsul (Huihui ren 回煇人) is not recognized by the state as a separate ethnic group but rather considered Hui.

48 In an attempt to cope with growing unrest, the late Yuan central goverment organized thousands of Quanzhou’s foreign residents into military units. Since many of these soldiers were of Persian origin, this local military force was called Ispah, a Persian term which means “military,” or sipahi, meaning a “soldier” or “knight.” CitationSo 2000, pp. 122, 348 n.77; CitationMaejima Shinji 1974, p. 50; CitationWu – Wu 2005, pp. 304–311.

49 CitationGuan Guiquan 1993, pp. 3–19; CitationWang Lianmao 1993, pp. 126–136.

51 The arrival of Suodu’s reinforcements caused the retreat of Zhang Shijie south to Guangdong. Yuanshi, vol. 118, pp. 3141–3161.

52 泉州故多西域人,宋季有蒲壽庚,晟,以平海寇得官。壽庚為招撫使,主市舶,壽晟為吉州,知宋運迄,錄不赴. 景炎間,益王南巡,駐蹕泉州港口,張世杰以准 [淮]兵三千五百人授壽庚,武人暴悍無謀,隻壽晟為畫計。益王篤臨城,教壽庚閉門不納,盡殺宋宗室在泉州者三十余人,併淮水軍無遺者。與州司馬田真子詣杭州,唆都降之. 張世杰回攻九十日不能克。壽晟部畫既定,併著黃冠野服,隱於法名寺。一日,晝寢,有書生二人,稱自潮州來。詩二首謁處士雲. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” pp. 50b–51b.

53 This is an allusion to the flight of the last Song emperor to the mouth of the West River and his drowning on 19 March 1279. CitationChen Yuan [1966] 1989, p. 15.

54 梅花落地點蒼苔,天意商量要入梅。蚨蝶不知春去也,雙雙飛過粉牆來。」「劍戟紛紛扶主日,山林寂寞閉門時。水聲禽語皆時事,莫道山翁總不知. For the poems, I use the translation of Ch’ien Hsing-hai and L. Carrington Goodrich of Chen Yuan’s work (CitationChen Yuan [1966] 1989). The poems appeared in the Ba Min tongzhi, vol. 86, p. 1008.

55 壽晟睡覺,閽人呈之,壽晟駭汗失措,亟馳人四出境,不知所覓。元君制世,以功封壽庚平章,為開平海省於泉州。壽晟亦居甲第一時子孫貴顯冠天下,泉人被其薰炎者九十年。至是,元政衰,四方兵起,國命不行. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” pp. 50b–51b.

56 The earliest is the 1490 Ba Min tongzhi. See ibid., vol. 86, p. 1008.

57 CitationChen Ziqiang 1983, pp. 244–246; CitationChen Yuan [1966] 1989, pp. 14–17; CitationThoraval 1991, pp. 14–15.

58 CitationMaejima Shinji 1974, pp. 55–57.

59 Although it is impossible to verify this claim through other historical sources, biographical records indicate that he indeed married a member of the Quanzhou Pu lineage. CitationSo 2000, p. 305.

60 While some researchers think Fanfo si 番佛寺 in Quanzhou was a Hindu temple and explain its establishment by the Southeast Asian origin of the Pu clan, others claim fanfo si was a term also used to describe Muslim prayer-houses and fanfo (“foreign Buddha”) stands for the Muslim “Alla.” See CitationNu’er 1982.

61 The year 1354 mentioned in the text is obviously a mistake since the events dealt with occurred a decade later.

62 其婿西域那兀吶襲作亂。 … 那兀吶既據城,大肆淫虐,選民間女兒充其室。 … 建番佛寺,極其壯麗,掠金帛,貯積其中。 … 至正甲午,遣騎攻興化. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” p. 51b.

63 「作亂者,那,蒲二氏耳,民皆協(脅)從。若戰,必驅協(脅)從者於前,官軍殺之何益?」請入城,行間,城中千戶金吉,亦回回種也,守西門。伊橚見者曰:「官兵誅回回,大至。公為守臣,能誅那兀吶,以迎官兵,不世功也。若待官兵 入,而後迎之,竊恐亂之際,不辨真偽,公進退狼狽也。」金吉大驚,與伊橚約就,夜開西門,密納陳弦兵入。那兀吶倉卒突騎出了城,扼戰,伊力執巨斧冒陣,砍百餘騎,擒那兀吶送京師. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” pp. 51b–52a.

64 福州軍至,發蒲賊諸冢,得諸寶貨無計。壽庚長於師文,性殘忍,殺宋宗子皆決其手,壙中寶物尤多。壙誌,瑪瑙石為之,翰林承首撰文,金陵人也. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” pp. 52a–52b.

65 凡西域人盡殲之,胡發高鼻有誤殺者,閉門行誅三日[…] 凡蒲屍皆裸體,面西方. […] 悉令具五刑而誅之,棄其於豬槽,報在宋行弒逆也. This passage is translated in CitationChaffee 2008, p. 122.

66 日和,字貴甫,壽晟公次子。秉清真教,慎言謹行,禮拜日勤。元至正間,清真寺損壞不治,裡人金阿里與之共成厥事,重修門第,皆以大石板砌成之,極其壯麗。右匾鎸有名字,至今猶存. CitationZhang – Jin 1983, pp. 225–226.

67 Up until the late Yuan, both the Ashab Mosque and the Qingjing Mosque existed in Quanzhou. The name of the former, Aisuhabu dasi 艾蘇哈卜大寺, derives from the Arabic Masjid al-Aṣḥāb مسجد الأصحاب (the Ashab Mosque). The event of restoring the Qingjing Mosque, which is referred to in Pu Rihe’s biography, occurred in 1349 and was documented by a stele written by Wu Jian 吳鑒. In 1507, the inscription on the original tablet was transcribed from the gazetteer of Quanzhou. This time, however, it was erected on one of the walls of the surviving Ashab Mosque. This is probably the source of confusion between the two mosques. CitationChen Dasheng 1983; Citation1984, pp. xv, 16–18. For a detailed updated discussion of sources analyzing the inscription see CitationYang Shao-yun 2015.

68 Here I use the translation into English provided in CitationChen Dasheng 1984, pp. 13–18. This work provides texts in Chinese, Arabic, Persian and English.

69 Genealogical evidence indicates that Pu Shoucheng married a woman surnamed Jin. However, I did not find any proof for the claim made by Pu Faren that it was Jin Ali’s aunt whom Pu Shoucheng married. This claim is problematic since Jin Ji, Ali’s father, was stationed in Quanzhou only in 1333, after Pu Shoucheng had most likely already died. It seems unlikely that Pu Shoucheng married Jin Ji’s sister. See CitationPu Faren 1988, pp. 8–9, 49.

70 Earlier genealogies of the Fujian Pu clan apparently did exist. CitationWu Wenliang (1957, p. 281) noted the existence of a Ming Jiajing 嘉靖 (1522–1566) manuscript genealogy named Quanzhou Nanmen Zhongsuo Puxing zupu 泉州南門忠所蒲姓族譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Lineage of Zhongsuo, Nanmen, Quanzhou). Other compilations may have existed prior to the 1507 renewed mosque inscription.

71 Translation into English from CitationChen Dasheng 1984, p. 16.

72 CitationChaffee 2017, pp. 72–73.

73 公平日輕財樂施,慈仁廣愛,敦尚回教、回人。泉中舊有清淨寺,圮廢歲久,公以木石一新,巨費靡算,樓宇壯敞,至今侈觀。回人德之,相率勒石壽功雲. “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu,” p. 9.

74 CitationMaejima Shinji 1974, pp. 58–63. His name is written incorrectly in the Ba Min tongzhi, according to Maejima, with Yu 余 instead of Jin 金.

75 See Chen Youding’s biography in Mingshi 12/124/3717. Translated in CitationMote – Twitchett 1988, p. 29.

76 CitationMaejima Shinji 1974, pp. 63–64, quoting the Ba Min tongzhi, vol. 87, which in turn cited the fifteenth-century text Zhizheng jinji 至正近記 (A Record of Recent [Events] of the Zhizheng Reign [1341–1368]).

77 CitationHuang Qiurun 2000, pp. 179–181.

78 蒲姓過去是回教的望族,且對國家這麼大的貢獻,現在有許多世界學者,專力研究蒲壽庚事跡。我們認為,蒲壽庚是回教中光榮的人,我們敬慕他,欽佩他。我們相信,你一定歡喜貴祖先的榮耀和偉業勛績。但是要知道,貴祖先原是回教人,你放棄回教,卻正是放棄了祖先過去在歷史上的光榮。你們應該仍回祖教籍,把你們祖先的過去勛績發掘出來,使他為蒲姓增光,為回教增光. CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, pp. 217–218.

79 我知道我們蒲家有做過丞相的人,但不知道實是誰. CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, pp. 217–218.

80 Liu Mengyan, Sun Shengfu, and Huang Wanshi were also Song officials who surrendered to the Yuan. See CitationKuwabara Jitsuzō 1935, p. 99.

81 The last statement was mentioned in the context of fighting against the Japanese invasion – the core purpose of the organization of which Zhang Yuguang was a representative.

82 是的,你們被剿不是你們貴先祖做了錯事,而是帝制時代恆有的現象。明太祖平民起義拿到政權,為顧及自己地位穩固起見,當然對一般曾擁有軍政權的族姓加以壓制,使其就范。那時不隻你們遭壓迫,連孫姓,留姓也一樣。明太祖下詔禁止蒲壽庚,留夢炎,孫勝夫,黃萬石 等的子孫入仕,這些事在歷史上都找得到的. 過去,因為政治關系,逼著你們反教﹔現在你們已知道這種情形,為著祖先,為著你們在歷史上的光榮,為著你們得到一個正確的信仰,為著便於參加救亡工作起見,我們都希望你同你們的姓族都仍回祖教籍. CitationZhang – Jin [1940] 1983, pp. 217–218.

83 The person who copied the genealogy was not prepared to reveal the original compiler and was uncertain when it was compiled.

84 Jinjiang shi, Dongshi zhen, Songshu Pu shi jinian tang 2002.

85 The Pu lineages of Hainan made a similar attempt in 1983 to erect a monument at the grave site of the Danxian founding ancestor in Panbu 攀步. Authorities, concerned by the prospects of large-scale gatherings, declined their appeal. CitationThoraval 1991, p. 67.

86 CitationThoraval 1991, pp. 66–69.

88 CitationThoraval 1991, p. 26.

89 CitationGladney 1996, p. 273.

90 CitationLe Goff 1992, p. 99.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Genealogies

- Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu 南海甘蕉蒲氏家谱 (Genealogy of the Pu Family of Ganjiao, Nanhai). Zhongguo Huizu guji congshu 中国回族古籍丛书. Ding Guoyong 丁国勇. [1619]. Tianjin: Tianjin guji chubanshe, 1987.

- Pu Jiexi 蒲皆禧. [1619] 2012. Nanhai Ganjiao Pu shi jiapu 南海甘蕉蒲氏家谱 (Genealogy of the Pu Family of Ganjiao, Nanhai).

- Pu shi jiapu 蒲氏家譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Family). Yongchun, Fujian. Undisclosed compiler. Undated manuscript.

- Pu shi zupu 蒲氏族譜 (Genealogy of the Pu Lineage). Pu Faren 蒲發軔. Tainan: Shijie Pu xing zongqin zonghui, 1986.

- “Qingyuan Jin shi zupu” 清源金氏族譜 (Genealogy of the Jin Lineage of Qingyuan). Jin Zhixing 金志行. 1555.

- Zhang Yuguang 张玉光 – Jin Debao 金德宝. [1940] 1983. “Baogao fajian Pu Shougeng jiapu jingguo” 报告发见蒲寿庚家谱经过 (A Report on the Discovery of the Pu Shougeng Genealogy). Yue Hua 月華 1940/1–3. Reprinted in Quanzhou haiwai jiaotongshi bowuguan 泉州海外交通史博物馆 1983, pp. 216–226. This account contains the surviving portion of the text of the Pu shi jiapu 蒲氏家谱 compiled during the Kangxi period (1662–1722).

Dynastic Histories, Local Gazetteers and Other Primary Sources

- Ba Min tongzhi 八闽通志 (Comprehensive Gazetteer of the Eight Min Prefectures). Huang Zhongzhao 黃仲昭. [1490]. Reprinted Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe, 2006.

- Chen Dasheng 陈达生 (ed.). 1984. Quanzhou Yisilanjiao shike 泉州伊斯兰教石刻 (Islamic Inscriptions in Quanzhou). Quanzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe.

- Minshu 闽书 (History of Fujian Province). He Qiaoyuan 何乔远. [ca. 1628]. Reprinted Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe, 1994.

- Quannan zazhi 泉南雜誌 (Miscellaneous Notes on Quannan). Chen Maoren 陳懋仁 [ca. 1600]. Reprinted Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1936.

- Wu Wenliang 吳文良. 1957. Quanzhou zongjiao shike 泉州宗教石刻 (Religious Inscriptions of Quanzhou). Beijing: Kexue chubanshe.

- Wu Wenliang 吴文良 – Wu Youxiong 吴幼雄. 2005. Quanzhou zongjiao shike 泉州宗教石刻 (Religious Inscriptions of Quanzhou). Revised edition. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe.

- Yuanshi 元史 (The Official History of the Yuan). Song Lian 宋濂 [1310–1381]. Repr. Taipei: Ershiwushi bian kan guan, 1956.

Secondary Sources

- Abt, Oded. 2012. “Muslim Ancestry and Chinese Identity in South-East China.” Ph.D. diss., Tel Aviv University.

- Abt, Oded.. 2014. “Muslim Ancestor, Chinese Hero or Tutelary God: Changing Memories of Muslim Descendants in China, Taiwan and the Philippines.” Asian Journal of Social Science 42 (2014) 5, pp. 747–776.

- Abt, Oded. 2015. “Chinese Rituals for Muslim Ancestors.” Review of Religion and Chinese Society 2 (2015) 2, pp. 216–240.

- Bradsher, Keith – Amy Qin. 2021. “China's Crackdown on Muslims Extends to a Resort Island.” The New York Times, February 14, 2021.

- Chaffee, John W. 2006. “Diasporic Identities in the Historical Development of the Maritime Muslim Communities of Song-Yuan China.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 49 (2006) 4, pp. 395–420.

- Chaffee, John W.. 2008. “Muslim Merchants and Quanzhou in the Late Yuan – Early Ming: Conjectures on the Ending of the Medieval Muslim Trade Diaspora.” In: Angela Schottenhammer (ed.), The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 115–132.

- Chaffee, John W.. 2017. “Pu Shougeng Reconsidered: Pu, His Family, and Their Role in the Maritime Trade of Quanzhou.” In: Robert J. Anthony and Angela Schottenhammer (eds.), Beyond the Silk Roads: New Discourses on China’s Role in East Asian Maritime History. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 63–75.

- Chaffee, John W.. 2018. The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China: The History of a Maritime Asian Trade Diaspora, 750–1400. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chan Hok-lam. 1976. “Chang Shih-chieh.” In: Herbert Franke (ed.), Sung Biographies. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, pp. 29–37.

- Chen Dasheng 陈达生. 1983. “Jin Ali yu Qingjingsi” 金阿里与清净寺 (Jin Ali and Qingjingsi). In: Quanzhou haiwai jiaotongshi bowuguan 1983, pp. 126–130.