ABSTRACT

This study aims to explore the multifaceted aesthetic, social and cultural metaphors, and implications behind the portrayal of the goddess in Gu Kaizhi’s (顾恺之, 344–406CE) handscroll painting entitled Nymph of the Luo River (Luo Shen Fu Tu 洛神赋图) in the field of iconographic and spatial studies. The paper argues that the artist’s portrayal of the female figure in a revolutionary style, along with his adventurous emphasis on the close relationship between characters and nature, is more visually appealing compared to the established pictorial paradigm and symbolic significance assigned to the female figure by painters of the Han Dynasty (202BCE–9CE, 25–220CE). However, despite the artistic breakthroughs mentioned above, Gu neither fully challenges the hegemony of the metaphorical social order in paintings nor the long-standing oppressed status of women from previous dynasties. Thus, although the goddess of Luo appears to have achieved gender and physical liberation within the confined “heterotopia” space, the tense pictorial relationships create an iconological paradox, which confirms the order of patriarchal norms and the visualised framework of masculine cultures.

Introduction

In contrast to the figure paintings of the Han Dynasty (202BCE–9CE, 25–220CE), which primarily served didactic purposes and focused on the established ethical and moral principles, the construction of female figures in Six Dynasties’ paintings (220–589CE) witnessed a dramatic change in artistic styles and forms. This reflects the impact of ideological emancipation movement and cultural awakening, especially the growing recognition of the autonomous aesthetic values of paintings among cultural elites during this period (Ye and Zhu Citation2015, 161). Specifically, due to the social upheavals of the Eastern Han Dynasty and the collapse of the cultural hierarchy within which the Confucian ethical norms were predominate (Luo Citation2005, 1; Yu Citation2016, 1), the core role of the painting’s didactic function also has encountered widespread challenges from “new” cultural elites. The convergence and collision of religious, social, and cultural trends encouraged artists to engage in an artistic exploration of the “living experience” in portraying women. Thus, the handscroll painting entitled Nymph of the Luo River, a representative artwork of the Six Dynasties, received extensive scholarly attention and has been thoroughly studied as a typical example of goddess figure in Chinese art history. Wu (Citation2019, 117) emphasises that it is the first Chinese artwork to positively express love and desire, thereby subverting the female portrayal stereotype within the Confucian ideology of the Han Dynasty. Wang (Citation2010, 19) also states that Gu Kaizhi (顾恺之, 344–406CE) attempts to portray a woman with profound humanity and emotion, challenging the dominant and rigid theme of “virtuous women” (lienü 列女) at the time. Many scholars have given “secularised” concern to the painting from the perspective of historical criticism and literary studies, such as the transcendent spirit of illusion, the aesthetic exploration of humanity liberation and ideological awakening (Xu Citation2020, 32–39; Zeng Citation2017, 12). However, the paper argues that those critical views can hardly provide a complete picture of the tension between content and form, as well as the complexity and intricacy of the contradictions presented by the painting. The complexity includes the multi-layered significance of a “naturalistic,” visually oriented elite cultural strategy, rather than being a purely mystical aesthetic and philosophical reflection of “metaphysics” in the Six Dynasties or the male gaze on the female figures.

In this paper, several visual materials are discussed, including paintings which depict female figures such as Nymph of the Luo River from Beijing Palace Museum collection, Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (Nü Shi Zhen Tu 女史箴图) from the British Museum collection, and Sympathetic and Wise Women (Lienü Ren Zhi Tu列女仁智图) from the Beijing Palace Museum collection. In fact, the handscroll painting Nymph of the Luo River is traditionally attributed to Gu Kaizhi, based on numerous historical records (Tang Citation1993, 894–903; Wang Citation2009, 130–145). It is critical to note that the original painting has been lost for centuries and many scholars consider the artwork from the Beijing Palace Museum be the copy from the Sung Dynasty (Chen Citation2012, 202; Tang Citation1961, 7–12; Wei Citation2011, 86). Even so, studying the replica remains valuable for understanding the original. Many studies, grounded in analysing the copy’s artistic style and correlating the content and characteristics with historical records and archaeological evidence, confirms its significance (Chen Citation2012, 92; Jin Citation2014, 206; Meng Citation2010, 13–18; Shih Citation2011, 92–123; Wei Citation2011, 86). Specifically, Jin (Citation2014, 206) believes the Sung Dynasty copy’s style closely aligns with artworks from the Six Dynasties, and it somewhat represents the artistic level of Gu’s era.

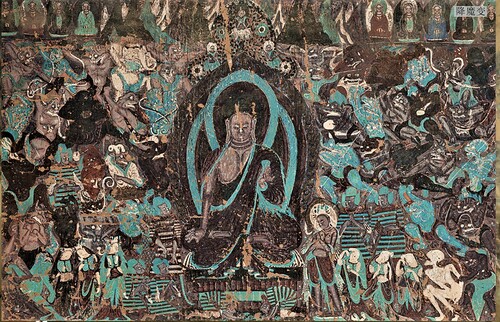

Additionally, the paper will explore some murals and coffin paintings from tombs of Han Dynasty and the Six Dynasties, such as the lacquer painting screen from the grave of Si-ma Jin-long (司马金龙) and murals from the tombs in Haotan (郝滩) County, to provide reliable evidence for tracing the origin of the visual elements featured in Nymph of the Luo River. Furthermore, the study will discuss the Buddhist murals from Mogao Caves (Cave 254, Cave 263 etc.) created during the Six Dynasties period, which depict the image of Vanquishing Mara (降魔变). Through this exploration, this article aims to compare the representation of female figures in Buddhist murals with those in the handscroll from the perspective of religious narrative and discourse.

Focusing on iconology and spatial studies, this paper attempts to demonstrate Gu’s artistic strategies and pictorial narrative in depicting the fusion of the goddess and the landscape in Nymph of the Luo River, highlighting its social, religious, and cultural meanings and metaphors. This strategy is not—as Eco-Feminism might hope—about achieving ideological and human emancipation by granting women the public space they have been denied in history; instead, this paper explores how this painting could be treat as a subversion of the “orthodox” aesthetic discourse of the Han Dynasty. At the same time, it can also be seen as a continuation of the masculine occupation, appropriation, and compression of women’s social space in the art discourse of the Han Dynasty.

Revolutionary strategies for portraying the Nymph

The socio-cultural environment of the Six Dynasties, in which established painting paradigms of previous dynasties coexisted with the “up-to-date” painting styles, inevitably contributed to the complexity of the artists’ works. However, the complexity often tends to be veiled by the “secularized” techniques of artistic creation.

More specifically, Nymph of the Luo River can be seen as a breakthrough in female figure paintings during the Wei-jin Dynasty. In terms of aesthetic strategies for shaping female figures in the painting (collect in the Beijing Palace Museum), Gu Kaizhi creatively interprets Cao Zhi (曹植, 192CE–232 CE)’s textual description of the gorgeous nymph (or goddess) of the Luo River. As presented in Cao’s poem Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River, Gu imaginatively portrays the romantic encounter between Cao and the nymph, as well as the sadness upon their parting. Gu’s representation of the poem showcases unique visual effects and incorporates a variety of innovative artistic expressions, such as chun chan tu si miao (春蝉吐丝描)—a technique of drawing smooth, soft, and slender lines using Chinese brush, resembling the silk produced by a spring silkworm. Besides, the colouring tone of the artwork is intense, thick, and classic, bearing a resemblance in style and features to the murals produced during the Six Dynasties (Chen Citation2000, 22). This reveals a different interest in painting from that of the Han Dynasty artists who rejected individual artistic expression.

Gu’s depiction of the stunning goddess goes beyond the artists’ conservative interest in merely symbolising and conceptualising female figures in the Han Dynasty. During the early Six Dynasties, most female figures in fine art inherited the stylistic paradigms of the Han Dynasty. According to Guo Ruoxu (郭若虚), a renowned Chinese art theorist in the eleventh century, these female figures are often depicted by artists as ancient goddesses with dignified looks, which means that viewers have to admire them with respect and admiration (Guo Citation2000, 40). Just as Cao Zhi (Citation2002, 257) pointed out in “A Preface of Eulogies to Portraits” (Hua Zan Xu 画赞序), a large number of painting from that time still plays a crucial role as “a mirror of morality to the society”. In other words, within the sociocultural context, the intension of artists to depict the beauty of ordinary women was not in popularity among social and cultural elites. Not until the Liu Song Dynasty (363–422 CE) did exquisite and aesthetically pleasing portraits of regular women gain popularity. These portraits are called “the painting of beauty” (Meirentu 美人图) or “figure of noble court ladies” (Gui qi tu 贵戚图) (Guo Citation2000, 18), coinciding with the emergence of luxurious social customs and the growth of hedonism (Chen Citation2016, 35). The artists no longer solely depict women as subordinate figures in a Confucian patriarchal society or being confined to a didactic function, breaking free from stereotypical painting standards.

To be Specific, in contrast to the stately and serene goddesses’ portraits in the Han Dynasty, there is a tendency that the artist tried to impart the goddess’s image with a secularised visage in stylistic painting language. For instance, the images of both “the Queen Mother of the West” (Xi Wangmu 西王母) in the stone carvings of the Wu Liang Shrine (武梁祠) and “the Mother Goddess” (Nüwa 女娲) on the portrait stones in Nanyang (南阳) during the Han Dynasty exemplify a solemn and distant portrayal. While the image of the nymph presents a graceful and unique appearance infused with vividness, thus diminishing the perceived remoteness of the interaction between mortals and deities, fostering a sense of intimacy. The artist depicts the nymph in a costume that echoes to the aesthetic tendency of the times, including Zaju chuishao fu (杂裾垂髾服) or Guiyi (袿衣) (Bian and Fang Citation2018, 145–152), referred to as “swallow-tailed hems and flying ribbons clothing”, which is a typical and formal attire of women elite in Six Dynasties, along with the era’s popular hair style, “the double-hooped hair bun” (Shuang huan ji 双环髻). Similar visual elements can be seen in Chinese portrait stones, tomb murals and screen paintings from the fourth to sixth centuries. For example, the lacquer painting screen from the tomb of Si-ma Jin-long (e.g. ) bears the portraits of women wearing “swallow-tail” clothing. The image of a woman with a double-hooped bun can be observed in the portrait brick from the Deng County tomb in Henan Province (Shen Citation2017, 262). Gu’s portrayal of the nymph showcased the intellectual elites’ aesthetic interests of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420CE), and precisely represents the resplendent goddess admired by Cao Zhi (see ).

Figure 1. Gu Kaizhi. Nymph of the Luo River. Handscroll (Detail). Ink and colours on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing.

Figure 2. The lacquer painting screen (Detail). The tomb of Sima Jinlong (484 AD). Shanxi Museum, Taiyuan.

Additionally, in the process of depicting the goddess, the artist draws inspiration from realistic figures while also emphasising the distinguished status of the goddess by integrating visual elements of mythological imagery into the painting’s background. These visual elements include expressive depictions of legendary gods, such as Fengyi(冯夷), Nüwa (女娲), Chuanhou (川后), and Pingyi (屏翳). Gu also renders the goddess’s chariot with six dragons, as well as the mythological creatures such as Wenyu (文鱼), Yuluan (玉鸾), and Jingni (鲸鲵). These captivating representation of legendary creatures are not solely a result of the artist’s creative imagination but also have roots in historical pictorial and textual sources. For instance, beyond Cao Zhi’s ode, the visual representation of Wenyu, is likely to be derived from the Chinese classic text Shan Hai Jing (山海经) (Yuan Ke Citation2014, 139) or was influenced by the Buddhist creature Makara, introduced to China from eastern India along with Buddhism during the Eastern Han Dynasty (Li Shaowei Citation2020, 56–59). Another visual element utilised to show her divine identity is the “auspicious clouds” (yunqi 云气 or xiangyun 祥云), which are depicted enveloping the nymph’s chariot. Indeed, yunqi has been a common and critical part of visual arts since the Han Dynasty, often associated with the symbols of “good omens” (xiangrui 祥瑞) and the thematic expression of being eternal and immortal (Hall Citation1995, 99; Wu Citation1984, 38–59). Those cloud-like decorative motifs can be found in some of Han Dynasty tomb murals, lacquer paintings, or coffin art, such as the mural of a man in a chariot surrounded by clouds (e.g. ) from an Eastern Han Dynasty tomb excavated in Haotan (Lü Citation2015, 86–90). Lastly, the nymph is adorned more elaborately and dynamically than the ladies in the painting Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies. To enhance her ethereal, fairy-like appearance, Gu highlights only the cloud-like train of her skirt, omitting the depiction of her feet, in contrast to the aristocrat women who are depicted wearing “toe-up-warped shoes” (Hutoulü 笏头履) in the same painting.

Based on the image-shaping strategies mentioned above, the pictorial representation of the goddess embodies, on the one hand, an aesthetic appreciation of life, love, and romanticism, which invites spectators to share artist’s experience of the visible. On the other hand, those strategies reflect the underlying “male gaze” or even an appreciation tinged with desire. In their works, Hang and Jiang (Citation2003, 105–107) believe that the image of the goddess no longer serves a role entrusted with the responsibility of proclaiming ethics and morality. However, this emancipation, embodied in the elegant and delicate aesthetic qualities characteristic of women, can hardly be seen solely as a result of women’s subjective liberation. A shift in men’s attitudes towards female figures at the time also needs to be taken into consideration. Specifically, the male character, Cao Zhi, always focuses his gaze on the nymph, leading viewers’ eyes to concentrate on the gooddess. The painting, to a certain extent, presents a typical pictorial paradigm proposed by Laura Mulvey (Citation1975, 6–18), which gives the feature of the female figure in visual art characterised by its “to-be-looked-at-ness”. According to Mulvey (Citation1975, 6–18), such visual arts objectify females in relation to the “controlling male gaze”, and she argues “the woman as spectacle and the man as the bearer of the look of the spectator”.

Gu utilises a series of pictorial strategies to highlight the “new” relationship between the goddess and the mortals. In earlier works, whose themes are about the romantic involvement between mortals and divine beings, the depiction of the goddesses often included subtle erotic and suggestive undertones veiled beneath mythological allusions, such as images of dissolute nymphs in Qu Yuan (屈原, 340–278 BCE)’s long poem Li Sao (离骚) and Song Yu (宋玉, 298–263 BCE)’s ode Gao Tang Fu (高唐赋). Departing from the tradition of portraying the goddesses, Gu focuses on the depiction of a romantic encounter with the goddess, and thus, the nymph has acquired a symbolic meaning as the “god of beauty and love”. However, in the tradition of Chinese culture, this symbolic image of women with love and lust, is not commonly accepted by society in an overt, conscious form (Ye Citation1997, 313). Thus, the overemphasis on the romantic relationship between the prince and the goddess has led to the painting receiving so little attention in the field of ancient Chinese art criticism, where the focus has traditionally been on the didactic and moralistic aspects of drawing (Xu Citation2020, 32–39).

In current research, some conservative approaches still hinder extensive scholarly exploration into the complexity and intricacies of the artwork. Additionally, the high degree of conformity between the ode and its artistic depictions has prompted many scholars to focus on the pictorial translation of the text and its narrative (Dai Citation2021), comparisons and analyses of artistic styles (Chen Citation2012), as well as discussions on the origins and variations of different versions (Shih Citation2011). This paper will not delve into controversies surrounding the themes of the literature or the artwork’s creation time. Instead, it argues that appreciating the female figures solely through a romantic lens or “male gaze” does not sufficiently explain the dramatic tensions and contradictions in the portrayal of the woman, as well as the relationships between the characters in the painting.

Shaping female figures and the continuing development of Confucian didacticism

Although Gu employs innovative artistic language to depict the nymph, the profound connection between Gu’s artwork and established social norms deserves further consideration. The depiction of the goddess has not entirely freed from the meaning of “didacticism” and the constraints of political and religious ethics. One of the focal points of the creative theme is the women’s self-sacrifice under the admonishment of political and religious conventions of Confucian society. In terms of artistic techniques, Gu’s depiction of the captivating goddess increases the tragic essence of the image’s narrative while also somewhat negating its “positive” significance.

Comparing Gu’s works from the same period can provide a more in depth comprehension about the painting. For instance, in Sympathetic and Wise Women and Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, Gu emphasises the function of painting in moral education for women, especially for court ladies. The former depicts fifteen stories of virtuous women, including “Mother of Sun Shuo-ao” (孙叔敖母), “Wife of Xi Fuji of Cao” (曹僖氏妻), “Wife of Duke Ling of Wei” (灵公夫人), etc. Those female figures exhibit a dignified and poised demeanour, and they are attired in clothing that reflects the fashion trends of the Eastern Han period, suggesting an elevated social status. In addition, the limited depiction of body language further highlights the exemplary and symbolic significance of the “gentle, humble, and frugal” Confucian ideal of women that has been prevalent since the Han Dynasty. Similarly, the purpose of the latter is also to educate and instruct women on their moral behaviour and it provides a visual description of the content of the poetic text written by Zhang Hua (张华), a poet in Western Jin Dynasty. Gu continued the pictorial language of portraying women from the original poem while creatively “transforming the imperfect imperial consorts, who were objects of criticism in the admonitory text, into flesh-and-blood female characters” (Wu Citation2019, 117). In the process of shaping these “negative” characters, Gu did not vilify them, but rather present themes in a subtle and indirect manner by using allusive and evocative language and imagery. For example, in the seventh part of the painting, the husband’s hostile body language conveys his disapproval of what he considers to be “immoral” behaviour in women. The female figure dressed in ornate garments assume an assertive stance as she “intrudes” upon male-dominated spaces, exhibiting a dynamic and physically expressive “aggressiveness”. It prompts vigilance and repulsion in her husband, the male figure who assumes a defensive C-shaped posture in respond to the female’s “assertiveness”. This sentiment is further emphasised by the cautionary message, “Dressing up to seek admiration is what a gentleman despises,” displayed on the right side of the artwork (see ). In contrast, the eighth part of the painting portrays a dignified and conservative female figure, emphasising the importance of being cautious and humble and having a “calm and self-reflective” demeanour to achieve prosperity and honour. This is conveyed through the woman’s slight bow and serene facial expression, which exudes a sense of subservience.

Figure 3. Gu Kaizhi. Admonitions of the instructress to the court ladies. Handscroll (Detail). Ink and colours on silk. British Museum, London.

Although the theme of admonition or didacticism is not the main purpose of Nymph of the Luo River, there are many similarities in Gu’s artistic strategies and drawing techniques for shaping the female image among those paintings. Specifically, the artist’s depiction of the graceful goddess, the emphasis on the seasonal and mythological elements in the background, and her active response to Cao Zhi’s love all highlight dual pictorial meanings. On the one hand, the image exemplifies the admiration of the literati in Six Dynasties for the idealised and virtuous female image. The use of visual elements in the background, such as the “autumn chrysanthemums” (qiuju 秋菊), “spring pine” (chunsong 春松), “roaming dragons” (yolong 游龙) and “flying swans” (jinghong 惊鸿), illustrates the beauty of the goddess described in the ode. On the other hand, the artist also employs the metaphorical imagery to emphasise the tragic consequences that the “transgression” of moral standards by women will inevitably bring. Cao was concerned about the story of Zheng Wenfu (郑文甫) being betrayed by a divine lady, and feared being deceived by the goddess, hence he maintained a strong sense of propriety (see ). In the face of the constraints imposed on women by the political and didactic norms, even a goddess seems to have no other choice but to express her resistance through mournful and sorrowful sighs. Just as Cao Zhi (Citation1986, 897) mentions in his ode, “With a long sigh and a prolonged chant, the goddess expresses her long-standing yearning, and her voice is mournful, distressing, and persistent”. Gu employs a variety of visual elements to present the emotions and struggles of the goddess. She is turning her head to gaze back at Cao, with her body forming a slightly curved arc. The sash draped over her body billows towards the right, swayed by an imaginary wind. Through the intricate language of her limbs, she conveys a sense of inner turmoil and sorrow. Additionally, the portrayal of Luo gazing back while seated on the chariot of clouds conveys yearning and sorrow and adds a sense of being constrained by the demands of ritual and propriety within the portrayal of the goddess in the pictorial narrative.

The artist’s praise of “beauty and sentiment” in the painting, while setting it apart from other artistic creations of the time that served the Confucian moral and political agenda, is filled with contradictions due to its underlying didactic meaning. The artwork contains a strong conflict between its expressive content and aesthetic orientation. In the original poem, Cao Zhi uses the first-person narration or “ich erzähler” (Genette Citation1990, 179) to convey the “the beauty in ill-fated emotions” between himself and the goddess, symbolising his own emotional or idealistic yearnings that find no outlet. Unlike the narrative viewpoint in the poem, the artist’s perspective in the image is that of a third-person or external observer. Nonetheless, the artist’s unavoidable self-projection and empathy in the process of creation and contemplation may also reflect the predicament faced by Six Dynasties literati, who despite the prevalence of corruption in the Confucian system and the collapse of the ritual music system, could not completely escape the values and ethics of Confucianism, nor the hierarchical constraints of feudal society.

Nymph of the Luo River and religious narrative

The tense interpersonal relationships presented in the painting reveal, to some extent, the asceticism advocated in religion such as “abstinence from extravagance” and “śūnyatā” (empty or void) (Fang Citation1982, 299), as well as negative attitudes towards women in early Buddhist discourse (Anālayo Citation2009, 136–190). For instance, women are not allowed to become a buddha because of their impureness and inability (Guṇabhadra Citationn.d, 1–30). Specifically, the painting of Nymph of the Luo River represents through a continuous narrative, five distinct stages of the story of Cao Zhi and the goddess of Luo. In terms of composition, the goddess is situated at the centre of the image due to the orientation of the “viewpoint”. This prominence is especially apparent when the painting is read from right to left, as if unfurling a handscroll, wherein the figures that come into the viewers’ eyes are Cao Zhi and his attendants (e.g. ). However, it is Cao’s gaze that is directed towards the goddess, thus maintaining her role as the primary aesthetic focus of the artwork. Especially comparing to the stylised, rigid body language of Cao Zhi, which lacked individualised artistic expression, the goddess is portrayed in a more responsive and interactive manner.

In the process of interacting with Cao Zhi, the goddess’s proactive responses paradoxically place her in an inferior position within the hierarchy of characters in the depiction: she emerges to interact with him, accepts his love gift, becomes the subject of his suspicions, and then departs in sorrow. Most scenes depict the goddess directing her stare and body language towards Cao. The artist portrays Cao with a level gaze and a composed posture, deliberately avoiding any interaction with the goddess, thereby creating a powerful visual conflict highlighting their mutual contradictions (“communication” versus “rejection”, “admonition” versus “romance”). Some scholars offer explanations for the contradictions in the painting. Wu (Citation2019, 117) believes the painting does not depict a direct interaction between Cao and the goddess but rather portrays a fantastic journey Cao describes to his attendants during a mental confusion, where he meets a beautiful woman; the handscroll represents a transition between dream and wakening. Cao’s gaze and his attendants’ downward gaze provide evidence for the visual and auditory relationships. Chen (Citation2012, 6) interprets the pictorial contradictions in painting of the Palace Museum from the perspective of the missing inscription. Compared to the Liaoning version which uses inscriptions to separate scenes and spaces, the Palace Museum version uses rocks and trees to fill the visual gap caused by the absence of “inscriptions”, forming a semi-closed circular space in the composition. Therefore, it may affect the understanding of the relationships between the characters, resulting in ambiguity in the plot. However, none of these explanations provide a reliable account for the unidirectional interaction between the goddess and Cao Zhi.

Starting with the profound influence of Buddhist thought on literary and artistic creation during the Six Dynasties, it may be possible to better understand the complex meanings and connotations beyond the pictorial language. Moreover, Gu’s close connection with Buddhist thought also provides a possibility to interpret the unidirectional interaction between the goddess and Cao Zhi from the perspective of religious art concepts. Specifically, since the introduction of Buddhism in China at the end of the Han Dynasty, particular during Emperor Xiaowu’s (魏孝武帝, 510–535CE) region, it exerted a significant influence (Tang Citation2017, 278). Famous monks and literati of the Six Dynasties closely interacted, and the mutual interpretation between Buddhism and Metaphysics (also called Neo-Daoist) has been a common phenomenon in intellectual circles (Luo Citation2005, 267). The integration of Buddhist and Neo-Daoist philosophical trends became the most important social and political thought of the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties (Fang Citation1982, 226), inevitably bringing significant impacts on artistic creation. Gu’s creative concepts and aesthetic thoughts were therefore influenced by multiple factors, notably Wei-Jin Neo-Daoism and Buddhist thoughts. Based on some historical records such as Chronicles of the Jian’an Era (Jian’an Shilu 建安实录), Record of the Monasteries in the Capital (Jingshi Siji 京师寺记), Record of Famous Painters of All the Dynasties (Lidai Minghuaji 历代名画记), it can be inferred that Gu had spent over a month at the Waguan Monastery (瓦官寺) painting the Portrait of Vimala-kīrti (Pan Citation1997, 271), and likely had some interaction with the monks there, including Shi Huili (释慧力) and Zhu Fatai (竺法汰) (Zhipan Citation2019, 136). Moreover, Eminent Monk Biography (Gaoseng Zhuan 高僧传) records that Gu wrote a biography for the eminent monk Zhu Fakuang (竺法旷) (Shi Citation2010, 273). In addition, his Buddhist paintings, such as Portrait of Vimala-kīrti (维摩诘图) and the LushanFootnote1 (庐山会图) attest to Gu’s deep influence by Buddhist thought and exhibit his high level of artistic skills. In Lidai Minghuaji, Zhang Yanyuan (Citation1997, 196) gave high praise to Gu’s artworks, stating that his innovative portrait of Vimala-kīrti had a thin and haggard appearance indicative of illness. Gu’s achievements in painting theories also manifest his assimilation of Buddhist thought. In his theoretical writings named On Painting (Hualun画论), Gu emphasises the importance of capturing the spirit beyond form, asserting that the painting is a means of expressing the inner “spirit” through “form” (Pan Citation1997, 266–267). Gu’s theory of “conveying spirit through vivid portrayal” (yi xing xie shen 以形写神) may have been influenced by śramaṇa Huiyuan’ (高僧慧远) Buddhist thought on the concept of form and spirit (Li and Liu Citation1999, 321).

Consequently, a scrutiny of Gu’s depiction of the goddess from a religious standpoint, notably through a Buddhist lens, could yield enhanced insights into the suppression of desire implied by the unidirectional interaction between Cao Zhi and the goddess. Moreover, it might facilitate a deeper understanding of the challenges and hardships faced by women within a feudal patriarchal society, while highlighting the stark disparities and tension between the “ideological language” and the “visual language” of patriarchal civilisation (Ye Citation2004, 4). In terms of image construction, the mural Vanquishing Mara (e.g. ) located on the southern wall of the front apse of Mogao Cave 254 during the Northern Wei period can provide a clear interpretation of Buddhist ideology for this pictorial paradigm. Similar subjects and compositions are also presented in the mural of Mogao Cave 263 in Northern Wei period and Mogao Cave 428 in Northern Zhou period. As one of the most famous themes in Buddhist story painting, Vanquishing Mara depicts the story of Shakyamuni defeating the demon Mara and achieving enlightenment, despite facing a troop of seductive witches and clawing soldiers under the command of Mara. The handscroll painting Nymph of the Luo River and the mural Vanquishing Mara share the following similarities:

Figure 4. Vanquishing Mara transformation story. Mural painting (Detail). Mogao Cave 254 south wall east side. Courtesy Digital Dunhuang of the Dunhuang Academy.

Firstly, both are visual translations of textual sources (the ode and Buddhist scriptureFootnote2) and contain similar narrative content concerning the interaction of men and women across social and spatial divides.

Secondly, both use the contrasting modes of movement (female) and stillness (male) to interpret gender relations and create visual conflicts. Compared to the symbolic and monotonous male figures, the artist creates more vivid depictions of female characters. The artist draws inspiration from the Buddhist scripture Lalitavistara Sūtra in shaping the image of seductive witches, Mara’s three daughters, which describes thirty-two “alluring postures and beguiling words” (Dharmarakṣa Citation1942, 519–533) employed by witches to tempt the Buddha and sway him from his path. In the mural, the witches convey desire and temptation through dynamic body language and active movements, such as revealing arms, leaning forward, and fluid eye movements. Similarly, Luo’s elegant demeanour also shows an active posture, such as slightly turning her head towards Cao Zhi and giving him an affectionate glance, or gently reaching out her hands to him, as if conveying her feelings. Compared to female images, the male roles, including the Sakyamuni and Cao Zhi, exhibit the characteristics of stable postures and forward-directed gaze. Specially, Cao Zhi is depicted several times interacting with the goddess, he is generally shown either with his arms supported by attendants or in a quiet, contemplative posture, exhibiting no active body language.

Lastly, both employ a combination of simplicity for the male and complexity for the female in pictorial strategies. In the mural, located to the lower left of the Buddha, the artist vividly portrays the witches in seductive and coquettish postures, dressed in Kučean-style trousers and displaying obvious feminine features. They are specifically adorned with flower crowns, wearing long skirts and short vests with circular patterns. With flirtatious gazes and charming looks, they attempt to dissolve Buddha Shakyamuni’s willpower. In contrast, the depiction of Buddha Shakyamuni is simple. He wears a robe, one hand naturally hangs down with the palm facing inward, and the index finger points to the ground with the Bhumyakramana mudra, while the other hand lightly tweaks the corner of the robe, sitting under the Bodhi tree. Similar visual language is used in the handscroll, where Gu focuses on portraying the flowing ribbons and wide sleeves of the goddess, utilising the vivid line drawing technique known as “silkworm spinning”, which add visual “rhythmic vitality”. By comparison, Gu’s portrayal of Cao Zhi is far less rich in dynamics and details than that of the goddess, using the technique of “iron wire sketch” (tie xian miao 铁线描) to draw plain facial expressions, and the depiction of clothing and styling is also simpler.

Therefore, the religious narrative provides a unique perspective for interpreting the visual metaphor of the one-sided interaction between Cao Zhi and the goddess of Luo. In Vanquishing Mara, Shakyamuni defeats the seduction of witches through his unwavering concentration, revealing that the illusions of desire are like “a vessel that contains foul poison, which will ultimately destroy itself” (Dharmarakṣa Citation1942, 519). The subjugation of desire embodies the asceticism championed by Buddhist thought during the Six Dynasties, and this philosophy posited that “when filled with desire, one cannot see the path” and “love and desire are the causes of delusion and ignorance” (Tang Citation2017, 74). According to Buddhist thought during Six Dynasties, abandoning desire, and resisting temptation are necessary means of spiritual cultivation and fundamental requirements for achieving enlightenment. Only by being “free from excessive desires, peaceful and inactive” (Fang Citation2012, 2), can one become omniscient and reach the highest realm of Buddhism. Especially in the popular Buddhist teachings influenced by the “five hindrances or obstructions of women” (Anālayo Citation2009, 136–190) in Hinayana Buddhism, females are symbols of “minor blessings” (Dharma-nandi Citation1999, 669), and only by “becoming a man after dropping a woman’s body” can one become a Buddha among all beings in the Dharma realm at once (Wang and Li Citation1997, 206). In this belief system, the beauty of goddesses is no longer merely a pure aesthetic experience or emotional response, but rather an “ethical test”, an “original sin”, and a “hindrance” to the religious aspirations of people in the Six Dynasties, who sought to escape their painful reality and reach the otherworldly realm through religious transformation (e.g. achieving Buddhahood, or entering the Elysium). Thus, in the aesthetic perspective influenced by asceticism, the elements of “desire”, “love”, and “beauty” often suggest and convey significant existential crises and moral challenges. Both images depict a way of separating men and women through the depiction of male-female exchanges as unaffectionate. In Vanquishing Mara, Shakyamuni defeats the demon’s temptation to obtain enlightenment; while in Gu’s painting, Cao Zhi avoids the possibility of being trapped by the nymph’s deceit. In a male-dominated society of the Six Dynasties, women could only adhere to the ascetic practice of self-denial and sacrifice, as well as act cautiously to gain the mercy of men (Zhang Hua Citation1986, 167). In the painting, the figure of the goddess riding on a cloud chariot driven by six dragons, not only fails to embody the concept of a truly liberated new woman, but also has to relinquish her rightful happiness as a consequence of the “original sin” of being a beauty.

Fusing landscape and feminine space: constructing “Heterotopia”

A typical and enclosed spatial composition can be observed in pictorial art during the Han Dynasty, wherein female figures are confined to interior spaces. For instance, in the pictorial stone whose theme related lienü (virtuous women) located on the south wall of the Wu Liang Shrine in Jiaxiang, Shandong Province, Chaste Jiang (贞姜, the queen of King Zhao of Chu) and the King’s envoy are positioned in separate indoor and outdoor spaces, engaging in a dialogue across space to convey Confucian morality: upholding female virtues and emphasising loyalty and righteousness (Wu Citation1989, 176). Meanwhile, the composition possesses a two-dimensional spatial feature characterised by modularisation, and “classical tradition” and silhouette-style (Wu Citation2019, 69–71). However, the painting Nymph of the Luo River breaks through such spatial restrictions in terms of composition. As the vivacious goddess walks through the pathways of the verdant mountains and rivers, it flawlessly captures the mythical ambiance and fantastical beauty of the ode. Wu (2009, 96) states Gu has created an innovative space that combines the beauty of female figures and nature, with desire as its main theme, and it is the fantasy world of the goddess. From the perspective of composition, Chen (Citation2012, 118) affirms that the painting’s semi-circular spatial design, which uses mountains and trees as spatial dividers to delineate the scene, creates a limited sense of spatial depth and aesthetic interest in movement. Based on the above, this paper proposes that, compared to the completely imaginary “Utopia”—a fantasy space that is surreal, beautiful, and exists in the otherworldly realm—the painting while seemingly focusing on romantic love, constructs a “Heterotopia”. This does not alter the aesthetic value of the artist’s representation of the power and order of patriarchal society through the language of imagery.

Specifically, the nymph in the painting is still confined to a semi-closed space surrounded by immortal mountains, sacred rivers, and divine trees, and she cannot enter the external, natural, and public space from which traditional women were deprived in the patriarchal social order. Michael Foucault’s concept of “heterotopia” provides a theoretical framework that can be applied to the interpretation of the composition. In summarising the characteristics of heterotopia, Foucault (Citation1994, 752–762) points out that it not only creates an illusory space but also exposes and reflects the real world, thus forming a supplement to the existing world. Therefore, this paper tends to interpret the space around the “immortal mountains and divine rivers” surrounding the goddess as a third space that combines fantasy and reality, following the “heterotopia” model. It includes dual image elements of reality and fantasy, reflecting not only the observation and reflection of the real space, but also the re-creation of the mystical realm and imaginary space. On the one hand, the third space in the painting showcases a subversion of the power order. Women, who were oppressed in the patriarchal and male-dominated society, seem to achieve a transcendent liberation of both their minds (pursuit of love) and bodies (roaming in the dreamlike space) in the heterogeneous space. They enter a diverse society that is free from the “hierarchical system,” as can be seen from the juxtaposed pictorial relationships between characters such as Fengyi, Nüwa, Pingyi, Chuanhou (e.g. ). On the other hand, Gu Kaizhi employs a hidden approach by endowing the female figures with a mystical space of “immortal mountains and divine rivers”, thereby concealing the true form of social power. This approach replaces physical isolation with an ostensibly free ideological confinement, thereby introducing a new metaphor of confinement in iconography.

Figure 5. Gu Kaizhi. Nymph of the Luo River. Handscroll (Detail). Ink and colours on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing.

Primarily, the scroll painting uses the timeline of an interaction between the goddess and the mortal prince as its narrative framework, vividly depicting the content of the ode. A variety of pictorial elements presented simultaneously in the painting establish a form of synthetic narrative and negate the necessity for spatial continuity. This type of narrative in pictorial art is strikingly similar to the one termed “synoptic” (literally, “combining views”) described by Fullerton in Greek art, wherein the scene does not “depict one stage in the story but seems to combine elements of different stages in order to suggest a sequence of events and passage of time” (Citation2000, 98). Consequently, this painting reinterprets the narrative element of “time”, achieving a temporal expression within the inherently “spatial art” (Lessing Citation1979, 84; Long Citation2015, 427; Long Citation2019, 17–22). In other words, Gu not only blends relatively independent plots, allowing visual elements on different stages to engage in a dialogue across space, but also uses a visual form of space division to extend and translate social morals and order, such as the Confucian concept of Li (礼), including the principle of “unmarried men and women should not touch each other” (Mencius Citation1970, 17). In Nymph of Luo River (collected in Beijing Palace Museum), there is no intersection of time and space between the goddess and Cao Zhi. In most of the scene there are trees, rocks, and mountains serving as a (not entirely enclosed) spatial separation between them. The goddess is always floating on the misty river or enveloped by clouds, while Cao Zhi stands on the land, further emphasising the visual metaphor of the contrast between male and female, as well as reality and divinity. Mountains, rocks, trees, and rivers, while forming a part of the natural landscape, also serve as boundaries that divide the space. In the “falling out and hesitation” section, where the goddess and Cao Zhi are within close proximity (e.g. Figure 9), it is the only section in the entire handscroll where no object serves as an obstacle between them. She steps onto the land, seemingly entering Cao’s space of reality, but the sprawling and fluttering ribbons behind her imply that she is still in a different space, a “mysterious realm”. In this way, Gu not only shapes the image of an ethereal goddess, but also avoids the possibility of her entering the human/public space, thereby effectively conveying the visual suggestion of her physical constraint.

Figure 6. Gu Kaizhi. Nymph of the Luo River. Handscroll (Detail). Ink and colours on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing.

Moreover, the painting achieves a sense of “synchronicity” through the juxtaposition of images, thus unifying the space in which the goddess resides with natural elements like mountains and rivers. Particularly, the ingenious arrangement of mountains in the painting ultimately results in a visual and formal continuity. However, numerous “fantastical elements outside the mundane world” are employed in the depiction, resulting in the figure of the goddess being enclosed within the mysterious and mystical world of the immortals in the visual sense. In the section of “encounter”, the upright ginkgo tree divides the picture into a world of “willows, rocks, and soil slopes” that constitutes human existence, and an otherworldly fantasy land filled with elements such as the “immortal mountains”, the “divine rivers” and the “roaming dragon” etc. Previous studies have suggested that the spatial separation signify a sense of despair or disillusionment of Cao Zhi resulting from the failed quest for immortality, shattered illusions, and lost love, and these interpretations are predominantly based on the male perspective of Cao Zhi. Under this perspective, the goddess remains an objectified “the other” that is observed, serving as a symbolic representation of an unattainable and unreachable “enchanted land”. The article argues that the “U”-shaped compositional technique intricately alleviates the potential monotony in the visual experience that “ideographic motifs” (Fong Citation1971, 282–292) of landscape painting might bring. While simultaneously echoing the ode—“The ways of goddess and men are different indeed” (Cao Citation1986, 257)—the painting illustrates the dual constraints on the female body (unable to enter the worldly/public space) and psyche (unable to attain love with Cao Zhi). In the “departure” section, this visual dilemma is further emphasised: the goddess of Luo sits within the cloud chariot pulled by six dragons, surrounded by water spirits (such as Wenyu and Jingni). The encircling caused by mythological images stands in stark contrast to the goddess’s melancholic gaze, creating a dramatic conflict and powerful visual impact. The oppression, confinement, and constraints on women in patriarchal society and cultural order are once again interpreted by the painter in a concealed manner that is idealised and fantastical. Therefore, Gu provide a “moral” and “humanizing” representation of the marginalised and vulnerable status of women in public space.

Conclusion

Compared to traditional intertextual studies of literature and imagery in Nymph of the Luo River, spatial analysis provides a new approach to the study of female figure in Chinese painting. In the painting, Gu Kaizhi uses an innovative pictorial narrative that has a significant meaning in breaking through the aesthetic hegemony of its era. He portrays the gorgeous and elegant goddess, endowing her image with a degree of transcendence and rebelliousness compared to the traditional female images in the pictorial art of Qin and Han period. However, the close association of the goddess’s image with nature and ecology did not lead to a complete breakthrough in the didactic aim of “disciplining” women in its depiction. This article argues that if we consider Cao Zhi’s ode as an open text, then the desire it metaphorically expresses to conquer nature and women—that is, the longing to escape the sorrowful life of the chaotic world and enter an idealised realm, along with a yearning for the world of immortals and the goddess—is intentionally suppressed in the painter’s work. Gu transformed the content and visual language into a didactic power of “using literature to convey morals” in a rational manner. Gu’s interpretation of “abstinence” and “romance” thus somewhat contradicts the content of Cao’s text. Furthermore, the female figure remains confined within a “heterotopia” space filled with spirits and mystery creatures; and the contradiction and juxtaposition caused by the spatiotemporal factors in the painting skilfully conceals the sense of enclosure. Gu merges and superimposes the representative fairyland space with the reality space characterised by “worldliness”. He establishes a didactic narrative framework through a form of “dialogue across space” both between text and imagery, and within the imagery itself, thus enabling the painting to represent the hierarchical order through visual metaphor. In summary, although the handscroll painting seemingly embodies pictorial characteristics of “human-centeredness” and “male-dominated cultural hegemony” which ecofeminists seek to transcend by saving nature and liberating women, the complex cultural context of the era in China, coupled with Gu’s rich artistic language, allows it to convey distinctly different cultural metaphors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Scholars such as Yu Jianhua (Citation1964, 102), Okamura Shigem (Citation1974, 337) believe that the painting Lushan is related to Buddhist gatherings attended by Huiyuan in the White Lotus Society or in Lushan.

2 The story is recorded in early Buddhist scripture like Pali Suttanipāta and the Padhānasutta etc. (Stache-Rosen Citation1975, 5–19; Windisch Citation1985, 30–56).

References

- Anālayo. 2009. “The Bahudhātuka-sutta and Its Parallels on Women’s Inabilities.” Journal of Buddhist Ethics 16: 136–190. http://www.buddhistethics.org/.

- Bian, Xiangyang, and Zhou Fang. 2018. “A Study on the Origin and Evolution of Shape and Structure of ‘Gui-Yi’ in Ancient China.” Asian Social Science 14 (08): 145–152. doi:10.5539/ass.v14n8p145.

- Cao, Zhi. 1986. “Luoshen Fu” [Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River]. In Wen Xuan 19 [Selected Literary Works Vol 19], edited by Xiao Tong, 895–903. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing.

- Cao, Zhi. 2002. “Hua Zan Xu” [A Preface of Eulogies to Portraits]. In Han Wei Lü Chao Shu Hua Lun, edited by Pan Yungao, 257. Changsha: Hunan Fine Art.

- Chen, Shouxiang. 2000. Wei Jin Nan Bei Chao Hui Hua Shi [History of Painting of the Wei, Jin, the Northern and Southern Dynasties]. Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing.

- Chen, Pochen. 2012. The Goddess of the Lo River: A Study of Early Chinese Narrative Handscroll. Hang Zhou: Zhejiang University Press.

- Chen, Changhong. 2016. Images of Exemplary Women in the Han, Wei, and the Six Dynasties. Beijing: Science Press.

- Dai, Yan. 2021. Luo Shen Fu Jiu Zhang [Nine Chapters of Ode to the Goddess of Luo Shen Fu]. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

- Dharmarakṣa. 1942. “Lalitavistara Sūtra 6.” In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, Vol. 3, edited by Takakusu Junjiro, 519–533. Tokyo: Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai.

- Dharma-nandi. 1999. Ekottarika Āgama. Beijing: Religion and Culture Press.

- Fang, Litian. 1982. Wei Jin Nanbeichao Fojiao Luncong [A Collection of Buddhist Discourses During the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Fang, Litian. 2012. Fang Litian Wen Ji 2: Wei Jin Nanbeichao Fojiao [Collected Papers of Fang Litian Vol 2: Buddhism in the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press.

- Fong, W. C. 1971. “How to Understand Chinese Painting.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115 (4): 282–292. https://www.jstor.org/stable/986090.

- Foucault, M. 1994. “Des espaces autres.” In Dits et Écrits 1954–1988, edited by Daniel Defert, 752–762. Parris: Gallimard.

- Fullerton, M. 2000. Greek Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Genette, G. 1990. Narrative Discourse. Translated by Wang Wenrong. Beijing: China Social Sciences.

- Guṇabhadra. n.d. “Saṃyukta Āgama 36.” In Banrekiban daizokyo 78, vol. 2, 1–30. https://dzkimgs.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/utlib_kakouzou/078_2/0030.

- Guo, Ruoxu. 2000. “Lun Funü Xingxiang” [On the Portrayal of Women]. In Tu Hua Jianwenzhi: Hua Ji [Record of Experiences in Painting], edited by Pan Yungao, 40. Changsha: Hunan Fine Art.

- Hall, J. 1995. Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art. Denver: Westview.

- Hang, Chunxiao, and Ying Jiang. 2003. “Theoretical Reflection on the Research of Modern Women’s Art: On the Women’s Images and Social Sex Structure.” Hundred Schools in Art 5 (1): 105–107.

- Jin, Weinuo. 2014. History of Chinese Art from Wei to T’ang Dynasty. Beijing: China Renmin University Press.

- Lessing, G. E. 1979. Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Translated by Zhu Guangqian. Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House.

- Li, Shaowei. 2020. “Qiantan Luoshenfu Zhong De Wenyu Xingxiang” [Brief Introduction to the Image of the Wenyu in the Nymph of Luo River]. Beauty and Times 9: 56–59. doi:10.16129/j.cnki.mysds.2020.09.020.

- Li, Zehou, and Jigang Liu. 1999. History of Chinese Esthetics: Wei, Jin, The Northern and Southern Dynasties. Hefei: Anhui Literature and Art Publishing.

- Long, Diyong. 2015. A Study of Spatial Narrative. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

- Long, Diyong. 2019. “Time and Media: On the Difference Between Literary Narrative and Pictorial Narrative.” Meishu 11: 17–22. doi:10.13864/j.cnki.cn11-1311/j.005624.

- Lü, Zhirong. 2015. “Haotan Donghan Bihua Mu Shengtian Tu Kaoshi” [Study on Murals from the Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Excavated in Haotan]. Cultural Relics of Central China 176 (2): 86–90.

- Luo, Zongqiang. 2005. Xuanxue yu Weijin Shiren Xintai [The Study of Neo-Daoist and the Mentality of the Wei-Jin Literati]. Tianjin: Tianjin Education.

- Mencius. 1970. Mencius. Translated by D. C. Lau. London: Penguin.

- Meng, Xianping. 2010. “Tree, Space, and Schema: An Attempt at a Case Study of the Nymph of the Luo River.” Arts Exploration 24 (3): 13–18.

- Mulvey, L. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16 (3): 6–18. doi:10.1093/screen/16.3.6.

- Okamura, Shigem, ed. 1974. Lidai Minghuaji [Record of Famous Painters of All the Dynasties]. Tokyo: Perikansha.

- Pan, Yungao, ed. 1997. Han Wei Lü Chao Shu Hua Lun [Theories of Calligraphy and Painting during the Han, Wei, and Six Dynasties]. Changsha: Hunan Fine Art.

- Shen, Congwen. 2017. Zhongguo Gudai Fushi Yanjiu [Research on Ancient Chinese Costumes]. Beijing: Commercial.

- Shi, Huijiao. 2010. Gaoseng Zhuan [Eminent Monk Biography]. Translated by Zhu Hengfu and Wang Xuejun. Xi’an: Shaanxi People Publishing.

- Shih, Shouchien. 2011. “The Nymph of the Luo River: A Tradition’s Shaping and Development.” In Gu Kaizhi Yanjiu Wenxuan [Selected Works on Gu Kaizhi’s Research], edited by Zou Qingquan, 96–123. Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian.

- Stache-Rosen, Valentina. 1975. “The Temptation of the Buddha.” Bulletin of Tibetology 12 (1): 5–19. http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/242992.

- Tang, Lan. 1961. “Lun Gu Kaizhi De Huihua” [A Study on Gu Kaizhi’s Paintings]. Wenwu 1: 7–12.

- Tang, Hou. 1993. “Ancient and Modern Mirror of Paintings.” In Complete Collected Writings on Chinese Calligraphy and Painting, Vol. 2, edited by Lu Fusheng, 894–903. Shanghai: Shanghai Fine Arts.

- Tang, Yongtong. 2017. Hanwei Liangjinnanbeichao Fojiao Shi [History of Buddhism in Han Wei Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties]. Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Wang, Yun. 2009. “Catalogue of Calligraphy and Painting.” In Complete Collected Writings on Chinese Calligraphy and Painting, Vol. 3, edited by Lu Fusheng, 130–135. Shanghai: Shanghai Fine Arts.

- Wang, Zongying. 2010. Zhongguo Shi Nü Hua Yishu Shi [The Art History of Chinese Female Figures Paintings]. Nanjing: Southeast University Press.

- Wang, Su, and Fang Li. 1997. Dunhuang Documents from the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, in Chronological Order. Taipei: Xin wenfeng.

- Wei, Zheng. 2011. “Examining Archaeological Data to Determine the Creation Period of Gu Kaizhi’s Painting the Nymph of the Luo River.” In Gu Kaizhi Yanjiu Wenxuan [Selected Works on Gu Kaizhi’s Research], edited by Zou Qingquan, 85–95. Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian.

- Windisch, E. 1985. Mara and Buddha. Leipzig: S.Hirzel.

- Wu, Hung. 1984. “A Sanpan Shan Chariot Ornament and the Xiangrui Design in Western Han Art.” Archives of Asian Art 37: 38–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20111143.

- Wu, Hung. 1989. The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art. Stanford: Standford University Press.

- Wu, Hung. 2019. Feminine Space in Chinese Painting. Beijing: SDX Joint.

- Xu, Jie. 2020. “Creation and Criticism of Luo Shen Fu and Painting.” Journal of Anhui Normal University (Human & Social Science) 48 (4): 32–39. doi:10.14182/j.cnki.j.anu.2020.04.005.

- Ye, Shuxian. 1997. The Nmyph of Gaotang and Venus: Themes of Love and Beauty in Chinese and Western Cultures. Beijing: China Social Science.

- Ye, Shuxian. 2004. The Goddess with a Thousand Faces. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

- Ye, Lang, and Zhiliang. Zhu. 2015. Zhong Guo Yi Shu Pi Ping Tong shi [A General History of Chinese Art Criticism]. Heifei: Anhui Education.

- Yu, Jianhua, ed. 1964. Lidai Minghuaji [Record of Famous Painters of All the Dynasties]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts.

- Yu, Dunkang. 2016. Weijin Xuanxue Shi [History of Metaphysics in the Wei and Jin Dynasties]. Beijing: Peking University.

- Yuan, Ke. 2014. Shan Hai Jing School Notes. Beijing: Beijing United.

- Zeng, Zirong. 2017. Gu Kaizhi He Ta De Luo Shen Fu Tu [Gu Kaizhi and His Painting the Nymph of the Luo River]. Beijing: CITIC.

- Zhang, Hua. 1986. “Nüshizhen” [Admonitions to the Instructress]. In Wen Xuan, Vol. 46, edited by Xiao Tong, 2042–2045. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics.

- Zhang, Yanyuan. 1997. “Lidai Minghuaji” [Record of Famous Painters of All the Dynasties]. In Theories of Painting in T’ang and Five Dynasties Period, edited by Pan Yungao, 137–198. Changsha: Hunan Fine Art.

- Zhipan. 2019. Zhipan’s Account of the History of Buddhism in China: Fozu Tongji, Juan 34–38 from the Times of the Buddha to the Nanbeichao Era. Translated by Thomas Jülch. Leiden: Brill.