Absract

Our understanding of the relationship between physical activity and health is constantly evolving. Therefore, the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences convened a panel of experts to review the literature and produce guidelines that health professionals might use. In the ABC of Physical Activity for Health, A is for All healthy adults, B is for Beginners, and C is for Conditioned individuals. All healthy adults aged 18–65 years should aim to take part in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities. Moderate-intensity activities are those in which heart rate and breathing are raised, but it is possible to speak comfortably. Vigorous-intensity activities are those in which heart rate is higher, breathing is heavier, and conversation is harder. Aerobic activities should be undertaken in bouts of at least 10 min and, ideally, should be performed on five or more days a week. All healthy adults should also perform muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days a week. Weight training, circuit classes, yoga, and other muscle-strengthening activities offer additional health benefits and may help older adults to maintain physical independence. Beginners should work steadily towards meeting the physical activity levels recommended for all healthy adults. Even small increases in activity will bring some health benefits in the early stages and it is important to set achievable goals that provide success, build confidence, and increase motivation. For example, a beginner might be asked to walk an extra 10 min every other day for several weeks to slowly reach the recommended levels of activity for all healthy adults. It is also critical that beginners find activities they enjoy and gain support in becoming more active from family and friends. Conditioned individuals who have met the physical activity levels recommended for all healthy adults for at least 6 months may obtain additional health benefits by engaging in 300 min or more of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or 150 min or more of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activities. Adults who find it difficult to maintain a normal weight and adults with increased risk of cardiovascular disease or type 2 diabetes may in particular benefit from going beyond the levels of activity recommended for all healthy adults and gradually progressing towards meeting the recommendations for conditioned individuals. Physical activity is beneficial to health with or without weight loss, but adults who find it difficult to maintain a normal weight should probably be encouraged to reduce energy intake and minimize time spent in sedentary behaviours to prevent further weight gain. Children and young people aged 5–16 years should accumulate at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per day, including vigorous-intensity aerobic activities that improve bone density and muscle strength.

1. Introduction

Simple comparisons of men in different occupations provided the first empirical evidence that physical activity was associated with health: the coronary heart disease death rates of physically active bus conductors and postmen were half those of physically inactive bus drivers and telephonists (Morris, Heady, Raffle, Roberts, & Parks, Citation1953a, Citation1953b; Morris, Kagan, Pattison, & Gardner, Citation1966). There is now a wealth of sophisticated epidemiological evidence to demonstrate that physical activity is associated with reduced risk of coronary heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic diseases and conditions (Department of Health, Citation2004). It is estimated that ill-health attributable to physical inactivity costs the National Health Service more than £1.06 billion per year and it is estimated that physical inactivity is directly responsible for more than 35,000 deaths each year in the UK (Allender, Foster, Scarborough, & Rayner, Citation2007).

Physical activity guidelines have changed to reflect our evolving understanding of the relationship between physical activity and health. In the 1970s and 1980s, the available evidence suggested that vigorous-intensity activity and the pursuit of cardiorespiratory fitness were appropriate (the terms cardiorespiratory fitness and aerobic fitness can be used interchangeably and both terms refer to the ability of the lungs, heart, blood, and vascular system to transport oxygen and the ability of the tissues and organs to extract and use oxygen) (American College of Sports Medicine, Citation1978, Citation1990). In the 1990s, it became apparent that moderate-intensity aerobic activity also offered substantial health benefits (Department of Health, Citation1995; Pate et al., Citation1995). In recent years, US guidelines have stated that physical activity goals can be met through various doses of moderate- and/or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (Haskell et al., Citation2007; US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2008). However, British physical activity guidelines have not changed since 2004 (Department of Health, Citation2004). The ABC of Physical Activity for Health was written for an audience of health professionals. Governments and other health-promoting agencies will provide physical activity guidelines that members of the public might read. For example, the British Heart Foundation is currently working with governments in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland to produce updated physical activity guidelines (www.bhfactive.org.uk).

2 The consensus process

It is recommended that a review should not be commissioned if an existing review contains all the evidence needed to inform policy makers and guide practitioners (Glanville & Sowden, Citation2001). The present review was deemed necessary for three interrelated reasons in September 2006. First, it would provide the opportunity to incorporate studies published after the Chief Medical Officer's report on physical activity and health (Department of Health, Citation2004), which reviewed the literature to early 2004 and concluded that children should achieve at least 60 min of at least moderate-intensity physical activity per day and adults should achieve at least 30 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per day on five or more days of the week. Second, the review might help clarify the dose–response relationship between physical activity and health. Third, the review might identify various ways of meeting physical activity goals, in contrast to the “one size fits all” approach in contemporaneous guidelines (Department of Health, Citation2004; Pate et al., Citation1995).

The methods used to produce the ABC of Physical Activity for Health were modelled on those used to produce the Chief Medical Officer's report on physical activity and health (Department of Health, Citation2004). In phase 1, experts produced literature reviews on physical activity and the prevention of overweight and obesity (Ekelund and Gately), physical activity and the prevention of type 2 diabetes (Cooper and Gill), physical activity and the prevention of cardiovascular disease (Hamer and Murphy), physical activity and the prevention of common cancers (Saxton and Crank), physical activity and psychological well-being (Fox and Mutrie), minimal and optimal levels of physical activity and physical fitness (Stamatakis and O'Donovan), physical activity and health in children and adolescents (Reilly and Boreham), and the prevention of musculoskeletal injury (Blazevich and McDermott). The reviewers were asked to consider the dose–response relationship between physical activity and health and to produce a series of evidence statements on the minimal and optimal levels of physical activity in men, women, and any sub-populations that might be at increased risk of chronic diseases. The reviewers specified the type (A–D) and strength (1–3) of evidence in support of each evidence statement using widely recognized definitions (National Cholesterol Education Program, Citation2002). The literature reviews were circulated and discussed during a public meeting at Brunel University in April 2007 and delegates' comments were recorded so that they might contribute to the consensus process. For example, an expert on the built environment and health (Giles-Corti) was recruited in light of delegates' comments. In phase 2, summary reviews were circulated and members of the expert panel communicated by email and conference call until each member approved the recommendations in this document. In phase 3, three independent experts reviewed the document and it was revised in light of their comments.

3 Recommendations: The ABC of Physical Activity for Health

In the ABC of Physical Activity for Health, A is for All healthy adults, B is for Beginners, and C is for Conditioned individuals. This emphasis on appropriate levels for all adults as well as subgroups is novel and important because wide ranges of physical activity experience exist in the general population. All healthy adults are healthy men and women aged 18–65 years and those in the same age range with conditions not associated with inactivity (such as hearing impairment). Physical activity guidelines for older adults are described in detail elsewhere (Nelson et al., Citation2007). Beginners are healthy adults who do not take part in the recommended levels of activity, including those who take part in little or no activity, those who are somewhat active, and those who are resuming an active lifestyle after a period of inactivity. Conditioned individuals are those who have met the physical activity levels recommended for ‘all healthy adults’ for at least 6 months. The key recommendations are summarized in Box 1 and described in this section; the evidence behind the ABC of Physical Activity for Health is summarized in Section 4; physical activity in children and adolescents, adults struggling to maintain normal weight, and adults at increased risk of chronic diseases is discussed in Section 5; screening and injury prevention are discussed in Section 6; an explanation of how beginners might become more active is given in Section 7; and the role of the built environment is discussed in Section 8.

Box 1. Key recommendations in the ABC of Physical Activity for Health.

• Children and adolescents aged 5–16 years should accumulate at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity activity per day, including vigorous-intensity aerobic activities that improve bone density and muscle strength. | |||||

• All healthy adults should take part in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activities. Weight training, circuit classes, and other resistance exercises are a complement to aerobic exercise, and it is recommended that all healthy adults perform 8–10 different exercises on two or more non-consecutive days each week. A resistance (weight) should be selected that brings about local muscular fatigue after 8–12 repetitions of each exercise. | |||||

• Beginners should steadily work towards meeting the physical activity levels recommended for all healthy adults. | |||||

• Conditioned individuals who have met the physical activity levels recommended for all healthy adults for at least 6 months may obtain additional health benefits by engaging in 300 min or more of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, or 150 min or more of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activities. | |||||

• Adults with increased risk of cardiovascular disease or type 2 diabetes may benefit in particular from going beyond the levels of activity recommended for all healthy adults and gradually progressing towards meeting the recommendations for conditioned individuals. | |||||

• Adults who find it difficult to maintain a normal weight may also need to meet the physical activity recommendations for conditioned individuals, reduce energy intake, and minimize sedentary time to reduce the risk of overweight and obesity. | |||||

3.1 All healthy adults

All healthy adults aged 18–65 years should aim to take part in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activities. Moderate-intensity activities are those in which heart rate and breathing are raised, but it is possible to speak comfortably. Vigorous-intensity activities are those in which heart rate is higher, breathing is heavier, and conversation is harder. Aerobic activities should be undertaken in bouts of at least 10 min and, ideally, should be performed on five or more days of the week. All healthy adults should also perform muscle-strengthening activities such as weight training, circuit classes or yoga. Resistance exercise is an important complement to aerobic exercise and the recommended level is equivalent to 8–10 sets (exercises) of 8–12 repetitions on two or more days each week. The major muscle groups should be targeted and a weight or resistance should be chosen that brings about local muscular fatigue at the end of each set. All adults should take every opportunity to be active and should minimize sedentary time because all movement contributes towards daily energy expenditure.

3.2 Beginners

Beginners should work steadily towards meeting the physical activity levels recommended for ‘all healthy adults’. In the early stages, even small increases in activity will bring some health benefits. For example, a beginner might walk an extra 10 min every other day for several weeks before slowly increasing the amount of walking to reach the recommended levels of activity for all healthy adults. Priority should be given to supporting changes in activity patterns rather than the extent to which recommended levels have been met. It is important that beginners set achievable goals that provide success, build confidence. and increase motivation. Finding activities that can be enjoyed and gaining support from friends and family to become more active are both critical for the beginner as they progress towards reaching the physical activity levels recommended for all healthy adults.

3.3 Conditioned individuals

Conditioned individuals who have met the physical activity levels recommended for ‘all healthy adults’ for at least six months may obtain additional health benefits by engaging in 300 min or more of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or 150 min or more of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activities. Heavy resistance training once or twice per week may increase muscular strength, but exceeding the recommended level of resistance training may not offer other benefits. Indeed, a large volume of resistance training may lead to overreaching and overtraining if the balance between training and recovery is inappropriate [overreaching refers to a decrease in performance that may last several days to several weeks and overtraining refers to a decrease in performance that may last several weeks to several months and may be accompanied by greater fatigue, performance decline, and mood disturbance (Halson & Jeukendrup, Citation2004)].

4 The evidence behind the recommendations

Causal relationships between physical activity and cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, and all-cause mortality have been recognized for some time (Allender et al., Citation2007; Paffenbarger, Citation1988; US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation1996). More recently, the pertinent issue has been the dose–response relationship between physical activity and health (Blair, Cheng, & Holder, Citation2001a): What is the minimum dose of activity associated with health and well-being? What doses of activity offer greater health benefits? This section provides evidence for the doses of activity recommended in the ABC of Physical Activity for Health, including evidence from cross-sectional studies, experimental studies, and cohort studies. In a cross-sectional study, risk factors for disease are compared in habitual exercisers and their sedentary counterparts at one particular time. In an experimental study, risk factors for disease are measured before and after an exercise intervention while controlling for potential confounders such as weight loss or a change in diet. In a cohort study, a large number of healthy people are observed over a long period and the incidence of disease or death is compared in groups of different physical activity levels.

4.1 Doses of activity

The doses of activity are the recommended types and amounts of activity. Aerobic activity is the cornerstone of most guidelines and physical activity goals are usually expressed as minutes per day (Pate et al., Citation1995), calories per week (US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation1996) or minutes per week (US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2008). The available evidence suggests that “any activity is better than none” (US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation1996), but the doses recommended in the ABC of Physical Activity for Health are associated with substantial health benefits.

Depending on body weight, 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week or 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week expends around 800–1200 kcal (3349–5023 kJ). Cross-sectional studies and exercise interventions suggest that these doses of activity are associated with favourable changes in blood pressure (Cornelissen & Fagard, Citation2005b; Murphy, Nevill, Murtagh, & Holder, Citation2007), lipid and lipoprotein profiles (Durstine et al., Citation2001; Kodama et al., Citation2007; Shaw, Gennat, O'Rourke, & Del Mar, Citation2006), markers of inflammation (Hamer, Citation2007), insulin sensitivity (Cornelissen & Fagard, Citation2005b), and other risk factors for chronic diseases (Autenrieth et al., Citation2009; El-Sayed, El-Sayed Ali, & Ahmadizad, Citation2004). Evidence is also emerging that 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise per week may improve physical and mental quality of life (Martin, Church, Thompson, Earnest, & Blair, Citation2009) and cognitive function in those aged 45–50 years and older (Lautenschlager et al., Citation2008). Prospective cohort studies suggest that the recommended doses of activity are associated with 20–30% reductions in the risks of cardiovascular disease (Hamer & Chida, Citation2008), type 2 diabetes (Gill & Cooper, Citation2008), depression (Camacho, Roberts, Lazarus, Kaplan, & Cohen, Citation1991; Farmer et al., Citation1988), cognitive impairment in older adults (Laurin, Verreault, Lindsay, MacPherson, & Rockwood, Citation2001; Rovio et al., Citation2005; Scarmeas et al., Citation2009), post-menopausal breast cancer (Monninkhof et al., Citation2007), and all-cause mortality (Blair et al., Citation2001a). Higher doses of activity may be necessary to reduce the risks of other common cancers, such as colon cancer (Samad, Taylor, Marshall, & Chapman, Citation2005) and, possibly, high-grade or advanced prostate cancer (the diagnosis of prostate cancer stages is described online: www.prostate-cancer.org.uk) (Giovannucci, Liu, Leitzmann, Stampfer, & Willett, Citation2005; Nilsen, Romundstad, & Vatten, Citation2006; Patel et al., Citation2005).

The reductions in morbidity and mortality associated with physical activity might sound modest, but they are the most conservative of estimates obtained by statistically isolating physical activity from potential confounders, such as age, smoking habit, cholesterol profile, and blood pressure. Statistical adjustments are appropriate, but it is possible that conservative models underestimate the relationships between physical activity and health. For example, it could be argued that cholesterol profile and blood pressure are mediators on the causal pathway between physical activity and health, rather than confounding variables (Mora, Cook, Buring, Ridker, & Lee, Citation2007). It is also possible that the relationship between physical activity (exposure) and health (outcome) has been underestimated because it has been difficult to measure accurately people's exposure to physical activity (Lee & Paffenbarger, Citation1996). The relationship may become clearer and stronger with the use of accelerometry and other accurate measures of physical activity.

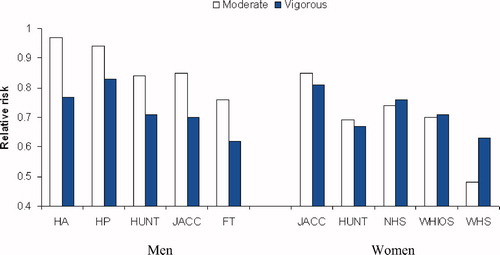

Prospective cohort studies also suggest that there is a dose–response relationship between physical activity and health, which strengthens the argument for causality (). The doses of activity recommended for “conditioned individuals” are similar to the highest doses investigated in many studies and are associated with 40–50% reductions in the risks of chronic diseases and premature death (Blair et al., Citation2001a; G. Hu et al., Citation2004, Citation2005). For example, a recent study of more than 250,000 middle-aged men and women found that cardiovascular disease risk and all-cause mortality risk were reduced by around 40% in those who met “conventional” recommendations (at least 30 min of moderate-intensity activity on most days of the week), by around 40% in those who met “traditional” recommendations (at least 20 min of vigorous-intensity activity three times per week), and by around 50% in those whose activity was equivalent to meeting both recommendations (Leitzmann et al., Citation2007). The continuous nature of the dose–response relationship is such that exceeding the levels of activity recommended for “conditioned individuals” is likely to provide additional health benefits (), although there is probably a “law of diminishing returns” with greater levels of activity offering fewer additional benefits (Department of Health, Citation2004).

Table I. Evidence for a causal relationship between physical activity and reduced risk of chronic diseases, according to Hill's (1965) criteria for causality.

4.1.1 Frequency of activity

The available evidence suggests many ways an adult can meet the physical activity goals of 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week (Haskell et al., Citation2007; US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2008). Studies of “weekend warriors” have shown that taking part in one or two bouts of vigorous-intensity exercise per week can reduce the risk of chronic diseases and premature death (Lee, Sesso, Oguma, & Paffenbarger, Citation2004; Okada et al., Citation2000; Wisloff et al., Citation2006). This approach may suit some people, but there are at least two reasons to believe it may be advantageous to be active more often. First, sedentary behaviour may increase the risk of obesity (Stamatakis, Hirani, & Rennie, Citation2009), depression (van Gool et al., Citation2003), and all-cause mortality (Katzmarzyk, Church, Craig, & Bouchard, Citation2009). Second, single bouts of aerobic activity can lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and improve lipid and lipoprotein profiles for up to 24–48 h (Gill & Hardman, Citation2003; Perseghin et al., Citation1996; Thompson et al., Citation2001; Wojtaszewski & Richter, Citation2006).

4.1.2 Duration of bouts

The Chief Medical Officer's report on physical activity and health tentatively concluded that physical activity goals could be met in 10-min bouts (Department of Health, Citation2004). More recent research supports this conclusion (Altena, Michaelson, Ball, Guilford, & Thomas, Citation2006; Altena, Michaelson, Ball, & Thomas, Citation2004; Murphy, Blair, & Murtagh, Citation2009; Strath, Holleman, Ronis, Swartz, & Richardson, Citation2008). In a recent study of 3250 adults, for example, body mass index (BMI) was 1.2 kg · m−2 lower and waist girth was 2.7 cm smaller in those who accumulated 30 min of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity per day in bouts of 10 min or longer than all other individuals (Strath et al., Citation2008). Although more research is required, there is some evidence that bouts of less than 10 min may also be beneficial to health (Miyashita, Burns, & Stensel, Citation2008; Strath et al., Citation2008). There is also growing evidence that it is beneficial to avoid sitting and other sedentary behaviours (Hamilton, Hamilton, & Zderic, Citation2007; Levine, Citation2007). For example, physical activity (self-reported walking, sports, and exercise) and sedentary behaviour (television and other screen-based entertainment) were independently related to obesity (BMI and waist girth) in the 2003 Scottish Health Survey (Stamatakis et al., Citation2009); and, in recent prospective studies, sitting time was associated with weight gain (Brown, Williams, Ford, Ball, & Dobson, Citation2005) and television watching was associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes (Hu et al., Citation2001) independent of leisure-time physical activity.

4.1.3 Intensity of activity

Physical activity is usually expressed in absolute terms in prospective cohort studies: moderate-intensity is typically characterized as 3–6 METs and vigorous-intensity is typically characterised as >6 METs (where one MET is equivalent to the energy expended at rest). There is compelling evidence of a dose–response relationship between physical activity intensity and cardiovascular disease: activities >6 METs are associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease than activities of 3–6 METs, especially in men (). Experimental studies and cohort studies also suggest that there is a dose–response relationship between physical activity and other chronic diseases and conditions (). “Moderate-intensity” and “vigorous-intensity” activities can be readily identified outside the laboratory using the 6–20 ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) scale (Borg, Citation1998) or the “talk test” (Persinger, Foster, Gibson, Fater, & Porcari, Citation2004). In men and women of all ages, an RPE of 12–13 represents moderate intensity and one of 14–16 vigorous intensity (Demello, Cureton, Boineau, & Singh, Citation1987; Mahon, Duncan, Howe, & Del Corral, Citation1997; Prusaczyk, Cureton, Graham, & Ray, Citation1992). An individual's level of fitness influences his or her perception of effort and – give examples of activities that may be perceived as “moderate” or “hard” (hard is equivalent to vigorous) in men aged 20–79 years of different fitness levels. – give examples of activities that may be perceived as “moderate” or “hard” in women aged 20–69 years of different fitness levels (examples for older women are not provided because fitness norms are not available). The talk test is a simple and effective tool and we define moderate-intensity activities as those in which heart rate and breathing are raised, but it is possible to speak comfortably; while vigorous-intensity activities are those in which heart rate is higher, breathing is heavier, and conversation is harder.

Figure 1. Intensity of physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women. In each of these prospective cohort studies, the reference group is sedentary or inactive, and vigorous activity required ≥6 METs. The most conservative multivariate relative risk is cited. HA is the 15-year Harvard Alumni Health Study of 13,485 men (Lee & Paffenbarger, Citation2000); HP is the 12-year Health Professionals' Follow-Up Study of 44,452 men (Tanasescu, Leitzmann, Rimm, & Hu, Citation2003); HUNT is the 16-year Hunt Study, Norway, of 27,143 men and 28,929 women (Wisloff et al., Citation2006); JACC is the 10-year Japanese Collaborative Cohort Study of 31,023 men and 42,242 women (Noda et al., Citation2005); FT is the 17-year Finnish Twin Cohort of 7925 men (Kujala, Kaprio, Sarna, & Koskenvuo, Citation1998); NHS is the 8-year Nurses' Health Study of 70,102 women (Hu et al., Citation1999); WHIOS is the 3-year Women's Health Initiative Observational Study of 73,743 post-menopausal women (Manson et al., Citation2002); and WHS is the 5-year Women's Health Study of 39,372 women (Lee, Rexrode, Cook, Manson, & Buring, Citation2001).

Table II. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 20–29 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table III. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 30–39 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table IV. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 40–49 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table V. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 50–59 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table VI. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 60–69 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table VII. Perception of effort for various physical activities in men aged 70–79 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table VIII. Perception of effort for various physical activities in women aged 20–29 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table IX. Perception of effort for various physical activities in women aged 30–39 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table X. Perception of effort for various physical activities in women aged 40–49 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table XI. Perception of effort for various physical activities in women aged 50–59 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

Table XII. Perception of effort for various physical activities in women aged 60–69 years of different aerobic fitness levels.

4.2 Muscle strengthening activity

Muscle-strengthening activity or “resistance training” was not explicitly recommended in the Chief Medical Officer's report on physical activity and health (Department of Health, Citation2004). However, there is now sufficient evidence to recommend regular resistance training for all healthy adults because it can lower blood pressure (Cornelissen & Fagard, Citation2005a), improve glucose metabolism (Wojtaszewski, Pilegaard, & Dela, 2008) and reduce cardiovascular disease risk (Tanasescu et al., Citation2002). The available evidence suggests that muscle-strengthening activity should not replace aerobic activity and the dose recommended for “all healthy adults” (around 30 min per week) is probably sufficient for health (Tanasescu et al., Citation2002).

Resistance training may be particularly beneficial in older adults because it may reduce the loss of muscle mass and strength and concomitant loss of independence that may occur with age (Doherty, Citation2003). Resistance training and balance training are particularly beneficial in older adults at risk of falls. In recent US guidelines for men and women aged ≥65 years and those aged 50–64 years with clinically significant chronic conditions and/or functional limitations, the recommended doses of aerobic activity and muscle strengthening activity were similar to those described here for “all healthy adults” and it is recommended that community-dwelling older adults at risk of falls should perform exercises that maintain or improve balance (Nelson et al., Citation2007). The available evidence suggests that general exercise, Tai Chi or a programme of muscle strengthening and balance training may reduce falls (Gillespie et al., Citation2009). More research is required to determine the optimal dose of exercise, but the combination of resistance training and aerobic exercise was more effective in reducing insulin resistance and functional limitation than either modality alone in a recent 6-month study of 136 obese adults aged 60–80 years (functional limitation was assessed using seated arm curls, chair stands, a stepping-in-place test, and a record of the time taken to get out of a chair, walk 2.4 m and return to the seated position in the chair) (Davidson et al., Citation2009).

5 Special groups

The doses of activity recommended in the ABC of Physical Activity for Health are associated with substantial health benefits; however, some groups should be encouraged to take part in greater amounts of activity, including children and adolescents, adults who struggle to maintain normal weight, and other adults with increased risk of chronic diseases.

5.1 Children and adolescents

There is increasing evidence that physical activity in childhood and adolescence is associated with a number of health benefits, including greater bone density (Hind & Burrows, Citation2007), reduced risk of obesity (Ness et al., Citation2007), and reduced clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors (Andersen et al., Citation2006; Ferreira et al., Citation2007). Although more evidence is needed, it is prudent to reiterate that all children and adolescents aged 5–16 years should accumulate at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity activity per day. A variety of activities should be encouraged, including vigorous-intensity aerobic activities that improve bone density and muscle strength.

Physical activity is beneficial at any age and active play is important in physical, mental, and social aspects of growth and development. It is difficult to assess physical activity in children, but there is some evidence that many children and adolescents take part in considerably less activity than is recommended (Reilly et al., Citation2004; Riddoch et al., Citation2007); and there is some evidence that physical activity levels decline between ages 9 and 15 years (Nader, Bradley, Houts, McRitchie, & O'Brien, Citation2008).

5.2 Adults struggling to maintain normal weight

Body mass index and waist circumference are commonly used to define overweight and obesity and includes definitions for Caucasians and includes definitions for Asians and other ethnic groups. Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk of depression, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers (Bianchini, Kaaks, & Vainio, Citation2002; Herva et al., Citation2006; F. B. Hu et al., Citation2004; G. Hu et al., Citation2005). The amount of activity required to prevent weight gain varies from one individual to the next (Saris et al., Citation2003) and combined diet and exercise interventions are more effective in reducing weight than either intervention alone (Curioni & Lourenco, Citation2005; Wu, Gao, Chen, & van Dam, Citation2009). The available evidence suggests that adults who find it difficult to maintain a normal weight may need to reduce energy intake, minimize sedentary time, and may need to go beyond the levels of activity recommended for “all healthy adults” and gradually progress towards meeting the recommendations for “conditioned individuals” to prevent overweight and obesity (that is, around 300 min or more of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or around 150 min or more of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity). It is important to stress that aerobic activity offers substantial health benefits even if weight is not lost (Hamer & O'Donovan, Citation2009; Shaw et al., Citation2006). It is also important to stress that substantial weight loss is difficult to achieve and health and fitness professionals should also consider more realistic short-term goals for overweight and obese individuals, such as reaching physical activity targets and improving aerobic fitness.

Table XIII. Classification of overweight and obesity by body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and associated disease risks in Caucasians.

Table XIV. Classification of overweight and obesity by body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and associated disease risks in Asians*.

5.3 Adults with increased risk of chronic diseases

Genetic factors and lifestyle factors interact to determine one's risk of chronic diseases and it is possible to identify some groups with increased risk of chronic diseases. Those with increased risk of cardiovascular disease include smokers and those with two or more of the following risk factors: smoking, physical inactivity, total cholesterol >5 mmol · l−1, diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg or systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg, overweight or obesity (Emberson, Whincup, Morris, & Walker, Citation2003; Emberson, Whincup, Morris, Wannamethee, & Shaper, Citation2005; Vasan, Larson, Leip, Kannel, & Levy, Citation2001). Adults with increased risk of type 2 diabetes include: those with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance; those with a family history of the disease; and overweight or obese individuals (as defined in and ). Although adults with increased risk of chronic diseases will derive substantial health benefits from taking part in the levels of activity recommended for “all healthy adults”, the available evidence suggests that those with increased risk of cardiovascular disease or type 2 diabetes may benefit in particular from going beyond the levels of activity recommended for “all healthy adults” and gradually progressing towards meeting the recommendations for “conditioned individuals” (that is, around 300 min or more of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or around 150 min or more of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, or equivalent combinations of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity). There is insufficient evidence to identify doses of activity that might be especially beneficial in those with a family history of breast cancer, colon cancer or prostate cancer.

6 Screening and injury prevention

The benefits of exercise far outweigh the risks (Thompson et al., Citation2007); however, the risks of injury should not be ignored because injury poses a burden on the healthcare system, is emotionally costly, and may be a deterrent to future activity. To reduce the risk of heart attack and death, we encourage health and fitness professionals to use the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q, available at www.csep.ca) and to follow the detailed guidelines on screening and risk stratification of the American Heart Association and American College of Sports Medicine (Balady et al., Citation1998; Fletcher et al., Citation2001). “Musculoskeletal injury” can be defined as an acute impairment that prohibits physical activity. A number of strategies may reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injury, including an active warm-up, the use of footwear that is appropriate to the activity, the use of footwear that is appropriate to the individual's running technique, and the use of ankle taping/bracing in sports where rapid changes of direction are commonplace (Bahr, Citation2006). Walking may be an appropriate form of exercise for beginners because it is associated with a lower risk of musculoskeletal injury than running and sports participation (Hootman et al., Citation2001). There is some evidence that the risk of musculoskeletal injury is reduced with “injury prevention programmes” consisting of various components, such as warming-up, stretching, strength training, and balance training; however, it is impossible to distinguish the influence of each component.

7 Special considerations for beginners

In the 2008 Health Survey for England, around 60% of men and 70% of women aged 25–64 years reported taking part in less than 30 min of moderate-intensity physical activity on five or more days of the week (Roth, 2009). Levels of inactivity are similar in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Helping individuals with little or no experience of exercise to initiate a physical activity programme and establish regular activity patterns in their lives is a key priority for health professionals and policy makers because physical activity may be particularly beneficial in those whose activity levels are very low (Department of Health, Citation2009). Establishing some exercise is also a necessary precursor to progressing to more frequent and more intense activity that can bring additional health benefits. Here we present a set of evidence-based considerations for helping the least active begin to achieve some regular activity.

7.1 Who is doing little or no health-enhancing physical activity?

There is an age-related decline in physical activity and females seem to be less active than males at every age: on average, 53% of males and 35% of females aged 16–24 years, 45% of males and 34% of females aged 25–54 years, 26% of males and 23% of females aged 55–74 years, and nine percent of males and six percent of females aged 75 years or older reported taking part in at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on five or more days of the week in the 2008 Health Survey for England (Roth, 2009). Adherence to contemporaneous physical activity guidelines was lower than average in the obese (Zaninotto, Head, Stamatakis, Wardle, & Mindell, Citation2009), those with chronic disease (Stamatakis, Hamer, & Primatesta, Citation2009), those with low household income, and all ethnic minorities other than Black Caribbean and Irish populations (Department of Health, Citation2009).

7.2 Challenges to beginners

Well-recognized challenges to undertaking more activity apply to the general population. The most common barriers stated by those in the working age population are time related and refer to work commitments, lack of leisure time, and caring responsibilities (Craig & Shelton, Citation2008; Trost, Owen, Bauman, Sallis, & Brown, Citation2002). Other commonly reported factors are not having enough money, nobody to exercise with, and no suitable places to exercise. There is a modest relationship throughout the lifespan between physical self-perception and exercise and sport participation, with those perceiving low physical competence or confidence being less likely to be active. Some middle-aged adults and some older adults associate physical activity with “athleticism” or “being sporty”, and those who do not identify with these notions may be less likely to become more active.

A number of other barriers must be overcome if needy and inactive groups are to become more active. Many older adults face real and perceived barriers to becoming more active, including physical limitations and a lack of confidence. Older adults and overweight adults may also find physical activity demanding and embarrassing. Some ethnic minorities, particularly women, face serious cultural barriers to a more active lifestyle. An increase in physical activity may also be difficult and unlikely in low socio-economic groups and those of lower educational level because these groups tend to have limited capacity to self-manage, they may face financial stresses, and they tend to attach little value or priority to healthy behaviours. The environment where an individual resides and works must also be considered when encouraging beginners to become more active. At a simple level, making the active choice the easy choice is only possible when the environment is considered: for example, asking a person to consider walking part of the way to work is only feasible when public transport or parking is easily available in the environment (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Citation2008a).

7.3 Activity promotion principles

Socio-behavioural approaches have been developed and adopted to help people, especially those who are initially very inactive, build regular physical activity patterns. These approaches have involved contact with an exercise professional (often called a facilitator) using principles of behaviour change derived from motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy, and health counselling. They are theory rich and call upon attitudinal/belief, self-perception, self-determination, self-efficacy, social support models and theories, and offer the best bet for assisting in the process of helping people change their behaviours (Biddle & Mutrie, Citation2008; Kirk, Barnett, & Mutrie, Citation2007; Rollnick et al., Citation2005). These techniques are all recognized as appropriate, theoretically driven approaches to behaviour change in health settings (Abraham & Michie, Citation2008) and are recommended as general behaviour change principles (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Citation2007). In the exercise field, these techniques have manifested in physical activity consultation (Kirk et al., Citation2007) and exercise facilitation approaches (Fox, Citation1992). They combine supportive communication styles and strategies that facilitate behaviour change, and many of the principles and strategies have become standard features of websites, self-help guides, and books (Blair, Dunn, Marcus, Carpenter, & Jaret, Citation2001b; Hunt & Hillsdon, Citation1996). With these developments, subtle changes in semantics and phrasing have emerged: for example, “prescription” has been replaced by “facilitation” or “negotiation”, and the emphasis in programming has shifted from physiological parameters such as exercise intensity and percentage of capacity, to social psychological principles to guide interactions with participants. Box 2 identifies strategies to help initiate and sustain physical activity and Appendix 1 provides a case study. Biddle and Mutrie (Citation2008) provide a more detailed explanation of the behaviour change strategies that might be used to help individuals and groups become more physically active.

Box 2. Strategies that may help initiate and sustain physical activity.

• Help participants develop realistic expectations and a sense of patience and commitment. | |||||

• Help participants understand that the most important factor is building and sustaining regular engagement in physical activity. This should be prioritized and rewarded and celebrated through strategies and interactions. Fitness change and weight loss are secondary and more long-term goals. | |||||

• Help participants achieve steady progression through careful setting of short-term goals that have an element of flexibility. It does not matter how small the increment is from one goal to another so long as it shows improvement. | |||||

• Focus on building confidence, competence, and pride in achievements through steady progression. | |||||

• Focus on helping the participant take responsibility in decision making and experience ownership for change to encourage self-determination and confidence. | |||||

• Help participants understand the importance of social support and explore ways in which they can find it. | |||||

• Help participants identify activity opportunities in their daily lives and the localities in which they live and work. | |||||

8 The built environment

The built environment has been defined as “the neighbourhoods, roads, buildings, food sources and recreational facilities in which people live, work, are educated, eat and play” (Sallis & Glanz, Citation2006, p. 90). There is a growing body of cross-sectional evidence to suggest that the built environment impacts on physical activity, particularly walking. Studies consistently show that adults are more likely to walk for transport in compact, pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods characterized by connected street networks, access to mixed-use planning, the presence of places to walk to (such as public transport hubs, delicatessens, and newsagents), and in neighbourhoods with higher population densities (Duncan & Mummery, Citation2005; Owen, Humpel, Leslie, Bauman, & Sallis, Citation2004; Transportation Research Board, Citation2005). Fewer studies have considered environmental factors associated with recreational walking, which appear to be related to a neighbourhood's aesthetics (Owen et al., Citation2004) rather than its “walkability” (that is, neighbourhoods characterized by higher connectivity of street networks, the presence of mixed-use planning, and higher population density) (Owen et al., Citation2007). Moreover, high levels of walking have been shown to be associated with access to high-quality large public open space (Giles-Corti et al., Citation2005), but not access to public open space irrespective of its size or quality (Pikora et al., Citation2006). This suggests that encouraging more physical activity in adults may require not just accessibility to walkable neighbourhoods, but that greater attention needs to be given to designing attractive and convivial neighbourhoods and facilities.

Neighbourhood design is also a powerful determinant of physical activity in young people. There is substantial evidence that the active transport behaviours of children in developed countries have declined in the last two decades (Bradshaw, Citation2001; Harten & Olds, Citation2004). Between 1984 and 1993, for example, kilometres walked per year declined by 20% in children under 15 years of age in the UK (particularly in girls) (Roberts, Citation1996), and these trends appear to have continued (Andersen, Citation2007).

Children who actively commute to school accumulate more daily physical activity than others (Faulkner, Buliung, Flora, & Fusco, Citation2009) and children's active transport is influenced by traffic congestion and real and perceived parental concerns about safety (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2002; Jago & Baranowski, Citation2004; Lam, Citation2001a, Citation2001b). In primary school children, important impediments to parents allowing their children to use active modes of transport include their concerns or dissatisfaction with traffic danger (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2002; Harten & Olds, Citation2004), lack of safe crossings infrastructure (Timperio, Crawford, Telford, & Salmon, Citation2004), and concerns for personal safety (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2002; DiGuiseppi, Roberts, Li, & Allen, Citation1998). Moreover, girls aged 10–12 years whose parents perceived there were several roads to cross, limited public transport, and no parks nearby were less likely to walk or cycle regularly to destinations (Timperio et al., Citation2004). In boys, only parental perceptions of no traffic lights/crossings decreased their likelihood of being active.

The best available evidence on the impact of the built environment on physical activity relates to walking for transport. However, there are many forms of physical activity (such as walking for recreation, team sport participation, active play, and cycling) and, unless carefully planned for, many of these may not be supported by infrastructure in highly urbanized, walkable neighbourhoods (Giles-Corti & King, Citation2009). Although specific evidence on each of these behaviours may not be available at the present time, it is critical to plan neighbourhoods that cater for multiple forms of physical activity across the life course. For example, numerous studies have shown that the presence of public spaces is associated with higher moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity in young people (especially parks with sports pitches, sports centres, and recreation centres), whether behaviour is objectively measured (Cohen et al., Citation2006; Epstein et al., Citation2006; Evenson, Scott, Cohen, & Voorhees, Citation2007) or self-reported (Brodersen, Steptoe, Williamson, & Wardle, Citation2005; Frank, Kerr, Chapman, & Sallis, Citation2007; Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page, & Popkin, Citation2006). However, children's use of local recreational and sporting facilities may be limited if parents do not provide transportation (Hoefer, McKenzie, Sallis, Marshall, & Conway, Citation2001) and some parents struggle to manage conflicting professional and family commitments (McBride, Citation1990).

Although much of the evidence to date is cross-sectional and the evidence base is still being developed, there is growing recognition internationally that there is sufficient evidence to warrant public health action to create environments that support physical activity (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Citation2008b; National Preventative Health Taskforce, Citation2008; Transportation Research Board, Citation2005).

References

- Abraham , C. and Michie , S. 2008 . A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions . Health Psychology , 27 : 379 – 387 .

- Ainsworth , B. E. , Haskell , W. L. , Leon , A. S. , Jacobs , D. R. , Montoye , H. J. Sallis , J. F. 1993 . Compendium of Physical Activities: Classification of energy costs of human physical activities . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 25 : 71 – 80 .

- Ainsworth , B. E. , Haskell , W. L. , Whitt , M. C. , Irwin , M. L. , Swartz , A. M. Strath , S. J. 2000 . Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 32 ( suppl. ) : S498 – S504 .

- Alberti , K. G. , Zimmet , P. and Shaw , J. 2005 . The metabolic syndrome – a new worldwide definition . Lancet , 366 ( 9491 ) : 1059 – 1062 .

- Allender , S. , Foster , C. , Scarborough , P. and Rayner , M. 2007 . The burden of physical activity-related ill health in the UK . Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health , 61 : 344 – 348 .

- Altena , T. S. , Michaelson , J. L. , Ball , S. D. , Guilford , B. L. and Thomas , T. R. 2006 . Lipoprotein subfraction changes after continuous or intermittent exercise training . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 38 : 367 – 372 .

- Altena , T. S. , Michaelson , J. L. , Ball , S. D. and Thomas , T. R. 2004 . Single sessions of intermittent and continuous exercise and postprandial lipemia . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 36 : 1364 – 1371 .

- American College of Sports Medicine . 1978 . The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining fitness in healthy adults . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 10 ( 3 ) : vii – x .

- American College of Sports Medicine . 1990 . The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness in healthy adults . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 22 : 265 – 274 .

- American College of Sports Medicine . 1998 . The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 30 ( 6 ) : 975 – 991 .

- Andersen , L. B. 2007 . Physical activity and health . British Medical Journal , 334 ( 7605 ) : 1173

- Andersen , L. B. , Harro , M. , Sardinha , L. B. , Froberg , K. , Ekelund , U. Brage , S. 2006 . Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: A cross-sectional study (The European Youth Heart Study) . Lancet , 368 ( 9532 ) : 299 – 304 .

- Autenrieth , C. , Schneider , A. , Doring , A. , Meisinger , C. , Herder , C. Koenig , W. 2009 . Association between different domains of physical activity and markers of inflammation . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 41 : 1706 – 1713 .

- Bahr , R. 2006 . “ Principles of injury prevention ” . In Clinical sports medicine , 3rd edn , Edited by: Brukner , P. and Khan , K. 78 – 101 . Sydney, NSW : McGraw-Hill .

- Balady , G. J. , Chaitman , B. , Driscoll , D. , Foster , C. , Froelicher , E. Gordon , N. 1998 . Recommendations for cardiovascular screening, staffing, and emergency policies at health/fitness facilities . Circulation , 97 : 2283 – 2293 .

- Bianchini , F. , Kaaks , R. and Vainio , H. 2002 . Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk . Lancet Oncology , 3 : 565 – 574 .

- Biddle , S. J. H. and Mutrie , N. 2008 . Psychology of physical activity: Determinants, well-being and interventions , London : Routledge .

- Blair , S. N. , Cheng , Y. and Holder , J. S. 2001a . Is physical activity or physical fitness more important in defining health benefits? . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 33 (suppl.) : S379 – S399 .

- Blair , S. N. , Dunn , A. L. , Marcus , B. H. , Carpenter , R. A. and Jaret , P. 2001b . Active living every day: 20 steps to lifelong vitality , Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics .

- Borg , G. 1998 . Borg's perceived exertion and pain scales , Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics .

- Bradshaw , R. 2001 . School children's travel – the journey to school . Geography , 86 : 77 – 78 .

- Brodersen , N. H. , Steptoe , A. , Williamson , S. and Wardle , J. 2005 . Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12 . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 29 : 2 – 11 .

- Brown , W. J. , Williams , L. , Ford , J. H. , Ball , K. and Dobson , A. J. 2005 . Identifying the energy gap: Magnitude and determinants of 5-year weight gain in midage women . Obesity Research , 13 : 1431 – 1441 .

- Camacho , T. C. , Roberts , R. E. , Lazarus , N. B. , Kaplan , G. A. and Cohen , R. D. 1991 . Physical activity and depression: Evidence from the Alameda County Study . American Journal of Epidemiology , 134 : 220 – 231 .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2002 . Barriers to children walking and biking to school – United States, 1999 . Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report , 51 ( 32 ) : 701 – 704 .

- Cohen , D. A. , Ashwood , S. , Scott , M. , Overton , A. , Evenson , K. R. Voorhees , C. C. 2006 . Proximity to school and physical activity among middle school girls: The Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls Study . Journal of Physical Activity and Health , 3 ( suppl. 1 ) : S129 – S138 .

- Cornelissen , V. A. and Fagard , R. H. 2005a . Effect of resistance training on resting blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Journal of Hypertension , 23 : 251 – 259 .

- Cornelissen , V. A. and Fagard , R. H. 2005b . Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure-regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors . Hypertension , 46 : 667 – 675 .

- Craig , R. and Shelton , N. 2008 . Health Survey for England 2007. Healthy lifestyles: Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour , London : Health and Social Care Information Centre .

- Curioni , C. C. and Lourenco , P. M. 2005 . Long-term weight loss after diet and exercise: A systematic review . International Journal of Obesity (London) , 29 : 1168 – 1174 .

- Davidson , L. E. , Hudson , R. , Kilpatrick , K. , Kuk , J. L. , McMillan , K. Janiszewski , P. M. 2009 . Effects of exercise modality on insulin resistance and functional limitation in older adults: A randomized controlled trial . Archives of Internal Medicine , 169 : 122 – 131 .

- Demello , J. J. , Cureton , K. J. , Boineau , R. E. and Singh , M. M. 1987 . Ratings of perceived exertion at the lactate threshold in trained and untrained men and women . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 19 : 354 – 362 .

- Department of Health . 1995 . More people, more active, more often. Physical activity in England: A consultation paper , London : The Stationery Office .

- Department of Health . 2004 . At least five a week: Evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health , London : DoH .

- Department of Health . 2009 . Be active, be healthy: A plan for getting the nation moving , London : DoH .

- DiGuiseppi , C. , Roberts , I. , Li , L. and Allen , D. 1998 . Determinants of car travel on daily journeys to school: Cross-sectional survey of primary school children . British Medical Journal , 316 ( 7142 ) : 1426 – 1428 .

- Doherty , T. J. 2003 . Invited review: Aging and sarcopenia . Journal of Applied Physiology , 95 : 1717 – 1727 .

- Duncan , M. and Mummery , K. 2005 . Psychosocial and environmental factors associated with physical activity among city dwellers in regional Queensland . Preventive Medicine , 40 : 363 – 372 .

- Durstine , J. L. , Grandjean , P. W. , Davis , P. G. , Ferguson , M. A. , Alderson , N. L. and DuBose , K. D. 2001 . Blood lipid and lipoprotein adaptations to exercise: A quantitative analysis . Sports Medicine , 31 : 1033 – 1062 .

- El-Sayed , M. S. , El-Sayed Ali , Z. and Ahmadizad , S. 2004 . Exercise and training effects on blood haemostasis in health and disease: An update . Sports Medicine , 34 : 181 – 200 .

- Emberson , J. R. , Whincup , P. H. , Morris , R. W. and Walker , M. 2003 . Re-assessing the contribution of serum total cholesterol, blood pressure and cigarette smoking to the aetiology of coronary heart disease: Impact of regression dilution bias . European Heart Journal , 24 : 1719 – 1726 .

- Emberson , J. R. , Whincup , P. H. , Morris , R. W. , Wannamethee , S. G. and Shaper , A. G. 2005 . Lifestyle and cardiovascular disease in middle-aged British men: The effect of adjusting for within-person variation . European Heart Journal , 26 : 1774 – 1782 .

- Epstein , L. H. , Raja , S. , Gold , S. S. , Paluch , R. A. , Pak , Y. and Roemmich , J. N. 2006 . Reducing sedentary behavior: The relationship between park area and the physical activity of youth . Psychological Science , 17 : 654 – 659 .

- Evenson , K. R. , Scott , M. M. , Cohen , D. A. and Voorhees , C. C. 2007 . Girls' perception of neighborhood factors on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and BMI . Obesity (Silver Spring) , 15 : 430 – 445 .

- Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight in Adults . 1998 . Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Executive summary . American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 68 : 899 – 917 .

- Farmer , M. E. , Locke , B. Z. , Moscicki , E. K. , Dannenberg , A. L. , Larson , D. B. and Radloff , L. S. 1988 . Physical activity and depressive symptoms: The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study . American Journal of Epidemiology , 128 : 1340 – 1351 .

- Faulkner , G. E. , Buliung , R. N. , Flora , P. K. and Fusco , C. 2009 . Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: A systematic review . Preventive Medicine , 48 : 3 – 8 .

- Ferreira , I. , Boreham , C. A. , Twisk , J. W. , Gallagher , A. M. , Young , I. S. Murray , L. J. 2007 . Clustering of metabolic syndrome risk factors and arterial stiffness in young adults: The Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project . Journal of Hypertension , 25 : 1009 – 1020 .

- Fletcher , G. F. , Balady , G. J. , Amsterdam , E. A. , Chaitman , B. , Eckel , R. Fleg , J. 2001 . Exercise standards for testing and training: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association . Circulation , 104 : 1694 – 1740 .

- Fox , K. R. 1992 . “ A clinical approach to exercise in the markedly obese ” . In Treating the severely obese patient , Edited by: Wadden , T. A. and Van Itallie , T. B. 354 – 381 . New York : Guilford Press .

- Frank , L. , Kerr , J. , Chapman , J. and Sallis , J. 2007 . Urban form relationships with walk trip frequency and distance among youth . American Journal of Health Promotion , 21 ( suppl. ) : 305 – 311 .

- Giles-Corti , B. , Broomhall , M. H. , Knuiman , M. , Collins , C. , Douglas , K. Ng , K. 2005 . Increasing walking: How important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 28 ( suppl. 2 ) : 169 – 176 .

- Giles-Corti , B. and King , A. C. 2009 . Creating active environments across the life course: “Thinking outside the square” . British Journal of Sports Medicine , 43 : 109 – 113 .

- Gill , J. M. and Cooper , A. R. 2008 . Physical activity and prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus . Sports Medicine , 38 : 807 – 824 .

- Gill , J. M. and Hardman , A. E. 2003 . Exercise and postprandial lipid metabolism: An update on potential mechanisms and interactions with high-carbohydrate diets (review) . Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry , 14 : 122 – 132 .

- Gillespie , L. D. , Robertson , M. C. , Gillespie , W. J. , Lamb , S. E. , Gates , S. Cumming , R. G. 2009 . Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 2 : CD007146

- Giovannucci , E. L. , Liu , Y. , Leitzmann , M. F. , Stampfer , M. J. and Willett , W. C. 2005 . A prospective study of physical activity and incident and fatal prostate cancer . Archives of Internal Medicine , 165 : 1005 – 1010 .

- Glanville , J. and Sowden , A. 2001 . “ Planning the review ” . In Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews , Edited by: Khan , K. S. , ter Riet , G. , Glanville , J. , Sowden , A. and Kleijnen , J. York : NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination .

- Gordon-Larsen , P. , Nelson , M. C. , Page , P. and Popkin , B. M. 2006 . Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity . Pediatrics , 117 : 417 – 424 .

- Halson , S. L. and Jeukendrup , A. E. 2004 . Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research . Sports Medicine , 34 : 967 – 981 .

- Hamer , M. 2007 . The relative influences of fitness and fatness on inflammatory factors . Preventive Medicine , 44 : 3 – 11 .

- Hamer , M. and Chida , Y. 2008 . Walking and primary prevention: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies . British Journal of Sports Medicine , 42 : 238 – 243 .

- Hamer , M. and O'Donovan , G. 2009 . Cardiorespiratory fitness and metabolic risk factors in obesity . Current Opinion in Lipidology , 21 : 1 – 7 .

- Hamilton , M. T. , Hamilton , D. G. and Zderic , T. W. 2007 . Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease . Diabetes , 56 : 2655 – 2667 .

- Harten , N. and Olds , T. 2004 . Patterns of active transport in 11–12 year old Australian children . Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health , 28 : 167 – 172 .

- Haskell , W. L. , Lee , I. M. , Pate , R. R. , Powell , K. E. , Blair , S. N. Franklin , B. A. 2007 . Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association . Circulation , 116 : 1081 – 1093 .

- Herva , A. , Laitinen , J. , Miettunen , J. , Veijola , J. , Karvonen , J. T. Laksy , K. 2006 . Obesity and depression: Results from the longitudinal Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study . International Journal of Obesity (London) , 30 : 520 – 527 .

- Hill , A. B. 1965 . The environment and disease: Association or causation . Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine , 58 : 295 – 300 .

- Hind , K. and Burrows , M. 2007 . Weight-bearing exercise and bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents: A review of controlled trials . Bone , 40 : 14 – 27 .

- Hoefer , W. R. , McKenzie , T. L. , Sallis , J. F. , Marshall , S. J. and Conway , T. L. 2001 . Parental provision of transportation for adolescent physical activity . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 21 : 48 – 51 .

- Hootman , J. M. , Macera , C. A. , Ainsworth , B. E. , Martin , M. , Addy , C. L. and Blair , S. N. 2001 . Association among physical activity level, cardiorespiratory fitness, and risk of musculoskeletal injury . American Journal of Epidemiology , 154 : 251 – 258 .

- Hu , F. B. , Leitzmann , M. F. , Stampfer , M. J. , Colditz , G. A. , Willett , W. C. and Rimm , E. B. 2001 . Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men . Archives of Internal Medicine , 161 : 1542 – 1548 .

- Hu , F. B. , Sigal , R. J. , Rich-Edwards , J. W. , Colditz , G. A. , Solomon , C. G. Willett , W. C. 1999 . Walking compared with vigorous physical activity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: A prospective study . Journal of the American Medical Association , 282 : 1433 – 1439 .

- Hu , F. B. , Willett , W. C. , Li , T. , Stampfer , M. J. , Colditz , G. A. and Manson , J. E. 2004 . Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women . New England Journal of Medicine , 351 : 2694 – 2703 .

- Hu , G. , Lindstrom , J. , Valle , T. T. , Eriksson , J. G. , Jousilahti , P. Silventoinen , K. 2004 . Physical activity, body mass index, and risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with normal or impaired glucose regulation . Archives of Internal Medicine , 164 : 892 – 896 .

- Hu , G. , Tuomilehto , J. , Silventoinen , K. , Barengo , N. C. , Peltonen , M. and Jousilahti , P. 2005 . The effects of physical activity and body mass index on cardiovascular, cancer and all-cause mortality among 47,212 middle-aged Finnish men and women . International Journal of Obesity (London) , 29 : 894 – 902 .

- Hunt , P. and Hillsdon , M. 1996 . Changing eating and exercise behaviour , Oxford : Blackwell .

- Jago , R. and Baranowski , T. 2004 . Non-curricular approaches for increasing physical activity in youth: A review . Preventive Medicine , 39 : 157 – 163 .

- Katzmarzyk , P. T. , Church , T. S. , Craig , C. L. and Bouchard , C. 2009 . Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 41 : 998 – 1005 .

- Kirk , A. F. , Barnett , J. and Mutrie , N. 2007 . Physical activity consultation for people with Type 2 diabetes: Evidence and guidelines . Diabetic Medicine , 24 : 809 – 816 .

- Kodama , S. , Tanaka , S. , Saito , K. , Shu , M. , Sone , Y. Onitake , F. 2007 . Effect of aerobic exercise training on serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: A meta-analysis . Archives of Internal Medicine , 167 : 999 – 1008 .

- Kujala , U. M. , Kaprio , J. , Sarna , S. and Koskenvuo , M. 1998 . Relationship of leisure-time physical activity and mortality: The Finnish twin cohort . Journal of the American Medical Association , 279 : 440 – 444 .

- Lam , L. T. 2001a . Factors associated with parental safe road behaviour as a pedestrian with young children in metropolitan New South Wales, Australia . Accident Analysis and Prevention , 33 : 203 – 210 .

- Lam , L. T. 2001b . Parental risk perceptions of childhood pedestrian road safety . Journal of Safety Research , 32 : 465 – 478 .

- Laurin , D. , Verreault , R. , Lindsay , J. , MacPherson , K. and Rockwood , K. 2001 . Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons . Archives of Neurology , 58 : 498 – 504 .

- Lautenschlager , N. T. , Cox , K. L. , Flicker , L. , Foster , J. K. , van Bockxmeer , F. M. Xiao , J. 2008 . Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: A randomized trial . Journal of the American Medical Association , 300 : 1027 – 1037 .

- Lee , I. M. and Paffenbarger , R. S. Jr. 1996 . How much physical activity is optimal for health? Methodological considerations . Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 67 : 206 – 208 .

- Lee , I. M. and Paffenbarger , R. S. Jr. 2000 . Associations of light, moderate, and vigorous intensity physical activity with longevity: The Harvard Alumni Health Study . American Journal of Epidemiology , 151 : 293 – 299 .

- Lee , I. M. , Rexrode , K. M. , Cook , N. R. , Manson , J. E. and Buring , J. E. 2001 . Physical activity and coronary heart disease in women: Is “no pain, no gain” passé . Journal of the American Medical Association , 285 : 1447 – 1454 .

- Lee , I. M. , Sesso , H. D. , Oguma , Y. and Paffenbarger , R. S. Jr. 2004 . The “weekend warrior” and risk of mortality . American Journal of Epidemiology , 160 : 636 – 641 .

- Leitzmann , M. F. , Park , Y. , Blair , A. , Ballard-Barbash , R. , Mouw , T. Hollenbeck , A. R. 2007 . Physical activity recommendations and decreased risk of mortality . Archives of Internal Medicine , 167 : 2453 – 2460 .

- Levine , J. A. 2007 . Nonexercise activity thermogenesis – liberating the life-force . Journal of Internal Medicine , 262 : 273 – 287 .

- Mahon , A. D. , Duncan , G. E. , Howe , C. A. and Del Corral , P. 1997 . Blood lactate and perceived exertion relative to ventilatory threshold: Boys versus men . Meduicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 29 : 1332 – 1337 .

- Manson , J. E. , Greenland , P. , LaCroix , A. Z. , Stefanick , M. L. , Mouton , C. P. Oberman , A. 2002 . Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women . New England Journal of Medicine , 347 : 716 – 725 .

- Martin , C. K. , Church , T. S. , Thompson , A. M. , Earnest , C. P. and Blair , S. N. 2009 . Exercise dose and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial . Archives of Internal Medicine , 169 : 269 – 278 .

- McBride , A. 1990 . Mental health effects of women's multiple roles . American Psychologist , 45 : 381 – 384 .

- Miyashita , M. , Burns , S. F. and Stensel , D. J. 2008 . Accumulating short bouts of brisk walking reduces postprandial plasma triacylglycerol concentrations and resting blood pressure in healthy young men . American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 88 : 1225 – 1231 .

- Monninkhof , E. M. , Elias , S. G. , Vlems , F. A. , van der Tweel , I. , Schuit , A. J. Voskuil , D. W. 2007 . Physical activity and breast cancer: A systematic review . Epidemiology , 18 : 137 – 157 .

- Mora , S. , Cook , N. , Buring , J. E. , Ridker , P. M. and Lee , I. M. 2007 . Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: Potential mediating mechanisms . Circulation , 116 : 2110 – 2118 .

- Morris , J. N. , Heady , J. A. , Raffle , P. A. , Roberts , C. G. and Parks , J. W. 1953a . Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work . Lancet , 265 ( 6795 ) : 1053 – 1057 .

- Morris , J. N. , Heady , J. A. , Raffle , P. A. , Roberts , C. G. and Parks , J. W. 1953b . Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work . Lancet , 265 ( 6796 ) : 1111 – 1120 .

- Morris , J. N. , Kagan , A. , Pattison , D. C. and Gardner , M. J. 1966 . Incidence and prediction of ischaemic heart-disease in London busmen . Lancet , 2 ( 7463 ) : 553 – 559 .

- Murphy , M. H. , Blair , S. N. and Murtagh , E. M. 2009 . Accumulated versus continuous exercise for health benefit: A review of empirical studies . Sports Medicine , 39 : 29 – 43 .

- Murphy , M. H. , Nevill , A. M. , Murtagh , E. M. and Holder , R. L. 2007 . The effect of walking on fitness, fatness and resting blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials . Preventive Medicine , 44 : 377 – 385 .

- Nader , P. R. , Bradley , R. H. , Houts , R. M. , McRitchie , S. L. and O'Brien , M. 2008 . Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years . Journal of the American Medical Association , 300 : 295 – 305 .

- National Cholesterol Education Program . 2002 . Third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults , Bethesda, MD : National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute . NIH publication #02–5215

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . 2007 . Behaviour change at population, community and individual levels , London : NICE . NICE Public Health Guidance #6

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . 2008a . Promoting or creating built or natural environments that encourage or support physical activity , London : NICE . NICE Public Health Guidance #8

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . 2008b . Workplace health promotion: How to encourage employees to be physically active , London : NICE . NICE Public Health Guidance #13 (available from: www.nice.org.uk)

- National Preventative Health Taskforce . 2008 . Australia: The healthiest country by 2020 – A discussion paper , Canberra, ACT : Commonwealth of Australia .

- Nelson , M. E. , Rejeski , W. J. , Blair , S. N. , Duncan , P. W. , Judge , J. O. King , A. C. 2007 . Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association . Circulation , 116 : 1094 – 1105 .

- Ness , A. R. , Leary , S. D. , Mattocks , C. , Blair , S. N. , Reilly , J. J. Wells , J. 2007 . Objectively measured physical activity and fat mass in a large cohort of children . PLoS Medicine , 4 ( 3 ) : e97

- NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre . 2005 . Health Survey for England 2004 – updating of trend tables to include 2004 data , London : Health and Social Care Information Centre .

- Nilsen , T. I. , Romundstad , P. R. and Vatten , L. J. 2006 . Recreational physical activity and risk of prostate cancer: A prospective population-based study in Norway (the HUNT study) . International Journal of Cancer , 119 : 2943 – 2947 .

- Noda , H. , Iso , H. , Toyoshima , H. , Date , C. , Yamamoto , A. Kikuchi , S. 2005 . Walking and sports participation and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke . Journal of the American College of Cardiology , 46 : 1761 – 1767 .

- Okada , K. , Hayashi , T. , Tsumura , K. , Suematsu , C. , Endo , G. and Fujii , S. 2000 . Leisure-time physical activity at weekends and the risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japanese men: The Osaka Health Survey . Diabetic Medicine , 17 : 53 – 58 .

- Owen , N. , Cerin , E. , Leslie , E. , duToit , L. , Coffee , N. Frank , L. D. 2007 . Neighborhood walkability and the walking behavior of Australian adults . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 33 : 387 – 395 .

- Owen , N. , Humpel , N. , Leslie , E. , Bauman , A. and Sallis , J. F. 2004 . Understanding environmental influences on walking: Review and research agenda . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 27 : 67 – 76 .

- Paffenbarger , R. S. Jr. 1988 . Contributions of epidemiology to exercise science and cardiovascular health . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 20 : 426 – 438 .

- Pate , R. R. , Pratt , M. , Blair , S. N. , Haskell , W. L. , Macera , C. A. Bouchard , C. 1995 . Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine . Journal of the American Medical Association , 273 : 402 – 407 .

- Patel , A. V. , Rodriguez , C. , Jacobs , E. J. , Solomon , L. , Thun , M. J. and Calle , E. E. 2005 . Recreational physical activity and risk of prostate cancer in a large cohort of U.S. men . Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention , 14 : 275 – 279 .

- Perseghin , G. , Price , T. B. , Petersen , K. F. , Roden , M. , Cline , G. W. Gerow , K. 1996 . Increased glucose transport-phosphorylation and muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise training in insulin-resistant subjects . New England Journal of Medicine , 335 : 1357 – 1362 .

- Persinger , R. , Foster , C. , Gibson , M. , Fater , D. C. and Porcari , J. P. 2004 . Consistency of the talk test for exercise prescription . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 36 : 1632 – 1636 .