ABSTRACT

This study explores the relationships among sport stadium visitors’ experiences, satisfaction, team brand image, and destination image. A text mining approach was first used to analyse 26,538 individual reviews from 17 European sport stadiums on TripAdvisor. The online reviews were then used as input to create a word frequency of each individual review and construct a structural equation model. Results indicate that the visitor experience had a strong impact on team brand image and a moderate effect on destination image. Satisfaction mediated the influence of the visitor experience on team brand image, but not on destination image. Team brand image exerted a significant but small impact on destination image. These findings show that stadium visits impact the marketing of both host teams and cities. City, leisure and stadium managers should therefore coordinate their efforts to highlight teams as part of a city’s cultural brand to generate image-based benefits for both.

1. Introduction

Tourism and leisure marketers have highlighted the overall importance of international sport events to enhance destination image (Andersson et al., Citation2021; Chang et al., Citation2021), but the role stadium experiences as a lever to destinations is yet to be understood. Sport teams regularly attract fans to attend sport events in stadiums (Lee, Citation2022). Teams such as Real Madrid CF, FC Bayern Munich, and Manchester United FC continue to be recognised by enthusiasts in every corner of the globe (Giulianotti & Robertson, Citation2004; Mitten, Citation2017). More importantly, major sport stadiums function as hubs that draw local communities’ and visitors’ attention, contribute to local economies, and leverage the city brand where a team is based (Agha, Citation2013). Cities often make sizeable financial investments by building and refurbishing stadiums to improve related services and potential revenue (e.g. BBC, Citation2021). For example, in the UK, satellite fans (i.e. individuals who, despite lacking shared geography, have a bond with a team; Kerr & Gladden, Citation2008), tend to spend four times more than other city visitors; and in 2016/2017, satellite fans spend roughly £555 m during their travels to the UK to see a team (Premier_League, Citation2019). Overall, stadium visitors generate a significant economic impact on the host city (Cho et al., Citation2021; VisitBritain., Citation2019), frequently visit other sights in the city (Salas-Olmedo et al., Citation2018), and form a brand image of the host destination in their mind. The current study aims to examine how visitors’ experiences with stadium services benefit the team and the leisure management of the host city as a destination.

The influence of stadiums far surpasses the sport events that represent a team’s core product. Well-established teams often provide supplementary services in stadiums to attract consumers beyond attending games. Options and experiences can include several leisure activities, such as visits to museums, halls of fame, pitch-level photographs, guided tours, malls, or restaurants (Humphreys, Citation2019; Uvinha et al., Citation2020). These offerings are intended to enhance the visitor experience and generate additional revenue, albeit to a lesser extent (e.g. malls, guided tours) than matchday or merchandise revenue (Marca., Citation2018). Such stadium experiences can attract loyal fans as well as casual supporters who admire the club’s history. Many stadiums have even become tourist attractions in their respective cities, with tourists visiting due to these venues’ social significance (Ginesta, Citation2017). For example, Ramshaw et al. (Citation2013) found that virtual and on-site stadium tours affects visitors’ level of fandom and repeat consumption, while Cho et al. (Citation2019) discovered that football club fans’ nostalgia influences their motivation to visit an overseas stadium and simultaneously experience the host destination.

Given the importance of understanding how consumers connect to sport teams through stadium experiences, it is worthwhile to examine sport stadiums’ potential to contribute to the brand image of teams and host cities as a destination. Sport stadium visitors encompass a key tourism segment (Cordina et al., Citation2019) that can benefit both a team and the host city’s brand (Cho et al., Citation2019). However, empirical evidence is scarce regarding the effects of consumers’ stadium visit evaluations on the team and host city (i.e. in terms of the management of destination image). Also, studies assessing the link between teams and host cities have largely relied on traditional surveys with structured questions (e.g. Ginesta, Citation2017); this data collection approach cannot necessarily capture visitors’ holistic perceptions of their experiences (Moro et al., Citation2019).

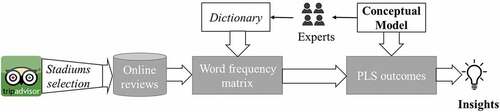

Based on prior work and the need to address the meaning of sport stadium experiences for the image of host teams and cities, this study proposes and tests a model to uncover the relationships between sport stadium visitors’ experiences and related entities (i.e. team brand image and associated city destination image) as well as the mediating role of visitor satisfaction through online reviews. We chose to derive insight from voluntarily provided opinions without needing to recruit a respondent pool. Being bound by potential respondents’ availability to participate in a survey typically leads to a smaller sample that is often biased (Gehlbach & Barge, Citation2012). On the other hand, online reviews play an important role to help manage the destination image (Bigne et al., Citation2019). In this study, 26,583 individual sport stadium reviews were first collected from TripAdvisor and analysed through text mining to create a coherent set of keywords to evaluate the model relationships. Then, by examining a word frequency matrix for each individual review using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), we enriched knowledge of the consumer experience and destination’s marketing through sport stadiums.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

Sport stadiums function as both a symbolic ‘home’ for teams and fans (Richards et al., Citation2021) and a major tourism attraction (Ginesta, Citation2017). These venues therefore represent an essential leisure asset for teams and cities. Informed by research on the consumer experience and brand architecture, this study explores the relationships between stadium visitors’ experiences and related entities (i.e. team brand image and associated city destination image) along with the mediating role of visitor satisfaction.

2.1. Stadium experience and its implications

Sport stadiums often afford visitors with opportunities to indulge their imagination (i.e. visiting places where their idols enjoyed glorious moments), constituting a sub-branch of sport tourism (Cordina et al., Citation2019). For teams, a visit represents a chance to engage fans with the team brand by providing a unique experience (Woratschek et al., Citation2020). Sport facilities also offer host destinations various financial and brand benefits (Ginesta, Citation2017). For instance, FC Barcelona earned £338 m in revenue from matchday (Deloitte, Citation2020) during the 2019/2020 season and Qatar’s Al Wakrah Sports Complex is considered one of the top attractions in the city of Al Wakrah (Tansey, Citation2013).These examples reflect sport stadiums’ roles as a home for teams and as means of promoting a destination’s image and contributing to a city’s positioning (Ginesta & Eugenio, Citation2014).

A stadium visit is a leisure activity undertaken as a rewarding experience that fulfils one’s interests (Humphreys, Citation2019), beyond simply watching a sport event. Sport teams offer ancillary services in addition to stadiums’ core products (i.e. sport events) to attract visitors (Ginesta, Citation2017). Stadium visits thus involve multiple elements that shape visitors’ experiences (e.g. visitor characteristics, social experience, physical setting) and inform their perceptions of related entities (Kaplanidou et al., Citation2012).

As Berry (Citation2000) noted, a customer’s experience with a service provider is a main driver of brand perceptions. Consumers’ stadium experiences will presumably affect their evaluations of the team brand, given that one’s image of a team is strongly influenced by actual service (Ross, Citation2006). Team brand image refers to the aggregate result of consumers’ opinions about a team (i.e. brand associations); this image generally relies on one’s past experiences and is believed to be pivotal in granting brands a competitive edge (Papadimitriou et al., Citation2016). Biscaia et al. (Citation2016) pointed out that positive stadium experiences can lead individuals to develop a favourable brand image of a team based on recall of these experiences.

It is essential to understand consumers’ experiences with team brands: brand experiences ground the information processing that produces brand-related associations (Keller, Citation1993). The team is the service provider in a stadium experience, and customers’ service experiences are thought to influence brand formation (Berry, Citation2000). Accordingly, consumers are expected to connect the stadium experience with the team brand. The following hypothesis is hence proposed:

H1:

The stadium visitor experience has a positive impact on team brand image.

Pleasant stadium experiences can also contribute to a positive image of the team’s city as a destination (Wang & Hsu, Citation2010), which should call the attention of destination and leisure marketers (Heere et al., Citation2019). The concept of destination image includes one’s impressions, ideas, beliefs, and expectations about a destination (Jiang et al., Citation2017). This notion can encompass affective (feelings and emotions), cognitive (knowledge and beliefs), and/or conative (intentions to revisit) evaluations (Kaplanidou et al., Citation2012). The relationship between an appealing destination feature and its impact on destination image has been widely explored in the leisure literature. For example, Jansen-Verbeke and van Rekom (Citation1996) noted that museums can influence visitors’ perceptions of the host city and boost the number of tourists. Similarly, sport stadiums represent a major attraction in many cities (Ginesta, Citation2017; Uvinha et al.,): the stadium is fans’ primary association with their team’s brand (Biscaia et al., Citation2016; Kunkel et al., Citation2017). Studies have shown that brands within the same ecosystem can also affect one another (e.g. Cobbs et al., Citation2015). As such, one may argue that stadium visits will help highlight the host city as a travel destination as postulated:

H2:

The stadium visitor experience has a positive impact on the host city’s destination image.

2.2. Team brand image and host city

Sport teams, like any other organisation, should manage their brand image. Teams sell tangible items (e.g. merchandise) and intangible products (e.g. team matches), and their brand’s economic value is frequently linked to marketplace manifestations of consumers’ brand perceptions (Datta et al., Citation2017). In this sense, one can assume that any sport team’s brand image is likely their most valuable asset (Kunkel et al., Citation2014). Building on the seminal work of Keller (Citation1993) and Aaker (Citation1991), an array of sport brand associations have been identified – teams’ success, head coaches, star players, management (i.e. product-related attributes), logos and marks, history and tradition, stadiums, sponsors (i.e. non-product-related attributes), fan commitment, concessions, and social interaction (i.e. benefits) (e.g. Biscaia et al., Citation2016; Kunkel et al., Citation2017; Ross, Citation2006).

Empirical studies have revealed spillover effects from team brands to other brands within the same environment (Cobbs et al., Citation2015; Su & Kunkel, Citation2019). This outcome is rooted in brand architecture, wherein associations exist among brands within an ecosystem with different market segments (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, Citation2000). More concretely, brands do not exist in isolation; individuals’ perceptions of a brand are often influenced by other brands within the ecosystem (Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020). For instance, FC Bayern Munich and FC Barcelona each include the city name in their brand names. Therefore, although these brands do not belong to the same entity, spillover effects may apply from the team to the city and vice versa. Favourable mental associations towards the team may thus benefit the city’s image as an appealing destination (Pritchard et al., Citation2020), representing an important aspect to consider by destination leisure managers. Against this backdrop, and given that sport stadiums often become iconic structures that draw a broad audience (Uvinha et al.,), we propose the following:

H3:

Team brand image has a positive impact on the host city’s destination image.

2.3. Mediating role of satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction is a pleasurable fulfilment response (Chick et al., Citation2021; Oliver, Citation1993) resulting from one’s cognitive and affective reactions to a service encounter (Rust & Oliver, Citation1994). Such satisfaction depends on one’s expectations and subjective perceptions of service performance (Wolter et al., Citation2017); consumers evaluate service providers on the basis of personal experience (Lugosi & Walls, Citation2013). An enjoyable stadium visit can boost consumers’ satisfaction and in turn benefit the team and city (Kaplanidou et al., Citation2012). Visitors’ (i.e. consumers’) assessments of their experiences may not be linked solely to the focal brand but instead include related brands (Kim et al., Citation2014). When a stadium experience is satisfying, the visitor will likely favour the team (i.e. through future transactional and non-transactional behaviours; Biscaia et al., Citation2017) and the city (i.e. through greater intentions to revisit the host destination and recommend it to others; Papadimitriou et al., Citation2016). Thus, ensuring consumer satisfaction is vital for both team managers (Biscaia et al., Citation2021) and destination leisure managers (Jeong & Kim, Citation2019). As an example, Chelsea FC supporters’ satisfaction from visiting the Allianz Arena in Munich, Germany, to watch their team’s victory in the 2011/12 Champions League final against FC Bayern Munich could reinforce Chelsea FC’s image as a successful team and compel attendees to revisit and recommend the city to others. Insights from branding research partially explain this phenomenon. A positive brand experience is a prime element of consumer satisfaction (Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). According to the experience-based norm framework (Cadotte et al., Citation1987), consumer experiences may extend to other brand units or related brands. Strong positive associations between brands within the same ecosystem (i.e. city and team) may also produce spillover effects and benefit both parties (Beverland & Farrelly, Citation2010; Lei et al., Citation2008). As satisfaction is fundamentally backward-looking (Wolter et al., Citation2017) and sport teams are often intricated with the host city’s image (Heere et al., Citation2011), consumer satisfaction could mediate the role of the stadium visitor experience on the image of the team and the host city. Our final hypothesis is therefore as follows and the hypothesised model is presented in :

H4:

Satisfaction mediates the relationship between both a consumer’s stadium visit experience and (a) team brand image and (b) the host city’s destination image.

3. Method

This study involved a mixed approach comprising text mining and SEM. In referring to secondary data rather than primary data gathered through a traditional survey, we focused on online reviews from TripAdvisor that captured stadium visitors’ lived experiences. TripAdvisor is often considered the most popular online platform used to get insights about destination image (Fernandes & Fernandes, Citation2018). The individual reviews on this platform provided access to freely contributed opinions (i.e. without the constraint of respondents’ availability to participate in a study) while conveying the true essence of visitors’ perceptions (Moro & Rita, Citation2018).

3.1. Data collection and preparation

We gathered 26,538 individual reviews, posted between 2001–2020, from the 17 major European football stadiums that had hosted the UEFA Champions League final since 2000 (). Visitors’ reviews were related to their experiences in the stadium, which could include game attendance and/or supplementary services (e.g. club’s museum, musical concert). We chose to collect reviews from stadiums that had hosted this league because these stadiums comply with UEFA Stadium Infrastructure Regulations (UEFA, Citation2021b) and are in cities with popular teams (UEFA, Citation2021).

Table 1. Selected stadiums.

Online reviews are commonly adopted to understand consumers’ perspectives on their experiences (e.g. Furtado et al., Citation2022; Nelson, Citation2021). Many online platforms enable individuals to share opinions about their visits. TripAdvisor is a popular website where visitors can post their thoughts upon visiting an attraction (Nelson, Citation2021). We developed a web scraping script in R, using the ‘rvest’ package, that iteratively crawled through the 17 stadiums’ TripAdvisor pages to collect all visitors’ comments. The subsequent dataset contained 26,538 individual reviews reflecting visitors’ opinions presented in continuous data points for each concept coming from each case. The data were then transformed into a structured format that enabled us to link words of each participant with theoretical concepts. Data were filtered as follows before processing the natural language: eliminating stopwords, articles, and adverbs; converting all words to lowercase; and applying stemming (i.e. merging similar words into a common term; e.g. ‘fabul’ or ‘fab’ = ‘fabulous’). This process was completed using the ‘tm’ package in R. The number of occurrences of each word by individual was counted to organise produced information and manage the study’s scope. All terms (i.e. words) repeated at least 10 times were retained, and those associated with theoretical concepts from the literature were grouped (e.g. Messi, Bale, and Ronaldo = ‘star player’). Terms associated with the four variables in the hypothesised model were also identified, leading to the creation of a dictionary (i.e. common words in online reviews). A panel of four independent consumer behaviour researchers from different universities and countries conducted a content analysis of the dictionary to reduce the inherent subjectivity of this task. Some terms were reallocated through a discussion and reconciliation process, and the final dictionary with theoretical concepts and example terms is presented in .

Table 2. Dictionary for the model variables.

Each review was analysed individually by identifying the word frequency associated with each theoretical dimension. This allowed to create continuous variables for each visitor’s review. To do so, we created a word frequency matrix, taking the set of individual online reviews and the dictionary as input. Each line in the matrix corresponded to one of the 26,538 individual reviews, and each column corresponded to each term (i.e. item) tied to the theoretical concepts listed in . Thus, one cell in the matrix corresponded to the number of times that item was mentioned in each review. This matrix mimicked individual responses to questions in a survey related to theoretical concepts on a case-by-case basis. If an item was mentioned frequently, then it was deemed important for that individual. Finally, the matrix was used as input for PLS-SEM analysis to evaluate relationships between the theoretical concepts in . A summary of our methodological approach is depicted in .

3.2. Data analysis

The proposed relationships were assessed using Smart PLS; this program enables users to estimate complex models containing many constructs, indicators, and structural paths without imposing distributional assumptions on the data (Hair et al., Citation2019). In line with the current study, PLS has been deemed appropriate in research related to theory development when the analysis is based on secondary data, preferably metric or quasi-metric data, and permits the unrestricted use of single-item and formative measures (Hair et al., Citation2019; Richter et al., Citation2020). Satisfaction and destination image were assessed using single-item measures identified via text mining as explained above. Following the same rationale, visitor experience and team brand image were formatively measured (i.e. derived from the cumulative effect of each unique attribute). This approach is consistent with earlier literature on sport branding (e.g. Kunkel et al., Citation2020) and the sport consumer experience (e.g. Horbel et al., Citation2016; Uhrich & Benkenstein, Citation2012). Formative assessment is preferable to a reflective approach because the former allows for unique team brand associations to not be conceptually interchangeable and not covary (Finn & Wang, Citation2014; Hair et al., Citation2019). For example, from a consumer perspective, individuals can associate excellent athletes with their team (i.e. star players) but have a poor opinion of team management. These two mental associations are vital to the development of team brand image (Kunkel et al., Citation2017; Ross et al., Citation2006).

As recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2019), we examined formative constructs’ multicollinearity (i.e. each indicator’s variance inflation factor [VIF] < 5) and validity (i.e. the significance of parameter estimates for each indicator after a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 resamples). The direct, indirect, and total effects of the model were tested through PLS-SEM regression analysis. A 5% level of significance was selected for investigating critical t values of path coefficients (t > 1.96). Mediation effects were also considered; we used the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping procedure to handle concerns about non-normal data (Nitzl et al., Citation2016), as it adjusts confidence intervals for skewness (Efron, Citation1987).

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of measures

Descriptive statistics are presented in indicating the word frequency variations among individual reviews. The validity assessment revealed that, although some outer loadings were below the suggested criterion of .50 (Hair et al., Citation2019), all were statistically significant for the formative measures of visitor experience and team brand image (). Based on statistical significance and the fact that all indicators represented common team brand associations (e.g. Ross et al., Citation2006), all indicators were retained to avoid omitting unique parts of the composite variable and reducing the theoretical domains’ content validity (Cenfetelli & Bassellier, Citation2009; Kunkel et al., Citation2020). The VIF scores further supported this decision (visitor experience: 1.027 < VIF <1.189; team brand image: 1.015 < VIF < 1.404), as multicollinearity was not an issue. Correlations among model variables () ranged from .166 to .679.

Table 3. Items, descriptive statistics, outer loading and correlation matrix.

4.2. Structural relationships

The structural model results appear in ; BCa bootstrapping results for all tested relationships are presented in . Path coefficients showed significant relationships between nearly all model variables. Visitor experience was a significant positive predictor of team brand image (β=.579, p < .001) and destination image (β=.341, p < 001). Thus, H1 and H2 were supported. Team brand image had a significant positive direct effect on destination image (β=.160, p < .001), supporting H3. In addition, visitor experience was positively related to satisfaction (β=.349, p < .001). The indirect effect of visitor experience on team brand image, via satisfaction, was consistently significantly positive (β=.100, p < .001), as were the total effects (β=.679, p < .001). As such, H4a was supported. On the contrary, satisfaction exerted a significant negative impact on destination image (β=-.032, p < .001); H4b was hence not supported. Despite satisfaction showing a small positive indirect effect (via team brand image) on destination image (β=.046, p < .001), the total effect was not significant (β=.014, p < .05). Both the indirect effect of visitor experience on destination image (β=.098, p < .001) and the total effects (β=.439, p < .001), via satisfaction and team brand image, were significant and positive. Overall, this model explained 53.3% (R2=.533) of the variance of team brand image, 12.2% (R2=.122) of the variance of satisfaction, and 20.4% (R2=.204) of the variance of destination image. These values reflect the model’s moderate explanatory power for team brand image and week explanatory power for satisfaction and destination image (Henseler et al., Citation2009). Even so, as R2 should be interpreted based on context (Hair et al., Citation2019), the identified R2 values contribute to a detailed assessment of consumers’ satisfaction with sport-related services (Leeuwen et al., Citation2002) and destination image (Pan et al., Citation2021).

Table 4. Path coefficients, indicator weights, and explained variance of Mediated structuralmodel.

5. Discussion and implications

This study integrated text mining and SEM. We began with secondary data from 26,538 individual unstructured online reviews, transformed these data into a structured format, and tested a model to delineate relationships between the sport stadium visitor experience, satisfaction, team brand image, and destination image. Research on sport stadium experiences has been driven by traditional primary data collection and focused on the benefits for sport brands. Our exploration of theoretical relationships based on online reviews contributes to the literature by capturing the essence of stadium experiences and their consequences for sport brands and host cities.

Our structural model showed that the sport stadium visitor experience had a strong direct effect on team brand image, extending research on the game experience (e.g. Byon et al., Citation2013; Yoshida & James, Citation2010) and corroborating the idea that customer experience is pivotal to developing a team’s brand image (Berry, Citation2000; Ross, Citation2006). To this end, well-planned visits with access to pre-visit information (e.g. site access, parking facilities, opening times) and investment in external stadium accessibility (e.g. shuttle service or free tickets for public transportation) may generate a better team brand image. Although the delivery of positive experiences is crucial for any service brand (Ross, Citation2006), favourable stadium visitor experiences may be even more important for tourists and satellite fans (Kerr & Gladden, Citation2008). More specifically, due to displacement, tourist and satellite fans infrequently visit the stadium – but when they do, they often move beyond the stadium’s core purpose (i.e. a team match) and visit other city sites (Cho et al., Citation2021), representing an important segment to target by team managers and destination and leisure marketers.

Another important finding is that the relationship between visitor experience and team brand image is partially mediated by consumer satisfaction. As stadium experiences are essential for the development of a favourable team brand image (Biscaia et al., Citation2016), it is necessary to create an environment that suits visitors’ expectations (Kempiak et al., Citation2017; Piramanayagam et al., Citation2020) and promotes satisfaction. Insight into visitors’ experiences (i.e. TripAdvisor data) underscore the importance of stadium managers investing in holistic experiences that can compensate for matches’ unpredictable outcomes (Yoshida, Citation2017). Visitor satisfaction also requires direct service encounters (Wolter et al., Citation2017). Managers should invest in events that supplement matches (e.g. halftime shows, networking events) in addition to providing ancillary services (e.g. museums, memorabilia sales) to offer more stadium contact points. This service exposure can increase visitors’ satisfaction and subsequently cultivate a positive team brand image.

A holistic approach to service delivery in sport stadiums (Biscaia et al., Citation2021) can benefit the host city as well, given that visitor experience has a positive direct impact on destination image. Similarly, the collective effects of visitor experience and increased team brand image on destination image were moderately positive. Positive perceptions about one’s stadium experience and a favourable team brand image therefore seem to spill over to the city (Beverland et al., Citation2021; Ribeiro et al., Citation2018), empirically supporting the notion that brands within an ecosystem tend to affect one another (Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020) and that sport events contribute to the destination brand (Su & Kunkel, Citation2019). This finding highlights the need for stadium managers and city leisure managers to acknowledge their complementary roles (i.e. of facilities and the overall city). Cooperative efforts can promote both the team and city (Ginesta & Eugenio, Citation2014) to collectively enhance team-related outcomes and the destination brand.

Effective communication through destination advertising campaigns generally influences individuals’ experiences (Kharouf et al., Citation2020). Sport and destination managers should hence use various platforms to disseminate information and highlight the team – city link and the positive experiences stadium visitors encounter. For example, city managers should support stadium enhancements aimed at improving the attendee experience, such as through expansion licences or improved transport infrastructure. Similarly, with the increased appeal of virtual reality site tours induced by the COVID-19 pandemic (Itani & Hollebeek, Citation2021), our findings suggest that enabling virtual touristic experiences with the possibility to have a tour of the stadium could benefit the destination image marketing strategy. City and leisure managers are advised to include sport stadiums as relevant tourism attractions in a city’s communication plan, promote local teams, and develop specific promotional campaigns when an international match comes to the stadium targeting local and satellite fans. Using the team logo and colours in marketing communications and including details about the team’s history, star players, team-related social events, or concessions (see ) in the stadium and surrounding area may bolster the city’s image as a destination – especially given the mediating role of team brand image on the association between the visitor experience and destination image.

Despite the positive relationship between visitors’ experiences and satisfaction, the latter element was found to adversely affect destination image. However, the magnitude of this path coefficient (i.e. satisfaction – destination image) was quite low. The significant effects were likely due to the large sample size, rendering this relationship meaningless from a practical standpoint (Cohen, Citation1988). The path coefficient from satisfaction to destination image revealed that less than 1% of the variance in destination image could be uniquely attributed to overall satisfaction perceptions. As attracting visitors is part of the efforts of any destination marketers (Heere et al., Citation2019), developing strategies that focus exclusively on this relationship may result in unnecessary financial investment and be misleading for stadium, destination and leisure managers. Instead, efforts intended to generate benefits for the city (i.e. destination image) should be spurred by focusing on positive stadium visitor experiences and a better team brand image. Relevant initiatives will be advantageous for the team (i.e. favourable brand image) through increased consumer satisfaction with stadium visits.

In sum, this work offers several valuable insights around cultivating a positive team brand image and a positive destination image from sport stadium visitors’ points of view. Sport stadium managers should keep in mind that a team’s brand image is positively influenced by the stadium visitor experience and subsequent satisfaction. For city and leisure marketers, the stadium visitor experience is vital to developing a strong perception of the city as a destination, with the team’s brand image also playing a role. Close coordination between stadium and host destination marketers could transform the team’s brand into the city’s cultural brand to foster the connection between the sport stadium and destination image. The sport stadium could be shaped by, contribute to, or even form the destination image and the city’s cultural environment. Additionally, a positive stadium experience will help cultivate a positive team brand image and perceptions of the city as an appealing destination. Yet satisfaction with the stadium experience could also generate benefits for the team (i.e. better brand image) without necessarily being advantageous for the city (i.e. no link to destination image). These findings bolster the literature on destination image (e.g. Lugosi & Walls, Citation2013; Pike et al., Citation2019), consumer satisfaction (e.g. Oliver, Citation1993; Yoshida & James, Citation2010) and brand spillover effects (e.g. Pritchard et al., Citation2020; Su & Kunkel, Citation2019) by showing that experience is of differential importance for service providers (teams) and associated entities (cities). In essence, although increased visitor satisfaction is crucial for service providers, corresponding benefits do not seem to transfer to related entities.

5.1. Limitations and future research

Several limitations of this study may have influenced our findings and should be considered in future research. First, only 17 European stadiums that hosted the UEFA Champions League final were considered, limiting results’ generalisability to other sport stadiums and cities. Subsequent work should expand the sample size and explore different sport stadiums’ impacts in promoting their respective cities – particularly when cities host more than one major team (Madrid, Spain: Real Madrid Club de Fútbol & Club Atlético de Madrid; London: Chelsea FC, Arsenal FC, Crystal Palace FC, Queen Park Rangers FC, Fulham FC, Tottenham Hotspur FC, & West Ham United FC). The 17 stadiums chosen for this study were in cities featuring a strong tourism dynamic (e.g. Milan, Lisbon, and London). In the future, scholars could investigate stadiums’ effects in cities with less global appeal. Selected stadiums also differed in their age, degree of innovation, and services provided; additional studies are needed to more clearly delineate differences among these variables. Findings will enhance the understanding of stadiums’ roles on teams and cities.

Second, although the adopted dictionary was validated based on input from an independent expert panel, caution is necessary when interpreting the results; dictionary definitions may be influenced by human bias. Third, all data were gathered from TripAdvisor. Therefore, it was impossible to fully disaggregate a guest’s review about a visit within a specific game event context, about a supplementary service (e.g. club’s museum), or about a tour outside an event. As many stadiums are now multipurpose venues that market a number of sub-brands in addition to sport events (Pritchard et al., Citation2020), disentangling these services may be easier for some stadiums than for others. For example, while a guided visit tour of FC Barcelona’s Camp Nou has its own TripAdvisor page that is separate from the main Camp Nou page, this may not be the case for all stadium sub-brands. Thus, the adoption of ‘review express solicitation’ (i.e. solicited reviews by the host organisation) for each stadium-related experience (Litvin & Sobel, Citation2019) may help better understanding of how stadium visits favour both team and host city. Also, although secondary data from online platforms entail big data (Moro et al., Citation2019) and can offer a comprehensive perspective based on a large visitor sample, a dataset is ultimately limited to the features available on a given social media platform. Studies integrating secondary data from social media with primary data (e.g. interviews and questionnaires) may lead to more fruitful conclusions. Finally, in light of transformation of city visitors’ behavioural patterns derived from COVID-19 (Li et al., Citation2020), future research could examine how the new safety measures implemented in sport stadiums influence destination image. Similarly, empirically examining how the growth of stadium tours (e.g. Juventus, Citation2021) impact individuals’ perception of the city would represent a research opportunity to aid managing destination image and associated leisure strategies.

6. Conclusion

This study combined a text mining approach with a structural model to explore the relationships among sport stadium visits, team brand image, visitor satisfaction, and destination image. Results indicate that the visitor experience is vital to enhancing both a team’s brand image and the city’s destination image. Consumer satisfaction was found to partially mediate the relationship between the visitor experience and team brand image but not destination image. In addition, a positive team brand image can spill over to the city in the form of a positive destination image. These outcomes offer stadium and destination image and leisure managers actionable suggestions regarding how to leverage football stadiums to benefit the team and the host city, such as the importance to the provision of stadium pre-visit information, investment in external stadium accessibility, supplementary match events, as well al as the reinforcement of the team-city link in the marketing communications, or the creation of virtual touristic experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). The brand relationship spectrum: the key to the brand architecture challenge. California Management Review, 42(4), 8–23. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/000812560004200401?casa_token=u5n0OnXFnUsAAAAA:IdN681xNq1zB92x7TTAra2hYlv_fD_eYsq1y2loSjPmEHMcn0SdsoYmgBiKAuTsVd-TbzH4E1r8maKM

- Agha, N. (2013). The economic impact of stadiums and teams. Journal of Sports Economics, 14(3), 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002511422939

- Andersson, S., Bengtsson, L., & Svensson, Å. (2021). Mega-sport football events’ influence on destination images: A study of the of 2016 UEFA European football championship in France, the 2018 FIFA world cup in Russia, and the 2022 FIFA world cup in qatar. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100536

- BBC. (2021). Everton’s bramley-moore dock stadium given council approval. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-merseyside-56167487

- Berry, L. (2000). Cultivating service brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300281012

- Beverland, M., Eckhardt, G., Sands, S., & Shankar, A. (2021). How brands craft national identity. The Journal of Consumer Research, 48(4), 586–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa062

- Beverland, M., & Farrelly, F. (2010). The quest for authenticity in consumption: consumers’ purposive choice of authentic cues to shape experienced outcomes. The Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1086/615047

- Bigne, E., Ruiz, C., & Curras-Perez, R. (2019). Destination appeal through digitalized comments. Journal of Business Research, 101, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.020

- Biscaia, R., Ross, S., Yoshida, M., Correia, A., Rosado, A., & Marôco, J. (2016). Investigating the role of fan club membership on perceptions of team brand equity in football. Sport Management Review, 19(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.02.001

- Biscaia, R., Trail, G., Ross, S., & Yoshida, M. (2017). A model bridging team brand experience and sponsorship brand experience. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 18(4), 380–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-07-2016-0038

- Biscaia, R., Yoshida, M., & Kim, Y. (2021). Service quality and its effects on consumer outcomes: A meta-analytic review in spectator sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1938630

- Byon, K., Zhang, J., & Baker, T. (2013). Impact of core and peripheral service quality on consumption behavior of professional team sport spectators as mediated by perceived value. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(2), 232–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.767278

- Cadotte, E., Woodruff, R., & Jenkins, R. (1987). Expectations and norms in models of consumer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378702400307

- Cenfetelli, & Bassellier (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 33(4), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650323

- Chang, M.-X., Choong, Y.-O., Ng, L.-P., & Seow, A.-N. (2021). The importance of support for sport tourism development among local residents: The mediating role of the perceived impacts of sport tourism. Leisure Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.2011950

- Chick, G., Dong, E., Yeh, C.-K., & Hsieh, C.-M. (2021). Cultural consonance predicts leisure satisfaction in taiwan. Leisure Studies, 40(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1808052

- Cho, H., Chiu, W., & Tan, X. D. (2021). Travel overseas for a game: The effect of nostalgia on satellite fans’ psychological commitment, subjective well-being, and travel intention. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), 1418–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1792857

- Cho, H., Khoo, E., & Lee, H.-W. (2019). Nostalgia, motivation, and intention for international football stadium tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(9), 912–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1653339

- Cobbs, J., Groza, M., & Rich, G. (2015). Brand spillover effects within a sponsor portfolio: The interaction of image congruence and porfolio size. Marketing Management Journal, 2(2), 107–122.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cordina, R., Gannon, M., & Croall, R. (2019). Over and over: Local fans and spectator sport tourist engagement. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7–8), 590–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1534962

- Datta, H., Ailawadi, K., & van Heerde, H. (2017). How well does consumer-based brand equity align with sales-based brand equity and marketing-mix response? Journal of Marketing, 81(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0340

- Deloitte. (2020). Eye on the price: Football money league. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/sports-business-group/deloitte-uk-deloitte-football-money-league-2020.pdf

- Efron, B. (1987). Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82(397), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1987.10478410

- Fernandes, T., & Fernandes, F. (2018). Sharing dissatisfaction online: analyzing the nature and predictors of hotel guests negative reviews. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 27(2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2017.1337540

- Finn, A., & Wang, L. (2014). Formative vs. reflective measures: facets of variation. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2821–2826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.001

- Furtado, A., Ramos, R., Maia, B., & Costa, J. (2022). Predictors of hotel clients’ satisfaction in the cape verde islands. Sustainability, 14(5), 2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052677

- Gehlbach, H., & Barge, S. (2012). Anchoring and adjusting in questionnaire responses. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(5), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.711691

- Ginesta, X. (2017). The business of stadia: maximizing the use of spanish football venues. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(4), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358416646608

- Ginesta, X., & Eugenio, J. (2014). The use of football as a country branding strategy. Case Study: Case Study: Communication & Sport, 2(3), 225–241.

- Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (2004). The globalization of football: A study in the glocalization of the ’serious life’. The British Journal of Sociology, 55(4), 545–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00037.x

- Hair, J., Risher, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Heere, B., Walker, M., Yoshida, M., Ko, Y. J., Jordan, J., & James, J. (2011). Brand community development through associated communities: Grounding community measurement within social identity theory. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(4), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190404

- Heere, B., Wear, H., Jones, A., Breitbarth, T., Xing, X., Salcines, J., Yoshida, M., & Derom, I. (2019). Inducing destination images among international audiences: the differing effects of promoting sport events on the destination image of a city around the world. Journal of Sport Management, 33(6), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0101

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing (pp. 277–319). https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Horbel, C., Popp, B., Woratschek, H., & Wilson, B. (2016). How context shapes value co-creation: Spectator experience of sport events. The Service Industries Journal, 36(11–12), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2016.1255730

- Humphreys, C. (2019). The city of sport: London’s stadiums as visitor attractions. In Smith, A., & Graham, A. (Eds.), Destination London: The expansion of the visitor economy (pp. 91–116). University of Westminster Press. https://doi.org/10.16997/book35

- Itani, O., & Hollebeek, L. (2021). Light at the end of the tunnel: visitors’ virtual reality (versus in-person) attraction site tour-related behavioral intentions during and post-COVID-19. Tourism Management, 84, 104290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104290

- Jansen-Verbeke, M., & van Rekom, J. (1996). Scanning museum visitors: urban tourism marketing. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00076-3

- Jeong, Y., & Kim, S. (2019). A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(4), 940–960.

- Jiang, Y., Ramkissoon, H., Mavondo, F., & Feng, S. (2017). Authenticity: the link between destination image and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 26(2), 105–124.

- Juventus. (2021). Virtual tour. Juventus.Com. https://www.juventus.com/en/allianz-stadium/directions-access/virtual-tour/

- Kaplanidou, K., Jordan, J., Funk, D., & Ridinger, L. (2012). Recurring sport events and destination image perceptions: Impact on active sport tourist behavioral intentions and place attachment. Journal of Sport Management, 26(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.3.237

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Kempiak, J., Hollywood, L., Bolan, P., & McMahon-Beattie, U. (2017). The heritage tourist: An understanding of the visitor experience at heritage attractions. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 23(4), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1277776

- Kerr, A., & Gladden, J. (2008). Extending the understanding of professional team brand equity to the global marketplace. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 3(1/2), 58. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2008.015961

- Kharouf, H., Biscaia, R., Garcia-Perez, A., & Hickman, E. (2020). Understanding online event experience: the importance of communication, engagement and interaction. Journal of Business Research, 121, 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.037

- Kim, J., Magnusen, M., & Kim, Y. (2014). A critical review of theoretical and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research and recommendations for future sport marketing scholarship. Journal of Sport Management, 28(3), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0084

- Kunkel, T., & Biscaia, R. (2020). Sport brands: brand relationships and consumer behavior. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.291.032020.01

- Kunkel, T., Biscaia, R., Arai, A., & Agyemang, K. (2020). The role of self-brand connection on the relationship between athlete brand image and fan outcomes. Journal of Sport Management, 34(3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0222

- Kunkel, T., Doyle, J., & Funk, D. (2014). Exploring sport brand development strategies to strengthen consumer involvement with the product – the case of the australian A-league. Sport Management Review, 17(4), 470–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.01.004

- Kunkel, T., Funk, D., & Lock, D. (2017). The effect of league brand on the relationship between the team brand and behavioral intentions: A formative approach examining brand associations and brand relationships. Journal of Sport Management, 31(4), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0166

- Lee, C. W. (2022). Watching the FIFA world cup under cosmopolitanisation: How football fans in hong kong followed the 2018 world cup. Leisure Studies, 41(4), 587–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.2022180

- Leeuwen, L., Quick, S., & Daniel, K. (2002). The sport spectator satisfaction model: A conceptual framework for understanding the satisfaction of spectators. Sport Management Review, 5(2), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(02)70063-6

- Lei, J., Dawar, N., & Lemmink, J. (2008). Negative spillover in brand portfolios: Exploring the antecedents of asymmetric effects. Journal of Marketing, 72(3), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/JMKG.72.3.111

- Litvin, S., & Sobel, R. (2019). Organic versus solicited hotel TripAdvisor reviews: measuring their respective characteristics. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 60(4), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965518811287

- Li, Z., Zhang, S., Liu, X., Kozak, M., & Wen, J. (2020). Seeing the invisible hand: underlying effects of COVID-19 on tourists’ behavioral patterns. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100502

- Lugosi, P., & Walls, A. (2013). Researching destination experiences: themes, perspectives and challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 51–58.

- Marca. (2018). Florentino Perez: New stadium will generate 150m euros of revenue each year. Marca. https://www.marca.com/en/football/real-madrid/2018/09/23/5ba77d0f268e3e67118b4591.html

- Mitten, A. (2017). Are FC barcelona a football club or a tourist attraction? GQ Magazine. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/are-fc-barcelona-a-football-club-or-a-tourist-attraction

- Moro, S., Esmerado, J., Ramos, P., & Alturas, B. (2019). Evaluating a guest satisfaction model through data mining. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(4), 1523–1538. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2019-0280

- Moro, S., & Rita, P. (2018). Brand strategies in social media in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2016-0340

- Nelson, V. (2021). Consuming local: Product, place, and experience in visitor reviews of urban texas craft breweries. Leisure Studies, 40(4), 480–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1831044

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864.

- Oliver, R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. The Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/209358

- Pan, X., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2021). Investigating tourist destination choice: effect of destination image from social network members. Tourism Management, 83, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104217

- Papadimitriou, D., Apostolopoulou, A., & Kaplanidou, K. (2016). Participant-based brand image perceptions of international sport events: the case of the universiade. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 17(1), 1–20.

- Pike, S., Jin, H., & Kotsi, F. (2019). There is nothing so practical as good theory for tracking destination image over time. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 14, 100387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100387

- Piramanayagam, S., Rathore, S., & Seal, P. (2020). Destination image, visitor experience, and behavioural intention at heritage centre. Anatolia, 31(2), 211–228.

- Premier_League. (2019). Premier League Economic and Social Impact. https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/pt_br/topics/ey-economic-advisory-/ey-premier-league-economic-and-social-impact-january-2019.pdf

- Pritchard, A., Cook, D., Jones, A., Bason, T., & Salisbury, P. (2020). Building a brand portfolio: The case of English Football League (EFL) clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(3), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1802501

- Ramshaw, G., Gammon, S., & Huang, W.-J. (2013). Acquired pasts and the commodification of borrowed heritage: The case of the bank of america stadium tour. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 18(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2013.799334

- Ribeiro, T., Correia, A., Biscaia, R., & Figueiredo, C. (2018). Examining service quality and social impact perceptions of the 2016 rio de janeiro olympic games. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 19(2), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-08-2017-0080

- Richards, J., O’Shea, M., Spanjaard, D., & Garlin, F. (2021). ‘You can rent it for a while, but it is our house’: sports fans’ experience of returning ‘home’ to a new multipurpose stadium. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(7), 981–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220968570

- Richter, N., Schubring, S., Hauff, S., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2020). When predictors of outcomes are necessary: Guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(12), 2243–2267.

- Ross, S. (2006). A conceptual framework for understanding spectator-based brand equity. Journal of Sport Management, 20(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.1.22

- Ross, S., James, J., & Vargas, P. (2006). Development of a scale to measure team brand associations in professional sport. Journal of Sport Management, 20(2), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.2.260

- Ruiz-Real, J., Uribe-Toril, J., & Gázquez-Abad, J. (2020). Destination branding: opportunities and new challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100453

- Rust, R. T., & Oliver, R. L. (1994). Service quality: Insights and managerial implications from the frontier. In R. T. Rust & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Service quality: New directions in theory and practice (pp. 1–20). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Salas-Olmedo, M., Moya-Gómez, B., García-Palomares, J., & Gutiérrez, J. (2018). Tourists’ digital footprint in cities: Comparing Big Data sources. Tourism Management, 66, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.11.001

- Su, Y., & Kunkel, T. (2019). Beyond brand fit. The influence of brand contribution on the relationship between service brand alliances and their parent brands. Journal of Service Management, 30(2), 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2018-0052

- Tansey, J. (2013). Qatar 2022: taking a look at the stadia set to break the mold in the middle east. Bleacherreport. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1581217-qatar-2022-taking-a-look-at-the-stadia-set-to-break-the-mold-in-the-middle-east

- UEFA. (2021). 2020 champions league final: When and where. UEFA. https://www.uefa.com/uefachampionsleague/news/025a-0ea4b8fec98a-b6eb8a2ae892-1000–2020-champions-league-final/

- UEFA. (2021b). UEFA stadium infrastructure regulations. Documents UEFA. https://documents.uefa.com/r/qA7fJuXrAU7K42UpVsoDGQ/wMPWZHFyalpUYu5yBvu6rg

- Uhrich, S., & Benkenstein, M. (2012). Physical and social atmospheric effects in hedonic service consumption: Customers’ roles at sporting events. The Service Industries Journal, 32(11), 1741–1757.

- Uvinha, R. R., Romano, F. S., & Wise, N. (2020). Sporting heritage and touristic transformation: Pacaembu stadium and the football museum in São Paulo, Brazil. In T. Wise, & N. Jimura (Eds.), Tourism, cultural heritage and urban regeneration (pp. 57–69). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41905-9_4

- VisitBritain. (2019). International buzzseekers football research. https://www.visitbritain.org/sites/default/files/vb-corporate/Documents-Library/documents/foresight_169_-_football_tourism.pdf

- Wang, C., & Hsu, M. (2010). The relationships of destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: an integrated model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 27(8), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2010.527249

- Wolter, J., Bock, D., Smith, J., & Cronin, J. (2017). Creating ultimate customer loyalty through loyalty conviction and customer-company identification. Journal of Retailing, 93(4), 458–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2017.08.004

- Woratschek, H., Horbel, C., & Popp, B. (2020). Determining customer satisfaction and loyalty from a value co-creation perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 40(11–12), 777–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1606213

- Yoshida, M. (2017). Consumer experience quality: A review and extension of the sport management literature. Sport Management Review, 20(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.01.002

- Yoshida, M., & James, J. D. (2010). Customer satisfaction with game and service experiences: antecedents and consequences. Journal of Sport Management, 24(3), 338–361. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.24.3.338