ABSTRACT

This paper explores the emerging labour regimes and the consequences for agricultural commercialisation across multiple land-use types in post land reform Zimbabwe. The livelihoods of farmworkers, including those still resident in former labour compounds, are explored. The paper examines patterns of employment, land access, crop farming, asset ownership and off-farm activities, highlighting the diversification of livelihoods. The old pattern of wage-employed, permanent farmworkers is increasingly rare, as autonomous, flexible combinations of wage work, farming and a range of entrepreneurial and informal activities emerge. The paper thus engages with the wider debate about the changing nature of ‘work' and ‘employment', alongside discussions about the class implications of ‘working people' and ‘fractured classes of labour’ in transforming agrarian economies. Without a captive, resident workforce, commercial agriculture must mobilise labour in new ways, as the farm work and workers have been refashioned in the new agrarian setting.

1. Introduction

The radical transformation of agrarian relations following Zimbabwe’s fast-track land reform programme (FTLRP) resulted in a new labour regime. The FTLRP transferred around 10 million hectares of land, formerly managed by around 4,500 mostly white farmers to around 145,000 smallholders and 23,000 medium-scale farmers (Scoones et al. Citation2010; Moyo Citation2011), reconfiguring patterns of agricultural commercialisation.

Since the settler colonial era, a dualistic agricultural system existed, with large-scale commercial farms sourcing labour from ‘the reserves’ (now communal areas) and nearby countries. Labour was both resident (living in labour compounds) and temporary, with seasonal variations depending on the production system (Rutherford Citation2001). The new agrarian structure has generated diverse forms of wage labour, linked to new livelihood patterns (Moyo Citation2011; Chambati Citation2013, Citation2017; Scoones et al. Citation2018a). A much greater variety of labour provisioning arrangements is seen, and many former farmworkers are now taking up farming, besides selling labour. This paper explores the emergence of this new labour regime following land reform in Mvurwi area, and explores the implications for livelihoods, patterns of social differentiation and the commercialisation of agriculture.

Following the FTLRP, with the invasion of large-scale commercial farms (LSCF), farmworkers and their families were displaced, and mostly excluded from land allocations, as they were seen as friendly to their employers and the opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) (Helliker and Bhatasara Citation2018). Consequently, farmworkers left the area, returning to communal area homes or moving to other parts of the country, while others were displaced in situ (Magaramombe Citation2010), resulting in many maintaining residency in the farm compounds, but now deprived of social services and employment.

In the dualistic system of the past, farm labour was either wage work on LSCFs, with farm wages being the only source of income, or casual, informal piecework labour in the communal areas. Today, livelihoods are more diverse, as people combine farm work with off-farm labour, with complex class positions (Moyo and Yeros Citation2005). Diversified livelihoods are often linked to a pattern of informalisation associated with extreme forms of precarity and ‘footloose’ relations (Breman Citation2010; Ferguson and Li Citation2018), even if with more autonomy and flexibility than the standard patterns of proletarian wage work (Tabata Citation1954; Mafeje Citation1985). Understanding the emergent class dynamics among farm labour is therefore crucial for a more comprehensive understanding of the prospects for commercial agriculture following land reform, requiring a disaggregated look at labour regimes.

The labour control of the past has been replaced by ‘residential autonomy’, where workers can choose to work or not work at the farm where they reside (Magaramombe Citation2010), often leading to labour shortages. This presents workers with strong bargaining power for better wages and the scope for income diversification. For Chambati (Citation2017), shifts in farmworker relations are linked to the new agrarian structure in which increased land access by newly settled farmers expanded labour demand.

This dynamic following the FTLRP remains poorly understood. Some argue that new labour arrangements are just as poorly remunerated and exploitative as before (Hartnack Citation2016; Rutherford Citation2017; Pilossof Citation2018; Chiweshe and Chabata Citation2019) and cases of physical violence, racism and long working hours, which characterised the pre-2000 era (Amanor-Wilks Citation1995; Tandon Citation2001), persist. Others argue that autonomy and flexibility have now increased, and greater freedom positions workers in good bargaining positions (Moyo Citation2007; Chambati Citation2017). Yet, this polarised debate fails to examine the patterns of differentiation among workers on farms across different land-use types. This article therefore aims to fill this gap, exploring how a more differentiated understanding of worker livelihoods helps us understand the post-FTLRP agrarian transition. The article therefore asks the question: has land reform produced a classic agrarian transition, with increased proletarianisation, intensification and consolidation of farms, or is a more variegated, non-linear set of changes observed, with diverse labour regimes?

In many discussions of agrarian transition, a linear, evolutionary change is posited – either towards increasing proletarianisation, as wage work is taken up with increasingly efficient commercial farms (Byres Citation1977), or towards an exit from wage work towards a more agrarian livelihood (Jayne, Chamberlin, and Benfica Citation2018). Many explanations for such pathways tend to focus on relative factor prices and economic incentives, limiting the scope of the analysis (Berry Citation1993). In fact, a range of conditions may affect agrarian transitions, from environmental and land-use factors to social and political relations, eluding a linear, evolutionary trajectory. For instance, Moyo and Yeros (Citation2005) argue that the accompanying primitive accumulation generates differentiation and so diverse pathways of agrarian change, while Helliker and Bhatasara (Citation2018) identify locally-based, autonomous processes that emerge to shape agrarian change. Chiweshe and Chabata (Citation2019) similarly identify how the agency of local actors, including farmworkers, influences how agrarian transitions play out.

This article therefore engages with wider debates about the role of labour within changing agrarian settings and contemporary capitalist economies (Chhachhi Citation2014; Harriss-White Citation2003). Shivji’s (Citation2017) conceptualisation of ‘working people’ – cutting across categories of producer and worker – is useful here, focusing on the surplus extraction by capital through the maximising of labour exploitation in diversified and stratified economic settings. For Bernstein (Citation2006, Citation2007) such people are the diverse and fragmented ‘classes of labour’ making a living in multiple ways, not easily defined in classic occupational, locational or class terms. Operating in precarious spaces, often informal and sometimes illegal, livelihood options are limited and the possibilities for expanded reproduction and accumulation from below are constrained. ‘Working people’, differentiated by age and gender, therefore, must combine occasional wage employment, informal work and some engagement in agricultural production. Such informal work may equally act as an effective subsidy to capital as social reproduction is squeezed (Shivji Citation2009). As livelihoods diversify, changing divisions of labour emerge, with class, gender and age implications (O’Laughlin Citation1996). Processes of fragmentation across classes of labour equally result in the restructuring of patterns of daily and cross-generational social reproduction, with implications for production and wider social relations (Cousins et al. Citation2018). Understanding these intersecting processes of social differentiation and the links to diverse forms of work in a changing agrarian setting thus helps us understand complex agrarian labour regimes and their location in wider capitalist relations and politics (Jha Citation2021). As others have observed, contemporary labour regimes do not fit neat categories used in the past of standard ‘jobs’ and fixed ‘wage-employment’ (Ferguson and Li Citation2018), and so require a new analysis, to which this article contributes for the post-land reform setting in Zimbabwe.

Across different land-use settings in one part of Zimbabwe, this paper therefore explores what the post-land reform agrarian transition looks like in practice, providing insights into the differentiated character of new labour regimes. The rest of this article is structured as follows. First, we offer an overview of the study area and the methods used. The next section offers a brief historical overview of agricultural labour relations in Zimbabwe to set the study in context. The following section conceptualises shifting agrarian labour relations, while the next explores changes in access to land, production and marketing of agricultural commodities and the changing the characteristics of farmworkers. The article then discusses farmworker productivity, incomes sources, accumulation trajectories and changes in their social security after 2000. Finally, before concluding, the paper highlights emerging farmworker types, linked to patterns of accumulation and class formation.

2. Methods: understanding the post-land reform labour regime

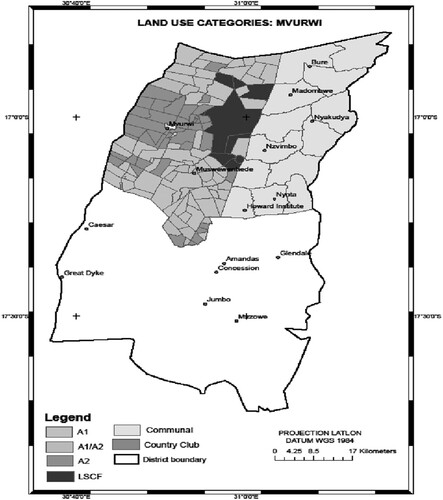

The Mvurwi/Chiweshe area in Mazowe district has a long history of tobacco production, dating back to the 1900s when the earliest settler farmers shifted to agriculture from mining. Tobacco, maize and horticulture are the core commercial crops. The district is located 100 km north-west of Harare. The area consists of fertile soils and receives an average of 800 mm of rainfall per annum. With good market connections, particularly to Harare, the area is regarded as a high potential, ‘hot spot’ area for agricultural commercialisation (Shonhe Citation2018; Scoones et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020) (see ).

After the FTLRP, different land-use categories now exist. These range from remaining LSCFs; medium-scale commercial farms (designated A2 farms), sometimes with joint-venture (JV) arrangements with external investors; smallholder farms (designated A1) and existing communal areas (CAs). Also, there are former labour compounds in the remaining LSCF, A2, A2-JVs and A1 farms.

This paper is based on a survey of 358 workers operating in the four core land-use categories (LSCF, A2, A1 and CA), plus workers from JVs operating on A2 farms and compounds in A1 areas. Workers are defined as those regularly selling labour and working on others’ farms, earning cash or in-kind resources for a significant part of their livelihood. In each of the six sites, we drew a household sample randomly, aiming for around 50 cases each. In the LSCF (N = 50) and A2 (N = 45)/A2-JV (N = 49) cases, workers were more classic wage-labourers, resident on the farm. In the A1 (N = 71) and CA (N = 51) cases, the sample focused on those households that were selling labour, but also had plots locally. In the case of those resident in compounds (N = 92), these were former farmworkers, but now were engaged in a variety of activities, including selling labour.

The aim was to gain a picture of the full variety of farm labour in the post-FTLRP setting across land uses, as well as explore some of the interactions between them. The availability of data on labour is notoriously poor (Oya Citation2013; Oya and Pontara Citation2015), but our study combined the sample survey with 30 qualitative interviews across sites. Key informant interviews (with former farm managers, supervisors and government officials) additionally provided detailed biographical insights, examining how labour regimes have changed over time.

We explored patterns of accumulation, linked to class formation, and how this varies across sites, and by gender, age and other dimensions of social difference. Overall, we ask: how is labour of different types deployed in agriculture, who are the new ‘farmworkers’ and what are the implications both for livelihoods of those selling labour and the possibilities for commercial agriculture?

3. A brief historical overview of farm labour in Zimbabwe

Settler colonialism in Zimbabwe was founded on the subjugation of indigenous peoples, and their displacement from productive land and their means of livelihoods. After settlement on the farms from the 1890s, but especially from the 1930s, and again following the Second World War (Mbanga Citation1991; Rubert Citation1998), the demand for farm labour increased (Arrighi Citation1970; Dunlop Citation1971), mainly for tobacco production (Rubert Citation1998). The reluctance of Shona indigenous people to work on the LSCFs, resulted in the reliance on workers from Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique (Dunlop Citation1971; Clarke Citation1973).

To force the indigenous population to work on the farms, markets were manipulated and numerous levies were imposed (Palmer Citation1977; Hodder-Williams Citation1983; Phimister and Pilossof Citation2017), creating African ‘native (labour) reserves’ and proletarianising Africans by the 1950s (Arrighi Citation1970) under a system of ‘domestic government’ (Rutherford Citation2001). Moreover, farmworkers were dependent on farm owners for all services (Sachikonye Citation2003), limiting their ability to engage in other income-earning activities. Throughout the colonial period, wages remained low, barely adequate to cover subsistence costs (Loewenson Citation1992).

Following Independence in 1980, farmworkers increasingly agitated for better working conditions and higher wages, including the removal of harsh farm managers (Sachikonye Citation1986, Citation1997; Rutherford Citation2001; Hartnack Citation2016). However, the national reconciliation policy meant that the government remained sympathetic to LSCF farmers (Sachikonye Citation1986; Rutherford Citation2001). Moreover, from the 1990s, the ‘structural adjustment’ ensured that the government had inadequate capacity to monitor and enforce policy reforms (Amanor-Wilks Citation1995; Kanyenze Citation2001).

The agricultural sector’s contribution to employment rose from 879 workers in 1904 to 83,000 by 1936 and 220,162 in 1951 and 314,965 by 2002 (Pilossof Citation2014, 346; also see Phimister and Pilossof Citation2017, 220). By the late 1990s, there were around 300,000 workers on large-scale farms; although only half of them were permanent workers and the rest were seasonal, temporary workers, often women, moving to farms from communal areas (CSO Citation2001). By 2000, fewer were observed to be of ‘foreign’ origin (FCTZ Citation2000; Chambati Citation2017), down from 60% in 1956 (Clarke Citation1977), reflecting the increased dependence on the local population for the workforce. Following the FTLRP, around 70,000 farmworker households continued to have employment on the remaining farms and estates, while about 25,000 were displaced in situ, living on compounds but initially without work (Scoones et al. Citation2018a, 811). While the figures are approximate – and much disputed – the major reconfiguration of labour, as well as land, from 2000 is clear, although the implications are poorly understood.

Following land reform, there were no longer expectations of provision of services for workers (Magaramombe Citation2010), and former workers had to find labour or land wherever they could, including participation in an informalising economy (Sachikonye Citation2007; Luebker Citation2008; Raftopoulos Citation2009). Former farmworkers now combined farm labour and farming with off-farm activities, such as artisanal mining, informal vending, beer-brewing, selling firewood, fishing and hunting, as well as depending on remittances from family members outside the country (Magaramombe Citation2010; Scoones et al. Citation2018a).

4. Who are the new farmworkers?

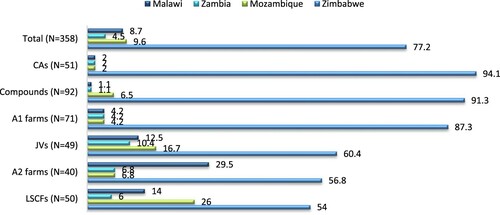

Who are the new farmworkers? As discussed earlier, we sampled across six different land-use categories. In terms of origins, overall, most identified as Zimbabweans (77.2%), while others identified as from Mozambique (9.6%), Zambia (4.5%) and Malawi (8.7%) (). So-called ‘foreign’ workers are concentrated in the LSCFs (46%), A2 farms (43.2%) and A2-JV farms (39.6%), and are associated with permanent jobs. Contrary to the findings of Chiweshe and Chabata (Citation2019), 91.3% of the farmworkers dwelling in the compounds self-define as of Zimbabwean origins.

Across our sample, permanent employment represents about a third of all cases (33.6%) (). The LSCF has the highest proportion of permanent workers (35.9%), compared to CAs (16.2%) and A1 farms (15.4%). Men dominate the permanent workforce on A1 (94.4%) and A2 (90.9%) farms, while CA households employ the most women (47.4%), paying them the highest wages of US$104 per month. Men from the CAs are frequently engaged in rural-urban migration and more recently movement across borders in search of employment, leaving women behind to till the land and look after the family. Due to limited means to support social reproduction, women often end up doing maricho (temporary labour) to support their families.Footnote1 The age structure of the working population is changing with workers aged between 30–40 years representing nearly half of the permanent workforce, as older workers, especially in the LSCFs, are being replaced by younger people.

Table 1. Gender and wages of farmworkers per sector and employment type.

Seasonal work is pursued by 14.4% of farmworkers and is most common among men in the A1 farms (42%) and in the CAs (30%), even though their monthly wages remain relatively low. Contrary to Chambati’s (Citation2017) findings in Goromonzi and Kwekwe districts, contract and seasonal work were the least common among farmworkers, at 23.6% and 14.4%, respectively, across our sample. However, most compound workers are employed as temporary contract workers (74.4%), while relatively few (16.2%) are employed on a permanent basis (). One farmworkerFootnote2 living in a compound in a LSCF estate described his livelihood and preference for temporary work:

I was born in 1983 and grew up in Mount Darwin and attended school there until I finished Grade 7. I then went to Marry Mount to work before coming to Forrester Estates B. As workers, we didn’t have enough connections to get farms. I never subscribed to jambanja (land invasions). I thought maybe it won’t be successful. When I saw others successful, I just continued working. I have a garden where I grow vegetables and maize for consumption. I don’t sell because my harvest is small. As a family, it’s enough for us. We are a family of five. I aspire to have my own farm and grow crops like maize, tobacco and soya beans. Even though I am staying here in Forrester Estates B, I prefer to work for A1 and A2 farmers because they pay soon after the work. Piecework is paying better because we work for a short time and get money which is more than my salary.

I settled here in 2010. I came here looking for farmland, but was unlucky. I now rent farms to grow my crops, staying in the compound. I don’t pay anything to the farm owner, but I assist him with piecework. Since 2010, I have been renting one hectare. I routinely change the people from whom I rent because often plot holders take their land back after noticing our good yields. I am using the land for tobacco and maize production. I am contracted to ZLT, and they support me with eight bags of fertilisers, five grams of seeds and sprays. In return, I sell to them. To augment this income, I do piecework jobs whenever I can, but make sure I prioritise my own farm.

In terms of patterns of employment by gender, there are generally more men (72.5%) than women (27.5%) employed (). Women are more commonly employed as temporary (32.3%) and contract labourers (31.7%) as opposed to permanent (26.5%) and seasonal (14%) arrangements. Far more men are also employed in decision-making positions, as well as in skilled roles such as tractor drivers, foremen and workshop and management positions. A female farmworkerFootnote4 on a A2-JV farm noted:

I have been working on this farm for eight years. Before this I was staying in the compound doing piece jobs for A1 and A2 farmers. I started working here in 2012 when the Chinese came to the farm. However, I am still considered a temporary worker. I’m employed every year to do planting, weeding, harvesting and grading of tobacco. My husband and my son were lucky to be employed as permanent workers. Most of the women are employed as temporary or seasonal workers. At the same time, most of us women did not get land during ‘jambanja’. I have a small piece of land where I grow maize and sweet potatoes to feed my family. I feel like, as women, we are always forgotten.

5. Workers, land access and agricultural production

Across all categories, a significant number of the farmworkers now have access to pieces of land, with sizes ‘owned’ being between 0.2 and 1.2 ha, with small additional amounts rented in (). In the CAs, most workers also hold land under the communal system. Workers with land holdings are most prominent in the CAs (99%), followed by the LSCFs (89.1%), the compounds (87.1%), A2 farms (78.9%), A1 farms (73.5%) and A2-JV farms (72.1%).

Table 2. Farmworkers’ land access and use (ha).

Across the land-use types, illegal land access, including vernacular land purchases (cf. Shonhe Citation2017; Mkodzongi Citation2018) and an emerging land rental market are shaping agricultural production and commercialisation. 16.9% of workers confirmed renting in land. In the CAs, people can gain such allocations from local leaders, and nearly everyone has a small plot. For compound-based farmworkers,Footnote5 as one of them explained:

We were excluded from the land reform process because we were viewed as part of the opposition and enemies of the state. However, due to limited work opportunities after the towns, many of us now rent-in land from those who benefitted. The small pieces we used to get through an allocation from the white commercial farmers have now been allocated to the new settlers. To get it from them, we have had to use various means, including payment of cash, the supply of farm inputs and supply of labour during the farming seasons. Unfortunately, the government does not include us in the agricultural input support programmes and therefore we have to find a way to get inputs on our own. Some have managed to access tobacco contract farming through.

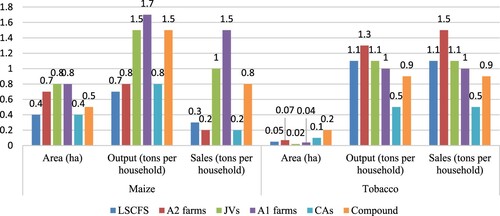

In the A1 areas, a mix of farmworkers was identified. This included those with land allocated under the land reform; those who have migrated to the area and are renting or illegally occupying land and those who are living at the homesteads of land reform settlers but without land. Among farmworkers, those in the A1 sector have the highest maize output averaging 1.7 tonnes per household, while those in the A2 sector have the highest tobacco and sales, averaging 1.3 tonnes per household in 2017 (). The low proportion of workers tilling land in the A2-JV cases (13.7%, averaging 0.2 ha) reflects the tighter management regime and low land holdings in these settings. During an in-depth interview, a workerFootnote6 in an A2-JV farm indicated that: ‘The Chinese employers are too demanding. They make us work long hours, including public holidays and weekends but they do not pay overtime’. Indeed, the A2-JVs probably most resemble the situation found in the LSCFs before land reform.

These poor conditions are not replicated in the LSCF in our sample, where wages could be supplemented with agricultural production on small garden plots and in illegal settlements nearby, and there is much more flexibility permitted than during the pre-land reform era. One LSCF workerFootnote7 noted that: ‘while the white commercial farmers used to allocate us pieces of land, we used only for maize production, now we also grow cash crops such as tobacco and earn some money which we use to supplement wage incomes’.

Across the sectors, most farmworkers now have land for maize and tobacco production. Our study reveals that the yield levels (output/ha) are relatively high for both tobacco and maize, reflecting the intensity of production on small plots as well as the skill of these workers. Maize is the dominant crop and is grown to meet household food security requirements, with the surplus being marketed to earn money to pay school fees and to buy additional food. For some, tobacco supplements this income. Own-farm production has the potential to increase farmworker autonomy as they make choices between tilling their own pieces of land or providing temporary work to other farmers. However, such autonomy emerges in highly precarious employment settings, whereby farm production is often necessary to supplement limited and intermittent farm wages in order to meet basic social reproduction needs. In this way, the informal economy, including family farming, acts to subsidise capital, offsetting the requirements to pay a living wage (Shivji Citation2009).

6. Diversified livelihoods

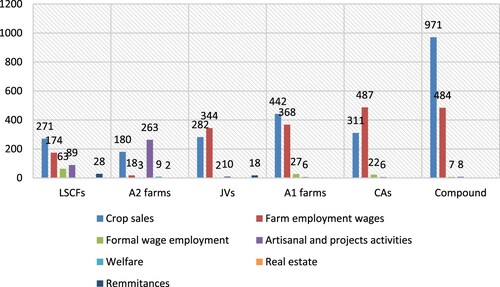

With the increasing importance of own farming among farmworkers, sales of agricultural commodities now exceed income from farm labour in compounds, A1 A2 and LSCFs farms (). The category ‘farmworker’ clearly needs rethinking; following Shivji (Citation2017) these are a much broader category of ‘working people’ struggling to make ends meet in challenging settings. Even though income sources are differentiated across farming sectors, there is considerable diversification, even in the LSCF setting where classic wage work is expected. Income from agricultural produce sales was significant among those living in compounds, those working for A1 and A2 farmers and those working on LSCFs. The sale of labour was only the most important amongst those workers in our samples in the CAs and A2-JVs.

As shown in , other sources of income beyond formal wage employment include artisanal mining and remittances. In the A2 farms, and less significantly in the LSCFs, many younger farmworkers are involved in projects such as poultry, market gardening and buying and selling of agricultural commodities along the main road. Total incomes were highest among those living in farm compounds, mostly working as contract workers and most diversified among those working on LSCFs. Those working on A2 farms, especially where farms were barely functioning, often had to seek other sources of income, as farms formed a base for diversified income activities. While varied across cases, our data show therefore how the traditional vision of ‘farmworker’ has disappeared, and a diverse, new labour regime is emerging. For example, Mr DM, who is 28 years’ old and works for an A2 farmer in Mvurwi explained that:

I work for an A2 farmer who resides in Harare but grows maize and tobacco. During the off season we have established sources of income as I am employed on a temporary basis, as with many others staying in the compound. To gain a living, I go to Jumbo mine where artisanal mining (chikorokoza) is now very popular. Through chikorokoza, I am able to buy food for my family back here and in Chiweshe communal area. Others are involved in buying and selling of a variety of goods, including fish from Kariba and are making lots of money.

7. Patterns of accumulation and social differentiation

What are the implications of these varied patterns of farm employment and the diversified livelihoods of farmworkers across land use types? What patterns of social differentiation are observed across and within sites, and how is this influencing the dynamics of accumulation? What forms of investment and agricultural commercialisation result? These are important questions if we are to understand the emerging class dynamics amongst ‘workers’ in these areas, and the wider implications for the future of commercial agriculture.

Our study shows how access to land and increased opportunities to diversify into off-farm activities now undergirds farmworker social differentiation (cf. Chambati Citation2011, Citation2013; Scoones et al. Citation2018a). This is completely different to the situation prevailing in the pre-land reform period. The new agrarian labour relations now consist of those who are capable of accumulating new productive assets such as cattle, ploughs, scotch carts, water pumps, tobacco curing barns, and some household assets including televisions and solar panels, among other items. However, this is differentiated across types of employment, with two clear categories emerging. Those with some access to land (mostly in CAs and A1 farms) accumulate more assets (such as solar panels and TVs), while those without (notably in A2-JVs) accumulate fewer assets and have a higher numbers of days when they have insufficient food. For example, PM (2019)Footnote8 noted:

I have barely accumulated any assets over the past five years. Three of my family members work for the Chinese here. The wages are low and only enable me to pay school fees for my children as well as buy some food. The other problem we have here is that the Chinese do not want to grow maize. In the past we used to get rations from the white farmers, and didn’t have to struggle with issues of where to get food.

I normally use the funds that I earn from crop sales to meet households needs. I have not bought any farming assets because I don’t have a piece of land of my own. Currently, I rely upon a subdivided piece of land that I got from Mr. G. I grow maize, sweet potatoes and tobacco from which I earn some money I use to acquire some assets. I do piecework for the plot holders, helping with a whole range of activities, including ploughing, planting, weeding, and harvesting. Since I used to work for the white commercial farmer here, I can handle tobacco curing, grading and packing. If I had my own piece of land I would have built a home and acquire more assets than I have so far.

Contestation and constraints over access to resources such as land have gender and generational dimensions. This may limit accumulation opportunities leading to increased precarity and constraints on social reproduction. As already observed, women are employed mostly as temporary workers earning much less than permanent male workers. Many women and young people have been unable to secure land in their own right and artisanal mining and other projects are relied upon, but these can be highly precarious income-earning options, meaning that outside marriage contracts and reliance on parents, independent sources of livelihood are highly challenging.

8. Worker-peasants and peasant-workers: new labour regimes

Much academic debate has focused on a discourse centred on a linear transition, seeing farmworkers as either moving towards a class of African wage-labour, profiting from modernising, efficient, large-scale agricultural commercialisation or into peasant-based family farming. Yet our data show that neither of these simple transitions is happening. Most of those we defined as ‘farmworkers’ – both men and women – combine elements of both small-scale agricultural work and wage work through various types of employment. In addition, they also participate in the informal economy, with involvement in small-scale artisanal mining, trading and so on.

Such diverse ‘working people’ (Shivji Citation2017) represent the ‘fragmented classes of labour’ (Bernstein Citation2006, 449), relying on often poorly remunerated activities, combining in a complex struggle for livelihoods. The term ‘semi-proletarian’ also describes this compromise between employed wage work in capitalist enterprise and self-provisioning through agriculture combined with a range of entrepreneurial ‘self-employment’ activities (Moyo and Yeros Citation2005). Across our sites we see an array of patterns, ranging from stable wage work to successful accumulation largely from part-time farming to diversified livelihoods emerging under highly precarious conditions. Our data equally do not show a linear transition to full proletarianisation or a return to the peasantry. Instead, a more complex story is evident. A dual character of worker-peasants or peasant-workers in the context of an informalised economy and labour market is observed. Ambivalent, hybrid class positions – all highly dynamic – describe the new labour regimes. Labelling thus becomes difficult: ‘farmworker’ is clearly an inadequate descriptor, but as an important set of ‘classes of labour’ supporting agriculture under variable labour regimes, these diverse working people are clearly vital for the wider agrarian economy, and a greater understanding of their livelihoods is important.

In post-land reform Zimbabwe, access to land by former farmworkers displaced in situ, and now living in former labour compounds, has enabled them to engage in farming and other off-farm activities facilitating consolidation as accumulating worker-peasants. They have mobilised their skill and labour to work for the new A1 and A2 farmers, but increasingly on their own terms. Gaining access to land has been central, and skilled farm work has allowed them to produce and accumulate, even from very small plots. Although not universally the case, plots are held by men, but farmed jointly as a family. Workers in the CAs tend to be poorer peasants, often younger households with limited land and productive assets, who need to complement own-farm production with piecework employment. A similar pattern occurs in the A1 areas, although there is more scope for land rental and borrowing and so building an asset base through farming.

In the LSCF, A2 and A2-JV areas, farmworkers are of the more classic wage worker, but flexible expansion to other livelihood options is occurring, with a range of land acquisition and informal employment opportunities pursued, as wage work becomes insufficient to sustain livelihoods. This becomes necessary especially for temporary workers, particularly women and younger people who, due to casualisation of the labour market, can only rely on wage employment for part of the year. Casualisation and feminisation of labour go hand-in-hand, and most women engage in the labour market on a temporary, informal basis, usually responding to seasonal demand. In operations with greater management intensity, such as the A2-JVs, such flexibility is less prevalent, but is sometimes compensated for in part through more stable even if often low paid wage employment. It is usually the preserve of men.

These categories are not static. People move between places and seek different opportunities. With the offer of land – for example, the illegal land invasion near our LSCF case – workers may leave their compounds and adopt a more flexible, bricolage approach, while maintaining some links to the original farm. Compound dwellers may accrete land holdings and become full-time farmers, abandoning wage work as an option, while communal area dwellers may abandon their areas in the hope of better opportunities in full-time work on LSCFs, A2-JVs or A2 farms or as farmers in a resettlement area.

The removal of the old form of ‘domestic government’ on commercial farms and its replacement with ‘residential autonomy’ following land reform has resulted in a major shift in labour regimes. The massive informalisation of the economy after 2000 generated a new impetus to diversify livelihoods, creating new classes of labour. The new ‘farmworker’ – working people combining wage work with a range of other activities including agriculture – enjoys greater bargaining power resulting from diversified livelihoods options. As we have shown, this is especially so if access to land is secured. As a result, a combination of political, economic, and social processes combines to generate accumulation opportunities for some, while others subsist under conditions of extreme precarity. It is a highly fluid situation, with no single labour regime evident. Over time, opportunities change. With a more stable economy, and a political settlement around land, for example, then wage work on the larger capitalist farms may become more of an option, although it will always compete with individual entrepreneurial activity on or off-farm. There is therefore no predictable structural transition, and a much more variegated pattern of production and employment across scales is observed.

9. Conclusion

Many studies of agrarian labour relations following land reform miss these highly differentiated shifts in land access and livelihoods by so-called farmworkers. A more differentiated view, across and within land use types, suggests a focus on the more encompassing conception of diverse working people, with changing class positions and identities associated with rural labour in the post-land reform setting. Today’s farmworkers are differentiated not only on the basis of the hierarchy in the workplace, but through variations in land access. Due to limitations of livelihood opportunities, workers in more commercialised farms (notably the A2-JVs) are not accumulating as much, compared to those in compounds, the CAs and the A1 farms. For those employed as contract and seasonal workers, the new-found freedoms do not only mean freeing up time to engage in diversified farming and non-farm activities, but a reduction in labour available to other farmers. This is especially important for women, combining income-earning and care work. This removal of the restrictions of ‘domestic government’ therefore ushers in the freedoms to withdraw labour, leading to shortages and an expanded ability to negotiate for the better wages; although with other income earning opportunities to cover social reproduction needs, including from agriculture, such wage work in capitalist farms may effectively be subsidised through family and especially women’s labour.

There are a number of wider implications arising from our findings. Without a stable, resident workforce as existed in the past, commercial agriculture must mobilise labour in new ways, in the context of changing livelihood opportunities for rural populations. Moving from a narrow framing of ‘farmworker’ to ‘working people’ suggests opening up a discussion about how wage work is combined with other forms of income earning in commercial farming areas. It also raises questions about rural politics and how such working people can mobilise in opposition to capital in the context of a new agrarian setting (cf. Shivji Citation2017); perhaps not as a singular working class or an alliance between peasants and workers, but as ‘classes of labour’ existing in a neoliberal economy (Bernstein Citation2006). For such working people, access to land may be as important as salary levels and working conditions, suggesting new foci for organisations advocating workers’ rights and welfare. Policy frameworks for land access for workers in farming areas do not exist and many must get by through informal, sometimes illegal, arrangements. This is especially so for those living in former farm compounds with no formal rights of settlement and land occupation. Women and young people, who suffer from both a lack of access to land and permanent wage work, require particular support, as across land use types they are the least likely to gain opportunities for accumulation. As key players in the new post-land reform agrarian landscape, as farmers as well as the new workers, the diverse array of working people in commercial farming areas therefore require attention from government, as well as support and advocacy organisations, with a new policy framework to support rural workers’ livelihoods.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support received from the UK Department for International Development-funded Agricultural Policy Research in Africa programme of the Future Agricultures Consortium, as well as fieldwork support from Simbai Msikinye, Norman Aniva, Vincent Sarai, Tauya Zengeya, Athanas Chimombe, Vimbai Princess Gabriella Charwadza and Selina Semende. All data presented in this paper derive from the APRA survey from 2017–19 undertaken across all sites. We finally wish to thank the many farmers we interacted with during data collection, including during surveys, focus groups and interviews as well as the anonymous reviewer of this paper for helpful suggestions for improvement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Toendepi Shonhe

Toendepi Shonhe is a political economist/researcher at TM School, University of South Africa. Toendepi holds a PhD in development studies from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and a masters in public policy management from the University of the Witswatersrand, South Africa. His research interests are in land reform and agricultural commercialisation in Africa.

Ian Scoones

Ian Scoones (Prof) is an agricultural ecologist whose research links natural and social sciences, focusing on relationships between science and technology, local knowledge and livelihoods and the politics of agricultural, environmental and development policy processes.

Felix Murimbarimba

Felix Murimbarimba is an independent agricultural researcher. He has extensive experience and publication history in the area of agrarian change and farming systems based on empirical studies carried out in many parts of Zimbabwe.

Notes

1 Interview PH, Chiweshe CA, 24 July 2019.

2 Personal interview with PM, Mvurwi area, 26 July 2019.

3 Personal interview, RG, Mvurwi area, 21 July 2019.

4 Personal interview, RC, Mvurwi area, 14 January 2019.

5 Personal interview PM, Mvurwi area, 13 January 2019.

6 Personal interview, NT, Mvurwi area, 18 November 2019.

7 Personal interview, MM, Mvurwi area, 23 November 2019.

8 Interview with PM, A2-JV worker, 25 July 2019, Mvurwi area.

9 Interview with YV, 13 January 2019, Mvurwi area.

References

- Amanor-Wilks, D. E. 1995. In Search of Hope for Zimbabwe’s Farm Workers. Harare: Date Line Southern Africa and Panos Institute.

- Arrighi, G. 1970. “Labour Supplies in Historical Perspective: A Study of the Proletarianization of the African Peasantry in Rhodesia.” The Journal of Development Studies 6 (3): 197–234.

- Bernstein, H. 2006. “Is There an Agrarian Question in the 21st Century?” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’Etudes du developpement 27 (4): 449–460.

- Bernstein, H. 2007. “Agrarian Questions of Capital and Labour: Some Theory about Land Reform.” In The Land Question in South Africa: The Challenge of Transformation and Redistribution, edited by L. Ntsebeza and R. Hall, 27–59. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Berry, S. S. 1993. No Condition is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in sub-Saharan Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Breman, J. 2010. Outcast Labour in Asia: Circulation and Informalization of the Workforce at the Bottom of the Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Byres, T. J. 1977. “Agrarian Transition and the Agrarian Question.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 4 (3): 258–274.

- Chambati, W. 2011. “Restructuring of Agrarian Labour Relations After Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (5): 1047–1068.

- Chambati, W. 2013. “The Political Economy of Agrarian Labour Relations in Zimbabwe After Redistributive Land Reform.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy: A Triannual Journal of Agrarian South Network and CARES 2 (2): 189–211.

- Chambati, W. 2017. “Changing Forms of Wage Labour in Zimbabwe’s New Agrarian Structure.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy: A Triannual Journal of Agrarian South Network and CARES 6 (1): 79–112.

- Chhachhi, A. 2014. “Introduction: The ‘Labour Question’ in Contemporary Capitalism.” Development and Change 45 (5): 895–919.

- Chiweshe, K. M., and T. Chabata. 2019. “The Complexity of Farmworkers’ Livelihoods in Zimbabwe After the Fast Track Land Reform: Experiences from a Farm in Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe.” Review of African Political Economy 46 (159): 55–70.

- Clarke, D. G. 1973. Black Contract Labour and Farm Wage Rates in Rhodesia. Labour Research Seminar No. 2.

- Clarke, D. G. 1977. Agricultural and Plantation Workers in Rhodesia: A Report on Conditions of Labour and Subsistence (Vol. 6). Gweru: Mambo Press.

- Cousins, B. 2013. “Smallholder Irrigation Schemes, Agrarian Reform and ‘Accumulation from Above and from Below’ in South Africa.” Journal of Agrarian Change 13 (1): 116–139.

- Cousins, B., A. Dubb, D. Hornby, and F. Mtero. 2018. “Social Reproduction of ‘Classes of Labour’ in the Rural Areas of South Africa: Contradictions and Contestations.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5–6): 1060–1085.

- CSO (Central Statistics Office). 2001. Agricultural Production on LSCF 2000. Harare: CSO.

- Dunlop, H. 1971. ‘The Development of European Agriculture in Rhodesia 1945–1965’. Harare: University of Rhodesia.

- FCTZ (Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe). 2000. Survey of Commercial Farm Worker Characteristics and Living Conditions. Harare: Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe.

- Ferguson, J., and T. M. Li. 2018. “Beyond the ‘Proper Job:’ Political-economic Analysis after the Century of Labouring Man.” Working Paper No. 51. Cape Town: PLAAS, University of the Western Cape.

- Harriss-White, B. 2003. India Working: Essays on Society and Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hartnack, A. 2016. Ordered Estates: Welfare, Power and Maternalism on Zimbabwe’s (Once White) Highveld. Harare: Weaver Press.

- Helliker, K., and S. Bhatasara. 2018. “Inside the Land Occupations in Bindura District, Zimbabwe.” African Studies Quarterly 18 (1): 1–18.

- Hodder-Williams, R. 1983. White Farmers in Rhodesia, 1890–1965. London: Macmillan.

- Jayne, T. S., J. Chamberlin, and R. Benfica. 2018. “Africa’s Unfolding Economic Transformation.” The Journal of Development Studies 54 (5): 777–787.

- Jha, P. 2021. Labour Questions in the Global South. Gateway East, Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Kanyenze, G. 2001. “Zimbabwe’s Labour Relations Policies and Implications for Workers.” In Zimbabwe’s Farm Workers: Policy Dimension, edited by Amanor-Wilks, 86–114. Lusaka: Panos Southern Africa.

- Loewenson, R. 1992. Modern Plantation Agriculture: Corporate Wealth and Labour Squalor. London, NJ: Zed Books.

- Luebker, M. 2008. Employment, Unemployment and Informality in Zimbabwe: Concepts and Data for Coherent Policy-Making. Geneva: ILO.

- Mafeje, A. 1985. “Peasants in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Africa Development 10 (3): 29–38.

- Magaramombe, G. 2010. “‘Displaced in Place’: Agrarian Displacements, Replacements and Resettlement among Farm Workers in Mazowe District.” Journal of Southern African Studies 36 (2): 361–375.

- Mbanga, T. 1991. Tobacco, a Century of Gold. Harare: ZIL Publications (Pvt) Ltd.

- Mkodzongi, G. 2018. “Peasant Agency in a Changing Agrarian Situation in Central Zimbabwe: The Case of Mhondoro Ngezi.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 7 (2): 188–210.

- Moyo, S. 2007. “The Land Question in Southern Africa: A Comparative Review.” In The Land Question in South Africa, edited by L. Ntsebeza, and R. Hall, 60–84. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Moyo, S. 2011. “Three Decades of Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (3): 493–531.

- Moyo, S., and P. Yeros. 2005. “The Resurgence of Rural Movements Under Neoliberalism.” In Reclaiming the Land: The Resurgence of Rural Movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, edited by S. Moyo, and P. Yeros, 8–66. London & New York: Zed Books.

- O’Laughlin, B. 1996. “Through a Divided Glass: Dualism, Class and the Agrarian Question in Mozambique.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 23 (4): 1–39.

- Oya, C. 2013. “Rural Wage Employment in Africa: Methodological Issues and Emerging Evidence.” Review of African Political Economy 40 (136): 251–273.

- Oya, C., and N. Pontara, eds. 2015. Rural Wage Employment in Developing Countries: Theory, Evidence, and Policy. London: Routledge.

- Palmer, R. 1977. Land and Racial Domination in Rhodesia. London: Heinemann Educational.

- Phimister, I., and R. Pilossof. 2017. “Wage Labor in Historical Perspective: A Study of the Deproletarianization of the African Working Class in Zimbabwe, 1960–2010.” Labor History 58 (2): 215–227.

- Pilossof, R. 2014. “Labor Relations in Zimbabwe from 1900 to 2000: Sources, Interpretations, and Understandings.” History in Africa 41: 337–362.

- Pilossof, R. 2018. “Farms, Farmworkers and New Forms of Livelihoods in Southern Africa.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (2): 473–480.

- Raftopoulos, B. 2009. “The Crisis in Zimbabwe.” In Becoming Zimbabwe, edited by B. Raftopoulos, and A. Mlambo, 201–232. Harare: Weaver Press.

- Rubert, S. C. 1998. A Most Promising Weed: A History of Tobacco Farming and Labour in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1890–1945. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Rutherford, B. 2001. Working on the Margins: Black Workers, White Farmers in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe. Harare & London: Weaver Press & Zed Books.

- Rutherford, B. 2017. Farm Labor Struggles in Zimbabwe: The Ground of Politics. Edited by Blair Rutherford. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Sachikonye, L. 1986. “State, Capital and Trade Unions.” In Zimbabwe: The Political Economy of Transition 1980–1986, edited by I. Mandaza, 243–74. Dakar, Senegal: Codesria.

- Sachikonye, L. M. 1997. “The Socio-Economic Effects of SAP on Formal Sector Labour in Zimbabwe.” A paper presented before the 2nd African International Industrial Relations Association’s Regional Congress, Harare, Zimbabwe, Oct, 29–31.

- Sachikonye, L. M. 2003. The Situation of Commercial Farm Workers After Land Reform in Zimbabwe. Harare: Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe.

- Sachikonye, L. M. 2007. “Where to Zimbabwe? Looking Beyond Mugabe.” South African Labour Bulletin 31 (4): 39.

- Scoones, I., N. Marongwe, B. Mavedzenge, F. Murimbarimba, F. Mahenehene, and C. Sukume. 2010. Zimbabwe’s Land Reform: Myths and Realities. Oxford: James Currey. Harare: Weaver Press. Johannesburg: Jacana.

- Scoones, I., B. Mavedzenge, F. Murimbarimba, and C. Sukume. 2018a. “Labour After Land Reform: The Precarious Livelihoods of Former Farmworkers in Zimbabwe.” Development and Change 50: 805–835.

- Scoones, I., B. Mavedzenge, F. Murimbarimba, and C. Sukume. 2018b. “Tobacco, Contract Farming, and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (1): 22–42.

- Scoones, I., T. Shonhe, T. Chitapi, C. Maguranyanga, and S. Mutimbanyoka. 2020. “Agricultural Commercialisation in Northern Zimbabwe: Crises, Conjunctures and Contingencies, 1890–2020.” Working Paper 35. Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Shivji, I. G. 2009. Accumulation in an African Periphery: A Theoretical Framework. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

- Shivji, I. G. 2017. “The Concept of ‘Working People’.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy: A Triannual Journal of Agrarian South Network and CARES 6 (1): 1–13.

- Shonhe, T. 2017. Reconfigured Agrarian Relations in Zimbabwe. Namenda, North West region, Cameroon: Langaa rpcig.

- Shonhe, T. 2018. “The Political Economy of Agricultural Commercialisation in Zimbabwe.” APRA Working Paper 12. Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Tabata, I. B. 1954. “The Agrarian Problem.” In The Dynamics of Revolution in South Africa: Speeches and Writings of I.B. Tabata, edited by D. Taylor, 122–134. London: Resistance Books.

- Tandon, Y. 2001. “Trade Unions and Labour in the Agricultural Sector in Zimbabwe.” In The Labour Movement in Zimbabwe: Problems and Prospects, edited by B. Raftopoulos and L. Sachikonye, 221–490. Harare: Weaver Press.