ABSTRACT

Taking a cue from Gottfried Boehm’s Bildkritik, I consider the iconoclastic ruination by protesters in 2016, of the statue of the first State President of the Republic of South Africa, on the campus of the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein. With reference to other sculptures and image events on this campus, debates are transposed from the more usual South African visual culture studies perspective on iconoclasm, to an image studies perspective. This entails that the importance of the nature and historical agency of image objects themselves over centuries, in the process of iconoclastic events, is considered when analysing the current event. I argue that although the persistently “desiring image” may sometimes invite enthrallment and hopeless violence, there is a strong strand in image theory and history, to support its potential projection of hospitality and communion to open horizons of expectant futurity. The historical awareness of the power of images to critically unfetter cultural imaginations in a country predisposed by a complex colonial history, may aid the reconsideration of colonialism’s symbolic exclusions, rather than perpetuate its patterns of symbolic violence.

This article considers the case of the iconoclastic dismantling, burning with tyres, “drowning” and partial painting, by protesters on 22 February 2016, of the sculpture by Johann Moolman (1991) of the former alumnus and first State President of the Republic of South Africa, president C R Swart, on the square in front of the law faculty building on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State (UFS).Footnote1 ()

Figure 1. Protesters poking a fire at the feet of the statue of State President C R Swart on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, on 22 February 2016. GALLO IMAGES/MEDIA 24. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 2. The dismantled sculpture of State President C R Swart on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa, supine in the pond in front of the Main Building of the UFS Bloemfontein campus, on 22 February 2016. Photographer: Lesego Motsiri. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

Figure 3. The hands and face of the sculpture of State President C R Swart painted in black on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa, on 22 February 2016. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

In analysing the iconoclastic ruination of the sculpture in the context of the presence of other image objects and events on the UFS campus, I ask, what does rich and long–standing philosophically based art historical theorization on iconoclasm reveal about this local, current instance of iconoclasm? Is iconoclasm inherently violent and destructive or may it be an act of hope? Are images (in)destructible? Can Images Kill? as Marie–José Mondzain (Citation2009) has asked. With reference to this specific case, how may inferences from reflections on such questions, inform future decisions about the retention, removal or replacement of statues, their restoration and preservation, or their stabilization as ruined objects, on university campuses and elsewhere?

Answering these questions relies for me on a set of more fundamental questions: how does knowledge of the nature or ontology of images enrich our understanding of the topical social and political relevance of the destruction of image objects? What does the history of iconoclasm divulge more generally about the interpretation of images, and more specifically about the Heideggerian “violence of interpretation”? From these perspectives, debates are transposed from more usual South African visual cultural issues to more universal questions about the nature of images, the history of the power of images, and the topical relevance of such questions to the contemporary event. Whereas Jonathan Jansen (Citation2020, 119–139), the rector of the UFS at the time of the iconoclastic incident, makes sense of the events by inter alia relating them in a narrative sequence, I prefer to focus on those aspects of the occurrences which enlighten from the perspective of the history of iconoclasm, without repeating or debating his accounts.

I develop the ensuing argument by taking a cue from Gottfried Boehm’s aim in Bildkritik to contribute to the articulation of various types of image power, and of recognizing the contemporary relevance of the changing historical understandings of the functions and manifestations of the power of images. In the context of the complex entanglement of strands of Dutch and British colonial violence in the history of a culturally diverse South Africa, the harnessing of the power or desire of images to unfetter cultural imaginations may have creative and regenerative implications in the current environment.

1. Social justice

If the power or agency of images themselves is the focus here, the question must be: what is it about this particular sculpture of C R Swart, among all the other statues and sculptures on campus, that invited the violence it incurred?

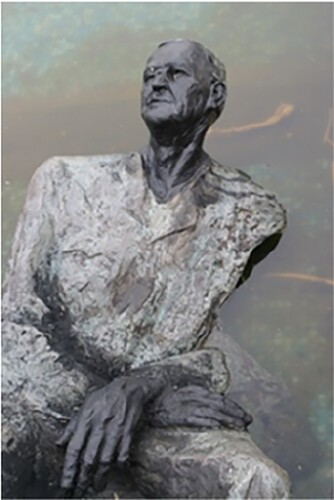

In the case of institutions of higher learning in South Africa the power of the state was made inappropriately (and diversely) present in centrally placed monumental portrait statues of statesmen and politicians, on respectively English– and Afrikaans–language university campuses at the beginning of the twentieth century. Since the time of the Union of South Africa the monumental bronze equestrian statue of British Imperialist Cecil John Rhodes by sculptor Marion Walgate was spectacularly located (1934), and even more spectacularly relocated (1962), on the English language campus of UCT, to honour him (ironically, in post–colonial terms), as benefactor of the land on which the campus had been built. Its removal, sparked by the Fallist campaign in 2015 (Schmahmann Citation2016), had global effects on student politics, as well as on the toppling of compromised public monuments in 2020 under the banner of the #BlackLivesMatter movement in Britain, the USA and elsewhere. Comparably, statues of Afrikaner Presidents of respectively the Free State Republic (1854–1899) (of President M T Steyn, by sculptor Anton van Wouw, 1929), and of the Republic of South Africa (since 1961), (of first State President C R Swart, by sculptor Johann Moolman, 1991), had been given pride of place on the square in front of the Main Building at the UFS, to commemorate their promotion of Afrikaans culture, including the foundation of Afrikaans universities. Therefore, in recent processes of nurturing more welcoming spaces for diverse students previously excluded from most South African universities, it is difficult to uncouple triumphalist reminders of British imperialism, from reactive Afrikaner responses upon this group’s experiences of state suppression and marginalization of Afrikaans language and culture under British dispensations. Arguably, by the iconoclastic ruination in 2016, of the statue of President “Blackie” Swart, approachably seated in a low armchair–like structure at its significant site between the law faculty building and the main university building, a certain placid interpretation and veneration of history is contested.

Unlike the elevated statue of Rhodes, the lowly positioned statue without a pedestal, of the seated figure of the lanky President C R Swart, placed accessibly not too high above eye–level, had not been intended, by the artist and commissioning committee, to enthral, but rather to emphasize the humble and accessible character the sitter was admired for by those who had interacted with him. The sedentary pose was decided upon when, after unforeseen delays of a number of years, the commissioned statue only became a reality in 1991 (Van den and Berg Citation2021). By this time, the university’s injudiciousness to honour a Minster of Justice of the apartheid era was evident, although Swart’s life of servitude and humility reminded of a difficult Afrikaner history. Swart was associated with traumatic—simultaneously emancipatory and deplorable—events in Afrikaner history, having been interned in the Winburg concentration camp during the South African War with his mother and siblings at the age of five, and having taken office during the apartheid era as Minister of Justice, among other positions, and eventually as first President of the Republic of South Africa from 1961 to 1967. The sculptural format of the personified virtue of humility—with its inherent historical ambiguity of loftiness and lowliness; dignity and meekness, self–determination and self–relativization (Barth 2014, 111)—points to the very problematics at the core of the western history of political bourgeois public monuments. Humility, a moral virtue that once had even exceeded the aristocratic virtues of bravery and wisdom, had lost prestige during modernity. Whereas humility is the epitome of Christian morality, human self–respect and pride were humanistic ideals related to human freedom and the dignity of self–determination. Martin Luther’s criticism of the virtue of humility emphasised its deeply ambiguous nature when he warned against its “secret pride” (Barth Citation2014, 110).

In 1991 when most of the premises of a Denkmalkultur or statuemania had been abandoned, the C R Swart sculpture embodied the crisis of the public statue, as well as of figurative artistic sculpture in the twentieth century. The continued existence of the monumentality and self–indulgence associated with statuary had for instance been parodied by artists like Claes Oldenburg and Gilbert & George earlier in the twentieth century (Michalski Citation1998, 8). Particularly after the Second Word War the problem of commemorating the victims of history rather than the makers of history has challenged artists (Koerner Citation2017, 18). Whereas sepulchral figurative sculpture by the end of the Middle Ages, and public figurative sculpture by the end of the Renaissance was monarchical and aristocratic, the bourgeois political statue gradually emerged in the three consecutive centuries until the nineteenth century. The figure–and–socle scheme thrived during the statuemania of the French Republic after the French Revolution when representations of the real person merged with allegory (Michalski Citation1998; Boime Citation1987).

Whereas the French Revolution remains the model for iconoclastic behaviour (Jones Citation2007, 241), the conduct of the 2016 protesters is historically reminiscent of the kind of retributive actions of drowning, burning and humiliation meted out to sacred sculptural objects during iconoclastic events of the Reformation in Europe (Cole and Zorach Citation2009; McColl Citation2009). During the Reformation, sculptures were often admonished for their paradoxical status of simultaneously being mere dead material and seemingly alive and powerful. The term iconoclasm refers to the smashing of an icon, face, personal likeness, or representation, often during this time of saints and the Virgin Mary. The faces of these objects were often addressed as if they were living persons, bargained with, and warned. Pamela Graves (Citation2008) has noted that in attacks on figurative objects in England during the Protestant iconoclasms of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, particular parts, like the hands and faces, were the focus, as in the severest forms of corporal punishment in public judicial acts. This, to her, adds a dimension of social justice and cultural appropriateness to iconoclasm, while keeping alive suggestions of harm to real human bodies. She notes that later during the seventeenth century, effigies of hated figures were publicly burnt. Since the Gutenberg era, effigies could also be replaced by prints, and the executioners of images during the Reformation were able to denigrate public figures by damaging pamphlets bearing the portraits of the Pope or of Martin Luther (Hofmann Citation1983, Koerner Citation2004). This is comparable in the modern world, to when posters of opponent political candidates are spoiled. However, the ruthless effects of the close connection between iconoclasm and censorship (Freedberg Citation2016) more recently appears in “cancel culture’—an iconoclastic ethos and practice of (often literally) “crossing out” (portraits of) subscribers on current social media platforms, and in controversies about, and deaths related to for instance the arguably iconoclastic Charlie Hebdo cartoons.

In terms of social justice, the iconoclastic event on the UFS campus could perhaps be interpreted as a collective reaction and effort by demonstrators to cleanse with fire and water, to dispel memories of the real and symbolic violences of apartheid, and, by painting the face and hands of Swart’s figure black, to invert the skin associated with power (), in order to restore their own agency through immersive participation in influential cultural acts from which they had been otherwise excluded. When, in the wake of the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall protests at (UCT) at the end of 2015, protesters in front of the law faculty set tyres alight on the C R Swart sculpture (see Jansen Citation2020; Schmahmann Citation2017), this act () reminded of (although it did not literally mimic) a long history of South African vigilante action of executing alleged political collaborators with the white apartheid government, by the brutal practice of “necklacing”.

A consideration of these current events in the light of the continuities and changes in the history of iconoclasm, points to the excessive power of images, of which we are especially aware in the digital era. Dario Gamboni (Citation1997, 50) observes, to gravely conclude his discussion of the close proximity of image objects to human beings—with reference to examples from inter alia Bosnia of the 1990s, Nazi Germany, and the case of Salman Rushdie: “The menace represented by such violence makes it all the more important to remember that even if there are many worlds of interpretation, they come into conflict in one and the same world.” More so, in the era of digital and social media, when the dissemination of digital reproductions of (sometimes staged) pictures of violent interactions with images, support horrific acts to real, random bodies. David Freedberg (Citation2018, 92–94) points to this disturbing post–modern development when he conjures up the destructions, intentionally recorded, of the Buddha effigy in the Bamyan Valley, Central Afghanistan in 2001, and of image objects in Syria by ISIS, while comparatively alluding to other acts of parading, similarly on video, kidnapped victims, and their executions.

2. Iconic difference and the power of images

It is exactly in the digital era that great theoretical interest arose in the agency of images, and in their ability to prefigure the specific reactions they elicit (e.g. Freedberg (Citation1989, Citation2018), Gell (Citation1998), Latour and Weibel (Citation2002), Mitchell (Citation2005), Mondzain (Citation2009), Bredekamp (Citation(2011) Citation2017, Citation2018), Eder and Klonk (Citation2016)). For Michael Ann Holly (Citation1996) “ … the function of beholding has already been incorporated in the image itself” and for Wolfgang Kemp (Citation1998, 181) historical objects of representational art are actively engaged in presaging the kinds of histories that can be written about them. I ask: Is there something more generally, in the very constitution of images themselves, which has continually in changing circumstances over many centuries, even in the modern image-saturated world, predisposed images to elicit intense responses and to invite some to be attacked, ruined, destroyed or dealt with in violent ways?

Gottfried Boehm’s definition of the nature of all images and pictures by means of the term “iconic difference” sets the stage for my consideration of this active role pictures seem to play in their own reception. In the subfield of image studies that he calls Bildkritik, Boehm has aimed to develop an extensive definition that would encompass ancient paintings on rock faces, icons, masks, easel painting, three–dimensional sculptures, drawings, photographs, image generating performances, diagrams, moving and digital pictures, virtual environments and so forth. He attempts to explain how it is possible for the facticity of pictorial material to transform into meaning in an image (Boehm Citation2011, 170–176). Most basically Boehm explains that iconic difference is: “ … the relation between the visible totality of the image and the manifold wealth of what it depicts” (Rampley Citation2012, 124). There is essentially a visually contrastive relationship in the form of an oscillation of two components and it entails the interconnectedness between what is visible and what is not (Boehm Citation2007, 59). Importantly, Boehm stresses that the image is an event in this definition, and that images cannot be images without this oscillating movement between identity and difference—hence his term “iconic difference”. To explain this, Boehm invokes Edmund Husserl’s evocation of the horizon (Boehm Citation2011, 174). On the cusp of the horizon the visible opens onto the invisible, and the invisible becomes visible to the imagination. Thus, the opaque impenetrability of material, sparks a flare of difference. The experience of a picture could therefore never be conclusive. In Jean–Luc Marion’s (Citation2011, 160) terms: “ … one must always first see it, make the experience of its irruption into visibility”.

The energy produced by this eventful oscillation is to my mind most fundamentally what makes images seem so alive as human–made agents of their own interpretations. If we “cannot reach the picture as picture” without such an event (Marion Citation2011, 159), it means that it forever remains the object of desire. The vision of the picture object as image, remains elusive, always lacking, unattainable, incomplete, constantly renewed in concrete events (Boehm Citation2007, Citation2011). This desiring property of all images as objects of iconic difference is my springboard to investigate the violence of iconoclasm here. This image understanding as event is in opposition to any quest for timelessness or to notions of the image as static or frozen. It explains the repeated and telling iconoclastic anxiety throughout its history, to demonstrate and display the “deception” of the image by emphasizing that it is mere dead material: “The idea is that the eye, previously bamboozled into perceiving the inert thing as a god, can now—soberly, critically, and actually—glimpse the thing as merely this or that material” (Koerner Citation2017, 6).

Whereas Boehm’s definition depends exactly on the event of this oscillation, Horst Bredekamp (Citation2011 (Citation2017, Citation2018)) refers to the theory of the (speech and) image act (Bildakt) to explain that it is in the paradox of lifeless starkness and vitality that the power of images lies, to make us act. What Bredekamp calls a paradox, W J T Mitchell (Citation2005, 7) refers to as a “double consciousness” of images as absurdly living things driven by the desires of appetites. David Freedberg recently attributes the power of images to elicit destructive acts, to the bodily viewing process:

We understand the stroke that produces the image, just as we understand the stroke that animates – that plunges – into a slashed Concetto Spaziale by Lucio Fontana, not by metaphor, but by biological actuality, by the arousal of the very neural correlates that would be activated if we ourselves were engaged in producing that stroke, or if we felt the wound in our bones. (Freedberg Citation2018, 90)

If images seem alive, the ways in which they make their shared presences accessible in public places, amplify their agency. Substitution through portrait images have not only defeated death over many centuries but have enabled simultaneous presence in different places over large territories (Summers Citation2011, 104) as in the case of statues of the Roman emperors. Ubiquity is part of the historical understanding of images as substitutive instruments of power. Although such experiences are embedded in ancient cultural practices, they are not obsolete in the contemporary world (Ginzburg Citation2001, 63–78; Freedberg Citation1989). The site bounded by the law faculty and main buildings on the university campus where the C R Swart sculpture and the President Steyn statue used to be instated, has special significance for the experience of place in the city. Energies exuded by planned vectors had shaped the early settlement of Bloemfontein since it was founded in 1846 by Major Henry Warden. Several architectural beacons built at various stages in the history of the city, like the main building, which was built between 1907 and 1909, terminated different vistas towards the surrounding horizon to create a finite sense of place in the vast landscape. This had an inward–tending effect and vertically halted outward–bound axes to provide a sense of security and containment (Du Preez and Swart Citation2009, 220). The domineering effect and potentially alienating presence and agency of the recently removed sculptures on the raised square in front of the main building were increased as a result of these energies. These axes had been designed in the context of prior sets of colonial relations and later of the separations which characterized city planning during the apartheid years. These abiding influences had perpetuated the illusive presence and experience of the powers of the past, in the present.

Additionally, iconoclastic reactions throughout history have pointed to the religious depth–dimension at the root of the validation and experience of images. Jan Assmann (Citation2011, 19) and W J T Mitchell (Citation2005, Citation2015) return to God’s prohibition of the making and worshipping of images in the second commandment, to explain their enduring power to enthral. When images are considered to possess the power to enchant and divinize the world itself, they presuppose immanence and dependence. Therefore, relationships of immanence and dependence in a divinized world are completely restructured and inverted in the monotheistic religions in which the whole world is regarded as the sacred throne above which the Divine God is enthroned (Assmann Citation2011, 20 −25). Similarly, the deep–rooted historical legitimation of images in the west, by the living Christ as Imago Dei or Image of God, and thus the living relationship between image and prototype in all human beings, remain fundamental also to recent theorizations of the nature of images (e.g. Hans Belting (Citation2006), Marie–José Mondzain (Citation2009, Citation2010), Jean–Luc Marion (Citation2004, Citation2011)). Deep–seated religious, mythical and sacred consciousness continues to endorse intense and violent reactions to images.

3. Violence

The very terms iconoclasm, vandalism, ruination, and abjection attest to a differentiation of various types of (image) destruction, considering that they often intersect. In modern western philosophy there is a distinct strand of the presumption of the violence of interpretation itself. For Martin Heidegger—if finite inter–subjective relations are characterized by domination—interpretation is bound to be structurally violent (Smith Citation2000, 100–103). The art historian Erwin Panofsky transposes Heidegger’s statement, when he quotes him in the context of art history (Elsner and Lorenz Citation2012, 506), to apply equally to image interpretation: “In order to wring from what the words say, what it is they want to say, every interpretation must necessarily use violence”. W J T Mitchell (Citation2005, 25) richly develops this idea in terms of the restless desire and lack of images:

What do images want from us? … What is it that they lack, that they want us to fill in? What desires have we projected onto them, and what form do those desires take as they are projected back at us, making demands upon us, seducing us to feel and act in specific ways?

Martin Warnke (Citation1973 (Citation1977), 96), following Adorno, has argued that modern art carries its own problematic nature or self–questioning within itself—that its tantalizing ambiguity already contains its own potential removal. He points out that a petrified tradition is the fixed point without which the new and different direction cannot be articulated. It is in this context that he invokes the hammer as an ambiguously destructive and creative iconoclastic tool. Gottfried Boehm (Citation2007, 56) has since argued, that more fundamentally than admitted by Adorno and Warncke, negation is a constitutive moment, not merely of modern art, but rather of the iconic act (or event) in general, in line with his term iconic difference.

The term “creative destruction” derives from Friedrich Nietzsche’s “critical idolatry” in his Twilight of the idols, or how to philosophize with a hammer (1889), as a responsible way of probing human thought and unveiling power structures—of “sounding out the idols”—as Mitchell (Citation2005, 20, 26) so compellingly discusses. It originally entered art historical discourse on iconoclasm through Martin Warnke (Citation1973 (Citation1977)), via economic studies from Joseph Alois Schumpeter’s book Capitalism, socialism and democracy (1942) (Fleckner, Steinkamp, and Ziegler Citation2010, 29) which describes the constant transformation of capitalist economic processes to remain productive. However, the rich religious connotations of destruction and renewal, as acknowledged in image theory has a longer history.

Joseph Leo Koerner (Citation2002, 164–213) discusses the confounding deficiency of images with reference to a medieval presentation of a Crucifixion to show that it is in the nature of images themselves to destroy in order to renew. He connects presentations of the Crucifixion, to Heidegger’s Durchkreuzung or “crossing through” which refers to the presence and absence of meaning in language (Koerner Citation2002, 196). The image (of the Crucifixion) is already abject, insufficient and ambiguous, but meant to train the eyes to see beyond the picture. The hammer, as instrument of poiesis as well as destruction, reminds that the mediating role of the materiality of an image cannot be overcome. The work of interpretation of a picture object may always be about noise, violence, suspicion and struggle even if the iconoclastically destroyed “image” remains alive. Iconoclasm, as much as it could be about arrogance, violence, triumphalism, fixity, lack of understanding and nihilism, also oscillates towards creativity, plenitude, futurity, promise and hope.

In his The Crossing of the Visible (2004, 69), Jean–Luc Marion describes participants’ relations to picture objects metaphorically, as relations to the faces of personhood. He poses two opposite possibilities of the “appearance” of these faces: that of the idol, and that of the icon; that of lack, and that of excess or surplus (Marion Citation2011, 152). For Marion this is revealed when in the reciprocal face of the image, “the origin of a counter–gaze that emerges from its unseen origin to regard me” is acknowledged. In the case of the icon, the counter–gaze of how the other (face or image) appears, “unseats” beholders as subjects, according to Marion, and allows them to change their response to it. On the other hand, the dazzling spectacle of the idol demands admiration and enthrallment; it freezes and absorbs the gaze, so that the idol remains a mere mirror image of itself. Images as idols for Marion are never at peace, whereas the iconic reciprocal relationship may heal the lack.

The inherent ambiguous potential of destruction as well as creation, of negation, or of “iconic difference” in images as such, poses challenges in their making as well as in their reception or destruction, to potentially enhance enthralment or otherwise to unlock new vistas.

4. Preservation and museumization

The consideration of questions of the preservation of damaged works usually invokes the multifaceted question of artistic value. Keeping in mind that diverse cultural values are attached to preservation and mortality, one may ask if, as in the case of family photographs or African masks, the lifespan of image objects should not be respected, after they had been expended (Summers Citation2011, 98). When art came to be seen as morally elevated, free and autonomous, exhibited behind the safe and hallowed walls of museums since the nineteenth century, and presumed to be addressed to individual spectators rather than social communities, the persona of the iconoclast became tainted in bourgeois society (Warnke Citation1973 (Citation1977); Gamboni Citation1997). Not only was the art museum instituted in Enlightenment culture to constitute a delimited space for cool detachment, combining aristocratic pleasure and civilian usefulness (Warnke Citation1973 (Citation1977)); it was also established as a place where “civilizing rituals” (Carol Duncan Citation1995) were to drain image objects of the so–called false consciousness of religious and ideological powers (Boldrick Citation2013). Although in this frame of mind, undesirable commissioned public art in political bondage is held artistically to be lacking in legitimacy and prestige, art has not ceased to be instrumentalized to serve political ends. Art remained, as Horst Bredekamp controversially argued in 1975, a “medium of social conflicts” (Bredekamp Citation1975). Martin Warnke (Citation1973 (Citation1977)) terms the historically assumed privilege of new regimes to display their power by means of the creation of new powerful symbols in public areas, replacing those of obsolete regimes, as “iconoclasm from above”. Commemorative portrait sculpture, insistently literal and three–dimensional, with its compelling effects of authority and agency to substitute human presence, commanding the space around it, has been used and misused for many centuries to anxiously express, impose and legitimate power.

Although modernism has conditioned us to aesthetically distanced, ironic approaches to abstract art, practises of conservation, neutralization, museumization, reconciliation and transformation may still affect violently. “Iconoclasm from below” (Warnke Citation1973 (Citation1977)) denotes a sense of impotence, and one could add aspirations of activism; violent appeals for transformation. Ruined statues under such circumstances, in the absence of venerating crowds, serve as illuminating social and cultural documents at significant historical junctures. Thus, a strong argument for their preservation as ruins, rather than their restoration, could be made. Mutilated and maimed image objects as an outcome of violent reception is often as informing as the original creations (Mochizuki Citation2008, 114–119).

Regrettably, the ruined C R Swart statue was not kept at the UFS but was donated in April 2017 to “Die Voortrekkers” cultural organization for the youth (founded in 1931), to be restored, and moved to Doornkloof, the Voortrekker farm near Lindley in the Free State Province. What could the possibilities have been of having repurposed and remediated the preserved ruin—as a historical and iconoclastic document; as a dialectical image with its new aesthetic of iconoclash (Latour and Weibel Citation2002), embodying both a regret of loss, and the relief of survival, as ruins usually do? Distinguishing between a damaged work and a ruin, Robert Ginsberg (Citation2004, 29) argues that whereas a damaged work misses something essential that can be replaced, and calls for repair, a damaged work may lose its unity and become a ruin with new possibilities of unity. The restoration of the statue to its previous form, single–mindedly re–establishes a previous order and one may ask: do processes of conservation, preservation, restoration, even protective museumization, not involve aspects of iconoclasm in themselves?

The very distinction between iconoclasm “from above” and “from below” points to iconoclasm’s close association with social, political and cultural power structures. The thrust of my argument here, however, is to bring attention to other types of image power (in Boehm’s sense) which may function to nuance and compare, rather than to divide and oppose. For Koerner (Citation2017, 5) iconoclasm, with its paradoxically high esteem for the power of images, is “grounded in the most intense of human distinctions – the dissociation of friend and foe … ”. As with traumatic experiences or psychic wounds, for iconophiles, as for iconoclasts, commemorative statues which are typically made to stubbornly endure, have lasting effects (Koerner Citation2017, 13). As ruin, the transformed C R Swart statue alluringly points to destruction as the other side of the coin of enthrallment. The poignant ruin thwarts the dualism of fascination versus aversion; enthralment versus violence.

The projected power of the ruin becomes stronger than the original sculpture, because of the deep–seated human ability to empathetically experience corporeal threat and psychic pain. In the context of the student protests the ruin as icon opens a view to what is taking place in a very specific moment in history, to see and not to miss, the consequences of past histories. The sculptural C R Swart ruin strongly projects the influence of the past on the future, like “colonial ruins” (Stoler Citation2013) which provide a means to analytically disentangle the aftermaths and less directly perceptible effects of colonial power on the lives of those who live with its remnants or debris.

5. Hospitality

For Paul Ricoeur (Citation1995, 8) “the past is not only what is bygone—that which has taken place and can no longer be changed—it also lives in the memory thanks to arrows of futurity which have not been fired or whose trajectory has been interrupted. The unfulfilled future of the past forms perhaps the richest part of a tradition. The liberation of this unfulfilled future of the past is the major benefit that we can expect from the crossing of memories and the exchange of narratives.” Such commemorative interactions with other histories, have the power to arrest the trend to romanticize struggle, violence and domination (Klapwijk Citation2009, 56).

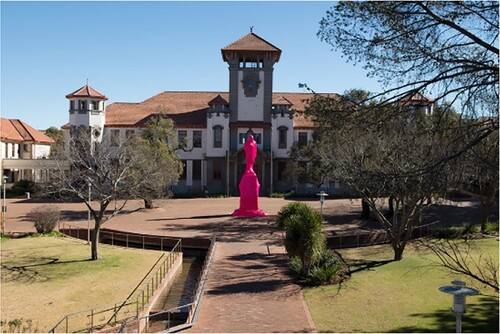

Prior to the iconoclastic event involving the statue of President C R Swart at the UFS in 2016, a coordinated process of critical self–scrutiny of communal spaces and statues had commenced. From 2009 to 2012 a grant of R 3,4 million from the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund was received by the University to implement the Lotto Sculpture–on–Campus Project. The aim (according to De Jesus on the UFS website) was to “set up diverse and site–specific sculptures that promote a greater understanding, respect and appreciation of cultural differences and instil a sense of belonging for all”. The plan implied a dialogical and profound interrogation through the medium of art, of existing monuments and sculptures, their genres and media and their figurative and heroic emphases.

Figure 4. Cigdem Aydemir. 2014. Plastic Histories Public Art Project by Cigdem Aydemir. July 7–14 August 2014. Wrapped statues on the UFS campus, of State President C R Swart, and of President M T Steyn. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

Figure 5. Cigdem Aydemir. 2014. Plastic Histories Public Art Project by Cigdem Aydemir. July 7–14 August 2014. Wrapped statues on the UFS campus, of State President C R Swart, and of President M T Steyn. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

As part of an experimental public art project for the Programme for Innovation in Artform Development (PIAD), in partnership with the Vrystaat Arts Festival, Plastic Histories by the Australian artist Cigdem Aydemir was commissioned in 2014. The C R Swart sculpture, as well as the statue of the 6th President of the Free State Republic, President M T Steyn on the university campus (together with those of other male statesmen in the city of Bloemfontein), were temporarily shrink–wrapped in bright, fluorescent pink plastic in 2014 ( and ). Some statues in the city, for which permission to wrap had been denied by the Free State Heritage Resources Authority (FSHRA), could be interactively viewed, coloured pink, on cellular mobile phone screens through an application (or app) specially designed for the project (De Jesus Citation2014; Miller Citation2017). This enabled virtual playful interaction with more statues. The pink shrink–packaging and colouring, while pointing to the dearth of female public commemoration, frivolously transformed an august tradition of monumental commemorative sculpture. This rich carnivalesque critique brought public attention to the “invisible” invasiveness and domination of overwhelming image objects over large public areas, otherwise understood to be inclusive.

Figure 6. Thomas Kubayi. Walking Fish (detail). 2010. Wild–fig wood, 550 × 155 × 90 cm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

Joseph Leo Koerner (Citation2017, 20) has resourcefully brought Freud’s concept of the Tummelplatz into the iconoclasm debate. Tummelplatz denotes a playground, romping ground or hotbed in the process of working through trauma, or of the labour of memory. Like suppressed memories and the refusal to be moved by them, monuments, in their stubborn and fixed endurance often become invisible and displaced into the subconscious. While the relegation of monuments (and of traumatic memories) to the subconscious may explain their ability to exert extreme responses, the creation of a “space for tumbling” to work through traumatic memories is as well known in the history of iconoclasm as it is in psychotherapy. The significant act of ritual submersion or “drowning” of the C R Swart sculpture is not only suggestive of the potency of statues as it lies submerged in the subconscious memory of iconophiles and iconoclasts alike but is also reminiscent of the drowning of holy statues during the Protestant Reformation (and of statues of political figures across the world under the banner of the #BlackLivesMatter movement in 2020) to demonstrate (ironically) the impotence of images. Similarly, the shrink–wrapping of the statues is comparable to the humorous treatment of holy images, and to their donation sometimes even to children to play with (Moshenska Citation2019) during the Reformation, to change attitudes towards them, to inspire radically different forms of attachment to them; and to experiment with irreverence to open a more nuanced space between reverence and violence.

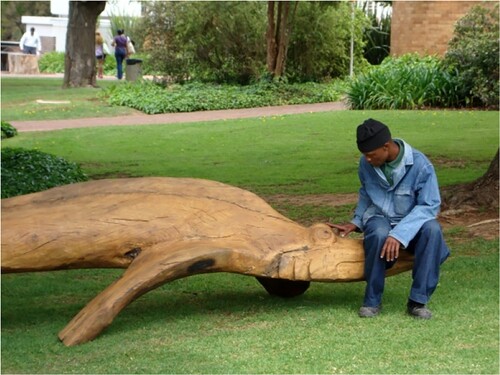

One group of works commissioned by the UFS as part of the Lotto Sculpture–on–Campus Project, was seven striking utilitarian sculptures made from wild–fig and olive wood by Azwifarwi Ragimana, a Venda artist from the Allubimbi village in the Limpopo Province. Installed in the garden quad behind the West Block of the main building in 2010, Walking Fish () and Adam and Eve () enable seated students to touch and stroke the driftwood limbs and human and animal shapes, while interacting with their fellows. These sculptures or anti–monuments in less permanent indigenous wood reform figural sculpture in that they invite animation by living bodies to fill and touch their shapes, to be incorporated by them in individual performative social events. The stroking gestures are rooted in relationships between vision, movement, and embodiment which span cultures and centuries. Such recurring emotionally charged gestures may be viewed as cross–cultural ways of sense–making over centuries, in terms of Warburgian pathos formulae. David Freedberg (Citation2010, 40), in his re–description of the meaning of Warburg’s pathos formulae in the context of his own research on human experiences of mirror neurons, argues that the perception of movement is fundamental to our understanding of the other. If image objects are able to empathetically induce acts of imaginative image making (Bildakt) or image breaking (Bildersturm), a myriad of possibilities of interaction are opened up by these bench sculptures—typical pro nobis human/image interactions as friendship relations—of mutual trust, intimacy, and the loyalty of equals. In the context of the aesthetics of protest in South Africa, a rich range of political, bodily interactions with images are possible.

6. Communion and accubation

Willem Boshoff’s sculpture, Thinking Stone was installed on the UFS campus in 2011 as part of the Lotto Sculpture–on–Campus Project. ( and ) This 21–ton flat Belfast Black stone was originally located unobtrusively off–centre from the tall stone plinth bearing the statue of M T Steyn (erected in front of the Main Building in 1929, and subsequently removed on 27th June 2020 to be relocated to Bloemfontein’s War Museum of the Boer Republics). In the garden, under the trees, it may be interpreted to quietly, iconoclastically, rethink the genre, materials and medium of monumental public commemorative sculpture in a subversive medium even more durable than “colonial bronze” (Gamedze Citation2015). David Goldblatt (Design Indaba Citationn.d.), in a 2014 lecture on some of his “photographic portraits”, concluded with a projection of his own photograph of Thinking Stone, and said: “It is to me an almost ultimate portrait”—reminiscent of Jean–Luc Marion’s description of the “unseating” of viewers by the “face” of the image.

Figure 8. Willem Boshoff. Thinking Stone. 2010. Belfast Black granite from Boschpoort Quarry, Mpumalanga. 4310 mm × 3200 mm × 450 mm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

Figure 9. Willem Boshoff. Thinking Stone. 2010. Belfast Black granite from Boschpoort Quarry, Mpumalanga. 4310 mm × 3200 mm × 450 mm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

On the university campus the inscribed stone denotes early cultural techniques of knowledge transmission, echoing those demonstrated at Driekopseiland, the heritage site of flat rock areas of dark sandstone in the Riet River near the town of Plooysburg, about 75 kilometres south–west of Kimberley in the Northern Cape. The three large, flat rocks at Driekopseiland, inscribed with 3,500 ancient petroglyphs, each uniquely different, is an early indigenous example of the use of cyphers as a cultural technique for the dissemination of knowledge. For Boshoff (Citationn.d.) it represents ancient indigenous acts of passing on knowledge, including those referred to as the “thinking strings” by the indigenous /Xam.

The flat, self–effacing and ambiguously humble installation of, paradoxically, a 21–ton granite rock, invites communion and conversation among diverse participants. The stone is also reiteratively inscribed on the inner edges of sculpted grooves (resembling cracks), with figures of speech about rock and stone in various South African languages that Boshoff had collected. Observers are intrigued and lured by the inscribed glistening surface of the stone, to sit on, kneel, touch, decipher, decrypt and attempt to translate the replicas of enigmatic ancient signs, as well as the engraved idioms in (ironically) sometimes incomprehensible, but indigenous languages. Captivated in crouching and stooping bodily postures induced by the puzzling image object, rather than enthralled in erect positions, they are gathered in acts of cultural and historical translation and historical intertwinement.

The indestructible granite object suggesting the layered embeddedness of learning at a university, protests the possibility of its own relocation. It rewrites history in sculptural form and invokes an inclusive and alternative communion among diverse groups, including ancestors: “The earth will always be the residence of the ancestors, the “old people”. Through accubation we share our food with them” (Boshoff Citationn.d.).

Boshoff’s work redeems the durable and archetypal sculptural material of stone, tran-substantiating it to proclaim hope and renewal. Moving away from figuration, he ostensibly reshapes the stone into transparently shimmering, primeval liquid, suggesting its igneous liquid substance. Thus, he contrasts natural and cultural acts and alludes to the gradual shaping of the local landscape “when the waters of the prehistoric Panatalassa receded, when glaciers impacted upon the land and when layer upon layer of topsoil became deposited and eroded over time” (Boshoff, Citationn.d.). With these references to pre–historic time, historical time with its human heroes, is relativized. A few years before the Fallist Movement of 2015, the work could already have been interpreted to have redeemed the fallen image, by substituting monumental height with blockish weight, stubbornly massive, unbudgeable and imposing, without being overpowering.

In other works by Boshoff using stone, e.g. Psephos (1996), he refers to the use in ancient Greece, of small round stones or psephos to cast votes in large ceramic jars. The use of stone as material, to allude to democratic processes, ironically reminds of the special political meaning in South Africa of stone throwing, which in the case of Thinking Stone is humorously thwarted by solid weight. Stone throwing additionally suggests the disarming statement by Jesus in John 8:7: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her”. The Biblical unobtrusive stone that the builders rejected which became the cornerstone (Acts 4:8–12 quoting Psalm 118:22), here almost literally becomes a stumbling block of history and emphasizes humility, prostration, community and hope.

7. Conclusion

In the oscillation between massive, immersive materiality and visionary communion, this iconic (in Marion’s terms) object challenges traditional figurative commemorative sculpture and projects a clear idea of what sculpture in the public sphere could be. In image theory, according to Marie–José Mondzain, a revolution in the understanding of images took place with the representation of the Incarnation when a new notion of the image entered Greco–Roman culture and new possible responses to images had been unlocked, as Mondzain (Citation2009, 23) explains: “The Passion of the image, occurs in the image of the Passion”. The Passion of the image had replaced tragedy and suspicion because the blindness of faith introduces trust:

Our eyes are opened by our ability to produce images, by our capacity to imagine. These capacities are why we need vision in order to speak; this is why the blind can speak as long as their capacity to imagine is intact. (Mondzain Citation2010, 308)

It is exactly base materiality which apparently defies interpretation and description, destabilizes vision and meaning, that thus may open new horizons as agents (Didi–Huberman Citation1989). As a medium of presence to the imagination it adds to and develops previous or other image notions like substitution, representation and imitation and image functions which prolong the earthly presence of the dead or establish human contact with a divine. In Gottfried Boehm’s definition the “image event” is the oscillation between impenetrable material and the energy produced by the flare of difference to criticize, give evidence, point to, and challenge the imagination in a variety of ways.

Lamentably, the perpetuation of a South African Denkmalkultur or statuemania, the roots of which date back to nineteenth century Paris, may still be observed in the contemporary spurning of an excess of South African counter–monuments; of gigantic perpendicular full–body sculptures in the Socialist–Realist manner. The repeated erection of statues of Struggle Heroes on unobtrusive or no pedestals, is reminiscent of such Communist practises during the twentieth century. The grass roots statues without socles—sometimes massive as in the case of the recently inaugurated 9–meter high statue of Oliver Tambo at the airport of that name, and sometimes in concentrated indulgence, as in the case of the envisaged 400 life–sized bronze statues (now already counting over 100) in a Long March to Freedom temporarily exhibited in the gardens of the Oliewenhuis Art Museum in Bloemfontein, later at the Groenkloof National Heritage Monument in Pretoria, and now at Century City in Cape Town—are openly promulgated as tourist attractions, and have as yet not entered university campuses. Even if Struggle Heroes are not mounted onto pedestals, as in the case of the statue of president C R Swart, in the social imaginary, Struggle Heroes remain part of disruptions on campuses. It is significant that, after the iconoclastic event involving the C R Swart sculpture in 2016, protesters proceeded from the scene in front of the law or Equitas Building, to the avenue with trees next to the Flippie Groenewoud Building, where they graffiti’ed in spray paint the names of Struggle Heroes onto some of the trees. The letters were reintroduced by the protesters after they had been removed and were subsequently once more deleted with paint by order of the university management. Students then requested that the avenue be renamed the “Pathway–of–Reflection” to link the respectively iconoclastic and commemorative events in one narrative, to “stimulate ongoing reflection” on ways to integrate the histories of the various communities on campus. Although the impulse to counteract colonial erasure is understandable, one may argue that it also perpetuates a typical iconoclastic cycle. Such an event of the damnatio memoriae of earlier “monuments”, had taken place the previous year during the “Shackville” protests as part of the #StatuesMustFall campaign on the UCT campus, when allegedly 23 selected paintings belonging to the University were burnt on a pyre (Makhubu Citation2020).

In a speech on Heritage Day, on 24 September 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa (Citation2020) announced that: “We come from a history of prejudice and exclusion, and since democracy we have worked to transform the heritage landscape of our country. … Monuments glorifying our divisive past should be repositioned and relocated.” However, an attempt to simply turn image agents into image patients—to appropriate Alfred Gell’s terminology—by transmuting them into instruments of instruction (as Martin Luther had attempted to do), is not a footing for thoughtful conversations. Such efforts at disempowerment, just like museumization and restoration, are further forms of violence against the image. To merely disempower public statues in political bondage, to erase traces of associated iconoclastic events, and re–establish them separately, is to prolong an unpalatable history of division. It is rather deeply pondered programmes of reinterpretation and expansion that could open an artistic space for the creative reshaping of the cultural imagination by telling different multifaceted stories of imbricated histories, that may arrest the prolongation of a cycle of reactive political correction.

Whereas Willem Boshoff’s Thinking Stone had seemed to be in conversation with the stone plinth of the Steyn statue for the ten years between its installation in 2010, and the removal of the Steyn statue in 2020, the artist Sethembile Msezane, in an intervention called Chapungu—The Day Rhodes Fell, patiently positioned herself on the Jameson steps, for four and a half hours, in front of the crane which was lifting the chained Rhodes statue from its plinth at the University of Cape Town’s Upper Campus on 9 April 2015. Msezane is part of a network of black female artists who insert their bodies into contested zones. Clothed in a black leotard, a traditional beaded veil over her face, and wings tied to her raised arms, she represented the mythological Zimbabwean chapungu bird or African eagle—waiting but lifting her arms at intervals as if about to fly. Soapstone effigies of these imposing eagles are known to have been looted from the ruins of Great Zimbabwe by the British in the late 1800s and one such soapstone chapungu bird today remains in Cecil John Rhodes’s Cape Town homestead. Msezane (TED online, Citation2017) explains that according to legend there will forever be suffering in Zimbabwe until all the stolen birds are returned. Her counter–act of commemoration is about loss and mourning, as much as it is about the memorialisation of an historical event. Her statuesque but breathing body reminds of layered African spiritual traditions of commemoration and mourning which in conjunction incorporate ritual performances, but which have been erased, muted, and suppressed in a history of miscellaneous colonial encounters. According to Kwezi Gule (Citation2019, 277) such indigenous traditions have even more recently been eclipsed by state–controlled and state–choreographed public commemorative events striving for neutrality. Yet the quiet presence and endurance of Sethembile’s dignified and vulnerable pose speak of resilience; a vision possibly of future dispensations of shared commemorative traditions, entangled knowledge–making, cross–narration in the recounting of history, and reciprocal human and image relations.

South Africa is predisposed by its history to make a profound contribution to the reconsideration of colonialism’s spatial and symbolic exclusions without perpetuating its patterns of continued symbolic violence. Such a process is however impossible in a course of action centrally managed by the state, to the suppression of community involvement and mutual trust. When the anxiety and lack evoked by desirous monuments are artistically transformed into desire as a gift of hope, the violent and triumphalist chain of statuemania may be broken. Rather than attempt to disempower images, perpetual acts of division could be resisted by performances and curated exhibitions performing cross–narratives and re–contextualized stories about what history could have been, projecting promising futures. The artistic narration of new and entangled histories of communal presences may transfigure the idolatrous and regressive potential of images to enslave the spirit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I wish to thank Helene Strauss, Willem Boshoff, Dirk van den Berg, Martin Rossouw and Angela de Jesus for their sagacious comments and insights.

References

- Assmann, Jas. 2011. “What’s Wrong with Images?” In Idol Anxiety, edited by Josh Ellenbogen, and Aaron Tugendhaft, 19–31. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Barth, R. 2014. “The rationality of humility.” European Journal for Philosophy of Religion: 6(3): DOI: https://doi.org/10.24204/ejpr.v6i3

- Belting, Hans. 1994 (1990). Likeness and Presence. A History of the Image Before the Era of Art. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Belting, Hans. 2006. Das Echte Bild. Bildfragen als Glaubensfragen. München: C. H. Beck.

- Boehm, Gottfried. 2007. Wie Bilder Sinn Erzeugen. Berlin: Berlin University Press.

- Boehm, Gottfried. 2011. Ikonische Differenz. Glossar. Grundbegriffe des Bildes, 170–176. Rheinsprung II. Zeitschrift für Bildkritik.

- Boime, Albert. 1987. Hollow Icons: The Politics of Sculpture in Nineteenth–Century France. London: The Kent State University Press.

- Boldrick, Stacy, Leslie Brubaker, and Richard Clay, eds. 2013. Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Boshoff, Willem. n.d. Accessed November 18, 2020 https://www.willemboshoff.com/product-page/thinking-stone.

- Bredekamp, Horst. 1975. Kunst als Medium Sozialer Konflikte. Bilderkämpfe von der Spätantike bis zur Hussitenrevolution. Frankfurt a M.: Suhrkamp.

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2017. Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Translated by Elizabeth Clegg. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Bredekamp, H. 2018 [2011]. Theorie des Bildakts: Über das Lebensrecht des Bildes. [Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency] Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Camille, Michael. 1991. The Gothic Idol. Ideology and Image–Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cole, Michael, and Rebecca Zorach2009. The Idol in the Age of Art: Objects, Devotions and the Early Modern World. London: Ashgate.

- De Jesus, Angela. 2014. Plastic Histories Public Art Project by Cigdem Aydemir, July 7 – August 14, 2014. Catalogue. Accessed June 2022 https://issuu.com/joh_designs/docs/plastic_histories_catalogue2014.

- De Jesus, Angela. n.d. UFS Arts Home/Lotto Sculpture–on–Campus Project. Accessed June 2022 https://www.ufs.ac.za/arts/ufs-arts-home/general/lotto-sculpture-on-campus-project.

- Design Indaba. n.d. David Goldblatt: The ultimate portrait. 2014. Accessed June 2022 https://www.designindaba.com/videos/interviews/david-goldblatt-ultimate-portrait and https://www.designindaba.com/videos/conference-talks/david-goldblatt-life-through-lens.

- Didi–Huberman, George. 1989. “The art of not Describing: Vermeer – the Detail and the Patch.” History of the Human Sciences 2 (2): 135–169. doi:10.1177/095269518900200201.

- Duncan, Carol. 1995. Civilizing Rituals. Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge.

- Du Preez, Kobus and Gert Swart. 2009. “Free State, Northern Cape & Karoo”. In 10 + Years, 100+ Building: Architecture in a Democratic South Africa, edited by ‘Ora Joubert, 220. Cape Town: Bell Roberts.

- Eder, Jens and Charlotte Klonk. 2016. Image Operations. Visual Media and Political Conflict, 1–26. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Elsner, Jas, and Katharina Lorenz. 2012. “The Genesis of Iconology.” Critical Inquiry 38 (3): 483–512. doi:10.1086/664548.

- Fleckner, Uwe, Maike Steinkamp, and Hendrik Ziegler, eds. 2010. Der Sturm der Bilder. Zerstörte und Zerstörende Kunst von Antike bis in die Gegenwart. Berlin: Akademie.

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images. Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Freedberg, David. 2010. “Movement, Embodiment, Emotion.” In Cannibalismes Disciplinaires: Quand L'Histoire de L'Art et L'Anthropologie se Rencontrent, edited by Thierry Dufrêne, and Anne–Christine Taylor, 37–60. Paris: Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac & The Institut National D'Histoire de L'Art (INHA).

- Freedberg, David. 2016. “The Fear of art: How Censorship Becomes Iconoclasm.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 83 (1): 67–99. doi:10.1353/sor.2016.0019.

- Freedberg, David. 2018. “Iconoclasm.” In 23 Manifestos on Image Acts and Embodiment. Series: Image, Word, Action, edited by Marion Lauschke, and Pablo Schneider, 89–96. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Gamboni, Dario. 1997. The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution. London: Reaktion.

- Gamedze, Thuli. 2015. “Heritage for Sale. Bronze Casting and the Colonial Imagination”. Artthrob 20 November 2015. Accessed June 2022 https://artthrob.co.za/2015/11/20/heritage-for-sale-bronze-casting-and-the-colonial-imagination/.

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Ginsberg, Robert. 2004. The Aesthetics of Ruin. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 2001. “Representation. The Word, the Idea, the Thing”. In Wooden Eyes. Nine Reflections on Distance. Translated by Martin Ryle and Kate Soper, 63–78. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Graves, C. Pamela. 2008. “From an Archaeology of Iconoclasm to an Anthropology of the Body.” Current Anthropology 49 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1086/523674.

- Gule, Kwezi. 2019. “To Heal a Nation: Performance and Memorialisation in the Zone of Non–Being.” In Acts of Transgression: Contemporary Live Art in South Africa, edited by Jay Pather, and Catherine Boulle, 267–285. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Hofmann, Werner (Hg.) 1983. Luther und die Folgen für die Kunst. Ausstellungskatalog. Hamburg: Hamburger Kunsthalle.

- Holly, Michael Ann. 1996. Past Looking: Historical Imagination and the Rhetoric of the Image. Ithaca/New York: Cornell University Press.

- Jansen, Jonathan. 2020. “‘It’s not Even Past’. Dealing with Monuments and Memorials on Divided Campuses.” In Troubling Images. Visual Culture and the Politics of Afrikaner Nationalism Edited by Federico Freschi, Brenda Schmahmann and Lise van Robbroeck, 119–139. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Jones, Polly. 2007. “‘Idols in Stone’ or Empty Pedestals? Debating Revolutionary Iconoclasm in the Post–Soviet Transitio.” In Iconoclasm. Contested Objects, Contested Terms, edited by Stacey Boldrick, and Richard Clay, 241–260. Aldershott: Ashgate.

- Latour, B. and Weibel, P. (eds.) 2002. Iconoclash. Karlsruhe: ZKM.

- Kemp, Wolfgang., et al. 1998. “The Work of Art and its Beholder. The Methodology of the Aesthetics of Reception”, 180–196.” In The Subjects of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Mark A. Cheetham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Klapwijk, Jacob. 2009. “Commemoration: On the First and Second History.” Philosophia Reformata 74: 48–70. doi:10.1163/22116117-90000458.

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2002. “The Icon as Iconoclash.” In Iconoclash, edited by Bruno Latour, and Peter Weibel, 164–213. Karlsruhe: ZKM.

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2004. The Reformation of the Image. London: Reaktion.

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2017. “On Monuments.” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 67-68: 5–20. doi:10.1086/693701.

- Krüger, Klaus. 2001. Das Bild als Schleier des Unsichtbaren. Ästhetische Illusion in der Kunst der Frühen Neuzeit in Italien. München: Wilhelm Fink.

- Makhubu, Nomusa. 2020. “On Apartheid Ruins.” Third Text 34 (4–5): 569–590. doi:10.1080/09528822.2020.1835331.

- Marion, Jean–Luc. 2004. The Crossing of the Visible. Translated by James K. A. Smith. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Marion, Jean–Luc. 2011. “What we See and What Appears.” In Idol Anxiety, edited by Josh Ellenbogen, and Aaron Tugendhaft, 152–168. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- McColl, Donald. 2009. “Ad Fontes: Iconoclasm by Water in the Reformation World.” In The Idol in the Age of Art: Objects, Devotions and the Early Modern World, edited by Michael W. Cole, and Rebecca Zorach, 179–213. London: Ashgate.

- Michalski, Sergiusz. 1998. Public Monuments. Art in Political Bondage 1870–1997. London: Reaktion.

- Miller, Kim, and Brenda Schmahmann, eds. 2017. Public Art in South Africa. Bronze Warriors and Plastic Presidents. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. Tom. 2005. What do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. Tom. 2015. Image Science. Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mochizuki, Mia. 2008. The Netherlandish Image After Iconoclasm, 1566–1672: Material Religion in the Dutch Golden Age. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

- Mondzain, Marie–José. 2009. “Can Images Kill?” Critical Inquiry 36 (1): 20–51. doi:10.1086/606121.

- Mondzain, Marie–José. 2010. “What Does Seeing an Image Mean?” Journal of Visual Culture 9 (3): 307–315. doi:10.1177/1470412910380349.

- Moshenska, Joe. 2019. Iconoclasm as Child’s Play. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Msezane, Sethembile. 2017. Living Sculptures that Stand for History's truths? TEDGlobal lecture, Accessed September 2022 https://www.ted.com/talks/sethembile_msezane_living_sculptures_that_stand_for_history_s_truths?language = en.

- Ramaphosa, Cyril. 2020. Heritage Day Speech, 24 September 2020. Accessed February 2021 https://www.gov.za/speeches/address-president-cyril-ramaphosa-heritage-day-2020-24-sep-2020-0000#.

- Rampley, Matthew., et al. 2012. “Bildwissenschaft: Theories of the Image in German-Language Scholarship.” In Art History and Visual Studies in Europe. Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks, edited by Matthew Rampley, 119–134. Leiden: Brill.

- Ricoeur, Paul. 1995. “Reflections on a New Ethos for Europe.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 21 (5/6): 3–13. doi:10.1177/0191453795021005-602.

- Schmahmann, Brenda. 2016. “The Fall of Rhodes: The Removal of a Sculpture from the University of Cape Town.” Public Art Dialogue 6 (1): 90–115. doi:10.1080/21502552.2016.1149391.

- Schmahmann, Brenda. 2017. “A Thinking Stone and Some Pink Presidents: Negotiating Afrikaner Nationalist Monuments at the University of the Free State.” In In Public art in South Africa. Bronze Warriors and Plastic Presidents Edited by Kim Miller and Brenda Schmahmann, 29–52. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Smith, James K. A. 2000. The Fall of Interpretation. Philosophical Foundations for a Creational Hermeneutic. Downers Grove, IL: IVP.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2013. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Summers, David. 2011. “Iconoclasm and Real Space.” In Idol Anxiety, edited by Josh Ellenbogen, and Aaron Tugendhaft, 97–116. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Van den Berg, Dirk. 2021. Interview held in July 2021, in Bloemfontein, with former Chairperson of the Advisory Board of the Johannes Stegmann Art Gallery, UFS, and of the Commissioning Committee of the C R Swart statue.

- Warnke, Martin. (Hg.) 1973 (1977). Bildersturm: Die Zerstörung des Kunstwerks. München: Carl Hanser.

- List of visual material

- 1. Protesters poking a fire at the feet of the statue of State President C R Swart on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, on 22 February 2016.

- 2. The dismantled sculpture of State President C R Swart on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa, in the pond in front of the Main Building of the UFS Bloemfontein campus, on 22 February 2016. Photographer: Lesego Motsiri. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 3. The hands and face of the sculpture of State President C R Swart painted in black on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa, on 22 February 2016. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 4. Cigdem Aydemir. 2014. Plastic Histories Public Art Project by Cigdem Aydemir. July 7–14 August 2014. Wrapped statue of President C R Swart. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 5. Cigdem Aydemir. 2014. Plastic Histories Public Art Project by Cigdem Aydemir. July 7–14 August 2014. Wrapped statue of President M T Steyn statue. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 6. Thomas Kubayi. Walking Fish (detail). 2010. Wild–fig wood, 550 x 155 x 90 cm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 7. Azwifarwi Ragimana. Adam and Eve. 2010. Olive wood, 240 x 133 x 142 cm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 8. Willem Boshoff. Thinking Stone. 2010. Belfast Black granite from Boschpoort Quarry, Mpumalanga. 4310mm × 3200mm × 450mm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.

- 9. Willem Boshoff. Thinking Stone. 2010. (Close–up). Belfast Black granite from Boschpoort Quarry, Mpumalanga. 4310mm × 3200mm × 450mm. Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Image courtesy of the UFS Art Gallery.