ABSTRACT

Reliable talent identification and selection (TID) processes are prerequisites to accurately select young athletes with the most potential for talent development programmes. Knowledge about the agreement between scouts who play a key role in the initial TID in football is lacking. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the agreement within four groups of a total of n = 83 talent scouts during rank assessment of under-11 male youth football players (n = 24, age = 11.0 ± 0.3 years) and to describe scouts’ underlying approach to assess talent. Krippendorff’s α estimates indicated disagreement of scouts’ rankings within all groups of scouts (αA = 0.09, αB = 0.03, αC = 0.05, αD = 0.02). Scouts reported relying mainly on their overall impression when forming their final prediction about a player. Reportings of a consistent, structured approach were less prevalent. Taken together, results indicated that different approaches to TID may be associated with disagreement on selection decisions. In order to overcome disagreement in TID, football organisations are encouraged to establish a more structured process. Future research on the elaboration and benefit of ranking guidelines incorporating decomposed and independently evaluated sub-predictors is recommended to improve the reliability of TID.

Introduction

Scientifically sound frameworks and measures of talent identification are of utmost importance for successful sports development on an individual and organisational level, in order to accurately recognise, retain and develop talented young athletes with the greatest potential in their sports (Baker et al., Citation2020; Vaeyens et al., Citation2008).

In football, the initial selection of athletes from grassroots football into talent development programmes is a key phase for the success of such programmes, as this may represent the largest selection cut throughout the talent pathway (Gulbin et al., Citation2013). As such, football coaches, recruiters, and scouts (hereafter referred to as scouts) often identify and select promising young players by assessing their talent during selection tournaments according to standard practices (e.g., number of players, pitch size) in order to evaluate the players’ behaviour based on similarity to future demands (Larkin & Reeves, Citation2018).

A good amount of research with mixed findings exists about potential predictors that may distinguish between elite and sub-elite players (e.g., reviews of Meylan et al., Citation2010; Sarmento et al., Citation2018; Unnithan et al., Citation2012; Williams & Reilly, Citation2000). However, only a few studies have explored which talent predictors scouts consider important and, how they are applied (Bergkamp, Frencken, et al., Citation2022; Christensen, Citation2009; Jokuschies et al., Citation2017; Larkin et al., Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2019). Scouts usually, used rather broadly described and sometimes different talent predictors holistically and intuitively rather than in a structured and deliberate manner (Bergkamp, Frencken, et al., Citation2022; Christensen, Citation2009; Johansson & Fahlén, Citation2017). Holistic talent assessment, however, may be more likely to give way to psychological pitfalls. A recent review by Johnston & Baker (Citation2020) suggested that personal preferences and intuition (Lund & Söderström, Citation2017), framing and the endowment effect (Kahneman et al., Citation1991), the illusion of confidence and associated confirmation bias (Nickerson, Citation1998) and the primacy effect (Smith et al., Citation2009) may lead to low accuracy rates in talent selection decisions. Consequently, different underlying scouting concepts may lead to poor between and within scouts’ agreement (Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018). Indeed, when rating future performance of adult, male football players, a recent study identified poor reliability and small to moderate predictive validity of Dutch football coaches and scouts (Bergkamp, Meijer, et al., Citation2022). Not only in football but also findings in ice hockey indicated low agreement between seven coaches and two scouts during an assessment of n = 13 youth players (Wiseman et al., Citation2014). In cases of low between scouts’ agreement, it would be hard to establish predictively valid talent identification and selection processes, as agreement on a player’s potential is low in the first place. As such, individual athletes’ selection for a talent development programme would largely depend on the visual subjective evaluation of a scout. Thus, from a sports organisational point of view, the premise that mainly young talents with the most potential for future elite performance are selected, and subsequently developed, can be questioned. To date, no study has quantified the agreement between scouts when identifying and selecting youth football players at selection tournaments.

Given the need for talent identification and selection to be reliable, the aim of the present study was to quantify the agreement between scouts’ player-rankings at two different selection tournaments and describe their underlying approaches to assess talent in under-11 (U11) youth football. Based on previous research on approaches to talent assessment and mixed findings about potential talent predictors, it was expected that rather low agreement between scouts’ selection decisions exists.

Methods

Participants

Scouts. A total of N = 441 talent scouts across Switzerland had a talent scout education provided by the Swiss Football Association (SFA) and were thus eligible to be contacted (see ). The education lasted two days and encompassed the SFA’s talent identification and selection framework, as well as suggestions on evaluating a youth players’ potential based on the acronym TIPS (technique, intelligence, personality, speed). Overall, 7.5% of the eligible scouts usually scouted in the same region to where the talent selection tournaments were held, and as such were excluded from the study to avoid including prior knowledge of participating players. Thus, n = 408 scouts were eligible for the study and were invited to participate. Following subsequent responses to study invitation, a total of n = 100 talent scouts volunteered to participate. Prior to the start of the study, participating scouts had been scouting (e.g., talent detection, identification and selection) at least since their completed talent scout education 4.8 ± 2.5 years. The study complied with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional ethical approval was provided (Swiss Federal Institute of Sport; Nr. 2021/130).

Procedures

Study Design. Enrolled scouts were randomly assigned to one of four groups (see ). A detailed description of the various group conditions can be found elsewhere (Lüdin et al., Citation2022). Briefly, the between-group conditions differed in the game format (3v3 or 7v7) and knowledge about the players' relative maturation status was labelled via shirt-numbers to mitigate possible maturation selection biases. However, conditions within the groups were the same (i.e., instructions prior to the task, video footage and information available about participating players). Nationally, various procedures for selecting players into a talent development programme exist. To standardise the data collection and since scouting at selection tournaments is usually a relative comparison of participating players, this study used a ranking procedure. The scouts had to rank players at two different selection tournaments based on the priority of being selected for a talent development programme, i.e., they provided a separate player ranking (i.e., 1 to 12) for each tournament. Afterwards, scouts completed a questionnaire on their underlying approach to assessing talent in U11 youth football. To minimise the influence of the footage they reviewed for the first task on their answers, the questionnaires were sent two months after completing the ranking task.

Youth players and selection tournaments

With a cut from 15’000 to 2’000 players, the transition from the U11 age category to the U12 age category represents the largest selection cut on the talent pathway of Swiss football (Knäbel, Citation2014). All participating youth football players (n = 24, age = 11.0 ± 0.3 years, height = 143.6 ± 6.9 cm, body mass = 35.9 ± 5.9 kg) played at a grassroots football club.

Two official selection tournaments and their participating players (n = 12 per tournament) were recorded. Tournaments were played according to the current practice of the Swiss youth football association, consisting of 3v3 and 7v7 matches on 20 × 28 m and 32 × 52 m sized pitches, respectively. Four games of each format were conducted. Duration of the 3v3 matches and 7v7 matches were 5 and 10 min, respectively. 3v3 matches used four goals (0.8 m × 1.2 m; two goals positioned on each side), whereas 7v7 matches were played with one goal (2.0 × 5.0 m) on each side and with a goalkeeper each. Goalkeepers were included in 7v7 matches but were not part of the scouts’ ranking procedure. Matches were separated by two-minute breaks, in which playing positions were rotated in order to provide a variety of game situations within and between participating players.

Video settings

A detailed description of the camera setting used to film the tournaments can be found in a recently published article (Lüdin et al., Citation2022). A total of four mounted static cameras located eight metres above the ground and two manually controlled cameras on a tripod were used to guarantee full coverage of the match play from different angles. Subsequently, the footage was synchronised and edited to a single recording per group and tournament. The choice of most appropriate camera angle for capturing the game was based on the following criteria: position of the ball, direction of play and player positions. Cutting was done by the first author using the software DaVinci Resolve (Version 17.2).

Player ranking procedure

Scouts received online access to the contents of standardised task instructions (i.e., how to navigate), the match recordings and a player-ranking template. Scouts were instructed as “evaluate players in the selection tournaments as similarly as when you are talent scouting”. They were asked to place the observed players of each tournament into a ranking template based on the priority for them to be selected for a talent development programme (i.e., from 1 to 12), resulting in a total of two rankings per scout (i.e., one for Tournament A and one for Tournament B). Specifically, the instruction was as follows: “Place the player you select first for a selection team at the top of the list. The player you select last for a selection team should be placed at the bottom of the ranking list”.

Questionnaire

A link with access to an online questionnaire was sent to all scouts who completed their first task within two months. The scouts’ underlying approach to assessing talent in U11 youth football players was evaluated on the basis of reported frequencies of the application of four statements. A detailed description of the statements is presented in . The four statements were derived from Bergkamp, Frencken, et al. (Citation2022)“s questionnaire. The first, second, fourth and fifth statements from the ‘Scoring and combining information’ section were adapted and translated into the national languages (i.e., German and French). A frequency likert scale from one (= never) to five (=always) was used.

Table 1. Number, wording and scales of the statements from the scouts’ questionnaire.

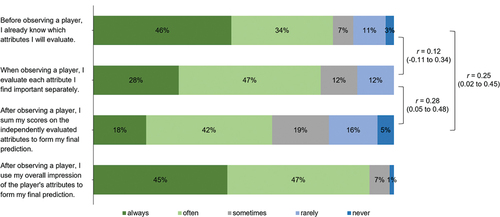

Statements 1 to 3 and their associated correlations explored the extent to which a structured approach is consistently used when evaluating talent. In contrast, statement 4 explored the frequency of the application of an overall impression to form a final prediction.

Data analysis

Quantification of scouts’ agreement

Krippendorff’s Alpha (α) and corresponding bootstrap 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate the degree to which the player-rankings for each tournament within the groups were in agreement (Hayes & Krippendorff, Citation2007). These calculations were obtained using RStudio (Version 1.3.1073) for Windows, and the krippendorffsalpha 1.1-2 package (Hughes, Citation2022). Group and overall means of α estimates were calculated to quantify groups’ and overall scouts’ agreement. Ranges of agreement were defined as absent (α ≤ 0), slight (0 < α ≤ 0.2), fair (0.2 < α ≤ 0.4), moderate (0.4 < α ≤ 0.6), substantial (0.6 < α ≤ 0.8) and near-perfect (α > 0.8) agreement (Hughes, Citation2021).

Report of scouts’ approach to assess talent

Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVAs using group as the independent variable and the frequencies reported for the statements as dependent variables were used to analyse whether groups significantly differed in their reported approach to assess talent. To determine the consistency of the applications of statements 1 to 3, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) and corresponding Fisher 95% confidence intervals were computed in addition to the reported frequencies. For example, an r = 1 between statements 1 and 2 and the exact same corresponding reported frequencies would mean that a scout who “always” knows which attribute to evaluate before observing a player also “always” evaluates each attribute separately when observing a player, thus indicating perfect consistency and a uniform application of statements 1 and 2. These calculations were performed using SPSS (Version 25.0). According to Cohen (Citation1988) r values were used to quantify the consistency as low (0.1 ≤ r < 0.3), medium (0.3 ≤ r < 0.5) or high (r ≥ 0.5).

Results

Quantification of scouts’ agreement

A summary of Krippendorff’s α estimates to quantify the scouts’ agreement is presented in .

Table 2. Summary of Krippendorff’s α estimates for the four groups of scouts.

All Krippendorff’s α estimates indicated absent to slight agreement within the four groups of scouts. Corresponding bootstrap 95% confidence intervals, including the value α = 0, indicated that agreements between scouts did not significantly differ from the absence of agreement.

Report of scouts’ approach to assess talent

No significant group effects were evident for the frequencies reported for any of the four statements (1. H (3) = 6.22, p = 0.10; 2. H(3) = 1.03, p = 0.80; 3. H(3) = 2.59, p = 0.46; 4. H(3) = 0.86, p = 0.84). Hence, overall response percentages for statements 1 to 4 were calculated. shows the reported overall response percentages for all statements describing the scouts’ approach to assess talent. Spearman’s r, with corresponding Fisher 95% confidence intervals in brackets, is provided and linked according to statements 1 to 3.

Figure 2. Reported response percentage to each statement about the scouts’ approach to assess talent and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) with corresponding fisher 95% confidence intervals in brackets between statements 1 and 3.

Eighty per cent of the scouts reported that they “always” or “often” know which attributes they will evaluate prior to observing a player. Seventy-five per cent stated to “always” or “often” evaluate each attribute separately, when observing a player, while sixty per cent “always” or “often” sum their scores on the independent attributes after observing and before forming their final prediction about a player. Spearman’s r estimates in combination with different reported frequencies indicated that scouts did not consistently and uniformly apply statements 1 to 3. Ninety-two per cent of the scouts reported to “always” or “often” use their overall impression of the player’s attributes after observing and before forming their final prediction.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to quantify the agreement between scouts’ player-rankings at two different selection tournaments and describe their underlying approaches to assess talent in U11 youth football. The conducted research provides insight into a sparsely explored aspect of talent identification and selection in youth football. Results showed that the agreement between the scouts’ rankings of the priority in which 12 U11 youth football players should be selected for a talent development programme was absent to slight and therefore were far removed from what should be considered acceptable for selecting settings. Scouts did apply components of a structured assessment, but they did not do it uniformly and consistently. This is in line with findings by Bergkamp, Frencken, et al. (Citation2022) who previously pointed out that applying structure may not be a unimodal construct. After all, scouts mainly relied on their overall impression of a player compared to summing scores of independently evaluated attributes when forming their final prediction. Taken together, results indicated that various, inconsistent approaches to talent assessment may be linked to different rankings between talent scouts. As such, in a usual selection setting, a player’s ranking, and, therefore, their chance of selection depended on the particular scout assessing the tournament. This finding underpins the need to detect and understand possible causes for differences in scouts’ rankings, which would allow the identification and testing of measures to improve the agreement between talent scouts, and, hence, provide the foundation for the implementation of reliable talent identification and selection.

Causes for disagreement

Football games can be highly unpredictable and vary in nature of game (Mackenzie & Cushion, Citation2013; Reep & Benjamin, Citation1968), and, therefore, information cues for the scouts to evaluate the players’ rankings were random, numerous, simultaneous, varied in frequency, were sometimes more and sometimes less obvious and possibly even contradicted themselves. The talent identification and selection process consisted of judgements and subsequent decisions about numerous players, which were complex tasks when additionally combined with uncertainty (Campbell, Citation1988). Task complexity was described by characteristics of the information cues (Wood, Citation1986): component (i.e., number of information cues), coordinative (i.e., timing, frequency and intensity of information cues) and dynamic complexity (i.e., change of information cues). Therefore, the talent identification and selection process during the presented selection tournaments could be classed as a highly complex task for participating scouts. Complex tasks were associated with ambiguity that allowed the possibility of varying conclusions between decision-makers (Blake & Logothetis, Citation2002). This ambiguity was reflected by previous studies that considered predictors deemed being important for talent identification and selection in football by practitioners (Bergkamp, Meijer, et al., Citation2022; Larkin & Larkin et al., Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2019). A comparison of the data from these studies showed similarities (i.e., high importance given to technical skills) and differences (i.e., different importance given to perceptual-cognitive, physical, physiological and motor skills) between the various panels. Further, it became apparent that the descriptions of certain predictors lacked specificity and were rather broadly described. Varying and/or unspecifically described talent predictors could have scouts picked up on different game scenes and/or interpreted the same scene differently to form their player rankings. Further, due the mind’s characteristics, scouts may have selected different heuristics in order to “short-cut” their outcome of the player rankings (Plessner & Haar, Citation2006). Heuristics can be shaped by individual reinforcement, as well as social and evolutionary learning (Gigerenzer, Citation2008). Individual reinforcement and social learning from a mentor or within their peer groups during past scouting activity differed from scout to scout. Consequently, expressions of heuristics depended on a scout’s unique learning background. Thus, one scout could have assessed leadership differently than another scout, who in turn may adopt differently shaped heuristics when assessing technical-tactical behaviour for example. Such differences would lead to variability in the scouts’ player-rankings. In addition, the task of providing correct rankings itself may have introduced an unintended difficulty: The likelihood of unintentional errors in comparison tasks possibly increases with increased ranking sizes (e.g., assign player A higher than B when in fact B would be higher rated in a head-to-head comparison) (Miller, Citation1956).

Suggestions for improvement of agreement

It was proposed that agreement improves when following a more structured manner compared to unstructured-holistic approaches (Dawes et al., Citation1989; Den Hartigh et al., Citation2018). This conclusion is supported by research from the field of employee selection (Huffcutt & Arthur, Citation1994), academic admission decisions (Kuncel et al., Citation2013), judge sentencing (Anderson et al., Citation1999), or grading at college (Dana & Thomas, Citation2006). However, contrary to expectations, a recent study did not find improved reliability and predictive validity within n = 96 football coaches and scouts when rating adult professional football player performance using structured approaches compared to an unstructured-holistic approach (Bergkamp, Meijer, et al., Citation2022). Predictive validity was small to moderate and reliability was poor, independent of the approach tested. This highlights the difficulty of improving agreement among scouts. However, following two principles (decomposition and independence of judgement), Kahneman et al. (Citation2021) provide a foundation of how structured approaches could be guided in practice.

Ranking guidelines would serve to decompose talent identification into sub-steps. Acronyms such as TIPS (technique, intelligence, personality, speed), TABS (technique, attitude, balance, speed) or SUPS (speed, understanding, personality, skill) are examples of the fact that guidelines on how to decompose talent identification into sub-predictors are already practiced in some places (Brown, Citation2001; Stratton et al., Citation2004). Additionally, ranking guidelines should also contain the detailed definitions of associated rating scales. Anchoring sub-predictor rating scales to sufficiently specific descriptors should help to provide the basis to subsequently rank more consistently and distinctively between players. Further, ranking sizes should be chosen at a level that avoids comparison inaccuracies (Miller, Citation1956). In a set of 12 players, for example, one could first distinguish between three levels: Top, middle and bottom ranked players, followed up by player-rankings within each level if still required. Independence of sub-judgements would be important to counteract a possible pulling of the overall judgement towards the first impression of a player (i.e., halo effect; Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977). As such, evaluating a sub-predictor for all participating players before assessing the next sub-predictor, compared to evaluating all sub-predictors successively for one player before assessing the next player, could help mitigate the halo effect.

A mere distribution of rating guidelines, which include described decomposition into sub-judgements and their independent evaluation, should not be externally imposed on its practitioners. Rather, it seems more promising if scouts are already involved in the creation of the guidelines. As such, a common understanding of the intended identification and selection process is already formed in the process of elaborating the guidelines. This could be done by using procedures that have already been tested in the setting of talent identification and selection in youth soccer such as the modified Delphi method (Larkin et al., Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2019) or the use of verbal reports (Reeves et al., Citation2019). Subsequent ongoing support and education of scouts could provide a way to consolidate and further develop a common understanding of the identification and selection process (Reeves et al., Citation2018).

Limitations

The findings of the present study are limited to players from the respective age-group (i.e., U11). Transfer of the present findings to older youth categories should be done with caution, as player’s age may play an influential role in the difficulty of talent identification and selection. The closer the players get to their adult performance level, the less time for contingencies remains. Hence, scouting in older age groups may be less complex, and thus selection decisions between scouts may be more aligned compared to early selections. Early selection and its long-term effectiveness can be questioned (Güllich, Citation2014) and therefore it is recommended to increase the focus on selection procedures in older age categories (Bergkamp, Meijer, et al., Citation2022). Research on the agreement of talent identification and selection in older youth-groups would be needed to assess the influence of player’s age on the scouts’ agreement.

The present study allowed to investigate selection decisions within a closed group of players (i.e., a comparison between players). Although this reflects a practical approach, one may want to be able to compare a player within one group to a player from another group. In order to meet this demand, studies about the effectiveness of evaluating the same player on numerous occasions against different opponents would be needed.

Because the study was based on voluntary participation by the scouts, a possible self-selection bias cannot be ruled out. Therefore, although it was a large sample of scouts (n = 83 out of N = 441) a lack of knowledge on true population representativeness exists.

Practical implications

Talent scouting in youth football is a complex task. Which players are selected for a talent development programme, and which are not, is decided under uncertainty in a highly unpredictable nature of game (Mackenzie & Cushion, Citation2013; Reep & Benjamin, Citation1968). Scouts often rely on their overall impression (i.e., “gut feeling” or tacit knowledge) based on multi-disciplinary predictors to make their talent selection decisions (Bergkamp, Frencken, et al., Citation2022; Christensen, Citation2009; Johansson & Fahlén, Citation2017). However, different predictors are deemed important and various approaches to form an overall impression may be associated with disagreement on talent selection decisions. This disagreement is problematic as, firstly, young players often get selected for talent development programmes based on the visual subjective evaluation of a scout and secondly, football organisations cannot sufficiently rely on the premise that young athletes with the best possible chances to excel in the future are actually being selected. Therefore, scouts should be aware of the complex task they are facing and open-minded to tackling psychological pitfalls and linked causes of disagreement (Johnston & Baker, Citation2020). Establishing a more common understanding and approach to talent identification and selection processes between scouts is suggested to increase agreement on talent selection decisions.

Conclusion

The absence of agreement in player rankings between talent scouts at selection tournaments of youth football players aged U11 could be linked to the application of different approaches to talent assessment. Disagreement between scouts requires football organisations to improve talent identification and selection processes in order to reach an adequate level of agreement. The fact that talent identification and selection in football is a complex task, due to the unpredictable nature of the game and as much of a young player’s potential is uncertain at the time of selection, should not go unnoticed. This generally limits the effectiveness even for the most sophisticated talent identification and selection processes that may exist. However, the associated sources that contribute to scouts’ disagreement should be addressed. A more consistently structured approach to identifying and selecting talent may help mitigate causes of disagreement. Ranking guidelines in order to decompose an overall judgement into sub-steps and independence of sub-judgements of talent predictors may be promising to improve agreement between scouts. Thus, individual athletes would not be dependent entirely on the visual subjective evaluation of the scout, and football organisations could increase the effectiveness of their talent development programmes by selecting and developing young athletes with the most potential for future elite performance more reliably.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all talent scouts for their contributed expertise in the study. We thank the coaches, staff and players of the clubs for their efforts during the selection tournaments. Furthermore, we want to acknowledge Stevie Brunner and Patrick Bruggmann of the Swiss Football Association for their support and cooperation during the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, J. M. , Kling, J. R., & Stith, K. (1999). Measuring interjudge sentencing disparity: Before and after the federal sentencing guidelines. The Journal of Law and Economics, 42(S1), 271–308. https://doi.org/10.1086/467426

- Baker, J., Cobley, S., & Schorer, J. (Eds.). (2020). Talent identification and development in sport: International perspectives. (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003049111

- Bergkamp, T. L. G., Frencken, W. G. P., Niessen, A. S. M., Meijer, R. R., & den Hartigh, R. J. R. (2022). How soccer scouts identify talented players. European Journal of Sport Science, 22(7), 994–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1916081

- Bergkamp, T. L. G., Meijer, R. R., den Hartigh, R. J. R., Frencken, W. G. P., & Niessen, A. S. M. (2022). Examining the reliability and predictive validity of performance assessments by soccer coaches and scouts: The influence of structured collection and mechanical combination of information. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 102257, 102257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102257

- Blake, R., & Logothetis, N. K. (2002). Visual competition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn701

- Brown, J. (2001). Sports Talent. Human Kinetics.

- Campbell, D. J. (1988). Task Complexity: A Review and Analysis. The Academy of Management Review, 13(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306775

- Christensen, M. K. (2009). “An eye for talent”: Talent identification and the “practical sense” of top-level soccer coaches. Sociology of Sport Journal, 26(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.26.3.365

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Dana, J., & Thomas, R. P. (2006). In defense of clinical judgment … and mechanical prediction. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(5), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.537

- Dawes, R. M., Faust, D., & Meehl, P. E. (1989). Clinical versus Actuarial Judgment. Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 243(4899), 1668–1674. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2648573

- Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Niessen, A. S. M., Frencken, W. G. P., & Meijer, R. R. (2018). Selection procedures in sports: Improving predictions of athletes’ future performance. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(9), 1191–1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2018.1480662

- Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Why heuristics work. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00058.x

- Gulbin, J. P., Croser, M. J., Morley, E. J., & Weissensteiner, J. R. (2013). An integrated framework for the optimisation of sport and athlete development: A practitioner approach. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(12), 1319–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.781661

- Güllich, A. (2014). Selection, de-selection and progression in German football talent promotion. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(6), 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2013.858371

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

- Huffcutt, A. I., & Arthur, W. (1994). Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited: Interview validity for entry-level jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.184

- Hughes, J. (2021). Krippendorffsalpha: An R package for measuring agreement using krippendorff’s alpha coefficient. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-046

- Hughes, J. (2022). Measuring agreement using krippendorff’s alpha coefficient (version 1.1-2) [Package]: RStudio.

- Johansson, A., & Fahlén, J. (2017). Simply the best, better than all the rest? Validity issues in selections in elite sport. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117718020

- Johnston, K., & Baker, J. (2020). Waste reduction strategies: Factors affecting talent wastage and the efficacy of talent selection in sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02925

- Jokuschies, N., Gut, V., & Conzelmann, A. (2017). Systematizing coaches’ ‘eye for talent’: Player assessments based on expert coaches’ subjective talent criteria in top-level youth soccer. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(5), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117727646

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.193

- Kahneman, D., Sibony, O., & Sunstein, C. R. (Eds.). (2021). Structure in Hiring . In Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (pp. 300–311). Little, Brown Spark.

- Knäbel, P. (2014). The Swiss Football Association’s youth development concept. Retrieved from. https://www.football.ch/portaldata/27/Resources/dokumente/nachwuchsfoerderung/footeco/de/5.35._Nachwuchsfoerderungskonzept.pdfKuncel

- Kuncel, N. R., Klieger, N. R., Connelly, D. M. B. S., & Ones, D. S. (2013). Mechanical versus clinical data combination in selection and admissions decisions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034156

- Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., & Sampaio, J. (2017). Talent identification and recruitment in youth soccer: Recruiter’s perceptions of the key attributes for player recruitment. PLOS ONE, 12(4), e0175716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175716

- Larkin, P., & Reeves, M. J. (2018). Junior-elite football: Time to re-position talent identification? Soccer and Society, 19(8), 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2018.1432389

- Lüdin, D., Donath, L., Cobley, S., Mann, D., & Romann, M. (2022). Player-labelling as a solution to overcome maturation selection biases in youth football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(14), 1641–1647. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2022.2099077

- Lund, S., & Söderström, T. (2017). To see or not to see: Talent identification in the Swedish Football Association. Sociology of Sport Journal, 34(3), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2016-0144

- Mackenzie, R., & Cushion, C. (2013). Performance analysis in football: A critical review and implications for future research. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(6), 639–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.746720

- Meylan, C., Cronin, J., Oliver, J., & Hughes, M. (2010). Talent identification in soccer: The role of maturity status on physical, physiological and technical characteristics. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 5(4), 571–592. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.5.4.571

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043158

- Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation Bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250

- Plessner, H., & Haar, T. (2006). Sports performance judgments from a social cognitive perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(6), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.03.007

- Reep, C., & Benjamin, B. (1968). Skill and Chance in Association Football. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A (General), 131(4), 581–585. https://doi.org/10.2307/2343726

- Reeves, M. J., Littlewood, M. A., McRobert, A. P., & Roberts, S. J. (2018). The nature and function of talent identification in junior-elite football in English category one academies. Soccer and Society, 19(8), 1122–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2018.1432385

- Reeves, M. J., McRobert, A. P., Lewis, C. J., Roberts, S. J., & Sunderland, C. (2019). A case study of the use of verbal reports for talent identification purposes in soccer: A Messi affair! PLOS ONE, 14(11), e0225033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225033

- Roberts, S. J., McRobert, A. P., Lewis, C. J., & Reeves, M. J. (2019). Establishing consensus of position-specific predictors for elite youth soccer in England. Science and Medicine in Football, 3(3), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2019.1581369

- Sarmento, H., Anguera, M. T., Pereira, A., & Araújo, D. (2018). Talent identification and development in male football: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0851-7

- Smith, M. J., Greenlees, I., & Manley, A. (2009). Influence of order effects and mode of judgement on assessments of ability in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(7), 745–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410902939647

- Stratton, G., Reilly, T., Richardson, D., & Williams, A. M. (2004). Youth Soccer: From Science to Performance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203644133

- Unnithan, V., White, J., Georgiou, A., Iga, J., & Drust, B. (2012). Talent identification in youth soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.731515

- Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., Williams, A. M., & Philippaerts, R. M. (2008). Talent identification and development programmes in sport: Current models and future directions. Sports Medicine, 38(9), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838090-00001

- Williams, A. M., & Reilly, T. (2000). Talent identification and development in soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(9), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410050120041

- Wiseman, A. C., Bracken, N., Horton, S., & Weir, P. L. (2014). The difficulty of talent identification: Inconsistency among coaches through skill-based assessment of youth hockey players. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 9(3), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.9.3.447

- Wood, R. E. (1986). Task complexity: Definition of the construct. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37(1), 60–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(86)90044-0