ABSTRACT

Santa agricultural area is a key production site for crops in Cameroon. This study aimed to look at the risk factors, knowledge and health implications of water pollution across 10 villages, in the area: 140 water points were visited and questionnaires randomly administered to water users, while health data were collected from the two local hospitals. Water sources are tap, stream, rain, well and spring and the water is used for agriculture, domestic activities, hygiene and sanitation. Pesticide pollution was illustrated by activities such as spraying, mixing and management of waste containers and purification methods are chlorination, boiling, sedimentation, filtration and refrigeration. Waterborne diseases are cholera, typhoid (the most prevalent), diarrhea, dysentery and skin diseases. Many water sources are close to toilets, farms and dumping sites. We found that 75% of respondents were not satisfied with the quality of water. Our results will be interest for water management, and to educate users on the risks linked to current practices.

KEYWORDS:

Editor S. Archfield Associate editor K. Soulis

Introduction

Large and growing populations exert increasing pressure on natural water and soil resources (Asian Water Development Outlook Citation2007). A correlation has been established between human population size, crops and animal production and demand for natural resources (Velis et al. Citation2017). In most cases, water is supplied to the community in restricted quantity and time, due to seasonal variations; the source of water supplies globally is generally a river where flows vary with rainfall (Belhassan Citation2011, Lee and Schwab Citation2005). Intensive demands and exploitation of water are growing because of climatic changes (Soden Citation2000, Expósito et al. Citation2010). The need to protect surface water and, more importantly, groundwater resources against quality deterioration becomes urgent as the population continuously looks for potable water (Dai and Trenberth Citation2002). Statistics from UNESCO (Citation2016) indicate that Africa has about 9% of the world’s freshwater resources versus 11% of the world’s population.

Agriculture in Cameroon is mostly based on rainfall fed farming and less than 10% of its cultivated land is irrigated during the dry season (Velis et al. Citation2017). According to the latter, there is short-term scarcity and conflict is generally observed among users: primarily grazers and farmers (Manu et al. Citation2014, Andre et al., Citation2013).

Access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene has become a challenge (Svendsen et al. Citation2009, Amrita et al. Citation2010). Many people use water to meet their everyday needs, for example in practicing cropping, rearing, sanitation, mixing agrochemical products and cooking (Hladíková et al. Citation2015, Sonchieu et al. Citation2017). According to the African Ministers’ Council on Water (AMCOW Citation2015), water supply in the whole country concerns four major sectors: rural water supply, urban water supply, rural sanitation and hygiene and urban sanitation and hygiene. This inter-ministerial council also estimated the total water supply at 102 USD million/year, while the total sanitation need is estimated at 16 USD million/year. This is a great challenge for the whole population, since Cameroon is classified among low income countries (WHO Citation2013, Amrita et al. 2010).

In this context water has been involved in various diseases, which are classified into different categories: waterborne, water-related, excreta-related, water collection and storage, and toxin-related (Montgomery and Elimalech Citation2007). Improving access to potable water and safe sanitation seems to be the most effective means to improve public health and sustain development, as mentioned by Nerkar et al. (Citation2015). So care given to water resources depends on the ability of users to manage the common resource for respective uses and satisfaction.

Farmers are more directly involved in the processes of water system management in rural areas where modern agriculture is gradually taking place. According to the African Development Fund (ADF Citation2000), water supplied from the same source will serve as drinking water, as well as collective sanitation in urban and rural communities, agricultural activities and public buildings. Zephania (Citation2014) and Velis et al. (Citation2017) observed diverse water sources in the Santa area: in-house tap connections, public or private wells, taps, water vendors, tank trucks, provided by neighbours or collected from rivers, streams or lakes. In this area, there is a growing pressure on natural resources in general (soil, water, flora and fauna) (Kometa Citation2013). Sonchieu et al. (Citation2017) and Pouokam et al. (Citation2017) have observed pesticide misuse by farmers who are less knowledgeable in pesticide application. Since water runoff will carry residues of applied pesticides and spread them across an area, there may be a risk of high water pollution (Albert et al. Citation2018).

Taking into consideration that there is no established water-treatment system in the locality, the entire population depends on water from rivers (PNDP Citation2015). This may lead to serious exploitation of the resource. Beside these risk factors, there is no education on water-treatment techniques for common people (Albani and Ibrahim Citation2019). According to the African Ministers’ Council on Water (AMCOW (African Ministers’ Council on Water) Citation2015), little communication on water purification techniques is given generally during prenatal visits to pregnant women. Considering the many lapses observed among famers (in terms of care of the water resource, e.g. mixing chemicals and utensils), it is likely they are not aware of risks linked to water pollution from the agrochemicals they use. The main objective of this study is to provide information on water sources, use, risk factors and the consequences for the population of the Santa area. Specifically, our study aimed to evaluate the knowledge of water users, the way the water sources are managed and the health implications for users in the Santa agricultural zone. Many questions can be asked in this context: How are activities being carried out around each water point? What precautions do users take to preserve the quality of water when carrying out their activities? And how many cases of waterborne diseases have been reported in local hospitals? The data collected will be used to develop a project to be submitted to the National Community-Driven Participatory Programme, the national organ in charge of socio-economic development by local councils in diverse domains, such as sanitation, health and rural development.

Material and methods

Description of the study area

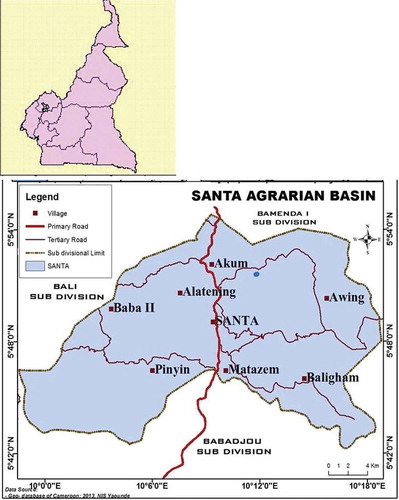

Santa is one of the seven sub-divisions in Mezam Division, North-West Region, Cameroon, and is located between 5°42′–5°53′N and 9°58′–10°18′E (Ngwa Citation2001). The area includes 10 villages distributed as follows () (the numbers in parentheses indicate the number of samples collected): Mbu (8), Akum (25), Pinyin (20), Mbei (9), Awing (18), Alatening (8), Baligham (12), Ndzong (5), Matazem (6), and Santa (29)(Kometa Citation2013. Zephania Citation2014). About 90% of the population is dependent on agriculture, practicing either livestock or crop cultivation. According to information collected from the Delegation of Agriculture, about 823 people have cropping as their main activity. The main crops cultivated, as listed by Sonchieu et al. (Citation2017), were vegetables, fruits, cereals, tubers and roots. A village can be dedicated to cultivating a major crop, such as Pinyin where only vegetables are grown.

Figure 1. Map of the study area, Santa basin in North-West Region, Cameroon. Source:.Ngwa (Citation2001)

The Santa agricultural area shows a wide variety in its relief, with altitudes ranging from 1300 m a.s.l, in Baligham and Awing to about 2600 m a.s.l. at the boundary with Wabane Sub-division. The main water sources include several rivers, streams and springs that characterize the area, most of which are temporary; they flow during the rainy season, with waterfalls on some of the mountain slopes during the rainy season and dry out during the dry season. There is a watershed at Mile 11 Lake, a major crater lake. Severe fog around the hills in the area of the Alatening Road is believed to

be due to the influence of the lake Awing.

According to the council development plan (PNDP (Plan National de Développement et Planification) Citation2015), the land use of the area (clayey and ferralitic soils) is characterized by mixed cropping. Crops cultivated are maize, beans, rice, oil palms, groundnuts, coffee, tubers, vegetables and fruits, with potential cultivation of cattle pasture reserves, i.e. open fields. The pasture zone includes vegetation (trees, shrubs, grass); livestock (cattle, small ruminants, asses, horses); forest areas (for fuel wood exploitation, fishing, harvesting of medicinal plants (barks, roots) and small-scale hunting; water bodies/rivers (cattle watering points, construction of houses, domestic use, fishing and agriculture, with a potential of drinking and agricultural production; and protected areas (sacred forest, water catchment sites, hunting and forest exploitation).

Road construction and construction of houses constitute another form of land use. The only industrial activity in this area is the construction of two cattle crushes at the grazing zones in Ntara and Bangfon. A sprinkling system has been developed in the Council area for irrigating farmlands during the offseason. This technology is developed based on the landscape.

The demand for water is high: PNDP (Citation2015) mentioned an inadequate supply of water, with less than 5% of households being connected to the community water supply. Of the 297 taps counted for the whole Santa Sub-division, 141 are not used

Data collection

The study was carried out in two stages: the first step consisted of distributing questionnaires at 140 water sources across the 10 villages (number of sources in parentheses): Mbu (8), Akum (25), Pinyin (20), Mbei (9), Awing (18), Alatening (8), Baligham (12), Ndzong (5), Matazem (6), and Santa (29). Questionnaires were distributed according to the number of water points found in each village and were administered to persons randomly selected among those met on the spot for interview and questionnaire filling. Questions focused on the farmer’s demographic data (gender, age, level of education), water resource used, and their perception and health implications. The second stage was based on collection of secondary data, which consisted on investigating the prevalence of waterborne and related diseases in two main local hospitals – Santa District Hospital and the Holy Family Medical Centre, Akum – which were chosen according to the number of patients consulted daily and their efficacy.

Water quality examination

The distance between water sources and a toilet, the types of water users and the activities carried out around the water points were also assessed in the different areas investigated. Activities considered were items washed, farming activities (pesticide preparation, pesticide spraying, both around the source and washing of spraying materials), defecating and dumping. Use of water was based on the following: common use of water by inhabitants and animals, and purification techniques (boiling, chlorination, filtration and sedimentation). Finally, the cleanliness based on suspended particles, sediments, cloudiness and muddiness of the water was assessed, as well as the cleanliness of the surroundings of the water source.

Results and discussion

Demographic characteristics

provides details of the gender distribution among respondents (50% M/F). It may also be seen from that 30% of respondents were aged between 20 and 29 years, while less than 20% were between 30 and 49 years old. Their occupation varies (farmers, civil servants, traders and others, such as students and mechanics), but all the people surveyed practice farming as a main or secondary activity. The most represented group of respondents were typically farmers (29%). The level of education indicates that the respondents mostly held qualifications up to General Certificate of Education (GCE) “O-level” (UK school exam, taken at age 15–16), but most were between various educational levels and the difference varied (21–29%). So, the water sources are equally used by all users independently of the gender, occupation and level of education.

Table 1. Demographic data for the study area.

Water use

Sources of water and involved activities

Water sources vary in the Santa agricultural area (), comprising: taps, streams, rain, wells and springs. Streams are generally used to connect households with tap water, with rainwater increasing the water flow. Thus, taps and streams are the most used. Rainwater, wells and springs are equally used by farmers. These sources are used for many activities, as shown in . These include washing, dumping, defecating, farming and drinking. However, washing and farming dominated at 63% and 56%, respectively.

Table 2. Activities around water source and purification.

Uses of collected water

The users can exploit the same source for various activities that can be grouped into four distinct domains: agriculture (dilution of chemicals, irrigation, feed/wash animal, washing farm utensils and farm produce); domestic (cooking and washing); hygiene and sanitation (bathing, drinking) and other activities (mopping, building construction). Drinking, cooking, bathing are the most frequent activities (94%, 80% and 90%, respectively) (). Some risky activities, such as mixing chemicals or washing pesticides operating materials, are noticeable but at low frequency (44%). This shows that the same water point is shared between animals (water contamination) and humans leading to a possible conflict between users.

Water treatment

shows that water collected on the 140 water points investigated may or may not be treated by consumers using various methods, such as chlorination, boiling, sedimentation, filtration and refrigeration. About 70% of respondents declared that they do not always treat their water before drinking. However, the most used method remains boiling (61%), while separation methods (filtration and sedimentation) remain poorly applied. Chlorination is not the least applied technique since it is frequently used by 23% of persons interviewed. Refrigeration, thought in the community to be a purification method of water, is the least applied technique (3%) at the same level as filtration. Results from data collected indicate that purification methods are poorly applied, since up to 70% of the people do not treat water before drinking.

Pesticide use around water sources

The use of pesticides has been mentioned by many authors, `. Sonchieu et al. (Citation2017) and Pouokam et al. (Citation2017), who provided lists of the pesticides in use. indicates the risks inherent in pesticide use. For example, all those who spray pesticides frequently wash their knapsacks in the river and prepare the formulation around the water source. Furthermore, 94% of sampled farmers wash their personal protective clothing in the stream and bathe in the river. also shows that 21% of respondents throw emptied pesticide containers in the water course. Also, containers abandoned in the farms will be washed by rainwater that subsequently pollutes streams/rivers. Thus, these water polluting factors can be estimated at 73%.

Table 3. Water contamination by pesticide-related handling. PPC: personal protective clothing.

Health implications

presents the prevalence of some waterborne or related diseases recorded in Santa agricultural area. Among the respondents met at the 140 water points, many reported to have contracted waterborne diseases like cholera, typhoid, diarrhoea, amoebiasis (dysentery) and skin disease. The most frequent diseases are typhoid and diarrhoea, which have been experienced by 43% and 36% of respondents, respectively. Two cases of cholera were signalled by one person (1%), while 100 persons declared that they have contracted at least one of the above diseases at least once per year. Cases of sickness happen regularly to 32% of people sampled, while 35% faced illness only once a year. Among them, 60% drink stream water on a daily basis, whereas 29% drink tap, well or spring water on the same basis. The remaining 11% do not have a precise source of drinking water.

Table 4. Prevalence of waterborne diseases.

Statistics collected from the two community hospitals during the year of investigation (i.e. 361 cases of waterborne diseases in 2016) indicate that the highest frequency is typhoid (209 cases), while skin rashes, diarrhoea and gastroenteritis are less recorded (10, 10 and 32 cases, respectively).

Risk of contamination and perceptions

Water source care: hygiene and sanitation

indicates the evaluated factors: cleanliness of surroundings, cleanliness of the water, proximity to toilet, proximity to dumping site, proximity to cultivated farms and protection of water source.

Table 5. Protection of water source and respondents’ perception.

These factors, used as indicators to evaluate the cleanliness of surroundings show that water points were 70% grassy and 73% dirty, or both in most cases. Only 14% were clean, while 64% were close to a dumping point. The cleanliness of water itself was observed at 48% with suspended particles, while many were described as muddy (22%). Only 1% of the visited water points showed clear appearance of the water.

In terms of proximity to a toilet, 70% were very far and 10% closest. However, 50% of visited water sources were very close to dumping points or served as a dumping site. But the environment did not show any guarantee for safety due to activities conducted around the water source. Considering the location of water points close to farms, 75% were inside cultivated areas. It was almost impossible to find water sources far from cultivated areas. This situation is emphasized with the care given by users: 79% do not care about the safety of the water source. Little care is given either by individuals or working as a community. So, care given to the water itself and the water source is done using various methods which are applied almost equally with no preference.

Perception and satisfaction for quality of water

Perception and satisfaction of the quality of water () demonstrates that 75% of respondents are not satisfied, while some are indifferent and others declared to be satisfied (14% and 11%, respectively). This is emphasized by their appreciation of the appearance (colour, presence of particles and/or living organisms), since 75% of the respondents think that the water they fetch is impure. But some estimated that it is good for drinking and domestic purposes because of its cleanliness. So, people declare their indignation on the quality of water they consume, but there is no indication from local authorities to supply potable water to the community.

Discussion

The members of the population met during this survey comprised mostly young people because of the intensive agricultural activities carried out in the zone. This was also observed by Sonchieu et al. (Citation2017) and Pouokam et al. (Citation2017) concerning pesticide use, which was intensively applied by young workers. The responses from all genders explained the desire to improve the family income, as was studied in depth by Zephania (Citation2014) and Kometa (Citation2013).

The activities carried out around the water sources are normal. The use of the same site for many activities, such as mixing chemicals, washing of various used materials and other items, dumping, defecating, farming and drinking, is very common as each individual has a different concern. But some unhygienic activities, such as defecating and dumping, have become more dangerous for other users as they may be a source of contamination and disease transmission from a sick person to healthy one (Yates et al. Citation2015). Washing concerns all washable working materials used during farming and at home and bathing, which, at times, is done at shared water sources. The contamination of water will then be obvious and aquatic fauna will be affected since all the water runoff will be directed towards the watercourse (Albert et al. Citation2018). The risk becomes high in the sense that the same water polluted upstream will be drunk downstream. This activity can contaminate or facilitate contamination, depending on the pathway of cross-contamination. Some people even drink the water with no previous treatment, which may favour the progress of some waterborne or water-related diseases (Nerkar et al. Citation2015).

The use of water also implies farming related activities with the application of agrochemicals (pesticides, fertilizers, growers) which are known to be hazardous. Most dangerous activities carried out are mixing and spraying of pesticides in or around the water source and washing used materials in the source itself. Cropping is the main activity carried out in the area and the practices will surely affect people using the same water source, or elsewhere, since agrochemicals used can be transported for long distances (Albert et al. Citation2018). Sonchieu et al. (Citation2017, Citation2018)) and Pouokam et al. (Citation2017) observed a misuse of pesticides on crops and its incidence among populations (sellers and farmers). They listed various toxicity classes of pesticides used in the same area. The risk is then extended to the water commonly used, which is obviously exposed to contamination because of domestic exploitation. This can then affect the direct user and indirectly the consumer in the form of residues (Tanga Citation2014). It will also enter the body using different routes (skin, mouth, nostrils and eyes) which maybe irritated (Li and Jennings Citation2017). Other activities such as irrigation, which is mostly done during the dry season, will create stronger competition for water around the seasonally resistant sources.

To limit the risks observed, some users apply different techniques to remove contaminant from their water before drinking, or for other use such as beverage preparation. The very common methods of purification are boiling, filtering, chlorination and sedimentation. However, poor knowledge of some users induces them to consider refrigeration as a method of water purification. Simple methods such as multi-barrier approach (source protection, sedimentation, filtration, disinfection and safe storage) promoted by WHO, are completely ignored by respondents (CAWST Citation2011, WHO (World Health Organization) Citation2013). Methods like solar disinfection are completely ignored too. It is evident that chemicals used in the area will not be removed, since no indication shows removal of chemical contaminants, except sedimentation which can coagulate some of them (UNICEF Citation2014). The risk of developing long-term non-communicable disease becomes high and intoxication cases will arise. Sonchieu et al. (Citation2018) reported that many pesticide related poisoning cases were registered from this area, which might have been avoided with good care of the water sources (Wang et al. Citation2013).

Some waterborne or water-related diseases, such as cholera, typhoid, diarrhoea, dysentery and skin irritation, were reported by respondents who were repeatedly victims. These diseases are linked to microbes, but skin itching could also be attributed to pesticide action (Damalas and Koutroubas Citation2016). In addition, the two local hospitals registered a huge number of people suffering from typhoid; this shows their poor knowledge of water treatment and care of water sources. This is not limited to the immediate use of water but also concerns water point care, since the investigated population pays little attention to water, sanitation and hygiene.

The proximity of dumping sites, unhygienic conditions in the environment and the proximity to farms and toilets, in some cases, will be responsible for more water contamination (Burch and Thomas Citation1998). Despite this alarming situation, many people in the area are ignorant about the water quality and care required before consumption; they felt satisfied by the quality of water they use. This ignorance was manifested at the contamination source (chemicals use). Consumption of contaminated water will certainly lead to the development of many non-communicable diseases related to long exposure, due to constant occupational conditions (Lee and Schwab Citation2005). Many systems have been developed that can be used to preserve the health of the population (Nguyen-Viet et al. Citation2009, WHO (World Health Organization) Citation2013, Loeb et al. Citation2016, Velis et al. Citation2017). The cost has been estimated to be affordable for individuals (McGinnis et al. Citation2017).

It is now clear that water points are used for almost all activities, confirming the first hypothesis. This is also to show that the population has almost the same needs in water consumption, but with more focus on cropping. The second hypothesis is confirmed and so there is no particular care given to the water sources since they commonly serve as dumping sites, are close to toilets and, in particular, enable pesticide mixing. The last hypothesis too is confirmed for typhoid, which was highly frequent among the studied population, along with diarrhoea and skin diseases, both of which can be attributed to pesticide misuse.

Conclusion

The quality of water found in the Santa agricultural area in Cameroon is hypothetically not safe for consumption when all the observations made in this study are considered. The poor knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) demonstrated by respondents towards water treatment and the care given to the water source promote numerous water-related diseases and pesticide related illness among the population. It is hugely important for water users to be educated on the risks linked with pesticide use, the importance of water source care, as well as the benefit the population will derive by protecting and maintaining the water sources to keep them sanitized and free of contamination.

Author contributions

The main investigator of the work, Jean Sonchieu coordinated the collection and analysis of data. Constant Tapaat collected data and participated on analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- AFD (African Development Fund)., 2000. Policy for integrated water resources management. Available from:https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/sectors/water-supply-sanitation. [Accessed May 2019].

- Albani, A. and Ibrahim, M.Z., 2019. Development of graphical interface simulator of advanced wastewater treatment design process for teaching, learning, and assessment. Designs, 3 (27), 1–11. doi:10.3390/designs3020027

- Albert, A., et al., 2018. Health risk assessment of dermal exposure to chlorpyrifos among applicators on rice farms in Ghana. Chemosphere, 203, 83–89. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.121

- AMCOW (African Ministers’ Council on Water), 2015. Water supply and sanitation in Cameroon: turning finance into services for 2015 and beyond. Available from: https://www.wsp.org/sites/wsp/files/publications/CSO-Cameroon.pdf. [Accessed 29 January 2020].

- Amrita, A. Michael, K. and Alix, P.Z., 2010. Providing safe water: evidence from randomized evaluations. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 2, 237–56. doi:10.1146/annurev.resource.012809.103919

- Andre, K., et al. 2013. Environmental impacts from overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides amongst market gardening in Bamenda, Cameroon. Revue Scientifique et Technique Forêt et Environnement du Bassin du Congo, 1, 6–19.

- Asian Water Development Outlook, 2007. Achieving water security for Asia. China: Asian Development Bank. ISBN 978-981-4136-06-8.

- Belhassan, K., 2011. Relationship between river flow, rainfall and groundwater pumpage in Mikkes Basin (Morocco). Iranian Journal of Earth Sciences, 3 (2011), 98–107.

- Burch, J.D. and Thomas, K.E., 1998. Water Disinfection in Developing Countries and the potential for solar thermal pasteurization. Solar Energy, 64 (1–3), 87–97. doi:10.1016/S0038-092X(98)00036-X

- CAWST (Canadian Affordable Water and Sanitation Technology), 2011. Introduction to household water treatment and safe storage 12, 2916 – 5th Avenue, Calgary, Alberta, T2A 6K4, Canada. [Accessed 6 May 2018].

- Dai, A. and Trenberth, K.E., 2002. Estimates of fresh water discharge from continents: latitudinal and seasonal variations. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 3, 660–687. doi:10.1175/1525-7541(2002)003<0660:EOFDFC>2.0.CO;2

- Damalas, C.A. and Koutroubas, S.D., 2016. Farmers’ exposure to pesticides: toxicity types and ways of prevention. Toxics, 4 (1), 1–10. doi:10.3390/toxics4010001

- Expósito, J.L., et al., 2010. Groundwater protection using vulnerability maps and Wellhead Protection Area (WHPA): a case study in Mexico. Water Resources Management, 24 (15), 4219–4236. doi:10.1007/s11269-010-9654-4

- Hladíková, Z., et al., 2015. Microbial contamination of paper-based food contact materials with different contents of recycled fiber food microbiology and safety. Czech. Journal of Food Sciences, 33 (4), 308–312. doi:10.17221/645/2014-CJFS

- Kometa, S.S., 2013. Wetlands exploitation along the bafoussam – bamenda road axis of the Western highlands of Cameroon. Journal of Human Ecology, 41 (1), 25–32. doi:10.1080/09709274.2013.11906550

- Lee, E.J. and Schwab, K.J., 2005. Deficiencies in drinking water distribution systems in developing countries. Journal of Water and Health, 3 (2), 109–127. doi:10.2166/wh.2005.0012

- Li, Z. and Jennings, A., 2017. Worldwide regulations of standard values of pesticides for human health risk control: a review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14 (826), 1–41. doi:10.3390/ijerph14010001

- Loeb, S., Hofmann, R., and Kim, J.-H., 2016. Beyond the pipeline: assessing the efficiency limits of advanced technologies for solar water disinfection. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 373–380. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00023

- Manu, I.N., et al., 2014. Effects of farmer-grazer conflicts on rural development: a socio-economic analysis. Scholarly Journal of Agricultural Science, 4 (3), 113–120.

- McGinnis, S.M., et al., 2017. A systematic review: costing and financing of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) in schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14 (4), 4–42. doi:10.3390/ijerph14040442

- Montgomery, M.A. and Elimalech, M., 2007. Water and sanitation in Developing Countries: including Health in the equation millions suffer from preventable illnesses and die every year. Environmental Science and Technology, 41 (1), 17–24. 10.1021/es072435t

- Nerkar, S.S., et al., 2015. Can integrated watershed management contribute to improvement of public health? A cross-sectional study from hilly tribal villages in India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12 (3), 2653–2669. doi:10.3390/ijerph120302653

- Nguyen-Viet, H., et al., 2009. Improving environmental sanitation, health, and well-being: a conceptual framework for integral interventions. Eco Health, 6 (2), 180–191. doi:10.1007/s10393-009-0249-6

- Ngwa, N.E., 2001. Elements of geographic space dynamics in Cameroon: some analyses. Yaounde, Cameroon: ME Printers.

- PNDP (Plan National de Développement et Planification), 2015. Santa council: council development plan-CDP. Yaoundé, Cameroon: MINPLADT.

- Pouokam, G.B., et al., 2017. A pilot study in Cameroon to understand safe uses of pesticides in agriculture, risk factors for farmers’ exposure and management of accidental cases. Toxics, 5 (30), 1–15. doi:10.3390/toxics5040030

- Soden, B.J., 2000. The sensitivity of the tropical hydrological cycle to ENSO. Journal of Climate, 13 (3), 538–549. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<0538:TSOTTH>2.0.CO;2

- Sonchieu, J., et al., 2017. Pesticides applications on some vegetables cultivated and health implications in Santa, North West-Cameroon. International Journal of Agriculture & Environmental Science (SSRG-IJAES), 4 (2), 39–46. doi:10.14445/23942568/IJAES-V4I2P108

- Sonchieu, J., et al., 2018. Heath risk amongst pesticides sellers in Bamenda (Cameroon) and peripheral areas. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25 (10), 9454–9460. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-1243-8

- Svendsen, M., Ewing, M., and Msangi, S., 2009. Measuring irrigation performance in Africa. International food policy research institute. Discussion paper, IFPRI, Washington, DC. [Accessed 28 March 2020]

- Tanga, M.G., 2014. Effects of pesticide use on hepatic and renal functions in gardeners in the Western highlands of Cameroon. Cameroon: Master of Science Thesis in Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang.

- UNESCO, 2016. Water and jobs: the United Nations world water development report 2016. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund)., 2014. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Annual Report 2013. Available fronm: https://www.unicef.org/wash/files/WASH_Annual_Report_Final_7_2_Low_Res.pdf. [Accessed June 2020].

- Velis, M., Conti, K.I., and Bierman, F., 2017. Groundwater and human development: synergies and trade-offs within the context of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability Science, 12 (6), 1007–1017. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0490-9

- Wang, H., et al., 2013. Water and wastewater treatment in Africa –current practices and challenges. Clean: Soil, Air, Water, 42 (8), 1029–1035. doi:10.1002/clen.201300208

- WHO (World Health Organization), 2013. Household water treatment and safe storage. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Available fronm: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/water-quality/household/en/ [Accessed 28 March 2020].

- Yates, T., et al., 2015. The impact of water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions on the health and well-being of people living with HIV: a systematic review. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68, S318–S330. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000487

- Zephania, N.F., 2014. Montane resources exploitation and the emergence of gender issues in Santa economy of the western Bamboutos highlands, Cameroon. International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research, 1 (1), 1–12.