ABSTRACT

Tajik National Park struggles with overgrazing, illegal hunting and ill-managed tourism. The designation of the park as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013 was meant to ease some of these struggles, but improvements are thus far difficult to identify. We conducted a case study to understand how local people perceive and interact with the park to probe how these struggles could be mitigated. Interviewees and participants proposed solutions that revolved around the concept of co-management, which we consider as a way to alleviate challenges the park faces today, especially in terms of nature conservation and livelihoods for communities affected by the park. We conclude that engaged community members are willing to help the park improve its management by co-producing knowledge and adapting to social–ecological change if certain conditions, such as improving trust and making trade-offs, are met.

Introduction

Tajik National Park (TNP), created in 1992, was designated as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site in 2013 (IUCN Citation2013). Nevertheless, the park still faces severe issues with overgrazing, illegal hunting and ill-managed tourism. It lacks a robust management plan despite the UNESCO information and guidelines for World Heritage Sites. Because these guidelines lack measures for inclusivity, communities in and near the national park are unaware of most of them and are not involved in the park’s management. Because the UNESCO World Heritage Site designation has not adequately solved the challenges that the TNP’s management faces today, we assess the potential of co-management – a concept that respondents implicitly raised during our first field stay – as a possible strategy for improving the overall management of the park and for decreasing practices that are detrimental to the natural and social environment.

We use the concept of co-management (Carlsson and Berkes Citation2005) to address questions such as whether and how park rangers should involve stakeholders and nearby communities to improve the park’s management and comply with UNESCO requirements. Accordingly, we define co-management as ‘the sharing of power and responsibility between the government and local resource users’ (Berkes Citation2009, 1693). We hypothesize that involving and engaging community members such as herders, traditional hunters and tourist guides would help the park to improve its management in order to develop the World Heritage Site more sustainably. In our case study of potential co-management practices for the park, we focused on community perceptions and propositions from specific local stakeholders about how they would participate in co-management. We explore co-management as a strategy that could provide benefits and alleviate negative effects of protected parks both for the parks themselves and the communities who depend on them.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Following a literature review about community involvement in protected areas, we then provide background information on the current state of the TNP and the involvement of different stakeholders in the management of the park. Subsequently, we explain how we collected, reviewed and analysed the data. We then present our findings and address current issues and opportunities that exist in the TNP. Lastly, we make recommendations for potential collaborative, multi-stakeholder co-management scenarios.

Co-management as a protective practice for communities and parks

Recent scholarship has addressed the creation of national parks and protected areas for improving tourism (Ormsby and Mannle Citation2006), hunting (Mfunda and Røskaft Citation2010; Weaver Citation2013) and economic development (Andam et al. Citation2010; Hein Citation2011). Critical literature has emerged as a response to highlight negative effects that a protected park status can have on communities (Luck Citation2007), for example, resettlement of people due to park protection (Schmidt-Soltau and Brockington Citation2007), loss of wildlife due to ineffective management (Diment, Hotham, and Mallon Citation2012) and harmful economic development trends such as uneven distribution of or dependency on tourism income (Spenceley and Goodwin Citation2007).

Communities around the world have used co-management to manage their natural resources in collaboration with other stakeholders, for example, by integrating community members who possess indigenous knowledge into the wildlife management traditionally run by the state (Berkes Citation2009) or by forming biosphere reserves co-managed by governments and local stakeholders (Plummer and Fennell Citation2009). A number of case studies illustrate how co-management among the state and local communities could work in practice (Olsson, Folke, and Berkes Citation2004; Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2015; Finkbeiner and Basurto Citation2015). Armitage et al. (Citation2011), for example, found that over 30 years of co-management in the Canadian Western Arctic improved decision-making processes and learning among the communities when scientists collaborated with local stakeholders to generate comprehensive knowledge about managing fisheries.

Co-management is appealing to governance and the production of scientific knowledge alike. Recent cases of community-based conservancies outside protected areas in Tajikistan have demonstrated that scientists working with communities to co-generate knowledge improves collaborative decision-making (Shokirov and Backhaus Citation2020). Moreover, co-generated knowledge has been shown to better inform development projects in the region (Shokirov and Backhaus Citation2020). Co-management approaches provide an appealing possibility for conjoining scientific findings with improved governance techniques. In the case of Tajikistan, the three root causes of biodiversity loss are mainly economic (e.g., over-harvesting due to poverty pressure), political (e.g., lack of rules, laws and clear management policies; and tensions caused by a transition to a post-Soviet system and the civil war), and institutional (e.g., lack of cooperation and collaboration among institutions) (Squires and Safarov Citation2013). Drawing upon community knowledge in areas with limited data helps clarify what levels of protection according to scientific findings are needed (Squires and Safarov Citation2013; Haider et al. Citation2018; Shokirov and Backhaus Citation2020).

Co-management can provide a problem-solving approach to many issues regarding the use or protection of natural resources. Baird et al. (Citation2016), for example, showed in two case studies from Canada and Sweden how different types of organization could bring multiple stakeholders together and provide enabling conditions for co-management. Scholars have indicated that a co-management approach allows resource users to better deal with complex issues through increased stakeholder and community participation in the overall management (Castro and Nielsen Citation2001). Co-management serves as a continuous problem-solving process (Carlsson and Berkes Citation2005), bringing local knowledge directly into the decision-making process (Berkes Citation2009). Cinner et al. (Citation2012), for example, found that the implementation of co-management approaches improved the collaboration among resource users and natural resources compared with non-co-managed areas in 42 case studies across five continents. Co-management also provides a decentralized management approach (Carlsson and Berkes Citation2005; Armitage et al. Citation2009). Moreover, Young (2009) argues that the co-management can decrease tensions between tourists and local populations.

Co-management is a dynamic process that needs to be adapted over time and tested by local experiences. We understand adaptive co-management as ‘a process by which institutional arrangements and ecological knowledge are tested and revised in a dynamic, ongoing, self-organized process of learning by doing’ (Folke Citation2002, 20; Citation2004; Berkes, Colding, and Folke Citation2008). Scholars have emphasized that co-management arrangements allow local communities to participate in collaborative research, which generates adaptive responses ‘through production of knowledge that is based on social understanding’ (Berkes and Jolly Citation2002, 13). Co-producing knowledge that includes all stakeholders is seen by communities as an adaptive strategy to deal with change (Armitage et al. Citation2011).

The approaches of co-management and adaptive management, despite their different origins, have merged into the concept of adaptive co-management. Adaptive management (Holling Citation1973) is a process of ‘learning by doing’, where often-interdisciplinary experiences are integrated with scientific information to respond to uncertainty and change (Walters Citation1997). Adaptive management and traditional knowledge systems are often compatible, as both assume that nature is basically unpredictable and cannot be controlled (Berkes, Colding, and Folke Citation2000). Berkes (Citation2009) further emphasizes that co-management systems that cannot adapt cannot respond to changes well, so co-management inherently becomes a form of adaptive management over time.

When planned and implemented well, co-management can improve community livelihoods. For instance, in conservation areas, it can provide opportunities to diversify household income and shift community dependence away from protected forest products to other income sources (Mukul et al. Citation2012). However, in some cases, co-management has failed due to complicated frameworks or a lack of transparency. Cronkleton, Saigal, and Pulhin (Citation2012), for example, found that burdensome frameworks and expensive start-up costs can create barriers for co-management, suggesting that co-management frameworks be simplified to allow greater public participation. Fischer et al. (Citation2014) proposed that co-management should be based on mutual understanding, where no stakeholder is overburdened with management tasks. Also, Nadasdy (Citation2003) argued that, in some cases, co-management had been more reflective of scientists’ views than of communities’. Critics of co-management argue that co-management can be politicized, regardless of (or despite) its success or failure (Nadasdy Citation2005, Citation2012).

TNP in a regional context

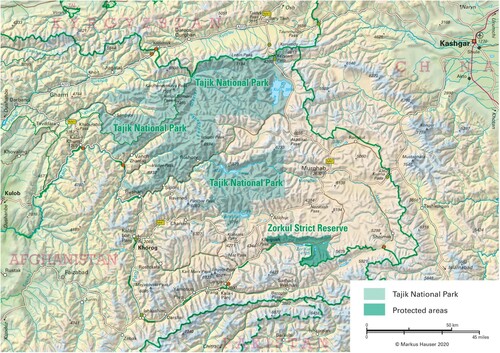

The TNP () was established at the beginning of the Tajik Civil War in 1992 and enlarged in 2005 (Cunha Citation2016; IUCN Citation2013). During the civil war, people struggling with poverty exploited nature reserves for everyday resources in Tajikistan (Cunha 2017). Park areas were profoundly disturbed by deforestation, hunting, grazing and the collection of biomass such as fuel wood. Establishing proper protection and management of the park was impossible in the context of civil war. Research or natural resource inventories were not carried out due to a lack of funding and the unavailability of scientists who were willing to venture in the area (Egorov Citation2002). As a consequence, protected areas still suffer from ecological imbalances due to socio-economic and political crises during the last two decades (Aknazarov, Dadabaev, and Melnichkov Citation2002; PALM Citation2011).

The Committee for Environmental Protection under the government of the Republic of Tajikistan plans and implements management activities in and around the TNP. The park’s management plan includes activities such as wildlife management, recreation, monitoring, scientific research and environmental education (IUCN Citation2013). The current TNP management plan includes four zones: a core zone, a traditional use zone, a limited economic use zone and a recreational zone (Government of Tajikistan Citation2012). Roughly 2000 people reside in five small villages (Bardachev, Rukhch, Pasor, Bopasor and Gudara) within the traditional use zone along the Bartang River, and 14,000 along the border of the limited economic use zone, mostly in the Murgab region. A UNESCO (Citation2013) report claims that communities around the TNP are well-informed and appear to have good knowledge of the boundaries. It further states that many expect tourism activities to bring additional revenues to their communities.

Despite lofty plans and a report stating 54 staff members on the TNP management team (UNESCO Citation2013, 105), researchers have argued that the TNP has neither a sufficient quantity nor quality of staff (Meessen, Maselli, and Haslinger Citation2003; Haslinger et al. Citation2010; PALM Citation2011).

Scholars have shown that the TNP struggles with its current management (as pointed out by Breu, Hurni, and Wirth Stucki Citation2002; Meessen, Maselli, and Haslinger Citation2003; Breu, Maselli, and Hurni Citation2005; Haslinger et al. Citation2010; PALM Citation2011; and Rosen Citation2012). Squires and Safarov (Citation2013) have described the park management’s lack of well-trained and committed staff; lack of tools to implement participatory approaches, scientific research, and technical cooperation at the national, regional and international levels; and lack of a proper management plan.

The geographical isolation of the region along with a brain drain caused by outmigration makes the development, support and control of all these sectors even more challenging. This region is not necessarily peripheral, however: it lay on the ancient Silk Road and is now located on China’s current Belt and Road Initiative, so it remains to be seen how new development will affect the region (Foggin Citation2018). Moreover, the park’s proximity to Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan and China could position it for transboundary conservation cooperation projects. Rosen and Zahler (Citation2016) argued that transboundary cooperation in this region could help to promote collaborative scientific research and species population monitoring, for example, of snow leopards.

Community organization and governance for co-management

Organization and governance in the TNP region are influenced by local administration, politics and traditional institutions. Most villages have an official administration organized by local governments, for example, heads of mahalla (the lowest level of governance) and jamoat (usually a governing body comprising a few villages) (Heathershaw Citation2009; Mostowlansky Citation2017). The Agha Khan Foundation (AKF) has additionally set up village organizations in most villages (Mostowlansky Citation2017) in order to implement local projects. TNP governance could draw upon these existing structures.

In addition to making use of existing governance structures, TNP governance could also benefit from the traditional concept of hashar (volunteer work). Hashar, an important institution in the Pamir region, is sometimes summoned to encourage contribution to communal projects (Haider et al. Citation2019). The hashar system relies on advice and decisions by authorities such as family elders, religious and political leaders to solve communal issues (Boboyorov Citation2013). It shapes collective identities, and Mostowlansky (Citation2012) indicates that the figure of the ‘good man’ – a person with high moral principles – is essential for communal peace and harmony in the Murgab region.Footnote1 Nevertheless, hashar has also been shown to be co-opted for individual political gain (Boboyorov Citation2020).

Recently, the governments of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have started to share decision-making processes and the management of local resources with local communities through decentralized governance approaches (Shigaeva, Dear, and Wolfgramm Citation2012; Haider et al. Citation2018). These approaches have, for example, helped to empower community-level pasture user associations (Shigaeva et al. Citation2012). Alternatively, failing to share decision-making with communities for non-governmental organization (NGO) projects, for example when financing projects without establishing common values and objectives before investing, has been shown to diminish community support (Freizer Citation2005).

Haider et al. (Citation2018) suggest that implementing joint forest management programmes between NGOs and the government would help to improve forest resource management. However, these new approaches need time to be tested and adjusted to locally established rules and need to form ‘enabling conditions for collective actions’ (Haider et al. Citation2018, 18), such as clear rules, systematic monitoring of resources and local leadership. In other words, co-management strategies must be adapted to specific contexts and adjusted over time.

Methods

We chose case study sites within the TNP to investigate whether (and if so, how) the lack of engagement of local communities in the park’s management contributes to the challenges that the TNP is facing. We specifically sought to understand if subtle enforcement measures and community involvement for renegotiating wilderness and wildlife protection measures towards a more sustainable way of resource use would be broadly accepted by the communities.

The first and second authors conducted fieldwork during three visits (each of two to three months) to the Eastern and Western Pamirs from 2015 to 2018. We focused on local people’s perceptions of conservation issues and management practices. We used interviews as well as participatory observation and asked how park management impacts the communities’ livelihoods and who benefits from tourism and hunting concessions. We asked how communities use park resources and to what degree park rangers and communities are involved in planning and implementing the management plans of the park. Moreover, we asked if community stakeholders would be interested in co-management practices and what role they would like to play. We also touched on the capacity-building needs of the community, especially how specific issues could be carried out effectively and efficiently in and around the park.

The primary objective of our first visit was to get to know our interviewees, their villages and livelihood activities and establish a rapport with stakeholders from both the Eastern and Western Pamirs.Footnote2 This introductory visit allowed us to establish relationships and shape our interview questions. Our second and third visits to the same villages allowed us to conduct more formal interviews with stakeholders who were informed about conservation, hunting, grazing, tourism, illegal hunting and generically management issues.

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews in the villages of Karakul, Murgab, Alichur, Bulunkul, Ravmeddara and Khijez and in the town of Khorog. We interviewed 14 TNP rangers, 11 traditional hunters and 39 community members who reside near the park. These interviews provided us with a deeper understanding of conservation and wildlife management issues. We conducted two interviews per day and took notes immediately afterward because many interviewees showed discomfort if the interview was recorded or if the interviewer took written notes, especially when discussing sensitive issues like poaching.

The interviews were conducted either in Russian or Tajik in the Bartang Valley and in Kyrgyz/Uzbek and Russian in Murgab district. The first author speaks all these languages fluently. Community members in Bartang do speak Pamiri dialects (e.g., Shugni and Bartangi) as a first language; however, most of our respondents did not have any difficulties speaking Tajik or Russian, so we did not require a translator.Footnote3

Since building trust was important in working with these communities as outsiders, the first author’s considerable time in the villages (and his two years of previous research experience in the Western and Eastern Pamirs) helped build relationships to encourage open discussion of the TNP and clarify the research intentions. The research included critical issues regarding illegal practices, even though we could not assume that none of our respondents was involved in such practices. Since we were primarily interested to know whether such practices occur and not who committed them, we used contrasting questions such as ‘are you aware of such practices … ’ or ‘we have heard that x and y is happening; what do you think about that?’ so that our interview partners did not have to implicate themselves. Moreover, we protected interviewees’ identities to avoid them from being implicated in such activities.

In addition to interviews, we spent a great amount of time in the field observing herders on summer pastures and rangers conducting wildlife surveys. Overall, we spent three weeks conducting participatory observation: staying with four shepherds in their yurts, joining three rangers on a wildlife-counting mission and accompanying three traditional hunters on hunting trips.

We transcribed and transferred field data into MAXQDA software (VERBI, Citation2017) and coded the data using a mixed approach that combines deductive and inductive coding inspired by grounded theory. Strauss and Corbin (Citation1994, 273) define it as ‘grounded in data systematically gathered and analysed’. Subsequently, we carried out semi-structured interviews with identified groups based on interview guidelines: we structured the interviews enough to focus them on our topics of interest while leaving them as open as possible for new aspects to arise. As our data collection advanced, we adjusted our interview guidelines. For example, we began to see a trend of interview participants suggesting adapted approaches and trade-offs. One herder from the village of Basid said during our first field stay, ‘I would like to graze my sheep in the TNP and I am willing to collaborate with the park to improve the park rangeland resource as long as I am permitted to graze on this land.’ A traditional hunter, similarly, suggesting a willingness to work with regulations as long as they are adapted to local people’s needs, stated:

If I am allowed to hunt for subsistence two to three times a year to provide extra food in winter months, then I am willing to ensure that there is not going to be illegal or excessive hunting in our village.

Throughout the coding process, we were able to identify patterns and storylines that emerged from the data. Some narratives among herders who use the TNP were common: most of the herders were willing to tell us how they use the park, what kind of livestock issues they have and what they would like to be changed through more sustainable park management. Similar narratives emerged among tourist guides and park rangers. We organized these narratives from hunters, park rangers, community members and herders by creating a comprehensive coding system with categories such as ‘ideas for better management of the park’ or ‘obstacles that communities face’. Pooling all the data helped us to understand to what extent communities have used and how they have benefited from the park management, or how communities could benefit by co-managing the park together with other stakeholders.

Results

The analysis of the qualitative data showed generally positive attitudes towards potential co-management of the TNP and how it can further benefit the park’s sustainable development. In the following, we present the perceptions of the local communities and park rangers by addressing key issues such as the lack of scientific studies, extensive grazing, illegal hunting, tourism development, exclusion of local communities on decision-making and insufficient leadership.

Lack of scientific studies

The majority of park rangers we interviewed expressed the need for better scientific studies to support TNP management. Ten of the 14 rangers we interviewed pointed out that the wildlife surveys in the territory of the TNP are conducted arbitrarily rather than systematically. For example, rangers usually survey the animals when they are on duty in the park. Usually, they only conduct counts of the wildlife they see and do not include other parameters such as sex and age. Four other rangers pointed out that they have no experience with wildlife surveys. The park rangers stated that the park does not conduct wildlife-related research due to inadequate staff and lack of funding. All the interviewed TNP employees pointed out that most research or surveys had been carried out only when external donor agencies funded the project. For example, the NGO Panthera funded two studies based on snow leopard surveys between 2011 and 2017 within the territory of the TNP as indicated by park rangers during our interviews. In each of these studies, protected area staff assisted the research project, but external scientists carried out most of the analysis and production for the reports. In order for the management to become more applicable and inclusive of employees, scientific surveys would need to include and improve employees’ knowledge and skills. As a result, co-management would benefit scientific research and build capacity among the park employees. Improved park management would also require more readily available information.

Intensive grazing

All interviewed rangers pointed out that intensive grazing is a major problem in the park. Even though the park claims to have different use zones, those zoning mechanisms are not understood well by the communities. Rangers pointed out that intensive grazing is creating major problems for wild ungulates. For instance, from our participant observation while visiting herders in the park, it became clear that herds are grazing at higher altitudes during summer, thus forcing wildlife to even higher altitudes. Nowadays, herders graze livestock at 3500–4500 masl, in habitats also used by different wildlife species, for example, ibex Capra sibirica and Marco Polo sheep Ovis ammon polii. Rangers acknowledged that the extensive livestock grazing areas directly compete with wildlife grazing areas, but they also pointed out that herders do not have other places to graze their livestock. By implementing different co-management schemes, the park would have the opportunity to manage its pasture resources more sustainably. For example, the park could bring all stakeholders together to negotiate a better deal for herders to graze livestock by implementing more sustainable pasture rotation programmes.

Herders stated that they have been grazing livestock for the past 25 years on these pastures, and the establishment of the park has not yet changed their daily practice. When we asked herders if they apply any conservation technique in grazing patterns, for example, rotational grazing, most of them said no. They pointed out that they usually tend to settle in certain pastures and use them over extended periods, for example, over a whole summer.

Throughout our interviews, we noticed differences between herding communities in the Eastern and Western Pamirs. Inhabitants in the Eastern Pamirs who maintained a nomadic lifestyle at the beginning of the Soviet era now primarily keep a transhumance lifestyle with institutionalized herding practices. All herders are members of the Association of Community Farmers (ACF) and pay a monthly fee depending on the number of livestock they have. The ACF uses this money to lease pasture land from the government, including land in and around the TNP. Moreover, they organize veterinarians and help in emergencies. However, such a practice does not exist in the Western Pamirs, as the communities there tend to be agro-pastoralists and keep smaller numbers of livestock. They also engage in agricultural practices, for example, they keep small gardens and small plots of land on the hills for growing wheat, barley, peas and vegetables. The communities in the Western Pamirs also have access to the ACF, but that association collaborates primarily with farmers who engage in small-scale agriculture and does not yet address livestock issues, as in the Western Pamirs communities tend to be more agro-pastoralists.

Most herders expressed optimism about the idea of contributing to the co-management of the park and using its resources sustainably. They were also optimistic when we asked about implementing joint management plans, for example, rotational grazing. Seven of 11 herders we interviewed already knew about rotational grazing, and some indicated that since this is the primary resource on which they depend, they would like to help to manage pastures. Herders also pointed out that they have no ways of diversifying milk and meat products, for example, by processing them into dried or smoked meat and different types of cheeses to create added value and sell products elsewhere at higher prices. Since the majority of the products are sold and consumed unprocessed, herders do not generate much income from their livestock. Such practices force them to own a higher number of livestock, which stresses pastures even further. Programmes to help diversify production could ease the problem of overgrazing. Herders indicated that they would work with the park as long as they could graze in the park during the summer season.

Illegal hunting

Hunting (of, for example, Marco Polo sheep or ibex) is generally prohibited in the park’s territory without a specific hunting permit (Rosen Citation2012). All rangers pointed out that the park’s large territory is difficult to monitor for illegal hunting, which presents a challenge to managing the park well. Since park boundaries are not clearly demarcated, it is possible that a hunting party could easily cross the boundaries of the park without knowing.

Most of the local hunters we interviewed favoured traditional hunting practices that their predecessors carried out in the region, for example, those in practice before and at the beginning of the Soviet era (Shokirov and Backhaus Citation2020). The majority of the hunters pointed out that they hunt because the experience of hunting allows them to meet the animals and have a special spiritual connection to the wildlife. Eleven hunters we interviewed actively hunt in and around the park for subsistence. They pointed out that, so far, hunting in and around the park is only for trophy hunting. The hunts are commercially sold by different private hunting concessions or community-based conservancies. Usually, the price for a local permit for Tajik nationals is regarded as overpriced, and most hunters cannot afford it. All hunters pointed out that if they were granted specific permits to hunt in and around the park for subsistence, they would continue the traditional practice of sharing the meat with their community. In return, hunters would help the park to manage its wildlife. For example, they suggested that they could participate in wildlife surveys, help eliminate poaching, hunt according to the allocated permits and support accountability. If co-management cases were implemented, the TNP would have entire communities working as rangers, reporting cases of illegal hunting and, most importantly, stop illegally hunting themselves.

Tourism development

There are great expectations of what tourism development could deliver in and around the TNP. The government of Tajikistan has been pushing tourism development over the last decade through different policies, for example, by switching from conservative visa policies to electronic tourist visas upon arrival since 2016 (Shokirov et al. Citation2014).Footnote4 So far, tourism activities in the park include cycling, travelling by motorbikes, trekking and mountaineering. However, tourist activities have provided few economic benefits to local stakeholders. According to the park rangers, the only tourist activity that the park management benefits from is the park entrance fee: 25 Tajikistan somoni (about US$2.20) per visitor per day, plus a possible surcharge for large vehicles such as minibuses. Homestays are the only type of tourism that economically benefits local people. Family-owned guest houses exist in many villages, for example, Karakul, Bulunkul and Basid, which provide amenities including lodging, food and easy access to the TNP. One community member and several park rangers pointed out, however, that the majority of tourists do not need these amenities because they bring their own vehicles and equipment (e.g., tents and cooking utensils) to stay overnight in and around the park.

Most of the community members stated that they enjoy hosting or working with tourists, for example, as guides or cooks. Some of the communities such as Bulunkul and Basid are relatively isolated, and they rarely see and communicate with people not from the region. However, our interviewees from those two villages pointed out that the few tourists who visit them participate in daily activities in and around villages, for example, making carpets from felt. According to the park rangers, tourists usually decide themselves where to go and where to stay overnight in the park, and only the trophy hunters use local guides frequently.

The TNP rangers and nearby community members stated that they support tourism development in the park, but community members said that it is crucial that park authorities address problems arising from tourism by, for example, managing rubbish and providing designated campgrounds. Rangers and herders observed that waste is often simply left behind because waste management is not organized in the park. This littering contributes to the degradation of the environment and impacts wildlife behaviour. Park rangers are willing to build all the necessary infrastructure such as waste management systems or toilets in and around the TNP if they get the funding.

Decision-making, communication and leadership at the TNP

Decision-making in the park is conducted in a top-down management approach. Usually, decisions are taken in the capital city of Dushanbe. Park rangers pointed out that orders usually come from the headquarters in the capital and are implemented by local officials in Murgab and Khorog. Park rangers usually report to the local offices that report back to the headquarters. Due to the park’s geographical isolation, decision-making and implementation processes are slow. Park rangers point out that they would prefer that some of the decisions could be made at the local level to be better able to react to issues when they arise. For example, when the winter season is longer than expected, rangers provide the wildlife with additional hay. However, the order they need to be able to carry out such activities takes 7–10 days to be processed at headquarters.

The majority of herders, park rangers and hunters would prefer to have localized small park offices for selling tickets, storing equipment and keeping hay for harsh winter conditions. They would also like to have a joint management system which would allow for community participation. According to them, the park is now used by many different interest groups for their own reasons and benefits. For example, park rangers want to sell as many tickets as possible while herders want to graze and collect winter hay as much as possible to maximize their benefits from the pastures and impoverished surrounding communities illegally poach for meat. Community members stressed their need to make a living in this isolated part of the country. Since they have no rightful access to the park, they treat it as an exploitable, rather than a sustainable, resource.

Sense of volunteerism, collective decision-making and resource-sharing

As we indicated above, the majority of the interviewees (all rangers, 11 traditional hunters and 31 community members) advocated for user rights and duties to be shared among the villagers or community rather than allocated to specific individuals. However, many of our interviewees also stressed that their commitment is conditional on the possibility of using certain resources from the park. Such initiatives have already taken place, for example, the Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development’s (ACTED) support for a tourism initiative. Only some individuals benefit from these programmes. For example, our interviewees pointed out that in one case where one or two guides received gear but did not share it with others. The residents of Karakul argued that it would be better to initiate agreements to share and co-use resources between the government, International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) and the community.

The majority of the interviewees from the villages argued that such agreements should be set up on a volunteer basis with clear rules and guidelines. For example, they suggested that herders or communities receive pasture use rights in exchange for practicing rotational grazing to avoid pasture degradation, or that a particular hunter might receive a certain number of hunting licences to hunt for the community in the winter months when the villagers need additional food in exchange for not hunting illegally.

Most elders and adult interviewees alike were categorically against any involvement of money and argued against monetarization of development projects. Several village heads argued that as soon as there is profit generation, initiatives usually get privatized and only serve the people who are in power in those villages. Many also assumed that people would only start being part of such initiatives because they expect a monetary gain, and as soon as financing ceases, communities will not show any further interest in the project. One village head suggested instead that such initiatives should be built on the tradition of hashar (collective volunteer work) (Haider et al. Citation2018).

Discussion and conclusions

At the global level, the TNP joins the ranks of many other conservation areas that struggle with overexploitation of natural resources and a lack of financial resources (Schultz, Duit, and Folke Citation2011) which both make them vulnerable to changes such as increasing or decreasing tourist demand or economic and cultural initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road initiative. Our findings contribute to the wider body of literature on the political ecology of conservation as well as to debates on sustainable livelihoods of marginalized people in the Pamir region.

The World Heritage Site designation of the TNP has not improved environmentally problematic practices of hunting groups, tourist guides and shepherds who use the TNP, nor its management. Among others, reasons include a centralized decision-making process with long delays, insufficient financial and human resources, a lack of trust in government agencies, and a lack of opportunities for the local population to participate.

From the perspective of mismanagement, the TNP is similar to the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve of India, as analysed by Bosak (Citation2008): currently, as was evident from our interviews, communities in and around the TNP (as in Nandi Devi) are not aware of rules and regulations, and local leadership of the park does not promote co-management. Nevertheless, all interviewed stakeholders see the potential of shared management and would agree to take responsibility as stewards of the park if they were allowed to co-shape its regulations. Moreover, given the fact that the park does not have adequate resources for its development, co-management could be a means to both protect and use the park’s natural resources in a more sustainable way without added costs.

As a result of discussions and interviews with the park employees and key stakeholders from the community in and around the park, co-management appears to be a promising possibility for improving the management of the park that could lead to diversification of livelihood activities and decrease the communities’ dependence on the park resources, supporting similar findings in studies such as that by Schultz, Duit, and Folke (Citation2011) that look at the effectiveness of different co-management scenarios in 146 biosphere reserve management in 55 countries, or the study by Mukul et al. (Citation2012) which indicates that co-management brought slow but steady improvement to the management of forest resources in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh. For example, herders are willing to implement sustainable pasture practices but are unable to initiate and coordinate such activities because they are not involved in decision-making processes. However, there are many possible ways for the park to work closely with herders and community members to implement co-management approaches and engage stakeholders as resource owners to work together to sustainably manage park resources. Such engagement would benefit stakeholders to improve their understanding of newer management systems, which in return, improves their adaptive capacity (Fernandez-Gimenez et al. Citation2015).

Herders, hunters, rangers and community members are especially important stakeholders to consider in co-management practices. Shepherds already use the park for extensive grazing; if they were involved in co-management, the park would have to introduce efficient, effective and suitable regulations on grazing. The same applies to hunters: Hunters are willing to take the initiative and protect the wildlife and help to carry out wildlife surveys in and around the park and possess traditional ecological knowledge (Shokirov and Backhaus Citation2020). Such co-management approaches would co-produce knowledge based on social understandings (Berkes and Jolly Citation2001) and improve collaboration among resource users (Cinner et al. Citation2012) to help communities to come up with adaptive strategies to deal with change (Armitage et al. Citation2012).

Although the respondents acknowledged these benefits, the question remains why co-management does not occur. The respondents mentioned a lack of clear regulations, which could either mean that indeed there are none (which is only partly true), that people do not know of them, or perhaps that they are aware of them but do not trust that they will be implemented because they see people misusing or bending them. Directly contributing to developing regulations could be a good strategy to increase acceptance rather than relying on regulations from outsiders (i.e., from the capital).

Now would be an opportune time to implement co-management since the decentralized decision-making processes seems to be working elsewhere in Tajikistan, for example, joint forest management (Haider et al. Citation2018). Catalysts for the change could be the ‘good men’ (or women) (Mostowlansky Citation2012, Citation2017) whom people trust and the traditional concept of hashar volunteer work, but the initiative needs to come from the park management agencies (i.e., from the Khorog and Dushanbe TNP Tajik National Park office), as they have the political power to provide platforms for collaborations (Etienne, Du Toit, and Pollard Citation2011). Starting small with some villages could make adaptation processes more flexible. However, it should be emphasized that too often development projects only involve smaller groups of community members from the entire community. Often such cases are interpreted that NGOs and intervention projects are choosing their ‘favourite person’ to work with from those communities. As a result, the larger community often feels that the intervention projects are creating an exclusive group within the larger community which inevitably drives people against each other. In most cases, larger communities have not been equally involved in projects. When co-management cases are about to be implemented, consultation from the whole community should be sought out.

Since tourism is a process that is highly dependent on processes outside the park, the TNP should carefully address tourism’s negative consequences (such as environmental degradation and stakeholder conflict) and involve stakeholders in decisions, planning, implementation, and monitoring of tourism developments in and around the park. For instance, park rangers and community members could be compensated to help to install and maintain designated campsites or collect data on tourist activities in the park. Such enabling conditions would align with the findings of (Plummer and Fennell Citation2009; Schultz, Duit, and Folke Citation2011; Craig, Borrie, and Yung Citation2012) that co-managed protected areas often benefit from community participation. Lastly, the park’s current management could seek more international assistance and collaboration (such as with parks in neighbouring countries), encourage the participation of both local and international scientists to better investigate management and policies for the park’s development. While international assistance needs to be encouraged by the park, local communities should be an integral part in these endeavours. Our case study shows that there is a great potential and willingness in the local population to participate in conservation, even, or especially, in a context of scarce natural resources and a continuing transition to a post-soviet system.

Our results reflect both regional conditions in Central Asia and globally relevant topics of nature conservation management, both pertinent to TNP management. Difficult social and economic conditions in the Pamir region (which commonly lead to out-migration and brain drain; Abdulloev, Epstein, and Gang Citation2020) plus the great physical, social and hierarchical distances to the decision-makers in the capital (Cunha Citation2016) negatively impact the TNP’s management. Regarding the regional conditions for nature conservation, however, the respect for ‘good men’ (Mostowlansky Citation2012, Citation2017), community thinking expressed in the concept of hashar (Haider et al. Citation2018), plus the readiness to work for the greater good rather than for money provide a good basis for the potential success of co-management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Sometimes written as Murghab.

2 The Eastern Pamirs are home mainly to ethnic Kyrgyz who engage in transhumance practice and speak primarily Kyrgyz, but Russian and Tajik are also spoken in the region. The Western Pamirs are home to small-scale agriculturists who speak local Pamiri dialects (Shugni and Wakhi) as well as Tajik and Russian.

3 Older people speak Russian more fluently, while the younger generation is more fluent in Tajik since schooling now is mostly in Tajik.

4 These visa policies are explained on the official government website at https://www.visa.gov.tj (accessed on 23 November 2020).

References

- Abdulloev, I., G. S. Epstein, and I. N. Gang. 2020. “Migration and Forsaken Schooling in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.” IZA Journal of Development and Migration 11 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/izajodm-2020-0004.

- Aknazarov, O., I. Dadabaev, and D. Melnichkov. 2002. “Ecotourism in the Pamir Region: Problems and Perspectives.” Mountain Research and Development 22 (2): 188–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2002)022[0188:EITPRP]2.0.CO;2

- Andam, K. S., P. J. Ferraro, K. R. E. Sims, A. Healy, and M. B. Holland. 2010. “Protected Areas Reduced Poverty in Costa Rica and Thailand.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (22): 9996–10001. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914177107.

- Armitage, D., F. Berkes, A. Dale, E. Kocho-Schellenberg, and E. Patton. 2011. “Co-management and the Co-Production of Knowledge: Learning to Adapt in Canada’s Arctic.” Global Environmental Change 21 (3): 995–1004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006.

- Armitage, D. R., R. Plummer, F. Berkes, R. I. Arthur, A. T. Charles, I. J. Davidson-Hunt, A. P. Diduck, et al. 2009. “Adaptive Co-management for Social–Ecological Complexity.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7 (2): 95–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1890/070089.

- Baird, J., Plummer, R., & Bodin, Ö. 2016. Collaborative governance for climate change adaptation in Canada: Experimenting with adaptive co-management. Regional Environmental Change, 16(3), 747–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0790-5

- Berkes, F. 2009. “Evolution of Co-management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations and Social Learning.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (5): 1692–1702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001.

- Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke. 2000. “Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management.” Ecological Applications 10 (5): 1251–1262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2

- Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke. 2008. Navigating Social–Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berkes, F., & Jolly, D. (2001). Adapting to Climate Change: Social-Ecological Resilience in a Canadian Western Arctic Community. Conservation Ecology, 5(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00342-050218

- Boboyorov, H. 2013. The Ontological Sources of Political Stability and Economy: Mahalla Mediation in the Rural Communities of Southern Tajikistan. Crossroads Asia. www.crossroads-asia.de.

- Boboyorov, H. 2020. “Symbolic Legitimacy of Social Ordering and Conflict Settlement Practices: The Role of Collective Identities in Local Politics of Tajikistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14 (4): 518–533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2020.1790870.

- Bosak, K. 2008. “Nature, Conflict and Biodiversity Conservation in the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve.” Conservation and Society 6 (3): 211. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.49214.

- Breu, T., H. Hurni, and A. Wirth Stucki. 2002. The Tajik Pamirs Challenges of Sustainable Development in an Isolated Mountain Region. Bern: CDE University of Berne.

- Breu, T., D. Maselli, and H. Hurni. 2005. “Knowledge for Sustainable Development in the Tajik Pamir Mountains.” Mountain Research and Development 25 (2): 139–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0139:KFSDIT]2.0.CO;2

- Carlsson, L., and F. Berkes. 2005. “Co-management: Concepts and Methodological Implications.” Journal of Environmental Management 75 (1): 65–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.11.008.

- Castro, A. P., and E. Nielsen. 2001. “Indigenous People and Co-management: Implications for Conflict Management.” Environmental Science & Policy 4 (4–5): 229–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1462-9011(01)00022-3.

- Cinner, J. E., T. M. Daw, T. R. McClanahan, N. Muthiga, C. Abunge, S. Hamed, B. Mwaka, et al. 2012. “Transitions Toward Co-management: The Process of Marine Resource Management Devolution in Three East African Countries.” Global Environmental Change 22 (3): 651–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.03.002.

- Craig, D., W. Borrie, and L. Yung. 2012. ““Blackfeet Belong to the Mountains”: Hope, Loss, and Blackfeet Claims to Glacier National Park, Montana.” Conservation and Society 10 (3): 232. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.101836.

- Cronkleton, P., S. Saigal, and J. Pulhin. 2012. “Co-management in Community Forestry: How the Partial Devolution of Management Rights Creates Challenges for Forest Communities.” Conservation and Society 10 (2): 91. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.97481.

- Cunha, S. F. 2016. “Perestroika to Parkland: The Evolution of Land Protection in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1248551.

- Diment, A., P. Hotham, and D. Mallon. 2012. “First Biodiversity Survey of Zorkul Reserve, Pamir Mountains, Tajikistan.” Oryx 46: 13–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605311002146.

- Egorov, I. 2002. “Perspectives on the Scientific Systems of the Post-Soviet States: A Pessimistic View.” Prometheus 20 (1): 59–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020110110925.

- Etienne, M., D. R. Du Toit, and S. Pollard. 2011. “ARDI: A Co-construction Method for Participatory Modeling in Natural Resources Management.” Ecology and Society 16 (1): 44. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03748-160144

- Fernández-Giménez, M. E., B. Batkhishig, B. Batbuyan, and T. Ulambayar. 2015. “Lessons from the Dzud: Community-Based Rangeland Management Increases the Adaptive Capacity of Mongolian Herders to Winter Disasters.” World Development 68: 48–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.015.

- Finkbeiner, E. M., and X. Basurto. 2015. “Re-Defining Co-management to Facilitate Small-Scale Fisheries Reform: An Illustration from Northwest Mexico.” Marine Policy 51: 433–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2014.10.010.

- Fischer, A., D. T. Wakjira, Y. T. Weldesemaet, and Z. T. Ashenafi. 2014. “On the Interplay of Actors in the Co-management of Natural Resources – A Dynamic Perspective.” World Development 64: 158–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.026.

- Folke, C. 2004. “Traditional Knowledge in Social Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 9 (3). doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01237-090307.

- Folke, C., S. Carpenter, T. Elmqvist, L. Gunderson, C. S. Holling, and B. Walker. 2002. “Resilience and Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations.” Ambio 31: 437–440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-31.5.437.

- Foggin, J. 2018. Environmental Conservation in the Tibetan Plateau Region: Lessons for China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Mountains of Central Asia. Land 7 (2): 52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/land7020052

- Freizer, S. 2005. “Neo-Liberal and Communal Civil Society in Tajikistan: Merging or Dividing in the Post War Period?” Central Asian Survey 24 (3): 223–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930500310295.

- Government of Tajikistan, & Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan. 2012. Tajik National Park (Mountains of the Pamirs). Dushanbe Government of Tajikistan.

- Haider, L. J., W. J. Boonstra, A. Akobirshoeva, and M. Schlüter. 2019. “Effects of Development Interventions on Biocultural Diversity: A Case Study from the Pamir Mountains.” Agriculture and Human Values. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-10005-8.

- Haider, L. J., B. Neusel, G. D. Peterson, and M. Schlüter. 2018. “Past Management Affects Success of Current Joint Forestry Management Institutions in Tajikistan.” Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0132-0.

- Haslinger, A., T. Breu, H. Hurni, and D. Maselli. 2010. “Opportunities and Risks in Reconciling Conservation and Development in a Post-Soviet Setting: The Example of the Tajik National Park.” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystems Services & Management 3: 157–169.

- Heathershaw, J. 2009. Post-Conflict Tajikistan: The Politics of Peacebuilding and the Emergence of Legitimate Order. 1st ed. Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203879214.

- Hein, L. 2011. “Economic Benefits Generated by Protected Areas: The Case of the Hoge Veluwe Forest, the Netherlands.” Ecology and Society 16 (2): art13. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04119-160213.

- Holling, C. S. 1973. “Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4 (1): 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245.

- IUCN. 2013. World Heritage Nomination – IUCN Technical Evaluation Tajik National Park (Mountains of the Pamirs) (Tajikistan). Paris: UNESCO/IUCN.

- Luck, G. W. 2007. “The Relationships Between Net Primary Productivity, Human Population Density and Species Conservation.” Journal of Biogeography 34 (2): 201–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01575.x.

- Meessen, H., D. Maselli, and A. Haslinger. 2003. “Protected Areas in the Former Soviet Union: The Transition to Participation.” Mountain Research and Development 23 (3): 295–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2003)023[0295:PAITFS]2.0.CO;2.

- Mfunda, I. M., and E. Røskaft. 2010. Bushmeat Hunting in Serengeti, Tanzania: An Important Economic Activity to Local People. 10.

- Michel, S., and K. Karimov. 2017. “Recovery of Mountain Ungulates in Tajikistan Through Community-Based Hunting Management.” Pittsburgh IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 2–4.

- Mostowlansky, T. 2012. “Making Kyrgyz Spaces: Local History as Spatial Practice in Murghab (Tajikistan).” Central Asian Survey 31 (3): 251–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2012.723418.

- Mostowlansky, T. 2017. Azan on the Moon: Entangling Modernity Along Tajikistan’s Pamir Highway. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Mukul, S. A., A. Z. M. M. Rashid, S. A. Quazi, M. B. Uddin, and J. Fox. 2012. “Local Peoples’ Responses to Co-management Regime in Protected Areas: A Case Study from Satchari National Park, Bangladesh.” Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 21 (1): 16–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2012.669132.

- Nadasdy, P. 2003. “Re-Evaluating the Co-management Success Story.” Arctic, 56:367–380.

- Nadasdy, P. 2005. “The Anti-Politics of TEK: The Institutionalization of Co-management Discourse and Practice.” Anthropologica 47 (2): 19.

- Nadasdy, P. 2012. “Boundaries Among Kin: Sovereignty, the Modern Treaty Process, and the Rise of Ethno-Territorial Nationalism Among Yukon First Nations.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 54 (03): 499–532. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417512000217.

- Olsson, P., C. Folke, and F. Berkes. 2004. “Adaptive Co-management for Building Resilience in Social–Ecological Systems.” Environmental Management 34 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-003-0101-7.

- Ormsby, A., and K. Mannle. 2006. “Ecotourism Benefits and the Role of Local Guides at Masoala National Park, Madagascar.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 14 (3): 271–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580608669059.

- PALM. 2011. Strategy and Action Plan for Sustainable Land Management in the High Pamir and Pamir-Alai Mountains (GFL-2328-2770-4984; p. 54). UNU-EHS. http://palm.unu.edu.

- Plummer, R., and D. A. Fennell. 2009. “Managing Protected Areas for Sustainable Tourism: Prospects for Adaptive Co-management.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17 (2): 149–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802359301.

- Rosen, T. 2012. Analysing Gaps and Options for Enhancing Argali Conservation in Central Asia. http://www.cms.int/grassland-birds/sites/default/files/publication/Argali%20Assessment_Full%20Report.pdf.

- Rosen, T., and P. Zahler. 2016. “Transboundary Initiatives and Snow Leopard Conservation.” In Snow Leopards, 267–276. Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802213-9.00019-5.

- Schmidt-Soltau, K., and D. Brockington. 2007. “Protected Areas and Resettlement: What Scope for Voluntary Relocation?” World Development 35 (12): 2182–2202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.008.

- Schultz, L., A. Duit, and C. Folke. 2011. “Participation, Adaptive Co-management, and Management Performance in the World Network of Biosphere Reserves.” World Development 39 (4): 662–671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.09.014.

- Shigaeva, J., C. Dear, and B. Wolfgramm. 2012. Sustainable Land Management Background Paper. University of Central Asia, Bishkek MSRC.

- Shokirov, Q., & Backhaus, N. (2020). Integrating hunter knowledge with community-based conservation in the Pamir Region of Tajikistan. Ecology and Society 25 (1): art1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11253-250101

- Shokirov, Q., Abdykadyrova, A., & Dear, C. (2014). Mountain Tourism and Sustainability in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan: A research review. [MSRI Background paper #3. Unpublished manuscript. University of Central Asia].

- Spenceley, A., and H. Goodwin. 2007. “Nature-Based Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: Impacts of Private Sector and Parastatal Enterprises in and Around Kruger National Park, South Africa.” Current Issues in Tourism 10 (2): 255–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.2167/cit305.0.

- Squires, V. R., and N. M. Safarov. 2013. “Diversity of Plants and Animals in Mountain Systems in Tajikistan.” Journal of Rangeland Science 4 (1). https://works.bepress.com/victor_squires/1/.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1994. “Grounded Theory Methodology-An Overview.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by K. D. Norman and S. L. Y. Vannaed, 22–23. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- UNESCO. 2013. Tajik National Park (Mountains of the Pamirs). UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1252.

- VERBI, S. (2017). MAXQDA 2018 Online Manual [English; OSX]. VERBI Software. https://www.maxqda.com/help-max18/welcome

- Walters, C. 1997. “Challenges in Adaptive Management of Riparian and Coastal Ecosystems.” Conservation Ecology 1 (2). doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/CE-00026-010201.

- Weaver, C. 2013. Feasibility Study: The Potential for Sustainable Hunting Management in the Context of the Tajik National Park and the Recently Established Tajik World Heritage Site. Khorog: PANTHERA.