ABSTRACT

This article identifies relationships that dominate small and medium businesses in Mongolia. Unlike other parts of Asia, these relationships are not necessarily hierarchical, nor are they purely market-driven. Rather, they are characterized by groups of people who sustain each other’s businesses and the social relations that hold them in place. In identifying such relations, we extend questions raised in the ‘economy of favours’ literature. If favours granted between known individuals are not simply about economic transactions, we ask, then what does this say about the kind of capitalist economy prevalent in Mongolia? Not simply an outcome of external forms of financialization, nor a remnant of the socialist planned economy, these relations open up the possibility for a range of ways of doing business in a climate that does not guarantee economic and social security in the sense that we may be familiar with. Attending to the way business deals and people are made and remade within networks and groups, capitalism is opened up to an economic diversity that shapes it from within.

Introduction

Different conditions enable the growth of small businesses. According to certain formulations, business growth is related to the ‘right’ or ‘correct’ government policies, the availability of formal financing, and tax breaks. Small businesses also rely on sources of growth that are not documented in the economic and business literature, including financing, networks and social capital, personal connections, and reputation. These sources are likely to vary in form depending on the country in which they are embedded. They often influence the kind of business environment and form of capitalism that take hold in a given place.

This article explores relationships and strategies that seem to dominate small and medium businesses (or small- and medium-sized enterprises, SMEs, Mng. jijig dund üildver) in Mongolia. We look at the formation of networks and ‘groups’ – associations of businesses with certain people – that help small businesses mitigate risk. Unlike other parts of Asia, these relationships are not necessarily hierarchical, nor are they purely market-driven. Rather, they are somewhere in between these types and are characterized by networks or groups of people who sustain each other’s businesses and the social relations that hold them in place.

In identifying such relations, we extend existing questions raised in the ‘economy of favours’ literature (Makovicky and Henig Citation2017). We ask, if favours are not simply about economic transactions, then what does this say about the kind of capitalist economy prevalent in Mongolia? We suggest that small-business ‘groups’ are not simply to be viewed as nascent forms of conglomerates with legal backing (as in other parts of North-East Asia). Instead they often take the form of extended networks with a ‘tolgoi’/‘ezen’ (head) company and ‘ohin’ (daughter) companies.Footnote1 They are not simply a remnant from socialist times. Their purpose is not necessarily to facilitate forms of corruption (see Shagdar and Bonilla, this volume), which often involves marshalling personal (or informal) connections to redistribute public resources, and they are similar to the networks and groups found in many post-Soviet countries during the central plan and early transition period.

Instead, we have found that these relations are very much an outcome of (or response to) forms of financialization imposed from outside, particularly the issuing of short-term business loans. They allow people to redistribute private resources in order to ride the fluctuating boom and bust associated with the mining economy of 2011–2016. In functional terms, being part of such networks allows small businesses to spread their risks, bid for government procurement tender, pool resources, source new suppliers, access markets and sources of funding, and resolve business disputes, while protecting the business from attack. Attending to these features, we comment on the form of capitalism that is being practised in Mongolia. More than simply a way to gain profit and hold it between friends (as argued in much of the literature on post-socialist economies), such networks are a way to survive the tempestuous turns of late liberal economic policy and navigate its dramatic stops and starts.

In this light, we argue that these arrangements are the outcome of very particular forms of financialization implemented in Mongolia in the past 10 years and a result of ineffective government policies (as shown in our survey results). Because the Mongolian economy is dominated by a few large companies, who contribute the bulk of total taxes, small businesses often resort to larger networks or groups of business in order to survive. Here, favours maintain networks of support in the face of new forms of financialization (not just the flow and exchange of goods and services) when state support is lacking. They allow people to expand their businesses and networks.

They also allow people to enact certain kinds of relations and forms of subjectivity. In this sense these arrangements are more than simply functional responses to external forms of financialization and lack of government support. In a less ‘transactional’ (Sneath Citation2006) sense they open up business relations to a wide array of affective registers, which advance individual ethical projects (Makovicky and Henig Citation2017). In this light we ask, what does it mean to be a business person in Mongolia? It appears that managing the needs and demands of different kinds of relations, trading inside knowledge and favours with some while concealing it from others, is a crucial way in which people enact this particular kind of work. Without doing so, one remains on the margins, unable to garner the support and attention needed to sustain one’s business. Attending to the way business deals and business people themselves are made and remade within networks and groups, we open up a window onto what small-scale business activities are like in Mongolia.

Our research shows that networks (or informal connections and groups) allow SMEs to (1) hold in place existing relations and expectations between known individuals, and (2) facilitate utilitarian forms of exchange that secure businesses in times of economic slowdown; and also that (3) these favours are often intensely non-functional and risky, and do not always guarantee a return, but allow people to enact particular forms of subjectivity crucial to business in Mongolia. Maintaining networks and trading favours are not simply a way of coping on the margins of capitalism. They are not simply a remnant of some post socialist phenomena. Rather, they emerge as strategic ways of organizing business in a boom/bust mineral economy that is flooded with economic incentives and forms of financialization.

The stops and starts of the Mongolian economy

As background to the economic landscape in which this research took place (2015–17), Mongolia is a former centrally planned economy richly endowed with natural resources. With the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1990, Mongolia faced harsh economic conditions. The country struggled with severe shortages and other macroeconomic imbalances in an attempt to adjust to the new market conditions. The economy experienced a few years of decline and hyperinflation, before slowly recovering in the mid-1990s. The government had to undertake policy measures such as food rationing, mass privatization, gradual price liberalization, massive retrenchment of the civil service, and drastic tax reforms. The abundance and resilience of the livestock sector has helped it overcome many economic hardships quicker than many other countries in the region. Although the number of livestock grew substantially, the role of agriculture has declined gradually since then, with the revival of manufacturing and large expansion of the service sector.

Mongolia has rich deposits of gold, copper and coal, the country’s principal minerals. As of 2016, the mining sector accounted for about 17% of GDP, 71% of industrial output and 87% of total exports. This natural resource endowment and the discovery of some world-class gold and coal deposits have defined the overall economic climate in recent years. Since the early 2000s, Mongolia has gone through a typical full cycle – and more – of natural resource boom and bust. In 2009, Mongolia had a negative growth rate, with a sharp decline compared to the 9.1% average growth in the five preceding years. However, the economy recovered quickly from this brief decline. Commodity price upturn and the steady economic performance of China – Mongolia’s main export destination – contributed to a quick recovery and subsequent rapid economic expansion. From 2010 onwards, Mongolia was identified as a frontier economy globally, attracting foreign investment to the exploitation of its large stock of resources. In 2011, Mongolia had a growth rate of 17.3% and attracted USD 4.7 billion in foreign direct investment, equivalent to 45.3% of GDP. Per capita income grew from USD 500 in the early 1990s to about USD 4000, upgrading Mongolia from a low-income to a middle-income country. In this climate, the Mongolian government was tempted by the promise of future economic growth to bet on the future economy and take out sovereign debt bonds. In addition to the USD 500 million loan taken from the European Union shortly before, the government issued the USD 1.5 billion ‘Chinggis Bond’ in 2012. It was the largest sovereign bond to be issued by the Mongolian government, and it sold quickly on the international market, indicating high investor confidence in the local economy.

In retrospect, we may now surmise that the government made rash decisions about how to spend its money. The funds raised were put into the newly established Development Bank of Mongolia and used for large public investment projects, creating a huge debt burden on the national budget. Some of the funds were allocated to private investment projects, without proper scrutiny, appraisal of their business plans, or implementation. Many of the bond projects financed through the Development Bank were shadowed by allegations of corruption and cronyism. Other forms of financialization were implemented, somewhat hastily, including low-interest mortgages and a proliferation of loans for businesses through banks and non-bank financial institutions, and most Mongolian people now find themselves, like their country, heavily in debt. By 2015 the economy slowed and is expected to continue to grow only modestly in the next few years amid low commodity prices, reduced foreign investment, and stalled mining projects. In 2017, the first interest repayments were due. Increasing amounts, including repayment of the loan principal, are expected to be paid in the coming years. The government has issued more bonds, part of which will be used to repay the existing debt. Many of the public business projects which were invested in through government loans have not materialized. Some of them are being scrutinized by the Anti-Corruption Agency. Corruption and bribery accusations are rife, and there is a general sense of wanting to blame individuals for mismanagement of these funds. In 2017 the government agreed to undertake an Extended Facility Fund programme with the International Monetary Fund and sought support of other donors to close the budget gap and overcome balance-of-payment issues. Despite this dire situation with the national budget, businesses and banks are largely being sustained, and salaries and social security payments are duly being made, while public investment projects are being slashed. Some taxes, including personal income tax and social security payments, will rise in 2018, as a result of policy re-orientation, which may hurt the middle class. Recent signs of economic recovery, coupled with tax reforms and debt restructuring measures undertaken by the government, have helped the parliament pass the budget for 2018, albeit with great difficulty.

Networks of relations: enactions, transactions and favours

In several East Asian countries, relations based on personal and family networks dominate business spheres. For example, in South Korea chaebol business conglomerates are often global multinationals with different international enterprises controlled by a single chairman (Daewoo, Hyundai and Samsung are examples). These groups are often family-controlled corporate groups that allow people to gain access to favourable loans and state licenses, and are very hierarchical (Beck Citation1998; Kim and Park Citation2011, 81). A similar format exists in Japan. Nakamura (Citation2002) explains that zaibatsu relations dominate Japanese business management structures as a kind of ‘enterprise group’ (236), or a diverse ‘corporate grouping’ brought together by multiple members of a family or by a clan (240).

The Mongolian business networks and groups that we identify differ considerably from Japanese and South Korean conglomerates, as well as larger business groups in Mongolia, such as Tavan Bogd, MCS. They are not as hierarchically structured as the Japanese and Korean conglomerates. While the mining and banking sector in Mongolia is characterized by hierarchical business relations, businesses such as retail, carpentry and restaurants are less so. Customers and buyers tend to be on the same level, giving rise to more horizontal relations. Unlike many businesses in East Asia, small establishments in Mongolia supply their goods and services largely to the domestic market. As the survey shows, only 5.3% of small businesses export their products. This means that economies of scale are low for these entities due to the small population of the country and moderate level of income. Becoming bigger does not necessarily bring you success. Rather, small businesses need to be agile, to swiftly respond to the changing trends of a small market. Agility is achieved through loose and changing relations with a larger ‘head’ (tolgoi/ezen) company, ‘informal networks’ (tanil tal), and bigger ‘groups’ (grupp), which may support loan or tender applications, grant cash up front, and provide workers or jobs for smaller businesses through mutually benefitting agreements.

A body of literature that touches on the kind of business relationships and ‘agility’ that we explore is that of the ‘economy of favours’ (sometimes referred to using the Russian term blat, or Mongolian terms ariin haalga, heel hahuul, or avilgal; Sneath Citation2002, Citation2006; Ledeneva Citation2008, Citation1998; Humphrey Citation2012). This work tends to explain the reliance on networks and friendships for business favours and politics in two ways. First, it argues that historical experiences in the region, particularly those of a socialist planned economy, when people had to build networks outside formal institutions, determine the form and practice of favours that we see today. As Sneath (Citation2002, 97) argues: ‘The standard treatment of corruption in “transitional” societies is to see it as a rent-seeking vestige of a bureaucratic state, an example of a predatory, parasitic feeding off market.’ The second strand argues that instead of some remnant from the past, people are forced to engage in the granting and receiving of favours because they are the hapless victims of neoliberal state policy that marginalizes the masses, creating ‘suffering subjects’ (Robbins Citation2013). In these two approaches, the exchange of ‘favours’ is understood as an outcome of the socialist planned economy, or as a survival mechanism due to economic scarcity in the neoliberal post-socialist period. A third strand, put forward more recently in the edited volume by Makovicky and Henig (Citation2017), de-centres the utilitarian function of favours and argues that in attending to the intricacies of cultural difference, most notably perhaps how favours are enacted not as ‘informal practices’ against the ‘formal economy’ but as vernacular idioms and actions, we see that favours are always open to multiple interpretations on different scales, pointing to individual acts of ‘world-building’, as Zigon (Citation2017) has put it elsewhere.

Unlike contractual transactions based on individual self-interest, Sneath (Citation2006) has argued for Mongolia that the provisioning and reciprocity of favours among relatives and friends (including extended networks of friends) should be seen as the material flows of obligation. These are the expected materializations of already established relations and cannot be regarded as transactions of exchange (96). Upholding such obligations is more akin to what he terms ‘enactions’, for which the language of obligation and expectation are more suitable (Sneath Citation2012). More recently, Humphrey (Citation2017) has differentiated ‘favours’ from the enactions and transactions described by Sneath (Citation2006, Citation2012). Favours, she argues, ‘are exactly not the manifestation of obligation and do not consist of the enactment of previously established relationships. Indeed, an unexpected boon can initiate a new relation’ (57). Unlike enactions, Humphrey argues, favours may or may not be repaid, cannot be counted on to produce a return, and are not always enacted within pre-given relationships. This is to emphasize the ambivalence of favours ‘that can be considered as free from exchange in every particular instance, but also carries a potential of mutuality: as a transfer but also a transaction’ (Ledeneva Citation2017, 30). It is also to avoid the functionalist explanation that infers the intentions of actions based purely on their outcomes (Makovicky Citation2017, 220).

Through this kind of analysis we learn that ‘favours’ may be a type of action or practice that extends beyond a merely utilitarian/transactional function. Such actions include a wide range of affective meanings, which advance individual ethical projects and relationships, as well as economic outcomes. Here, granting and exchanging favours within networks and groups are not ‘ill-disguised transactions’ (Makovicky and Henig Citation2017, 7). Instead, granting (and receiving) favours may endow actors with social standing and a sense of self-worth. It reflects the human pursuit of dignity and should be seen as ‘a mode of expression’ (although it does expect some kind of reciprocity, even though that may not be in a transactional sense) that is often risky and sometimes not reciprocated. In the following, we see how the granting of favours within networks and groups allows SMEs to (1) hold in place existing relations and expectations between known individuals, while also (2) facilitating utilitarian forms of exchange that secure businesses in times of economic slowdown. We also see (3) the precarious and ambivalent nature of granting favours among businesses. This is to point out the intensely non-functional and risky nature of favours, which do not always guarantee a return, but may inadvertently grant a range of affective meanings for groups or individuals. In this sense we may say that brokering favours between known individuals is a way of enacting a certain kind of subjectivity that makes and remakes business people in exchanges that do not themselves always amount to material manifestations.

We observe strong elements of loyalty among the SMEs analysed in our study. SMEs tend to purchase from the same suppliers, and sell to the same consumers, and they consider their reputation important in the success of their business. Moreover, in the absence of effective government structures, small businesses rely on their personal and professional connections to obtain information, find new markets, develop new products, and raise finances. This is especially true in a hostile economic environment of economic downturn, where general trust is lower. As research on emerging markets has shown (e.g., during the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and the more recent global economic shock), small businesses often opt to utilize networks and rely on cooperative strategies to cope with economic hardship. In these instances, networks become a way of sustaining business and lowering transaction costs. But more than this, they also come to shape the very form that business relationships take in Mongolia, turning individual traders into linked and connected men and women reliant on each other for actual business and social standing. This is to highlight how participating in these relationships is crucial for the enacting of forms of subjectivity. Being the kind of person who juggles different networks and obligations is a way of being a modern business person, reaping the rewards of such relationships and forms of business in terms of both social and economic capital.

Research methodology

This article is the result of collaborative research, bringing together quantitative and qualitative analysis of SMEs in Mongolia in 2015–16. Narantuya has been working on a large, nationally representative sample of over 1500 SMEs. The purpose of the survey was to measure the transaction costs (or the compliance costs) that small businesses are facing. The survey was carried out by her research team in 2015–16. They wanted to know specifically whether government policy was prohibitive (i.e., whether the system of paying taxes was prohibitive, not the paying of taxes in themselves) to SMEs flourishing (some of whom in the survey the government had lent money to). In this vein, they wanted to know whether they should ‘liberalize the economy’ to help SMEs flourish, to reduce costs related to red tape. Second, they wanted to know whether the transaction costs of dealing with other business partners were prohibitive. This line of inquiry looked at whether establishing secure business relationships was prohibitive to establishing the growth of businesses themselves and was related to risk-taking.

Rebecca came to this research with an interest in the way business entrepreneurs were accessing and using loans (through pawn shops, non-bank financial institutions, banks and friends). She had done preliminary research on businesses in the countryside and the way people accessed cash in pawnshops and nonbanking financial institutions in Ulaanbaatar. Rebecca followed up with several of the businesses included in Narantuya’s survey in May 2016 and again in September 2016, focusing on how these businesses were weathering the dramatic changes in the economic and political climate. This period coincided with the National Elections of 2016, when the Mongolian People’s Party was elected over the Democratic Party and Mongolia experienced a massive drop in GDP and a general sense of ‘economic crisis’ (hyamral).

Rebecca’s research showed that in a small business group or network people do not need money or contracts (or even hiring a bully or going to court) to secure transactions and resolve disputes. The reliance on networks of trust actually helps secure the businesses in the long term, even if many were ‘lying dormant’ and inactive (i.e., many declared bankruptcy), only to start up again when the economic climate allowed. Networks such as these helped sustain businesses in the short and medium term. Indeed, while foreign investors may berate the reliance on networks in business communities in Mongolia, what they fail to notice is that such networks provide a way of avoiding different kinds of transaction costs in a volatile market, allowing small businesses to float through economic storms in the longer term. The combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches to this topic has enable both great breadth and depth of analysis. Theoretically, we aim to straddle both a functional analysis (based on market principles in the survey) and a more anthropological analysis. This combination does not foreclose one type of conclusion over another, but reveals the complex organizational structures and strategies of many small businesses in Mongolia. We turn now to the survey’s quantitative findings, which lay the ground for our qualitative inquiry.

Doing small business in Mongolia – importance of informal relations (networks)

Much of Mongolia’s economy is dominated by larger companies or conglomerate groups. Small businesses account for about a quarter of total output, a relatively small proportion compared to the global average of 40–50%. However, these businesses employ about half of the total workforce (World Bank Citation2012). With the recent surge in the mining sector and its associated boom and bust experiences, the government recognizes the importance of small businesses in diversifying the economy and increasing employment. Since the passage of the Law on Small and Medium Enterprises in 2007, the government is responsible for targeted intervention in the SME sector to improve the outreach and effectiveness of the government support programmes. The major intervention measures include establishing a special SME Development Fund and Loan Guarantee Fund and using movable and intangible property as collateral. In addition, numerous other activities such as training, fairs, and business incubators were carried out in the past decade. However, the actual effectiveness of these government efforts seems to be low.

Lending to SMEs is perceived as risky by commercial banks – the main formal source of funding – largely due to the lack of collateral. Loans are usually offered to small businesses at higher interest rates and for shorter period of time. The government and international aid agencies provide some low-interest funds to support small businesses, which are managed through commercial banks. However, these constitute only a small portion of the total loans (Bank of Mongolia, Citation2017). Lending agencies have differing policies and occasionally target specific businesses or sectors. Some of the funds are devoted to capacity-building and training programmes for small businesses (International Finance Corporation Citation2014). Small businesses see taxation policies and government red tape as important obstacles in advancing their business. For instance, our survey found that the burden of transaction costs associated with complying with government regulations related to business registration, taxation, customs, government standards, state inspection, infrastructure and the like, is quite high.

Overall, the business environment seems to be largely hostile, and to have worsened for most SMEs in recent years. The available resources are few and usually come at a high cost, making them unaffordable for smaller businesses. The government has launched some support policies. However, some of these are relatively new, and most of them remain ineffectual. Most SMEs have limited information and understanding of government policies towards small businesses. Only 18.1% of respondents admitted that they have sufficient information on government policies, while 43.7% answered that they have very limited or no information. At the same time, about 40% believe that the policies are poor in terms of content/design, and 51.2% believe that the implementation is poor at all levels (both national and local). There seems to be low confidence in and acceptance of formal government policies.

As may be expected, small businesses approach local governments and agencies more frequently than lawmakers or central government agencies. A quarter of all respondents had attended some event (fairs, exhibitions, training, etc.) organized by a local SME-supporting agency. The overwhelming majority (about 85%) find these events reasonably successful. Overall, small businesses in Mongolia are dissatisfied with the government policies and find them largely ineffective in supporting small entrepreneurs. Other sources of support play a similarly modest role. Of the NGOs, the most effective seems to be the Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MCCI), closely followed by the professional associations. These organizations create a formal source of networking for businesses, but cater more to large businesses. For instance, membership in the MCCI is expensive and often out of reach of small players. The question then arises: Where do small businesses find support, especially in times of economic hardship, and what is the role of informal relations, given the low level of support provided by formal policies and institutions?

Our study revealed that most SMEs get useful information and support for their businesses from other, largely informal sources. For instance, SMEs assert that information on potential suppliers and potential buyers is not readily available. Well over half of our respondents struggle to find reliable information on potential buyers. It is particularly difficult for rural and smaller enterprises (with less than 20 employees). The same is especially true for micro businesses ().

Table 1. How available is information on potential buyers? (%)

Most SMEs obtain information about potential suppliers and potential buyers through networks and informal channels, such as professional circles and friends. Official sources of information play a significantly smaller role, which is not surprising given the modest role played by formal institutions. Well over half of our respondents receive information from personal networks. Connections with friends play the most important role in finding new markets for their products ().

Table 2. Sources of finding information (%).

It is interesting to observe that the SMEs develop high level of loyalty with their suppliers. But they admit that their clients are not that constant and therefore they need to keep searching for new buyers ().

Table 3. Loyalty to suppliers and of buyers (%).

SMEs value their reputation as an important source of their business success ().

Table 4. Importance of business reputation in successfully running business (%).

SMEs develop a high level of trust with their business partners. About three-quarters of all respondents say that all or most of their business partners are trustworthy ().

Table 5. Do you think your business partners are trustworthy? (%)

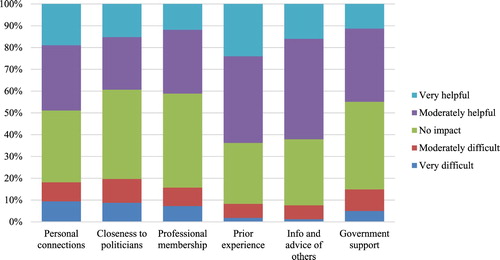

Through these findings, we see that personal connections, professional membership, prior experience of doing business, and information and advice obtained from friends and family seem to be of great importance for dealing with the government in order to successfully run a small business. Informal relations and connection seem to be important in dealing with not only business partners but also government agencies ().

Ethnographic research among SMEs

Assisted in her research by Ms. Batbayaryn Erdenezaya, Rebecca met with businesses from Narantuya’s survey in May 2016 and then again in September 2016 to discuss how they were coping with the economic downturn (ediin zasgiin hyamral, ediin zasgiin höösrölt, lit. economic ‘crisis’, or the ‘bubbling’ economy), what challenges they faced, and how they anticipated their businesses would do in the future. The businesses included, among others, a mining consultancy, a catering company, a restaurant, and a carpentry business. The businesses were chosen for the range of sectors they represented. At first, many reported that they were doing well financially (a concern, perhaps, with wanting to present things to a foreigner in a particular way, or a deeply held concern with outward appearances, despite many holding ‘empty jobs’ – see below), but in talking with them it became obvious that this was not the case. In this very short period from May 2016 to September 2016, two of the businesses had become bankrupt (the restaurant and the mining consultancy),Footnote2 one had to substantially reduce the number of people it employed, and one was recasting itself in another sector entirely. Most had experienced difficulty since the ‘boom time’ (büümiin üe) began to ‘bubble’ (höösrölt) and finally was experienced as a ‘crisis’ (hyamral). Two of the businesses – the catering company and the carpentry company – spoke of benefiting from being part of informal networks (tanil tal) or wider business ‘groups’ (grupp). It should be noted from the outset, however, that these are not conglomerates, nor are they legal entities, but informal groups, based on personal networks, where profits and collateral as well as social connections are shared and distributed between the director (ezen, ‘master’) or head (tolgoi) and the smaller, daughter (ohin) SMEs.

Cuts and the distribution of costs

The catering company, which, although part of a larger group, had to cut their full-time staff from 30 to 14, and then only 7, in the period from May to September 2016, and in a climate where most new tender announcements have been frozen, were about to recast their business entirely to focus on private loans. When we visited their lavish premises in May 2016, there were no workers to be seen on the vast company floor. The working day had been shortened, we were told, allowing the 14 staff (at that time) to straddle two jobs and find additional incomes. At this time the company was waiting for the national elections to be over to apply for a large tender to cater for Mongolia’s biggest copper and gold mine (this had not transpired when we met again in September, and by this time their ‘expenses were greater than their income’). They had all but ceased their usual business, with the rising cost of imported goods and inflation of foreign currency. They were able to keep their premises and hold onto some of their workers because they were part of a larger business grupp that includes five other companies, including a construction company, that pool resources and contacts (for more on this, see below). By September, when the results of the national election had been confirmed and all tenders had ceased, the catering company was considering restyling itself entirely as a money-lending institution.

In contrast, the carpentry and repair company used to employ 18 people full-time. They now employed only 8 people and took on more at an hourly rate when needed. These people were sought, the company director explained, ‘through my network or people I know’ (holboo sülbee / tanil talaaraa). The head of this company benefits from relations with the director of a larger grupp,Footnote3 which includes a mining company and a construction company. ‘As a group,’ he says, ‘we apply for tenders and get loans from each other.’ Furthermore, members of the group are always in debt to each other (dandaa örtei). For example, he has a 10% loan from a personal friend in the group. To pay this off he has agreed to sell a plot of land for another member of the group who bought it three years ago. To pay his loan and his staff he needs to sell this land for his friend, who will, give him part of the profit.Footnote4 All the work he gets is through his network, or people he knows. ‘If you have a network and people you know in the tender commission, or with the people who are doing the selection, you will get a job’, he explained.Footnote5

When we met with small businesses they were initially reluctant to reveal any difficulty they were facing. Was this because of not wanting to draw attention to something negative about their work in case it escalated into something bigger? Or perhaps they hoped that Rebecca, as a foreigner, might bring in future foreign business connections. As we spoke in more detail and visited again in September, however, it appeared that everything was not as it had seemed. Many businesses that had started during the ‘boom period’ were emboldened to take risks, buttressed by forms of financializaton that suddenly became available on the market, such as low-interest loans, coupled with the promise of future national economic growth. By 2016 they were almost all struggling or unable to pay off these loans through their business. However, rather than claiming bankruptcy, while one company could be doing badly, it could often withstand this for some time as it lived off the wealth of other companies in the group.

Such interdependence is not just the result of economic hardship. In the restaurant business that we studied, for example, they run a small hotel, have bought some land in the countryside to grow wheat and vegetables, and are thinking of establishing a flour mill. When asked if the accountant who worked there would classify these as part of a larger group, she replied that having a ‘head company’ (tolgoi kompani) is important to help you source things, such as labour, and also for getting loans in the first place, but it was not as big or formal as a group. Rather, these different businesses could be seen as subsidiaries of a head company. Interestingly, she explained that this organization had first been established as a ‘cooperative’ (horshoo) in the 1990s, and then changed its name to a ‘company’ as its operations extended (and shares were bought up from other previously state-owned companies in different sectors), and now exists as a head (ezen) company, with various subsidiaries (ohin kompani), which contain different branches (salbar). Here we can see that post-socialist forms of privatization have structured the networks, something confirmed by much of the literature on the ‘economy of favours’ in post-socialist countries. However, while their origin may lie in past economic conditions, they were being utilized to cope with current and new economic forms of financialization and incentives.

This kind of dependence on different companies, branches and networks is of course not just a feature of businesses in Mongolia. It is also a feature of families who lend to and support each other in times of need (see e.g. Fox Citation2016), and of individuals who might appear to be doing one thing, but are always also doing multiple other jobs and projects (Waters Citation2016). It was also clear that these networks and groups required a lot of work to uphold them – debts needed to be repaid, honour upheld, and so on – and sometimes a tipping point was reached at which the work involved in maintaining a network came to supersede the work that those very networks were meant to facilitate. This was compounded by the added tension that many jobs were practically ‘empty jobs’: placeholders for labour, without any financial payment (Rajkovic Citation2018). This included the many people who went for months without a salary and were caught in that tricky bind of (a) continuing to work for a company just to get a stamp in their social security books each month, with the hope that they might be paid sometime in the future for the work they had already done, or (b) jumping ship and trying their luck at another job which might just pay them after they completed the work. Networks, groups and the favours that flow between them are more than simply about economic transactions. Working without a salary could be a way to return a favour, or a way to create a future favour. In the following we focus on the strategies employed by the carpentry company. It illuminates some of the business possibilities facilitated through business networks. It also highlights the precarious nature of businesses in today’s economic climate and how this uncertainty quickly affects people at all levels.

A case study of a small carpentry and repair company

When we first met Bataa (9 May 2016), at a bar in the centre of Ulaanbaatar, he explained that he had run his own business for four years, which installs kitchens, and makes furniture and assembles it, for private people and for schools. His company used to employ 18 people, but now employs only 8. One of the reasons for this cut is that he is waiting to be paid for a project he has already completed. Through some people he knows, he got in touch with people in a business group. ‘I do not know their work very well. … We had a negotiation and did our work for them, but now I am waiting to be paid.’ This was ‘not a loan’, he explained, but rather ‘how can I say this … we had our own negotiation and did the work.’ He went on to clarify:

In general, you could say that there is almost nothing that supports us. However, if you have a good contact and it is profitable to that group, they will have us do their work. Most of the time, there is a principle that we will get our money later, after the work.

Imagine a tender worth one billion togrog. First I would give you 50 million, and then once we got the tender I would give you another 50 million. [In fact,] to get any kind of big job you definitely have to pay a certain percentage. … If you cannot pay in cash you can do it through barter.

On top of this principle, small businesses need to be included in a network of potential businesses they do work with. ‘If there is no network’, Bataa explained, ‘it is generally difficult to get a job done.’ Making a deal with a group means paying them a portion to be secured as a subcontractor and then doing the job, and lastly getting paid for the work. What becomes apparent in this kind of arrangement is that to secure new jobs small businesses either have to have a large amount of excess capital, or they have to work back-to-back in jobs whose payment supplies the capital needed to secure new work, something highly stressful to rely on in today’s fluctuating market. In spite of this, Bataa explained, ‘Because we do not always get the money in advance through the jobs we take on, we often have to take out loans. These are then paid off with the money paid to us once the job has been done.’

This kind of system has its drawbacks, but also its advantages. For a start, it means that although many companies are not able to pay their workers for several months as they wait for funds to come through, they can get their social insurance books (niigmiin daatgal) stamped to show that they are in full-time employment. This is necessary because you need uninterrupted stamps in your social insurance book (for up to two years sometimes) to apply for certain loans. Here we can see that it is often more important that people remain in ‘employment’ than that they receive their full salary. To illustrate how, in some instances, work is better than money, Bataa offered an example of his own involvement in selling land for someone else to raise cash. Over another drink, he explained:

I have known the director of this group for some time. When he didn’t pay me for the work I had done, he told me about a piece of land in Sansar. About three years ago, the group director had acquired a plot, roughly 6000 square metres, for three million dollars (USD 1 USD was almost at MNT 1300). Now they are trying to sell it for one million dollars, but without any success.

Companies or subsidiaries within networks often try to support each other through complex loan agreements, applying for larger work, and merging account books. For example, ‘within this group’, he explained, ‘there are 16 companies. In the current economic crisis, 8 of those 16 companies are working without any profit. By this principle, the ones making a profit fund the salaries, utility bills and so on of the other businesses. However, after three to four months, the companies who are making profits and transferring these to sustain the non-profit-making companies will often have to start making cuts, such as staff. These kinds of unpredictable lay-offs’, he lamented, ‘make it hard for individual families to pay off their loans’. From these examples we can see that networks may help in times of economic hardship and facilitate work in times of prosperity. They entangle people in relations of debt which may ‘squeeze’ (shahaa) them into having to take on near-impossible jobs, such as the selling of land in a climate when no land is being sold or bought. ‘If things continue like this for another two to three years’, Bataa explained, ‘then at least 30–40% of businesses will be forced to close down. Cash has become rare (homsdchihson). There are no sales, and because many raw materials are bought from China in US dollars, inflation is very prohibitive to Mongolians, as are the tax and transportation costs, which are all in dollars [büh yum ni dollaraar].’

Through these and Narantuya’s examples we see how business terms such as ‘faction’ (frakts), ‘tender’ and ‘group’ are frequently used by Mongolian business people to refer to more than their English equivalent. Such informal groups and networks are essential for the survival of SMEs, allowing them to access cash, apply for tender to larger operations when they pool their assets in applications, and provide jobs for smaller companies in their group or network. Furthermore, they often allow each other to access resources through ‘barter’, pooling collateral, and shoring up account books when going for audits. The pooling of resources and the circulation of cash within such networks is extremely prevalent, creating factions, holding certain networks of people in power and excluding others. To join these groups, one man explained who works for a large auditing company, one either has to know people already, or give a bribe (heel hahuuli, hahuuli ögöh-avah), commonly referred to as ‘buying a share in the company’. The larger, ‘head’ or company director then distributes funds to the smaller SMEs.

This kind of activity, rather than being viewed as corruption, may anthropologically speaking be understood as indicative of ‘culturally distinct’ forms of sociality, such as enacting the long-standing relationship between a master and a custodian/patron. Like the ezen (master) of a small group of households (hot ail), the head of the company shares resources among the group and distributes funds to those in need, so that business groups hold certain networks of power in place and exclude others, omitting certain activities from account books to avoid taxes while benefiting the group. Factions across groups ensure that economic difficulties can be overcome, and time limits for repayments stretched. Bumaa, an accountant who had worked for 18 years at a restaurant (which is also part of a wider group of businesses, including a flour mill) in the centre of Ulaanbaatar, had received her job from ‘people from her homeland’. Now there were many ‘subsidiary companies’ (ohin kompani) attached to the ‘head company’ (ezen kompani). They could provide support and apply for loans for the smaller companies. However, ‘during socialism there were no such businesses. As soon as the market [economy] started, there were no companies. Instead, cooperatives (horshoo) were established, and then those cooperatives changed their name to companies when their operations were extended. And then the companies grew into subsidiary companies, where there could be other branches from one company. But things were not going smoothly’, she lamented. ‘There is a terrible crisis, and the expenses are getting larger and we cannot buy new things and this has been very difficult.’ Loan repayments, taxes and electricity bills were mounting, and different projects were under pressure. ‘Since we don’t have any sales’, she explained, ‘we don’t have money, and so we can’t pay these outstanding debts.’ As debts were mounting, so too were people trying to find ways to repay them through different kinds of connections. On the phone, Bumaa lamented to a colleague that she had been following up on a loan but it had not been successful. She recommended that they follow two other leads, people who might owe them money. In attending to the flow of favours and resources that are exchanged between people, such as in this brief telephone conversation, we see that the network of people embroiled in one project alone is complex and opaque. People appear to be juggling multiple favours and transactions, passing on ‘insider’ knowledge and tips, while confiding in others. Indeed, people often brokered inside information over the phone. Sharing tips and suggestions, offering support and insight are ways of forming alliances and trust between people. They are also ways of showing to others that you are connected, have insight and know things others might not. In short, they are a way of establishing insiders and outsiders and enacting a crucial kind of subjectivity which defines what business is.

The complex array of activities facilitated by ‘favours’ between groups and networks go beyond mere economic function. They speak to ways of organizing social life in an environment shaped by neoliberal financial incentives as well as by older ways of doing business that echo socialist policies. Furthermore, because of their often non-transactional motivation, they also open up the possibility for a range of ways of enacting forms of subjectivity that determine factions and alliances.

Concluding remarks

The data from Narantuya’s survey show that most of the SMEs in Mongolia have limited information on government policies. They find these policies largely ineffective, at both the policy formulation and the implementation level. The local government’s activities towards SMEs, especially fairs, training programmes, etc., seem to be a little more beneficial than those of the central government. In short, the formal government policies largely do not work.

Second, and perhaps as an outcome of this lack of government intervention, our research highlights that networks play significant and important roles in addressing issues faced by the SMEs. In relation to this, concepts such as loyalty, business reputation, and trust are extremely important for small businesses. Most SMEs develop a high level of loyalty to business partners and find most of their business partners trustworthy. They consider reputation an important source of business success. Something is gained through the brokering of favours, both material and immaterial, such as knowledge, tips and insider information. More than half of the SMEs we have focused on never change suppliers. They stick to the same suppliers and have a loyal customer base. It is buying from and selling to the same people that leads to some stability, not competing with market prices and taking risks.

Third, these SMEs have emerged during a period of intense implantation of external forms of financialization, such as the availability of small-scale loans, sovereign debt bonds, structural re-adjustments and geopolitical wranglings, which were implemented in Mongolia during the years of the mining boom and before. Instead of seeing these practices as simply a form of ‘economic imperialism’ leading to today’s suffering, it is important to highlight how Mongolian business practices have made certain features out of these wider global forms. In the past 10–15 years Mongolians have been exposed to the mass availability of credit due to expansionary monetary policies and money raised through sovereign debt. This has led to more SMEs, many of which have tried to survive in an environment that is often not economically viable enough for them to pay off their debt in time.

We now know, from our survey as well as from examples all around the world, that the model of micro-financing SMEs as sustainable entities through short-term loans does not work. For a start, the loans are often only available on a very short-term basis (some for only six months). People cannot repay them in the time allocated, and make sure their businesses work. The tax system is fragile and does not always reward those who pay. There is not enough of an established market for businesses to succeed. Given this rather volatile climate, it is not surprising to find that Mongolian businesses are often not single entities but part of larger networks, allowing them to spread their risks and support each other at moments when repayments become difficult, or cash is needed to tie over lulls in the market. But more than simple survival strategy, such relations determine suppliers and buyers as well as business partners and friends. Perhaps this is a business model that is more sustainable in today's volatile market, having emerged out of it, but also one that appears to work in Mongolia.

Is the granting of favours simply a way of making sure that small businesses survive the ups and downs of the economy? As we see in some of the ethnographic findings, the paradox of relying on favours, and on support granted within networks or groups, is that it involves an element of risk-taking (recall the man who hadn’t been paid yet for his work and was forced to try to sell another man’s plot of land to raise the funds). Favours may or may not be granted or accepted, adding a degree of ambiguity or paradox (Holbraad Citation2017). It is this paradox (the non-functional / non-utilitarian nature of such relations) that allows us to think, perhaps, more broadly about the form of capitalism that is emerging here.

Reviewing our findings, we discern that personal connections, professional membership, experience in business, and information and advice obtained from friends and family seem to be of great importance in order to successfully run a small business. But favours are often intensely non-functional and risky, and do not always guarantee a return. For example, people work on jobs without being paid at the start, or wait several months for payments which may never transpire. They turn to others for a favour which may never materialize, but do so in the hope that it will. Following Jacobs and Mazzucato (Citation2016), it is clear that to understand these features we need a richer characterization of what markets are. Simple understandings of the market as a place for transactions do not do such features justice. Markets are better understood as the outcome of interactions between economic actors and institutions, both private and public (Jacobs and Mazzucato Citation2016, 18). Neither the outcome of externally imposed forms of financialization, nor explainable as a kind of ‘culturally distinct’ form of sociality, such as enacting the long-standing relationship between a master and a custodian/patron, or even as a remnant of doing business during the planned economy of the socialist period, we argue that such relations are at the necessary heart of many different kinds of economic activity in Mongolia precisely because of their non-transactional motivation. They open up the possibility for a range of ways of doing business in a climate that does not guarantee economic and social security in the sense that we may be familiar with but that can hold in place various networks of favours.

Finally, if favours are not simply about transactions, then what does this say about the kind of capitalist economy prevalent in Mongolia? Asking this kind of question allows us to situate our discussion in relation to recent debates, mostly notably spearheaded by Gibson-Graham (Citation2006), and later taken up by people like Laura Bear (Citation2015) and Anna Tsing (Citation2015), which look at how capitalism always contains diverse kinds of practices, which are not always about exchange, in a formal neoclassical sense of a maximizing individual. As people in this region are increasingly being entangled in different forms of financialization, from complicated life insurance policies to different forms of credit and debt, we hope that this article has shown, at least to some degree, how the reliance on networks and groups works around and inside known economic forms, which are often introduced from elsewhere. Indeed, it seems that the reliance on networks, groups, and the exchange of favours within businesses is precisely not a remnant of socialist or post-socialist life, something that is sometimes highlighted in the literature on the economy of favours. By contrast, such relations drive current forms of capitalism, determining how the economy is formed and the kinds of subjects who form it. If we attend to the way business people and their businesses are made and remade through networks and groups, capitalism appears in a way we may not always be familiar with, holding and reproducing a diversity which comes to shape it from within.

Acknowledgments

We thank Batbayaryn Erdenezayaa for help with this research and for following up with many of the SMEs. We also thank the Emerging Subjects Advisory Board for input, and all the people at the Making Mongolian-Capitalism conference for their comments. I (Rebecca) also thank Nicolette Makovicky and David Henig for inviting me to comment on their book Economies of Favour after Socialism (Citation2017), which gave us the chance to rethink our material in light of their Introduction. Finally, we thank Bumochir Dulam and Rebekah Plueckhahn for their work in putting the conference together and for their editorship of this volume.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The terms ‘head company’ and ‘daughter company’ are used in large business groups. However, we also found these terms used to describe business arrangements among small interconnected businesses.

2 This term was used to refer to a range of practices which involved permanently closing a business to temporarily re-allocating the business funds into something else during the economic downturn.

3 Although we use the English term ‘group’ to refer to these relations, it is important to highlight that the meaning of grupp does not necessarily match that of its English equivalent.

4 He has another loan for six million togrog from a non-bank financial institution.

5 He speculates that an average of 5–10% of tenders go to people in the komiss (the public committee or commission that reviews the tender materials and selects the winner among the bidders). ‘This became an unofficial rate to win any tender’, he explained. ‘People say that is why many want to become a civil servant and run in the election by wasting millions of togrog. If he wins, then he makes more money than he spent in the election.’

References

- Bank of Mongolia. 2017. Development and Financing of Small and Medium Businesses: Survey 2017” (Jijig Dund Üildveriin Högjil, Sanhüüjiltiin Baidal: Tüüver Sudalgaa). Ulaanbaatar: Bank of Mongolia.

- Bear, L. 2015. Navigating Austerity: Currents of Debt Along a South Asian River. Stanford University Press.

- Beck, P. M. 1998. “Revitalizing Korea's Chaebol.” Asian Survey 38 (11): 1018–1035. doi: 10.2307/2645683

- Fox, L. 2016. “The Road to Power.” https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/mongolian-economy/2016/08/24/the-road-to-power/, Emerging Subjects Blog

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Henig, D. and N. Makovicky. 2017. Economies of Favour after Socialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holbraad, M. 2017. “Afterword: The Social Warmth of Paradox.” In Economies of Favour After Socialism, edited by D. Henig, and N. Makovicky, 225–234. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Humphrey, C. 2012. “Favours and “Normal Heroes”: The Case of Postsocialist Higher Education.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (2): 22–41. doi: 10.14318/hau2.2.003

- Humphrey, C. 2017. “A New Look at Favours: The Case of Post-socialist Higher Education.” In Economies of Favour after Socialism, edited by D. Henig and N. Makovicky. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- International Finance Corporation. 2014. “SMEs and Women-owned SMEs in Mongolia: Market Research Study.” http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/d85f65804697b853a598bd9916182e35/Women+SME-Mongolia-Final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- Jacobs, M., and M. Mazzucato. 2016. “Rethinking Capitalism: An Introduction.” In Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, edited by M. Jacobs, and M. Mazzucato, 1–28. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kim, Eun Mee, and Gil-Sung Park. 2011. “The Chaebol.” In The Park Chung Hee Era, edited by Byung-Kok Kim and E. F. Vogel. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Ledeneva, A. 1998. Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ledeneva, A. 2008. “‘Blat’ and ‘Guanxi’: Informal Practices in Russia and China.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 50 (1): 118–144. doi: 10.1017/S0010417508000078

- Ledeneva, A. 2017. The Ambivalence of Favours: Paradoxes of Russia’s Economy of Favours. In Economies of Favour after Socialism, edited by D. Henig and N. Makovicky. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Makovicky, N. 2017. “The ‘Shadows’ of Informality in Rural Poland.” In Economies of Favour After Socialism, edited by D. Henig, and N. Makovicky, 203–224. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Makovicky, N., and D. Henig. 2017. “Introduction – Re-Imagining Economies (After Socialism).” In Economies of Favour after Socialism edited by D. Henig and N. Makovicky, 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nakamura, N. 2002. “The Present State of Research on “Zaibatsu’: The Case of Mitsubishi.” Social Science Japan Journal 5 (2): 233–242. doi: 10.1093/ssjj/05.2.233

- Rajkovic, I. 2018. “For an Anthropology of the Demoralized: State pay, Mock-Labour, and Unfreedom in a Serbian Firm.” Journal of the Roayal Anthropological Institute N.S. 24: 47–70. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.12751

- Robbins, J. 2013. “Beyond the Suffering Subject: Toward an Anthropology of the Good.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (3): 447–462. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.12044

- Sneath, D. 2002. “Reciprocity and Notions of Corruption in Contemporary Mongolia.” Mongolian Studies 25: 85–99.

- Sneath, D. 2006. “Transacting and Enacting: Corruption, Obligation and the use of Monies in Mongolia.” Ethnos 71 (1): 89–112. doi: 10.1080/00141840600603228

- Sneath, D. 2012. “The “Age of the Market” and the Regime of Debt: The Role of Credit in the Transformation of Pastoral Mongolia.” Social Anthropology 20 (2): 458–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2012.00223.x

- Tsing, A. L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Waters, H. 2016. “ Living on Loans, Emerging Subjects.” Blog post, 22nd January. www.blogs.ucl.ac.uk/mongolian-economy/2016/01/22/living-on-loans/.

- World Bank. 2012. Mongolia - Financial Sector Assessment (English). Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP). Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530751468323337238/Mongolia-Financial-sector-assessment

- Zigon, J. 2017. “A Politics of Worldbuilding.” In Dispatches, Cultural Anthropology website, December 5, 2017. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1249-a-politics-of-worldbuilding.